July 7, 2016

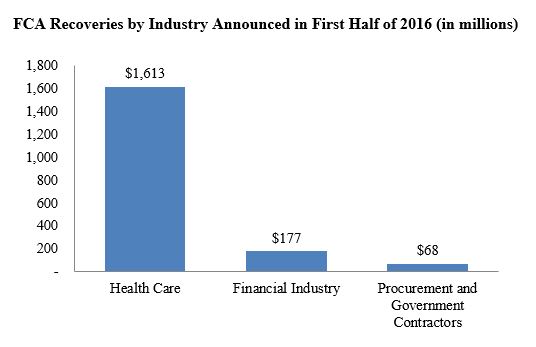

Major changes — that is how we would describe the developments in the first half of 2016 as related to the scope of liability and damages under the federal False Claims Act (FCA). And these changes usher in a new and uncertain era of exposure for companies that do business with the government. As we have reported for years, the FCA routinely results in several billion dollars’ worth of recoveries every year–indeed even this year, federal and state governments have amassed more than $1.86 billion in FCA recoveries so far. Therefore, the effects of the changes in 2016 could be immense.

So what are these major changes? On the liability front, it was the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision on the so-called “implied certification” theory of liability in United States ex rel. Escobar v. Universal Health Services. In June, the Court held that a company’s “implied certification” of compliance with statutory, regulatory, or contractual requirements is a possible basis for liability under the FCA. But the Court also cabined that theory of liability and fortified the FCA’s materiality requirement. With something to like for plaintiffs and defendants alike, the full import of the Court’s decision remains to be seen. But this much is clear: Escobar alters the boundaries for arguments about FCA liability.

On the damages front, federal agencies worked to implement Congress’ mandate for increased FCA penalties. As we expected, Congress’ formula will almost double FCA penalties, effective August 1, 2016. Under the new regime, minimum per-claim penalties will rise to $10,781 (from $5,500) and maximum per-claim penalties will rise to $21,563 (from $11,000). In a world where per-claim penalties already constitute a large percentage of overall FCA recoveries, this upsurge in penalties could portend an explosion of big-dollar FCA settlements and judgments, as well as trigger new challenges to FCA fines as unconstitutionally excessive under the Eighth Amendment and the Due Process Clause.

In the shadow of these major developments, federal and state legislators, lower courts, and regulators also continued to explore the boundaries of FCA liability as it exists today. The result was a bevy of other important developments concerning the FCA. We address these developments in depth below. As in years past, this mid-year alert first discusses legislative activity at the federal and state levels relating to the FCA and analogous state statutes. Next, we discuss important FCA settlements that have been announced during the first half of this year. And finally, we discuss important case law developments that have occurred during the last six months, including the Supreme Court’s recent Escobar decision. Gibson Dunn’s recent publications on the FCA, including more in-depth discussions of the FCA’s framework and operation along with practical guidance to help companies avoid or limit liability under the FCA, may be found on our website.

I. LEGISLATIVE ACTIVITY

Since our last update, there have been several notable legislative and regulatory developments that may affect companies’ liability under various false claims statutes. At the federal level, penalties for FCA violations have nearly doubled–increasing to more than $21,000 per violation. Meanwhile, the Department of Defense imposed cybersecurity compliance and reporting requirements. And Medicare’s “60-Day Rule” for reimbursing overpayments took effect.

At the state level, although slightly less newsworthy, Alabama and Washington lead the headlines. We also await a determination by the Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General (HHS OIG) as to whether several states’ FCA laws comply with the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 (DRA). These and other notable developments are discussed below.

A. Federal Activity

As we reported in our 2015 Year-End Update, Congress passed legislation in October 2015 requiring agencies to increase FCA penalties to account for inflation. Enacted as part of the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015, the Federal Civil Penalties Inflation Adjustment Act Improvements Act of 2015 (the “2015 Adjustment Act”)[1] required the Department of Justice (DOJ) to make a one-time “catch up” adjustment of FCA penalty levels, which were last adjusted in 1999, to account for inflation through October 2015. The Act also mandates annual inflation adjustments thereafter, which will be pegged to the Consumer Price Index.[2]

As a harbinger of future penalty increases, the U.S. Railroad Retirement Board, an otherwise somewhat obscure agency, made headlines by increasing maximum per-violation penalties for false claims under 31 U.S.C. § 3729 to $21,563.[3] Other agencies have imposed similar increases.[4]

And, on June 30, 2016, DOJ released an interim final rule increasing per-claim FCA penalties to a maximum of $21,563.[5] DOJ released this rule even though the 2015 Adjustment Act provided DOJ with discretion to decrease the amount of the “catch up” adjustment under certain circumstances.[6]

As a result of these developments, companies confronting FCA liability will face drastically higher potential per-claim penalties, perhaps even absent commensurate damages to the government. In past updates, we reported on cases in which defendants leveled Eighth Amendment and Due Process challenges at judgments including substantial FCA penalties where the government or relators failed to prove any damage to the government (or the damages were limited). See, e.g., 2014 Year-End Update (discussing United States ex rel. Bunk v. Gosselin World Wide Moving, 741 F.3d 390 (4th Cir. 2013)). Indeed, FCA defendants have regularly raised constitutional challenges to FCA judgments with significant penalty components, but a number of courts have denied those attempts. See, e.g., United States ex rel. Drakeford v. Tuomey, 792 F.3d 364, 387–89 (4th Cir. 2015).

As penalties diverge even more drastically from damages–especially in cases involving thousands of allegedly false claims–defendants are likely to invoke the Eighth Amendment and the Due Process Clause even more frequently (and energetically). The penalty adjustments may provide ammunition for defendants as they seek to show that the ratio of punitive penalties to compensatory damages exceeds the constitutional rule of thumb established by the Supreme Court in a line of punitive damages cases. Cf. id. at 389 (citing State Farm Mut. Auto Ins. Co. v. Campbell, 538 U.S. 408, 425 (2003), and discussing the Supreme Court’s 4:1 guideline for the ratio of punitive to compensatory damages). We will continue to monitor these developments.

Elsewhere on the federal front, in late December 2015, the Department of Defense issued a second interim rule on Network Penetration and Contracting for Cloud Services.[7] Contractors have until December 31, 2017, to update their security systems to comply with National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publication 800-171, which could be an onerous task.[8] Other new requirements took immediate effect. For instance, contractors must report cyber incidents within 72 hours.[9] The new rule did not add any new compliance monitoring mechanisms, but contractors remain subject to liability under the FCA.

On the health care front, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) issued a final rule governing the return of overpayments within 60 days (the “60-Day Rule”) on February 12, 2016.[10] After a delay to address public concerns about its proposed rule, CMS determined that the 60-day clock starts “when the person has, or should have through the exercise of reasonable diligence, determined that the person has received an overpayment and quantified the amount of the overpayment.”[11] According to the final rule, “[a] person should have determined that the person received an overpayment and quantified the amount of the overpayment if the person fails to exercise reasonable diligence and the person in fact received an overpayment.”[12] The final rule discusses a 6-month window as a “benchmark” for what constitutes reasonable diligence[13] and provides that “overpayments must be reported and returned only if a person identifies the overpayment within 6 years of the date the overpayment [is] received.”[14] CMS also admonished providers to “have effective compliance programs as a way to avoid receiving or retaining overpayments.”[15]

In addition, on May 6, 2016, CMS issued a final rule affecting Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP).[16] As our 2015 Year-End False Claims Act Update anticipated, the final rule requires that Medicaid-managed plans be held to at least an 85% medical loss ratio standard, so that at least 85% of the managed care entity’s revenue is directed to patient care rather than to administrative costs or profit.[17] Reporting requirements tied to that recommendation could expose companies to a new FCA risk.

Finally, there has been no further action on the Motor Vehicle Safety Whistleblower Act (S. 304) since we discussed it in our 2015 Mid-Year Update. The Senate approved the bill on April 28, 2015 and the bill moved to the House, where it was referred to the Energy and Commerce Committee’s Subcommittee on Commerce, Manufacturing, and Trade on May 1, 2015.[18]

B. State Activity

State-level legislative false claims act activity was generally quiet in the first half of 2016. Alabama legislators introduced a false claims act in the state’s senate on February 11, 2016.[19] And Washington enacted legislation reauthorizing its Medicaid FCA and requiring qui tam provisions to be revisited or repealed in 2023.[20]

As for several items that we mentioned in previous updates:

- On July 12, 2015, Wisconsin repealed its False Claims for Medical Assistance Act.[21] Enacted in 2007, the False Claims for Medical Assistance Act was the state’s version of the federal FCA.[22] Wisconsin’s unusual action is especially notable during a time when most states have been active in expanding or creating state versions of the federal FCA.

- On May 18, 2015, the Governor of Vermont signed into law the Vermont False Claims Act, a state false claims act that is very similar to the federal FCA. On August 5, 2015, HHS OIG determined that the Vermont False Claims Act complies with the DRA.[23] On March 15, 2016, Vermont’s FCA took effect; notably, the law purports to retroactively encompass all conduct within the state’s applicable statute of limitations.[24]

- The New Jersey general assembly, the lower house of the state’s legislature, passed a bill on May 14, 2015, that allows for the retroactive application of New Jersey’s false claims act. The bill was introduced in the state’s senate and referred to its Senate Judiciary Committee on January 12, 2016, but there has been no further action.[25]

- In South Carolina, there remains no further action since January 2015 on a bill to enact the “South Carolina False Claims Act” (S.B. 223) that was referred to the Committee on Judiciary in January 2015.[26]

- New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman announced in February 2015 that he would propose a bill to protect and reward employees who provide information about fraudulent or illegal activity in the banking, insurance, and financial services industries.[27] Assembly Member Annette Robinson introduced the proposed bill on May 4, 2015, on behalf of the Department of Law.[28] The bill was referred to the Assembly Banks Committee for a second time on January 6, 2016, but there has been no further action.[29]

- Wyoming continues to await word from HHS OIG regarding whether Wyoming’s False Claims Act, which the state enacted in 2013, complies with the DRA’s requirements.[30] In March 2016, HHS OIG released an audit of Wyoming’s Medicaid claims,[31] but HHS OIG has not completed its review of Wyoming’s False Claims Act.[32]

- HHS OIG also has yet to announce whether Maryland’s expanded False Claims Act, which took effect on June 1, 2015, complies with DRA requirements.[33]

II. NOTEWORTHY SETTLEMENTS AND JUDGMENTS DURING THE FIRST HALF OF 2016

Federal and state governments have amassed more than $1.86 billion in false claims act recoveries so far this year, nearly matching last year’s accumulation by the mid-year mark. Unsurprisingly, the bulk of the recoveries have been from the health care sector, where the dollar volume of recoveries outpaced the first six months of 2015 by nearly one billion dollars. Somewhat surprisingly, recoveries from the financial industry and government contractors have dwindled significantly. Whether the volume of recoveries against these industries will remain relatively low compared to years past remains to be seen.

Two settlements drove the dramatic increase in health care sector recoveries–one involving a pharmaceutical company and a second with a medical equipment manufacturer. Those two companies collectively agreed to pay nearly $1.1 billion to resolve qui tam actions. We discuss these and other notable settlements from the past six months below.

A. Federal Settlements

1. Health Care

Health care industry companies, as in years past, continued to be targets of investigations and resolutions in the first half of 2016.

- On January 5, 2016, a Nashville-based pharmacy and its majority owner agreed to pay up to $7.8 million to resolve allegations that the pharmacy automatically refilled medications without a physician order, improperly waived co-payments without assessing whether the patient could pay, used manufacturer’s co-payment cards to pay for certain patients’ co-payments, and billed Medicare for medications dispensed after certain patients’ deaths or without a valid prescription. The $7.8 million consists of an initial payment of $500,000 and contingency payments over the next five years. The whistleblower, a former order entry technician for the pharmacy, will receive up to $1.4 million.[34]

- On January 8, 2016, the former owner of a Virginia-based pathology laboratory agreed to pay up to $3.75 million for reimbursements for cancer detection tests that allegedly were not medically necessary or performed without a treating physicians’ consent or order. In addition, the government asserted that the laboratory offered various discounts and billing arrangements to induce physicians to conduct business with the laboratory. The settlement provides for a guaranteed $2.6 million payment, with up to an additional $1.125 million to be paid within the next five years for certain financial contingencies. The laboratory separately settled in 2014 for $6.5 million. For his role in the two settlements, a whistleblower will receive more than $2.5 million.[35]

- On January 12, 2016, the nation’s largest nursing home therapy provider and its rehabilitation therapy division agreed to pay $125 million to resolve allegations that they caused skilled nursing facility customers to submit claims for services that were not medically necessary or reasonable, or that were never provided. Settlements with four skilled nursing facilities, totaling more than $8.2 million, were simultaneously announced. These settlements are the latest in nine total resolutions dating back to 2014 for similar conduct. Two whistleblowers will share in $24 million of the recovery.[36]

- On January 15, 2016, a California hospital agreed to pay more than $3.2 million to resolve allegations that it violated the Stark Law and the FCA. The government alleged that the hospital entered into financial agreements with physicians that were not commercially reasonable or for fair market value (or that did not satisfy an exception to the Stark Law because, among other issues, the agreements were expired, missing signatures, or could not be located).[37]

- On January 21, 2016, a New York-based managed care company agreed to pay $46.7 million to settle civil claims that it billed Medicaid for services to individuals who attended or were referred by social adult day care centers and who were medically ineligible to participate in its managed long-term care plan. By way of background, the New York State Department of Health published guidance in 2013 that attendance at social adult day care centers did not satisfy relevant eligibility standards.[38]

- On February 1, 2016, a federal district court judge approved a settlement between a medical waste disposal company and 14 states and the District of Columbia to resolve allegations that the company instituted yearly 18% price increases for its products despite contractual terms specifying long-term fixed-price contracts. The company agreed to pay $28.5 million. The whistleblower, a former customer relations specialist for the company, will receive $5.7 million.[39]

- On February 8, 2016, a federal district court judge approved a settlement requiring a Georgia-based hospital to pay $9.9 million to resolve allegations that it paid physicians above-market rates in exchange for referrals for its services. The company also entered into a corporate integrity agreement with HHS OIG as part of the court-approved settlement agreement. The whistleblower was the hospital’s former CEO; the amount he will receive from the settlement has yet to be announced.[40]

- On February 11, 2016, two compounding pharmacies and four physicians, all in Florida, agreed to pay $10 million to settle allegations that the physicians prescribed pain and scar creams that often were not used by patients, and that the profits from federal reimbursement for the creams were shared in part with the physicians. Notably, since March 2015, the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Middle District of Florida has recovered more than $50 million in false claims from compounding pharmacies.[41]

- On February 12, 2016, a New Jersey physician and his two companies agreed to pay $5.25 million to conclude an investigation into the companies’ billing practices. The government alleged that it reimbursed for tests that were never performed and for physical therapy services that were not performed by a qualified therapist.[42]

- On February 17, 2016, 51 hospitals in 15 states agreed to pay $23.75 million to conclude a nationwide investigation into the implantation of cardiac devices in Medicare patients in violation of coverage requirements. The conduct is alleged to have occurred between 2003 and 2010. The government has previously reached agreements with 457 hospitals for more than $250 million regarding the same conduct.[43]

- On March 1, 2016, the U.S. unit of a global medical equipment company resolved allegations that it paid kickbacks to physicians and hospitals to win new business and reward sales of its endoscopes and other surgical equipment. The company agreed to pay $646 million, consisting of $310.8 million to resolve civil claims and $312.4 million in criminal penalties. Of the civil settlement sum, approximately $267.3 million will be remitted to the federal government and approximately $43.5 million will be allocated to the participating states. Additionally, the company will pay a $22.8 million federal criminal penalty to resolve charges under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. This settlement is the largest that a medical device company has paid for violations of the federal Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS). The case originated with a lawsuit by the former chief compliance officer of the company, who will receive more than $51.1 million as his relator’s share.[44]

- On March 8, 2016, a Florida-based physician-led integrated cancer care provider, the largest in the nation, agreed to settle allegations that it improperly billed federal health care programs for performing a certain procedure without a reasonable and necessary medical purpose. The company agreed to pay $34.7 million; the whistleblower, a former physicist at one of the company’s centers, will receive more than $7 million.[45]

- On March 23, 2016, a Pennsylvania-based medical equipment manufacturer agreed to pay $34.8 million to resolve allegations that it provided free call center services to durable medical equipment suppliers to induce the suppliers to purchase the company’s sleep apnea masks. The company allegedly provided the call center services at no cost as long as its masks were being used, but charged a monthly fee for call center services provided to users of competitors’ masks. The whistleblower, a physician who worked for various durable medical equipment companies, will receive $5.38 million as the relator in this case.[46]

- On April 27, 2016, the world’s second-largest pharmaceutical company, headquartered in New York, agreed to pay $784.6 million and admitted that it failed to report, and offer to Medicaid, deep discounts on two of its drugs that it offered to hospitals throughout the United States through bundled sales arrangements. The settlement brings to a close two whistleblower lawsuits which were initiated more than a decade ago. Federal and state governments will pay a combined relator share of around $98 million in this case.[47]

- On April 29, 2016, an Illinois-based health care product manufacturer and a New York-based medical product supplier agreed to collectively pay $20.9 million to resolve kickback allegations. The government alleged that, from 2007 to 2014, the manufacturer paid the supplier to conduct marketing promotions, conversion campaigns and otherwise refer patients to the manufacturer’s products. The manufacturer also allegedly agreed to pay the bonus commissions of the supplier’s salesforce for sales of its products to new patients. Three whistleblowers initially raised these allegations; their share of the settlement has not yet been determined.[48]

- On May 5, 2016, the City of New York agreed to pay $4.3 million to resolve claims that between 2008 and 2012, the New York City Fire Department received reimbursement for emergency ambulance transport for Medicare patients that was not medically necessary. Notably, the City had self-disclosed this matter to the government.[49]

- On June 1, 2016, the former owner of a Nashville-based drug testing laboratory and the laboratory agreed to pay $9.35 million to resolve allegations that the company paid kickbacks to physicians in the form of contributions to electronic health records systems purchased by client physician practices. Although contributions to electronic health records systems were permissible at the time in certain instances, the government alleged that the payments fell outside of statutory safe harbor provisions. The owner also agreed to a five-year exclusion from participation in all federal health care programs. The relator, a former employee of the laboratory, will receive $1.68 million.[50]

- On June 6, 2016, pharmaceutical companies based in San Francisco, California and Farmingdale, New York, agreed to pay $67 million to resolve allegations that the companies misled providers about the effectiveness of a certain drug to treat non-small cell lung cancer. The whistleblower in the lawsuit will receive approximately $10 million.[51]

- On June 8, 2016, a North Carolina-based pharmaceutical company agreed to pay $54 million to resolve claims related to its speakers program, which held more than 10,000 sessions between 2009 and 2013. As part of the program, the company provided more than 500 physicians with honoraria to speak, either in-person or via a recording, about the company’s products. The company admitted that, during some of the programs, the pre-recorded presentation was not played or the designated speaker was not called following the presentation to answer questions, but was nevertheless paid the honorarium. Further, some of the sessions consisted primarily of expensive meals and entertainment.[52]

As for notable judgments, on March 31, 2016, a federal judge in the Northern District of Alabama granted summary judgment for a hospice provider that, according to DOJ, billed Medicare for unnecessary hospice care. Notably, DOJ had sought more than $200 million in fines and penalties under the FCA on the theory that the provider knowingly admitted unqualified patients for hospice care. In October 2015, a jury issued a verdict against the provider, which the judge promptly vacated. In granting summary judgment to the provider, the judge determined that disagreement on hospice eligibility between medical experts is not sufficient to prove falsity absent some objective falsehood.[53] DOJ has appealed the decision to the Eleventh Circuit.

On April 7, 2016, a federal jury in Texas ruled for a medical device maker in a $219 million FCA case in which the government declined to intervene. The jury found that the company had not violated the FCA by allegedly filing claims for Medicare and Medicaid payments that were based on unapproved uses for its medical devices.[54]

2. Financial Industry

The flow of alleged housing finance FCA violations stemming from the financial crisis has slowed to a trickle in recent months, but the first half of the year produced a few mortgage-related settlements that are fairly substantial in their own right. Recent notable settlements include:

- On April 15, 2016, a mortgage originator and underwriter based in New Jersey settled alleged FCA violations with the Department of Justice for $113 million. The originator and underwriter allegedly ignored Federal Housing Administration (FHA) guidelines for FHA-insured mortgages between 2006 and the end of 2011¾well after the financial crisis. In addition to generating mortgages that did not meet requirements to be FHA-insured, the originator and underwriter allegedly failed to report defaults to the federal government.[55]

- On May 13, 2016, an upstate New York bank settled with DOJ for $64 million after the government alleged that the bank originated and underwrote FHA-insured mortgage loans that it knew did not meet federal requirements. The bank allegedly originated and underwrote those mortgage loans between 2006 and 2011, during which time it allegedly identified problematic loans but self-reported only seven.[56]

3. Procurement and Government Contractors

Resolutions with government contractors thus far this year have reflected the broad array of alleged misconduct that may lead to FCA liability: misrepresenting a contractor’s qualification or status, inflating costs, evading customs duties, providing false certifications of compliance, and producing defective products.

- On January 6, 2016, DOJ announced a $9 million settlement stemming from alleged FCA violations connected to United States Agency for International Development (USAID) contracts. According to the government, a design and construction firm misrepresented its eligibility and qualifications for infrastructure projects in Egypt in the 1990s by concealing from the government that it had already engaged joint-venture partners for the project.[57]

- On February 1, 2016, a Florida security and fire-protection services company settled FCA allegations for $7.4 million. The company, which subcontracted with a larger government contractor to provide fire-fighting services to U.S. military bases in Iraq, allegedly inflated labor costs by double-billing certain salaries as both direct and indirect costs. More than $1.3 million of the settlement funds will be awarded to the whistleblower who initially brought the FCA lawsuit.[58]

- On February 22, 2016, DOJ announced the first of two FCA settlements related to alleged evasion of customs duties on goods imported from China, as a series of related companies agreed to pay $3 million to resolve the allegations against them. Although the purported perpetrators did not make false claims for federal funds, they made allegedly false statements in avoidance of paying funds to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s Customs and Border Protection. Between 2009 and 2012, the companies allegedly misrepresented the nature of the products they were importing in order to evade duties that would have been imposed under the antidumping laws. The goods in question were graphite electrodes used to heat furnaces for steel manufacturing.[59]

- On February 29, 2016, DOJ agreed to dismiss its long-standing claims against a large government contractor and two of its subsidiaries in exchange for a payment of $5 million–$4 million of which accounted for alleged FCA violations–for allegedly violating environmental laws and then making false claims for Department of Energy funds that indicated compliance with those environmental laws. The contractor and its subsidiaries managed the uranium enrichment process and environmental services at Paducah Gaseous Diffusion Plant in Kentucky for the Department of Energy from 1984 to 1999. Whistleblowers filed their complaint in 1999, and the Government’s 2003 complaint alleged that the contractor failed to identify, report, handle, and dispose hazardous waste properly, and then filed claims for payment that misrepresented compliance with those requirements. Various whistleblowers, including a major environmental law organization, will share $920,000 due to their filing of the qui tam action. The contractor admitted no liability in the settlement agreement, and the case was disposed of without a consent decree or any injunctive relief.[60]

- On March 7, 2016, a defense contractor that provides helmets to the Army resolved FCA claims against it by paying $3 million. The government alleged that the contractor provided defective helmets from 2006 to 2009 and that the helmets were not manufactured and tested properly. The lawsuit originated as a qui tam action filed by employees of a subcontractor. The two whistleblowers will split $450,000.[61]

- On March 14, 2016, DOJ announced a $5 million settlement with a government contractor that allegedly misrepresented its status as a small business owned by military veterans who were disabled as a result of their military service. According to the government, the disabled veteran who purportedly managed the company had no managerial or business authority and, rather, performed mostly administrative and custodial tasks. The contractor allegedly went so far as to create a fake email account in the name of the disabled veteran. A qui tam relator will receive $875,000 of the settlement.[62]

- On March 28, 2016, a maker of infrared countermeasure flares, which are used to protect military planes from heat-seeking missiles, agreed to pay $8 million after DOJ alleged that the company misrepresented the source of its raw materials in violation of a U.S. Army contract. Infrared countermeasure flares use magnesium powder and other materials to create heat to draw missiles away from airplanes. The relevant contract mandated that the magnesium powder be procured from either an American or Canadian producer, but the contractor allegedly procured the powder from a Chinese manufacturer instead.[63]

- The second FCA settlement related to alleged evasions of customs duties was announced on April 27, 2016. A Los Angeles-based furniture store that procures furniture from China allegedly evaded customs duties between 2007 and 2014 when it misclassified imported wooden bedroom furniture that otherwise would have been subject to antidumping duties. The furniture store paid $15 million to settle the allegations, which initially arose from a qui tam lawsuit, for which the relator will receive $2.4 million.[64]

- On May 16, 2016, a Tennessee-based construction company settled with DOJ for more than $2.25 million to resolve FCA allegations based upon alleged subversions of laws meant to encourage participation of minority-owned businesses in federal contracting. For work on a Department of Transportation contract, the construction firm engaged a subcontractor that was certified as a “Disadvantaged Business Enterprise” (DBE). However, the construction firm allegedly placed its own employees on a temporary basis with the subcontractor to perform the contract work instead of the subcontractor’s own employees. This originated as a qui tam whistleblower case, and the relator will receive $500,000.[65]

B. State Settlements

State settlements to date in 2016 have predominantly involved participants in the health care industry. In addition to the resolutions summarized below, five states and the District of Columbia secured $43.5 million as part of the $646 million federal judgment (discussed above) against the U.S. operating unit of a global medical equipment company for alleged violations of the AKS.

- On March 7, 2016, Massachusetts announced a settlement worth more than $8 million with a large telecommunications contractor, $2.7 million of which stems from alleged violations of the Massachusetts FCA. The contractor allegedly breached its contract with the Massachusetts Department of Transportation and violated the Massachusetts FCA by failing to provide required cable certifications and refusing to pay rent for its right to run cables along highways.[66]

- On March 8 and May 25, 2016, the State of Connecticut announced two separate settlements for slightly more than $400,000 apiece with two psychiatrists who allegedly knowingly submitted claims for inflated reimbursements. Both psychiatrists allegedly coded brief and simple meetings with Medicaid patients as longer and more intensive than they actually were, driving up reimbursement rates. [67]

- On April 12, 2016, the State of Arkansas announced its first FCA settlement in 15 years when it obtained a $719,000 payment from a home health care company. After the company was audited in June 2014, the Arkansas Office of Medicaid Inspector General determined that the company fraudulently billed the state for Medicaid funds in violation of the Arkansas FCA.[68]

III. CASE LAW

A. The Supreme Court Issues Its Long-Awaited Opinion on the Implied Certification Theory of Liability

In mid-June, the U.S. Supreme Court issued its long-awaited decision in United States ex rel. Escobar v. Universal Health Services,[69] a case that presented two issues: (1) whether a defendant’s “implied false certification” of compliance with statutory, regulatory, or contractual requirements is a proper basis for liability under the False Claims Act, and (2) whether that liability must be premised on express “conditions of payment.” No. 15-7, 1 (2016).

Entering the fray after years of fractured lower-court jurisprudence, the Supreme Court held that, “at least in certain circumstances, the implied false certification theory can be a basis for liability.” Id. But the Court also meaningfully stiffened the statute’s materiality requirement, describing it as “rigorous” and “demanding.” Id. at 14, 15.

The Escobar case involved allegations that a mental health hospital provided inadequate care to a teenage patient by using under qualified personnel to deliver counseling services. Id. at 4–5. The patient’s parents filed suit under the FCA alleging that the hospital submitted false claims to Medicaid by “impliedly certifying” that medical services were provided by specific types of professionals (in accordance with state Medicaid requirements), when in fact, they were not. Id. at 5–6. Because the hospital’s claims for payment never expressly stated anything about the medical professionals, the parents could not argue that the claims were expressly false, and therefore the case hinged on the viability of an “implied false certification” theory of liability. This issue had divided the lower courts.[70]

The “implied certification” theory had been used by some lower courts to hold that claims for payment could be false or misleading even if they said nothing about a defendant’s compliance with underlying laws, rules, or regulations. The Supreme Court did not go that far. Rather, the Court held that the implied false certification theory can provide a basis for liability under the FCA where (1) “the claim does not merely request payment, but also makes specific representations about the goods or services provided,” and (2) “the defendant’s failure to disclose noncompliance with material statutory, regulatory, or contractual requirements makes those representations misleading half-truths.” Id. at 11 (emphasis added). In so holding, the Court re-focused the analysis of “implied” certifications on common-law principles: failing to disclose a legal violation while submitting a claim may be actionable because it may amount to a “half-truth.” Id. at 9. The Court left for another day the question of “whether all claims for payment implicitly represent that the billing party is legally entitled to payment.” Id. at 9–10 (emphasis added). But there is a strong argument that Escobar limited the “implied certification” theory to situations where there have been “specific representations” in claims for payment that amounted to “half-truths.”

The Court did not stop with its implied certification analysis. Rather, the Court also concluded that “[a] misrepresentation about compliance with a statutory, regulatory, or contractual requirement must be material to the Government’s payment decision,” and emphasized that the FCA has a “rigorous materiality requirement.” Id. at 14, 2. The Court rejected the notion that the critical question was whether a statutory, regulatory, or contractual requirement was expressly a “condition of payment” or instead a “condition of participation,” a distinction some lower courts had used to narrow the scope of implied certification cases. Instead, the Court explained that whether an obligation was a condition of payment is relevant to, but not dispositive of, the issue of materiality.

The Court then delved into this requirement and clarified “how [it] should be enforced.” Id. at 14. The materiality standard, the Court explained, is “demanding,” id.at 15, and the relevant question is not whether the alleged underlying legal violation was “capable” of affecting payment, but whether the government actually “would not have reimbursed the claims had it known that it was billed for . . . services that were performed [in violation of the statute or regulation at issue].” Id. at 6. Thus, a requirement is not material merely because the government calls it a “condition of payment,” id. at 15–16 (which is what some lower courts had held), or because the government would “have the option” to decline to pay if it knew of defendant’s noncompliance, id. at 16 (which other courts had held). Instead, the touchstone is whether noncompliance with the requirement, if disclosed, would have affected either a reasonable person’s decision or the actual, subjective decision of the government agent. Id. at 14–15. As such, “if the Government pays a particular claim in full despite its actual knowledge that certain requirements were violated, that is very strong evidence that those requirements are not material.” Id. at 16 (emphasis added). And materiality “cannot be found where noncompliance is minor or insubstantial.” Id.

Finally, the Court noted that in addition to establishing materiality, an FCA plaintiff must also establish that the defendant knew the requirement at issue was material. “What matters is . . . whether the defendant knowingly violated a requirement that the defendant knows is material to the Government’s payment decision.” Id. at 2 (emphasis added). This arguably imposes a “second level” of the scienter requirement in FCA cases–a plaintiff must now prove not only that the defendant knowingly submitted false claims, but also knew an alleged violation of underlying legal requirements was material to the government.

Escobar represents the eighth time in the last ten years that the Supreme Court has considered issues under the FCA. As the lower courts sort through the wide-ranging implications of Escobar, the contours of FCA liability will surely continue to change. We will continue to monitor these developments.

B. Supreme Court Grants Certiorari in Another FCA Case

While the Escobar opinion attracted the most attention during the first half of 2016, another issue before the Supreme Court is worth keeping an eye on in the year to come.

In June, the Supreme Court granted certiorari in State Farm Fire & Casualty Co. v. United States ex rel. Rigsby, a case that will resolve a circuit split about whether a FCA complaint should be dismissed when it is publicly disclosed during the mandatory “seal” period while the government investigates. See No. 15-513, 84 U.S.L.W. 3239, 2016 WL 3041061, at *1 (U.S. May 31, 2016). Under the FCA’s qui tam provisions, purported whistleblowers must file their complaint under seal, giving the government time to investigate the allegations and decide whether or not to intervene in the case. 31 U.S.C. § 3730(b)(2). The initial seal period is 60 days, id., but in practice the government often obtains multiple extensions, sometimes for many years.

In Rigsby, State Farm faced allegations that it violated the FCA by shifting responsibility for Hurricane Katrina damage to the federal government by asserting that damage was caused by flooding (which the federal government pays for) instead of by wind (which private insurers pay for). See United States ex rel., Rigsby v. State Farm Fire & Cas. Co., 794 F.3d 457, 464 (5th Cir. 2015). The plaintiffs in Rigsby went to the media with their allegations long before the seal period expired, and State Farm argued that this violation of the seal provision required dismissal. Id. at 470. But the Fifth Circuit disagreed, thereby deepening a circuit split over whether, and when, violation of the seal requirement is a valid basis for dismissal. Id. at 471–72. Unlike the Fifth Circuit, some circuits have held that a violation of the seal requirement mandates dismissal, or at least that courts should dismiss a case if a seal violation implicates the congressional goals of the requirement, which are to avoid prejudice to the defendant’s reputation and the government’s investigation. See, e.g., United States ex rel. Summers v. LHC Grp. Inc., 623 F.3d 287, 291 (6th Cir.2010); United States ex rel. Pilon v. Martin Marietta Corp., 60 F.3d 995, 999–1000 (2d Cir. 1995); Smith v. Clark/Smoot/Russell, 796 F.3d 424, 430 (4th Cir. 2015). The Supreme Court will now resolve that question. Depending on how the Court rules, this case could offer defendants a new avenue of attack in FCA cases where the plaintiffs break the seal requirement.[71] Notably, the Supreme Court opted not to grant certiorari on other issues raised by State Farm, including a question as to the collective knowledge doctrine.

C. Developments in FCA Pleading Requirements

Critiquing a relator’s failure to plead fraud with particularity can be an effective weapon in a company’s cache of potential defenses against FCA suits. In two recent decisions, the Second and Sixth Circuits explored the bounds of Rule 9(b) particularity requirements.

The Second Circuit recently demonstrated its willingness to parse specific contractual provisions when comparing alleged deficiencies against applicable requirements at issue in a case. See United States ex rel. Ladas v. Exelis, Inc., No. 14-4155, 2016 WL 3003674 (2d Cir. May 25, 2016). The relator in Ladas brought FCA claims based on the defendant’s allegedly fraudulent certifications that equipment supplied to the government under its procurement contract conformed with applicable contractual requirements. Id. at *8. In affirming the district court’s dismissal for failure to plead fraud with particularity, the Second Circuit reiterated that the complaint must demonstrate how the alleged contractual violations specifically connect to particular false statements that were material to the alleged false claims for payment. Id. at *9.

In particular, the Second Circuit criticized the specificity and relevance of the relator’s allegations where the complaint cited only to violations of internal company specification requirements outside of the contract and offered “hypotheses” as to how alleged problems could affect ordered products without providing factual allegations “concerning the actual condition of the equipment.” Id. at *8. While fact-specific, the level of scrutiny applied by the Second Circuit in Ladas is encouraging to the extent it demonstrates a demand for something more concrete than allegations built on presumed, or even hypothetical, contractual deficiencies.

The analysis in a recent Sixth Circuit decision (United States ex rel. Eberhard v. Physicians Choice Laboratory Servs., LLC, No. 15-5691, 2016 WL 731843 (6th Cir. Feb. 23, 2016)) continues to solidify guidance as to when a plaintiff may benefit from relaxed Rule 9(b) particularity requirements. In Eberhard, the relator asserted that claims for payment submitted by a medical testing service were false because of purported AKS violations. The company allegedly used commission-based compensation arrangements with independent contractor sales representatives to induce referrals of samples that the defendant would then test (and subsequently seek federal reimbursement for the testing). Id. at *2. The Sixth Circuit first examined whether the allegations met the Sixth Circuit’s heightened pleading requirements under Rule 9(b)–that is, allegations detailing “representative samples of the alleged fraudulent scheme” in addition to particular details of the scheme itself. Id. at *4. The court concluded that alleging the total number of samples referred from 1099 sales representatives to the defendant in addition to the estimated proportion of those samples eventually submitted by the defendant for reimbursement was not sufficient, as the relator failed to allege “which specific false claims constitute[d] a violation of the FCA.” Id. at *4 (quoting United States ex rel. Bledsoe v. Cmty. Health Sys., Inc., 501 F.3d 493, 505 (6th Cir. 2007)) (internal quotation marks omitted).

The court then analyzed the circumstances under which the relator may be subject to a relaxed Rule 9(b) pleading standard (e.g., where a relator pleads “facts which support a strong inference that a claim was submitted”–such as where the relator has personal knowledge that the claims were submitted for payment–and where the failure to allege specific false claims is not due to any conduct of the relator). Id. (quoting Chesbrough v. VPA, P.C., 655 F.3d 461, 471(6th Cir. 2011)) (internal quotation marks omitted). In contrast with cases in which individuals had personal knowledge of the defendants’ coding and billing practices, the relator’s personal knowledge in Eberhard related only to the alleged “fraudulent scheme”; the relator did not allege any specifics related to the defendant’s actual submission of claims to the government, and thus “fail[ed] to bridge the gap between the alleged false scheme and the submission of false claims for payment.” Id. at *5–6. Of note, the Sixth Circuit clarified that “personal knowledge is only one way in which a plaintiff may establish a ‘strong inference’ that false claims were submitted.” Id. at *6 (internal citation and quotation marks omitted). Eberhard signals that the relaxed Rule 9(b) pleading standard will not be easy for plaintiffs to meet, but the decision also–in the court’s own words–“leave[s] open” the possibility of more lenient pleading requirements in certain cases. Id. (internal citation and quotation marks omitted).

D. Developments in the Public Disclosure Bar

In the first six months of 2016, there have been six different Court of Appeals decisions addressing the FCA’s public disclosure bar, which requires courts to dismiss FCA claims that are substantially similar to information previously disclosed in several enumerated public sources, unless the relator qualifies as an “original source” of the information. 31 U.S.C. § 3730(e)(4).

1. The Third and Seventh Circuits Interpret the “Original Source” Exception

In 2010, Congress revised the “original source” provision; it now encompasses individuals “who ha[ve] knowledge that is independent of and materially adds to the publicly disclosed allegations or transactions.” 31 U.S.C. § 3730(e)(4)(B). Two recent federal appellate decisions focus on this language, with somewhat divergent outcomes.

In United States ex rel. Moore & Co., P.A. v. Majestic Blue Fisheries, LLC, 812 F.3d 294, 304 (3rd Cir. 2016), the Third Circuit considered whether the relator was an original source (after determining that the allegations of fraud had been publicly disclosed). The court held that, under the current “original source” definition, “a relator’s knowledge must be independent of, and materially add to, not all information readily available in the public domain, but rather, only information revealed through a public disclosure source in § 3730(e)(4)(A).” Id. at 305. Thus, the fact that the relator obtained its information through discovery in a separate wrongful death action constituted “independent” knowledge. The court also concluded that because the relator “discovered information such as what specific individuals were involved in the alleged fraud and how they initiated and perpetrated the alleged transgression,” relator “added to the publicly disclosed information in a material way.” Id. at 307, 308. The relator therefore qualified as an original source, and the Third Circuit did not apply the public disclosure bar.

In United States ex rel. Bogina v. Medline Industries, Inc., 809 F.3d 365, 368 (7th Cir. 2016) (Posner, J.), the Seventh Circuit applied the new definition of “original source” to a pre-2010 case, holding “that because the earlier definition is inscrutable as well as skimpier than the current one, the current one should be deemed authoritative regardless of when a person claiming to be an original source acquired his knowledge.” Applying the new definition, the court determined that relator was not an original source because “he merely ‘add[ed] details’ to what [was] already known in outline” as a result of a previous lawsuit. Id. at 370. As such, the fact that the relator focused on different customers, pertained to different government health care programs, and addressed different time periods did not “materially add[]” to what had been disclosed in the previous lawsuit. Id. at 369–70.

2. Recent Decisions Addressing What Is Required to Trigger the Bar Indicate a Merger of the Public Disclosure and Original Source Analyses

The public disclosure provision may bar a suit “if substantially the same allegations or transactions as alleged in the action or claim were publicly disclosed.” 31 U.S.C. § 3730(e)(4)(A). In the last six months, the Sixth, Seventh, and Ninth Circuits have addressed the level of specificity required for a public disclosure to trigger the bar. Although each of these decisions pertained to claims subject to the pre-2010 public disclosure bar, each court indicated that its reasoning would apply equally to the current provision. See Advocates for Basic Legal Equality, 816 F.3d 428, 430 (6th Cir. 2016); Cause of Action v. Chicago Transit Authority, 815 F.3d 267, 281 n.20 (7th Cir. 2016); United States ex rel. Mateski v. Raytheon Co., 816 F.3d 565, 569 n.7 (9th Cir. 2016).

These decisions establish that the substantial similarity analysis overlaps considerably, if not entirely, with the analysis of whether the relator materially adds to the public knowledge under the original source exception. In Advocates for Basic Legal Equality, the Sixth Circuit considered whether public disclosures that a bank failed to take required loss mitigation measures before initiating the foreclosure process (but did not disclose that the activity was fraudulent), would bar FCA claims premised on the same actions with regard to a specific subset of loans. After underscoring the public disclosure bar’s broad coverage, the court held that a generalized disclosure of information from which the government would be alerted to the possibility of fraud is enough to trigger the bar. Id. at 430–31.

Then, in a nearly identical analysis, the Sixth Circuit rejected relator’s assertions that it qualified as an original source because it provided more specific details regarding the fraud. The court indicated that “[u]nder the ‘wide-reaching public disclosure bar,'[] we have no problem finding that the broader, publicly disclosed category (a variety of mortgages) encompasses [relator’s] narrower category (federally insured mortgages).” Id. at 432 (quoting Schindler Elevator Corp. v. United States ex rel. Kirk, 563 U.S. 401, 408 (2011)). Merely adding details as to how the alleged fraud took place was inadequate to establish a relator as an original source. Id. Nor did characterizing the transactions at issue as fraudulent qualify relator as an original source, even if the public disclosures did not explicitly reference fraud. Id.

By contrast, in Mateski, the Ninth Circuit held that “[a]llowing a public document describing ‘problems’–or even some generalized fraud in a massive project across a swath of an industry–to bar all FCA suits identifying specific instances of fraud in that project or industry would deprive the Government of information that could lead to the recovery of misspent Government funds and prevention of further fraud.” 816 F.3d at 577. The court observed that, although “at a high level of generality, [relator’s] Complaint and the public reports” discussed similar issues, “at a more granular level, the allegations in [relator’s] Complaint discuss specific issues found nowhere in the publicly disclosed information.” Id. at 574. Because relator’s allegations were “different in kind and in degree” to the publicly disclosed information, the Ninth Circuit determined that he had provided “genuinely new and material information of fraud.” Id. at 578–79. In short, the relator was an original source, having “materially add[ed] to the publicly disclosed allegations or transactions.” See 31 U.S.C. § 3730(e)(4)(B).

In Cause of Action, the Seventh Circuit evaluated whether a publicly disclosed letter and audit report indicating that a transit operator had misreported transit data to the Federal Transit Administration triggered the public disclosure bar in a suit asserting that the operator fraudulently misreported that data. To avoid the public disclosure bar, the court explained, a relator must provide additional material information “beyond what has been publicly disclosed.” 815 F.3d at 281. The court concluded that alleging scienter was inadequate to avoid the bar. Id. at 281. Likewise, the bar applies even if the relator’s allegations “span[] a broader timeframe.” Id. at 281–82. The court further noted that because relator “ha[d] not conducted any independent investigation or analysis to reveal the fraud it allege[d],” the statutory bar was warranted. Id. at 282. Because the allegations were “substantially similar to those contained” in the public materials, the court held that the relator was not an original source. Id. at 283.

3. The Fourth Circuit Bars a Pre-2010 Action Where Relators’ Only Knowledge Came from Attorneys

Applying the pre-2010 public disclosure bar, the Fourth Circuit held that relators could not proceed with a case based on information obtained by their attorney in a separate litigation. United States ex rel. May v. Purdue Pharma L.P., 811 F.3d 636, 640 (4th Cir. 2016). Under Fourth Circuit precedent, the pre-2010 version of the public disclosure bar applied only where allegations were derived from publicly disclosed materials. Id. The court found that “it is clear that the Relators did not independently discover the facts underpinning their allegations,” but instead obtained their knowledge “from their attorney’s involvement” in earlier litigation. Id. at 641. The court observed that the FCA “is not designed to encourage lawsuits by individuals like the Relators who (1) know of no useful new information about the scheme they allege, and (2) learned of the relevant facts through knowledge their attorney acquired when previously litigating the same fraud claim.” Id. at 643. Accordingly, the court held that the claims were precluded by the public disclosure bar. Id.

4. Two Additional Circuits Hold That the Post-2010 Bar Is Not Jurisdictional

Before the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) amendments, the public disclosure bar imposed an express jurisdictional restriction on a court’s authority to hear a case brought pursuant to the FCA. In 2010, however, Congress removed any reference to “jurisdiction” from the public disclosure bar provision. To date, each circuit court that has specifically addressed the issue has held that the public disclosure bar is no longer jurisdictional. Most recently, the Third and Sixth Circuits–following earlier decisions by the Fourth and Eleventh Circuits–held that, as a result of Congress’ removal of any reference to “jurisdiction,” the amended public disclosure bar is not jurisdictional. United States ex rel. Moore & Co., P.A. v. Majestic Blue Fisheries, LLC, 812 F.3d 294, 299–300 (3d Cir. 2016); United States ex rel. Advocates for Basic Legal Equality, Inc. v. U.S. Bank, N.A., 816 F.3d 428, 433 (6th Cir. 2016).

5. The Fourth Circuit Evaluates the Impact of Amended Pleadings on the Applicability of the Public Disclosure Bar

In United States ex rel. Beauchamp v. Academi Training Center, 816 F.3d 37 (4th Cir. 2016), the Fourth Circuit considered whether the public disclosure bar would apply where a relator files an amended complaint after the disclosure is made, but the publicly disclosed claims had been included in a prior pleading that predated the disclosure.

In 2007, the Supreme Court ruled that the public disclosure bar inquiry applies to “the allegations in the original complaint as amended[,]” meaning that the amended complaint should be used to evaluate whether the bar applies. Rockwell International Corp. v. United States, 549 U.S. 457, 473–74 (2007) (emphasis in original). Citing Rockwell, the Eastern District of Virginia ruled that only the most recent complaint was relevant to the public disclosure analysis and dismissed relators’ case because the last pleading was filed after the public disclosure. United States ex rel. Beauchamp v. Academi Training Ctr., Inc., 933 F. Supp. 2d 825, 845 (E.D.Va. 2013).

The Fourth Circuit reversed, concluding that “the determination of when a plaintiff’s claims arise for purposes of the public-disclosure bar is governed by the date of the first pleading to particularly allege the relevant fraud and not by the timing of any subsequent pleading.” Beauchamp, 816 F.3d at 46. Thus, because the relators “sufficiently pled” the fraudulent scheme prior to the public disclosure, the bar did not apply. Id. Although this decision clarifies the impact of filing a subsequent amended complaint, it raises a number of other questions. Most notably, what does it mean to “particularly allege” and “sufficiently ple[a]d” the relevant fraud? Does the prior pleading have to meet the standards of Federal Rules of Civil Procedure 9(b) and 12? Or is there a different standard that applies?

E. Developments Related to the FCA’s Falsity, Scienter, and Materiality Requirements

1. HIPAA, Data Privacy, and the FCA Collide in the Sixth Circuit

In a potentially important decision exploring the intersection of data privacy laws and the FCA, the Sixth Circuit declined to find that an alleged Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (“HIPAA”) violation gave rise to liability under the FCA.

In United States ex rel. Sheldon v. Kettering Health Network, 816 F.3d 399 (6th Cir. 2016), a qui tam relator alleged that a health care network violated the FCA when it received incentive payments from the government after allegedly falsely certifying compliance with electronic records requirements. The Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH Act) requires health care networks like the appellant to implement systems to protect electronic medical records. Id. at 411. The government incents compliance by paying health care networks that engage in “meaningful use” of software and other technology, but only after they certify compliance with more than 20 criteria, including certain HIPAA regulations. Id. at 403.

While allegedly engaging in an affair with a coworker, a Kettering Health Network (KHN) employee allegedly accessed his wife’s–the relator’s–Protected Health Information (PHI) stored by KHN. Id. at 405. KHN informed the relator of this breach by letter. Id. The relator subsequently filed her FCA qui tam action on the theory that KHN’s claims to the government for “meaningful use” funds must have been false because KHN certified compliance with various HIPAA regulations even though the relator’s PHI was compromised. Id. at 406.

The Sixth Circuit affirmed the district court’s dismissal of the suit, holding that the breach that compromised the relator’s PHI did not violate the HITECH Act because that statute mandates implementation of security systems, not total prevention of all data breaches. Id. at 411. Therefore, the relator failed to plead a plausible claim of false certification because her legal conclusion was faulty. Id. at 409. The court also noted that KHN’s letter to the relator to inform her of the breach was evidence that KHN has detection and investigation procedures. Id. at 409­–10.

As data security regulations proliferate throughout state and federal law, FCA cases premised on alleged failure to comply with those regulations may well increase. But Sheldon offers defendants one clue about how to defeat such claims.

2. The Ninth Circuit Explores the FCA’s Scienter Requirement

In its unpublished decision in United States ex rel. Ruhe v. Masimo Corp., No. 13–56789, 2016 WL 684608 (9th Cir. 2016), the Ninth Circuit upheld the district court’s grant of summary judgment on behalf of defendant Masimo Corporation. While the primary basis for affirming summary judgment was the absence of falsity, lack of scienter was a second independent ground to reach that result. The court held that where a “product fails to perform well” despite its FDA clearance and validation by independent labs, the manufacturer has not made a knowingly false statement. “[A]necdotal feedback” complaining of inaccurate devices was not sufficient to rise to the level of a knowing fraud. Id. at *1.

3. The Second and Tenth Circuits Opine on the Scope of Materiality

In the wake of Escobar, interpretation of the materiality requirement will become increasingly important–especially in the context of implied certification cases. Two recent cases from the federal courts of appeal offer clues as to how courts have interpreted the materiality requirement under the FCA.

In United States ex rel. Thomas v. Black & Veatch Special Projects Corp., 820 F.3d 1162, 1164 (10th Cir. 2016), the Tenth Circuit clarified that the test for materiality in implied certification cases should focus on whether the alleged violation undermines the purpose of the underlying contract. Id. at 1169. Affirming the district court’s decision to grant summary judgment in favor of the defendant, the Tenth Circuit determined that defendant’s alleged practice of altering employee educational documents to obtain visas and work permits (in violation of contractual terms) were not material to the government’s payment decisions under the contract to provide components for an electrical power project in Afghanistan. Id. at 1172–73. The court further clarified that, in cases involving violations of a “tangential or minor contractual provision, the plaintiff may establish materiality by coming forward with evidence indicating that, despite the tangential nature of the violation, it may have persuaded the government not to pay the defendant.” Id. at 1171.

The court’s analysis provides some insight into, first, how the Tenth Circuit might conceptualize the interplay between a contract’s purpose and alleged violations when assessing whether a particular provision is merely a “tangential” or “minor” one and, second, what evidence the court considers when determining whether a violation nonetheless may have impacted the government’s decision to pay. The court emphasized that the relators did not allege that the defendant “falsely certified completion of a [p]roject component or compliance with a performance requirement,” or that the defendant “provided deficient work on the [p]roject or attempted to cover up any such deficiency.” Id. The court also noted that relators relied on “general regulatory provisions incorporated by reference into all international government contracts[,]” as opposed to “[p]roject-specific provisions.” Id. at 1172. Thus, despite the contract’s far-reaching compliance requirements, the defendant’s alleged alteration of supporting personal documents did not undermine the contract’s purpose of providing electricity to the relevant areas. Id.

Moreover, when evaluating whether the alleged violation still may have affected the government’s decision to pay, the Tenth Circuit emphasized that the government neither withheld payment after learning of the allegation, nor demanded a refund of payments already made. Id. Rather, the government paid for the defendant’s work “without objection or reservation” and even awarded additional work, despite being “aware that the evidence strongly suggested” that the defendant altered documents. Id. The Tenth Circuit rejected arguments focusing on the government’s actual knowledge of the alleged violations, reiterating that “evidence of the government’s inaction after learning of alleged violations [is] sufficient to establish the lack of materiality.” Id. at 1174.

At a more granular level, the Seventh Circuit explained in United States ex rel. Garbe v. Kmart Corp., No. 15-1502, 2016 WL 3031099 (7th Cir. May 27, 2016), that allegedly false claims can satisfy the materiality requirement even in cases involving private and intermediary payors. Characterizing the defendant’s arguments as “presentment in materiality clothing,” id.at *5, the Seventh Circuit held that alleged false claims can be material if those false claims have the capacity to influence payment decisions of the relevant decision-making body–irrespective of whether that decision-maker is the government itself, id. at *4.

Because the Fraud Enforcement and Recovery Act of 2009 (FERA) incorporated “false claims to intermediaries or other private entities that either implement government programs or use government funds[,]” id. at *5, and because the materiality rule under FERA “requires only that the false record or statement influence the ‘payment or receipt of money or property[,]'” the Seventh Circuit clarified that “no government decision is required” to establish a case under the FCA, id. at *4 (quoting 31 U.S.C. § 3729(b)(4)) (emphasis in original). Rather, the plaintiff need only show that the defendant’s allegedly false claims were material to the “receipt of more money than [the defendant] should have gotten”–that is, the misstatements had to be “capable of influencing[ ] the decision-making body to which [they were] addressed.” Id. (quoting Neder v. United States, 527 U.S. 1, 16 (1999)) (internal quotation marks omitted) (alteration in original). Because the relator presented evidence that the defendant used prices higher than those charged to customers through its discount programs when submitting reimbursement requests to the insurance companies, any false claims “were the basis of the federal monies” that defendant received and were thus material. Id. at *4.

4. The Second Circuit Issues a FIRREA Opinion That May Limit FCA Falsity Theories

In a case that originated as a qui tam FCA case in which the government intervened but ultimately tested the limits of the Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act of 1989 (FIRREA), the Second Circuit held that the breach of a contractual promise can “only support a claim for fraud upon proof of fraudulent intent not to perform the promise at the time of contract execution.” United States ex rel. O’Donnell v. Countrywide Home Loans, Inc., Nos. 15–496 & 15–499, 2016 WL 2956743, at *9 (2d Cir. May 23, 2016). Because the government failed to show that the financial institution defendants made a knowingly false statement via their “silent noncompliance” with the contracts, the Second Circuit reversed a $1.3 billion civil penalty. Id. at *3–4.

By way of background, the government alleged that the defendants entered into contracts to sell “investment quality” mortgages to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac but, in fact, sold them poorer-quality mortgages. At trial, “the jury was charged . . . as to a theory of fraud through an affirmative misstatement.” Id. at *10. The crux of the case, therefore, was whether the defendants’ initial representations of “investment quality” were intentional falsehoods. To prove this, the Second Circuit reasoned, the government had to show “that at the time the contracts were executed Countrywide never intended to perform its promise of investment quality.” Id. (emphasis added). Absent such proof, the defendants may have committed a willful breach of contract by knowingly selling mortgages that failed to meet the “investment quality” pedigree, but not “fraud.”

The court’s reasoning regarding FIRREA’s elements may undermine FCA suits premised on breaches of contract. Indeed, the Court explained that it was assessing “the proof that the federal fraud statutes require,” id. at *10, and the FCA is one such statute.

F. Developments in Costs and Awards

1. Courts Substantially Reduce Damage Awards

In United States ex rel. Wall v. Circle C Construction, LLC, 813 F.3d 616 (6th Cir. 2016), the Sixth Circuit reversed a $763,000 damages award based on false claims resulting from non-compliance with Davis-Bacon wage requirements, remanding the case with instructions to enter an award of $14,748. The government argued that defendant’s work was “valueless” because it was “tainted by . . . [the] underpayment to its electricians.” Id. at 617. The Sixth Circuit disagreed, noting that the fact that the government continued to “turn[] on the lights every day” belied the government’s damages claim. Id. The court indicated that full contract damages were appropriate if “the goods were worthless because they were dangerous to use” or “some unalterable moral taint makes the goods worthless to the government.” Id. at 618. But where “simply writing a check can make up the difference,” full contract damages should not be awarded. Id. The government also argued that it was entitled to recover the entire cost of the contract because it would have suspended payments had it known that defendant was non-compliant. The Sixth Circuit, however, held that “[i]n determining actual damages, . . . the relevant question is not whether in some hypothetical scenario the government would have withheld payment, but rather, more prosaically, whether the government in fact got less value than it bargained for.” Id. at 618. Because the only value the government did not receive was the difference between the Davis-Bacon wages and what was actually paid, the court reduced the damages award accordingly. Id.

In another case, the Southern District of Ohio drastically reduced its earlier $657 million damage award against United Technologies Corporation on remand from the Sixth Circuit. United States v. United Techs. Corp., No. 3:99-CV-093, 2016 WL 3141569, at *8 (S.D. Ohio June 3, 2016). The Sixth Circuit originally rejected the district court’s damages calculations in 2010, instructing the court to more carefully calculate actual damages as “the difference between what the government paid and what it should have paid.” United States v. United Techs. Corp., 626 F.3d 313, 322 (6th Cir. 2010), as amended (Jan. 24, 2011). On remand, the district court found the government had proved no actual damages under the FCA, and the Sixth Circuit, on a second appeal, confirmed that “[t]he government had the burden of proving damages, and it never did.” United States v. United Techs. Corp., 782 F.3d 718, 735–36 (6th Cir. 2015). On remand for the second time, the district court ruled that the government was entitled under common law theories to recover the amount of profits allegedly received as a result of Defendants’ wrongdoing, not the profits that would have been received under the initial contract price. Based on the amounts actually paid by the government, the district court determined that the government could recover disgorgement of $1,176,619, far less than the $23,752,721 claimed by the government. 2016 WL 3141569, at *8.

2. The Recovery of Attorneys’ Fees and Costs by Defendants

In Associates Against Outlier Fraud v. Huron Consulting Group, Inc., 817 F.3d 433, 436 (2d Cir. 2016), the Second Circuit held that the FCA’s fee shifting provision (31 U.S.C. § 3730(d)(4)) does not preclude the defendant from recovering taxable costs pursuant to Rule 54 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, even if the relator’s claim was not found to be frivolous. The Eighth, Ninth, and Tenth Circuits have already issued similar decisions, with no circuit ruling to the contrary.

G. Miscellaneous Procedural Developments

1. Attorney-Relator Disqualified

A recent decision from the Fifth Circuit highlights the potential pitfalls involved when attorneys serve as qui tam relators. United States ex rel. Holmes v. Northrop Grumman Corp., No. 15-60414, 2016 WL 1138264 (5th Cir. Mar. 23, 2016). The attorney-relator in Holmes had previously represented an insurance company in arbitration and court proceedings relating to an insurance coverage dispute against Northrop Grumman following Hurricane Katrina. Id. at *1. Using documents and information obtained during discovery related to that dispute, the attorney subsequently filed a FCA lawsuit against Northrop Grumman for allegedly defrauding the Navy by using government funds allocated for expenses related to Hurricane Katrina to cover cost overruns that had occurred before the storm. Id. at *1-2.

But the Fifth Circuit affirmed the district court’s decision to disqualify the attorney-relator and to dismiss the case. According to the Fifth Circuit, disqualification was appropriate because the relator committed several ethical violations, including violating the duty of loyalty by taking a position in the FCA lawsuit directly contrary to his client’s position in the insurance coverage dispute. Id. at *3. More importantly, the attorney had violated a protective order and his duty of candor to the court in the insurance coverage dispute proceedings by falsely representing that he would not use the documents obtained in discovery for any other purpose. Id. at *3. The Fifth Circuit also affirmed dismissal of the case (without prejudice to the government), holding that it would “greatly prejudice Northrop Grumman” to proceed on a record developed through the “fruits” of the attorney’s “unethical conduct.” Id. (citation omitted).

2. Retroactivity of FERA

We have previously reported on FERA, which expanded the scope of potential FCA liability in response to the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Allison Engine Co. Inc. v. United States ex rel. Sanders, 553 U.S. 662 (2008). Among other things, FERA lowered the threshold for FCA liability for false statements by eliminating a purpose requirement the Supreme Court had imposed in Allison Engine. FERA’s retroactivity provision, section 4(f)(1), provided that the amendments applied to “all claims under the False Claims Act that are pending on or after” June 7, 2008, two days before the Allison Engine decision.

Since its enactment in 2009, courts have reached different conclusions as to the scope of FERA’s retroactive application. The majority of the circuits, including the Second, Sixth, Fifth, and Seventh, have concluded that FERA’s reference to “claims” in the retroactivity provision meant all FCA “cases” pending as of June 7, 2008, and not merely individual “claims” for payment issued before that date. The Ninth and Eleventh Circuits have reached the opposite conclusion, limiting application of FERA to individual claims that post-dated June 7, 2008.

In May, the Seventh Circuit stated in United States ex rel. Garbe v. Kmart Corp. that it had “no trouble” reaffirming its view that FERA’s reference to “claims” in the statute’s retroactivity provision meant that the amendments applied to all FCA “cases” pending on or after June 7, 2008, and does not mean merely “request[s] or demand[s] for . . . money or property.” No. 15-1502, 2016 WL 3031099, at *7 (7th Cir. May 27, 2016). Although the Seventh Circuit had twice reached the same conclusion in earlier opinions, the decision in Garbe involved a more in-depth analysis of the issue. After examining the text and structure of FERA, and Congress’ intent, the Seventh Circuit concluded that its interpretation of “claims” to mean “cases” “best reflects the text and structure of the statute” and Congress’ intent to overrule Allison Engine. Id. at *5–7. The Seventh Circuit rejected the contrary positions of the Ninth and Eleventh Circuits, noting that the contrary holdings came in footnotes in each case and that none of those cases “addressed the question with any analysis.” Id. at *6.

Similarly, the Eleventh Circuit reaffirmed its view last year (albeit in another footnote) that FERA applies only “retroactively to claims pending for payment on or after June 7, 2008.” Urquilla-Diaz v. Kaplan Univ., 780 F.3d 1039, 1045 n.6 (11th Cir. 2015). This continued divergence amongst the Circuit’s positions suggests that the split over FERA retroactivity is not likely to be resolved absent Supreme Court review.

H. Miscellaneous Substantive Developments

1. Defining “Persons” Subject to the FCA

The FCA subjects to liability “any person” who knowingly submits a false claim to the government for approval. 31 U.S.C. § 3729(a)(1). The United States Supreme Court has held that the term “person” in the FCA does not include a state, see Vt. Agency of Nat. Res v. United States ex rel. Stevens., 529 U.S. 765 (2000), but has not yet addressed the question of how to determine whether an entity is a state agency for purposes of the FCA.