February 15, 2017

Just days into the new administration’s regime, the U.S. health care sector is at the forefront of the President’s and Congress’s attention. Repeal and, perhaps, replacement of the Affordable Care Act ("ACA"), a much-debated Republican stalking horse for more than half a decade, could now be near at hand. Legislative and executive action on this front is likely to dominate discussion in 2017, but what that means for U.S. health care providers, particularly in the regulatory and enforcement areas unrelated to the more controversial exchanges and individual and employer mandates, remains to be seen.

As we await further signs regarding the fate of the ACA and the scope of any successor legislation, we will focus here on health care fraud and abuse enforcement activity during the final year of the Obama administration. It will come as no surprise to practitioners in the health care fraud and abuse field and participants in the health care industry that the administration did not go out quietly. Both the U.S. Department of Justice ("DOJ") and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services ("HHS") pursued wide-ranging and robust enforcement agendas in 2016, resulting in significant recoveries under the False Claims Act ("FCA"), a steady stream of criminal health care fraud actions, and amplified civil monetary penalties and administrative exclusions.

In keeping with the structure of our 2015 Year-End Health Care Compliance and Enforcement Update – Providers ("2015 Year-End Update"), we address below regulatory and enforcement developments that affected health care providers during the past year. This update begins by addressing DOJ enforcement activity targeting health care providers, activity which–as in years past–centered on civil and criminal FCA investigations, resolutions, and cases. We then turn to noteworthy HHS enforcement matters, Anti-Kickback Statute ("AKS") developments, and Stark Law activity from 2016. Finally, we address significant government health program payment and reimbursement issues from the past year. A collection of Gibson Dunn’s recent publications on enforcement and regulatory issues confronting health care providers, as well as a link to our recent webcast, Hot Topics in Fraud and Abuse Enforcement Involving Health Care Providers, may be found on our website.

I. DOJ Enforcement Activity

A. False Claims Act Enforcement Activity

DOJ enforcement efforts in the second half of 2016 allowed President Obama’s administration to close out the year with 106 announced settlements against health care providers, resulting in recoveries of approximately $1.14 billion. In terms of both overall numbers and dollar value, the past year’s settlements were significantly lower than those in 2015, which saw 195 settlements and recoveries of nearly $2 billion.

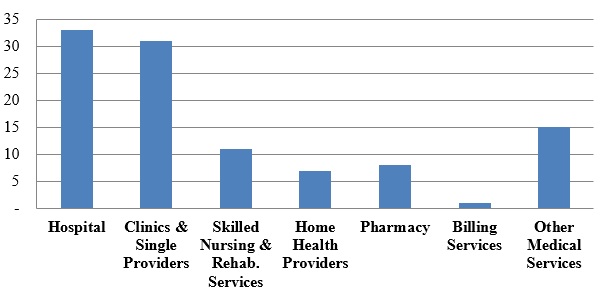

The 2016 calendar-year settlements spanned a range of provider types and legal theories, as the charts below illustrate.

Number of FCA Settlements with Providers, by Provider Type:

As usual, hospitals, clinics, and single providers represented the largest proportion of provider settlements (more than sixty percent of the 106 resolutions). Hospitals entered into thirty-three settlements with the DOJ in 2016, while clinics and single providers agreed to thirty-one settlements. This fairly even split contrasts with 2015, when settlements with hospitals far outpaced settlements with clinics and single providers (121 to twenty-seven), as a result of a nationwide investigation that ensnared a large number of hospitals (as reported on in both our 2015 Year-End and 2016 Mid-Year Health Care Compliance and Enforcement Update – Providers ("2016 Mid-Year Update")). Absent a large-scale sweep (like that in 2015), the DOJ typically resolves a similar number of matters each year with hospitals, on the one hand, and clinics and single providers, on the other.

In 2016, the DOJ recovered almost $492 million from hospitals, compared to the approximately $93 million collected from smaller clinics and single providers. Skilled nursing and rehabilitation services providers were responsible for a higher portion of the total dollars recovered ($318 million) than the relatively low number of settlements (eleven) might have suggested.

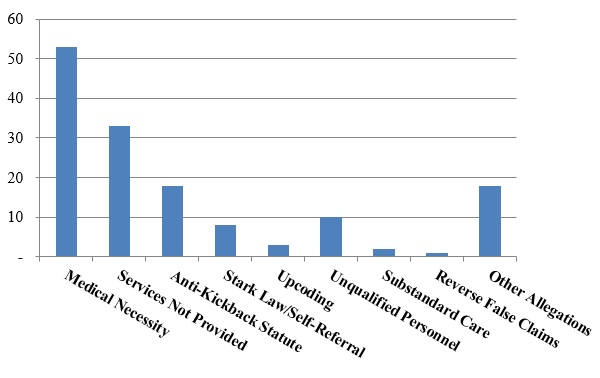

Number of FCA Settlements with Providers, by Allegation Type:

Not surprisingly, allegations relating to medical necessity far outpaced other theories of liability. What is more interesting is the significant number of settlements based on allegations that services were never provided–in the prior two years, this theory has provided the basis for fewer settlements than both the AKS and the Stark Law. Yet, in 2016, services-not-provided settlements accounted for more total settlements than alleged AKS and Stark Law violations combined.

Nevertheless, the AKS featured in the largest FCA settlement involving a provider in 2016. On September 30, 2016, Tenet Healthcare Corporation and certain of its subsidiaries entered into a civil Settlement Agreement with the United States and others to resolve allegations that four hospitals located in the southeastern United States entered into referral source arrangements in violation of various federal and state laws, including federal and state anti-kickback statutes and false claims acts.[1] Under the Settlement Agreement, Tenet agreed to pay $368 million, plus interest, to the United States, the State of Georgia, and the State of South Carolina.[2] A Tenet subsidiary simultaneously entered into a Non-Prosecution Agreement with the DOJ’s Criminal Division and the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Northern District of Georgia; the Agreement, inter alia, requires Tenet to retain an independent compliance monitor to assess, oversee, and monitor Tenet’s compliance with the terms of the Agreement.[3] As contemplated by the Settlement Agreement, the DOJ also filed a criminal Information against two Tenet subsidiaries, alleging that each entity conspired to violate the AKS and defraud the United States.[4] The two entities entered into Plea Agreements, under which they agreed to plead guilty and to pay forfeiture money judgments totaling approximately $146 million.[5]

The second largest provider settlement in 2016 involved Life Care Centers of America, an operator of skilled nursing facilities, and its owner, Forrest Preston. The settlement resolved allegations that Life Care systematically billed Medicare and TRICARE for rehabilitation therapy services that exceeded the level of care beneficiaries actually required. In particular, the government alleged that Life Care adopted policies and practices to place as many patients as possible in the group that receives the highest level of rehab therapy reimbursed by Medicare Part A. Under the terms of the settlement, Life Care and Preston agreed to pay the government $145 million; two former Life Care employees, who brought suit under the FCA’s qui tam provisions, received nearly $30 million of that sum.[6]

The Life Care settlement first made headlines–including in our 2014 Year-End Health Care Compliance and Enforcement Update – Providers ("2014 Year-End Update") –when the district court decided to permit the government to rely on statistical sampling and extrapolation to support FCA liability.[7] That decision, coupled with another decision issued the same day denying Life Care’s motion to exclude as unreliable the testimony of the government’s sampling expert,[8] allowed the government to extrapolate from a relatively small set of claims–just 400 total–to the entire universe of Medicare claims submitted by LifeCare, a whopping 54,396 potentially at-issue claims. The case is a sobering reminder of the potentially expansive liability in nationwide cases against providers, especially in light of the FCA’s per-claim penalties and treble damages.

The Life Care settlement is also noteworthy as an illustration of the government’s application of the principles of individual accountability set out in the Yates Memorandum, which was issued in September 2015.[9] Before the Yates Memorandum, relators and the government generally focused their attention, at least in civil cases, on corporations rather than individuals (based in part on companies’ greater ability to pay settlements). This pre-Yates Memorandum practice was evident in the management of the Life Care litigation at its earliest stages: although relators originally named several individuals (including Preston) as defendants, they were voluntarily dismissed from the litigation in October 2014.[10]

Post-Yates, however, the government changed course by bringing a separate civil action against Preston.[11] The government’s complaint against Preston was filed just seven months after the Yates Memorandum (and six months before the settlement was announced). The inclusion of Preston in the settlement gives at least the appearance of individual accountability, by holding Preston and Life Care jointly liable for the full settlement amount.[12] Although insurance coverage and director indemnification policies may well ensure that Preston does not suffer any direct financial losses, the collateral consequences–including reputational harm–may well satisfy the government’s expectations regarding individual accountability in the civil context.

B. FCA-Related Case Law Developments

1. Statistical Sampling

As reported in our 2016 Mid-Year Update, the first half of 2016 saw some developments–particularly at the district court level–regarding the use of statistical sampling to establish liability in FCA cases. In these cases, plaintiffs and/or the government have attempted to establish that a certain number of claims in a much larger universe were "false" for purposes of FCA liability based on a review of only a sample of the claims. Generally, district courts have declined to hold that statistical evidence is, per se and as a matter of law, inadmissible to establish the falsity of claims subject to direct review (although courts have been careful to note that other evidentiary issues evaluated on a case-by-case basis may preclude the use of sampling to establish liability in some circumstances). To date, no appellate court has weighed in on this issue in the FCA context.

Defendants continue to oppose the practice of extrapolating falsity from both an evidentiary and a legal perspective. For example, Prime Healthcare filed a motion on September 1, 2016, in the Central District of California to exclude, as a matter of law, statistical sampling to establish falsity under the FCA.[13] In that case, the government has alleged that there are more than 35,000 claims potentially at issue. Prime Healthcare filed its motion to exclude even before it had answered the government’s intervened complaint. But the court declined to consider the issue given the early stage of the litigation; indeed, as of the time of Prime Healthcare’s motion, neither the government nor relator had filed any report suggesting the use of statistical sampling to establish falsity.[14] The court recognized, however, that at some point it would likely be called upon to address the question: under the court’s order, Prime Healthcare is free to renew its motion "[i]f the government attempts to introduce sampling evidence" at any point in the litigation.[15]

As noted above, the federal courts of appeals have yet to address the use of sampling to establish liability in FCA cases. Two closely watched cases–United States ex rel. Michaels v. Agape Senior Community, Inc. and United States ex rel. Paradies v. AseraCare, Inc.–were billed as the first cases in which an appellate court might weigh in on these important issues. During oral argument in Agape, however, the Fourth Circuit panel signaled that it was not inclined to reach the merits of the statistical sampling question. The panel has not decided the case, and may ultimately reach the question despite its suggestions to the contrary during oral argument. As to AseraCare, the issue on appeal to the Eleventh Circuit focuses on the district court’s decision to vacate a jury’s finding of liability after trial and to grant summary judgment in favor of AseraCare based on the court’s view that a mere difference of medical opinion is insufficient to support FCA liability. The propriety of the district court’s earlier decision to permit statistical sampling is not squarely presented in AseraCare (at least not yet). Thus, it may be some time before the appellate courts actually weigh in on, and bring clarity to, this closely watched and heavily litigated issue.

2. The Supreme Court’s Escobar Decision

This past year was notable not only because of blockbuster settlements, but also because of critical developments in FCA jurisprudence. As we reported in our 2016 Mid-Year Update, the Supreme Court’s landmark Escobar decision reframes key questions that arise in many FCA cases against health care providers. Although the Court affirmed the viability of the "implied false certification" theory of liability under certain circumstances, the Court also recast the falsity analysis in common-law terms and sharpened the FCA’s "demanding" materiality standard. For complete coverage of post-Escobar developments, please refer to our 2016 Year-End False Claims Act Update.

Of course, Escobar involved a health care provider, and it will come as no surprise to those who followed the case that it will alter the contours of cases that the government and relators can pursue against providers in the future. Since the Supreme Court decided Escobar in June 2016, FCA defendants have invoked Escobar to attempt to scale back the scope of FCA liability. In the first set of district court–and, to a lesser extent, appellate court–decisions applying Escobar, two key issues regarding the meaning of Escobar have been the focus: (1) the extent to which a plaintiff must identify specific representations in a claim for payment that are rendered false or misleading to support an "implied false certification" theory of liability; and (2) the proper application of the FCA’s materiality element, as clarified by Escobar.

a) Defining the Boundaries of an "Implied False Certification" Claim

The Supreme Court stated in Escobar that "the implied certification theory can be a basis for [FCA] liability, at least where two conditions" are met: (1) "the claim does not merely request payment, but also makes specific representations about the goods or services provided"; and (2) "the defendant’s failure to disclose noncompliance with material statutory, regulatory, or contractual requirements makes those representations misleading half-truths."[16] In reaching that conclusion, the Court explained that the phrase "false or fraudulent" under the FCA should be interpreted in accordance with the meaning of those terms at common law.[17]

Since Escobar, the lower courts have reached different conclusions as to the precise requirements for showing liability based on an implied certification. A number of courts have taken Escobar at face value, requiring the FCA plaintiff to show both of Escobar‘s conditions, including that the defendant made "specific" misleading representations about the goods or services provided to be liable based on an implied certification theory.[18] One of these courts observed that imposing liability in the absence of a sufficiently "specific" misrepresentation about the goods or services provided "would result in an ‘extraordinarily expansive view of liability’ under the FCA, a view that the Supreme Court rejected in Escobar."[19]

But some courts have asserted that they are not bound by Escobar‘s "specific representation" requirement. For example, in Rose v. Stephens Institute, the Northern District of California rejected the argument "that Escobar establishes a rigid" test for falsity "that applies to every single implied false certification claim."[20] Reasoning that the Supreme Court left the door open by limiting its holding to "at least" the circumstances before it in Escobar and by expressly declining to "resolve whether all claims for payment implicitly represent that the billing party is legally entitled to payment," the court held that a relator can state an implied false certification claim without necessarily identifying a "specific" representation that was a "misleading half-truth" in any claim.[21]

In United States ex rel. Brown v. Celgene Corp., one of the first cases against a pharmaceutical or device company to test this theory, the Central District of California followed Rose and held that a relator’s implied false certification allegations against the pharmaceutical company Celgene Corp.–based on off-label promotion and alleged kickbacks–could survive despite the fact that the relator failed to identify any "specific misrepresentation" made in a claim for payment.[22]

Federal appellate courts have not yet had the opportunity to fully develop their take on the scope of Escobar‘s "two conditions," including whether a "specific representation" is required. The Seventh Circuit has recently signaled that it will enforce a strict reading of Escobar‘s requirements. In United States v. Sanford-Brown Ltd., for example, the Seventh Circuit affirmed summary judgment in favor of a defendant where the relator offered no evidence that the defendant had made "any representations at all," explaining that "bare speculation that [a defendant] made misleading representations is insufficient."[23] Other federal appellate courts are likely to begin to address the "two conditions" in 2017. Indeed, the Rose court subsequently certified its decision embracing a less restrictive reading for interlocutory appeal to the Ninth Circuit.[24] And in United States ex rel. Panarello v. Kaplan Early Learning Co., a magistrate judge in the Western District of New York similarly declined to require an FCA plaintiff to show "specific representations," but recommended that the question be certified for interlocutory appeal to the Second Circuit.[25] As appellate courts take their turns at addressing this issue, we will watch carefully for any emerging circuit split that could send this issue back to the Supreme Court sooner rather than later.

b) Application of Escobar‘s "Demanding" Materiality Standard

In Escobar, the Supreme Court not only specified the requirements for the implied false certification theory, but also reframed the FCA’s materiality standard as a question of whether a violation of the specific statute, regulation, or requirement at issue would actually have affected the government’s decision to pay for a claim had the government known of the alleged noncompliance.[26] In so doing, the Court made clear that materiality does not exist merely because the government may have the option not to pay a claim due to the alleged wrongdoing. The Court also explained that whether the particular statutory, regulatory, or contractual requirement at issue is specifically labeled a condition of payment remains relevant to materiality, but it is not dispositive.[27] The Court also stated that the FCA’s materiality requirement, which is an important bulwark against plaintiffs looking to bootstrap garden-variety regulatory violations or breach of contract claims into FCA liability, is "demanding" and "rigorous"–and that courts must ensure FCA plaintiffs satisfy this "rigorous" requirement by pleading facts showing materiality "with plausibility and particularity under Federal Rules of Civil Procedure 8 and 9(b)."[28]

Since Escobar, several courts have seized on the Court’s command to rigorously review a complaint’s materiality allegations at the motion to dismiss stage–and have demanded that complaints include plausible, more-than-conclusory allegations showing that (1) the government either actually does not pay claims involving violations of the statute, rule, or regulation at issue, or (2) the government was unaware of the violation but "would not have paid" the claims at issue "had it known of" the alleged violations.[29]

In Sanford-Brown, one of the first appellate court decisions on the issue, the Seventh Circuit held that a relator must provide "evidence that the government’s decision to pay" a claim "would likely or actually have been different had it known of [the defendant’s] alleged noncompliance" with the statute, rule, or regulation at issue.[30] The court affirmed summary judgment for the defendant, concluding the alleged noncompliance was not material to the government’s decision to pay claims because the government had "already examined" the defendant "multiple times over and concluded that neither administrative penalties nor termination was warranted."[31] Similarly, in United States ex rel. D’Agostino v. ev3, Inc., which is discussed in further detail below, the First Circuit concluded that allegations that a defendant’s misconduct–i.e., misstatements to FDA during the drug approval process–"could have" influenced "FDA to grant approval" failed to satisfy the "demanding" materiality standard set by Escobar.[32] In holding the relator had not adequately alleged materiality, the First Circuit also relied on the fact that the government neither "denied reimbursement" for the claims at issue nor took any other regulatory actions despite having been made aware of the allegations of the defendant’s fraudulent conduct six years earlier.[33]

In line with Escobar’s statement that identifying a provision as a condition of payment is "not automatically dispositive" of materiality,[34] some courts have also dismissed complaints that merely allege payment "was conditioned on the claim being compliant" with the allegedly violated laws.[35] Similarly, nakedly alleging that the government "has a practice of not paying claims" involving the alleged violations is not enough to survive the rigorous pleading requirements reiterated in Escobar, especially when the government has actually paid claims after learning of the alleged violations.[36]

C. Criminal Prosecutions

As reported in our 2016 Mid-Year Update, two major, record-breaking criminal investigations marked the first six months of 2016. In one, the DOJ brought charges against 301 individuals in a civil and criminal takedown of unprecedented scope, which was coordinated by the Medicare Fraud Strike Force.[37] The other record-breaking investigation involved only three individuals, but a remarkable $1 billion of allegedly fraudulent claims. According to the government, that alleged fraud and money laundering scheme centered around the provision of medically unnecessary services at skilled nursing and assisted living facilities and the payment of kickbacks.[38]

The DOJ continued its routine enforcement efforts against individuals involved in relatively small-scale schemes to defraud the federal health care program (particularly in the home health care space). For example, the administrator of five home health agencies in the Houston, Texas area pleaded guilty for her role in a fraud scheme in which she and her co-conspirators allegedly paid illegal kickbacks for patient referrals for services that were not medically necessary and/or never were provided.[39] The scheme cost the agencies almost $8 million in purported fraudulent payments.[40] An administrator of a Miami-based home health agency was convicted after a jury trial for a similar scheme that resulted in $2.5 million in allegedly fraudulent reimbursements.[41] These cases, and others like them, illustrate the DOJ’s commitment to combatting fraud schemes both large and small and the concentration of resources in areas that historically have proven to be particularly susceptible to fraudulent activity.

Although it is difficult to predict the enforcement priorities of the next presidential administration, recent DOJ leaders have signaled that the criminal toolkit will be brought to bear as appropriate in an increasing number of corporate health care fraud investigations.

II. HHS Enforcement Activity

A. HHS OIG Activity

1. 2016 Developments and Trends

As we predicted in our 2016 Mid-Year Update, HHS OIG’s $5.66 billion in expected recoveries from its investigative and audit enforcement efforts in 2016 far surpassed the agency’s abnormally low recoveries in 2015.[42] (In 2015, HHS OIG expected to recover only $3.35 billion, far lower than the more than $5 billion in expected recoveries in each of the prior two years.[43]) Expected recoveries, as reported by HHS OIG, consist of audit receivables (representing amounts identified in OIG audits that HHS officials have determined should not be charged to the government) and investigative receivables (consisting of expected criminal penalties, civil or administrative judgments, or settlements that have been ordered or agreed upon).[44] HHS OIG’s improved performance in Fiscal Year 2016 was driven by investigative receivables of $4.46 billion, which is more in line with prior years than with the slower Fiscal Year 2015.[45]

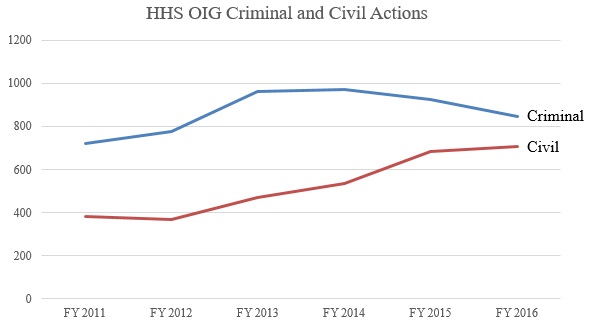

Despite the jump in the dollar value of recoveries, total enforcement activity in 2016 changed little from 2015, with 844 criminal actions and 708 civil actions initiated. These figures are considerably higher than the enforcement activity figures as recently as five years ago, due to a sustained, relatively significant increase during President Obama’s second term.[46] The initial increase in total enforcement activity from 2012 to 2015 was driven in large part by an increase in both criminal and, even more so, civil enforcement activity. Between 2015 and 2016, criminal enforcement efforts leveled off (and decreased slightly), whereas civil enforcement efforts have continued to increase (albeit at a slower rate). The increased activity, particularly in civil actions, may reflect the work of the new HHS OIG affirmative litigation team first announced in 2015. The result of these trends in HHS OIG enforcement action is that, today, HHS OIG plays a much more active role in enforcement, and the agency is increasingly reliant on its civil enforcement toolkit.

2. Proposed Rule Amending Regulation Governing State Medicaid Fraud Control Units

In September 2016, CMS and HHS OIG announced a proposed rule amending the regulation governing State Medicaid Fraud Control Units ("MFCUs"), which was first adopted in 1978 and had been amended only twice since then.[47] Much has changed in that time, and the proposed rule largely plays catch-up with changes in both policy and practices over the past four decades.

Perhaps the most significant development reflected in the proposed rule are certain measures designed to ensure that MFCUs work more closely with their federal counterparts. For example, the proposed rule would require MFCUs to submit information regarding convictions they obtain to OIG within thirty days of sentencing, so that OIG can pursue program suspension and/or exclusion as appropriate.[48] The proposed rule also includes a requirement that MFCUs coordinate with federal investigators and prosecutors on overlapping matters.[49]

The proposed rule also:

- incorporates statutory changes, such as raising the federal matching rate for operating costs from fifty percent to seventy-five percent, allowing the MFCUs to seek approval from the Inspector General of the relevant agency (usually HHS) to prosecute violations of state law related to fraud (as long as the fraud is primarily related to Medicaid), and giving the MFCUs the option to investigate and prosecute patient abuse or neglect in board and care facilities, regardless of whether the facilities receive Medicaid payments;[50]

- provides additional guidance to MFCUs on administrative matters such as staffing of the MFCUs and the annual recertification process with OIG;[51] and

- adds definitions for several terms, including "fraud," "abuse of patients," "neglect of patients," ”misappropriation of patient funds," and "program abuse."[52]

The definition of "fraud" is intended to clarify that the term encompasses both criminal and civil actions.[53] Although MFCUs have long spent much of their resources pursuing civil actions under existing regulations, their mission was historically defined as the investigation and prosecution of criminal violations. The revised definitions reflect the observation that federal and state health care prosecutors commonly use both criminal and civil remedies to resolve provider fraud cases.[54]

The proposed rule also broadens the definition of "provider" to include individuals or entities that are "required to enroll in a State Medicaid program, such as ordering or referring physicians."[55] This modified definition seeks to underscore "that providers who are not furnishing items or services for which payment is claimed under Medicaid can be the subject of a MFCU investigation and prosecution."[56]

In general, the changes reflected in the proposed rule expand the investigative and prosecutorial authority and the responsibilities of MFCUs (at least as compared to the authority and responsibilities described in the current version of the regulations). Notably, many of the proposed changes actually reflect current policies and practices, and thus the regulation, if adopted, may serve only to formalize current practices rather than drive future changes.

Many stakeholders submitted comments on the proposed rule by the November 21, 2016 deadline. We will monitor the agency’s response to those comments and the impact they may have on any final rulemaking.

3. Notable Reports and Reviews

HHS OIG’s public reports in 2016 included its annual review of MFCU activity for the prior fiscal year.[57] In 2015, MFCUs reported 1,553 convictions and 731 civil settlements and judgments, totaling $744 million in criminal and civil recoveries.[58] These numbers represent an increase in convictions but a decrease in civil resolutions compared to prior years, in contrast to the shift toward civil resolutions at the federal level.[59] HHS OIG exclusions based on MFCU referrals have increased over time, with more than 1,300 each in Fiscal Years 2014 and 2015, compared to 1,022 in 2013 and fewer than 750 per year in 2011 and 2012.[60] Although the MFCUs did produce more criminal convictions in Fiscal Year 2015 than they had in prior years, the increase in the number of exclusions since 2011 has been far more dramatic, suggesting that it may be driven by HHS OIG’s push for improvements in the reporting of convictions by the MFCUs to their federal counterparts.[61] The Texas MFCU was particularly successful in 2015, accounting for more than a quarter of the Fiscal Year 2015 recoveries, thanks to the completion of several large, multi-defendant investigations that resulted in significant recoveries.[62] Other states with relatively active and productive MFCUs included California, Florida, New York, Tennessee, and Wisconsin.[63]

In June 2016, HHS OIG completed a review of home health fraud cases, which have been a focal point for enforcement for both HHS OIG and the DOJ (as noted above in Section I.C).[64] According to HHS OIG’s report, common characteristics among OIG-investigated cases of home health fraud include: high percentages of episodes for which the beneficiary had no recent visits with supervising physicians that were not preceded by a hospital or nursing home stay (or where the beneficiary’s primary diagnosis is diabetes or hypertension); and high percentages of beneficiaries with claims from multiple HHAs or with multiple home health readmissions in a short period of time.[65] HHS OIG has identified more than 500 home health agencies and 4,500 physicians as outliers with respect to these characteristics, and expects to apply greater scrutiny to these outliers. This represents yet another example of using statistical tools to drive enforcement decisions. HHS OIG also used this process to identify twenty-seven "hotspots" in twelve states, many in areas that HHS OIG already considers to have high rates of Medicaid fraud.[66]

These reports did not quite complete the agency’s work plan for 2016; indeed, HHS OIG did not publish several reports that it had identified as forthcoming as of the time of our 2016 Mid-Year Update. Those reports–which include an analysis of outlier payments relating to outpatient short stay claims, payment credits related to the replacement of implanted medical devices, and the validation of hospital-submitted quality data–have been re-listed as goals for 2017.[67]

HHS OIG’s 2017 plan also includes some noteworthy new goals. For example, HHS OIG intends to conduct several reviews relating to skilled nursing facilities (on the heels of its extensive review of home health agencies), including an analysis of unreported incidents of abuse and neglect, a review of reimbursements focusing on whether facilities bill for higher levels of care than are provided or necessary, and an evaluation of whether state agencies respond properly to complaints.[68] HHS OIG also expects to assess the effect of the CMS "two-midnight" rule.[69]

4. Significant HHS OIG Enforcement Activity

As noted above, HHS OIG invoked its enforcement authority aggressively in 2016, particularly in the area of Civil Monetary Penalties ("CMPs"). The agency’s focus remained, as in years past, on instances of false and fraudulent billing, as well as home health agencies and emergency ambulance services.

a) Exclusions

Perhaps the most powerful tool in HHS OIG’s enforcement toolkit is its ability (and, in some cases, its obligation) to exclude entities and individuals from participation in federal health care programs,[70] which can have a devastating impact on a provider’s bottom line.

After record-setting 2014 and 2015–in which HHS OIG excluded 4,017 and 4,112 entities and individuals, respectively, from government health care programs[71]–HHS OIG reported that it excluded 3,635 entities and individuals in Fiscal Year 2016.[72] The exclusions in calendar year 2016 include forty-one entities, which included eight home health agencies, five clinics, four transportation/ambulance companies, and four pharmacies.[73] Of the individuals placed on the exclusion list in the calendar year, 285 were identified as business owners or executives.[74] Fifty-four of the excluded executives operated home health agencies and an additional twenty-four executives operated transportation or ambulance companies.[75]

b) Civil Monetary Penalties

In the 2016 calendar year, HHS OIG announced 169 CMPs, which resulted from settlement agreements and self-disclosures, and recovered approximately $52 million.[76] As noted in our 2016 Mid-Year Update, HHS OIG’s increased pursuit of CMPs is likely attributable to the work of HHS OIG’s new litigation team. In keeping with past years, HHS OIG primarily pursued CMPs for false or fraudulent billing and for the employment of individuals who entities knew or should have known were excluded from health care programs. These cases account for seventy and fifty-six, respectively, of the total number of CMPs assessed in 2016.[77] Additional penalties were assessed for violations of the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act ("EMTALA"), violations of AKS and Stark Law physician self-referral prohibitions, drug price reporting requirements, and the improper submission of claims for emergency ambulance transportation.[78]

The largest penalties in 2016 have come in self-disclosure cases. For example, the $8.6 million figure paid by Lancaster Healthcare Center in June 2016, summarized in the 2016 Mid-Year Update, is by far the largest CMP assessed in 2016. Other notable CMPs assessed in the second half of 2016 are summarized below:

- Memorial Hermann Health System: After self-disclosing issues to HHS OIG, Memorial Hermann agreed to pay more than $5.6 million to resolve claims that it improperly billed federal health care programs for certain outpatient services that automatically appended modifier 59 (for distinct or independent procedures or services provided to the same patient on the same day) or modifier 91 (repeat diagnostic laboratory test) to Current Procedural Terminology codes. This CMP was the second largest of 2016.[79]

- Stony Brook University Hospital: Like Memorial Hermann, Stony Brook self-disclosed conduct and then agreed to pay more than $3.2 million to resolve allegations that it failed to timely obtain re-certifications of medical necessity for inpatient psychiatric services provided to Medicare Part A beneficiaries. HHS OIG also alleged that the hospital did not properly code daily activities in its Medicaid-qualified Continuing Day Treatment Program, resulting in Medicare Part B reimbursement for non-covered services to dual-eligible beneficiaries.[80]

- University of California San Francisco Health (d/b/a UCSF Medical Center): UCSF Health also self-disclosed issues to HHS OIG; thereafter, it entered into a $1.4 million settlement to resolve allegations that it submitted claims for "new patient" evaluation and management outpatient clinic visits even though the patients at issue were actually "established patients" (and thus UCSF was only entitled to use a lower-paying Healthcare Common Procedure System code).[81]

- Cheshire Medical Center and Dartmouth-Hitchcock Clinic: CMC and DHC also entered into a $1.4 million settlement after they self-disclosed certain conduct. HHS OIG alleged that CMC and DHC submitted claims to Medicare for services that were not performed as billed and/or were not medically necessary.[82]

c) Corporate Integrity Agreements

HHS OIG employs corporate integrity agreements ("CIAs") in an effort to ensure that providers comply with Medicare and Medicaid rules and regulations. After a robust 2015, which saw forty-seven CIAs take effect, 2016 saw a slight decline with a total of thirty-seven.[83] CIAs are often linked with other enforcement penalties. For example, a skilled nursing services company, the chairman of its board, and the senior vice president of reimbursement analysis settled civil claims that they allegedly violated the FCA. The government’s allegations involved the purported submission of false or medically unnecessary services. The settlement provided for payments of $28.5 million from the company, $1 million from the board chairman, and $500,000 from the senior vice president. The settlement further provided for the company to enter into a CIA.[84] In another DOJ settlement involving allegations of medically unnecessary services, Vibra Healthcare agreed to pay $33 million and enter a five-year CIA.[85] Finally, Lexington Medical Center, a South Carolina hospital, agreed to a $17 million settlement and a five-year CIA for violations of the Stark Law and FCA with regard to physician employment agreements and practice acquisitions; its CIA calls for the appointment of a compliance officer, creation of a compliance committee, and oversight of compliance by the hospital’s board of directors.[86]

Although not yet finalized, Mylan Inc. announced on October 7, 2016 that it agreed to enter into a $465 million settlement with the DOJ and expects to enter into a CIA with HHS OIG. The settlement follows the DOJ’s investigation into the company’s classification of the allergy treatment EpiPen as a generic drug for purposes of the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program.[87]

To underscore that CIAs have teeth, HHS OIG continues to pursue entities that violate the terms of their CIAs. For example, in September 2016, Kindred Healthcare paid a $3 million penalty–the largest penalty to date–for violating the terms of its CIA by using improper billing practices a year before its five-year agreement was set to expire.[88]

d) HHS Guidance for Independent Review Organizations

Health care provider CIAs often call for independent review organizations ("IROs"), which typically handle claim reviews or cost report reviews during the CIA period, to certify their independence and objectivity in connection with the review. Although IROs are engaged by the provider subject to the CIA, HHS OIG typically has the power to reject IROs that lack either independence or the necessary qualifications.

In August 2016, HHS OIG released new independence and objectivity guidelines for IROs; HHS OIG’s prior guidance on the subject dates back to 2010 and, before that, 2004.[89] The new guidelines are intended to reflect the Government Accountability Office’s current auditing standards, which are referred to as the "Yellow Book" and were most recently revised in 2011. Although HHS OIG’s guidance essentially confirms existing views regarding independence and objectivity, these guidelines crystallize those views.

HHS OIG’s guidance tracks the Yellow Book’s definition of objectivity, which includes "independence of mind and appearance when providing audits, maintaining an attitude of impartiality, having intellectual honesty, and being free of conflicts of interest."[90] According to the guidance, independence of mind and appearance requires that IROs impartially judge all issues relating to the CIA review. The two categories identified as threats to independence are instructive. The first identified threat to independence–the "self-review threat"–is the threat that an auditor that has previously provided nonaudit services to the audited organization will not be able to appropriately (i.e., independently) evaluate the results of judgments made or services performed as part of those nonaudit services. The second identified threat is the "management participation threat," which is defined as the threat that results from an auditor taking on the role of management or otherwise performing management functions on behalf of the entity undergoing the audit.[91]

The agency also incorporated into the new guidance the Yellow Book standards on professional judgment and competence, providing that auditors should use professional judgment in all aspects of their responsibilities, including following the independence standards and related conceptual framework; maintaining objectivity and credibility; assigning competent staff to the audit; defining the scope of work; evaluating, documenting, and reporting the results of the work; and maintaining appropriate quality control over the audit process.[92]

B. CMS Activity

In 2016, CMS continued to pursue quality-of-care initiatives and address payment processing challenges, described in Section V. CMS also persisted in its anti-fraud efforts. For example, the proposed rule regarding MFCUs discussed above in Section II.A.2 was a joint effort between CMS and HHS OIG. And–as reported in our 2016 Mid-Year Update–CMS proposed (but has not yet finalized) a rule intended to enhance fraud controls associated with the provider enrollment process.

Recent developments in CMS’s program safeguard activities and other anti-fraud initiatives are described below.

1. Transparency and Data Accessibility

Access to data has been a focus for CMS for the past few years, and 2016 was no different.

In January 2016, CMS proposed rules that would broaden the "qualified entity program" created by the ACA to enable certain entities to sell nonpublic analyses using Medicare data to providers or others who might use the analyses to improve care.[93] CMS promulgated a final rule (similar, though not identical, to the proposed rule) in July 2016.[94] CMS currently has certified sixteen entities as eligible to participate in the qualified entity program.[95] In its press release announcing the final rule, CMS noted that future rulemaking is expected to "expand the data available to qualified entities to include standardized extracts of Medicaid data."[96]

CMS also continued to release and expand its library of already extensive data sets, including:

- An "Open Payments" searchable dataset of more than eleven million records from 2015, accounting for more than $7 billion in payments;[97]

- Updated datasets in Hospital Compare, a tool created to enable consumers to compare providers on more than 100 quality metrics;[98]

- The Skilled Nursing Facility Utilization and Payment Public Use File, a newly available set of data that includes 2013 claims information from more than 15,000 skilled nursing facilities, accounting for $27 billion in Medicare payments;[99]

- A second release of prescription drug cost data relating to Medicare Part D, which covers calendar year 2014 and includes data from more than one million providers accounting for approximately $121 billion in payments;[100]

- The Hospice Utilization and Payment Public Use File, a newly released file which includes 2014 claims information from 4,025 hospice providers, accounting for more than $15 billion in Medicare payments during 2014.[101]

- An update to the Market Saturation and Utilization Tool (formerly called the Moratoria Provider Services and Utilization Data Tool), which provides interactive maps and related data sets showing provider services and utilization data.[102]

2. Moratoria and Other Enforcement Priorities

The ACA authorizes CMS to impose moratoria on certain geographic areas, blocking any new provider enrollments within regions designated as "hot spots" for fraud.[103] The moratoria, which may focus on particular provider categories, are imposed after consultation with the DOJ and HHS OIG (and, in the case of Medicaid, with State Medicaid agencies) and reviewed every six months to assess whether they remain necessary.[104]

In 2013 to 2014, CMS established moratoria affecting home health programs and ground ambulance services in several cities.[105] On July 29, 2016, CMS announced that it would expand and extend these moratoria to cover home health agencies state-wide in Florida, Texas, Illinois, and Michigan, and non-emergency ground ambulance suppliers in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Texas.[106] (The initial versions of these moratoria focused on particular cities within those states.[107]) CMS did, however, lift a temporary moratorium affecting Medicare Part B, Medicaid, and Children’s Health Program emergency ground ambulance suppliers; the moratorium now in place relates specifically to non-emergency services.[108]

C. OCR and HIPAA Enforcement

In November 2016, HHS’s Office of Civil Rights ("OCR") reported that since the Health Information Portability and Accountability Act ("HIPAA") privacy rules went in effect in April 2003, it has received more than 146,345 HIPAA complaints, of which it has resolved 143,230.[109] In the 2016 calendar year, OCR reported thirteen settlements totaling approximately $23.5 million.[110] This is a dramatic increase from the approximately $6.2 million reported in 2015 from six settlements.[111]

1. 2016 Developments

a) HIPAA Compliance Audits

As noted in our 2015 Year-End Update, OCR announced that HIPAA compliance audits were to begin anew in early 2016.[112] In July 2016, OCR announced its launch of Phase 2 of the Privacy, Security, and Breach Notification Audit Program; the pilot audit program and Phase 1 occurred in 2011 and 2012.[113] Phase 2 primarily will involve desk audits supplemented by some on-site audits to review the policies and procedures of covered entities and business associates with respect to the specifications of the Privacy, Security, and Breach Notification Rules.[114]

The audit process will begin with an email request for verification of an entity’s address and contact information, followed by a pre-audit questionnaire to gather data regarding the size, type, and operations of prospective auditees. If an entity does not respond to the questionnaire, OCR will gather publically available data. This data, along with other information, will be used to create potential audit subject pools. OCR has stated that it is "committed to transparency about the [audit] process [and] will post updated audit protocols on its website" as the audit process progresses.[115]

b) HIPAA in the Digital Age

On October 6, 2016, HHS OIG released guidance on HIPAA and Cloud Computing.[116] This guidance confirms that a covered entity or business associate may engage a cloud service provider ("CSP") for electronic protected health information ("ePHI"), but cautions that the covered entity or business associate "should understand the cloud computing environment or solution offered by a particular CSP so that the covered entity (or business associate) can appropriately conduct its own risk analysis and establish risk management policies."[117]

Of course, all CSPs engaged by HIPAA-covered entities (or their business associates) are themselves considered business associates under the Act, subjecting them to the limitations on uses and disclosure of protected patient information, as well as the Act’s breach notification requirements.[118] The guidance provides that "[t]his is true even if the CSP processes or stores only encrypted ePHI and lacks an encryption key for the data"[119]–that is, even if the CSP itself cannot actually access the underlying protected information. For this reason, providers who choose to engage CSPs should take care to enter HIPAA-compliant business associate agreements,[120] which will at least ensure the CSPs are aware of the applicability of the Act to their operations on the provider’s behalf.

Notably, a CSP may be subject to the Act even if the provider that supplies HIPAA-protected data does not apprise the CSP of the nature of the information. Indeed, OCR recognizes that "a CSP may not have actual or constructive knowledge that a covered entity or another business associate is using its services to create, receive, maintain[] or transmit ePHI."[121] In such an instance, "if a CSP becomes aware that it is maintaining ePHI, it must come into compliance with the HIPAA Rules, or securely return the ePHI to the customer or, if agreed to by the customer, securely destroy the ePHI."[122]

This guidance provides important information for covered entities, their business associates, and CSPs, particularly in light of the past year’s hefty OCR settlements related to the use of cloud services.[123]

2. HIPAA Enforcement Actions

In 2016, the smallest HIPAA penalty assessed was $25,000, whereas the largest weighed in at $5.55 million,[124] but it is clear that OCR has its eyes on resolutions that fall on the latter end of the spectrum. Recently, OCR issued a memorandum noting that it will continue to focus enforcement efforts on cases that "identify industry-wide noncompliance, where corrective action under HIPAA may be the only remedy, and where corrective action benefits the greatest number of individuals."[125] The enforcement activity described below generally furthered this mission; OCR focused on widespread alleged wrongdoing and approaches to data processing and storage that present particular and unique risks to patient information.

The year’s biggest settlement–and the largest settlement to date against a single entity–was announced in August 2016. Advocate Health Care Network agreed to pay $5.55 million to resolve allegations that it had violated HIPAA on several occasions with regard to its patients’ ePHI; the entity also agreed to adopt a corrective action plan.[126] OCR’s investigation, which began in 2013, targeted purported issues that ran the gamut of potential HIPAA compliance issues.[127] According to OCR, Advocate failed to

conduct an accurate and thorough assessment of the potential risks and vulnerabilities to all of its ePHI; implement policies and procedures and facility access controls to limit physical access to the electronic information systems housed within a large data support center; obtain satisfactory assurances in the form of a written business associate contract that its business associate would appropriately safeguard all ePHI in its possession; and reasonably safeguard an unencrypted laptop which was left in an unlocked vehicle overnight.[128]

It appears that "the extent and duration" of Advocate’s alleged HIPAA compliance failures factored into the size of the settlement, and that OCR intended for the settlement to "send[] a strong message" to providers regarding ePHI security.[129]

Following an OCR investigation that revealed widespread data maintenance problems, Oregon Health & Science University ("OHSU") agreed to a settlement in July 2016 that provided for a monetary payment of $2.7 million and a comprehensive three-year corrective action plan.[130] The investigation, which began "after OHSU submitted breach reports . . . involving unencrypted laptops and a stolen unencrypted thumb drive," revealed extensive vulnerabilities within the provider’s compliance program.[131] In particular, OCR uncovered OHSU’s storage of ePHI of more than 3,000 individuals "on a cloud-based server without a business associate agreement."[132]

Another HIPAA enforcement example–Care New England Health System’s ("CNE") $400,000 settlement with OCR on September 23, 2016–further underscores the importance of business associate agreements.[133] "CNE provide[d] centralized corporate support for its subsidiary affiliated entities," including Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island.[134] The settlement resolved alleged HIPAA violations in connection with the hospitals’ transmission of PHI to CNE, having "failed to renew or modify its business associate agreement."[135] OCR emphasized that "[t]his case illustrates the vital importance of reviewing and updating, as necessary, business associate agreements, especially in light of required revisions under the Omnibus Final Rule, [which] outlined necessary changes to established business associate agreements and new requirements which include provisions for reporting."[136]

On July 21, 2016, the University of Mississippi Medical Center ("UMMC") agreed to pay $2.75 million and adopt a corrective action plan to resolve allegations that it violated HIPAA.[137] OCR’s investigation "was triggered by a breach of unsecured ePHI affecting approximately 10,000 individuals."[138] OCR determined that despite being "aware of the risks and vulnerabilities to its systems as far back as April 2005, [UMMC undertook] no significant risk management activity until after the breach [as a result of] organizational deficiencies and insufficient institutional oversight."[139] This case underscores that "[i]n addition to identifying risks and vulnerabilities to their ePHI, entities must also implement reasonable and appropriate safeguards to address them within an appropriate time frame."[140]

St. Joseph Health System ("SJHS") entered into a $2.14 million settlement on October 17, 2016 for alleged HIPAA violations in connection with "a report that files containing [ePHI] were publicly accessible . . . from February 1, 2011, until February 13, 2012 via Google and possibly other internet search engines."[141] This vulnerability stemmed from a file sharing application on the server that SJHS purchased to store the files. The default settings of the server "allowed anyone with an internet connection" to access the files and consequently, the public conceivably could have accessed the .pdf files "containing ePHI of 31,800 individuals, including their names, health statuses, diagnoses, and demographic information."[142] As part of the settlement, SJHS must implement a corrective action plan.[143]

This past year’s final OCR settlement came in November. The University of Massachusetts Amherst ("UMass") agreed to pay $650,000 to resolve allegations arising from an OCR investigation triggered by a report that a malware program that infiltrated a workstation in UMass’s Center for Language, Speech, and Hearing (the "Center") led to the "impermissible disclosure of [ePHI] of 1,670 individuals."[144] According to OCR, its investigation discovered the following potential violations: UMass "failed to designate all of its health care components" and accordingly "did not implement policies and procedures at the Center to ensure [HIPAA] compliance"; UMass did not "implement technical security measures at the Center to guard against unauthorized access to ePHI" (e.g., failing to implement a firewall); and UMass "did not conduct an accurate and thorough risk analysis" relating to the security of PHI.[145] According to OCR, the settlement amount reflects the fact that UMass "operated at a financial loss in 2015."[146]

III. Anti-Kickback Statute Developments

A. AKS-Related Case Law

Federal courts handed down several notable decisions interpreting the AKS during the second half of 2016. Most notably, the Fifth Circuit offered guidance (albeit in an unpublished opinion) on the bounds of the "one purpose" test for assessing the AKS’s inducement element.

In United States ex rel. Ruscher v. Omnicare, Inc., the relator, a former employee of Omnicare, alleged that the company violated the AKS by offering prompt payment discounts and writing off debt owed to it by skilled nursing facilities in exchange for referrals to its long-term care pharmacy business. But the Fifth Circuit affirmed the district court’s grant of summary judgment to Omnicare. The court explained that although relators "need only show that one purpose of [] remuneration [is] to induce [] referrals . . . [t]here is no AKS violation . . . where the defendant merely hopes or expects referrals from benefits that were designed wholly for other purposes."[147]

According to the court, the evidence indicated that Omnicare was "trying to collect verifiable debt and settle billing disputes without necessarily aggravating [] its clients in the midst of ongoing or anticipated contact negotiations."[148] The relator offered no evidence that Omnicare "designed its settlement negotiations and bad debt collection practices to induce" referrals. Nor did the relator show that Omnicare tied its collection practices to an effort to secure referrals. Yet, "[i]f the purported benefits were designed to encourage [skilled nursing facilities] to refer Medicare and Medicaid patients to Omnicare," the Fifth Circuit observed, "one might expect to find evidence showing that the [facilities] at least knew about those benefits."[149] As such, the court determined that "[a]t best, the evidence support[ed] a finding that Omnicare did not want unresolved settlement negotiations to negatively impact its contract negotiations with [] clients and was, likewise, avoiding confrontational collection practices that might discourage [clients] from continuing to do business with Omnicare."[150]

Thus, the Fifth Circuit confirmed some bounds on the inducement standard, which may offer defendants in AKS-predicated FCA cases an avenue to defend business practices that are not designed to induce referrals, even if they are providing some remuneration to a referral source.

B. Guidance and Regulations

On December 7, 2016, more than two years after issuing the proposed rule discussed in our 2014 Year-End Update, HHS OIG issued a final rule that creates additional safe harbors to the AKS and revises the definition of "remuneration" under CMP regulations. According to HHS OIG, the new rule "enhances flexibility for providers [] to engage in health care business arrangements to improve efficiency and access to quality care while protecting programs and patients from fraud and abuse."[151] The final rule took effect on January 6, 2017.[152]

1. Additional or Modified Safe Harbors

HHS OIG finalized each AKS safe harbor rule that it proposed with certain modifications based on the comments it received.[153] As reported in our 2014 Year-End Update, four new or revamped safe harbors may have the most significant effects on health care providers; those safe harbors pertain to: (a) free or discounted local transportation to federal health program beneficiaries; (b) certain cost-sharing reductions or waivers for emergency ambulance services; (c) transactions between Federally Qualified Health Centers and Medicare Advantage organizations; and (d) referral services.[154]

a. Free or Discounted Local Transportation

The final rule allows "eligible entities" to provide free or discounted local transportation to "established patients" so long as the entities comply with certain conditions. HHS OIG had initially proposed that a patient would be considered "established" only after the patient "had attended an appointment with that provider or supplier," but the final rule broadens the definition of "established patient" to encompass any patient that has made an appointment with the provider or supplier.[155]

Conditions for offering such transportation include the following: (1) the entity may not advertise or market the program to patients or other potential referral sources; (2) the entity may not advertise health care items or services during the transport; (3) drivers must not be paid on a per-beneficiary-transported basis; (4) the transportation must not be by air, luxury, or ambulance-level transport; (5) eligible entities must have a set policy regarding the availability of transportation assistance, which is applied uniformly and consistently; (6) the distance transported must not exceed twenty-five miles for patients in urban areas or fifty miles for patients in rural areas; and (7) the entity must bear the costs of the free or discounted local transportation service.[156]

b. Reductions or Waivers for Emergency Ambulance Services

The final rule allows the reduction or waiver of coinsurance or deductible amounts owed for emergency ambulance services.[157] This safe harbor applies to amounts owed under federal health care programs, and only for emergency ambulance services provided by a state, a political subdivision of the state, or a tribal health program.[158] To qualify, the ambulance provider or supplier must offer the reduction or waiver on a uniform basis, without regard to patient-specific factors, and not shift costs to any state or federal health care program.[159]

c. Transactions between Federally Qualified Health Centers and Medicare Advantage Organizations

In its final form, this safe harbor protects "any remuneration between a federally qualified health center ["FQHC"] (or an entity controlled by such a health center) and a [Medicare Advantage] organization pursuant to a written agreement" under the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003, so long as the level and amount of the payment to the FQHC does not exceed the level or amount for similar providers.[160] HHS OIG clarified that the remuneration does have to meet a "fair market value" requirement to be protected under the safe harbor.[161]

d. Technical Change to the Safe Harbor for Referral Services

HHS OIG proposed this rule change, discussed in our 2014 Year-End Update, to correct an inadvertent error in the language of the safe harbor for referral services. The final rule effectively reverts the language of the safe harbor to the language of its 1999 version. The final version of the safe harbor now "precludes protection for payments from participants to referral services that are based on the volume or value of referrals to, or business otherwise generated by, either party for the other party."[162] Previously, the safe harbor excluded "payments . . . or business otherwise generated by either party for the referral service."[163]

2. Exclusions from "Remuneration" under Civil Monetary Penalties Rules

As described in our 2014 Year-End Update, the CMP law proscribes the offer or transfer of remuneration to Medicare or Medicaid beneficiaries that may induce the beneficiaries to order or receive items or services paid for by federal or state health care programs.[164] The final rule carves out several exceptions to what is considered "remuneration" under the law: (1) "[c]opayment reductions for certain hospital outpatient department services"; (2) certain remuneration that encourages access to care (while posing a low risk of abuse); (3) "coupons, rebates, or other" retailer reward programs that meet specified requirements; (4) "certain remuneration to financially needy individuals"; and (5) "copayment waivers for the first fill of generic drugs."

HHS OIG has explicitly cautioned, however, that these CMP law exceptions "do not provide protection under the anti-kickback statute" and that providers could consider requesting protection from sanctions under the AKS for similar arrangements through HHS OIG’s advisory opinion process.[165]

C. Notable Settlements

Providers entered into several noteworthy AKS-predicated settlements during the second half of 2016.

- As noted above, two Georgia-based subsidiaries of Tenet Healthcare agreed to pay forfeiture money judgments totaling approximately $146 million as part of a larger settlement, in part to resolve allegations that they conspired to violate the AKS by paying kickbacks for referrals.[166]

- In October 2016, Omnicare, Inc., the nation’s largest nursing home pharmacy, agreed to pay $28.13 million to settle claims that it solicited and received kickbacks from pharmaceutical manufacturer Abbott Laboratories in exchange for promoting and purchasing the manufacturer’s prescription anti-epileptic drug for controlling behavioral disturbances when reviewing medical charts as the nursing homes’ consultant pharmacy.[167] According to the government’s complaint in the two consolidated whistleblower lawsuits, Omnicare allegedly concealed improper market share rebate payments conditioned on the company’s active promotion of the drug, payments for market data and management conferences, and other improper grants and payments as rebates, educational grants, and other corporate financial support.[168] This settlement follows on the heels of the government’s previous civil and criminal resolution with Abbott in May 2012 for $1.5 billion.[169]

- As part of an initiative focusing on the submission of improper TRICARE claims by compound pharmacies, several owners of QMedRx agreed in September and October 2016 to pay $7.75 and $4.25 million, respectively, to resolve allegations that they violated the FCA by submitting claims for compound prescriptions that were tainted by alleged AKS violations between January 2013 and January 2014.[170] Previously, in December 2015, the former CEO and co-owner also agreed to pay $6.5 million in restitution for his role in the purported scheme.[171] Among other alleged conduct, the government asserted that the claims were improper because of allegedly improper incentive compensation arrangements for marketers who obtained the prescriptions from physicians.

IV. Stark Law Developments

The second half of 2016 saw additional developments in the interpretation and enforcement of the Stark Law, or physician self-referral law. First, Congress took several steps toward possible reform of the Stark Law and its related regulations. Second, CMS issued its 2017 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule Update, with several updates relevant to Stark Law compliance. Finally, recent settlements illustrate the ways in which the government continues to hold both individuals and companies accountable for Stark Law violations.

A. Legislative Developments

In our recent 2016 Mid-Year Update, we reported on several pieces of proposed legislation with implications for the Stark Law: H.R. 776, H.R. 1083, and H.R. 5088. None of these items have moved forward since our last report.[172] Although progress on those bills has stalled, Congress remains focused on Stark Law issues.

At the end of June 2016, the U.S. Senate Committee on Finance issued a report titled: "Why Stark, Why Now? Suggestions to Improve the Stark Law to Encourage Innovative Payment Models."[173] The report notes that despite the Stark Law’s intended effect–to provide a bright-line rule to prevent physician self-referral–the law has resulted in a vastly complex and overly broad scheme that has "created a minefield for the health care industry."[174] The report describes the obstacles that the Stark Law has created for alternative payment models and notes that the law’s proscriptions are, in fact, not necessary given the incentive structures of many payment models. Following an in-depth analysis, the Committee stated that it would continue to examine issues arising from the Stark Law and consider reforms.

In July 2016, the same Senate Committee held a hearing titled: "Examining the Stark Law: Current Issues and Opportunities" to address these issues.[175] In his introductory statement, Senator Orrin Hatch explained that although the Stark Law was passed with the best of intentions, it has become a muddled and complex collection of regulations and exceptions.[176] In response, Senator Hatch explained, the Committee intended to explore possible changes to the Stark Law to make it more practicable and to align its requirements with the payment structures common in the health care industry. In his statement, Senator Ron Wyden emphasized the twin priorities of coordination between health care providers and protection of providers’ independent medical judgment, which underpin the Stark Law, and his hope that the hearing would lead to productive discussions regarding these issues.[177]

B. Regulatory Updates

In November 2016, CMS issued its 2017 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule update, which included several items relevant to Stark Law compliance.

First, CMS reissued a regulation that prohibits the use of "per-click" fees for equipment or space lease arrangements, as well as payment rates based upon a calculation that accounts for services provided to patients that the lessor referred to the lessee.[178] In a recent opinion, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit overturned an earlier iteration of this prohibition after rejecting the rationale CMS initially provided for the restriction. Specifically, the court concluded that CMS’s reliance on a reinterpretation of a 1993 House Committee Report was arbitrary and capricious. The court explicitly noted, however, that CMS had the authority to issue the regulation.[179] CMS attempted to respond to the D.C. Circuit’s concerns by relying exclusively on the Secretary’s authority to impose any additional requirements necessary to prevent program or patient abuse. Under the reissued regulation, compensation arrangements for leases of space or equipment may not involve per-unit-of-service rental charges, if those charges are based upon patient services provided to referrals by the lessor to the lessee.[180]

Second, CMS adopted updates to the list of Current Procedural Terminology/Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System ("CPT/HCPCS") codes that define designated health services, or "DHS," under the Stark Law and incorporate additional services that may qualify for exceptions to the law.[181] Finally, CMS added a minor change to its instructions regarding how to submit a Stark advisory opinion request.[182]

C. Significant Settlements

Recent settlements underscore the continued efforts of the Department of Justice and HHS OIG to enforce Stark Law prohibitions and related regulations against both companies and individuals.

- In July 2016, Lexington Medical Center settled allegations of Stark Law and FCA violations for $17 million and agreed to enter into a five-year CIA intended to prevent similar future issues.[183] The allegations concerned financial arrangements with twenty-eight outside physicians that allegedly exceeded fair market value, were not commercially reasonable, or were based instead on the value or volume of referrals to the hospital. The hospital admitted no wrongdoing.

- In September 2016, the former CEO of Tuomey Healthcare System, Ralph J. Cox III, settled allegations that he had caused the company to enter into problematic contracts with nineteen physicians in violation of the Stark Law.[184] Under the settlement, Cox must pay $1 million and is barred from participating in federal health care programs for four years. This settlement follows the $237 million verdict (discussed in our 2015 Year-End Update) the DOJ secured against Tuomey for billings for services by physicians with financial relationships with the company that were deemed to be improper.

V. Developments in Payments and Reimbursements

With the change in administration, 2017 could be an interesting and dynamic year for the regulation of government health program payments and reimbursements. In the meantime, we address below developments relating to several issues on which we have reported previously. Through the end of 2016, CMS continued to promulgate rules and regulations designed to transition payment and reimbursement systems for federal health programs away from quantity-based metrics and toward quality-based metrics. This was highlighted by CMS’s finalization of the rule implementing the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act ("MACRA"). CMS also issued its final rule regarding 340B ceiling prices.

A. MACRA and Other Developments in Continued Shift Towards Pay-for-Performance

In our 2016 Mid-Year Update, we noted that HHS had reached its goal of tying thirty percent of Medicare payments to quality through alternative payment models. The agency has set its next goal: to tie fifty percent of Medicare payments to quality metrics by 2018. In keeping with that goal, CMS finalized MACRA, proposed a new rule regarding episode payments for hospital care, and put the finishing touches on a new rule concerning primary care payments.

1. The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act

In October 2016, as part of CMS’s move towards a "pay-for-performance" model, CMS issued its final rule implementing MACRA. The rule repeals the Medicare Sustainable Growth Rate methodology and replaces it with a new payment approach.[185]

Specifically, the rule sets the parameters for the two different payment tracks, the Merit-Based Payment Systems ("MIPS") and the Advanced Alternative Payment Models ("APMs"), which together form the basis for MACRA’s "Quality Payment Program." We reported on the details of these two different payment tracks in our 2016 Mid-Year Update, in our discussion of the MACRA proposed rulemaking. MIPS will essentially serve as the base or standard payment system by which providers will receive either an upward, downward, or neutral payment adjustment based on their performance in four categories: quality; use of electronic health records; clinical practice improvement activities; and cost.[186] Advanced APMs, an alternative to MIPS, will operate as more generous incentive programs that are exempt from the MIPS requirements.[187] To qualify for the MIPS exemption, however, providers in the Advanced APMs track must accept some amount of downside financial risk.[188]

In response to a record number of comments during the comments period, CMS made a number of changes and reduced certain requirements of the proposed rule. This is highlighted by the establishment of calendar year 2017 as the "transition year," during which the reporting requirements placed on providers will be significantly reduced.[189] According to CMS, the goal of the transition period is to give providers greater flexibility and to allow them to adopt the new payment system at their own pace.

As part of the transition period, providers now have four potential paths for reporting during 2017: (1) report under MIPS for ninety days; (2) report under MIPS for less than a year but more than ninety days and report more than one quality measure, more than one improvement activity, or more than the required measures in the advancing care information performance category; (3) report one measure in each MIPS category (besides resource use, which is automatically reported) for the entire year; or (4) participate in an Advanced APM.[190] As providers progress through the four different reporting options, their payment adjustment improves, with the first (and least burdensome) path resulting in no negative penalty and the last (the Advanced APM) resulting in a five percent incentive payment.[191]

In addition, CMS made some other important changes to the final rule in an attempt to accommodate smaller practices and to make it easier to qualify as an Advanced APM. For instance, CMS increased the low-volume thresholds that dictate which providers must participate in the program; in the final rule, the threshold is $30,000 in Medicare Part B allowed charges or less than or equal to 100 Medicare patients.[192] This means that a number of smaller practices that provide a minimal amount of care to Medicare patients will not be subject to the burdensome MIPS requirements. According to CMS, this represents thirty-two and a half percent of pre-exclusion Medicare clinicians but only five percent of Medicare Part B spending.[193] CMS also has accommodated smaller practices by allowing for "virtual groups," a MIPS reporting option under which as many as ten clinicians can combine reporting as one group.[194] The agency will not implement virtual groups in the 2017 transition year, however.

As for the Advanced APMs, in an effort to expand the number of APMs that will qualify under MACRA, the final rule allows for retrofitting existing APMs to qualify as Advanced APMs and provides for the creation of new models.[195] And while Advanced APM providers must still bear responsibility for some financial downside risk, the standard for 2017 and 2018 in the final rule is three percent (down from four in the proposed rule) of the expected expenditures for which the provider is responsible under the APM itself.[196] Moreover, CMS reduced the complexity of qualifying as an Advanced APM by retracting proposals relating to marginal risk and minimum loss ratio, though these elements will apply to "Other Payer" Advanced APMs starting in 2019.[197]

2. Mandatory Episode Payment

On July 25, 2016, CMS announced the "Notice of Proposed Rulemaking for Bundled Payment Models for High-Quality, Coordinated Cardiac and Hip Fracture Care;" this proposed rule, like other recent payment model rules, is intended to move the Medicare system towards payment systems that compensate for quality rather than quantity of care.[198] In particular, the proposed rule seeks to reward hospitals that work together with physicians and other providers to avoid complications, prevent hospital readmissions, and speed recovery. CMS sought to do so by "bundling" payments around a patient’s total experience of care (i.e., medical care in and out of the hospital), so that hospitals are incentivized to work together with providers outside of the hospital setting.