January 12, 2017

This January more than most, it is tempting to focus on questions regarding what is to come. Aside from the uncertainties associated with a new administration, two key pieces of legislation seem to be heading in opposite directions. In the coming year, the 21st Century Cures Act will take effect, ushering in new rules to streamline drug approvals and move more products to the market faster. In the meantime, key provisions of the Affordable Care Act–if not the entire law–may be scrapped and, perhaps, replaced.

But there are many lessons to learn from the past year’s enforcement and regulation impacting pharmaceutical and medical device manufacturers. There is little question, for example, that the U.S. Department of Justice ("DOJ"), the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General ("HHS OIG"), and private whistleblowers will continue to pursue a significant number of enforcement actions against drug and device makers. On the margins, there may well be change in the administration’s enforcement priorities–however, because these investigations usually take years to complete, there likely will be "residual" settlements from ongoing investigations spearheaded by President Obama’s administration that will carry over into the next administration. And in any event, whistleblowers under the False Claims Act ("FCA") and, in the foreign corruption context, the Dodd-Frank Act, will likely fill any vacuum created by reduced government-led enforcement efforts. Indeed, relators and their counsel are becoming increasingly sophisticated and increasingly comfortable pursuing cases on their own, as evidenced by the substantial Atrium settlement in a non-intervened FCA case described in detail below.

On the regulatory front, the main take-away from this year is that regulatory change–including deregulation–comes slowly. Although there were some developments (primarily in the form of guidance), FDA largely continued the controversial practice of effectively regulating through enforcement actions (mainly Untitled and Warning Letters). While many agencies entered 2016 with grand plans to issue final guidance and implement regulatory changes, they ultimately took little formal action.

Below, we discuss the past six months’ most notable regulatory and enforcement developments affecting drug and device manufacturers. As in past updates, we begin with an overview of government enforcement efforts against drug and device companies under the FCA, the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act ("FDCA"), and other laws. We then address evolving regulatory guidance and action on topics of note to drug and device companies: promotional activities, manufacturing practices, and the Anti-Kickback Statute ("AKS"). We also detail certain developments of particular note to device manufacturers, before concluding with a summary of the 21st Century Cures Act provisions that will impact product development in a variety of areas.

I. DOJ Enforcement in the Pharmaceutical and Medical Device Industries

As Principal Deputy Assistant Attorney General Benjamin Mizer recently stated, the DOJ remains "fervently committed" to enforcement in the pharmaceutical and device industries and will "vigorously pursue fraud" on federal health programs.[1] In 2016, the DOJ’s commitment to this enforcement agenda led to plenty of notable headlines that served as important reminders for the industry that the DOJ’s investigative and enforcement activity is very unlikely to subside any time soon, even with the upcoming change in administration.

DOJ enforcement actions in the drug and device industries resulted in more than $1.4 billion in government recoveries during the 2016 calendar year. Three massive settlements of $200 million or more, including one for more than $700 million, buttressed the government’s haul. In pursuit of these recoveries, the DOJ employed its standard statutory arsenal (the FCA, the FDCA, and the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act ("FCPA")) to pursue drug and device defendants in both civil and criminal enforcement actions. This year, as usual, FCA and FCPA allegations drove the large-value civil settlements, but there were several notable developments related to FDCA criminal enforcement as well.

A. False Claims Act

The federal government recovered more than $4.7 billion in civil settlements and judgments under the FCA during the 2016 fiscal year, the third-highest amount on record.[2] There were also more than 800 new FCA cases filed in 2016, the second-highest number of FCA cases in any single year on record.[3] As in past years, drug and device companies contributed a large share of these historic totals: more than $1.4 billion of recoveries announced in 2016 came from these entities.

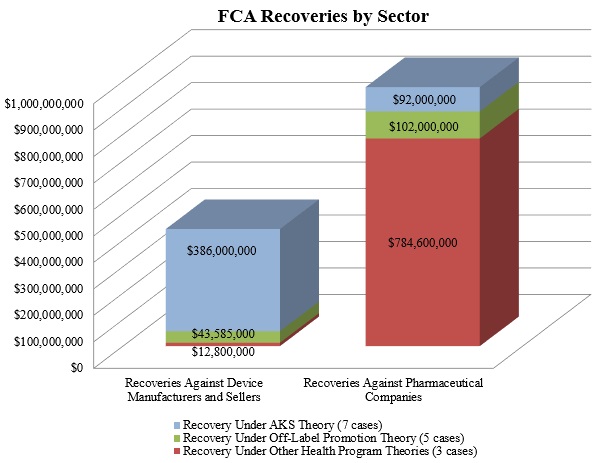

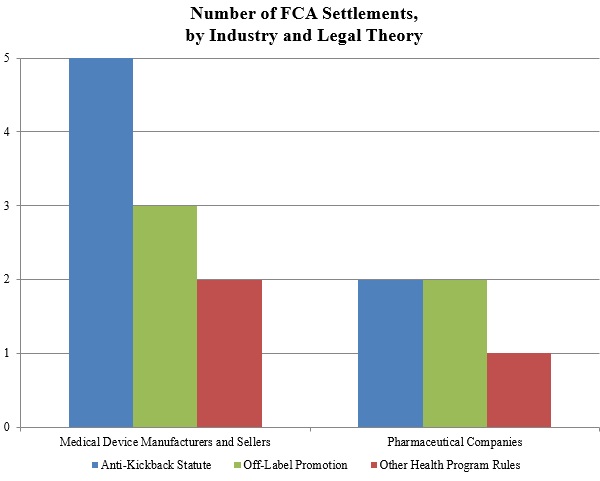

As shown below, the DOJ’s theories fell into the three well-traveled categories of recent years: illegal kickbacks under the AKS, off-label promotion, and various types of alleged fraudulent billing in violation of federal health program rules.

1. Settlements in FCA Matters Relating to Federal Health Program Rules

In 2016, FCA matters predicated on purported violations of Medicare or Medicaid requirements comprised the largest portion of the government’s recoveries from drug and device makers, accounting for nearly $800 million of the $1.4 billion. That sum resulted almost exclusively from the biggest FCA settlement of the year: drug manufacturers Wyeth and Pfizer Inc. agreed to pay $784.6 million to resolve federal and state claims alleging that Wyeth reported false prices for two acid reflux drugs.[4] As reported in our Mid-Year Update, Wyeth allegedly reported inaccurate prices to the government from 2001 to 2006, in violation of Medicaid regulations that require drug companies both to report the "Best Price" given to commercial customers and to pay rebates to state Medicaid programs calculated based in part on that Best Price. The Wyeth and Pfizer settlement is one of the ten largest FCA settlements of all time, in any industry.

Although dwarfed by the Wyeth and Pfizer settlement, the second half of 2016 also saw a notable settlement for allegedly improper billing by two durable medical equipment companies that supply products for diabetic patients, US Healthcare Supply and Oxford Diabetic Supply. On September 7, 2016, the companies, along with their owners and presidents (in their individual capacities), agreed to pay more than $12.2 million to resolve allegations that they used a fictitious entity to make unsolicited calls to Medicare beneficiaries to sell them medical equipment. The companies’ scheme allegedly violated the Medicare Anti-Solicitation Statute, which prohibits submitting claims to Medicare for equipment sold based on unsolicited cold-calls.[5]

2. Settlements in AKS-Related FCA Matters

In 2016, purported violations of the AKS remained the DOJ’s most frequently pursued category of misconduct. FCA claims based on alleged AKS violations accounted for the largest number of settled matters, netting the government nearly $500 million.

The largest AKS settlement of the year was the DOJ’s settlement with Olympus Corporation, which resulted in Olympus paying $646 million–$623.2 million to resolve AKS claims under the FCA and $22.8 million to resolve FCPA allegations. As reported in our Mid-Year Update, DOJ alleged that Olympus, the largest distributor of endoscopes in the United States, paid kickbacks to doctors and hospitals in the United States and Latin America. Not only was the Olympus settlement one of the ten largest FCA settlements of all time, it was also the largest AKS-based FCA settlement and the largest settlement by a medical device company in U.S. history.

Several other AKS settlements from the latter half of 2016 merit attention. These AKS settlements spanned a variety of financial relationships, illustrating the expansive theories pursued by both the DOJ and private whistleblowers:

- In late June 2016, Minneapolis-based Cardiovascular Systems, Inc. agreed to pay $8 million to resolve allegations that it provided illegal kickbacks to physicians through marketing and other practice development services to promote the use of its devices in atherectomies, a procedure that clears artery blockages.[6] Based on the allegations of a qui tam relator, the government contended that Cardiovascular Systems, Inc., inter alia, coordinated meetings between utilizing and referring physicians and created and implemented business expansion plans for physicians that used the company’s devices. The company also entered into a five-year Corporate Integrity Agreement that includes reviews by an independent organization.[7]

- In July 2016, Atrium Medical Corp. agreed to pay $11.5 million to settle allegations that it paid kickbacks to physicians through "give away" programs providing (among other benefits) free devices, preceptorships, speaker fees, referral dinners, and financial grants in exchange for promoting unapproved uses of the company’s medical stents in arteries.[8] The whistleblower, a former sales representative and territory business manager for the company, continued with the suit after the DOJ declined to intervene in 2014.

- In December 2016, Forest Laboratories and its subsidiary, Forest Pharmaceuticals, agreed to pay $38 million to resolve allegations that the companies paid kickbacks to induce physicians to prescribe their drugs between January 2008 and December 2011.[9] The DOJ alleged that Forest Laboratories and Forest Pharmaceuticals provided meals and payments to various physicians in connection with the companies’ drug-related speaker programs even when the programs were cancelled, when no licensed health care professionals attended the programs, or when the same physicians attended multiple programs over a short period of time.[10]

3. Resolution of Off-Label Promotion Investigations

As we have reported in recent years, several obstacles have arisen to the government’s off-label promotion theories as courts and juries have demonstrated their skepticism, especially in light of recognized First Amendment protections. Therefore, it is notable that in the second half of 2016, the government announced several recoveries in off-label cases, totaling nearly $150 million. On October 5, 2016, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp. agreed to pay $35 million to resolve allegations that it promoted its eczema cream Elidel for use on children, despite the fact that it was only FDA-approved for use in older patients.[11] And on November 7, 2016, medical device maker Biocompatibles Inc., a subsidiary of BTG plc, agreed to pay $25 million to resolve allegations that it violated the FCA by causing false claims to be submitted to government health care programs.[12] The company allegedly promoted its embolization device–designed to be inserted into blood vessels to block the flow of blood to tumors–for off-label use as a "drug-delivery" device, which was not an FDA-approved use and purportedly was not supported by substantial clinical evidence. The company also agreed to pay an additional $11 million in criminal fines and forfeitures.

4. The Supreme Court’s Escobar Decision

This past year was notable not only because of blockbuster settlements, but also because of critical developments in FCA jurisprudence. As we reported in our 2016 Mid-Year Update, the Supreme Court’s landmark Escobar decision in June reshaped the legal landscape in FCA cases. The Court affirmed the viability of the "implied false certification" theory of liability under certain circumstances (and recast it in common-law terms) and sharpened the FCA’s "demanding" materiality standard. For complete coverage of post-Escobar developments, please refer to our 2016 Year-End FCA Update.

Many theories of liability that the government and relators have pursued against drug and device companies have hinged on implied false certification theories. Thus, Escobar is particularly important to drug and device companies because it opened the door to arguments that may provide additional support for cabining nebulous implied false certification theories.

Since the Supreme Court decided Escobar in June 2016, FCA defendants have started to press some of those arguments. Two hotly litigated issues regarding Escobar‘s meaning have come to the forefront: (1) the requirements a plaintiff must meet to advance a viable "implied false certification" theory and (2) the proper application of Escobar‘s clarification of the FCA’s materiality standard.

a. Defining the Boundaries of an "Implied False Certification" Claim

The Supreme Court stated in Escobar that an "the implied certification theory can be a basis for [FCA] liability, at least where two conditions" are met: (1) "the claim does not merely request payment, but also makes specific representations about the goods or services provided," and (2) "the defendant’s failure to disclose noncompliance with material statutory, regulatory, or contractual requirements makes those representations misleading half-truths."[13] In reaching that conclusion, the Court explained that the phrase "false or fraudulent" under the FCA should be interpreted in accordance with the meaning of those terms at common law.[14]

Since Escobar, the lower courts have reached different conclusions as to the precise requirements for showing liability based on an implied certification. A number of courts have taken Escobar at face value, requiring the FCA plaintiff to show both of Escobar‘s conditions, including that the defendant made "specific" misleading representations about the goods or services provided, to be liable based on an implied certification theory.[15] One of these courts observed that imposing liability in the absence of a sufficiently "specific" misrepresentation about the goods or services provided "would result in an ‘extraordinarily expansive view of liability’ under the FCA, a view that the Supreme Court rejected in Escobar."[16]

But some courts have asserted that they are not bound by Escobar‘s "specific representation" requirement. For example, in Rose v. Stephens Institute, the Northern District of California rejected the argument "that Escobar establishes a rigid" test for falsity "that applies to every single implied false certification claim."[17] Reasoning that the Supreme Court left the door open by limiting its holding to "at least" the circumstances before it in Escobar and by expressly declining to "resolve whether all claims for payment implicitly represent that the billing party is legally entitled to payment," the court held that a relator can state an implied false certification claim without necessarily identifying a "specific" representation that was a "misleading half-truth" in any claim.[18]

In United States ex rel. Brown v. Celgene Corp., one of the first cases against a pharmaceutical or device company to test this theory, the Central District of California followed Rose and held that a relator’s implied false certification allegations against the pharmaceutical company Celgene Corp.–based on off-label promotion and alleged kickbacks–could survive despite the fact that the relator failed to identify any "specific misrepresentation" made in a claim for payment.[19]

Federal appellate courts have not yet had the opportunity to fully develop their take on the scope of Escobar‘s "two conditions," including whether a "specific representation" is required. The Seventh Circuit has recently signaled that it will enforce a strict reading of Escobar‘s requirements. In United States v. Sanford-Brown Ltd., for example, the Seventh Circuit affirmed summary judgment in favor of a defendant where the relator offered no evidence that the defendant had made "any representations at all," explaining that "bare speculation that [a defendant] made misleading representations is insufficient."[20] Other federal appellate courts are likely to begin to address the "two conditions" this year. Indeed, the Rose court subsequently certified its decision embracing a less restrictive reading for interlocutory appeal to the Ninth Circuit.[21] And in United States ex rel. Panarello v. Kaplan Early Learning Co., a magistrate judge in the Western District of New York similarly declined to require an FCA plaintiff to show "specific representations," but recommended that the question be certified for interlocutory appeal to the Second Circuit.[22] As appellate courts take their turns at addressing this issue, we will watch carefully for any emerging circuit split that could send this issue back to the Supreme Court sooner rather than later.

b. Application of Escobar‘s "Demanding" Materiality Standard

In Escobar, the Supreme Court not only specified the requirements for the implied false certification theory, but also reframed the FCA’s materiality standard as a question of whether a violation of the specific statute, regulation, or requirement at issue would actually have affected the government’s decision to pay for a claim had the government known of the alleged noncompliance.[23] In so doing, the Court made clear that materiality does not exist merely because the government may have the option not to pay a claim due to the alleged wrongdoing. The Court also explained that whether the particular statutory, regulatory, or contractual requirement at issue is specifically labeled a condition of payment remains relevant to materiality, but it is not dispositive.[24] The Court also stated that the FCA’s materiality requirement, which is an important bulwark against plaintiffs looking to bootstrap garden-variety regulatory violations or breach of contract claims into FCA liability, is "demanding" and "rigorous"–and that courts must ensure FCA plaintiffs satisfy this "rigorous" requirement by pleading facts showing materiality "with plausibility and particularity under Federal Rules of Civil Procedure 8 and 9(b)."[25]

Since Escobar, several courts have seized on the Court’s command to rigorously review a complaints’ materiality allegations at the motion to dismiss stage–and have demanded that complaints include plausible, more-than-conclusory allegations showing that (1) the government either actually does not pay claims involving violations of the statute, rule, or regulation at issue, or (2) the government was unaware of the violation but "would not have paid" the claims at issue "had it known of" the alleged violations.[26]

In Sanford-Brown, one of the first appellate court decisions on the issue, the Seventh Circuit held that a relator must provide "evidence that the government’s decision to pay" a claim "would likely or actually have been different had it known of [the defendant’s] alleged noncompliance" with the statute, rule, or regulation at issue.[27] The court affirmed summary judgment for the defendant, concluding the alleged noncompliance was not material to the government’s decision to pay claims because the government had "already examined" the alleged misconduct "multiple times over and concluded that neither administrative penalties nor termination was warranted."[28] Similarly, in United States ex rel. D’Agostino v. ev3, Inc., which is discussed in further detail below, the First Circuit concluded that allegations a defendant’s purported misconduct–i.e., misstatements to FDA during the drug approval process–"could have" influenced "the government’s payment decision" failed to satisfy the "demanding" materiality standard set by Escobar.[29] In holding the relator had not adequately alleged materiality, the First Circuit also relied on the fact that the government neither "denied reimbursement" for the claims at issue nor took any other regulatory actions despite having been made aware of the allegations of the defendant’s fraudulent conduct six years earlier.[30]

In line with Escobar‘s statement that identifying a provision as a condition of payment is "not automatically dispositive" of materiality, some courts have also dismissed complaints that merely allege payment "was conditioned on the claim being compliant" with the allegedly violated laws.[31] Similarly, nakedly alleging that the government "has a practice of not paying claims" involving the alleged violations is not enough to survive the rigorous pleading requirements reiterated in Escobar–especially when the government has actually paid claims after learning of the alleged violations.[32]

Of particular note for drug and device companies, however, in Brown, the court explored how Escobar‘s materiality standard might be applied to pharmaceutical companies accused of off-label promotion. The court suggested that even under Escobar‘s demanding materiality requirement, allegations of off-label promotion may be "material" for purposes of government payment because, inter alia, "Medicare Part D may only reimburse ‘covered part D drugs’ . . . ‘used for a medically accepted indication.’"[33] In the court’s view, this at the very least created a genuine issue of disputed fact that foreclosed summary judgment for the defendants.

c. The First Circuit Cabins FCA Liability Based on Alleged Fraud on FDA

The First Circuit’s decision in D’Agostino, discussed above, is also notable because it forecloses alleged fraud perpetrated on FDA as a basis for FCA liability, with the potential exception of situations where FDA has actually withdrawn approval or clearance of a medical device based on such fraud.[34] The relator in D’Agostino alleged the defendants made fraudulent misstatements to FDA in seeking approval of defendants’ medical devices. According to the relator, defendants allegedly disclaimed uses for the devices they later advocated in promotional activity, overstated the training that they would provide for the device, and omitted critical safety information from the information provided to FDA.[35] The relator alleged that FDA would not have approved the device had it known of the fraudulent statements, and thus these fraudulent statements ultimately led the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services ("CMS") to pay claims for use of that device (which CMS would not have done but for FDA’s pre-market approval).[36]

The First Circuit rejected the relator’s fraud theory and affirmed the District Court’s dismissal of the relator’s complaint. First, the court reasoned that the relator did not allege that the purported misrepresentations "actually cause[d] the FDA to grant approval it otherwise would not have granted"; therefore, the relator did not plead the required causation between the alleged false statements and disbursement of government funds for the device.[37] The court observed that FDA did not withdraw its approval of the device and did not take any other action (such as imposing post-approval requirements or suspending approval), despite having been aware of the alleged fraudulent statements for six years.[38] By focusing on FDA’s knowledge of the fraudulent statements and its decision not to withdraw its approval, the court arguably required that, going forward, plaintiffs plead either that FDA would have withdrawn its approval if it had knowledge of the fraudulent statements, or that FDA did not have such knowledge. Second, the Court invoked important policy justifications for its holding, recognizing that "[t]o rule otherwise would be to turn the FCA into a tool with which a jury of six people could retroactively eliminate the value of FDA approval and effectively require that a product largely be withdrawn from the market even when FDA itself sees no reason to do so."[39] In addition to unjustifiably allowing private parties (or juries) to override FDA rulings, the relator’s theory would have prompted several practical problems, such as deterring new device approval applications, and requiring courts to attempt to determine whether or not "FDA would not have granted approval but for the fraudulent representations" made by the applicant.[40] Third, the court also rejected the relator’s argument that subsequent modifications and improvements to a device show that earlier versions were defective, explaining by analogy that if that were enough to show falsity then "most every car sold to the government would be per se defective."[41]

Although the First Circuit’s decision reins in future use of the fraud-on-FDA theory in the FCA context, the decision leaves open the possibility that such a theory could potentially support a viable FCA claim where FDA had, in fact, made the decision to withdraw its approval of a device after discovering fraud perpetrated during the pre-market approval process. The court, however, expressly declined to resolve whether a relator would be able to state a viable FCA theory under those circumstances.[42]

B. FDCA Enforcement Actions and Developments

The second half of 2016 saw one particularly notable enforcement action under the FDCA. As noted above, in November 2016, Biocompatibles Inc. agreed to resolve the DOJ’s criminal (FDCA) and civil (FCA) allegations. Under the terms of its plea agreement, the company agreed to pay an $8.75 million criminal fine for misbranding its device and a criminal forfeiture of $2.25 million. The settlement is noteworthy for two primary reasons. First, the government asserted that Biocompatibles provided FDA assurances that its embolic device, "LC Bead," would not be used as a drug-eluting device while approval for the device’s use for that purpose was still pending. According to the government, just two years later–while the approval process was still underway–the company began promoting the device for drug delivery. It appears that the government sought to punish the company for "circumvent[ing]" the FDA approval process (as Principal Deputy Assistant Attorney General Mizer put it)–a theory in the same vein as the fraud-on-the-FDA theory occasionally advanced by FCA plaintiffs.[43] Second, the government alleged Biocompatibles contracted with a distribution sales force, and that those sales representatives marketed the device off-label. This is a valuable reminder that manufacturers may, in certain circumstances, be held liable for the conduct of their third-party business partners, including contract sales organizations or distributors.

Several decisions from appellate courts in 2016 explored key facets of criminal liability under the FDCA.

In United States v. DeCoster, a panel of the Eighth Circuit, over a dissenting opinion, upheld the misdemeanor convictions of two owners and operators of an egg-production company for introducing eggs into interstate commerce that had been adulterated with salmonella enteritidis.[44] Even though the defendants lacked any mens rea, the court held that corporate officers could be criminally liable under the FDCA for their failure to prevent or remedy conditions that gave rise to the FDCA violations, and that "[t]he elimination of a mens rea requirement does not violate the Due Process Clause for a public welfare offense where the penalty is ‘relatively small,’" (here, three months in prison).[45] The court explained that the defendants did not claim they were "powerless" to prevent the adulterated eggs from being introduced into commerce, and emphasized that they knew or should have known of the risks–even if they did not know of any actual problem–posed by unsanitary conditions at their egg barns.[46] In so holding, the Eighth Circuit refused to undercut the so-called Park doctrine, which–based on the Supreme Court’s 1975 decision in United States v. Park–imposes potential criminal liability on responsible corporate officers even absent any mens rea.[47]

In United States v. Kaplan, the Ninth Circuit held, in a matter of first impression, that the FDCA’s anti-adulteration provision, 21 U.S.C. § 331(k), could support a criminal conviction for a physician’s reuse of consumable, single-use devices in connection with biopsies performed on patients.[48] That provision prohibits holding "for sale" any adulterated device. According to the government, the physician decided to reuse needle "guides" during biopsies to save on cost. Even though the device was never transferred to the patient, the court held it was effectively "sold" to the patient as part of the payment for the procedure.[49]

C. FCPA Investigations

In addition to the many FCA resolutions, the DOJ and the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission ("SEC"), which is responsible for civil enforcement of the FCPA against issuers, also resolved several high-profile FCPA enforcement actions involving drug or device companies during the last six months of 2016.

On December 22, 2016, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., the world’s largest manufacturer of generic pharmaceutical products, agreed to pay more than $519 million–the fourth-largest FCPA resolution ever (and the largest ever involving a pharmaceutical company)–to resolve FCPA allegations leveled by the DOJ and the SEC. The settlement arose from alleged corrupt payments made between 2002 and 2012 to high-ranking ministry-of-health officials in Russia and Ukraine to influence the approval of drug registrations and to state-employed physicians in Mexico to influence prescribing decisions.[50] On the civil side, Teva agreed to pay more than $236 million in disgorged profits and prejudgment interest to the SEC to resolve alleged violations of the FCPA’s anti-bribery, books-and-records, and internal-controls provisions. To resolve criminal charges, Teva entered into a deferred prosecution agreement charging FCPA anti-bribery and internal-controls violations, and its Russian subsidiary pleaded guilty to a one-count criminal information charging conspiracy to violate the FCPA’s anti-bribery provision, with a combined criminal penalty of $283.18 million. Teva also will retain a corporate-compliance monitor for a three-year term. The settlement is a wake-up call for those in the generic-drug market–even absent robust promotional sales and marketing activity, generic-drug makers frequently interact with government officials worldwide.

On August 30, 2016, AstraZeneca PLC, the U.K.-based biopharmaceutical company, agreed to resolve FCPA charges with the SEC arising from alleged misconduct in China and Russia between 2005 and 2010.[51] According to the charging document, employees of AstraZeneca’s Chinese subsidiary provided cash, gifts, speakers’ fees, and other items of value to public health care providers in China as incentives to prescribe or purchase the company’s products. The SEC also alleged that AstraZeneca paid public officials to reduce or dismiss financial penalties proposed against the company’s subsidiary. Further, employees of AstraZeneca’s Russian subsidiary also purportedly made improper payments to incentivize public-sector pharmaceutical sales in Russia. Without admitting or denying the allegations, AstraZeneca consented to the entry of an administrative order finding violations of the FCPA’s books-and-records and internal-controls provisions and paid $5,147,000 in disgorgement and prejudgment interest, as well as a $375,000 civil penalty. AstraZeneca announced that the DOJ closed its investigation of the company without filing charges.

II. Promotional Issues

Compared to recent years, 2016 saw relatively few developments in First Amendment jurisprudence regarding FDA’s authority to regulate off-label promotional speech. The past year also featured minimal progress in FDA’s long-awaited overhaul of its regulatory policies regarding truthful and non-misleading promotional speech. It remains to be seen whether the new administration changes the hand at the helm of FDA immediately. Regardless, it is likely that the slow march toward greater freedom from regulation of truthful promotional information will continue (and perhaps even move along more briskly).

Below, we address several developments in this area, including updates on FDA’s regulatory overhaul and enforcement and guidance activity, as well as on pending legal challenges and legislative changes.

A. FDA Enforcement Activity – Advertising and Promotion

FDA letters relating to advertising and promotional issues in 2016 rose slightly as compared to the previous two years. FDA’s Office of Prescription Drug Promotion ("OPDP") issued eleven total letters this year–eight Untitled Letters and three Warning Letters–which combined are two more than its total in 2015.[52] The latter half of the year saw a flurry of activity, with OPDP issuing nine letters within just the last four months, and six in December alone. As in recent years, FDA continued to target its enforcement towards various forms of electronic advertising, with two OPDP letters pertaining to traditional websites,[53] two pertaining to YouTube videos,[54] and one regarding e-mail communication.[55]

As we reported in our 2015 Year-End Update, Congress has criticized FDA’s practice of enforcement by Untitled Letter. But OPDP’s eight Untitled Letters this year–representing two-thirds of its entire enforcement activity for the year–suggest the agency does not intend to slow its use of Untitled Letters despite past criticism from Congress on the practice. In 2017 and beyond, under a new administration that is politically aligned with Congress, FDA’s use of enforcement by Untitled Letter could certainly change.

The vast majority of OPDP’s letters this year concerned the omission and/or minimization of risk information. Two OPDP letters, however, were notable in that FDA had no objections to the substance of the risk information, but instead took issue with the presentation of that information.

- December 12, 2016, Untitled Letters to Celgene and Sanofi-Aventis regarding Television Advertisements:[56] In a pair of December Untitled Letters, OPDP objected to two companies’ presentations of risk information in television advertisements. Specifically, FDA took issue with the use of fast-moving visuals, frequent scene changes, and background musical interjections that the agency concluded were overly distracting. As a result of these attention-grabbing elements, FDA determined it was too difficult for consumers to adequately process the risk information presented simultaneously in the advertisements. These letters serve as an important reminder that the method of communication of risk information can be just as important, from a compliance perspective, as the content of that information.

For those drug and device makers that promote their products using social media and Internet-based advertisements, two OPDP letters were particularly noteworthy:

- December 21, 2016 Untitled Letters to Zydus Discovery DMCC and Chiasma Inc. regarding YouTube Advertisements:[57] In another pair of December Untitled Letters, OPDP took issue with two companies’ use of videos posted both on YouTube.com and on other websites (including websites controlled by each company). The videos advertised each company’s product as safe and effective, even though neither had received FDA approval. OPDP chastised Zydus for misleadingly suggesting its product was recognized as safe and effective "worldwide" including in the United States, when, in fact, the drug had only been approved for use in other countries. In the case of Chiasma, the agency asserted that the video misleadingly made safety and efficacy claims throughout a video that was more than three minutes long. FDA concluded that a brief (eight-second) disclaimer at the end of the video did not effectively mitigate the claims, warning that "no disclaimer" would "sufficiently mitigate the extensive claims" permeating the video.

B. FDA’s Promotional Guidance

We are still waiting for the new guidance regarding off-label promotion for drugs and devices that FDA pledged to issue more than two years ago. In November 2016, however, FDA held a public, two-day meeting to accept commentary and feedback as the next step in the process.[58] In what could be a positive sign for the industry, FDA recognized the benefits of communicating "relevant, truthful and non-misleading scientific or medical information regarding unapproved uses of approved medical products," which it conceded "may help health care professionals make better individual patient decisions."[59] Yet even as FDA acknowledged the value of information regarding unapproved uses, it was quick to caution that diminished regulation could lead to communications not based on sound science and to fewer scientific studies of new and investigational uses.[60]

FDA has solicited further commentary on its regulation of "communications about unapproved uses" until early 2017 from a wide range of stakeholders, including health care professionals, industry groups, health care organizations, "payors and insurers, academic institutions, public[-]interest groups, and the general public."[61] Accordingly, questions regarding industry guidance or policy changes that will result from FDA’s efforts will likely remain unanswered until at least well into 2017.

This past year, as FDA continued to grapple with the evolving legal landscape in the area of drug and device promotion, the pace of its advertising and promotional-guidance activity slowed compared to years past. As we reported in our Mid-Year Update, FDA’s Guidance Agenda for 2016 indicated the agency’s intent to publish four draft guidance documents in 2016 regarding advertising:

(1) Health Care Economic Information in Promotional Labeling and Advertising for Prescription Drugs Under Section 114 of the Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act;

(2) Internet/Social Media Advertising and Promotional Labeling of Prescription Drugs and Medical Devices – Use of Links to Third-Party Sites;

(3) Manufacturer Communications Regarding Unapproved, Unlicensed, or Uncleared Uses of Approved, Licensed, or Cleared Human Drugs, Biologics, Animal Drugs and Medical Devices; and

(4) Presenting Risk Information in Prescription Drugs and Medical Devices Promotion (Revised Draft).

FDA never issued any of these draft guidance documents in 2016.[62] FDA’s 2017 Guidance Agenda entirely removes these four topics, and promises instead just one draft guidance document relating to advertising: Drug and Device Manufacturer Communications with Payors, Formulary Committees and Similar Entities.[63] Whether this broad topic covers all of the promotional advertising issues FDA signaled in 2016 will be an interesting issue in 2017. We will continue to track FDA’s work in this area, and report back when–or rather, if–FDA issues the promised guidance this time around.

While FDA stood on the sidelines in 2016, industry groups took their own initiative by issuing principles intended to guide off-label communications with health care providers, entitled "Principles on Responsible Sharing of Truthful and Non-Misleading Information about Medicines with Health Care Professionals and Payers."[64] Intended to serve as "responsible, science-based parameters for accurate and trusted information sharing" regarding unapproved uses with health care providers, the Principles center around three key concepts: (1) use of "science-based" communications, (2) provision of "appropriate contextual information" to ensure the recipient better understands issues of safety, effectiveness, and value of the medicines, and (3) tailoring communications to the intended audience in light of the recipient’s existing knowledge base.[65] It will be interesting to see whether FDA takes heed of these concepts as part of its own regulatory overhaul and whether, under the new administration, self-regulatory activity of this sort provides a basis for further inaction, if not deregulation.

C. Off-Label Promotion and the First Amendment

Although the second half of 2016 turned up little activity in the courts relating to promotional issues, one criminal prosecution under the FDCA stood out as what may prove to be the next significant test of the First Amendment precedent set by United States v. Caronia[66] and Amarin Pharma, Inc.[67] In United States v. Facteau,[68] a jury convicted a pair of former executives of a medical device manufacturer on ten misdemeanor counts for promotion of a device for off-label use as a steroid delivery system, although the jury acquitted the defendants on all felony counts under the FDCA. Notably, the court allowed the jury to consider true statements that the company made relating to the off-label use of the device as evidence of guilt (i.e., evidence that the "intended use" of the device was not approved and thus that the executive unlawfully marketed a misbranded and adulterated device).[69]

In the aftermath of the trial, the defendants moved the court to enter a judgment of acquittal, invoking Caronia and Amarin and arguing that the government’s reliance on truthful, non-misleading speech to prosecute the defendants violates the First Amendment.[70] The court has yet to rule on the defendants’ motion, but the court’s resolution of this First Amendment challenge could set the stage for the next legal showdown in this arena.

D. Legislative Developments

On December 13, 2016, the President signed into law the 21st Century Cures Act, after Congress passed the bill several days earlier with broad bipartisan support.[71] As we reported in our Mid-Year Update, Congress had been considering a version of the bill containing a provision that would have required FDA to draft guidance on "facilitating the responsible dissemination of truthful and nonmisleading scientific and medical information not included in the approved labeling of drugs and devices."[72] However, the version of the bill ultimately enacted into law dropped this requirement.

But even in what some would call a watered-down form, the Act took some steps to facilitate greater freedom for companies in communications regarding off-label uses. First, the Act provides greater latitude for use of off-label information in the drug and device approval process by amending the FDCA to mandate that FDA draft guidance on how "real-world evidence" (i.e., information on off-label usage) can be used to support approval of new indications for products already approved by FDA.[73] Second, the Act amends the FDCA to broaden the scope of information drug manufacturers can disseminate about off-label uses of their products to include greater information regarding the "economic consequences . . . of the use of a drug" even where the information is "related," but not necessarily "directly related," to an FDA-approved indication.[74] This same amendment to the FDCA broadens the scope of entities who can receive such economic information to include payors.[75] In sum, while modest compared to the legislation that the drug industry desired, these changes represent a step in the right direction towards allowing more room for dissemination of information relating to off-label uses.

In closing, it is worth noting that, as we observed in our Mid-Year Update, members of Congress have continued to criticize FDA’s policies regarding off-label promotion, which a politically unified 115th Congress may be poised to address by further legislative action. Indeed, in the face of FDA’s slow progress in issuing revised guidance regarding off-label promotion, a legislative solution may be on the horizon as early as this calendar year.

III. Developments in cGMP Regulations and Other Manufacturing Issues

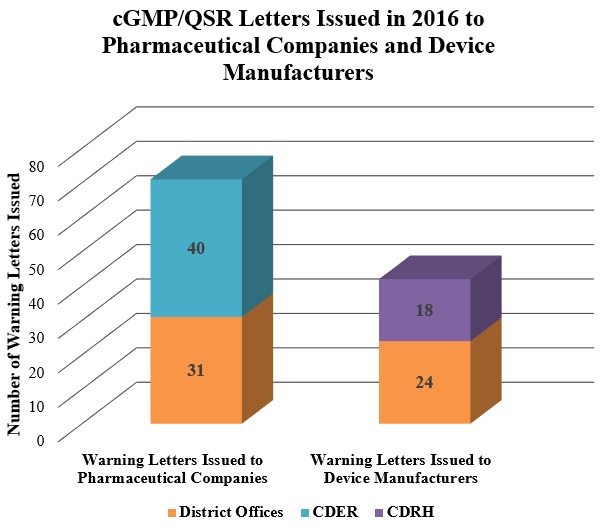

FDA continued to scrutinize closely companies’ current good manufacturing practice ("cGMP") and quality systems regulation ("QSR") compliance in 2016, with significant activity in both areas. We address these enforcement actions and other key developments in cGMP and QSR regulation from 2016 below.

A. 2016 cGMP and QSR Compliance and Enforcement Trends

1. cGMP- and QSR-Based Warning Letters: Overview

2. FDA Continues Crackdown on Data Integrity Compliance Issues

In the latter half of 2016, FDA continued to focus on the types of data integrity compliance issues we previously reported for the first half of the year. FDA issued Warning Letters regarding data-integrity practices that violated cGMPs to companies in China, the Czech Republic, India, Israel, and Japan (among other countries).[76] These letters highlight FDA’s increasing foreign-inspection activity (as discussed in our Mid-Year Update).

In its Warning Letters, FDA noted several data-integrity issues, including: (1) failures to maintain completed data derived from all laboratory tests conducted; (2) failures to prevent unauthorized access or changes to data; and (3) failures to record activities at the time they are performed.

Among other admonishments, FDA took particular issue with failures to maintain complete data (and, in certain circumstances, for manipulating or deleting data). For example, in August 2016, FDA issued a warning to Zhejiang Hisoar Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., for "retest[ing] samples until . . . [obtaining] desirable results" and failing to "investigate, review, or report original results."[77] Also in August, FDA issued a warning letter to Zhejiang Medicine Co. Ltd. for failing to "consider the results of [its] unofficial analyses to evaluate the quality of [its active pharmaceutical ingredients] or make batch release decisions."[78] FDA also issued warning letters to other manufacturers regarding blatant attempts to delete or manipulate data–efforts FDA views as evidence of a failure to enact adequate data integrity controls in compliance with cGMPs.[79]

FDA ultimately required that all companies warned of data integrity violations comply with a three-part program, requiring: (1) a comprehensive investigation into inaccuracies in data records and reporting; (2) a risk assessment of the effect of observed failures on drug quality; and (3) a management strategy detailing global corrective action and a preventive action plan.[80]

3. FDA Warns Foreign Manufacturers Regarding Cleaning Protocols

FDA continued to call out foreign manufacturers for failing to maintain sanitary manufacturing facilities and to prevent cross-contamination of drugs. For example, FDA’s discovery of "[d]irt and birds in the manufacturing area," and "a lizard" in a controlled processing area of Unimark Remedies Limited’s Indian facilities drew a Warning Letter from FDA.[81] Xiamen Origin Biotech Co. Ltd. also received a Warning Letter for "dirty warehousing spaces" and a "rodent" observed in a room adjacent to the warehouse.[82] Cheng Fong Chemical Co. officials went so far as to admit "the rooms had never been cleaned," when FDA inspectors found "filth, insects, wet layers of . . . unidentified material on the floors, and foul odors"[83]–a finding that unsurprisingly resulted in a Warning Letter.[84]

In June 2016, SmithKline Beecham Limited received a Warning Letter regarding the risk of cross-contamination in its dedicated penicillin manufacturing area in its U.K. facility.[85] FDA warned SmithKline to "commit" its facility to penicillin manufacturing only or else fully decontaminate the facility, noting its preference for the former: "It is profoundly difficult to completely decontaminate a facility of [penicillin] residues."[86]

4. FDA Admonishes Manufacturers for Obstructing FDA Inspections

In 2016, several firms received Warning Letters for attempting to avoid FDA inspections altogether, prompting FDA to proclaim that it will not tolerate stonewalling. Citing the FDA Safety and Innovation Act of 2012, which makes obstruction of an inspection grounds for deeming a drug adulterated, FDA has issued Warning Letters and barred pharmaceutical imports in response to purported efforts to duck inspections.[87]

In September 2016, FDA asserted that Nippon Fine Chemical took several steps to bar FDA inspection of its Japanese plant. First (according to FDA), the quality-control manager "directed employees to stand shoulder-to-shoulder," blocking an FDA investigator’s access to the "laboratory and the equipment used to analyze drugs for U.S. distribution."[88] The firm then purportedly refused to provide FDA with copies of complaint records, including records indicating that its drugs contained "glass, hair, cardboard, metal, product discoloration, and a black spider."[89] Finally, a firm manager allegedly "impeded the inspection by preventing [the FDA] investigator from photographing" manufacturing equipment.[90] In response, FDA issued a Warning Letter and an import alert against the company’s products.

Beijing Taiyang Pharmaceutical Industry Co. similarly barred FDA investigators from entering a warehouse, in which the investigators observed "drums bearing [the] company’s label."[91] When investigators returned and were allowed access the following day, they noticed that a significant number of drums observed the day before had been removed without explanation.[92] In response, FDA issued a Warning Letter and an import alert, making clear how the agency will deal with such companies that attempt to obstruct FDA inspections.

5. FDA Takes Issue with Device Manufacturers’ Complaint Handling

In 2016, FDA issued dozens of Warning Letters to device manufacturers for inadequate complaint handling, making it clear that companies must properly manage complaints.

For example, in May 2016, a company that "manufactures laser[-]powered surgical instruments" received a Warning Letter regarding its handling of complaints from patients burned by its device.[93] Of the eight complaints sampled by FDA investigators, none included medical device report ("MDR") evaluations.[94] One month later, FDA issued a Warning Letter to a U.S.-based device manufacturer for failing to investigate any of the 136 complaints reviewed by FDA investigators.[95]

FDA has also been on the lookout for manufacturers that fail to report serious adverse events.[96] To avoid similar enforcement actions, device manufacturers should ensure that complaint systems are compliant with QSRs.

B. cGMP Rulemaking and Guidance Activity

In November 2016, FDA issued several guidance documents pertaining to manufacturing and quality issues. Notably, FDA released its final guidance outlining recommendations regarding quality agreements between drug manufacturers and contracted facilities and its draft guidance regarding submission of quality metrics data by drug manufacturers. FDA also provided updated guidance on medical device reporting.

1. Quality Agreements

On November 23, 2016, FDA released its final FDA guidance regarding quality agreements between product "owners" and "contracted facilities."[104] Although such agreements are not required by law, the FDCA prohibits any person from introducing an adulterated drug into interstate commerce.[105] The FDCA further provides that drugs not manufactured in compliance with cGMPs–which require "the implementation of oversight and controls over the manufacture of drugs"–will be deemed adulterated.[106] Accordingly, FDA’s recent guidance "recommends that owners and contract facilities establish a written quality agreement to describe their respective CGMP-related roles, responsibilities, and activities in drug manufacturing."[107]

2. Quality Metrics

On November 25, 2016, FDA released a revised version of its draft guidance titled "Submission of Quality Metrics Data."[108] As the draft guidance observes, various quality metrics are used by the pharmaceutical industry to monitor quality control processes and "drive continuous improvement in drug manufacturing."[109] FDA intends to use these metrics to develop compliance and inspection policies, improve FDA’s ability to predict future drug shortages, and encourage the industry to develop quality management systems for pharmaceutical manufacturing. Accordingly, FDA is initiating a quality metrics program that will begin with a voluntary reporting phase during which FDA will accept data submissions from drug manufacturers.[110] FDA will then "initiate notice and comment rulemaking under existing statutory authority to develop a mandatory quality metrics reporting program."[111]

3. Medical Device Reporting

On November 9, 2016, FDA finalized its guidance on "Medical Device Reporting for Manufacturers."[112] Significantly, this guidance reintroduces a two-year presumption that once a malfunction has caused or contributed to a death or serious injury, the malfunction is likely to do so again if it recurs.[113] As such, "once a malfunction causes or contributes to a death or serious injury, [manufacturers] have an obligation to file MDRs for additional reports of that malfunction."[114] The presumption was originally included in FDA’s 1997 guidance on reporting but was omitted from its 2013 draft guidance on the same topic. The recent final guidance states that the "presumption will continue until either the malfunction has caused or contributed to no further deaths or serious injuries for two years, or the manufacturer can show through valid data that the likelihood of another death or serious injury as a result of the malfunction is remote."[115] FDA further "recommends that [manufacturers] submit a notification to FDA with a summary of the data and the rationale for [the] decision to cease reporting at the end of two years."[116]

IV. Medical Devices

A. FDA Guidance

As in the first half of the year, CDRH issued a significant number of important draft and final guidance documents on a wide range of issues in the second half of 2016.

On July 27, 2016, recognizing that adaptive designs for medical device clinical trials can conserve resources, shorten study completion time, and increase the chance for study success, FDA finalized guidance outlining how to structure medical device trials to allow for adaptation based on the accumulation of study data.[117] On August 5, 2016, FDA issued draft guidance in the form of an International Medical Device Regulators Forum ("IMDRF") proposal, recommending clinical-evaluation methods and clinical-evidence thresholds for the submission of a Software as a Medical Device ("SaMD").[118] And on November 8, 2016, FDA finalized a lengthy question-and-answer style guidance to aid device manufacturers in complying with the Medical Device Reporting ("MDR") requirement.[119]

Below we detail additional guidance issued in the second half of 2016.

1. Developing a Medical Device National Evaluation System

As we reported in our 2015 Year-End and 2016 Mid-Year Updates, the CDRH’s first strategic priority for 2016 and 2017 was the development of a National Evaluation System ("NEST") for medical devices that would capture and utilize real-world electronic health information to inform regulatory decision-making regarding devices.[120] To achieve this goal, CDRH intends to gain access to 100 million electronic patient records via device identifiers to "increase by 100 percent the number of premarket and postmarket regulatory decisions that leverage real-world evidence" compared to the "FY2015 baseline."[121]

In acknowledgment of the fact that implementation of a Unique Device Identifier ("UDI") program is a prerequisite to NEST, on July 26, 2016, FDA issued draft guidance on the expected content and form of UDIs required under the 2013 UDI System rule.[122] But CMS has publicly opposed FDA’s plan to use claims data with UDIs to monitor safety, arguing that "including UDIs on claims would entail significant technological challenges, costs and risks" for Medicare.[123] Nevertheless, HHS Secretary Sylvia Burwell has publicly voiced support for the initiative, noting that the Sentinel Initiative–FDA’s program for reporting and monitoring the safety of all regulated medical products–will be improved by "incorporating UDIs into its claims data sources."[124]

In finalized guidance issued on August 30, 2016, FDA indicated that it does not intend to enforce the 2013 UDI System rule’s prohibition of the inclusion of National Health Related Item Code or National Drug Code numbers on device labels or packaging for finished devices manufactured and labeled prior to September 24, 2021.[125] FDA also indicated that it does not intend to take action against a labeler for incorporating a previously assigned FDA labeler code into its UDI without requesting approval to do so if the labeler submits a compliant request by September 24, 2021.

Relatedly, on July 27, 2016, FDA issued draft guidance addressing how it plans to consider "real-world evidence" derived from sources like claims data when exercising its regulatory decision-making for medical devices.[126] Through this draft guidance, FDA places important limits on what data may be used from NEST once it is implemented. Primarily, FDA emphasizes that its evidentiary standard for decision-making will not be lowered when considering real-world data–FDA intends to consider the real-world data’s quality by examining its relevance and reliability.[127] FDA also excludes "secondary uses" of real-world data, requiring "at a minimum[] a prospective analysis plan," due to concerns of inherent bias in retrospective analyses of real-world data.[128] Finally, FDA provides additional examples of actual regulatory uses of real-world evidence, including the use of a national device registry to support an application for an expanded indication for use of a product and the use of a patient registry to support postmarket surveillance studies under § 522 of the FDCA.[129]

2. Public Notification of Emerging Signals

On December 14, 2016, FDA released its final guidance regarding its policy on notifying the public regarding "emerging signals."[130] FDA defines an "emerging signal" as "new information about a marketed medical device . . . that supports a new causal association or a new aspect of a known association between a device and adverse event or set of adverse events" which "has the potential to impact patient management decisions and/or the known benefit-risk profile of the device."[131] FDA provided thirteen non-exclusive factors that it may consider in determining whether to issue a public notification regarding an emerging signal, including: the "likelihood" and "magnitude" of potential "harmful event(s)," the benefit provided by the device, potential device alternatives, and the quality and strength of the data and causal connection evidence.[132] FDA intends to conduct an initial assessment of the need to issue a public notification about an emerging signal within thirty days of receiving the relevant information.[133]

FDA’s final guidance clarified that the agency will not issue a notice unless "credible scientific evidence supports a new causal relationship."[134] This standard appears to require more evidence for the issuance of a public notification than did FDA’s December 2015 draft guidance, possibly in response to several industry concerns that the policy could be more harmful than helpful by causing providers and patients to unnecessarily avoid beneficial devices.[135]

3. 510(k) Submissions for Changes to Existing Devices

On August 8, 2016, FDA issued two draft guidance documents for public comment regarding when device manufacturers should submit a 510(k) for changes made to a device or its software.[136] FDA issued its existing final guidance on the topic in January 1997.[137] FDA’s first attempt to replace this guidance back in 2011 ignited industry fears that the new guidance would require 510(k)s to be submitted for substantially more modifications than required under the 1997 guidance. Given this concern, Congress ultimately ordered FDA to withdraw its 2011 draft guidance.[138] Following a public workshop held in 2013 with industry and other stakeholders, FDA issued a 2014 report to Congress, claiming that it intended to make targeted revisions to the 1997 guidance and issue a new guidance on software changes, while leaving the "overarching policy framework intact."[139]

The draft guidance documents that FDA issued this year include numerous flowcharts and hypothetical scenarios to assist the industry in determining whether a proposed change is significant enough to require FDA review. Not surprisingly, changes that fall within that category include any major modification to the device that could significantly affect the safety or effectiveness of the device. It remains to be seen whether FDA’s proposed guidance will significantly increase the number of 510(k)s filed for existing devices. FDA’s pace of clearing 510(k) devices has remained fairly steady over the past years such that an uptick in 510(k) submissions could affect the timely approval of such applications unless FDA dedicates additional resources to these reviews.

4. General Wellness and Low-Risk Devices

On July 29, 2016, FDA finalized guidance on "low risk products that promote a healthy lifestyle," referred to by FDA as "general wellness products."[140] The guidance indicates that low-risk general wellness software or hardware products–like meditation, fitness, or sleep mobile applications or wearable fitness monitors–will not require FDA review or compliance with FDA’s premarket and postmarket regulatory requirements.[141]

To qualify as a general wellness product, a product must not claim to diagnose or treat a particular disease or condition; it can, however, claim to improve overall general wellness.[142] Notably, these products may also qualify as general wellness products even if they reference specific diseases or conditions, if the claim relates to reducing the risk of, or "help[ing] liv[e] well with," certain diseases or conditions "as part of a healthy lifestyle."[143]

Such products must also be "low risk" in order to qualify for the regulatory exception.[144] In determining whether a product is "low risk," manufacturers should consider whether CDRH actively regulates products of the same type. If the answer is yes, the product is likely not low risk. Products that are invasive, implanted, and involve a technology that may pose a risk to the safety of users or other persons (such as risks from lasers or radiation exposure) are also likely not low risk. Products that do not fall into these restrictions may qualify as "low risk" and therefore benefit from the above regulatory exception.

5. Evaluation of Benefit-Risk Profile

In August, FDA finalized two guidance documents: one on factors to consider when making benefit-risk determinations for premarket approval ("PMA") of medical devices,[145] and one regarding patient preference information that FDA staff may use to make PMA determinations.[146] Both guidance documents apply to diagnostic and therapeutic devices.

In its benefit-risk guidance, FDA enumerated the categories of factors it considers in making the benefit-risk determination: (1) the extent of the probable benefit of the device considering the type, magnitude, probability, and duration of the benefit; (2) the extent of the probable risks considering the severity, type, number, and rate of harmful events, the probability and duration of harmful events, and the risk from false-positive or false-negative results; and (3) additional factors (such as patient assessments and patient-reported outcomes). Although FDA did not specify how it weighs these additional factors, FDA did provide some helpful examples of actual past benefit-risk determinations.

As a companion to this guidance, FDA issued final guidance addressing how FDA might consider patient-preference information ("PPI") in reviewing premarket approval applications. Consistent with its benefit-risk guidance, FDA indicated "[p]atients provide valuable input" and "PPI may be particularly useful in evaluating a device’s benefit-risk profile when patient decisions are ‘preference sensitive.’"[147] FDA clearly indicated that the guidance does not create any extra burden on sponsors of premarket submissions. Instead, the guidance provides recommendations for "voluntary" collection of PPI.[148] This guidance demonstrates FDA’s continued focus on ensuring that patient perspectives are represented in premarket approval decisions.

6. Postmarket Management of Cybersecurity in Medical Devices

In keeping with its focus on cybersecurity issues reported in our 2014 and 2015 Year-End Updates, FDA finalized its early-2016 draft guidance regarding postmarket management of cybersecurity risks for medical devices at the end of the year.[149]

The guidance re-emphasizes that manufacturers must consider cybersecurity issues throughout the life cycle of a medical device, not just during the premarket phase.[150] In doing so, FDA recommends that device manufacturers participate in an Information Sharing Analysis Organization ("ISAO") to exchange information regarding cyber-threats with other industry members and maintain "a defined [and documented] process to systematically conduct a risk evaluation and determine whether a cybersecurity vulnerability affecting a medical device presents an acceptable or unacceptable risk."[151] This process should "focus on assessing the risk of patient harm by considering: 1) The exploitability of the cybersecurity vulnerability, and 2) The severity of patient harm if the vulnerability were to be exploited."[152] By evaluating these two factors, manufacturers should determine whether a "risk of patient harm is controlled (acceptable) or uncontrolled (unacceptable)."[153]

FDA’s guidance recommends ways to address controlled risks (e.g., routine cybersecurity updates and patches) but does not require concomitant reporting (except on an annual basis for premarket approval devices). Uncontrolled risks, on the other hand, must be reported to FDA under the relevant QSRs.[154] The guidance nevertheless makes clear that FDA will not enforce these reporting requirements if: (1) "there are no known serious adverse events or deaths associated with the vulnerability"; (2) the manufacturer communicates risk information to users within thirty days and "develops a remediation plan to bring the residual risk to an acceptable level"; (3) "the manufacturer fixes the vulnerability, validates the change, and distributes the deployment fix" within sixty days; and (4) the manufacturer is an active participant in an ISAO.[155]

B. Update on Regulation of Laboratory Developed Tests

We have previously reported on FDA’s controversial moves toward regulation of Laboratory Developed Tests ("LDTs")–diagnostic tests designed, manufactured, and performed in clinical laboratories–including FDA’s indication that it would be finalizing its 2014 draft guidance regarding regulation of LDTs as medical devices.[156] Although FDA originally projected that it would finalize the guidance in 2016, the presidential election results appear to have stalled the agency’s plans. On November 18, 2016, FDA indicated that it would delay its final guidance on LDTs, announcing that it would instead "continue to work with stakeholders, [the] new Administration, and Congress to get [its] approach right."[157] Whether FDA continues or backs away from its efforts to regulate LDTs under the new administration is a key issue to monitor in 2017.

C. Warning Letters

CDRH issued only four Warning Letters in the second half of 2016, bringing the annual total to nineteen.[158] Each of the four letters identified issues stemming from a prior FDA inspection in which FDA concluded that the methods, facilities, or controls used for product manufacturing were not in conformity with cGMP.

In July, CDRH took issue with a teeth-whitening and dental-floss manufacturer for failing to provide required post-inspection documentation in English.[159] Also in July, FDA chastised a bone-implant device manufacturer for failing to correct alleged deficiencies in its evaluation of the potential risk of distribution of nonconforming products and its process for identifying and reporting adverse events to FDA.[160] In August, CDRH issued a pair of letters each identifying a host of issues: one to a manufacturer of intercranial pressure-monitoring products regarding its alleged failure to correct inadequate data processing, design validation, and corrective and preventive action ("CAPA") procedures,[161] and one to a compression-sock manufacturer regarding its alleged failure to develop adequate validation and CAPA procedures, failure to properly manage complaints, and failure to conduct appropriate audits.[162]

FDA’s actions again demonstrate its willingness to exercise broad jurisdiction–each of the four letters targeted foreign companies (from China, France, Germany, and Italy) that market products in the United States. In three of the four cases, FDA also invoked its authority to refuse entry of the devices at issue into the United States until the company addressed the issues FDA raised in its letter.

V. Anti-Kickback Statute

A. AKS-Related Case Law

Federal courts issued several noteworthy decisions interpreting the AKS during the second half of 2016.

In United States ex rel. Ruscher v. Omnicare, Inc. (an unpublished decision handed down in October 2016), the Fifth Circuit addressed the inducement element of an AKS violation.[163] There, a qui tam relator alleged that Omnicare, a provider of pharmacy services to long-term care facilities, improperly induced skilled nursing facilities to use its pharmacy services by writing off bad debt owed by the facilities and offering prompt-payment discounts to the facilities. According to the relator, Omnicare then falsely certified its compliance with the AKS, resulting in the submission of false or fraudulent claims.

The Fifth Circuit set the table by reiterating the well-worn "one purpose" standard: "Relator need only show that one purpose of the remuneration was to induce . . . referrals."[164] But the court then picked up on a point previously emphasized by the Tenth Circuit in United States v. McClatchey, noting that "[t]here is no AKS violation . . . where the defendant merely hopes or expects referrals from benefits that were designed wholly for other purposes."[165] The Fifth Circuit then examined the District Court’s grant of summary judgment to Omnicare, and concluded that the relator’s evidence, at most, indicated that Omnicare sought to "collect verifiable debt and settle billing disputes without unnecessarily aggravating [skilled nursing facility] clients in the midst of ongoing or anticipated contract negotiations."[166] The relator offered no evidence suggesting Omnicare "designed its settlement negotiations and debt collection practices to induce" referrals.[167] And there was no evidence that Omnicare connected its collection practices to the question of referrals. As the Fifth Circuit observed, "[i]f the purported benefits were designed to encourage [skilled nursing facilities] to refer Medicare and Medicaid patients to Omnicare, one might expect to find evidence showing that the [facilities] at least knew about those benefits."[168] In sum, the Fifth Circuit refocused the inducement inquiry on the "design" of the practice that purportedly remunerated a referral source. Albeit unpublished, this decision may provide defendants in AKS-predicated FCA cases with a template for defending routine business practices that are not designed to induce referrals (even if they are arguably remunerative).

A second notable decision relates to the AKS exception and safe harbor for discounts. By law, the AKS does not impose liability for remuneration that is "a discount or other reduction in price . . . if the reduction in price is properly disclosed and appropriately reflected in the costs claimed or charges made by the provider or entity under a Federal health care program."[169] The regulatory safe harbor also protects discounts "made at the time of the sale" that are "fixed and disclosed in writing . . . at the time of the initial sale," if the provider receiving the discount provides documentation of the discount and the provider’s awareness of its obligation to report the discount "upon request by the Secretary or a State agency."[170] Drug and device manufacturers often rely on this safe harbor to protect procompetitive discount arrangements that benefit patients and payors, but two recent decisions by the District of Massachusetts offer insight on how courts apply the safe harbor.

In United States ex rel. Banigan v. Organon USA, Inc., the relators alleged that Omnicare, Inc. and a group of pharmacies acquired by the company violated the FCA by submitting tainted claims for payment after the pharmacies received purported kickbacks from drug maker Organon through market share rebates via group purchasing organizations ("GPOs").[171] The relators also alleged that Omnicare entered into improper direct purchasing agreements with the drug maker, under which the pharmacy accepted a volume-based discount in exchange for promoting the agreement’s potential financial benefits to its clients. Denying Omnicare’s motion for summary judgment as to its own conduct and that of two of its acquired pharmacies, the court concluded that the relators offered sufficient evidence of scienter and that Omnicare’s discount agreements did not qualify for the statutory or regulatory discount safe harbor. Although Omnicare satisfied the safe harbors’ first requirements (i.e., that the GPOs and direct purchase contracts contained and disclosed all of the agreements’ terms), the court found that Omnicare could not satisfy the second element for either the statutory or regulatory safe harbor.[172] As to the statutory safe harbor, the court cited Omnicare’s failure to offer evidence that discounts were reflected "appropriately" in charges to Medicaid.[173] As to the regulatory safe harbor, the court explained that Omnicare did not show "that it made the relevant disclosures pursuant to a governmental investigation."[174] Despite recognizing that Omnicare could not have made that showing because the government did not investigate Omnicare during the relevant period, the court defended its conclusion by emphasizing that "the statutory and regulatory safe harbors are independent affirmative defenses, and government action a necessary condition only of the latter."[175]

The District of Massachusetts relied on similar reasoning in United States ex rel. Herman v. Coloplast Corp., a case involving FCA claims against CCS Medical for allegedly receiving price discounts from Coloplast, a manufacturer of continence care products, in exchange for converting patients to Coloplast products.[176] The court initially dismissed the claims after CCS argued that its discount arrangement with Coloplast fell within the protection of the discount safe harbors. On reconsideration, however, the court concluded that CCS had not met the second element of the statutory discount exception or safe harbor by showing that the discounts were "’appropriately reflected in the costs claimed or charges made’ to a federal healthcare program, or that CCS ha[d] provided certain information concerning the discounts to a governmental agency pursuant to its request."[177]

The District of Massachusetts’s reasoning is opaque, which is especially unfortunate in light of the case’s potential ramifications. Indeed, conditioning availability of the safe harbor on government action (e.g., a request for information) and the provision of such information in response to the government requests may deprive drug and device makers of the ability to control whether they qualify for the discount safe harbor and statutory exceptions. Even the government has recognized this concern. After the court’s decision, the government filed a Statement of Interest in response to CCS’s motion for reconsideration, in which it disagreed with the court’s interpretation, stating that "safe harbor protection remains available if all other requirements are met" even if the Secretary or a State agency has not requested disclosure.[178]

Although the court did not rely on this argument, the government also argued in a separate Statement of Interest that the discount exception is "narrow,"[179] and that "a price reduction conditioned on promotional or conversion campaign activities is not a ‘discount’ within the meaning of the discount exception at 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b(b)(3)."[180] Therefore, according to the government, "[r]emuneration to health care providers for switching patients from one product to another, and for other efforts to increase a product’s utilization do not qualify as protected price reductions, even if the parties label the remuneration as ‘rebates’ or ‘discounts.’"[181] Whether the government can convince courts of this argument in future proceedings remains to be seen. If the government is successful, drug and device makers may not be able to rely on the discount safe harbors and exceptions, especially for clinically focused performance-based rebates and other formulary rebates where manufacturers may condition rebates on maintaining a certain formulary status for the product.

B. Safe Harbors

As we have previously reported, HHS OIG published a proposed rule on October 3, 2014, with an eye toward creating additional safe harbors to the AKS and protecting certain payment practices and business arrangements from sanctions. After more than two years, HHS OIG finalized that rule in December 2016, formalizing a safe harbor for discounts provided by drug manufacturers on "applicable drugs" to "applicable beneficiaries" under the pre-existing Medicare Coverage Gap Discount Program.[182]

Through the Medicare Coverage Gap Discount Program, prescription drug manufacturers can enter into agreements with the Secretary of HHS to provide certain beneficiaries access to drug discounts at the point of sale. To qualify for the safe harbor, manufacturers must also participate in and be "in full compliance with all requirements of[] the Medicare Coverage Gap Discount Program."[183] The impact of the change in language from "full compliance with all requirements" in the proposed rule remains to be seen, but HHS OIG explained in commentary to the final rule that "minor, technical instances of non-compliance should not preclude safe harbor protection." As an example of a minor slip-up, HHS OIG offered "missing a payment deadline by one day."[184] Manufacturers that "knowingly and willfully provided discounts without complying with the requirements of the Medicare Coverage Gap Discount Program," however, "could be subject to sanctions."[185] The territory between these bounds suggests that HHS OIG has reserved significant enforcement discretion.

C. HHS OIG Guidance

HHS OIG routinely releases advisory opinions in response to inquiries submitted by companies seeking to comply with the AKS. Advisory opinions issued by HHS OIG can provide useful insight into how HHS OIG analyzes potential marketing and promotional activities.