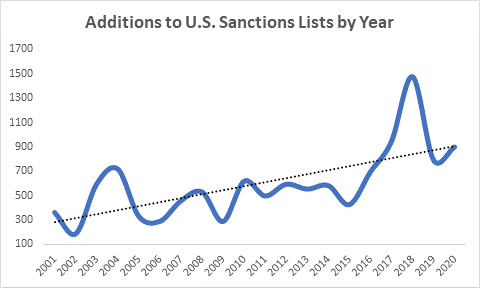

This update summarises the most significant reforms introduced by the New CBUAE Law and the implications for financial institutions operating in the UAE.

On 15 September 2025, the Federal-Decree Law No. 6 of 2025 Regarding the Central Bank Regulation of Financial Institutions and Activities and Insurance Business (the New CBUAE Law) was issued in the Official Gazette and became legally effective as of 16 September 2025 (Art.188). The New CBUAE Law repeals and replaces both Federal Decree Law No. 14 of 2018 (the “2018 Law”), which previously governed the Central Bank of the United Arab Emirates (CBUAE) and onshore financial institutions, and Federal Decree Law No. 48 of 2023, which regulated insurance activities.

The New CBUAE Law represents a significant overhaul of the financial regulatory framework of the United Arab Emirates (UAE). It consolidates the regulation of banks, payment service providers, and insurers under a single legislative umbrella, introduces new licensing requirements for emerging-technology providers, and imposes enhanced penalty and enforcement provisions.

We have summarised below the most significant reforms introduced by the New CBUAE Law and the implications for financial institutions operating in the UAE.

Criminal Sanctions Introduced for Unlicensed Financial Activities

Under the 2018 Law, the prohibition on carrying out financial activities without a license lacked corresponding sanctions. While the previous law established that no person could engage in regulated financial activities without a license from the CBUAE, it did not specify criminal penalties for breaches. The New CBUAE Law addresses this and the approach is now consistent with what we see in other jurisdictions, where engaging in regulated financial activities without authorisation constitutes a criminal offence.

Article 60 reaffirms the general prohibition on conducting any regulated activities without an appropriate license. It provides that only persons or entities duly licensed in accordance with the Law, together with its implementing regulations and decisions, may engage in or offer such activities within the State.

The key development lies in Article 170, which now expressly criminalises the conduct of carrying out unlicensed financial activities. Article 168 provides that, without prejudice to other penalties or measures, the CBUAE may impose administrative penalties and fines where a person is engaged in any of the activities specified in the law without a license.

Article 170 introduces a new criminal penalty for such conduct. Persons that engage in a licensed financial activity without a license may face imprisonment and/or a fine between AED 50,000 and AED 500 million, representing a significant increase over the penalties available under the 2018 Law. This is a notable development, and we may see increased enforcement in light of this new framework. Importantly, this change reflects the UAE’s commitment to strengthening the deterrent framework for unlicensed financial activities.

The prohibition on engaging in financial activities without a license applies to those entities operating outside the UAE and to those operating in the financial free zones such as the Dubai International Finance Centre and Abu Dhabi Global Market. Accordingly, any firm targeting UAE retail customers — even if licensed by a financial free zone regulator— may be subject to criminal sanctions under the Federal framework. Pursuant to Article 4 of Federal Decree Law No. 8 of 2004 such financial free zones remain subject to all federal laws (with the exception of federal civil and commercial laws) and the New CBUAE Law shall take precedence in the event of any conflict.

Express Prohibition on Unlicensed Communications Extends CBUAE’s Regulatory Perimeter

The New CBUAE Law also introduces some entirely new provisions, one of which is an express prohibition on conducting, or communicating in relation to, licensed financial activities without proper authorisation. This is a significant development that materially broadens the CBUAE’s regulatory perimeter to include promotional and marketing communications directed at UAE residents.

By virtue of Article 61(1)(h), advertising, marketing or promoting a licensable financial activity is expressly defined as a licensed financial activity in its own right. Accordingly, any person engaging in such activities must hold an appropriate license from the CBUAE. Article 60(3) reinforces this principle by stipulating that licensed financial activities and products may only be offered or conducted from within the UAE in compliance with the provisions of the Law and its implementing regulations.

The New CBUAE Law defines “communication” broadly, encompassing any form of communication or invitation, including by telephone, fax, email, internet or mobile phone, as well as invitations to enter into or conclude transactions relating to licensed activities.

Given this expansive definition, the New CBUAE Law captures not only conduct taking place within the UAE, but also communications made from abroad to persons in the UAE. As a result, unlicensed foreign firms that market or promote financial products or services to UAE residents, whether through online platforms or other digital means, now fall within the regulatory perimeter and risk breaching the New CBUAE Law’s prohibitions. Firms operating outside the UAE should therefore assess whether their remote or online communications could constitute the carrying on of a licensed activity into the State and whether local licensing or authorisation is required.

Regulatory Perimeter Extended to Virtual Assets and Facilitation of Decentralised Platforms

Another entirely new provision is Article 62, which expands the CBUAE’s regulatory perimeter to capture activities conducted through emerging technologies, including virtual assets and decentralised finance (DeFi) models.

Article 62 extends the scope of the licensing framework by providing that, subject to existing licensed activities, any person who engages in, offers, issues, or facilitates a licensed financial activity – by any means or through any medium – is subject to the licensing, regulatory, and supervisory authority of the CBUAE.

Importantly, this goes beyond simply prohibiting the carrying out of regulated activities without a license; it now expressly captures the facilitation of such activities, either directly or indirectly. This means that entities providing technological infrastructure, platforms, protocols, or digital tools that enable or support the delivery of financial services may themselves fall within the regulatory perimeter, even if they do not directly offer the underlying financial products or services.

By explicitly capturing facilitation, the New CBUAE Law ensures that firms cannot avoid regulatory oversight by characterising themselves solely as technology providers. Going forward, technology companies, payment processors, and DeFi operators will need to evaluate whether their business models could be deemed to facilitate licensed activities and therefore trigger a licensing requirement under the new framework.

Expanded Obligations for Licensed Financial Institutions (LFIs)

The New CBUAE Law also sets out an integrated framework of prudential, conduct, and consumer protection obligations for all LFIs.

Under Articles 114 and 130, LFIs must comply with all regulations, standards, and circulars issued by the CBUAE, including those governing capital adequacy, liquidity, governance, risk management, and related-party exposures. The CBUAE has authority to issue detailed governance and fit-and-proper rules for board members and senior management, strengthening accountability and oversight across the sector. The New CBUAE Law makes clear that the CBUAE may take all necessary measures and procedures and use all means necessary to ensure the proper functioning of LFIs.

On the conduct side, Articles 148 through 152 introduce a dedicated consumer protection regime, requiring LFIs to handle customer complaints through independent channels, maintain transparent product disclosures, implement anti-fraud measures, and promote financial literacy and inclusion.

Articles 183 and 184 confirm that during the transitional period, existing prudential and conduct regulations issued under the repealed 2018 Law continue to apply until replaced, ensuring regulatory continuity while the CBUAE phases in new standards under the updated framework (please refer to “Transitional Provisions and Legal Continuity” below).

Enhanced Resolution and Recovery Framework

Articles 142 through 146 of the New CBUAE Law introduce a comprehensive resolution and recovery regime for LFIs and insurers, positioning the UAE in line with leading international standards on financial stability and systemic risk mitigation. Under these provisions, the CBUAE is empowered to intervene early in cases of financial distress, impose corrective measures, and, where necessary, initiate resolution proceedings through a newly established Settlement and Resolution Authority. The framework provides the CBUAE with extensive tools, ranging from management replacement and capital restructuring to the transfer or sale of assets and liabilities, in order to ensure the orderly continuity of critical functions and protect depositors and policyholders. Article 144 codifies a clear creditor priority and loss allocation system whilst Articles 145 to 146 establish transparency obligations and oversight until full wind down. Any resolution, dissolution, or liquidation decision requires public notification through official channels, including publication in the Official Gazette and local newspapers, with a minimum three-month notice period to allow customers and creditors to safeguard their interests. The provisions also mandate the appointment and disclosure of the designated resolution or liquidation administrator, who is responsible for implementing the resolution plan and coordinating with affected stakeholders. The CBUAE retains supervisory authority over institutions throughout the resolution and liquidation process.

Collectively, these reforms mark a major step toward a risk based, internationally aligned resolution framework that underpins confidence in the UAE’s financial system.

Enforcement and Settlement

The New CBUAE Law introduces, for the first time, a negotiated settlement mechanism within the CBUAE’s enforcement framework. Under Article 168(6), the CBUAE may, at its discretion, enter into settlements with regulated entities or individuals in respect of administrative penalties and fines, in accordance with procedures and regulations to be issued in due course. We expect that the implementing regulations (once issued) will set out the criteria, documentation, and approval process for such settlements.

This provision creates a formal legal basis for the CBUAE to resolve supervisory breaches through proportionate, risk-based settlements, rather than solely through the imposition of fixed penalties. The new approach aligns the UAE’s enforcement framework with international best practice, allowing the regulator to recognise cooperation, remedial action, and the scale of impact when determining outcomes, while still preserving regulatory deterrence.

Transitional Provisions and Legal Continuity

Articles 183 to 185 of the New CBUAE Law establish a clear framework to ensure regulatory continuity and an orderly transition from the repealed legislation. All regulations, circulars, guidelines and decisions issued under the previous frameworks shall remain in full force and effect until expressly replaced by new instruments issued under the New CBUAE Law, with existing definitions and technical terms retaining their meaning during the interim period. Regulated institutions must regularise their position within one year from the Law’s effective date to align with the new requirements (although note that this one year period is extendable at the CBUAE’s discretion). At the same time, any provisions under the old framework that are inconsistent with the New CBUAE Law are repealed.

Collectively, these articles safeguard legal certainty and market stability while the CBUAE implements the new regulatory framework and issues updated prudential and conduct regulations.

Conclusion

Entities captured under the New CBUAE Law have one year from 16 September 2025 to bring their operations into compliance, and this one year may be extended as CBUAE deems appropriate. The new framework marks a significant shift in the UAE’s regulatory landscape, underscoring that the CBUAE and UAE authorities are taking enforcement and supervision seriously across all segments of the financial sector, ranging from unlicensed financial activities to emerging technologies.

If you have any concerns about how the New CBUAE Law may affect your business, please contact your regular Gibson Dunn advisor or any member of our UAE team.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these developments. If you wish to discuss any of the matters set out above, please contact any member of Gibson Dunn’s Financial Regulatory team, including the following members in Dubai:

Sameera Kimatrai (+971 4 318 4616, skimatrai@gibsondunn.com)

Aliya Padhani (+971 4 318 4625, apadhani@gibsondunn.com)

© 2025 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP. All rights reserved. For contact and other information, please visit us at www.gibsondunn.com.

Attorney Advertising: These materials were prepared for general informational purposes only based on information available at the time of publication and are not intended as, do not constitute, and should not be relied upon as, legal advice or a legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances. Gibson Dunn (and its affiliates, attorneys, and employees) shall not have any liability in connection with any use of these materials. The sharing of these materials does not establish an attorney-client relationship with the recipient and should not be relied upon as an alternative for advice from qualified counsel. Please note that facts and circumstances may vary, and prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome.

The establishment of the Real Property Division under the new ADGM Court Rules is a significant step toward supporting Abu Dhabi’s growing real estate market and addressing end-user requirements, with the Fast Track offering a route for the quick resolution of claims, providing parties with certainty and a way to resolve disputes efficiently.

Introduction

Gibson Dunn is proud to have partnered with the Abu Dhabi Global Market (ADGM) Courts for the Courts’ most significant reform project yet: the introduction of a new Real Property Division (including a simplified Short-Term Residential Lease procedure) and a Fast Track in the Commercial and Civil Division.

On 17 October 2025, the ADGM Courts published a series of amendments to their legislative and civil procedure framework, following the ten-fold geographical increase of the Court’s jurisdiction with the ADGM’s territorial expansion to Al Reem Island. The amendments introduce new Court rules and procedures designed to expedite and streamline court processes. These changes will allow the Court to more efficiently resolve real property and commercial disputes, and to implement an armoury of real property-specific remedies, for the benefit of practitioners and Court users.

Gibson Dunn is proud to have led this reform project, with an international team spanning our UAE, London, New York and Paris offices. The team, led by Nooree Moola, Lord Falconer, Robert Spano, Helen Elmer, and Praharsh Johorey, brought diverse experience which allowed the ADGM to benchmark against international best practices from a variety of jurisdictions.

The changes include:

- a new Real Property Division, which will hear all real property claims. These changes create bespoke procedural rules that operate on a fast-track basis. They also provide for a range of important real property-specific remedies.

- a new “Fast Track” for the Commercial and Civil Claims Division, which ensures that certain straightforward commercial and civil claims can be resolved efficiently and expeditiously, while also making the Court procedures more accessible and manageable.

- a new practice direction for short-term residential lease claims, which sets out clear, user-friendly guidelines for resolving disputes relating to residential leases with a term of less than four years.

A summary of the amendments made in these instruments is set out below.

The Real Property Division

The ADGM’s geographical expansion into Al Reem Island in 2023 gave rise to a tenfold increase in its jurisdiction, and, unsurprisingly, larger volumes and new categories of claims and disputes bespoke to the residential and commercial property sector. Following this, the ADGM issued its “New Real Property Framework” in 2024, which expanded upon the types of property-specific claims and applications that could be made to the Court.[1]

To efficiently resolve these disputes, the updated ADGM Court Rules now establish a “Real Property Division” within the Court, which seeks to provide a streamlined and efficient service to the approximately 30,000 residents and 1,500 businesses that will need access to residential and commercial property dispute resolution. It provides bespoke and user-friendly procedures, practice directions and court forms.

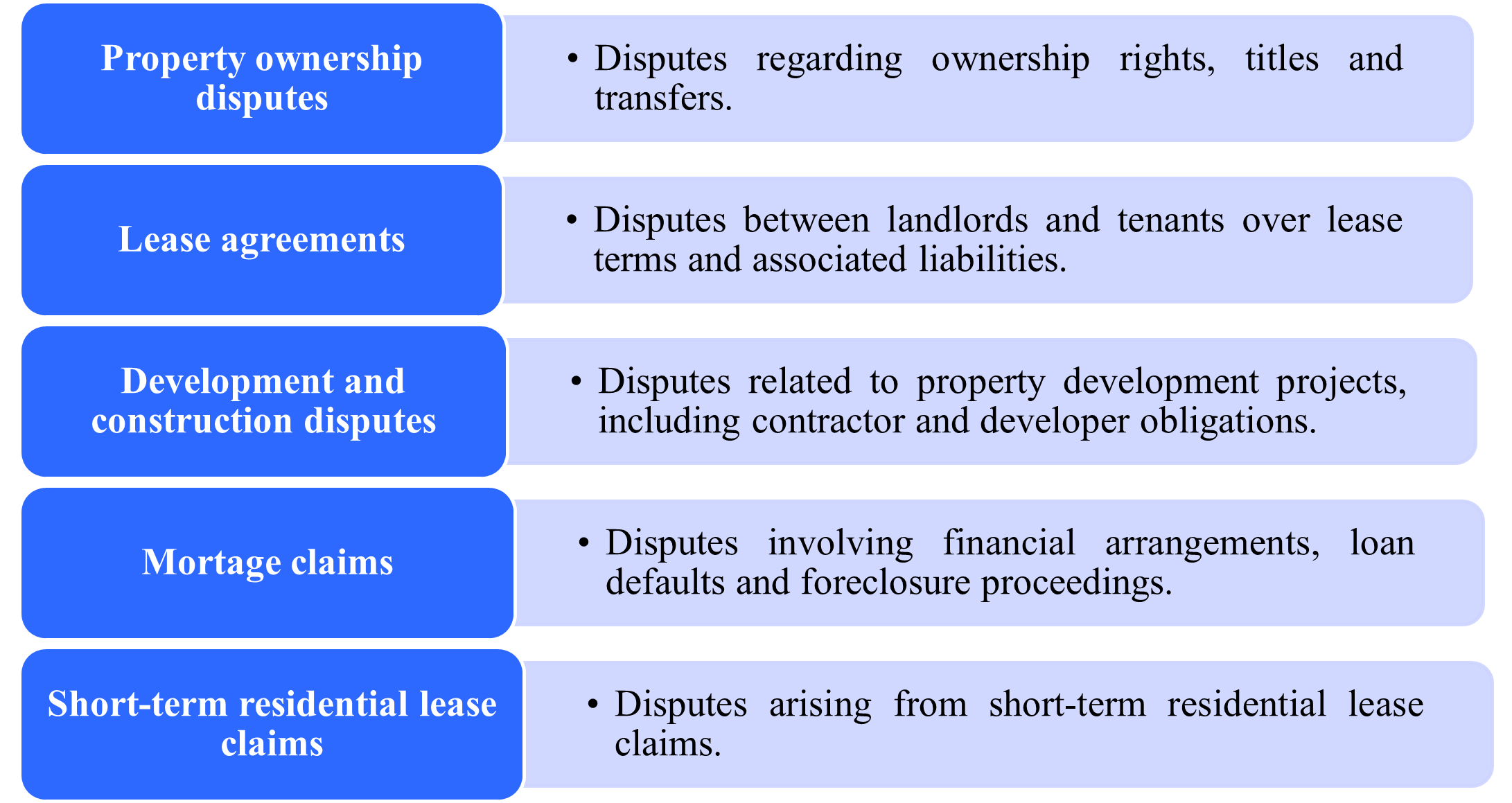

Disputes that will be heard in the Real Property Division include:

|

The ADGM Courts did not previously have a specific procedural framework for real property claims and applications. With the current changes, a new Real Property Division has been introduced within the ADGM Court of First Instance, which has exclusive jurisdiction over all ADGM real property claims. This will serve as a “one-stop-shop” for resolving real property claims, allowing users to easily identify the procedures applicable to their real property claim. The Division has an inherently fast-tracked and easy-to-understand process, with procedures tailored specifically for real property claims and remedies.

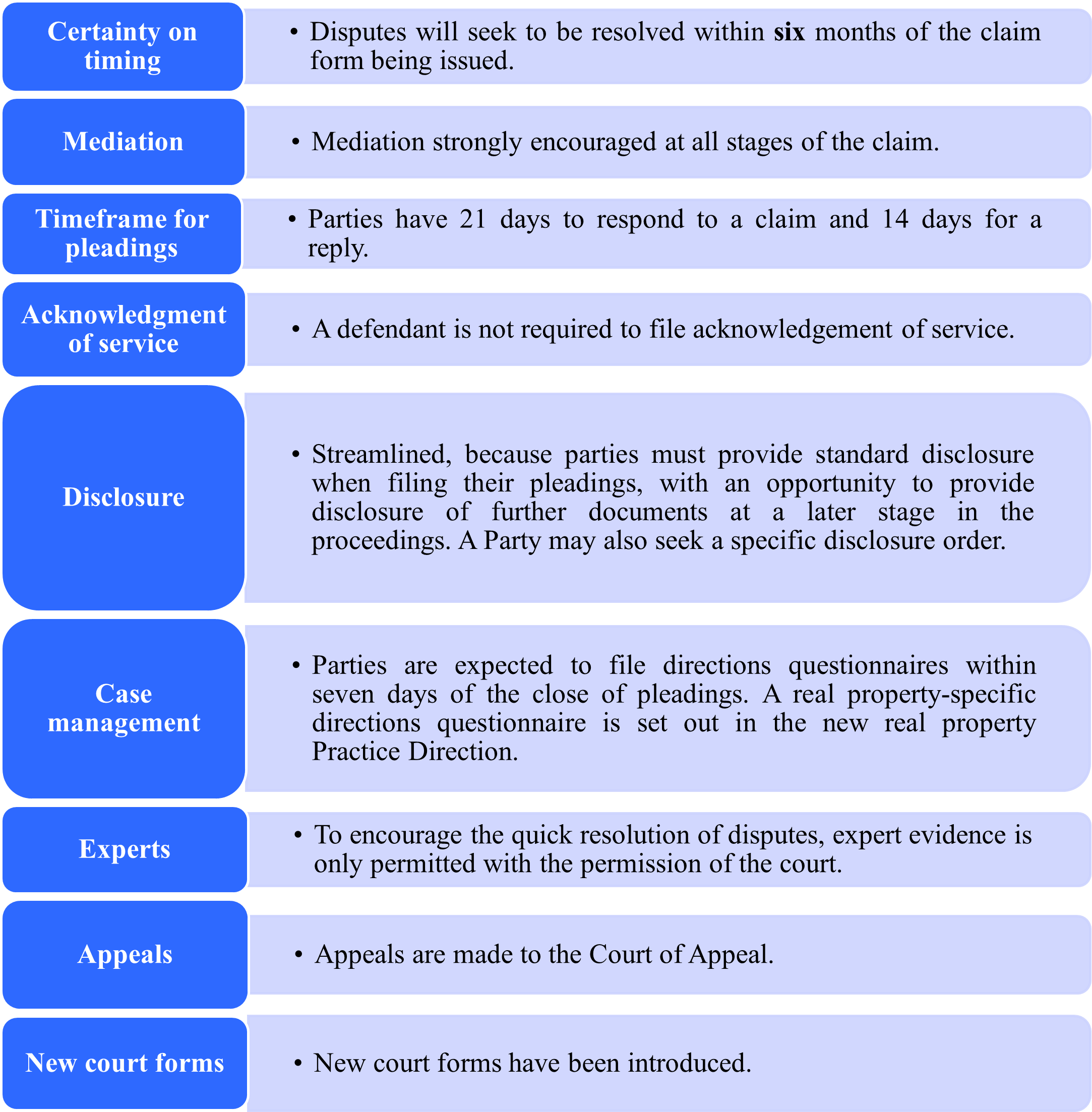

Some of the key features of the Real Property Division are:

|

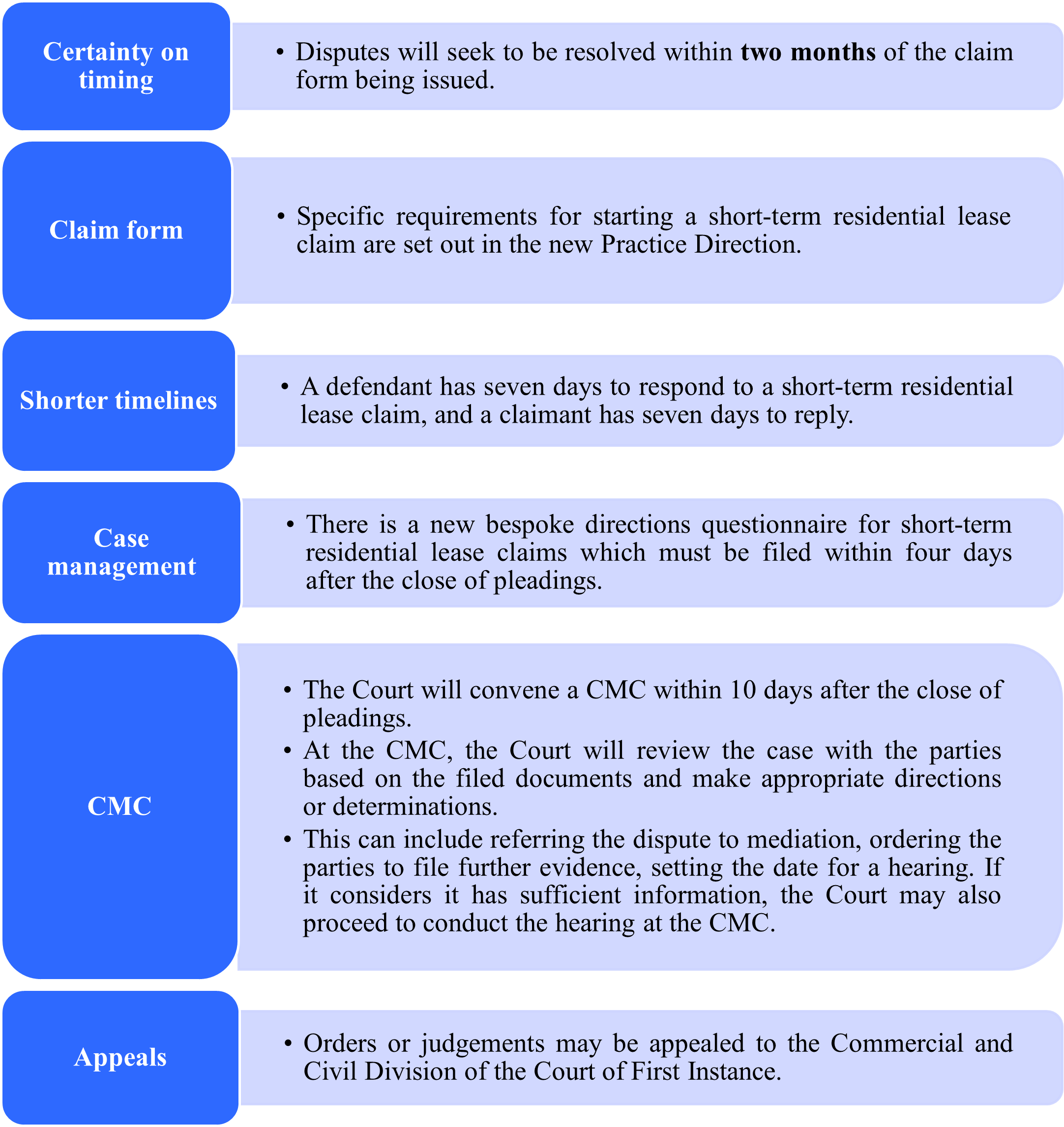

Short-Term Residential Lease Claims

The ADGM Courts have also introduced a bespoke, user-friendly process for “short-term residential lease claims”, i.e., claims arising from leases of residential property with a term of less than four years. These changes recognise the need to cater for higher volumes of relatively low-value disputes, as well as litigants-in-person. The framework is significantly streamlined, in that claims are intended to be disposed of within two months from start to finish. The framework also allows litigants to represent themselves with ease.

The key features are as follows:

|

“Fast Track” Procedure for Commercial and Civil Claims

New procedures have also been introduced in the Commercial and Civil Division. Key among these changes is the introduction of a “Fast Track” procedure, which will expedite the resolution of more straightforward commercial and civil claims.

The key features of the Fast Track procedure are set out in the Court Procedure Rules and the updated Practice Direction 2 and include:

- Party choice: Parties can opt in to the Fast Track when filing their claim form or the acknowledgment of service, with the other Party having the opportunity to contest the allocation.

- Flexible eligibility criteria: the amended PD 2 sets out detailed guidance on what cases might be suitable for the Fast Track, summarized below:

- A case may be suitable for the Fast Track where, in the opinion of the party proposing the Fast Track, the case will require: a hearing of two days or fewer; no expert evidence; two fact witnesses or fewer per party; limited disclosure; and limited, if any, interlocutory applications.

- A case that is suitable for the Fast Track may also have one or more of the following features (i) the case has a financial value of between US$ 100,000 and US$ 500,000, excluding interest; (ii) the case is straightforward, does not involve a substantial dispute of fact, and does not fall under the Small Claims, Employment or Real Property Divisions; (iii) and/or the case is urgent.

- A case is also likely to be suitable for the Fast Track where it is a liquidated debt claim; an arbitration claim; a claim for declaratory or other relief which is unlikely to involve a substantial dispute of fact; an application for contempt of court; an application for extension of period for delivery of a charge; or an application for a freezing injunction, search order or interim remedy.

- Certainty on timing: the Fast Track aims to resolve cases within six months of allocation, with specific timelines for filing pleadings, disclosure and witness statements.

- Case management: the Fast Track includes provisions for CMCs, progress monitoring and pre-trial reviews to ensure efficient case progression. It also introduces a directions questionnaire and proposed directions tailored to Fast Track claims.

- Document production: Parties must provide standard disclosure when filing their pleadings and parties may also seek specific disclosure. The procedure for the disclosure on the Fast Track dispenses with Redfern Schedules.

- Mediation continues to be strongly encouraged at all stages of the claim.

Comparison of the Rule 27 and Fast Track Procedures

The Fast Track will result in case management on a significantly faster timescale than the traditional Rule 27 procedure. The Fast Track also effectively replaces the streamlined Rule 30 procedure, which has been repealed as part of the reforms. Below, we compare the Fast Track Procedure against the Rule 27 procedure:

| Process | Rule 27 procedure | Fast Track procedure |

| ADR | ADR continues to be encouraged but not mandatory. | |

| Claim form issued | Claimant requests that the Court issues claim form. | Claimant opts into Fast Track in claim form. The Court confirms the allocation when issuing the claim form.

Parties must make standard disclosure when filing their pleadings. |

| AoS and ‘opt in’ to Fast Track | AoS must be filed within 14 days of service of claim form. | AoS must be filed within 7 days if the claim has been placed on the Fast Track.

Defendant may agree or object to proposed Fast Track allocation in its AoS (or propose the Fast Track if not already proposed by Claimant). If there is party disagreement on Fast Track, the Court will determine the correct allocation on the papers. |

| Defence and Counterclaim | Filed within 28 days of claim form. Extendable by agreement by up to 28 days, or further with the Court’s permission. | To be filed within 21 days of claim form (extendable only by up to 14 days).

Where the Court has reserved its decision on the allocation of the case to the Fast Track until after the defendant has answered the claim, the defendant must file and serve an answer to the claim within 28 days of being served with the claim form. |

| Reply and defence to Counterclaim | To be filed within 21 days of service of the defence. | To be filed within 14 days of service of the defence. |

| CMC | CMC convened within 14 days of close of pleadings. | CMC to be scheduled within 10 days of close of pleadings. |

| Trial timetable | Court sets trial timetable as soon as practicable after receiving the parties’ pre-trial checklist. | Fast Track claims will seek to be disposed of within 6 months from allocation of the case to the Fast Track. |

| Disclosure | Standard disclosure but with the ability to request Specific Disclosure. | Parties provide standard disclosure with their pleadings. Parties may make applications for specific disclosure. |

| Evidence | Evidence is served in accordance with timetable agreed in the CMC. Expert evidence with the permission of the Court. | Maximum 2 fact witnesses each, unless the Court directs otherwise.

No expert evidence, unless the Court directs otherwise. |

| Option to decide the claim on the papers | At the Court’s general discretion. | At the Court’s general discretion. |

| The Hearing | At the Court’s general discretion. | Fast Tracked trials should generally be no more than 2 hearing days. |

| Costs and Appeals | The usual rules on costs and appeals for cases in the Commercial and Civil Division apply. | |

.

Other Changes in the Commercial and Civil Division

The updated CPR and Practice Direction 2 also provide several other key changes for Court users. Key among these are the following:

- Removal of the Rule 30 procedure: the Rule 30 process has been removed. It is likely that any claim previously brought under the Rule 30 procedure can now be dealt with using the Fast Track process.

- Removal of page limits: while claim forms in the Commercial and Civil Division were previously limited to 50 pages, this requirement has been removed. This does not reflect an intention that claim forms be longer than 50 pages; however the Court will not prescribe strict limits.

- Extensions of time: the amendments provide greater certainty for parties when applying for an extension of time.

Commentary

The changes to the CPR and Practice Directions reflect the ADGM’s commitment to not only meet but surpass international best practices. They provide a robust and efficient legal framework for the resolution of disputes, particularly in the realm of real property and commercial claims, for the benefit of all Court users. The establishment of the Real Property Division under the new ADGM Court Rules is a significant step toward supporting Abu Dhabi’s growing real estate market and addressing end-user requirements, with the Fast Track offering a route for the quick resolution of claims, providing parties with certainty and a way to resolve disputes efficiently.

The Court has published Guidance Notes for the: (i) Fast Track; (ii) Real Property Division (other than Short-Term Residential Lease Claims); and (iii) Short-Term Residential Lease Claims. These Guidance Notes are on the Court’s website and can be accessed here.

[1] See primarily (i) Real Property Regulations 2024; (ii) Off-Plan Development Regulations 2024; (iii) Off-Plan and Real Property Professionals Regulations 2024; (iv) Off-Plan Development Regulations (Project Account) Rules 2024. Other disputes, claims and applications concerning real property (including commercial leases) are set out in the ADGM Courts, Civil Evidence, Judgments, Enforcement and Judicial Appointments Regulations 2015 as well as the Taking Control of Goods and Commercial Rent Arrears Recovery Rules 2015.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, the authors, or any of the following practice leaders and members of Gibson Dunn’s global Litigation, Transnational Litigation, or International Arbitration practice groups:

Nooree Moola – Dubai (+971 4 318 4643, nmoola@gibsondunn.com)

Lord Falconer – London (+44 20 7071 4270, cfalconer@gibsondunn.com)

Robert Spano – London/Paris (+33 1 56 43 13 00, rspano@gibsondunn.com)

© 2025 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP. All rights reserved. For contact and other information, please visit us at www.gibsondunn.com.

Attorney Advertising: These materials were prepared for general informational purposes only based on information available at the time of publication and are not intended as, do not constitute, and should not be relied upon as, legal advice or a legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances. Gibson Dunn (and its affiliates, attorneys, and employees) shall not have any liability in connection with any use of these materials. The sharing of these materials does not establish an attorney-client relationship with the recipient and should not be relied upon as an alternative for advice from qualified counsel. Please note that facts and circumstances may vary, and prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome.

This update provides a summary of the key features of the regime as currently set out in the Draft Regulations.

The Dubai International Financial Centre Authority (DIFCA) has published a draft of the Variable Capital Company Regulations (the Draft Regulations) for public consultation, proposing a novel corporate structure aimed at enhancing the DIFC’s attractiveness as a jurisdiction for structuring investment platforms, including for family offices, asset holding, and private investment purposes.

The new regime introduces the Variable Capital Company (VCC), which offers a flexible framework for segregating assets and liabilities through the creation of “Cells” within a single legal entity.

The consultation process remains ongoing, and the final form of the regulations may change depending on feedback received. This update provides a summary of the key features of the regime as currently set out in the Draft Regulations.

Background and Context

The DIFC currently offers a limited cell regime under its existing Protected Cell Company framework, which is available only to certain types of investment companies. However, this framework does not include features such as segregated cells (described below). The proposed VCC regime introduces a more versatile and commercially attractive vehicle, offering structuring options that go beyond what is currently available under the DIFC’s existing framework.

Similar vehicles are available in only a few other jurisdictions, such as Singapore and Mauritius, which have implemented their own VCC regimes in recent years. By introducing a comparable structure, the DIFC aims to enhance its competitiveness and appeal to global investors, family offices, and asset managers seeking flexible and cost-effective structuring options.

Overview of the VCC Structure

A VCC is a private company that may be established in the DIFC either with one or more Segregated Cells or Incorporated Cells (each, a Cell) but not both, which may hold assets and liabilities separately from those of the VCC and other Cells. A VCC may have any number of Segregated Cells or Incorporated Cells, or none, in each case as provided for in its Articles of Association. This allows for ring-fencing of liabilities and targeted investment structuring.

Notably:

- A Segregated Cell does not have separate legal personality but is treated as segregated for asset and liability purposes.

- An Incorporated Cell is itself a private company with separate legal personality but cannot own shares in other Cells or the VCC.

The VCC structure is modelled to appeal to family offices, private funds, and other investment vehicles seeking to consolidate multiple investments within a single corporate structure, while maintaining legal separation between them.

Qualifying Criteria

Applicants must satisfy one of the following conditions:

- The VCC will be controlled by GCC Persons, Registered Persons or Authorised Firms; or

- It is established, or continued in the DIFC for purposes of holding legal title to, or controlling, one or more GCC Registrable Assets;

- It is established for a Qualifying Purpose, defined to include Aviation Structures (persons having the sole purpose of facilitating the owning, financing, securing, leasing or operating an interest in aircrafts), Crowdfunding Structures (persons established for the purpose of holding the asset(s) invested through a crowdfunding platform), Intellectual Property Structures (persons established for the sole purpose of holding intellectual property for commercial purposes), Maritime Structures (persons having the sole purpose of facilitating the owning, financing, securing, chartering, managing or operating of an interest in maritime vessels or maritime units), Structured Financing (persons having the sole purpose of holding assets to leverage and/or manage risk in financial transactions), or Secondaries Structures (vehicles facilitating the transfer of investment assets to secondary investors); or

- It is established or continued in the DIFC has a Director that is an Employee of a Corporate Service Provider and that Corporate Service Provider has an arrangement with the DIFC Registrar pursuant to the relevant provisions in the Draft Regulations.

Key Features

1. Regulatory Oversight

- VCCs are subject to the DIFC Companies Law and other Relevant Laws, unless otherwise provided.

- The DFSA must authorise any VCC providing financial services.

- The license of the VCC established for a Qualifying Purpose shall be restricted to the activities specific to the Qualifying Purpose stated in its application to incorporate or continue in the VCC in the DIFC, or any other permitted purpose shall be restricted to the activity of Holding Company. A VCC shall not be permitted to employ any employees.

2. Share Capital and Distributions

- VCCs may issue and redeem shares based on the net asset of the company or individual Cells.

- Cellular distributions must relate solely to the assets and liabilities of the relevant Cell, and must not impact other Cells or the VCC’s general assets.

3. Asset Segregation and Liability Protection

- Officers may incur personal liability if they breach their duties regarding segregation and disclosure of cell identity in transactions.

- The regulations include detailed provisions governing the consequences of unlawful inter-Cell transfers and creditor protections.

- Each transaction with third parties must clearly specify the relevant Cell and limit recourse accordingly.

4. Conversions, Mergers, and Transfers

The framework allows for:

- Conversion of existing DIFC companies into VCCs and vice-versa;

- Transfer of incorporated cells between VCCs, subject to Registrar approval and creditor protection mechanisms;

- Merger or consolidation of Segregated Cells, with prior written notice and creditor opt-out rights.

5. Licensing and Naming

- VCCs must end their names with “VCC Limited” or “VCC Ltd.”

- Segregated Cells and Incorporated Cells must have unique identifiers (e.g., “VCC SC” or “VCC IC”).

- Licences are limited to the specific activities of the Qualifying Purpose, though VCCs controlled by Qualifying Applicants may be licensed for broader purposes.

6. Shareholder Transparency and AML Compliance

- VCCs must maintain separate registers of shareholders for each Cell.

- Ultimate beneficial ownership disclosure obligations apply in line with DIFC UBO Regulations.

7. Fees and Incorporation Process

The proposed incorporation and licensing fees are aligned with the DIFC’s broader cost-efficient regime:

- USD 100 for incorporation;

- USD 1,000 for an annual licence;

- USD 300 for lodging a Confirmation Statement.

Key Topics

Some of the key topics included in the consultation paper include questions around:

- the scope and breadth of the proposed qualifying-requirements test, including whether proprietary investment access is too wide or too narrow;

- appropriateness of allowing both Segregated Cells and Incorporated Cells within a single regime, and the implications of prohibiting a VCC from having both types concurrently; and

- adequacy of creditor-protection measures, notice, publication and court-application rights on conversion of a VCC into a standard DIFC company and vice versa.

Practical Implications

The proposed introduction of the VCC regime provides a robust framework for private clients and investment entities to achieve structural and operational flexibility within a regulated DIFC environment. Key advantages include:

- Legal segregation of assets/liabilities for risk mitigation.

- Simplified investment platform management.

- Suitability for private wealth structuring, crowdfunding, and secondary market transactions.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these issues. For additional information about how we may assist you, please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, any leader or member of the firm’s Mergers & Acquisitions or Private Equity practice groups, or the authors:

Andrew Steele – Abu Dhabi (+971 2 234 2621, asteele@gibsondunn.com)

Omar Morsy – Dubai (+971 4 318 4608, omorsy@gibsondunn.com)

© 2025 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP. All rights reserved. For contact and other information, please visit us at www.gibsondunn.com.

Attorney Advertising: These materials were prepared for general informational purposes only based on information available at the time of publication and are not intended as, do not constitute, and should not be relied upon as, legal advice or a legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances. Gibson Dunn (and its affiliates, attorneys, and employees) shall not have any liability in connection with any use of these materials. The sharing of these materials does not establish an attorney-client relationship with the recipient and should not be relied upon as an alternative for advice from qualified counsel. Please note that facts and circumstances may vary, and prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome.

The Civil Transactions Law codifies the rules governing liquidated damages clauses under Saudi law. This client alert outlines key considerations for contracting parties when adopting such clauses, and how courts may approach them in practice.

How Liquidated Damages Clauses are Recognized in Saudi Arabia

The Saudi legal framework recognizes liquidated damages as pre-agreed estimates of losses incurred by one party due to the other party’s breach of contract, including non-performance or delay in fulfilling contractual obligations.

Historical Context

Even prior to the Civil Transactions Law, Saudi courts recognized liquidated damages clauses based on Sharia principles. Such clauses have been upheld as valid and enforceable, except in cases where:

- the breaching party had a legitimate excuse for non-performance or delay; or

- the agreed amount was deemed excessively high, amounting to financial coercion, in which cases courts have assessed excessiveness based on prevailing customs and practices.[1]

How Liquidated Damages Operate Today

- Validity:Parties can agree on liquidated damages, either in the original contract or a later agreement.[2]

- Simplified Burden of Proof:Liquidated damages clauses render the occurrence of damages presumed. To enforce such a clause, the aggrieved party is not required to prove damage or causation – merely that a breach has occurred.[3]

- Avoiding Liquidated Damages:A party may avoid liability under a liquidated damages clause by proving either:

- that the other party did not suffer any damage;[4] or

- that the damage was not caused by the party’s breach, but rather by the other party’s acts, omissions, or a force majeure event.

- Reducing Liquidated Damages:The breaching party may be successful in reducing the sum of liquidated damages by proving either:

- that the pre-agreed amount is grossly exaggerated, thereby allowing the court to rule in accordance with the general principles of liability under Saudi law;[5] or

- that the breaching party has partially performed their obligations, thereby allowing the court to assess the extent of unperformed obligations and apply the liquidated damages clause accordingly.[6]

- Court Discretion:Courts cannot freely adjust liquidated damages clauses. Their discretion is limited to:

- reducing the amount in cases of gross exaggeration or partial performance. A mere discrepancy between the damages incurred and the agreed sum is insufficient to warrant reduction[7]; or

- increasing the sum if the non-breaching party proves that deceit or gross negligence by the debtor caused the damage to exceed the agreed sum.[8]

- Prohibition on Payment Obligations:In line with Saudi Arabia’s strict prohibition of interest payments[9], it is impermissible as a matter of public policy for liquidated damages to apply to payment obligations.[10]

- How Saudi Arabia Compares to Neighboring Jurisdictions:Saudi Arabia’s approach towards liquidated damages clauses shares similarities with the approaches of UAE and Egypt, but there are some differences. For example:

| Element | Saudi Arabi | UAE | Egypt |

| Default position on prior notice of imposition | No prior notice required.[11] | Prior notice required.[12] | Prior notice required.[13] |

| Court discretion to adjust liquidated damages | Relatively limited.[14] | Relatively broad.[15] | Relatively limited.[16] |

Points to Consider When Drafting a Liquidated Damages Clause

- Be specific. Clearly define what triggers the liquidated damages (delays, quality issues, etc.).

- Consider industry benchmarks. Base estimates on market standards or historical data to avoid claims of exaggeration.

- Expressly address partial performance. Specify how damages will be calculated if some of the triggering obligations are met.

- Follow notice requirements. While Saudi law does not by default require notice to enforce liquidated damages, your specific contract might.

- Understand burden of proof requirements. Know who bears the burden of proof in different scenarios to claim or defend tactically.

- Consider all available remedies and seek them tactically. Parties may be precluded from enforcing liquidated damages clauses in conjunction with other contractual remedies.

[1] Resolution No. 25 dated 31/08/1394H by the Council of Senior Scholars: “The Council unanimously decides that the penalty clause stipulated in contracts is valid and legally binding, and must be upheld unless there is a legitimate excuse for the breach of the obligation that justifies it under Sharia. In such a case, the excuse nullifies the obligation until it ceases. If the penalty clause is, by customary standards, excessive to the extent that it serves as a financial threat and deviates significantly from the principles of Sharia, then fairness and equity must prevail, based on the actual loss of benefit or incurred harm.” Cases in which Saudi courts upheld the Council of Senior Scholar’s Resolution No. 25 include the General Court’s Decision No. 1 of 1439H: “The liquidated damages clause included in contracts is a valid and enforceable condition which must be upheld, unless there is a legitimate excuse for breaching the obligation that is recognized under Shari’a, in which case the excuse suspends the obligation until it ceases. If the amount of liquidated damages is excessive by customary standards, to the point that it constitutes financial coercion and departs from the principles of Shari’a, then recourse must be had to justice and fairness, based on the actual harm incurred or the benefit lost. The determination of such matters in case of dispute is to be made by the competent court with the assistance of experts and professionals.”

[2] Civil Transactions Law, Article 178: “The contracting parties may specify in advance the amount of compensation whether in the contract or in a subsequent agreement, unless the subject of the obligation is a cash amount. The right to compensation shall not require notification.”

[3] For example: Board of Grievance’s decision in Case No. 20 of 1430H (predating the enactment of the Civil Transactions Law): “…and the administrative authority is not required to prove that it has suffered harm, given that [the liquidated damages] constitute an agreed-upon compensation for presumed harm, including harm resulting merely from delay.” Commercial Court in Riyadh’s decision in Case No. 4530906759 of 1445H: “The Law expressly provides that liquidated damages are not due to the creditor if the debtor proves that the creditor has suffered no harm. This is specifically stated in paragraph (1) of Article (179) of the same Law mentioned above,” presuming that liquidated damages are initially owed to the creditor upon breach, and it is the debtor’s burden to rebut this presumption by proving the absence of harm. This position is consistent with the literature of leading scholars in the region. For example, A. Sanhouri, ‘Al Waseet on the Explanation of the Civil Code’, Part Two, p. 817, concerning a similarly formulated legal provision in Egypt’s Civil Code: “[…] the presence of a Liquidated Damages Clause renders the occurrence of damage presumed, and the creditor would not be required to prove it. Therefore, if the debtor alleges that the creditor has not incurred damage, it is he who would bear the burden of proof, and not the creditor.”

[4] Civil Transactions Law, Article 179: “Compensation that is contractually agreed upon by the parties shall not be payable if the debtor proves that the creditor has sustained no harm.”

[5] Civil Transactions Law, Article 179(2): “The court may, upon a petition by the debtor, reduce the compensation if the debtor establishes that the agreed-upon compensation was excessive or that the original obligation was partially performed.” A. Almarjah, ‘Explanation of the Saudi Civil Transactions law,’ 1445H, Part One, p. 297: “Judicial intervention is limited to removing exaggeration in the liquidated damages clause, not to assessing its proportionality to the actual harm. Accordingly, if the agreed liquidated damages exceed the actual harm, but the excess is not deemed gross, the judge may not reduce the amount.”

[6] Civil Transactions Law, Article 179(2): “The court may, upon a petition by the debtor, reduce the compensation if the debtor establishes that the agreed-upon compensation was excessive or that the original obligation was partially performed.”

[7] A. Sultan, ‘A Brief on the General Theory of Obligation’, 1983, Section 2, p. 78, concerning a similarly formulated legal provision in Egypt’s Civil Code: “…if there is excess in the quantification, but it is not exaggerated, it is impermissible to reduce it, as the fundamental principle is that the Judge orders in accordance with what has been agreed-upon by the parties, and absent one of the conditions of the exception, it is obligatory to resort to the fundamental principle.” A similar opinion has been given by a Saudi scholar; A. Almarjah, ‘Explanation of the Saudi Civil Transactions law,’ 1445H, Part One, p. 297: “Judicial intervention is limited to removing exaggeration in the liquidated damages clause, not to assessing its proportionality to the actual harm. Accordingly, if the agreed liquidated damages exceed the actual harm, but the excess is not deemed gross, the judge may not reduce the amount.”

[8] Civil Transactions Law, Article 179(3): “The court may, upon a petition by the creditor, increase the amount of compensation to the extent necessary to cover the harm if the creditor establishes that an act of fraud or gross negligence by the debtor is what caused the harm to exceed the agreed-upon compensation.”

[9] Commercial Court in Jeddah, Case No. 4531041638 of 1445H: “…it is impermissible to agree on compensation where the subject of the obligation is a monetary amount. Given that this Article pertains to public order (public policy), the parties may not contract out of or override its provisions…”

[10] See, Resolution No. (109) (12/3) of the International Islamic Fiqh Academy: “It is permissible to stipulate a penalty clause in all financial contracts, except in contracts where the primary obligation is a debt, as this would constitute explicit riba (usury),” upheld by the Commercial Court in Jeddah in Case No. 433665897 of 1443H.

[11] Civil Transactions Law, Article 178: “The contracting parties may specify in advance the amount of compensation […] The right to compensation shall not require notification.”

[12] UAE’s Civil Transactions Law, Article 387: “Compensation is not due without the debtor being notified, unless otherwise provided by law or agreed upon in the contract.”

[13] Egypt’s Civil Code, Article 218: “Unless otherwise specified, compensation is not due without the debtor being notified.”

[14] Civil Transactions Law, Article 179(2): “The court may, upon a petition by the debtor, reduce the compensation if the debtor establishes that the agreed-upon compensation was excessive or that the original obligation was partially performed.” Id, Article 179(3): “The court may, upon a petition by the creditor, increase the amount of compensation to the extent necessary to cover the harm if the creditor establishes that an act of fraud or gross negligence by the debtor is what caused the harm to exceed the agreed-upon compensation.”

[15] There are some inconsistent court decisions noted across and within each of the jurisdictions. UAE’s Civil Transactions Law, Article 390(2): “The judge may, in all cases, at the request of one of the parties, amend such an agreement, in order to make the amount assessed equal to the damage. Any agreement to the contrary is void.”

[16] Egypt’s Civil Code, Article 224: “(1) Damages fixed by agreement are not due, if the debtor establishes that the creditor has not suffered any loss. (2) The judge may reduce the amount of these damages, if the debtor establishes that the amount fixed was grossly exaggerated or that the principal obligation has been partially performed. (3) Any agreement contrary to the provisions of the two preceding paragraphs is void.”

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these issues. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, any member of the firm’s International Arbitration, Judgment and Arbitral Award Enforcement, or practice groups, or the following authors in Riyadh:

Mahmoud Abdel-Baky (+966 55 056 6323, mabdel-baky@gibsondunn.com)

Rashed Z. Khalifah (+966 55 236 0511, rkhalifah@gibsondunn.com)

*Hamzeh Zu’bi is a trainee associate in Riyadh and not admitted to practice law.

© 2025 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP. All rights reserved. For contact and other information, please visit us at www.gibsondunn.com.

Attorney Advertising: These materials were prepared for general informational purposes only based on information available at the time of publication and are not intended as, do not constitute, and should not be relied upon as, legal advice or a legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances. Gibson Dunn (and its affiliates, attorneys, and employees) shall not have any liability in connection with any use of these materials. The sharing of these materials does not establish an attorney-client relationship with the recipient and should not be relied upon as an alternative for advice from qualified counsel. Please note that facts and circumstances may vary, and prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome.

In a transformative step to enhance and better protect its business environment, Saudi Arabia has enacted a new Trade Name Law, which was published in the Official Gazette (Um AlQura) on October 4, 2024, and has come into effect on April 3, 2025.

Introduction

The law came into effect on April 3, 2025, replacing the previous legislation that had been in force since November 23, 1999. The implementing regulations were published on March 30, 2025, and took effect concurrently with the new law.

This law reform marks yet another significant step in the modernization of Saudi’s legal framework, streamlining processes and fostering a transparent, efficient business landscape. Below, we outline the key features of the new law and its practical implications in Saudi Arabia.

Key Features of the New Trade Name Law

1. Simplified Trade Name Selection

The updated Trade Name Law offers businesses greater flexibility in reserving and registering trade names. Trade names can be reserved for an initial period of 60 days, with the possibility of extending for an additional 60 days. Further extensions may be granted but are subject to specific registration circumstances. Given the exclusivity associated with registered/reserved trade names, there is a greater practical need to register desired trade names ahead of time. If the reservation period expires and the procedures for the issuance of a commercial register certificate are not complete, the reservation will lapse, and the trade name will become available for reservation by any person. All reservations and extensions will be subject to payment of fees.

2. Linguistic Flexibility

The old trade names regime was renowned for its strict restrictions on the use of foreign trade names with only a few exceptions being permitted for certain foreign companies or as determined on a case-by-case basis by the Minister of Commerce. The new Trade Name Law ushers in a new era as trade names can now be registered in Arabic, transliterated Arabic (i.e., Arabic words or text that have been written using the Latin (Roman) alphabet instead of the Arabic script), English, or combinations of letters and numbers (with a maximum of 9 digits).

It is recommended that all businesses ensure linguistic consistency in branding to maximize recognition. Foreign investors will need to ensure that the foreign trade name is writable in English and is capable of being translated into Arabic.

3. Independent Trade Name Ownership

Trade names are capable of being owned, sold, or assigned to other persons, which enhances their commercial value. Given that trade names are exclusive and cannot be replicated, registering and owning a trade name provides businesses with a potentially valuable asset.

What Else Has Changed? A Deeper Look at the New Trade Name Law

Trade Name Registration Process

Article 5 of the new law provides a clearer process regarding the trade name application process, including clearer decision-making timelines of up to 10 days from the date of submission of the application, compared to the old timeline which took up to 30 days (see Article 7 of the old regulation). The decision timeline is extendable in certain cases to 30 days when external approval of a trade name is required.

The Ministry of Commerce has integrated the trade name reservation service into the Saudi Business Center portal, which now manages all trade name applications. After a trade name application is accepted, publication is now mandatory, with applicants bearing associated costs.

Priority is given to the first applicant i.e. first in time to submit an application, if multiple applications for the same name exist. If the registrar rejects an application, applicants will have 60 days to appeal to the Ministry.

Trade Name Protection Against Unauthorized Use

The new law, under its Article 6, strengthens protection against unauthorized use such that no person is entitled to use a trade name registered that belongs to someone else. A fine of SAR 10,000 is now imposed as per Article 15 of the implementing regulations to strengthen adherence to the law and limit unauthorized use of registered or reserved trade names. Businesses with registered names in the Commercial Register have the right to seek compensation for damages caused by unauthorized use. This means that the commercial register serves as proof of ownership, and any person who makes any unauthorized use of a registered trade name will have committed a violation and may be liable to pay compensation to the registered owner of the trade name.

Prohibited Trade Names

Article 7 of the new law outlines the following prohibitions:

- Trade names must not violate public order or morality.

- Names that are misleading, deceptive, or resemble an already registered trade name (regardless of activity type) are not allowed.

- Names similar to famous trademarks are restricted unless owned by the applicant.

- Names containing political, military, or religious references are prohibited.

- Trade names must not resemble symbols of local, regional, or international organizations.

The Ministry of Commerce will also maintain and update a public list of prohibited names regularly, for transparency. Some of the prohibitions introduced by the Trade Names Law are quite broad in nature (particularly the prohibitions relating to “public order or morality” and “famous trademarks”).

It remains unclear how broadly these prohibitions will be interpreted and applied by the Registrar, and the practical challenges such prohibitions may create for applicants wishing to register their trade names. It also remains to be seen whether other restrictions will be unilaterally imposed by the Ministry by way of practice or by way of circumstance and how far the Ministry may go in enforcing these restrictions. To date, the Ministry has already started to reject applications containing the word “company” or that otherwise include a description of an ordinary business activity such as “regional headquarter”.

Monetary Fees for Name Reservations

Article 14 of the implementing regulation introduces the following new fee structure for trade name reservations:

- SAR 200 for an Arabic trade name.

- SAR 500 for an English trade name.

- SAR 100 to extend reservation duration.

- SAR 100 to dispose of the trade name.

New Guidelines for Trade Names Similarity Criteria

Article 5 of the implementing regulation stipulates a formal set of criteria and guidelines that will be used to determine whether a trade name is deemed too similar to an existing one, reducing ambiguity. Under these guidelines, a trade name will be considered like another if its written form closely resembles that of a registered, famous, or reserved trade name. This includes:

- Identical spelling with different word arrangements.

- Identical spelling with a one-letter difference.

- Identical spelling with minor changes, such as adding, removing, or altering pronouns, definite articles, pluralization, or diminutives.

- Identical pronunciation despite differences in spelling or numbers replacing letters, and vice versa.

Criteria mentioned above shall apply to English trade names and their corresponding wording with the use of Arabic letters.

Use of ‘Saudi’ or names of Saudi Cities and Regions in Trade Names

As per Article 4 of the implementing regulation, businesses can now reserve names containing ‘Saudi’ or the name of a Saudi city or region, subject to the following conditions:

- The name must not be identical or similar to any governmental entity.

- The main component or essential element of the name must not be ‘Saudi’ or a Saudi city or region.

- The name must not be used in a manner that would cause harm to the reputation of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

- For both Makkah and Madinah regions, approval from the Royal Commission for Makkah and the Holy Sites or the Madinah Development Authority is required.

Practical Considerations for Businesses

Saudi Arabia’s new Trade Name Law enhances transparency, secures commercial identities, and increases business interests in Saudi. In line with this, businesses should consider the following:

- Ensure Distinctiveness: With stricter rules on name similarity and given the relative ease of reserving/registering a trade name, applicants should conduct comprehensive trade name searches and check the Ministry’s prohibited names list before applying to avoid getting rejected.

- Understand New Protections: Trade names are now valuable commercial assets—businesses should actively monitor for unauthorized use and take prompt legal action if necessary.

- Consider Linguistic Strategy: With increased linguistic flexibility, businesses can choose names that enhance global branding while remaining compliant with local regulations.

For Tailored Legal Guidance

For expert legal advice on trade name registration and compliance, contact our team below.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist with any questions you may have regarding these developments. To learn more, please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, or the authors in Riyadh:

Mohamed A. Hasan (+966 55 867 5974, malhasan@gibsondunn.com)

Hadeel Tayeb (+966 53 944 3329, htayeb@gibsondunn.com)

© 2025 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP. All rights reserved. For contact and other information, please visit us at www.gibsondunn.com.

Attorney Advertising: These materials were prepared for general informational purposes only based on information available at the time of publication and are not intended as, do not constitute, and should not be relied upon as, legal advice or a legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances. Gibson Dunn (and its affiliates, attorneys, and employees) shall not have any liability in connection with any use of these materials. The sharing of these materials does not establish an attorney-client relationship with the recipient and should not be relied upon as an alternative for advice from qualified counsel. Please note that facts and circumstances may vary, and prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome.

The new Rules come into effect from 3 April 2025.

Background:

On 21 February 2025, the Minister of Commerce officially decreed and published into law the Ultimate Beneficial Ownership Rules (UBO Rules). In line with steps taken by other financial centers and leading jurisdictions around the world, the UBO Rules require all companies in KSA, other than companies publicly listed in KSA, to disclose and maintain accurate information about their ultimate beneficial owners. The UBO Rules come into effect from 3 April 2025.

How does the UBO Rules define an Ultimate Beneficial Owner?

- The UBO Rules define an “ultimate beneficial owner” as any natural person who meets the following criteria:

- owns at least 25% of the company’s share capital whether directly or indirectly;

- controls at least 25% o the voting shares in the company, whether directly or indirectly;

- is entitled to appoint or remove a majority of the company’s board of directors, its manager or president, whether directly or indirectly;

- ability to influence decision-making or the business of the company whether directly or indirectly; or

- is a representative of any legal person to which any of above criteria applies.

- The UBO Rules clarify that if an ultimate beneficial owner cannot be identified by applying the foregoing criteria, then the company’s manager or members of its board of directors or its president will be regarded as its ultimate beneficial owner.

Key obligations under the UBO Rules:

Some of the key obligations under the UBO Rules include the following:

- Incorporation: The Ministry of Commerce will now require applicants to disclose information on their ultimate beneficial owners as part of the application process for incorporation of companies in KSA.

- Annual Filings: In relation to those companies already established at the time the UBO Rules come into effect, such companies will be required to make annual filings disclosing their ultimate beneficial owners. Such filings are due on the anniversary of the date on which companies were registered with the Ministry’s commercial register.

- Maintenance & Updates: All existing companies will be required to maintain an ultimate beneficial owner register and notify the Ministry of any changes in the identity of an ultimate beneficial owner.

- Required Information: It remains unclear what information will be requested by the Ministry to validate the identity of an ultimate beneficial owner in a relevant KSA company. Unsurprisingly, the UBO Rules grant the Ministry with broad authority to require disclosure. The UBO Rules state that the Ministry will publish guidelines with respect to its procedures and requirements for the identification of ultimate beneficial owners.

Exemption from UBO Rules:

The following entities are exempted from the application of the UBO Rules:

- Companies wholly owned by the state or any state-owned authorities whether directly or indirectly; and

- Companies undergoing insolvency proceedings in accordance with the Bankruptcy Law.

Additionally, the Minister of Commerce may issue exemptions on a case-by-case basis. All companies exempted from the UBO Rules are nevertheless required to prove to the Ministry that they enjoy such an exempted status.

Penalties for Non-Compliance:

A person that is required to comply with the UBO Rules but fails to do so, including its obligations to disclose/update information to the Ministry with respect to ultimate beneficial ownership, may face a fine of SAR 500,000.

Investors with complex shareholding structures in KSA should be wary of these UBO Rules as indirect changes in their shareholding structures could trigger disclosure obligations with the Ministry in KSA. All investors in KSA must start thinking about introducing appropriate internal protocols to ensure full compliance with the UBO Rules.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist with any questions you may have regarding these developments. To learn more, please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, or the authors in Riyadh:

Mohamed A. Hasan (+966 55 867 5974, malhasan@gibsondunn.com)

Lojain AlMouallimi (+966 11 827 4046, lalmouallimi@gibsondunn.com)

© 2025 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP. All rights reserved. For contact and other information, please visit us at www.gibsondunn.com.

Attorney Advertising: These materials were prepared for general informational purposes only based on information available at the time of publication and are not intended as, do not constitute, and should not be relied upon as, legal advice or a legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances. Gibson Dunn (and its affiliates, attorneys, and employees) shall not have any liability in connection with any use of these materials. The sharing of these materials does not establish an attorney-client relationship with the recipient and should not be relied upon as an alternative for advice from qualified counsel. Please note that facts and circumstances may vary, and prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome.

This update explores how the concept of loss of profit in contractual liability has evolved in light of the enactment the Saudi Civil Transactions Law.

Recent developments, including the enactment of the Civil Transactions Law,[1] have clarified certain aspects of recoverable damages in contractual liability, particularly regarding the permissibility of loss of profit claims under Saudi law. This article explores how the concept of loss of profit in contractual liability has evolved in light of the enactment of the Civil Transactions Law.

A. Historical Stance on Loss of Profit Claims

Previously, Saudi courts generally excluded the recovery of loss of profits in breach of contract claims. This was based on the prevailing Islamic Shari’a principle that compensation must be certain, rather than speculative. Courts viewed claims for lost profits as speculative, and thus were routinely rejected.[2] However, there have been some court decisions that granted loss of profit claims, although these were exceptional and not part of a consistent judicial trend.[3]

While these outlier court decisions did not clearly articulate a consistent standard for when loss of profits can be compensated, they referred to Islamic Shari’a principles that suggest loss of profits may be compensated where the loss is ‘certain.’ Article 5 of Resolution No. 109/3/12 of the International Islamic Fiqh Academy asserts that “…the damages that may be compensated include actual financial damages, true losses, and certain loss of profit.” The key element here is the element of “certainty.” Although the courts have not articulated a clear threshold for certainty in these decisions, they implied that the loss of profit must be capable of being verified to avoid speculation.

B. Interpretation of Loss of Profit Claims Under the Civil Transactions Law

In June 2023, the Civil Transactions Law was promulgated by Royal Decree No. 191/D, dated 29/11/1444H. The enactment of the Civil Transactions Law has clarified the legal treatment of loss of profit claims, expressly permitting them.

However, the Civil Transactions Law does not provide specific criteria or standards for assessing such claims. This gave rise to uncertainty regarding how Saudi courts will approach claims for lost profits in breach of contract claims under the Civil Transactions Law. Therefore, claims for lost profits will most likely be assessed according to the general rules of contractual liability under the Civil Transactions Law. These include:

- Contractual liability must be established: All elements of contractual liability, namely breach, damages, and causation, must be proven by the claimant.[4] Saudi courts have upheld this rule in multiple judgments, ensuring that a breach of contract claim is only successful when all three elements are satisfactorily established.[5]

- Quantum must be proven: Establishing the occurrence of loss in not enough. The claimant must also prove quantum. In straightforward cases, such as those involving documentary evidence like invoices, proving the quantum of damages can be a relatively simple process. However, in more complex cases, expert evidence is typically required to establish the quantum of damages. This has been the standard practice in Saudi courts.

- Recoverable losses must be typically foreseeable: If compensation is not specified in the contract, the court will determine it. If the obligation arises from the contract and there is no fraud or gross negligence, damages are limited to those damages that are foreseeable at the time of the contract.[6]

- The loss must be a natural consequence of the breach: As a general rule, recoverable damages include moral and material damages naturally arising from the breach, including loss of profit. The Civil Transactions Law uses an objective standard to determine this. Damages are considered a natural consequence if the aggrieved party could not have avoided them by exercising reasonable care.[7]

- The award must not enrich the creditor: The goal of awarding damages in breach of contract cases is to restore the non-defaulting party to the position they would have occupied if the contract had been properly performed. In other words, compensation is intended to “fully cover the loss” and restore the aggrieved party to their original position – or to the position they would have been in – had the loss not occurred.[8]

It is noteworthy that Article 1 of the Civil Transactions Law mandates that, in the absence of specific legal provisions, the courts must apply Islamic Shari’a principles that are consistent with the general provisions of the Civil Transactions Law. This means that, despite the Civil Transactions Law’s explicit allowance for loss of profit claims, the courts may still turn to Shari’a principles requiring certainty in such claims.

C. Conclusion

The treatment of loss of profit claims in Saudi Arabia has evolved with the introduction of the Civil Transactions Law, representing a significant shift in the legal landscape. While Saudi law now permits the recovery of lost profits, the courts have yet to establish clear guidelines on how such claims will be assessed. In the absence of detailed court decisions, the general rules of contractual liability will be controlling, and the courts may rely on Islamic Shari’a principles and the requirement for certainty in determining whether loss of profit claims are compensable. As the legal framework continues to develop, a clearer standard for these claims is likely to emerge.

[1] The Civil Transactions Law, promulgated by Royal Decree No. 191/D, dated 29/11/1444H.

[2] This position was upheld in multiple cases. See, for example, the Commercial Court of Appeal in Riyadh’s Decision No. 4655 of 1442H and the Court of Appeal in Mecca’s Decision No. 430329136 of 1443H.

[3] Court of Appeal of Board of Grievances’ Decision No. 2454 of 1437 and Jeddah Commercial Court of First Instance’s Decision No. 2393 of 1437H are examples of cases in which courts allowed claims for lost profits, citing Islamic Shari’a authorities that permit such claims if the loss is “certain.”

[4] Article 2(1) of the Evidence Law, promulgated by Royal Decree No. D/43, dated 25/5/1443: ((A claimant shall have the burden of proof and a defendant shall have the burden of defense.))

[5] For instance, the Commercial Court of Appeal in Riyadh’s Decision No. 4530050546 of 1445H: ((…if the three elements are satisfied, the claimant would be entitled to fair compensation for all damages; if one of those elements is not satisfied, the entitlement to compensation would terminate completely.))

[6] Article 180 of the Civil Transactions Law: ((If the amount of compensation is not specified in a contract or a legal provision, it shall be determined by the court in accordance with the provisions of Articles 136, 137, 138, and 139 of this Law. However, if the obligation arises from the contract, the debtor who has not committed any act of fraud or gross negligence shall be liable only for compensating harm that could have been anticipated at the time of contracting.))

[7] Article 137 of the Civil Transactions Law: ((The harm for which a person is liable for compensation shall be determined according to the aggrieved party’s loss, whether the loss is incurred or in the form of lost profits, if such loss is a natural result of the harmful act. Such loss shall be deemed a natural result of the harmful act if the aggrieved party is unable to avoid such harm by exercising the level of care a reasonable person would exercise under similar circumstances.))

[8] Article 136 of the Civil Transactions Law: ((Compensation shall fully cover the harm; it shall restore the aggrieved party to his original position or the position he would have been in had the harm not occurred.))

© 2024 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP. All rights reserved. For contact and other information, please visit us at www.gibsondunn.com.

Attorney Advertising: These materials were prepared for general informational purposes only based on information available at the time of publication and are not intended as, do not constitute, and should not be relied upon as, legal advice or a legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances. Gibson Dunn (and its affiliates, attorneys, and employees) shall not have any liability in connection with any use of these materials. The sharing of these materials does not establish an attorney-client relationship with the recipient and should not be relied upon as an alternative for advice from qualified counsel. Please note that facts and circumstances may vary, and prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome.

The Court’s decision also distinguishes the ADGM and DIFC’s approaches to English law.

A unique feature of the ADGM—certainly within the region—is that the English common law, as it stands from time to time, not only applies and has legal force in the jurisdiction, but also forms part of the ADGM’s laws. This is enshrined in Article 1(1) of the Application of English Law Regulations 2015 (“Regulations”).

On 17 November 2023, the ADGM Court of Appeal published an important decision in AC Network Holding Ltd. v. Polymath Ekar SPV1, confirming, among other things, that whilst ADGM judges “are not sitting as English law judges”, “they are bound to apply the rule laid down by the [Regulations]”. Lord Hope contrasted this with the position in the Dubai International Financial Center (“DIFC”): “The position in the Dubai International Financial Centre is different. Common law rules in various areas have been codified, and it is only if those rules or the laws of other relevant legal systems do not provide an answer that the laws of England and Wales are applied.”

This decision provides clarity to parties contracted to resolve disputes before the ADGM courts, and emphasises the unique position of English law in the ADGM, which the Court of Appeal observed “lies at the heart of the system of law that was created for the ADGM”.

Context and Factual Background

With the adoption of the Regulations in 2015, the ADGM opted to fully transplant English law as its applicable private law.[1] The result is that the entire, constantly updated, corpus of English common law applies in the ADGM. However, as the AC case demonstrates, there remained some doubts as to the full effect of this legal transplant.

AC concerned the sale of shares in a car-sharing company operating in Dubai, Abu Dhabi and Saudi Arabia. In 2020, the company’s minority shareholders were compelled, pursuant to a “Drag Along Notice” (“Notice”) issued by the majority shareholders, to sell their shareholding to a third party.

The minority shareholders challenged the validity of the Notice on the ground that the third party purchaser was not a ‘bona fide purchaser’ as required by the Shareholders’ Agreement (“Agreement”). Rather, they claimed that the purchaser was actually the majority shareholder himself, merely acting through a corporate veil. The minority shareholders sued the majority for the economic torts of intentionally procuring a breach of the Agreement as well as of conspiracy to use unlawful means to breach the Agreement. The Agreement was governed by English Law and any disputes arising under the Agreement were subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the ADGM courts.

Court of First Instance

The ADGM Court of First Instance agreed with the minority shareholders that the Notice was invalid, insofar as the majority shareholder, by standing on “both sides of the fence,” had effectively expropriated the company’s shares in bad faith. However, the Court did not find that this breach was intentional, with the majority shareholder having received assurance from its legal counsel that the transfer was lawful.[2] In considering the unlawful means conspiracy claim, the Court was faced with a question of English law: did this claim also require knowledge of the unlawfulness of the conduct?