July 8, 2015

2015 came in like a lion, bringing with it remarkable policy changes regarding corporate non-prosecution agreements (“NPA”) and deferred prosecution agreements (“DPA”). The Department of Justice’s (“DOJ”) leadership has articulated new bright-line approaches to post-resolution conduct, including the unprecedented step of revoking an NPA. The judiciary has edged further toward a more interventionist role in DPA oversight. Finally, as we previously predicted, the first of dozens of anticipated NPA resolutions have emerged from the DOJ Tax Division’s August 2013 “Program for Non-Prosecution Agreements or Non-Target Letters for Swiss Banks” (the “DOJ Tax Swiss Bank Program”).

This client alert, the fourteenth in our series of biannual updates on NPAs and DPAs (available here), (1) summarizes highlights from the NPAs and DPAs of the first half of 2015; (2) addresses shifts in the treatment of NPAs and DPAs by all three branches of government; (3) spotlights trends in the arena of trade sanctions; (4) touches upon DOJ’s revocation of an NPA and its extension of another in the course of investigating several major global financial institutions; (5) overviews the DOJ Tax Swiss Bank Program and the NPAs emerging from it; (6) discusses recent developments regarding the level of confidentiality afforded NPAs and DPAs and the work product flowing from them; and (7) provides an update on recent international developments regarding NPAs and DPAs. As in previous updates in this series, the appendix lists all agreements announced to date in 2015.

NPAs and DPAs in 2015

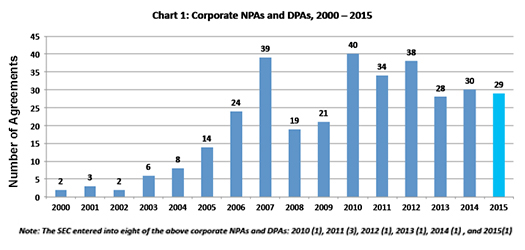

In the first six months of 2015, DOJ entered into five DPAs and 23 NPAs. In addition to DOJ’s 28 agreements, the SEC entered into one DPA in the first part of 2015, bringing its total overall NPA and DPA count to eight. This year’s 29 year-to-date overall agreements vastly exceeds agreement counts from recent years, with 2014 seeing 13, and 2013 seeing 12 by this time in the year. Indeed, 2015’s NPA and DPA count has already exceeded the overall number of NPAs and DPAs in 2013, when there were only 28, and it is closely approaching last year’s overall count of 30. This is in large part due to the rollout of NPA resolutions under the DOJ Tax Swiss Bank Program, discussed at length below, which account for 15 of the 29.

As demonstrated by Chart 1 below, NPAs and DPAs have played an increasingly important and consistent role in resolving allegations of corporate wrongdoing since 2000. There have typically been at least 20 agreements per year since 2006, with highs reached in 2007 and 2010 at 39 and 40 agreements, respectively. This year, with 29 agreements already on the books and the promise of dozens more through the DOJ Tax Swiss Bank Program, it is highly likely that 2015 will substantially exceed historical highs. Indeed, in 2007, at this point in the year, only 17 agreements had been publicized; in 2010, there had been only 11.

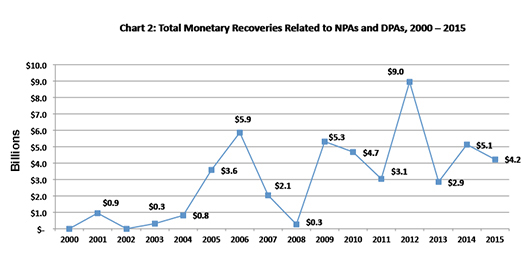

Chart 2 below illustrates the total monetary recoveries related to NPAs and DPAs from 2000 through the present. At over $4.2 billion, this year’s agreements–as in 2014–have already exceeded the overall recovery value for 2013, which was approximately $2.9 billion. This is due in large part to a single DOJ DPA with Deutsche Bank AG, which involved a recovery of $2.369 billion, and several other settlements in the millions and hundreds of millions. Of course, these figures do not include the $2.520 billion recovered this year by DOJ through plea agreements with four international banks in connection with alleged foreign exchange rate manipulation.

Although–as discussed below–the tone at DOJ has shifted in recent months with respect to NPAs and DPAs, these figures leave no doubt that NPAs and DPAs continue to be important resolution tools. Indeed, these negotiated agreements have touched some of today’s largest and most successful corporations, either through parent companies or their subsidiaries. Due to the sheer size and complexity of these organizations, NPAs and DPAs are crucial in allowing companies that are otherwise good corporate citizens to continue to do business while implementing the significant reforms, reporting, and ongoing cooperation that these agreements typically require.

Shifts in NPA and DPA Treatment by the Executive, Congress, and the Judiciary

Over the past several months, the use of NPAs and DPAs in concluding corporate regulatory investigations has received heightened scrutiny and attention in all levels of government. The intensified scrutiny of these agreements has sparked a larger debate about not only the appropriate use of such enforcement tools by regulators, but also the political and policy motivations underlying the increased criticism coming from politicians.

Recent Enforcement Official Statements Regarding NPAs and DPAs

The enforcement and rehabilitative efficacy of NPAs and DPAs continues to be touted by officials closest to corporate enforcement actions. As Assistant Attorney General Leslie Caldwell recently explained, through these agreements, “in cases against companies, we are frequently able to accomplish as much as, and sometimes even more than, we could from even a criminal conviction.”[1] Indeed, an NPA or DPA with a corporation enables enforcement authorities to continue to impact and monitor a company’s compliance program and culture long after settlement. Enforcement advantages posed by these agreements include the imposition of remedial measures and improved compliance policies and practices, securing assistance from a corporation in ongoing investigations, as well as the use of monitors and/or periodic reporting to help ensure a corporation continues to abide by the terms of the agreement.[2]

Even while acknowledging the force of NPAs and DPAs in holding corporations accountable and altering their future behavior, DOJ has also tempered its conviction favoring their use. As stated in a recent speech by Assistant Attorney General Caldwell:

When we suspect or find non-compliance with the terms of DPAs and NPAs, we have other tools at our disposal, too. We can extend the term of the agreements and the term of any monitors, while we investigate allegations of a breach, including allegations of new criminal conduct. Where a breach has occurred, we can impose an additional monetary penalty or additional compliance or remedial measures.[3]

Perhaps most significantly, she indicated that “the Criminal Division will not hesitate to tear up a DPA or NPA and file criminal charges, where such action is appropriate and proportional to the breach.”[4] As discussed in greater detail below, this message was punctuated by the revocation of an NPA earlier this year. Whether this revocation represents an anomaly or will lead to further such terminations among still-outstanding NPAs and DPAs is a question that remains to be answered. Importantly, however, DOJ’s signaling of its intention to terminate prior agreements where subsequent misconduct occurs, should–at the very least–caution current NPA- and DPA-holders. Shifting the paradigm to revoking agreements fails to recognize that global companies with tens of thousands of employees cannot practically have every employee on lockdown.

NPAs and DPAs and Congress

The most outspoken congressional voice scrutinizing NPAs and DPAs as tools for the resolution of enforcement actions has been Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts. In an April 15, 2015, policy speech, Senator Warren slammed NPAs and DPAs as so-called “get-out-of-jail-free cards.”[5] The thrust of her argument is that because NPAs and DPAs are tethered to paying a fine–rather than being held accountable in court–the agreements undercut any meaningful deterrence against future misconduct that otherwise would have been achieved by going to trial.[6] With her specific targeting of recidivists, some have noted that–in the lead-up to the 2016 presidential election–“[Senator Warren’s] timing suggests a renewed effort to pull Democrats to the left on Wall Street reform as the party waits to see what position Hillary Clinton will take on the matter.” [7]

Whether the underlying motivation for this position is election-centered, policy-driven, or both, Senator Warren has argued that–at a minimum–a company that already has an existing agreement should not be offered a new one for new misconduct.[8] As she argues, by merely paying a financial penalty, corporations can repeatedly skirt the criminal justice system and other deterrent factors that would be available through the trial and conviction process.[9] The underlying assumption of this reasoning, however, is that monetary fines are the primary–and perhaps only–deterrent factor of NPAs and DPAs, which is completely wide of the mark.

Gibson Dunn, as a principal architect and counsel for many corporations negotiating NPAs and DPAs, fundamentally disagrees with Senator Warren’s mistaken surface treatment of these critical tools for corporate reform.[10] Indeed, fines are typically only one of many requirements imposed by NPAs and DPAs, not least of which are the establishment of rigorous compliance program reforms and tighter accounting and internal control measures, the appointment of third-party monitors to oversee company operations, required self-investigation and reporting, and continuing investigation support.[11] Some agreements even contain provisions that go so far as to alter corporate board composition and bar participation in certain markets.[12] To suggest that such far-ranging and lingering measures are inherently easier for organizations to weather than a guilty plea misapprehends how corporations function. But more importantly, this mindset confuses corporations, juridical persons only, with real persons who can be punished in the same manner as an individual. Overly harsh penalties against the corporate entity will merely incentivize its best professionals to jump ship, while innocent shareholders and local communities are left holding the bag as the company is destroyed or permanently crippled.

We also take issue with Senator Warren’s suggestion that prosecutors are “timid” in the face of large corporations and unwilling to prosecute.[13] To the contrary, in our experience, DOJ and the SEC have been nothing but zealous in their investigation and advocacy. What Senator Warren forgets is that due process and the presumption of innocence must rule the day: rather than practice pitchfork justice, the men and women of DOJ and the SEC must use all tools available to calibrate resolutions to corporate missteps, and prosecute only when the evidence, and the violation, so require.

It is with caution that we await further developments in this arena. We believe that NPAs and DPAs serve as valuable tools for the government to address misconduct in a nuanced manner, and for corporate entities to calibrate their compliance programs to avoid future violations. The monetary penalties, remedial actions, cooperation with the government, and compliance program enhancements that attend most of these agreements (and often are part of an iterative settlement process) place both enforcement authorities and corporate entities in positions that achieve both accountability for past transgressions and deterrence for potential future ones.

Update on Judicial Oversight of Deferred Prosecution Agreements

In our 2014 Year-End Update, we discussed the growing trend of federal judges actively exploring different legal bases for evaluating the substance of DPAs and approving or rejecting them based on their merits. Although traditionally courts have not actively scrutinized the terms of these agreements, a growing chorus of judges has voiced concern about performing such a limited function with respect to DPAs, which have become one of the more prominent tools for policing corporate misconduct. Furthermore, while typically courts have held in abeyance any term-by-term examination of these agreements, there are indications that judges may seek to assert a greater role in overseeing the implementation of DPAs as well.

Two decisions in particular from 2015 encapsulate this trend: United States v. Fokker Services and United States v. HSBC Bank. In United States v. Fokker Services, Judge Richard Leon of the District Court for the District of Columbia rejected Fokker Services B.V.’s (“FSBV”) DPA with the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Columbia, based on his inherent powers “to supervise the administration of criminal justice among the parties before the bar.”[14] In United States v. HSBC Bank, although Judge John Gleeson of the Eastern District of New York (“EDNY”) ultimately approved a DPA between HSBC and the U.S. Attorney’s Office for EDNY for alleged violations of anti-money laundering and sanctions laws and regulations, he has continued to exercise close supervision of HSBC’s compliance with the terms of that agreement. Each of these cases is discussed in turn below.

Fokker Services

A proposed DPA and information were first filed in the FSBV matter in early June 2014, upon which Judge Leon requested supplemental briefing from the government in support of the DPA.[15] Following briefing on the threshold question of whether Judge Leon had the authority to approve or reject the DPA on its merits, Judge Leon issued an opinion rejecting the DPA on February 5, 2015. On the question of the standard of review, he noted that upon filing the DPA in the district court, the parties also filed a motion to exclude the term of the agreement from the deadline for trial under the Speedy Trial Act. The Speedy Trial Act typically requires that trials begin within 70 days of the filing of the information or indictment, or of the defendant’s first appearance, but it excludes certain periods of delay, including “any period of delay during which prosecution is deferred by the attorney for the Government pursuant to written agreement with the defendant, with the approval of the court, for the purpose of allowing the defendant to demonstrate his good conduct.”[16] The statute calls for some form of judicial approval, and both DOJ and FSBV argued that this approval is limited to a requirement that the judge approve a proffered DPA unless there is an indication that (a) the defendant did not enter into the agreement willingly, or (b) the only purpose of the agreement is to circumvent Speedy Trial Act limits.[17]

Drawing on Judge Gleeson’s original decision in United States v. HSBC in 2013, however, Judge Leon stated that the court has the authority “to approve or reject a DPA pursuant to its supervisory power.”[18] And while noting that a court’s supervisory powers should be used “sparingly,” [19] Judge Leon determined not to approve the DPA.[20] Both parties have appealed Judge Leon’s ruling to the D.C. Circuit and oral argument is scheduled for September 11, 2015.[21]

United States v. HSBC

As detailed above, Judge John Gleeson laid the groundwork for Judge Leon’s Fokker Services decision in his opinion approving HSBC’s DPA in 2013. Drawing on the same legal theories that would later inspire Judge Leon in Fokker Services, Judge Gleeson held that it “was easy to imagine circumstances in which a deferred prosecution agreement, or the implementation of such an agreement, so transgresses the bounds of lawfulness or propriety as to warrant judicial intervention to protect the integrity of the Court.” [22] As such, while he approved HSBC’s DPA, he indicated that his approval was “subject to a continued monitoring of its execution and implementation.” [23] He concluded by saying that the supervisory powers furnished a basis for the court to ensure that the implementation remains within the bounds of lawfulness, after which he directed the parties to file quarterly reports with the court on the progress of implementation.[24]

Recent events suggest that Judge Gleeson may continue to exercise supervisory authority with respect to the implementation of the DPA. On April 1, 2015, in compliance with the court’s order, the U.S. Attorney’s Office for EDNY submitted a quarterly progress report that summarized the much longer First Annual Follow-Up Review written by HSBC’s appointed compliance monitor.[25] In response, Judge Gleeson issued a minute order on April 28, 2015, directing the government to file with the court the complete “First Annual Follow-Up Review.” The government complied with that request, and preliminarily filed the monitor’s full report under seal and filed a motion on June 1, 2015, for it to be permanently sealed. (The continuing confidentiality of sealed reports will be discussed in greater depth below.) To date, Judge Gleeson has not made any statements on the record regarding the monitor’s report or the government’s summary. Historically, the government, as part of its exercise of prosecutorial discretion, retains the exclusive right to determine whether a defendant has complied with the terms of the DPA or if it has materially breached the agreement, warranting voiding the DPA and prosecuting the defendant.[26] Judge Gleeson’s opinion approving the DPA may suggest that he envisions the court playing some role in monitoring the implementation process.[27]

Spotlight on Trade Sanctions

The past decade has demonstrated a marked increase in the number of NPAs and DPAs in connection with alleged violations of trade sanctions. The first agreement related to trade sanctions was issued in 2007, when ITT Corporation entered into a DPA with DOJ to resolve charges of export controls violations. Since then, the government has entered into 18 agreements relating to trade sanctions, export controls, and the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (“IEEPA”). Most of these DPAs and NPAs date from the past five years: prior to 2010, the government had entered into only three such agreements; since 2010, the government has signed 15. Today, 5% of all DPAs/NPAs relate to trade sanctions, the IEEPA, or export violations.

The Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (“OFAC”), which administers the relevant standards and statutes, issued Economic Sanctions Enforcement Guidelines, effective November 2009, listing a number of aggravating and mitigating factors with respect to whether action is taken against an offending entity and what kind of action is taken. This, and recent agreements resolving trade sanctions violations, highlight the most common factors.[28]

Aggravating factors include:

(1) Willful or reckless conduct;

(2) Knowledge by senior executives or senior management;

(3) A long-term pattern of conduct;

(4) Harm to a U.S. sanctions program;

(5) A deficient compliance program;

(6) The sophistication of the company; and

(7) Lack of internal controls.

Although not delineated in the OFAC Economic Sanctions and Enforcement Guidelines, any impact to national security also appears to be an aggravating factor. DOJ’s settlement in March 2015 with Commerzbank AG (“Commerzbank”), for example, highlighted the government’s focus on the issue of national security. Under this DPA, Commerzbank agreed to pay $642 million as part of a settlement involving alleged violations of the IEEPA and the Bank Secrecy Act.[32] In announcing the settlement, U.S. Attorney Ronald C. Machen, Jr. stressed the importance of sanctions laws “to protect the national security of the United States and promote our foreign policy interests.” [33] We anticipate that this will continue to be a factor in future trade sanctions cases.

Government authorities have also noted several mitigating factors that could benefit companies resolving allegations of trade sanctions violations, including:

(1) No OFAC actions in the previous five years;

(2) Remedial steps taken toward future compliance;

(3) New or improved internal controls;

(4) Conducting an internal investigation;

(5) Cooperation with OFAC during its investigation; and

(6) Agreeing to toll the statute of limitations on prosecution.[34]

The 2013 DPA between Weatherford International Limited (“Weatherford”) and DOJ, and the 2013 DPA between Dal-Tech Devices, Inc. (“Dal-Tech”) and DOJ, exemplify these factors. Weatherford signed “the largest ever settlement outside of the banking industry for apparent violations of U.S. sanctions on Iran, Sudan, and Cuba.” [35] Despite the magnitude of Weatherford’s settlement, government authorities indicated that “Weatherford’s extensive remediation and its efforts to improve its compliance functions are positive signs,” and detailed in Weatherford’s DPA the many efforts that Weatherford had made to cooperate.[36] Similarly, the 2013 Dal-Tech DPA explicitly sets out relevant mitigating factors. OFAC stated that Dal-Tech’s penalty reflects an analysis of the totality of the circumstances, including the fact that “Dal-Tech has not been the subject of any prior OFAC enforcement action” and the company’s agreement to “implement a compliance program that includes sanctions and export compliance training of all employees.” [37]

Recent NPA Revocation and Financial Institution Settlements

In our 2014 Year-End Update, we reported that DOJ had extended the term lengths of three NPAs and DPAs–with Barclays Bank Plc. (“Barclays”), UBS AG (“UBS”) and Standard Chartered Bank–while DOJ pursued investigations into conduct potentially implicating those agreements. Since then, the extensions for Barclays and UBS have resolved in what has been described as “truly historic” interactions between the U.S. government and these major financial institutions, among others, regarding charges relating to the potential manipulation of multiple foreign exchange (“FX”) markets.[38]

More specifically, DOJ was one of more than 30 antitrust, regulatory, and other law enforcement authorities across several continents that launched investigations into the FX trading activities of several of the world’s largest banks, including Barclays, UBS, Citigroup Inc. (“Citigroup”), J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. (“J.P. Morgan”), Royal Bank of Scotland Group Plc (“RBS”), HSBC Holdings Plc (“HSBC”), and Bank of America Corporation (“Bank of America”). These global investigations focused on allegations that banks manipulated the prices of currencies exchanged in the FX spot market. Both the Barclays and UBS NPAs, which related to DOJ’s prior investigation into the London interbank offered rate (“LIBOR”) market, were extended during the pendency of DOJ’s FX investigations.

As the FX investigations drew closer to resolution, DOJ increasingly emphasized the potential consequences associated with violating the terms of an NPA or DPA. In March 2015, Assistant Attorney General Leslie Caldwell stated that “[w]e don’t want DPAs and NPAs to be perceived as a cost of doing business.” [39] She explained that, “[j]ust as an individual on probation faces a range of potential consequences for a violation of probation, so too does a bank or (other) financial institution that breaches a deferred prosecution agreement or a non-prosecution agreement.” [40] To the extent that DOJ’s investigations implicated potential breaches of Barclays’s and UBS’s agreements, both of which related to conduct regarding manipulation of the LIBOR interest rates, these banks were therefore at risk of those agreements’ revocation.

In May 2015, DOJ announced a coordinated resolution of FX- and LIBOR-related allegations with five banks. As part of this resolution, Barclays, Citigroup, J.P. Morgan, and RBS agreed to plead guilty to antitrust violations relating to alleged FX rate manipulation, and to pay fines collectively totaling over $2.5 billion.[41] Barclays further agreed that its trading practices had violated its 2012 NPA–which was still open as a result of the extension–and consequently paid an additional $60 million penalty for LIBOR-related violations.

UBS was not charged by DOJ in connection with the FX investigation. Even so, DOJ took the unprecedented step of revoking the 2012 NPA it had signed with UBS relating to the alleged manipulation of LIBOR and other benchmark interest rates.[42] DOJ’s May 2015 announcement included a statement that UBS’s NPA had been withdrawn, representing “the first time in recent history that the Department of Justice has found that a company breached an NPA over the objection of the company.” [43] DOJ has entered into 337 corporate NPAs and DPAs since 2000, and this is only the second time in that period that an NPA or DPA has been terminated due to alleged post-agreement criminal conduct. UBS ultimately pled guilty to the conduct the NPA had otherwise immunized from prosecution.[44]

DOJ Tax Swiss Bank Program

On August 29, 2013, DOJ and the Swiss Federal Department of Finance issued a joint statement announcing the Program for Non-Prosecution Agreements or Non-Target Letters for Swiss Banks. Through this program, Swiss banks could secure non-target letters or NPAs from DOJ in exchange for cooperation with DOJ and disclosure of information regarding “U.S. Related Accounts” and their account holders and beneficiaries.[45]

Under the DOJ Tax Swiss Bank Program, a “Category 2” bank is one that has self-identified as having “reason to believe it may have committed tax-related offenses . . . or monetary transactions offenses . . . in connection with undeclared U.S. Related Accounts held by the Swiss Bank” between August 1, 2008, and December 31, 2014 (or the execution of a Foreign Financial Institution Agreement, if later). The DOJ Swiss Bank Tax Program includes burdensome and detailed due diligence requirements for identifying “U.S. Related Accounts” that are borrowed from an agreement between the U.S. and Switzerland for cooperation to facilitate the implementation of the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act.[46] In particular, the DOJ Tax Swiss Bank Program required participating Swiss banks to search–either electronically, through paper files, or both–for any of the following indicia of a U.S. relationship:

(1) a U.S. citizen or resident account holder;

(2) unambiguous identification of a U.S. place of birth;

(3) a current U.S. mailing or residence address (including U.S. post office box or “in-care-of” addresses);

(4) a current U.S. telephone number;

(5) standing instructions to transfer funds to an account maintained in the United States;

(6) a currently effective power of attorney or signatory authority granted to a person with a U.S. address; or

(7) an “in-care-of” or “hold mail” address that was the sole address the Swiss bank had on file for the account holder.[47]

Upon identifying all “U.S. Related Accounts,” participating Category 2 banks were required to disclose certain information regarding their business models and generic information regarding those U.S. Related Accounts to DOJ.[48] Upon execution of an NPA, the DOJ Tax Swiss Bank Program required additional detailed disclosures regarding U.S. Related Accounts closed by December 31, 2014 (or the execution of a Foreign Financial Institution Agreement, whichever is later), including each account’s maximum value, the number of U.S. persons or entities affiliated with each account, whether each account was held in the name of an individual or entity, whether each account held U.S. securities, the names and functions of certain persons affiliated with the accounts, and detailed information regarding transfers to and from the accounts.[49] Further, in part because Swiss banking secrecy laws prevented DOJ from accessing Swiss bank account data and verifying or investigating the results reported, this procedure of identifying and reporting U.S. Related Accounts had to be overseen and verified by an Independent Examiner.[50]

Finally, participating Category 2 banks were required to calculate steep penalties associated with those U.S. Related Accounts that were not tax compliant or provably on the path to tax compliance (as, for example, through disclosure to the Internal Revenue Service through a voluntary disclosure program) by the time of execution of an NPA.[51] These penalties ranged from 20% to 50% of the maximum aggregate value of all non-exempt U.S. Related Accounts opened during specific periods of time, with greater penalties associated with accounts opened later during the relevant period.[52]

Initially, 106 Swiss banks entered into the DOJ Tax Swiss Bank Program as Category 2 banks.[53] Today, as Swiss banks conduct due diligence and internal investigations to better assess their positions, at least 10, and likely more, have withdrawn from the DOJ Tax Swiss Bank Program. As of July 8, 2015, 15 Swiss banks have entered into NPAs with DOJ, with penalties ranging from only $9,090 to $211 million. Each NPA to date carries with it, in addition to a penalty, a term of four years and substantial continuing cooperation requirements. Table 2 below provides an overview of DOJ Tax Swiss Bank Program NPAs released to date. The total recovery associated with these NPAs is $268,170,090.

| Table 2: DOJ Tax Swiss Bank Program Banks with Announced NPAs |

|||

|

# |

Bank |

Date |

Penalty |

| 1. | Banca Credinvest SA | 6/3/2015 | $3,022,000 |

| 2. | Berner Kantonalbank AG | 6/9/2015 | $4,619,000 |

| 3. | Bank Linth Zurich AG | 6/19/2015 | $4,150,000 |

| 4. | Bank Sparhafen Zurich AG | 6/19/2015 | $1,810,000 |

| 5. | BSI SA | 3/25/2015 | $211,000,000 |

| 6. | Ersparniskasse Schaffhausen AG | 6/26/2015 | $2,066,000 |

| 7. | Finter Bank AG | 5/15/2015 | $5,414,000 |

| 8. | LBBW (Schweiz) AG | 5/28/2015 | $34,000 |

| 9. | MediBank AG | 5/28/2015 | $826,000 |

| 10. | Privatbank Von Graffenried AG | 7/2/2015 | $287,000 |

| 11. | Rothschild Bank AG | 6/3/2015 | $11,510,000 |

| 12. | Scobag Privatbank AG | 5/28/2015 | $9,090 |

| 13. | Société Générale Private Banking (Lugano-Svizzera) SA | 5/28/2015 | $1,363,000 |

| 14. | Société Générale Private Banking (Suisse) SA | 6/9/2015 | $17,807,000 |

| 15. | Vadian Bank AG | 5/5/2015 | $4,253,000 |

| TOTAL RECOVERY TO DATE | $268,170,090 | ||

We expect a glut of additional NPAs in the coming months as DOJ concludes negotiations with the remaining dozens of Swiss Banks that declared their intent to participate under the DOJ Tax Swiss Bank Program as Category 2 banks. Acting Assistant Attorney General of the DOJ Tax Division, Caroline Ciraolo, indicated in April 2015 that DOJ anticipates that agreements will be reached with the remaining banks by the end of 2015.[54] We will also continue to watch closely as DOJ resolves its ongoing investigations into approximately 12 additional Swiss banks–so-called “Category 1” banks–that were under investigation when the DOJ Tax Swiss Bank Program was announced, and were therefore ineligible to participate. One such bank–Julius Baer Group AG–announced on June 23, 2015, that its negotiations with DOJ were “now sufficiently advanced” to enable a preliminary financial assessment, and that it would book a reserve of $350 million in anticipation of settlement against its half-year earnings.[55] Another, Credit Suisse Group AG, settled similar allegations last year through a guilty plea and the payment of $2.6 billion.[56]

Confidentiality and NPAs/DPAs

DPAs and NPAs have also begun raising novel issues of confidentiality in a variety of different contexts. Two developments in particular will be analyzed below. The first is the ongoing effort of corporate defendants and prosecutors alike to ensure that the work product generated by independent compliance monitors appointed pursuant to an NPA or DPAs is kept confidential. Two cases in particular–100Reporters LLC v. DOJ and United States v. HSBC–have placed this issue into sharp focus. The second development that has arisen is the extent to which corporate defendants that have entered into NPAs and DPAs with U.S. authorities may be required to divulge certain confidential aspects of those agreements in litigation in foreign courts, an issue which the Royal Bank of Scotland has recently confronted in a lawsuit in the United Kingdom.

Update on Independent Monitor Work Product Confidentiality

In our 2014 Year-End Update, we discussed the prevalent practice of appointing monitors as a condition of NPAs and DPAs to assess the progress of corporate defendants in addressing their compliance deficiencies. More specifically, we focused on the important role that the confidentiality surrounding the monitor’s work product plays in allowing corporations to make their most confidential and commercially sensitive information available to the monitor so that he or she can comprehend the “full scope of the corporation’s misconduct” and take the steps “necessary to reduce the risk of” its recurrence.[57] Despite the important role that confidentiality plays, we noted that a recent FOIA suit seeking records from the Siemens monitorship–100Reporters LLC v. DOJ–placed this critical element of monitorships in doubt. Since the time of that update, the issue of monitor work product confidentiality has also arisen in United States v. HSBC, in which the government has complied with the court’s request to submit the monitor’s “First Annual Follow-Up Review,” but has sought to keep the entirety of the report under seal. Gibson Dunn served as counsel to the monitor in the Siemens monitorship and several of our partners have served as monitors or independent examiners; we take very seriously these challenges to monitor confidentiality, which threaten to weaken the important role that monitors can play in post-resolution corporate reform.

In United States v. HSBC, the government and HSBC have also had to address the issue of potential public access to monitorship documents, albeit in a slightly different context. As indicated above, Judge Gleeson required the government to submit the monitor’s “First Annual Follow-Up Review,” said to be more than 1,000 pages, instead of a brief summary of this report.[58] Once a document is filed in federal court, however, it is placed on the court’s electronic docket and can typically be viewed, downloaded, and disseminated at will. In HSBC, both parties recognized the severe risk of putting a monitorship report, containing significant quantities of sensitive and confidential information, on the court’s electronic docket. Consequently, the government and HSBC have filed separate motions to place the report under seal permanently, to be reviewed by the court only in camera.

As the government articulated in its motion, placing documents under seal can in some circumstances raise two issues with respect to access to information. First, “[t]he public has a ‘general right to inspect and copy public records and documents, including judicial records and documents.'”[59] Second, “under the First Amendment, the public has a ‘qualified . . . right to attend judicial proceedings and to access certain judicial documents.'”[60] At least in the Second Circuit, both the common law right and qualified First Amendment right have their own unique tests, though both, at their core, involve determining whether there is a right to the information and, if so, then assessing whether there are countervailing factors that outweigh that right.

In the HSBC case, the government stated that neither public right to disclosure was actually implicated by the sealing in this case. The government first rejected the notion that there was any qualified First Amendment right to the documents. It asserted that materials relied upon by prosecutors to determine whether the defendant is complying with a DPA have never been publicly accessible, and thus neither experience nor logic would favor their disclosure.[61] The government pointed out that there was no attendant public proceeding to which the documents are related; any decision on charging is “necessarily cloaked in secrecy.” [62]

The government then addressed whether there could be a common law right to access the information, arguing that the monitorship report was not a “judicial document” as it did not aid in the performance of a judicial function. Furthermore, even if the monitor’s reports were found to be judicial documents, both the government and HSBC concluded that the weight of any presumption in favor of access to them would be very low, and would be overcome by strong countervailing factors.[63] Specifically, the government stated that if the report were made public: (1) the ability of the monitor and the government to assess HSBC’s compliance with the DPA would be negatively impacted; (2) the capacity of HSBC’s regulators, such as the Federal Reserve and the United Kingdom’s Financial Conduct Authority (“FCA”), to effectively supervise would be compromised; (3) criminals seeking to exploit weaknesses in HSBC’s internal controls would be given a roadmap on how to do so; and (4) the ability of monitors and enforcement authorities to carry out their respective functions in future cases would suffer. The government stated that, if the monitorship report were publicly disclosed in this case, foreign regulators may presume that the monitor’s work product in other cases could be disseminated as well, making it less likely that foreign regulators would cooperate and thereby undermining the utility of monitorships in general.[64]

Given Gibson Dunn’s substantial experience with monitorships, we emphatically believe that HSBC’s and the government’s position is the only workable analysis for successful monitorships. To hold otherwise would completely chill the relationship between the monitor and the company and thereby eviscerate the goal of the monitorship. The issues raised by the government and HSBC demonstrate how central confidentiality is to the functioning of monitorships. Without the presumption that the work product of a monitor will remain confidential, a monitor may find it challenging to elicit the cooperation he or she requires to understand the extent of any deficiencies and the effectiveness of the remedial actions taken to address them.

The Impact of Foreign Litigation on Confidentiality

As Royal Bank of Scotland (“RBS”) has recently discovered, NPAs and DPAs can also be threatened by litigation overseas. On February 5, 2013, RBS entered into a DPA with DOJ regarding alleged attempts by its traders to manipulate LIBOR for certain currencies for the benefit of their trading positions.[65] The DPA Statement of Facts discusses the conduct of RBS employees with respect to LIBOR for only two currencies: the Japanese Yen and the Swiss Franc. In a footnote, however, the DPA further provides that the agreement is intended to cover submissions concerning additional currencies identified in a confidential Attachment C.[66] Because of ongoing investigation by DOJ into the potential manipulation of LIBOR for these currencies, Attachment C was expressly intended to be held in confidence and not disclosed by the parties to the agreement.[67] During a hearing on the matter in United States District Court for the District of Connecticut, Judge Michael Shea indicated that “the parties have provided me with a copy of Attachment C, which I have received, reviewed and which I will maintain in my custody, under seal, pending resolution of this matter.” [68]

Approximately one year later, a UK property developer named Property Alliance Group Limited (“PAG”) sued RBS over four interest swap transactions it entered into with the bank from 2004 to 2008 that used the three-month LIBOR for the British Pound.[69] In deciding the scope of RBS’s disclosure under UK discovery rules, Justice Colin Birss held that information relating to all LIBOR currencies, and Attachment C by extension, should be disclosed.[70] RBS objected to inspection by PAG of a number of documents related to the LIBOR investigation, including Attachment C to the DPA, asserting that if it were to turn over the document it would be held in criminal contempt of Judge Shea’s “order.” [71] According to Justice Birss, however, “the fact that a party objects to disclosure or inspection on the ground that to comply with such an order would put the party at risk of prosecution under a foreign law provides no defence to the making of the order.” [72] At the same time, Justice Birss recognized that, in deciding whether to order a party to disclose confidential information, the court has discretion to take into account the risk of prosecution.[73] Here, RBS argued that, although Judge Shea did not draft a formal order regarding the sealing of Attachment C, his statements at the hearing were sufficiently clear that, if RBS were to disclose the document, it could be held in criminal contempt.[74] After soliciting input from experts on U.S. law with opposing views, Justice Birss rejected this argument and ordered inspection upon finding that it was not clear that ordering RBS to produce its own copy of Attachment C–as opposed to the copy on the court record–would actually violate the order.[75] The court also concluded that, even if disclosure amounted to breach, it was not apparent that the breach could be considered willful because RBS had consistently objected to disclosing Attachment C.[76] Notwithstanding this analysis, Justice Birss provided RBS with four weeks to produce the document for inspection, allowing RBS time to seek approval from Judge Shea.[77] RBS did file a motion for clarification of the court’s order regarding Attachment C, and on March 10, 2015, Judge Shea ordered that RBS would not be held in violation of his order “if it complies with the English Court Order, or other order from a court of competent jurisdiction specifically requiring RBS or its affiliates to produce or provide inspection of Attachment C.”[78]

While this case involved an exercise of discretion that was dependent on the specific facts before the judge, it has broader implications for companies contemplating entering into NPAs and DPAs. Both PAG and Justice Birss concluded that the fact that the document was confidential was not in and of itself sufficient to prevent Attachment C from being inspected.[79] Justice Birss acknowledged judges may be inclined to draft orders to safeguard the confidentiality of certain documents, e.g., to prevent them from being read in open court, but he held that such orders would not necessarily block the disclosure of the information from one party to its adversary.[80] As a consequence, plaintiffs in foreign courts may seek, and in some circumstances succeed in obtaining, confidential information surrounding a company’s recent DPA or NPA, potentially including monitorship reports and other sensitive materials, in an effort to bolster their claims in follow-on civil litigation.

International Updates from the United Kingdom and France

Update from the United Kingdom

As discussed in our 2013 Mid-Year Update, our 2014 Mid-Year Update and our 2014 Year-End Update, the United Kingdom’s corporate DPA regime, effective February 24, 2014, allows the use of DPAs by UK prosecutors, who are guided by a Deferred Prosecution Agreement Code of Practice issued by the Serious Fraud Office (“SFO”) and the Crown Prosecution Service. The UK DPA regime differs from the approach taken in the United States in a number of key respects, including that DPAs are not a generally available tool to prosecutors, but rather are only available in connection with certain specifically enumerated offences. Unlike in the United States, the procedure for the conclusion of a DPA also involves very extensive involvement of the Crown Court.

As in the United States, the right to initiate any DPA negotiations lies squarely with the prosecutors.[81] In addition, to enter into a DPA, it appears that the SFO may expect companies to forego certain of the protections potentially available to them through conducting legally privileged internal investigative actions. SFO Director David Green QC (channeling an iconic electioneering slogan of former Prime Minister Tony Blair’s on education) has stated that a company’s candidacy for a DPA will depend on three things: “cooperation, cooperation and cooperation.”[82]

Director Green also appears to see DPAs as just one part of a wider prosecutorial arsenal that the SFO would like to amass. He has observed that companies will more readily consider entering into DPAs if faced with the credible threat of successful prosecution, and expressed support for the creation of a new corporate offense, “failure to prevent economic crime,” along the lines of the offense under Section 7 of the UK Bribery Act.[83] He has also encouraged a reconsideration of the rules on establishing corporate criminal liability, with a view to making it easier for the UK authorities to prosecute companies.

DPAs have been available to UK prosecutors for 16 months, but no instances of the UK prosecutors’ use of this tool have yet become public, despite several instances of criminal charges within the scope of the their use. This may, however, be about to change. On May 20, 2015, in a speech to the Global Anti-Corruption and Compliance in Mining Conference 2015, Ben Morgan, Joint Head of Bribery and Corruption at the SFO, issued a stern warning to companies that seek to cooperate with the authorities in a less than fulsome way, creating what he described as the mere “impression of cooperation.”[84] He exhorted companies to seek “a different relationship” with the SFO, with a view to seeking to take advantage of the “degree of control and certainty largely absent from traditional prosecution” offered by a DPA.[85] He went on to give the first public indication that the SFO has begun to make use of the DPA regime, and has issued the first invitations to companies under investigation to participate in DPA negotiations:

We have issued our first invitation letters giving corporates the opportunity to enter into DPA negotiations. Where we are now is working with corporates on how best to go through that process – not “why DPA,” but “how DPA.” And when it comes to “how,” the DPA Code is clear; we and the court need you to cooperate fully with our investigation. . . . [W]here suspicions of corrupt activity arise, we do not require you to carry out internal investigations; investigation is our job. . . . Our stance is to ask for genuine cooperation. . . . We expect you to engage with us early, and to work with us as we investigate, not to rush ahead and, whether intentionally or not, complicate the work we need to do. This is, we appreciate, to some extent a departure from the way things used to be and the way certain practices have built up in other jurisdictions. . . . Our job is to investigate possible criminal offences and we take a very dim view of anything anyone does that makes that job more difficult than it needs to be.[86]

It is clear, then, that the SFO will be using the DPA regime to reward corporate behavior that it considers desirable, and to disincentivize certain behaviors that it considers unhelpful. If and when any elements of UK DPA negotiations come into the public domain, it will be interesting to see what level of cooperation the SFO has sought in practice before making a DPA offer, and in particular, at what stage of any internal investigations the companies in question began to engage with the SFO.

It is also clear that the SFO’s emerging practice on DPAs will be under intense scrutiny. In a joint letter of June 19, 2015, to SFO Director Green, three leading anti-corruption NGOs–Transparency International UK, Corruption Watch, and Global Witness–encouraged the SFO to seek to tie into the DPA process a number of elements that appear to go well beyond the requirements of the UK legislative regime on DPAs.[87]

The letter, which the NGOs explicitly state to be in response to reports that the first invitations to enter DPA negotiations have been sent, exhorts the SFO to reserve DPAs to cases in which “there is a very strong public interest argument in favour, . . . the harm caused to victims and the community is minimal, and where there has also been a genuine self-report, full cooperation and remedial action.” The letter also expresses concern that DPAs should not be used to assist companies in avoiding debarment from government contracting under EU procurement regulations. Indeed, the letter goes so far as to say that DPAs should not be used in “politically sensitive cases,” although the notion of what it politically sensitive is not defined.[88]

The letter also expresses the view that immunities from prosecution under a DPA should not extend to individual employees, or to conduct not publicly disclosed, and that the DPA process must be conducted with “the utmost transparency,” including the following disclosures: (1) full particulars of any corrupt payments made, (2) the recipients of those payments, (3) the benefits obtained, and even (4) details of any alleged wrongdoing over which the prosecutor and the company disagree.[89] The letter further calls for financial sanctions to have “significant deterrent value,” reflecting the full harm and the full benefit associated with corrupt payments, including any potential advantages secured by way of market positioning vis-à-vis future tenders.[90]

The three NGOs go on to say that Victim and Community Impact Statements should be prepared in connection with DPA approval hearings before the Crown Court to enable victims to participate in the DPA process, and that “appropriate experts including civil society should be consulted,” given the difficulty of identifying victims in corruption cases. One class of victim the NGOs identify is “affected states” in cases of foreign bribery; they argue that such states should be afforded a means of participating in the DPA process, and informed at an early stage of the decision to enter into negotiations.[91]

The emerging picture is one of both prosecutors and the NGO sector envisioning the UK DPA regime as a means of securing significant leverage over corporate decision-making in connection with allegations of misconduct.

As we have noted here, we strongly support the use of DPAs as a tool for resolving allegations of corporate misconduct, but we would also caution against making the threshold requirements for entering into a DPA overly draconian and unduly burdensome. Sweeping public disclosures of unproven allegations and sensitive corporate information would disincentivize companies from cooperating with investigative bodies and from amicably and transparently resolving potential issues. DPAs are not a one-size-fits-all proposition; to be effective, both the threshold requirements for entry and the mitigation plans fashioned must be tailored to individual companies. These details should be trusted to prosecutor discretion and driven by the specifics of a given case. Care should be taken to avoid undue hardship to innocent parties and blunt, untailored terms that cause unnecessary collateral ramifications–including financial impacts causing profound economic harms to both companies and economic sectors. The very flexibility that makes DPAs such a useful tool of law enforcement can be eviscerated by such a straightjacket.

Updates from France: DPAs and Double Jeopardy

NPAs and DPAs frequently involve not only U.S. companies and U.S.-based conduct, but also foreign companies and international activities. Accordingly, securing an NPA or DPA with U.S. enforcement authorities may be only one piece of the puzzle, and companies are sometimes subject to prosecution abroad for allegations arising from the same actions. Recently, courts in France have taken up the question of whether this poses a jurisdictional problem, asking whether a corporate DPA-holder may (and should) face subsequent criminal charges in France for the same conduct underlying the DPA.

Article 113-9 of the French Criminal Code provides that a French citizen may not be prosecuted in France for extraterritorial conduct if the citizen has been tried abroad for the same set of facts and any sentence has been served.[92] The same holds for foreign citizens accused of inflicting harm on French citizens.[93] This provision has been extended in recent years to entities holding plea agreements in U.S. courts,[94] but the French judiciary has never before held that a U.S. NPA or DPA barred subsequent French prosecution.[95]

On June 18, 2015, however, the Paris Criminal Court of First Instance reportedly applied the French double jeopardy law to DPAs in acquitting 14 corporate defendants that had been accused of paying bribes to Iraqi officials in connection with the United Nations Oil-for-Food Program.[96] Several of the acquitted companies, including Renault Trucks, had previously entered into a DPA with DOJ, and these companies argued that their prior settlements “barred French prosecutors from bringing a case based on the same misconduct.” [97] While the court’s final opinion has not yet been released, defense counsel have reported that the court agreed with this argument.[98]

Similarly, shortly after this ruling, the French court scheduled to hear charges against Total S.A. (“Total”)–another French company swept up in the Oil-for-Food Program prosecutions–reportedly placed that trial on hold pending the expiration of Total’s 2013 DPA with DOJ.[99] According to reports, this trial was postponed because it would be “unfair for Total to face trial while the DPA was still active.” [100] It is expected that, upon the DPA’s expiration in 2016, Total will raise the argument that French double jeopardy law mandates acquittal.

This early trend of applying double jeopardy principles to DPAs raises interesting questions that may have far-reaching impacts on domestic and foreign investigations and settlements. Will other countries with similar double jeopardy laws follow suit? Will the knowledge that bringing charges against a company could preclude prosecution elsewhere influence U.S. enforcement authorities’ exercise of prosecutorial discretion, or the settlements they seek? And will DPAs issued in foreign countries–like the UK–be viewed as similarly preclusive of prosecution in the U.S. and around the world? Further, as certain areas of the law–like anti-bribery–achieve international parity among many states, will the prospect of double jeopardy fuel a race among nations to be the first to bring charges against an entity?

While the French court rulings may represent the very early stage of a developing trend, such a development likely would require greater international cooperation among prosecutors. Corporations, on the other hand, will desire some degree of certainty and transparency when concluding settlements in one jurisdiction regarding that settlement’s preclusive effects in other fora. Such considerations necessarily will enter into the costs and benefits calculus of a corporate entity’s determination when weighing a potential DPA in certain jurisdictions.

APPENDIX: 2015 Non-Prosecution and Deferred Prosecution Agreements

The chart below summarizes the agreements concluded by DOJ and the SEC during the first half of 2015. The complete text of each publicly available agreement is hyperlinked in the chart.

The figures for “Monetary Penalties” may include amounts not strictly limited to an NPA or a DPA, such as fines, penalties, forfeitures, and restitution requirements imposed by other regulators and enforcement agencies, as well as amounts from related settlement agreements, all of which may be part of a global resolution in connection with the NPA or DPA, paid by the named entity and/or subsidiaries. The term “Monitor” includes traditional compliance monitors, self-reporting arrangements, and other monitorship arrangements found in settlement agreements.

APPENDIX

|

||||||||

|

Company |

Agency |

Alleged Violation |

Type |

Monetary Penalties |

Monitor |

Term of DPA/NPA |

||

|

Ansun Biopharma |

S.D. Cal. |

Fraud; False Claims Act |

DPA |

$2,149,600 |

No |

6 months |

||

|

DOJ Tax |

Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses |

NPA |

$3,022,000 |

No |

48 months |

|||

|

DOJ Tax |

Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses |

NPA |

$4,150,000 |

No |

48 months |

|||

|

S.D. WVa. |

Bank Secrecy Act |

DPA |

$2,200,000 |

No |

12 months |

|||

|

DOJ Tax |

Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses |

NPA |

$1,810,000 |

No |

48 months |

|||

|

DOJ Tax |

Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses |

NPA |

$4,619,000 |

No |

48 months |

|||

|

DOJ Tax |

Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses |

NPA |

$211,000,000 |

No |

48 months |

|||

|

DOJ Consumer Protection |

FIRREA |

DPA |

$4,900,000 |

No |

24 months |

|||

|

DOJ AFMLS; S.D.N.Y. |

Trade Sanctions/ IEEPA/ Export; BSA |

DPA |

$1,452,000,000 |

Yes |

36 months |

|||

|

DOJ Fraud; DOJ Antitrust |

Fraud |

DPA |

$2,369,000,000 |

Yes |

36 months |

|||

|

Digital Reveal, LLC |

E.D.N.C. |

Anti-Gambling Compliance |

NPA |

$0 |

No |

60 months and 56 days (expires July 1, 2020) |

||

|

DOJ Tax |

Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses |

NPA |

$2,066,000 |

No |

48 months |

|||

|

C.D. Cal. |

Environmental |

NPA |

$133,000,000 |

Yes |

120 months |

|||

|

DOJ Tax |

Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses |

NPA |

$5,414,000 |

No |

48 months |

|||

|

E.D.N.Y. |

Fraud (Overbilling) |

NPA |

$7,007,046 |

Yes |

24 months |

|||

|

DOJ Fraud; E.D. Va. |

FCPA |

NPA |

$7,100,000 |

Yes |

36 months and 7 days |

|||

|

DOJ Tax |

Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses |

NPA |

$34,000 |

No |

48 months |

|||

|

DOJ Tax |

Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses |

NPA |

$826,000 |

No |

48 months |

|||

|

SEC |

FCPA |

DPA |

$3,407,875 |

No |

24 months |

|||

|

DOJ Tax |

Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses |

NPA |

$287,000 |

No |

48 months |

|||

|

N.D. Cal. |

Anti-Money Laundering Compliance |

NPA |

$700,000 |

Yes |

36 months |

|||

|

DOJ Tax |

Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses |

NPA |

$11,510,000 |

No |

48 months |

|||

|

DOJ Tax |

Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses |

NPA |

$9,090 |

No |

48 months |

|||

|

E.D.N.C. |

Anti-Gambling Compliance |

NPA |

$0 |

No |

No set term |

|||

|

DOJ Tax |

Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses |

NPA |

$1,363,000 |

No |

48 months |

|||

|

DOJ Tax |

Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses |

NPA |

$17,807,000 |

No |

48 months |

|||

|

E.D.N.C. |

Anti-Gambling Compliance |

NPA |

$0 |

No |

60 months and 56 days (expires July 1, 2020) |

|||

|

DOJ Tax |

Tax-Related and Monetary Transactions Offenses |

NPA |

$4,253,000 |

No |

48 months |

|||

|

E.D.N.C. |

Anti-Gambling Compliance |

NPA |

$0 |

No |

60 months and 56 days (expires July 1, 2020) |

|||

[1] Leslie R. Caldwell, Assistant Att’y Gen, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Remarks at the New York University Center on the Administration of Criminal Law’s Seventh Annual Conference on Regulatory Offenses and Criminal Law (Apr. 14, 2015), http://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/assistant-attorney-general-leslie-r-caldwell-delivers-remarks-new-york-university-center.

[2] Leslie R. Caldwell, Assistant Att’y Gen, Dep’t of Justice, Remarks at the New York University Center on the Administration of Criminal Law’s Seventh Annual Conference on Regulatory Offenses and Criminal Law (Apr. 14, 2015), http://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/assistant-attorney-general-leslie-r-caldwell-delivers-remarks-new-york-university-center.

[3] Leslie R. Caldwell, Assistant Att’y Gen, Dep’t of Justice, Remarks at the New York University Center on the Administration of Criminal Law’s Seventh Annual Conference on Regulatory Offenses and Criminal Law (Apr. 14, 2015), http://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/assistant-attorney-general-leslie-r-caldwell-delivers-remarks-new-york-university-center.

[4] Leslie R. Caldwell, Assistant Att’y Gen, Dep’t of Justice, Remarks at the New York University Center on the Administration of Criminal Law’s Seventh Annual Conference on Regulatory Offenses and Criminal Law (Apr. 14, 2015), http://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/assistant-attorney-general-leslie-r-caldwell-delivers-remarks-new-york-university-center.

[5] See Senator Elizabeth Warren, The Unfinished Business of Financial Reform, Remarks at the Levy Institute’s 24th Annual Hyman P. Minsky Conference, 4 (Apr. 15, 2015), available at http://www.warren.senate.gov/files/documents/Unfinished_Business_20150415.pdf.

[6] See Senator Elizabeth Warren, The Unfinished Business of Financial Reform, Remarks at the Levy Institute’s 24th Annual Hyman P. Minsky Conference, 4 (Apr. 15, 2015), available at http://www.warren.senate.gov/files/documents/Unfinished_Business_20150415.pdf.

[7] Barney Jopson & Gina Chon, Anti-Wall Street Senator Lambasts Bank Non-Prosecution Deals, Fin. Times, Apr. 15, 2015, http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/bce88134-e394-11e4-9a82-00144feab7de.html.

[8]See Misbehaving Banks Must Have Their Day in Court, Fin. Times ,, Apr. 19, 2015, http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/f26a9acc-e515-11e4-a02d-00144feab7de.html#axzz3cOiMZaLN.

[9]See Misbehaving Banks Must Have Their Day in Court, Fin. Times, Apr. 19, 2015, http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/f26a9acc-e515-11e4-a02d-00144feab7de.html#axzz3cOiMZaLN.

[10] See F. Joseph Warin, Senator Warren, Let the ‘Cops’ Do Their Jobs, The Hill (Apr. 27, 2015, 4:00 p.m.), http://thehill.com/blogs/congress-blog/economy-budget/240042-senator-warren-let-the-cops-do-their-jobs, also available at http://www.gibsondunn.com/wp-content/uploads/documents/publications/Warin-Senator-Warren-Let-The-Cops-Do-Their-Job-The-Hill-04.27.2015.pdf.

[11] See F. Joseph Warin, Senator Warren, Let the ‘Cops’ Do Their Jobs, The Hill (Apr. 27, 2015, 4:00 p.m.), http://thehill.com/blogs/congress-blog/economy-budget/240042-senator-warren-let-the-cops-do-their-jobs, also available at http://www.gibsondunn.com/wp-content/uploads/documents/publications/Warin-Senator-Warren-Let-The-Cops-Do-Their-Job-The-Hill-04.27.2015.pdf.

[12] E.g., United States v. Aibel Group Ltd., Deferred Prosecution Agreement, H-07-005, at 6 (Jan. 4, 2007) (implementing a revised compliance and governance structure including the appointment of an independent executive board member, the establishment of a compliance committee, and the engagement of outside compliance counsel); TNT Software LLC NPA, ¶ 6-7 (May 5, 2015) (expressly prohibiting certain sweepstakes-related activities without expressing any opinion as to the legality of such conduct, and further requiring written notice to the U.S. Attorney’s Office if TNT should engage in any sweepstakes activity not covered by the prohibition).

[13] Senator Elizabeth Warren, The Unfinished Business of Financial Reform, Remarks at the Levy Institute’s 24th Annual Hyman P. Minsky Conference, 4 (Apr. 15, 2015), available at http://www.warren.senate.gov/files/documents/Unfinished_Business_20150415.pdf. .

[14] United States v. Fokker Services B.V., No. 1:14-cr-00121-RJL, 2015 WL 729291 at *3 (D.D.C. Feb. 5, 2015) (quoting United States v. Payner, 447 U.S. 727, 735 n. 7).

[15] Government’s Memorandum in Support of Deferred Prosecution Agreement Reached with Fokker Services B.V. at 2, United States v. Fokker Services B.V., No. 1:14-cr-00121-RJL (D.D.C. July 7, 2014).

[16] United States v. Fokker Services B.V., No. 1:14-cr-00121-RJL, 2015 WL 729291 at *3 (D.D.C. Feb. 5, 2015) (quoting 18 U.S.C. § 3161(h)(2)).

[17] United States v. Fokker Services B.V., No. 1:14-cr-00121-RJL, 2015 WL 729291 at *4 (D.D.C. Feb. 5, 2015).

[18] United States v. Fokker Services B.V., No. 1:14-cr-00121-RJL, 2015 WL 729291 at *4 (D.D.C. Feb. 5, 2015) (quoting United States v. HSBC Bank, N.A., No. 12–CR–763, 2013 WL 3306161, at *4 (E.D.N.Y. July 1, 2013)).

[19] United States v. Fokker Services B.V., No. 1:14-cr-00121-RJL, 2015 WL 729291 at *5 (D.D.C. Feb. 5, 2015) (quoting United States v. Jones, 433 F.2d 1176, 1181–82 (D.C.Cir.1970)).

[20] United States v. Fokker Services B.V., No. 1:14-cr-00121-RJL, 2015 WL 729291 at *5-6 (D.D.C. Feb. 5, 2015).

[21] Order, United States v. Fokker Services B.V., No. 15-3017 (June 17, 2015).

[22] United States v. HSBC Bank, No. 12-cr-763, 2013 WL 3306161 at *6 (E.D.N.Y. July 1, 2013).

[23] United States v. HSBC Bank, No. 12-cr-763, 2013 WL 3306161 at *7 (E.D.N.Y. July 1, 2013).

[24] United States v. HSBC Bank, No. 12-cr-763, 2013 WL 3306161 at *11 (E.D.N.Y. July 1, 2013).

[25] Status Report, United States v. HSBC Bank, No. 12-cr-763 (E.D.N.Y. April 1, 2015).

[26] Government’s Motion for Leave to File Monitor’s Report Under Seal at 3, United States v. HSBC Bank, No. 12-cr-763 (E.D.N.Y. June 1, 2015) (quoting from Judge Gleeson’s original opinion in which he emphasized that the decision whether to prosecute is vested in the Executive Branch alone and is not amenable to judicial review).

[27] United States v. HSBC Bank, No. 12-cr-763, 2013 WL 3306161 at *11 (E.D.N.Y. July 1, 2013).

[28] 31 CFR § 501 et seq., Appendix A to Part 501 (2009).

[32] Commerzbank’s monetary penalties totaled $1.45 billion, including amounts paid in a concurrent settlement with the state of New York.

[33] Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Commerzbank AG Admits to Sanctions and Bank Secrecy Violations, Agrees to Forfeit $563 Million and Pay $79 Million Fine Combined with Payments to Regulators (Mar. 12, 2015), available at http://www.justice.gov/usao-dc/pr/commerzbank-ag-admits-sanctions-and-bank-secrecy-violations-agrees-forfeit-563-million.

[34] 31 CFR § 501 et seq., Appendix A to Part 501 (2009).

[35] Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Treasury, Treasury Announces $91 Million Settlement with Weatherford International Ltd. for Apparent Sanctions Violations (Nov. 26, 2013), available at http:

//www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/jl2223.aspx.

[36] Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Three Subsidiaries of Weatherford International Limited Agree to Plead Guilty to FCPA and Export Control Violations (Nov. 26, 2013), available at http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/three-subsidiaries-weatherford-international-limited-agree-plead-guilty-fcpa-and-export; see also Deferred Prosecution Agreement at 3, United States v. Weatherford International Ltd., No. 13-cr-733 (Nov. 26, 2013).

[37] Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Treasury, Dal-Tech Devices, Inc. Agreed to Pay $10,000 (Jan. 18, 2013), available at http://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/CivPen/Documents/

20130118_daltech.pdf.

[38] Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Assistant Attorney General Leslie R. Caldwell Delivers Remarks at a Press Conference on Foreign Exchange Spot Market Manipulation (May 20, 2015), available at http://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/assistant-attorney-general-leslie-r-caldwell-delivers-remarks-press-conference-foreign.

[39] Brett Wolf, U.S. Warns Banks it May Revoke Some Money-Laundering Settlements, Reuters, Mar. 16, 2015, http://uk.reuters.com/article/2015/03/16/banks-moneylaundering-idUKL2N0WI1BA20150316.

[40] Brett Wolf, U.S. Warns Banks it May Revoke Some Money-Laundering Settlements, Reuters, Mar. 16, 2015, http://uk.reuters.com/article/2015/03/16/banks-moneylaundering-idUKL2N0WI1BA20150316.

[41] The $2.520 billion coordinated DOJ FX settlement included: (1) Barclays ($650 million); (2) Citigroup ($925 million); (3) JP Morgan ($550 million); (4) RBS ($395 million).

[42] Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Assistant Attorney General Leslie R. Caldwell Delivers Remarks at a Press Conference on Foreign Exchange Spot Market Manipulation (May 20, 2015), available at http://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/assistant-attorney-general-leslie-r-caldwell-delivers-remarks-press-conference-foreign.

[43] Loretta Lynch, U.S. Att’y Gen., , Remarks at a Press Conference on Foreign Exchange Spot Market Manipulation (May 20, 2015), http://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/attorney-general-lynch-delivers-remarks-press-conference-foreign-exchange-spot-market.

[44] Loretta Lynch, U.S. Att’y Gen., Remarks at a Press Conference on Foreign Exchange Spot Market Manipulation (May 20, 2015), http://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/attorney-general-lynch-delivers-remarks-press-conference-foreign-exchange-spot-market.

[45] See generally U.S.DEP’T OF JUSTICE, PROGRAM FOR NON-PROSECUTION AGREEMENTS OR NON-TARGET LETTERS FOR SWISS BANKS (Aug. 29, 2013).

[46] U.S. DEP’T OF JUSTICE, PROGRAM FOR NON-PROSECUTION AGREEMENTS OR NON-TARGET LETTERS FOR SWISS BANKS, I.B.6, I.B.9, II (Aug. 29, 2013). With regard to the applicable time period, the Program provides that the “Applicable Period” shall mean “the period between August 1, 2008, and either (1) the later of December 31, 2014, or the effective date of an FFI Agreement, or (b) the date of the Non-Prosecution Agreement or Non-Target Letter, if that date is earlier than December 31, 2014, inclusive. Because no Non-Prosecution Agreements were issued prior to December 31, 2014, the effective cut-off date for the Applicable Period is the later of December 31, 2014, or the execution of an FFI Agreement.

[47] U.S. DEP’T OF JUSTICE, PROGRAM FOR NON-PROSECUTION AGREEMENTS OR NON-TARGET LETTERS FOR SWISS BANKS, I.B.3, I.B.9 (Aug. 29, 2013); Agreement for Cooperation to Facilitate the Implementation of FATCA, U.S.-Switz., Feb. 14, 2013.

[48] U.S. DEP’T OF JUSTICE, PROGRAM FOR NON-PROSECUTION AGREEMENTS OR NON-TARGET LETTERS FOR SWISS BANKS, II.D.1 (Aug. 29, 2013).

[49] See U.S.DEP’T OF JUSTICE, PROGRAM FOR NON-PROSECUTION AGREEMENTS OR NON-TARGET LETTERS FOR SWISS BANKS, II.D.2 (Aug. 29, 2013).

[50] U.S. DEP’T OF JUSTICE, PROGRAM FOR NON-PROSECUTION AGREEMENTS OR NON-TARGET LETTERS FOR SWISS BANKS, II.D.3 (Aug. 29, 2013).

[51] See U.S. DEP’T OF JUSTICE, PROGRAM FOR NON-PROSECUTION AGREEMENTS OR NON-TARGET LETTERS FOR SWISS BANKS, II.H (Aug. 29, 2013).

[52] U.S. DEP’T OF JUSTICE, PROGRAM FOR NON-PROSECUTION AGREEMENTS OR NON-TARGET LETTERS FOR SWISS BANKS, II.H (Aug. 29, 2013).

[53] U.S. DEP’T OF JUSTICE, JUNE 2014 UPDATE ON THE TAX DIVISION’S PROGRAM FOR NON-PROSECUTION AGREEMENTS OR NON-TARGET LETTERS FOR SWISS BANKS (June 5, 2014), http://www.justice.gov/opa/blog/june-2014-update-tax-division-s-program-non-prosecution-agreements-or-non-target-letters.

[54] Karen Freifeld, ‘Stay Tuned’ for More Swiss Bank Deals Over Tax Evasion: U.S. Official, Reuters, Apr. 8, 2015, http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/04/08/banks-swiss-usa-idUSL2N0X51OP20150408.

[55] John Letzing, Julius Baer Sets Aside $350 Million to Settle U.S. Tax Probe, Wall St. J. (June 23, 2015, 1:46 p.m. ET), http://www.wsj.com/articles/julius-baer-sets-aside-350-million-to-settle-u-s-tax-probe-1435081437.

[56] Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Credit Suisse Pleads Guilty to Conspiracy to Aid and Assist U.S. Taxpayers in Filing False Returns (May 19, 2014), http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/credit-suisse-pleads-guilty-conspiracy-aid-and-assist-us-taxpayers-filing-false-returns.

[57] Memorandum from Craig S. Morford, Acting Deputy Att’y Gen., to Heads of Dep’t Components and U.S. Att’ys 4 (Mar. 7, 2008), available at http://www.justice.gov/dag/morford-useofmonitorsmemo-03072008.pdf.

[58] Tiffany Kary, HSBC Judge Seeks More Information about Sanctions Compliance, Bloomberg Bus., (May 4, 2015), http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-05-04/hsbc-judge-seeks-more-information-about-sanctions-compliance.

[59] Letter in Support of Government’s Motion for Leave to File Monitor’s Report Under Seal at 3, United States v. HSBC Bank, No. 12-cr-763 (E.D.N.Y. June 1, 2015) (quoting Nixon v. Warner Communications, Inc., 435 U.S. 589, 597 (1978)), ECF No. 35.

[60] Letter in Support of Government’s Motion for Leave to File Monitor’s Report Under Seal at 3, United States v. HSBC Bank, No. 12-cr-763 (E.D.N.Y. June 1, 2015) (quoting Hartford Courant Co. v. Pellegrino, 380 F.3d 83, 91 (2d Cir. 2004)), ECF No. 35.

[61] Letter in Support of Government’s Motion for Leave to File Monitor’s Report Under Seal at 7, United States v. HSBC Bank, No. 12-cr-763 (E.D.N.Y. June 1, 2015), ECF No. 35.

[62] Letter in Support of Government’s Motion for Leave to File Monitor’s Report Under Seal at 7, United States v. HSBC Bank, No. 12-cr-763 (E.D.N.Y. June 1, 2015), ECF No. 35.

[63] Letter in Support of Government’s Motion for Leave to File Monitor’s Report Under Seal at 7-8, United States v. HSBC Bank, No. 12-cr-763 (E.D.N.Y. June 1, 2015), ECF No. 35.

[64] Letter in Support of Government’s Motion for Leave to File Monitor’s Report Under Seal at 11-12, United States v. HSBC Bank, No. 12-cr-763 (E.D.N.Y. June 1, 2015), ECF No. 35.

[65] Deferred Prosecution Agreement, United States v. Royal Bank of Scotland, 3:13-CR-74-MPS (Feb. 5, 2013), Att. A, ¶ 14.

[66] Deferred Prosecution Agreement, United States v. Royal Bank of Scotland, 3:13-CR-74-MPS (Feb. 5, 2013), ¶ 2 n. 1.

[67] Deferred Prosecution Agreement, United States v. Royal Bank of Scotland, 3:13-CR-74-MPS (Feb. 5, 2013), ¶ 2 n. 1.

[68] Order to Produce to the High Court of Justice, United States v. Royal Bank of Scotland , 3:13-CR-74-MPS (Mar 10, 2015), ¶ .

[69] Property Alliance Group Limited v. Royal Bank of Scotland, [2015] EWHC 321 (Ch) ¶ 2.

[70] Property Alliance Group Limited v. Royal Bank of Scotland, [2015] EWHC 321 (Ch) ¶ 6.

[71] Property Alliance Group Limited v. Royal Bank of Scotland, [2015] EWHC 321 (Ch) ¶ 15.

[72] Property Alliance Group Limited v. Royal Bank of Scotland, [2015] EWHC 321 (Ch) ¶ 16.

[73] Property Alliance Group Limited v. Royal Bank of Scotland, [2015] EWHC 321 (Ch) ¶ 16.

[74] Property Alliance Group Limited v. Royal Bank of Scotland, [2015] EWHC 321 (Ch) ¶ 24.

[75] Property Alliance Group Limited v. Royal Bank of Scotland, [2015] EWHC 321 (Ch) ¶ 34; see also Heather Rankin, Herbert Smith Freehills LLP, High Court Orders Disclosure Despite Risk of Prosecution for Criminal Contempt under US Law (March 23, 2015), available at http://hsfnotes.com/fsrandcorpcrime/2015/03/23/uk-high-court-orders-disclosure-despite-risk-of-prosecution-for-criminal-contempt-under-us-law/.

[76] Property Alliance Group Limited v. Royal Bank of Scotland, [2015] EWHC 321 (Ch) ¶ 35.

[77] Property Alliance Group Limited v. Royal Bank of Scotland, [2015] EWHC 321 (Ch) ¶ 35.

[78] Order Granting Motion for Clarification Concerning Court’s Oral Order of April 12, 2013, United States v. Royal Bank of Scotland, No. 3:13-cr-74 (Mar. 10, 2015).

[79] Property Alliance Group Limited v. Royal Bank of Scotland, [2015] EWHC 321 (Ch) ¶ 21.

[80] Property Alliance Group Limited v. Royal Bank of Scotland, [2015] EWHC 321 (Ch) ¶ 33.

[81] Public statements by senior SFO officials have suggested that a high bar will be set for companies to be considered for DPAs, with an expectation of corporate self-reporting going beyond employee conduct, and potentially involving admissions of company-level offenses.

[82] David Green, Dir., Serious Fraud Office, Ethical Business Conduct: An Enforcement Perspective, Address at PWC (Mar. 6, 2014), available at http://www.sfo.gov.uk/about-us/our-views/director’s-speeches/speeches-2014/ethical-business-conduct-an-enforcement-perspective.aspx.

[83] HM Gov’t, Dep’t for Bus., Innovation & Skills, UK Anti-Corruption Plan, 2014, ¶ 4.64; see also Bribery Act, 2010, c. 23, § 7 (U.K.).

[84] Ben Morgan, Joint Head of Bribery and Corruption, Serious Fraud Office, Compliance and Cooperation, Address at the Global Anti-Corruption and Compliance in Mining Conference 2015 (May 20, 2015), available at http://www.sfo.gov.uk/about-us/our-views/other-speeches/speeches-2015/ben-morgan-compliance-and-cooperation.aspx.

[85] Ben Morgan, Joint Head of Bribery and Corruption, Serious Fraud Office, Compliance and Cooperation, Address at the Global Anti-Corruption and Compliance in Mining Conference 2015 (May 20, 2015), available at http://www.sfo.gov.uk/about-us/our-views/other-speeches/speeches-2015/ben-morgan-compliance-and-cooperation.aspx.

[86] Ben Morgan, Joint Head of Bribery and Corruption, Serious Fraud Office, Compliance and Cooperation, Address at the Global Anti-Corruption and Compliance in Mining Conference 2015 (May 20, 2015), available at http://www.sfo.gov.uk/about-us/our-views/other-speeches/speeches-2015/ben-morgan-compliance-and-cooperation.aspx.

[87] Letter from Corruption Watch, Global Witness, and Transparency Int’l UK, to David Green QC, Dir., Serious Fraud Office (June 19, 2015), available at http://www.cw-uk.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/DPA-letter-to-David-Green-19-June-2015.pdf.

[88] Letter from Corruption Watch, Global Witness, and Transparency Int’l UK, to David Green QC, Dir., Serious Fraud Office (June 19, 2015), available at http://www.cw-uk.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/DPA-letter-to-David-Green-19-June-2015.pdf.

[89] Letter from Corruption Watch, Global Witness, and Transparency Int’l UK, to David Green QC, Dir., Serious Fraud Office (June 19, 2015), available at http://www.cw-uk.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/DPA-letter-to-David-Green-19-June-2015.pdf.

[90] Letter from Corruption Watch, Global Witness, and Transparency Int’l UK, to David Green QC, Dir., Serious Fraud Office (June 19, 2015), available at http://www.cw-uk.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/DPA-letter-to-David-Green-19-June-2015.pdf.

[91] Letter from Corruption Watch, Global Witness, and Transparency Int’l UK, to David Green QC, Dir., Serious Fraud Office (June 19, 2015), available at http://www.cw-uk.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/DPA-letter-to-David-Green-19-June-2015.pdf.

[92] See Code Pénal [C. Pén.] arts. 113-6-9 (Fr.).

[93] See Code Pénal [C. Pén.] arts. 113-6-9 (Fr.).

[94] E.g., Rahul Rose, French Trial on Hold Until U.S. DPA Expires, Global Investigations Rev., June 26, 2015, here.