Investors’ Right to Seek NAFTA Protections Set to Expire on 1 July 2023

Client Alert | March 6, 2023

On 1 July 2023, the North American Free Trade Agreement (“NAFTA”)—which has helped to facilitate trade among the United States, Canada, and Mexico for over 25 years—is set to expire. NAFTA was terminated and replaced by a new treaty, the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (“USMCA”), on 1 July 2020. However, the USMCA provides for a three-year “sunset period” following the termination of NAFTA, during which North American investors could still obtain certain investment protections under NAFTA for their “legacy claims” (i.e., claims relating to investments that were established or acquired prior to 1 July 2020).[1] That sunset period will end on 1 July 2023, following which investors will only be able to resort to the USMCA’s more limited protections. As described below, North American investors are strongly encouraged to consider whether they have any legacy claims under NAFTA in connection with their investment in Canada and the United States, and especially in Mexico (in view of the far-reaching regulatory changes in Mexico discussed below) and file their formal notices no later than 1 April 2023.

I. NAFTA’s Sunset Period

NAFTA entered into force on 1 January 1994, and expired on 1 July 2020, upon the entry into force of the USMCA.[2] Under Annex 14-C of the USMCA, investors can bring NAFTA “legacy investment claims” for a period of three years after the termination of NAFTA, or until 1 July 2023.[3] These claims are limited to investments “established or acquired between January 1, 1994, and the date of termination of NAFTA,” “and in existence on the date of entry into force of” the USMCA.[4] Arbitrations already initiated under NAFTA will not be affected by the expiration of the sunset period.[5]

While the sunset period will end on 1 July 2023, investors must notify the respondent State at least 90 days before the claim is submitted, i.e., by 1 April 2023, to comply with NAFTA’s requirements.[6] As the notice period is even longer for claims arising from taxation measures (six months), any legacy claims relating to taxation matters have now since expired.[7]

A. Implications for Investment Disputes Involving Canada or Canadian Investors

Canada did not sign the USMCA’s investor-state dispute mechanism (Chapter 14). This means that investment arbitration is no longer available for claims by U.S. and Mexican investors against Canada under Chapter 14—nor to Canadian investors in the other two USMCA States.

However, other investment treaty protections would apply to Canadian investors in Mexico and Mexican investors in Canada. For example, both Canadian and Mexican investors may submit their disputes to arbitration under the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (“CPTPP”).[8]

U.S. investors, on the other hand, would have no recourse to arbitration under the CPTPP because the United States is not a signatory. NAFTA therefore provides the last opportunity for Canadian investors in the U.S. or U.S. investors in Canada to arbitrate their claims.

B. Implications for Investment Disputes Involving Mexico or Mexican Investors

As noted above, Mexican investors in the United States and U.S. investors in Mexico may still submit claims to arbitration under Chapter 14 of the USMCA (which is modelled after Chapter 11 of NAFTA). However, the new investment treaty regime contains important procedural and substantive differences relative to NAFTA. As described below, for many U.S. and Mexican investors, a legacy claim under NAFTA will offer higher substantive protections and simpler procedural requirements and may be more advantageous than filing under the USMCA.[9]

II. Potential Procedural Limitations

Under NAFTA, an investor can bring an arbitration claim directly before a NAFTA investment panel assuming basic procedural requirements are met.[10] Under Chapter 14 of the USMCA, by contrast, an aggrieved investor must first exhaust local remedies in the national courts of the host State before resorting to international arbitration.[11] To exhaust local remedies, an investor must either “obtain a final decision from a court of last resort of the respondent” or wait 30 months from the date on which proceedings were initiated.[12] These provisions do not apply to the extent recourse to domestic remedies was “obviously futile.”[13]

The exhaustion requirement does not apply, however, to investors with a “covered government contract” (“a written agreement between a national authority” of the United States or Mexico, “and a covered investment or investor” of the other Party).[14] It likewise does not apply to investors engaged in a “covered sector,” which includes oil and natural gas, power generation, telecommunications, transportation, and transportation infrastructure.[15]

III. Potential Substantive Limitations

Under NAFTA’s Chapter 11, an investor can bring a range of investment treaty claims against the host State, including that the host State (directly or indirectly) expropriated its investment, failed to afford the investor or its investment the minimum standard of treatment, national treatment, and most-favored-nation treatment.[16]

Under the USMCA, however, many investors can no longer bring claims for indirect expropriation, and they may not submit to arbitration claims for violations of the minimum standard of treatment.[17]

Again, investors with covered government contracts or in covered sectors enjoy greater substantive protections under the USMCA. They may arbitrate claims for violations of all of Chapter 14’s substantive provisions, including indirect expropriation.[18] However, it remains to be seen whether in practice the scope of those rights may be more limited than under NAFTA.[19]

IV. Why Are NAFTA Legacy Claims Important in the Current Investment Context in Mexico?

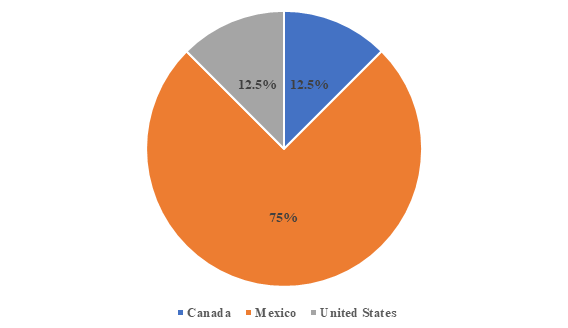

In the North American context, a disproportionate number of NAFTA claims has been filed or announced against Mexico in recent years. Mexico is the respondent in 12 of the 16 publicly known pending or announced NAFTA arbitrations involving legacy claims—or 75%.[20] By comparison, there are two pending NAFTA arbitrations against the United States[21] and two against Canada.[22] Mexico has faced numerous investment treaty claims outside of the NAFTA context as well and has been the respondent in approximately 40 arbitrations, including 8 disputes that are currently pending before the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (“ICSID”) in Washington, D.C.

Figure 1. Number of NAFTA Legacy Disputes Filed or Announced Against the NAFTA States (as of March 2023)

A number of these claims relate to the Mexican Government’s regulatory and legislative measures to transform how the country’s energy, electricity, and mining sectors are governed:

- As discussed in our previous client alert, recent amendments to Mexico’s Hydrocarbon Law and Electricity Industry Law have accorded preferential treatment to State-owned companies and granted the Mexican Government broad discretion to suspend or refuse operating permits to private companies.[23] The changes to the electricity legislation were subsequently upheld by the Mexican Supreme Court.[24] Mexico’s President, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, has argued that such reforms are necessary to rebalance the economy away from private actors and in favor of the public sector.[25] Some of the concerns involving certain Canadian investors were reportedly resolved in January 2023.[26]

- The Mexican Government has also sought to solidify State control of the energy sector in the Mexican Constitution. Earlier this year, for example, Mexico’s lower house of congress defeated a proposed constitutional amendment that would have allowed Mexico’s State-owned electricity company to produce at least 54% of the country’s electricity, limited private participation in the market, and consolidated independent energy regulators into the federal government.[27]

- In April 2022, the Government also passed a bill nationalizing the country’s lithium mining sector and allowing the Government to take over “other minerals declared strategic.”[28] Mexico has indicated that it will review all contracts held by foreign companies to explore for lithium deposits in the country.[29] In January 2023, Mexico announced that the first concessions to a State-owned company would be awarded in February 2023.[30]

Some of these developments led the United States and Canada to invoke in July 2022 the State-to-State dispute settlement provisions under Chapter 31[31] of the USMCA over Mexico’s energy policies.[32] The discussions among the three countries are still ongoing.[33]

These inter-State consultations, however, are limited to the specific concerns surrounding Mexico’s energy policies. They would not address other sectors, or even necessarily solve the specific concerns or losses of Canadian or U.S. investors in the energy sector. NAFTA investors with legacy investment claims would therefore be well advised to carefully assess the status, operation, and viability of their investments in Mexico in this evolving investment climate and whether they need to seek investment protections under NAFTA by 1 April 2023.

V. Conclusion

Under the USMCA’s three-year sunset period, investors have until 1 July 2023, to submit claims involving investments created or acquired during NAFTA’s existence to arbitration. Because investor-state arbitration will no longer be available to Canadian investors or for investments in Canada, this category of investors should carefully consider whether they have a viable claim under NAFTA. As between Canada and the United States, NAFTA provides the last resort to international investment arbitration. Similarly, due to the USMCA’s generally less favorable two-tiered dispute resolution regime, U.S. and Mexican investors with legacy claims under NAFTA would be well advised to consider whether to avail themselves of the soon-to-expire treaty protections.

_______________________

[1] United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (hereinafter “USMCA”), Annex 14-C.

[2] USMCA Protocol; see also Press Release, Office of the U.S. Trade Rep., USMCA To Enter Into Force July 1 After United States Takes Final Procedural Steps For Implementation (Apr. 24, 2020).

[3] USMCA Annex 14-C, (1)–(3).

[4] Id., Annex 14-C, (4), 6(a).

[5] Id., Annex 14-C, para. 5.

[6] North American Free Trade Agreement (hereinafter “NAFTA”) Art. 1119.

[7] Id., Art. 2102.

[8] Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans Pacific Partnership Agreement, Annex 1-A. The CPTPP entered into force for both Canada and Mexico on December 30, 2018. See About the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, Gov’t of Canada.

[9] The USMCA also excludes specific types of claimants, such as investors that are “owned or controlled by a person of a non-Annex Party that the other Annex Party considers to be a non-market economy, that is a party to a qualifying investment dispute.” See USMCA, Annex 14-D, para. 1.

[10] See NAFTA Arts. 1116–1117, 1121 (setting out the procedural requirements for the submission of claims to arbitration).

[11] No claim may be submitted to arbitration unless “the claimant or the enterprise . . . first initiated a proceeding before a competent court or administrative tribunal of the respondent with respect to the measures alleged to constitute a breach.” USMCA Art. 14.D.5(1)(a).

[12] Id., Art. 14.D.5(1)(b).

[13] Id., Art. 14.D.5(1)(b), footnote 25.

[14] Id., Annex 14-E, (6)(a).

[15] Id., Annex 14-E, (6)(b).

[16] Pursuant to NAFTA Art. 1116(1)(a) and 1117(1)(a), an investor may submit a claim to arbitration on its own behalf or on behalf of an enterprise, respectively, for a violation of Chapter 11, Section A of NAFTA. See NAFTA Arts. 1116(1)(a) and 1117(1)(a). Section A includes NAFTA’s provisions regarding national treatment (Art. 1102), most-favored-nation treatment (Art. 1103), and minimum standard of treatment (Art. 1105).

[17] Compare NAFTA Arts. 1105, 1116–1117, 1110 (permitting claims for violations of minimum standard of treatment and direct and indirect expropriation) with USMCA Art. 14.D.3(1)(a), (b) (permitting claims for breach of provisions regarding national treatment, most-favored-nation treatment, and direct expropriation).

[18] See USMCA Annex 14-E, (2).

[19] For example, interpretation questions may arise with respect to the minimum standard of treatment (USMCA, Art. 14.6.4) and the scope of indirect expropriation (Annex 14-B, 3(a)(i)–(iii)), especially in relation to measures “designed and applied to protect legitimate public welfare objectives, such as health, safety and the environment” (USMCA Annex 14-B, 3(b)).

[20] See Silver Bull, Press Release, Silver Bull Announces Commencement of Legacy NAFTA Claim Against Mexico (Mar. 2, 2023); Goldgroup Resources, Inc. v. United Mexican States, ICSID Case No. ARB/23/4; Monterra Energy, Press Release, Monterra Energy Takes Legal Action Against Closure of its Tuxpan Facility by Submitting to the Government of Mexico a Notice of Intent Under NAFTA (Feb. 22, 2022); Access Business Group LLC v. United Mexican States, Notice of Intent to Submit a Claim to Arbitration, Oct. 11, 2022; Finley Resources Inc., MWS Management Inc., and Prize Permanent Holdings, LLC v. United Mexican States, ICSID Case No. ARB/21/25; First Majestic Silver Corp. v. United Mexican States, ICSID Case No. ARB/21/14; Doups Holdings LLC v. United Mexican States, ICSID Case No. ARB/22/24; Coeur Mining v. United Mexican States, IA Reporter; Sepadeve International LLC v. United Mexican States, Notice of Intent (Sept. 4, 2020); AMERRA Capital Management, LLC, AMERRA Agri Fund, LP, AMERAA Agri Opportunity Fund, LP, and JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A. v. United Mexican States, Notice of Intent (Dec. 3, 2020); L1bero Partners LP and Fabio M. Covarrubias Piffer v. United Mexican States, Notice of Intent (Dec. 30, 2020); Margarita Jenkins, Maria Elodia Jenkins, and Juan Carlos Jenkins v. United Mexican States, Notice of Intent (July 19, 2021).

[21] See TC Energy Corp. and TransCanada PipeLines Ltd. v. United States of America, ICSID Case No. ARB/21/63; Alberta Petroleum Marketing Commission v. United States of America, Notice of Intent to Submit a Claim to Arbitration, Feb. 9, 2022.

[22] See Koch Industries Inc. and Koch Supply & Trading, LP v. Canada, ICSID Case No. ARB/20/52; Windstream Energy LLC v. Canada, PCA Case No. 2021-26.

[23] Mexico’s Reforms to Hydrocarbon Law and Electricity Industry Law May Violate Investment Treaty Protections, Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP (June 1, 2021).

[24] Mexico’s Top Court Upholds Changes to Power Law in Win for President, Reuters (Apr. 7, 2022).

[25] Id.

[26] Mexico’s President announced that he had met with representatives from four Canadian companies, including Canada’s second-largest pension fund, and successfully resolved the companies’ concerns regarding Mexico’s electricity sector policies (including issues over self-supply electricity contracts and permits allowing energy connections for new projects). See Mathieu Dion & Maya Averbuch, Mexico’s AMLO Met with Canada Pension Giant Amid Energy Feud, Bloomberg (Jan. 18, 2023).

[27] Max de Haldevang & Michael O’Boyle, Mexico President’s Electricity Bill Fails to Pass Lower House, Bloomberg (Apr. 18, 2022).

[28] Mexico Nationalizes Lithium, Plans Review of Contracts, Reuters (Apr. 19, 2022).

[29] Mexico Creates State-Run Lithium Company, To Go Live Within 6 Months, Reuters (Aug. 24, 2022).

[30] Cody Copeland, US Urges Mexico to Open Up Lithium Production to Private Sector, Courthouse News Serv. (Jan. 17, 2023).

[31] Pursuant to Article 31.4 of the USMCA, the USCMA State Parties must engage in consultations within 30 days of the date of delivery of a request for consultations. See USMCA, Art. 31. If the issue that is the subject of consultations is not resolved within 75 days of delivery of the request, a State Party may request the establishment of a panel to rule on the dispute. Id. Art. 31.6. If a State Party refuses to comply with a decision rendered by a panel, the other State Parties may implement retaliatory measures. Id. Art. 31.19.

[32] Press Release, Office of the U.S. Trade Rep., United States Requests Consultations Under the USMCA Over Mexico’s Energy Policies (July 20, 2022); Press Release, Global Affairs Canada, Statement by Minister Ng on Canada Launching Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement Consultations on Mexico’s New Energy Policies (July 21, 2022).

[33] Mexico Invites U.S. Trade Team to Third Round of Energy Consultations, Reuters (Dec. 1, 2022).

The following Gibson Dunn lawyers prepared this client alert: Lindsey D. Schmidt, Maria L. Banda, and Brian Yeh.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these issues. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, any member of the firm’s International Arbitration practice group, or the following:

Lindsey D. Schmidt – New York (+1 212-351-5395, [email protected])

Maria L. Banda – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3678, [email protected])

Please also feel free to contact the following practice group leaders:

International Arbitration Group:

Cyrus Benson – London (+44 (0) 20 7071 4239, [email protected])

Penny Madden KC – London (+44 (0) 20 7071 4226, [email protected])

Rahim Moloo – New York (+1 212-351-2413, [email protected])

© 2023 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice. Please note, prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome.