July 20, 2017

The first half of 2017 brought with it a nearly unprecedented rate of new filings (a pace few predicted), as well as several important developments in the securities laws. Among other things, the U.S. Supreme Court decided to weigh in on several key issues, including state court jurisdiction over Securities Act class actions and whether omissions of disclosures under Item 303 of Regulation S-K are actionable under Section 10(b). We also highlight a key change in public company audit standards that may very well play a role in future securities litigation, as well as new decisions interpreting and applying Omnicare and Halliburton II, and highlights in Delaware litigation and notable derivative cases.

The mid-year update highlights what you most need to know in securities litigation developments and trends for the first half of 2017:

- The Supreme Court granted certiorari in Cyan to resolve whether state courts have subject matter jurisdiction over class actions brought under the Securities Act of 1933.

- The Supreme Court also granted certiorari in Leidos to decide whether omission of a disclosure required by Item 303 of the SEC’s Regulation S-K is actionable under Section 10(b) and Rule 10b–5 of the federal securities laws.

- We analyze the Supreme Court’s opinion in CalPERS, holding that the filing of a putative class action does not toll the statute of repose in the Securities Act of 1933.

- We discuss the potential effect on public company disclosures of the PCAOB’s newly adopted auditing standard requiring the auditor’s discussion and documentation of “Critical Auditing Matters.”

- We analyze the ongoing effect of the Supreme Court’s Omnicare decision on antifraud claims, including claims under Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5.

- We highlight significant post-Haliburton II opinions, including notable cases pending in the Second, Fifth, and Sixth Circuits.

- We examine the developing effect of the Delaware Court of Chancery’s criticism of disclosure-only settlements in Trulia both in Delaware and in other jurisdictions.

- Finally, we explain important developments in Delaware courts, including the Court of Chancery’s application of Corwin, its assessment of the deal price in appraisal litigation, and its treatment of Caremark claims.

We highlight these and other notable developments in securities litigation in our 2017 Mid-Year Securities Litigation Update below.

I. Filing and Settlement Trends

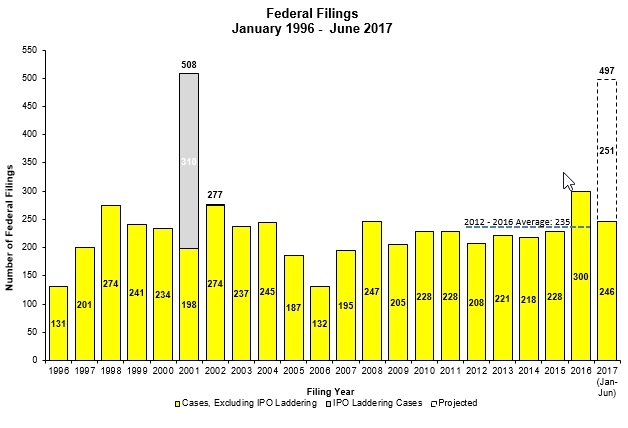

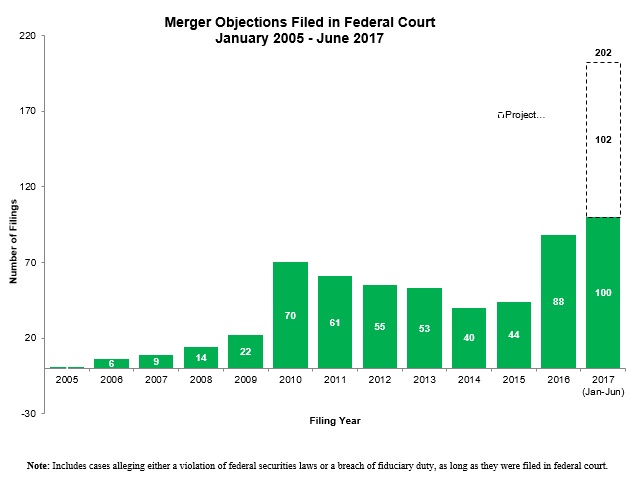

In the first half of 2017, new securities class actions filings are on pace to significantly exceed annual filing rates in previous years. According to a newly-released NERA Economic Consulting study (“NERA”),[1] 246 cases were filed in the first half of this year, compared to an average number of 235 cases filed annually over the last five years. At this pace, filings for 2017 could reach approximately 497 total cases. The only year in the past two decades that remotely compares is 2001, but that year included a significant number of so-called “IPO laddering” cases. While a similar singular explanation for the marked increase in filings in 2017 has not yet emerged, it appears so-called “merger objection” cases are a driving force. NERA projects that the number of merger objection cases filed in federal court in 2017 will be significantly greater than 2016, representing approximately 1 in 5 securities cases filed in the federal courts in 2017.

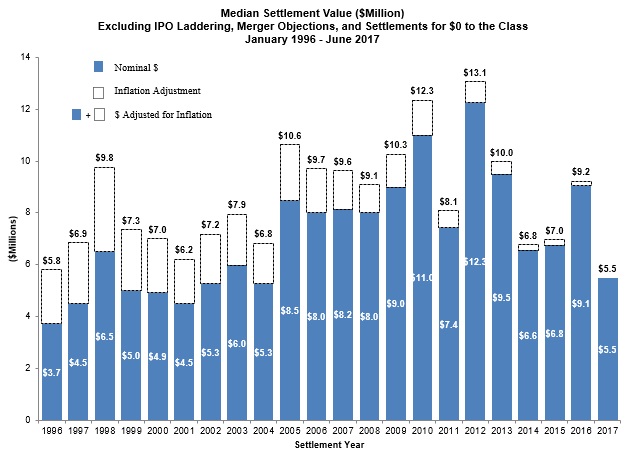

The other big takeaway from the data may be more welcome news: while the number of filings is up, both average and median settlement amounts are down sharply in the first half of 2017. Nearly 70% of settlements in the first half of 2017 were under $10 million, while only 6% were over $50 million. Most significantly, median settlement amounts as a percentage of investor losses continue to reflect a pattern that has persisted for decades. In the last fifteen years, median settlement amounts have never exceeded 3% of total alleged investor losses. In the first half of 2017, that percentage is 2.6%.

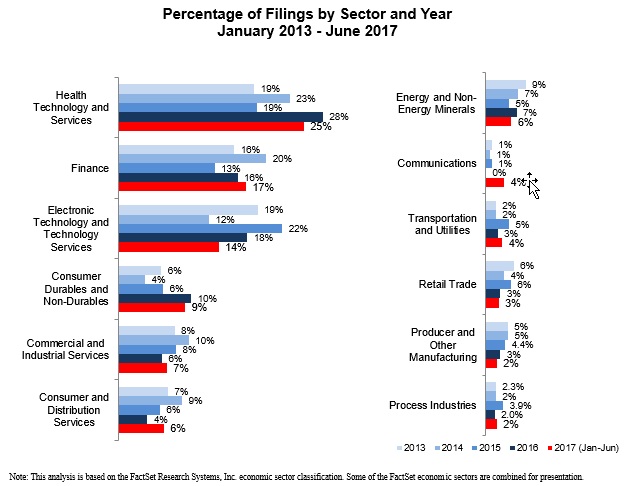

The industry sectors most frequently sued in 2017 continue to be healthcare (25% of all cases filed), finance (17%), and tech (14%). Of these three sectors, the percentage of cases filed against tech companies actually reflects a significant downward trend, from 22% in 2015 to 14% so far this year.

A. Filing Trends

Figure 1 below reflects filing rates for the first half of 2017 (all charts courtesy of NERA). Two hundred and forty-six cases have been filed so far this year, annualizing to 497 cases. This figure does not include the many class suits filed in state courts or the increasing number of state court derivative suits, including many such suits filed in the Delaware Court of Chancery. Those state court cases represent a “force multiplier” of sorts in the dynamics of securities litigation today.

Figure 1:

B. Mix of Cases Filed in First Half of 2017

1. Filings by Industry Sector

New 2017 case filings reflect not only a steady decrease in the percentage of cases against tech companies from a peak in 2014, but also an increase in the percentage of cases filed against communications companies. Following a significant bump in the percentage of cases filed against healthcare companies last year, new 2017 filings reflect a decline in this sector. See Figure 2 below.

Figure 2:

2. Merger Cases

As shown in Figure 3 below, 100 “merger objection” cases have been filed in federal court in the first half of 2017 alone—a number that already exceeds the total number filed in any year in the past decade. This annualizes to 202 cases, which would more than double the number of such cases filed in 2016, and more than quadruple the number filed in 2014 and 2015. Note that this statistic only tracks cases filed in federal courts. Most M&A litigation occurs in state court, particular the Delaware Court of Chancery. But as discussed below and in our prior updates, the Delaware Court of Chancery recently announced that the much-abused practice of filing an M&A case followed shortly by an agreement on “disclosure only” settlement is just about at an end, and with it, we anticipate a decline in the total number of M&A suits filed in that court.

Figure 3:

C. Settlement Trends

As Figure 4 shows, median settlements were $5.5 million in the first half of 2017, significantly lower than median amounts in the last dozen years. In any given year, of course, the statistics can mask a number of important factors that contribute to any particular settlement value, such as (i) the amount of D&O insurance; (ii) the presence of parallel proceedings, including government investigations and enforcement actions; (iii) the nature of the events that triggered the suit, such as the announcement of a major restatement; (iv) the range of provable damages in the case; and (v) whether the suit is brought under Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act or Section 11 of the Securities Act. Median settlement statistics also can be influenced by the timing of large settlements, any one of which can skew the numbers, but those big settlements have been markedly absent so far this year. In the first half of 2017, the percentage of settlements above $100 million decreased sharply from 15% to 6% of all settlements. At the same time, the percentage of settlements below $10 million increased from 51% to 68%.

Figure 4:

II. U.S. Supreme Court Developments

A. State Securities Suits and the PSLRA—Supreme Court Grants Petition in Cyan, Inc.

On June 27, 2017, the Supreme Court granted the petition for certiorari in Cyan, Inc. v. Beaver County Employees Retirement Fund, No. 15-1439 (U.S. 2016). As discussed in our 2016 Year-End Update, the case promises to resolve whether state courts lack subject matter jurisdiction over class actions alleging claims under the Securities Act of 1933.

Shortly after Congress enacted the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act (“PSLRA”) in 1995, plaintiffs began circumventing its requirements by filing in state court. Congress responded in 1998 by enacting the Securities Litigation Uniform Standards Act (“SLUSA”), which preempted and provided for the removal of class actions alleging securities claims under state law. SLUSA also amended language in the Securities Act that provided for concurrent federal- and state-court jurisdiction over 1933 Act cases. As amended, the Securities Act provides for concurrent jurisdiction “except as provided in section 77p of this title with respect to covered class actions.” 15 U.S.C. § 77v(a).

While it would seem logical that SLUSA’s amendment precludes state court jurisdiction over “covered class actions” asserting claims under the Securities Act, the issue has sharply divided district courts. As several law professors note in their brief of amici curiae in support of the Cyan petitioners, a majority of district courts in the Second, Third, Fourth, Fifth, and Tenth circuits have held that SLUSA grants federal courts exclusive jurisdiction over Securities Act class actions and denied remand where defendants have removed to federal court, whereas the majority of district courts in the First, Seventh, Ninth, and Eleventh circuits have held the opposite and remanded. See Brief of Amici Curiae Law Professors in Support of Petitioners at 5-6. Moreover, because remand orders are rarely reviewable, no federal appellate court has had the opportunity to clarify the issue or provide some semblance of uniformity among district courts.

Adding to the chaos, the California Court of Appeal held in 2011 that states have concurrent jurisdiction over Securities Act class actions. See Luther v. Countrywide Fin. Corp., 195 Cal. App. 4th 789 (2011). Since that decision, Securities Act class action filings have skyrocketed in California state court. As the Cyan petitioners note, between 1998 and 2011, only six class actions alleging violations of Section 11 of the 1933 Act were filed in California state court. See Petitioners’ Br. at 8 n.6. By contrast, 14 were filed in 2015 alone. Id. And in 2016, 18 were filed—five times the number of such filings in 2011. See https://www.cornerstone.com/Publications/Research/Section-11-Cases-Filed-in-California-State-nbsp;Co.

In October 2016, the Supreme Court invited the Acting Solicitor General to respond to the petition. On May 23, 2017, the Acting Solicitor General filed an amicus curiae brief on behalf of the United States. The Acting Solicitor General agreed that the Supreme Court should grant the petition, but disagreed with the Cyan petitioners on the merits, arguing that SLUSA does not preclude state-court jurisdiction over Securities Act claims. See Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae at 6. Instead, the Acting Solicitor General took the position that SLUSA’s goals can be achieved by permitting removal of Securities Act suits “like this one.” Id.

In June 2017, the Cyan petitioners and respondents filed supplemental briefs responding to the Acting Solicitor General. In their supplemental brief, the Cyan petitioners downplayed their disagreement with the United States on the merits of the issue presented. See Petitioners’ Supp. Br. at 1-2. By contrast, the Cyan respondents took the United States to task for raising an issue—namely, removability—that was “not encompassed by the Question Presented” and was “outside [the] Court’s jurisdiction.” See Respondents’ Supplemental Br. at 1. The Cyan respondents also argued that the Acting Solicitor General’s interpretation was “both irreconcilable with the statutory text and precluded by Kirchner [v. Putnam Funds Trust, 547 U.S. 633 (2006)].” Id. at 11.

The case will be briefed this summer and will likely be argued by the end of the year. A decision is expected by the end of the 2017 Term in June 2018. We will continue to monitor developments in this area and report on any updates in our 2017 Year-End Securities Litigation Update.

B. Leidos: The Supreme Court Takes Up Whether Omissions Of Information Required To Be Disclosed By Item 303 Are Actionable Under Section 10(b)

On March 27, 2017, the Supreme Court granted certiorari in Leidos, Inc. v. Indiana Public Retirement System, No. 16-581 (“Leidos“), to decide whether omission of a disclosure required by Item 303 of the SEC’s Regulation S-K, 17 C.F.R. § 229.303 (“Item 303”), is actionable under Section 10(b) and Rule 10b–5 of the federal securities laws.[2] This question is noteworthy because the Supreme Court has long held that “[s]ilence, absent a duty to disclose, is not misleading under Rule 10b–5.” Basic, Inc. v. Levinson, 485 U.S. 224, 239 n.17 (1988) (internal quotation marks omitted). Indeed, the Supreme Court has held that a duty to disclose under Section 10(b) and Rule 10b–5 arises only when an omission would render an affirmative statement misleading or would violate a special duty founded in a relationship of trust and confidence; thus, companies can “control what they have to disclose . . . by controlling what they say to the market.” Matrixx Initiatives, Inc. v. Siracusano, 563 U.S. 27, 44-45 (2011). Nevertheless, the Second Circuit recently held in Indiana Public Retirement System v. SAIC, Inc., 818 F.3d 85, 94-95 (2d Cir. 2016) (“SAIC“), that an omission under Item 303 can give rise to Section 10(b) and Rule 10b–5 liability. This opens up a Circuit split with the Ninth and Third Circuits, which have held that violations of Item 303 are not actionable under Section 10(b) and Rule 10b–5.

The procedural history of SAIC is illuminating as it provides the first opportunity for the Supreme Court to visit this Circuit split. In SAIC, plaintiffs brought claims in the Southern District of New York under, among other things, Section 10(b) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, alleging that Leidos’s predecessor, SAIC, Inc., made material omissions by failing to disclose federal and state investigations into the company’s unlawful overbilling practices in connection with a government contract with the City of New York. SAIC, 818 F.3d at 88. Plaintiffs charged that SAIC should have disclosed this allegedly known and potentially significant exposure in its March 2011 Form 10-K because Item 303 requires that such disclosures “[d]escribe any known trends or uncertainties that have had or that the registrant reasonably expects will have a material favorable or unfavorable impact on net sales or revenues or income from continuing operations,” 17 C.F.R. § 229.303(a)(3)(ii). Id.

The District Court dismissed this claim for failure to plead facts establishing that “management (1) had knowledge that the company could be implicated in the . . . fraud or (2) could have predicted a material impact on the company.” In re SAIC, Inc. Securities Litigation, No. 12 Civ. 1353 (DAB), 2014 WL 407050, at *4 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 30, 2014). Thus, while not disagreeing with the proposition that an Item 303 omission could be actionable under Section 10(b) and Rule 10b–5, the District Court found insufficient allegations that SAIC had a disclosure obligation under Item 303 with the facts as pled.

On appeal, the Second Circuit vacated the portion of the District Court’s ruling related to Item 303 and remanded it for further proceedings. SAIC, 818 F.3d at 88. The Second Circuit agreed that Item 303 requires the registrant to disclose only those trends, events, or uncertainties that it “actually knows of” (as opposed to those that it “should have known”) when it files with the SEC, but concluded that SAIC was allegedly “aware of the fraud” at the time of the report. Id. at 94. In deciding that this purported Item 303 omission could be actionable under Section 10(b) and Rule 10b–5, the Second Circuit relied heavily on its 2015 decision in Stratte-McClure v. Morgan Stanley, 776 F.3d 94, 100 (2d Cir. 2015), simply citing to its past holding that “a failure to make a required Item 303 disclosure . . . is indeed an omission that can serve as the basis for a Section 10(b) securities fraud claim” so long as the omission is material. SAIC, 818 F.3d at 95 n.7. The Stratte-McClure court had reasoned that, due to “the obligatory nature of these regulations, a reasonable investor would interpret the absence of an Item 303 disclosure to imply the nonexistence of ‘known trends or uncertainties,'” rendering the existing statement misleading. Stratte-McClure, 776 F.3d at 102. Note that dismissal of Stratte-McClure was affirmed on other grounds (failure to plead facts showing that the violation was reckless), and thus did not provide a ripe opportunity for the Supreme Court to review the Item 303 issue.

The Second Circuit’s recent decision in SAIC puts it in conflict with the Ninth Circuit and, potentially, the Third Circuit on the Item 303 issue. In 2014, the Ninth Circuit in In re NVIDIA Corp. Securities Litigation, 768 F.3d 1056 (9th Cir. 2014), held that “Item 303 does not create a duty to disclose for purposes of Section 10(b) and Rule 10b–5.” In so holding, the Ninth Circuit parsed a 2000 Third Circuit decision authored by then-Circuit Judge Samuel Alito, Oran v. Stafford, 226 F.3d 275, 287-88 (3d Cir. 2000), where the Third Circuit found that the SEC’s test for disclosure under Item 303 “varies considerably” from the Supreme Court’s materiality test for securities fraud set out in Basic Inc. v. Levinson, 485 U.S. 224, 237 (1988). Basic held that materiality for contingent or speculative information or events depends on “a balancing of both the indicated probability that the event will occur and the anticipated magnitude of the event in light of the totality of the company activity.” Id. (internal quotation marks omitted). Thus a “violation of the disclosure requirements of Item 303 does not lead inevitably to the conclusion that such disclosure would be required under Rule 10b–5. Such a duty to disclose must be separately shown.” Oran, 226 F.3d at 288 (internal quotation marks omitted). The Ninth Circuit focused on the distinction highlighted in Oran, noting that “[m]anagement’s duty to disclose under Item 303 is much broader than what is required under the standard pronounced in Basic,” and went on to hold that Item 303 disclosures did not, standing alone, rise to the materiality level required for Section 10(b) liability. NVIDIA, 768 F.3d at 1055.

The circuit split teed up for resolution by the Supreme Court in Leidos is particularly significant since the Second and Ninth Circuits together handle more federal securities cases than the rest of the circuits combined. And the stakes in Leidos are high. Victory for plaintiffs-respondents could in effect create a new private right of action under Item 303 and expand federal securities fraud claims. Public companies would also have to make increased numbers of judgment calls in their SEC filings about whether to identify any potentially material “trend, demand, commitment, event or uncertainty,” SAIC, 818 F.3d at 95, and could face an increased threat of securities fraud cases regardless of what judgment calls are made. On the other hand, Leidos comes before a Supreme Court that has been disinclined in recent years to expand private rights of action in the securities context, and it is unclear what impact, if any, then-Judge Alito’s role authoring the skeptical Oran v. Stafford decision will have on the Supreme Court’s analysis and decision.

Argument in Leidos is expected to be set for October 2017, and a decision could issue in the first half of 2018. We will continue to monitor the appeal and any related Circuit Court decisions in future updates.

C. CalPERS: Statutes of Repose Cannot be Tolled

In CalPERS v. ANZ Securities Inc., No. 16-373 (June 26, 2017) (“CalPERS“), the Supreme Court held that the filing of a putative class action does not toll the statute of repose in the Securities Act of 1933. The Court’s decision resolved a longstanding circuit split, described in our 2014 Year-End Securities Litigation Update, over whether the class action tolling doctrine of American Pipe & Construction Co. v. Utah, 414 U.S. 538 (1974) (“American Pipe“) applied to the 1933 Act’s statute of repose.

Section 11 of the 1933 Act provides a private right of action for misstatements and omissions in registration statements and certain other filings. Section 13 of the Act includes a two-part provision governing the deadline for bringing such suits: they must be filed “within one year after the discovery of the untrue statement or omission,” but “[i]n no event … more than three years after the security was bona fide offered to the public.”

In CalPERS, a putative class action was filed within both the one-year and three-year limits, but the individual plaintiff opted out and filed suit more than three years after the securities were issued. CalPERS argued that its claim was timely under American Pipe, which held that the filing of a putative class action generally tolls the statute of limitations applicable to the claims of would-be class members until class certification is decided. If certification is denied, former members of the proposed class have the remaining limitations period within which to file individual suits or motions to intervene in a pending suit. Crown, Cork & Seal Co. v. Parker, 462 U.S. 345 (1983). The district court, however, dismissed CalPERS’ complaint as untimely and the Second Circuit affirmed, holding that because the outside limit in Section 13 is a statute of repose, not a statute of limitations, it is not subject to equitable tolling under American Pipe.

The Supreme Court affirmed, confirming that the three-year deadline in Section 13 of the Securities Act is a statute of repose and not subject to equitable tolling. Slip op., at 16. Writing for a 5-4 majority, Justice Kennedy explained that statutes of limitations and statutes of repose are different. The former run from accrual, or “when the plaintiff can file suit and obtain relief,” while the latter run from “the date of the last culpable act or omission.” Slip op. at 5 (quotations omitted). Crucially, “statutes of repose are not subject to equitable tolling” by the courts because they implement an “unqualified” legislative decision to set a “specific time beyond which a defendant should no longer be subjected to protracted liability.” Id. at 8 (quotation omitted). Statutes of limitation, in contrast, can be equitably tolled.

After examining the history and structure of the Securities Act’s timely filing provision, the Court determined that the one-year limit is a statute of limitations while the three-year limit is a statute of repose. Slip op. at 4-7. Congress commonly employs both approaches in a statute, “giving leeway to a plaintiff who has not yet learned of a violation,” while “protect[ing] the defendant from an interminable threat of liability.” Id. at 6. The three-year limit in the Securities Act, the Court explained, is the outer bound of private liability.

Because it clarifies the nature of American Pipe tolling and declines to expand that doctrine beyond its existing boundaries, CalPERS should bring helpful stability, predictability, and finality to securities litigation.

III. Potential New PCAOB Standards: CAMs and What They May Mean to Issuers

Over the next few years, we may witness a significant change in how public companies disclose certain information to the market and address litigation risk—if the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board’s newly adopted auditing standard, released on June 1, 2017 and available here, is approved by the SEC and goes into effect. The proposed new standard still has go to through the SEC notice-and-comment process and has not obtained the SEC’s approval.

We discussed the Board’s new auditing standard in our June 2, 2017 client alert. By way of background, today’s auditor reports on companies’ financial statements opine on whether the audited company’s financial statements, taken as a whole, are fairly presented in all material aspects in accordance with the applicable financial reporting framework. Deeming this binary pass/fail model not sufficiently helpful for investors, the Board seeks in the new standard to mandate additional disclosures by the auditor on a public company’s financial statements. PCAOB Release No. 2017-001, at 73. “[T]he auditor should bear in mind that the intent of communicating [additional disclosure] matters is to provide information about the audit of the company’s financial statements that will be useful to investors.” Id. at 31. The Board’s goal is to “reduce the information asymmetry between investors and management” by enabling investors to hear “directly from the auditor’s perspective.” Id. at 35, 66.

To this end, the new standard mandates auditors’ discussion and documentation of Critical Audit Matters (“CAMs”) discovered during the course of the audit. A CAM is a matter arising from the audit of financial statements (a) that was communicated, or required to be communicated, to the audited entity’s audit committee; (b) that relates to accounts or disclosures that are material to the financial statements; and (c) that involves especially challenging, subjective, or complex auditor judgment. PCAOB Release No. 2017-001, at 16–22. CAM reporting requirements do not apply to audits of emerging growth companies; brokers and dealers; investment companies other than business development companies; or employee stock purchase, saving, and similar plans. Id. at 101–13.

A broad range of matters can be categorized as CAMs, given the breadth of required communications between auditors and audit committees as set forth in Auditing Standard 1301, and because CAMs encompass both “matters required to be communicated to the audit committee (even if not actually communicated) and matter actually communicated (even if not required).” PCAOB Release No. 2017-001, at 17. And a CAM determination is necessarily subjective because the Board directs auditors to consider a “nonexclusive list of factors, as well as other audit-specific factors” to determine whether a matter involved especially challenging, subjective, or complex auditor judgment, and emphasizes that the determination must be made “in the context of the particular audit.” Id. at 24–25. “The determination of critical audit matters is principles-based and the final standard does not specify any items that would always constitute critical audit matters.” Id. at 22.

If the auditor determines that a CAM exists, then the auditor must discuss in the audit report, for each CAM discovered, (a) identification of the CAM; (b) principal considerations in determining that the matter is a CAM; (c) how the CAM was addressed in the audit; and (d) the relevant accounts or disclosures that relate to the CAM. PCAOB Release No. 2017-001, at 29. If the auditor discovers no CAM, then the audit report must so state as “a required element of the auditors’ report,” although—the Board asserts—”in most audits . . . the auditor will determine that at least one matter involved especially challenging, subjective, or complex auditor judgment” and “[t]here may be critical audit matters even in an audit of a company with limited operations or activities.” Id. at 37.

The new standard has significant ramifications for a company’s ability to control certain disclosures. Most notably, auditors may disclose original information (disclosed to the market for the first time before the management has chosen to do so) in communicating CAMs in audit reports. “[T]he auditor is not expected to provide original information unless it is necessary to describe the principal considerations that led the auditor to determine that a matter is a critical audit matter or how the matter was addressed in the audit.” PCAOB Release No. 2017-001, at 32 (emphasis added). As the auditor likely will feel compelled to disclose the principal considerations or describe how the matter was addressed, the exception does not appear to offer much comfort and it is likely that disclosure of original information by the auditor will frequently occur. “The objective of critical audit matters,” the Board explains, “may not be accomplished if the auditor is prohibited from providing such [original] information.” Id. at 34. The Board further declares that “[n]o PCAOB Standard, SEC rule, or other financial reporting requirement prohibits auditor reporting of information that management has not previously disclosed.” Id. at 33. And as far as auditors’ professional obligation to maintain client confidentiality goes, the Board maintains that such duties would be preempted by “federal law and regulations, including . . . PCAOB standards.” Id. In fact, the Board believes that auditors’ ability to disclose original information would “incent[ivize] the company to expand or supplement its own disclosure,” which would be an “indirect benefit of the standard.” Id. at 34.

Having the auditor as the source of disclosure for original information should raise several concerns for public companies. For example, to the extent a loss-contingency determination involves “especially challenging, subjective, or complex auditor judgment” and the matter is discussed with the audit committee, auditors may be put in a position of having to disclose additional detail regarding loss-contingencies as part of the CAM discussion in audit reports. The same issue could arise in the context of internal investigations involving company financial statements where the company has not yet disclosed the existence of the internal investigation. In these situations and others, companies may seek to make what are in effect preemptive disclosures in anticipation of statements the auditor may have to make in its CAM disclosure. These preemptive disclosures themselves could present litigation risk. Moreover, should the auditor and the company disagree on what must be disclosed—and auditors would understandably want to avoid omission or misstatement claims based on their CAM discussions—a company would no longer be in a position to address litigation risk by controlling in its entirety what is said to the market. See Matrixx Initiatives, Inc. v. Siracusano, 563 U.S. 27, 45 (2011) (“Even with respect to information that a reasonable investor might consider material, companies can control what they have to disclose under [§ 10(b)] by controlling what they say to the market.”).

Facing such dilemma and given the new standard’s profound impact on disclosure risk, companies should review the new standard in depth with their auditors. Companies may also choose to submit comments to the SEC. If the SEC approves the Board’s new standard, CAM reporting requirements become effective for large accelerated filers beginning in fiscal years ending on or after June 30, 2019, and for all other covered filers beginning in fiscal years ending on or after December 15, 2020. PCAOB Release No. 2017-001, at 114.

We will monitor the SEC’s approval process and provide an update.

IV. The Expanding Reach of Omnicare

Our previous updates have described how the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Omnicare, Inc. v. Laborers District Council Construction Industry Pension Fund, 135 S. Ct. 1318 (2015), has had a significant impact on federal securities law. This section focuses on Omnicare‘s expanding application to claims brought under antifraud provisions. As summarized below, the Ninth Circuit’s decision in City of Dearborn Heights Act 345 Police & Fire Retirement System v. Align Technology, Inc., 856 F.3d 605 (9th Cir. 2017), provides the first circuit-court opinion explicitly stating that Omnicare applies to Section 10(b) claims.

As readers will recall, the Supreme Court’s Omnicare decision addressed the scope of liability for false opinion statements under Section 11 of the Securities Act. The Court held that “a sincere statement of pure opinion is not an ‘untrue statement of material fact,’ regardless whether an investor can ultimately prove the belief wrong.” 135 S. Ct. at 1327. An opinion statement can give rise to liability only when the speaker does not “actually hold[] the stated belief,” or when the opinion statement contains “embedded statements of fact” that are untrue. Id. at 1326–27. In addition, the Court held that an omission gives rise to liability when the omitted facts “conflict with what a reasonable investor would take from the statement itself.” Id. at 1329. Put differently, an opinion statement becomes misleading “if the real facts are otherwise, but not provided.” Id. at 1328.

As we previously have forecasted, a growing number of federal courts have applied Omnicare to antifraud provisions, particularly Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act and Rule 10b-5.

Within months of the Omnicare decision, federal district courts began applying its reasoning to Section 10(b) claims. See, e.g., In re Lehman Bros. Sec. & Erisa Litig., 131 F. Supp. 3d 241, 251 n.48 (S.D.N.Y. 2015) (stating Omnicare‘s “reasoning applies with equal force to other provisions of the federal securities laws, including, as relevant to this case, Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5, which uses very similar language” as Section 11); In re Velti PLC Sec. Litig., No. 13-cv-03889-WHO, 2015 WL 5736589, at *33 (N.D. Cal. Oct. 1, 2015) (“Although Omnicare concerned statements of opinion under Section 11, several courts to consider such statements under Section 10(b) since Omnicare have applied the Omnicare analysis.”).

In 2016, the Second Circuit issued Tongue v. Sanofi, 816 F.3d 199 (2d Cir. 2016), its first published opinion interpreting Omnicare. There, investors brought two class actions alleging a pharmaceutical company failed to disclose material information in connection with an opinion statement. 816 F.3d at 205–08. The plaintiffs brought a number of state and federal claims, including Section 11 and Section 10(b) claims. Id. at 207–08. The Second Circuit did not explicitly state Omnicare applied to Section 10(b) claims. Nevertheless, the court applied Omnicare to the allegations concerning opinion statements without distinguishing among the different securities laws. Id. at 209–14. In the end, the court upheld the district court’s dismissal of the plaintiffs’ claims, concluding “that no reasonable investor would have been misled by Defendants’ optimistic statements.” Id. at 214.

In the first half of 2017, district courts have continued to apply Omnicare to Section 10(b) claims. For example, in SEC v. Thompson, No. 14-cv-9126 (KBF), 2017 WL 874973 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 2, 2017), the Southern District of New York applied Omnicare to claims brought under Section 10(b), Rule 10b-5, and Section 17 of the Securities Act. 2017 WL 874973, at *11. In doing so, the court reasoned that Sanofi “suggest[s] that Omnicare would apply to all antifraud provisions of the securities laws.” Id. at 17 n.13. Other recent cases have likewise expanded Omnicare to securities laws other than Section 11. See, e.g., Hussey v. Ruckus Wireless, Inc., No. 16-cv-02991-EMC, 2017 WL 2806702, at *4 (N.D. Cal. June 29, 2017) (applying Omnicare to a claim under Section 14(e) of the Exchange Act and stating that Omnicare established the “governing standard for falsity with respect to an opinion statement”); In re Plains All Am. Pipeline, L.P. Sec. Litig., No. H:15-02404, 2017 WL 1164301, at *13 n.4 (S.D. Tex. Mar. 29, 2017) (“[T]he Omnicare opinion’s discussions about an ‘issuer’s’ statements are equally applicable to an Exchange Act defendant speaker’s statements.”).

In May 2017, the Ninth Circuit issued its City of Dearborn decision, which explicitly held that Omnicare applies to Section 10(b) claims for falsity of opinion statements. 856 F.3d at 609. The plaintiffs alleged that the defendant made misleading opinion statements related to the goodwill valuation of a subsidiary. Id. at 612–13. The Ninth Circuit evaluated the plaintiffs’ claims under Omnicare‘s “three different standards for pleading falsity of opinion statements”:

- “First, when a plaintiff relies on a theory of material misrepresentation, the plaintiff must allege both that ‘the speaker did not hold the belief she professed’ and that the belief is objectively untrue.” Id. at 615–16 (quoting Omnicare, 135 S. Ct. at 1327).

- “Second, when a plaintiff relies on a theory that a statement of fact contained within an opinion statement is materially misleading, the plaintiff must allege that ‘the supporting fact [the speaker] supplied [is] untrue.'” Id. at 616 (quoting Omnicare, 135 S. Ct. at 1327) (alterations in original).

- “Third, when a plaintiff relies on a theory of omission, the plaintiff must allege ‘facts going to the basis for the issuer’s opinion . . . whose omission makes the opinion statement at issue misleading to a reasonable person reading the statement fairly and in context.'” Id. at 616 (quoting Omnicare, 135 S. Ct. at 1332).

In expanding Omnicare, the Ninth Circuit drew on similarities in Section 11 and Rule 10b‑5: Section 11 prohibits “untrue statement[s] of . . . fact,” while Rule 10b-5 prohibits “untrue statement[s]” and omissions of “fact.” Id. at 616 (citing 15 U.S.C. § 77k(a) and 17 C.F.R. § 240.10b-5(b)). The court also stated that the only other circuit that considered the issue, the Second Circuit in Sanofi, had applied Omnicare to Section 10(b) claims. Id.

The Ninth Circuit ultimately held that the plaintiffs’ allegations regarding false opinion statements were insufficient under Omnicare. Id. at 616–19. The court separately held that the plaintiffs failed to adequately plead scienter, which is an element of Section 10(b) claims. Id. at 619–23. In a concurring opinion, Judge Kleinfeld argued the majority should have resolved the case based on scienter without reaching the question whether Omnicare extends to Section 10(b) claims. Id. at 623–24 (Kleinfeld, J., concurring).

At bottom, Omnicare‘s reach has expanded to antifraud claims. Look for this trend to continue. So far, the Second Circuit and Ninth Circuit appear to be in agreement that Omnicare applies to at least Section 10(b) claims. We will continue to closely monitor whether other circuit courts follow suit.

V. Halliburton II Market Efficiency and “Price Impact” Cases

It has been over a year since the Eighth Circuit became the first circuit court of appeals to interpret and apply the Supreme Court’s 2014 decision in Halliburton Co. v. Erica P. John Fund, Inc. (“Halliburton II“), and it remains the only one to do so. See IBEW Local 98 Pension Fund v. Best Buy Co., Inc., 818 F.3d 775 (8th Cir. 2016). As described in detail in our April 15, 2016 client alert, the Eighth Circuit applied the burden-shifting regime of Rule 301 of the Federal Rules of Evidence (“FRE 301”) and concluded that Best Buy had met its burden of production by proffering evidence that no price movement occurred following the alleged misstatements. Consequently, the burden of persuasion shifted to the plaintiffs, whose own expert supported Best Buy’s assertion that the statements at issue did not impact the stock’s price.

Since Best Buy, two main questions continue to recur: First, what evidence may be used to rebut the Basic presumption at the class certification stage? And second, which party bears what burden?

The first issue has typically arisen where plaintiff’s price impact theory is premised on a stock price drop accompanying an alleged corrective disclosure (because the stock price did not increase when the alleged misstatement was made), and a number of lower courts have refused to consider whether the alleged corrective disclosure accompanying the stock price drop indeed corrected an alleged misstatement (thereby linking any price change to the earlier statement). See Erica P. John Fund, Inc. v. Halliburton Co., 309 F.R.D. 251, 260–61 (N.D. Tex. 2015) (“Halliburton Remand“); In re Goldman Sachs Grp., Inc. Sec. Litig., No. 10 Civ. 3461 (PAC), 2015 WL 5613150, at *6 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 24, 2015). No circuit court has expressly ruled on whether Halliburton II requires this analysis be completed at the class certification stage when it would inform the price impact analysis, though, as discussed below, both the Second Circuit and the Fifth Circuit have granted Rule 23(f) petitions seeking resolution of the question.

The second issue also remains an open question as many district courts have split from the Eighth Circuit and refused to apply FRE 301 burden shifting, despite Basic‘s own reference to it in deciding to adopt the presumption in the first place. See Basic Inc. v. Levinson, 485 U.S. 224, 245 (1988); see also Halliburton Remand, 309 F.R.D. at 260; Strougo v. Barclays PLC, 312 F.R.D. 307, 327 (S.D.N.Y. 2016). That these key questions remain open has left Halliburton II‘s legacy largely uncertain after more than three years. But multiple circuit courts have indicated an interest in answering them, and we will continue to monitor their decisions.

A. Second Circuit

As we mentioned in our 2016 Year-End Update, the Second Circuit has agreed to hear two cases addressing price impact after Halliburton II, and both are ripe for decision: Ark. Teachers Ret. Sys. v. Goldman Sachs Grp., Inc., 2015 WL 5613150 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 24, 2015) (“Goldman Sachs“), and Waggoner v. Barclays PLC, 312 F.R.D. 307 (S.D.N.Y. 2016) (“Barclays“). Goldman Sachs was argued on March 15, 2017, and Barclays was argued on November 15, 2016.

As discussed in detail in the 2016 Year-End Update, Goldman Sachs and Barclays both invite the Second Circuit to address the issues of burden shifting and consideration of evidence of the corrective nature of later disclosures. The defendants in both cases have argued that the lower court decisions certifying classes imposed a virtually insurmountable obstacle on defendants to disprove price impact. See Br. of Appellant at 32–34, Ark. Teachers Ret. Sys. v. Goldman Sachs Grp., Inc., No. 16-250 (2d Cir. Apr. 27, 2016).

We continue to await opinions in both cases and will analyze the extent to which the Second Circuit adopts, departs from, or adds to the reasoning of the Eighth Circuit.

B. Fifth Circuit

The Fifth Circuit has made its interest in considering these issues known, but settlements have prevented it from ruling. As we discussed in our 2016 Mid-Year Update, the main issue before the Fifth Circuit last year in the Halliburton remand was the propriety of the district court’s decision that “the issue of whether disclosures are corrective is not a proper inquiry at the certification stage.” Halliburton Remand., 309 F.R.D. at 261–62. Before the Fifth Circuit could issue its opinion, however, the parties requested the appeal be stayed pending a proposed settlement.

A recent 23(f) petition filed on behalf of Cobalt International Energy may finally give the Fifth Circuit a chance to articulate whether evidence that a disclosure accompanying a decrease in stock price was not actually corrective may be considered at the class certification stage. In Cobalt, the district court certified a class of investors despite evidence that no price movement accompanied the alleged misstatements and the information contained in the alleged corrective disclosures was already known to the market. See In re Cobalt Int’l Energy, Inc. Sec. Litig., No. H-14-3428, 2017 WL 2608243, at *6 (S.D. Tex. June 15, 2017); see also Def.’s Pet. for Permission to Appeal the District Court’s June 15, 2017 Order Granting Plaintiffs’ Motion for Class Certification (hereinafter “Cobalt Pet.”) at 14–16. The district court reasoned that “Defendant’s arguments about whether the disclosures were actually corrective has no bearing on the predominance inquiry for class certification,” as this “is an issue that is common to all members of the class.” Cobalt, 2017 WL 2608243, at *6 n.2 (internal quotation omitted). However, as the petitioners argue, this reasoning ignores Halliburton II‘s mandate that courts consider evidence rebutting price impact before a class is certified to ensure that the presumption of classwide reliance is warranted, see Halliburton II, 134 S. Ct. at 1214, and that “whether disclosures are actually corrective” is an “essential link” connecting a price decline with an alleged misstatement, see Cobalt Pet. at 12–13. We will monitor developments in this case to see whether the Fifth Circuit will again avail itself of the opportunity to rule on this increasingly common question.

C. Sixth Circuit

The Sixth Circuit also has the opportunity to consider the proper allocation of burden when rebutting the Basic presumption. In Willis v. Big Lots, Inc., the Southern District of Ohio certified a class of investors alleging a series of false and misleading statements, notwithstanding evidence of an absence of price impact at the time the statements were made, see — F. Supp. 3d —, 2017 WL 1063479, at *15 (S.D. Ohio Mar. 17, 2017). The district court specifically rejected the Best Buy court’s burden-shifting analysis, see id. at *16, relying on Justice Ginsburg’s one-paragraph concurrence in Halliburton II in concluding that the defendant bears the ultimate burden of proving a lack of price impact at the class certification stage.

Big Lots has filed a 23(f) petition seeking review of class certification, asserting, among other things, that the district court used the wrong evidentiary standard by failing to apply the burden-shifting regime of FRE 301. See Petition for Permission to Appeal Pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(f) at 12, In re Big Lots, Inc., No. 17-303 (6th Cir. Mar. 31, 2017). Notably, several law professors and former SEC officials have filed an amicus curiae brief in support of Big Lots’ petition. See Br. of Amici Curiae Law Professors and Former SEC Officials In Support of Petition for Permission to Appeal Pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(f), In re Big Lots, Inc., No. 17-303 (6th Cir. Apr. 7, 2017). The amici argue that because the district court did not articulate any legal standard for allocating evidentiary burdens, the decision should be reversed for this reason alone. Id. at 5. They further argue that the district court failed to place any burden on the plaintiffs. As the amici point out, the district court’s reasoning would allow securities plaintiffs to obtain class certification merely by invoking the “price maintenance” theory (i.e., pointing to a subsequent price drop) with no supporting evidence. Id. at 13–14.

In addition, on July 11, 2017, Bancorpsouth filed a second 23(f) petition in its ongoing matter in the Middle District of Tennessee. See Pet. for Permission to Appeal Pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 23(f), City of Palm Beach Gardens Firefighters Pension Fund v. Bancorpsouth, Inc., No 17-508 (6th Cir. July 11, 2017) (“Bancorpsouth Pet.”). As we discussed in our 2016 Year-End Update, the Sixth Circuit vacated a prior class certification order and remanded the case for more detailed reasoning. In re Bancorpsouth, Inc., 2016 WL 5714755, at *1 (6th Cir. Sept. 6, 2016). On remand, the district court once again certified the class, notwithstanding unrebutted evidence that the market showed no interest in the alleged misstatements. Burges v. Bancorpsouth, Inc., 2017 WL 2772122, at *11 (M.D. Tenn. June 26, 2017). Bancorpsouth’s 23(f) petition presents many of the same arguments discussed above, including whether evidence of no front-end price impact is sufficient to rebut the Basic presumption, and whether the district court should have applied the burden shifting regime of FRE 301. Bancorpsouth Pet. at 14–19. Bancorpsouth also raises the additional—and unusual—argument that plaintiff cannot show price impact, and the Basic presumption is not available to plaintiff at all, because the alleged misrepresentations were not “publicly known,” despite their attachment to one of the company’s SEC filings. Id. at 11–13.

We will continue to monitor cases in all courts throughout the year.

VI. Disclosure-Only Settlements: Developments Beyond Delaware

As discussed in our January 26, 2016 client alert, on January 22, 2016, the Delaware Court of Chancery signaled the demise—in Delaware courts, at least—of “disclosure-only” settlements with broad releases of liability in M&A stockholder suits with its decision in In re Trulia, Inc. Stockholder Litigation, 29 A.3d 884 (Del. Ch. 2016). The Trulia decision capped a series of Delaware opinions that were critical of disclosure-only settlements. See, e.g., In re Aruba Networks Stockholder Litigation, C.A. No. 10765-VCL (Del. Ch. Oct. 9, 2015) (TRANSCRIPT); In re Riverbed Tech. Inc., No. 10484-VCG, 2015 WL 5458041 (Del. Ch. Sept. 17, 2015); In re TW Telecom Inc. S’holders Litig., No. 9845-CB (Del. Ch. Aug. 20, 2015) (TRANSCRIPT); Acevedo v. Aeroflex Holding, C.A. No. 9730-VCL (Del. Ch. July 8, 2015) (TRANSCRIPT).

In Trulia, Chancellor Andre Bouchard indicated that disclosure-only settlements would be subject to increased scrutiny and warned that “practitioners should expect that disclosure settlements are likely to be met with continued disfavor in the future unless the supplemental disclosures address a plainly material misrepresentation or omission, and the subject matter of the proposed release is narrowly circumscribed to encompass nothing more than disclosure claims and fiduciary duty claims concerning the sale process.” 29 A.3d at 898. Chancellor Bouchard also expressed the “hope and trust that our sister courts will reach the same conclusion if confronted with the issue.” Id. at 899. But, more than a year after the Trulia decision, it remains to be seen whether there will be widespread adoption of Trulia’s approach.

As we forecasted in our April 27, 2016 article on Trulia, the decision does appear to have decreased—as intended—the filing of suits attacking mergers. A 2016 Cornerstone Research report highlighted an overall decrease in M&A litigation, reporting that “[f]or the first time since 2009, the percentage of M&A deals valued over $100 million that were subject to shareholder litigation declined to below 90 percent in 2015 and [the first half of] 2016.” Cornerstone Research, Shareholder Litigation Involving Acquisitions of Public Companies: Review of 2015 and 1H 2016 M&A Litigation, at 1 (2016), available at https://www.cornerstone.com/Publications/Reports/Shareholder-Litigation-Involving-Acquisitions-2016. The report concluded that the “rate of M&A litigation has declined substantially since . . . Trulia“—for M&A deals valued over $100 million, lawsuits were filed in 64 percent of such deals announced in the first half of 2016 versus 84 percent of all such deals announced in 2015. Id. at 2. Further, the share of cases filed in Delaware for the first three quarters of 2015 was 61 percent, but was only 26 percent for the fourth quarter of 2015 and the first half of 2016. Id. at 3. For litigation in which the acquired company was incorporated in Delaware, the share was 74 percent in 2015, declining to 36 percent in the first half of 2016. Id. Thus, “[t]he short-term reaction following the Trulia decision indicates both a lower rate of merger litigation and a lower share of such litigation in the Delaware Court of Chancery,” but “[i]t remains to be seen whether such shifts are sustainable.” Id. at 5.

But as noted at the outset of this Update, much of the shift so far appears to be into federal court. M&A filings in federal court increased from only 17 in 2015 to 80 in 2016. Cornerstone Research, Securities Class Action Filings 2016 Year in Review, at 11 (2017), available at https://www.cornerstone.com/Publications/Reports/Securities-Class-Action-Filings-2016-YIR. And federal court M&A lawsuit filings leaped from 11 in the first quarter of 2016, when Trulia was decided, to 45 in the first quarter of 2017. Cornerstone Research, Securities Class Action Filings Q1 Update (2017), available at https://www.cornerstone.com/Publications/Research/1Q-2017-Filings-Record-Number-of-Actions.

Adoption of the Trulia framework has been mixed in other jurisdictions. Although overall reaction to Trulia outside Delaware has been developing slowly, some courts have expressly approved of the framework. Most notably, the Seventh Circuit in In re Walgreens Co. Stockholder Litigation cited Trulia approvingly as establishing a “clearer standard” for the approval of disclosure-only settlements and adopted the “plainly material” standard articulated in Trulia. 832 F.3d 718, 725 (7th Cir. 2016). The In re Walgreens opinion referred to class actions like those presented in the case as “no better than a racket,” emphasizing that “[n]o class action settlement that yields zero benefits for the class should be approved, and a class action that seeks only worthless benefits for the class should be dismissed out of hand.” Id. at 724.

A handful of other courts have likewise expressly approved of the reasoning in Trulia. In Stein v. UIL Holdings Corporation, a Connecticut court applying Connecticut law applied the “plainly material” standard after noting it was “persuaded by the logic contained in Trulia and Walgreens Co. that disclosure settlements must be scrutinized carefully.” 2017 WL 1656891, at *3 (Conn. Super. Ct. Apr. 10, 2017). The Stein court declined to “embrace a lesser standard than that suggested by the Delaware courts and the federal courts which have recently considered these types of settlements.” Id. And in Vergiev v. Aguero, a New Jersey court applied the Trulia framework, finding that Trulia was the controlling Delaware substantive law and denying settlement approval. See Order and Judgment, and Statement of Reasons, Vergiev v. Aguero, Docket No. L-2276-15 (N.J. Sup. Ct. June 6, 2016).

However, other jurisdictions have indicated a reluctance to adopt the Trulia standard and appear to remain comparatively more open to approving disclosure-only settlements. Notably, in Gordon v. Verizon Communications, Inc., discussed in our February 17, 2017 client alert, the Appellate Division for the First Department in New York rejected the Trulia framework in favor of a lower standard for approving disclosure-only settlements. 148 A.D.3d 146 (N.Y. App. Div. 2017). Despite this break with the Delaware decision in Trulia, New York courts had, before Trulia, shown increasing skepticism toward disclosure-only settlements. See, e.g., In re Allied Healthcare S’holder Litig., No. 652188/2011, 2015 WL 6499467 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 2015) (“The willingness to rubber-stamp class-action settlements reflects poorly on the [legal] professions and on those courts that, from time to time, have approved these settlements.”); City Trading Fund v. Nye, No. 651668/2014, 2015 WL 93894 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 2015) (denying approval of a disclosure-only settlement); Gordon v. Verizon Commc’ns Inc., No. 653084/13, 2014 WL 7250212 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 2014) (“An increasing body of commentary has decried the tsunami of litigation, and attendant suspect disclosure-only settlements, associated with public acquisitions today.”). However, other post-Trulia decisions have indicated openness to disclosure-only settlements, and some of those previous decisions that rejected such settlements were reversed on appeal—including Gordon v. Verizon. See Gordon v. Verizon, 148 A.D.3d 146; City Trading Fund v. Nye, 144 A.D.3d 595 (N.Y. App. Div. 2016).

Instead of Trulia’s “plainly material” standard, the New York appellate court in Gordon v. Verizon applied a lower standard—indicating disclosure-only settlements may be approved if they provide “some benefit to the shareholders.” 148 A.D.3d at 159, 162. The Gordon court acknowledged the “increasingly negative view of ‘disclosure-only’ or other forms of nonmonetary settlements . . . reflected in decisions of courts in both Delaware and New York” but also opined that the court “has a responsibility to preserve the viability of those nonmonetary settlements that prove to be beneficial to both shareholders and corporations, while protecting against the problems with such settlements … in order to promote fairness to all parties.” Id. at 154, 156. A subsequent decision from a New York court—approving a disclosure-only settlement—confirmed that “Gordon’s ‘some benefit’ test cannot be viewed as anything other than an outright rejection of Trulia’s ‘plainly material’ standard.” Roth v. Phoenix Companies, Inc., 50 N.Y.S.3d 835, 838 n.4 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. Mar. 24, 2017). Instead, when evaluating class-action settlements, New York courts examine five factors established before Gordon (“the likelihood of success, the extent of support from the parties, the judgment of counsel, the presence of bargaining in good faith, and the nature of the issues of law and fact”), see In re Colt Indus. S’holder Litig., 155 A.D.2d 154, 160 (1990), aff’d as modified sub nom. Colt Indus. S’holder Litig. v. Colt Indus. Inc., 566 N.E.2d 1160 (1991), and two additional factors added by the Gordon decision (“whether the proposed settlement is in the best interests of the putative settlement class as a whole, and whether the settlement is in the best interest of the corporation”). Gordon v. Verizon, 148 A.D.3d at 158.

In a more recent example, a Tennessee appellate court affirmed the approval of a disclosure-only settlement in In re Pacer Int’l, Inc., No. M2015-00356, 2017 WL 2829856, at *8 (Tenn. Ct. App. June 30, 2017). The In re Pacer court acknowledged that “disclosure-only settlements are disfavored in some courts,” citing Trulia, but nonetheless approved the settlement because “when weighed against the relative weakness of Plaintiffs’ claims . . . the additional disclosures provided adequate consideration.” Id.

We will continue to monitor the adoption progress of the Trulia reasoning framework outside of Delaware and the impact of Trulia on pushing M&A litigation into other jurisdictions.

VII. Delaware Litigation Developments

A. Delaware Courts Clarify Boundaries Of the Corwin Doctrine

As we discussed in our 2016 year-end update, since the Delaware Supreme Court’s decision in Corwin v. KKR Financial Holdings LLC, 125 A.3d 304, 314 (Del. 2015), Delaware courts have expressed skepticism of post-closing suits for damages, particularly those suits asserting post-closing disclosure claims. In Corwin, the Delaware Supreme Court applied the business judgement rule as the standard of review for transactions approved by a non-coerced, fully informed stockholder vote, thus establishing a formidable hurdle to plaintiffs hoping to overcome a motion to dismiss. This trend continued in the first half of 2017, but the Court of Chancery also found in one case that Corwin did not apply under the relevant facts.

1. Court of Chancery Finds Claims Extinguished Under Corwin

In In re Solera Holdings, Inc. Stockholder Litig., 2017 WL 57839 (Del. Ch. Jan. 5, 2017), a former Solera stockholder alleged that the board members who approved its acquisition by a private equity firm breached their fiduciary duties. Because the company was acquired after both the solicitation of numerous financial firms and a go-shop period, Chancellor Bouchard held, “based on longstanding doctrine reaffirmed in Corwin v. KKR Financial Holdings LLC[,] that the Solera board’s decision to approve the transaction is subject to the business judgment presumption because, in a fully-informed and uncoerced vote, a disinterested majority of Solera’s stockholders approved the merger . . . .” Id. at *1.

In February the Delaware Supreme Court summarily affirmed the Court of Chancery’s June 2016 judgment in In re Volcano Corp. Stockholder Litig., 143 A.3d 727 (Del. Ch. 2016), aff’d, 156 A.3d 697 (Del. 2017). There, the Court of Chancery rejected a complaint brought by former public stockholders of Volcano Corporation alleging that its board of directors breached their fiduciary duties in approving an $18-per-share all cash merger when, five months prior, Volcano’s board declined a $24-per-share offer from the same acquirer. Id. at 729. Vice-Chancellor Montgomery-Reeves “agree[d] with the defendants” that “the business judgment rule standard of review irrebuttably applies to the plaintiffs’ allegations and insulates the merger from a challenge on any ground other than waste, which the plaintiffs fail to allege.” Id.

Then, in April, Chancellor Bouchard dismissed a similar complaint under the business judgment rule in In re Paramount Gold & Silver Corp. Stockholders Litig., 2017 WL 1372659 (Del. Ch. Apr. 13, 2017). There, defendants merged a set of mining assets in Mexico with another company and entered into a royalty agreement. Because the stockholder vote approving this transaction was fully informed, Chancellor Bouchard dismissed plaintiffs’ claim that the royalty agreement, in tandem with a termination fee provision in the merger agreement, amounted to an unreasonable deal protection device. Id. at *1.

Finally, in June, the Court of Chancery again applied Corwin to dismiss post-closing damages claims brought in Appel v. Berkman, C.A. No. 12844-VCMR (Del. Ch. June 13, 2017) a case arising out of a transaction involving Diamond Resorts. Vice-Chancellor Montgomery-Reeves concluded that plaintiff’s disclosure claims relating to one director’s abstention, another director’s alleged conflicts, and certain fees received by a financial advisor were not material, and thus the shareholder vote approving the transaction was not adequately alleged to have been coerced.

2. Court of Chancery Concludes Corwin Inapplicable

For the first time in In re Saba Software, Inc. Stockholder Litigation, 2017 WL 1201108 (Del. Ch. Mar. 31, 2017), as rev’d, (Apr. 11, 2017), the Court of Chancery declined to apply the Corwin doctrine. Before the company began considering strategic alternatives, the SEC alleged that the company had engaged in fraud requiring it to restate its pre-tax earnings by $70 million—but the company repeatedly and without explanation failed to do so, NASDAQ delisted its stock, and the SEC revoked its registration. Id. at *1. After a months-long sales process, the board presented stockholders with a choice to either accept $9 per share in merger consideration, which was well below the average trading price for two years prior, or continue to hold then-deregistered, illiquid stock. Id. Defendants argued that plaintiff’s claims should be dismissed because, under Corwin, a fully informed, uncoerced stockholder vote “cleansed” the merger of any wrongdoing. Id. at *7. But the court held the vote was not fully informed because the merger proxy omitted material facts as to why Saba was unable to restate its financials and Saba’s post-deregistration options and viability as a going concern. Id. at *11, 13. On these unusual facts, the court also held the vote was coercive because the board’s failure to disclose any basis for assessing whether rejecting the merger made sense left stockholders with no practical alternative to approving it. Id. at *15–16.

One month later, the Court of Chancery again found the Corwin doctrine inapplicable in In re Massey Energy, Co. Derivative & Class Action Litigation (“Massey II”), 2017 WL 1739201 (Del. Ch. May 4, 2017). Plaintiffs in Massey II challenged defendants’ alleged conscious disregard of safety laws that led to a mining explosion and harm to the company well before a sale process leading to a merger. Id. at *19. The court dismissed the derivative Caremark claim without prejudice to the ability of the company’s acquirer to pursue the claim itself. Id. at *10–11. Concluding that Corwin did not apply, the court required “a far more proximate relationship than exists here between the transaction or issue for which stockholder approval is sought and the nature of the claims to be ‘cleansed’ as a result of a fully-informed vote.” Id. at *20. The court reasoned that Corwin was not meant to “exonerate[e] corporate fiduciaries for any and all of their actions or inactions preceding their decision to undertake a transaction for which stockholder approval is obtained,” and that such an outcome would have the “perverse effect of negating the value of the derivative claims that [the buyer] paid to acquire along with Massey’s other assets.” Id.

Most recently, in Sciabacucchi v. Liberty Broadband Corp., 2017 WL 2352152 (Del. Ch. May 31, 2017), the Court of Chancery concluded a complicated series of transactions presented to stockholders of nominal defendant Charter Communications, Inc. for approval was structurally coercive and, therefore, the Corwin doctrine did not apply to cleanse any alleged wrongdoing in the transactions. At issue were Charter’s purchase of one entity and merger with another (the “Acquisitions”), which all parties agreed contributed value to Charter; and Charter’s issuance of equity and a 6% voting proxy to defendant Liberty Broadband Corp., its largest stockholder (the “Issuances”). Id. at *1. Plaintiffs alleged Charter directors breached fiduciary duties by structuring the transactions in a way favorable to Liberty and detrimental to Charter. Id. The court held that the stockholders’ approval of the Issuances was structurally coerced because, even though the Issuances were extrinsic to the Acquisitions, the Acquisitions were conditioned on the stockholders approving the Issuances. Id. at *22–24.

B. Delaware Supreme Court Considers Clarifying When The Court Of Chancery Should Defer to Deal Price in Appraisal Litigation

So far this year, a clear trend has developed in Delaware appraisal litigation: Courts are becoming more deferential to deal prices following a robust auction, but are not hesitant to query whether such auctions are in fact robust. For example, on May 26, Vice Chancellor Slights rejected a challenge brought by a group of PetSmart’s former stockholders who alleged that the company’s fair value, at the time it was acquired for $83-per-share, was actually $128.78-per-share. In re PetSmart, Inc., 2017 WL 2303599 (Del. Ch. May 26, 2017). Crucial to his conclusion was the fact that respondents demonstrated “that the process leading to the Merger was reasonably designed and properly implemented to attain the fair value of the Company. Moreover, the evidence does not reveal any confounding factors that would have caused the massive market failure, to the tune of $4.5 billion (a 45% discrepancy), that Petitioners allege occurred here.” Id. at *2.

Four days later, Vice Chancellor Glasscock determined a company’s fair value to be lower than its sale price. In In re Appraisal of SWS Grp., Inc., 2017 WL 2334852, (Del. Ch. May 30, 2017), the Court acknowledged that the company “was exposed to the market in a sales process. As this Court has noted, most recently in In Re Appraisal of Petsmart, Inc., a public sales process that develops market value is often the best evidence of statutory ‘fair value’ as well . . . . [H]owever, the sale of SWS was undertaken in conditions that make the price thus derived unreliable as evidence of fair value . . . .” Id. at *1. Petitioners contended that the company “was on the brink of a turnaround before the sale, and had only been suffering due to unique and unprecedented market conditions,” while respondents countered that it “had fundamental structural problems making it difficult to compete at its size.” Id. at *1. SWS is unique in that neither party relied on the deal price to demonstrate fair value, ultimately persuading the Court to do the same.

We await further guidance on these issues from the Delaware Supreme Court, which heard oral argument in June in In re Appraisal of DFC Glob. Corp., 2016 WL 3753123 (Del. Ch. July 8, 2016).

C. Plaintiffs Successfully Plead Caremark Claims – the “Most Difficult” in Corporate Law

Three decisions from the first half of 2017 demonstrate why a Caremark claim is known as “possibly the most difficult theory in corporation law.” In a summary order dated March 3, 2017, the Delaware Supreme Court affirmed the Court of Chancery’s decision in Melbourne Municipal Firefighters’ Pension Trust Fund v. Jacobs, 2016 WL 4076369 (Del. Ch. Aug. 1, 2016), aff’d, 158 A.3d 449 (Del. 2017) (Table). Generally, a Caremark claim “seeks to hold directors accountable . . . for damages arising from a failure to properly monitor or oversee employee misconduct or violations of law.” Id. at *7. In Melbourne, plaintiffs sued the directors of Qualcomm, Inc., alleging they had acted in bad faith by consciously disregarding their duty to oversee the company’s compliance with applicable antitrust laws. Id. at *8–9. Alleged red flags included private antitrust claims and claims by regulators in Korea and Japan over the company’s business practices. Id. at *3–4. The Court of Chancery granted defendants’ motion to dismiss, finding that the record showed the board constantly monitored the red flags and expressed the company’s view that its practices did not violate antitrust laws. Id. at *12.

Similarly, in In re Qualcomm Inc. FCPA Stockholder Derivative Litigation, 2017 WL 2608723 (Del. Ch. June 16, 2017), the Court of Chancery dismissed Caremark claims arising from alleged violations of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (“FCPA”). In Qualcomm, plaintiffs asserted that the Qualcomm board and audit committee knew of red flags regarding FCPA compliance in China and Korea. Id. at *1. But, like in Melbourne, the court in Qualcomm concluded that the complaint did not allege that the board consciously disregarded the red flags, finding instead that many documents cited as red flags also included planned remedial actions and that plaintiffs’ attempts simply to second-guess the timing and manner of the board’s response failed to state a Caremark claim. Id. at *3–4.

Recently, however, the Court of Chancery concluded plaintiffs adequately pleaded Caremark claims in “excruciating detail” in In re Massey Energy Co. Derivative & Class Action Litigation (“Massey II”), 2017 WL 1739201 (Del. Ch. May 4, 2017). The dispute in Massey II arose from an April 2010 explosion that killed 29 miners at Massey’s Upper Big Branch (“UBB”) coal mine in West Virginia. Id. at *1. In its aftermath, state and federal regulators produced reports concluding that “Massey knowingly flouted the law and caused the UBB disaster by ignoring safety requirements and actively subverting regulatory enforcement,” and multiple parties faced criminal liability for the UBB disaster, including the company that later acquired Massey, several Massey employees, and Massey’s then-CEO, id. at *8–9. Six years before Massey II, then-Vice Chancellor Strine denied a motion for a preliminary injunction in In re Massey Energy Co. (“Massey I”), 2011 WL 2176479 (Del. Ch. May 31, 2011), and observed that “there seems little doubt that a faithful application of the plaintiff-friendly pleading standard would preclude a dismissal of [plaintiffs’] claims at the pleading stage,” id. at *20. The Massey II court echoed this conclusion, dismissing the Caremark claim without prejudice to the ability of Alpha, to which the derivative claim transferred as a property right by virtue of its acquisition of Massey, to pursue the claim itself. Massey II, 2017 WL 1739201, at *11.

[1] NERA’s 2016 study on securities class action filings was recently cited by the U.S. Supreme Court, in CalPERS v. ANZ Securities Inc., No. 16-373, Slip op. at 4 n.2 (June 26, 2017).

[2] Leidos is represented in the appeal by the Gibson Dunn team of Andrew S. Tulumello, Mark A. Perry, Jason J. Mendro, Joshua D. Dick, Kellam M. Conover, Christopher M. Rigali, John D. Avila, and Monica L. Haymond.

The following Gibson Dunn lawyers assisted in the preparation of this client update: Monica Loseman, Paul Collins, Doug Cox, Matt Kahn, Marshall King, Brian Lutz, Mark Perry, Michael Scanlon, Lissa Percopo, John Avila, Jefferson Bell, Scott Campbell, Stephen Dent, Jordan Jacobsen, Shannon Mader, Jacob Rierson, Zach Wood, Jin Yoo, and Lindsey Young.

Gibson Dunn lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these developments. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, or any of the following members of the Securities Litigation Practice Group Steering Committee:

Meryl L. Young – Co-Chair, Orange County (949-451-4229, [email protected])

Robert F. Serio – Co-Chair, New York (212-351-3917, [email protected])

Brian M. Lutz – Co-Chair, San Francisco/New York (415-393-8379/212-351-3881, [email protected])

Jonathan C. Dickey – New York/Palo Alto (212-351-2399, 650-849-5370, [email protected])

Thad A. Davis – San Francisco (415-393-8251, [email protected])

George H. Brown – Palo Alto (650-849-5339, [email protected])

Jennifer L. Conn – New York (212-351-4086, [email protected])

Ethan Dettmer – San Francisco (415-393-8292, [email protected])

Barry R. Goldsmith – New York (212-351-2440, [email protected])

Mark A. Kirsch – New York (212-351-2662, [email protected])

Gabrielle Levin – New York (212-351-3901, [email protected])

Monica K. Loseman – Denver (303-298-5784, [email protected])

Jason J. Mendro – Washington, D.C. (202-887-3726, [email protected])

Alex Mircheff – Los Angeles (213-229-7307, [email protected])

Robert C. Walters – Dallas (214-698-3114, [email protected])

Aric H. Wu – New York (212-351-3820, [email protected])

© 2017 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.