January 25, 2017

The year was yet another eventful one in securities litigation, from the expanded application of Omnicare and Halliburton II, to several significant decisions from the Delaware courts regarding, among other things, the bounds of collateral estoppel analysis and the principles for determining whether a claim is direct or derivative. The year-end update highlights what you most need to know in securities litigation developments and trends for the last half of 2016:

-

We discuss recent trends in securities filings, including the increased number of securities class actions filed in federal court in 2016.

-

We highlight notable post-Omnicare district court decisions, including many courts’ continued application of a high pleading standard for claims brought under Section 11 of the Securities Act and Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act. We also discuss the extension of Omnicare‘s reasoning to claims brought under other federal securities laws.

-

We continue to analyze post-Halliburton II opinions and highlight two cases, currently pending before the Second Circuit, that examine the standard of proof required to rebut the Basic presumption of reliance. Depending on the outcome, the Second Circuit could create a circuit split ripe for Supreme Court review.

-

We also discuss two pending petitions for certiorari that ask the U.S. Supreme Court to determine whether, under SLUSA, state courts lack subject matter jurisdiction over class actions that allege only claims under the Securities Act.

-

We highlight important developments in Delaware courts, including the Court of Chancery’s examination of the bounds of collateral estoppel. The Delaware Supreme Court also clarified the particularity required for a stockholder to plead demand excusal under Rule 23.1, the importance of pre-suit investigations by derivative plaintiffs, and when a claim can be considered direct or derivative.

We highlight these and other notable developments in securities litigation in our 2016 Year-End Securities Litigation Update below.

I. Filing And Settlement Trends

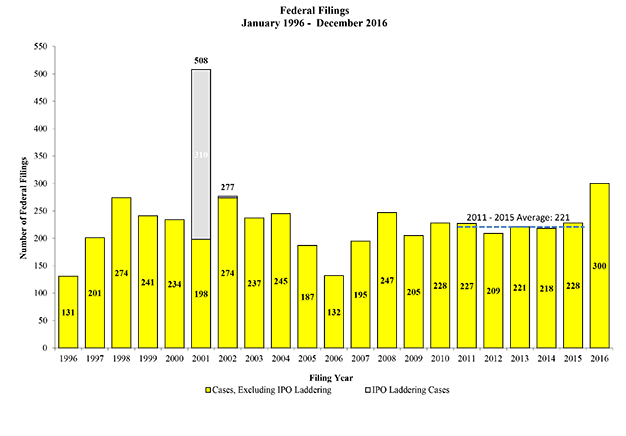

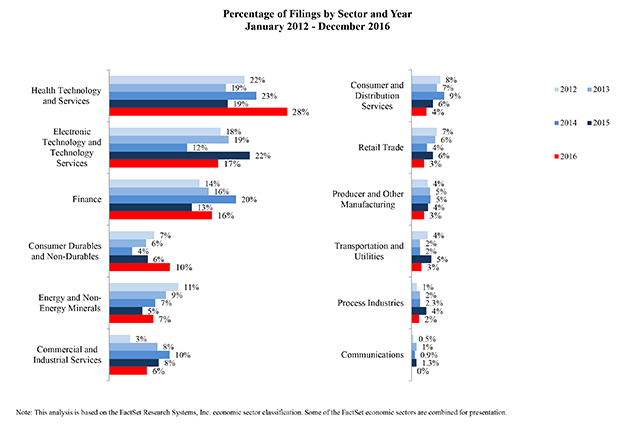

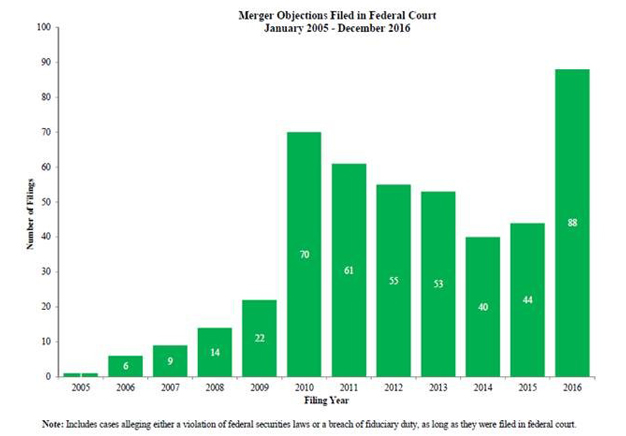

2016 saw a marked increase in the number of securities class actions filed in federal court, more than any year since 2002. According to a newly released study by NERA Economic Consulting ("NERA"), 269 cases have been filed for the 11 months ending in November 2016, compared to the five-year average of 221 cases. The industry sectors most frequently sued in 2016 have been healthcare (28% of all cases filed), with finance (17%), and tech (17%) tied for second place. Of these three sectors, cases filed against tech companies actually dropped significantly year-over-year, from 22% of cases down to 17%. NERA also calculates that the number of "merger objection" cases filed in federal court in 2016 will be dramatically higher in 2016 compared to 2015, by approximately 70%. The 75 cases filed in 2016 represent approximately 28% of all securities cases filed in the federal courts in 2016.

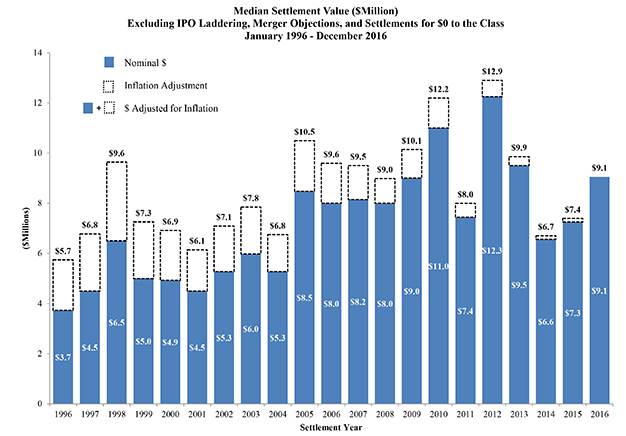

With respect to settlement trends, median settlements in 2016 increased sharply from 2015, while average settlement amounts declined. A wide range of cases comprised the population of settled cases: over 50% of settlements in 2016 were under $10 million, while roughly 20% were over $50 million. Most significantly, median settlement amounts as a percentage of investor losses continue to reflect a pattern that has persisted for decades. In the last fifteen years, median settlement amounts have never exceeded about 3% of total alleged investor losses. In the first half of 2016, the percentage was 2.1%, higher than 2015’s 1.4%, but still a de minimis percentage of alleged investor losses overall.

A. Filing Trends

Overall filing rates in 2016 are reflected in Figure 1 below (all charts courtesy of NERA). 300 cases were filed this year. This figure does not include the many class suits filed in state courts or the increasing number of state court derivative suits, including many such suits filed in the Delaware Court of Chancery. Those state court suits represent a "force multiplier" of sorts in the dynamics of securities litigation in the United States today.

Figure 1:

B. Mix Of Cases Filed In 2016

1. Filings By Industry Sector

New case filings in 2016 reflect a big percentage increase in cases filed against healthcare and finance companies, while the percentage of cases filed against tech companies declined, the biggest drop of any industry sector. See Figure 2 below.

Figure 2:

2. Merger Cases

As shown in Figure 3 below, 88 "merger objection" cases were filed in federal court in 2016, a significant increase over the 44 cases filed in 2015. Note, also, that this statistic only tracks cases filed in federal courts. Most M&A litigation occurs in state court, particular the Delaware Court of Chancery. But as discussed below and in our prior updates, the Delaware Court of Chancery recently announced that the much-abused practice of filing an M&A case followed shortly by an agreement on "disclosure only" settlement is just about at an end, and with it, we anticipate a decline in the total number of M&A suits filed in that court.

Figure 3:

C. Settlement Trends

As Figure 4 shows, median settlements were $9.1 million in 2016, much higher than full year 2015, but still much lower than median amounts in most of the last ten years. One can speculate about what may account for the up-and-down trend in median settlements in the last few years. In any given year, of course, the statistics can mask a number of important factors that contribute to settlement value, such as (i) the amount of D&O insurance; (ii) the presence of parallel proceedings, including government investigations and enforcement actions; (iii) the nature of the events that triggered the suit, such as the announcement of a major restatement; (iv) the range of provable damages in the case; and (v) whether the suit is brought under Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act or Section 11 of the Securities Act. Median settlement statistics also can be influenced by the timing of one or more large settlements, any one of which can skew the numbers. In 2016, for example, the number of settlements above $100 million increased from 13% to 15% of all settlements. At the same time, the number of settlements below $10 million declined from 58% to 51%.

Figure 4:

Perhaps all that can be said of overall settlement trends is that plaintiffs’ lawyers continue to thrive. According to NERA, total attorneys’ fee awards in 2016 were in excess of $1.2 billion, an increase from 2015’s total of $1 billion. These astronomical amounts have become the "new normal," as total fees over the last decade have ranged from a low of $604 million to a high of $1.7 billion, with the amounts in three of the last five years exceeding $1 billion.

II. Falsity Of Opinions–The Expanding Application Of Omnicare In 2017

As we described in our past three updates, the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Omnicare, Inc. v. Laborers District Council Construction Industry Pension Fund, 135 S. Ct. 1318 (2015), has had a significant impact on cases brought under the federal securities laws.

As readers will recall, in Omnicare, the Supreme Court addressed two key issues concerning the scope of liability for false statements of opinion under Section 11 of the Securities Act. First, the Court decided that "a sincere statement of pure opinion is not an untrue statement of material fact, regardless whether an investor can ultimately prove the belief wrong." 135 S. Ct. at 1327 (quotation omitted). Second, the Court held that an omission makes an opinion statement actionable where the omitted facts "conflict with what a reasonable investor would take from the statement itself." Id. at 1329. In other words, an opinion statement becomes misleading "if the real facts are otherwise, but not provided." Id. at 1328.

As discussed below, courts have continued to interpret and apply Omnicare in both Section 11 cases, as well as in cases under Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act and provisions of other federal securities laws. While there have not been any significant appellate court decisions since our last update, pending appeals in multiple Circuits could have a significant impact on how Omnicare is applied in the future. We expect Omnicare to continue to cause ripples in the federal courts in a variety of contexts throughout 2017.

A. Section 11

In our 2016 Mid-Year Securities Litigation Update, we highlighted Tongue v. Sanofi, 816 F.3d 199 (2d Cir. 2016), the Second Circuit’s first published opinion interpreting Omnicare and still the most extensive appellate analysis of Omnicare to date. The Second Circuit held in Sanofi that under Omnicare, an opinion is actionable if "the speaker did not hold the belief she professed" or "the supporting fact she supplied w[as] untrue." 816 F.3d at 210. We interpreted Sanofi to indicate that the Second Circuit may be taking a narrow view of what statements and omissions will be actionable under Omnicare, as the court placed great weight on the principle that "an issuer is not liable [for an opinion statement] merely because it ‘knows, but fails to disclose, some fact cutting the other way.’" Id. at 214 (quoting Omnicare, 135 S. Ct. at 1329).

In its recent decision in In re Vivendi, S.A. Securities Litigation, 838 F.3d 223 (2d Cir. 2016), the Second Circuit attempted to reconcile Omnicare with past precedent including Fait v. Regions Financial Corp., 655 F.3d 105 (2d Cir. 2011), which held that an opinion was actionable only if it was "both objectively false and disbelieved by the defendant at the time it was expressed." Fait, 655 F.3d at 110 (emphasis added). In Vivendi, the appellate court concluded that Vivendi could not argue, supposedly for the first time on appeal, that certain statements at issue were non-actionable opinions because "neither Fait nor Omnicare established an argument regarding the actionability of opinion statements that was previously unknown" in prior precedents. 838 F.3d at 244. In other words, "[t]he argument that certain statements are not materially false or misleading because they contain only opinions was . . . known to be available prior to Fait and Omnicare." Id. This aspect of Vivendi is in some tension with Cox v. Blackberry Ltd., 2016 WL 4470928 (2d Cir. Aug. 24, 2016) (summary order), which recognized that Omnicare "altered the standard previously applied by this Circuit that ‘when a plaintiff asserts a claim based upon a belief or opinion alleged to have been communicated by a defendant, liability lies only to the extent the statement was both objectively false and disbelieved by the defendant at the time it was expressed.’" Id. at *2 (quoting Sanofi, 816 F.3d at 209).

Many district courts have continued to hold plaintiffs to a high standard to plead Section 11 claims following Omnicare. In particular, courts have continued to flesh out what a "reasonable investor" knows under the Omnicare omissions test. This was clear in In re Deutsche Bank AG Securities Litigation, 2016 WL 4083429 (S.D.N.Y. July 25, 2016), where the Southern District of New York noted that a reasonable investor "understand[s] that opinions sometimes rest on a weighing of competing facts." Id. at *18 (citation omitted). The court thus held that "[d]efendants were not required, under Omnicare, to disclose that senior bank officials disagreed with the opinion of a more junior employee," because "[a] reasonable investor does not expect that every fact known to an issuer supports its opinion statement." Id. at *25 (quoting Omnicare, 135 S. Ct. at 1329).

In the same vein, courts have also been clear that conclusory assertions that a defendant should have known of the alleged omissions do not suffice. For example, in Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority v. Orrstown Financial Services, Inc., 2016 WL 7117455 (M.D. Pa. Dec. 7, 2016), the court found that the plaintiff’s pat allegations that any reasonable auditor could have "discovered that the financial statements contained material understatements" of risk assets could not support "a reasonable inference that [the defendant] did not honestly hold the challenged opinion." Id. at *14.

Nevertheless, some plaintiffs have successfully overcome the hurdles posed by the Omnicare test, with specific and creditable allegations being key. In Flynn v. Sientra, Inc., 2016 WL 3360676 (C.D. Cal. June 9, 2016), the plaintiffs successfully alleged that the issuer’s broad but vague disclosures of certain "risks" were "more than plausibly misleading" because "serious regulatory issues had already transpired by the time th[e] statements were made," and the plaintiffs alleged with particularity that the defendants "knew or recklessly disregarded the existence of th[e] issues." Id. at *11. The Central District of California highlighted the plaintiffs’ identification of "particular statements" that they contended were false and misleading, along with the reasons why. Id. at *9. Concluding there was a "strong inference of scienter" with regard to those statements, the court denied in relevant part the motions to dismiss. Id. at *14, *19.

B. Section 10(b)

District courts have also increasingly applied Omnicare to claims brought under Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act and Rule 10b-5 promulgated thereunder. Indeed, as the Southern District of Texas stated in In re: BP p.l.c. Securities Litigation, 2016 WL 3090779 (S.D. Tex. May 31, 2016), "[a]lthough Omnicare was decided in the context of Section 11 of the Securities Act, courts have overwhelmingly applied its holdings in the context of alleged omissions under Section 10(b) of the Securities Exchange Act." Id. at *10. That proved increasingly true throughout 2016.

As with Section 11, many district courts continue to interpret Omnicare to require plaintiffs to meet a high standard to successfully plead Section 10(b) claims alleging misrepresentations or omissions. For example, in Bettis v. Aixtron SE, 2016 WL 7468194 (S.D.N.Y. Dec. 20, 2016), the court granted the defendants’ motion to dismiss Section 10(b) claims. Id. at *1. The plaintiff argued that under Omnicare, the defendant’s "optimistic statements" about a "groundbreaking" sales order were opinion statements resting "on untrue facts or omitted information," thereby rendering the statements misleading. Id. at *15. Observing that statements of corporate optimism "are often considered mere puffery," the court concluded that the "[d]efendants’ optimistic statements about the ultimate fulfillment of the San’an order was paired with ample cautionary language adequate to warn of the relevant risks." Id. at *13-14. Because the plaintiff failed to plead "anything to suggest that [the defendant]’s representations ignored true facts, recited any ‘untrue facts,’ or omitted any information that would have rendered its statements misleading," the court granted the motion to dismiss. Id. at *15, *17.

Similarly, in North Collier Fire Control & Rescue District Firefighter Pension Plan v. MDC Partners, Inc., 2016 WL 5794774 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 30, 2016), appeal filed, No. 16-3727 (2d Cir. Nov. 2, 2016), the court dismissed Section 10(b) claims because "a statement of opinion ‘is not necessarily misleading when an issuer knows, but fails to disclose, some fact cutting the other way.’" Id. at *10 (quoting Omnicare, 135 S. Ct. at 1329). In that case, the plaintiffs alleged that the defendant did not record goodwill impairments relating to poor-performing subsidiaries, but failed to show why recording such impairments was "necessary." Id. at *11. Their allegations were thus "nothing more than disagreement with [the defendant]’s accounting judgments, which cannot support a fraud claim." Id.; see also Dempsey v. Vieau, 2016 WL 3351081, at *3 (S.D.N.Y. June 15, 2016) (dismissing complaint because "[the defendant]’s failure to disclose every fact upon which its accounting judgments were based is not an actionable omission under Omnicare, so long as there was in fact an accounting judgment underlying the statement at issue").

On the other hand, several courts have let stand allegations that the defendants made opinion statements that were potentially misleading under Section 10(b) because the defendants allegedly knew the underlying facts were to the contrary. For instance, in Rihn v. Acadia Pharmaceuticals Inc., 2016 WL 5076147 (S.D. Cal. Sept. 19, 2016), the court denied the motion to dismiss, concluding that the complaint sufficiently alleged that the defendants’ representation "that Acadia was ‘on track’ to submit" an application and was "’comfortable’ with the timeline," when, "[i]n actuality, [the d]efendants lacked information regarding whether" a "significant undertaking" and "critical component" of the application approval process was in place, was materially misleading. Id. at *5-6.

Likewise, in Pirnik v. Fiat Chrysler Automobiles, N.V., 2016 WL 5818590 (S.D.N.Y. Oct. 5, 2016), the plaintiffs plausibly alleged actionable and material representations concerning the defendants’ compliance with regulatory requirements when the defendants, "only months later," "admitted to widespread noncompliance with those requirements." Id. at *5. Further, the plaintiffs adequately alleged scienter by showing that the defendants’ employees had actual knowledge of those shortcomings. Id. at *7. As the court held, "it [wa]s enough at [the pleading] stage for [the p]laintiffs to allege that [the d]efendants were aware of nonpublic facts contradicting their public representations of substantial legal compliance." Id.

C. Other Federal Securities Laws

Courts have begun to extend Omnicare‘s reasoning to claims brought under other federal securities laws. As we discussed in our 2016 Mid-Year Securities Litigation Update, in Special Situations Fund III QP, L.P. v. Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu CPA, Ltd., 645 F. App’x 72 (2d Cir. 2016) (summary order), the Second Circuit addressed Omnicare in the context of misleading audit opinions allegations under Section 18 of the Exchange Act. Since that time, the District of Minnesota granted a motion to dismiss Section 14(e) claims because the plaintiffs failed to sufficiently allege that the proxy statement’s opinion that the merger was fair to stockholders was false or misleading. Ridler v. Hutchinson Tech. Inc., 2016 WL 6246767, at *6 (D. Minn. Oct. 25, 2016). The District of New Mexico has also applied Omnicare to a Section 17(a) claim. See SEC v. Goldstone, 2015 WL 5138242, at *254 (D.N.M. Aug. 22, 2015) (denying summary judgment due to genuine issues of material fact regarding subjective falsity and scienter and stating that "a speaker who knowingly made a false statement did so with scienter").

III. Market Efficiency and Price Impact

Courts also continue to address the implications of the Supreme Court’s 2014 decision in Halliburton Co. v. Erica P. John Fund, Inc. ("Halliburton II"), which held that defendants may introduce evidence to rebut the presumption of reliance established in Basic, Inc. v. Levinson, 485 U.S. 224 (1998) (the "Basic presumption") at the class certification stage.

As of the time of this publication, only the Eighth Circuit has weighed in on the sufficiency of evidence needed to rebut the Basic presumption, as well as each party’s burden of proof, at the time of class certification. As we discussed in detail in our April 15, 2016, client alert, in IBEW Local 98 Pension Fund v. Best Buy Co, 818 F.3d 775 (8th Cir. 2016), the Eighth Circuit reversed class certification, holding that defendant Best Buy had rebutted the Basic presumption through "strong evidence" of no price impact by the alleged misstatements, and the plaintiffs had not satisfied the predominance requirement of Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. In reaching its conclusion, the Best Buy court relied upon the burden-shifting regime of Federal Rule of Evidence 301 ("FRE 301"). Id. at 782. The Eighth Circuit explained that defendants "had the burden to come forward with evidence showing a lack of price impact" (i.e., satisfying the burden of production). See id. (citing FRE 301’s language regarding the burden of production). Once defendants satisfy the burden of production, as the Eighth Circuit held Best Buy did, FRE 301 shifts the burden of persuasion back to the plaintiffs.

Multiple cases are currently pending in the Second Circuit which implicate the same considerations addressed by the Eighth Circuit in Best Buy. On December 23, 2016, the parties to Halliburton, the "case to watch" for many years, announced a settlement of the remanded action, which means we will not hear from the Fifth Circuit as soon as we anticipated in our Mid-Year Update. We will continue to monitor to identify trends or, potentially, a circuit split ripe for Supreme Court review.

A. Circuit Court Activity post-Halliburton II

Key action on post-Halliburton II cases remains in the circuit courts of appeal for now. In the Second Circuit, two cases addressing price impact after Halliburton II have been fully briefed: Ark. Teachers Ret. Sys. v. Goldman Sachs Grp., Inc., 2015 WL 5613150 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 24, 2015) ("Goldman Sachs"), and Waggoner v. Barclays PLC, 312 F.R.D. 307 (S.D.N.Y. 2016) ("Barclays"). The latter was argued on November 15, 2016. Two major issues are addressed in the Second Circuit appeals. First, what standard of proof must defendants meet to rebut the Basic presumption with evidence of no price impact? The second–at issue in Goldman Sachs–is how courts should reconcile Halliburton II with Amgen and Halliburton I. Many of the issues presented in these Second Circuit cases are similar to those argued in the Fifth Circuit in Halliburton, and we expect many of the same issues will filter up to other circuit courts in the near future.

1. Standard of Proof to Rebut the Basic Presumption

In both Goldman Sachs and Barclays, the district courts held that defendants had failed to prove, by a preponderance of the evidence, that the price drop on the corrective disclosure date was not due to revelation of the alleged fraudulent misstatements. Both opinions, however, contained language suggesting a marked split from the FRE 301 burden shifting accepted by the Eighth Circuit in Best Buy. In Barclays, the district court noted that "the vast majority of courts have found that defendants have failed to meet their burden of proving lack of price impact." 312 F.R.D. at 324. The district court’s opinion in Goldman Sachs also contained language–absent from the Halliburton II decision–that suggested that defendants must meet a greater burden: "Defendants’ attempt to demonstrate a lack of price impact merely marshals evidence which suggests a price decline for an alternate reason, but does not provide conclusive evidence that no link exists between the price decline and misrepresentation." 2015 WL 5613150, at *7.

Defendants in both cases have urged the Second Circuit to adopt Best Buy‘s application of FRE 301 to Halliburton II price impact analysis. See Brief of Appellant at 31, Ark. Teachers Ret. Sys. v. Goldman Sachs Grp., Inc., No. 16-250 (2d Cir. Apr. 27, 2016) (hereinafter "Goldman Sachs Brief"); Brief of Appellant at 41, Waggoner v. Barclays PLC, No. 16-1912 (2d Cir. July 25, 2016) (hereinafter "Barclays Brief"). Under this analytical framework, defendants should bear only the burden of production and need only proffer evidence which "could support a reasonable jury finding of the nonexistence of the presumed fact." See, e.g., Goldman Sachs Brief at 31. Once defendants meet the burden of production, the burden shifts back to plaintiffs to establish, by preponderance of the evidence, that the challenged misstatements or omissions actually impacted the price of the stock. Id. at 32; see also FRE 301.

Goldman Sachs and Barclays present similar arguments. First, Basic itself cites FRE 301, and states that "[a]ny showing that severs the link between the alleged misrepresentation and either the price received (or paid) by the plaintiff . . . will be sufficient to rebut the presumption of reliance." 485 U.S. at 248. Second, Halliburton II establishes that the Basic presumption must be rebuttable at the class certification stage. 134 S. Ct. 2398, 2414 (2014). As a consequence of these two principles, courts may not impose a burden of proof on defendants which is equal to (and certainly not one that exceeds) the plaintiffs’ ultimate burden of persuasion as to price impact. And the Basic presumption must not be construed as an insurmountable obstacle to defendants. Indeed, Goldman Sachs argues that the district court, in saying that defendants must "’demonstrate a complete absence of price impact’ with ‘conclusive evidence that no link exists,’" may have impliedly shifted the burden to defendants to disprove price impact, under what defendants characterize as a "beyond-all-doubt standard." Goldman Sachs Brief at 32-34. Further, the district court in Barclays noted that "some [courts] have recognized that Halliburton II‘s holding will not ordinarily present a serious obstacle to class certification," 312 F.R.D. at 324, and the plaintiffs have argued in their brief that the Basic presumption was in fact intended to be "virtually insurmountable," see Brief for Plaintiffs at 30, Waggoner v. Barclays PLC, No. 16-1912 (2d Cir. Aug. 29, 2016). But this interpretation would render Basic‘s express language and reference to FRE 301 a nullity, and read this holding of Halliburton II out of existence.

If the Second Circuit upholds the district courts’ decisions on this issue, it could create a split among the circuits and potentially ripen the issue for Supreme Court review.

2. Evidence Properly Considered at the Class Certification Stage

The plaintiffs in Goldman Sachs argue that any discussion of materiality or loss causation must be left for the merits stage. See Brief of Plaintiffs at 17-23, Ark. Teachers Ret. Sys. v. Goldman Sachs Grp., Inc., No. 16-250 (2d Cir. Aug. 19, 2016). However, the Supreme Court mandated that all evidence must be considered at the class certification stage, and Goldman Sachs presents a scenario in which materiality, loss causation, and price impact overlap.

As we noted in our 2016 Mid-Year Securities Litigation Update, a major issue before the Fifth Circuit in the Halliburton remand was whether a district court may consider, at the class certification stage, whether or not the corrective disclosures at issue were actually corrective. In fact, price impact and loss causation are often considered to be two sides of the same coin. See, e.g., Mark A. Perry & Kellam M. Conover, The Interrelationship Between Price Impact and Loss Causation After Halliburton I and II, 71 N.Y.U. Ann. Surv. Am. L. 189, 192 (2015). While the Fifth Circuit did not have the opportunity to rule on this issue due to the parties’ settlement, Goldman Sachs has similarly asked the Second Circuit to rule on whether a district court may consider whether or not the alleged representations at issue were immaterial as a matter of law, and thus could not have had any price impact. See Goldman Sachs Brief at 34-37. Goldman Sachs presented the additional issue, similar to an argument that was successful before the district court in the Halliburton remand, that the presumption is rebutted when the information had already been revealed to the public, to no price movement, prior to the alleged corrective disclosure dates. See id. at 50-54; see also Erica P. John Fund, Inc. v. Halliburton Co., 309 F.R.D. 251, 272-74 (N.D. Tex. 2015). The Second Circuit’s decision may be crucial to determining how courts will handle the intersection of Halliburton I, Halliburton II, and Amgen in the future, and to whether–or when–the Supreme Court will weigh in again.

B. District Court Update

The second half of 2016 was generally quiet with respect to price impact cases in the district courts. In our 2016 Mid-Year Securities Litigation Update, we discussed Burges v. Bancorpsouth, Inc., 2016 WL 1701956 (M.D. Ten. Apr. 28, 2016), in which the district court certified a class notwithstanding unrebutted evidence that the market showed no interest in the alleged misstatements. In September, the Sixth Circuit vacated the certification order and remanded the case for further consideration, concluding that "the district court briefly recounted the requirements for bringing a class action, but did not set forth the standard requiring it to rigorously analyze Plaintiffs’ claims before certifying the action as a class action." In re Bancorpsouth, Inc., 2016 WL 5714755, at *1 (6th Cir. Sept. 6, 2016). As a result, the Sixth Circuit has yet to weigh in on the questions of rebutting price impact evidence, and FRE 301 burden shifting.

We will continue to monitor cases in all courts in the upcoming new year.

IV. State Securities Suits and the PSLRA–Cyan, Inc. and FireEye Petitions for Certiorari

As we reported in our 2016 Mid-Year Update this past July, the United States Supreme Court may be on the cusp of determining whether state courts retain jurisdiction to hear class actions asserting claims under the Securities Act. Congress enacted the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act ("PSLRA") in 1995, but plaintiffs began circumventing many of the procedural reforms therein by filing in state court. Congress responded by enacting the Securities Litigation Uniform Standards Act ("SLUSA") in 1998, which preempted and provided for removal of certain class actions alleging securities claims under state law. While it would seem logical that SLUSA precludes state court jurisdiction for Securities Act class actions, this question has divided courts. The issue is of particular importance because, unlike the Exchange Act, the Securities Act bars removal for claims arising under it, making SLUSA an important avenue to federal court.

In 2011, after the California Court of Appeal held that states have concurrent jurisdiction over class actions raising federal Securities Act claims, see Luther v. Countrywide Fin. Corp., 195 Cal. App. 4th 789 (2011), Securities Act class actions began to proliferate in California state courts. Now, defendants from two separate such actions have petitioned for certiorari in the U.S. Supreme Court. In both Cyan, Inc. v. Beaver County Employees Retirement Fund, No. 15-1439 (U.S. 2016), and FireEye, Inc. v. Superior Court of California, No. 16-744 (U.S. 2016), petitioners asked the Court to determine whether, under SLUSA, state courts lack subject matter jurisdiction over class actions that allege only claims under the Securities Act. Petitioners argue that Congress enacted SLUSA to prevent state-court litigation from circumventing the PSLRA’s reforms, and that decisions upholding concurrent state-court jurisdiction subvert SLUSA’s requirement that the reforms implemented by the PSLRA have uniform application in all class actions under the Securities Act. See Cyan, Inc., at 1-2. Petitioners note that, since the Luther v. Countrywide decision, filings of class actions under the Securities Act in California state courts have risen 1,400 percent. See id. at 2.

As several securities law professors state in their brief of amici curiae in support of the Cyan, Inc. petitioners, the question presented in both petitions is unique. Brief of Amici Curiae Law Professors in Support of Petitioners, No. 15-1439 (U.S. 2016). It has split federal district courts addressing it on motions to remand in cases that have been removed to federal court, but because remand orders are not appealable, federal circuit courts have not been able to address this issue. That makes this issue a strong candidate for Supreme Court review.

The Supreme Court has not made a decision on either petition, but in October, the Court invited the Acting Solicitor General to file a brief expressing the views of the United States on the Cyan petition, which was filed in May 2016 (FireEye filed its petition in December 2016). [1] According to one study, the Court has granted certiorari in approximately 34% of cases in which it has made such an invitation in recent history. David C. Thompson & Melanie F. Wachtell, An Empirical Analysis of Supreme Court Certiorari Petition Procedures: The Call for Response and the Call for the Views of the Solicitor General, 16 Geo. Mason L. Rev. 237, 276 (2009).

We will continue to monitor developments in this area and report on any updates in our 2017 Securities Litigation Mid-Year Review.

V. Demand and Collateral Estoppel Developments

A. Delaware Court Of Chancery Further Explores Contours Of The Application Of Collateral Estoppel To Prior Judgments Of Demand Futility

As discussed in our 2016 Mid-Year Securities Litigation Update, two recent decisions from the Delaware Court of Chancery–both written by Chancellor Andre Bouchard–applied and expanded upon the Delaware Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Pyott v. Lampers, 74 A.3d 612, 618 (Del. 2013), to hold that a federal stockholder derivative plaintiff’s election not to use books and records procedures under Section 220 of Delaware’s General Corporation Law (a "Section 220" action) did not bar the application of preclusion doctrines in subsequent stockholder derivative suits. See Laborers’ Dist. Council Constr. Indus. Pension Fund v. Bensoussan, 2016 WL 3407708 (Del. Ch. June 14, 2016) ("Lululemon"); In re Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. Deriv. Litig., 2016 WL 2908344 (Del. Ch. May 13, 2016) ("Wal-Mart"). The Delaware Supreme Court held argument on Wal-Mart on December 14, 2016, and heard argument on Lululemon on January 18, 2017.

While the Wal-Mart and Lululemon decisions were pending on appeal, Vice Chancellor Glasscock issued a decision further examining the bounds of collateral estoppel analysis in the context of a prior finding that demand would not have been futile. In In re Duke Energy Corp. Derivative Litigation, 2016 WL 4543788 (Del. Ch. Aug. 31, 2016), Vice Chancellor Glasscock determined the preclusive effect of a demand futility ruling issued by a North Carolina state court, applying North Carolina preclusion law as required under Pyott and federal precedent. Although North Carolina courts had not yet decided whether stockholder plaintiffs are in privity for purposes of determining the collateral estoppel effect of a demand futility ruling, Vice Chancellor Glasscock ruled that North Carolina courts would follow the decisions of the "numerous jurisdictions" holding that such stockholder plaintiffs are in privity. Id. at *11. In Duke Energy, as in Wal-Mart and Lululemon, the Court of Chancery determined that the prior non-Delaware action and the subsequent Delaware action were based on "the same core set of facts." Id. at *9.

However, Vice Chancellor Glasscock found a significant difference affecting his analysis of the identity of issues in the Duke Energy matter: although the decision on demand futility in the North Carolina action would bar re-litigation of the demand futility question as to the Delaware plaintiffs’ claims for waste and breach of fiduciary duty arising from the directors’ decisions to hire and then immediately fire a CEO, the subsequent Delaware action pleaded causes of action relating to allegedly misleading disclosures not considered in the North Carolina matter. Id. at *12. Therefore, the prior and subsequent cases were not "’grounded on the same gravamen of the wrong,’ and the issues presented [we]re not identical." Id. at *12-13 (quoting Bensoussan, 2016 WL 3407708, at *9). In ruling that collateral estoppel would only apply to re-litigation of the demand futility question as to those theories addressed in the prior North Carolina action, Vice Chancellor Glasscock distinguished the Court of Chancery decisions in Wal-Mart and in Asbestos Workers Local 42 Pension Fund v. Bammann, 2015 WL 2455469 (Del. Ch. May 21, 2015), aff’d 132 A.3d 749 (Del. 2016), on the grounds that in those cases, the prior and subsequent sets of plaintiffs alleged the same core theories and underlying facts, and the factual allegations differed only in terms of quantity or persuasiveness. Id. at *13 & n.166. Decisions in the Wal-Mart and Lululemon appeals are expected to issue by early spring 2017.

VI. Delaware Derivative Litigation Developments

In the past six months, the Delaware Supreme Court has rendered decisions on the pleading requirements for demand excusal as well as the distinction between direct and derivative claims in the limited partnership context. We also saw the Delaware courts continue to emphasize the high pleading bar stockholder plaintiffs face in post-closing damages cases. Additionally, we continued to see numerous appraisal litigation matters, including decisions in which the appraised value exceeded the transaction price.

A. Delaware Supreme Court Reverses Dismissal of Derivative Action Involving Controlling Stockholder, Finding Plaintiff Adequately Pleaded Demand Excusal

In Sandys v. Pincus, 2016 WL 7094027 (Del. Dec. 5, 2016), the Delaware Supreme Court, sitting en banc, clarified how particularized a stockholder’s allegations must be in a derivative action to plead demand excusal under Delaware Rule 23.1. Plaintiff, suing derivatively on behalf of Zynga, Inc., alleged that top officers–including the former CEO, who was the controlling stockholder of Zynga–and certain directors breached their fiduciary duties by selling stock in advance of earnings announcements that ultimately caused Zynga’s stock price to decline, and that all of the directors breached their fiduciary duties by approving these sales. Defendants moved to dismiss under Rule 23.1, arguing that the plaintiff failed to make a pre-suit demand and failed to plead that demand was excused. Under the Delaware Supreme Court’s decision in Rales v. Blasband, 634 A.2d 927 (Del. 1993)–which the court applied in this case–to plead demand excusal a plaintiff must make "particularized factual allegations that ‘create a reasonable doubt that . . . the board of directors could have properly exercised its independent and disinterested business judgment in responding to a demand.’" Sandys, 2016 WL 7094027, at *3 (quoting Rales, 634 A.2d at 934). The trial court found that the plaintiff failed to plead particularized facts sufficient to call into question the independence of the directors, and dismissed the case. Sandys v. Pincus, 2016 WL 769999, at *18 (Del. Ch. Feb. 29, 2016). The plaintiff appealed.

The Delaware Supreme Court reversed the trial court’s decision. In holding that demand was excused, the Supreme Court focused on two theories advanced by the plaintiff. First, the Supreme Court held that the plaintiff’s allegation that one director was not independent because this director co-owned a plane with the former CEO created "an inference . . . that [the] director cannot act impartially." Sandys, 2016 WL 7094027, at *4. The court reasoned that "owning an airplane together is not a common thing, and suggests that [the families of this director and of the former CEO] are extremely close to each other and are among each other’s most important and intimate friends." Id. In holding that this allegation was sufficient, the court emphasized that while a plaintiff’s pleading burden "is elevated in the demand excusal context, that standard does not require a plaintiff to plead a detailed calendar of social interaction" in order to plead lack of independence. Id.

Second, the court held that two directors who were partners at a venture capital fund that controls 9.2% of Zynga’s equity were not independent for Rule 23.1 purposes. Id. at *5. The court’s analysis primarily relied on the fact that Zynga’s board had determined that these directors did "not qualify as independent directors under the NASDAQ Listing Rules," even though there was no allegation as to why the board had made this decision. Id. The court also relied on allegations that these directors had various business ties with Zynga insiders, though there was no allegation about how material the ties were to the directors. Id. The court reasoned that these intertwining, "mutually beneficial ongoing business relationships"–relationships that could lead to additional "economic opportunities" given the nature of the relationship–created a reasonable doubt as to whether the two directors could act impartially. Id. at *5-7. Notably, though, the court suggested that its analysis was, in part, driven by the fact that this case involved a controlling stockholder. Thus, similar allegations might not be sufficient to plead demand excusal outside of the controlling stockholder context.

Separate from its discussion of how specific allegations must be to plead demand excusal, the court also took time to emphasize the importance of pre-suit investigations by derivative plaintiffs. Id. at *3. The court admonished the plaintiff here for failing to conduct a diligent pre-suit investigation by requesting books and records relating to the independence of the Zynga directors. Id. The court also promoted utilizing internet research as part of a pre-suit investigation, and suggested that it could take judicial notice of online newspaper and journal articles, "postings on official company websites," and "information on university websites." Id.

B. Delaware Supreme Court Finds That Claims Against General Partner of Master Limited Partnership Are Derivative

In El Paso Pipeline GP Co. v. Brinckerhoff, 2016 WL 7380418 (Del. Dec. 20, 2016) ("El Paso II"), the Delaware Supreme Court made clear that the principles for determining whether a claim is direct or derivative apply to disputes involving limited partnerships, and indicated that claims that the general partner has engaged in self-dealing transactions at the expense of limited partners will often, if not always, be deemed derivative. In the same case, the court reinforced that derivative claims are extinguished by the consummation of mergers or acquisitions, even if there is evidence that the defendants acted in bad faith and the plaintiff’s claims would have been meritorious. Id. at *2.

In the case, a master limited partnership ("MLP") purchased assets from the parent company of its general partner. Id. at *1. The plaintiff, a limited partner, brought a derivative action on behalf of the MLP, alleging that the general partner breached the limited partnership agreement by acting in bad faith and causing the MLP to overpay substantially for the assets. The MLP was subsequently acquired. Id. After a trial in the Court of Chancery, Vice Chancellor Laster found that the general partner was liable for $171 million in damages and that the plaintiff could recover even though the MLP had been acquired because the plaintiff’s claims were also direct in nature. In re El Paso Pipeline Partners, L.P. Derivative Litig., 132 A.3d 67, 132 (Del. Ch. 2015). Vice Chancellor Laster reasoned that (i) a limited partner’s suit to enforce the limited partnership agreement sounds in contract and is, therefore, direct in nature, and (ii) the limited partners suffered an injury distinct from the MLP, namely the reallocation of value from the limited partners to the general partner. In re El Paso Pipeline Partners, L.P. Derivative Litig., 132 A.3d at 86, 104.

The Delaware Supreme Court reversed in El Paso II, holding that the limited partner’s claim was derivative and had been extinguished by the acquisition of the MLP. 2016 WL 7380418, at *13. First, the court rejected the notion that every claim sounding in contract is, by default, a direct claim. Id. at *9-10. Because the plaintiff had alleged the breach of a contractual duty that was owed to the partnership, the court applied the well-known standard from Tooley v. Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette, Inc., 845 A.2d 1031 (Del. 2004), for determining whether a corporate law claim is direct or derivative, analyzing whether it was the partnership or the limited partners that (i) suffered the harm and (ii) would receive the recovery. El Paso II, 2016 WL 7380418, at *9-10. Second, the court held that the harm alleged in the plaintiff’s complaint solely affected the partnership and was, therefore, derivative in nature. Id. In doing so, the court declined to expand on Delaware case law, notably Gentile v. Rossette, 906 A.2d 91 (Del. 2006), holding that a controlling stockholder’s improper transfer of economic value and voting power could give rise to a direct claim. El Paso II, 2016 WL 7380418, at *9-10. While the court distinguished Gentile on the ground that no transfer of voting power had occurred in El Paso II, Chief Justice Strine, in a concurring opinion, argued that Gentile should be overruled because it is inconsistent with Delaware case law holding that dilution claims–in which an entity has issued equity in exchange for allegedly inadequate consideration–are quintessential examples of derivative claims. Id. at *14. Finally, the court held that the limited partner’s derivative claims were extinguished by the subsequent acquisition of the MLP, and noted that if it allowed cases like this to proceed post-closing it would "raise the overall transaction costs and barriers to mergers." Id. at *2.

C. Recent Delaware Decisions Emphasize The Difficulty Of Pleading A Post-Closing Damages Case

During the past year, Delaware courts have demonstrated increasing skepticism of post-closing suits for damages, particularly those suits asserting post-closing disclosure claims. This trend began in earnest in 2015 with the Delaware Supreme Court’s decision in Corwin v. KKR Financial Holdings LLC, 125 A.3d 304, 314 (Del. 2015), which firmly established the application of the business judgement standard of review for transactions approved by a non-coerced, fully informed stockholder vote. Under that standard, plaintiffs face significant hurdles in overcoming a motion to dismiss. Indeed, Vice Chancellor Glasscock mused in Nguyen v. Barrett, 2016 WL 5404095 (Del. Ch. Sept. 28, 2016), that it would be "salutary" if disclosure claims "pled but not pursued pre-close" were deemed waived by rule because the "preferred method for vindicating truly material disclosure claims is to bring them pre-closing, at a time when the Court can insure an informed vote." Id. at *7. Several other decisions from 2016 have similarly emphasized the uphill battle that plaintiffs face if they wait to bring their claims after the transaction in question has occurred. See, e.g., Singh v. Attenborough, 137 A.3d 151 (Del. 2016) (en banc) (business judgment deference given to transactions approved by a fully informed stockholder vote); In re Volcano Corp. Stockholder Litig., 143 A.3d 727, 738 (Del. Ch. 2016) ("business judgment rule irrebuttable" when approved by majority of "fully informed, uncoerced, disinterested stockholders"); Larkin v. Shah, 2016 WL 4485447, at *7 (Del. Ch. Aug. 25, 2016) (applying the "irrebuttable business judgment rule . . ., a holding that extinguishes all challenges to the merger except those predicated on waste").

D. In Appraisal Litigation, Delaware Courts Looked Beyond Transaction Price

Delaware appraisal litigation continued to be active during the second half of 2016. Departing from the trend we saw in 2015, the Delaware Court of Chancery awarded an increase over the transaction price in the majority of cases decided during this period. For example, in In re ISN Software Corp. Appraisal Litigation, 2016 WL 4275388 (Del. Ch. Aug. 11, 2016), Vice Chancellor Glasscock used a discounted cash flow analysis to determine the fair value of stock held by minority stockholders of a private corporation, whose shares were cashed out by the controlling stockholder. Id. at *1. The court concluded that the fair value of the minority stockholders’ shares was $98,783, or more than double the $38,317 per-share transaction price. Id. And in Dunmire v. Farmers & Merchants Bancorp of Western Pennsylvania, Inc., 2016 WL 6651411 (Del. Ch. Nov. 10, 2016), Chancellor Bouchard awarded a 10.6% increase over the transaction price in an appraisal action arising from the sale of a small community bank. Id. at *16. The court held that the transaction price was not probative of fair value because the merger was not the product of an auction and was undertaken at the insistence of stockholders who controlled both the target and acquiring corporations. Id. at *7. The court also declined to rely on the analyses of comparable transactions and comparable companies proffered by the parties’ experts, and instead placed 100% weight on the results of a discounted net income analysis. Id. at *16.

In contrast, in Merion Capital L.P. v. Lender Processing Services, Inc., 2016 WL 7324170 (Del. Ch. Dec. 16, 2016), Vice Chancellor Laster gave 100% weight to the transaction price in determining the subject company’s fair value. Id. at *33. The court noted that the company conducted a robust sale process that "created credible competition among heterogeneous bidders during the pre-signing phase," all of whom received equal access to information about the company and had the opportunity to conduct due diligence, and there was no evidence of collusion or unjustified favoritism towards the winning bidder. Id. at *18. After the merger agreement was signed, no party came forward with a topping bid, and the company’s financial performance declined relative to the projections that had been provided to prospective bidders. Id. at *24. The court also conducted a discounted cash flow analysis that resulted in a valuation within 3% of the transaction price–a fact that the court found "comforting" in its decision to defer to the transaction price. Id. at *33.

[1] Cyan, Inc. v. Beaver County Employees Retirement Fund, SCOTUSblog,http://www.scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/cyan-inc-v-beaver-county-employees-retirement-fund/ (last visited Dec. 28, 2016).

The following Gibson Dunn lawyers assisted in the preparation of this client update: Jon Dickey, Monica Loseman, Mark Perry, Ethan Dettmer, Matt Kahn, Alex Mircheff, Brian Lutz, Lisa Umans, Jefferson Bell, Lloyd Kim, Lissa Percopo, John Avila, Jacob Rierson, Jenni Rosenberg, Michael Kahn and Noah Stern.

Gibson Dunn lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these developments. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, or any of the following members of the Securities Litigation Practice Group Steering Committee:

Meryl L. Young – Co-Chair, Orange County (949-451-4229, [email protected])

Robert F. Serio – Co-Chair, New York (212-351-3917, [email protected])

Jonathan C. Dickey – New York/Palo Alto (212-351-2399, 650-849-5370, [email protected])

Thad A. Davis – San Francisco (415-393-8251, [email protected])

George H. Brown – Palo Alto (650-849-5339, [email protected])

Jennifer L. Conn – New York (212-351-4086, [email protected])

Ethan Dettmer – San Francisco (415-393-8292, [email protected])

Barry R. Goldsmith – New York (212-351-2440, [email protected])

Mark A. Kirsch – New York (212-351-2662, [email protected])

Gabrielle Levin – New York (212-351-3901, [email protected])

Monica K. Loseman – Denver (303-298-5784, [email protected])

Brian M. Lutz – San Francisco/New York (415-393-8379/212-351-3881, [email protected])

Jason J. Mendro – Washington, D.C. (202-887-3726, [email protected])

Alex Mircheff – Los Angeles (213-229-7307, [email protected])

Robert C. Walters – Dallas (214-698-3114, [email protected])

Aric H. Wu – New York (212-351-3820, [email protected])

© 2017 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.