July 16, 2015

Over the past half year, the U.S. Department of Justice ("DOJ") and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration ("FDA") sustained their enforcement efforts against both businesses and individuals, raking in significant civil recoveries while pursuing criminal cases against industry participants. In the meantime, FDA released important new guidance on many key topics, including online promotional activity, current good manufacturing practice ("cGMP") compliance, and drug development. FDA also issued guidance on a slew of issues that are particularly noteworthy to device manufacturers. Even more dramatic developments may be on the horizon; just days ago, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the 21st Century Cures Act, which promises to–among other measures–streamline the drug and device approval processes.

As we did in our 2014 Year-End FDA and Health Care Compliance and Enforcement Update on Drugs and Devices ("2014 Year-End Update"), we address below new developments relating to the regulation of both drugs and devices. This Update begins by summarizing government enforcement efforts against drug and device companies thus far in 2015, focusing on False Claims Act ("FCA") and the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act ("FDCA") cases. After addressing enforcement actions that underscore the consequences of compliance failures, the Update turns to notable regulatory developments on several issues that may impact drug and device companies: promotional activities, manufacturing practices, product development, and the Anti-Kickback Statute ("AKS"). In addition, we address topics of particular importance to device manufacturers.

I. DOJ Enforcement in the Pharmaceutical and Medical Device Industries

Last January, we predicted that 2015 would be an even busier year than 2014 in terms of DOJ enforcement in the drug and device sector. The first half of 2015 has borne that out, as DOJ has actively pursued cases against drug and device companies under the FCA and FDCA at a rate that seems to exceed last year’s. Interest in criminal fraud cases in the drug and device space also has increased. In a May 14, 2015 speech at the American Bar Association’s Annual National Institute on Health Care Fraud, Assistant Attorney General Leslie Caldwell noted that the Medicare Fraud Strike Force is focused on emerging fraud trends in Medicare Part D and laboratory services areas, calling them the "latest frontiers in Medicare fraud."[1]

Assistant Attorney General Caldwell also cautioned that the Strike Force would not hesitate to "follow evidence of health care fraud wherever it leads, including into corporate boardrooms and executive suites."[2] To that end, she noted that within the past seven months, the number of open criminal corporate investigations has increased from a "handful" to now over a dozen, with additional prosecutorial resources being devoted to this area.[3] These comments follow others in the past year indicating that DOJ’s criminal fraud section is also increasing its scrutiny of FCA qui tam cases for potential criminal targets. In light of these remarks–and the number of enforcement actions concluded thus far this year–it is clear that the stakes are as high now as ever for drug and device manufacturers.

A. Civil Actions / False Claims Act

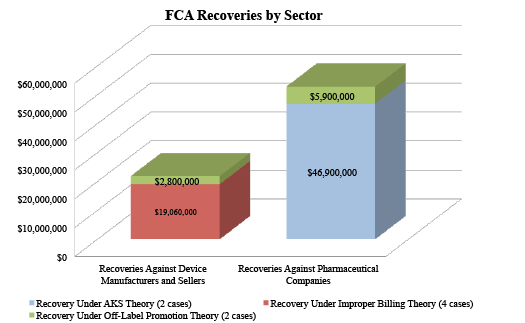

This year is on track to surpass the fourteen FCA enforcement actions resolved in 2014 by DOJ against drug and device makers, with eight resolutions so far this year. These eight actions total nearly $75 million in recoveries from drug companies and device manufacturers and sellers. All but one of these settlements originated in a qui tam complaint, consistent with the trend of record numbers of new cases being filed by FCA whistleblowers, or relators, in recent years. Relators stand to share in up to 25% of the substantial settlements, which have ranged from $1.25 million to $39 million.

Interestingly, the top settlements to date, totaling nearly $47 million, both resolved allegations of violations of the AKS by pharmaceutical manufacturers. As detailed in Part III below, the AKS prohibits offering or soliciting remuneration in exchange for referrals that may be covered by federal health programs. The AKS defines "remuneration" very broadly, and the two AKS-related actions this year demonstrate that companies must take care any time they offer anything at all that might have value to prescribers.

For example, in one case that settled for $39 million, DOJ alleged that the defendant drug company provided speaker fees and dinners to physicians in exchange for the physicians prescribing the company’s drugs.[4] As part of the settlement, the company also agreed to enter into a Corporate Integrity Agreement ("CIA") with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General ("HHS OIG") (the only CIA with HHS OIG entered into by any company in the past six months), which obliges the company to implement internal compliance reforms for the next five years.[5] Those compliance reforms include appointment of compliance personnel, workforce education and training, ongoing monitoring of the company’s sales force, and annual reporting to HHS OIG.[6]

The other AKS settlement this year resolved allegations that resurfaced the relationships between pharmaceutical companies and pharmacy benefit managers. According to the government, the pharmaceutical company in that case provided price concessions to pharmacy benefit managers in exchange for being the "sole and exclusive" provider listed on the prescription drug formulary.[7] Showing its willingness to pursue both sides of an allegedly improper arrangement, DOJ also settled a separate action against the pharmacy benefit manager that produced the formulary. The two settlements together totaled nearly $16 million.[8]

Even with so many large settlements based on alleged off-label promotion in the rearview mirror, such cases have continued on in 2015, with two settlements of cases involving off-label allegations totaling $8.7 million.[9] Drug and device companies are facing FCA allegations outside the historically more common AKS and off-label areas as well, with other theories supporting four FCA settlements totaling just over $19 million.

The variety of FCA theories in settlements so far this year demonstrates how drug and device manufacturers’ compliance efforts with respect to government-funded purchases go well beyond off-label promotion and AKS.

Indeed, all four of the remaining 2015 settlements implicated very different kinds of alleged conduct. Two cases involved alleged failures to comply with conditions of payment for drugs and devices pursuant to contracts with the Department of Veterans Affairs and/or the Department of Defense. In one, a large government contractor failed to provide the government with the lowest price available–as mandated by government contracting requirements–leading to a nearly $6 million settlement.[10] In the other, the contractor-device manufacturer allegedly misrepresented to the government that the devices provided were manufactured in a country designated under the Trade Agreements Act of 1979, when in fact they were manufactured in prohibited countries; the allegations resulted in a $4.4 million settlement.[11] A subsidiary of that same contractor also settled allegations that it marketed a device for inpatient use in order to garner higher reimbursement rates and sales rather than for its allegedly proper use for cheaper outpatient procedures.[12] Last, a durable medical equipment supplier was alleged to have altered prescriptions and supporting documentation by, among other methods, adding or altering chart notes and forging physician signatures, in order to have claims paid for wheelchairs and associated accessories.[13]

B. FDCA Enforcement Actions

The first half of 2015 also has seen active DOJ enforcement efforts in the drug and device space outside the FCA context, with four civil actions and one criminal action brought under the FDCA. These actions involved allegations of marketing products without FDA approval and noncompliance with current good manufacturing practice ("cGMP") rules.[14]

1. Marketing Unapproved Devices

In January 2015, a federal court in South Dakota entered a preliminary injunction against an individual and his businesses for selling laser devices without FDA clearance.[15] The lasers were marketed as a treatment for more than 200 diseases and disorders, including cancer, HIV/AIDS, venereal disease, and diabetes, none of which were FDA-approved indications. The court concluded that selling the lasers under the guise of "private membership associations," and requiring purchasers to join the association to be eligible to purchase the products, was not a shield to FDCA liability.[16]

In February, DOJ obtained a permanent injunction against an Oregon company and its former president and general manager, preventing them from marketing a product named "Maxam Nutraceutics."[17] The company claimed that the product treated autism, Alzheimer’s disease, HIV and fibromyalgia–none of which were FDA-approved uses. In addition to being unapproved, the court also found that the drug was an adulterated dietary supplement due to the company’s repeated failures to specify the ingredients used in the products or conduct appropriate testing for components used in the manufacturing of the products.[18] Notably, DOJ filed suit in September 2013 only after the defendants failed to adequately respond to several FDA Warning Letters (dating back to October 2010) and Form 483 observations relating to defendants’ compliance with cGMP regulations and claims that defendants made on their websites.[19] As the court observed, long after DOJ filed suit defendants’ Facebook page and websites included improper claims–and defendants had yet to ensure their manufacturing was compliant with cGMP.[20]

2. cGMPs

FDA typically enforces cGMP rules through administrative means (such as inspections, Form 483 observations, and Warning Letters) and civil actions (such as injunctions and consent decrees). But criminal liability can result from particularly egregious violations as well. In 2015, DOJ has continued to actively enforce cGMP rules outside of the administrative context. Among the cGMP enforcement actions so far this year were two civil cases involving device manufacturers and one criminal settlement by a drug company. Notably, in all three instances, the government alleged that the companies had recurring violations that were not corrected after identification: a reminder of the importance of taking very seriously FDA’s process of conducting inspections and issuing Form 483 observations and/or Warning Letters.

First, Atrium Medical Corporation and two of its senior executives were permanently enjoined for failing to follow FDA’s Quality System ("QS") regulations that govern the design, manufacture, packaging, labeling, storage, installation, and servicing of medical devices.[21] The company’s devices are used for cardiovascular purposes, including chest drains, surgical meshes, vascular grafts, and stent systems. Atrium was first cited by FDA in 2009, and DOJ alleged that it failed to correct the deficiencies in subsequent visits by FDA in 2010, 2012, and 2013. In addition to the injunction, Atrium agreed to pay $6 million in disgorgement of profits.

Second, multinational device manufacturer Medtronic Corporation and two top executives also entered into a consent decree barring them from making or selling the SynchroMed infusion pump, which delivers medication for cancer, chronic pain, and severe spasticity treatments.[22] As described in more detail in Part III below, DOJ alleged that between 2006 and 2013, FDA noted significant violations of QS regulations around design controls, complaint handling, and corrective and preventive action.[23]

Lastly, in March, McNeil-PPC Incorporated, a wholly owned subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson, pled guilty to one count of selling adulterated medicine and agreed to pay a criminal fine of $20 million and forfeit an additional $5 million.[24] The conduct at issue dates back to a 2009 incident where black specks–later identified as metal particles–were found in its liquid over-the-counter Infants’ Tylenol. The company issued a recall the following year for bottles of Infants’ and Children’s Tylenol and Children’s Motrin produced at its Fort Washington, Pennsylvania, facility, which also was permanently enjoined in 2011 from operating until remedial measures are completed. The criminal plea and fine resolve allegations that the company failed to implement an adequate corrective action plan following these events and other instances where metal particles were found in its products.

C. FCPA Investigations

Over the past six months, DOJ did not resolve any ongoing investigations targeting drug and device companies for alleged violations of the FCPA’s anti-bribery and accounting provisions. Nevertheless, one recent FCPA-related development merits a brief word. In March, an orthopedic medical device manufacturer disclosed to the U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission ("SEC") that its three-year deferred prosecution agreement ("DPA") with DOJ, originally scheduled to expire at the end of that month, was extended for another year.[25] The original DPA stemmed from allegations of improper payments to doctors and settled for almost $17.3 million in criminal penalties and $5.4 million in civil remedies paid to the SEC.[26] The extension comes after a whistleblower subsequently alerted the company to potential additional misconduct in Brazil and Mexico over the same time period as covered by the DPA. Last July, the SEC issued a subpoena for documents relating to the company’s internal investigation into the newly uncovered allegations. While DOJ has elected only to extend the DPA at this time, it has reserved the right to take further action against the company, including revoking the DPA and/or prosecuting the company and/or the employees involved. For further analysis of this development–and enforcement of anti-corruption laws worldwide–please see Gibson Dunn’s 2015 Mid-Year FCPA Update.

II. Promotional Issues

Certain recent developments–including the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Sorell v. IMS Health, Inc., the Second Circuit’s decision in United States v. Caronia, and Amarin Pharma, Inc.’s ongoing suit against FDA[27]–have limited (or seek to limit) the government’s regulation of truthful promotional speech by drug and device makers. Nevertheless, U.S. regulators remain focused on employing all of their tools to enforce U.S. laws restricting promotional activities in the administrative setting and beyond. Accordingly, drug and device companies must continue to adapt to shifts in the applicable restrictions–and to enforcement trends relating to promotional activities. Like 2014, the first six months of 2015 have given industry participants plenty to digest in terms of FDA’s regulation of promotional activities. Below, we address several developments on this front.

A. FDA Enforcement Activity – Advertising and Promotion

During the first half of 2015, FDA’s Office of Prescription Drug Promotion ("OPDP") issued seven Untitled Letters, but did not issue any Warning Letters.[28] This relatively low total slightly outpaces the trend line from 2014, which saw the lowest number of enforcement letters–ten overall–in five years.[29]

Unfortunately, OPDP’s 2015 Untitled Letters shed no additional light on how FDA will tackle social media and other interactive media platforms in the wake of its long-awaited draft guidance last year on digital media. Although three of the seven letters OPDP issued in 2015 focus on electronic promotional platforms, each pertains only to traditional websites without addressing social media issues.[30]

The letters relating to companies’ websites indicate that FDA remains focused on frequently identified problems–misleading statements,[31] promotion of a drug for a new use for which it lacked approval,[32] and improper claims of superiority[33] in the Internet setting. Two other Untitled Letters relate to claims in other settings. In one letter, FDA expressed concern about a pharmacology aid for a drug used to treat major depressive and bipolar disorders; according to FDA, the aid implied unsubstantiated benefits over other approved treatments.[34] In a second, FDA faulted a pharmaceutical company for a banner it displayed at a booth at a pharmacists’ association conference because it omitted risk information.[35]

Untitled Letters continue to provide important insight into FDA enforcement. They also have been the target of criticism by stakeholders, and more recently, members of Congress. In a May 27, 2015 letter to FDA’s Acting Commissioner, Stephen Ostroff, Congressman Tim Murphy (R-PA) of the U.S. House of Representatives’ Energy and Commerce Committee wrote that "it is not clear that FDA’s practices are consistently fair, effective or efficient," both with respect to FDA’s posting of untitled letters and "whether sufficient details are included about the basis for FDA’s conclusion of a violation and the adequacy of notice of a violation."[36] The letter listed nine concerns regarding FDA’s use of untitled letters. For instance, Congressman Murphy asked whether FDA uses these letters "as a way to announce new regulatory approaches or policies," and if so, "what due process or other legal considerations apply."[37] He also noted that FDA’s practice of publicizing the letters may have economic and legal ramifications for publicly traded companies. Although he set a June 10, 2015 deadline for FDA to answer the inquiries, FDA’s public comments suggest that it intends to respond directly to the Congressman.[38] We will provide an update if FDA publishes a noteworthy response to Congressman Murphy’s critique.

B. FDA’s Draft Guidance

In February, FDA issued revised draft guidance regarding disclosure of risk information in drug promotions in the hope of ensuring that consumers can "make informed decisions about the medication being promoted."[39] With respect to risk information disclosures, FDA requires that (1) consumer-directed print advertisements include a brief summary of the product’s risks, and (2) promotional labeling set forth adequate directions for use of the product (which generally mandates inclusion of complete FDA-approved prescribing information).[40]

In its recent draft guidance, which updated draft guidance from 2004,[41] FDA articulated an alternative disclosure approach for consumer-directed prescription drug print advertisements and promotional labeling. The draft guidance refers to this alternative as a "consumer brief summary," which would "focus on the most important risk information rather than an exhaustive list of risks and that the information should be presented in a way most likely to be understood by consumers."[42]

Interestingly, FDA strongly recommended against drug companies following the agency’s current regulatory requirements requiring the dissemination of full prescribing information, in favor of the alternative approach outlined in the guidance. Based on data from an FDA survey and social science research, FDA reasoned that prescribing information is "written in highly technical medical terminology" for a health care provider audience, which can be difficult for the lay person to read and understand (if they read it at all).

C. Notable Litigation Relating to Promotional Issues

1. Off-Label Promotion and the First Amendment

For years, drug companies have worked to loosen FDA’s rules on off-label promotion; those efforts gained steam after the Second Circuit’s 2012 decision in United States v. Caronia,[43] which recognized that the First Amendment protects truthful, non-misleading off-label promotional speech. As we noted in our 2014 Year-End Update, 2015 may prove to be an important year for harmonizing FDA’s approach to off-label promotion with the First Amendment.

In March, the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of California dismissed FCA claims against Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc. based on allegations of off-label promotion. Although the defendants–and an amicus trade association, Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America ("PhRMA")–raised a First Amendment challenge to the allegations (and DOJ and relators responded), the decision did not discuss free-speech issues.[44]

Nevertheless, just a few weeks later, Amarin Pharma, Inc. ("Amarin"), a wholly owned subsidiary of Amarin Corporation, filed suit against FDA targeting restrictions on off-label communications with doctors.[45] The complaint, filed in the Southern District of New York by Amarin and four physicians, argues that FDA’s current policy on off-label promotion "severely restricts" health care professionals’ access to information about a prescription drug’s unapproved or off-label uses.[46] Plaintiffs assert that Amarin should be allowed to make truthful and non-misleading statements about off-label uses for products like its fish oil drug, Vascepa, including sharing that some clinical trials support certain off-label uses of the drug. In addition, the plaintiffs contend that FDA failed to provide fair notice of what off-label promotion, if any, is permitted following Caronia, in contravention of the plaintiffs’ Fifth Amendment rights.[47]

Developments off the docket may narrow the scope of the Amarin case considerably. In a June 8, 2015 letter, the Director of FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research ("CDER"), Janet Woodcock, asserted that many of Amarin’s proposed communications are currently within the scope of existing FDA guidance documents.[48] Specifically, FDA said that Amarin could communicate clinical trial results related to unapproved uses of Vascepa in accordance with existing guidance that governs acceptable methods to distribute journal articles concerning off-label indications, and Amarin may respond to unsolicited requests for off-label information.[49] Interestingly, FDA acknowledged that Amarin’s qualified health claim would be acceptable if Vascepa was repackaged as a dietary supplement.[50] FDA’s letter also suggested that Amarin should have addressed its concerns with the agency before filing suit "as other pharmaceutical companies sometimes do."[51]

A ruling in Amarin could clarify the impact of the Second Circuit’s 2012 ruling in Caronia,[52] but any such result does not appear imminent. In the meantime, FDA has stated that it intends to reevaluate its approach to product communications and that it will hold a public meeting regarding the confluence of the First Amendment, scientific exchange, and off-label communications.[53]

2. Off-Label Promotion and Federal Preemption

In cases involving state law tort or consumer protection claims against device manufacturers, the federal courts are frequently called upon to address the intersection of off-label promotion and federal preemption doctrine. By way of background, Congress enacted the Medical Device Amendments of 1976 ("MDA") to the FDCA to impose a regime of "detailed federal oversight for medical devices."[54] The MDA’s preemption clause expressly states that "no State . . . may establish . . . with respect to a device intended for human use any requirement–(1) which is different from, or in addition to, any requirement applicable under [the FDCA] to the device, and (2) which relates to the safety or effectiveness of the device or to any other matter included in a requirement applicable to the device under the [FDCA]."[55] As the Supreme Court has held, Class III PMA devices are subject to "device-specific" requirements for purposes of the MDA’s express preemption provision.[56]

In April, a divided panel of the Tenth Circuit held that the MDA preempts any effort to use state law to impose new requirements on certain federally approved medical devices, regardless of whether the device was being used on or off label.[57] In Caplinger v. Medtronic, Inc., a plaintiff brought a state law tort suit against a medical device manufacturer, alleging that the defendant and its representatives promoted the device for an off-label use, which use caused her injuries.[58] She argued that the fact that her suit was premised on an off-label use insulated her claims from preemption because the FDA’s approval of the device pertained only to on-label uses–and thus her suit would not impose requirements different from (or in addition to) FDCA requirements.[59] The court rejected this argument, noting that the text of the preemption provision in the MDA does not distinguish between on-label and off-label uses; rather, it preempts "any effort to use state law to impose a new requirement on a federally approved medical device."[60] Moreover, Congress spoke directly to off-label uses in a different provision of the FDCA, which allows doctors to prescribe–and patients to use–devices in an off-label manner. Yet Congress nevertheless preempted any state tort suit challenging the safety of a federally approved device "without qualification about the manner of its use."[61] Accordingly, the court held that the plaintiff’s claims were preempted, even though they targeted an off-label use that the manufacturer allegedly promoted.

Just as this issue split a Tenth Circuit panel in Caplinger, it has divided the federal courts. The full impact of Caplinger on device manufacturer defendants remains to be seen.

D. Legislative Developments

Following the wave of publicity and bipartisan support for the 21st Century Cures Act in early 2015, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the bill in a 344 to 77 vote on July 10, 2015.[62] The act is intended to modernize information collection and interoperability while streamlining the drug and device approval processes to ensure that patients have access to critical treatments as quickly as possible.

The 21st Century Cures Act seeks to improve communication among drug companies, health care providers, and other stakeholders. Section 2101 of the act would alter existing regulations that FDA imposes on manufacturers concerning off-label communications, explicitly including payors (in addition to formulary committees) in the permitted audience for health economic promotions.[63] The act also would relax the required connection between a drug claim and its FDA-approved indication; the new language would require the product claim to "relate," instead of "directly relate," to the indication.[64] Further, section 2102 would require FDA to issue draft guidance to facilitate the dissemination of scientific and medical information not otherwise included on drug labels, as long as the information is responsible, truthful, and non-misleading.[65] Although the 21st Century Cures Act would expand the ability of manufacturers to communicate about off-label uses, it would require manufacturers to state prominently the difference between the approved use and the off-label use in materials accompanying the product.[66] Many of the act’s provisions are aimed at loosening restrictions on promotional activity, leaving the details to later FDA guidance.

III. Developments in cGMP Regulations and Other Manufacturing Issues

The past six months were marked by two forceful displays of FDA’s authority with regard to manufacturing processes and quality oversight. In addition, FDA floated the possibility of adopting a more nuanced approach to FDA inspections overseas. These developments, and a few new draft guidance documents, are discussed below.

A. Notable cGMP Advisory and Enforcement Activity

1. Medtronic Enters a Consent Decree Related to Alleged QSR Violations

The past six months have already seen high-profile FDA advisory and enforcement action in connection with current good manufacturing practice ("cGMP") violations. In April, DOJ filed a consent decree imposing a permanent injunction on Medtronic Corporation ("Medtronic") and two of its executives in connection with the device maker’s SynchroMed II implantable infusion pump systems.[67] The complaint alleged Quality System Regulation ("QSR") violations related to the manufacture of the SynchroMed II pump that FDA observed during an April 2013 inspection (and similar alleged issues identified during prior inspections of Medtronic manufacturing facilities and in several Warning Letters that FDA issued to the company).[68] Under the proposed consent decree, Medtronic must cease the manufacture, design, and distribution of the SynchroMed II pump, except in "extraordinary cases," such as when a physician certifies that the device is medically necessary.[69] Medtronic must retain an expert to help develop and submit plans to the FDA to correct the violations. Medtronic may not resume the design, manufacture, and distribution of these products until FDA determines that the terms of the consent decree are satisfied.[70] Even after resumption of these activities, the company must continue to submit audit reports to FDA, and the Agency will continue to conduct inspections to verify compliance.[71] This recent consent decree underscores the significant consequences that can escalate from inspectional observations and FDA enforcement correspondence.

2. FDA Cites Extensive cGMP Compliance Issues at an NIH Facility

In June 2015, FDA issued an extensive Form 483 to one of the government’s own sites–the National Institutes of Health ("NIH")–following an inspection of a Maryland facility.[72] The Form 483 highlights the difficulty of cGMP compliance–particularly as it relates to aseptic operations. The Form 483 lists seventeen specific observations, including inappropriate investigations of non-sterility or potential sterility hazards, lack of a cGMP training program, and failure to perform container closure integrity testing for any sterile drug products.[73] The NIH facility at issue manufactures products for use in clinical research studies.[74] In response to the observations, the NIH announced that it had suspended sterile materials production operations in its Pharmaceutical Development Section.[75] The same press release also explained that in April, fungal contamination was found in two vials of albumin and that vials from the same batch as the contaminated vials had been administered to six patients. According to the NIH, none of those patients has developed signs of illness.[76]

Apart from its length and severity, the Form 483 issued to the NIH is unusual in that it was issued to a fellow entity within the Department of Health and Human Services ("HHS"). Given the nature and number of violations cited in the Form 483, the site may become the target of further enforcement scrutiny and action in the second half of 2015.

B. A Proposed "New Approach" to FDA Inspections

As we noted in our 2014 Year-End Update, the agency’s focus on global compliance with cGMP requirements has resulted in several actions against drugmakers from India in recent years.[77] In January 2015, the government of India requested that FDA allow Indian officials to accompany U.S. FDA investigators during inspections, reportedly in response to concerns regarding increases in FDA inspections and Form 483 observations for Indian drugmakers.[78]

After meetings with Indian regulatory authorities and drug manufacturers in March 2015, FDA’s Deputy Commissioner for Global Regulatory Operations and Policy and Director of CDER’s Office of Compliance wrote that India has not been "’singl[ed] out’ . . . for increased [FDA] inspections," but "that increased exports to the U.S. result in increased inspection, no matter where you are in the world."[79] Nevertheless, FDA officials announced that they had shared with Indian stakeholders a proposed "new approach to facility inspections" that would "not only note problems, but [would] also allow our inspectors to document where a firm’s quality management system exceeds what would be required to meet regulatory compliance."[80] Although the details are sparse, FDA stated that positive findings noted during inspections could affect the frequency of inspection for a facility "and possibly even support regulatory flexibility around post-approval manufacturing changes."[81] If FDA eventually implements a version of this "new approach" to facility inspections in the United States and abroad, it could provide significant incentives for manufacturers to develop and maintain best-in-class cGMP compliance programs.

C. cGMP Guidance Activity

FDA has already issued two draft guidance documents this year related to cGMP compliance:

- In January, FDA released draft guidance regarding cGMPs for combination products,[82] which are products comprised of any combination of a drug, device, or biological product.[83] This draft guidance clarifies how combination product manufacturers may comply with the applicable cGMP regulations set out in a January 2013 final rule.[84] Specifically, the new draft guidance discusses how combination product manufacturers can demonstrate compliance with the "streamlined" approach in 21 C.F.R. § 4.4(b) and provides hypothetical scenarios involving pre-filled syringes, drug-coated mesh, and a drug-eluting stent.[85]

- In May, FDA clarified which chemistry, manufacturing, and controls ("CMC") changes for drug and biologic products must be reported to the agency if altered post-approval.[86] In the guidance, FDA explained that the purpose of the guidance was, in part, to clarify that "certain CMC changes can be made solely under the Pharmaceutical Quality System without the need to report to FDA."[87]

IV. Medical Devices

Last year saw FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health ("CDRH") release its strategic priorities for 2014 and 2015. In the first six months of 2015, FDA followed through on some those stated priorities and continued to issue final and draft guidance that will impact medical device manufacturers. Below, we summarize the key developments for those in the device industry.

A. FDA Initiative to Reclassify Certain Devices

In our 2014 Year-End Update, we discussed FDA’s 2014 unveiling of its strategic priorities for 2014 and 2015–including FDA’s stated priority of "strik[ing] the right balance between premarket and postmarket data collection."[88] FDA reported its progress on one aspect of this mission in 2015, namely the effort to "review 50 percent of product codes subject to a [premarket approval ("PMA")] that have been on the market to determine whether or not to shift some premarket data collection to the postmarket setting or to pursue reclassification, and to communicate those decisions to the public."[89]

FDA reported that it exceeded its goal of reviewing 50% of subject product codes, ultimately reviewing 69% of product codes in 2014. Of those reviewed, FDA determined that 21 medical devices currently classified as Class III (i.e., PMA devices) were candidates for reclassification to Class II. An additional 21 devices were determined to be "candidates for reduction of premarket data collection through reliance on postmarket controls or shift of data collection from premarket to postmarket[,]" with FDA specifying its recommended changes.[90] Three devices were subject to reclassification or reduction in premarket data collection in 2014, and the remaining 96 product codes did not, in FDA’s view, warrant any change in classification.[91]

B. New FDA Guidance

During the first half of this year, FDA was prolific in issuing important final and draft guidance on key issues facing the medical device marketplace.

1. General Wellness and Low Risk Devices

On January 20, 2015, CDRH released draft guidance on "low risk products that promote a healthy lifestyle[,]" which CDRH refers to as "general wellness products."[92] According to the draft guidance, CDRH does not intend to examine these types of products for device classification or to determine whether they meet regulatory requirements.[93]

The draft guidance pertains specifically to products that either (1) have "an intended use that relates to maintaining or encouraging a general state of health or a healthy activity," or (2) have "an intended use claim that associates the role of a healthy lifestyle with helping to reduce the risk or impact of certain chronic diseases or conditions and where it is well understood and accepted that healthy lifestyle choices may play an important role in health outcomes for the disease or condition."[94] The first category relates to products that involve claims regarding general wellness but "do not make any reference to disease or conditions" (e.g., products with claims related to maintaining a healthy weight or promoting sleep management).[95] The second category encompasses products claimed to "help reduce the risk of" or "help living well with" certain chronic diseases or conditions, so long as "it is well understood that healthy lifestyle choices may reduce the risk or impact of the disease or condition."[96] Examples include products that promote physical activity to reduce the risk of heart disease or caloric intake trackers that help individuals with Type 2 diabetes.[97] Notably, this second category establishes a firmer footing for making disease-specific claims about low-risk products, without running afoul of FDA.

To fall within the scope of this draft guidance, products must be low risk.[98] According to the draft guidance, the product’s risk level depends on, among other factors, the invasiveness of the product, whether it poses risk if appropriate controls are not applied (e.g., sunlamp products), whether it raises "novel questions of usability," and whether it "raises questions of biocompatibility."[99]

2. Medical Device Accessories

Historically, FDA has exercised its jurisdiction over accessories to medical devices because the FDCA specifically includes the term "accessory" in its definition of "device."[100] Accordingly, FDA has frequently classified device accessories by inclusion in the same classification as the parent device, whether done through the 510(k) premarket notification process, through a PMA approval (if Class III), or by expressly including the accessory in the classification regulation or order for the parent device.[101] But such classifications may not always be appropriate because the device accessory may have a different risk profile that would make it eligible for a different classification from the parent device.

To help align its classification process with FDA’s "risk-based framework," CDRH and FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research ("CBER") released draft guidance in January to clarify FDA’s policy regarding the classification of device accessories and to encourage use of FDA’s de novo classification process.[102] In defining medical accessories, the draft guidance first asks whether the article is intended for use with one or more parent devices. Acknowledging that mobile phone platforms and off-the-shelf computer monitors displaying health data could fall into this definition, the draft guidance then asks whether the subject article is "intended to support, supplement, and/or augment the performance of one or more parent devices."[103] If an article falls into one of these three categories, FDA then would review the risks posed by the article on a standalone basis to determine its appropriate classification.

The draft guidance encourages submitters to go through FDA’s de novo classification process to obtain approval for marketing and selling an accessory, a recently revamped process that we discussed in our 2014 Year-End Update.

3. Medical Device Data Systems ("MDDS")

In our 2014 Year-End Update, we reported that FDA had issued draft guidance regarding its approach to MDDS "that transfer, store, convert formats, and display medical device data or medical imaging data."[104] FDA finalized this guidance in February, and it generally tracks last year’s draft guidance. Specifically, FDA "does not intend to enforce compliance with the regulatory controls that apply to [medical device data systems], medical image storage devices, and medical image communications devices, due to the low risk they pose to patients and the importance they play in advancing digital health."[105]

4. Laboratory Developed Tests – Updates and Developments

In our 2014 Year-End Update, we discussed FDA’s release of two guidance documents related to laboratory developed tests ("LDTs"), as well as percolating legal challenges and critical comments from industry. As FDA continues to seek to actively regulate LDTs, opposition has remained strong.

By way of background, LDTs are diagnostic tests designed, manufactured, and performed in clinical laboratories; examples include many of the tests used to diagnose genetic conditions. Historically, FDA has not actively regulated LDTs because it perceived little risk to patients associated with such tests.[106] In its recent draft guidance, FDA observed that, in the past, many LDTs were manufactured and used in a single patient-care institution–and they were produced using components that were legally marketed for clinical use.[107] Recognizing that changes in the manufacture and use of LDTs could potentially increase the risk to patients, FDA now seeks to promulgate a "risk-based framework" for certain types of LDTs, which would result in classification under FDA’s framework for classifying other medical devices.[108]

During a public workshop in January and the ensuing public comment period, which resulted in hundreds of comments, FDA fielded an array of pointed critiques of the proposed LDT framework.[109] Among the most active objectors was the American Clinical Laboratory Association ("ACLA"), which submitted a white paper arguing that FDA should withdraw the guidance.[110] ACLA contended that, inter alia, (1) LDTs cannot be regulated as devices because they are, in fact, services (and, thus, FDA lacks the statutory authority to regulate the tests); and (2) FDA has violated the Administrative Procedure Act by using so-called "guidance" documents rather than notice-and-comment rulemaking.[111]

FDA is still in the early skirmishes of what appears likely to be a long fight over the regulation of LDTs. We will continue to monitor and report on these developments.

5. Reusable Medical Devices

In March, CDRH and CBER released final guidance for industry regarding "Reprocessing Medical Devices in Health Care Settings: Validation Methods and Labeling."[112] The guidance, for which a draft was originally circulated in 2011, provides recommendations related to premarket notification ("510(k)") submissions, humanitarian device exemption ("HDE") applications, de novo requests, and investigational device exemption ("IDE") applications related to reprocessing reusable medical devices.

The guidance applies to four types of processing for reusable medical devices: (1) those that are "initially supplied as sterile to the user and requiring the user to reprocess" the device after initial use; (2) those that are "initially supplied as non-sterile to the user and requiring the user to process" them for initial use and after each use; (3) those that are "intended to be reused only by a single patient and intended to be reprocessed between each use"; and (4) "single-use medical devices initially supplied as non-sterile to the user, and requiring the user to process the device prior to its use."[113] For these types of devices, CDRH has set forth comprehensive labeling guidance, including guidance for implementing standard reprocessing instructions.[114] CDRH has also described the need to validate reprocessing instructions by performing tests to ensure that professionals tasked with reprocessing are able to carry out reprocessing instructions adequately.[115]

The guidance further sets forth the review process for any instructions provided in labeling at various stages of product development and FDA approval.[116]

6. Access to Devices for Unmet Medical Needs

In April, CDRH and CBER issued final guidance regarding "Expedited Access for Premarket Approval and De Novo Medical Devices Intended for Unmet Medical need for Life Threatening or Irreversibly Debilitating Diseases or Conditions[,]" less than a year after releasing draft guidance on the same topic.[117] The guidance establishes a voluntary "Expedited Access Pathway" program "for certain medical devices that demonstrate the potential to address unmet medical needs for life threatening or irreversibly debilitating diseases or conditions and are subject to PMAs or de novo requests."[118] If a device meets these criteria (which CDRH sets forth in more detail in the guidance), the device’s sponsor can submit a "Data Development Plan," which CDRH will review on an interactive basis (i.e., by "work[ing] with the sponsor so that the plan is developed in a manner that is least burdensome and predictable while allowing for some measure of flexibility and adjustments as appropriate.").[119] After a Data Development Plan has been developed and agreed on, the sponsor may seek priority review by submitting a premarket approval application ("PMA") or de novo request for the subject device, which will require FDA to make a classification determination for the device within 120 days.[120] FDA may require post-approval data collection, including clinical and nonclinical testing, as a condition for approval.[121]

7. Foreign Clinical Studies

In April, CDRH and CBER released draft guidance regarding "FDA’s policy of accepting scientifically valid clinical data from foreign clinical studies in support of premarket submissions for devices."[122] Under the Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act of 2012 ("FDASIA"), FDA is required to accept data from investigations conducted outside of the United States ("OUS" data) "if the applicant demonstrates that such data are adequate under applicable standards to support approval, licensure, or clearance of the drug or device in the United States."[123] If FDA does not find the data to be adequate, it must notify the sponsor of its finding and provide FDA’s rationale for the decision.[124] Although pre-FDASIA regulations specifically addressed OUS studies conducted in support of PMA applications, those regulations did not exist for other device submissions, and the draft guidance (along with a proposed rule)[125] is intended to expand and clarify the framework for the use of foreign clinical studies in evaluating 510(k) submissions, HDE applications, de novo applications, and IDE applications.[126] In particular, the draft guidance provides three "special considerations" when relying on OUS studies in support of a device approval submission; namely, differences in clinical conditions, study populations, and regulatory requirements.[127] The public comment period for the draft guidance closes on July 20, 2015.

8. Patient Preference Information Under PMA, HDE, or De Novo Review

Three years after CDRH issued guidance regarding "Factors to Consider When Making Benefit-Risk Determinations in Medical Device Premarket Approval and De Novo Classifications," FDA has taken another step in explaining what data measuring patient perspectives it may consider during PMA, HDE, and de novo review processes. In May, CDRH and CBER issued draft guidance on this topic, with the goals of "encourage[ing] voluntary submission of patient preference information," "outlin[ing] recommended qualities of patient preference studies," "provid[ing] recommendations for collecting patient preference information," and provid[ing] recommendations for including patient preference information in labeling for patients and health care professionals."[128]

The draft guidance document provides comprehensive advice on how industry might consider collecting patient preference information, submitting it to FDA, and including it in labeling decisions.

C. CDRH Warning Letters Demonstrate Enforcement Focus and Strategies

In the first half of 2015, CDRH issued eleven Warning Letters to device manufacturers for allegedly marketing their products without having appropriate clearances or approvals from FDA. Although each letter is unique, when viewed together, the letters reveal several trends with respect to FDA’s enforcement focus and strategy.

In late May and early June, CDRH issued four Warning Letters related to the marketing and sale of so-called "dermal fillers" without marketing clearance or approval.[129] In each of these four cases, FDA reviewed the website for the dermal filler–which is an injectable, often cosmetic, skin treatment–to determine the key ingredient in the filler and evaluate whether the product was being marketed as a treatment for various symptoms of aging or other applications without proper approval.[130] These letters suggest not only that the agency is focused on products in this space, but also that FDA is actively reviewing webpages to determine the nature and extent of marketing activities. It remains to be seen whether these letters mark the beginning of a trend of CDRH enforcement activities in this area.

Also in May and June, CDRH issued Warning Letters focusing on promotions of soft tissue reconstructive therapies to three separate companies.[131] In each case, the company had an approved use for its soft-tissue technology, but FDA alleged that the company was impermissibly promoting the technology for unapproved applications, such as breast reconstruction. Like the CDRH letters regarding dermal fillers, these letters are evidence of CDRH’s scrutiny of products in this space, and we will be watching this space carefully in the second half of the year for further developments.

Finally, CDRH’s Warning Letters thus far in 2015 provide a fresh reminder of the FDA’s broad jurisdiction over foreign companies that market products in the United States. Indeed, five of the eleven Warning Letters issued in the first half of 2015 targeted foreign companies (one Chinese, one British, one Armenian, and two Canadian), some of which appear to have had little more than a website aimed at the U.S. market.[132] In several cases, FDA evoked its authority to refuse entry of the devices into the United States until the companies addressed the alleged violations.

V. Anti-Kickback Statute

The AKS imposes criminal liability on companies or individuals that offer, pay, solicit, or receive "remuneration" to induce referrals of business that will be paid for by federal health care programs.[133] Any violation of the AKS also violates the civil monetary penalties law, and claims resulting from an AKS violation may trigger liability under the FCA, which imposes steep financial penalties.[134] The government has interpreted the term "remuneration" broadly "to cover the transferring of anything of value in any form or manner whatsoever,"[135] and theories of AKS liability can extend to just about any type of business arrangement between companies and health care professionals.

As government regulators and private plaintiffs continue to aggressively pursue alleged violations of the AKS, it remains as important as ever for drug and device companies to keep abreast of developments in this area of the law. In addition to the enforcement actions discussed in Part I above, several AKS-related developments over the past six months merit attention, as they reveal both the risks of compliance failures and strategies for managing those risks.

A. New AKS Safe Harbors Remain in Limbo, While HHS OIG Seeks New Ideas for Additional Safe Harbors

The surest way for companies to avoid the types of AKS settlements described above is to make sure any financial arrangements with providers fall under the statutory exceptions or regulatory "safe harbor" provisions that exempt certain conduct from the scope of the AKS.[136] As we reported in our 2014 Year-End Update, HHS OIG published a proposed rule in October 2014 that would create additional safe harbors under the AKS.[137] Since January, HHS OIG has fielded more than one hundred public comments on its proposed rule, and the agency has yet to finalize the rule. (According to HHS OIG, there is no timeline for when they might release the final rule.[138]) Given the complexity of the safe harbors, the sophistication of the public comments, and the changing landscape of the health care industry, it may be quite a while yet before the rule is finalized. In the meantime, as required by law,[139] HHS OIG put out its annual call for ideas about new safe harbors, seeking to tap the knowledge and real-world experience of industry participants.[140]

As HHS OIG finalizes its proposed rules and considers additional regulatory updates, we expect companies and HHS OIG to continue grappling with these important issues in the months and years to come, and it will behoove companies to track these developments carefully.

B. HHS OIG Advisory Opinion Regarding a Device Company’s Payments

In June, HHS OIG issued an advisory opinion regarding subsidies a device manufacturer provided to clinical research study participants.[141] The manufacturer had developed a system for minimally invasive outpatient back surgery, but the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services ("CMS") declined to cover the procedure because it was not "reasonable and necessary."[142] CMS allowed, however, that it would pay for patients enrolled in a clinical study designed to demonstrate the system’s efficacy.[143] As part of the clinical trial, and in order to protect the overall design of the trial, the manufacturer wanted to cover the cost of patient’s co-payments, and to pay the full cost of the procedure for individuals in the control group who originally received a "sham surgery" but later wanted to receive the actual procedure.[144]

HHS OIG decided that those payments could amount to prohibited remuneration[145] but determined nevertheless that the payments "present[ed] a minimal risk of fraud and abuse under" the AKS; therefore HHS OIG declined to impose administrative sanctions.[146] In reaching its conclusion, HHS OIG stressed that (1) the clinical study was small and limited to a "predetermined" number of patients; (2) the study was implemented at the behest of and in cooperation with CMS; (3) the payments were necessary to the design of the trial; and (4) any payments made to the physicians administering the study were made at fair market value.[147]

Like many past advisory opinions, this latest opinion highlights the complexity of navigating the AKS while implementing business measures aimed at meeting customer needs and researching and developing new treatments.

C. HHS OIG Guidance for Boards of Directors Highlights Need to Monitor Compliance with Anti-Kickback Laws

In April, HHS OIG released a report that it co-authored with several industry groups to provide guidance to governing boards at health care companies.[148] Among other things, the report highlighted HHS OIG’s expectation that directors will monitor compliance with the AKS and various other health care laws. As the report notes, the AKS and related statutes are "very broad," so "Boards of entities that have financial relationships with referral sources or recipients should ask how their organizations are reviewing these arrangements for compliance with the physician self-referral (Stark) and anti-kickback laws."[149] The report explains that "[t]here should also be a clear understanding between the Board and management as to how the entity will approach and implement those relationships and what level of risk is acceptable in such arrangements."[150]

D. Now in Its Second Year, the Open Payments Database Draws a Large Audience

Mandated by PPACA’s Physician Payments Sunshine Act provisions, the "Open Payments" database is an online repository of information about payments made by drug and device manufacturers and group purchasing organizations to physicians and teaching hospitals. The goal of this database is to increase transparency and accountability with regard to relationships among certain industry participants and providers by requiring drug and device manufacturers to self-report annually any payments made to a physician or teaching hospital.[151]

As reported in our 2014 Year-End Update, in September 2014 CMS released the first round of data from the Open Payments database, encompassing six months’ worth of data from 2013. In April, CMS released a new report to Congress detailing its efforts to implement the Open Payments database, but did not include any new data for 2014.[152] As scheduled, CMS released the 2014 data, the first full year of data available, by the end of June 2015.[153] Going forward, CMS will report on the payments annually.

Notably, CMS’s April report provided a glimpse into just how much attention and use the Open Payments website received last year. In the fourth quarter of 2014 alone, "close to 1 million visitors accessed Open Payments data through the search or Data Explorer tool."[154] During a single week in February 2015, the Open Payments search tool and data explorer received approximately 2.5 million unique page views from site visitors."[155]

Although companies may delay publication of certain information to protect sensitive business information related to research and development or clinical trials,[156] the Open Payments database otherwise imposes a sweeping obligation on drug and device companies to report their payments to certain providers. And it is clear from the website traffic that people are paying attention. Companies would be wise to assume that the Open Payments database provides a trove of data for prosecutors, government regulators, and plaintiff’s attorneys.

VI. Drug Development and Clinical Trials

After approving 41 new pharmaceutical products for marketing in 2014–the second highest number in history–FDA approved new drugs at a similar pace during the first six months of 2015. With 25 new drug approvals to date, 2015 may well be a record-breaking year.[157] The rate of new approvals appears to reflect FDA’s recent efforts to accelerate its review process. In keeping with these efforts, FDA spent the first half of 2015 soliciting comments and issuing policies and procedures intended to increase the efficiency of industry clinical trials and the agency’s own drug review and approval processes.

Given the government’s stated commitment to expediting the review and approval of safe and effective essential drugs, 2014’s trend of increased guidance and legislation aimed at accelerating drug trials and approvals appears likely to continue throughout 2015.

A. Guidance on Improving Efficiency of Clinical Trials and Drug Approvals

Thus far in 2015, FDA has released two draft, and one finalized, guidance documents aimed at increasing the efficiency of clinical trials:

- Use of Electronic Informed Consent in Clinical Investigations: In March 2015, FDA released its draft guidance on the use of electronic informed consent to facilitate clinical trials. The draft guidance proposes the use of "electronic systems and processes that may employ . . . electronic media . . . to convey information related to the study [to participants] and to obtain and document informed consent."[158] According to the draft guidance, the use of electronic informed consent may improve the efficiency of clinical trials by "promot[ing] timely entry of any [electronic informed consent] data into the study database and allow[ing] for timely collection of the subject’s informed consent data from remote locations."[159]

- Clinical Trial Imaging Endpoint Process Standards: Many clinical trials rely on medical imaging to demonstrate the efficacy of a drug. In recognition of that fact, FDA released a draft guidance document in March 2015 that is intended "to assist sponsors in optimizing the quality of imaging data obtained in clinical trials intended to support approval of drugs and biological products."[160] To that end, the draft guidance recommends the creation of trial-specific imaging process standards (i.e. those "that extend beyond those typically performed in the medical care of a patient") when a medical image serves as a trial’s endpoint (i.e., a measure of drug efficacy).[161]

- Critical Path Innovation Meeting: Back in 2004, FDA published a report addressing challenges and opportunities in the drug development pipeline.[162] Since then, the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research ("CDER") developed the concept of Critical Path Innovation Meetings ("CPIM") as a means to foster communication among industry investigators, "academia, patient advocacy groups, and government" regarding strategies to improve efficiency in drug development.[163] In April 2015, FDA released a final guidance document that "describes the purpose, scope, documentation, and administrative procedures for a [CPIM]."[164] It remains to be seen whether this initiative will result in efficiency gains for industry.

In addition to these guidance documents, FDA issued a request in February 2015 for input regarding the development and use of biomarkers, which FDA defines as "objective characteristic[s] that [are] measured and evaluated as . . . indicator[s] of normal biologic processes, pathogenic processes, or pharmacologic responses to treatment."[165] According to FDA, biomarkers can facilitate clinical trials by identifying the most effective populations for study and by signaling proper dose selections and adverse effects.[166]

Thus far in 2015, FDA’s efforts have focused not only on expediting clinical trials but also on improving its own processes for reviewing drug approval applications. In May, FDA also released its finalized guidance regarding the conservation of FDA resources related to the review of Abbreviated New Drug Application ("ANDA") submissions. In this final guidance, FDA outlined potential ANDA deficiencies that may elicit a "refuse-to-receive" decision (i.e., a rejection of the ANDA because the applicant failed to include necessary information).[167] By enhancing its refuse-to-receive standards, FDA intends to conserve recourses by eliminating the need to "repair" incomplete ANDAs, a process that it considers "inherently inefficient and wasteful of resources."[168]

Further, in March 2015, FDA released policies and procedures related to breakthrough therapy drug applications.[169] The release outlined the factors that FDA will consider in determining whether a breakthrough therapy drug warrants expedited review.[170]

B. Developments in Biosimilar Approval Pathway Regime

As discussed in our 2014 Year-End Update, one of the government’s initiatives is to pave the way for more treatments to reach the market through the approval pathway under the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act ("BPCIA"). The BPCIA allows for an "abbreviated licensure pathway for biological products that are demonstrated to be ‘biosimilar’ to or ‘interchangeable’ with an FDA-licensed biological product."[171] In February 2015, FDA elicited comments regarding information that it intends to collect in connection with licensure applications for biosimilars and proposed interchangeable products.[172]

Based on the notice and section 351(k) of the Public Health Service Act, as amended by BPCIA, FDA anticipates that these applications will include a significant amount of information regarding the product’s biosimilarity to a reference product, mechanisms of action, conditions of recommended use, dosages, and manufacturing processes.[173] Indeed, FDA estimated that responding to a section 351(k) application for a proposed biosimilar product will take FDA roughly 860 hours. The same is true for FDA to issue a decision regarding interchangeability, a decision which depends on the applicant’s ability to demonstrate that the biologic "can be expected to produce the same clinical result as the reference product in any given patient," "without the intervention of the prescribing health care provider."[174] Because FDA has a concerted interest in reducing its response time for these applications, we are hopeful that future guidance will clarify how these application processes may be streamlined.

Although the biosimilarity approval process is evolving, it has already produced an approval. In March, FDA approved the first biosimilar application for Sandoz Inc.’s Zarxio, a non-brand, complex biosimilar of Amgen’s blockbuster drug Neupogen. Because Sandoz did not seek to have Zarxio classified as interchangeable with Neupogen, it remains to be seen what supporting data FDA will require for such a demonstration.

In the meantime, in April 2015, FDA released three finalized guidance documents regarding biosimilar applications:

- Scientific Considerations in Demonstrating Biosimilarity to a Reference Product: In this final guidance, FDA described the type of studies and data that should support a showing of biosimilarity: (1) extensive structural and functional characterization of the proposed product and the reference product; (2) animal studies; (3) comparative human pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics studies; (4) clinical immunogenicity assessment; and, if necessary, (5) additional clinical data needed to address any uncertainty about biosimilarity.[175] According to the final guidance, applicants should gather the necessary data sequentially to allow for mid-process adjustments based on results from the preceding steps.[176] FDA clarified that it will assess this data using a totality-of-the-evidence approach to determine whether there are any clinically material differences between the biosimilar and the reference product.[177]

- Quality Considerations in Demonstrating Biosimilarity of a Therapeutic Protein Product to a Reference Product: FDA recommends that a biosimilar applicant "use appropriate analytical methodology that has adequate sensitivity and specificity to detect and characterize differences between the proposed product and the reference product" when conducting biosimilarity studies.[178] Furthermore, the guidance lists the following factors that applicants should consider when developing biosimilarity studies: expression system; manufacturing process; assessment of physicochemical properties; functional activities; receptor binding and immunochemical properties; impurities; reference product and reference standards; finished drug product; and stability.[179]

- Q&A Regarding Implementation of the BPCIA: In this guidance document, FDA addressed a number of questions related to the biosimilarity application process. For example, FDA provided information regarding the types of differences between the biosimilar and the reference products that will not derail an application.[180] FDA clarified that biosimilar and reference product need not have identical formulations or delivery device or container closure systems.[181] Nor must the biosimilar and reference products treat all the same conditions or share all the same routes of administration.[182]

In May, FDA issued draft guidance outlining additional questions and answers regarding the BPCIA.[183] This document answers questions concerning a variety of issues such as the length of time applicants should retain samples of the biologic products used in their comparative studies.[184] It also indicates that applicants should not seek a determination of both biosimilarity and interchangeability in the same application as "it would be difficult as a scientific matter for a prospective biosimilar applicant to establish interchangeability in an original [section] 351(k) application given the statutory standard for interchangeability and the sequential nature of that assessment."[185] Although useful in some regards, the draft guidance does not elaborate on the data needed to demonstrate interchangeability.[186]

C. Proposed Legislation

As reported in our 2014 Year-End Update, the 114th Congress seems determined to improve clinical trials and drug approval processes as well as to increase access to life-saving drugs. Most notably, this past May 19 alone saw the introduction of the 21st Century Cures Act and seventeen separate bills to amend the FDCA.[187] Also proposed were some novel regulations on the pharmaceutical industry. We have surveyed the most significant bills below.

1. 21st Century Cures Act (H.R. 6)

As discussed in our 2014 Year End Update and above, the 21st Century Cures Act aims to modernize drug approvals by implementing innovative statistical methods (e.g., Bayesian analyses) in clinical trials, accelerating approvals for drugs targeting life-threatening illnesses and unmet needs, increasing the development of biomarkers, and incorporating patient experience into FDA’s decision-making processes.[188] Just days ago, the House passed the bill with broad bipartisan support.[189] If this support carries the bill through the Senate, we will provide an update at that time.

In addition to giving pharmaceutical companies a multitude of new tools to expedite the approval process for drugs, the act would allow manufacturers greater ability to use previously approved drugs for new, cancer-treatment indications.[190] Of course, the act seeks to balance access and safety; various provisions would require companies taking advantage of the expanded access program, which facilitates the provision of drugs to patients on a compassionate basis before they are fully approved, to abide by increased transparency requirements.[191]

If the 21st Century Cures Act is enacted, the device approval process also would undergo efficiency-increasing amendments. Those changes include establishing a third-party quality review system for more efficient review,[192] broadening the scope of acceptable evidence,[193] normalizing the FDA standards with national and international organizations,[194] expediting the evaluation of approved devices for alternate uses,[195] and approving devices for rare diseases (affecting less than 8,000 people) after the manufacturer demonstrates the device’s safety, but not necessarily its efficacy.[196] The act would establish priority review for "breakthrough devices," which treat life-threatening or irreversibly debilitating conditions.[197] Moreover, the act would implement a framework for regulation of new technologies, including mobile applications and health software.[198]

The 21st Century Cures Act contains several provisions pertaining to the testing and manufacture of pharmaceuticals. The act would promote antibiotic and vaccine development,[199] provide incentives for manufacturers to research drugs for rare populations,[200] and allow U.S. pharmaceutical companies to re-export drugs from a second country.[201] In addition, one provision of the act is intended to harmonize the Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects (i.e., the "Common Rule") with the FDCA. Another would give manufacturers greater flexibility in the approval process by eliminating the need for informed consent if there is minimal risk and the patients’ rights have other safeguards.[202]

Aside from the provisions intended to expedite industry efforts to test and bring to market new drugs and devices, the act also would provide the NIH a $2 billion "Innovation Fund" for new research related to biomarkers, precision medicine, infectious diseases, and antibiotics.[203]

Importantly, the 21st Century Cures Act also provides that within eighteen months of its enactment, the Secretary of Health and Human Services must issue draft guidance on the responsible dissemination of truthful and non-misleading scientific and medical information that is not within the FDA-approved labeling of drugs and devices.[204] This provision prompts FDA to update its position regarding the permissible contours of off-label promotion, particularly in light of the recent string of First Amendment challenges to restrictions on off-label promotion, described above.

2. Other Proposed Legislation

The 21st Century Cures Act has drawn the most attention over the past six months, but Congress has been quite busy with other bills as well. Several notable pieces of proposed legislation are discussed below:

- Promise for Antibiotics and Therapeutics for Health Act ("PATH") (S. 185): At the beginning of this year, legislation was introduced to the Senate that would accelerate the approval of drugs aimed at treating serious or life-threatening conditions and addressing unmet needs.[205] The impetus for the bill is the growing threat of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, which have been blamed for the deaths of at least 23,000 Americans per year.[206]

- Improving Regulatory Transparency for New Medical Therapies Act (H.R. 639): Similar to the proposed Regulatory Transparency, Patient Access, and Effective Drug Enforcement Act discussed in our Year-End Update, in an effort to reduce approval delays, this bill would provide a strict timeline to the Drug Enforcement Administration ("DEA") by which to schedule new drugs.[207] The bill, which passed the House by voice vote on March 16, would also amend the Controlled Substance Act, the FDCA, and the exclusivity patent laws to ensure that drug manufacturers do not lose exclusivity time as a result of DEA scheduling delays.[208]

- Medical Innovation Act of 2015 (S. 320): Introduced into the Senate in February, this bill proposes a controversial new mechanism to boost NIH and FDA funding. The bill would require manufactures of blockbuster drugs that enter into certain government settlements to pay a portion of their profits to the NIH and FDA over a period of five years.[209] Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) likens the bill’s unprecedented fundraising mechanism to a "swear jar."[210] The funds would be allocated to "meet urgent needs in medical research."[211] Thus far, the bill has not been warmly received by the industry, which believes that the law would threaten, rather than incentivize, biopharmaceutical innovation.[212]

- Research for All Act (H.R. 2101): As discussed in our 2014 Year-End Update, this bill, reintroduced into the House this May, is concerned with the representation of women in clinical trials and medical research to ensure the safety of expedited drugs for female use. The bill would require that clinical trials conducted in support of expedited drug approvals be "sufficient to determine the safety and effectiveness of such products for men and women using subgroup analysis."[213] The bill also broadens the definition of drugs eligible for expedited review to include drugs which are substantially safer for "men or women than a currently available product approved to treat the general population or the other sex."[214] There is concern among industry participants that the law’s requirements would increase the cost of clinical trials as well as delay drug approvals.[215]

VII. Conclusion

As we predicted back in January, this year DOJ and FDA have coordinated and sustained their regulatory trend lines from 2014. If those trends continue–and we have no reason to forecast any imminent reduction in enforcement and regulatory activity–the remainder of 2015 will underscore the compliance challenges that drug and device companies must confront each day. In the meantime, the first half of 2015 has given industry participants plenty to digest in terms of new regulatory developments. As the year’s developments play out, we will monitor them closely and report back to you in in our 2015 Year-End Update.

[1] See Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Assistant Attorney General Leslie R. Caldwell Delivers Remarks at the American Bar Association’s 25th Annual National Institute on Health Care Fraud (May 14, 2015), available at http://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/assistant-attorney-general-leslie-r-caldwell-delivers-remarks-american-bar-association-s.

[2] Id.

[3] Id.

[4] See Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Daiichi Sankyo Inc. Agrees to Pay $39 Million to Settle Kickback Allegations Under the False Claims Act (Jan. 9, 2015), available at http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/daiichi-sankyo-inc-agrees-pay-39-million-settle-kickback-allegations-under-false-claims-act.

[5] Id.

[6] See Corporate Integrity Agreement Between the Office of Inspector General of the Department of Health and Human Services and Daiichi Sankyo, Inc., available at https://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/cia/agreements/Daiichi_Sankyo_01072015.pdf.

[7] See Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, AstraZeneca to Pay $7.9 Million to Resolve Kickback Allegations (Feb. 11, 2015), available at http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/astrazeneca-pay-79-million-resolve-kickback-allegations.

[8] See Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Medco to Pay $7.9 Million to Resolve Kickback Allegations (May 20, 2015), available at http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/medco-pay-79-million-resolve-kickback-allegations. For more information about this settlement, see our forthcoming 2015 Mid-Year Health Care Compliance and Enforcement Update – Providers.

[9] See Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Medtronic Inc. to Pay $2.8 Million to Resolve False Claims Act Allegations Related to "SubQ Stimulation" Procedures (Feb. 6, 2015), available at http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/medtronic-inc-pay-28-million-resolve-false-claims-act-allegations-related-subq-stimulation; Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Manhattan U.S. Attorney Settles Civil Fraud Claims Against Inspire Pharmaceuticals, Inc. For Its Misleading Marketing Designed To Cause Prescriptions Of Azasite For Non-FDA Approved Uses (June 17, 2015), available at http://www.justice.gov/usao-sdny/pr/manhattan-us-attorney-settles-civil-fraud-claims-against-inspire-pharmaceuticals-inc.

[10] See Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Inc., To Pay $5.9 Million To Resolve Civil False Claims Act Allegations (May 13, 2015), available at http://www.justice.gov/usao-edpa/pr/siemens-medical-solutions-usa-inc-pay-59-million-resolve-civil-false-claims-act.

[11] See Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Medtronic to Pay $4.41 Million to Resolve Allegations that it Unlawfully Sold Medical Devices Manufactured Overseas (Apr. 2, 2015), available at http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/medtronic-pay-441-million-resolve-allegations-it-unlawfully-sold-medical-devices-manufactured.

[12] See Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Minnesota-Based ev3 to Pay United States $1.25 Million to Settle False Claims Act Allegations (Feb. 5, 2015), available at http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/minnesota-based-ev3-pay-united-states-125-million-settle-false-claims-act-allegations.