January 19, 2016

While massive mergers and pharmaceutical pricing dominated industry headlines in 2015, the U.S. Government continued to shape the drug and device industries through enforcement actions and other regulatory activities this past year. The U.S. Department of Justice (“DOJ”) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”), in particular, pursued drug and device companies–and, in some instances, individual executives at those companies–for a variety of alleged misconduct. Meanwhile, FDA continued to push current priority goals such as developing more efficient pathways to market for many drugs and devices and promoting greater cybersecurity protections for medical devices. But the second half of 2015 also saw important developments pushing back on FDA’s regulatory authority; another federal court invalidated FDA’s efforts to police truthful off-label promotion, and congressional and industry stakeholders explored alternative schemes for oversight of laboratory developed tests (“LDTs”).

Amidst all of this action, the past year’s legislative stagnation was especially evident–with one notable exception. We reported in our 2015 Mid-Year FDA and Health Care Compliance and Enforcement Update on Drugs and Devices (“2015 Mid-Year Update”) that the U.S. House of Representatives passed the 21st Century Cures Act, but the last six months saw little (if any) legislative progress. In the meantime, federal and state legislators toyed with several proposals designed to increase government involvement in drug prices.

Below, we discuss the past six months’ developments in the regulation of both drugs and devices. As in past updates, we begin with an overview of government enforcement efforts against drug and device companies under the False Claims Act (“FCA”), the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (“FDCA”), and other laws. We then address evolving regulatory guidance and action on topics of note to drug and device companies: promotional activities, manufacturing practices, product development, and the Anti-Kickback Statute (“AKS”). We also detail certain developments of particular note to device manufacturers, before summarizing the pharmaceutical pricing issues that drew significant attention in 2015.

I. DOJ Enforcement in the Pharmaceutical and Medical Device Industries

DOJ enforcement actions in the drug and device industries have continued apace during the second half of 2015. As detailed below, the DOJ has continued its active pursuit of drug companies and device manufacturers and sellers in criminal and civil actions, employing the FCA, the FDCA, and the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (“FCPA”).

In the midst of these actions against companies, the DOJ also found time to issue a new policy memorandum regarding its plans to pursue individuals in corporate fraud cases. Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates signed the memorandum, entitled “Individual Accountability for Corporate Wrongdoing” (the “Yates Memorandum”), on September 9, 2015.[1] As we have observed in other publications,[2] the Yates Memorandum proclaims that the DOJ plans to combat corporate misconduct by “fully leverag[ing] its resources to identify culpable individuals at all levels in corporate cases.”[3]

With that commitment in mind, the Yates Memorandum delineates six steps to identify and punish individual perpetrators. Most notably, the DOJ intends to condition the availability of “any cooperation credit” whatsoever (in both criminal and civil cases) on whether the company under investigation provides the DOJ with “all relevant facts about the individuals involved in corporate misconduct.”[4] Further, the DOJ will immunize individuals as part of a corporate resolution only in “extraordinary circumstances” and will not resolve corporate cases absent a “clear plan to resolve related individual cases before the statute of limitations expires.”[5]

In recent speeches, various DOJ officials have echoed elements of the Yates Memorandum. For example, Deputy Assistant Attorney General Jonathan Olin noted in a December 9, 2015 speech that “individual accountability is at the heart of [DOJ’s] corporate enforcement strategy.”[6] To that end, attorneys at the DOJ’s Consumer Protection Branch–and throughout the Department–are “look[ing] more critically at every corporate case and ensur[ing] that those responsible for the wrongdoing are identified early and pursued.”[7]

If, as the DOJ has pledged, the government ramps up its pursuit of individuals, the types of enforcement actions detailed below will become all the more complex from a legal (and strategic) perspective for drug and device companies.

A. Civil Actions / False Claims Act

This past year was even busier than last for the DOJ in FCA matters involving drug and device companies, with fifteen resolutions totaling more than $650 million in recoveries. FCA whistleblowers, or relators, continue to press these cases: all but one of the enforcement actions this year began with a qui tam complaint. As Principal Deputy Assistant Attorney General Benjamin C. Mizer noted in an October 2015 speech, relators served 469 qui tam complaints alleging some form of health care fraud on the DOJ in Fiscal Year 2014, and those qui tam suits led to “93 percent of the health care fraud matters opened by the Civil Division.”[8]

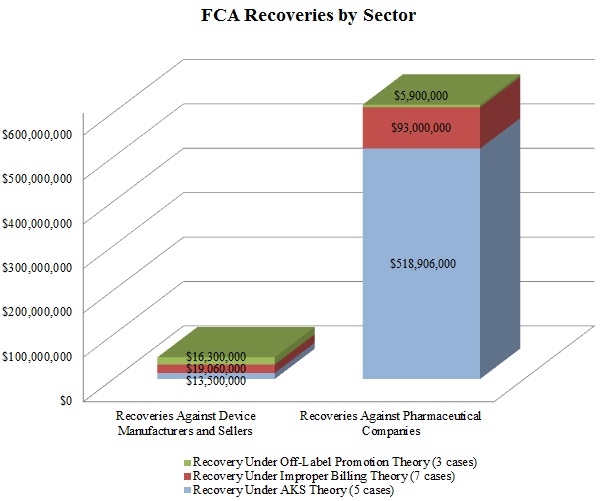

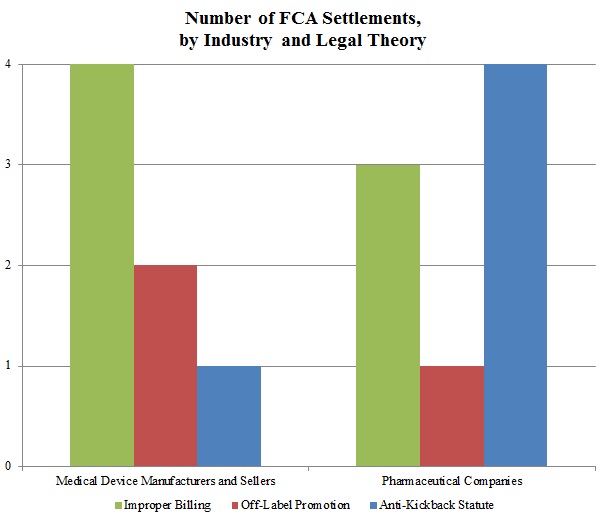

In keeping with a trend noted in our 2015 Mid-Year Update, the DOJ continued to advance AKS theories in many of these settled matters. As the chart below shows, resolutions involving AKS allegations resulted in the vast majority of the DOJ’s recoveries in 2015 from drug and device companies. Settlements predicated on allegations of improper billing came in a distant second in terms of recovery amounts during the past year.

In a significant departure from years past, resolutions premised on off-label promotion theories lagged far behind: the DOJ announced settlements of just three cases involving off-label allegations against drug and device companies in 2015, representing less than $23 million in recoveries. Given the scale of the government’s recoveries in off-label cases in past years–in 2014, for example, off-label recoveries totaled nearly ten times the 2015 off-label recoveries[9]–this data point is remarkable. It remains to be seen in 2016 and beyond whether this departure from typical off-label recovery levels reflects industry-wide enhancements to compliance programs following a wave of major enforcement actions, the effect of the Caronia and Amarin cases limiting the government’s ability to police promotional speech, or simply a short-term shift of priorities for the DOJ.

Settlements in AKS-Related FCA Matters. As detailed in Part V below, the AKS prohibits offering or providing remuneration to induce sales or referrals of products or services covered by federal health programs. In recent years, the DOJ and private whistleblowers have pursued, with some notable success, ever-broader theories under the AKS, resulting in new complexity for those companies seeking to comply with the statute (or navigate a government investigation or FCA litigation).

In the largest of the AKS-related FCA settlements during the second half of 2015, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation agreed to pay $390 million to resolve civil claims focusing on the company’s allegedly improper relationships with specialty pharmacies.[10] According to the DOJ, Novartis provided discounts and rebates to specialty pharmacies dating back to 2004 to incentivize increased sales of Novartis drugs.[11] Even before its resolution with Novartis, the DOJ had recovered a total of $75 million from two specialty pharmacies involved in the alleged misconduct.[12] In keeping with the government’s growing focus on specialty pharmacies–and drug companies’ relationships with them–Novartis submitted to oversight of its relationships with the pharmacies and to independent annual review as part of an addendum to its existing Corporate Integrity Agreement, which will be extended for five years.[13] Novartis’ Corporate Integrity Agreement stemmed from the company’s 2010 resolution of a DOJ investigation, under which it agreed to pay $422.5 million to resolve criminal and civil liability related to alleged off-label promotion and kickbacks provided to healthcare professionals.[14]

In late October 2015, Warner Chilcott PLC agreed to pay $125 million to resolve criminal and civil allegations that it, among other purported misconduct, violated the AKS and the FCA.[15] According to the government, Warner Chilcott caused the submission of false claims by paying kickbacks to physicians through speaker programs, meals, “Medical Education Events,” and other forms of remuneration and by manipulating prior authorizations and other coverage requests to induce insurance companies to pay for prescriptions of its osteoporosis drugs.[16] The civil component of this settlement comprised more than $102 million of the total amount.[17] We address the criminal AKS component of Warner Chilcott’s global resolution in Part V, below.

Resolution of Off-Label Promotion Investigation. In the lone announced resolution of an off-label case of the past six months, medical device manufacturer NuVasive, Inc. agreed to pay $13.5 million to resolve allegations that it caused health care providers to submit false claims by marketing the company’s CoRoent System for unapproved surgical uses.[18] The settlement also resolved claims related to alleged kickbacks offered through promotional speaker fees, honoraria, and expenses for events to induce physicians to use the company’s surgical system in spine fusion surgeries.[19] Although an independent society sponsored the events at issue, the government alleged that NuVasive actually created, funded, and operated the society.[20]

Settlements of Cases Based on Other False Claims Theories. The remaining enforcement actions of the latter half of the year involved different types of allegations of fraudulent practices with respect to government payment. Pharmaceutical companies AstraZeneca LP and Cephalon Inc. agreed to pay $46.5 million and $7.5 million, respectively, to resolve allegations that the companies underpaid rebates owed under the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program.[21] Pursuant to the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program, drug manufacturers must pay quarterly rebates to state Medicaid programs based in part on their reported Average Manufacturer Prices (“AMPs”) for each of their drugs under Medicaid, and higher reported AMPs generally correspond with obligations to pay higher rebates for those drugs. According to the DOJ, both companies underreported their AMPs after allegedly reducing those numbers improperly for service fees paid to wholesalers.[22] Biogen, Inc. also agreed to settle with the relator, who reported that Biogen paid $1.5 million to resolve the allegations.[23]

These settlements partially resolve a larger case, United States ex rel. Streck v. Allergan, Inc., et al., No. 08-cv-5135 (E.D. Pa.). The Streck case originally involved several additional defendants. But, on July 3, 2012, the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania dismissed claims against multiple defendants in Streck in part or in their entirety, depending on the type of claim.[24] Relator’s claims against defendants AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, L.P., Biogen Idec, Inc., Cephalon, Inc., and Genzyme Corp. were dismissed in relation to all AMP submissions to the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program which occurred before January 1, 2007.[25] The court concluded that before that date, when a statutory change to the definition of AMP took effect, there was little statutory guidance for companies regarding what discounts companies could include in their calculations of AMP.[26] Thus, the court held that the relator failed to plead sufficient facts to show that Defendants’ “interpretation of the statutory and regulatory scheme was unreasonable, let alone that [] Defendants’ interpretation raised ‘the unjustifiably high risk’ of violating the statute necessary for reckless liability” under the FCA.[27]

The court also dismissed in their entirety relator’s claims against Defendants Allergan, Inc.; Amgen, Inc.; Bradley Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eisai, Inc.; Mallinckrodt, Inc.; Novo Nordisk, Inc.; Reliant Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Sepracor, Inc.; and Upsher-Smith Laboratories, Inc.[28] Relator alleged that these Defendants agreed “to report a lower AMP by concealing price increases and preventing such price increases from being considered in the AMP calculation.”[29] But the court concluded that the relevant statute did not provide guidance to companies until after relator filed his Fourth Amended Complaint.[30] Thus, relator pleaded no facts that would have allowed the court to determine that “Defendants’ price credit methods were not a reasonable interpretation of AMP.”[31] After the court’s dismissal of certain claims–and the recent settlements–only one defendant, Genzyme Corp., remains in the case.

In the last action of the year, Vintage Pharmaceuticals, LLC, d/b/a Qualitest Pharmaceuticals, corporate parent Endo Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and several corporate subsidiaries and affiliates agreed to pay $39 million to settle allegations that drugs manufactured by Qualitest did not meet federal requirements.[32] The DOJ alleged that Qualitest had manufactured and sold understrength chewable fluoride tablets to children living in communities without fluoridated water from 2007 to July 2013 and thereby violated the FCA.[33]

B. FDCA Enforcement Actions

DOJ enforcement efforts under the FDCA have remained steady as well throughout 2015, including several civil and criminal actions brought in the last six months. Like many of the cases from the first half of 2015, these actions involved allegations of marketing unapproved and misbranded products.[34] In several of the actions detailed below, the government focused on the defendant’s purported failures to correct violations cited in inspections and Warning Letters issued to the companies.

1. Marketing Unapproved and Misbranded Drugs and Devices

In June 2015, the U.S. District Court for the District of New Jersey entered a permanent injunction barring drug manufacturer Acino Products LLC and its president from distributing allegedly unapproved and misbranded drugs.[35] The complaint alleged that the manufacturer’s hydrocortisone acetate suppositories were not approved by FDA and were misbranded because the company failed to include adequate directions for use.[36] Notably, FDA alleged that it conducted at least three inspections of the company’s facility in 2014 and early 2015; in addition, in May 2014, the government seized certain suppositories manufactured by Acino but distributed by another company.[37] According to the government’s complaint, Acino continued to manufacture the products despite learning of the allegedly unapproved uses as a result of the seizure and FDA’s post-inspection discussions with the company’s president.[38]

In September 2015, Genzyme Corporation, a wholly owned biotechnology subsidiary of Sanofi, agreed to pay $32.5 million to resolve criminal charges that it violated the FDCA in connection with the alleged unlawful distribution of its surgical device Seprafilm between 2005 and 2010.[39] The DOJ alleged that Genzyme sales representatives taught medical staff to convert the adhesion barrier pieces into liquid “slurry”–a new medical device without FDA approval–and that the company made misleading claims in a promotional brochure.[40] To resolve the government’s adulteration and misbranding charges, the company admitted responsibility for certain facts underlying the charges and agreed to implement a revamped, comprehensive internal compliance program as part of a two-year Deferred Prosecution Agreement.[41] Notably, Genzyme had entered into a separate civil settlement (and paid approximately $22 million) to resolve allegations related to the same surgical device nearly two years before the criminal resolution.[42]

In our 2015 Mid-Year Update, we reported on proceedings before the U.S. District Court for the District of South Dakota against an individual and his medical device businesses for marketing and selling laser devices without FDA approval.[43] The defendants allegedly distributed lasers with false and misleading labeling claims relating to treatment for serious conditions like cancer, HIV/AIDS, and diabetes.[44] This past October, the court entered a permanent injunction against the defendants, in which the court ordered the recall, destruction, and refund of all devices distributed by the defendants since 2001.[45]

In a related case filed by the same individual, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit held that distributing medical devices through private membership associations “does not exempt” those devices from the FDCA.[46] The individual had been seeking a declaratory judgment challenging FDA’s authority to execute administrative warrants to inspect his laser-device business. Affirming the district court’s dismissal of the action, the court rejected his argument that FDA lacked regulatory jurisdiction over his marketing of the devices because he distributed the lasers through private membership associations in non-commercial transactions.[47]

2. Marketing without Approval and cGMPs

The second half of 2015 was quiet in terms of DOJ enforcement of current Good Manufacturing Practices (“cGMP”) rules. In August 2015, the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Iowa entered a permanent injunction against drug and dietary supplement company Iowa Select Herbs LLC and its principals to prevent the distribution of allegedly adulterated, unapproved, and misbranded products.[48] According to the government’s complaint, FDA issued an April 2014 Warning Letter to the company after inspectors found multiple violations of the cGMP regulations for dietary supplements.[49] An August 2014 follow-up inspection allegedly demonstrated that Iowa Select Herbs had failed to remediate the issues.[50] The government alleged that the company’s supplements were adulterated due to the continuing cGMP violations.[51] In addition, the government asserted that the company marketed its supplements as treatments for several medical conditions even though the company never sought FDA approval for those products (and thus FDA had never found the company’s products safe and effective for their promoted uses).[52]

C. FCPA Investigations

The government brought only one FCPA enforcement action involving a drug or device company during the last six months of 2015. As detailed in Gibson Dunn’s 2015 Year-End FCPA Update, the SEC announced a settled FCPA proceeding against Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. (“BMS”), a global pharmaceutical company, in October 2015.[53] According to the SEC, BMS was the majority owner of a joint venture that employed sales representatives who made improper payments (including cash, gifts, meals, travel, entertainment, and sponsorships for conferences and meetings) to health care professionals in China to generate additional prescriptions.[54] Without admitting or denying the allegations, BMS agreed to the entry of a cease-and-desist order and to pay approximately $14.7 million in disgorgement, prejudgment interest, and civil penalties.[55]

Lest anyone think that FCPA enforcement involving drug and device companies is on the wane, there is a lengthy list of publicly disclosed FCPA investigations involving companies in these industries–and some of those investigations may well lead to future enforcement actions. For example, Massachusetts-based medical imaging company Analogic Corp. announced in December 2015 that it may have to pay as much as $15 million to the DOJ and the SEC to settle alleged FCPA violations tied to transactions involving the company’s Danish subsidiary and certain foreign distributors.[56] According to the filings, the SEC rejected the company’s original settlement offer of $1.6 million.[57] The company voluntarily disclosed the activity after learning of transactions in which its subsidiary allegedly received extra payment from distributors and then transferred those extra funds to third parties at the distributors’ direction.[58] Although the company was “unable to ascertain with certainty the ultimate beneficiaries or the purpose of these transfers,” it terminated certain employees and its relationships with the distributors involved.[59]

II. Promotional Issues

The second half of 2015 reflected the increasing impact that landmark First Amendment legal challenges–including the suits that led to the Second Circuit’s decision in Caronia and the Southern District of New York’s decision in Amarin, as well as Pacira Pharmaceuticals Inc.’s subsequent suit against FDA[60]–have had on the regulatory landscape surrounding truthful promotional speech by drug and device makers. Nevertheless, these legal victories for the industry have been incremental and limited in scope, and U.S. regulators are sure to remain vigilant in enforcing laws restricting promotional activities, perhaps even increasing enforcement in certain areas such as electronic promotions. Below, we address several developments in this area, including the success of the most recent First Amendment challenge to FDA’s promotional enforcement.

A. FDA Enforcement Activity – Advertising and Promotion

FDA letters relating to advertising and promotional issues in 2015 continued to reflect a downward trend in overall enforcement but an uptick in response to electronic communications seen in the past few years. This past year, FDA’s Office of Prescription Drug Promotion (“OPDP”) issued just nine total letters (seven Untitled Letters and two Warning Letters), one fewer than in 2014.[61] Three OPDP letters pertained to physical promotional materials like professional sales aids and pharmacology aids, three focused on traditional websites, one targeted social media postings, and one concerned a video segment. FDA’s actions suggest that it will continue to regulate both traditional and online promotional activities in 2016 and beyond.

Among the most notable OPDP actions in the latter half of 2015 were the following:

- August 7, 2015 Warning Letter Regarding Kim Kardashian Social Media Posts: In an August Warning Letter, OPDP took the unprecedented step of targeting promotional statements made by a celebrity on behalf of a drug manufacturer on her social media sites.[62] In the letter, OPDP warned that Ms. Kardashian’s Instagram and Facebook posts touting the results of a morning sickness drug for pregnant women were “false or misleading” because they presented efficacy claims without communicating risk information.[63] OPDP concluded that the social media posts misbranded the drug in violation of the FDCA and ordered the manufacturer not only to remove the posts but also to disseminate corrective messages to the same audience.[64] The letter signals FDA’s belief that drug promotions on popular social media accounts may warrant additional corrective advertising beyond deleting the misleading advertisement.

- July 24, 2015 Withdrawal of Pacira Pharmaceuticals Warning Letter: In July, FDA took the exceedingly rare step of closing out, or withdrawing, a September 2014 Warning Letter against Pacira Pharmaceuticals, Inc.[65] The Warning Letter had cautioned the company against distribution of materials describing the use of a drug as a post-surgical analgesic for any surgical procedures other than a limited set already approved by FDA.[66] Subsequent to the withdrawal, Pacira filed a claim on First Amendment grounds to prevent FDA from bringing an enforcement action against the company for what Pacira claims is truthful and non-misleading promotion of its drug.[67] In December, the same day the parties entered into a settlement agreement, FDA sent a letter to Pacira explaining the rationale for the rescission of its Warning Letter.[68]

In the second half of 2015, FDA also responded to Congressman Tim Murphy (R-PA), who, in a May 27, 2015 letter, criticized FDA’s use of Untitled Letters as vehicles for policy changes and for their potential impact on publicly traded companies (among other complaints).[69] Although FDA offered few specific details in its response, the agency asserted that it does “not use Untitled Letters as a way to announce new regulatory approaches or policies”[70] and that it “does not believe the Agency has a special expertise or a mission to change its own processes [for issuing and posting Untitled Letters] to attempt to time impacts on the stock market.”[71] It remains to be seen whether FDA’s response has assuaged Congressional concerns or whether Congress will continue to press FDA about its use of Untitled Letters.

B. FDA’s Promotional Guidance

As in 2014, and despite FDA claims that reforms are on the horizon, this year once again ended without comprehensive changes to FDA policies to better comport with First Amendment protections for promotional speech.[72] Although the industry has enjoyed some success on this front in the courts, it will have to wait until at least 2016 to enjoy the “greater regulatory clarity” that FDA believes will result from its ongoing “comprehensive” review.[73]

While conducting its comprehensive review, FDA issued few guidance documents relating to promotional practices in 2015. As we reported in our 2015 Mid-Year Update, FDA issued revised draft guidance in February 2015 regarding disclosure of risk information in drug promotions in an effort to ensure that consumers can “make informed decisions about the medication being promoted.”[74] The draft guidance provided and recommended an alternative approach for consumer-directed prescription drug print advertisements and promotional labeling called a “consumer brief summary,” which would “focus on the most important risk information rather than an exhaustive list of risks and [present information] in a way most likely to be understood by consumers.”[75]

C. Notable Litigation Relating to Promotional Issues

1. Off-Label Promotion and the First Amendment

On August 7, 2015, the pharmaceutical industry achieved its most compelling First Amendment victory over FDA since the Second Circuit’s landmark decision in United States v. Caronia recognized constitutional protection for truthful, non-misleading off-label promotional speech.

Relying on the Caronia decision, the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York in Amarin Pharma, Inc. v. U.S. Food & Drug Administration concluded that the First Amendment bars FDA from pursuing a misbranding action under the FDCA based on “truthful and non-misleading speech promoting the off-label use of an FDA-approved drug.”[76] The court entered a preliminary injunction permitting Amarin to engage in off-label promotion of its fish oil drug, Vascepa, after finding that Amarin’s proposed statements were truthful and non-misleading based on currently available information.[77] The court also suggested appropriate language for Amarin to use to ensure that the contested disclosures and statements conveyed a truthful and non-misleading message.[78]

The Amarin court rejected FDA’s attempts “to marginalize the holding” in Caronia “as fact-bound,” emphasizing instead that Caronia‘s holding is “a definitive one of statutory construction,” which explicitly “‘declined to adopt the government’s construction of the FDCA’s misbranding provisions'” to prohibit truthful off-label speech.[79] The court also rebuffed FDA’s efforts to moot the case. During the litigation, FDA sent Amarin a letter acknowledging that while some of the statements “fall within the scope” of existing FDA guidance, Amarin would need to meet certain additional conditions before FDA would agree not to bring a misbranding action.[80] The district court concluded that, rather than mooting the case, the letter solidified the existence of an actionable case or controversy because FDA’s threat of a misbranding action chilled the expression of Amarin’s First Amendment rights.[81]

Although drug and device companies may welcome Amarin, the court specified several limits on the First Amendment protection afforded to off-label promotion. First, the court noted that the First Amendment protects expression, not conduct, concluding that “Caronia does not limit the Government’s ability to use promotional speech to establish intent in a misbranding action with a proper actus reus,” such as where a defendant also “paid doctors money or bought them resort vacations.”[82] The court also underscored that the First Amendment does not protect false or misleading commercial speech.[83] Finally, the court urged manufacturers to heed the “practical wisdom” contained in “much of FDA guidance” and cautioned that companies should “ensure that their communications remain truthful and non-misleading in the future as new studies are done and new data is acquired.”[84] Although the combined effect of the rulings in Amarin and Caronia appears to foreclose FDA from targeting truthful and non-misleading off-label promotion for prosecution, this precedent is thus far limited to the Second Circuit and considerable uncertainty remains as to how other courts may rule in similar circumstances.

Amarin’s victory quickly inspired what will likely be the first of many more First Amendment challenges to FDA restriction of off-label promotion. In September, Pacira Pharmaceuticals, Inc. filed suit in the Southern District of New York seeking an injunction preventing FDA from bringing an enforcement action against the company for truthful and non-misleading (but off-label) promotional speech concerning its non-opioid pain drug.[85] As noted above, Pacira sued FDA after it issued a Warning Letter to Pacira last year. Although FDA withdrew the Warning Letter before Pacira filed the lawsuit, the litigation proceeded until the parties settled this past December.[86]

As part of the resolution, FDA issued a letter formally rescinding its Warning Letter and confirming that the use, efficacy and safety of Pacira’s drug is not limited to any specific surgery type or site.[87] At the request of Pacira, the Rescission Letter also included FDA guidance related to the scope of the indication as to key specific surgical procedures.[88] FDA also approved a labeling supplement clarifying that the drug is, and has been since 2011, broadly indicated for administration into the surgical site to provide postsurgical analgesia and approved effectiveness duration claims that had been disputed in the lawsuit.[89] This appears to represent a resounding victory for Pacira.

D. Legislative Developments

As we reported in our 2015 Mid-Year Update, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a version of a bill entitled the 21st Century Cures Act, which, among other things, would require FDA to issue draft guidance to facilitate the dissemination of scientific and medical information not otherwise included on drug labels, as long as the information is responsible, truthful, and non-misleading.[90] Since then, however, Congress has made little progress in enacting the 21st Century Cures Act into law. Although the Senate is working on its own version of the legislation, the language of the bill may be narrower in terms of FDA reforms than the version passed by the House.[91] What this will mean for the provisions of the bill aimed at loosening restrictions on promotional activity remains to be seen in the upcoming year.

III. Developments in cGMP Regulations and Other Manufacturing Issues

Under the FDCA, FDA has promulgated cGMP regulations for drug products and the quality system regulation (“QSR”) for medical devices. Compliance with these highly technical rules is critical; violations can serve as the basis for both civil and criminal enforcement actions even if the products at issue do not actually pose a safety risk to consumers. Below, we address key developments from 2015 in cGMP and QSR regulation and enforcement.

A. 2015 cGMP and QSR Compliance and Enforcement Trends

1. cGMP- and QSR-Based Warning Letters

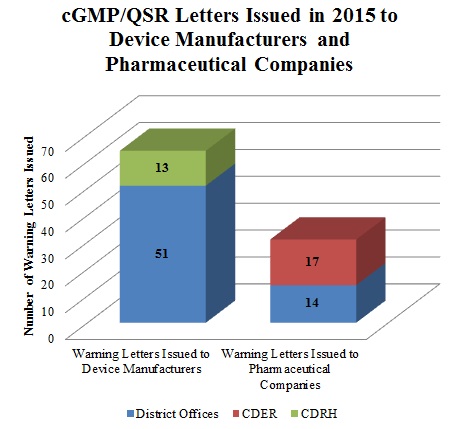

Although the total number of Warning Letters for cGMP/QSR violations in 2015 decreased from 2014, cGMPs will likely continue to be a significant focus of FDA’s enforcement efforts. In 2015, at least thirty-one FDA Warning Letters issued to companies involved in the manufacture and/or compounding of drugs cited violations of cGMP regulations. The Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (“CDER”) issued the majority of these letters (seventeen), while the remaining letters came from district offices (fourteen). Medical device manufacturers were cited even more frequently for cGMP violations; FDA issued at least sixty-four Warning Letters categorized as cGMP/QSR-related. The district offices issued fifty-one of these letters while the Center for Devices and Radiological Health (“CDRH”) sent the remainder.

2. Ranbaxy Challenges FDA’s Authority to Revoke Tentative Generic Approvals and Exclusivity Due to Alleged Lack of Compliance with Manufacturing Regulations

As we reported in our 2014 Year-End Update, the DOJ achieved its “largest drug safety settlement to date with a generic drug manufacturer” when a U.S. subsidiary of Ranbaxy Laboratories Limited agreed to pay a criminal fine and forfeiture totaling $150 million related to manufacturing issues at two of its facilities located in India.[93] Ranbaxy also settled related civil claims under the FCA and similar state laws for $350 million.[94] On November 14, 2014, Ranbaxy filed suit in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, requesting declaratory and injunctive relief against FDA and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (“HHS”) in response to FDA’s November 4, 2014 decision to strip Ranbaxy of its tentative Abbreviated New Drug Application (“ANDA”) approvals for two generic drugs.[95] Although Ranbaxy asserted that FDA lacked authority for its action, the District Court granted FDA summary judgment, ruling that FDA acted within its authority by conditioning Ranbaxy’s tentative ANDA approvals on compliance with cGMPs and by withdrawing Ranbaxy’s 180-day generic-drug exclusivity when Ranbaxy was unable to bring its generic to market.[96]

Ranbaxy appealed, but Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Ltd., which acquired Ranbaxy in March,[97] agreed to dismiss the appeal with prejudice in October.[98] Consequently, the question of whether FDA has the legal right to revoke 180-day generic-drug exclusivity remains unanswered.

3. Specialty Compounding Enters a Consent Decree Related to Alleged cGMP Violations

2015 saw at least two significant consent decrees imposing permanent injunctions on drug and device makers. As we reported in our 2015 Mid-Year Update, the DOJ filed a consent decree imposing a permanent injunction on Medtronic Corporation related to alleged QSR violations.[99] Similarly, in March, the DOJ filed a consent decree imposing a permanent injunction on Specialty Compounding LLC and its two owners due to alleged issues with the drug maker’s sterile drugs, such as injectable calcium gluconate.[100] According to the government, FDA received seventeen complaints in August 2013 of adverse events experienced by patients treated at two Texas hospitals with intravenous infusions of calcium gluconate manufactured by Specialty Compounding.[101] In August 2013, Specialty Compounding ceased manufacturing sterile drugs and initiated a voluntary nationwide recall of its sterile drug products.[102] According to FDA, an inspection of Specialty Compounding’s manufacturing facility between August 13 and September 13, 2013, revealed the contamination of a lot of injectable calcium gluconate with five different types of bacteria, unsanitary conditions, and other evidence of cGMP violations.[103]

Under the consent decree, Specialty Compounding must stop manufacturing sterile drugs until the facility passes a comprehensive inspection by an independent drug compliance expert.[104] However, after FDA inspections in March, April, and May 2015, FDA issued another Form 483 to Specialty Compounding identifying cGMP issues and asserting that the pharmacy still had not adequately prevented contamination and other hazards to sterile drugs.[105]

B. cGMP Rulemaking and Guidance Activity

July 2015 saw a flurry of FDA activity regarding cGMP compliance. FDA released a rule requiring that certain drug and biologics manufacturers warn FDA of discontinuances or supply interruptions. Similarly, FDA released a draft guidance announcing its intention to collect additional quality control information from pharmaceutical companies. FDA also released final guidance regarding recommended analytical procedures for product approval applications.

1. Information Reporting

On July 8, FDA released its final rule–now in effect–requiring applicants of certain drugs and biological products to notify FDA electronically of a permanent discontinuance or interruption in production likely to lead to a meaningful disruption in supply.[106] FDA believes that this rule will improve its ability to identify potential drug shortages and allow it to prevent or mitigate the impact of such shortages.[107] Applicants are required to notify FDA at least six months prior to the date of permanent discontinuance or interruption in manufacturing if the drug or biological product is a prescription product that is life supporting, life sustaining, or intended for use in the prevention or treatment of a debilitating disease or condition.[108] FDA will issue noncompliance letters to applicants who fail to notify FDA under the rule.[109]

The same month, FDA released draft guidance announcing its intention to collect data from owners and operators of establishments required to register under section 510 of the FDCA and engaged in the manufacture, preparation, propagation, compounding, or processing of finished drug forms of covered drug products or active pharmaceutical ingredients used in the manufacture of covered drug products.[110] FDA stated that it plans to request information (including the number of out-of-specification results for the product, number of specification-related rejected lots of the product, and number of product complaints) when the guidance is finalized.[111] Although the guidance may impose additional reporting burdens on some manufacturers, companies with tightly controlled manufacturing processes and quality management systems may benefit from such reporting in the form of fewer agency inspections.

2. Analytical Procedures for Application Approval

Also in July, FDA released its final guidance concerning the submission of analytical procedures and methods validation data to support drugs’ identity, strength, quality, purity, and potency for new drug applications (“NDAs”), ANDAs, biologics license applications (“BLAs”), and supplements to these applications.[112] According to FDA’s definition, analytical procedures test defined characteristics of drugs against established acceptance criteria for those characteristics.[113] FDA recommends that drug companies continue analytical procedures for the life cycle of a drug and maintain an appropriate number of retention samples for this purpose.[114] As part of the NDA and ANDA approval process, FDA may conduct laboratory assessments to determine whether a company’s analytical procedures are acceptable.[115] Although the final guidance does not apply to investigational new drug (“IND”) applications, FDA suggests that IND sponsors consider these guidance recommendations.[116]

IV. Medical Devices

The second half of 2015 has seen significant activity in some of the key areas identified by CDRH as strategic priorities in early 2014. Perhaps most notably, FDA has continued down its controversial path toward expanding its reach under the Medical Device Amendments of the FDCA with active regulation of LDTs. FDA also recently signaled that it intends to scrutinize cybersecurity issues with medical devices. At the same time, CDRH has continued to push a number of initiatives to streamline its processes to get more innovative devices to market more quickly, through improvements in timeliness of application reviews and other measures. Finally, with the 2014-2015 period coming to a close, CDRH announced its strategic priorities for 2016 and 2017.

A. 2015 Device Approvals and Clearances

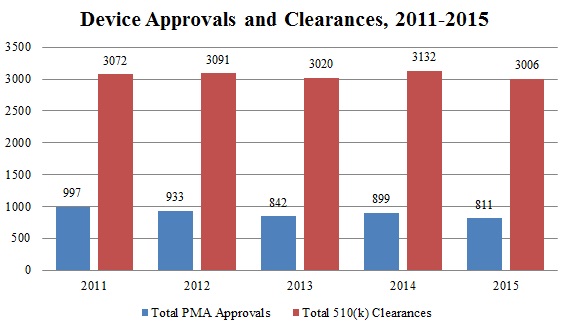

Since July 1, FDA has approved 534 Premarket Approval (“PMA”) applications–including twenty-four original PMA applications[117]–and granted 1494 510(k) clearances.[118] This brings the annual totals for 2015 to 1,162 PMA approvals, a notable increase over approval totals in previous years, and 3,006 510(k) clearances, in line with the number of clearances in recent years.

Source: Food and Drug Administration Center for Devices Radiological Health[119]

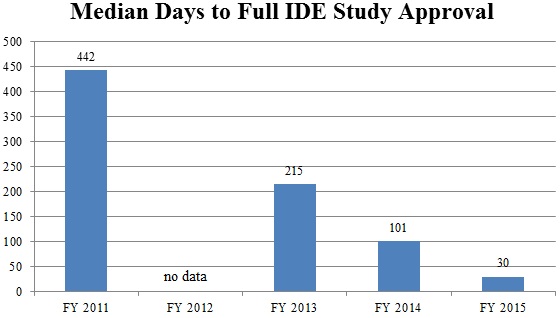

Continuing a trend of improvement from recent years, CDRH announced in September that it has made significant progress in decreasing the average review time for Investigational Device Exemption (“IDE”) decisions.[120] In its strategic priorities for 2014 and 2015, CDRH pledged, among other things, to “strengthen the clinical trial enterprise” by enhancing the efficiency and predictability of the IDE process.[121] CDRH recently showed how it has made good on this promise. In September, CDRH staff announced that “[f]rom 2011 to 2014, the median number of days to full IDE approval decreased from 442 days to 101 days,” and “[d]uring 2015, the median number of days to full IDE approval has decreased to 30 days.”[122] In addition to dramatically decreasing IDE approval time, CDHR also has decreased the number of review cycles necessary, with 74% of IDEs approved in two review cycles in 2015, compared to only 15% of IDEs in 2011.[123] Because IDE approval is an important prerequisite for the use of a new device in clinical trials as part of the PMA process, this is a welcome development for device manufacturers seeking to begin marketing innovative devices sooner.

Source: Food and Drug Administration Center for Devices Radiological Health[124]

B. Recent Developments in the Regulation of LDTs

LDTs are clinical diagnostic tests that are designed, manufactured, and used in a single laboratory.[125] These tests may be developed by a hospital, academic, or clinical laboratory, according to its own procedures, often to diagnose conditions for which there is no FDA-approved test-kit and for which there is thus an unmet clinical need (e.g., for uncommon illnesses). Historically, FDA has taken the position that LDTs are in vitro diagnostics that qualify as “devices” under the FDCA. But, in years past, the agency exercised its enforcement discretion in this area, declining to regulate LDTs because, it claimed, LDTs were developed and performed in small volumes at the time of the Medical Device Amendments to the FDCA.[126] As LDTs have proliferated and become more complex in recent years, exposing increasing numbers of patients to potential risk, FDA has become increasingly interested in active regulation of LDTs.

In October 2014, FDA released two draft guidance documents declaring the agency’s intention to exercise greater regulatory authority over LDTs and outlining the regulatory framework it envisions using in more actively regulating LDTs.[127] As we outlined in the 2014 Year-End Update, FDA proposed a tiered, risk-based approach to LDT regulation, in which LDTs would be classified like other devices (Class I, Class II, or Class III). The agency would expect laboratories to abide by registration, listing, and manufacturer reporting requirements immediately upon final guidance becoming effective, and FDA would phase in pre-market review and quality system regulation requirements on a risk-based timeline thereafter over the course of approximately nine years.[128]

FDA recently stated that it has now reviewed all public comments submitted on the 2014 draft guidance documents and that the agency is on target to release final guidance on LDT regulation in 2016.[129] In the meantime, however, FDA has continued to debate its intended actions with industry stakeholders, and Congress has joined the fray. In October, the House Energy and Commerce Committee released a “discussion draft” of potential legislation providing a regulatory framework for the review of LDTs that, if enacted, would preempt FDA’s plan.[130] The proposed bill would establish a new in vitro center within FDA–but outside of CDRH–to oversee the premarket approval for LDTs. The Committee’s proposal would empower FDA to review LDTs in a manner distinct from the medical device approval process. Additionally, the draft legislation would allow the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (“CMS”) to maintain its focus on post-market assessment of laboratory practices and quality standards.

On November 16, FDA released a report titled “The Public Health Evidence for FDA Oversight of Laboratory Developed Tests: 20 Case Studies.”[131] The report provided twenty examples of LDTs that “may have caused or have caused actual harm to patients,” and employed these examples to illustrate the risks of potential problems in LDTs that are not prevented by a laboratory’s compliance with existing laws and regulations.[132] Among other purported problems, FDA focused on false positives or false negatives, or a combination of false positives and negatives; measurement of a factor seemingly unrelated to the disease in question; links to treatments based on disproven scientific concepts; and even the adverse impact of LDTs on the drug approval process, in which NDA clinical research relies on the results of insufficiently validated LDTs.[133] The report also contended that the absence of FDA oversight of LDTs leads to deficient adverse event reporting, no premarket review of performance data, unsupported manufacturer claims, inadequate product labeling, lack of transparency, and an uneven playing field in which LDT producers who do seek premarket review are placed at an unfair disadvantage.[134]

Finally, on November 17, the House Energy and Commerce Committee Subcommittee on Health held a hearing on LDTs, which featured testimony from CDRH Director Jeffrey Shuren and CMS Chief Medical Officer Patrick Conway. At the hearing, Dr. Shuren testified that FDA plans to move forward with final guidance in 2016, despite the draft legislation the Committee released in October and trade groups’ preparations to challenge FDA’s legal basis for regulating LDTs as medical devices.[135] Significantly, Dr. Conway also explained that CMS is not interested in responsibility for assessing the clinical validity of LDTs; because CMS “does not have a scientific staff” that can make those assessments, CMS would defer to FDA, “which assesses clinical validity in the context of premarket reviews and other activities aligned with their regulatory efforts” under the FDCA.[136]

As the debate about regulatory oversight of LDTs rages on–and stakeholders increasingly contemplate legal challenges to the proposed regulation–it is likely that 2016 will see key developments in the regulatory environment.

C. FDA Response to Cybersecurity Vulnerabilities of Medical Devices

In the past six months, FDA also has blazed new ground in its response to revelations of serious cybersecurity vulnerabilities of a Hospira medication infusion pump. This summer, when independent researchers notified FDA that hackers could commandeer and control the administration of medication through the Hospira pump, FDA responded with unprecedented action.[137] On July 31, the agency issued a safety communication urging facilities using the Hospira pump to discontinue use of the system and transition to an alternative infusion system.[138] Although Hospira no longer marketed the pump for unrelated reasons, FDA also urged healthcare providers not to purchase any Symbiq pump which might be available from third parties.[139]

According to FDA, this marked the first time it has specifically recommended against the use of a medical device due to cybersecurity risks. FDA’s actions signal strongly that the agency will take cybersecurity defects in medical devices as seriously as any other product defect, with enforcement measures likely to follow.

D. FDA Guidance

The second half of 2015 saw a number of guidance documents from FDA on a wide range of issues. We summarize the most notable guidance documents issued during the past six months below.

1. Intent to Exempt Certain Devices from Premarket Notification Requirements

This summer, CDRH released a final guidance document deeming 128 types of medical devices “sufficiently well understood” that they therefore “do not require premarket notification (510(k)) to assure their safety and effectiveness.”[140] The device types are divided among eleven medical areas, and include devices ranging from dentures to operating room lamps. The guidance document states FDA’s intent to exempt these devices with an Unclassified, Class II, or Class I Reserved classification, through a formal rule or order and declares that the agency will not enforce compliance with 510(k) for these devices even before the formal exemption is complete.

“[A]s part of the re-authorization process for the Medical Device User Fee Amendments of 2012, FDA committed to identifying low-risk medical devices to exempt from premarket notification requirements”;[141] these guidance documents and the August 2014 draft guidance that they superseded are important steps in fulfilling that commitment.

2. Guidance Documents to Improve Timeliness of CDRH Review

Two guidance documents released in the second half of 2015 reflect FDA’s ongoing efforts to improve the efficiency and timeliness of submission reviews. In August, CDRH and the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (“CBER”) released a final guidance document laying out a detailed checklist of updated criteria by which 510(k) clearance applications should be assessed for administrative completeness within the first fifteen days of receipt and rejected if found incomplete.[142] Like the 2012 guidance that it superseded as of October 1, the 2015 “Refuse to Accept Policy for 510(k)s” guidance is aimed at “encouraging quality submissions from submitters of 510(k) notifications and allowing FDA to appropriately concentrate resources on complete submissions.”[143] The new Refuse to Accept (“RTA”) guidance permits FDA staff to “request missing checklist items interactively from submitters during the RTA review,” creating more flexibility and reviewer discretion than previously existed in the RTA process.[144] Other key changes from the 2012 version involve the shortening and clarifying of the checklists provided for assessing the administrative completeness of the file.

In December, CDRH and CBER also released a final guidance document titled “eCopy Program for Medical Device Submissions.”[145] The eCopy guidance requires medical device sponsors to submit a complete electronic copy (in addition to a paper copy) of their applications for CDRH review and to abide by certain technical specifications for the eCopy submission.[146] This efficiency-promoting requirement applies broadly: FDA has only exempted compassionate use IDE submissions, emergency use IDE submissions, adverse event reports, and Emergency Use Authorizations from the eCopy requirements.[147]

3. Animal Studies for Medical Devices

In October, CDRH released the draft guidance document “General Considerations for Animal Studies for Medical Devices.”[148] Acknowledging that studies in animals are often the best means of assessing medical device safety and efficacy before testing in humans, the guidance document provides recommendations to ensure that animal studies are as efficient, valid, and useful as possible. The draft guidance addresses, among other topics: study planning, protocol, and methods; the personnel that should be involved; the nature of the facilities to be used for testing and housing the animals; record-keeping and reports; and the preparation of regulatory submissions. FDA also noted its willingness to engage in pre-submission review of animal study design to ensure that the animal studies are valid and useful to the agency.[149]

4. Manufacturing Site Change Supplements

Also in October, CDRH and CBER jointly issued draft guidance on manufacturing site change supplements.[150] The draft guidance provides information on when a manufacturer of a device with an approved PMA, a product development protocol, or a humanitarian device exemption must issue a PMA “site change supplement” if the manufacturer changes the location in which the device is manufactured. Currently, if a PMA site change supplement is required, the manufacturer must wait until FDA approves the supplement–which may take up to 180 days–before changing the manufacturing location. If a PMA site change supplement is not required, the device manufacturer must only provide a 30-day notice to FDA before introducing devices made under different manufacturing conditions to the market.[151]

Under the draft guidance, FDA would require a site change supplement when (1) the manufacturing “site was not approved as part of any original PMA; or (2) where the site(s) was approved as part of an original PMA, but only for the performance of different manufacturing activities” that do not involve similar processes or technologies as those involved in the new task.[152] The draft guidance provides a list of thirteen points of information that FDA recommends the device manufacturer include in the supplement to show that QSR requirements are met at the new site.[153] A pre-approval inspection may also be required in certain circumstances, such as where the new site has no history of inspection or has not been inspected in the last two years.[154] The draft guidance also clarifies that if the change is only to the manufacturing location of a component piece that goes into a finished project, no PMA site change supplement is necessary, but a 30-day notice will be necessary where the component is considered critical and the modification affects the device’s safety or effectiveness.[155]

5. Electromagnetic Compatibility of Electrically Powered Medical Devices

In November, CDRH issued draft guidance addressing what information the manufacturer of an electrically powered medical device should submit in its premarket applications to support claims that their device is able to function properly in its intended electromagnetic environment with immunity from interference by other devices and without introducing excessive electromagnetic emissions that might interfere with other devices.[156] The draft guidance provides a detailed outline of nine categories of information that should be provided to substantiate claims of electromagnetic compatibility and facilitate premarket review.

E. Strategic Priorities for 2016-2017

As we look back at the developments of 2015, CDRH has just announced three strategic priorities for 2016 and 2017. First among these is the development of a National Evaluation System for Medical Devices that would capture and utilize real-world electronic health information to inform regulatory decision-making regarding devices.[157] To achieve this goal, by the end of 2017 CDRH intends to gain access to 100 million electronic patient records with device identification and “increase the number of premarket and postmarket regulatory decisions that leverage real-world evidence” by 100% compared to 2015 levels.[158]

As a second strategic priority for 2016-2017, CDRH has committed to “partner with patients” and increase patient feedback and preferences in the clinical trial and device approval processes.[159] In the next two years, CDRH aims to create new mechanisms to obtain patient input so that by the end of 2017 90% of CDRH employees will interact with patients as part of their job duties and 100% of PMA, de novo, and Humanitarian Device Exemption decisions will consider and incorporate patient perspective data.[160]

Finally, CDRH has also announced its commitment to “promot[ing] a culture of quality and organizational excellence.”[161] To achieve this goal, FDA will focus on internal quality improvements through education and training and also develop “metrics, successful industry practices, standards, and tools” to allow device manufacturers to evaluate product and manufacturing quality beyond regulatory requirements.[162] We will continue watching FDA’s efforts in these areas closely in the months ahead and report on its progress towards achieving these strategic priorities in future updates.

V. Anti-Kickback Statute

Generally speaking, the AKS makes it illegal for drug and device companies (among others) to knowingly and willfully offer or provide anything of value to health care providers to induce those providers to use or prescribe a company’s product.[163] Among other potential consequences, both criminal and civil penalties can result from violations of the AKS.[164]

There are a slew of statutory exceptions and regulatory safe harbors associated with the AKS, but companies must tread carefully in this territory. Indeed, for years, many of the heftiest settlements and judgments announced by the government in matters involving drug or device companies have been based on alleged violations of the AKS. This year was no exception; both the $390 million Novartis settlement and $125 million Warner Chilcott settlement (discussed above) involved allegations of AKS violations. Because the government’s and private relators’ theories of AKS liability are often expansive (and occasionally counter-intuitive), companies large and small should have an in-depth understanding of the types of conduct that can spawn sprawling investigations and lawsuits predicated on the AKS.

In addition to the enforcement actions discussed in Part I of this Year-End Update, two developments from the second half of 2015 underscore the complicated issues and high stakes associated with efforts to adhere to the AKS.

A. HHS OIG Guidance

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General (“HHS OIG”) routinely releases advisory opinions in response to queries posed by companies attempting to comply with the AKS and its many nuances. Those advisory opinions provide useful insight into how HHS OIG analyzes companies’ potential marketing and promotional activities.

In August 2015, HHS OIG analyzed and opined on a pharmaceutical company’s plan to provide a drug free of cost to patients who experience a delay in the insurance approval process.[165] FDA had approved the drug, a highly specialized therapy for cancer patients, for certain indications under the agency’s Breakthrough Therapy Designation.[166] Working with a specialty pharmacy, the company that sought HHS OIG’s opinion created a program to supply certain patients with the drug if they met specified conditions.[167] Under the company’s proposal, the patients had to (1) be a new patient; (2) have received a prescription for the drug; (3) have an on-label diagnosis; (4) be insured (e.g., by a commercial insurer or a federal health care program); and (5) have experienced a delay in a coverage determination of at least five business days.[168] The company proposed to provide the patients up to two months’ free supply of the drug.[169] But the company certified that it would not market the program directly to consumers or allow the patients to continue buying the drug from the specialty pharmacy partner after those two months, even in the event that the patient’s insurer never approved continued use.[170]

Based on these facts, HHS OIG concluded that the program would not violate the AKS because of the very limited scope of the program and certain structural safeguards against any inducement of referrals. In particular, HHS OIG took comfort in the highly specialized nature of the cancer drug and the expectation that patients would pay substantial cost-sharing–at another pharmacy–after the free trial expired.[171] HHS OIG also distinguished the program from “seeding” programs–where a manufacturer offers a trial period to induce continued use–on the grounds that the company did not plan to market the drug directly to consumers, the drug was highly specialized, and the program would only apply in “those rare cases in which insurance approval decisions extend beyond five business days.”[172] Under these circumstances, HHS OIG opined that the program would be “unlikely to influence patients or prescribers to choose the Drug over alternative therapies, particularly where . . . the alternatives are limited.”[173] HHS OIG also noted that the program would entail no cost to federal health care payors, and that the other parties to the arrangement had nothing to gain: prescribers received no payment and the patients could not continue using the specialty pharmacy after their insurance kicked in.[174]

HHS OIG’s opinion reflects the complex, fact-intensive inquiries that may be involved in ensuring AKS compliance. But it also is a reminder that companies may be able to find novel ways to provide products to patients who need them while complying with the AKS.

B. Criminal AKS Liability

On the other end of the enforcement spectrum, the DOJ announced a high-profile criminal prosecution of a pharmaceutical executive alleged to have conspired to violate the AKS.

As noted above, in October, Warner Chilcott PLC pled guilty to felony criminal charges stemming from, among other alleged misconduct, paying kickbacks to physicians in the form of meals and “Medical Education Events.”[175] Under the plea agreement, Warner Chilcott will pay a $22.94 million criminal fine.[176]

The DOJ also charged W. Carl Reichel, Warner Chilcott’s former President, with one count of conspiring to pay kickbacks to physicians.[177] According to the government, Reichel conspired to have Warner Chilcott employees induce physicians to prescribe the company’s drugs through meals and other remuneration purportedly provided in connection with “Medical Education Events.” The government alleged that those events involved dinners, lunches, and receptions at expensive restaurants but had little to no educational content.[178]

This prosecution comes on the heels of the DOJ’s September 2015 Yates Memorandum regarding the prosecution of individuals in corporate fraud cases.[179] The Yates Memorandum and the subsequent prosecution of Mr. Reichel may well be a harbinger of more aggressive enforcement of the AKS in years to come.

VI. Drug Development and Clinical Trials

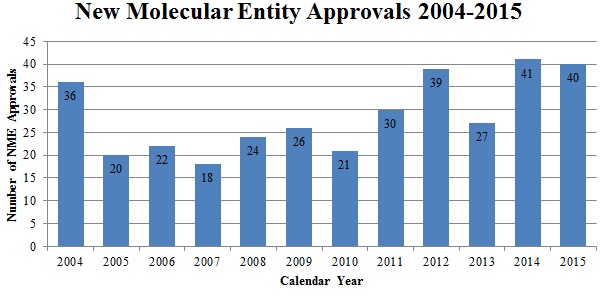

This past year saw forty new drug approvals–one less than the record-breaking number of 2014 and the third-highest in history.[180]

Source: U.S. Food & Drug Admin., Ctr. for Drug Eval. & Research

Source: U.S. Food & Drug Admin., Ctr. for Drug Eval. & Research

As this number of approvals suggests, the government continues to focus on streamlining drug approvals to make more products available to patients quickly. In July 2015, FDA released a White Paper which acknowledges that “the length and cost of the earlier discovery and testing stages must be improved” and describes the various tools FDA uses to reduce the length and cost of clinical trials.[181] FDA also discussed the “state of scientific knowledge and its effect on drug developments” in four key disease areas: (1) Alzheimer’s disease; (2) diabetes; (3) rare diseases; and (4) hepatitis C.[182] The government also is working to increase the efficiency of clinical trials by promoting patient engagement through a public-private partnership, the Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative, which launched in 2007 and includes FDA, Duke University, and other organizations. In October 2015, the partnership released its recommendations to improve the reliability of, and patient engagement in, clinical trials.[183] Relatedly, FDA sought industry and other public comment on how to improve clinical trials using technologies and innovative methods.[184] These comments will aid FDA in drafting additional guidance documents that further improve the efficiency of clinical trials and quicken the drug approval process.

A. Guidance on Improving Clinical Trials and Drug Approvals

In the second half of 2015, FDA issued four draft and four final guidance documents aimed at increasing the efficiency of clinical trials. In addition, HHS and fifteen other federal agencies announced a notice of proposed rule-making concerning the protection of human subjects engaged in research activities under the Common Rule. We briefly survey these developments below:

- Guidance on Common Issues in Drug Development for Rare Diseases: In August 2015, FDA released its draft guidance addressing common issues that arise in the development of orphan drugs for rare diseases.[185] According to FDA, the “guidance is intended to assist sponsors of drug and biological products for the treatment of rare diseases in conducting more efficient and successful development programs through a discussion of selected issues commonly encountered in rare disease drug development.”[186] Given the limited number of individuals suffering from any one rare disease, FDA acknowledges that “certain aspects of drug development that are feasible for common diseases may not be feasible for rare diseases.”[187] The draft guidance advises manufacturers to obtain an in-depth understanding of the rare disease’s “natural history.”[188] Because “[r]are diseases are highly diverse,” the agency wrote, “[s]election of the data elements to collect in a natural history study should be broad.”[189] The draft guidance also reminds manufacturers that the statutory requirement for marketing approval (“substantial evidence” that the drug will have its claimed effect) remains the same for common and rare diseases.[190]

- Guidance on Product Development under the Animal Rule: On October 28, 2015, FDA released its final guidance regarding product development under the Animal Rule.[191] By way of background, in 2002, FDA promulgated the Animal Efficacy Rule (often called the Animal Rule), which allows drug developers, in certain circumstances, to demonstrate efficacy through the use of animal, rather than human, subjects in clinical trials.[192] FDA’s recent guidance clarifies that “[a]pproval under the Animal Rule can be pursued only if human efficacy studies cannot be conducted because the conduct of such trials is unethical and field trials after an accidental or deliberate exposure are not feasible.”[193] The guidance advises manufacturers on how to design animal efficacy studies and lays out certain criteria that must be met to reasonably expect efficacy testing in animals to provide a reliable indicator of how the drug will perform in humans.[194]

- Guidance on Analytical Procedures and Methods Validations for Drugs and Biologics: As discussed previously in Part III, in July 2015, FDA issued its long-awaited guidance regarding “how to submit analytical procedures and methods validation data to support the documentation of the identity, strength, quality, purity, and potency of drug substances and drug products, and how to assemble information and present data to support analytical methodologies.”[195] This detailed guidance applies to NDAs, ANDAs, and BLAs and is aimed at further promoting efficiencies in product development.[196]

- Guidances on Controlled Correspondence and Good Clinical Practices: In September, FDA issued its final guidance on controlled correspondence related to generic drug development and a draft guidance on good clinical practices in light of the International Conference on Harmonization.[197] FDA’s guidance on controlled-correspondence demonstrates the agency’s intent to facilitate the development of generic-drug products by improving communication with generic-drug manufacturers.[198] Controlled correspondence is defined by FDA as “[a] correspondence submitted to the Agency, by or on behalf of a generic drug manufacturer or related industry, requesting information on a specific element of generic drug product development.”[199] The guidance details how to submit controlled correspondence and clarifies how FDA reviews and responds to it.[200]FDA issued its guidance on good-clinical-practice “under the auspices of the International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH)”; the guidance builds on prior guidance documents addressing topics related to efficient clinical trial design and human subject protection.[201] Specifically, the guidance provides an “international ethical and scientific quality standard for designing, conducting, recording, and reporting trials that involve the participation of human subjects.”[202]

- Guidance on Integrated Summary of Effectiveness: In October, FDA released its guidance regarding the inclusion of integrated summaries of drug effectiveness in NDAs and BLAs.[203] This final guidance emphasizes that the focus of an integrated summary of effectiveness should be “a comprehensive, integrated, in-depth analysis of the overall effectiveness results” rather than detailed results of individual studies.[204] Much like the analytical procedures and methods validation guidance mentioned above, this guidance is expected to streamline the drug approval process by standardizing (to a degree) drug-approval applications.

- Best Practices for Communication between IND Sponsors and FDA: Most recently, in December 2015, FDA issued draft guidance on best practices for communications between IND applicants and FDA during the various phases of drug development.[205] The guidance aims to facilitate meetings at critical junctures during drug development–at the pre-IND stage, prior to phase 2 and 3 trials, and prior to an NDA or BLA–to help manufacturers avoid wasting time and resources.[206]

In addition to the guidance activity discussed above, the HHS and fifteen other federal agencies announced a notice of proposed rule-making regarding the “Common Rule”–a uniform body of regulations, spanning numerous federal departments and agencies, concerning the protection of human research subjects.[207] First promulgated in 1991, the Common Rule applies fundamental humanitarian principles such as respect for persons, beneficence, and justice to research using human subjects.[208] Some of the major proposed changes to this rule are: (1) strengthening the informed consent documents; (2) increasing transparency; (3) creating information privacy protections; (4) regulating use of identifiable private information or bio-specimens; and (5) streamlining the review process to be more proportional to the seriousness of the potential harms involved.[209]

B. Developments in Biosimilar Approval Pathway Regime

As discussed in our last two updates, one government initiative to facilitate greater drug availability in the marketplace is the new approval pathway under the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (“BPCIA”), which allows for an “abbreviated licensure pathway for biological products that are demonstrated to be ‘biosimilar’ to or ‘interchangeable’ with an FDA-licensed biological product.”[210]

As reported in our 2015 Mid-Year Update, FDA approved the first biosimilar product Zarxio, a biosimilar to Amgen’s reference drug Neupogen, in the first half of this year. Although Zarxio remains the only biosimilar approved under the BPCIA, FDA received seven additional biosimilar applications in 2015.[211] Perhaps unsurprisingly (given FDA’s lack of guidance on the process and the complexity of these products), the agency has yet to receive an application under the interchangeability pathway.

1. New Guidance Releases

During a September 17, 2015 appearance before the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions, CDER Director Dr. Janet Woodcock vowed to put more resources into building the biosimilar review program.[212] Dr. Woodcock also updated the Committee on the status of forthcoming guidance documents, including “Considerations in Demonstrating Interchangeability to a Reference Product,” but failed to confirm a release date.[213] In the meantime, FDA issued two important biosimilar guidance documents in the second half of 2015:

- Guidance on Nonproprietary Naming of Biological Products: In August, FDA released its long-awaited draft guidance on the nonproprietary naming of biological products.[214] Under the guidance, biosimilars and their reference products are given names that consist of the “core name” given to the reference product by the U.S. Adopted Names Council and a unique four letter suffix. This approach highlights the fact that biosimilar products are different from their reference products because their complex nature makes them harder to replicate than drugs. As evidenced by some of the comments filed on this topic, many in the industry fear that these unique identifiers will serve as scarlet letters that convey a biosimilar’s inferiority to its reference product. The Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”), for one, has expressed concerns that the proposed rule might cause physicians to mistakenly believe that there are clinically meaningful differences between a biosimilar and its reference product, making them less inclined to prescribe the biosimilar, thereby undermining the government’s policy goals.[215]

- Guidance on Formal Meetings between FDA and Biosimilar Biological Product Sponsors or Applicants: In November 2015, FDA issued another piece of guidance providing recommendations to the industry on formal meetings between FDA and biosimilar biological product applicants to occur at various stages of the biosimilar application process.[216] The guidance also sets forth a number of topics for these meetings, from the initial feasibility of the biosimilar pathway to the content of a 351(k) product application.[217]

2. First Biosimilar Approval Litigation

This year also witnessed a landmark decision in the highly publicized patent litigation between Amgen and Sandoz surrounding FDA’s first biosimilar approval. Under the BPCIA’s abbreviated approval process, makers of biosimilar products can rely on clinical trial data developed by the manufacturer of the reference product.[218] But to balance innovation and competition, the BPCIA grants twelve years of data exclusivity to the reference product manufacturer,[219] who also can attempt to keep an FDA-approved biosimilar product off of the market by asserting claims of patent infringement. To that end, the BPCIA establishes a unique process of information exchange between the biosimilar applicant and the original product manufacturer to resolve patent disputes.[220]

This process, known as the “patent dance,” was the focal point of the litigation between Sandoz, the manufacturer of Zarxio, the first-approved biosimilar drug, and Amgen, the manufacturer of reference product Neupogen.[221] Amgen alleged that Sandoz was required under 42 U.S.C. § 262(l) to grant Amgen access to its confidential manufacturing plans and marketing application submitted to FDA no later than twenty days after FDA accepted its application for review.[222] This would have allowed Amgen to determine which of its patents may be violated by Sandoz’s development of Zarxio. However, despite the word “shall” in 42 U.S.C. § 262(l), the Federal Circuit held that disclosure of the information at issue is optional rather than mandatory.[223]

The Court further found that the 180-day notice period of commercial marketing required under the BPCIA begins with the approval of the biosimilar.[224] Because Zarxio was approved on March 6, 2015, Sandoz could not begin marketing the drug until September 2, 2015.[225] Faithful to the Court’s directive, Sandoz commercially launched Zarxio, at a 15% discount as compared to the original, on September 3, 2015.[226]

Given the potential impact and fractured nature of the Federal Circuit’s decision–only Judges Lourie and Chen held that disclosure was optional, while only Judges Lourie and Newman held that the 180-day notice was mandatory–it seems to be ripe for Supreme Court review. The Federal Circuit denied a petition for en banc review in October.[227] It remains to be seen, however, whether the Supreme Court will weigh in.

C. Proposed Legislation

In our 2014 Year-End and 2015 Mid-Year updates, we reported that the 114th Congress appears dedicated to improving both clinical trial and drug approval processes to increase access to life-saving drugs. But legislative activity on this front has slowed to a crawl in the second half of 2015. For example, the 21st Century Cures Act, which the House passed with broad bipartisan support (and to much acclaim) days before our 2015 Mid-Year Update, remains stuck in the Senate.[228] Nonetheless, the second half of 2015 saw the enactment of several other notable, health-related legislative proposals.

- Improving Regulatory Transparency for New Medical Therapies Act (H.R. 639): This bill, which we covered in our Mid-Year Update, requires the Drug Enforcement Administration (“DEA”) to schedule new drugs within a specified timeframe and amends other laws to ensure that drug developers do not lose exclusivity time to scheduling delays.[229] President Obama signed the bill into law on November 25, 2015.[230] The law is expected to contribute to the government’s overarching effort to streamline the drug-approval process.

- Ensuring Access to Clinical Trials Act of 2015: Signed into law on October 7, 2015, the Ensuring Access to Clinical Trials Act compensates low-income Americans with rare diseases who participate in clinical trials.[231] The law renews the Improving Access to Clinical Trials Act of 2009, which allows clinical trial participants on Supplemental Security Income and Medicaid to receive compensation, and exempts the first $2,000 earned per year by these participants from counting against other benefits.[232]

- Right to Try Acts: In our 2014 Year-End Update, we briefly covered the Andrea Sloan Compassionate Use Reform and Enhancement Act, H.R. 5805, introduced by the 113th Congress. The bill, like various states’ “Right to Try” acts, seeks to expand access to breakthrough and experimental drugs by terminally ill and other eligible patients.[233] While the 113th Congress never passed the bill, the 114th Congress reintroduced the bill in early 2015.[234] Relatedly, a separate Right to Try Act of 2015 was introduced in the House in July 2015.[235] Unlike the Andrea-Sloan Act, which emulates its state-law counterparts, this new bill would remove a number of federal barriers to state Right to Try Acts by preventing the federal government from restricting access to experimental drugs intended to treat patients diagnosed with a terminal illness.[236]