August 9, 2010

While Filings Are Down, Securities Litigation Remains Robust, As Major Cases Await Resolution, and Congress Creates New Litigation Risks for Public Companies and Their Directors and Officers

The first half of 2010 witnessed several significant new developments in the field of U.S. securities litigation and SEC enforcement, as well as new federal legislative reforms that may lead to new areas of private securities litigation in the future. Indeed, the Dodd-Frank legislation dramatically expands SEC regulatory authority, strengthens several substantive aspects of disclosure and reporting duties of public companies, and expands “clawback” liabilities of directors and officers in the event of a financial restatement, even when directors and officers had no knowledge of any wrongdoing.

Additionally, the Dodd-Frank bill purports to expand federal court jurisdiction over certain foreign issuers in actions brought by the SEC or U.S. Attorney, no doubt in response to the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark decision this Spring in Morrison v. National Australia Bank, which construed Section 10(b) of the 1934 Exchange Act not to apply to claims arising from securities of foreign issuers that were purchased on foreign exchanges, no matter how much the case involved domestic conduct in other respects.

Several important legal issues are percolating in the lower courts as well. Courts continue to address plaintiffs’ novel attempts to extend liability to secondary actors, as well as their attempts to artfully plead around the federal procedural restrictions in securities actions by dressing up their claims as state torts. The Fifth Circuit continues to impose stringent burdens on plaintiffs at the class certification stage to demonstrate loss causation as an element of the Rule 23 class certification analysis. And a recent Second Circuit ruling provides a tool that many defendants will want to explore at the pleading stage–the possibility of deposing purported “confidential witnesses” to test the good faith nature of plaintiffs’ allegations. These and other key 2010 decisions are discussed more fully below.

In short, the first half of 2010 was a busy one for securities litigation, with a variety of noteworthy developments.

Table of Contents

Key Court of Appeals and District Court Decisions

Safe Harbor for Forward-Looking Statements

Subprime and “Credit Crisis” Litigation

Pleading: Confidential Witnesses

1933 Act Section 12(a)(2)–Application to Private Offerings

Legislation

On July 21, 2010, President Obama signed the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (the Dodd-Frank Act), Pub. L. No. 111-203. The sweeping legislation totals more than 2,100 pages, and contains many reallocations and broad grants of federal regulatory authority. Most significantly for securities litigation, the Act includes the following substantive changes to the securities laws:

Sections 953E and 954 add a new Section 10D to the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (the “1934 Act”), requiring the SEC to prohibit national securities exchanges from listing any company that does not disclose incentive-based compensation that is based on financial information required to be reported under the securities laws, and instituting an incentive-based compensation clawback policy for accounting restatements. The clawback provision in the Dodd-Frank Act extends to all “executive officers” and applies to all incentive-based compensation received for three years following the filing of erroneous financials–regardless of whether the executive officer had knowledge of, or participated in, the alleged conduct giving rise to the restatement of the company’s financial statements. This is a fairly dramatic expansion of the clawback remedy available under Section 304 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, which has only authorized a limited “clawback” remedy against the CEO and CFO, and only for one year’s worth of compensation received prior to a restatement. The SOX clawback also included an “intent” element. The plaintiffs bar seems likely to argue that the new “clawback” provision in Dodd-Frank should be enforceable via private class or derivative suits.

- The Act dramatically expands several “whistleblower” protections under federal law:

- Section 922(b)(1) requires the SEC to pay a reward to individuals who provide original information that results in monetary sanctions exceeding $1 million. The award will range from 10 to 30 percent of the amount recouped.

- The Act prohibits retaliation against whistleblowers in the financial services industry who provide information about fraudulent or unlawful conduct related to the offering of a consumer financial product or service.

- The Act amends the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX) to broaden the scope of coverage, increase the statute of limitations, exempt SOX whistleblower claims from mandatory arbitration, and clarify that SOX claims proceeding in federal court can be tried before a jury.

- Additionally, the Act broadens the False Claims Act’s anti-retaliation provision, expanding the covered conduct to include protections for employees who are engaged in efforts to stop FCA violations. It also provides a federal statute of limitations of three years (whereas previously courts applied the most closely analogous state statute per Graham County Soil & Water Conservation Dist. v. U.S. ex rel. Wilson, 545 U.S. 409 (2005).

- Section 929O amends the Securities Act of 1933 (the “1933 Act”), the 1934 Act, and the Investment Company Act of 1940 (the “1940 Act”) to provide federal court jurisdiction in any action brought by the SEC or the U.S. Attorney arising out of the fraud sections of those acts, involving (1) conduct within the United States that constitutes “significant steps” in furtherance of the violation, even if the transaction occurs outside of the United States and involves only foreign investors or foreign advisers, or (2) conduct occurring outside the United States that has a foreseeable substantial effect within the United States.

- Section 35 keeps the SEC within the federal appropriations process (some versions of the Senate bill would have exempted it), but raises its funding. Press reports following passage of Dodd-Frank indicate that the SEC now plans to add another 800 employees–which is likely to strengthen the SEC’s bench strength to pursue more rigorous enforcement investigations against public companies and their directors and officers.

- Sections 929M, N, and O, expand the categories of actors who can be sued by the SEC for aiding and abetting liability. The new definition extends liability to persons who acted knowingly or recklessly, thus expanding the SEC’s powers to pursue enforcement actions against individuals who act with mere “reckless disregard.” Previously, the SEC’s power to seek aiding and abetting claims under the PSLRA was limited to “knowing” assistance, which had been interpreted by several courts to exclude merely reckless conduct. Nothing in the Act allows private civil actions against secondary actors, but this issue may not be off the table entirely, as Section 929Z requires a GAO study on the effects of authorizing such actions.

- Section 929E provides that nationwide service of subpoenas is available in civil SEC actions filed in federal courts.

For a more complete and exhaustive analysis of the Dodd-Frank legislation, see Gibson Dunn’s prior summaries regarding the provisions governing SEC enforcement authority, executive compensation and corporate governance, advisers to private funds, and derivatives regulation.

Settlement and Filing Trends

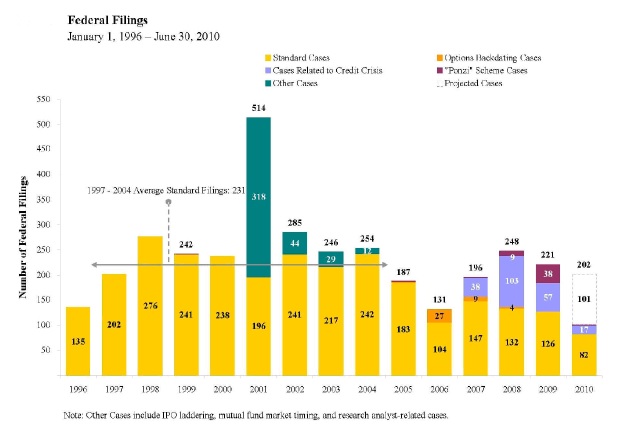

According to NERA Economic Consulting’s mid-year study of settlement and filing trends in federal securities class actions, there were 101 securities class action filings from January through the end of June of this year–an annual pace of 202 that would represent a decline from the 221 filings in 2009 and the 248 filings in 2008.

NERA found that a key factor contributing to the decline was a drop-off in filings related to the global financial crisis–there were 17 such cases filed in the first half of 2010, for an annual pace of 34, compared to 57 in 2009 and 103 in 2008. NERA noted, though, that financial crisis litigation is far from over, but the new filings more likely will take the form of state, local, derivative, ERISA and other types of litigation rather than securities class actions.

Chart used by Permission of NERA.

Another notable change in the NERA findings is that filings in the Ninth Circuit slightly surpassed filings in the Second Circuit, 26 to 25. Though the Second Circuit had more financial crisis cases, there were more “standard” cases in the Ninth Circuit.

Though financial sector companies saw more federal securities class actions than any other sector, such suits have declined from their 2008 peak. The largest percentage increase in filings in the first half of 2010 was against health technology firms, firms in the electronic technology and technology services sector and in the energy and non-energy minerals sector.

Partly due to a lower number of filings alleging earnings manipulation, accounting firms were named as co-defendants in federal securities actions in just 3% of cases, down from 13% in 2006. Almost 16% of filings named a foreign company as a defendant, a pace which slightly exceeded the previous high of 15% in 2004. No doubt this number will ultimately be impacted by the Supreme Court’s Morrison decision and the efficacy of Congress’s response in the Dodd-Frank bill.

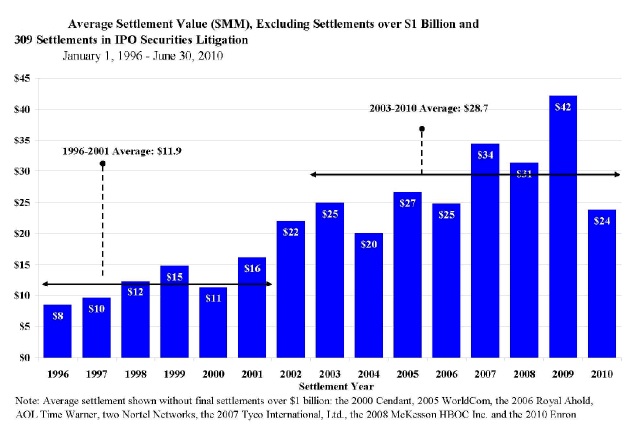

The NERA study found that the average settlement value in the first half of 2010 was a record $209 million, far exceeding the previous high of $80 million in 2006. NERA emphasized, though, that this included the $7.2 billion Enron settlement, which distorts the overall number. Excluding outliers, the average settlement was slightly below the average for the years since 2003, and down dramatically from the peak in 2009. The median settlement was nearly $12 million, whereas the median since the 1995 passage of the PSLRA had never exceeded $10 million.

Chart used by permission of NERA.

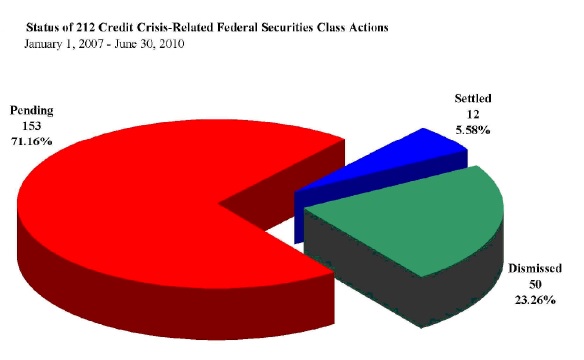

NERA also found that of the 212 credit crisis related filings from January 1, 2007 to June 30, 2010, 153 remained pending, 50 had been dismissed, and 12 had settled.

Chart used by permission of NERA.

Fees and expenses for plaintiffs’ attorneys make up approximately one-third of the settlement value, though this proportion decreases as settlement values go up. For settlements over $100 million, fees and expenses total 24%, and for settlements over $500 million, fees and expenses total 9.2%. NERA also examined the median ratio of settlement values to “plaintiff-style” claimed investor losses, which historically tend to move in tandem. For the first half of 2010, the ratio of 3.1% was at least as high as in any year since 2002.

Supreme Court

The first half of 2010 found several securities cases on the Supreme Court’s docket. The most significant arguably was Morrison v. National Australia Bank Ltd., 130 S. Ct. 2869 (2010), a landmark decision on the extraterritorial application of the United States securities laws. In Morrison, the Court held that plaintiffs that purchase securities on foreign exchanges cannot bring a federal securities fraud lawsuit under Section 10(b) of the Securities Exchange Act and SEC Rule 10b-5, promulgated thereunder. Writing for the Court, Justice Scalia held that the territoriality question was substantive, not jurisdictional, and that “Section 10(b) reaches the use of a manipulative or deceptive device or contrivance only in connection the purchase or sale of a security listed on an American stock exchange, and the purchase or sale of any other security in the United States,” even if fraudulent conduct allegedly occurred in the United States.

The Court’s ruling in Morrison has significant implications for issuers whose stock is traded on foreign exchanges, as it eliminates so-called “f-cubed” litigation–i.e., securities fraud suits on behalf of foreign purchasers of a foreign company’s shares on a foreign exchange. Indeed, Morrison essentially eliminates even “f-squared” cases, in that it prohibits even domestic plaintiffs suing foreign issuers for securities traded on foreign exchanges. Recently, in deciding competing motions for appointment of a lead plaintiff in securities litigation against Toyota Motor Corporation, Judge Dale Fischer of the Central District of California ruled that for purposes of determining which proposed lead plaintiff has the largest stake in the litigation (and without prejudice to plaintiffs arguing for a different interpretation later in the litigation), Morrison prohibits domestic plaintiffs who held Toyota’s common stock, which is not traded on U.S. exchanges, from bringing an action under Section 10(b) of the 1934 Act. See Stackhouse v. Toyota Motor Corp., No. 2:10-cv-0922-DSF (C.D. Cal. July 16, 2010). Shortly thereafter, the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York interpreted Morrison in the same way in a motion to dismiss. Cornwell v. Credit Suisse Group, No. 1:08-cv-03758-VM (S.D.N.Y. July 27, 2010) (granting motion to dismiss domestic plaintiffs that purchased Credit Suisse securities on the Swiss Stock Exchange). So did the Southern District of Florida in In re Banco Santander Securities-Optimal Litigation, No. 1:09-cv-20215-PCH (S.D. Fla. July 30, 2010). For more on Morrison, see Gibson Dunn’s client alert.

Not all of the Supreme Court’s securities litigation jurisprudence in the first half of 2010 favored defendants. In Merck & Co. Inc. v. Reynolds, 130 S. Ct. 1784 (2010), the Supreme Court held that the two-year statute of limitations for Section 10(b) claims does not begin to run until a “reasonably diligent” plaintiff would have discovered the facts constituting the violation, and that such “facts” included the fact of scienter. Although the Court distinguished its standard from “inquiry notice”–it was not enough merely that a reasonably diligent plaintiff would have investigated further–the Court emphasized that facts tending to show a statement’s falsity would not necessarily be sufficient to also show scienter, thereby potentially extending the period before the statute of limitations would begin to run. See Gibson Dunn’s summary of Merck here.

In the mutual fund area, in Jones v. Harris Associates L.P., 130 S. Ct. 1418 (2010), the Supreme Court clarified the standard for determining whether investment advisory fees are excessive within the meaning of Section 36(b) of the 1940 Act. The Court adopted a standard largely based on the Second Circuit’s decision in Gartenberg v. Merrill Lynch Asset Mgt., 694 F.2d 923 (2d Cir. 1982). The Gartenberg standard holds that to violate Section 36(b), an adviser “must charge a fee that is so disproportionately large that it bears no reasonable relationship to the services rendered and could not have been the product of arm’s length bargaining.” The Court rejected the application of a “marketplace” standard, which had been applied by the Seventh Circuit, under which courts would have played little role in assessing the reasonableness of fees. The Court did not adopt Gartenberg wholesale, though, as it emphasized that a “degree of deference” is due to a board’s decision to approve an adviser’s fees and it did not “countenance the free-ranging judicial ‘fairness’ review of fees that Gartenberg could be read to authorize.”

The Court also showed a willingness to preserve Congress’s regulatory schemes, even when some aspects of them run afoul of constitutional principles. In Free Enterprise Fund v. Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, No. 08-861, 2010 U.S. LEXIS 5524 (June 28, 2010), the Court ruled that separation of powers principles prohibit a “good cause” requirement for removal of members of the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board. The Court left the PCAOB’s regulatory authority intact, however, and merely severed the removal restrictions, thus making its members subject to removal at will by the SEC. This narrow holding may give clues to how the Court will view the various regulatory powers created by the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act.

More changes are likely to come in the Court’s next term. On June 14, 2010, the Court granted a writ of certiorari to review the Ninth Circuit’s decision in Siracusano v. Matrixx Initiatives, Inc., 585 F.3d 1167 (9th Cir. 2009). In Siracusano, as discussed in greater detail here, the Ninth Circuit reversed the District of Arizona’s grant of a motion to dismiss plaintiffs’ complaint alleging violations of Section 10(b), holding that the plaintiffs had adequately pleaded materiality, and that the lack of statistical significance of patient complaints regarding a product was not a proper basis to find that the alleged omissions were not material. The Ninth Circuit held that courts are required to consider whether the undisclosed information available to the defendants would be material to a reasonable investor even if there was no statistically significant evidence that the product was unsafe. The Ninth Circuit’s decision creates a split of authority with the First, Second, and Third Circuits, which have held that drug companies have no duty to disclose adverse event reports until those reports provide statistically significant evidence that the adverse events may be caused by, and are not simply randomly associated with, a drug’s use. See, e.g., N.J. Carpenters Pension & Annuity Funds v. Biogen IDEC Inc., 537 F.3d 35, 50 (1st Cir. 2008); In re Carter-Wallace, Inc. Securities Litigation, 220 F.3d 36, 41-42 (2d Cir. 2000); Oran v. Stafford, 226 F.3d 275, 284 (3d Cir. 2000).

The direct question presented by the certiorari petition in Siracusano is whether a plaintiff can state a claim under Section 10(b) based on a pharmaceutical company’s nondisclosure of adverse event reports, even though the reports are not alleged to be statistically significant. Nevertheless, the Court may reach broader issues regarding materiality and the role of statistical significance. As its ruling in Morrison suggests, the Court may address the issue before it more expansively than it was strictly framed by the lower courts.

The Court may also address the viability of securities fraud claims against secondary actors. On June 28, 2010, the Supreme Court granted certiorari in Janus Capital Group Inc. v. First Derivative Traders, No. 09-525, which raises important questions about the ability of private Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5 plaintiffs to bring securities-fraud suits against service providers for statements made by their clients. The Court will likely clarify the critical distinction between “primary” and “secondary” liability in private class actions. See Stoneridge Inv. Partners, LLC v. Scientific-Atlanta, Inc., 552 U.S. 148, 157-58 (2008); Central Bank of Denver, N.A. v. First Interstate Bank of Denver, N.A., 511 U.S. 164, 191-92 (1994). Petitioner Janus Capital Management LLC (JCM), a subsidiary of petitioner Janus Capital Group Inc. (JCG), is a registered investment adviser that, among other things, advises the Janus family of mutual funds. A purported class of JCG shareholders alleged that statements in the Janus Funds’ prospectuses were misleading and that JCM could be held liable for allegedly participating in the preparation of those prospectuses. The district court dismissed the complaint, but the Fourth Circuit reversed.

The Supreme Court will review two aspects of the Fourth Circuit’s decision: (1) the Fourth Circuit held that a service provider “made the misleading statements” contained in the prospectuses of a different company “by participating in the writing and dissemination of [those] prospectuses,” and (2) the Fourth Circuit held that a service provider can be held liable for a statement in another company’s prospectus “even if the statement on its face is not directly attributed” to the service provider. These two issues arise whenever a service provider–an accountant, a banker, a lawyer, or (as in Janus) an investment adviser–is sued in a private Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5 action on the basis of statements made by a public-company client of the service provider. Gibson Dunn represents the Janus petitioners in this matter.

Key Court of Appeals and District Court Decisions

Even outside of Congress and the Supreme Court, important new rulings have come down in the first half of 2010 in the circuit and district courts, across a variety of subject matters.

Safe Harbor for Forward-Looking Statements

The PSLRA’s safe harbor for forward-looking statements continues to be an important source of protection for potential targets of securities lawsuits. The safe harbor provides protection for

(A)(i) identified forward-looking statements with sufficient cautionary language;

(A)(ii) immaterial statements; and

(B)(i)-(ii) unidentified forward-looking statements or forward-looking statements lacking sufficient cautionary language where the plaintiff fails to prove actual knowledge that the statement was false or misleading.

15 U.S.C. § 78u-5(c)(1).

In affirming dismissal of a Section 10(b) claim against a cosmetic laser company based on its revenue projections, the Ninth Circuit in In re Cutera Sec. Litig., — F.3d —-, 2010 WL 2595281 at *7 (9th Cir. June 30, 2010), held that forward looking statements accompanied by meaningful cautionary language are encompassed by the PSLRA safe harbor regardless of the state of mind of the person making the statement.

Not surprisingly, then, an important question continues to be whether statements actually fall within the safe harbor. The Ninth Circuit in In re Cutera Securities Litigation affirmed dismissal of securities fraud claims based on the adequacy of the issuer’s risk factor disclosures. The disclosures at issue accompanied an earnings release and conference call. They stated that “these prepared remarks contain forward-looking statements concerning future financial performance and guidance;” that “management may make additional forward-looking statements in response to[ ] questions;” and that factors like Cutera’s “ability to continue increasing sales performance worldwide” could cause variance in the results. Cutera affirmatively warned that its ability to compete and perform in the industry depended on the ability of its sales force to sell products to new customers and upgraded products to current customers, and that failure to attract and retain sales and marketing personnel would materially harm its ability to compete effectively and grow its business.

By contrast, the Second Circuit’s May 2010 opinion in Slayton v. American Express found an issuer’s risk factor disclosure inadequate. Slayton v. American Express Company, 604 F.3d 758 (2d Cir. 2010). The court’s ruling has important implications for public companies and their executives in drafting “meaningful cautionary language” to accompany forward-looking statements. In April 2001, American Express recorded $182 million in losses in its high-yield debt portfolio. In the Management Discussion and Analysis (“MD&A”) portion of its form 10-Q which was filed with the SEC on May 15th, the company discussed the reasons for these losses and stated “[t]otal losses on these investments for the remainder of 2001 are expected to be substantially lower than in the first quarter.” American Express qualified this statement with a warning that “factors that could cause actual results to differ materially from [its forward looking statement] include . . . potential deterioration in the high-yield sector, which could result in further losses in AEFA’s investment portfolio.”

The court held that defendants were not entitled to protection under the meaningful cautionary language prong of the safe harbor because their cautionary language was too vague. But the court affirmed the dismissal, finding that defendants’ allegedly misleading statement was protected by the actual knowledge prong of the safe harbor. The court found that plaintiffs failed to plead facts supporting a strong inference that the statement was made with actual knowledge that it was false or misleading.

As these cases illustrate, the safe harbor is disjunctive rather than conjunctive, as protection for forward looking statements is available either when they are identified with meaningful cautionary language or when the defendant lacks actual knowledge of the falsity. To avoid disputes over the less predictable actual knowledge option, though, companies should emphasize when a statement is forward-looking by using phases such as “we believe” and “we expect” and make clear that statements with those words are intended to be forward-looking. In addition, companies should consider stating expressly that particularly significant statements are forward-looking.

Courts also continued to observe another important limitation on liability–the prohibition against private securities fraud actions against secondary actors. On April 27, the Second Circuit affirmed dismissal of a securities class action against Mayer Brown LLP over the law firm’s alleged role in the fraud at Refco Inc. Pacific Investment Management Co. LLC v. Mayer Brown LLP, 603 F.3d 144 (2d Cir. 2010). The court ruled that Mayer Brown was not alleged to have made any false statements attributed to it at the time of dissemination, and therefore plaintiffs could not have relied on any statements by the firm. The court found the allegation that Mayer Brown had been identified as counsel on Refco’s false offering memorandum and registration statements was not sufficient to constitute attribution.

As discussed above, the Supreme Court granted certiorari in Janus Capital Group Inc. v. First Derivative Traders, in which the Court will likely clarify the distinction between “primary” and “secondary” liability in private class actions.

Subprime and “Credit Crisis” Litigation

There were several significant cases related to subprime lending practices, some of which suggest judicial skepticism to claims arising from the mortgage and financial crises:

- In an unpublished disposition, the Ninth Circuit affirmed dismissal of subprime-related claims in Sharenow v. Impac Mortgage Holdings, Inc., No. 09-55533, 2010 WL 2640195 (9th Cir. June 29, 2010). The court held that the investors’ allegations of Impac’s inferior underwriting were not enough to create the inference that Impac and its executives issued false statements either intentionally or recklessly.

- In Local No. 38 Intern. Broth. of Elec. Workers Pension Fund v. American Exp. Co., — F. Supp. 2d —-, 2010 WL 2834226 (S.D.N.Y. 2010), the district court dismissed a Section 10(b) case for lack of scienter, though it allowed plaintiffs to seek leave to amend.

- In re Washington Mut., Inc. Securities, Derivative & ERISA Litigation, 2010 WL 2545415 (W.D. Wash. June 21, 2010), the court dismissed Section 10(b) claims (as well as state law claims for fraud and negligent representation) for failure to plead actual reliance with particularity, rejecting generic allegations that the plaintiffs “read and relied” on all offerings made in the offering circulars for the (unregistered) securities at issue and the incorporated SEC filings. The court granted leave to amend.

- The U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York dismissed securities fraud claims regarding the credit ratings and underwriting of mortgage-backed pass-through certificates. Iron Workers Local No. 25 Pension Fund v. Credit-Based Asset Servicing & Securitization LLC, No. 08-10841 (S.D.N.Y. Mar 31, 2010).

- The court in In re HomeBanc Corp. Sec. Litig., — F. Supp. 2d —-, 2010 WL 1524836 (N.D. Ga. Apr. 13, 2010), dismissed subprime-related claims under Section 10(b). The dismissal, which was with prejudice, was based largely on the issuer’s cautionary statements that warned of a challenging credit market, disclaimed guarantees that it was immune to market conditions, and warned about the uncertainty and risks endemic to its industry. The court stated that “[a]lthough these disclosures may not immunize every statement that Plaintiff alleges to be false or misleading, they do as a whole erode the essential allegations of Plaintiff’s complaint.”The court also found that even assuming actionable misstatements, the plaintiffs failed to plead scienter, finding that in the absence of allegations of personal benefit, the most cogent and compelling inference from the complaint was that “Defendants were simply unable to shield themselves as effectively as they anticipated from the drastic change in the housing and mortgage markets.” Finally, the court rejected the allegations of loss causation as well, noting that when the plaintiff’s loss coincides with a market-wide phenomenon causing comparable losses to other investors, “the prospect that the plaintiff’s loss was caused by the fraud decreases.”

- The court in SRM Global Fund L.P. v. Countrywide Financial Corp., 2010 WL 2473595 (S.D.N.Y. 2010), granted a motion to dismiss without leave to amend. Among other things, the court rejected claims that Countrywide made material misstatements and omissions in failing to disclose that it was “flying blind” with respect to its pay option ARM (i.e., adjustable rate mortgage) portfolio. Persuaded by disclosures in Countrywide’s SEC filings that, “[d]ue to the lack of significant historical experience at Countrywide, the credit performance of [pay-option ARM] loans has not been established for the Company,” the court found that the market was already aware of the alleged misstatements. For other statements, the court found that the allegations of scienter were insufficient, largely because there was no explanation why the defendants should have anticipated the housing crisis with accuracy.

- Not all was rosy for defendants, however. The district court in In re Citigroup Inc. Bond Litigation, No. 08 Civ. 9522 (SHS) (S.D.N.Y. July 12, 2010), largely left intact bondholders’ claims under the 1933 Act that were based on allegations that Citigroup misstated the risks associated with its involvement in subprime-related holdings. The court found the plaintiffs adequately pleaded allegations of actionable misstatements as to the extent of Citigroup’s exposure to its own subprime-backed CDOs, rejecting defendants’ contention that the market knew such holdings were customary. The court also sustained claims based on Citigroup’s alleged representation that its structured investment vehicles, which contained subprime mortgage-backed securities, were “high credit quality.” The court found that plaintiffs also adequately alleged misstatements in Citigroup’s financials–specifically alleged overstatements of its loan loss reserves, inaccurate representations that it was “well-capitalized,” and alleged failure to disclose Citigroup’s subprime exposure.

- In another Countrywide case–the shareholder and bondholder class action in the Central District of California–the parties agreed to a $624 million settlement from Bank of America, which acquired Countrywide, and its outsider auditors. In re Countrywide Fin. Corp. Sec. Litig., CV 07-05295 MRP (MANx). Gibson Dunn represents the underwriter defendants in this action. Settlement has received preliminary court approval.

- The parties in In re New Century Financial Corp. Sec. Litig., No. CV 07-00931-DDP-FMOx (C.D. Cal.) reached a settlement agreement as well. Pending court approval, the agreement calls for approximately $65 million to be provided on behalf of the directors and officers, the outside auditor to provide approximately $44.7 million, and the underwriters to provide approximately $15 million to settle the respective claims against them. The parties reached global settlements on all claims, including not only those claims alleged in the instant class action, but also the claims brought by the bankruptcy trustee, a related set of class plaintiffs in Kodiak Warehouse LLC, et al. v. Brad A. Morrice, et al., No. CV 08-1265-DDP FMOx (C.D. Cal.), and the SEC.

- New Jersey Carpenters Vacation Fund v. Royal Bank of Scotland Group, PLC, — F. Supp. 2d —-, 2010 WL 1172694 (S.D.N.Y. 2010), illustrates the lower bar plaintiffs face under Section 11 of the 1933 Act, which provides virtually strict liability for, among others, issuers and underwriters when securities are sold pursuant to offering documents that contain material misstatements or omissions. In the New Jersey Carpenters case, which involved mortgage-backed securities, several claims were dismissed for lack of standing because the plaintiff had not purchased certificates in the referenced trusts. As to the remaining trusts, the court concluded that the allegations of misstatements regarding underwriting guidelines were adequately pleaded because of allegations that the mortgage originators would systematically disregard the guidelines. The court also found that the risks associated with the underwriting guidelines were not otherwise adequately disclosed in the offering documents or suffused with cautionary language to “bespeak caution.”

Pleading: Confidential Witnesses

A recent ruling from the Second Circuit suggests an additional tool for defendants at the pleading stage of securities fraud allegations. In affirming dismissal of Section 10(b) claims, the Second Circuit ruled on April 6 that the district court was within its discretion to permit depositions of confidential witnesses to aid in resolving the motion to dismiss. Campo v. Sears Holding Corp., No. 09-3589-cv, 2010 U.S. App. LEXIS 7043 (2d Cir. Apr. 6, 2010). In a summary order, the court reasoned that the anonymity of the sources of plaintiffs’ allegations frustrates the requirement, announced in Tellabs, that a court weigh competing inferences to determine if the allegations of scienter are sufficient. The court also cited Rule 11 and noted that the use of the deposition testimony was limited to testing whether the confidential witnesses acknowledged the statements attributed to them.

The element of scienter continued to present a major hurdle for plaintiffs. In Thompson v. RelationServe Media, Inc., No. 07-13225, 2010 U.S. App. LEXIS 13371 (11th Cir. June 30, 2010), the Eleventh Circuit held that an allegation that internet-marketer RelationServe Media Inc. and its executives hid the company’s use of unregistered brokers to prevent disclosing a $2 million private offering was not sufficient to create an inference of scienter. Instead of fraud, the court found that the more plausible interpretation was that the defendants did not disclose use of the unregistered brokers because they believed the brokers were exempt from registration.

Scienter remained difficult to plead even in the hot-button area of mortgage underwriting. The Ninth Circuit affirmed the dismissal of class securities fraud charges against Impac Mortgage Holdings Inc. and two of its executives, finding that the plaintiffs did not allege enough facts to support an inference of scienter. Sharenow v. Impac Mortgage Holdings, Inc., No. 09-55533, 2010 WL 2640195 (9th Cir. June 29, 2010). The court concluded that the investors’ allegations of Impac’s inferior underwriting were not enough to create the inference that Impac and its executives issued false statements either intentionally or recklessly. The court noted that the complaint failed to discuss any specific underwriting guidelines, nor tie any purported violations of guidelines to the class period.

Similarly, the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York dismissed claims against Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce based on allegations that it misled investors about its mortgage-backed holdings and its ties with its hedging counterparty, the now bankrupt ACA Financial. Plumbers & Steamfitters Local 773 Pension Fund v. Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, 694 F. Supp. 2d 287 (S.D.N.Y. 2010). The court noted the absence of allegations that the defendants profited from the misstatements, and defendants’ lack of access to specific information that would have put them on notice that their statements were incorrect. The court rejected plaintiffs’ attempt to premise liability on the defendants’ presumed awareness of the rising difficulties in the subprime market, concluding that “knowledge of a general economic trend does not equate to harboring a mental state to deceive, manipulate or defraud.”

Although the PSLRA’s stringent pleading standard means most scienter defects will be addressed on motions to dismiss, scienter remains relevant at the summary judgment stage. In In re Remec Inc., Securities Litigation, 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 48415, at *109-10 (S.D. Cal. Apr. 21, 2010), the court held on a motion for summary judgment that an individual defendant’s position as CEO of the defendant company was insufficient to create a genuine issue of material fact regarding scienter. There, the class plaintiffs accused the CEO of misstating the company’s financial results by incorrectly accounting for goodwill impairment and argued, in part, that scienter could be inferred from the defendant’s position as CEO. Siding with the defendants, the Southern District of California found that the CEO’s title did not create an issue of fact that he was personally involved with the misconduct. The court therefore granted summary judgment to the CEO.

An important limitation on securities class actions continues to be the standing doctrine, as courts have consistently demanded that named plaintiffs actually have purchased the same securities as the class they seek to represent. Numerous cases have reached this result, and have dismissed securities claims at the pleading stage for lack of standing. See, e.g., City of Ann Arbor Employees’ Retirement System v. Citigroup Mortgage Loan Trust Inc., — F. Supp. 2d —-, 2010 WL 1371417 (E.D.N.Y. April 6, 2010); Massachusetts Bricklayers and Masons Funds v. Deutsche Alt-A Securities, 2010 WL 1370962 (E.D.N.Y. April 6, 2010); New Jersey Carpenters Vacation Fund v. The Royal Bank of Scotland Group, PLC, — F. Supp. 2d — 2010 WL 1172694 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 26, 2010); New Jersey Carpenters Health Fund v. Residential Capital, LLC, 2010 WL 1257528 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 31, 2010); New Jersey Carpenters Health Fund v. DLJ Mortgage Capital, Inc., 2010 WL 1473288 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 29, 2010); Public Employees’ Retirement System of Mississippi v. Merrill Lynch & Co., Inc., 2010 WL 2175875 (S.D.N.Y. June 1, 2010).

A few cases are illustrative. For example, in In re IndyMac Mortgage-Backed Securities Litig., — F. Supp. 2d —-, 2010 WL 2473243 (LAK) (S.D.N.Y. June 21, 2010), the court found that the plaintiffs lacked standing in all but fifteen of the 106 offerings referenced in their complaint. The court dismissed the remaining claims, which resulted in several of the underwriter defendants, represented by Gibson Dunn, being dismissed from the case entirely. Motions to intervene to add new plaintiffs with standing are pending before the court.

Similarly, the Southern District of New York dismissed putative class claims arising from the collapse of a structured investment vehicle, saying the named plaintiffs lacked standing because they were not investors in one of the challenged note series–even though the notes the plaintiffs did purchase allegedly involved the identical fraudulent conduct, ratings, seniority, and underlying assets. King County, Wash. v. IKB Industriebank AG, 09 Civ. 3387 (SAS), 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 48999 (S.D.N.Y. May 18, 2010). The court granted leave to amend to add named plaintiffs with standing.

In another S.D.N.Y. case, In re Lehman Bros. Sec. & ERISA Litig., 684 F. Supp. 2d 485 (S.D.N.Y. 2010), the court dismissed the vast majority of investors’ putative class claims under the 1933 Act based on 94 separate offerings of mortgage pass-through certificates by affiliates of Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. The named plaintiffs had only purchased certificates in six of the 94 offerings in the complaint. The plaintiffs claimed they could sue on behalf of a class of all purchasers of certificates containing the same alleged disclosure defects, but the court held that this approach contravened the constitutional standing requirement of an injury in fact.

The Second Circuit’s allowance of confidential witness depositions at the motion to dismiss stage does not mean, however, that the PSLRA stay of discovery is disappearing anytime soon. Joining a majority of courts rejecting plaintiffs’ attempts to obtain a partial lift of the stay to obtain materials previously produced in governmental investigations, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Ohio concluded that the stay cannot be lifted simply because the plaintiff claims it needs discovery to adequately plead scienter. Ohio Public Employees Retirement System v. Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corp., No. 4:08CV0160, 2010 WL 1628059, at *3-4 (N.D. Ohio Apr. 22, 2010). Although the court acknowledged that the plaintiff requested only a limited discovery stay in order to obtain a “closed universe” of materials already produced to the SEC, the court nonetheless adhered to the narrow criteria for lifting the discovery stay–i.e., to preserve evidence or to prevent unfair prejudice. See 15 U.S.C. § 78u-4(b)(B). And, the court reasoned, lifting the stay so the lead plaintiff can bolster its opposition to a motion to dismiss cannot constitute “undue prejudice” under the statute. The court also distinguished minority cases where the discovery stay was lifted, such as In re WorldCom, where the material was considered necessary to place the plaintiff on equal footing in pre-existing, ongoing settlement negotiations.

A similar result occurred in In re Thornburg Mortgage, Inc. Securities Litigation, No. 1:07-cv-00815-JB-WDS (D.N.M. July 1, 2010). There, the court found that plaintiffs had failed to show they would be unduly prejudiced by not being able to access documents previously produced by the issuer to government regulators and a bankruptcy creditors committee, despite claims that the class action plaintiffs allegedly needed the materials in order to evaluate settlement options. The timing of plaintiffs’ request to lift the discovery stay was suspicious, given that they were in the midst of filing a motion for leave to amend their complaint, which had just been dismissed by the court. The district court also was unpersuaded that the plaintiffs had any need to receive the documents to be on equal terms with government regulators and the creditors committee, absent any indication that those third parties were “competing for pieces of the same financial pie.” Gibson Dunn represents the underwriter defendants in this matter.

Importantly, the SLUSA amendments to the PSLRA also allow district courts to enjoin discovery in related state actions, “as necessary in aid of its jurisdiction, or to protect or effectuate its judgments.” 15 U.S.C. § 78u-4(b)(3)(D). This provision was applied in Buettgen v. Harless, 2010 WL 2573463 (N.D. Tex. June 25, 2010). The Buettgen federal action involved Section 10(b) claims based on alleged misrepresentations about the defendant company’s earnings. The federal plaintiffs’ claims focused on the defendant’s alleged understating its bad debt expense and allowance for doubtful accounts while overstating its revenues. Because a state case brought by another shareholder claiming fraud and negligent misrepresentation concerned the same alleged misconduct, the district court found that a stay of the state action was required to guard its jurisdiction to control discovery pending resolution of pleadings motions.

Another case illustrating the breadth of the PSLRA stay is The Lafayette Life Ins. Co. v. City of Menasha, 2010 WL 1138973 (N.D. Ind. Mar. 17, 2010). There, the district court denied a motion to reconsider a magistrate’s stay of the plaintiffs’ pursuit of documents from the defendant, a public entity, through a public records request outside of discovery. The court found that “the substance of the request for public documents made in the State court Mandamus Complaint [was] identical to the discovery that is automatically stayed in the federal matter until a ruling on a motion to dismiss.” The court therefore concluded that the request was a “discovery proceeding” that could be stayed to prevent evasion of the PSLRA.

Notably, however, state actions will not automatically be stayed simply because they involve discovery related to a pending federal securities case. In In re Regions Morgan Keegan Securities, 2010 WL 596444 (W.D. Tenn. Feb. 16, 2010), the court declined to enjoin a state action, finding the defendants had failed to demonstrate that “no reasonable means exist to remedy their concerns about the potential for discovery sharing short of the drastic step of enjoining an ongoing state-court proceeding.”

It should be emphasized that simply because proceedings are stayed pursuant to the PSLRA, it does not mean that parties are absolved from their obligations to preserve documents. The district court awarded sanctions against plaintiffs for failure to do so in Pension Committee of University of Montreal Pension Plan v. Banc of America Securities, LLC, 685 F. Supp. 2d 456 (S.D.N.Y. 2010). For a further information, see Gibson Dunn’s summary of Pension Committee.

The Fifth Circuit was the site of two significant loss causation cases. On February 12, the Fifth Circuit reaffirmed that for a Section 10(b) claim to gain class certification based on the fraud-on-the-market presumption, the plaintiff must establish loss causation. Archdiocese of Milwaukee Supporting Fund Inc. v. Halliburton Co., 597 F.3d 330 (5th Cir. 2010). In doing so, the court adhered to its prior holding from Oscar Private Equity Investments v. Allegiance Telecom, Inc., 487 F.3d 261 (5th Cir. 2007), rejecting the plaintiffs’ contention that the Oscar decision had been superseded by an intervening decision.

The U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Texas held that plaintiffs were not entitled to discover an issuer’s internal accounting data in support of their class certification motion. In re TETRA Technologies Inc. Sec. Litig., No. 4:08-cv-0965, 2010 WL 1335431 (S.D. Tex. Apr. 5, 2010). The court cited the “established principle that proof of loss causation in [the] context of a fraud-on-the-market regimen is drawn from public data.” Although not every circuit follows the Fifth in requiring proof of loss causation at the class certification stage, this holding may well resonate with other courts in discovery disputes leading up to the summary judgment and trial stages.

Recent loss causation holdings also demonstrate that the plaintiff must show that an alleged corrective disclosure reveals new facts to the market and does not merely recharacterize already known facts. For example, in In re Omnicom Group, Inc. Sec. Litig, 597 F.3d 501, 512 (2d Cir. 2010), the Second Circuit affirmed summary judgment in favor of the defendant company where the alleged disclosure was a Wall Street Journal article that negatively characterized a director’s resignation from the company. The article reported that the director had resigned after expressing concerns about an already public spin-off transaction and about the company’s corporate governance practices. According to the court, “[w]hat appellant has shown is a negative characterization of already-public information. A negative journalistic characterization of previously disclosed facts does not constitute a corrective disclosure of anything but the journalists’ opinions.”

A recent unpublished decision from the Ninth Circuit appears more lenient for plaintiffs, however. In a remarkably short memorandum disposition in In re Apollo Group Inc. Securities Litigation, No. 08-16971 (9th Cir. Mar. 3, 2010), the court reversed the district court’s grant of judgment as a matter of law in favor of Apollo, which had overturned a jury verdict for plaintiffs. Gibson Dunn represents Apollo in the case. The Ninth Circuit’s order stated only that the jury could reasonably have found that analyst reports (that had appeared a significant time after various newspaper articles reporting the same information) were nevertheless “corrective disclosures,” because they provided additional or more authoritative information that deflated Apollo’s stock price. The court did not address Apollo’s argument, which the district court accepted, that the analyst reports could not be “corrective disclosures” because they did not contain any new fraud-revealing information. It remains to be seen whether this more lenient approach will eventually make its way into binding precedent.

There were also several decisions addressing the “negative causation” defense under Section 11(e) of the 1933 Act. Under Section 11(e), defendants have the burden of proving that any damages suffered by the plaintiffs were the result of something other than the alleged misstatements. The cases so far this year illustrate that while negative causation can sometimes be a successful defense on motion practice, courts may display particular reluctance to apply the doctrine.

In Blackmoss Investments Inc. v. ACA Capital Holdings, Inc., 2010 WL 148617 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 14, 2010), the court dismissed with prejudice claims under Sections 11 and 12(a)(2) of the 1933 Act, finding the claims were barred by a negative causation defense. The court rejected the argument that negative causation could not be considered at the pleading stage, concluding it simply represented an application of the well-settled principle that claims may be dismissed at the pleading stage when an affirmative defense appears on the face of the complaint. The Complaint and ACA’s public filings upon which it was based established that the decline in ACA’s stock was not caused by the allegedly false and misleading statements in the Prospectus. ACA’s stock traded on the New York Stock Exchange above the November 10, 2006 IPO price of $13 per share through June 22, 2007. During that period, ACA disclosed updated information concerning its CDO portfolio, including the number of additional CDO deals that had been closed and the nature of the assets contained within them. Under these circumstances, the court concluded there was no causal relationship between the alleged misrepresentations and subsequent declines in ACA’s stock price.

In Hildes v. Andersen, 2010 WL 2836769 (S.D. Cal. July 19, 2010), the court dismissed a Section 11 claim with prejudice because it concluded that the parties entered a binding commitment for the purchase of the stock at issue before the date of the alleged misstatements in the offering materials. This established the negative causation defense, because the misstatements could not have caused the purchase or resulting damages.

Still, some courts exhibited resistance to the negative causation defense, in particular illustrating the difficulty in prevailing on this defense with motion practice. For example, in In re Metropolitan Securities Litigation, No. 2:04-cv-00025-FVS (E.D. Wash. Jan. 20, 2010), the court denied motions for summary judgment on the issue. The court found that to defeat a negative causation defense, the plaintiffs need only introduce evidence that the risk that caused the loss was within the zone of risk concealed by the defendant’s misstatement, and that the risk subsequently materialized. The court ruled that plaintiffs had done so by pointing to evidence that the auditor defendants’ opinions on the company’s financials concealed the risk of adverse tax treatment for a “FLIP” transaction. The court rejected the defendants’ argument that negative causation was established by the lack of a corrective disclosure concerning the audit opinions; it was enough that there were news articles announcing an IRS challenge to the transaction.

Similar resistance to the negative causation defense can be found in McGuire v. Dendreon Corp., 2:07-cv-00800-MJP (W.D. Wa. May 27, 2010). There, the court included in-and-out traders in a proposed class, despite the apparent likelihood that such traders would be subject to a negative causation defense (as by definition they purchased and sold their securities without an intervening corrective disclosure). The court expressed skepticism that prior Ninth Circuit law allowing inclusion of in-and-out traders had been overruled by the Supreme Court’s seminal decision on loss causation in Dura Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. Broudo, 544 U.S. 336, 338 (2005). And despite no allegation or evidence of how in-and-out traders could have been damaged, the court held that subsequent discovery might somehow save the claims.

An important complement to federal securities law continued to be the limitations under the Securities Litigation Uniform Standards Act (“SLUSA”) on plaintiffs artfully disguising their federal securities pleadings as state causes of action. On June 29, the Second Circuit held that SLUSA precluded retirees from pursuing class action claims under state law alleging that the defendants negligently misrepresented that if the employees retired early, their investment savings would be enough to support them through retirement. Romano v. Kazacos, — F.3d —-, 2010 WL 2574143 (2d Cir. June 29, 2010). The court found that the case involved securities covered by SLUSA’s preemptive sweep, as the retirees’ retirement savings were used to purchase mutual funds and listed securities or securities authorized for listing. The court also concluded that the alleged misrepresentations were made “in connection with” the purchase or sale of a covered security because the retirees essentially argued that the defendants induced them to invest in securities, rejecting the plaintiffs’ characterization of their claims as “garden variety” state negligence pleadings.

In another SLUSA case, the Sixth Circuit held a county sheriff was barred from bringing a class action challenging an alleged revenue-sharing scheme by Nationwide Life Insurance Co. and its affiliates. Demings v. Nationwide Life Ins. Co., 593 F.3d 486 (6th Cir. 2010). The court ruled that the case did not fall within SLUSA’s “state actions” exception, which exempts certain lawsuits by states, political subdivisions, and state pension plans for several reasons. First, the plaintiff sheriff was suing “on behalf of a plan” (a tax code Section 457 deferred compensation plan for the sheriff’s employees) but was not the plan itself. Under the state actions exception, the court found, the only entity that can bring a lawsuit on behalf of a state pension plan is the plan itself, not a third party acting on its behalf. Moreover, the sheriff had not brought the lawsuit on behalf of a class comprised solely of other states, political subdivisions, or state pension plans that were named plaintiffs. The court construed the state action exception to apply only where there is a class of named plaintiffs who have “authorized participation” in the lawsuit, which was not so in the present case, where the suit was simply a putative class action on behalf of those “similarly situated.”

In The Pension Committee of the Univ. of Montreal Pension Plan v. Bank of America Securities, LLC., 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 13766 (S.D.N.Y. 2010), however, the court found that SLUSA preemption did not apply where the plaintiffs purchased, sold, or held shares in hedge funds that are not covered securities under SLUSA even where the hedge fund maintains a portfolio that includes covered securities. The court concluded to do otherwise “would extend the reach of SLUSA to any investment vehicle with covered securities.”

Finally, on March 10, the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York held that SLUSA barred a Madoff action that relied on New York state securities law, even though Madoff allegedly made no actual purchases or sales of securities. Barron v. Igolnikov, No. 09 Civ. 4471(TPG), 2010 WL 882890 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 10, 2010). The court concluded that it was enough that the plaintiff alleged a fraudulent scheme that was in connection with the trading in the nationally listed securities in which Madoff claimed to be engaged.

The Seventh Circuit addressed the so-called “securities exception” to removal under the Class Action Fairness Act (“CAFA”) in Lincoln National Life Insurance Co. v. Bezich, — F.3d —-, 2010 WL 2541203 (7th Cir. June 25, 2010). CAFA allows defendants facing class action complaints in state court to remove to federal court under certain circumstances when the parties’ citizenship is minimally diverse–i.e., at least one plaintiff is a citizen of a different state than at least one defendant. (Note that in Hertz Corp. v. Friend, 130 S. Ct. 1181 (2010), the Supreme Court adopted the nerve center test to determine corporate citizenship for diversity purposes.)

One little-discussed exception to CAFA removal is the “securities exception,” under which defendants cannot remove certain securities-related class actions, including those “solely involv[ing] a claim . . . that relates to the rights, duties (including fiduciary duties), and obligations relating to or created by or pursuant to any security (as defined under section 2(a)(1) of the Securities Act of 1933 . . . .).” 28 U.S.C. § 1332(d)(9)(C) (emphases added). In Lincoln National, the court held that a variable life insurance policy–considered a hybrid of a security and a life insurance contract–was a “security” within the meaning of Section 2(a)(1) of the 1933 Act and therefore also within the meaning of the securities exception. The court also found that the case “solely” involved a claim relating to rights under the security, as plaintiffs claimed that the insurance company was violating the policy’s terms by inappropriately deducting “cost-of-insurance” premiums from accounts established under the policy. The court distinguished a claim for securities fraud, which would not necessarily have involved the rights created by the security. Because the securities exception to CAFA applied, the Seventh Circuit dismissed the petition for review of the district court’s remand order, and the matter will proceed in state court.

1933 Act Section 12(a)(2)–Application to Private Offerings

In Anegada Master Fund Ltd. v. PXRE Group Ltd., the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York dismissed a lawsuit under Section 12(a)(2) of the 1933 Act, which imposes liability for misrepresentations in a prospectus, because the plaintiffs claimed they were misled in a private offering not subject to prospectus delivery requirements. It was irrelevant, the court held, that the private offering occurred at the same time as a public offering in which the allegedly misleading prospectus was used. Anegada Master Fund Ltd. v. PXRE Group Ltd., 680 F. Supp. 2d 616 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 26, 2010).

The Anegada court further rejected the plaintiffs’ attempt to use the “integration doctrine” to argue that the private offering was covered by Section 12(a)(2). This doctrine was intended to prevent issuers from circumventing Section 5 registration requirements by, for example, splitting a single issuance of stock that should be registered between a registered offering and an otherwise exempt offering. In such situations, the purportedly private offering would be deemed public, and therefore the offering documents would constitute a prospectus, and Section 12(a)(2) liability could attach. In Anegada, however, the court held there was no basis for the integration doctrine, relying in part on SEC guidance that a private offering need not be integrated if it was made to QIBs under Rule 144 and “no more than two or three large institutional investors.” Plaintiffs alleged that the private offering was to QIBs, but pleaded no facts suggesting that there were more than two or three large institutional investors. The court therefore dismissed the claim, with leave to amend.

Investment Advisers-Mutual Funds

The first half of the year has also seen several cases involving mutual funds and their investment advisers. On April 1, the U.S. District Court for the District of Maryland held that the “anti-pyramiding” provision of 1940 Act Section 12(d)(1)(A)(i) does not create a private right of action, and therefore dismissed a suit under that provision for lack of standing. Gabelli Global Multimedia Trust Inc. v. Western Investment LLC, No. RDB 10-0557, 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 32161 (D. Md. Apr. 1, 2010). The anti-pyramiding provision bars an investment company from obtaining more than 3% of the shares of another investment company. In concluding that Section 12(d)(1)(A)(i) creates no private right of action, the court applied the framework established in Alexander v. Sandoval, 532 U.S. 275 (2001), which held that before a private right of action may be judicially implied, courts must ask whether the statute at issue displays an intent to create not just a private right but also a private remedy. The anti-pyramiding provision, the court held, created neither. The court followed VC Draper Fisher Jurvetson Fund I Inc. v. Millennium Partners L.P., 260 F. Supp. 2d 616 (S.D.N.Y. 2003), which reached the same conclusion.

On March 10, the First Circuit, sitting en banc, held that the SEC could not pursue allegations that two former executives of a mutual fund distributor were primarily liable under Rule 10b-5 for using false or misleading prospectuses to sell fund shares. SEC v. Tambone, 597 F.3d 436 (1st Cir. 2010) (en banc). According to the court, the SEC’s interpretation of Rule 10b-5(b) was overly expansive, as it suggested that one may “make” a statement within the purview of the rule by merely using or disseminating a statement without regard to the authorship of that statement or, in the alternative, that securities professionals who direct the offering and sale of shares on behalf of an underwriter impliedly “make” a statement, covered by the Rule, to the effect that the disclosures in a prospectus are truthful and complete. The court interpreted the word “make” in Rule 10b-5(b) to be narrower, drawing a distinction between the words “use” and “employ” used in Section 10(b). The court also found that the SEC’s interpretation of the Rule was “in tension” with the Supreme Court’s decision in Central Bank of Denver v. First Interstate Bank of Denver, 511 U.S. 164 (1994), which carefully circumscribed secondary liability, because the SEC’s rule would essentially seek to impose primary liability for a secondary violation of the Rule.

Predictably, the ripple effects of the housing crisis found their way to the mutual fund realm as well. On March 30, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California held that Section 13(a) of the 1940 Act applied to a mutual fund that unilaterally altered its stated policy regarding the concentration of its investments in uninsured mortgage-backed securities (“MBS”). In re Charles Schwab Corp. Sec. Litig., No. C 08-01510 WHA, 2010 WL 1261705 (N.D. Cal. Mar. 30, 2010). Section 13(a) states: “No registered investment company shall, unless authorized by a vote of a majority of its outstanding voting securities . . . deviate from its policy with respect to concentration of investments in any particular industry or group of industries, or deviate from any fundamental policy recited in its registration statement.” The mutual fund had a stated policy to invest no more than one-fourth of the fund in uninsured MBS or any other industry, but later reversed itself and exceeded the limit, by defining MBS not to be a stand-alone industry. The court acknowledged that firms are free to define “industry or group of industries” in any reasonable way, but that once a clear line had been drawn and investments were obtained, Section 13(a) required adherence to the stated definition absent a vote to alter it.

SEC Enforcement

Several significant SEC enforcement cases decided in the first half of 2010 are worth noting:

- On June 25, following a three-week trial, the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York dismissed the SEC’s first insider trading case involving credit default swaps (“CDS’s”). SEC v. Rorech, No. 1:09-cv-4329 (JGK), 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 63804 (S.D.N.Y. June 25, 2010). The Court held that Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5 apply to CDS’s, but found the SEC failed to prove the materiality or confidentiality of the information that the defendants shared–i.e., a contemplated change to the structure of the underlying corporate bonds. The case illustrates that even as the SEC brings enforcement actions involving newer or more “exotic” financial products, it will be constrained by the familiar elements of the securities laws.

- In a potentially ominous ruling from the perspective of corporate executives, the U.S. District Court for the District of Arizona held that the clawback provision for executives’ earnings under Section 304 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act does not require that the SEC allege wrongdoing on the part of the targeted executive. SEC v. Jenkins, No. 2:09-cv-1510-PHX-GMS, 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 57023 (D. Ariz. June 9, 2010). Although the court stated that this rule could lead to constitutional issues to the extent that the statute or remedy sought under it result in a severe and unjustified deprivation to the defendant, it concluded that these concerns required factual development not possible on a motion to dismiss. The holding was essentially codified in the Dodd-Frank bill.

- On March 24, the Second Circuit stayed pending appeal a lower court’s order directing Galleon defendants Raj Rajartnam and Danielle Chiesi to turn over wiretap evidence to the agency. At issue are more than 18,00 wiretap recordings of witnesses that the defendants received from the Department of Justice in parallel criminal proceedings. The U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York had ordered defendants to disclose the recordings to the SEC. The Second Circuit agreed to hear the case on an expedited basis, SEC v. Galleon Management LP, No. 10-462-cv (2d Cir. Mar. 24, 2010), and heard oral argument on July 8, 2010.

- An SEC enforcement defendant is barred by Section 21(g) of the 1934 Act from asserting counterclaims and cross-claims, according to a March 22 ruling by the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas. SEC v. Tsukuda-America Inc., No 3:10-CV-136-M, 2010 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 26851 (N.D. Tex. Mar. 22, 2010).

- On January 12, the D.C. Circuit held that the SEC abused its discretion in upholding an award of restitution to customers of a broker who was a general securities representative with Rauscher Pierce Refsnes Inc., an NASD member firm. The broker had improperly engaged in “selling away”–i.e., engaging in private securities transactions for clients without providing notice to Rauscher. The clients were wealthy investors specifically intending to speculate, however, and the broker did not profit from his wrongdoing. The SEC failed to identify any meaningful causal connection between the broker’s wrongful acts and the investors’ losses, leading the court to vacate the award. Siegel v. SEC, 592 F.3d 147 (D.C. Cir. 2010).

Gibson Dunn’s 2010 Mid Year Securities Enforcement Update contains a more detailed summary of the developments in the securities enforcement area.

Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these issues. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you work or any of the following members of the Securities Litigation Practice Group Steering Committee:

Jonathan C. Dickey – Practice Co-Chair, New York (212-351-2399, [email protected])

Robert F. Serio – Practice Co-Chair, New York (212-351-3917, [email protected])

Wayne W. Smith – Practice Co-Chair, Orange County (949-451-4108, [email protected])

Paul J. Collins – Palo Alto (650-849-5309, [email protected])

George B. Curtis – Denver (303-298-5743, [email protected])

Ethan Dettmer – San Francisco (415-393-8292, [email protected])

Gareth T. Evans – Los Angeles (213-229-7734, [email protected])

Daniel S. Floyd – Los Angeles (213-229-7148, [email protected])

Barry R. Goldsmith – Washington, D.C. (202-955-8580, [email protected])

Mark A. Kirsch – New York (212-351-2662, [email protected])

John C. Millian – Washington, D.C. (202-955-8213, [email protected])

John H. Sturc – Washington, D.C. (202-955-8243, [email protected])

M. Byron Wilder – Dallas (214-698-3231, [email protected])

Meryl L. Young – Orange County (949-451-4229, [email protected])

Please also feel free to contact any of the Securities Litigation Partners for further information about the topics covered in this alert.

This alert is also available in printable PDF format.

© 2010 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.