January 10, 2011

I. Overview of 2010

The year 2010 has been a watershed year for securities enforcement. The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act gave the SEC additional enforcement powers, while also bringing additional market participants under SEC registration and potentially elevating the standards of conduct for other securities professionals. At the same time, the SEC, working closely with criminal prosecutors, continued to pursue insider trading investigations based on recorded conversations and cooperating witnesses. In addition, the reorganization of the Enforcement Division into specialized units has started to yield enforcement actions in areas of priority. By all accounts, the heightened enforcement reflected this year will continue for the foreseeable future, putting a premium on the ability of in-house compliance programs to adapt to the changing regulatory landscape.

A. Enforcement Developments

1. Whistles at the Ready: The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act

On July 21, 2010, President Obama signed into law the Dodd-Frank Act, described by many as the most comprehensive package of financial regulatory reforms since the Great Depression.[1] The Dodd-Frank Act greatly reinforced and expanded the powers of the SEC.[2] Among other things, the Act expanded the ability of the SEC to impose penalties in administrative cease and desist proceedings, expanded the scope of the secondary liability in SEC enforcement proceedings, reaffirmed the SEC’s ability to pursue extraterritorial enforcement of the securities laws, and authorized the SEC to impose industry-wide bars against securities professionals who violate the securities laws.

But by far the most significant addition to the SEC’s enforcement program is the creation of a whistleblower bounty program. The Act provides that whistleblowers who provide the SEC or CFTC original information that leads to a successful enforcement action are now eligible for an award payment in proceedings where monetary sanctions exceed $1 million.[3] Awards can range from 10% to 30% of the total penalties collected.[4]

In November, the SEC announced proposed whistleblower regulations and invited public comment.[5] As we discussed in our prior alert, the most controversial aspect of the proposed whistleblower rules is whether they strike an appropriate balance between encouraging employees to report potentially unlawful activity to the SEC without undermining the ability of corporate compliance programs to address employee complaints internally. While an employee can report potentially unlawful activity at any time, the proposed rules do not require an employee to report a complaint internally to their employer before reporting to the SEC. To encourage internal reporting, the proposed rule provides that an employee may report to the SEC up to 90 days after the employee reports internally and have the complaint relate back to the date of the internal reporting.

Thus far, corporate commentators have focused on their belief that the rules as written could undermine existing corporate internal governance programs. For example, in a public comment letter organized by the Association of Corporate Counsel and signed by 266 companies, companies expressed concern that the whistleblower rules encouraged employees to avoid reporting known or suspected wrong-doing internally in order to maximize a potential payout under the whistleblower program.[6] The ACC sent a follow-up letter to the SEC emphasizing that, among other things, the proposed rules should include a requirement that the whistleblower report the alleged misconduct internally as a condition of eligibility for any award.[7] It also noted concern that the line between whistleblower and culpable actor be more clearly drawn, such that culpable actors who disclose wrong-doing in which they may have played some small part receive leniency for their cooperation in lieu of a bounty.

The Business Roundtable also submitted comments, suggesting that where a company has instituted SOX-compliant reporting processes, the Commission should require whistleblowers to report the issue internally and provide the company 180 days, rather than 90, within which to conduct an investigation.[8] It argued that these revisions would allow the SEC to accomplish its objective–timely receipt of reliable information regarding potential securities laws violations–without undermining the effectiveness of internal compliance programs. As a corollary to the argument, the Business Roundtable also suggested that the Commission provide SOX-compliant companies any potential whistleblower complaints the SEC received since passage of Dodd-Frank.

The SEC must issue its final rules by April 21, 2011.

The SEC reports that it has already received several potential whistleblower tips in the latter half of 2010.[9] The media has reported that a former employee of a major financial institution has submitted a whistleblower complaint to the SEC regarding alleged improprieties relating to management of its credit card debt-sales transactions. It is too early to tell whether any of the alleged tips received in 2010 will ultimately qualify for whistleblower awards under the new program. But with anticipated payouts, such as the $1 million bounty paid to the ex-wife of a hedge fund employee under the existing statutory bounty for insider trading cases, see our prior alert, it is likely that the number of whistleblower complaints will rise.

2. Cooperation Initiatives Show Results

The Enforcement Division’s new cooperation initiative began to take shape in 2010. We noted in our mid-year review that the Enforcement Division announced the availability of several different procedures designed to promote cooperation by individuals subject to investigation, including:

- Cooperation agreements;

- Deferred prosecution agreements;

- Non-prosecution agreements;

- Expedited immunity requests to the Department of Justice;

- Proffer agreements; and

- Oral assurances against recommending an enforcement action.

In the final days of 2010, the SEC announced its first non-prosecution agreement since announcing the new cooperation initiative. Carter’s Inc. received a non-prosecution agreement in the Staff’s investigation of Carter’s Executive Vice President, Joseph Elles.[10] The complaint alleged that Elles granted excess discounts to one of the company’s largest customers from 2004 to 2009 and concealed the discounts from the company’s accounting and finance departments. As a result, Carter’s allegedly understated its expenses and overstated its net income during this period. Elles allegedly realized pre-tax gains of over $4.7 million by exercising Carter’s stock options and selling Carter’s stock before the fraud was disclosed.

The SEC noted the following as significant in its decision to grant a non-prosecution agreement:

- Carter’s discovered the potential fraud on its own and immediately conducted an internal investigation;

- Carter’s reported the results of its investigation immediately after its conclusion and without prompting by the SEC;

- Carter’s made a “complete” report to the SEC (though it is unclear just what was meant by the term “complete”);

- The company cooperated in the investigation;

- The company took steps to remediate the violation; and

- The violation was of a relatively “isolated nature.”

This development provides an early view into what the Staff deems to be sufficient cooperation warranting some form of formal leniency, as well as what incentives the SEC may be willing to offer would-be cooperators. There are indications that a handful of individuals and entities are formally pursuing some form of leniency in exchange for cooperation. As formal cooperation gains traction, potential cooperators and their counsel will be in a better position to assess whether the rewards of cooperation will outweigh the costs and risks of not cooperating.

B. Statistics and Trends

1. Number of Civil Actions and Defendants Declined, But Litigation Percentage Remained Higher

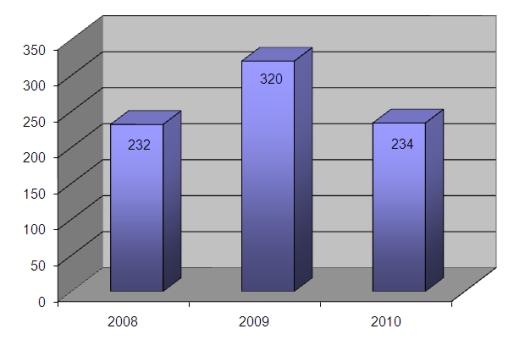

Over the last several years, we have tracked certain metrics of enforcement activity, identifying notable trends, including the number of civil actions filed, the number of defendants named in those complaints, and the percentage of defendants who settled at the time of filing. In 2010, the SEC filed a total of 234 civil injunctive actions, mirroring very closely its activity in 2008 but representing a 27 % drop compared to 2009.

Figure 1 — Civil Injunctive Actions Filed

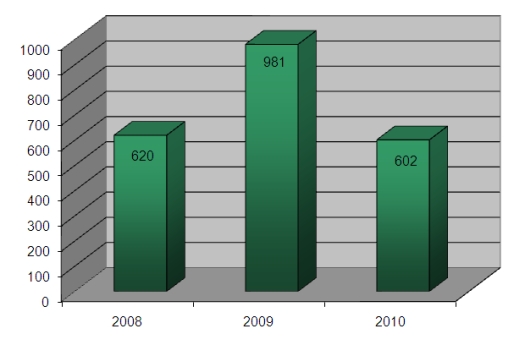

The number of defendants charged in civil proceedings declined as well, down to 602 from a high of 981 in 2009. This metric again reflects a return to 2008 levels, where a comparable number of defendants–620 individuals and entities–were charged in civil actions filed in federal courts.

Figure 2 – Number of Defendants Charged

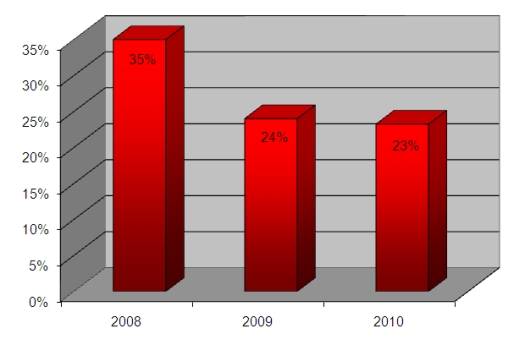

We have also tracked the percentage of defendants who settled at the time of filing. This statistic is significant because it is a potential indicator of the SEC’s willingness to charge defendants in the absence of settlements. Interestingly, despite the decline in the number of cases filed, and defendants charged in 2010, the percentage of defendants settled at filing remained relatively unchanged at 23%, a significant drop from the 35% level observed in 2008. This continues a trend we noted last year–that the SEC is filing more cases without settlements than it did previously. This suggests a greater willingness by the SEC to file cases without settlements. It also suggests that the SEC is taking on a greater litigation burden than it did previously.

Figure 3 – Percentage of Defendants Settled at Filing

Looking at the SEC’s statistics for fiscal year 2010 (ended September 30) as compared to fiscal 2009, the total number of enforcement actions rose slightly, to 681 from 664, representing a modest 3% increase. Notably, the number of injunctive actions decreased 19%, while the number of administrative proceedings increased 22%. With the Dodd-Frank Act giving the SEC the authority to impose civil monetary penalties against any respondent in an administrative proceeding, it is likely that the trend toward increased use of administrative proceedings will continue.

|

Fiscal |

Fiscal |

Fiscal |

|

|

Total Enforcement Actions |

671 |

664 |

681 (+3%) |

|

Injunctive Actions |

285 |

312 |

252 (-19%) |

|

Administrative Proceedings |

386 |

352 |

429 (+22%) |

2. New Formal Investigations Continue to Increase, While Closures Catch Up

The number of new investigations opened, and in particular the number of formal orders of investigation issued, continued to increase during fiscal 2010. However, it appears that the staff did a better job of closing investigations this past year, keeping better pace with investigation openings in 2010. Though closures are not back to 2008 levels, the number of matters closed in fiscal year 2010 increased by 36% over 2009. The number of investigations pending at fiscal year end therefore remained fairly unchanged, at 4,294 compared to 4,316 in fiscal year 2009.

|

Fiscal |

Fiscal |

Fiscal |

|

|

Investigations Opened |

890 |

944 |

952 (+1%) |

|

Investigations Closed |

1,355 |

716 |

975 (+36%) |

|

Investigations Pending at Fiscal Year End |

4,080 |

4,316 |

4,294 (-1%) |

|

Formal Orders of Investigation |

233 |

496 |

531 (+7%) |

3. Coordination with Criminal Prosecutors

Another notable trend demonstrates that the SEC’s collaboration with criminal prosecutors remained close in 2010. In fiscal year 2010, prosecutors filed indictments, informations or contempts in 139 cases, a slight drop compared to 154 in fiscal year 2009, but still a substantial increase over fiscal 2008.

|

Fiscal |

Fiscal |

Fiscal |

|

| Cases with Criminal Charges |

108 |

154 |

139 (-9%) |

4. Remedies Obtained

The monetary remedies sought and obtained by the SEC are particularly notable. Most significant, the amount of penalties ordered, at $1.03 billion, represents a nearly three-fold increase over the prior years, and is likely due to certain particularly large settlements discussed in this alert. Disgorgement, at $1.82 billion, represents a slight decrease from the prior year, but still a substantial increase over 2008. In contrast, the emergency remedies, typically sought by the SEC in cases to address alleged offering frauds, actually decreased in 2010 and returned to levels in 2008, suggesting that the post-Madoff spike in Ponzi scheme cases may be abating.

|

Fiscal |

Fiscal |

Fiscal |

|

|

Disgorgement Ordered |

$774 million |

$2,090 million |

$1,820 million |

|

Penalties Ordered |

$256 million |

$345 million |

$1,030 million |

|

TROs Sought |

39 |

71 |

37 |

|

Asset Freezes Sought |

46 |

82 |

57 |

C. Specialized Units and Significant Cases[11]

It has been a year since the Galleon case was filed, but insider trading again dominated the headlines as 2010 drew to a close. At the same time, the reorganization of the Enforcement Division into specialized units–including Asset Management, Market Abuse, Structured and New Products, Foreign Corrupt Practices, and Municipal Securities and Public Pensions–has resulted in a renewed substantive focus in certain activities and industries.

1. Insider Trading

Investigations of insider trading reached unprecedented levels in the latter half of 2010. As the year came to a close, the SEC and DOJ filed a number of civil and criminal insider trading cases, focusing most acutely on expert consulting networks. The networks match institutional investment managers with expert consultants. At issue in these inquiries is whether certain industry experts provide material nonpublic information to clients in breach of a duty of confidentiality.

As discussed in more detail below, thus far the investigations have already resulted in criminal charges against at least seven individuals — consultants and employees — connected to an expert consulting network. More important, the heightened regulatory focus on expert consultants has led many firms to re-evaluate their policies and procedures concerning the use of consulting networks in an effort to make sure such resources are used properly and reduce the risk that such resources inadvertently become the source of material nonpublic information.

2. Municipal Bonds

Marking the first time the SEC pursued a state for violations of the federal securities laws, the SEC issued an administrative order against New Jersey for allegedly misleading municipal bond investors as to the relative health of the state’s two largest pension plans, the Teachers’ Pension and Annuity Fund and the Public Employees’ Retirement System.[12] The state allegedly failed to disclose to bond holders that it had abandoned a planned “five-year phase-in plan” to begin making contributions to the pension plans that would satisfy mandated benefit increases for public employees. The state allegedly lacked policies or procedures addressing disclosure requirements under the federal securities laws and had not trained its employees on relevant obligations. In settling the charges with an administrative order and no penalties, the SEC noted the state’s cooperation and efforts to remediate the lack of controls and procedures that contributed to the disclosures.

The Municipal Securities Unit also announced a settled action against Banc of America Securities relating to the reinvestment of proceeds from sales of municipal securities.[13] Municipalities generally invest proceeds from sales of municipal securities until the monies are needed for their intended purpose. The proceeds must be invested at fair market value, which can be established through a competitive bidding process. In this case, the SEC alleged that the bidding process used to establish fair market value was tainted by the conduct of bidding agents that steered business to favored providers through various mechanisms. Banc of America Securities agreed to pay $36 million in disgorgement and interest, in addition to another $101 million paid to other federal and state authorities.

3. Credit Rating Agencies

In August, the SEC released a report detailing its investigation of the credit rating business of Moody’s Investors Service, Inc. The report concerns ratings of certain constant proportion debt obligation (“CPDO”) notes.[14] The SEC stated that Moody’s failed to disclose an error in its credit rating process for CPDO notes marketed exclusively in Europe. According to the Report, Moody’s learned of the error when one of its New York-based analysts compared the rating system output to that received from a U.S. investment bank and discovered an inadvertent error in the system’s coding.

The SEC did not bring an enforcement action, noting that its jurisdiction over the matter was questionable, given that the incident occurred in Europe and affected only European CPDO investments.[15] However, the report noted that the Dodd-Frank Act expressly extended jurisdiction to U.S. District Courts over SEC enforcement actions that involve “conduct within the United States that constitutes significant steps in furtherance of the violation, even if the securities transaction occurs outside the United States and involves only foreign investors” or “conduct occurring outside the United States that has a foreseeable substantial effect within the United States.”

4. Significant Monetary Sanctions

The SEC also asserted itself by obtaining significant monetary sanctions in settlements of previously filed actions. These sizeable settlements may also serve to incentivize would-be whistleblowers to bypass corporate compliance programs to secure their potential share of a reward. For example, in October, the SEC reached a settlement of its pending litigation against former Countrywide Financial Chief Executive Officer Angelo Mozilo. Under the settlement, Mozilo agreed to pay a $22.5 million penalty, the largest ever paid in an SEC settlement by a public company senior executive.[16] In addition, in July, Goldman, Sachs & Co. agreed to pay a $550 million penalty to settle the SEC’s pending litigation relating to the sale of a synthetic collateralized debt obligation.[17]

D. What to Look for in 2011

The roots of broadened enforcement power laid down by the Dodd-Frank Act will begin to take shape in early 2011. The SEC must adopt whistleblower rules by April 2011. Although the SEC has said that it does not presently have the funding to establish a whistleblower office, it is likely that the whistleblower bounty will lead to a significant increase in tips received and investigated. On a related note, one should also expect additional cases involving formal cooperation by individuals and entities. The rewards the SEC provides for cooperation will be critical to how individuals and their counsel weigh the costs and benefits of cooperation with the SEC in their investigations.

II. Insider Trading

Insider trading enforcement over the last six months has been extraordinarily active. In addition to pursuing traditional insider trading cases involving tipping and trading by corporate employees, the SEC and the Department of Justice have continued to develop allegations involving hedge funds, and most recently, they have targeted so-called expert networks. A number of high-profile cases have been filed or settled since mid-year, and more are sure to come. The major developments are set out below.

A. Expert Networks Take the Headlines

Recently, insider trading investigations have focused on the use of expert-network firms which connect investment professionals with expert consultants in various fields relevant to investment decision-making. At issue is whether the firms provide information that is merely difficult to obtain but lawful, or constitutes dissemination of material non-public information, in violation of insider trading laws.

On November 2, the Department of Justice and SEC announced criminal and civil insider trading charges against French doctor Yves Benhamou. Benhamou served on the steering committee that oversaw clinical trials of a new hepatitis drug being developed by a pharmaceutical company. At the same time, Benhamou had a consulting relationship with hedge funds that invested in healthcare-related securities. According to the complaints, Benhamou tipped a hedge fund portfolio manager about adverse test results from the clinical trials, and the hedge fund sold its shares in the pharmaceutical company. The price of the pharmaceutical company shares declined when the adverse test results were subsequently announced. The hedge fund allegedly avoided a loss of $30 million.[18]

Details of the SEC’s and DOJ’s wider pursuit of expert network firms began to emerge shortly thereafter, when the Wall Street Journal reported that John Kinnucan of Broadband Research, in an email to several clients, openly rebuffed an FBI overture to cooperate in an ongoing investigation by making recorded phone calls with one of his research contacts.[19] In the following weeks, Kinnucan received subpoenas from the FBI and SEC.[20]

Shortly thereafter, on November 22, the FBI executed search warrants at the offices of three hedge funds in New York, Connecticut, and Massachusetts.[21] The U.S. Attorney’s Office and SEC also issued subpoenas to several mutual funds and hedge funds.

On November 24, the U.S. Attorney’s Office filed criminal charges against an expert network firm employee, Don Ching Trang Chu. The criminal complaint alleges that the defendant arranged for public-company insiders to provide hedge fund clients with advance information on public-company financial performance.[22]

On December 15, federal prosecutors charged four other individuals connected to an expert consultant network. Three consultants and one expert-network firm employee are alleged to have tipped material non-public information to hedge funds and mutual funds.[23] The information included sales data about popular technology products and significant technology companies.

Finally, on December 29, authorities arrested Winifred Jiau, a consultant who allegedly provided material nonpublic information concerning the financial performance of certain technology companies, making her the seventh individual charged in the latest string of cases involving expert consulting networks.[24]

The cases involving consultant networks raise a number of significant issues for institutional investors. While consultants can provide helpful information that does not run afoul of insider trading laws, there is also a risk that in certain cases individuals can cross the line into prohibited conduct. In light of the government’s focus on expert consultants, many firms are re-evaluating their policies and procedures on the use of such networks in an effort to reduce the risk of inadvertent receipt of material nonpublic information in breach of a duty.

Finally, another notable aspect of these cases is what the complaints reveal about the investigations that led to the arrests. Many of the allegations are derived from recorded conversations between the defendants and cooperators that appear to have been developed through earlier investigations, including the Galleon case. The continued use by the government of cooperating witnesses and recorded conversations means that care must be exercised to ensure that communications conform to appropriate standards.

B. Developments in Notable Cases

There have been recent developments in a number of cases highlighted in our mid-year review.

1. SEC v. Galleon Management and Related Cases

In SEC v. Galleon Management,[25] the Second Circuit held that a district court may order production to the SEC of wiretap evidence obtained by a defendant in discovery in a parallel criminal proceeding, but that the court’s authority is circumscribed. The defendants in Galleon had obtained wiretap evidence from prosecutors in the parallel criminal proceeding. The SEC, in its civil action, sought discovery of that evidence, and the district court ordered its production. The Second Circuit, issuing an extraordinary writ of mandamus, vacated the district court order. The Court of Appeals held that while production of wiretap evidence is not prohibited, neither is it universally permitted. In deciding whether production is appropriate, a district court must balance the SEC’s interest in obtaining discovery against the defendant’s privacy interest. The Court of Appeals held that the district court exceeded its discretion by issuing the discovery order. The Court of Appeals also noted that the issue could have been averted by staying the SEC’s civil case pending resolution of the criminal case.

Shortly after the Second Circuit’s resolution of the wiretap discovery dispute, four defendants agreed to settle charges.[26] Broker-dealer Schottenfeld Group settled charges that three of its proprietary traders, on the firm’s behalf, traded on inside information obtained from an informant. Roomy Khan, a former employee at Galleon, similarly settled charges that she traded on inside information obtained from various sources. In the related case of SEC v. Santarlas,[27] former Ropes & Gray attorney Brien Santarlas settled charges that he passed inside information about firm clients to traders also named in Galleon.

The district court presiding over the criminal prosecution ultimately upheld the government’s use of wiretap evidence.[28] The court rejected the defendants’ argument that the government was not entitled to use wiretaps to investigate insider trading under the Federal Wiretap Act. Although the Federal Wiretap Act does not authorize the use of wiretaps to investigate allegations of insider trading alone, wiretaps may be used to investigate allegations of wire fraud. And when an insider trading scheme was conducted using interstate wires, the court found, it qualified as wire fraud. The court further found that the government’s use of wiretaps was necessary because the Galleon insider trading scheme was primarily conducted through telephone conversations. Once the wiretap evidence was deemed admissible in the criminal proceeding, the SEC revived efforts to obtain the wiretap recordings in the civil suit.

2. SEC v. Cuban

In an important case regarding the elements of proof in a “misappropriation” insider trading case, the Fifth Circuit in SEC v. Cuban[29] reinstated the SEC’s case against Mark Cuban, ruling that the district court had erred in dismissing the SEC’s case. The SEC’s complaint alleged that the CEO of Mamma.com, in which Cuban was a minority shareholder, telephoned Cuban to ask whether he wanted to purchase shares in a planned private investment in public equity (“PIPE”). The complaint alleged that the CEO prefaced the conversation by saying that the information was confidential and that Cuban agreed. According to the SEC, Cuban grew upset when he learned of the PIPE offering and said to the CEO, “Well, now I’m screwed. I can’t sell.” Subsequently, Cuban allegedly contacted the sales agent and learned additional confidential details about the offering. Cuban later allegedly sold his entire position in Mamma.com stock before the public announcement of the PIPE offering.

In July 2009, the district court dismissed the SEC’s complaint, holding that it did not sufficiently allege an agreement not to trade in Mamma.com shares. The court reasoned that where an agreement serves as the basis for misappropriation-theory liability, that agreement must include not only a promise by the defendant to keep the information confidential, but also an agreement not to trade on it. The SEC’s complaint was deficient, according to the district court, because it failed to plead that Cuban agreed to refrain from trading on the information learned during his conversation with the Mamma.com CEO.

In September 2010, the Fifth Circuit reversed the district court, holding that it was plausible to infer from the complaint that Cuban had agreed not to trade and that his understanding with the CEO “was more than a simple confidentiality agreement.” While it agreed with the district court that the “I’m screwed” statement in isolation did not constitute an agreement not to trade, the Court of Appeals found that there was a reasonable basis to conclude that Cuban’s additional efforts to gain confidential information by contacting the sales agent demonstrated that Cuban understood that he could not use the information for his personal benefit. However, the Court declined to decide the broader issue of whether a confidentiality agreement alone can satisfy the duty requirement of insider trading, or whether an express agreement not to trade is also required.

C. Victories for Hedge Fund Personnel

In two closely watched insider trading cases involving hedge funds, defendants scored significant litigation victories. In September 2010, a hedge fund manager and his co-defendants won summary judgment in SEC v. Obus.[30] The SEC had alleged that defendant Brad Strickland, an employee of GE Capital Corp., tipped his friend, defendant Peter Black, about an acquisition of SunSource, Inc., and that Black then tipped his boss, defendant Nelson Obus, who allegedly directed the purchase of SunSource stock. The alleged tip occurred during a conversation between Strickland and Black, which the defendants argued constituted a due diligence inquiry into SunSource on the part of Strickland, who noticed that Black’s employer was invested in SunSource.

The district court dismissed the claims against all defendants, finding that the SEC failed to adduce enough evidence to demonstrate that defendant Strickland breached a duty under either the classical or misappropriation theories of liability. The record was bereft of any facts to support that Strickland owed a fiduciary duty to the target, SunSource, under the classical theory, because Strickland was not an insider of SunSource and could not have become a temporary insider because his employer was not a fiduciary but rather just one of many banks that was considering a loan to SunSource. The court pointed out that financial institutions typically owe no fiduciary duties to borrowers, and that the arms-length negotiations between transacting parties are antithetical to the concept that either party would owe a fiduciary duty to the other. The court also dismissed the SEC’s claims under the misappropriation theory, finding that the evidence, viewed in the light most favorable to the SEC, established that, although Strickland owed a fiduciary duty to his employer, he did not breach that duty.

The court also found that the SEC failed to adduce any evidence of deceptive conduct. In fact, the court noted, defendant Obus openly spoke with SunSource’s CEO both before and after he directed the purchase of SunSource stock, therefore negating any inference of deception by someone secretly in possession of material non-public information. Furthermore, the factual record was insufficient to prove that Obus subjectively believed that the information he allegedly received was obtained in breach of a fiduciary duty.

SEC v. Berlacher represents another notable victory for hedge funds.[31] As part of a larger federal investigation of hedge funds alleged to have acted on inside information in shorting PIPE investments, the SEC charged hedge fund manager Robert Berlacher with insider trading. In a 2007 complaint, the SEC alleged that Berlacher, his investment advisory entities, and the hedge funds he managed illegally profited by short-selling four companies’ shares while in possession of pre-announcement knowledge about those companies’ planned PIPE offerings. In September 2010, the district court dismissed the insider trading charges. The court found that the SEC had not proven the materiality element of insider trading because it failed to show that disclosure of the offerings actually affected stock prices.

D. A Focus on Professionals

The year also brought several insider trading cases involving professionals, including public accountants and lawyers. The latest such case involved charges against an investment banker involved in an insider trading scheme with an attorney in Ernst & Young’s Transaction Advisory Group.[32] Banker Richard Hansen allegedly received material non-public information concerning five undisclosed pending acquisitions involving Ernst & Young clients by way of a mutual friend.

In another case involving a “big four” partner, the SEC settled insider trading charges against former Deloitte & Touche LLP partner Thomas Flanagan and his son Patrick Flanagan for trading in securities of several Deloitte clients.[33] According to the SEC complaint, Thomas Flanagan illegally traded nine times between 2005 and 2008, each time based on non-public information obtained from clients. The trades resulted in illegal profits of more than $430,000. Flanagan also relayed the information to his son who illegally profited as well. The Flanagans agreed to pay approximately $1.1 million to settle the charges. Thomas Flanagan also settled contemporaneous administrative proceedings for violating auditor independence rules.

E. Testing the Limits of “Inside Information”

In September, the SEC filed insider trading charges against two railroad company employees and their relatives.[34] The case has sparked some debate about the contours of the materiality of information that employees observe in the course of their employment. The SEC alleges that the defendants made more than $1 million in profits by trading on and tipping material non-public information about the planned takeover of their employer. The defendants allegedly gleaned the information from observations made on the job: they noticed people dressed in business attire touring the rail yards, heard other employees discuss a possible acquisition, and assisted in responding to requests for asset valuations. The SEC alleged that the defendant employees signed their employer’s code of conduct prohibiting them from trading or tipping while in possession of material non-public information about their employer, including merger and acquisition information. By trading on and tipping information learned while at work, the SEC claims, the defendant employees breached their fiduciary duties to their employer. In November, one defendant settled the SEC’s claims against him, and in December, the others moved to dismiss the claims.

III. Investment Advisers

The post-Madoff regulatory focus on investment advisers continued. Recent cases against investment advisers reflect an emphasis on protection of elderly, unsophisticated and more vulnerable investors as well as on breaches of fiduciary duties and accurate and timely disclosure to investors. Legislative and rule changes under Dodd-Frank expanded the scope of investment adviser regulation.

A. The Dodd-Frank Act Changes the Landscape

1. Elimination of the Private Investor Exemption

Among the sweeping changes of Dodd Frank is its elimination of the “private investor exemption” from the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 (the “Advisers Act”). The private investor exemption had allowed an investment adviser who during the course of the preceding 12 months had fewer than 15 clients and did not hold himself or herself out to the public as an investment adviser or act as an investment adviser to any registered investment company to avoid registration with the SEC. However, this exemption’s elimination will now require many advisers to hedge funds, private equity funds, real estate funds and certain other private funds with assets under management of $150 million or more to register with the SEC by July 21, 2011. Advisers to venture capital funds will not be required to register with the SEC, but will be required to maintain records and provide annual and other reports as prescribed by the SEC. In addition, “family offices”–firms that provide investment advice only to family members and are wholly owned and controlled by family members–will continue to be exempted from regulation under the Advisers Act.[35]

By registering with the SEC, an adviser becomes subject to a range of substantive provisions of the Advisers Act, including the requirement to adopt policies and procedures designed to prevent violations of the Advisers Act.

For a more complete analysis of the impact of the Dodd-Frank Act on investment advisers, see our prior alert entitled, Investment Advisers to Private Funds — Registration Under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940.

2. Increased Disclosure Requirements under the Dodd-Frank Act

Both Congress and the SEC expect investors to receive enhanced disclosure from their financial services providers about the scope of their adviser / customer relationship. Under rules proposed by the SEC under Dodd-Frank, registered advisers must provide organizational and operational information about the funds they manage, the types of clients they advise, their employees and their advisory activities.

The extent of disclosure that can be expected by the SEC was demonstrated by a recent case against an investment adviser for failing to disclose to its clients that moving them among alternate investments, within the adviser’s own firm, would result in increased commission for the adviser. The SEC’s administrative order alleged that by omitting the information related to the commission, the adviser “fail[ed] to fully and adequately disclose a material conflict of interest.” While the adviser did disclose the increase in commission costs to investors who switched investments, it failed to inform investors of the entire commission mechanism involved in the switch. The adviser’s commission was capped at 10% of the client’s initial investment, but if a client switched from a Series A to a Series B investment, which many of the clients did, this would “reset the clock” on commissions, and the adviser could potentially receive 10% of this new entire investment. The SEC found that a majority of the adviser’s clients who switched were nearly at the 10% threshold. The adviser settled the action and agreed to pay penalties and commissions back to the affected investors.[36] For a more detailed discussion, see our earlier alert on this case, Disclosure of Advisor Conflicts — When Is It Enough?

B. Cases Against Investment Advisers

1. Disclosures Regarding Valuation of Assets

During 2010, the SEC took enforcement action against investment advisers and fund managers for allegedly inflating the value of assets in their funds. In October 2010, the SEC charged two hedge fund managers and their investment advisory business with allegedly overvaluing illiquid fund assets that had been placed in a “side pocket.” A side pocket is a type of account that hedge funds use to separate particular investments that are typically illiquid from the remainder of the investments in the fund. The SEC alleged that the hedge fund managers overvalued the assets in the side pockets to avoid recognition of losses on the investments and in turn received fees based on the inflated values.[37]

The SEC filed similar allegations against an investment adviser for overvaluing an investment in a manner inconsistent with the valuation procedures set out in the fund’s offering materials. According to the offering materials, the fund’s assets were supposed to be valued by a clearing broker or independent pricing service. Instead, the adviser allegedly used the acquisition cost of the securities to value the assets, which the adviser allegedly should have known was based on erroneous information. The SEC is seeking injunctive relief, disgorgement of profits, prejudgment interest and financial penalties.[38]

In September 2010, the SEC charged former chief investment officer and former product engineer of State Street Bank with making misstatements about the Bank’s exposure to subprime mortgage investments.[39] State Street Bank settled with the SEC earlier in the year, and it agreed to pay $300 million in penalties.[40]

2. Pay to Play

One of the more notable “pay to play” cases of 2010 involved charges against Quadrangle Group principal, Steven Rattner.[41] The SEC alleged that in order to secure investments from the New York State Common Retirement Fund, Quadrangle made kickback payments and Rattner arranged for distribution of a low-budget film produced by the Fund’s chief investment officer and his brothers. Rattner settled the charges without admitting or denying the SEC’s allegations, agreeing to pay $6.2 million and agreeing to a two-year bar from associating with an investment adviser or broker dealer.

3. Short Selling Ahead of Public Offerings

The SEC has continued its efforts to combat abusive short-selling with its use of amended Rule 105 of Regulation M. The rule prohibits short selling before a secondary offering, usually for a period of five days, while purchasing that same security in the offering. The rule applies regardless of the investor’s intent. In September 2010, the SEC charged a firm with violating Rule 105 four times and charged further that the firm’s policies to prevent short-selling were poorly implemented and inadequately designed. That a different person within the firm shorted the stock than the person who purchased in the offering was not a defense.[42]

The SEC’s order instituting proceedings alleged that the “separate account” exception, which allows purchase of a security in an account that is “separate” from the account from which the security is sold, did not apply here because the portfolio managers had access to each other’s reports and data, reported to the same chief investment officer, and the two portfolio managers were allowed to consult with one another. The investment adviser agreed to pay approximately $2.653 million in disgorgement, fines and prejudgment interest in settling the charges, without admitting or denying the SEC’s allegations.[43]

In May 2010, the SEC brought and settled actions against two individuals for violating Rule 105 of Regulation M.[44] In November 2010, the SEC brought a Rule 105 action against New Castle funds for short sales in offerings of Wells Fargo and Anarko Petroleum Corp.[45] Most recently, on December 7, 2010, the SEC charged and settled a case against Gartmore Investment Limited, a London based manager of investment funds, for short-selling abuses that transpired in 2009.[46]

4. Elderly and Unsophisticated Investors

The SEC continued to bring cases to protect elderly and unsophisticated investors. In September 2010, the SEC brought actions against two investments advisers for targeting these types of investors.

First, the SEC charged an investment adviser and three of her advisory firms for overseeing a multi-million dollar offering fraud and selling phony promissory notes to a largely unsophisticated and elderly investor base. The adviser informed the investors that the investments, which purportedly loaned money to Medicaid-reimbursed doctors, were FDIC-insured when in fact, the investments were not and none of the investors’ money was in fact invested. The adviser stole the money and paid business debts and personal expenses, including many vacations.[47] The adviser settled the charges and agreed to an SEC administrative order barring her from any future association with any investment adviser or broker dealer.[48]

Also in September, 2010, the SEC charged another investment adviser with fraud and breach of fiduciary duty for marketing and recommending his firm’s riskier hedge funds to elderly investors who were led to believe that the funds provided low-risk, conservative investments. The adviser falsely stated to investors that the funds were diversified and could soundly represent an investor’s entire investment portfolio. These verbal statements contradicted the risk disclosures contained in the funds’ private placement memoranda.[49]

5. Ponzi Schemes

Following its December 2008 enforcement action against Bernard Madoff, the SEC continues to bring enforcement actions against managers and individuals engaged in a variety of Ponzi schemes. For example, in October 2010, the SEC charged two Florida-based hedge fund managers with fraudulently funneling large quantities of investor money through a Ponzi-type scheme. According to the compliant, the investment advisers promised investors that proceeds from their investments would be used to finance the purchase of consumer electronics to be sold to “Big Box” retailers; however, the note proceeds were instead used to pay off earlier investors. Throughout the investment period, the advisers continued to falsely report that the funds were generating steady profits. At the time of its collapse, the fund was holding more than one billion dollars in worthless notes.[50]

IV. Broker-Dealer Cases

A. The Dodd-Frank Act and the Fiduciary Standard of Care

The Dodd-Frank Act gave the SEC rulemaking authority to craft a uniform standard of care for broker-dealers and investment advisers. Under Section 913 of the Act, the SEC is required to study the effectiveness of the existing legal and regulatory standards of care for broker-dealers and investment advisers.[51]

Presently, under NASD Rule 2310, a broker-dealer need only ensure that the securities they are selling are “suitable” for their clients.[52] In contrast, under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, investment advisers are held to a higher “fiduciary” standard in which they must consider the best interests of the clients they serve.[53] On July 27, 2010 the SEC published a request for comments and public input pursuant to the Dodd-Frank Act.[54] The request has generated over 3,000 responses.[55] The Commission is required to produce the much anticipated and commented upon study to the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs and the House of Representatives Committee on Financial Services by January 2011.[56] Thus far, the staff has been careful not to indicate the positions it expects to take in the report. However, SEC Chairman Mary Schapiro has indicated her support for a “uniform fiduciary standard,” noting as recently as July of this year that “investors who turn to a financial professional often do not realize there’s a difference between a broker and an adviser.”[57]

For a more complete analysis of the impact of Dodd-Frank Act on broker-dealers, see our prior alert entitled, The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act from the Broker-Dealer’s Perspective.

B. Financial Crisis

During the second half of 2010, the SEC continued to pursue significant cases related to the financial crisis.

In July 2010, the SEC filed a settled action against Citigroup Inc. and several of its officers. The SEC’s complaint alleged that Citigroup represented that its sub-prime exposure was approximately $13 billion and declining, when its exposure was allegedly over $50 billion.[58] The disclosures omitted two categories of assets backed by sub-prime products, including “super senior” tranches of CDOs and “liquidity puts,” which accounted for approximately $43 billion in additional sub-prime exposure. Without admitting or denying the SEC’s allegations, Citigroup agreed to a settlement including a $75 million penalty. As part of their settlements, the executives agreed to pay $100,000 and $80,000, respectively, and both consented to the issuance of an administrative cease and desist order.

The initial settlement as to Citigroup was rejected by the district court.[59] However, in October 2010 the court accepted a second proposed settlement that contained the same monetary penalty but also ordered that remedial disclosure procedures Citigroup had initiated would remain in place.[60]

Also in July 2010, Goldman Sachs settled the SEC’s previously filed complaint concerning disclosures made in connection with the sale of a collateralized debt obligation.[61] Without admitting or denying the allegations of the complaint, Goldman agreed to pay $550 million, acknowledged that the marketing materials for the CDO were incomplete and agreed to review its approval processes for the offering of certain mortgage securities.

C. Sales Practices

The SEC continued its trend of pursuing actions against registered broker-dealers and associated persons who defraud elderly[62] and vulnerable investors.[63] In addition, in August 2010, the SEC and FINRA jointly released a set of best practices when dealing with elderly investors which includes better training, education, internal practices, and review mechanisms for the participating broker-dealer. [64]

D. Supervision

In a significant litigation decision, on September 8, 2010, SEC Chief Administrative Law Judge Murray issued an initial decision dismissing claims against the respondent, a former general counsel of a major regional brokerage firm in a case regarding the application of the “failure to supervise” provisions of Section l5(b)(4)(E) of the Exchange Act to chief legal officers of brokerage firms and investment advisers.[65] The Division of Enforcement alleged that the respondent had failed reasonably to supervise a registered representative who allegedly manipulated the price of a security and separately was alleged to have engaged in unsuitable and excessive trading in the accounts of retail customers. Relying on the SEC’s Section 21(a) report in In Re Gutfreund, 51 S.E.C. 983 (1992), Chief Judge Murray found that the broker was subject to Urban’s supervision, but concluded that Urban was not liable because his conduct was reasonable. The Division petitioned for Commission review of the initial decision. Urban filed a conditional cross petition arguing that the broker was not subject to his supervision, a position which is supported by the Association of Corporate Counsel, the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association, and the National Society of Compliance Professionals as amici curiae. The Commission accepted both petitions for review but has not set a date for oral argument or decision.

E. Microcap Stock Abuse

In October 2010, the SEC charged over a dozen penny stock promoters and their companies with securities fraud in connection with their participation in illegal kickback schemes aimed at manipulating the price and volume of microcap stocks and illegally generating stock sales.[66] These schemes, brought to light through FBI undercover operations, involved the payment of kickbacks to brokers or pension fund managers who used client accounts to buy publicly traded stock of microcap issuers promoted or controlled by the defendants. Some of the defendants also face criminal charges.

V. Public Company Accounting and Financial Reporting

A. Subprime Mortgage Related Cases

The Commission reached several significant settlements with public companies relating to their financial disclosures leading up to and during the financial crisis of 2008.

As noted above, in October 2010, the SEC settled an action first brought in June 2009 against Countrywide CEO Angelo Mozilo for alleged misstatements made in relation to Countrywide’s exposure to subprime mortgages.[67] Mozilo consented to a $22.5 million penalty. The SEC alleged in its complaint that Countrywide misled investors in its 2005–07 annual reports by promoting its risk management and quality control over mortgages, while at the same time Mozilo was allegedly issuing internal warnings about the high level of risky assets the company held and was referring to its subprime products as “toxic.”[68] Mozilo’s settlement with the SEC also permanently prohibits him from serving as an officer or director of a publicly traded company.[69] Countrywide’s former Chief Operating Officer and CFO also consented to settlements.

The second half of 2010 additionally marked several settlements in connection with the SEC’s case as to New Century, once one of the country’s largest subprime lenders. In July 2010, the Commission accepted settlement offers from the company’s co-founder and former CEO, former CFO and former controller.[70]

B. Third-Party Liability

In a decision with implications for the SEC’s ability to charge aiding and abetting liability, the federal district court in Connecticut dismissed the SEC’s aiding and abetting complaint against Joseph Apuzzo, the CFO of Terex Corporation. The SEC’s complaint alleged that Apuzzo assisted the CFO of United Rentals, Inc. (“URI”) to artificially inflate URI’s revenues by participating in roundtrip transactions. URI entered into “minor sale-leasebacks” with another third party, and Apuzzo executed contracts with the third party to guarantee the re-sale price of the equipment subject to the leaseback. URI agreed to indemnify Terex for any losses incurred to the third party. In order to recoup its payments to the third party, Terex submitted inflated equipment invoices to URI.

The SEC alleged that Apuzzo knew that the purpose of the agreements was to artificially inflate URI’s revenue and that he substantially assisted the scheme by committing Terex to various agreements and submitting false invoices. The court, however, found that Apuzzo could not have “substantially assisted” the scheme if he was not a proximate cause of URI’s violations. The court noted that while Apuzzo was a knowing and willing participant, he was not a driving force of the scheme, had no power to authorize URI’s conduct, was not ultimately responsible for URI’s accounting, and had no duty to disclose the agreements to URI’s auditor. The court’s application of the “proximate causation” analysis to aiding and abetting liability could prove to be a limiting factor in the SEC’s future pursuits against third parties.

C. Executive Compensation Clawbacks

The SEC continued to make use of the clawback remedy under section 304 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act to recover executive compensation from senior executives following restatements by corporations resulting from misconduct. In prior alerts we have discussed the significant cases in which the SEC has for the first time asserted the clawback remedy against executives who are not charged with any misconduct. In the second half of 2010, the SEC exercised the clawback remedy in a settlement with corporate executives of Navistar International Corporation.[71] In 2007, Navistar restated its earnings for fiscal years 2002–04, correcting 16 items in all. While certain other executives settled to charges of fraud, the CEO and former CFO settled only to allegations of causing the company’s failure to maintain a reasonable system of internal accounting controls. In the settlement, the CEO and CFO agreed to return to the company their 2004 bonuses.

In 2011, expect executive compensation clawbacks to become an even more common occurrence, as the Dodd-Frank Act expanded the scope of section 304. Under ? 304, the clawback applied only to CEOs and CFOs. Now, pursuant to ? 954 of the Dodd-Frank Act, the SEC can obtain clawback remedies against any current or former executive of the restating company.

D. Other Financial Disclosure Cases

In July 2010, the SEC filed a settled action against Dell, Inc. and several of its officers for allegedly misstating earnings and failing to disclose certain information.[72] The SEC alleged that Dell failed to disclose payments received from a supplier for not using components produced by the supplier’s competitor, which the SEC alleged enabled Dell to meet earnings estimates. The SEC also alleged the improper use of reserves to cover earnings shortfalls. As part of the settlement, Dell agreed to pay a $100 million penalty. Michael Dell, the company’s Chairman and CEO, and Kevin Rollins, the former CEO, each consented to a $4 million penalty, and former CFO James Schneider consented to a $3 million penalty.

The Commission charged several other companies and executives with violations resulting from financial misstatements. In July 2010, the SEC commenced a settled action against Sunrise Senior Living, Inc. and two of its officers for allegedly making improper adjustments to its reserve for health and dental benefits, thereby misstating earnings.[73]

In August 2010, the SEC filed charges against International Commercial Television and its former CFO, claiming the company improperly and prematurely recognized revenue for sales of a skin care product on the Home Shopping Network before they were actually sold or delivered to customers.[74] The SEC alleged that the company also recognized revenue from sales before the expiration of its free trial period and did not reverse revenue from products that had been returned. The company settled for a $1.1 million penalty.

Finally, the SEC filed charges against LocatePlus Holdings Corporation in October 2010 for allegedly misstating its reported revenue in 2005 and 2006 by improperly recognizing millions of dollars of revenue from a fictitious client.[75]

E. Vendor Payment Claims and Revenue Recognition

The SEC pursued several financial misstatement cases in late 2010 involving revenue recognition and vendor payments. The most significant was against Vitesse Semiconductor Corporation and four of its former senior executives for alleged improper revenue recognition from 2001 to 2006.[76] According to the SEC complaint, the executives engaged in an “elaborate” channel stuffing scheme by recording invalid accounts receivable for product shipped at period end to its largest distributor even though the distributor had an unconditional right to return all of the product. The complaint alleged that the executives then masked the right of return through undisclosed side letters and oral agreements, failed to timely record credits to the invalid accounts receivable when the distributor returned the product, and misapplied other cash receipts to its aged accounts receivable to disguise the transactions. The company settled charges with the SEC and agreed to a $3 million penalty.

Parallel criminal securities fraud charges were separately filed against Vitesse’s founder and former CEO Louis Tomasetta and former CFO Eugene Hovanec, and the executives pleaded not guilty. Former CFO Yatin Mody and former director of accounting, Nicole Kaplan, pleaded guilty to securities fraud charges and are cooperating with the government.

Vitesse’s former Controller and CFO Yatin Mody and former Director of Accounting Nicole Kaplan also pled guilty to criminal charges of securities fraud. Mody and Kaplan also entered into a bifurcated civil settlement with the SEC, agreeing to disgorgement and injunctive relief and deferring a determination of whether additional penalties are appropriate.

F. Auditor Liability

The close of the year brought a decision in an administrative proceeding against an audit partner and audit manager, a decision that is notable for the fact that the ALJ found that the partner’s single negligent act did not warrant sanctions, while the audit manager’s conduct warranted a one-year bar.[77] The SEC alleged that the partner and manager, in their audit of AA Capital Partners, Inc. and AA Capital Equity Fund, LLP, failed to evaluate adequately a related party loan. Specifically, the company recorded a $1.92 million receivable for a loan made to a co-owner for AA Capital to pay personal taxes relating to AA Capital. In reality, there was no such tax liability, and the co-owner used the proceeds for other personal expenses. The auditors discussed the receivable with AA Capital’s CFO but did not perform additional procedures relating to the loan.

The ALJ found that the audit manager failed to obtain sufficient competent evidential matter regarding the loan and failed to exercise due care in evaluating the transaction. Given that the transfers were not in the ordinary course of AA Capital’s business, and given inconsistencies in the brief explanations provided, the ALJ found that the audit team should have done more to investigate. The ALJ also found that the auditors violated GAAP because the transaction should have been disclosed as a related party transaction. Ultimately, the ALJ concluded that the audit manager engaged in highly unreasonable conduct where circumstances warranted heightened scrutiny.

As to the audit partner, however, the ALJ found that his supervision and planning of the audit was adequate and reasonable under the circumstances. The ALJ found that the audit partner failed to question AA Capital’s disclosures, which omitted reference to the tax loan as a related-party receivable. But the ALJ found that the partner’s single mistake did not rise to the level of “highly unreasonable” conduct, especially given the level of professional judgment involved in evaluating disclosures.

[1] The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, Pub. L. 111-203, 124 Stat. 1376 (2010), hereinafter the “Dodd-Frank Act.”

[2] See Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher Client Alert, The Dodd-Frank Act Reinforces and Expands SEC Enforcement Powers (July 21, 2010).

[5] SEC Press Release No. 2010-213, SEC Proposes New Whistleblower Program under Dodd-Frank Act (Nov. 3, 2010), http://www.sec.gov/news/press/2010/2010-213.htm.

[6] Assoc. of Corp. Counsel Dec. 15, 2010 Letter to SEC, http://www.acc.com/advocacy/news/dodd-frank.cfm.

[7] Assoc. of Corp. Counsel Dec. 17, 2010 Follow-up Letter to SEC, http://www.acc.com/advocacy/news/dodd-frank.cfm.

[8] Business Roundtable Dec. 17, 2010 Letter to SEC, http://businessroundtable.org/news-center/business-roundtable-letter-to-sec-on-whistleblower-provisions.

[9] SEC Annual Report on Whistleblower Program (Oct. 2010), http://www.sec.gov/news/studies/2010/whistleblower_report_to_congress.pdf.

[10] SEC Press Release No. 2010-252, SEC Charges Former Carter’s Executive with Fraud and Insider Trading (Dec. 20, 2010), http://www.sec.gov/news/press/2010/2010-252.htm; SEC v. Elles, No. 1:10-CV-4118 (N.D. Ga. filed Dec. 20, 2010).

[11] The descriptions of SEC actions in this article are based on allegations made by the SEC in its charging documents and do not assume the truth of the facts alleged. Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, LLP represents various parties in certain of these matters. Thus, these descriptions do not reflect the positions of the firm, its lawyers or its clients.

[12] In re State of New Jersey, Admin Proc. No. 3-14009 (filed Aug. 18, 2010), http://www.sec.gov/news/press/2010/2010-152.htm.

[13] SEC Press Release No. 2010-239, SEC Charges Bank of America Securities With Fraud in Connection With Improper Bidding Practices Involving Investment of Proceeds of Municipal Securities (Dec. 7, 2010), http://www.sec.gov/news/press/2010/2010-239.htm.

[14] Report of Investigation Pursuant to Section 21(a) of the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934: Moody’s Investors Service, Inc., (Aug. 31, 2010) http://www.sec.gov/litigation/investreport/34-62802.htm.

[16] SEC Press Release No. 2010-197, Former Countrywide CEO Angelo Mozilo to Pay SEC’s Largest-Ever Financial Penalty Against a Public Company’s Senior Executive (Oct. 15, 2010), http://www.sec.gov/news/press/2010/2010-197.htm.

[17] SEC Press Release No. 2010-123, Goldman Sachs to Pay Record $550 Million to Settle Charges Related to Subprime Mortgage CDO (July 15, 2010), http://www.sec.gov/news/press/2010/2010-123.htm.

[19] Susan Pulliam et al., “U.S. in Vast Insider Trading Probe,” Wall St. J. (Nov. 20, 2010).

[20] E.g. Susan Pulliam, “Reluctant Analyst Pressured by the FBI,” Wall St. J. (Dec. 4, 2010); Katya Wachtel, “John Kinnucan Gets SEC Subpoena Over Galleon CEO’s Brother’s Hedge Fund,” Business Insider (Dec. 15, 2010).

[21] Susan Pulliam et al., “Hedge Funds raided in Probe,” Wall St. J. (Nov. 22, 2010).

[28] Memorandum Opinion and Order, U.S. v. Rajaratnam, No. 09 Cr. 1184 (RJH), 2010 WL 3219333, at *1 (S.D.N.Y. Nov. 24, 2010).

[35] See Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher Client Alert, Investment Advisers to Private Funds — Registration Under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 (Sept. 14, 2010), http://www.gibsondunn.com/Publications/Pages/InvestmentAdviserstoPrivateFunds-InvestmentAdvisersActof1940.aspx.

[36] In re Valentine Capital Asset Mgmt., Inc. and John Leo Valentine, Admin. Proc. No. 3-14072 (SEC Sept. 29, 2010), http://www.sec.gov/litigation/admin/2010/34-63006.pdf.

[37] SEC v. Mannion, No. 10-CV-3347 (N.D. Ga. filed Oct. 19, 2010); see also SEC Litig. Release No. 21699 (Oct. 19, 2010), http://www.sec.gov/litigation/litreleases/2010/lr21699.htm.

[38] SEC v. Southridge Capital Mgmt. LLC, No. 3:10-CV-1685 (D. Conn. filed Oct. 25, 2010); see also SEC Litig. Release No. 21709 (Oct. 25, 2010), http://www.sec.gov/litigation/litreleases/2010/lr21709.htm.

[39] In re Flannery, Admin Proc. No. 3-14081 (filed Sep. 30, 2010), http://sec.gov/litigation/admin/2010/33-9147.pdf.

[40] In re State St. Bank & Trust Co., Admin Proc. No. 3-13776 (filed Feb. 4, 2010), http://www.sec.gov/news/press/2010/2010-21.htm.

[41] Complaint, SEC v. Rattner, No. 10 Civ 8699 (S.D.N.Y. Nov. 18, 2010); see also SEC Litig. Release No. 21748 (Nov. 18, 2010), http://sec.gov/litigation/litreleases/2010/lr21748.htm.

[42] In re Carlson Capital, L.P., Admin. Proc. No. 3-14066 (SEC Sept. 23, 2010), http://www.sec.gov/litigation/admin/2010/34-62982.pdf.

[44] SEC v. Grabler, No. 1:10-cv:10798 (D. Mass. filed May 11, 2010); SEC v. Leonard Adams, No. 1:10-cv:10799 (D. Mass. filed May 11, 2010).

[45] SEC v. New Castle Funds LLC, Admin. Proc. No. 3-14135 (Nov. 22, 2010), http://www.sec.gov/litigation/admin/2010/34-63358.pdf.

[46] SEC v. Gartmore Inv., Ltd., Admin. Proc. No. 3-14154 (Dec. 7, 2010), http://www.sec.gov/litigation/admin/2010/34-63460.pdf.

[47] SEC v. Venetis, No. 10-CV-4493 (D.N.J. filed Sept. 2, 2010); see also SEC Litig. Release No. 21641, http://www.sec.gov/litigation/litreleases/2010/lr21641.htm.

[49] In re Greenberg, Admin. Proc No. 3-14033 (SEC Sept. 7, 2010), http://www.sec.gov/litigation/admin/2010/33-9139.pdf.

[50] SEC v. Pre’vost, No. 10-cv-04235-PAM-SRN (D. Minn. filed Oct. 14, 2010); see also SEC Litig. Release No. 21694, http://www.sec.gov/litigation/litreleases/2010/lr21694.htm.

[53] The fiduciary standard was not imposed by statute but by case law. See Transamerica Mortgage Advisors, Inc. v. Lewis, 444 U.S. 11, 17 (1979) (“Indeed, the Act’s legislative history leaves no doubt that Congress intended to impose enforceable fiduciary obligations.”)

[54] Elizabeth M. Murphy, Secretary, SEC, “Study Regarding Obligations of Brokers, Dealers, and Investment Advisers” (Jul. 27, 2010), http://www.sec.gov/rules/other/2010/34-62577.pdf.

[55] Mary L. Schapiro, Chairman, SEC, “Testimony on Implementation of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission” (Sep. 30, 2010), http://www.sec.gov/news/testimony/2010/ts093010mls.htm.

[56] Mary L. Schapiro, Chairman, SEC, “Testimony on Implementation of Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission” (Sep. 30, 2010), http://www.sec.gov/news/testimony/2010/ts093010mls.htm.

[57] Mary L. Schapiro, Chairman, SEC, “The Next Phase in Financial Regulatory Reform” (SEC Jul. 27, 2010), http://www.sec.gov/news/speech/2010/spch072710mls.htm.

[58] SEC v. Citigroup Inc., Civil Action No. 1:10-CV-01277 (ESH) (D.D.C. July 29, 2010); see also Litig. Release No. 21605 (July 29, 2010), http://www.sec.gov/litigation/litreleases/2010/lr21605.htm.

[59] Transcript of Status Hearing, SEC v. Citigroup Inc., No. 1:10-cv-01277 (ESH) (D.D.C. filed Aug. 20, 2010).

[61] SEC v. Goldman, Sachs & Co. and Fabrice Tourre, Civil Action No. 10 Civ. 3229 (S.D.N.Y. filed April 16, 2010); http://www.sec.gov/news/press/2010/2010-123.htm; see also Litig. Release No. 21489 (April 16, 2010), http://www.sec.gov/litigation/litreleases/2010/lr21592.htm.

[62] See SEC v. Moskop, No. 10C 7462, (N.D. Ill., Nov. 19, 2010), http://www.sec.gov/litigation/complaints/2010/comp21752.pdf.

[63] See SEC v. Imperia Invest IBC., No. 210-cv:00896 (D. Utah filed Oct. 06, 2010), http://www.sec.gov/litigation/complaints/2010/comp-pr2010-184.pdf.

[64] See SEC Press Release No. 210-147 (Aug. 13, 2010), http://www.sec.gov/news/press/2010/2010-147.htm.

[66] SEC v. Scott R. Sand and Ingen Tech., Inc, Civ. No. 1:10-cv-23602-PAS (S.D. Fla.); SEC v. Jeffrey Galpern, Civ. No. 1:10-cv-23603-JLK (S.D. Fla.); SEC v. Jean R. Charbit and Tzemach David Netzer Korem, Civ. No. 1:10-cv-23604-CMA (S.D. Fla.); SEC v. Anthony Mellone, Alex Parsinia, Larry Wilcox, Macada Holding, Inc. f/k/a Tri-Star Holdings, Inc., Zcom Networks, Inc., and The UC HUB Group, Civ. No. 1:10-cv-23609-JAL (S.D. Fla.); SEC v. Bruce Palmer and AccessKey IP, Inc., Civ. No. 1:10-cv-23601-DLG (S.D. Fla.); SEC v. John “Buckeye” Epstein, Steven E. Humphries, Earthworks Entertainment, Inc., and The Fight Zone, Inc. a/k/a Gold Recycle Corp., Civ. No. 1:10-cv-23606-AJ (S.D. Fla.); see also Litig. Release No. 21691 (Oct. 7, 2010), http://www.sec.gov/litigation/litreleases/2010/lr21691.htm.

[67] See SEC Press Release No. 2010-197 (Oct. 15, 2010), http://www.sec.gov/news/press/2010/2010-197.htm.

[69] See SEC Press Release No. 2010-197 (Oct. 15, 2010), http://www.sec.gov/news/press/2010/2010-197.htm.

[70] See SEC Litig. Release No. 21609 (July 30, 2010), http://www.sec.gov/litigation/litreleases/2010/lr21609.htm

[71] In re Navistar Int’l Corp., Admin. Proc. No. 3-13994 (filed Aug. 5, 2010), available at http://www.sec.gov/litigation/admin/2010/33-9132.pdf.

[72] SEC v. Dell Inc., No. 1:10-cv-01245 (D.D.C. filed July 22, 2010); see also SEC Litig. Release No. 21599 (July 22, 2010), http://www.sec.gov/litigation/litreleases/2010/lr21599.htm.

[73] SEC v. Sunrise Senior Living, Inc., No. 1:10-cv-01247 (D.D.C. filed July 23, 2010), http://www.sec.gov/litigation/complaints/2010/comp21600.pdf.

[74] SEC v. Int’l Commercial Television, Inc., No. 3:10-cv-05555 (W.D. Wash. filed Aug. 9, 2010); SEC v. Redekopp, No. 3:10-cv-05557 (W.D. Wash. Aug. 9, 2010); see also SEC Press Release No. 2010-146 (Aug. 9, 2010), http://sec.gov/news/press/2010/2010-146.htm.

[75] SEC v. LocatePlus Holdings Corp., No. 1:10-cv-11751 (D. Mass. Oct. 14, 2010), http://www.sec.gov/litigation/complaints/2010/comp21692.pdf.

[76] SEC v. Vitesse Semiconductor Corp., No. 10 CIV 9239 (JSR). (S.D.N.Y filed Dec. 10, 2010); see also SEC Litig. Release No. 21769 (Dec. 10, 2010), http://www.sec.gov/litigation/litreleases/2010/lr21769.htm; U.S. Atty. S.D.N.Y Press Release, “Two Former High-Technology Company Executives Charged in Manhattan Federal Court in Massive Accounting and Securities Fraud Scheme” (Dec. 10, 2010).

Gibson Dunn is one of the nation’s leading law firms in representing companies and individuals who face enforcement investigations by the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Department of Justice, the Commodities Futures Trading Commission, the New York and other state attorneys general and regulators, the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB), the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA), the New York Stock Exchange, and federal and state banking regulators.

Our Securities Enforcement Group offers broad and deep experience. Our partners include the former Director of the SEC’s prestigious New York Regional Office, a former Associate Director of the SEC’s Division of Enforcement, the former Director of the FINRA Department of Enforcement, the former general counsel of the PCAOB, the former United States Attorney for the Central District of California, and former Assistant United States Attorneys from federal prosecutor’s offices in New York, Los Angeles, and Washington, D.C.

Securities enforcement investigations are often one aspect of a problem facing our clients. Our securities enforcement lawyers work closely with lawyers from our Securities Regulation and Corporate Governance Group to provide expertise regarding parallel corporate governance, securities regulation, and securities trading issues, our Securities Litigation Group, and our White Collar Defense Group.

Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these developments. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you work or any of the following:

New York

Mark K. Schonfeld (212-351-2433, [email protected])

Joel M. Cohen (212-351-2664, [email protected])

Lee G. Dunst (212-351-3824, [email protected])

Barry R. Goldsmith (212-351-2440, [email protected])

George A. Schieren (212-351-4050, [email protected])

Alexander H. Southwell (212-351-3981, [email protected])

Jim Walden (212-351-2300, [email protected])

Lawrence J. Zweifach (212-351-2625, [email protected])

Washington, D.C.

John H. Sturc (202-955-8243, [email protected])

David P. Burns (202-887-3786, [email protected])

K. Susan Grafton (202-887-3554, [email protected])

Los Angeles

Michael M. Farhang (213-229-7005, [email protected])

Douglas M. Fuchs (213-229-7605, [email protected])

Palo Alto

Timothy Roake (650-849-5382, [email protected])

Paul J. Collins (650-849-5309, [email protected])

Denver

George B. Curtis (303-298-5743, [email protected])

Dallas

M. Byron Wilder (214-698-3231, [email protected])

© 2011 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.