July 27, 2016

From the Supreme Court to the Congress and from the federal agencies to the state legislatures, 2016 has produced noteworthy legal and regulatory developments for companies in the pharmaceutical and medical device industries.

Like our 2015 Year-End FDA and Health Care Compliance and Enforcement Update, this update begins with an overview of government enforcement efforts against drug and device companies under the False Claims Act ("FCA"), the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act ("FDCA"), and other laws. We then address evolving regulatory guidance and other action on topics of note to drug and device companies: promotional activities, manufacturing practices, product development, and the Anti-Kickback Statute ("AKS"). After detailing certain developments of particular note to device manufacturers, we address the drug pricing issues that drew significant attention in the first half of 2016.

I. Department of Justice Enforcement in the Drug and Device Industries

During the first half of 2016, the Department of Justice ("DOJ") continued its active enforcement of civil and criminal laws–including the FCA, FDCA, and Foreign Corrupt Practices Act ("FCPA")–against drug and device companies. This activity included two blockbuster settlements in excess of $500 million: (1) the largest AKS resolution in history, a $646 million settlement to resolve AKS and FCPA allegations relating to a device manufacturer and (2) a $784 million settlement resolving a long-running investigation into allegedly improper Medicaid billing by two major pharmaceutical companies.

A. False Claims Act

Two critical developments in the first six months of 2016 will have significant ramifications for DOJ enforcement of the FCA against drug and device companies.

First, in June, the Supreme Court decided Universal Health Services, Inc. v. United States ex rel. Escobar, a case that presented two issues: (1) whether a defendant’s "implied false certification" of compliance with statutory, regulatory, or contractual requirements is a proper basis for liability under the FCA, and (2) whether that liability must be premised on express "conditions of payment."[1] The Court concluded that the "implied certification theory" is actionable in FCA litigation, at least (but perhaps only) where there has been an express statement on a claim for payment that is rendered false by the "omission" of disclosure regarding a violation of a law, rule, or regulation.[2] The Court also held that only "material" omissions are actionable and elaborated on the FCA’s "rigorous" and "demanding" materiality requirement.[3]

Universal Health Services may well have a material impact on off-label promotion cases: the DOJ or relators will have to show that statements in prescription and reimbursement paperwork are somehow rendered misleading by some material omission. But the case may also crack open the door for claims based on purported violations of U.S. Food & Drug Administration ("FDA") regulations that are not expressly identified as conditions of payment by government health care programs.

Second, June 2016 also brought sobering news regarding future civil FCA penalties, which are set to more than double on August 1, 2016. As we noted in our 2015 Year-End Update, the Federal Civil Penalties Inflation Adjustment Improvements Act of 2015 requires heads of federal agencies to adjust civil monetary penalties no later than July 1, 2016, and no later than January 15 of each year thereafter.[4] On June 30, 2016, the DOJ announced the first "catch up adjustment" (as required by the Federal Civil Penalties Inflation Adjustment Improvements Act of 2015); this adjustment will hike civil FCA penalties to a minimum of $10,781 and a maximum of $21,563.[5] Notably, the DOJ intends to impose these increased penalties on conduct that took place on or after November 2, 2015 (the date that the law requiring increased penalties was enacted).[6] Alleged acts occurring before November 2, 2015 are still subject to the prior $5,500 to $11,000 penalty range.[7]

This staggering increase in potential liability may lead to larger FCA judgments and settlements for drug and device companies given that cases against them tend to involve allegations regarding thousands of claims. At the very least, the penalty increases may give the DOJ even more leverage to force resolutions. But defendants are likely to challenge these dramatic increases under the excessive fines clause of the Eighth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.[8]

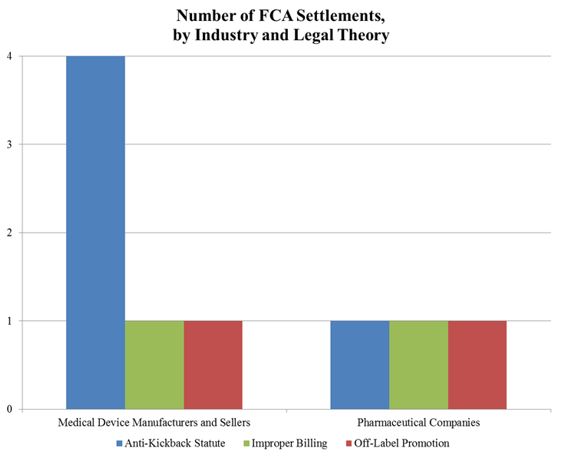

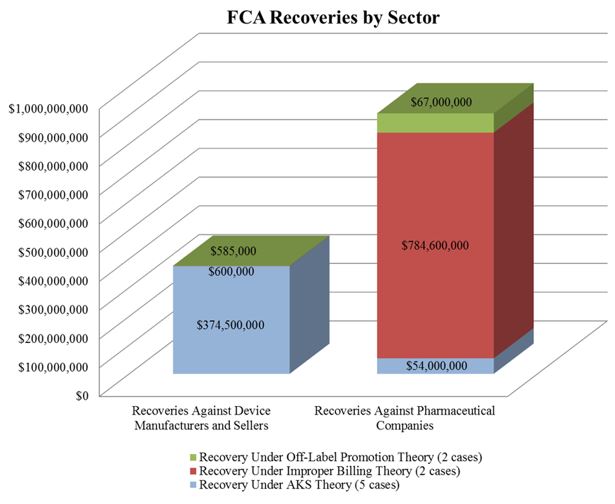

In the meantime, the DOJ’s FCA enforcement activity plowed forward in the first six months of the year. With nine FCA resolutions against drug and device makers thus far in 2016, the DOJ is on track to surpass the 15 FCA enforcement actions it resolved last year. The nine actions resulted in $1.28 billion in recoveries from drug and device companies, almost doubling last year’s total of over $653 million. As we noted in our 2015 Year-End Update, the DOJ continues to advance AKS theories in many settled matters. As the chart below shows, over half of the DOJ’s total recoveries to date in 2016, and two-thirds of recoveries from device manufacturers, have resulted from alleged AKS violations.

The DOJ’s aggressive pursuit of AKS theories against drug and device companies appears to be at the expense of FCA matters predicated on off-label promotion. Indeed, the DOJ has announced only two off-label resolutions in 2016. It is still too early to tell whether the slowdown in off-label promotion actions is a byproduct of effective corporate compliance programs or a refocusing of DOJ resources (in light of courts’ expanding recognition of a First Amendment right to engage in truthful, non-misleading, off-label promotion), or a combination of the two. We will address the downward trend in off-label promotion enforcement actions in greater detail below.

1. Settlements in AKS-Related FCA Matters

The increase in AKS enforcement that we have tracked in recent years continued unabated over the last six months. The DOJ’s settlement with Olympus Corporation ("Olympus") sets a new high-water mark. The DOJ alleged that Olympus, the largest distributor of endoscopes in the United States, paid kickbacks to doctors and hospitals in the United States and Latin America.[9] The total amount of the settlement was $646 million–$623.2 million to resolve AKS claims under the FCA and $22.8 million to resolve FCPA allegations.[10] This resolution is both the largest AKS-based FCA settlement and the largest settlement by a medical device company in U.S. history.[11]

In another notable settlement, Respironics Inc., a manufacturer of sleep apnea masks, agreed to pay $34.8 million in March to resolve FCA claims predicated on alleged AKS violations.[12] Respironics allegedly provided free call center services to suppliers if patients were using Respironics masks, but required the suppliers to pay a monthly fee to use the call center for patients using competitors’ masks.[13] The Respironics settlement demonstrates the reach of the AKS, which the DOJ and relators alike have applied to forms of alleged remuneration well beyond straight cash payments.

2. Resolution of Off-Label Promotion Investigations

As discussed further in Section II, below, courts have continued to recognize that the First Amendment protects truthful, non-misleading speech. So it is perhaps unsurprising that the largest settlement of an off-label promotion investigation thus far this year focused on the purportedly false and misleading aspects of the alleged promotional conduct. On June 6, 2016, Genentech Inc. and OSI Pharmaceuticals Inc. entered into a $67 million settlement to resolve allegations that they misled physicians and health care providers as to the effectiveness of the cancer drug Tarceva (and thereby violated the FCA).[14] The government alleged that between January 2006 and December 2011, the defendants made misleading statements about Tarceva’s effectiveness in treating non-small cell lung cancer when, in fact (according to the government), the drug was only effective if the patient had never smoked or possessed a certain genetic mutation.[15] The federal government received $62.6 million and Medicaid received $4.4 million of the total settlement.

In March, Cardiovascular Systems, Inc. ("CSI") announced an agreement with a relator and the United States to settle a qui tam FCA action regarding an alleged kickback and off-label marketing scheme.[16] According to the complaint, CSI actively marketed its catheters, which had only been approved for use below the waist, for use in coronary arteries and veins.[17] Notably, the complaint further alleged that CSI misrepresented the risks associated with certain off-label uses of its devices. The agreement provided that the company would pay $8 million to the U.S. government over a three-year period in exchange for a stipulation of dismissal.[18]

3. Settlements of Cases Based on Other FCA Theories

In April, the DOJ entered into a settlement with Wyeth and Pfizer, Inc. to resolve allegations that Wyeth avoided paying rebates to Medicaid from 2001 to 2006 by reporting inaccurate prices of two of its proton pump inhibitor ("PPI") drugs used to treat acid reflux–Protonix Oral and Protonix IV.[19] Medicaid requires drug companies both to report the "Best Price" of each of its drugs to commercial customers and to pay rebates calculated based in part on Best Price to state Medicaid programs.[20] According to the government’s complaint, Wyeth violated this requirement by offering hospitals "deep discounts" if they bought both Protonix drugs in a bundle, and did not report this discounted price to the government.[21] Wyeth and Pfizer Inc. agreed to pay $784.6 million to settle the claim.[22] The federal government received $413 million, and state Medicaid programs received $371 million.[23]

B. FDCA Enforcement Actions

To date in 2016, the DOJ’s FDCA enforcement actions have involved allegations of marketing products without FDA approval, introducing misbranded drugs or devices into interstate commerce, and failing to comply with current good manufacturing practice ("cGMP") rules.

1. Marketing Unapproved and Misbranded Drugs and Devices

In February, a federal grand jury in the District of Nevada indicted an individual for allegedly importing thousands of contact lenses from China and South Korea; the indictment asserts that the lenses were misbranded because they bore counterfeit trademarks and were contaminated with bacteria.[24] The defendant was prosecuted as part of "Operation Double Vision," an ongoing effort among federal agencies, including FDA, to combat the illegal importation of counterfeit and unapproved contact lenses.[25]

Also in February, the DOJ entered a consent decree in the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Florida, permanently enjoining an individual from distributing unapproved drugs marketed as a "natural herpes medicine" that would "Stop Herpes Outbreaks."[26] The drug, Viruxo, had not been approved by FDA as safe and effective for the treatment of herpes, and no well-controlled clinical studies substantiated these claims.[27] Pursuant to the consent decree, the individual agreed to cease selling Viruxo and to seek FDA permission before selling or distributing any food or drug product in the future.[28]

Finally, in May, an individual pleaded guilty in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of California to one count of introducing an unapproved drug into interstate commerce.[29] According to the information and plea agreement, the defendant marketed and sold 2,4‑Dinitrophenol ("DNP"), a chemical used as a dye, wood preserver, and herbicide, as an extreme weight loss drug.[30] A Rhode Island customer died in October 2013 after ingesting DNP, though the government conceded it could not prove that DNP caused the customer’s death.[31]

2. Marketing without Approval and cGMPs

During the last six months, the DOJ has enforced current Good Manufacturing Practices ("cGMP") provisions against several compounding pharmacies and their owners and employees. In January, two pharmacists formerly employed by Meds IV, a now-defunct compounding pharmacy in Alabama, pleaded guilty to criminal violations of the FDCA.[32] According to the criminal information, Meds IV compounded a liquid nutrition drug using an amino acid adulterated with bacteria, which caused bloodstream infections in several patients, nine of whom died.[33] The two pharmacists pleaded guilty to two misdemeanor counts of adulterating drugs while held for sale, representing the two lots of amino acid determined to be contaminated.[34] On June 21, 2016, the pharmacists were each sentenced to 10 to 12 months in prison.[35]

In April, the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Florida entered a permanent injunction against the owner and operator of Franck’s Lab Inc. for introducing adulterated and misbranded drugs into interstate commerce.[36] The complaint alleged that on, several occasions, Franck’s Lab, doing business under various names, distributed purportedly sterile drugs which were adulterated.[37] For example, following reports of eye infections from patients who had been injected with a solution prepared by Franck’s Lab, FDA inspections revealed unsanitary conditions within the lab, including the presence of dead insects above the sterile preparation area and a lack of sufficient physical barriers to prevent contamination.[38] The complaint further alleged that because the purportedly sterile drugs contained microbiological contamination, the labeling for the drugs was false and misleading.[39]

Finally, in May, B. Braun Medical Inc. settled criminal charges for selling contaminated saline flush syringes in 2007.[40] Although B. Braun did not manufacture the syringes, the DOJ alleged that Braun had been aware of problems with the manufacturer’s process before it began purchasing the syringes; two employees of the manufacturer had already received prison sentences in 2009 for conspiracy to commit violations of the FDCA.[41] In addition to paying $7.8 million in penalties and restitution, B. Braun signed a non-prosecution agreement in which it agreed to increase oversight of its suppliers.[42]

3. Recent Park Doctrine Developments

Just weeks ago, the Eighth Circuit upheld a district court decision in United States v. DeCoster that imposed a three-month prison sentence and $100,000 fine on the owner and chief operating officer of Quality Egg LLC. for FDCA violations related to a salmonella outbreak traced to the company’s eggs.[43]

The decision explored the somewhat hazy contours of the Park doctrine (i.e., the responsible corporate officer doctrine), which permits the government to pursue misdemeanor FDCA charges against individual officers who were in a position to prevent or correct an FDCA violation.[44] Notably, the Eighth Circuit’s ruling in DeCoster addressed some critical questions left unanswered by United States v. Park, the forty-year old ruling that established the doctrine.[45]

The court concluded, for instance, that imprisonment would violate principles of due process if premised solely on vicarious liability.[46] In coming to that conclusion, however, the panel’s three judges each wrote separate opinions, which leave the court’s reasoning less than clear. Particularly murky–and open to further interpretation–are the court’s conclusions regarding the requisite mindset for liability under the Park doctrine. Two judges indicated that negligence was sufficient, but the third opined that individual liability requires intent. Given its significant implications for the industry, we will continue to follow this ruling on its journey to potential en banc and/or Supreme Court review.

C. FCPA Investigations

1. Drug Companies

To date in 2016, the government has signaled that it is scrutinizing drug companies for their operations abroad. On February 19, 2016, Kara Brockmeyer, Chief of the SEC’s FCPA Unit, announced at a PLI conference that the Commission is "going back to the pharma industry after a break for a period of years."[47] According to Ms. Brockmeyer, the industry is having a difficult time addressing FCPA-related risks.[48] The SEC’s call for increased scrutiny of pharmaceutical companies comes on the heels of the $14 million settlement with Bristol-Meyers Squibb that we discussed in our 2015 Year-End Update. Since then, the SEC has settled FCPA enforcement actions against SciClone and Novartis involving alleged conduct in China and actions against Nordion and its former employee, Mikhail Gourevitch, involving alleged conduct in Russia.

In February, SciClone agreed to pay the SEC $12.8 million to settle allegations that its subsidiary, SciClone Pharmaceuticals International Ltd. ("SPIL"), made improper payments to health care professionals ("HCPs") employed by state-owned hospitals in China.[49] According to the SEC, internal SPIL reports revealed that sales representatives provided weekend trips, vacations, gifts, expensive meals, foreign language classes, and entertainment to HCPs to persuade them to prescribe SciClone products.[50] As part of the settlement, SciClone agreed to provide periodic status reports over the next three years about its continued remediation efforts and new anti-corruption measures.[51]

Less than two months later, the SEC resolved a similar enforcement action against Novartis, which agreed to pay $25 million for allegedly bribing Chinese government officials (mostly HCPs) in purported "pay-to-prescribe" schemes involving Novartis products.[52] The SEC claimed that, from 2011 to 2013, Novartis China used third parties (usually travel agents) to facilitate bribes in the form of transportation, accommodations, venue payments, and meals related to "educational conferences and other business activities."[53] These bribes were then allegedly recorded as "legitimate selling and marketing costs."[54] As part of the settlement, Novartis agreed to provide periodic updates to the SEC over the next two years.[55]

In two other FCPA actions involving third-party agents, the SEC settled actions in March against Nordion (Canada) Inc., a global health sciences company, for $375,000[56] and its former employee, Mikhail Gourevitch, for approximately $180,000.[57] The SEC claimed that improper payments were made to a third-party agent, a childhood friend of Mr. Gourevitch, to allow Nordion to obtain Russian government approval for, register, license, and distribute a liver cancer treatment.[58] From 2005 through 2011, Nordion allegedly paid the agent about $235,000, and the agent, in turn, paid Mr. Gourevitch at least $100,000 in kickbacks.[59]

2. Device Companies

FCPA enforcement actions involving device companies have kept pace with actions targeting drug companies. As noted above, the DOJ announced in March that Olympus agreed to pay $22.8 million to settle FCPA-related charges (in addition to its large AKS-related payment).[60] The DOJ claimed that, from 2006 until August 2011, Olympus Latin America ("OLA") paid nearly $3 million to HCPs in Central and South America to induce the purchase of Olympus products (resulting in more than $7.5 million in profit).[61] The DOJ and OLA entered into a separate three-year deferred prosecution agreement under which OLA will have a compliance monitor.[62]

In June, the DOJ and the SEC entered into separate settlements with Analogic subsidiary BK Medical, a manufacturer of ultrasound equipment headquartered in Denmark.[63] According to the SEC, from 2001 to early 2011, BK Medical "allowed itself to be used as a slush fund for its distributors, funneling millions of dollars around the world at its distributors’ direction without knowing the purpose of the payments or anything about the recipients."[64] The SEC alleged that one Russian distributor channeled at least some of these payments to doctors employed by Russian state-owned entities.[65] BK Medical agreed to pay $7.67 million in disgorgement and $3.8 million in prejudgment interest to resolve the SEC’s allegations.[66] As to the DOJ’s investigation, BK Medical agreed to enter into a non-prosecution agreement ("NPA") and pay a $3.4 million penalty.[67]

Further details regarding the current international anti-corruption enforcement climate are available in our 2016 Mid-Year FCPA Update.

II. Promotional Issues

Since the Second Circuit’s and Southern District of New York’s respective decisions in Caronia and Amarin,[68] First Amendment jurisprudence regarding FDA’s authority to regulate off-label promotional speech has continued to evolve. As expected, these landmark decisions have emboldened drug and device manufacturers to challenge FDA’s enforcement authority related to off-label promotion, leaving FDA seemingly reluctant to regulate in the area. Below, we discuss how this developing area of law has continued to impact the industry in the first half of 2016. In particular, this section summarizes recent FDA enforcement actions, guidance documents, litigation, and legislative activities related to promotional activities.

A. FDA Enforcement Activity – Advertising and Promotion

In our 2015 Year-End Update, we reported a steep decline in FDA enforcement related to advertising and promotion. That trend has continued in 2016. So far this year, FDA’s Office of Prescription Drug Promotion ("OPDP") has issued only one Warning Letter and one Untitled Letter[69]–a pace which, if continued, will yield a record low of enforcement letters by year end.[70] Although FDA has not provided any explanation for this notable drop in OPDP enforcement, the recent First Amendment cases are likely having an impact.

OPDP’s two enforcement letters this year focus on the omission and/or minimization of risk information:

- January 14, 2016 Untitled Letter: In a January Untitled Letter, OPDP found that Hospira, Inc.’s YouTube video promoting Precedex injections–a drug indicated for sedation of initially intubated and mechanically ventilated patients in intensive care–omitted risks and material facts associated with the drug. According to OPDP, the video contained numerous efficacy claims, but omitted relevant risk information and material information regarding the FDA-approved indication for Precedex.[71]

- March 29, 2016 Warning Letter: In March, OPDP issued its only Warning Letter thus far in 2016. The letter warned that the "Patient Co-Pay Assistance Voucher" for Shionogi Inc.’s Ulesfia lotion, indicated for topical treatment of head lice infestation, failed to communicate any risks related to Ulesfia and omitted information about its limitations of use.[72]

B. FDA’s Promotional Guidance

Despite FDA’s 2014 promise to issue guidance regarding off-label promotion and scientific communications in light of "the evolving legal landscape in the area of the First Amendment," the industry still eagerly awaits such guidance.[73]

FDA did recently announce plans to study the use and impact of animation in television commercials for prescription drugs as a result of concerns that animated characters impede patient comprehension of risk and benefit information.[74] Regulators announced their intent to conduct surveys involving animated advertisements for two fictional drugs[75]; it remains to be seen whether the survey results will lead FDA to alter its policies regarding the format and content of television commercials for prescription drugs.

According to FDA’s Guidance Agenda, CDER plans to publish the following guidances in 2016 in the advertising arena: (1) Health Care Economic Information in Promotional Labeling and Advertising for Prescription Drugs Under Section 114 of the Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act, (2) Internet/Social Media Advertising and Promotional Labeling of Prescription Drugs and Medical Devices – Use of Links to Third-Party Sites, (3) Manufacturer Communications Regarding Unapproved, Unlicensed, or Uncleared Uses of Approved, Licensed, or Cleared Human Drugs, Biologics, Animal Drugs and Medical Devices, and (4) Presenting Risk Information in Prescription Drugs and Medical Devices Promotion (Revised Draft).[76] We will track the release of these guidances and report back in our 2016 Year-End Update.

C. Notable Litigation Relating to Promotional Issues

As noted in our client alert regarding the Amarin decision, the Southern District of New York relied on the Second Circuit’s landmark decision in Caronia[77] to hold that the First Amendment precludes an interpretation of the FDCA that would criminalize or prohibit truthful and non-misleading off-label speech.[78] Consequently, FDA agreed in a March 8, 2016 settlement with Amarin to be bound by the Court’s conclusion that Amarin’s promotion of the off-label use of Vascepa constitutes truthful and non-misleading speech protected by the First Amendment.[79] In exchange for FDA’s concession that the company may continue to engage in such off-label promotion, Amarin agreed to "bear the responsibility, going forward, of assuring that its communications to doctors regarding off-label use of Vascepa remain truthful and non-misleading."[80] The agreement outlined a special procedure for FDA to give "preclearance" review to up to two promotional communications annually, through 2020, regarding off-label uses of Vascepa.[81]

The broader impact of Caronia and Amarin can be seen in the jury instructions used in the most significant off-label litigation in the first half of 2016, United States v. Vascular Solutions, Inc. In this criminal trial, the Western District of Texas instructed the jury that it is "not a crime for a device company or its representatives to give doctors wholly truthful and non-misleading information about the unapproved use of a device."[82] Consequently, the jury acquitted the company and its CEO of all charges in February 2016.[83] This decision suggests that the Second Circuit’s interpretation of the First Amendment (as it applies to off-label promotion) is spreading.

Moreover, Vascular Solutions involved the question of whether using the device at issue to treat perforator veins in fact constituted an off-label use or whether it fell within the device’s approved general use for treatment of varicose veins.[84] Like Vascular Solutions, companies often believe the use of a drug or device falls under the umbrella of a product’s approved general intended use statement and therefore constitutes an on-label use–the government, however, will disagree if the specific use in question was not studied in support of FDA’s approval. The outcome of Vascular Solutions–which suggests such distinctions may no longer be significant in cases where there is no false or misleading speech–perhaps signals a victory for the industry on this front as well.

Although this line of cases finds truthful and non-misleading off-label promotional speech protected by the First Amendment, what constitutes misleading speech remains an open question. It is also important to bear in mind that these cases, although certainly relevant to advertising and promotional issues generally, specifically regard speech and do not directly address promotional conduct.

The first half of 2016 also saw signs that the courts may limit the scope of FCA enforcement relating to promotional activity. First, the Second Circuit issued an opinion in United States ex rel. Polansky v. Pfizer suggesting that the government cannot predicate an FCA suit solely on a manufacturer’s off-label promotion.[85] There, the plaintiff alleged that Pfizer, Inc. violated the FCA by marketing its drug Lipitor to patients whose cholesterol levels were below the FDA approved cutoff for receiving the drug. The Second Circuit affirmed the lower court’s dismissal of the action and added this noteworthy commentary:

[I]t is unclear just whom Pfizer could have caused to submit a ‘false or fraudulent’ claim: The physician is permitted to issue off‐label prescriptions; the patient follows the physician’s advice, and likely does not know whether the use is off‐label; and the script does not inform the pharmacy at which the prescription will be filled whether the use is on‐label or off. We do not decide the case on this ground, but we are dubious of Polansky’s assumption that any one of these participants in the relevant transactions would have knowingly, impliedly certified that any prescription for Lipitor was for an on‐label use.[86]

Although this language is certainly favorable to drug and device companies facing FCA claims based on a theory of off-label promotion, the court was careful to add the caveat that where "it would be obvious to anyone" that the promoted use is not FDA-approved, FCA claims may survive a motion to dismiss.[87] Accordingly, it seems the Second Circuit believes that some off-label promotion may expose companies to FCA liability.

Second, in April, a Texas jury absolved Abbott Laboratories ("Abbott") of liability in an FCA case filed by a former employee, Kevin Colquitt.[88] Colquitt alleged that Abbott violated the FCA by encouraging doctors to use, and bill for, its biliary stents for peripheral vascular or arterial disease–an unapproved use.[89] Although Colquitt’s expert testified that 99% of Abbott’s stent sales were for off-label uses, the jury found that Abbott had not violated the FCA.[90] We will be following this area of jurisprudence closely for further insight into how off-label promotion may be regulated going forward.

D. Legislative Developments

Congress also joined the off-label fray in the first half of 2016. In a May 26, 2016 letter to the Department of Health and Human Services ("HHS"), the Committee on Energy and Commerce expressed its "concerns" with respect to the position HHS has taken on FDA regulation of "proactive dissemination of truthful and non-misleading information that is outside the scope of a [medical] product’s FDA-approved labeling."[91] The Committee declared that prohibiting manufacturers from proactively providing "scientifically accurate" off-label information is "no longer sound public policy" and does not survive constitutional scrutiny, citing litigation that "has raised significant questions about FDA’s authority to restrict such communication."[92] Furthermore, the Committee scolded FDA for its "unwillingness or inability to publicly clarify its current thinking on these issues in a coherent manner."[93] Interestingly, the Committee suggested that HHS was blocking the development of a clear policy on off-label promotion, stating that "it is our understanding that HHS has not allowed FDA to issue its completed draft guidance."[94] The letter also noted that FDA’s regulatory policy regarding off-label promotion currently is being made through a settlement agreement, as opposed to FDA rulemaking or guidance–an approach criticized as "ad hoc" and "lacking any semblance of consistency and cohesiveness."[95] The Committee also provided a discussion draft of a proposed amendment to the FDCA that would leave manufacturers room to disseminate off-label use information.

Separately, as reported in our 2015 Year-End Update and discussed in further detail below, since the U.S. House of Representatives passed the 21st Century Cures Act, the Senate has been working on its own version of the bill. On April 6, 2016, the U.S. Senate Committee for Health, Education, Labor and Pensions approved the last of the 19 bipartisan pieces of legislation that will become the Senate companion to the Act.[96] Committee Chairman Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.) announced on July 11, 2016 that the Senate should finish its work on 21st Century Cures in September.[97] We will continue to follow the evolution of this bill, in particular the provisions aimed at loosening restrictions on promotional activity.

III. Developments in cGMP Regulations and Other Manufacturing Issues

Data integrity emerged as one of the clearest cGMP compliance themes over the past six months, as FDA issued new draft guidance and sent warning letters to multiple international facilities addressing data integrity issues. Since our last update, FDA also exercised greater oversight of outsourcing facilities, including through warning letters sent to multiple domestic 503B outsourcing facilities for cGMP violations. Outside of the administrative context, the DOJ has continued to pursue enforcement actions, including a notable high-profile criminal settlement against a company accused of distributing adulterated products that were manufactured by a third-party supplier.

A. Notable cGMP Compliance and Enforcement Activity

1. NIH Suspends Production at Two Facilities, Hires Consultants

In our 2015 Mid-Year Update, we discussed FDA’s unusual issuance of a Form 483 to a National Institutes of Health ("NIH") site. FDA’s inspection found several cGMP violations, particularly for equipment used to maintain aseptic conditions relating to air flow in the facility.[98] In April 2016, NIH announced that it suspended production at two of its facilities producing sterile products and hired two consultants to bring its practices and standards into cGMP compliance.[99] These measures resulted in postponement of several clinical trials.[100]

2. FDA Issues Multiple Warning Letters Addressing Data Integrity

FDA’s focus in the first half of 2016 on data integrity compliance issues resulted in warning letters to several international manufacturing facilities in countries including China, Germany, India, and Italy. These letters also underscore FDA’s recent increase in foreign inspection activity.[101]

One letter was particularly severe: FDA’s April 2016 letter to Sri Krishna Pharmaceuticals Ltd. detailed multiple alleged violations of the contract manufacturer’s protocols and methodologies, including the company’s lack of compliance with its own written production and process procedures, a lack of control over its computer systems, and a failure to maintain sufficient data or adequate records of its manufacturing processes.[102] For instance, FDA asserted that laboratory analysts logged in to laboratory instruments using a generic username and without a password so data could never be traced directly to any particular analyst.[103] Further, according to FDA, some laboratory software was incapable of supporting audit trails while the audit function had been disabled on other equipment.[104] On one occasion, during a data backup, metadata with audit trails was not preserved and was subsequently lost in a system crash.[105] FDA found that certain violations, such as doctored test results and falsified data, were intentionally deceptive.[106] The warning letter called for an extensive corrective process, including a full third-party investigation, a thorough risk assessment, and a detailed action plan.[107]

In May, Chinese firm Tai Heng Industry Co. received a similar warning letter focused in part on data integrity after an FDA investigation found that the company simply discarded unacceptable batch sample test results, retesting the samples until better results were obtained.[108] According to FDA, this led the firm to rely on "incomplete records to evaluate the quality of [the] drugs and to determine whether [the] drugs conformed with established specifications and standards."[109] FDA directly addressed these issues in its April 2016 draft guidance on data integrity, discussed below.[110]

In May 2016, German manufacturer BBT Biotech GmbH received a warning letter detailing production problems for its active pharmaceutical ingredients, including a lack of testing and quality reviews.[111] Data integrity was also a factor as the firm purportedly failed to exercise control over computer systems sufficient to prevent data alterations and unauthorized access.[112] Within the same week, Italian company Corden Pharma Latina S.p.A. received a similar letter, having "failed to establish laboratory controls that include[d] . . . appropriate specifications, standards, sampling plans, and test procedures designed to assure . . . appropriate standards."[113]

3. FDA Issues Warning Letters to Outsourcing Facilities for cGMP Violations

At least twenty pharmacies have received FDA warning letters to date this year based on deficiencies in sterile drug manufacturing practices identified during Form 483 inspections.[114] Several of those manufacturers were registered as section 503B "outsourcing facilities,"[115] which became subject to federal oversight through the Drug Quality and Security Act in 2013.[116] As a result of FDA’s recent draft guidance on pharmacy compounding that expanded the agency’s interpretation of "outsourcing facility," discussed in detail below, it appears likely that there will be an increase in the number of enforcement actions targeting these manufacturers.

4. CMS Imposes Sanctions on Theranos and its CEO

Blood testing company Theranos received an enforcement letter from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services ("CMS") in the wake of its Form 483 inspection last year.[117] In April 2016, CMS initially proposed sanctions against the laboratory’s Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 ("CLIA") certificate.[118] CMS found that Theranos violated certain laboratory condition requirements, causing "immediate jeopardy to patient health and safety."[119] In a July 7, 2016 letter, CMS imposed sanctions including revocation of the company’s license to operate a lab in California because of unsafe practices, and monetary penalties of $10,000 per day until all deficiencies identified by CMS have been corrected.[120] CMS also took the notable step of banning the company’s CEO and founder from the blood-testing business for a period of at least two years;[121] this sanction underscores that executives may find themselves on the hook for serious violations. Theranos may request a hearing before a Departmental Appeals Board administrative law judge within 60 days of the letter’s receipt to appeal the CLIA revocation and related penalties such as the CEO’s ban.[122] However, cancellation of the laboratory’s approval to receive Medicare or Medicaid payments will take place on September 5, 2016, regardless of any timely appeal.[123]

5. Two Sterile Drug Producers Enter Consent Decrees Related to Alleged cGMP Violations

In the last six months, the DOJ entered two notable consent decrees at FDA’s request. First, in January 2016, the Northern District of Texas imposed a permanent injunction on Downing Labs and three individuals (the company’s two owners and the pharmacist-in-charge).[124] The complaint alleged failures to maintain sterile conditions while manufacturing sterile drugs.[125] Problems allegedly included "excessively high levels of endotoxins" and "various microorganisms" in the drugs.[126] The defendants were enjoined from manufacturing, holding, or distributing drugs for human use produced at the facility until it is in full compliance with the FDCA, its associated regulations, and the consent decree.[127] The injunction also gave FDA the power to order the recall and destruction of drugs manufactured by Downing Labs.[128]

As we discussed earlier, in April 2016, the Middle District of Florida entered a permanent injunction against Paul W. Franck, owner of Franck’s Lab Inc. (doing business as Trinity Care Solutions) for failure to maintain sterile conditions while manufacturing sterile drugs, causing the drugs to become adulterated.[129] Particularly problematic was the compounding pharmacy’s injectable sterile eye solution, which was linked to "47 cases of eye infections among 45 patients in nine states."[130] As part of the agreement, Franck must report all adverse effects of the adulterated drugs to FDA.[131]

6. Medical Device Manufacturer B. Braun Resolves Criminal Liability for Distributing Adulterated Syringes Manufactured by Product Supplier

Another DOJ enforcement action imposing criminal liability related to cGMP violations underscored the need for manufacturers to monitor the GMPs of their suppliers and other partners. As discussed above, Braun Medical Inc. ("Braun"), a German medical device manufacturer, agreed to pay $4.8 million in forfeitures and penalties, and as much as $3 million in restitution, to resolve alleged criminal liability for the sale of adulterated syringes filled with a contaminated saline solution.[132] Braun did not manufacture the Braun-labeled syringes but rather bought them from North Carolina-based supplier AM2PAT.[133] Nevertheless, the DOJ stressed that companies are "prohibit[ed] from selling contaminated products, even when the company did not make the product itself[,]" and that "[c]ompanies must take reasonable steps to ensure that their suppliers are making quality products that help rather than harm patients."[134] At the time that it purchased the syringes, Braun was allegedly aware that AM2PAT had experienced difficulties with its manufacturing processes.[135] Although an audit revealed cGMP compliance issues at AM2PAT, Braun proceeded with using AM2PAT as its product.[136]

B. cGMP Rulemaking and Guidance Activity

1. FDA Draft Guidance

Thus far, FDA has issued draft guidance this year on two of the hottest topics in cGMP compliance–data integrity and compounding:

- In April 2016, FDA published draft guidance entitled Data Integrity and Compliance with CGMP, highlighting its increasing focus on data integrity issues, which are often observed during cGMP inspections.[137] The guidance addresses issues such as effective data management strategies, audits, sampling, and testing. It defines "data integrity" as "the completeness, consistency, and accuracy of data," and advises that "[c]omplete, consistent, and accurate data should be attributable, legible, contemporaneously recorded, original or a true copy, and accurate[.]"[138]

- In April 2016, FDA issued draft guidance addressing pharmacy compounding.[139] The draft guidance expands FDA’s interpretation of what facilities are considered to be "outsourcing facilities."[140] This definition is important because facilities that are considered "outsourcing facilities" are subject to the stricter cGMP requirements that apply to drug manufacturers.[141] Under the expanded definition, fewer facilities can qualify for exemptions from cGMPs for pharmacies under section 503A of the FDCA (as amended by the Drug Quality and Security Act).[142] The draft guidance also states that a manufacturer cannot qualify for this exemption "by segregating or subdividing compounding within an outsourcing facility."[143] Rather, suites within the same "geographic location or address" are considered to be a single "outsourcing facility."[144] FDA explained that there might otherwise be confusion over what manufacturing standards were used for a particular drug if compounding under both sections were allowed within the same location or address (for instance, compounding under 503A in one suite and under 503B in another).[145]

2. FDA’s Proposed Rule for Minimum cGMP Requirements for Outsourcing Facility Compounding

In May 2016, FDA announced a proposed rule, 0910-AH09, for publication in December (delayed from its original release date of July 2015), which will "set forth the minimum . . . cGMP . . . requirements for human drug products compounded by an outsourcing facility."[146]

FDA also announced that it will issue a final rule, 0910-AH08, in July 2016 which will "update and amend the list of drug products . . . that may not be compounded because [they] have been withdrawn or removed from the market" due to safety or efficacy issues.[147]

IV. Medical Devices

As previewed in our 2015 Year-End Update, FDA and the Center for Devices and Radiological Health ("CDRH") announced a number of strategic priorities for 2016 related to the regulation of medical devices. These priorities include: CDRH’s intent to develop a National Evaluation System for Medical Devices; its commitment to "partner[ing] with patients" and increasing patient feedback and preferences in the clinical trial and device approval processes; and its goal of "promot[ing] a culture of quality and organizational excellence."[148] CDRH has made progress on some of these priorities, while also unveiling a number of other initiatives to date this year.

For instance, the FDA Commissioner has advocated for the creation of a National System of Evidence Generation ("EvGen") to facilitate data sharing by establishing interoperable systems and enabling collaboration among groups that generate data.[149] FDA also has launched a "lean management process mapping approach" to improve the review of combination products.[150] This approach would involve analyses of existing agency review practices to identify sources of delay and redundancy, and to develop more streamlined processes.[151] Lastly, CDRH and the Regulatory Science Subcommittee ("RSS") have developed a list of the top ten regulatory science needs of 2016 related to medical devices in the hope of creating a "cyclical regulatory science prioritization and implementation model to best serve the Center’s mission, vision and use of Center resources."[152] These needs include: leveraging "Big Data" and developing computational modelling technologies to support regulatory decision making; enhancing digital health and medical device cybersecurity; and incorporating human factors engineering principles into device design.[153]

We summarize below these and other key developments from the first half of 2016, including newly released guidance documents, developments in FDA’s proposed regulation of Laboratory Developed Tests ("LDTs"), proposed rules, enforcement actions, and legislative developments related to devices.

A. FDA Guidance

CDRH has already issued a significant number of important final and draft guidance documents on a wide range of issues in the first half of this year.

1. Public Notification of "Emerging Signals"

On December 31, 2015, FDA released draft guidance to describe its policy on notifying the public about "emerging signals."[154] FDA defines an "emerging signal" as new information about a medical device used in clinical practice that (a) the agency is monitoring or analyzing, (b) has the potential to impact patient management decisions and/or alter the known benefit-risk profile of the device, (c) has not yet been fully validated or confirmed, and (d) the agency does not yet have specific recommendations for.[155] Emerging signals may include such things as newly recognized types of adverse events, increases in the reporting of a known event, new product-to-product interactions, device malfunctions, patient injuries, or reduced benefits for patients.[156] The draft guidance proposes criteria, timeframes, and methods of communication with FDA to address emerging signals.[157]

In the draft guidance, FDA notes that timely communication of emerging signals is critical to informing treatment choices.[158] Although the agency recognizes that emerging signal information may cause patients to unnecessarily avoid or stop using beneficial devices, FDA nevertheless emphasizes that the benefits of early communication outweigh the risks.[159]

2. Postmarket Management of Cybersecurity

In late January, FDA issued draft guidance related to the management of postmarket cybersecurity vulnerabilities as a complement to the agency’s final guidance on premarket cybersecurity submissions which we discussed in our 2014 Year End Update.[160] This draft guidance pertains specifically to medical devices that contain software (including firmware) or programmable logic, as well as software that is itself a medical device.[161] It does not apply to experimental or investigational medical devices.[162] The purpose of the guidance is to encourage manufacturers to identify and address cybersecurity risks throughout the lifecycle of a device. Accordingly, the draft guidance deems it "essential" that manufacturers continue to implement comprehensive cybersecurity risk management programs and documentation consistent with the Quality System Regulations after a medical device has entered the market.[163]

Such programs address weaknesses which may permit the unauthorized access, modification, misuse or denial of use of medical devices or information stored, accessed, or transferred from medical devices.[164] In the draft guidance, FDA outlines steps that manufacturers can take to manage these risks and recommends incorporating elements consistent with the NIST Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity.[165]

3. Interoperable Medical Devices

In draft guidance published in late January, FDA encourages the development of safe and effective interoperable devices to increase the efficiency of patient care.[166] Interoperable medical devices "have the ability to exchange and use information through an electronic data interface with another medical device, product, technology, or system," which can greatly improve patient care.[167] But the draft guidance cautions that the transmission of inadequate, untimely, or misleading information from one medical device to another can put patients at significant risk.[168] Consequently, FDA highlights specific design considerations that device manufacturers should take into account, including performance testing and risk management activities.[169] The draft guidance also provides recommendations for the content of premarket submissions,[170] as well as a detailed list of suggested labeling content.[171]

4. Postmarket Surveillance under Section 522

In mid-May, FDA finalized guidance from 2011 regarding section 522 of the FDCA.[172] That section grants FDA the authority to require medical device manufacturers who produce certain Class II or III devices to conduct postmarket surveillance studies.[173] FDA’s guidance explains how device manufacturers may fulfill certain section 522 procedural obligations.[174] The guidance provides clarification on when FDA is authorized to require postmarket surveillance and the process by which FDA determines that postmarket surveillance is warranted.[175] Further, it contains detailed recommendations for postmarket surveillance plans and postmarket surveillance reports.[176] FDA emphasizes that noncompliance with the requirements of section 522 is prohibited by the FDCA, will render the device misbranded, and may lead to enforcement actions "including seizure of product, injunction, prosecution, and/or civil money penalties."[177]

5. Human Factors

FDA issued two guidance documents relating to human factors in early February. First, FDA finalized guidance from 2011 regarding when and how to use human factors and usability engineering to design medical devices.[178] The purpose of human factors and usability engineering is to understand how people interact with technology and how user interface designs affect those interactions.[179] This guidance focuses on the design of user interfaces, which include all points of interaction between the product and user.[180] FDA recommends that manufacturers follow certain engineering processes to ensure that potential user errors "that could cause harm or degrade medical treatment are either eliminated or reduced to the extent possible."[181] Further, FDA provides that where risk analyses indicate potential harm, manufacturers should submit human factors data in premarket submissions.[182]

On the same day, FDA also released draft guidance listing the types of devices for which human factors data should be included in premarket submissions.[183] The draft guidance focuses on devices that have a "clear potential for serious harm resulting from use error" based on information found in Medical Device Reporting ("MDRs") and recall information.[184] The guidance document states that manufacturers of the listed devices should provide FDA with "a report . . . that summarizes the human factors or usability engineering processes they have followed," or a detailed explanation of why human factors data is not necessary.[185] For devices not included on the list, submissions should include human factors data "if analysis of risk indicates that users performing tasks incorrectly or failing to perform tasks could result in serious harm."[186]

6. Risk-Benefit Factors for Postmarket Compliance Decisions

In June, FDA released draft guidance shedding light on its exercise of enforcement discretion regarding postmarket compliance violations.[187] FDA’s new draft guidance provides "the benefit and risk factors FDA may consider in prioritizing resources for compliance and enforcement efforts to maximize medical device quality and patient safety."[188] In assessing these factors–which include the type and magnitude of the device’s benefit, patient preference for the benefit, medical necessity of the device, and the severity and likelihood of, and patient tolerance for, the relevant risk–FDA "may consider relevant, reliable information relating to patient perspectives on what constitutes meaningful benefit, what constitutes risk, and what tradeoffs patients are willing to accept . . . as well as what alternatives are available."[189] FDA "may also consider the manufacturer’s approach to minimize harm or to mitigate the increased risks that result from regulatory non-compliance or nonconformity of the product, their compliance history, and the scope of the issue."[190] The draft guidance further provides examples of situations in which FDA has considered the enumerated risk-benefit factors before taking enforcement action.[191]

B. Recent Developments in the Regulation of Laboratory Developed Tests

As reported in our 2015 Year-End Update, LDTs–diagnostic tests designed, manufactured, and performed in clinical laboratories–have recently become the subject of significant industry debate. FDA considers LDTs to be in vitro diagnostics and therefore "devices" under the FDCA, but the agency has historically exercised its enforcement discretion to forego regulation in this area.[192] In response to the increased use and complexity of these tests in recent years–particularly in relation to genetic testing–FDA announced a proposal to impose stricter regulatory oversight.

In 2014, FDA released draft guidance establishing a tiered, "risk-based framework" that would classify LDTs under FDA’s current classification system for medical devices.[193] FDA has not issued final guidance. In a hearing held by the House Energy and Commerce Committee’s Subcommittee on Health last year, CDRH Director Jeffrey Shuren testified that FDA plans to move forward with such guidance sometime in 2016.[194] After FDA releases final guidance, the agency has stated, initial enforcement efforts will focus on reviewing LDTs with the same intended use as cleared or approved companion diagnostics or approved Class III devices, as well as certain LDTs that determine the safety or efficacy of blood or blood products.[195] In the meantime, FDA recommends that laboratories developing LDTs be prepared to prove clinical and analytical validity with clear data to facilitate the review process once finalized.[196]

C. Third-Party Refurbishment

In March, FDA elicited comments regarding its proposed rule for "the medical device industry and healthcare community that refurbish, recondition, rebuild, remarket, remanufacture, service, and repair medical devices."[197] FDA noted that it was taking action in response to concerns from various stakeholders regarding the quality, safety, and continued effectiveness of devices that have been subject to one or more of these processes.[198] According to FDA, there is a particular risk that third-party entities may use unqualified personnel, inadequately document the work performed, disable device safety features, and operate devices improperly.[199] FDA is seeking input regarding the benefits and risks related to these activities, as well as assistance in defining certain terms in the proposed rule.[200]

D. Enforcement Trends

1. Enforcement Letters

In the first half of 2016, CDRH issued fourteen enforcement letters, two of which were directed to foreign device manufacturers.[201] Of the 76 violations cited in the letters, 71 relate to failures to comply with Quality Systems regulations.[202] The most frequently cited of these violations involve failures to develop adequate validation processes, to establish and maintain sufficient CAPA procedures, and to manage and address complaints properly.[203]

The remaining five violations relate to the marketing of misbranded devices and failures to develop, maintain and implement written Medical Device Record procedures.[204]

2. Inspections of Medical Device Manufacturers

Although CDRH released statistics showing that it conducted slightly fewer inspections of medical device manufacturers in 2015 than 2014, FDA has put a clear emphasis on increasing inspections abroad.[205] In 2015, U.S. inspections fell 9%–marking the fourth consecutive year that the number of U.S. inspections decreased–but foreign inspections rose by about 5%, continuing an eight-year upward trend in the number of foreign inspections.[206] As in 2014, the majority of foreign inspections were carried out in China, Germany, and Japan.[207] CDRH stated that "the agency has been working toward increased foreign inspections as foreign manufacturer inventory has been growing rapidly," adding that "Production and Process Controls and Corrective and Preventive Actions continue to be the most frequently cited [Quality Systems] subsystems."[208] The number of warning letters issued for Quality Systems deficiencies remained exactly the same between 2014 and 2015 (121 letters) while the number of inspections dropped by about 5%.[209]

E. Legislative Developments

The U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions ("HELP Committee") addressed device issues a number of times in the first half of 2016. First, in response to the "superbug" outbreak that occurred between 2012 and 2015–during which 250 antibiotic-resistant infections were traced to closed-channel duodenoscopes–the Committee issued a report addressing FDA’s current postmarket surveillance system.[210] The report provided that "[f]ailures by device manufacturers and hospitals to quickly and completely disclose important information to FDA, and FDA’s outmoded adverse event system, hampered the agency’s ability to accurately assess and respond to the infections,"[211] and concluded that FDA’s reliance on self-reporting of adverse events is "unworkable and outdated."[212] The report recommended that Congress require unique device identifiers ("UDIs") to be included in insurance claims, electronic health records, and device registries as a supplement to self-reporting.[213] According to the Committee, this proposed requirement is an "absolutely essential piece of any fully functional, high-quality device surveillance system."[214] If Congress acts on the report’s recommendations, FDA’s recent guidance regarding postmarket surveillance (discussed above) may be rendered inadequate.

Second, the Committee advanced a variety of bills relating to devices. One such bill would expand FDA’s priority review of breakthrough medical devices to include all classes of devices, whereas currently only Class III devices are eligible.[215] The bill specifies the requirements for "breakthrough" designations and provides a number of steps that FDA must take to expedite review and approval.[216] A similar program is available for FDA approval of drugs designated as "breakthrough therapies."[217] The Committee also pushed forward a 2015 bill that would require FDA to train employees who review premarket submissions on "least burdensome" requirements and to issue revised guidance on in vitro diagnostic devices and waivers.[218]

Lastly, Senator Patty Murray (D-WA), the Committee member who released the superbug report discussed above, introduced a bill that would require FDA to identify types of medical devices for which premarket notification must include proposed labeling with validated cleaning, disinfection, and sterilization instructions.[219] The bill would also require FDA to issue guidance regarding when premarket notification is required for device modifications.[220]

V. Anti-Kickback Statute

The Anti-Kickback Statute ("AKS") prohibits drug and device manufacturers and other companies from "knowingly and willfully" offering, paying, soliciting, or receiving "remuneration" to induce or reward referrals or generate business involving any item or service reimbursable by federal health care programs.[221] Companies in violation of the AKS are subject to criminal liability, as well as potentially sizeable penalties under the civil monetary penalties law and the FCA.[222]

As whistleblowers and government enforcement agencies continue to pursue (with some success) ever-broader theories of remuneration and intent, drug and device manufacturers should evaluate any interaction with health care providers closely and strive to structure those relationships within applicable safe harbors when possible.

A. AKS-Related Case Law Developments

During the first half of 2016, the federal courts handed down several notable decisions interpreting the AKS.

In United States ex rel. Booker v. Pfizer, purported whistleblowers alleged that Pfizer violated the AKS and the FCA by implementing a "sham" speaker series that paid underqualified doctors to lecture on the company’s drug, Geodon, to induce additional prescriptions.[223] Broadly rejecting the plaintiffs’ theories, the District of Massachusetts court noted that the speaker series was "organized under written contracts that, on their face," met the requirements of an AKS safe harbor applicable to speaker arrangements, "used external consultants to establish fair market values for its speaker series," and provided "trainings to comply with anti-kickback requirements."[224] Although the court noted that "[f]ormal policies . . . are only as good as their implementation," the court concluded that, in light of the efforts to comply with the AKS, "the record simply cannot be found to show that Pfizer’s speaker series was a sham or pretext to conceal kickbacks."[225]

The court’s decision is also notable for its rejection of a broad theory of "inducement" under the AKS. The government and whistleblowers routinely take the position that remuneration is illegal if even one purpose is to induce additional business for the company.[226] In Booker, however, the court acknowledged that Pfizer’s speaker series was "not the best, most cost-efficient, or most fully educational speaker series that could be mounted," but rejected the notion that such shortcomings showed that the speaker series "had a ‘universal and improper purpose’ of inducing the speakers to prescribe Geodon."[227] The court explained that it is "unremarkable that Pfizer tracked its return on investment from the series; as a for-profit company, this is to be expected."[228] The court focused, however, on the fact that Pfizer’s tracking was limited to prescriptions written by attendees at the speaker series, not by the speakers themselves (who had received the remuneration).[229] In so holding, the court acknowledged the common-sense notion that businesses will act to increase their business and profits, and rejected the idea that any iota of inducement in the process triggers a violation of the AKS.

In United States et al., ex rel. Witkin v. Medtronic, Inc.,[230] a federal judge refused to dismiss kickback-related allegations in a larger FCA suit against Medtronic Inc. The complaint alleged that Medtronic assumed expenses related to various diabetes clinics it ran at physician offices and paid providers above-market rates to train patients in the use of its insulin pumps.[231] The court initially observed that a complaint must allege conduct "that plausibly would have violated the AKS or the Stark Act, including negation of safe harbors, in order to make a supported allegation that the claims induced by the alleged conduct were false under the FCA."[232] The court then addressed and accepted each of the relator’s theories of remuneration.[233] As to the diabetes clinics, the court clarified that the falsity of the claims for reimbursement "derived from referrals or recommendations by doctors who had in turn been influenced by kickbacks" from the defendant and emphasized that, even in cases of "properly-supervised" clinic services, physicians have received remuneration when they otherwise would have had to "expend additional money or time to administer the services [themselves] or pay staff to do so."[234]

Of note, the court appears to have conflated the remuneration and inducement elements in concluding that the "off-market value" of the training payments and "other freebies"–as demonstrated by a variance between Medtronic and Medicare rates paid to providers for training patients on Medtronic’s insulin pumps–was "sufficient at [the motion to dismiss] stage to support an inference of intent to induce referral or recommendation" of the company’s products.[235] Ultimately, the court also found that the AKS allegations in the complaint satisfied Rule 9(b)’s particularity standard.[236]

B. Enforcement Actions Against Individuals

As noted in our 2015 Year-End Update, the DOJ’s September 2015 Yates Memorandum, addressing the prosecution of individuals in corporate fraud cases, hinted at more aggressive enforcement with respect to individual liability.[237]

In a May 2016 speech to the New York City Bar Association White Collar Crime Conference, Deputy Attorney General Sally Quillian Yates reiterated that "holding individuals accountable for corporate wrongdoing has always been a priority" for the DOJ and is critical to "deter[ring] corporate misdeeds."[238] Ms. Yates emphasized that while companies are expected to "carry out a thorough investigation tailored to the scope of the wrongdoing," they are not required to "serve up someone to take the fall"–in other words, a "vice president in charge of going to jail."[239] As the DOJ’s emphasis on individual liability grows more pronounced, it remains to be seen what effects the Yates Memorandum will have on government AKS investigations and enforcement actions.

In the meantime, the DOJ’s headline AKS case against an individual recently ended in acquittal after a federal jury found former Warner Chilcott President, W. Carl Reichel, not guilty of conspiracy to violate the AKS.[240] In our 2015 Year-End Update, we discussed the DOJ’s allegations that Mr. Reichel schemed to induce doctors to write prescriptions for the company’s products through payments, meals, and other remuneration associated with sham speaking arrangements and "Medical Education Events." Mr. Reichel’s acquittal highlights the difficulty of proving criminal intent in court–especially when faced with defenses based on good faith like those presented to the jury.[241]

The DOJ will try again: in June, the DOJ charged a former district manager and a former sales representative of InSys Therapeutics Inc. with AKS violations based on allegations that they paid kickbacks to doctors participating in purportedly "sham" educational programs used to increase prescriptions of the company’s fentanyl spray.[242] In addition to criticizing the speaker fees themselves, the DOJ alleged that the speaker programs were "predominantly social gatherings at high-end restaurants" that involved no education or slide presentations and lacked appropriate audiences of HCPs.[243] The DOJ also questioned the educational purpose of repeated attendance at presentations that, by rule, used the same preapproved materials for each event.[244]

VI. Drug Development and Clinical Trials

After approving 45 new drugs in 2015[245]–the third highest number in history–FDA approved 15 new drugs during the first six months of 2016.[246] FDA’s guidance in the first six months of 2016 reflects concern over improving drug development and clinical safety, as well as providing guidance related to biosimilars. There also has been significant litigation related to the biosimilar approval process. These developments are discussed in further detail below.

A. Guidance on Improving Clinical Trials and Drug Approvals

In the first half of 2016, FDA issued several guidance documents aimed at improving safety during clinical trials and drug development. We briefly survey these developments below.

- Electronic Health Record Data in Clinical Investigations Guidance: With an eye toward "moderniz[ing] and streamlin[ing] clinical investigations," FDA released draft guidance in May 2016 regarding best practices for the use of electronic health record ("EHR") data in clinical investigations.[247] According to FDA, the draft guidance is "intended to assist sponsors, clinical investigators, contract research organizations, institutional review boards (IRBs), and other interested parties on the use of [EHR] data in FDA-regulated clinical investigations."[248] Notably, the draft guidance provides recommendations regarding: the use of interoperable EHR with electronic systems that support clinical investigations; the quality of EHR data; and measures to ensure that the EHR data meets FDA requirements.[249]

- Special Protocol Assessment Guidance: In May 2016, FDA issued guidance that provides detailed information on the CDER and CBER policies and procedures related to special protocol assessment ("SPA")–the process by which sponsors may confer with FDA regarding the "design and size of certain clinical trials, clinical studies, or animal trials . . . to determine if they adequately address scientific and regulatory requirements."[250] When finalized, the draft guidance will replace less detailed guidance from 2002.[251] Among other changes, the draft guidance includes explanations regarding (and additions to) the types of protocols that qualify for SPA, clarifications regarding the process to rescind an SPA, and details about the requirements for a SPA submission.[252]

- Safety Considerations for Product Design to Minimize Medication Errors: In addition to focusing on the safety and efficacy of drugs and biologics, FDA also considers the design of containers for those products. Indeed, in April 2016, FDA issued guidance outlining best practices and "a systems approach to minimize medication errors associated with product design and container closure design."[253] The guidance applies broadly to the development of drug and biologic products, and is intended for investigational new drug applications ("IND"s), new drug applications ("NDA"s), biologics licensing applications ("BLA"s), abbreviated new drug applications ("ANDA"s), and over-the-counter monograph drugs.[254] With this guidance, FDA hopes to encourage manufacturers to minimize or eliminate hazards contributing to medication errors at the product design stage.[255]

- Charging for Investigational Drugs Under an IND: In June 2016, FDA issued guidance providing "information for industry, researchers, physicians, institutional review boards ("IRB"s), and patients about the implementation of FDA’s regulation on charging for investigational drugs under an IND for the purpose of either clinical trials or expanded access for treatment use."[256] Among other topics, the question-and-answer guidance addresses charging for expanded access use and calculating recoverable costs.[257]

B. Developments in Biosimilar Approval Pathway Regime

The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act ("BPCIA"), enacted in 2010 as part of the Affordable Care Act, creates an "abbreviated licensure pathway for biological products that are demonstrated to be ‘biosimilar’ to or ‘interchangeable’ with an FDA-licensed biological product."[258] FDA approved its first biosimilar product, Zarxio, a biosimilar to Amgen’s reference drug Neupogen, in March 2015. Just over a year later, FDA approved a second biosimilar, Celltrion Inc.’s Inflectra, biosimilar to Janssen Biotech Inc.’s Remicade.[259]

As of July 13, 2016, FDA had not released data on the number of biosimilar applications it received during the first half of 2016.[260] The agency has yet to issue any guidance detailing requirements for establishing biosimilarity. FDA has, however, released the following new guidance documents related to biosimilars this year:

1. New Guidance Releases

- Labeling for Biosimilar Products: In March 2016, FDA released its eagerly awaited draft guidance on the labeling of biosimilar products.[261] Under the draft guidance, FDA indicated that it would require biosimilar labels to disclose conspicuously that the products are biosimilars.[262] The labels can, however, contain prescribing information derived in large part from the biosimilar’s reference product, and the labels do not need to state any clinical data information.[263] The draft guidance also provides information on how product labeling might require the use of different product names, depending on the section of labeling.[264] Further, the draft guidance explains what a sponsor must include in submissions to FDA regarding biosimilar product labeling.[265] The draft guidance does not alter FDA’s draft guidance from 2015, discussed in our 2015 Year-End Update, which required biosimilars to have a "core name" given to the reference product by the U.S. Adopted Names Council and a unique four letter suffix–a requirement that drew pointed criticism from the industry.

- Implementation of the "Deemed to be a License" Provision of the BPCIA: In March 2016, FDA issued draft guidance interpreting the "deemed to be a license" provision in section 7002(e)(4) of the BPCIA.[266] This provision states that certain products that FDA has historically regulated as "drugs" will be regulated as "biologics" starting on March 23, 2020.[267] The draft guidance discusses the impact of this transition on approved and pending drug applications and provides recommendations for sponsors of such applications. The guidance also explains the effects of the transition on the implementation of the exclusivity provisions of the BPCIA.

2. CMS Physician Fee Schedule Final Rule

In addition to the guidance from FDA, CMS released its 2016 Physician Fee Schedule Final Rule on October 30, 2015, which finalized the agency’s earlier proposal that payment amounts for biosimilar products will be based on the average sales price of all biosimilar products included within the same billing and payment code.[268] This approach has drawn sharp criticism this year from industry participants and legislators alike.[269] There is concern that this cost-cutting reimbursement policy disincentivizes biosimilar manufacturers by inappropriately treating biosimilars like generic drugs.[270] According to the manufacturers, inadequate reimbursement policies could result in fewer biosimilars being introduced in the United States.[271] CMS has left open the possibility of eventually revisiting this policy.[272]

3. Biosimilar Approval Litigation

As discussed in our 2015 Year-End Update, the first approved biosimilar drug (Zarxio) has been the subject of a pitched patent battle between Amgen and Sandoz. Amgen, the manufacturer of the reference product, Neupogen, alleged that Sandoz, the manufacturer of the biosimilar drug, Zarxio, was required under 42 U.S.C. § 262(l) to grant Amgen access to its confidential manufacturing plans and marketing application submitted to FDA no later than twenty days after FDA accepted Sandoz’s application for review (i.e., the "patent dance").[273]

But, in 2015, the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals disagreed with Amgen, holding that, despite the fact that the statute at issue used the word "shall," disclosure of the information at issue was optional rather than mandatory.[274] The court also concluded that the 180-day notice period of commercial marketing required under the BPCIA begins with the approval of the biosimilar.[275] Because Zarxio was approved on March 6, 2015, Sandoz could not begin marketing the drug until September 2, 2015.[276] After the court’s decision, Sandoz commercially launched Zarxio, at a 15% discount as compared to the reference drug, on September 3, 2015.[277] The Federal Circuit denied a petition for en banc review in October 2015.[278]

Amgen opted not to seek Supreme Court review of the Federal Circuit’s decision. But Sandoz petitioned for certiorari challenging the Federal Circuit’s ruling on the BPCIA’s 180-day notice provision of additional exclusivity with regard to commercial marketing.[279] In response, Amgen filed a conditional cross-petition, contending that if the Supreme Court chooses to hear the case (over Amgen’s argument that certiorari should be denied), the Court should also review the Federal Circuit’s other holding in this case, discussed above.[280] In the cross-petition, Amgen argued that the two issues are "inextricably intertwined," and also argued that the Federal Circuit’s holding that the word "shall" in 42 U.S.C. 262(l) is optional conflicts with controlling precedent holding that "shall" is mandatory.[281] The Supreme Court has yet to decide whether it will grant certiorari but did ask the Solicitor General to weigh-in on the issue.[282]

This case made clear that the 180-day notice requirement is mandatory for biosimilar makers that opt out of the "patent dance." It did not explicitly address whether notice is also mandatory for biosimilar makers that engage in this information exchange.

The Federal Circuit answered this question in early July, holding in Amgen Inc. v. Apotex Inc[283] that the 180-day notice requirement is mandatory for all biosimilar makers. Apotex argued that mandatory notice would effectively extend the 12-year exclusivity period enjoyed by reference product manufacturers by six months since the notice requirement is triggered by approval, which can occur only after the 12-year exclusivity period has lapsed.[284] The court rejected this argument, stating that it may be possible for the "FDA [to] issue a license before the 11.5-year mark and deem the license to take effect on the 12-year date."[285] Biosimilar manufacturers, however, have operated under the assumption that FDA does not issue licenses for biosimilars before the 12-year mark, thus making the court’s suggestion the potential focus of future litigation.[286]

C. Recent and Proposed Legislation

Like the second half of 2015, this year has seen little legislative activity associated with the clinical trial and drug approval processes. Nonetheless, there are a few updates to report.