February 6, 2017

2016 was a pivotal year in global sanctions implementation, relaxation and enforcement. Against a backdrop of rising nationalism, the international community rallied behind the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (“JCPOA”), a deal to ease sanctions on Iran in exchange for limitations on the country’s nuclear program. The United States rolled back decades-old sanctions on Cuba and Burma while implementing measures against the individuals and entities involved in Russia’s annexation of Crimea as well as North Korea’s nuclear and ballistic missile proliferation. The U.S. Department of Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (“OFAC”) sought to explain the shifting regulatory landscape through an unprecedented amount of non-binding guidance, typically in the form of frequently asked questions (“FAQs”). And in a year that defied predictions, global sanctions enforcement marched on: the United Nations provided an international forum for coordinating responses to Iran and North Korea, while the European Union adopted measures to amend the duration of existing sanctions or expand the list of targeted persons, entities and groups.

In many ways, the international business community is still recalibrating in response to the United Kingdom’s vote on “Brexit” and the election of Donald J. Trump in the United States. Global companies that had set a course for 2017 based on the policies of previous administrations now hang in a precarious balance, anxious for any indication as to whether and how the new U.S. regime will enforce, interpret, or revoke existing sanctions law and regulation. In our view, given the frantic pace of President Donald Trump’s first weeks in office as well as his extensive criticism of former President Barack Obama, many sanctions programs could be altered. It is possible that executive measures–especially those issued early in this administration–could be promulgated without OFAC’s typical input; and that the U.S. Congress could respond by codifying existing regulations or seeking to oppose the dictates of the administration.

We believe that the best way to prepare for the future is to understand the precise contours of the present sanctions; and in the face of growing uncertainty we seek to explain and clarify the law and the mechanisms by which it might change. The various U.S. and international sanctions programs are described below, and as changes unfold we will seek to issue additional guidance and clarification.

__________________________

TABLE OF CONTENTS

The United States

II. Other Significant OFAC Regulations

International

A. Policing and Crime Act 2017

Looking Forward

__________________________

THE UNITED STATES

I. Major Program Developments

A. Iran

The Iran sanctions regime changed significantly during 2016, most notably through the implementation of the JCPOA–the Iran nuclear deal that was agreed to in 2015. Although the JCPOA was the dominant story for most of the year, 2016 also brought a significant extension of the Iran Sanctions Act of 1996 and changes to the Iranian Transactions and Sanctions Regulations (“ITSR”).

1. Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action

On January 16, 2016, the key milestone of “Implementation Day” was reached, triggering substantial relief from the comprehensive international sanctions regime against Iran. The milestone followed a determination by the International Atomic Energy Agency (“IAEA”) that Iran had successfully complied with its initial JCPOA obligations with respect to its nuclear program. These obligations included reducing its stockpile of enriched uranium to 300 kilograms or less, dismantling about two-thirds of its centrifuges, and removing the core of the Arak heavy water reactor (to prevent the reactor from being used to produce weapons-grade plutonium)–measures that, together with transparency requirements permitting comprehensive IAEA monitoring, reportedly increase the time it would take Iran to build a nuclear bomb from two or three months to a year or more.[1] Iran satisfied these obligations earlier than most experts had predicted.

As reported in our summary, Implementation Day Arrives: Substantial Easing of Iran Sanctions alongside Continued Limitations and Risks, Implementation Day triggered a substantial targeted easing of U.S. sanctions, together with more sweeping relief from United Nations and European Union sanctions. In addition, waivers of certain provisions of the Iran Freedom and Counter-Proliferation Act of 2012 (22 U.S.C. § 8801 et. seq.) that had previously been put into place contingent on confirmation of Iran’s compliance with its obligations were triggered and took effect.[2]

Notably, and of critical importance in the early days of the Trump Administration, OFAC has issued guidance regarding the applicable policies and procedures that will be triggered if and when the lifted Iranian sanctions “snap back” into effect. In the event of a snapback, OFAC will not retroactively impose sanctions for activities that occurred following Implementation Day.[3] However, any activities following a snapback could be sanctioned, even if the contracts for the activities were signed before the snapback–that is, there is no “grandfather” exception in place to allow pre-snapback contracts to be completed after a snapback.[4]

To ease the transition should sanctions be reimposed on Iran, the United States would allow for a 180-day period to wind down pre-snapback contractual operations or operations undertaken pursuant to an OFAC license.[5] Providing additional goods or services that are not necessary to the winding down of operations during this 180-day period could be sanctionable.[6] However, non-U.S., non-Iranian persons will be permitted to collect payments for goods or services provided to Iran pre-snapback, provided that the payments do not involve U.S. persons or the U.S. financial system.[7]

On Implementation Day, the United States:

|

a. Secondary Sanctions Relief

The majority of the Iran sanctions relief provided by the United States on Implementation Day concerned restrictions on non-U.S. persons (“secondary sanctions”). Pursuant to its obligations under the JCPOA, the United States lifted restrictions on:[8]

- financial and banking transactions with Iranian banks and financial institutions, including the Central Bank of Iran and entities identified as Government of Iran by OFAC (including the opening and maintenance of correspondent and payable through-accounts at non-U.S. financial institutions, investments, foreign exchange transactions and letters of credit);

- transactions in the Iranian Rial;

- provision of U.S. banknotes to the Government of Iran;

- bilateral trade limitations on Iranian revenues abroad, including limitations on their transfer;

- financial messaging services to the Central Bank of Iran and Iranian financial institutions;

- underwriting services, insurance, or reinsurance;

- efforts to reduce Iran’s crude oil sales;

- investment, including participation in joint ventures, goods, services, information, technology and technical expertise and support for Iran’s oil, gas and petrochemical sectors;

- purchase, acquisition, sale, transportation or marketing of petroleum, petrochemical products and natural gas from Iran;

- export, sale or provision of refined petroleum products and petrochemical products to Iran;

- transactions with Iran’s energy sector;

- trade in gold and other precious metals;

- sale, supply or transfer of goods and services used in connection with Iran’s automotive sector; and

- associated services for these categories.

Despite this relief, two aspects of the continuing sanctions regime place key limitations on the activities of non-U.S. persons with respect to Iran, even after Implementation Day. First, non-U.S. persons must continue to take care to avoid transactions involving persons on the SDN List. Second, non-U.S. persons may feel the effects of the stricter regulations that continue to apply to U.S. persons, as U.S. persons may only provide goods, service, or technology if a transaction meets the stricter standards described below. The inability to secure the assistance of U.S. partners, such as financial institutions or suppliers, may make it difficult as a practical matter to pursue transactions under the loosened secondary sanctions regime.

Since Implementation Day, OFAC has also introduced a general license relating to civilian aviation by non-U.S. persons. General License J (which was replaced in December 2016 with slight modifications by General License J-1) permits non-U.S. persons to send eligible aircraft to Iran on temporary sojourn, provided that certain requirements are met.[9] The effect of General License J is to authorize flights by foreign carriers to and from Iran.

For the purposes of this license, eligible aircraft include civilian, fixed-wing aircraft of U.S. origin or containing at least 10% U.S. content that are registered in a third-country.[10] In order to comply with the terms of the general license, the aircraft may not remain in Iran for more than 72 hours, several conditions related to maintaining control over the aircraft must be met, and the aircraft must not be used to transfer technology or prohibited goods to Iran.[11]

As a practical matter, the effect of the general license is to clarify the legal status of a practice already in place: many non-U.S. airlines had already been flying commercial flights to Iran using U.S.-made aircraft.[12] The general license may thus have benefits for the U.S. aircraft leasing industry, as it removes any ambiguity as to whether U.S. companies may supply aircraft to third-country carriers that have flights to Iran.

b. Primary Sanctions Relief

OFAC has also provided some relief from the primary sanctions applicable to U.S. persons, but the changes were less sweeping than those affecting secondary sanctions. The changes to primary sanctions have fallen into three key areas, described in more detail below: (1) foreign subsidiaries of U.S. entities, (2) commercial passenger aviation, and (3) importation of certain foodstuffs and carpets.

i. Foreign Subsidiaries

Also on Implementation Day, OFAC issued General License H, which authorized U.S.-owned or -controlled foreign entities to engage in transactions with the government and people of Iran, subject to certain limitations.[13] General License H expressly preserves some restrictions on the activities of foreign subsidiaries, including (among others) prohibitions on the direct or indirect exportation of goods, technology, or services from the U.S. to Iran, on the transfer funds to, from or through a U.S. financial institution, and on transactions involving persons on the SDN List.[14]

As U.S. persons remain prohibited from participating in or facilitating transactions by non-U.S. persons in violation of OFAC’s primary sanctions, companies wishing to take advantage of General License H must put in place adequate firewalls to ensure that U.S. persons are not involved in Iran transactions by the foreign subsidiary. General License H does, however, provide two specific authorizations affecting U.S. persons:

- U.S. persons may participate in “activities related to the establishment or alteration of operating policies and procedures” of the U.S. parent or the foreign subsidiary in order to permit the foreign subsidiary to engage in transactions authorized by General License H.

- U.S. parent companies may engage in activities to make available to their foreign subsidiaries “any automated and globally integrated computer, accounting, email, telecommunications, or other business support system, platform, database, application, or server necessary to store, collect, transmit, generate, or otherwise process documents or information” related to transactions authorized by General License H.

Given the importance of this issue for multinational companies, OFAC issued a significant amount of non-binding guidance, typically in the form of FAQs, with regard to the scope and contours of General License H. OFAC’s FAQs clarify that an entity is considered U.S.-owned or -controlled if, in the aggregate, U.S. persons hold a 50 percent or greater equity interest in the value or votes of the entity, or if a majority of the board is comprised of U.S. persons, or if U.S. persons “otherwise control[] the actions, policies, or personnel decisions of the entity.”[15] OFAC has clarified that whether U.S. persons “otherwise control” a foreign entity is a fact-specific, case-by-case inquiry into whether there is sufficient U.S. aggregate ownership and indicia of control.[16]

OFAC has also made clear that, although foreign entities may transact with Iran pursuant to General License H, they may not rely on General License H to export U.S.-origin goods to Iran,[17] reexport U.S.-origin goods from a third country if the foreign entity knows or has reason to know that the reexport is intended for Iran,[18] or transact with individuals on the SDN List.[19] U.S. persons may be held liable for actions outside the scope of General License H undertaken by the foreign entities they own or control.[20] OFAC’s guidance further explains that U.S. persons must be “walled off” from any transactions with Iran but may assist in the implementation of policies and procedures that allow the foreign entity to begin conducting its own business with Iran.

General License H authorizes U.S. persons to engage in “activities related to the establishment or alteration of operating policies and procedures of a United States entity or a U.S.-owned or -controlled foreign entity” to the extent necessary to allow the U.S.-owned or -controlled foreign entity to engage in transactions with Iran under General License H.[21] OFAC, in an FAQ, clarified that this provision, which covers the employees, board members, senior management, and outside consultants of entities, allows U.S. persons to take part in the initial determination to engage with Iran under General License H.[22] Further, U.S. persons can be involved in formulating and implementing the necessary policies and procedures to allow an entity to transact with Iran under General License H (and to allow for the recusal of U.S. persons from such transactions), and U.S. persons may then provide training on these new or revised policies or procedures.[23] However, once the initial determination to engage with Iran has occurred, and the policies and procedures for transacting with Iran have been established, U.S. persons are generally prohibited from involvement in any ongoing Iran-related operations, such as “approving, financing, facilitating, or guaranteeing any Iran-related transaction by [a] foreign entity.”[24]

Where a U.S. person is an employee or board member of an entity interacting with Iran under General License H, OFAC’s guidance makes clear that this person must be recused and “walled off” from the Iranian activity.[25] U.S. persons and entities can remain involved in the non-Iran related day-to-day activities of a foreign entity that is U.S.-owned or -controlled, and can receive reports on the foreign entity’s Iran-related activities, provided that there is no “attempt to influence the Iran-related business decisions of such entities based on such reports.”[26]

OFAC also provided some guidance on the provision permitting U.S. parent companies to make available certain “automated and globally integrated” computer systems to foreign subsidiaries that engage with Iran, but the exact scope of that exemption remains unclear. OFAC has explained that “automated” refers to systems that “operate passively and without human intervention to facilitate the flow of data between and among the U.S. parent company and its owned or controlled foreign entities.”[27] Although a system that requires human intervention, such as data entry or processing, to complete a task would not be considered “automated,” some limited human intervention, such as routine or emergency maintenance, is permitted as “ordinarily incident and necessary to give effect to” authorized transactions.[28]“Globally integrated” refers to systems that are “broadly available to, and in general use by, the U.S. parent company’s global organization and its owned or controlled foreign entities”; a system used by the U.S. parent but not made “broadly available” to its foreign entities does not qualify.[29]

This remains a difficult issue for multinational companies, and the scope of General License H remains largely untested. As a result, many companies are continuing to struggle with implementing procedures consistent with General License H in line with broader corporate compliance policies.

ii. Commercial Passenger Aviation

On Implementation Day, OFAC announced a new policy of granting specific licenses on a case-by-case basis allowing U.S. persons (and non-U.S. persons with a nexus to U.S. jurisdiction) to export, sell, lease or transfer commercial passenger aircraft (and spare parts for commercial passenger aircraft) to Iran, and to provide associated services, including warranty, maintenance, and repair services and safety-related inspections.[30] Since Implementation Day, two aircraft manufacturers have obtained specific licenses under this policy, and the first aircraft authorized under the license (an Airbus A-321) has been delivered to Iran Air.[31]

Although sales or leases of aircraft require a specific license, OFAC has put into place a general license (General License I) permitting ancillary activities relating to the negotiation of and entry into contracts under the Statement of Licensing Policy, provided that the performance of any such contracts is conditioned on the grant of a specific license. General License I does not authorize the sale of aircraft or any related services or parts to Iran, but, rather, authorizes those activities that are incident to negotiating and entering into a contract for such a sale.[32] Parties relying on General License I to negotiate contracts for commercial aircraft must make the performance of those contracts contingent on the grant of a specific license.[33] This is a significant departure for the United States, given that in all other OFAC sanctions programs, such executory contracts are prohibited absent a license.

iii. Importation of Foodstuffs and Carpets

On Implementation Day, OFAC also announced a new general license (which became effective January 21, 2016) that permits the importation of Iranian carpets and foodstuffs into the United States.[34] U.S. financial institutions may play a role in such transactions but remain prohibited from any activity that results in a credit to or debit from an Iranian account.[35] As a practical matter, these limitations on direct interactions between U.S. banks and Iranian parties likely mean that a third-country financial institution is needed to serve as intermediary in transactions under this license–similar to the long-standing system in place for licensed sales of agricultural goods and medical items from the U.S. to Iran. Although less economically significant from a U.S. perspective than the other sanctions relief put in place by the JCPOA, this relief was seen as significant by the Iranian government and has the potential to benefit economically vulnerable Iranians.

2. Additional OFAC Guidance Regarding the JCPOA

Over the course of 2016, OFAC issued substantial guidance and FAQs relating to the implementation of the JCPOA. The guidance and FAQs, which have been updated several times throughout 2016, provide additional clarity as to the parameters to these new policies. Much of OFAC’s guidance concerned the intersection between the prohibition on U.S. persons dealing with Iran and the authorization for the foreign entities to do so. In addition to the FAQs described above, OFAC offered express guidance regarding certain financial transactions, due diligence and compliance, licensing policies, and the “snapback” procedures that could be triggered if and when the United States decides to reimpose sanctions on Iran. These issues are described in more detail below.

a. U-Turn Transactions and Correspondent Banking

The interaction between U.S. and non-U.S. financial institutions is the subject of several FAQs issued by OFAC in 2016. Despite some speculation in the press that it would allow such transactions, OFAC made clear in January guidance that “U-turn” transactions involving Iran–whereby Iranian-related transactions involving two non-U.S. entities are processed through the U.S. financial system–remain prohibited.[36] Non-U.S. entities may clear dollar transactions–meaning that they can process a transaction denominated in U.S. dollars–but in doing so, non-U.S. entities must not involve a U.S. financial institution or route any part of the transaction through the U.S. financial system.[37] Non-U.S. financial institutions that transact with non-SDN Listed Iranian persons may, however, open correspondent accounts with U.S. financial institutions.[38] However, those correspondent accounts at U.S. financial institutions cannot be used to process Iranian transactions, as that would involve the U.S. financial institution and the U.S. financial system in a prohibited transaction.[39]

b. Due Diligence and Compliance

OFAC also issued guidance in 2016 regarding the amount of diligence a non-U.S. entity should undertake to ensure that it is not transacting with individuals or entities listed on the SDN List, but the guidance produced few bright lines. Crucially, OFAC stated that merely checking the SDN List alone is not “necessarily sufficient” due diligence.[40] As per its traditional practice, OFAC did not, however, provide definitive guidance as to what level of diligence would be sufficient but rather advised that the level of diligence should conform with “best practices” in the “particular industry at issue” and should comply with the due diligence guidance and expectations of the entity’s home country.[41]

Likewise, OFAC’s guidance that the appropriate level of due diligence for a non-U.S. financial institution “depend[s] on the financial institution’s role in a transaction” leaves open significant questions.[42] For example, OFAC offered little guidance on whether a non-U.S. financial institution must conduct due diligence on its customers’ Iranian customers. OFAC stated that “[w]hile OFAC would consider it a best practice for a non-U.S. financial institution to perform due diligence on its own customers, OFAC does not expect a non-U.S. financial institutions to repeat the due diligence its customers have performed on an Iranian customer,” so long as the non-U.S. institution does not have reason to believe that the customer’s due diligence was deficient.[43] However, the non-U.S. financial institution should “consult with the local regulators regarding due diligence expectations in their domestic jurisdictions.”[44]

OFAC has explained that it is not “necessarily sanctionable” for a non-U.S. person to engage in a transaction with an entity that is not on the SDN List, but is minority owned, or controlled in whole or part, by an Iranian on the SDN List.[45] Nevertheless, OFAC advised that non-U.S. persons, in such a scenario, should exercise caution to ensure that the transaction “do[es] not involve Iranian or Iran-related persons on the SDN List.”[46] In addition, OFAC has clarified that foreign financial entities will not be exposed to sanctions merely on the basis of transactions with Iranian financial institutions that separately have banking relationships with Iranian persons on the SDN List.[47]

Notably, just days into 2017, OFAC issued a crucial piece of guidance regarding the provision of compliance services from U.S. attorneys and compliance counsel.[48] OFAC clarified that U.S. persons are allowed to provide information or guidance regarding the requirements of U.S. sanctions laws administered by OFAC and opinions on the legality of specific transactions under U.S. sanctions laws regardless of whether it would be prohibited for a U.S. person to engage in those transactions.[49]

c. Statement of Licensing Policy regarding Commercial Aircraft

On Implementation Day, OFAC’s Statement of Licensing Policy regarding the sale of commercial aircraft to Iran went into effect. This policy statement established a favorable licensing policy, allowing U.S. and non-U.S. persons (with a nexus to U.S. jurisdiction) to request a specific license to sell (more precisely, to “export, reexport, sell, lease, or transfer”) commercial aircraft to Iran and engage in “services that are ordinarily incident to a licensed transaction and necessary to give effect thereto.”[50] OFAC issued a series of FAQs to accompany the Statement of Licensing Policy, which provide clarity to the range of activities permitted under this new policy.

The FAQs state that among the services that are ordinarily incident to the sale of commercial aircraft to Iran include “transportation, legal, insurance, shipping, delivery, and financial payment services provided in connection with the licensed export transaction.”[51] As an example, providing insurance for the shipment of a licensed aircraft would be considered ordinarily incident to the sale of the aircraft.[52] On the other hand, providing insurance to cover that aircraft for years after its export to Iran would not be considered ordinarily incident to the export of that aircraft.[53] However, a U.S. person could potentially provide this latter service pursuant to a separate, specific license from OFAC for “associated services” relating to commercial aircraft exported to Iran.[54]

“Associated services,” OFAC stated in an FAQ, could include, for example, “provision of warranty, maintenance, repair services, safety-related inspections, and training related to commercial passenger aircraft and spare parts and components for such aircraft exported to Iran pursuant to a specific license.”[55] U.S. persons must seek separate authorization to provide these associated services, as they are not considered “ordinarily incident” to the export of the commercial aircraft.[56] In seeking this separate authorization, U.S. persons must relate the associated service to a specific export of a commercial aircraft (or related part or service).[57] As an example, OFAC may authorize a U.S. person or entity to finance the sale of a particular commercial aircraft, but will not consider an application from a U.S. person seeking to provide “financing services in general.”[58] Notably, non-U.S. persons do not need authorization to provide these associated services, provided that the services (a) do not involve U.S. persons; (b) do not involve “the export or reexport to Iran of items that would require a license for export from the United States to Iran”; (c) “are conducted outside of U.S. jurisdiction”; (d) “do not involve the U.S. financial system”; and (e) do not involve persons or entities on the SDN List.[59] OFAC may, however, authorize non-U.S. persons to provide associated services that would otherwise be prohibited under 31 C.F.R. § 560’s regulations, such as, for example, the export of items from the United States to Iran.[60]

The FAQs clarify that transactions authorized by OFAC under the Statement of Licensing Policy do not need separate authorization from the Department of Commerce, unless the transaction involves an item that is prohibited from export by, or requires a license for export under, the Export Administration Regulations (“EAR”), or involves a person on the Department of Commerce’s Denied Person List or Entity List.[61] The FAQs also clarify that the easing of the policies on the sale of aircraft to Iran does not impact the prohibition on U.S. airlines operating flights to or from Iran.[62]

3. Other Actions

a. H.R. 6297 – Iran Sanctions Extension Act (enacted 12/15/2016)

Although the implementation of the JCPOA was the dominant Iran sanctions story, it was not the only development affecting the Iran sanctions regime in 2016. On December 15, 2016, the Iran Sanctions Extension Act (“ISEA”) went into law without presidential signature, extending the Iran Sanctions Act of 1996 by ten years (through December 31, 2026).[63]

The Obama Administration considered the extension “unnecessary” but explained in a press release that it would not affect the JCPOA, as the administration would continue to use its authority to waive the sanctions affected by the JCPOA while continuing to enforce the sanctions outside its scope.[64] The Iranians have viewed this legislation as a “blatant violation” of the deal.[65]

Although the JCPOA can continue to be implemented (as it has been to date) against the backdrop of the Iran Sanctions Act, the ISEA may have implications for the JCPOA. In particular, the extension of the Iran Sanctions Act renders necessary the exercise of executive authority to waive the relevant sanctions, and it remains to be seen whether it will be the policy of the Trump administration to continue to do so.

b. Amendments to the ITSR

Finally, on December 23, 2016, OFAC adopted a modification to the scope of the medical device and agricultural commodities exceptions to the ITSR.[66] These exceptions were originally created to implement the Trade Sanctions Reform and Export Enhancement Act of 2000 (“TSRA”) and have been modified several times. With the new regulation, OFAC substantially broadened the exemption for medical devices to include any item meeting the definition of “medical device” unless specifically listed as a device requiring specific authorization.[67] OFAC also made a small change to the agricultural commodities exemption to permit the exportation of shrimp and shrimp eggs.[68]

OFAC also substantially expanded the related products and services that can be provided under the medical devices exemption (and to a lesser extent, the agricultural commodities exemption). OFAC regulations now permit the exportation of software or services related to the “operation, maintenance, and repair” of medical devices exported pursuant to an OFAC license.[69] OFAC also expanded the authorizations relating to the provision of replacement parts to allow for ordinary maintenance (previously, the regulations had authorized the export of spare parts only on a one-for-one basis to replace defective parts). In addition, OFAC added provisions permitting the provision of training “necessary and ordinarily incident to” the safe and effective use of the exported agricultural commodities or medical devices.[70]

B. Cuba

1. Regulatory Changes

The diplomatic and economic relationship between the United States and Cuba continued to thaw in 2016, resulting in a series of changes to the Cuba sanctions regime. In January, several regulatory amendments removed restrictions on payment and financing terms for authorized exports and re-exports to Cuba of items other than agricultural items or commodities, and established a case-by-case licensing policy for exports and re-exports. The January amendments further facilitated travel to Cuba for authorized purposes by allowing blocked space, code-sharing, and leasing arrangements with Cuban airlines; additional travel-related and other transactions directly incident to the temporary sojourn of aircraft and vessels; and additional transactions related to professional meetings and other events, disaster preparedness and response projects, and information and informational materials, including transactions incident to professional media or artistic productions in Cuba. The revised Cuban Assets Control Regulations (“CACR”) and EAR took effect on January 27, 2016.[71]

Less than two months later, on March 15, 2016, the U.S. Treasury and Commerce Departments announced additional revisions to the CACR and EAR that authorized travel to Cuba for individual people-to-people educational travel, removing the requirement that such travel be conducted under the auspices of a sponsoring organization.[72] OFAC also removed the limitation on the receipt of compensation in excess of amounts covering living expenses and the acquisition of goods for personal consumption by a Cuban national present in the United States in a nonimmigrant status or pursuant to other non-immigrant travel authorizations issued by the U.S. government.[73] The amendments also authorized certain dealings in Cuban-origin merchandise, allowing,for example, Americans traveling in Europe to purchase and consume Cuban-origin alcohol and tobacco products while abroad similar to the travel exemptions in other sanctions programs.[74] The March amendments authorized certain banking and financial transactions, such as “U-turn” payments through the U.S. financial system, processing of U.S. dollar monetary instruments presented indirectly by Cuban financial institutions, and U.S. bank accounts for Cuban nationals,[75] and allowed persons subject to U.S. jurisdiction to establish and maintain a business and physical presence in Cuba.[76]

As described further in our November 2016 publication, Cuba Sanctions Update – OFAC and BIS Announce Further Amendments to Cuba Sanctions Regulations, the Obama Administration rounded out the year by authorizing certain transactions related to Cuban-origin pharmaceuticals, joint medical research, civil aviation safety-related services and expanding and clarifying authorizations relating to trade and commerce, grants, and humanitarian-related services.[77] Notably, the amendments narrowed the definition of “Prohibited Officials” to mean certain officials in the Government of Cuba as well as the Cuban Communist Party.[78]

The amendments also added a new general license authorizing the importation into the United States, and the marketing, sale, or other distribution in the United States, of Cuban-origin pharmaceuticals approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.[79] With respect to trade and commerce, the U.S. Commerce Department’s Bureau of Industry and Security (“BIS”) significantly broadened its License Exception Support for the Cuban People to authorize exports or re-exports of eligible consumer goods directly to eligible individuals in Cuba for their personal use or their immediate family’s personal use.[80] The amendments also authorized transactions incident to exports and re-exports,[81] allowed importation of previously exported/re-exported items to Cuba for service and repair,[82] and relaxed regulations regarding importation of Cuban merchandise,[83] among other things.

2. OFAC Guidance

Throughout 2016, OFAC issued an unprecedented amount of guidance, typically through frequently asked questions (“FAQs”), to clarify the scope of the amended regulations. On April 21, 2016, OFAC issued eight new FAQs relating to the Cuba sanctions program addressing several topics, most notably “U-turn” transactions[84], and the issuance of insurance coverage to persons engaging in authorized transactions with Cuba.

a. U-Turn Transactions

Unlike the Iran sanctions program, the CACR permits U.S. financial institutions to process U-turn transactions that originate and terminate at accounts maintained by the foreign branches and subsidiaries of U.S. financial institutions, so long as the other requirements of the CACR are met.[85] U-turn transactions are permitted pursuant to the so-called “U-turn general license,” 31 C.F.R § 515.584(d).[86] Under this general license, a U.S. financial institution may serve as the intermediary bank for Cuba-related transactions between non-U.S. persons, such that the U.S. financial institution may process the transaction in U.S. dollars and through the U.S. financial system.[87]

OFAC has provided guidance on the due diligence that U.S. financial institutions must conduct when processing U-turn transactions.[88] Where the remitter or beneficiary of the U-turn transaction is a direct customer of the U.S. financial institution processing the U-turn transaction, the U.S. financial institution is expected to determine the ownership structure, citizenship, and address of the customer, so as to confirm that the transaction is consistent with the U-turn general license authorization in the CACR.[89] Where, however, the remitter or beneficiary of the transaction is not a direct customer of the financial institution, the financial institution may rely on the address provided by the remitter or beneficiary to determine whether the remitter or beneficiary is subject to U.S. jurisdiction, unless the financial institution knows, or has reason to know, that the remitter or beneficiary is a person subject to U.S. jurisdiction.[90]

b. Insurance Industry

The FAQs published in April 2016 also address the insurance industry, clarifying that insurance and reinsurance services can be provided where those services are “directly incident” to underlying activities that are authorized by a general or specific license.[91] For example, because travel to Cuba to engage in religious activities is an authorized activity under § 515.566 of the CACR, providing travel insurance for that activity would be permitted by § 515.566 as well.[92] Likewise, insurance activities directly incident to the export or reexport of goods licensed or goods otherwise authorized for export to Cuba by the Department of Commerce are permitted under § 515.533 of the CACR.[93] For example, the purchase of cargo insurance for the transport of an authorized export to Cuba would be permitted.[94] Insurers do not need a specific license to pay claims on such insurance services that are directly incident to an authorized activity, even where payment of the claim is to a Cuban national.[95]

The corollary to this guidance is that insurers may not provide insurance services for underlying activities that are not authorized by a general or specific license.[96] Thus, for example, insurers cannot provide insurance for foreign companies that are investing in Cuban state-owned businesses as, even if those foreign companies are operating lawfully, they are not acting pursuant to a general or specific OFAC license.[97]

c. Use of U.S. Dollars in Certain Transactions

On July 8, 2016, OFAC issued two FAQs on the use of U.S. dollars for transactions involving Cuba.[98] The first FAQ clarified that U.S. dollars may be used for activities that are authorized by, exempt from, or “not otherwise prohibited by” the CACR.[99] For example, payment in U.S. Dollars for the importation or exportation of books, which falls under 31 C.F.R. § 515.206’s exemption for informational materials, is permitted.[100] Likewise, as discussed above, U-turn transactions are permitted pursuant to the so-called “U-turn general license,” 31 C.F.R. § 515.584(d).

The second FAQ addressed correspondent accounts–i.e., accounts opened by a domestic financial institution through which a foreign financial institution conducts financial transactions.[101] The FAQ clarifies that U.S. financial institutions that maintain correspondent accounts at Cuban financial institutions (pursuant to a general license authorizing such correspondent accounts) may maintain those accounts in U.S. dollars.[102] Further, they may use U.S. dollars for any transactions necessary to open and maintain that correspondent account, such as fees for processing funds transfers.[103] The FAQ also explicitly notes that, although U.S. banks may open correspondent accounts at Cuban banks, the reverse is not permitted–Cuban financial institutions remain prohibited from opening correspondent accounts at U.S. banks.[104]

d. Recordkeeping Requirements of Travel Providers

On July 25, OFAC issued one new FAQ and revised one FAQ, both relating to the recordkeeping requirements of those providing travel to Cuba.[105] The new FAQ, number 38 on the current list, clarifies that carriers, which are required to collect, from each traveler, information on which provision of the CACR authorizes the person’s travel to Cuba, may permissibly choose to collect only the customer’s specific license number, rather than a copy of the certificate granting the specific license itself.[106] In the revised FAQ 39, OFAC stated that travel providers must maintain for five years the record of the certification providing the authorization for each customer’s travel to Cuba, such as, for example, the specific license number.[107] These records can be maintained in any form, including electronically.[108]

e. Travel

On October 14, 2016 OFAC issued additional guidance on travel between the U.S. and Cuba.[109] The guidance addresses which individuals are permitted to travel between the U.S. and Cuba, and what type of cargo can be transported between the two countries. OFAC’s “Guidance Regarding Travel Between the United States and Cuba” addressed three topics: (1) the persons an authorized carrier may transport between the United States and Cuba; (2) the type of cargo an authorized carrier may transport from the United States to Cuba; and (3) the type of cargo an authorized carrier may transport from Cuba to the United States.[110]

The guidance states that there are four categories of persons an authorized carrier may transport between the United States and Cuba.[111] The first category comprises persons who are traveling to or from Cuba pursuant to a general license under one of the 12 categories of travel listed in the CACR, or under a specific license.[112] The second comprises Cuban nationals applying for admission to the United States or a third country with a valid visa or other travel authorization issued by the U.S. government.[113] The third comprises Cuban nationals present in the United States in a non-immigrant status; these persons may be transferred only from the United States to Cuba.[114] The fourth comprises any individual, including a foreign national, traveling on official business of the United States government, of a foreign government, or of an intergovernmental organization of which the United States is a member or holds observer status.[115]

With respect to the type of cargo that may be transported between the United States and Cuba, the guidance notes that all cargo ordinarily incident to the export of items that are authorized by BIS for export to Cuba can be carried to Cuba.[116] Departing from Cuba, the carrier can transport any cargo that has been approved for importation into the United States, as well as the Cuban-origin items purchased for the personal use of the travelers.[117]

OFAC’s October 16 updates to the FAQs highlight some of the significant changes that had been made to the CACR and the EAR. The FAQs note that the spending limits for travelers in Cuba had been lifted, replaced with the limitation that items purchased in Cuba, such as Cuban cigars and rum, must be purchased for personal use.[118] However, the FAQs note that OFAC considers the “personal use” of an imported item from Cuba to include the giving of such merchandise to another as a personal gift.[119] Cuban-origin items purchased in a third country can likewise be imported to the United States, subject to the limitation that the items must have been purchased for personal use only.[120]

f. Other

The FAQs address two significant new general licenses issued by OFAC. As noted, the first permits the importation of Cuban-origin pharmaceuticals into the United States.[121] The second permits persons subject to U.S. jurisdiction to provide services to Cuba or the Cuban government that support infrastructure maintenance and development in Cuba.[122] “Infrastructure,” the FAQ notes, means the systems and assets used to provide Cubans with public transportation, water and waste management, non-nuclear electricity generation and distribution, hospitals, public housing, and schools.[123]

The FAQs also state that items that were, under authorization, exported to Cuba, may be imported back into the United States for servicing and repair.[124] Exporting the repaired item back to Cuba, however, requires a separate authorization pursuant to 31 C.F.R. § 515.533(a) or § 515.559.[125]

C. Burma

Last year saw an historic and almost wholesale revocation of the U.S. sanctions against Burma. After partial easing earlier in the year, the move towards easing culminated in October. On October 7, 2016, President Obama issued Executive Order 13742, lifting almost all remaining sanctions on Burma.[126] It also renewed the waiver of financial and blocking sanctions provided by the JADE Act of 2008.[127] Other effects of Executive Order 13742 include the removal of all 111 individuals and entities blocked pursuant to the Burmese Sanctions Regulations (“BSR”) from the SDN List, the unblocking of all property and interests previously blocked pursuant to the BSR, the revocation of a ban on the import into the U.S. of Burmese-origin jadeite and rubies, and the removal of OFAC restrictions on banking and financial transactions with Burma.

While the vast majority of Burma-related sanctions are now lifted, some restrictions and risks still remain. Although all individuals and entities previously on the SDN List pursuant to the BSR have been removed, some Burmese individuals and entities remain listed under other sanctions programs, such as the North Korean and counter-narcotics sanctions programs. Notably, in an FAQ published on October 7, 2016, OFAC clarified that it would continue to investigate and pursue enforcement activities for any violations of the Burmese Sanctions Regulations that occurred prior to the termination of those sanctions.[128] OFAC’s “longstanding practice,” according to the FAQ, is that “apparent sanctions violations are analyzed in light of the laws and regulations that were in place at the time of the underlying activities.”[129]

In addition, Burma continues to be classified by the Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (“FinCEN”) as a “jurisdiction of primary money laundering concern” under Section 311 of the USA PATRIOT Act.[130] While the classification remains, FinCEN has issued a new administrative exception suspending certain restrictions so U.S. financial institutions can provide correspondent services to Burmese banks subject to the enhanced due diligence requirements of Section 312 of the USA PATRIOT Act.[131]

D. Russia

1. Regulatory Changes

Tensions between the United States and Russia rose to a fever pitch in 2016 amidst Russia’s ongoing actions in Crimea and eastern Ukraine, the increasingly violent conflict in Syria, and allegations that the Russian government planned and authorized interference in the U.S. presidential election.

In response to Russia’s continued integration of Crimea, OFAC designated 37 individuals and entities related to Russia and Ukraine in September 2016. Designated entities included FAU Glavgosekspertiza Rossii, a Russian federal institution authorized to conduct official examinations of project documentation, for its role in Crimea after Russia’s occupation and attempted annexation of the Crimean peninsula.[132] As described below, OFAC subsequently walked back the impact of sanctions on several entities, including FAU Glavgosekspertiza Rossii, due to the company’s central role in authorizing energy projects throughout Russia.

Although the impact of Russia’s alleged interference in the United States election will remain a question for the history books, the former administration worked quickly to issue sanctions in response. On December 29, 2016, President Obama issued Executive Order 13757, “Taking Additional Steps to Address the National Emergency With Respect to Significant Malicious Cyber-Enabled Activities” in response to Russia’s alleged efforts to influence the 2016 U.S. Presidential election through cyber operations.[133] The new E.O. amended the previously unused E.O. 13694, “Blocking the Property of Certain Persons Engaging in Significant Malicious Cyber-Enabled Activities,”[134] which was promulgated on April 1, 2015, following the North Korea hacks against the Sony Corporation. Sanctions were never issued under the 2015 E.O. due to concerns both about the ability to publicize the case against any accused attackers (given the sensitivity of the information) and worries about retaliation.

The authority under E.O. 13694 was amended by E.O. 13757 to allow for the imposition of sanctions on individuals or entities determined to be responsible for tampering, altering, or causing the misappropriation of information with the purpose or effect of interfering with or undermining election processes or institutions. Before this amendment, it was unclear whether E.O. 13694 would encompass interference with elections. E.O. 13757 also imposed sanctions on Russia’s two leading intelligence services–the GRU and the FSB–as well as four top officers of the GRU and three companies that provided material support to the GRU’s cyber operations. These individuals and entities have been added to the SDN List along with two additional affiliated individuals not directly identified in the E.O.[135] In line with almost all other OFAC sanctions, these new sanctions block the assets of these organizations and individuals that are in the United States and prohibit U.S. persons (including banks) from transacting with them. The goal appears to be to chill private companies’ appetites to work with the GRU and FSB in further cyber activities. For a detailed summary of this development and its implications, please see our recent client alert, President Obama Announces New Russian Sanctions in Response to Election-Related Hacking. As described below, on February 2, 2017, OFAC published a general license pursuant to E.O. 13694 to authorize certain otherwise prohibited transactions with the FSB.

In conjunction with these new sanctions, President Obama announced that the State Department would be shutting down two Russian compounds in the United States and declaring 35 Russian intelligence operatives as “persona non grata.”[136]

Notably, as we discuss below, a senior and bipartisan group of U.S. Senators introduced the Countering Russian Hostilities Act of 2017 (S. 94), on January 11, 2017–just days before the inauguration. The proposed legislation would codify most of the sanctions on Russia imposed by Executive Order under the Obama Administration.

2. General Licenses

On February 2, 2017 OFAC issued a general license to allow U.S. companies to enter into limited transactions with the FSB, fixing a technical–and unintended–issue with the prior sanctions. Because the FSB acts as a licensing agency for encryption technology, which includes most electronic devices, the general license was required to remove obstacles for U.S. companies selling devices like cellphones and tablets to Russia.[137]

OFAC issued several general licenses authorizing certain transactions otherwise prohibited by the sanctions enacted by the United States in response to Russia’s attempted annexation of Crimea. On August 31, 2016, General License No. 10 authorized certain transactions otherwise prohibited by E.O. 13685, “Blocking Property of Certain Persons and Prohibiting Certain Transactions With Respect to the Crimea Region of Ukraine,”[138] for a limited period of time necessary to transfer holdings in certain blocked entities.[139] Specifically, General License No. 10 authorized all transactions and activities, otherwise prohibited by E.O. 13685, that were “ordinarily incident and necessary” to divest or transfer to a non-U.S. person holdings in PJSC Mostotrest. The wind-down period for such transactions was specified to be until October 1, 2016.

On December 20, 2016, General License No. 11 authorized certain transactions with FAU Glavgosekspertiza Rossii that were otherwise prohibited by E.O. 13685.[140] Specifically, General License No. 11 authorized all otherwise prohibited transactions and activities ordinarily incident and necessary to “requesting, contracting for, paying for, receiving, or utilizing a project design review or permit from FAU Glavgosekspertiza Rossii’s office(s) in the Russian Federation,” provided that “the underlying project is wholly located within the Russian Federation, and none of the transactions otherwise violate E.O. 13685.”[141]

3. Designations

As described in the chart below, on February 1, 2016 and January 9, 2017, OFAC added several individuals to the SDN List under the authority of the Magnitsky Act, a bill passed in 2012 with bipartisan support intending to punish Russian officials responsible for the death of Russian lawyer Sergei Magnitsky in a Moscow prison.[142] On December 20, 2016, OFAC updated the SDN List and the Sectoral Sanctions Identifications (“SSI”) List with the names of individuals, entities, and vessels to target sanctions evasion and other activities related to the conflict in Ukraine.[143] OFAC previously updated the SDN List on November 14, 2016 with the names of six individuals who represented Crimea and Sevastopol in the Russian State Duma, or Parliament.[144] The United States does not recognize the elections to the Russian State Duma that took place in Crimea as legitimate and designated the individuals for “being responsible for or complicit in actions or policies that undermine democratic processes or institutions in Ukraine.”[145] On September 1, 2016, OFAC updated the SDN List and the SSI List to target sanctions evasion and other activities related to the conflict in Ukraine, by designating certain individuals and entities.[146]

E. North Korea

1. North Korea Sanctions and Policy Enhancement Act

In 2016, the United States and its allies continued to exert pressure on North Korea by instituting further sanctions in response to ongoing nuclear and ballistic weapons testing by the country. On February 18, 2016, President Obama signed into law the North Korea Sanctions and Policy Enhancement Act of 2016 (“NKSPEA”).[147] Passed with overwhelming support in both houses of Congress,[148] the NKSPEA strengthened U.S. sanctions against North Korea while codifying related policy priorities.

The NKSPEA introduced mandatory sanctions against persons who knowingly engage (or attempt to engage) in a variety of activities relating to North Korea broadly relating to the provision of goods, services, or technology with military or intelligence applications, the importation or exportation of luxury goods (directly or indirectly) into North Korea, the facilitation of censorship or serious human rights abuses, or money-laundering, counterfeiting, or narcotics trafficking that supports the Government of North Korea or its senior officials.[149] Although similar sanctions had been available under prior laws, the NKSPEA requires, rather than permits, that the president designate for blocking sanctions any persons found to have engaged in the enumerated activities.[150] The president is also required to investigate any credible reports of these activities.[151] The NKSPEA also permits (but does not require) blocking sanctions against persons who knowingly support persons designated pursuant to an applicable United Nations Security Council resolution, or who knowingly participate in the bribery of, or misappropriation of funds by, a North Korean official.[152]

The NKSPEA imposed export control requirements applicable to state sponsors of terrorism on exports to North Korea by requiring a license for the export of goods or technology covered under Section 6(j) of the Exports Administration Act of 1979 (50 U.S.C. 4605(j)).[153] North Korea was removed from the state sponsors of terrorism list in 2008 and remains off the list, despite an unsuccessful effort in the House of Representatives to require the administration to consider re-designating it.[154]

The NKSPEA required the Secretary of the Treasury, in consultation with the Secretary of State and the Attorney General, to determine (within 180 days after its enactment) whether reasonable grounds exist to conclude that North Korea is a “jurisdiction of primary money laundering concern” under Section 311 of the USA Patriot Act, 31 U.S.C. § 5318A. On June 1, 2016, the Treasury Department announced a finding that North Korea is such a jurisdiction. Although U.S. financial institutions were already prohibited from engaging in direct or indirect financial transactions with North Korean financial institutions, the designation of North Korea as a “jurisdiction of primary money laundering concern” paved the way for further regulations prohibiting the use of correspondent accounts on behalf of North Korean financial institutions and requiring that U.S. financial institutions implement additional due diligence.[155]

The NKSPEA also requires executive departments to analyze and report to Congress on a variety of topics, including cyberattacks against the United States on behalf of the Government of North Korea, human rights issues, and access to cellular and internet communications.[156] Throughout the act, the NKSPEA emphasizes international cooperation, including the importance of United Nations Security Council initiatives.

The Obama Administration initially implemented the changes embodied in both the NKSPEA and parallel United Nations actions (discussed below) through Executive Order 13722, which imposed “additional steps” with respect to the national emergency declared in Executive Order 13466 of June 26, 2008.[157] Specifically, it blocked all property and interests of the Government of North Korea or the Workers’ Party of Korea, as well as the property of certain designated persons determined by the Secretaries of the U.S. Treasury and State Departments to: operate in certain industries in the North Korean economy; have sold or purchased metal, graphite, coal, or software where any revenue or profit benefits the Government of North Korea or the Workers’ Party of Korea; have engaged in abuse or violation of human rights; have engaged in exportation of workers; have engaged in significant activities undermining cybersecurity; have engaged in censorship; or have materially assisted or acted on behalf of blocked persons. The E.O. also prohibited exportation or reexportation of any goods, services, or technology; new investment; and any approval, financing, facilitation, or guarantee by a U.S. person. Additional restrictions included the prohibition of donations to or from blocked persons, a travel ban on blocked persons, and the prohibition of transactions or conspiracies intended to violate the E.O.

At the same time, OFAC also issued nine general licenses to allow U.S. persons to engage in certain classes of otherwise prohibited conduct without needing to apply for a specific license. The general licenses permitted: (1) transactions related to the North Korean Mission to the United Nations; (2) provision of certain legal services; (3) normal service charges owed by blocked accounts; (4) noncommercial, personal remittances; (5) certain services in support of NGO activities; (6) third-country diplomatic and consular funds, (7) telecommunications and mail transactions; (8) certain patent, trademark, and copyright transactions; and (9) emergency medical services.[158]

Throughout 2016, OFAC continued to add additional North Korean entities and individuals across areas including government, financial services, and shipping industries to the SDN List. Notably, in July OFAC added senior North Korean government officials, including Kim Jong Un.[159] On December 2, OFAC added 7 individuals, 16 entities, and 16 aircraft belonging to North Korea’s national airline, Air Koryo.[160]

2. OFAC Guidance

On March 16, OFAC issued ten FAQs to provide guidance on the implementation of Executive Order 13722 as well as the general licenses. The FAQs clarify that, even though the Executive Order prohibits the exportation or reexportation of goods, services, and technology to North Korea, the Department of Commerce, through BIS, retains the authority to license exports and reexports of goods and technology.[161] OFAC’s FAQs also clarify that Executive Order 13722 does not prohibit travel to North Korea.[162] That clarification, however, comes with a major caveat: although travel to North Korea is not prohibited, travelers must comply with all applicable sanctions while doing so, including the prohibition on transacting with the Government of North Korea and the Workers’ Party of Korea, the prohibition on the exportation of goods, services, and technology from the United States to North Korea, and the prohibition on new investment in North Korea.[163] Moreover, OFAC recommends consulting the State Department’s Travel Warning on North Korea before planning travel to North Korea.[164]

F. Kingpin Sanctions

OFAC announced the implementation of new sanctions on May 5, 2016, designating a number of Panama-based individuals and companies, including financial institutions, that have been linked to the “Panama Papers,”[165] an April 2016 leak which revealed the Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca’s use of shell corporations to carry out unlawful activities on behalf of its clients, including significant evasion of international sanctions. OFAC designated the Waked Money Laundering Organization (“Waked MLO”) and its leaders, Nidal Ahmed Waked Hatum and Abdul Mohamed Waked Fares, as Specially Designated Narcotics Traffickers pursuant to the Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Designation Act (the “Kingpin Act”).[166] Panamanian-Colombian-Spanish national Waked Hatum and Panamanian-Lebanese-Colombian national Waked Fares are co-leaders of the Waked MLO, which uses trade-based money laundering schemes, such as false commercial invoicing; bulk cash smuggling; and other money- laundering methods, to launder drug proceeds on behalf of multiple international drug traffickers and their organizations.[167]

OFAC also designated six Waked MLO associates and 68 companies tied to the network, including the principal Panama-based companies allegedly used by the Waked MLO to launder drug and other illicit proceeds such as Grupo Wisa, S.A., Vida Panama (Zona Libre) S.A., and Balboa Bank & Trust.[168] Two attorneys were among the designated individuals for their involvement with Waked MLO and for incorporating shell companies for the network’s activities. All assets of the designated individuals and entities under U.S. jurisdiction or in the control of U.S. persons are frozen, and U.S. persons are generally prohibited from engaging in transactions with them.

On June 1, 2016, OFAC issued a statement on the Felix Maduro Group, also known as Maduro Internacional, S.A., which OFAC also designated in its May announcement as an entity owned and controlled by the Waked MLO.[169] In its statement, OFAC announced that non-U.S. persons will not be designated for engaging in transactions related to the removal of Waked MLO control of the Felix Maduro Group, but should any such transactions involve U.S. persons, the involved parties should apply for a specific license from OFAC.

These designations, as with the October 2015 designation of three Honduran businessmen and seven businesses,[170] demonstrate OFAC’s willingness to cast a wide net under the Kingpin Act, then to mitigate the material economic impact of those designations through general licenses. Concurrent with its May 2016 announcement of the new designations, OFAC issued three general licenses authorizing certain transactions and activities for limited periods of time with five entities owned by the Waked network: Soho Panama, S.A. (a.k.a. Soho Mall Panama), a luxury mall in downtown Panama City; Plaza Milenio, S.A. (Millennium Plaza) and Administracion Millenium Plaza, S.A., related to a hotel complex in Colon, Panama; and two Panamanian newspapers, La Estrella and El Siglo, which are owned by Grupo Wisa, S.A.[171] The first two general licenses assist with “winding down transactions” for a limited time by authorizing specific activities that would otherwise be prohibited. The third general license is intended to allow both Panamanian newspapers to continue printing and operating by authorizing specific activities that would otherwise be prohibited. On May 13, 2016, OFAC published two additional general licenses allowing for non-designated customers to engage in activities necessary for a reorganization period related to transferring any funds or other assets held by Balboa Bank & Trust.

G. Libya

On April 19, 2016, President Obama signed Executive Order 13726, “Blocking Property and Suspending Entry Into the United States of Persons Contributing to the Situation in Libya,”[172] expanding the scope of the national emergency declared in Executive Order 13566 of February 25, 2011. The E.O. cited the “the ongoing violence in Libya, including attacks by armed groups against Libyan state facilities, foreign missions in Libya, and critical infrastructure, as well as human rights abuses, violations of the arms embargo imposed by United Nations Security Council Resolution 1970 (2011), and misappropriation of Libya’s natural resources” as constituting an “unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security and foreign policy of the United States.”

The E.O. blocked the property of any person responsible for, or complicit in, directly or indirectly, any of the following with respect to Libya: actions or policies that threaten peace, security, or stability; actions or policies that obstruct the adoption of or political transition to a Government of National Accord; actions that lead to misappropriation of state assets; threatening or coercing Libyan state financial institutions or the Libyan National Oil Company; planning, directing, or committing attacks against any state facility or installation, any air, land, or sea port, or any foreign mission; targeting of civilians; or illicit exploitation of crude oil or any other natural resources. It also blocked the property of leaders of an entity that has engaged in any of the aforementioned activities, and persons who have materially assisted or acted on behalf of blocked persons. Lastly, the E.O. prohibited donations to or from blocked persons, placed a travel ban on blocked persons, and prohibited transactions or conspiracies that attempt to violate the E.O.

H. Côte d’Ivoire

On September 14, 2016, President Obama signed Executive Order 13739, “Termination of the National Emergency with the Situation in or in Relation to Côte d’Ivoire.”[173] The E.O. found that “the situation that gave rise to the declaration of a national emergency in Executive Order 13396 of February 7, 2006”–namely the massacre of civilians, human rights abuses, political violence and unrest, and attacks against international peacekeeping forces–“has been significantly altered by the progress achieved in the stabilization of Côte d’Ivoire.” These advances include the successful conduct of the October 2015 presidential election, progress on the management of arms and related materiel, and the combating of illicit trafficking of natural resources. In light of these improvements and the removal of multilateral sanctions by the United Nations Security Council in Resolution 2283, the E.O. therefore terminated the national emergency declared in Executive Order 13396 and revoked that order.

II. Other Significant OFAC Regulations

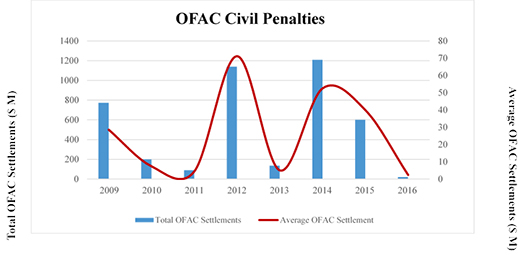

A. Federal Civil Penalties Inflation Adjustment Act

On July 1, 2016, OFAC issued regulations to implement the Federal Civil Penalties Inflation Adjustment Act of 1990.[174] The regulations, which became effective on August 1, 2016, adjust for inflation the maximum amount of the civil monetary penalties that may be assessed under the relevant OFAC regulations (as described in the chart below).[175]

|

Authority |

Former Maximum Civil Penalty |

New Maximum Civil Penalty |

|

International Emergency Economic Powers Act

|

Greater of $250,000 or twice the amount of the underlying transaction |

Greater of $284,582 or twice the amount of the underlying transaction per violation |

|

Trading With the Enemy Act

|

$65,000 |

$83,864 |

|

Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act |

Greater of $50,000 or twice the amount of which a financial institution was required to retain possession or control |

Greater of $75,122 or twice the amount of which a financial institution was required to retain possession or control per violation |

|

Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Designation Act

|

$1,075,000 |

$1,414,020 |

|

Clean Diamond Trade Act

|

$10,000 |

$12,856 |

B. Guidance and FAQs

In 2016, OFAC relied heavily upon the issuance of FAQs and guidance to clarify the scope of several of the sanctions programs that it administers. Although OFAC’s FAQs and other guidance publications do not carry the weight of law or otherwise supplement or modify the regulations and statutes OFAC administers, the FAQs and guidance publications provide important clarification as to how OFAC interprets those regulations and statutes. OFAC provided substantive guidance via FAQ pertaining to the Iran, Cuba, Burma, and North Korea sanctions programs (many of which are discussed in the preceding sections). In addition, OFAC published guidance on the general licenses and exemptions concerning publishing activities. Also in 2016, DOJ published guidance concerning its expectations for entities facing prosecution for criminal sanctions violations that hope to receive voluntary self-disclosure, cooperation, and remediation credit.

1. Publishing Guidance

On October 28, 2016, OFAC published guidance interpreting the general licenses and certain other exemptions authorizing publishing activities under the Cuba, Iran, (now-largely lifted) Sudan and Syria sanctions programs.[176] The guidance addresses three issues: (1) the circumstances under which a person would be considered to be publishing on behalf of a sanctioned government, such that the general license for publishing would not be available; (2) the circumstances under which entities are considered “academic and research institutions” such that the general licenses are available and whether government-affiliated institutions could be so considered; and (3) whether providing peer review, style- and copy-editing, or marketing services falls within the scope of the exemptions and general licenses.[177]

As to the first issue, OFAC clarified that the general licenses and other exemptions would generally apply to publishing activities involving an individual who, though employed by a sanctioned government, is publishing in his or her personal capacity–that is, not on behalf of the sanctioned government.[178] This is a case-by-case determination that must be undertaken by the individual relying on the general license–it is OFAC’s policy not to provide specific authorizations under general licenses.[179] The determination is dependent on several factors, including the identity of the contracting party, the identity of the party receiving the payments, the identity of the party listed in the credit line, and other factors.[180]

As to the second issue–the circumstances under which entities are considered “academic and research institutions” such that the general licenses are available and whether government-affiliated institutions could be so considered–OFAC clarified that an entity need only be an academic or a research institution to qualify for the general license, and an entity is an academic or research institution if the primary function of the entity is research and/or teaching.[181] A government-affiliated entity can qualify under this standard if its primary function is research or teaching.[182] This, again, though, is a case-by-case determination that the person relying on the general license must make.[183]

As to the third issue–whether providing peer review, style- and copy-editing, or marketing services falls within the scope of the exemptions and general licenses–OFAC clarified that peer review, style- and copy-editing are generally outside of the scope of the exemptions for providing “information and informational materials” but generally are within the scope of the general licenses for publishing.[184] However, these activities may not be performed for sanctioned governments or for individuals publishing on behalf of a sanctioned government.[185] But there are limited aspects of these activities–those that do not involve “substantive or artistic alteration or enhancement of informational materials”–that would qualify as exempt under the sanctions programs.[186] Essentially, publication of a “camera ready” article with no edits more substantive than conforming the article to the publication’s physical format and font requirements would be exempt.[187]

2. Self-Disclosure

On October 2, 2016, DOJ published guidance describing how DOJ will assess whether an entity facing prosecution for a sanctions violation can receive voluntary self-disclosure, cooperation, and remediation credit.[188] The guidance notes that entities have typically disclosed export-control and sanctions violations to the relevant regulatory agency, be it OFAC, the State Department, or the Commerce Department, and the guidance encourages entities to continue that practice, but the guidance also requires entities to separately disclose willful violations to DOJ in order to receive credit for having voluntarily self-disclosed the violation.[189] This is a significant departure from past practice, in which the relevant regulatory agency would, in its discretion, decide whether to refer a case to DOJ for prosecution.

In order to receive full credit for having voluntarily self-disclosed a violation, an entity must disclose the conduct “prior to an imminent threat of disclosure or government investigation,” “within a reasonably prompt time after becoming aware of the offense,” and must disclose “all relevant facts known to it, including all relevant facts about the individuals involved in any export control or sanctions violation.”[190]

To receive cooperation credit, an entity must conduct an appropriately tailored investigation and disclose the material facts concerning wrongdoing that it discovers–in particular with respect to any involvement by the corporation’s officers, employees, and agents.[191] In addition, an entity is expected to preserve, collect, and disclose all relevant documents, provide timely updates on the investigation, provide information as to potential criminal conduct by third-party actors, make available its officers and employees to be interviewed, and translate foreign documents.[192]

Remediation credit requires that an entity implement an effective compliance program, the criteria for which will vary depending on the size and resources of the organization.[193] Generally, an effective compliance program will include: 1) a culture of compliance; 2) dedication of sufficient resources to the compliance function; 3) adequate training of compliance personnel to identify potentially risky transactions; 4) independent compliance function; 5) effective risk assessment; 6) a technology control plan and related regular training to ensure export-controlled materials are appropriately handled; 7) appropriate compensation and promotion of a company’s compliance personnel, as compared to non-compliance employees; 8) auditing of the compliance program to ensure its effectiveness; and 9) a reporting structure of compliance personnel that facilitates the identification of compliance problems to senior officials as soon as possible.[194]

Companies that meet these criteria can benefit from reduced penalties and the possibility of a non-prosecution agreement.[195] Notably, however, this guidance differs from DOJ’s similar Foreign Corrupt Practices Act Enforcement Plan and Guidance (the “pilot program”) in that it does not specifically quantify the benefits a qualifying company could receive–the FCPA pilot program specifies a 50 percent reduction off the bottom of the sentencing fine range and a declination of prosecution, but the export control guidance provides that the prosecutors retain discretion to determine the appropriate level of credit.[196]

Notably, the Guidance does not apply to financial institutions, on account of their unique disclosure obligations under other statutory and regulatory regimes.[197]

C. Significant Designations

The following chart summarizes significant OFAC designations made in 2016.

|

Country |

Date |

Authority |

Designation(s) |

| Central African Republic | Mar. 8, 2016 | E.O. 13667 | OFAC added three entities and an individual to its SDN List, including Lord’s Resistance Army and its leader, Joseph Kony, for engaging in the targeting of civilians in the Central African Republic and Zimbabwe through the commission of acts of violence, abduction, and forced displacement.[198] |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo (“DRC”) | Dec. 12, 2016 | E.O. 13413

E.O. 13671 |

OFAC designated two DRC government officials, Evariste Boshab and Kalev Mutondo, for engaging in actions or policies that undermine democratic processes or institutions in the DRC.[199] |

| Mexico | Sept. 23, 2016 | Kingpin Act | OFAC designated four Mexican nationals, pursuant to the Kingpin Act targeting a Tijuana-based cell of the Sinaloa cartel. OFAC designated Eliseo Imperial Castro, a.k.a. “Cheyo Antrax,” Alfonso Lira Sotelo, a.k.a. “El Atlante,” Javier Lira Sotelo, a.k.a “El Hannibal” or “El Carnicero,” and Alma Delia Lira Sotelo for their narcotics trafficking and money laundering in support or on behalf of the Sinaloa Cartel and its high-ranking members.[200] |

| North Korea | Jul. 6, 2016 | E.O. 13687. E.O. 13722 | OFAC added senior North Korean government officials including Kim Jong Un.[201] |

| North Korea | Dec. 2, 2016 | E.O. 13383

E.O. 13722 E.O. 13687 |

OFAC added 7 individuals, 16 entities, and 16 aircraft belonging to North Korea’s national carrier, Air Koryo.[202] |

| Russia | Jan. 9, 2017 | The Magnitsky Act | OFAC added several individuals to the SDN List under the authority of the Magnitsky Act.[203] |

| Russia | Feb. 1, 2016 | The Magnitsky Act | OFAC added several individuals to the SDN List under the authority of the Magnitsky Act.[204] |

| Russia | Sept. 1, 2016 | E.O. 13661

E.O. 13660 E.O. 13685 |

OFAC updated the SDN List and the SSI List to target sanctions evasion and other activities related to the conflict in Ukraine, by designating certain individuals and entities.[205] |

| Russia | Nov. 14, 2016 | E.O. 13660 | OFAC updated the SDN List on November 14, 2016 with the names of six individuals who represent Crimea and Sevastopol in the Russian State Duma (Parliament).[206] |

| Russia | Dec. 20, 2016 | E.O. 13661 | OFAC updated the SDN List and the SSI List with the names of individuals, entities, and vessels to target sanctions evasion and other activities related to the conflict in Ukraine.[207] |