March 10, 2016

The Enforcement Office of the U.S Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) attracted frequent headlines in 2015, which saw an expansion in the scope of industries targeted and the level of penalties imposed. In this Client Alert, we closely examine the CFPB’s enforcement approach under Director Richard Cordray. Part I of this Alert gives an overview of the CFPB’s enforcement authority under the Dodd-Frank Act. Part II includes a discussion of the principal areas of CFPB enforcement in 2014 and 2015. Part III describes how in 2015 the CFPB made use of its authority under Section 1031 of the Dodd-Frank Act to take action against "unfair, deceptive and abusive acts and practices" (UDAAP). Part IV discusses the CFPB’s practices with respect to its press releases when it settles enforcement actions, which has been an area of industry concern. Part V discusses the future of CFPB enforcement, including the recent stance the CFPB has taken in 2016 with respect to the protection of customer data, i.e., cybersecurity. For ease of reference, hyperlinks to each Part of the Alert are provided below.

I. THE CFPB’S ENFORCEMENT AUTHORITY UNDER DODD-FRANK

II. INVESTIGATIONS AND ENFORCEMENT ACTIONS IN 2014 AND 2015

IV. CFPB ENFORCEMENT PRESS RELEASES

I. THE CFPB’S ENFORCEMENT AUTHORITY UNDER DODD-FRANK

The creation of a new federal regulator charged with the interpretation and enforcement of federal consumer law, separate and independent from the federal banking agencies, was a cornerstone of the Dodd-Frank Act. As a result, the Dodd-Frank Act grants the CFPB extremely broad enforcement authority.

The CFPB is an "independent bureau" in the Federal Reserve System and, as such, is not subject to congressional appropriations. Rather, each year it receives a certain percentage of the annual earnings of the Federal Reserve System. For fiscal year 2015, the CFPB’s budget outlays were $524.4 million.[1] Subtitle E of Title X of the Dodd-Frank Act establishes the CFPB’s enforcement authority, which includes the authority to:

- Conduct administrative adjudication proceedings "with respect to any person" to enforce compliance with –

- the consumer protection provisions of Dodd-Frank, including any rules prescribed by the CFPB; and

- "[a]ny other Federal law" that the CFPB is authorized to enforce, and any regulations or order prescribed thereunder, "unless such Federal law specifically limits the [CFPB] from conducting" an adjudication proceeding, "and only to the extent of such limitation";[2] and

- Commence a civil action in a U.S. district court or in any state court of competent jurisdiction in a district in which the defendant is located or resides or is doing business, against "any person" who violates a federal consumer financial law, to impose a civil penalty and obtain all appropriate legal and equitable relief.[3]

Title X does exclude certain entities from this authority, including depository institutions with $10 billion or fewer in assets, nonfinancial businesses (except to the extent they offer a consumer financial product or service), real estate brokers, auto dealers, and persons subject to securities, insurance and commodities regulation.[4] These exclusions, however, do leave a wide range of parties who may become subject to CFPB enforcement; in addition, the number of "federal consumer financial laws" that the CFPB has the authority to enforce is very large. As will be seen, CFPB enforcement is not always exclusive; state attorneys general and the Justice Department may also be involved in CFPB actions, as well as bank regulators and other government agencies.

II. INVESTIGATIONS AND ENFORCEMENT ACTIONS IN 2014 AND 2015

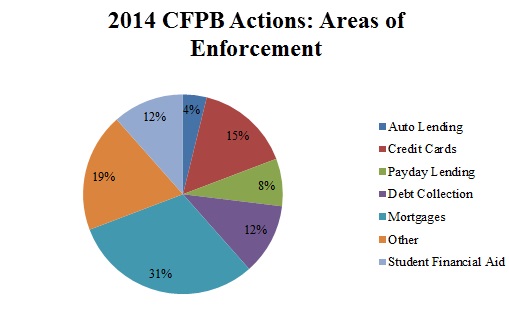

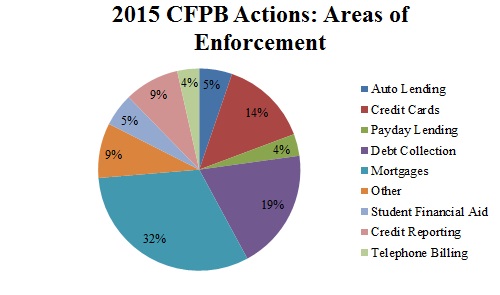

In 2014, the CFPB focused its enforcement powers on principally the following industries: credit cards, residential mortgages, payday lending, student loans, and debt collection. Such industries continued to be subject to CFPB enforcement in 2015, but the CFPB added to them, taking significant actions against indirect auto lenders, credit reporting companies, a mid-sized depository institution for alleged "redlining," and telephone companies with respect to their payment processing services.

Credit Cards – 2014 Enforcement Activity

The focus of CFPB credit card enforcement in 2014 was "add on" products. In April, the CFPB settled an administrative proceeding with Bank of America, N.A. and its affiliate FIA Card Services, N.A. for allegedly charging consumers for credit monitoring and credit reporting services that those customers did not receive and engaging in deceptive marketing tactics associated with these and other products.[5] Bank of America agreed to pay $459 million to the approximately 1.5 million customers who were allegedly charged for services they never received and $268 million to the approximately 1.4 million customers allegedly affected by the marketing practices, plus a $20 million penalty to the CFPB’s civil penalty fund.[6] The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), Bank of America’s primary federal bank regulator, ordered Bank of America to pay an additional $25 million civil money penalty, as certain of the practices predated the creation of the CFPB – resulting in a total payout of $772 million.

Two months later, the CFPB entered into a similar consent order with Synchrony Bank for allegedly deceptive marketing practices and allegedly discriminatory practices.[7] The order claimed that, among other things, that Synchrony misleadingly marketed five debt cancellation add-on products to certain cardholders without adequately informing them that they were purchasing the products, and misrepresented the products’ costs, terms and benefits. In addition, the CFPB claimed that the bank had excluded certain borrowers on the basis of their "Spanish preferred" indicators or addresses in Puerto Rico, in violation of the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA). The consent order required $225 million in total relief – $56 million to approximately 638,000 customers for the marketing practices, and $169 million to approximately 108,000 borrowers excluded for the alleged ECOA violations. Synchrony was also required to pay $3.5 million to the civil penalty fund.

Credit Cards – 2015 Enforcement Activity

A focus on add-on products contained in 2015, but the CFPB also took action with respect to allegedly improper debt collection practices. The most significant settlement was a July administrative consent order with Citibank, N.A. and its affiliates Department Stores National Bank and Citicorp Credit Services, Inc. (USA) for engaging in allegedly unfair billing and deceptive marketing and collection practices related to add-on credit monitoring and credit reporting services. Citibank agreed to pay $700 million to the approximately 8.8 million customers who were alleged to have been charged for services they never received, plus a $35 million penalty to the civil penalty fund. Commenting on the action, Director Cordray stated, "[i]n our four years, this is the tenth action we’ve taken against companies in this space for deceiving consumers. We will remain on the lookout for similar conduct and will address it as we find it."[8]

The CFPB also settled a significant action against a credit card bank subsidiary of JPMorgan Chase & Co. and one of its affiliates (Chase) for practices related to consumers’ defaulted credit card debts from 2009 to 2013.[9] The CFPB alleged that Chase had failed to maintain and update its own databases and, as a result, when it sold defaulted consumer accounts to buyers for collection, those accounts were inaccurate, with many debts settled, discharged in bankruptcy, not owed, or otherwise not collectable. The CFPB also claimed that Chase filed lawsuits with deceptive sworn documents, made miscalculations and errors that resulted in judgments against consumers for incorrect amounts, and provided substantial assistance to debt buyers’ deceptive collection practices.[10] Chase agreed to overhaul its applicable policies and procedures, and to pay at least $50 million in consumer refunds, as well as $136 million in penalties and payments to the CFPB and certain states that joined the CFPB action. The OCC assessed an additional $30 million civil penalty in a related action.

Mortgages – 2014 Enforcement Authority

Given the lack of overarching federal supervision before the Financial Crisis, the mortgage industry was a second principal target of CFPB enforcement. The CFPB’s most significant action was a settlement with SunTrust Mortgage (SunTrust). In the investigation, the CFPB, Department of Justice (DOJ ), Department of Housing and Urban Development and certain state attorneys general alleged that SunTrust had engaged in mortgage servicing misconduct in failing to apply borrower payments promptly and accurately and by charging unauthorized fees for default-related services, failing to provide accurate information about loan modification and loss-mitigation services, improperly processing applications to calculate eligibility for such services, and providing false and misleading reasons for denying loan modifications. Under the settlement, SunTrust agreed to pay at least $500 million in loss mitigation relief to underwater borrowers, $40 million to approximately 48,000 consumers who lost their homes to foreclosure, and $10 million to the federal government. The DOJ also ordered SunTrust to pay a $418 million penalty.[11]

A second area of CFPB focus was the Loan Originator Compensation Rule, which prohibits companies from giving employees incentives to steer consumers into higher-priced mortgages, a much-criticized practice in the years before the Financial Crisis. In November 2014, the CFPB settled a federal court action with Franklin Loan Corporation (Franklin), alleging that Franklin gave its employees "bonuses for steering consumers into loans with higher interest rates," and that those practices "affected more than 1,400 borrowers." Franklin agreed to cease these practices and to also pay compensation to the consumers affected.[12]

Mortgages – 2015 Enforcement Authority

The most significant 2015 mortgage-related case is that of PHH Corporation ("PHH"). In it, the CFPB initiated an administrative action, alleging violations of the Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act of 1974 (RESPA); the CFPB claimed that PHH had initiated mortgages and referred homebuyers to mortgage insurers with whom it had agreements to buy reinsurance from PHH’s affiliates. To the CFPB, this practice was prohibited by RESPA.[13]

PHH litigated the administrative action, and the CFPB’s administrative law judge (ALJ), who had been borrowed from the Securities and Exchange Commission, stated that PHH had violated RESPA and recommended imposition of an injunction and disgorgement of $6.4 million. Under the appeals procedure provided for under the Dodd-Frank Act and the CFPB’s regulations,[14] PHH appealed that decision to Director Cordray. Cordray upheld the ALJ’s finding of a RESPA violation, but overturned the decision on disgorgement. Stating that there was a separate RESPA violation every time PHH accepted a reinsurance premium, Cordray’s action required PHH to pay more than $109 million in disgorgement – over 17 times as much as recommended by the ALJ.[15]

PHH filed a petition for review of Director Cordray’s action in the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, alleging that the order was arbitrary, capricious, and an abuse of discretion, and violated federal law and the U.S. Constitution. PHH argued, inter alia, that it had been deprived of fair notice because Director Cordray had departed from well-established interpretations of RESPA in making his decision, and that his interpretation of RESPA conflicted with the statute’s text and would undermine its purposes.[16] The D.C. Circuit stayed Director Cordray’s action and will hear the case later this year.

A second 2015 action also involved RESPA’s anti-kickback provisions. In January, the CFPB and the Maryland Attorney General filed a complaint against Wells Fargo and JPMorgan Chase for allegedly engaging in an illegal-marketing kickback scheme with a title company, Genuine Title.[17] The CFPB claimed that more than one hundred Wells Fargo loan officers in at least eighteen branches across Maryland and Virginia referred loans to Genuine Title in return for cash payments and the provision of consumer information. The CFPB also alleged that at least six JPMorgan Chase loan officers participated in the scheme, and that both Wells Fargo and JP Morgan Chase did not have adequate systems in place to ensure that their officers were following the law. Wells Fargo settled the action and agreed to pay $24 million in civil penalties and $10 million in redress to affected customers; JPMorgan Chase, in its settlement, agreed to pay $600,000 in civil penalties and $300,000 in redress.[18]

In April, the CFPB and Federal Trade Commission (FTC) took joint action against Green Tree Servicing, LLC (Green Tree), a national mortgage servicing company, for allegedly engaging in illegal practices when servicing mortgage loans. It was claimed that Green Tree failed to honor loan modifications that customers had already entered, demanded payments before providing loss mitigation options, and used illegal practices like making false threats, harassing consumers by phone, and revealing debts to third parties in order to collect mortgage payments.[19] Green Tree agreed to pay $48 million in restitution to victims and $15 million in civil penalties.[20]

Finally, Loan Originator Compensation Rule violations continued to be an issue, as in June 2015, the CFPB filed a complaint against RPM Mortgage, Inc. (RPM) and RPM’s chief executive officer for paying bonuses and higher commissions to loan originators as incentives for steering consumers into mortgages with higher interest rates.[21] RPM agreed to pay $18 million in redress to consumers and $1 million in civil penalties, and its chief executive officer agreed to pay $1 million to the civil penalty fund.[22]

Payday Lending – 2014 Enforcement Activity

A payday loan is a short-term cash or check advance for a small amount, usually $500 or less, typically due on a borrower’s next payday. Although these loans are intended to be short-term advances, many borrowers seem to end up in repeated cycles of borrowing where the interest costs become very significant, an effect that has drawn the CFPB’s attention as it prepares to promulgate rules for larger participants in the industry later this year. Other practices by payday lenders, however, have already led to enforcement actions.

In July 2014, the CFPB brought an enforcement action against ACE Cash Express (ACE) for allegedly using "illegal debt collection tactics – including harassment and false threats of lawsuits or criminal prosecution – to pressure overdue borrowers into taking out additional loans that they could not afford." Specifically, the CFPB claimed that ACE made threats to customers of bringing a lawsuit or charging extra fees if the borrower did not "temporarily pay off their loans then quickly re-borrow from ACE." ACE agreed to payments of $5 million in consumer redress and a $5 million civil penalty.[23] In September, the CFPB brought an action against the Hydra Group for using "information bought from online lead generators to access consumers’ checking accounts to illegally deposit payday loans and withdraw fees without consent,"[24] collecting $115.4 million from consumers over a 15-month period. The United States District Court for the Western District of Missouri granted the CFPB’s request for a temporary restraining order, freezing the defendants’ assets, and installing a receiver to oversee the business.[25]

Payday Lending – 2015 Enforcement Activity

In 2015, the CFPB focused its attention on an offshore payday lender, bringing an action in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York against NDG Financial Corporation (NDG) and its commonly controlled companies.[26] The CFPB alleged that through a network of foreign companies organized in Canada and Malta, NDG offered United States residents short-term loans containing excessive transactional and late penalty fees, with terms averaging 14 days and fees of $19.98 to $26.98 per $100 borrowed. The CFPB argued that the loans were void from inception under state usury and licensed lender laws, given the loans’ extremely high interest rates (APRs as much as 599.12%) and the fact that NDG was not licensed as required by state law. In December, the CFPB entered into a consent order with another payday lender, EZCORP, with respect to allegedly illegal debt collection practices. EZCORP agreed to make $7.5 million in payments to consumers harmed by its practices and pay a $3 million civil money penalty.

Student Loans – 2014 Enforcement Activity

The CFPB has conducted inquiries and produced reports over the past few years on the affordability of private student loans, claiming that, unlike federal loans, many private loans do not provide students with affordable payment options or refinancing opportunities.[27] It has also kept a close watch on the private student loan industry as an enforcement matter.

In February 2014, the CFPB filed its first lawsuit against a company in the for-profit college industry, ITT Educational Services, Inc. (ITT), which operates schools offering post-secondary technical education. The CFPB argued that ITT encouraged its students to enter into high-cost private loans on which they were likely to default and sought restitution for the affected students, a civil fine, and an injunction. According to the CFPB’s complaint, ITT provided certain of its students one-year zero-interest loans, knowing that many students would not be able to repay the loan by the end of the year and would need to seek outside funding.[28] In March 2015, the United States District Court for the Southern District of Indiana partially denied ITT’s motion to dismiss, but granted the motion with respect to the CFPB’s claim (truth in lending) that exposed ITT to the most significant financial liability. ITT has appealed the partial denial of its motion to dismiss.

Student Loans – 2015 Enforcement Activity

This focus on high-interest student loans continued in 2015, when the CFPB brought an enforcement action in federal court against Corinthian Colleges, Inc. (Corinthian). The CFPB’s complaint alleged that Corinthian used false job prospects and career counseling to lure students into taking out high interest loans to cover tuition costs.[29] To remedy these violations, the court ordered Corinthian to pay more than $530 million; however, earlier in the year, Corinthian had filed for bankruptcy and was later dissolved. In an effort to provide relief, the CFPB and the ECMC Group, the new owner of many Corinthian schools, in collaboration with the U.S. Department of Education, announced in February 2015 that they had secured $480 million in loan forgiveness.[30]

Debt Collection – 2014 Enforcement Activity

High-pressure debt collection efforts were a focus of CFPB activity in 2014. For example, in its consent order with DriveTime Automotive Group, Inc. and DT Acceptance Corp., the CFPB alleged that the companies had their collectors call consumers at work, even though those consumers had requested not to receive such calls, with one consumer being fired because of receipt of multiple such calls. It was also claimed that the companies called third-party references the customers had provided in order to collect. The companies agreed to overhaul these practices and pay $8 million to the civil penalty fund.[31]

Debt Collection – 2015 Enforcement Activity

2015 saw a continued focus by the CFPB on such practices. The best example of the CFPB’s approach was a September consent order with Encore Capital Group (Encore), the nation’s largest debt buyer and collector, which had purchased the rights to collect defaulted consumer debt relating to credit cards, phone bills, and other accounts. The CFPB alleged that Encore bought debts that were potentially inaccurate, lacking documentation, or unenforceable, and, without verifying the debt, collected payments by pressuring consumers with false statements and churning out lawsuits using robo-signed court documents, practices that violated the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act.[32]

In its consent order, Encore agreed to overhaul its debt collection and litigation practices and to stop reselling debts to third parties, to pay up to $42 million in consumer refunds and a $10 million civil penalty, and to stop collection on over $125 million worth of debts.[33]

New Areas of Focus – Indirect Auto Lending, "Redlining," and Telecommunications Payments

Debt collection falls squarely within an area where the CFPB has jurisdiction under the Dodd-Frank Act. A more controversial area, however, relates to certain automobile lending practices that the CFPB has claimed have had discriminatory effects. As part of the legislative compromise that produced Title X of the Dodd-Frank Act, auto dealers were broadly excluded from CFPB jurisdiction.[34] Given the statutory exclusion, the CFPB has not proceeded against auto dealers in fact; but this has not prevented the CFPB from successfully seeking to reshape industry practices that it views as discriminatory.

The first 2015 consent order in the auto lending area was with American Honda Finance Corporation (Honda Finance), a nonbank finance company, in July.[35] In this action, the CFPB targeted so-called "indirect auto lending." In an indirect lending transaction, the lender sets an interest rate, or "buy rate," that it conveys to auto dealers; this rate is based on the risk of the loan as determined by the lender. The lender then permits, as dealer compensation, the dealer to charge a higher interest rate when the deal with the consumer is finalized – the additional interest rate is referred to as "dealer markup." Honda Finance permitted dealers to mark-up consumers’ interest rates as much as 2.25 percent for contracts with terms of 5 years or less, and 2 percent for contracts with longer terms. The markups, unlike the "buy rates," were not based on loan risk.

The Honda Finance action resulted from a joint CFPB and DOJ investigation that began in April 2013. The CFPB and DOJ alleged that Honda Finance’s policies resulted in minority borrowers paying higher dealer markups in violation of ECOA – the CFPB claimed that thousands of minority borrowers from January 2011 through July 14, 2015 paid, on average, from $150 to over $250 more for their auto loans. The CFPB and DOJ proceeded on a theory of disparate impact; there was not an allegation of intentional discrimination by Honda Finance.

In settling the action, Honda Finance agreed to: (i) substantially reduce or eliminate entirely dealer discretion (the maximum mark-up would be only 1.25 percent above the buy rate for auto loans with terms of 5 years or less, and 1 percent for auto loans with longer terms.);[36] (ii) pay $24 million to a settlement fund that will go to affected African-American, Hispanic, and Asian and Pacific Islander borrowers whose auto loans were financed by Honda between January 2011 and July 14, 2015; and (iii) administer and distribute the settlement funds to the affected borrowers. The CFPB stated that it did not assess penalties against Honda because of the proactive steps the company was taking to substantially reduce or eliminate dealer discretion.[37]

In September, the CFPB entered into a similar order with Fifth Third Bank, in which the bank agreed to limit or eliminate dealer discretion and contribute to a settlement fund for affected borrowers; like the Honda Finance action, no civil money penalty was imposed.[38]

* * * * *

ECOA claims formed the basis of a more classic discrimination claim – alleged redlining – in the CFPB’s September 2015 settlement with Hudson City Savings Bank (Hudson City), a thrift that had agreed to be acquired by M&T Bank Corporation. The CFPB alleged that Hudson City had structured its residential mortgage lending business in order to avoid lending in majority-Black and majority-Hispanic neighborhoods. This was a claim that, prior to Dodd-Frank, would have been within the jurisdiction of the federal bank regulators to enforce. At over $10 billion in assets, however, Hudson City was no longer subject to prudential bank regulatory authority in the area. In settling the action, Hudson City agreed to make over $27 million in payments to affected communities, and to pay a civil money penalty of over $5 million.

* * * * *

Like auto dealers, telecommunications companies seem distinct from financial firms. Aspects of a telecommunications business, however, do involve consumer payment processing, a "consumer financial product or service" within the meaning of the Dodd-Frank Act. As a result, the CFPB has jurisdiction over this part of the telecommunications business, and in May 2015, the CFPB settled federal court actions against Verizon Wireless and Sprint.[39]

Working with the FCC and certain state attorneys general, the CFPB claimed that the telecommunications companies "unfairly charged [their] customers by creating a billing and payment processing system that gave third parties virtually unfettered access across [their] customers’ accounts."[40] The CFPB further alleged that both companies automatically enrolled their customers in third-party billing systems, by which they outsourced payment processing for digital purchases of premium text messages or premium short messaging services, without customers’ knowledge or consent; failed to properly monitor third-party payment processors that improperly imposed those charges; continued to operate the flawed systems despite evidence that customers were being overcharged; and profited from the systems by shifting the risks to customers in their account terms and conditions.

In settling the actions, Sprint agreed to pay up to $50 million in redress to injured customers, and Verizon agreed to pay up to $70 million. The companies also agreed to pay $38 million in federal and state fines and to institute reforms to their payment processing systems.[41]

Nor has the CFPB’s interest in the financial aspects of nonfinancial companies’ business been limited to the telecommunications sector. In June 2015, the CFPB sent letters to the nation’s largest search engine and social networking companies to advise them of a practice by which scammers might be using their search and advertising platforms to target student loan borrowers with aggressive and misleading advertisements.[42] The CFPB advised the companies to work closely with federal and state agencies to ensure that their services are not used to target student loan borrowers. Since it is expected that CFPB will continue, in the near term, to focus on the student loan industry, this may not be the last CFPB interaction with such nonfinancial companies.

III. UDAAP AUTHORITY

2015 also saw the CFPB make great use of its so-called UDAAP authority set forth in Section 1031 of the Dodd-Frank Act. Borrowed from the Federal Trade Commission statute, but amplified to include "abusive" acts and practices in addition to "unfair" and "deceptive" ones, Section 1031 grants the CFPB a powerful weapon in its enforcement cases.

Under the statute, an "unfair" act or practice is one that "causes or is likely to cause substantial injury to consumers," and "the injury is not reasonably avoidable by consumers; and . . . is not outweighed by countervailing benefits to consumers or to competition."[43] An act or practice is deceptive when the act or practice misleads or is likely to mislead the consumer, is material, and the consumer’s interpretation of the act or practice is reasonable under the circumstances.

An act or practice is "abusive" when it materially interferes with the ability of a consumer to understand a term or condition of a consumer financial product or service, or when it takes unreasonable advantage of: (i) a consumer’s lack of understanding of the material risks, costs, or conditions of the product or service; (ii) a consumer’s inability to protect his or her interests in selecting or using a consumer financial product or service; or (iii) a consumer’s reasonable reliance on a person subject to CFPB jurisdiction to act in the consumer’s interests.[44]

"Deceptive" acts and practices are perhaps the most identifiable UDAAPs, with the CFPB alleging such 2015 examples as:

- failing to inform consumers that a "no-interest" loan became a loan with a 22.98% APR if the balance was not paid before the end of the promotional period;

- making misrepresentations about the payment and other terms of loans subject to modifications;

- misrepresenting time-barred debt as still being owed;

- stating an intent to prove a debt as being owed if the consumer chose to contest the debt in court, when the company had no such intent;

- misrepresenting the amount of mortgage interest saved under an "equity accelerator" program;

- using a third-party service that masked phone numbers to deceive car borrowers to disclose their locations when a company sought to collect their debts; and

- statements that overdraft fees would not be charged on certain bank transactions when they were charged.

"Unfair" acts and practices, by contrast, require the CFPB to make judgments about consumer injury and a lack of a compensating benefit. Examples of allegedly unfair practices in 2015 include:

- a mortgage servicer that refused to honor in-process loan modifications agreed to by servicers from whom it acquired the mortgage loans unless the modifications met its own standards;

- a bank that undercredited certain customers on their deposits because it did not verify the actual amount deposited when there was a discrepancy between the deposit ticket and the check, and the amount deposited was $25.00 or less (certain bank customers were overcredited by the practice);

- a debt collector that made excessive collection calls at inconvenient times;

- a company’s directing consumers’ payments to be made via a line of credit product rather than a bank account debit without the consumers’ authorization; and

- companies’ creating a third-party payment processing system that allowed for large numbers of improper charges to be imposed on customers’ accounts.

The Verizon Wireless/Sprint action is telling because the UDAAP was the only violation of federal financial consumer law with which the parties were charged, and Verizon Wireless and Sprint are telecommunications companies. Nonetheless, an allegedly "unfair" act or practice led to a significant monetary settlement.[45]

As for allegedly "abusive" practices, they included a company’s obscuring the true nature of a transaction as a usurious loan by calling the product a "pension buyout" or "money purchase pension plan" and stating that the product was preferable to a home-equity loan or credit card borrowing, and a company’s providing insufficient information to consumers about how their payments would be allocated among multiple loan balances and operating a customer-service department that either provided misinformation or allocated payments differently than requested by the consumer.

Certain acts and practices, moreover, can fit more than one UDAAP category. In the case of an offshore unregistered payday lender, that company’s practice of telling consumers they owed money on the loans was "deceptive" because the loans were void from inception for having been made without a license, but it was also "unfair" because consumers would not have knowledge of the state licensing laws, and it was also "abusive" because the statements materially interfered with consumers’ ability to understand the void nature of the loans.[46]

It is clear from the CFPB’s 2015 actions, therefore, that the CFPB will make use of its UDAAP authority in a wide range of circumstances and across a wide range of industries.

IV. CFPB ENFORCEMENT PRESS RELEASES

When a company agrees to settle a dispute with the CFPB through a consent order, the CFPB generally releases a corresponding press release. Firms investigated by the CFPB have complained about improper characterization of alleged wrongdoing in the press releases. When a press release does not track the language in an agreed upon consent order, the risk is that the release and the characterization of the consent order in the press may then assist other government agencies or plaintiffs’ attorneys when they pursue separate actions against the target company.

The CFPB’s mischaracterization of consent orders in its press releases has been a concern since 2013. For example, in October 2013, the CFPB entered into consent orders with two mortgage lenders, Mortgage Master and Washington Federal, after claiming it had found numerous data errors in the firms’ mortgage applications. After the CFPB issued a press release regarding the consent order, Washington Federal released its own statement, saying "We agreed to a consent order because we did not believe that the technical issues involved or the small penalty justified litigation. We are, however, disappointed with the harshness of the language in the CFPB’s press release, which in our view is not consistent with prior discussions, including their repeated statements to us that the order is the equivalent of a traffic ticket."[47]

Later that year, in December 2013, in a consent order entered into with Ally Financial, the CFPB’s press release headline was, "CFPB and DOJ Order Ally to Pay $80 Million to Consumers Harmed by Discriminatory Auto Loan Pricing: Ally to Pay Additional $18 Million in Civil Penalties for Harming More Than 235,000 Minority Borrowers." But the consent order entered into by Ally did not go so far. The consent order did not say that Ally Financial specifically "harmed" minority buyers but simply that Ally Financial’s auto lending practices resulted in "statistically significant" disparities between what white and nonwhite car buyers were charged in dealer markups on interest rates.[48] In response to the CFPB’s press release, Ally Financial released a statement in response, clarifying its alleged wrongdoing.

Then in 2014, the CFPB’s press release following its consent order with First Investors Financial Services Group Inc. (First Investors), contained the headline, "CFPB Takes Action against Auto Finance Company for Distorting Borrower Credit Reports," and went on to characterize First Investors as "an auto finance company that distorted consumer credit records for years." The consent order, however, said nothing about purposeful distortion, merely stating that First Investors was responsible for a vendor’s inaccurate reporting of information due to a computer problem, which continued after First Investors knew of this problem.[49]

In November 2014, CFPB Ombudsman Wendy Kamenshine agreed to "conduct an independent review of consent orders and their corresponding CFPB press releases" in 2015. The results of Kamenshine’s review were first published by the CFPB in its July 2015 Mid-Year Update.[50] In a single paragraph, Kamenshine’s concluded that "CFPB press releases generally do reflect the language in the consent orders."[51] Kamenshine cautioned, however, that as the CFPB develops press releases in the future, it should consider whether "press releases contain words with legal meaning that are not in consent orders in an effort to use plain language, and whether phrasing exists that may make certain topics seem more significant than they otherwise might."[52]

It was hoped that Kamenshine’s review would result in findings that would deter the CFPB from issuing misleading press releases following the issuance of a consent order. But despite Kamenshine’s findings in the Mid-Year Update and the CFPB’s knowledge that an independent review of its press releases was ongoing, when Kamenshine updated her findings for the CFPB’s 2015 Annual Report to the Director, she noted that a review from May to September 2015 still showed examples of misleading language in CFPB releases.[53]

Companies subject to the CFPB’s jurisdiction therefore should continue to be vigilant on this score. Before entering a consent order with the CFPB, companies should seek to negotiate the CFPB’s characterization of the consent order to ensure that the press release does not imply guilt or wrong-doing beyond that which the company has agreed to in the consent order, and bear in mind the timing of the release in order to have an effective public response available if one becomes necessary.

V. 2016 AND BEYOND

In 2016, we expect the CFPB to continue on the path it has followed over the last two years. For example, on March 2, 2016, the CFPB entered into a $100,000 settlement agreement with Dwolla, Inc., an Iowa-based online payment platform, based on the CFPB’s findings of providing inadequate customer data security.[54] In addition to the penalty, Dwolla agreed to develop, implement, and enact numerous additional data security measures subject to review and approval by the CFPB.[55] The CFPB sought and obtained the settlement with Dwolla without making any finding of a security breach, but rather relied on its UDAAP authority: that is, Dwolla had represented to its customers that it provided a certain level of data security, when, according to the CFPB, it did not.[56] The press release accompanying the settlement made no reference to whether any customer information had been compromised.[57]

Firms that operate in the areas that have drawn CFPB attention to date – credit cards, mortgage lending, payday lending, student lending, and debt collection – should not expect a let up in 2016. In addition, the Verizon Wireless, Sprint, and indirect auto lending settlements demonstrate that the financial aspects of a commercial business are not immune from CFPB investigations and enforcement. Finally, the CFPB anticipates budget outlays of over $600 million this year, up almost 15% from 2015.[58]

Beyond the immediate term – and here, the term is truly immediate – the future of the CFPB will ultimately depend on the 2016 elections. Under legislation proposed in 2015 by Republican Senator Richard Shelby, the CFPB would become a five-member agency, like the SEC, CFTC and FDIC, and it would become subject to the appropriations process. Whatever else may be said of such changes, they would likely operate as a braking mechanism against the further expansion of the CFPB’s enforcement authority. Having been granted extraordinary enforcement authority by statute, and having pushed the limits of that authority in its first years of existence, it is still unclear where the CFPB will ultimately end up.

[1] CFPB Strategic Plan, Budget, and Performance Plan and Report (2015), at 11.

[4] See, e.g., id. §§ 5516, 5517, 5519.

[5] CFPB Consent Order, In the Matter of Bank of America, N.A.; and FIA Card Services, N.A (Apr. 9, 2014), available at http://www.consumerfinance.gov/f/201404_cfpb_bankofamerica_consent-order.pdf.

[6] Under the Dodd-Frank Act, amounts in the civil penalty fund may be used by the CFPB to make payments to "the victims of activities for which civil penalties have been imposed." 12 U.S.C. § 5497(d). "To the extent that such victims cannot be located or such payments are otherwise not practicable," id., the CFPB may use such funds for the purpose of consumer education and financial literacy programs.

[7] CFPB Consent Order, In the Matter of Synchrony Bank, f/k/a GE Capital Retail Bank (Jun. 19, 2014), available at http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201406_cfpb_consent-order_synchrony-bank.pdf.

[8] CFPB Press Release, CFPB Orders Citibank to Pay $700 Million in Consumer Relief for Illegal Credit Card Practices (July 21, 2015), available at http://www.consumerfinance.gov/newsroom/cfpb-orders-citibank-to-pay-700-million-in-consumer-relief-for-illegal-credit-card-practices/.

[9] CFPB Press Release, CFPB, 47 States and D.C. Take Action Against JPMorgan Chase for Selling Bad Credit Card Debt and Robo-Signing Court Documents (July 8, 2015), available at http://www.consumerfinance.gov/newsroom/cfpb-47-states-and-d-c-take-action-against-jpmorgan-chase-for-selling-bad-credit-card-debt-and-robo-signing-court-documents/.

[10] CFPB Consent Order, In the Matter of Chase Bank, USA N.A. and Chase Bankcard Services, Inc. (July 8, 2015), available at http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201507_cfpb_consent-order-chase-bank-usa-na-and-chase-bankcard-services-inc.pdf.

[11] CFPB Proposed Consent Judgment, United States of America et al. v. Suntrust Mortgage, Inc. No. 14-1028 (RMC) ( (D.D.C. Jun. 17, 2014), available at http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201406_cfpb_consent-judgement_sun-trust.pdf.

[12] CFPB Stipulated Final Judgment and Order, CFPB v. Franklin Loan Corp., No. 5:14-cv-02324-JGB (C.D. Cal. Nov. 26, 2014), available at http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201411_cfpb_stipulated-final-judgment-and-order_franklin-loan.pdf.

[13] CFPB Press Release, CPPB, CFPB Takes Action Against PHH Corporation for Mortgage Insurance Kickbacks (Jan. 24, 2014), available at http://www.consumerfinance.gov/newsroom/cfpb-takes-action-against-phh-corporation-for-mortgage-insurance-kickbacks/.

[15] CFPB Decision of the Director, In the Matter of PHH Corporation, PHH Mortgage Corporation, PHH Home Loans LLC, Atrium Insurance Corporation, and Atrium Reinsurance Corporation (June 4, 2015), available at http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201506_cfpb_decision-by-director-cordray-redacted-226.pdf.

[16] Brief for Petitioner at 46, PHH Corp., et al. v. CFPB, No. 15-1177 (CADC, Dec. 11, 2015). On the constitutional issue, PHH noted that, under Dodd-Frank, Director Cordray is removable only for cause during his five-year term, is able to fund the CFPB without regard to the Congressional appropriations process, and is not part of a multi-member commission structure – "Never before has so much power been accumulated in the hands of one individual so thoroughly shielded from democratic accountability." Id.

[17] Complaint, CFPB v. Wells Fargo Bank, N.A., JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A., Elaine Oliphant Cohen, and Todd Cohen, No. 1:15-cv-00179-RDB (Dist. Ct. Md. Jan. 22, 2015) available at http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201501_cfpb_complaint_wells-fargo-chase-cohen.pdf.

[18] See CFPB Stipulated Final Judgment and Order, CFPB v. Wells Fargo Bank, N.A., JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A., Elaine Oliphant Cohen, and Todd Cohen, No. 1:15-cv-00179-RDB (D. Md. Jan. 22, 2015), available at http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201501_cfpb_stamped-exhibit-a-wells-consent-judgment-document-4-1.pdf; CFPB Stipulated Final Judgment and Order, CFPB v. Wells Fargo Bank, N.A., JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A., Elaine Oliphant Cohen, and Todd Cohen, No. 1:15-cv-00179-RDB (Dist. Ct. Md. Jan. 22, 2015), available at http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201501_cfpb_stamped-exhibit-a-jpmorgan-consent-judgment-document-3-1.pdf.

[19] CFPB Press Release, CFPB and Federal Trade Commission Take Action Against Green Tree Servicing for Mistreating Borrowers Trying to Save Their Homes (Apr. 21, 2015), available at http://www.consumerfinance.gov/newsroom/cfpb-and-federal-trade-commission-take-action-against-green-tree-servicing-for-mistreating-borrowers-trying-to-save-their-homes/.

[20] FTC and CFPB Stipulated Order for Permanent Injunction and Monetary Judgment, Federal Trade Commission and Consumer Financial Protection Bureau v. Green Tree Servicing LLC, No. 0:15-cv-02064 (D. Minn. Apr. 21, 2015), available at http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201504_cfpb_proposed-consent-order-green-tree.pdf.

[21] Complaint, CFPB v. RPM Mortgage, Inc. and Erwin Robert Hirt, No. 4:15-cv-02475 (N.D. Cal. June 4, 2015), available at http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201506_cfpb_complaint-for-permanent-injunction-and-other-relief-rpm-mortgage-inc-and-erwin-robert-hirt-individually.pdf.

[22] CFPB Stipulated Final Judgment and Order, CFPB v. RPM Mortgage, Inc. and Erwin Robert Hirt, Case No. 4:15-cv-02475 (N.D. Cal. June 4, 2015), available at http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201506_cfpb_stipulated-final-judgment-and-order-as-to-rpm-mortgage-inc-and-erwin-robert-hirt-individually-stamped.pdf.

[23] CFPB Press Release, CFPB Takes Action Against ACE Cash Express for Pushing Payday Borrowers Into Cycle of Debt (July 10, 2014), available at http://www.consumerfinance.gov/newsroom/cfpb-takes-action-against-ace-cash-express-for-pushing-payday-borrowers-into-cycle-of-debt/. See also CFPB Consent Order, In the Matter of ACE Cash Express, Inc. (Jul. 10, 2014), available at http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201407_cfpb_consent-order_ace-cash-express.pdf.

[24] CFPB Press Release, CFPB Sues Online Payday Lender for Cash-Grab Scam (Sept. 17, 2014), available at http://www.consumerfinance.gov/newsroom/cfpb-sues-online-payday-lender-for-cash-grab-scam/.

[25] CFPB v. Moseley et al., Case No. 4:14-cv-00789-DW (W.D. Mo. Sept. 8, 2014), available at http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201409_cfpb_complaint_hydra-group.pdf.

[26] CFPB v. NDG Financial Corp., Northway Financial Corp., Ltd., Northway Broker, Ltd., E-Care Contact Centers, Ltd., Blizzard Interactive Corp., Sagewood Holdings, Ltd., New World Consolidated Lending Corp., New World Lenders Corp., Payroll Loans First Lenders Corp., and New World RRSP Lenders Corp., Case No. 1:15-cv-05211-CM (July 31, 2015), available at http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201508_cfpb_complaint-northway.pdf.

[27] See e.g., Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Student Loan Affordability: Analysis of Public Input on Impact and Solutions (May 8, 2013), available at http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201305_cfpb_rfi-report_student-loans.pdf.

[28] CFPB Press Release, CFPB Sues For-Profit College Chain ITT For Predatory Lending ITT Pushed Consumers into High-Cost Student Loans Likely to Fail (Feb. 26, 2014) available at http://www.consumerfinance.gov/newsroom/cfpb-sues-for-profit-college-chain-itt-for-predatory-lending/.

[29] CFPB Press Release, CFPB Wins Default Judgment Against Corinthian Colleges for Engaging in a Predatory Lending Scheme (Oct. 28, 2015), available at http://www.consumerfinance.gov/newsroom/cfpb-wins-default-judgment-against-corinthian-colleges-for-engaging-in-a-predatory-lending-scheme/.

[30] CFPB Press Release, CFPB Secures $480 Million in Debt Relief for Current and Former Corinthian Students (Feb. 3, 2015), available at http://www.consumerfinance.gov/newsroom/cfpb-secures-480-million-in-debt-relief-for-current-and-former-corinthian-students/.

[31] CFPB Press Release, CFPB Takes First Action Against ‘Buy-Here, Pay-Here’ Auto Dealer (Nov. 19, 2014), available at http://www.consumerfinance.gov/newsroom/cfpb-takes-first-action-against-buy-here-pay-here-auto-dealer/.

[32] CFPB Consent Order, In the Matter of Encore Capital Group, Inc., Midland Funding, LLC, Midland Credit Mgmt., Inc. & Asset Acceptance Capital Corp., (Sept. 9, 2015), available at http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201509_cfpb_consent-order-encore-capital-group.pdf.

[35] In 2013, the CFPB entered into a similar consent order with Ally Financial and Ally Bank.

[36] Under the order, Honda also has the option to move to non-discretionary dealer compensation.

[37] CFPB Consent Order, In the Matter of America Honda Finance Corp., (July 14, 2015), available at http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201507_cfpb_consent-order_honda.pdf.

[38] CFPB Consent Order, In the Matter of Fifth Third Bank, (Sept. 28, 2015), available at http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201509_cfpb_consent-order-fifth-third-bank.pdf.

[39] Complaint, CFPB v. Cellco Partnership d/b/a Verizon Wireless, No. 3:15-cv-03268 (D. N.J. May 12, 2015), available at http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201505_cfpb-cfpb-v-verizon-complaint.pdf; Complaint, CFPB v. Sprint Corporation, No. 0:14-cv-9931 (S.D.N.Y. May 12, 2015), available at http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201412_cfpb_cfpb-v-sprint-complaint.pdf .

[40] Complaint, CFPB v. Cellco Partnership d/b/a Verizon Wireless, No. 3:15-cv-03268 (D. N.J. May 12, 2015), available at http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201505_cfpb-cfpb-v-verizon-complaint.pdf; Complaint, CFPB v. Sprint Corporation, No. 0:14-cv-9931 (S.D.N.Y. May 12, 2015), available at http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201412_cfpb_cfpb-v-sprint-complaint.pdf.

[41] CFPB Stipulated Final Judgment and Order, CFPB v. Cellco Partnership d/b/a Verizon Wireless, No. 15-3268(PGS) (D.N.J. June 9, 2015), available at http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201506_cfpb-cfpb-v-verizon-stipulated-final-judgment-and-order.pdf; CFPB Stipulated Final Judgment and Order, CFPB v. Sprint Co., No. 14-cv-09931 (S.D.N.Y. June 30, 2015) [hereinafter Verizon and Sprint Consent Orders].

[42] Herb Weisbaum, Feds Ask Facebook, Google and Bing to Help Stop Student Loan Scams, NBC News (June 23, 2015), available at http://www.nbcnews.com/business/personal-finance/feds-ask-facebook-google-yahoo-help-stop-student-loan-scams-n380516.

[45] Verizon and Sprint Consent Orders, supra note 40.

[47] Kerri Ann Panchuk, CFPB hits two lenders with thousands in penalties over HMDA data: Washington Federal, Mortgage Master respond to allegation, (Oct. 9, 2013), available at http://www.housingwire.com/articles/27342-cfpb-hits-two-lenders-with-thousands-in-penalties-over-hmda-data.

[48] CFPB Consent Order, In the Matter of Ally Financial Inc. and Ally Bank (Dec. 20, 2013), available at http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201312_cfpb_consent-order_ally.pdf.

[49] CFPB Consent Order, In the Matter of First Investors Financial Services Group (Aug. 20,2014), available at http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201408_cfpb_consent-order_first-investors.pdf.

[50] Available at: http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201507_cfpb_ombudsman-office-mid-year-update.pdf .

[53] Available at: http://www.consumerfinance.gov/blog/the-2015-annual-report-from-the-cfpb-ombudsmans-office/.

[54] Available at: http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201603_cfpb_consent-order-dwolla-inc.pdf.

[57] Available at: http://www.consumerfinance.gov/newsroom/cfpb-takes-action-against-dwolla-for-misrepresenting-data-security-practices/.

[58] CFPB Strategic Plan, Budget, and Performance Plan and Report (2015), at 11.

The following Gibson Dunn lawyers assisted in preparing this client alert: Reed Brodsky, Arthur Long, Mary Beth Maloney, Christopher Lang, Melissa Goldstein, Royce Zeisler, James Springer, and former associates, Asad Kudiya and Chelsea Kelly.

Gibson Dunn’s Financial Institutions Practice Group lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these developments. Please contact any member of the Gibson Dunn team, the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, or the following:

Michael D. Bopp – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-955-8256, [email protected])

Reed Brodsky – New York (+1 212-351-5334, [email protected])

Arthur S. Long – New York (+1 212-351-2426, [email protected])

Mary Beth Maloney – New York (+1 212-351-2315, [email protected])

© 2016 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.