September 4, 2017

There is no doubt that with the new year in 2017 came a great deal of uncertainty for health care providers. But even with the change in administration, new leadership in the key health care oversight positions at the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), and U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), and the whirlwind of failed (for now) efforts to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act, the first half of the year has seen some familiar government activity on the enforcement and compliance fronts. DOJ and the HHS Office of Inspector General (HHS OIG) continue to be extremely active pursuing, and courts continue to mold the contours of, enforcement actions against health care providers of all types under the False Claims (FCA), the Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS), and a variety of other theories based on the health care laws.

As we have done in our previous semiannual updates, below we discuss enforcement and compliance efforts of particular note for health care providers in the following areas: DOJ enforcement, including FCA enforcement and notable criminal prosecutions; HHS enforcement of various administrative sanctions, including HHS OIG actions and HIPAA enforcement; and case law developments and regulatory guidance on the AKS and Stark Law. In addition to this Update, a collection of Gibson Dunn’s recent publications on health care issues impacting providers may be found on our website.

I. DOJ Enforcement Activity

A. False Claims Act Enforcement Activity

Between January 1 and June 30, 2017, the DOJ announced $817 million in FCA recoveries from health care providers, putting it on pace to exceed the approximately $1.1 billion recovered from FCA settlements with providers in all of 2016. The total of 54 health care provider settlements announced during that time is comparable to the 49 settlements announced in the first half of 2016, and the 57 settlements announced in the first half of 2015, showing early signs that the DOJ is not slowing down with the change in administration.

As usual, the FCA settlements announced so far this year have been predicated on a variety of legal theories and have involved a wide variety of different types of providers, including home health providers, pharmacies, physicians, hospitals, billing services, and skilled nursing providers.

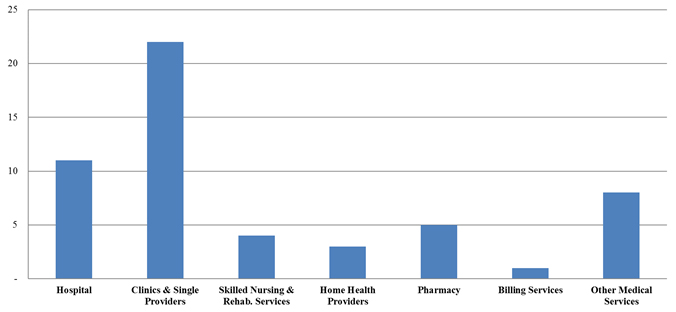

Number of FCA Settlements with Providers, by Provider Type

In terms of the number of settlements so far in 2017, clinics and single-providers cases have easily led the pack, with the majority of these cases resting, in primary part, on allegations of upcoding, lack of medical necessity, and unqualified personnel providing care. Hospital settlements made up the second-largest group, but featured more cases based on alleged violations of the AKS and Stark Law.

Number of FCA Settlements with Providers, by Allegation Type

Overall, medical necessity was by far the most prevalent legal theory among the provider settlements, consistent with prior years, while AKS allegations and claims that services were not provided were also particularly prevalent in the first half of 2017.

One of the largest FCA recoveries in 2017 came from a settlement with electronic health records (EHR) software vendor eClinicalWorks (ECW), which agreed in May to pay $155 million to resolve allegations that ECW misrepresented its software’s capabilities in the process of obtaining certification that would make the company eligible for incentive payments under the government’s Electronic Health Records Incentive Program.[1] Notably, the DOJ announced that under the terms of the settlement agreement, the company’s three founders agreed to be jointly and severally liable for the full amount of the payment by ECW, and three other individuals—a software developer and two project managers—were required separately to pay a total of $80,000. Additionally, as part of the settlement, ECW entered into a five-year Corporate Integrity Agreement that, in addition to other requirements, calls for the retention of an Independent Software Quality Oversight Organization. ECW’s settlement may have been the first in a wave of enforcement efforts involving EHR incentive payments. In June, HHS OIG issued a report finding that CMS overpaid $729 million under the incentive payments program to providers that did not comply with program requirements between May 2011 and June 2014.[2] Soon thereafter, HHS OIG announced that it would review hospitals’ incentive payments between 2011 and 2016 "to identify potential overpayments that the hospitals would have received as a result of [incentive payment calculation] inaccuracies."[3] In light of the ECW settlement and recent attention to the issue in Congress,[4] it is likely that we have not seen the last of DOJ and HHS OIG enforcement actions, under the FCA and otherwise, involving this program.

One of the most significant FCA developments this year is not reflected in the summary data above: a jury verdict of $347 million in a declined case, pursued by the relator to trial, against skilled nursing facility operator Consulate Health Care in the Middle District of Florida.[5] In United States ex rel. Ruckh v. CMC II LLC et al., the relator, a former nurse at two of the defendant’s facilities, alleged the defendant artificially increased the amount of care patients required, resulting in inflated Resource Utilization Group reimbursements from the Medicare program in violation of the FCA. The jury found the claims affected by that alleged conduct resulted in more than $115 million in single damages, which are subject to mandatory trebling under the statute, along with per-claim civil penalties. Post-trial motions practice is ongoing, but if the verdict stands, it will be the second trial verdict exceeding $300 million obtained by a relator in a declined case in the past two years—a stark reminder of the massive potential sanctions under the FCA for cases litigated all the way to trial.

In notable contrast, one of the largest skilled nursing facility operators in the country, Genesis Healthcare Inc., opted this year to settle a similar set of FCA claims and avoid litigating to trial. In June, Genesis paid $53.6 million to resolve the DOJ’s investigation and six qui tam lawsuits involving allegations that the company and its subsidiaries and predecessors submitted false claims for medically unnecessary hospice services, medically unnecessary therapy services, and care that was materially substandard.[6] Though the Genesis settlement amount was based upon the company’s ability to pay, the juxtaposition of that amount against the Ruckh verdict is a reminder of the heavy potential sanctions under the FCA for cases litigated all the way to trial.

B. FCA-Related Case Law Developments

1. Developments in the Implied False Certification Theory Since Escobar

It has now been a year since the Supreme Court recognized and defined, in Universal Health Services Inc. v. United States ex rel. Escobar, the so-called "implied certification theory" as a basis for FCA liability. Specifically, in Escobar, the Supreme Court held that there could be FCA liability under the implied certification theory of liability "at least where two conditions are satisfied: first, the claim does not merely request payment, but also makes specific representations about the goods or services provided; and second, the defendant’s failure to disclose noncompliance with material statutory, regulatory, or contractual requirements makes those representations misleading half-truths."[7] This theory of liability is of particular importance to health care providers, who, like the provider in Escobar, could be subject to liability for a potentially wide variety of regulatory violations if those violations make something about the providers’ reimbursement claims into misleading "half-truths." In the first half of 2017, more and more courts grappled with how to analyze implied certification claims under the guidance of Escobar. We briefly summarize some of the most notable examples of that case law below. For additional discussion of these and other recent FCA developments, please refer to our 2017 False Claims Act Mid-Year Update.

In particular, courts are continuing to answer, directly or indirectly, a potentially key question left open by Escobar—must FCA plaintiffs show a "specific representation" on a defendant’s claim for payment to ground implied certification liability. Or, in other words, must both of Escobar‘s "two conditions" be satisfied? Circuit courts have seemingly come to different conclusions in the first half of 2017. For example, in United States ex rel. Badr v. Triple Canopy, Inc.,[8] the Fourth Circuit found that the relator’s claims—that the defendant’s guards billed to the government did not meet marksmanship requirements—were viable under an implied certification theory even though the defendant’s claims contained no "specific representation" about marksmanship qualifications. The Ninth Circuit, however, seemed to take a different view in two cases in which it analyzed implied certification claims under the assumption that both of Escobar‘s "two conditions" are required—United States ex rel. Kelly v. Serco, Inc.[9] and United States ex rel. Campie v. Gilead Sciences, Inc.[10] Even in those cases, though, the court did not appear to take a particularly rigorous view of how to prove an actionable "specific representation"—in Campie, for instance, the Ninth Circuit stated that the brand name of the defendant’s drug could itself be a "representation" of the fact that the drug had received FDA approval.[11]

On Escobar‘s second "condition" for implied certification liability, a number of courts in the first half of 2017 analyzed how certain alleged noncompliance with legal rules might (or might not) be material to the government’s payment decision. Perhaps most notably for health care providers, a rapidly growing number of courts have taken the view, suggested in Escobar, that an alleged regulatory violation is not material to government payment if the government knows of the violation and continues to pay the defendant’s claims anyway. In fact, several courts in 2017 have gone so far as to suggest that the government’s decision not to intervene in the qui tam that originated the FCA claims itself can be proof of the immateriality of the defendant’s conduct.[12] These cases could prove to be an important firewall for providers, given the extensive federal and state government survey apparatus that frequently results in findings of regulatory noncompliance where the consequence is that the providers must undertake corrective actions, not repay claims for reimbursement.

2. Notable Development on FCA Scienter

In May 2017, the Eleventh Circuit issued an opinion regarding the application of the FCA scienter element in a case in which a defendant relied upon a reasonable interpretation of an ambiguous regulation.[13] In United States ex rel. Phalp v. Lincare Holdings Inc., the relators alleged that defendants, suppliers of oxygen and respiratory therapy services, submitted claims without authorization from the relevant Medicare beneficiaries and after making unsolicited telemarketing calls to Medicare beneficiaries, thereby allegedly violating Medicare regulations and the FCA. The district court determined that the relators failed to provide evidence that false claims were submitted "knowingly," stating that "a defendant’s reasonable interpretation of any ambiguity inherent in the regulations belies the scienter necessary to establish a claim of fraud under the FCA." The Eleventh Circuit upheld the lower court’s ruling, but with a tweak to the district court’s analysis, noting that FCA scienter can exist even if a provider’s interpretation of a vague regulation was reasonable. The court explained that it wanted to preclude allowing FCA defendants to escape liability by adopting a "reasonable interpretation" of a regulation that they did not hold at the time the claims were submitted. The decision could have a particular impact on health care provider defendants in FCA cases, which frequently see theories based on alleged violations of vague or broadly defined reimbursement requirements that leave a great deal of discretion to the treating clinician.

3. Update on Fourth Circuit Opinion in Michaels

In our 2016 Year-End Providers Update, we noted that the Fourth Circuit, in United States ex rel. Michaels v. Agape Senior Community, Inc.,[14] would have an opportunity to hear argument on a crucial issue for health care providers in FCA cases: whether statistical sampling can be used to prove FCA liability, particularly for cases in which the theory of liability is predicated on a claim-specific review of only a sample of the claims submitted. However, the Michaels court declined to reach this issue. The court unanimously decided that it had erred in granting interlocutory review of the issue, since the statistical sampling question was not a purely legal one. Accordingly, the district court decision denying relators the use of statistical sampling stands for the time being.

The Fourth Circuit did decide, however, that the DOJ may veto a settlement in an FCA case it has not actually joined and that such a veto is not subject to review. The court found that the language of the FCA imposed no limitation on the government in that regard.

C. Criminal Enforcement Actions

On July 13, 2017, the DOJ announced the largest-ever health care fraud enforcement action in its history. The DOJ brought charges against 412 individuals—including many physicians and pharmacists—who were allegedly responsible for $1.3 billion in health care fraud losses by Medicaid, Medicare, and TRICARE.[15] The action was coordinated by the Criminal Division’s Health Care Fraud Unit and its partners in the Medicare Fraud Strike Force, and involved the Drug Enforcement Administration, Defense Criminal Investigative Service, and State Medicaid Fraud Control Units. The enforcement action was focused heavily on the distribution of medically unnecessary prescription drugs, including the unlawful distribution of opioids and other prescription narcotics. However, the cases involved a range of other theories, including embezzlement and theft, fraudulent billing, illegal kickbacks, and money laundering. The action currently involves cases across more than 30 states and Puerto Rico.

HHS Secretary Tom Price emphasized the current administration’s focus on addressing health care fraud, stating: "The historic results of this year’s national takedown represent significant progress toward protecting the integrity and sustainability of Medicare and Medicaid, which we will continue to build upon in the years to come."[16] Given the breadth of this enforcement action and the current administration’s stated dedication to health care fraud enforcement generally, we anticipate seeing continued efforts on this front.

The DOJ’s announcement of the nationwide "takedown" was also notable for its reference to various defendants arrested on charges related to fraudulent distribution of opioids, which has become a priority issue for the new administration. Indeed, shortly after the "takedown" was announced, Attorney General Jeff Sessions also announced the formation of a new "Opioid Fraud and Abuse Detection Unit."[17] The new unit will involve participation by twelve different districts around the country and will focus on using data analytics to identify those "contributing to [the] opioid epidemic." The metrics used will include the number of opioid prescriptions written or dispensed in comparison to physicians’ and pharmacies’ peers, the number of patients of each physician who have died within 60 days of an opioid prescription, and the average age of patients receiving the opioid prescriptions.

II. HHS Enforcement Activity

A. HHS OIG Activity

1. Developments and Trends in 2017

According to its Semiannual Report to Congress, although the numbers of reported HHS OIG criminal and civil actions are up in the first half of Fiscal Year 2017, as compared to Fiscal Year 2016, HHS OIG’s expected investigative recoveries are slightly down.[18] Through the first half of Fiscal Year 2017, HHS OIG has reported 468 criminal actions and 461 civil actions, including FCA suits, civil monetary penalty (CMP) settlements, and administrative recoveries, against individuals or entities.[19] During the first half of Fiscal Year 2017, OIG reported expected investigative recoveries of over $2.04 billion.

2. Final Rule on Exclusions

In January 2017, HHS OIG finalized a rule that imposes a 10-year limitations period on HHS OIG exclusion actions brought on the basis of violations of the AKS.[20] HHS OIG had originally proposed to amend the relevant regulation to clarify that there was no limitations period. However, in response to numerous comments objecting to the proposal, HHS OIG decided to adopt a 10-year limitations period. In doing so, HHS OIG expressed the notable concern that "any limitations period on . . . exclusions may force OIG to either initiate administrative proceedings while [a given FCA] matter is proceeding or lose the ability to protect the programs and beneficiaries through an exclusion. Litigating FCA and exclusion actions on parallel tracks wastes Government (both administrative and judicial) and private resources."[21] Nevertheless, HHS OIG concluded that "such situations will be less frequent with a 10-year period than with a shorter period," and that a 10-year period balances the goal of avoiding government waste against the goals of "provid[ing] certainty" and avoiding the "administrative burden" of indefinite document retention that regulated parties could incur were HHS OIG to explicitly adopt an indefinite limitations period.[22] HHS OIG’s response to the comments it received also noted the alignment between a 10-year limitations period and the FCA’s 10-year statute of repose,[23] and stated that, while recent conduct is more relevant to exclusion decisions, HHS OIG’s experience has shown that "exclusion can be necessary to protect the Federal health care programs even when the conduct is up to 10 years old."[24]

The final rule also significantly expanded the scope of HHS OIG’s permissive exclusion authority, implementing and building upon changes included in the Affordable Care Act ("ACA") by allowing the agency to exclude individuals or entities who "request or receive payment" relating to covered items or services; who are convicted for obstruction of audits related to the "use of funds received, directly or indirectly, from any Federal health care program"; who have ownership or control interest in excluded entities; or who knowingly make or cause to be made "any false statement, omission, or misrepresentation of a material fact in any application, agreement, bid, or contract to participate or enroll as a provider of services or supplier under a Federal health care program."[25]

3. Significant HHS OIG Enforcement Activity

a) Exclusions

An important force behind many resolution of enforcement actions in which HHS OIG is involved is the potential for exclusion from government health programs, which can be a crippling (if not fatal) sanction for many providers and other companies in the health care industry. Exclusion from government programs must be imposed upon any entity or individual engaged in a patient abuse-related crime, felony health care fraud, or the use, manufacture, distribution, or prescription of controlled substances.[26] HHS OIG has discretion to impose the penalty in cases of fraudulent conduct, in cases involving the submission of claims for unnecessary treatments or procedures, and in connection with a license suspension or Corporate Integrity Agreement (CIA).[27]

HHS OIG excluded 2,041 individuals and entities during the first half of calendar year 2017.[28] These exclusions include 40 entities (already almost meeting calendar year 2016’s total of 41 entities), with pharmacies accounting for 10 exclusions and mental health facilities accounting for 6 exclusions. Among excluded individuals, 208 have been identified as business owners or executives. Home health agencies continue to be an area of focus for HHS OIG, accounting for over 25% of the exclusions for business owners or executives in the first half of calendar year 2017. As with entities, HHS OIG is also focused on business owners and executives of pharmacies, with over 17% of the excluded business owners and executives in the first half of calendar year 2017 having been identified as affiliated with a pharmacy.

b) Civil Monetary Penalties

In the first half of the 2017 calendar year, HHS OIG announced 47 CMPs as a result of settlement agreements and self-disclosures and recovered nearly $23 million, representing a slowdown in pace from calendar year 2016.[29] Of the top-ten largest penalties for the first half of calendar year 2017, seven of the penalties were the result of self-disclosure to HHS OIG. False and fraudulent billing and improper claims for payment were the leading reason for the assessment of CMPs, accounting for 23 of the announced CMPs thus far in 2017 and over $12.2 million in penalties. As in past years, HHS OIG also routinely pursued CMPs where entities employed individuals that the entities allegedly knew or should have known were excluded from federal health care programs. These cases account for 14 of the CMPs assessed this year, amounting to over $2.9 million in penalties. Penalties also were assessed for violations of the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA), the AKS, and the Stark Law’s physician self-referral prohibitions.

The largest CMPs assessed against providers this year are summarized below:

- Crittenton Hospital Medical Center (CHMC) and Crittenton Cancer Center (CCC): After self-disclosing conduct, CHMC and CCC agreed to the year’s highest penalty thus far, paying $3.2 million to resolve allegations related to physician self-referrals and AKS violations. HHS OIG alleged that CHMC and CCC paid more than fair market value compensation for prohibited financial arrangements with a physician and entities owned by that physician. HHS OIG also alleged that CHMC and CCC had compensation arrangements with the physician and owned entities that were not always set in writing or did not act in accordance with written contracts.[30]

- Hartford Hospital, Connecticut: Hartford Hospital (Hartford) entered into a $2.4 million settlement with HHS OIG to resolve allegations that Hartford submitted claims for home health services within three days of patients’ release from Hartford that were improperly coded as discharged rather than as post-acute care transfer.[31]

- Metro Health Corporation and Metropolitan Hospital: After self-disclosing conduct, Metro Health and its subsidiary agreed to pay $2.3 million to resolve allegations related to physician self-referrals and AKS violations. HHS OIG alleged that Metro Health entered into professional services agreements with two independent contractor physician groups and paid the physician groups in excess of fair market value.[32]

c) Corporate Integrity Agreements

HHS OIG employs CIAs in an effort to ensure that providers comply with Medicare and Medicaid rules and regulations. After a slight decline in calendar year 2016, the first half of 2017 saw an uptick in CIAs, with 24 new CIAs taking effect.[33] CIAs are often linked with other enforcement penalties. For example, as noted above, in May 2017, eClinicalWorks (ECW) entered into a five-year CIA with HHS OIG, which includes the noteworthy requirement that ECW retain an Independent Software Quality Oversight Organization to assess ECW’s software quality control systems and provide semi-annual reports to OIG documenting its reviews and recommendations. HHS OIG continues to pursue CIAs in individual cases and cases involving much smaller payment amounts. In May, for example, a California dentist entered into a $31,000 settlement agreement, as well as a three-year CIA, to resolve allegations that the dentist submitted claims for medically unnecessary services for a number of Medicaid dental beneficiaries.[34]

B. CMS Activity

1. Transparency and Data Accessibility

As previously discussed, CMS has prioritized improving access to data related to the use of Medicare and Medicaid services over the past few years. As part of this ongoing effort, CMS has released two additional data sets and one updated data tool thus far in 2017:

- Health Care Spending by State for 1991-2014.[35] The data, released by CMS’s Office of the Actuary, updates previous estimates published in 2011 and "examines personal health care spending (or the health care goods and services consumed) through a resident-based view."[36] For each state, the data "is presented both by type of goods and services (such as hospital services and retail prescription drugs) and by major payer (including Medicare, Medicaid, and private health insurance)."[37]

- Healthcare Disparities by Race, Ethnicity, & Gender.[38] CMS’s Office of Minority Health released two reports detailing the quality of care received specifically by Medicare Advantage enrollees. The first report focused on disparities by gender, while the second examined "racial and ethnic differences in health care experiences and clinical care among women and men."[39]

- Market Saturation and Utilization Tool.[40] In July, CMS announced its fifth update of this important data tool, which provides interactive maps and related data sets showing provider services and utilization data. The updated tool includes long-term care hospital and chiropractic services data in addition to the previous categories of data.

2. Continued Implementation of Moratoria

On January 29, 2017, CMS extended for six months the moratoria on nonemergency ambulance suppliers and home health care agencies in six states that are designated as "hot spots" for fraud under the ACA.[41] The moratoria blocks any new provider enrollments for nonemergency ambulance services in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Texas, and for home health agencies in Florida, Texas, Illinois, and Michigan.[42] The moratoria are imposed after consultation with the DOJ and HHS OIG[43] (and, in the case of Medicaid, with State Medicaid agencies) and will be continuously reviewed every six months to assess whether they remain necessary.[44]

C. OCR and HIPAA Enforcement

In June 2017, HHS’s Office of Civil Rights (OCR) reported that it had reviewed and resolved 156,467 Health Information Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) complaints since HIPAA privacy rules went into effect in April 2003.[45] Nearly 28,000 of these complaints have been resolved in just the past year.[46] Since January, OCR has reported nine new settlements amounting to $17 million in fines.[47] At this pace, fines imposed in 2017 are likely to far exceed the $23.5 million in fines imposed during the 2016 calendar year.

Protection of patients’ confidential information remains a priority for HHS, and providers should expect HIPAA scrutiny to increase as OCR focuses on providers’ role in minimizing the impacts of data breaches.

1. Trends to Date

OCR has continued to ramp up its scrutiny of cybersecurity and providers’ responses to data breaches in 2017. In June, OCR issued its cyber-attack "quick-response" guidance, which explains the four steps HIPAA-covered entities and their business associates should take in response to cyber-related security incidents.[48] In the event of a cyber-attack or a similar emergency, an entity: (1) must execute its response and mitigation procedures and contingency plans; (2) should report the crime to other law enforcement agencies; (3) should report all cyber threat indicators to the appropriate federal agencies and information-sharing and analysis organizations; and (4) must report the breach to OCR as soon as possible, but no later than 60 days after the discovery of a breach affecting 500 or more individuals. The "quick-response" guidance provides additional detail and references for each of these steps, and is accompanied by an "infographic" that helps to make the guidance more accessible for providers.[49]

OCR also continued to issue its "Cyber Awareness Newsletters" that provide guidance on what specific security measures providers can take to decrease the possibility of being exposed by the various security threats and vulnerabilities that exist in the healthcare sector, and how to reduce breaches of electronic personal health information (ePHI).[50] For example, OCR’s January newsletter provided guidance on how HIPAA-covered entities should comply with, and the importance of, the Security Rule’s Audit Controls standard, 45 C.F.R. § 164.312(b).[51] OCR’s February newsletter urged relevant entities to report any suspicious activity, including cybersecurity incidents, cyber threat indicators and defensive measures, phishing incidents, malware, and software vulnerabilities to the U.S. Computer Emergency Readiness Team (US-CERT) within DHS, which is responsible for analyzing data, developing timely and actionable information on threats to governments and private industry, and responding to cybersecurity incidents.[52] OCR’s June newsletter stressed that entities must account for the security concerns that accompany the implementation of file sharing and collaboration tools in their risk analyses, risk management policies, and business associate agreements.[53]

2. HIPAA Enforcement Actions

OCR has announced nine resolutions of HIPAA matters since the start of the calendar year, with the resolutions far exceeding the fines imposed at this time last year. Five of these resolution agreements have resulted in seven-figure fines.

- Significantly, this year brought the first HIPAA enforcement action for the lack of a timely breach notification.[54] Illinois health care network, Presence Health, agreed to pay $475,000 to settle allegations that it violated HIPAA’s Breach Notification Rule by failing to notify patients of a breach within the 60-day period. In October 2013, Presence discovered that paper-based operating room schedules, containing the PHI of 836 individuals, went missing. Presence did not file a breach notification report with OCR until January 31, 2014, and also did not notify the individuals affected by the breach or prominent media outlets within the 60-day period.

- In this year’s largest settlement, which OCR announced in February and stated was meant to "shine[] [a] light on the importance of audit controls," South Florida-based Memorial Healthcare System (MHS) agreed to pay $5.5 million to settle allegations that it violated HIPAA Privacy and Security Rules.[55] MHS reported to OCR that the ePHI of more than 115,000 individuals had been impermissibly accessed by its employees and improperly disclosed to affiliated-physician office staff when the login credentials of a former employee had been used to access the ePHI on a daily basis without detection for a year. According to OCR, MHS "failed to implement procedures with respect to reviewing, modifying, [or] terminating users’ right of access," despite having identified a risk over a period of several years.[56]

- In January, Children’s Medical Center of Dallas agreed to pay a $3.2 million penalty for impermissible disclosure of unsecured ePHI and alleged noncompliance with the HIPAA Security Rule over a period of many years.[57] The penalty followed several separate incidents resulting in the loss of ePHI, including the loss of an unencrypted, non-password protected Blackberry with the ePHI of 3,800 individuals and the theft of an unencrypted laptop with the ePHI of 2,462 individuals. OCR’s investigation revealed that Children’s did not deploy encryption or other security measures on its laptops, work stations, mobile devices, and removable storage media for several years after the incidents, despite being aware of the risks.

- In April, wireless health services provider CardioNet agreed to pay $2.5 million to settle allegations that it violated the HIPAA Privacy and Security Rules after an employee’s laptop containing the ePHI of over 1,300 individuals was stolen from a parked vehicle.[58] OCR’s investigation revealed that CardioNet had insufficient risk analysis and risk management processes in place at the time of the theft and that its HIPAA policies and procedures were in draft form and had not yet been implemented.

- In May, Texas-based Memorial Hermann Health System MHHS agreed to pay $2.4 million to settle allegations that it violated the HIPAA Privacy Rule by including a patient’s name in the title of a press release, which was approved by the company’s senior management, and by failing to timely sanction its employees.[59] The press release described a 2015 incident in which a patient at one of the company’s clinics presented an allegedly fraudulent identification card to office staff and was subsequently arrested.

III. AKS Developments

A. AKS-Related Case Law Developments

Federal courts handed down a number of interesting decisions applying a variety of important principles related to the AKS, with respect to the "one purpose test" and intent to induce; the scope of the AKS’s scienter requirement; the meaning of "remuneration"; the relationship between remuneration and referrals; and the contours of relevant evidence in AKS cases.

1. The "One Purpose Test"

Broadly speaking, the AKS prohibits offering or receiving remuneration intended to induce referrals of goods or services reimbursed by federal health programs.[60] Some courts have taken a rather broad view of how to apply the intent-to-induce element, holding that AKS liability can attach to remuneration if only one purpose among multiple, other legitimate purposes was to induce referrals. In recent years, the theory has been questioned by some commenters and courts, but recently, in United States v. Nagelvoort,[61] the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit declined to strike down the "one purpose test" as unconstitutionally vague.[62] Nagelvoort, a former hospital administrator, was convicted of violating the AKS by providing physicians various forms of remuneration in exchange for referrals of patients to the hospital at which he worked.[63] On appeal, he argued that the "one purpose test" threatens to render illegal "every contractual relationship a [h]ospital has with a doctor," and that the proper test for intent under the AKS should be whether inducing referrals is the "primary or substantial purpose" of the remuneration in question.[64] Relying on a 2011 decision in which it rejected a similar challenge to the "one purpose" test, the Seventh Circuit declined to revisit its approach to the AKS’s intent requirement and upheld the "one purpose" test amid Nagelvoort’s constitutional challenge.[65]

2. Scienter under the AKS

Liability under the AKS also requires that the defendant has acted "knowingly and willfully,"[66] which the Supreme Court has generally said means with "knowledge the conduct [is] unlawful."[67] In a criminal case decided in June, United States v. Waller,[68] the defendant challenged the court’s failure to define "willfully" as requiring a showing of specific intent to defraud.[69] The jury instruction the court gave stated that Waller need not have known of the AKS or have had specific intent to violate it, and used the word "willfully" only by way of stating that "[t]he government must prove that the defendant willfully committed an act that violated the [AKS]."[70] The court, Waller argued, should have required a showing of specific intent to defraud, because a mere "knowing violation" is insufficient to establish AKS liability.[71] The court rejected Waller’s argument as inconsistent with Fifth Circuit precedent which held—on the basis of the AKS’s text—that the AKS does not require a showing of specific intent to violate the statute.[72] As such, the court indicated a reluctance to introduce any sort of specific intent requirement into the AKS analysis, even in the modified form ("specific intent to defraud") proposed by Waller.[73] The court similarly rejected Waller’s argument that the AKS implicitly incorporates a requirement of materiality due to its close relationship to the FCA.[74] No materiality element could be inferred in the AKS context, the court held, where Congress itself did not explicitly use the word "fraud" or "defraud" in the statute.[75]

3. The Meaning of "Remuneration"

As noted above, AKS liability attaches to "remuneration," which some courts have defined very broadly to include (with some exceptions) virtually anything of value. It is well known that the AKS applies where such remuneration is given in exchange for referrals or recommendations of federally reimbursed goods or services. But a separate provision of the AKS, which has received much less attention in the case law, attaches liability where the remuneration is provided in return for "arranging for" the furnishing of a federally reimbursed item. In United States v. Addus HomeCare Corp.,[76] a federal District Court recently had the opportunity to weigh in on the scope of the "arranging for" provision. In Addus, the relator alleged a False Claims Act scheme whereby a defendant home health provider would "arrange for" physicians from the co-defendant provider to visit patient homes to certify those patients for home health care, even if the patient was not eligible for such care.[77] In exchange for those certifications, the home health provider allegedly would refer to its co-defendant any of its patients that needed physician services.[78] The court held that the false certifications of patients’ eligibility for home health services themselves constituted remuneration under the AKS, even though no "payment or compensation" was made. The court explained that the false certifications made it possible for the provider who received the certifications to bill Medicare for home health services provided to the patients in question, which was enough to constitute actionable remuneration as "any thing[] of value [provided] to the alleged recipient[]."[79]

4. The Relationship Between Remuneration and Referrals

In United States ex rel. Graziosi v. Accretive Health, Inc., another district court reinforced the idea that a kickback need not actually result in a referral, purchase, or other act to violate the AKS.[80] In Graziosi, an FCA case, the relator alleged that the defendant, a hospital operations consultant, received payments from hospitals in exchange for written recommendations that certain patients be designated as eligible for inpatient admission.[81] In moving to dismiss the case, one of the defendant hospital systems argued that the consulting defendant’s alleged conduct had no "impact on patient care," and that the alleged kickback scheme did not result in the patients receiving any treatment they would not otherwise have received.[82] The court held that this was irrelevant and that the consulting defendant need only have recommended the services in return for the kickbacks—regardless of whether the services were ever provided. The court reasoned that requiring a showing that services were actually provided "would create a loophole for services that were recommended and billed, but not actually provided, which cannot have been the intent of the statute’s drafters."[83] It is difficult to see how this analysis squares with the elements of a False Claims Act violation—especially causation—as opposed to a stand-alone AKS violation.

5. Evidentiary Developments: Medical Necessity and Fair Market Value

In a unique FCA opinion issued in April, United States ex rel. Cairns v. D.S. Medical L.L.C., a federal judge ruled that the government could support kickback claims by introducing evidence regarding the medical necessity of the allegedly related services performed and devices used by the physician.[84] To support its allegations that a defendant physician’s selections of a co-defendant distributor’s medical devices were the product of illegal kickback payments, the government proffered evidence that the devices and certain services by the physician were not medically necessary. The government’s theory was that such evidence would distinguish the physician’s use of the devices in question from other physicians’ use, and so help show the physician’s state of mind regarding the financial implications of his use of the distributor’s devices.[85] In ruling on what it called a "somewhat close question," the court held that the evidence was "probative of [the physician’s] intent," and that the potential prejudicial effect of the evidence did not substantially outweigh its probative value.[86]

In another recent and instructive evidentiary ruling bearing on proof in AKS cases, United States v. Moshiri, the Seventh Circuit upheld a trial judge’s decision to permit expert testimony relevant to the fair market value of a teaching contract that the defendant allegedly received as a kickback.[87] The expert in question did not actually render an opinion regarding the transaction’s fair market value; rather, he merely testified as to how the value of the contract at issue compared to contracts with which he was familiar based on "industry norms."[88] The court held that the expert’s "specialized experience and knowledge within the field" was sufficient to qualify the expert as such, and that the lack of a nationwide "empirical analysis" of contracts similar to the defendant’s was not fatal to the admissibility of the expert’s testimony.[89] Although the lack of empirical analysis was relevant to the weight of the expert’s testimony, the court reasoned, it did not affect the admissibility of the testimony in the first instance.[90]

B. Guidance and Regulations

1. Free and Low-Cost Lodging and Meals to Low-Income Patients

In an advisory opinion issued in March, HHS OIG approved a proposed arrangement involving the provision of free and low-cost meals and lodging to low-income patients.[91] Under the arrangement set forth in the advisory opinion, the requestor—the owner and operator of a hospital whose patient population includes individuals "who reside in rural and medically underserved areas"—would provide free or low-cost meals and hotel rooms to patients at certain income thresholds to facilitate their access to "services they may not be able to obtain locally."[92] Any given patient would have to meet specific geographic and income requirements to be eligible for the benefits, and patients would only be evaluated for participation in the program after their treatment appointments had been scheduled.[93] Moreover, the requestor would not engage in advertising or marketing of the meal and lodging benefits to patients, would not seek federal reimbursement for the costs of the program, and would not provide any remuneration to physicians to induce referrals of eligible patients to the hospital.[94]

HHS OIG analyzed the proposed program under Section 1128A(a)(5) of the Social Security Act, which imposes civil monetary penalties on those who induce federal healthcare program beneficiaries to choose particular providers.[95] HHS OIG found that, given the parameters and limitations of the program, the benefits provided to patients would both "promote access to care" for, and "pose a low risk of harm" to, federal health care program beneficiaries—thereby satisfying the "Promotes Access to Care" exception to Section 1128A(a)(5).[96] The opinion did not analyze the AKS extensively and noted that the Promotes Access to Care exception does not apply to the AKS. However, the opinion did conclude that while the proposed program "would constitute remuneration" under the AKS, HHS OIG would not impose administrative sanctions on the requestor, provided that it lacked the "intent to induce or reward referrals."[97] In reaching this conclusion, HHS OIG cited the same factors that it found persuasive in concluding that the proposed program would not violate Section 1128A(a)(5).[98]

2. Reduction or Waiver of Cost Sharing Amounts Owed by Patients in a Clinical Study

In an advisory opinion issued in June, HHS OIG considered a proposal to "reduce or waive, on a non-routine, unadvertised basis, cost-sharing amounts owed by financially needy Medicare beneficiaries for items and services furnished in connection with a clinical research study."[99] The study involved a biomedical system indicated for treating ulcers and other chronic wounds.[100] In the proposal advanced by the parties seeking the advisory opinion, a particular hospital participating in the study would "reduce or waive applicable cost-sharing amounts owed by financially needy beneficiaries for all Study-related items and services."[101] The manufacturer of the system under study would not cover any of these reductions or waivers. The hospital would only inform a given patient of the possibility of reduction or waiver if that patient, upon receiving notice that he or she "may owe cost-sharing amounts in connection with the Study," informed the hospital that he or she could not afford these payments.[102] The hospital would then evaluate the patient’s financial need according to a set of uniform criteria.[103] Neither the hospital nor the manufacturer would advertise the possibility of waiver or reduction of patients’ cost-sharing obligations.[104]

Analyzing the proposal under the Beneficiary Inducement CMP,[105] HHS OIG found that the proposal fit within an exception to the definition of remuneration for any waiver of coinsurance or deductible amounts that are "not offered as part of any advertisement or solicitation"; that are not "routinely" provided; and that are only granted either after a "good faith" determination of financial need, or after "reasonable collection efforts" have failed.[106] Given the non-advertised and "case-by-case" nature of the proposed reductions and waivers in this particular case, along with the "objective criteria" used to determine financial need, HHS OIG found that the proposal fit within this exception.[107] For the same reasons, HHS OIG determined that it would not seek administrative sanctions under the AKS, provided that "the requisite intent to induce or reward referrals of Federal health care program business" remained absent.[108]

IV. Stark Law Developments

The first half of 2017 saw several notable developments related to the physician self-referral law, or Stark Law.[109] On the legislative and regulatory front, these developments included a new self-disclosure protocol from CMS and a Congressional report that touched on the intersection of cybersecurity and Stark Law enforcement. On the case law and enforcement fronts, meanwhile, there were notable cases and settlements that explored and illuminated the broad scope of potential liability under the Stark Law.

A. Regulatory and Legislative Updates

On March 28, 2017, CMS released the final version of its Voluntary Self-Referral Disclosure Protocol (SRDP), which establishes a standardized format for reporting overpayments caused by actual or potential violations of the Stark Law.[110] As we previously reported in these pages, CMS’s revised protocol replaces the protocol CMS released after passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) in 2010 and streamlines the reporting process to conform it to the final overpayment regulations issued in February 2016. Under the streamlined reporting format for self-disclosures, the new SRDP now includes Disclosure, Physician Information, and Financial Analysis Worksheet forms that providers must submit for each disclosure as of June 1, 2017. In 2016, self-disclosures under the SRDP resulted in settlements between CMS and health care providers of more than $6.9 million.[111]

Elsewhere, the Health Care Industry Cybersecurity Task Force, a federal task force established by the Cybersecurity Act of 2015, called for changes to the Stark Law in its final Report on Improving Cybersecurity in the Health Care Industry.[112] To speed the sharing and adoption of improved cybersecurity tools and practices, the Task Force recommended that large health care organizations be able "to share cybersecurity resources and information with their partners." But even though organizations "[o]ften . . . want to provide technology to ensure smaller business partners do not become a liability in the supply chain," the report noted that the Stark Law (and the AKS) can serve as impediments to such sharing agreements. Therefore, the report recommended a "regulatory exception" to the Stark Law to permit such cooperation. Such an exception would surely be welcomed by health care providers that increasingly face cybersecurity threats, but it remains to be seen whether CMS, or Congress, will act on the report’s recommendation, and if so, what such an exception would look like.

Finally, in our 2016 Year-End Update, we noted several legislative initiatives to reexamine the Stark Law and its sweeping scope. With Congress consumed by broader issues of health care reform and potential repeal of PPACA, those initiatives have not moved forward. But we will continue to monitor any health care reform proposals for significant changes to the Stark Law.

B. Case Law Developments

In United States ex rel. Emanuele v. Medicor Associates—a case with potentially broad implications for Stark Law enforcement—a federal district court ruled that the Stark Law’s requirement that financial arrangements with physicians be memorialized in a written agreement can be "material" to the government’s decision to pay claims.[113]

The case involved financial arrangements between a Pennsylvania medical center and a cardiology group, under which a group of cardiologists provided oversight and supervision of the medical center’s cardiology services. Although there were several written agreements memorializing these arrangements, those agreements lapsed at various points (before being renewed) and were sometimes unexecuted, among other minor deficiencies in the paperwork.[114] On summary judgment, the relator relied on the incomplete documentation and contracts to show that the cardiologists could not satisfy relevant Stark Law exceptions, which require a written agreement.[115] Defendants argued, meanwhile, that "even if [the arrangements] violated the Stark Act’s writing requirements, those violations do not rise to the level of materiality required to support an FCA claim."[116]

Despite purporting to apply the "demanding" and "rigorous" materiality standard espoused in Universal Health Services, Inc. v. United States ex rel. Escobar, the district court sided with the relator to hold that "it is clear" that violations of the written agreement requirement are material, because the Stark Law "expressly prohibits Medicare from paying claims that do not satisfy each of its requirements, including every element of any applicable exception."[117] The court noted that the Stark Law’s requirement of a "signature as a manifestation of the parties’ assent to the arrangement . . . plays a role in preventing fraud and abuse."[118]

In so holding, the court essentially mandated perfect adherence to every requirement of Stark Law exceptions. Although the court acknowledged that materiality was a fact issue, by denying summary judgment on these grounds, the court’s decision opens the door for whistleblowers to survive motions to dismiss and summary judgment even where there are only minor, administrative deficiencies in the required paperwork under the Stark Law. This case serves as another reminder, therefore, that Stark Law compliance is a bedeviling exercise and warrants close attention. This is, of course, one district court decision, and we will continue to monitor case law developments in this area.

C. Enforcement

Two settlements also counted among the notable Stark Law developments during the first half of the year and served as reminders of the high price of Stark Law violations.

- In May, two Missouri hospitals agreed to pay $34 million to settle allegations that they made impermissible payments to oncologists in violation of the Stark Law, resulting in false claims under the FCA.[119] The settlement stemmed from allegations that the hospitals paid oncologists, in part, based on a formula that considered the value of their patient referrals, and then submitted claims to Medicare for chemotherapy services referred by those physicians.

- In June, a Los Angeles hospital agreed to pay $42 million to settle allegations that it violated the Stark Law and the AKS by entering into allegedly improper financial relationships with referring physicians.[120] The hospital allegedly paid above-market rates to rent office space in physicians’ offices and entered into marketing arrangements with physicians that allegedly provided undue benefit to those physicians’ practices.

V. Conclusion

As these issues and others important to the healthcare provider community continue to develop, we will track them and report back in our 2017 Year-End Update.

[1] Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Electronic Health Records Vendor to Pay $155 Million to Settle False Claims Act Allegations (May 31, 2017), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/electronic-health-records-vendor-pay-155-million-settle-false-claims-act-allegations.

[2] U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of the Inspector Gen., Medicare Paid Hundreds of Millions in Electronic Health Record Incentive Payments That Did Not Comply With Federal Requirements (June 2017), https://oig.hhs.gov/oas/reports/region5/51400047.pdf.

[3] U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of the Inspector Gen., Nationwide Medicare Electronic Health Record Incentive Payments to Hospital (July 2017), https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/workplan/summary/wp-summary-0000232.asp.

[4] Letter from Sens. Orrin G. Hatch and Charles E. Grassley to CMS Administrator Seema Verma (July 12, 2017), https://www.grassley.senate.gov/sites/default/files/constituents/letter%20to%20CMS%20on%20electronic%20health%20incentive%20payments%207-12-17.pdf.

[5] Ruckh v. CMC II, LLC, No. 8:11-cv-01303 (M.D. Fla. June 10, 2011), ECF Nos. 1, 121, 430, 441-446.

[6] Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Genesis Healthcare Inc. Agrees to Pay Federal Government $53.6 Million to Resolve False Claims Act Allegations Relating to the Provision of Medically Unnecessary Rehabilitation Therapy and Hospice Services (June 16, 2017), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/genesis-healthcare-inc-agrees-pay-federal-government-536-million-resolve-false-claims-act.

[7] 136 S. Ct. 1989, 2001 (2016).

[8] 857 F.3d 174 (4th Cir. 2017).

[9] 846 F.3d 325, 332 (9th Cir. 2017).

[10] 862 F.3d 890, 901 (9th Cir. 2017).

[11] Id. at 902-03.

[12] See, e.g., United States ex rel. Petratos v. Genentech Inc., 855 F.3d 481, 485 (3d Cir. 2017); Abbott v. BP Exploration & Production, Inc., 851 F.3d 384 (5th Cir. 2017).

[13] United States ex rel. Phalp v. Lincare Holdings Inc., 857 F.3d 1148 (11th Cir. 2017).

[14] United States ex rel. Michaels v. Agape Senior Community, Inc., 848 F.3d 330 (4th Cir. 2017).

[15] Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, National Health Care Fraud Takedown Results in Charges Against Over 412 Individuals Responsible for $1.3 Billion in Fraud Losses (July 13, 2017), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/national-health-care-fraud-takedown-results-charges-against-over-412-individuals-responsible.

[16] Id. (internal citations omitted).

[17] Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Attorney General Sessions Announces Opioid Fraud and Abuse Detection Unit (Aug. 2, 2017), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/attorney-general-sessions-announces-opioid-fraud-and-abuse-detection-unit.

[18] See U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of the Inspector Gen., Semiannual Report to Congress, at iv (Apr. 1 – Sept. 30, 2016), https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/archives/semiannual/2016/sar-fall-2016.pdf [hereinafter 2016 SA Report]; U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of the Inspector Gen., Semiannual Report to Congress, at ix (Oct. 1, 2016 – March 31, 2017), https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/archives/semiannual/2017/sar-spring-2017.pdf [hereinafter 2017 SA Report].

[19] 2017 SA Report.

[20] See U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of Inspector Gen., Health Care Programs: Fraud and Abuse; Revisions to the Office of Inspector General’s Exclusion Authorities, 82 Fed. Reg. 4100, 4114 (Jan. 12, 2017), https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2017-01-12/pdf/2016-31390.pdf.

[21] Id. at 4102.

[22] See id. at 4101–02.

[23] See id. at 4102; 31 U.S.C. § 3731(b)(2).

[24] 82 Fed. Reg. at 4102. The final rule applies both to exclusions for conduct that violates the AKS, as well as exclusions for conduct that violates the CMP statute. See id. at 4114; 42 C.F.R. §§ 1001.901(c), 1001.951(c).

[25] 82 Fed. Reg. at 4111-18.

[26] See 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7a.

[27] 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b.

[28] U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of the Inspector Gen., LEIE Downloadable Databases, http://oig.hhs.gov/exclusions/exclusions_list.asp (last visited Aug. 10, 2017).

[29] Data gathered through HHS OIG press releases and publicly available information. See generally U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of the Inspector Gen., Civil Monetary Penalties and Affirmative Exclusions, http://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/enforcement/cmp/index.asp (last visited Aug. 10, 2017) [hereinafter CMP Assessments]; U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of the Inspector Gen., Provider Self-Disclosure Settlements, http://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/enforcement/cmp/psds.asp (last visited Aug. 10, 2017) [hereinafter Provider Self-Disclosure Settlements].

[30] See Provider Self-Disclosure Settlements, supra note 29.

[31] See CMP Assessments, supra note 29.

[32] See Provider Self-Disclosure Settlements, supra note 29.

[33] See U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of the Inspector Gen., Corporate Integrity Agreement Documents, http://oig.hhs.gov/compliance/corporate-integrity-agreements/cia-documents.asp (last visited Aug. 10, 2017).

[34] See CMP Assessments, supra note 29.

[35] Press Release, Ctrs. for Medicare & Medicaid Servs., CMS Releases 1991-2014 Health Care Spending by State (June 14, 2017), https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Press-releases/2017-Press-releases-items/2017-06-14.html.

[36] Id.

[37] Id.

[38] Press Release, Ctrs. for Medicare & Medicaid Servs., CMS releases quality data showing racial, ethnic and gender differences in Medicare Advantage health care during National Minority Health Month (Apr. 13, 2017), https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Press-releases/2017-Press-releases-items/2017-04-13.html?DLPage=1&DLEntries=50&DLFilter=data&DLSort=0&DLSortDir=descending.

[39] Id.

[40] Press Release, Ctrs. for Medicare & Medicaid Servs., Market Saturation and Utilization Data Tool (July 24, 2017), https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2017-Fact-Sheet-items/2017-07-24.html?DLPage=1&DLEntries=10&DLSort=0&DLSortDir=descending.

[41] 82 Fed. Reg. 2363 (Jan. 9, 2017), https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2017/01/09/2016-32007/medicare-medicaid-and-childrens-health-insurance-programs-announcement-of-the-extension-of-temporary; see also The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, Pub. L. No. 111-148, § 6401(a).

[42] See Press Release, Ctrs. for Medicare & Medicaid Servs., CMS extends, expands fraud-fighting enrollment moratoria efforts in six states (July 29, 2016), https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Press-releases/2016-Press-releases-items/2016-07-29-2.html.

[43] 42 C.F.R. § 424.570(a)(2)(iv) (2017) (setting forth these procedures for Medicare moratoria).

[44] Id. § 424.570(b) (2017); id. § 455.470(a)(1) (requiring that Medicaid moratoria be imposed "in accordance with" regulations governing Medicare moratoria); id. § 455.470(c) (requiring that Medicaid moratoria be imposed and extended, as necessary, in six-month increments).

[45] U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Health Information Privacy, Enforcement Highlights (June 30, 2017), https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/compliance-enforcement/data/enforcement-highlights/index.html.

[46] U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Health Information Privacy, Enforcement Highlights (May 31, 2016), https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/compliance-enforcement/data/enforcement-highlights/2017-may/index.html.

[47] Data gathered through HHS press releases and other publicly available information. See generally U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., HIPAA News Releases & Bulletins, https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/newsroom (last visited Aug. 10, 2017).

[48] U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of Civil Rights, My entity just experienced a cyber-attack! What do we do now? (June 2017), https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cyber-attack-checklist-06-2017.pdf.

[49] U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of Civil Rights, Cyber-Attack Quick Response Infographic (June 2017), https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cyber-attack-quick-response-infographic.gif.

[50] U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Security Rule Guidance Material, https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/security/guidance/index.html (last visited Aug. 10, 2017).

[51] U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of Civil Rights, Understanding the Importance of Audit Controls (Jan. 2017), https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/january-2017-cyber-newsletter.pdf.

[52] U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of Civil Rights, Reporting and Monitoring Cyber Threats (Feb. 2017), https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/february-2017-ocr-cyber-awareness-newsletter.pdf.

[53] U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of Civil Rights, File Sharing and Cloud Computing: What to Consider? (June 2017), https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/june-2017-ocr-cyber-newsletter.pdf.

[54] See Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., First HIPAA enforcement action for lack of timely breach notification settles for $475,000 (Jan. 9, 2017), http://wayback.archive-it.org/3926/20170127111957/https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2017/01/09/first-hipaa-enforcement-action-lack-timely-breach-notification-settles-475000.html.

[55] See Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., $5.5 million HIPAA shines light on the importance of audit controls, Feb. 16, 2017), https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2017/02/16/hipaa-settlement-shines-light-on-the-importance-of-audit-controls.html.

[56] Id.

[57] See Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Lack of timely action risks security and costs money (Feb. 1, 2017), https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2017/02/01/lack-timely-action-risks-security-and-costs-money.html?language=es.

[58] See Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., $2.5 million settlement shows that not understanding HIPAA requirements creates risk (Apr. 24, 2017), https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2017/04/24/2-5-million-settlement-shows-not-understanding-hipaa-requirements-creates-risk.html?language=es.

[59] See Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Texas health system settles potential HIPAA disclosure violations (May 10, 2017), https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2017/05/10/texas-health-system-settles-potential-hipaa-disclosure-violations.html?language=es.

[60] 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b(b).

[61] 856 F.3d 1117 (7th Cir. 2017).

[62] Id. at 1129–30.

[63] See id. at 1119–24.

[64] Id. at 1130 (internal quotation marks removed).

[65] See id.

[66] 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b(b)(1), (b)(2).

[67] See Bryan v. United States, 524 U.S. 184 (1998).

[68] No. 14-171-11, 2017 WL 2559092, at *1 (S.D. Tex. June 13, 2017).

[69] Id. at *5.

[70] See id. at *4.

[71] Id. at *5.

[72] See id. (discussing United States v. St. Junius, 739 F.3d 193, 210 (5th Cir. 2013)).

[73] See id. at *5.

[74] See id. at *6–7.

[75] Id. at *7.

[76] United States v. Addus HomeCare Corp., No. 13 CV 9059, 2017 WL 467673 (N.D. Ill. Feb. 3, 2017).

[77] Id. at *5.

[78] Id.

[79] Id. at *9-10.

[80] See United States ex rel. Graziosi v. Accretive Health, Inc., No. 13-CV-1194, 2017 WL 1079190, at *8 (N.D. Ill. Mar. 22, 2017).

[81] See id. at *2.

[82] See id. at *8.

[83] Id.

[84] See United States ex rel. Cairns v. D.S. Medical, L.L.C., No. 1:12CV00004 AGF, 2017 WL 1304947, at *3 (E.D. Mo. Apr. 7, 2017).

[85] Id. at *2.

[86] Id. at *3.

[87] United States v. Moshiri, 858 F.3d 1077, 1084 (7th Cir. June 5, 2017).

[88] Id.

[89] See id.

[90] Id.

[91] See U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of Inspector Gen., OIG Advisory Op. 17-01 (Mar. 3, 2017), https://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/docs/advisoryopinions/2017/AdvOpn17-01.pdf.

[92] Id. at 2.

[93] See id. at 3–4.

[94] Id. at 4.

[95] See id. at 5.

[96] Id. at 5–9

[97] Id. at 9.

[98] Id.

[99] U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of Inspector Gen., OIG Advisory Op. 17-02 at 1 (June 29, 2017), https://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/docs/advisoryopinions/2017/AdvOpn17-02.pdf [hereinafter OIG Advisory Op. 17-02].

[100] Id. at 3.

[101] Id.

[102] Id. at 3–4.

[103] See id. at 4, 7.

[104] Id. at 4.

[105] 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7a(a)(5).

[106] See 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7a(i)(6)(A). As HHS OIG noted in the advisory opinion, the same exception to the definition of "remuneration" is found in the CMP statute’s implementing regulations. See OIG Advisory Op. 17-02, supra note 114, at 6 n.6; 42 C.F.R. § 1003.110.

[107] See OIG Advisory Op. 17-02, supra note 114, at 6–7.

[108] Id. at 7.

[109] 42 U.S.C. § 1395nn.

[110] Ctrs. for Medicare & Medicaid Servs., Self-Referral Disclosure Protocol, https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Fraud-and-Abuse/PhysicianSelfReferral/Self_Referral_Disclosure_Protocol.html (last visited Aug. 10, 2017).

[111] Ctrs. for Medicare & Medicaid Servs., Self-Referral Disclosure Protocol Settlements, https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Fraud-and-Abuse/PhysicianSelfReferral/Self-Referral-Disclosure-Protocol-Settlements.html (last visited Aug. 10, 2017).

[112] Health Care Industry Cybersecurity Task Force, Report on Improving Cybersecurity in the Health Care Industry (June 2017), https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/planning/CyberTF/Documents/report2017.pdf.

[113] United States ex rel. Emanuele v. Medicor Assocs., 2017 WL 1001581, at *17 (W.D. Pa. Mar. 15, 2017).

[114] Id. at *4-5.

[115] Id. at *6.

[116] Id. at *17.

[117] Id. at *18.

[118] Id.

[119] Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Missouri Hospitals Agree to Pay United States $34 Million to Settle Alleged False Claims Act Violations Arising from Improper Payments to Oncologists (May 18, 2017), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/missouri-hospitals-agree-pay-united-states-34-million-settle-alleged-false-claims-act.

[120] Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Los Angeles Hospital Agrees to Pay $42 Million to Settle Alleged False Claims Act Violations Arising from Improper Payments to Physicians (June 28, 2017), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/los-angeles-hospital-agrees-pay-42-million-settle-alleged-false-claims-act-violations-arising.

The following Gibson Dunn lawyers assisted in the preparation of this client update: Steve Payne, John Partridge, Jonathan Phillips, Coreen Mao, Laura Musselman, Reid Rector, Julie Schenker, Yamini Grema, Michael Dziuban and Stevie Pearl.

Gibson Dunn lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these developments. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work or any of the following:

Washington, D.C.

Stephen C. Payne, Co-Chair, FDA and Health Care Practice Group (202-887-3693, [email protected])

F. Joseph Warin (202-887-3609, [email protected])

Marian J. Lee (202-887-3732, [email protected])

Daniel P. Chung (202-887-3729, [email protected])

Jonathan M. Phillips (202-887-3546, [email protected])

Los Angeles

Debra Wong Yang (213-229-7472, [email protected])

San Francisco

Charles J. Stevens (415-393-8391, [email protected])

Winston Y. Chan (415-393-8362, [email protected])

Orange County

Nicola T. Hanna (949-451-4270, [email protected])

New York

Alexander H. Southwell (212-351-3981, [email protected])

Denver

Robert C. Blume (303-298-5758, [email protected])

John D.W. Partridge (303-298-5931, [email protected])

© 2017 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.