February 18, 2016

This past year marked 50 years since the establishment of the federal Medicare and Medicaid programs, but U.S. enforcement agencies did more than commemorate the programs’ anniversary in 2015. Both the U.S. Department of Justice ("DOJ") and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services ("HHS") continued to develop new and more robust ways to pursue fraud, waste, and abuse in federal and state health care programs, and the proof was in the prosecutions. On the heels of a record-breaking 2014, 2015 proved to be yet another blockbuster year in health care fraud and abuse enforcement.

The past twelve months demonstrated that health care providers of all shapes and sizes remain in the government’s crosshairs. Even after years of regulatory and enforcement initiatives, the government managed to expand its efforts in significant ways in 2015. Among other notable developments, the government’s False Claims Act ("FCA") provider enforcement figures far surpassed last year’s record-breaking numbers in both the number of resolutions and the recovery amounts; the DOJ notched its largest criminal health care fraud takedown in the department’s history; and HHS’s Office of Inspector General ("HHS OIG") increased its enforcement efforts, using its civil monetary penalty and exclusion authorities. Meanwhile, on the legislative front, the U.S. House of Representatives’ passed the ground-breaking 21st Century Cures Act, which supports health care infrastructure innovation, including health information technology interoperability.

As in our 2014 Year-End Health Care Compliance and Enforcement Update on Providers ("2014 Year-End Update"), we discuss below regulatory and enforcement developments impacting health care providers. This update first addresses DOJ enforcement activity against health care providers specifically relating to civil and criminal FCA cases. Next, we discuss notable HHS enforcement activity, followed by Anti-Kickback Statute ("AKS") and Stark Law developments from this past year. Finally, we turn to significant government health program payment and reimbursement matters that developed during 2015. A collection of Gibson Dunn’s recent publications on health care issues impacting providers may be found on our website.

I. DOJ Enforcement Activity

DOJ has shown no signs of slowing its vigorous pursuit of health care fraud and enforcement cases in 2015. To the contrary, this year’s comments by Assistant Attorney General Leslie Caldwell indicate that the government continues to look for ways to expand those efforts. During her speech at the American Bar Association’s 25th Annual National Institute on Health Care Fraud, AAG Caldwell stated that DOJ will put a "high priority" on pursuing health care fraud cases against corporations and executives, and that she expects this to be a "growing" part of DOJ’s docket.[1]

AAG Caldwell also identified several areas of "emerging fraud trends" as "the latest frontiers in Medicare fraud": namely, cases involving Medicare Part D, laboratory services, hospital-based services, and hospice care.[2] Of course, these areas have been under scrutiny in the FCA enforcement space for some time, and in 2015, the government and relators alike continued to press cases involving these and other provider services with even greater fervor than before.

Indeed, the number of open health care fraud investigations of corporations multiplied in 2015, as DOJ "steer[ed] additional prosecutorial resources to this area" and expanded its use of data mining techniques to identify and pursue potential targets.[3] DOJ publicized its dedication to health care enforcement recently, emphasizing the outsized role health care resolutions played in the department’s overall FCA recoveries during Fiscal Year 2015.[4] Below we summarize the government’s 2015 enforcement efforts against providers in the FCA and criminal spaces.

A. False Claims Act

With record numbers of new cases filed almost every year over the past five years,[5] it should be no surprise that 2015 was another banner year for the government in FCA recoveries from health care providers. The government–and private whistleblowers (called qui tam "relators" under the FCA)–regularly employ the FCA to enforce all manner of government health program rules. Regardless of the health program rule at issue, the stakes are high in FCA cases: many providers submit thousands of claims to government payors each year, and thus the FCA’s per-claim penalty range of $5,500 to $11,000 creates staggering potential exposure even aside from the statute’s mandatory treble damages. As we explained in our 2015 Year-End False Claims Act Update, that penalty range may almost double in 2016 and the years to come.

1. FCA Recoveries from Providers

DOJ’s enhanced efforts in the health care fraud space allowed it to top its remarkable recoveries from health care providers last year. This year’s 195 FCA settlements against providers far surpassed the 77 from 2014, and the total recoveries–over $1.9 billion–greatly exceeded the $1.2 billion recovered in 2014.[6]

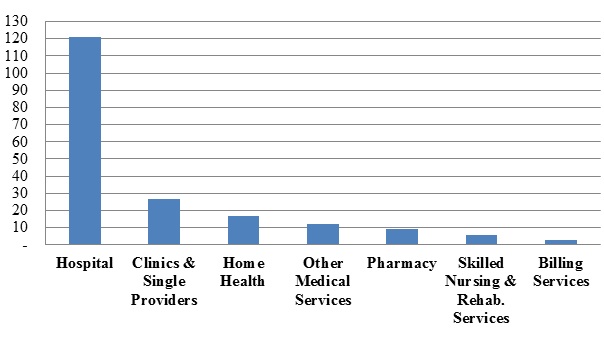

The 2015 settlements reflect a broad range of industries and legal theories, as exhibited in the graphs below.

Number of FCA Settlements with Providers, by Provider Type:

As in prior years, cases against hospitals, clinics, and single providers led the way in terms of FCA resolutions in 2015; of those, recoveries from hospitals (just over $808 million), not surprisingly, far outpaced recoveries from smaller providers (just over $51.3 million).

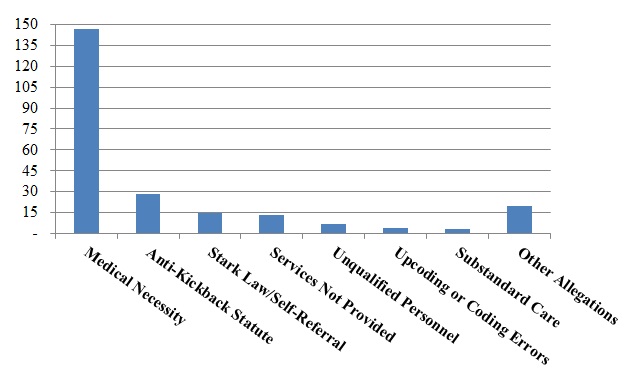

Number of FCA Settlements with Providers, by Allegation Type:

Also consistent with recent trends, the resolved matters primarily involved allegations that the provider’s care lacked medical necessity, although a significant number of cases were predicated on alleged AKS and Stark Law violations.[7]

In medical necessity cases, the government often pursues enforcement of myriad health program rules under the FCA on the theory that some of those rules are conditions of government payment. Under the government’s theory, providers that violate any such conditions may not receive reimbursement even for care that they provided. Thus, although the government alleges that these FCA cases are, at their core, about whether the care was "reasonable and necessary," they are often much more varied and complex, and may involve very specific program rules. This year was a banner year for large settlements in the medical necessity space, with two settlements in this area topping $200 million.

In October, following government intervention in a qui tam action, Millennium Health, a laboratory, paid the second largest settlement of the year ($256 million).[8] In that case, the government intervened and asserted that the company performed medically unnecessary urine drug and genetic tests and violated the AKS and Stark Laws by providing physicians free urine testing supplies in exchange for referrals. Those allegations led to $237 million of the total recovery.[9] The remainder–$19.2 million–was allocated to settle various administrative actions with CMS for administrative violations associated with the company’s billing practices. In addition, Millennium Health entered into a five-year Corporate Integrity Agreement ("CIA").[10]

The third largest monetary resolution of 2015, which resulted from a nationwide review of implantable cardioverter defibrillators ("ICDs"), was also the broadest resolution in terms of its scope.[11] The review, which began with a qui tam suit filed in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Florida, resulted in settlements totaling $250 million, with 70 defendants representing over 450 different hospitals.[12] The government alleged that the practitioners failed to abide by a "waiting period" between significant cardiac events and the implanting of ICDs.[13] The scope of the settlement could continue to increase as DOJ continues its investigation into additional hospitals and health systems.[14] The breadth of this settlement serves as a reminder that the government continues to pursue opportunities to capitalize on large-scale investigations.

Other medical necessity cases this year involved allegations that companies provided services at a level of care that was unnecessary, even if the type of service itself was appropriate for a patient’s specific condition. The largest such settlement in 2015 was a $28 million agreement reached with 32 hospitals across 15 states for allegedly billing inpatient services that could have been performed on an outpatient basis.[15] Covenant Hospice Inc. also agreed to pay $10.1 million for allegedly overbilling Medicare, TRICARE, and Medicaid for higher levels of hospice care unsupported by the documentation in the patient’s medical record.[16]

Cases premised on violations of anti-kickback statutes have long represented one of the most common theories of FCA liability. 2015 was no exception, as alleged violations of the AKS and Stark Law–which often go hand-in-hand–made up the largest categories of settlements next to medical necessity cases. Indeed, seven other settlements (in addition to the large Millennium Health settlement) involved alleged violations of both the AKS and the Stark Law and ranged in total value from $520,000 to $ 22.1 million.[17]

The past year’s AKS settlements demonstrate the extent to which the government scrutinizes the value of services provided when determining whether the true purpose of a financial arrangement was to induce referrals.[18] Indeed, the types of the arrangements at issue in these cases varied widely, from monetary grants[19] to less direct forms of remuneration, such as the provision of free medical supplies.[20]

In June, Hebrew Homes Health Network ("Hebrew Homes"), a nursing facility, paid $17 million to resolve allegations that it violated the AKS; this is the largest AKS-based FCA recovery to date against a nursing facility.[21] The government alleged that Hebrew Homes had a practice of hiring physicians for meaningless "medical director" positions for the exclusive purpose of providing the physicians with compensation in exchange for referrals. Notably, a new HHS OIG fraud alert addressed these types of arrangements, as we discuss in more detail in Part III.B. The Hebrew Homes settlement also highlights DOJ’s growing focus on cases involving nursing homes and skilled nursing facilities ("SNFs"), and may preview further actions to come.

The year 2015 also saw five FCA settlements in which alleged Stark Law violations were the sole theory of FCA liability. Although the Stark Law itself is a strict liability statute, the government and FCA relators often allege that, because Stark Law compliance is a condition of government payment, knowing violations of the statute are actionable under the FCA. Settlements of cases focused on alleged Stark Law violations in 2015 ranged from $3 million[22] to $69.5 million.[23] Other notable Stark Law developments are discussed in more detail in Part IV.

Finally, 2015 also brought a new record recovery in an FCA case in which the government declined to intervene, as DaVita Healthcare Partners, Inc. paid $450 million to resolve allegations that the company submitted false claims for payment of drugs "wasted" in the administration of treatment to dialysis patients.[24] At the time of the allegations, the Medicare program reimbursed dialysis providers for certain discarded drug product–for example, where the dosage of pre-packaged vials exceeded the amount prescribed for a given patient–where the provider was acting in good faith.[25] In the settled qui tam action, two relators had alleged that DaVita sought to maximize reimbursement by using "dosing grids" and enacting protocols on dosage size and frequency to maximize the amount of drugs administered, resulting in unnecessary waste.[26]

2. State FCA Settlements

Although federal recoveries in the FCA space outpaced recoveries by state agencies, this past year was a banner year for the states as well. In 2015, the total dollar value of recoveries by state agencies from health care providers topped $75 million.[27]

The biggest recovery in a state-run investigation this year was New York’s $22.4 million recovery from Trinity Homecare LLC for improperly billing for an injectable drug for treating at-risk premature infants.[28] According to the allegations, Trinity Homecare submitted claims to Medicaid even though it lacked documentation showing there was a valid prescription, or failed to maintain records demonstrating it delivered the drug.[29] The Trinity settlement is remarkable because of its size and the fact that a federal agency was not a driving force in the matter.

B. FCA-Related Case Law Developments

In 2015, there were several significant decisions in cases that are testing civil FCA liability standards. These developments have the potential to reshape plaintiff and defense strategies in FCA matters. The questions for 2016 will be whether appellate courts will allow the precedential value of these developments to stand and whether, in the meantime, district courts in other jurisdictions will follow these decisions as persuasive authority.

1. Implied Certification

As discussed in more detail in our 2015 Year-End FCA Update, the Supreme Court granted certiorari in December in a case that may cabin the government’s and relators’ use of the implied certification theory of FCA falsity. Under the implied certification theory, the government or relators allege that a government contractor’s claim for reimbursement implies that the contractor has complied with conditions of payment, which may be found in statutes, regulations, and contractual obligations. In Escobar, relators sought to impose FCA liability on a mental health clinic for submitting a Medicaid reimbursement claim while allegedly in violation of state licensing and supervision regulations. The two questions on which the Supreme Court granted certiorari in Escobar are:

1. Whether the "implied certification" theory of legal falsity under the FCA . . . is viable.

2. If the "implied certification" theory is viable, whether a government contractor’s reimbursement claim can be legally "false" under that theory if the provider failed to comply with a statute, regulation, or contractual provision that does not state that it is a condition of payment . . . or whether liability for a legally "false" reimbursement claim requires that the statute, regulation, or contractual provision expressly state that it is a condition of payment . . . .[30]

Because the implied certification theory underpins many FCA actions against providers–especially those premised on Medicare and Medicaid regulations–the Supreme Court’s Escobar decision may dispose of some suits and alter the landscape for many others.

2. Falsity

In United States ex rel. Paradies v. AseraCare, Inc., one of the most closely watched FCA cases of the year, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Alabama bifurcated the trial. The court decided to address initially the question of whether the defendant submitted false claims and then, as necessary, evaluate all other elements of the government’s case, including knowledge.[31] We are not aware of another decision to bifurcate a trial in this way in the storied 150-year history of the FCA.

During the trial’s first stage, the government’s only evidence of falsity consisted of a medical expert’s opinion.[32] Nevertheless, the jurors sided with the government. But, after the verdict, the court acknowledged that it "misstepped" by not advising the jury that the FCA requires proof of an objective falsehood and that "a mere difference of opinion, without more, is not enough to show falsity."[33] The court granted AseraCare’s motion for a new trial and decided, sua sponte, to reconsider whether summary judgment on the issue of falsity would be appropriate.[34] At the heart of the court’s order was its conclusion that FCA liability requires objective falsity (rather than a mere subjective difference in medical opinion between physicians).[35] This case will be instrumental in defending future FCA actions that primarily rely on differing medical opinions.

Based on the evidence presented at trial–where even the government’s own witnesses noted that their opinions about the propriety of treatment had changed during the course of their review of the patient files at issue–it seems that AseraCare is poised to defeat the government’s action. If AseraCare succeeds, an appeal to the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals is almost inevitable. In any event, AseraCare seems likely to remain at the forefront of discussion regarding the FCA’s scope, and we will continue to monitor and report on important developments in the case.

3. Statistical Sampling

As we reported in our 2014 Year End Update, two courts last year endorsed the use of statistical methods to draw conclusions about liability for a broad universe of claims based on a smaller sample.[36] In the LifeCare and AseraCare cases from 2014, the courts allowed, at least preliminarily, the government to seek expansive liability for thousands of claims (and the associated, potentially massive damages and penalties) without establishing the falsity of each claim at issue. In 2015, two more district courts followed suit.[37]

In United States ex rel. Ruckh v. Genoa Healthcare LLC, the relator alleged that the defendant engaged in "flagrant upcoding" at fifty-three nursing facilities and sought to introduce expert testimony based on statistical sampling on the grounds that an individual analysis of each claim form was impractical.[38] The defendant moved to exclude the statistical sampling evidence, arguing that "statistical sampling and extrapolation cannot form the basis for liability in a [qui tam] case due to the lack of individual proof."[39] In denying the defendant’s motion, the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Florida concluded that "no universal ban on expert testimony based on statistical sampling applies in a qui tam action (or elsewhere), and no expert testimony is excludable in this action for that sole reason (although defects in method, among other evidentiary defects, might result in exclusion)."[40]

Similarly, in United States v. Robinson, the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Kentucky admitted statistical sampling in an FCA action against a physician and his employer for false claims submissions. The defendant argued that "the United States should not be allowed to focus on the specifics of only 30 claims out of 25,779 in order to establish violations under the FCA or as a basis for extrapolation of damages"; rather, according to the defendant, the court should conduct a claim-by-claim review of each claim at issue.[41] But the court disagreed, noting that "statistical sampling methods and extrapolation have been accepted in the Sixth Circuit and in other jurisdictions as reliable and acceptable evidence in determining facts related to FCA claims as well as other adjudicative facts."[42]

The government’s and relators’ attempts to impose sweeping liability for thousands (or tens of thousands) of claims using statistical sampling rather than individualized proof of the falsity of each claim is troubling, particularly in nationwide cases involving corporate defendants with multiple facilities and nuanced circumstances underlying each submitted claim. But more definitive guidance from the federal courts on this critical issue may be forthcoming. Indeed, the sampling approach faces a test in Michaels v. Agape Senior Community, Inc., which is currently at the briefing stage in the Fourth Circuit.[43] With that case, the Fourth Circuit has a chance to become the first appeals court to weigh in on the question of the validity of statistical sampling in the FCA context.

C. Criminal Prosecutions

This past year, DOJ pledged once more to increase criminal enforcement activity in the health care context. With potential criminal enforcement as a lever, DOJ intends to press companies to cooperate even more extensively than they have in response to past investigations. Last spring, AAG Caldwell reiterated that the Criminal Division will continue to apply the so-called Filip factors–the principles that have, since 2008, guided DOJ in its decisions to prosecute businesses in other corporate contexts–in the health care context as well.[44] For companies to receive any mitigating credit for cooperation, AAG Caldwell stressed, they cannot merely respond to government subpoenas; instead, companies must conduct comprehensive internal investigations and disclose "all available evidence of wrongdoing to [DOJ] prosecutors in a timely and complete way."[45] Such evidence also must include relevant information identifying the individuals who were involved, "no matter how high those individuals might have been on the corporate ladder."[46]

AAG Caldwell’s remarks set the stage for DOJ’s more formal articulation of its policy with regard to pursuing individuals responsible for corporate misconduct. On September 9, 2015, Deputy Attorney General Sally Quillian Yates issued a new policy memorandum to all DOJ attorneys entitled "Individual Accountability for Corporate Wrongdoing" (the "Yates Memorandum"). Although the Yates Memorandum acknowledges that federal prosecutors already implement many of its specified measures to pursue culpable individuals, the Yates Memorandum establishes "six key steps" designed to bolster DOJ’s efforts to "fully leverage its resources to identify culpable individuals at all levels in corporate cases."[47]

Most consequentially, the Yates Memorandum states that DOJ will provide no cooperation credit whatsoever to a company unless it provides DOJ all relevant facts relating to individual misconduct. This bright-line rule appears draconian, but it remains to be seen how DOJ determines what facts are "relevant" for purposes of this inquiry. Other guidelines set forth in the Yates Memorandum focus on DOJ’s own standards and practices: investigations should focus on potentially culpable individuals at the outset and irrespective of their financial means; DOJ Civil and Criminal attorneys should coordinate their inquiries; corporate cases should not be resolved without a clear path to resolving any pending individual investigations; and only in exceptional cases should government attorneys accept corporate settlements that immunize individuals from liability. For more information, please see Gibson Dunn’s detailed client update regarding the Yates Memorandum.[48]

Not surprisingly, DOJ attorneys did not wait for the Yates Memorandum to bring criminal cases against individual executives of large hospital-based providers this past year.

After last year’s Medicare fraud takedown that ensnared 90 individuals, on June 18, newly-minted Attorney General Loretta E. Lynch announced a takedown of historic proportions: DOJ’s investigation resulted in the arrest of 243 individuals accused of defrauding the government of approximately $712 million in a variety of schemes involving fraudulent billings, violations of the AKS, money laundering, and aggravated identity theft.[49] The Medicare Fraud Strike Force coordinated the monumental effort, which spanned 17 districts. It stands–for now–as the largest criminal health care fraud takedown in the DOJ’s history. Of the 243 individuals charged in the takedown, 46 were doctors, nurses, and other licensed medical providers.

The past year saw DOJ pursue–and secure–eye-catching punishments, as well. For example, the former president of a Houston-area hospital was recently sentenced after trial to 45 years’ imprisonment and ordered to pay almost $47 million in restitution for his role in a $158 million Medicare fraud scheme lasting from 2005 to 2012.[50] His son and another co-conspirator received sentences of 20 and 12 years of imprisonment and were ordered to pay about $7.5 million and $47 million in restitution, respectively.[51] The government accused the trio, along with seven other co-defendants who pleaded guilty,[52] of providing unnecessary intensive psychiatric treatment to patients who did not require such care, billing for care that was never provided, and paying kickbacks.

DOJ’s efforts against individuals associated with larger providers did not come at the cost of abandoning criminal actions against smaller outfits. For example, a husband and wife running a home health care clinic were recently sentenced to five years and one year, respectively, for their roles in a $2.4 million health care fraud scheme.[53] The court also ordered these defendants to pay approximately $1.5 million in restitution and to forfeit another $1.5 million.[54]

Given the success and scope of this year’s Medicare takedown, as well as the potential implications of the Yates Memorandum, the coming year may well see even more criminal enforcement activity.

II. HHS Enforcement Activity

A. HHS OIG Activity

1. 2015 Developments and Trends

After a blistering Fiscal Year 2014, during which HHS OIG reported nearly $5 billion in expected recoveries from its investigative and audit programs,[55] Fiscal Year 2015 proved significantly less lucrative. The agency reported expected recoveries of just $3.35 billion–no small amount, to be sure, but a decrease of 33% over the previous year’s total.[56] Much of the drop was attributable to a dramatic decrease in recoveries from investigative activities. The agency collected just $2.2 billion from its investigative work, just over half of the amount it collected in 2014 and the lowest total since Fiscal Year 2008.[57]

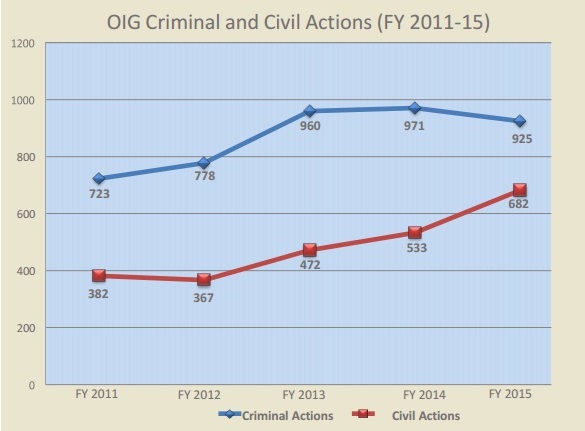

But the decrease in dollars should not suggest that Fiscal Year 2015 represented a slowdown in enforcement activity for HHS OIG. The 925 reported criminal actions were roughly on par with the figures from recent years, while the number of civil actions, including False Claims Act suits, civil monetary penalty ("CMP") settlements, and administrative recoveries saw a sharp uptick from previous years.[58]

Source: U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of Inspector Gen., Semiannual Report to Congress (April-September 2015)

a) HHS OIG’s New Litigation Team

This past year, HHS OIG demonstrated its commitment to expanding and supporting its enforcement work by announcing in June the creation of a new litigation team focused exclusively on CMP and exclusion cases.[59] After it is fully staffed, the team will consist of at least ten attorneys–double the resources previously dedicated to affirmative litigation–and will operate under the auspices of the Administrative and Civil Remedies Branch ("ACRB") of HHS OIG. The new litigation team, which will handle cases that DOJ opts not to pursue, is expected to continue identifying cases warranting exclusions or CMPs by relying on referrals from other HHS OIG departments, by pursuing breaches of CIAs, and by supplementing FCA settlements.[60] HHS OIG deputy branch chief Robert M. Penezic will lead the team.[61]

b) Notable Reports and Reviews

Medicare Part D billing has been a primary focus for HHS OIG in 2015. After noting in its mid-year update to its 2015 Work Plan that it is "seeing a significant increase in Part D Fraud[,]"[62] HHS OIG released a portfolio summarizing the agency’s investigations and guidance related to weaknesses in Part D program integrity.[63] The portfolio criticized CMS, concluding that CMS’s failure to require Part D plan sponsors to report information on fraud and failure to supervise plan sponsors effectively have contributed to the increase in fraud.[64] Among the troublesome figures noted by HHS OIG are the following: $1.2 billion in payments on claims with invalid prescriber identifiers in 2007; $15 million over three years in payments for prescriptions written by excluded providers; and payments on behalf of over 5,000 deceased beneficiaries in 2011.[65] HHS OIG recommended that CMS require plan sponsors to report fraud and abuse and improve its detection of improper claims for payment.[66] In connection with the release of the oversight portfolio, and of particular note to pharmacies, HHS OIG also reported that spending on Part D drugs has doubled since 2006, with particular growth in the spending on commonly abused opioids.[67] Based on an assessment of billing patterns, HHS OIG identified 1,400 pharmacies with unusually high billing patterns in at least one of five key measures. Those pharmacies alone accounted for $2.3 billion in Part D billing in 2014.[68]

During 2015, HHS OIG continued its work to help implement The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act ("PPACA"), issuing fourteen separate reviews of health insurance marketplaces, as well as twelve other PPACA reports.[69] Most dealt with PPACA programs in particular states, though a few looked more broadly at the implementation of PPACA requirements.

In one notable report, HHS OIG found that health care providers failed to consistently identify, report, and return Medicaid overpayments, as required by PPACA, by reconciling patient records with credit balances.[70] Approximately half the patient records reviewed by HHS OIG contained overpayments.[71] HHS OIG recommended that CMS issue Medicaid regulations similar to Medicare regulations that require providers to exercise reasonable diligence in identifying and returning overpayments.[72] The report likely heralds increased attention from CMS on issues related to reimbursement for Medicaid beneficiaries, so providers should confirm that they have established strong compliance policies for identifying overpayments.

Another HHS OIG report assessed compliance with the PPACA’s requirement that states terminate a provider’s participation in its state Medicaid program if the provider is terminated for reasons of fraud, integrity, or quality from another state’s Medicaid program.[73] HHS OIG found that 12% of providers terminated for cause in 2011 continued to participate in other states’ Medicaid programs as late as January 2014, costing those programs at least $7.4 million.[74] Twenty-five states did not require direct enrollment of providers participating in their Medicaid programs through managed care, meaning those providers could not be terminated and could continue operating without the state’s knowledge.[75] This report could signal a new wave of regulations related to provider enrollment and disclosure of termination information.

2. Significant HHS OIG Enforcement Activity

In addition to working in partnership with DOJ, HHS OIG has continued to combat fraud and promote compliance with the rules of federal health care programs through the use of its statutory exclusion authority, the assessment of CMPs, the establishment of CIAs, and the issuance of advisory opinions. As noted above, HHS OIG’s new litigation team will focus on these enforcement actions going forward.

a) Exclusions

HHS OIG continued its recent aggressive use of its statutory authority to exclude health care providers from government health programs in 2015. This penalty–the most lethal in HHS OIG’s arsenal–must be imposed upon any entity or individual engaged in patient-abuse related crime, felony health care fraud, or the use, manufacture, distribution or prescription of controlled substances.[76] HHS OIG also has discretion to impose exclusion for fraudulent conduct, for submitting claims for medically unnecessary procedures and treatments, or in connection with a license suspension or CIA.[77]

After a record-setting 2014, in which HHS OIG excluded slightly more than 4,000 entities and individuals from government health programs, HHS OIG just exceeded that total in Fiscal Year 2015, excluding 4,112 entities and individuals.[78] The exclusions include 53 entities, of which 14 are dental practices in Connecticut associated with a former dentist who has been on the exclusion list since 1998.[79] The clinics received almost $25 million in fraudulent Medicaid payments before the government detected the dentist’s illegal involvement.[80] The excluded entities also include 9 home health agencies, 6 transportation or ambulance companies, and 5 pharmacies.[81] Of the individuals placed on the exclusion list during the Fiscal Year, 304 were identified as business owners or executives, a slight drop from last year’s total of 326 owners or executives excluded.[82] Seventy-two of the excluded executives (almost 25%) operate home health agencies, and an additional 40 executives operate transportation or ambulance companies.[83]

b) Civil Monetary Penalties

Even without the assistance of a full-time litigation team this past year, HHS OIG used CMPs to great effect in 2015, assessing approximately $39 million in penalties against 54 individuals and entities. Of those CMPs, 45 (more than 80%) were assessed for false or fraudulent billing.[84] Additional penalties were assessed for patient dumping (violations of the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act ("EMTALA")),[85] violations of AKS and Stark Law physician self-referral prohibitions,[86] and drug price reporting requirements.[87]

For most of the individuals and entities assessed penalties for false and fraudulent billing, HHS OIG alleged that the entity had employed an individual that the entity knew or should have known was excluded from participation in federal health programs. This accounted for half of all CMPs assessed this year and 60% of CMPs for false and fraudulent billing.[88] The trend is an important reminder that providers–particularly larger entities–should take care to adopt systems that ensure they are compliant with federal health program rules that apply to their individual employees.

The largest CMPs assessed against providers in 2015 are summarized below:

- Vantage Oncology, LLC, and Gulf Coast Cancer Center: Alabama’s Vantage Oncology and related entities agreed to the year’s largest penalty. The company was assessed a fine of more than $9.5 million for submitting claims for radiation oncology that were performed without the direct supervision and timely review of a radiation oncologist.[89] Similar allegations resulted in a $2.6 million penalty for Gulf Coast Cancer Center and related entities.[90] Both settlements were reached in July 2015.

- W.A. Foote Memorial Hospital d/b/a Allegiance Health: Michigan-based Allegiance Health agreed to pay over $2.6 million to resolve allegations that the hyperbaric oxygen therapy services for which it submitted claims to federal health programs failed to meet provider-based regulations.[91] Allegiance self-reported the alleged fraud in connection with its CIA.[92] Allegiance Health entered into the CIA in June 2013 in connection with an FCA settlement over subjecting patients to medically inappropriate cardiology procedures.[93]

- Seton Family of Hospitals d/b/a Seton Shoal Creek Hospital: With a nearly $2.5 million settlement, Seton resolved a series of allegations in connection with its partial hospitalization program services. First, Seton allegedly ran afoul of kickback prohibitions by waiving collection of deductibles and coinsurance payments from Medicare patients, reducing their payment obligations and effectively providing them with remuneration.[94] In addition, HHS OIG alleged that Seton submitted claims for patients admitted to the partial hospitalization programs without appropriate physician certifications for admission, without physician certification of the ongoing need for such treatment, and without appropriately individualized treatment plans.[95]

c) Corporate Integrity Agreements

HHS OIG’s use of CIAs to ensure provider compliance with Medicare and Medicaid rules and regulations continues unabated through 2015. Indeed, 47 CIAs took effect over the course of the calendar year.[96]

As in past years, CIAs are frequently linked with other enforcement penalties. For example, San Diego’s Millennium Health entered into a five-year CIA after paying more than $250 million to settle allegations that it violated the FCA and AKS by billing for expensive and medically unnecessary drug tests and providing incentives for physicians to use Millennium.[97] In another example, Columbus Regional Healthcare System of Georgia agreed to a $25 million settlement regarding allegations that Columbus provided excessive salary and directorship payments to one of its physicians and submitted claims to Medicare and Medicaid for higher levels of care than were actually provided.[98] The settlement also required Columbus to enter into a five-year CIA.

Of the forty new CIAs, only one was a "quality-of-care" CIA. Under such CIAs, a provider typically must retain an independent quality monitor, peer review consultant, or clinical expert to review whether the provider is appropriately addressing patient care problems, using appropriate medical credentialing systems, or making only medically necessary and appropriate admissions and treatment decisions.[99] CF Watsonville East and CF Watsonville West, which operated two nursing homes in California, entered into a five-year quality-of-care CIA in May 2015 (and simultaneously agreed to a $3.8 million FCA settlement).[100] The complaint alleged that the nursing homes persistently overmedicated residents, leading to infections, injuries, and even premature deaths.[101]

d) Advisory Opinions

This past year, HHS OIG issued 15 advisory opinions–4 more than last year–assessing the legality of certain arrangements, at the request of federal health program participants, in the hopes of promoting good-faith compliance efforts.[102] As in prior years, the AKS took center stage in many of the advisory opinions.

Several HHS OIG advisory opinions from this past year focused on "preferred hospital" networks’ Medicare Supplemental Health Insurance policies–and the AKS implications of those policies. Four of 2015’s 14 advisory opinions addressed arrangements under which a Medigap insurer contracts with preferred hospitals for discounts on Medicare Part A deductibles and passes on a $100 credit off a renewal premium to policyholders who use the preferred hospitals.[103] In each opinion, HHS OIG found that the arrangement would not fall within the AKS safe harbors that cover waivers of beneficiary coinsurance and reduced premium amounts offered by health plans. HHS OIG nevertheless concluded that the exchanges represented a "low risk of fraud or abuse," such that HHS OIG would not seek penalties under the AKS or the CMP law prohibiting inducements to beneficiaries.[104]

In July, HHS OIG issued an advisory opinion regarding a hospital system’s proposal to lease non-clinical employees and provide operations and management services to a related psychiatric hospital for an amount equal to the hospital system’s "fully loaded costs" (i.e., salary plus benefits and overhead expense).[105] The parties were potential referral sources for each other.[106] Under a prior arrangement between the parties, with otherwise identical terms, the hospital also paid the system administrative fees.[107] Under the new proposal, the administrative fees, which the parties asserted were unallowable costs under applicable Medicare cost-reporting rules and not reimbursable, would be eliminated.[108]

HHS OIG concluded that the new proposal would implicate the AKS because the system would charge the hospital a rate below the fair market value for the leased employees and services, which may be considered remuneration in exchange for the hospital’s referrals.[109] Given the totality of the circumstances, however, HHS OIG determined that the arrangement posed "a low risk of fraud and abuse"[110] for the following reasons: (1) the parties structured the new proposal "in a manner they believe[d] was supported by applicable Medicare cost reporting rules"; (2) the new proposal would achieve cost efficiencies and a reduction in the hospital’s labor and operational costs, which might indirectly benefit federal health care programs; and (3) there was no evidence suggesting that the new proposal was designed to, or actually would, induce referrals.[111]

In August, HHS OIG issued an advisory opinion regarding a home health care provider’s policy to offer free introductory visits to patients who had previously selected the company as their home health provider.[112] The company certified that physicians or other health care professionals provided patients requiring home health services with a list of home health providers, and patients independently made their selection.[113] The company had no involvement in the patient’s selection process, and it did not offer or pay any remuneration to health care professionals that serve as referral sources.[114] After patients chose the company as their provider, a company employee offered a free introductory visit during which the company provided an overview of the home health experience and shared pictures and contact information for relevant company employees.[115] The company did not provide any federally reimbursable services during this visit.[116]

Relying on these facts, HHS OIG determined that, despite their "intrinsic value to patients," the company’s free visits "do not provide any actual or expected economic benefit to patients, and therefore do not constitute remuneration" under the AKS.[117] As a result, HHS OIG would "not impose administrative sanctions" on the company.[118]

In October, HHS OIG issued an advisory opinion regarding an integrated health system’s plan to offer free van shuttle services between certain medical facilities run by the system.[119] The system certified that the medical facilities served by the free services were not accessible by public transportation.[120] A large majority of the physicians working at the relevant facilities were employees of the system.[121] HHS OIG decided that the proposed transportation services "could potentially generate prohibited remuneration,"[122] but because the services "present[ed] a minimal risk of fraud and abuse under the [AKS],"[123] the HHS OIG would not impose administrative sanctions.

In reaching its conclusion, HHS OIG relied on the following facts: the system would (1) not tie the shuttle service to the volume or value of business from patients; (2) not offer air, luxury, or ambulance-level transportation; (3) not pay shuttle drivers on a per-patient basis; (4) offer the transportation service only locally; (5) not market or advertise the services to the general public; and (6) bear the costs of the services.[124]

The only proposed arrangement that HHS OIG found problematic in a 2015 advisory opinion was a laboratory company’s plan to offer free services to groups of patients in an apparent effort to secure exclusive arrangements with certain doctors’ offices.[125] According to the laboratory company, doctors’ offices face an administrative headache when dealing with multiple laboratories because of differing "reference ranges" for laboratory results and divergent system interfaces.[126] But doctors’ offices usually cannot move all of their referrals to a single laboratory company because patients’ insurance plans only pay for services at selected laboratory companies. To eliminate this barrier to exclusive deals with physicians’ practices, the laboratory company that sought guidance planned to offer free testing for any patient whose insurance did not cover its services, while continuing to bill for all other patients, including Medicare and Medicaid patients.[127] The company certified that it would not offer the doctors anything in exchange for their referrals, other than the ease of dealing with a single laboratory.[128] HHS OIG’s opinion concluded, however, that the arrangement nonetheless "could potentially generate prohibited remuneration under the anti-kickback statute" and suggested that HHS OIG would impose administrative sanctions if the company implemented the plan.[129]

HHS OIG took issue with the arrangement for two principal reasons. First, HHS OIG determined that the free laboratory services would constitute illegal remuneration because, "by declining to charge certain patients, the [company] would offer physician practices a means to work solely with the [company], reducing administrative and possibly financial burdens associated with using multiple laboratories."[130] This remuneration, in HHS OIG’s view, raised the risk that physicians would "inappropriate[ly] steer[] . . . patients, including Federal health care program beneficiaries."[131] Second, HHS OIG reasoned that the arrangement might create preferential pricing for privately insured patients in violation of federal law prohibiting a supplier from charging federal health care programs higher rates. Because federal health care programs cover laboratory services provided by the laboratory company, the proposed free testing would only have benefited privately insured individuals.[132] Therefore, HHS OIG viewed the plan as an effort to "relieve patients and their [insurers] of any obligation to pay in order to pull through all of the Federal health care program business, which would be charged at the full rate."[133]

3. Priorities for 2016

HHS OIG released its Fiscal Year 2016 Work Plan in October, announcing several new reviews of interest to health care providers.

In one review, HHS OIG will evaluate CMS’s use and validation of quality reporting data provided by hospitals.[134] The accuracy and completeness of such data is important, as HHS OIG noted, because it is used as part of the hospital value-based purchasing program and the hospital acquired condition reduction program.[135] The report is expected to be released in 2016.[136]

Another review will focus on payments received by hospitals for replacement of implanted medical devices.[137] Federal regulations provide for reduced payments for the replacement of these devices, but HHS OIG noted that prior reviews suggest that improper payments may have been made for replaced devices.[138]

In a move that may signal increased interest in potential violations of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 ("HIPAA"), HHS OIG also will review the adequacy of efforts undertaken by the Office for Civil Rights ("OCR") to ensure that providers protect electronic protected health information.[139] In particular, HHS OIG expressed concern that OCR has not appropriately implemented a procedure for conducting periodic audits under the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act ("HITECH").[140] These audits will assess whether health care providers have taken sufficient measures to protect the privacy of electronic health information.

B. CMS

During the past twelve months, CMS pursued several quality-of-care initiatives and addressed a massive backlog of payment challenges–discussed in Part VI.D. below. In addition, CMS also promoted enforcement initiatives through, among other measures, its data transparency programs and geographic moratoria. We address notable CMS priorities from the past year below.

1. Transparency and Data Accessibility

After last year’s launch of the "Open Payments" database, CMS devoted significant energy in 2015 to efforts to improve transparency and access to data related to the use of Medicare and Medicaid services. CMS released its second round of Open Payments data on June 30, 2015.[141] The searchable data set includes more than eleven million records of payments made in 2014 to physicians and teaching hospitals by drug and device manufacturers, accounting for more than $6 billion in payments.[142] These figures represent a significant increase from the 2013 data, released last year, which published four million records, accounting for just $3 billion in payments.[143]

In April, CMS released for the first time data on the prescription drugs prescribed by physicians and other health care providers.[144] The data includes information from more than one million providers and reflects more than $100 billion in prescription drugs and supplies under Medicare Part D.[145] The data identifies four drugs that accounted for more than $2 billion each: Nexium®, Advair Diskus®, Crestor®, and Abilify®.[146] Notably, the data also provides insight into the average total costs and costs per claim of different medical specialties.[147] Coupled with HHS OIG’s reports on Part D fraud, CMS’s data release confirms that Medicare Part D billing is a central focus of government regulators in 2015.

In June, CMS continued its data release with its third update to the Medicare hospital inpatient and outpatient charge data.[148] The release, which provides data from 2013, compares average charges for hospital services in connection with inpatient stays.[149] The data also provides average Medicare payment information for the same services.[150] The data reflects a steady increase in average hospital charges for the most common diagnoses.[151]

In October, CMS added to the data available in its provider utilization and payment files, releasing information on physicians and other health care professionals who supplied durable medical equipment, including wheelchairs, walkers, and diabetes supplies, to Medicare beneficiaries.[152] The data also includes prosthetics and orthotic devices, as well as certain drugs and nutritional products.[153] The data set represents $11 billion in Medicare payments distributed over 100 million claims by nearly 400,000 providers.[154]

Most recently, CMS expanded the data available on Physician Compare and Hospital Compare, tools created under PPACA to allow consumers to evaluate health care providers based on more than 100 quality measures.[155] In addition to releasing data from 2014 on existing quality measures, CMS added data on hospitals’ use of safe surgery practices and supplemented the available data regarding health care-associated infections with information regarding infections suffered by patients in medical and surgical wards.[156]

CMS has not only made additional data available to the public, but also increased access to detailed CMS data for the purposes of conducting in-depth research. CMS announced in June that innovators and entrepreneurs would be given access to the CMS Virtual Research Data Center, a secure CMS database on which they can review and analyze privacy-protected data files.[157] Data may be requested on a quarterly basis.[158] CMS hopes that allowing access to this data for approved research will lead to the development of better care management and predictive modeling tools.[159]

2. Moratoria and Other Enforcement Priorities

As discussed above, nursing homes, SNFs, assisted living facilities, hospices, and home health providers have come under DOJ’s microscope in recent years and CMS continues to lend support to DOJ in this regard.

In a January 2015 report, HHS OIG observed that CMS intends to focus its oversight and enforcement efforts on hospices and assisted living facilities.[160] For example, CMS will develop anti-fraud measures to crack down on hospices that are paid for providing routine care, even though their caregivers rarely visit beneficiaries.[161]

CMS also has continued to impose moratoria on certain geographic areas, as authorized by PPACA.[162] Under that authority, CMS may designate–based on consultations with DOJ and HHS OIG–a region as a "hot spot" for fraud and block any new provider enrollments within the region. CMS must then review the moratoria every six months.

To date, CMS has imposed moratoria in two waves: in 2013, it blocked home health program enrollments in Chicago and Miami and ground ambulance services in Houston;[163] and in 2014, it added Fort Lauderdale, Detroit, Dallas, and Houston to the home health moratorium and added Philadelphia to the ground ambulance services moratorium.[164] In February 2015, July 2015, and again in February 2016, CMS announced that it was extending all moratoria for another six months because "[t]he circumstances warranting the imposition of the moratoria have not yet abated" and "a significant potential for fraud, waste, and abuse continues to exist in these geographic areas."[165]

C. OCR and HIPAA Enforcement

According to an October 2015 report, OCR has reviewed and resolved more than 115,000 HIPAA complaints since compliance rules came into effect in 2003.[166] More than 23,000 of those cases have required changes to a covered entity’s policies or other corrective action measures. Although OCR has fielded an immense number of complaints, the agency’s enforcement efforts have yielded just twenty-six monetary settlements since 2003, totaling less than $23 million.[167] Moreover, despite the sheer magnitude of its effort, OCR still has approximately 6,500 open complaints.[168] And the increase in cyberattacks–like the one that compromised Anthem Health Insurance’s data early this past year[169]–and nationwide focus on data security suggests that OCR will continue to see a growth in interest in privacy protection for confidential patient information. As noted above, HHS OIG’s Fiscal Year 2016 Work Plan includes a review of OCR’s efforts to ensure that providers safeguard electronic protected health information.

1. 2015 Developments and Trends

Last summer, Jerome Meites, an OCR Chief Regional Counsel, warned that OCR would target "high impact cases," and recent penalties–including more than $10 million in HIPAA fines–would "be low in comparison to what’s coming up."[170] As of Halloween, this warning had not yet been fulfilled; OCR had announced just three settlements, collectively amounting to barely more than $1 million.[171] But OCR announced three additional settlements in November and December, and those resolutions accounted for 85% of the year’s collections.

In the meantime, the states originated several measures to protect the privacy of health information this year. A New Jersey law passed in January 2015 requires health insurance carriers to encrypt any information containing an individual’s name and Social Security number, driver’s license number, address, or identifiable health information.[172] Desktops, laptops, mobile devices, and computerized records must be "unreadable, undecipherable, or otherwise unusable by an unauthorized person."[173] In May, Connecticut’s Senate passed a similar bill.[174] This proposed legislation defines encryption as "the transformation of electronic data into a form in which meaning cannot be assigned without the use of a confidential process or key." Federal HIPAA regulations do not currently mandate encryption, although it is recommended where reasonable and appropriate.[175]

On the federal level, in an effort to promote compliance, OCR launched a portal to provide developers of health-related technology and mobile applications with guidance on the application of HIPAA rules to their products.[176] Users can submit questions, responses, and comments anonymously–and OCR will not use those postings against any individual or entity in an enforcement action.[177] Although OCR does not intend to respond to individual questions, the office posts resources and will consider the questions and comments in its efforts to develop formal guidance.[178] In the three months since the portal was created, users have posted fifteen questions and eighteen comments, addressing topics such as audit requirements and business associate relationships.[179]

2. HIPAA Enforcement Actions

OCR reached settlements totaling more than $6 million in 2015. More than half of that total resulted from OCR’s $3.5 million settlement with Triple-S Management Corporation.[180] OCR received multiple breach notifications from the company before launching an investigation. During the investigation, OCR found that Triple-S failed to implement adequate safeguards for protected health information, including electronic information, disclosed health information to an outside vendor despite lacking the required business associate agreement, and used more health information than necessary to carry out mailings. In addition to the monetary penalty, Triple-S must develop an appropriate risk management plan, launch a data privacy training program, and develop policies and procedures that will facilitate HIPAA compliance.[181]

The University of Washington Medicine ("UWM") fell victim to a classic cybersecurity lapse when an employee downloaded an email attachment that contained malware, compromising UWM’s information technology system and exposing the personal health information of approximately 90,000 patients.[182] During its investigation, OCR learned that UWM failed to adequately monitor the risk assessment practices of its affiliated entities. In December, UWM agreed to settle the charges for $750,000, adopt a corrective action plan, and submit annual reports on its compliance efforts.[183]

In July, St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center reached a settlement for nearly $220,000 in connection with the use of an internet-based document sharing application.[184] St. Elizabeth’s employees used the application to store documents containing personal health information for nearly 500 individuals, even though it had not analyzed the risks of such document storage. St. Elizabeth’s compounded its troubles by failing to respond and document the incident in a timely manner. St. Elizabeth’s notified OCR of a second breach less than two years later, after personal health information was left unsecured on an employee’s laptop and flash drive.[185]

Together, the Triple-S, UWM, and St. Elizabeth’s settlements offer an important lesson to providers on the necessity of maintaining a robust HIPAA compliance program and conducting thorough risk analyses before sharing documents with affiliates and outside parties or through new media.

Physical security of personal health information has been a key aspect of several of OCR’s HIPAA settlements this year. Cancer Care Group, P.C. agreed to a $750,000 settlement in connection with the theft of a laptop bag from an employee’s car.[186] The theft compromised the personal health information of approximately 55,000 patients because the bag contained both the employee’s computer and unencrypted backup media. Notably, Cancer Care did not have a policy addressing the removal of media containing electronic personal health information from its facilities. OCR Director Jocelyn Samuels emphasized the importance of developing comprehensive policies and ensuring encryption of mobile devices and electronic media in announcing the settlement.[187]

The case of Lahey Hospital and Medical Center illustrates the importance of reviewing personal health information protections in place at all workstations. A laptop used in connection with a portable CT scanner was stolen overnight from an unlocked treatment room at the teaching hospital. That laptop’s hard drive contained the personal health information of nearly 600 individuals.[188] In addition to failing to safeguard the laptop, the hospital neither required entry of a unique user name to use the laptop nor adequately recorded activity on the laptop. Lahey agreed to pay $850,000 and develop a comprehensive risk management plan to resolve the alleged HIPAA violations.

OCR’s no-tolerance approach for HIPAA violations applies regardless of the size of the entity that violated patient privacy regulations. This past year, OCR hit Denver’s Cornell Prescription Pharmacy, a small, single-location pharmacy that provides in-store and prescription services, particularly for hospice care agencies, with a $125,000 fine (and a required corrective action plan) in response to HIPAA violations.[189] Cornell came to OCR’s attention after a Denver NBC news affiliate found unshredded documents in a dumpster that contained private information on approximately 1,500 patients.[190] OCR’s investigation also revealed that Cornell failed to conduct training on HIPAA or establish written privacy policies.[191]

3. 2016 Priorities

Although it conducted pilot audits regarding HIPAA compliance in 2011 and 2012, OCR has yet to launch Phase 2 of its audit program. But OCR Director Samuels announced that audits will begin anew in early 2016.[192] Director Samuels committed to that timeframe in a letter response to an HHS OIG report finding that OCR’s failure to implement a permanent audit program contributed to noncompliance with privacy standards by at least 27% of surveyed providers, and recommending rapid implementation of a full audit program.[193] Phase 2 will include both desk-reviews and on-site reviews of HIPAA compliance and will target particular (though as yet unspecified) areas of noncompliance.[194]

III. Anti-Kickback Statute Developments

The AKS prohibits companies and individuals from offering, paying, soliciting, or receiving "remuneration" to induce or reward referrals of business that will be paid for by federal health care programs, such as Medicare and Medicaid.[195] Because the government has interpreted "remuneration" expansively to include "the transferring of anything of value in any form or manner whatsoever,"[196] the AKS potentially criminalizes a broad spectrum of business activity. The stakes for compliance are particularly high, as any violation of the AKS not only may result in criminal and civil penalties for violating the AKS statute, but also the imposition of steep civil penalties and treble damages under the FCA.[197] As government agencies (and FCA whistleblowers) forge ahead with AKS-related enforcement actions, health care providers must remain attentive to the shifting regulatory landscape, and must consider available guidance when designing their compliance programs.

A. AKS-Related Case Law Developments

During 2015, the federal courts handed down several notable decisions interpreting the AKS. These cases demonstrate the courts’ evolving understanding of AKS’s scienter standard, as well as what constitutes remuneration, referrals, and inducement under the law.

1. Willfulness

In April, the Third Circuit addressed the scope of the AKS’s willfulness requirement in an unpublished decision, United States v. Goldman. There, the defendant, a geriatrician, was convicted at trial of receiving payments in exchange for referring Medicare patients to a hospice center, for which he served as medical director.[198] On appeal, the defendant argued that the jury should have been instructed that to find that he acted willfully, the jury had to find that the defendant knew of the specific provision of the statute under which he was charged and that he intended to violate it.[199] The Third Circuit disagreed, holding that because the AKS does not qualify as a "highly technical statute[] that present[s] the danger of ensnaring individuals engaged in apparently innocent conduct," the district court did not err in instructing the jury that "willfulness" merely requires that the defendant knew his conduct was unlawful and intended to do something that the law forbids.[200] The brazen nature of the defendant’s conduct may well have driven the Third Circuit’s decision; the court observed that "accepting cash and checks in exchange for referrals cannot be considered ‘apparently innocent.’"[201] Notably, the conduct at issue in the case pre-dated the PPACA amendment to the AKS, which provides: "With respect to violations of this section, a person need not have actual knowledge of this section or specific intent to commit a violation of this section."[202] The court did not address this amended statutory language, which essentially codified the holding in Goldman.

2. Remuneration

In April, the Southern District of New York held in United States v. Narco Freedom, Inc., that "remuneration" under the AKS can include the provision of low-income housing.[203] There, the court rejected the defendant’s argument that reduced-price housing does not qualify as "remuneration" because it "promotes access to care and poses a low risk of harm to patients and Federal health care programs" and thus qualifies for an exemption under an HHS OIG notice of a proposed rule change interpreting 42 U.S.C. § 1320a–7a(i)(6)(F).[204] The court concluded that the exemption in question applies only to the civil monetary penalties provisions codified at 42 U.S.C. § 1320a–7a, whereas the government brought the action at issue under the criminal AKS (42 U.S.C. § 1320a–7b).[205] According to the court, the defendant violated the AKS by providing below-market housing only to those who attended the defendant’s Medicaid-subsidized drug treatment programs, and that low-income housing counted as "remuneration" because it constituted an "in-kind benefit provided at below market value to Medicaid beneficiaries."[206] Moving forward, we will monitor how the courts square differing interpretations of the criminal AKS and closely related provisions of the civil monetary penalties law with the principle that a "single statute with civil and criminal applications receives a single interpretation."[207]

3. Referral

In United States v. Patel, decided February 2015, the Seventh Circuit adopted an expansive definition of the term "referring" under the AKS, holding that the term includes instances in which physicians certify patients for home health care services by signing Medicare forms.[208] After a bench trial, the district court found the defendant, a physician, guilty of violating the AKS by accepting cash payments in exchange for referring patients to home health care services.[209]

On appeal, the defendant argued that Congress intended the term "refer" under the AKS to pertain to those who "personally recommend to a patient that he seek care from a particular entity."[210] According to the defendant, that definition squared with the typical use of the term in the medical context.[211] Absent some proof that he specifically directed his patients to choose a particular health care provider, the defendant argued, he could not have violated the AKS.[212] But the Seventh Circuit sided with the government, reasoning that the AKS should be interpreted in light of the statute’s main purpose, which is to prevent improper financial considerations from influencing medical judgment.[213] The court thus held that "referrals" under the statute include not only doctors’ express recommendations, but also their signatures on forms certifying plans of treatment prepared by home health companies.[214]

This decision could have potentially far-reaching repercussions for physicians, as they now may be liable under the AKS even if they do not refer a patient to a specific provider.[215] At a minimum, the decision indicates that physicians are now susceptible to a broader scope of liability under the AKS.

4. Inducement

In Jones-McNamara v. Holzer Health Systems, decided in November, the Sixth Circuit adopted HHS OIG’s broad definition of the term "induce" under the AKS, holding that the term means "to lead or move by influence or persuasion."[216] The court rejected the plaintiff’s argument that she was terminated from her position as the vice president of corporate compliance in retaliation for her investigation of potential AKS violations at her company, a health care delivery system comprised of several hospitals and care facilities.[217] The court held that her investigatory activities were not protected because her belief that an AKS violation occurred was unreasonable.[218] Focusing on AKS’s inducement requirement, the court found that a patient transport company’s "’token’ gestures of good will," like a $23.50 jacket gifted to one company employee and free hotdogs and hamburgers at an annual employee event could not "plausibly . . . induce a reasonable person to prefer one provider over another."[219]

B. HHS OIG Fraud Alert on Physician Compensation Arrangements

AKS enforcement remains a high priority of HHS OIG, which has continued to issue topical alerts that provide potential guidance for AKS compliance.

In June 2015, HHS OIG issued a fraud alert relating to physician compensation arrangements, urging physicians to ensure that any compensation arrangements, such as medical directorships, "reflect fair market value for bona fide services the physicians actually provide."[220] HHS OIG also emphasized that compensation arrangements may violate the AKS "if even one purpose of the arrangement is to compensate a physician for his or her past or future referrals of Federal health care program business."[221]

As evidence of its commitment to pursuing physicians who enter into certain compensation arrangements, HHS OIG cited settlements with 12 individual physicians "who entered into questionable medical directorship and office staff arrangements."[222] According to HHS OIG, these arrangements constituted improper remuneration because they "took into account the physicians’ volume or value of referrals and did not reflect fair market value for the services to be performed, and because the physicians did not actually provide the services called for under the agreements."[223] HHS OIG alleged that some of the physicians entered into arrangements under which an affiliated health care entity paid the salaries of the physicians’ front office staff–arrangements that HHS OIG viewed as improper remuneration because they "relieved the physicians of a financial burden they otherwise would have incurred."[224]

Although the message is straightforward, the discussion of physician compensation arrangements conveys the potential breadth of impermissible remuneration under HHS OIG’s reading of the AKS.

C. HHS OIG Policy Statement on Discounted or Free Outpatient Drugs

In October 2015, HHS OIG issued a policy statement "assur[ing] hospitals that they will not be subject to . . . administrative sanctions for discounting or waiving amounts" owed by Medicare beneficiaries for self-administered drugs dispensed in outpatient settings.[225] The policy explained that "Medicare Part B generally covers care that Medicare beneficiaries receive in hospital outpatient settings such as emergency departments and observation units;"[226] however, Medicare Part B does not usually cover self-administered drugs. While Medicare Part D may cover these drugs, "most hospital pharmacies do not participate in Medicare Part D."[227] Therefore, Medicare beneficiaries often bear the burden of these costs, which are generally "much higher than [the beneficiaries] would have paid at retail pharmacies–even if those drugs are covered under their Medicare Part D plans."[228]

Hospitals that choose to provide these self-administered drugs at a discount or for free to Medicare beneficiaries will not be subject to AKS liability if they (1) uniformly apply their policies regarding discounts and waivers for non-covered self-administered drugs; (2) do not advertise or market the discounts or waivers; and (3) do not claim the discounted or waived amounts as bad debt or otherwise shift the burden of these costs to federal programs, other payers, or individuals.[229]

D. HHS OIG "Policy Reminder" on Information Blocking and the AKS

HHS OIG released a "Policy Reminder" ("Reminder") in October 2015 on how "information blocking may affect safe harbor protection under the [AKS]."[230] The Reminder addresses situations in which "a provider, such as a hospital, may seek to furnish software or information technology to an existing or potential referral source, such as a physician practice."[231]

This kind of an arrangement may implicate the AKS because the software or information technology may be considered "remuneration" intended to induce referrals.[232] HHS has sheltered certain similar arrangements from AKS liability. Indeed, under the Electronic Health Records (EHR) safe harbor, "’remuneration’ does not include nonmonetary remuneration (consisting of items and services in the form of software or information technology and training services) necessary and used predominantly to create, maintain, transmit, or receive electronic health records," so long as all of the safe harbor’s conditions are satisfied.[233]

HHS OIG’s October 2015 Reminder focused on the safe harbor condition that pertains to information blocking. Under the safe harbor, the "donor (or any person on the donor’s behalf) [may] not take any action to limit or restrict the use, compatibility, or interoperability of the items or services with other electronic prescribing or electronic health records systems (including, but not limited to, health information technology applications, products, or services)."[234] The Reminder restated HHS OIG’s stance that "donations of items or services that have limited or restricted interoperability due to action taken by the donor or by any person on the donor’s behalf" would not meet this condition and "would be suspect under the law."[235] Prohibited arrangements include those in which (1) "a donor takes an action to limit the use, communication, or interoperability of donated items or services by entering into an agreement with a recipient to preclude or inhibit any competitor from interfacing with the donated system;" and (2) "EHR [electronic health record] technology vendors agree with donors to charge high interface fees to non-recipient providers or suppliers or to competitors."[236] The Reminder also encourages the public to report instances of potentially problematic donation arrangements.[237]

E. HHS OIG Proposed Rule Relating to AKS Safe Harbors

As reported in our 2014 Year-End Update, HHS OIG published a proposed rule on October 3, 2014 that would create additional safe harbors to the AKS.[238] In an increasingly complex regulatory landscape, safe harbors offer invaluable guidance for health care providers seeking to create effective payment arrangements and service delivery methods. We noted in our 2014 Year-End Update the potential impact on and legitimization of a range of provider practices through the expansion of certain safe harbors, exclusion of those practices from the definition of "remuneration," or formal recognition of beneficial gainsharing. As of the date of this update, HHS OIG is still working to finalize the proposed rule, with no reported timeline for the final release.

In the meantime, as required by law,[239] HHS OIG put out its annual call for ideas about new safe harbors, seeking to tap the knowledge and real-world experience of industry participants.[240] Although diverse in their topics, the comments share one abiding concern: the AKS’s potential for stifling innovative service delivery methods and payment arrangements in a rapidly changing health care industry.[241]

F. HHS OIG Report on Compliance Oversight

In April 2015, HHS OIG, in collaboration with the Association of Healthcare Internal Auditors, the American Health Lawyers Association, and the Health Care Compliance Association, released a report titled "Practical Guidance for Health Care Governing Boards on Compliance Oversight."[242] After emphasizing that boards must "be fully engaged in their oversight" of their "organization’s compliance program," the report sets forth a series of "practical tips" for boards to "effectuate their oversight role."[243] For example, the report recommends that governing boards include, or periodically consult with, a regulatory, compliance, or legal professional with health care compliance expertise because doing so "sends a strong message about the organization’s commitment to compliance, provides a valuable resource to other Board members, and helps the Board better fulfill its oversight obligations."[244] The report also encourages regular reviews of high-risk areas, such as referral relationships, billing, privacy breaches, and quality of care.[245] In addition, the report notes that the board should ensure that it receives certain types of "compliance-related information from various members of management."[246] In addition, the report recommends self-disclosing identified issues through HHS OIG’s Self-Disclosure Protocol, on the basis that doing so may expedite resolution of the case, "lower [damages] payment[s]," and facilitate an "exclusion release" without a CIA or other compliance obligations.[247] Although the report acknowledges that the size and structure of organizations’ compliance functions may vary, the report underscores HHS OIG’s position that an organization’s compliance department and legal department should be separate and independent.[248]

G. Notable Settlements

In 2015, the DOJ entered into several multi-million dollar AKS-related settlements with health care providers.

In October 2015, the DOJ announced a $9.25 million settlement with PharMerica Corporation ("PharMerica"), the nation’s second largest provider of pharmaceutical services to nursing homes, to settle allegations that the company solicited and received kickbacks from pharmaceutical manufacturer Abbott Laboratories ("Abbott") in exchange for recommending that physicians prescribe Abbott’s anti-epileptic drug Depakote to nursing home patients.[249] According to the government, the alleged kickbacks from Abbott were disguised as rebates, educational grants, and other financial support.[250] This settlement is notable because the DOJ entered into a $1.5 billion settlement with Abbott in May 2012 for, amongst other conduct, allegedly providing kickbacks to nursing home pharmacies, including PharMerica.[251]

Also in October 2015, Millennium Health ("Millennium"), one of the largest urine drug testing laboratories in the United States, agreed to pay $256 million to resolve allegations of FCA and AKS violations, including allegations that the company provided free items to physicians who agreed to refer expensive laboratory testing business to the company.[252] The company allegedly offered free point-of-care urine drug test cups to physicians in exchange for the physicians’ agreement to return the urine specimens to Millennium for hundreds of dollars’ worth of additional testing.[253] As part of the settlement, Millennium entered into a five-year CIA with HHS OIG, which requires the company to make significant changes to its board of directors, among other prospective obligations.[254]

IV. Stark Law Developments

Beyond the DOJ resolutions of cases discussed in Part I above, 2015 saw several significant developments regarding the federal self-referral law (i.e., the Stark Law). Earlier this past year, we saw proposed legislation aimed at simplifying the law’s penalties and clarifying its scope. More recently, CMS published changes in the Stark Law regulations, creating two new exceptions and clarifying multiple provisions. In addition, two federal circuit courts issued decisions that may affect future Stark Law enforcement actions.

A. Proposed Legislation

1. Stark Administration Simplification Act of 2015, H.R. 776