January 5, 2018

How will the Trump Administration alter enforcement of the False Claims Act (“FCA”)? This is a question we fielded frequently at the end of 2016. Our answer at the time: We do not expect there to be significant changes in FCA enforcement, and we expect that the Department of Justice (“DOJ”) and private qui tam plaintiffs will continue to brandish the FCA as a powerful weapon. Our answer today? Enforcement of the FCA, although slightly less active during 2017 than 2016, shows little signs of a long-term letup. To the contrary, the FCA remains a significant source of government-facing and private-plaintiff litigation.

2017 marked the eighth straight year in which the federal government has recovered more than $3 billion in FCA cases and in which more than 700 new FCA cases were filed. To put that in historical context, each of those marks had been reached only once before this most-recent eight-year stretch. Although federal recoveries dipped from 2016, this past year also marked the fourth-highest yearly haul ever for the federal government. And despite hints from isolated elements of the Trump Administration that there may be some interest in reigning in perceived overreach with the FCA, top DOJ officials have reaffirmed their dedication to stringent enforcement of the statute.

On the case law front, the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2016 landmark decision in Universal Health Services, Inc. v. United States ex rel. Escobar, 136 S. Ct. 1989 (2016), continued to reverberate through the lower courts. Some courts have implemented the Escobar Court’s intent, barring FCA cases—at the summary judgment or even the pleading stage—when prior government actions demonstrate that the alleged misconduct at issue was not material to government payment. But other courts have imposed different standards, parsing Escobar in plaintiff-friendly fashions. Meanwhile, in Escobar‘s shadow, the lower federal courts have grappled with numerous other complex issues involving the FCA, including pleading standards, the public disclosure bar, the first-to-file bar, and more. In fact, this last six months saw more than a dozen significant circuit court decisions on issues relating to the FCA.

Finally, on the legislative front, there is little to report. As recently as mid-2016, legislative reform to reign in the FCA was the subject of Congressional hearings and murmurings by commentators.[1] But today it seems no legislator—let alone a voting bloc—is eager to scale back a law intended to prevent “waste, fraud, and abuse.” In the current political climate, it is perhaps hard to find blame in that decision.

We address all of these and other developments in greater depth below. We focus first on enforcement activity at the federal and state levels, turn to important FCA settlements and judgments that were announced in the second half of 2017, discuss the limited activity on the legislative front, and then conclude with an analysis of significant cases from the past six months.

As always, Gibson Dunn’s recent publications on the FCA may be found on our website, including in-depth discussions of the FCA’s framework and operation, industry-specific presentations, and practical guidance to help companies avoid or limit liability under the FCA. And, of course, we would be happy to discuss these developments—and their implications for your business—with you.

II. FCA ENFORCEMENT ACTIVITY

A. Total Recovery Amounts: 2017 Recoveries Exceed $3.7 Billion

The federal government recovered more than $3.7 billion in civil settlements and judgments under the FCA during the 2017 fiscal year, the fourth-highest amount on record.[2] There were also 799 new FCA cases filed in 2017, the fourth-highest number in any single year. Of the more than $3.7 billion that the government recovered, almost $426 million—the second-highest amount ever—came from suits where the federal government declined to intervene and that were driven by private qui tam “whistleblower” plaintiffs.[3] All in all, 2017 was the eighth consecutive year in which the government recovered more than $3 billion and where there were at least 700 new FCA matters.

B. Qui Tam Activity

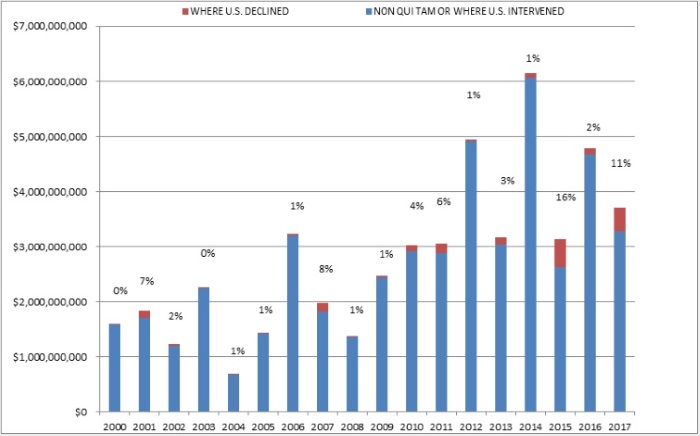

Last year, we suggested that the government’s record 2015 recovery in qui tam suits where the government declined to intervene may have been an aberration.[4] But 2015 looks less like an anomaly, at least after this past year. In 2017, the government recovered nearly $426 million in cases where it declined to intervene, the second-highest amount on record. That amount, which quadrupled 2016’s haul in such cases, constituted 11% of all recoveries last year.

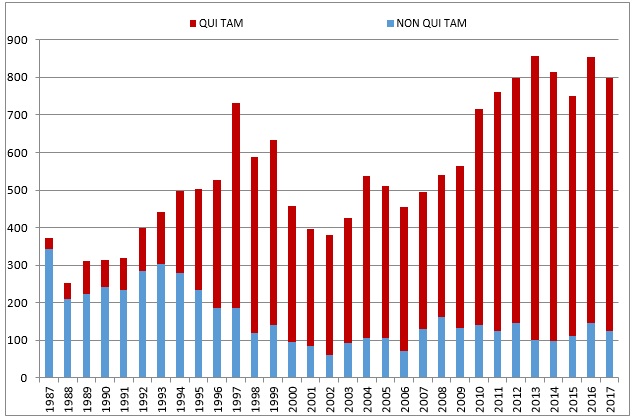

The proportion of cases in 2017 initiated by a whistleblower (84% (674 of 799)) remained in line with historical averages; that proportion has vacillated between 77% and 88% every year since 2009. Going back farther in time, however, it is important to recall that the total number, and proportion, of qui tam cases has increased substantially since Congress amended the FCA in 1986: from 1987 through 1991, only about a quarter of FCA cases were qui tam cases, but whistleblowers have now brought just shy of 12,000 qui tam cases since then (71% of the total).

The chart below demonstrates both the increase in overall FCA litigation activity since 1986 and the distinct shift from government-driven investigations and enforcement to qui tam-initiated lawsuits. Although there was a slight decline compared to 2016, the total number of FCA cases remains far higher than in the first decade of the new millennium, when approximately 470 cases (on average) were initiated each year.

Number of FCA New Matters, Including Qui Tam Actions

Source: DOJ “Fraud Statistics – Overview” (Dec. 21, 2017)

When a whistleblower brings an FCA action, the government may choose to intervene, which it does about 20% of the time.[5] Even if the government declines to intervene, at least 70% of any recovery still goes to the government. In fiscal year 2017, that large majority of cases where the government declined to intervene accounted for 11% of all federal recoveries. This may not seem like much, but it was just the second time that such recoveries exceeded 9%, as shown below.

Settlement or Judgments in Cases Where the Government Declined Intervention as a Percentage of Total FCA Recoveries

Source: DOJ “Fraud Statistics – Overview” (Dec. 21, 2017)

C. The Trump Administration’s Statements on the FCA

As we reported in our 2017 Mid-Year update, Trump Administration officials have publicly announced their intent to enforce the FCA vigorously, beginning with a January pledge by U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions to “make it a high priority of the [D]epartment [of Justice] to root out and prosecute fraud in federal programs and to recover any monies lost due to fraud or false claim[s].” He also voiced support for whistleblower-driven FCA suits as a “healthy” and “effective” method of rooting out fraud. Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein also committed, in connection with his January nomination, to continue robust enforcement of the FCA and to ensure that DOJ attorneys work collaboratively with relators.

This messaging from DOJ has continued on. For example, in his remarks announcing that DOJ’s 2017 Health Care Fraud Takedown operation would be the largest ever in the program’s eight-year history, Attorney General Sessions pledged to “use every tool we have to stop criminals from exploiting vulnerable people and stealing our hard-earned tax dollars” and to “develop even more techniques to identify and prosecute wrongdoers.”[6] Attorney General Sessions added that the takedown program—a coordinated nationwide effort between DOJ, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (“HHS”), and law enforcement—had charged 412 defendants, nearly 300 of which were in the process of being suspended or banned from participation in federal programs, as of July 2017.

This is not to say that all statements from the Administration have been aligned. For instance, while addressing criticism levied during a House Financial Services Committee meeting in October—specifically, that the government’s use of the FCA against Federal Housing Administration (“FHA”) lenders was driving lenders away from the program and increasing costs to borrowers—U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Secretary Ben Carson pledged to address the “ridiculous” rise of FCA actions against FHA lenders.[7] Secretary Carson’s comments, which included a statement that the Administration was “already addressing that problem” with DOJ’s staff, suggests a potential check on FCA actions.

Similarly, in October, the Director of the Fraud Section of DOJ’s Civil Division gave a speech that left some industry-watchers wondering if DOJ intended to revisit its practices with respect to seeking dismissal of qui tam FCA suits that it determined to be meritless. By statute, DOJ has always had the authority to intervene and seek dismissal of qui tam cases. Historically, however, DOJ has used this authority sparingly. Acknowledging that “clearly meritless cases can serve only to increase the costs for the government and health care providers alike,” the DOJ official cautioned that “[w]hile qui tam cases will always remain a significant staple of the government’s False Claims Act efforts, we are mindful of the need to maximize the use of the government’s limited resources.”[8] Initial press reports viewed these remarks as an indication that DOJ had updated its longstanding policy of intervening to seek dismissal of meritless FCA actions only infrequently. But DOJ later clarified that the remarks had merely been commentary on DOJ’s authority to seek dismissal and did not reflect any actual changes to its enforcement policy.[9]

The year also saw staffing changes at DOJ that could impact the government’s FCA enforcement practices. In July, Attorney General Jeff Sessions downsized the Health Care Corporate Fraud Strike Force, which was created in 2015 to focus on pursuing complex cases involving corporate health care fraud.[10] The personnel changes—apparently reflecting the Administration’s shift in favor of high-priority issues like the opioid epidemic—were swiftly reported in the media as significantly weakening the Corporate Fraud Strike Force. But this change should not be seen as an end to corporate health care fraud prosecutions. DOJ publicly disavowed any such notion, stating that the Health Care Corporate Strike Force is “going strong under steady leadership” and that DOJ is “continuing to vigorously investigate and hold accountable individuals and companies that engage in fraud.”[11] And DOJ left in place the related Medicare Fraud Strike Force, which has an established expertise in complex health care cases and a long track record of pursuing health care FCA cases. Thus, it is safe to say that DOJ remains committed to health care fraud cases more broadly, even as it has reorganized how it handles such cases internally.

Although we will continue to track these developments in the upcoming year, we do not anticipate any significant slowdown from the Administration. We certainly have not seen any shortfall of aggression from DOJ since the change in Administration, and efforts to combat “waste, fraud, and abuse” continue to draw bipartisan support.

D. Industry Breakdown

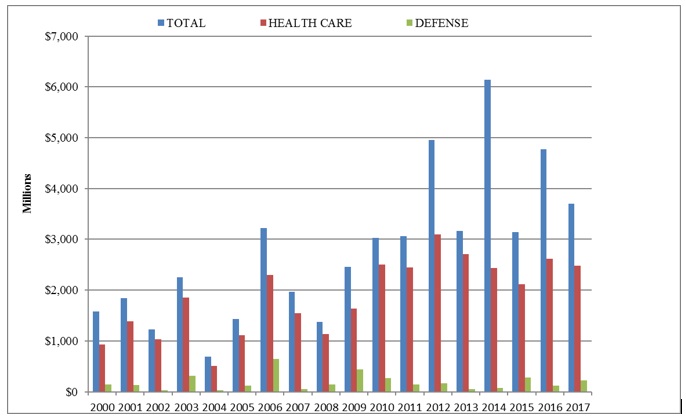

The past year’s distribution of recoveries by industry remained consistent with prior years, as health care industry companies continued to pay the majority (67%) of all sums collected by the government. The financial industry, too, remained a significant target even though more than eight years have passed since the 2008 financial crisis. Notably, the government recovered more than $543 million stemming from alleged housing and mortgage fraud in 2017.[12]

Settlement or Judgments by Industry in 2017

1. Health Care and Life Sciences Industries

The health care industry paid 67% of all federal FCA recoveries this past year, in line with its average annual proportion since 2010. In 2017, that amounted to almost $2.5 billion, a slight decrease from $2.6 billion the year before. Since 2010, these figures have been remarkably consistent, as the government has recovered between $2.4 billion and $2.7 billion from health care companies every year but two—in 2012 when it recovered $3.1 billion, and in 2015 when it recovered $2.1 billion.

As in years past, a handful of disproportionately large settlements drove the ten-figure sum. In a case that drew substantial media attention, a branded pharmaceutical maker paid $465 million to resolve government allegations that the company avoided paying Medicare rebates by misclassifying its life-saving emergency medication as a generic drug.[13] Meanwhile, in a case that garnered relatively less attention, a company that sells electronic health records software settled with the government for $155 million after allegedly misrepresenting its software’s capabilities.[14]

DOJ and qui tam actions are not the only area of risk for health care and life sciences companies. In its Spring 2017 Semiannual Report to Congress, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General (“HHS OIG”) reported that it also commenced 458 civil actions (including but not limited to FCA actions) in the first half of the 2017 fiscal year,[15] an increase from the 379 it commenced during the first half of the 2016 fiscal year.[16]

No description of DOJ’s and HHS OIG’s enforcement activities is complete without discussion of the Anti-Kickback Statute (“AKS”) and the Stark Law. The AKS prohibits giving or offering—and requesting or receiving—any form of payment in exchange for referring a product or a service that is covered by federally funded health care programs.[17] Since the Affordable Care Act of 2010, claims resulting from a violation of the AKS are deemed “false” for purposes of the FCA. The Stark Law prohibits physicians from referring Medicare patients to a provider with which the physician has a financial relationship.[18]

One of the largest health care industry FCA settlements of the year, a $350 million agreement, involved a medical device manufacturer that allegedly paid kickbacks to health care providers in exchange for agreeing to use its skin graft product.[19]

In recent years, FCA recoveries from hospitals and hospital systems have taken a back seat to recoveries from pharmaceutical companies, medical device companies, and outpatient clinics. However, in 2017, a large chain of hospitals paid $60 million after the government alleged that it overbilled various federal programs for services provided by claiming that it had actually provided other, more expensive, services.[20] And two related Missouri hospitals agreed to pay $34 million for allegedly paying improper incentives to doctors who referred oncology patients to a chemotherapy infusion clinic.[21]

2. Government and Defense Contracting Industry

Recoveries from government contracting firms rebounded in 2017, up to $220 million from $122 million in 2016.[22] Defense contractors, however, made up a smaller-than-usual percentage of government contracting enforcement actions in 2017, while contractors who provide more routine government services were more of a focus of FCA cases over the last year. For example, a software company paid $45 million after the government alleged that it failed to disclose some of its discounting practices to the General Services Administration, resulting in overpayments.[23] The government also continued in 2017 its recent trend of pursuing FCA theories based on evasion of import duties, for example, when it secured a settlement from a company and two individuals who allegedly evaded customs duties after they imported wood furniture from China.[24]

3. Financial Industry

Even as the 2008 financial crisis has begun to recede into memory, 2017 was a banner year for FCA recoveries from financial services companies who allegedly defrauded the government in the run-up to the crisis. Most notably, the government won more than $296 million at trial against a company and its CEO who allegedly falsely certified the quality of thousands of mortgage loans and then recovered tens of millions of FHA insurance dollars when the loans failed.[25] The government also secured a $74 million settlement from another mortgage lender who allegedly engaged in similar activities dating back to 2006.[26]

III. NOTEWORTHY SETTLEMENTS AND JUDGMENTS ANNOUNCED DURING THE SECOND HALF OF 2017

We summarize below a number of the notable FCA settlements and judgments announced during the past six months (we covered notable settlements and judgments from the first half of the year in our 2017 Mid-Year Update), including those in the health care and life sciences industries, government and defense contracting industry, and the financial industry. These cases provide specific examples of the industries the government has targeted, as well as the theories of liability that the government and relators have advanced.

A. Settlements

1. Health Care and Life Sciences Industries

- On July 17, 2017, three Ohio-based health care providers and their executives agreed to pay roughly $19.5 million to resolve allegations related to their alleged submission of false claims to Medicare for unnecessary rehabilitation and hospice services. The government alleged that the companies provided therapy services at excessive levels to increase Medicare reimbursement and provided hospice services to patients who were ineligible for those Medicare benefits. In addition, the individual executive defendants allegedly solicited and received kickbacks to refer patients from skilled nursing facilities managed by corporations they partially controlled or owned to a particular home health care services provider. As part of the settlement, two defendants entered into a five-year corporate integrity agreement with HHS OIG. The whistleblowers, three former employees of the corporate defendants, will receive almost $3.7 million for their share of the government’s recovery.[27]

- On August 17, 2017, two wholly owned subsidiaries of a pharmaceutical company headquartered in Pennsylvania agreed to pay $465 million to settle allegations that they knowingly misclassified a certain product as a generic drug to avoid rebate expenditures primarily owed to Medicaid. The company also entered into a five-year corporate integrity agreement with HHS OIG, which requires an independent organization to conduct an annual review of the defendant’s practices regarding the Medicaid drug rebate program. The whistleblower, a competing pharmaceutical manufacturer, will receive approximately $38.7 million as a relator’s share.[28]

- On August 21, 2017, two suppliers of ophthalmological goods and services, as well as their former chief executive officer, agreed to pay more than $12 million to resolve allegations that they paid unlawful kickbacks to physicians and thereby violated the AKS and FCA. The alleged kickbacks included the provision of free travel, entertainment, and improper consulting agreements. The government contended that by providing these items of value, the defendants knowingly induced physicians to utilize the defendants’ products and services, and subsequently submit false claims to the federal government. In connection with the FCA settlement, the defendants agreed to a five-year corporate integrity agreement with HHS OIG. The whistleblower will receive 19.5% of the amount recovered.[29]

- On August 28, 2017, two California-based companies and their two principal executives agreed to pay approximately $2 million to resolve federal and state allegations that they knowingly overbilled a program designed to serve Californians with developmental disabilities. Specifically, defendants allegedly submitted claims for payment of services that were never provided, retained overpayments to which they knew they had no claim, and falsified documents to support their claims for services that were never performed. The whistleblower will receive a 20% share of all proceeds paid to the federal government.[30]

- On September 1, 2017, a medical center located in New Mexico and its Texas-based partner agreed to pay approximately $12.24 million to settle allegations that they made illegal donations to county governments, which the counties used to fund the state share of Medicaid payments to the hospital. Under New Mexico’s now discontinued Sole Community Provider program, the state provided supplemental Medicaid funds to hospitals, and the federal government reimbursed 75% of the expenditures. Federal law mandated that the state or counties had to provide the remaining 25% of the funds; it was allegedly unlawful for private hospitals to do so. The whistleblower, a former county health care administrator, will receive approximately $2.2 million of the recovery.[31]

- On September 5, 2017, a pharmaceutical manufacturer agreed to pay $58.65 million to settle allegations that it did not comply with U.S. Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”)-mandated Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (“REMS”) for its Type II diabetes medication. The settlement includes disgorgement of $12.15 million for alleged violations of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (“FDCA”), and $46.5 million for alleged violations of the FCA. The FCA-related payment resolves specific allegations that the company caused the submission of false claims related to the drug by authorizing sales messages that could create a false or misleading impression with physicians that the REMS-required message was erroneous, irrelevant, or unimportant, and by encouraging use of the drug by adult patients who did not have Type II diabetes. The federal government will receive approximately $43.1 million, and state Medicaid programs will receive more than $3.3 million; the amount to be recovered by private party whistleblowers is undecided.[32]

- On September 8, 2017, a California-based biopharmaceutical company agreed to pay more than $7.55 million to settle allegations that it paid kickbacks to doctors to induce them to prescribe a fentanyl-based drug. The improper payments allegedly included (1) 85 free meals to doctors and staff from a high-prescribing practice; (2) paying doctors $5,000 and speakers $6,000 to attend an “advisory board” partly organized, and attended, by the defendant’s sales team members; (3) paying approximately $82,000 to a physician-owned pharmacy under a performance-based rebate program; and (4) payments to doctors to refer patients to the company’s patient registry study. The whistleblower will receive more than $1.2 million of the amount recovered.[33]

- On September 11, 2017, a South Carolina chain of physician-owned family medicine clinics agreed to pay $1.56 million to settle allegations that it submitted false claims to the Medicare and TRICARE programs. The principal owner and former chief executive officer, as well as the former laboratory director, also agreed to pay $443,000 to resolve the allegations, bringing the total settlement to over $2 million. The government specifically alleged that the entity’s incentive compensation plan paid its physicians a percentage of the value of laboratory and other diagnostic tests that they ordered, which the entity then billed to Medicare in violation of the Stark Law. In addition, the defendants allegedly submitted claims for medically unnecessary laboratory services by creating, and using, custom panels comprised of needless diagnostic tests, and programming accounting software to change billing codes for laboratory tests to ensure payment. The entity and the principal owner also agreed to a corporate integrity agreement with HHS OIG, which ensures that the owner has no management role for five years and obligates the company to implement internal compliance reforms.[34]

- On September 13, 2017, a New York hospital operator agreed to pay $4 million to resolve allegations that it engaged in improper financial relationships with referring physicians. The improper relationships included compensation and office lease arrangements that allegedly did not comply with requirements of the Stark Law, which restricts relationships between entities and referring physicians. The whistleblower will receive $600,000 of the recovery.[35]

- On September 18, 2017, an Alaska state agency agreed to pay almost $2.5 million to resolve allegations that it submitted inaccurate quality control data and information to the U.S. Department of Agriculture and received unearned performance bonuses for fiscal years 2010 through 2013. The inaccuracies occurred in connection with the agency’s implementation of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (formerly the Food Stamp Program). The agency had contracted with a third-party consultant to provide recommendations to lower its quality control error rate, but the advice, as implemented by the agency, allegedly injected bias into the quality control process, which resulted in the reporting inaccuracies. This is the third settlement with a state agency arising from the advice given by the consulting company.[36]

- On September 22, 2017, a Massachusetts-based pharmaceutical company agreed to pay more than $35 million to resolve criminal and civil charges related to the introduction of an alleged misbranded drug into interstate commerce. The company also agreed to plead guilty to certain criminal charges, entered into a deferred prosecution agreement relating to its criminal liability under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, agreed to a civil consent decree and permanent injunction to prevent future violations of the FDCA, and entered into a corporate integrity agreement with HHS OIG. Of the $35 million, the company will pay $28.8 million over three years to settle federal ($26.1 million) and state ($2.7 million) liability for allegedly (1) submitting claims to government health care programs arising from its improper promotion of the drug; (2) altering or falsifying statements of medical necessity and prior authorizations that were submitted to federal health care programs; and (3) defraying patients’ copayment obligations, in alleged violation of the AKS, by funneling funds through an entity that claimed to be a non-profit patient organization. Three whistleblowers will receive $3.7 million from the federal proceeds.[37]

- On September 27, 2017, a hospital based in South Carolina agreed to pay more than $7 million to settle allegations that it submitted false Medicare claims. The government contended that the defendant knowingly disregarded the statutory requirements for submitting Medicare claims for services, including radiation oncology services, emergency department services, and clinic services. In particular, the hospital allegedly (1) billed for radiation oncology services when a qualified practitioner was not immediately available to provide direction throughout the radiation procedure; (2) billed for services provided at a minor care clinic as if it was an emergency department; and (3) billed emergency department services rendered by mid-level providers as if they were provided by a physician. The whistleblower will receive more than $1.2 million of the recovery and will also receive over $850,000 to resolve her wrongful termination claims.[38]

- On October 19, 2017, a Tennessee-based nursing home operator agreed to pay $5 million to settle allegations that the company billed Medicare and Medicaid for allegedly worthless nursing home services and services that were never provided. The company also agreed to enter into a corporate integrity agreement with HHS OIG. The government’s investigation originated with claims by the whistleblower, a former nursing home employee, of patient abuse and neglect, substandard care, and denial of basic services. The whistleblower will receive $1 million as part of the settlement.[39]

- On October 27, 2017, a New York-based health care provider agreed to pay $6 million to resolve allegations that a subsidiary submitted false claims to government health care programs for unnecessary rehabilitation therapy services. The defendant also agreed to enter into a five-year corporate integrity agreement with HHS OIG. The two whistleblowers will receive $990,000 of the recovery.[40]

- On October 30, 2017, an Ohio-based hospice care provider, and various wholly owned subsidiaries, agreed to pay $75 million to settle allegations that they submitted false claims for hospice services to Medicare. The settlement also included a five-year corporate integrity agreement with HHS OIG. The government alleged that the defendants submitted claims for services to hospice patients who were not terminally ill, and submitted claims for continuous home care services that were unnecessary, not provided, or not performed in line with Medicare requirements. In addition, the government alleged that the provider rewarded employees with bonuses for the number of patients receiving hospice services, and pressured staff to increase the volume of continuous home care, regardless of need. The settlement constitutes the largest recovery ever from a provider of hospice services under the FCA.[41]

- On December 1, 2017, a physician-owned hospital located in Texas agreed to pay $7.5 million to settle allegations that it paid physicians illegal kickbacks in the form of free marketing services in exchange for surgical referrals. The marketing services included print, radio, and television advertisements, pay-per-click campaigns, billboards, website upgrades, brochures, and business cards. The defendant also agreed to enter into a five-year corporate integrity agreement with HHS OIG. The whistleblowers, two former employees in the defendant’s marketing department, will receive $1.1 million of the amount recovered.[42]

- On December 12, 2017, a Florida-based cancer care provider, and certain of its subsidiaries and affiliates, agreed to pay $26 million to resolve a Medicare compliance issue that the company had voluntarily disclosed regarding the submission of false attestations about the company’s use of electric health records software, as well as separate whistleblower allegations related to the submission of claims for services provided pursuant to referrals from physicians with whom the defendant allegedly had improper financial relationships. The company also entered into a five-year corporate integrity agreement with HHS OIG. The whistleblower, the company’s former interim vice president of financial planning, will receive a $2 million share of the government’s recovery.[43]

- On December 20, 2017, a Maryland-based pharmaceutical company agreed to pay $210 million to resolve allegations that it used a 501(c)(3) organization as a conduit to pay copays for Medicare patients taking the company’s pulmonary arterial hypertension drugs. The company allegedly made donations to the foundation, which then used the donations to satisfy the copays. The company also allegedly prohibited needy Medicare patients from participating in its free drug program; instead, the company allegedly referred these patients to the foundation, which allowed for Medicare claims. In addition to the settlement, the company entered into a five-year corporate integrity agreement with HHS OIG.[45]

- On December 21, 2017, a Florida-based hospice company agreed to pay over $5 million to settle allegations that it knowingly billed the government for medically unnecessary and undocumented hospice services. The whistleblower, a former employee, will receive approximately $900,000 of the recovered funds.[46]

- On December 22, 2017, an Illinois-based retailer agreed to pay $32.3 million to settle allegations that in-store pharmacies failed to report discounted prescription drug prices to Medicare, Medicaid, and TRICARE. The government alleged that the corporation offered discounted generic drug prices to customers who paid cash through club programs, but knowingly failed to report the discounted prices to federal health care programs when reporting its usual and customary prices, which the government uses to determine reimbursement rates. The settlement is part of a larger $59 million settlement that also resolves state Medicaid and insurance claims against the company. The whistleblower will receive $9.3 million of the recovered funds.[47]

2. Government and Defense Contracting Industry

- On August 10, 2017, a Virginia-based contractor and its subsidiaries agreed to pay $16 million to settle allegations that they knowingly conspired with, and caused, small businesses to submit false claims for payment related to fraudulently obtained small business contracts. The defendant and its subsidiaries allegedly induced the government to award certain contracts by misrepresenting eligibility requirements, including the small businesses’ affiliation with the defendant, size, and standing as service-disabled or as qualified socially or economically disadvantaged businesses under federal business development programs. In addition, the defendant allegedly engaged in bid rigging to distort or inflate prices charged to the government under the contracts. The settlement is one of the largest involving alleged fraud implicating small business contract eligibility. The whistleblower will receive a share of the recovery of approximately $2.9 million.[48]

- On August 15, 2017, a Virginia-based defense contractor agreed to a $9.2 million settlement to resolve allegations that it overbilled the government for labor on Navy and Coast Guard ships located at its shipyards in Mississippi. The contractor allegedly mischarged labor to certain contracts when it was actually performed under other contracts, and billed the government for dive operations to support ship hull construction that did not actually occur. The whistleblower will receive more than $1.5 million of the recovery.[49]

- On September 13, 2017, a Virginia-based contractor agreed to pay $5 million to settle allegations that it failed to properly vet personnel working in Afghanistan under a State Department contract for labor services. The contract required the contractor to conduct extensive background checks on U.S. personnel in specific positions and to submit the names of non-U.S. personnel to the State Department for additional security clearance. The government alleged that claims submitted by the contractor for labor services of the improperly vetted personnel, in violation of the background-check requirements, were false claims. The whistleblower will receive $875,000 as his share of the recovery.[50]

- On October 3, 2017, three New York-based contractors, as well as two New York-based owners, agreed to pay more than $3 million to resolve allegations that they improperly obtained federal set-aside contracts reserved for service-disabled veteran-owned (“SDVO”) small businesses. One of the three contractors allegedly recruited a service-disabled veteran to serve as a figurehead, received several SDVO small business contracts, and subcontracted almost all of the work to the other two entities rather than the veteran. The two individual defendants allegedly executed the scheme by making, or causing to be made, false statements to the Department of Veterans Affairs (“VA”) regarding eligibility to participate in the SDVO small business contracting program and compliance with related requirements. The whistleblower will receive $450,000 of the recovery.[51]

- On October 16, 2017, a Virginia-based defense contractor agreed to pay $2.6 million to resolve allegations that the company submitted false claims for payment to the Department of Defense for unqualified security guards stationed in Iraq. The government alleged that the defendant knowingly billed the United States for security guards who failed to pass contractually required firearms proficiency tests, and concealed the guards’ inability to satisfy the requirements by creating false test scorecards. The whistleblower, a former employee, will receive approximately $500,000 of the amount recovered.[52]

- On November 8, 2017, a Kentucky-based trucking company agreed to pay $4.4 million to settle allegations that it submitted claims for payment related to shipping contracts that were obtained by bribing government officials. The whistleblower will receive $814,000 of the recovery.[53]

3. Financial Industry

- On August 8, 2017, two mortgage originators and underwriters based in New Jersey, and a third based in Minnesota, agreed to pay more than $74 million to resolve allegations that they knowingly provided mortgage loans insured by the FHA, guaranteed by the VA, and purchased by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac that did not meet origination, underwriting, and quality control requirements mandated by those entities. Of the $74 million, $65 million will satisfy the FHA allegations, and $9.45 million will satisfy the remaining allegations. The whistleblower who made some of the allegations, a former employee, will receive more than $9 million from the settlement.[54]

- On December 8, 2017, a banking conglomerate headquartered in Louisiana agreed to pay more than $11.6 million to settle allegations that it falsely certified compliance with federal requirements to obtain insurance on mortgage loans from the FHA. The defendant, who participated as a direct endorsement lender in the FHA insurance program, admitted the following facts as part of the settlement: (1) it certified insurance mortgage loans that did not meet Department of Housing and Urban Development (“HUD”) requirements and were ineligible for FHA mortgage insurance, and HUD paid FHA insurance claims on some of these mortgages; (2) it advised HUD that it was no longer paying illegal commissions to underwriters and those who provided underwriting activities, but failed to disclose that it was making incentive payments; (3) it failed to timely self-report material violations of HUD requirements, including audit findings regarding substandard quality reviews; and (4) as a result of its conduct and omissions, HUD insured loans approved by the bank that were ineligible for FHA mortgage insurance that HUD would not have otherwise insured, and HUD incurred losses when it paid insurance on those loans. The whistleblowers, two former employees of the bank, will receive a 20% share of the recovery.[55]

4. Other

- On September 22, 2017, a California-based renewable energy company agreed to pay $29.5 million to resolve allegations that it submitted inflated claims on behalf of itself and affiliated investment funds to the Department of Treasury under Section 1603 of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (“Section 1603”). The company allegedly overstated the cost bases of its solar energy properties in its certified Section 1603 grant applications and received inflated payments from the Treasury as a result. As part of the settlement, the defendant, and its affiliates, also agreed to release pending and future claims against the United States for Section 1603 payments.[56]

- On December 19, 2017, a Texas-based oil and gas corporation and its affiliates agreed to pay $2.25 million to settle allegations that they underpaid royalties owed on natural gas produced from federal lands in Wyoming. The government alleged that the entities knowingly reduced the royalty amounts by deducting fees paid to other companies, including the cost of placing the gas in marketable condition.[57]

B. Judgments

· On September 14, 2017, a federal judge in the Southern District of Texas awarded a $296 million judgment against two mortgage entities and a $25.3 million judgment against their president and chief executive officer for alleged fraudulent conduct while participating in the FHA mortgage insurance program. In November 2016, a unanimous jury found that the defendants violated the FCA and the Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act of 1989 (“FIRREA”). Specifically, the jury determined that the defendants falsely certified that thousands of high-risk, low-quality loans were eligible for FHA insurance, and subsequently submitted claims to FHA when the loans defaulted. The defendants were also found liable for allegedly originating FHA-insured loans from “shadow” branch offices without HUD approval, and submitting false quality control reports and certifications to HUD. The court’s judgment trebled the jury’s $92 million FCA verdict and imposed additional statutory penalties under the FCA and FIRREA.[58]

IV. LEGISLATIVE ACTIVITY

A. Federal Legislation

The federal legislative front was frankly uneventful during the latter half of 2017, with no new legislation significantly affecting the FCA enacted or introduced in Congress. Additionally, at least for this year, Congress largely shelved consideration of President Trump’s plan to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act (“ACA”) (except for the repeal of the individual mandate as part of the recent tax cut legislation), which could have affected the ACA’s amendments to the FCA, as discussed in our 2017 Mid-Year False Claims Act update.

Federal regulatory activity implicating the FCA also remained quiet. An FDA regulation proposed in January 2017—amending the agency’s definition of “intended use” for drugs and devices codified in 21 C.F.R. § 201.128 and 21 C.F.R. § 801.4, respectively—saw little progress during the past six months.[59] As noted in our Mid-Year update, the rule’s effective date was delayed until March 19, 2018,[60] in response to a petition from industry opponents that argued against an expansion of the definition of “intended use,”[61] which could have spawned a flurry of unwarranted FCA lawsuits. After expiration of the comment period on the issues raised by the petition, the FDA published an interim response to those concerns on July 28, 2017, noting that a decision is still forthcoming, pending further review and analysis by agency officials.[62]

B. State Legislation

As noted in previous updates, HHS OIG is in the process of determining if state FCA laws appropriately mirror the federal FCA’s enforcement abilities so that they are deemed as effective as the federal FCA in facilitating qui tam actions; if HHS OIG finds that they do not, the states lose their ability to increase their share of recoveries in cases that prosecute Medicaid fraud by 10%. In our Mid-Year update, we reported that HHS OIG notified 15 states that their state FCA laws needed to be amended to mirror the federal law’s increased civil penalties by no later than the end of 2018. Since then, a few states have progressed toward that goal:

- On July 24, 2017, a bill that would amend the California False Claims Act to mirror penalties allowed under the federal FCA was signed by the Governor.[63]

- On August 25, 2017, a bill amending the Illinois False Claims Act to mirror penalties allowed under the federal FCA was approved by the Governor.[64]

- On November 28, 2017, a bill that would amend the civil penalties in the Michigan Medicaid False Claims Act to mirror penalties allowed under the federal FCA was referred to the Senate Judiciary Committee.[65]

Bills that would have similarly amended the New York and North Carolina false claims act statutes remain under consideration and have not progressed since our last update.[66]

Additionally, a number of states have either enacted into law, introduced, or failed to progress legislation making other notable changes to their respective state FCA laws. Those developments include:

- Alabama passed a law amending its Medicaid fraud statute, which strengthened penalties for violations, but also introduced a requirement that violations be “knowing.”[67] A related bill that would have established a broader state false claims act, on which we reported in our Mid-Year 2017 Update, failed to emerge from committee.[68]

- Florida introduced a bill that would remove the Florida False Claims Act from the ambit of the Open Government Sunset Review Act, a 1995 law that mandates periodic review and repeal of all exemptions to Florida’s open records law. The amendment would exempt the Florida FCA’s under seal requirements from review and potential repeal under the Sunset Review Act.[69]

- Arkansas enacted a bill that updates and clarifies several definitions in the state’s Medical Fraud Act and Medicaid Fraud False Claims Act, but does not significantly alter the substance of the law.[70]

- In Michigan, a bill that would create a general Michigan False Claims Act remains in the state Senate’s Committee on the Judiciary.[71] If enacted, the bill would expand Michigan’s current Medicaid False Claims Act beyond the Medicaid context.[72]

- A Pennsylvania law that would create the state’s False Claims Act remains in the House Judiciary Committee, where it has resided since March 2017.[73]

- North Dakota failed to pass House Bill 1174, which would have provided liability and a penalty for false claims for medical assistance made to the state.[74]

We expect that the upcoming year will bring increased state legislative activity as the December 31, 2018 deadline set by HHS OIG approaches.

V. NOTABLE CASE LAW DEVELOPMENTS

While the legislative front was uneventful, the jurisprudential front was just the opposite. In 2017, courts continued to grapple with the Supreme Court’s seminal decision in Escobar, draw the boundaries of the public disclosure and first-to-file bars, and explore many other nuances of the FCA. The results were dozens of cases that contribute meaningfully to the corpus of FCA case law. As always, we summarize the most significant cases below.

A. Continued Development of the Materiality Requirement Post-Escobar

Eighteen months after it was decided, the application of the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Escobar continues to be an issue confronting courts throughout the country. In particular, courts have been forced to determine how to apply the Escobar Court’s self-described “rigorous” and “demanding” materiality requirement. 136 S. Ct. at 2002–03.

1. The Third Circuit Extends Escobar to Pre-2009 Claims

In United States ex rel. Spay v. CVS Caremark Corp., 875 F.3d 746 (3d Cir. 2017), the Third Circuit addressed a question left unanswered by Escobar—whether the materiality standard also applies to conduct before the adoption of the Fraud Enforcement and Recovery Act of 2009 (“FERA”), which included a “material” standard in the FCA’s text for the first time. After reviewing the Court’s analysis in Escobar, the Third Circuit reached the “unavoidable conclusion” that: “(1) Section (a)(1) [of the FCA] has a materiality requirement, even though that requirement has never been expressed in the statute [prior to FERA], and (2) the standard used to measure materiality did not change in 2009 when Congress amended the FCA to include a definition of ‘material.'” Spay, 875 F.3d at 763. The Third Circuit further concluded “that the FCA has always included a materiality element . . . and the definition of ‘material,’ which is derived from the common law and was enshrined in the statute itself in 2009, has not changed.” Id.

The Third Circuit’s analysis is relevant to the small number of remaining cases that are premised on pre-2009 conduct. But it has broader implications as well. For example, the Third Circuit’s determination that the FCA and common law “both employ the same standard” for materiality suggests that the materiality analysis in Escobar applies to all theories of FCA liability, regardless of the statutory premise or theory of liability pursued by the government or relators.

2. The Third, Fifth, and Seventh Circuits Address the Importance of the Government Continuing to Make Payments

In recent months, three circuits have addressed the extent to which the government’s continued payment of claims establishes a lack of materiality following Escobar. In Spay, the Third Circuit considered whether the general industry use of dummy prescriber information on authorized claims that “errored out” because of missing or incorrectly formatted prescriber information constituted material misstatements. 875 F.3d at 750. The record established that government employees responsible for authorizing payments “knew that dummy identifiers were being used” and “the reason for using them,” but the government nevertheless paid for the prescriptions. Id. at 764. Because the misstatements at issue actually “allowed patients to get their medication,” the Third Circuit concluded that “they are precisely the type of ‘minor or insubstantial’ misstatements where ‘[m]ateriality . . . cannot be found.'” Id. (quoting Escobar, 136 S. Ct. at 2003).

The Fifth Circuit reached a similar conclusion in United States ex rel. Harman v. Trinity Industries Inc., 872 F.3d 645 (5th Cir. 2017). In Harman, a contractor “inadvertently omitted” information about a design change to a guardrail system, which subsequently became eligible for federal-aid reimbursement in 2005. Id. at 665. In 2012, the Federal Highway Administration (“FHWA”) was advised of the design change, but continued to maintain the system’s eligibility for federal reimbursement, including by issuing a June 2014 memorandum that affirmed that the system remained eligible for reimbursement. Id. at 649, 665. Nevertheless, a federal jury found the contractor liable for the submission of false claims and imposed a verdict of more than $663 million—the largest judgment in the history of the FCA. Id. at 651. But the Fifth Circuit reversed that judgment, observing that, “though not dispositive,” the payment of claims despite knowledge of alleged fraud “substantially increased the burden . . . in establishing materiality.” Id. at 663. Because the evidence in the record was “insufficient to overcome” the “very strong evidence” that FHWA knew about the design changes and still authorized reimbursement, the court reversed and entered judgment as a matter of law for the defendant. Id. at 668, 670. In a recent amicus brief, DOJ cited the Harman case as an example of “circumstances in which a court may properly decide [materiality] as a matter of law.” Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae Supporting Appellant, United States ex rel. Prather v. Brookdale Senior Living Communities, 2017 WL 4769476, at *13 n.2.

A more recent Seventh Circuit decision shows, however, that at least under some circumstances one court has found that continued payment of claims alone may not be dispositive on the question of materiality. In United States v. Luce, 873 F.3d 999 (7th Cir. 2017), the defendant mortgage company owner allegedly falsely asserted that he had no criminal history in order to participate in a government insurance program. Id. at 1002–03. On appeal from the district court’s ruling granting summary judgment to the government, the Seventh Circuit considered whether the fact that the government-insured loans continued to be issued after defendant’s false statements became known was adequate evidence to preclude summary judgment in the government’s favor. The Seventh Circuit concluded that it was not, stating that “[a]lthough new loans were issued, the Government also began debarment proceedings, culminating in actual debarment. There was no prolonged period of acquiescence.” Id. at 1008.

3. District Courts Address Adequacy of Materiality Allegations at Pleadings Stage Post-Escobar

Before the Supreme Court’s decision in Escobar, the materiality element was often viewed as a fact-intensive issue that was difficult to contest at the summary judgment stage, let alone based on the pleadings. In Escobar, however, the Supreme Court instructed that materiality is “[not] too fact intensive for courts to dismiss [FCA] cases on a motion to dismiss.” 136 S. Ct. at 2004 n.6.

As a result, defendants have increasingly advanced materiality arguments as a basis for dismissal, including at the pleading stage. While the courts are continuing to evaluate the precise requirements for alleging materiality, certain common themes have been developing. For instance, district courts have repeatedly made clear that a conclusory allegation that the false statement is material to the government’s payment decision is inadequate to avoid dismissal. See, e.g., United States ex rel. Payton v Pediatric Servs. of Am., Inc., No. cv416-102, 2017 WL 3910434, at *10 (S.D. Ga. Sept. 6, 2017) (holding that a complaint “must do something more than simply state that compliance is material”); United States v. Scan Health Plan, No. CV 09-5013-JFW, 2017 WL 4564722, at *6 (C.D. Cal. Oct. 5, 2017) (dismissing claim based “only [on] conclusory allegations that the [defendants’] conduct was material”).

Thus, a conclusory statement that the government would not have paid if it had been aware of the alleged false statements is “insufficient” because “it does not show how [the] misrepresentations were material.” United States ex rel. Mateski v. Raytheon Co., No. 2:06-cv-03614, 2017 WL 3326452, at *7 (C.D. Cal. Aug. 3, 2017). In contrast, some district courts have determined that materiality has been adequately pleaded where complaints included allegations that: the government had terminated eligibility for similar violations, see United States ex rel. Lacey v. Visiting Nurse Serv. of N.Y., No. 14-cv-5739, 2017 WL 5515860, at *10 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 26, 2017); the defendant had been informed by the government that compliance was material, see Smith v. Carolina Med. Ctr., No. 11-2756, 2017 WL 3310694, at *11 (E.D. Pa. Aug. 2, 2017); regulatory language established a link between compliance and payment, see United States ex rel. LaPorte v. Premiere Educ. Grp., No. 11-3523, 2016 WL 2747195, at *17 (D.N.J. May 11, 2016), recons. denied, 2017 WL 4167434, at *4 (D.N.J. Sept. 20, 2017); the misrepresentation shifted the risks bargained for by the parties, see United States ex rel. Hussain v. CDM Smith, Inc., No. 14-CV-9107, 2017 WL 4326523, at *8 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 27, 2017) (addressing allegations that contractor “was improperly shifting billables from fixed-fee to cost-plus-fee contracts”); and defendant’s conduct indicates a belief that fraudulent content “would be important,” see United States ex rel. Gelman v. Donovan, No. 12-cv-5142, 2017 WL 4280543, at *7 (E.D.N.Y. Sept. 25, 2017).

Ultimately, while the cases make clear that more than a conclusory allegation is required to comply with Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 9(b), the case law has not definitively decided how much more will suffice. Given the factual nature of the issue, courts may have a difficult time defining in the abstract what makes a materiality allegation adequate.

B. Updates on Rule 9(b) Pleading Standards

As discussed in past updates, circuit courts have taken varying approaches to the application of the heightened pleading standards set forth by Rule 9(b) to FCA claims. Although the circuits generally agree that Rule 9(b) applies to FCA claims, a circuit split has developed among those circuits that apply the standard strictly, see, e.g., United States ex rel. Clausen v. Lab. Corp. of Am., 290 F.3d 1301, 1311 (11th Cir. 2002) (requiring “some indicia of reliability . . . to support the allegation of an actual false claim for payment being made to the Government”), and those that apply a “relaxed” standard, see, e.g., United States ex rel. Grubbs v. Kanneganti, 565 F.3d 180, 190 (5th Cir. 2009) (requiring the allegation of “particular details of a scheme to submit false claims paired with reliable indicia that lead to a strong inference that claims were actually submitted”). Thus, the question of how much detail is required to survive a motion to dismiss remains a hotly debated issue.

1. The Second Circuit Claims the Circuit Split Is “Greatly Exaggerated”

In United States ex rel. Chorches v. American Medical Response, 865 F.3d 71 (2d Cir. 2017), the Second Circuit downplayed the circuit split over the Rule 9(b) standard. The court identified instances in which even those circuits that apply a “stricter” standard “declined to impose an ineluctable bright-line rule that every relator must allege details of actual claims submitted,” but instead took a more nuanced approach that evaluates the pleadings on a case-by-case basis. Id. at 90–92. Based on its reading of the requirement, the Second Circuit concluded that a relator must allege “specific and plausible facts from which [a court] may easily infer” that the defendant “systematically falsified its records to support false claims” and “that the false records were actually presented to the government for reimbursement.” Id. at 84.

2. The First Circuit Establishes an Exception to Its “Strict” Application of Rule 9(b)

The First Circuit has applied the “stricter” standard. See, e.g., United States ex rel. Karvelas v. Melrose-Wakefile Hosp., 360 F.3d 220, 233 (1st Cir. 2004) (holding that at least “some of th[e] information [e.g., the date or amount of claims or other details regarding the forms submitted] for at least some of the claims must be pleaded”) (internal quotations omitted). However, in United States ex rel. Nargol v. DePuy Orthopaedics, Inc., 865 F.3d 29 (1st Cir. 2017), the First Circuit recognized an exception to this rule where a complaint “essentially alleges facts showing that it is statistically certain that [the defendant] cause[d] third parties to submit many false claims to the government.” Id. at 41. Nargol involved allegations that a manufacturer “palmed off latently defective versions of its FDA-approved [hip-replacement device] on unsuspecting doctors who sought government reimbursement for the defective products.” Id. at 31.

The First Circuit determined that the complaint’s absence of specific information regarding claims was not fatal for several reasons. First, there was no reason to suggest that the defects “were known to the doctors, the patients, or the government” or that they could have been readily discovered during surgery. Id. at 40. Second, there was no reason to suspect that physicians did not seek reimbursement for defective devices. Id. Third, it was likely that every sale of the device “was accompanied by an express or plainly implicit representation that the product being supplied was the FDA-approved product, rather than a materially deviant version of that product.” Id. at 40–41. Finally, the First Circuit found that it was “highly likely that the expense is not one that is primarily borne by uninsured patients in most instances.” Id. at 41. Given these facts, and the allegations that thousands of devices were sold, it was “virtually certain that the insurance provider in many cases was Medicare, Medicaid, or another government program.” Id. Under these circumstance, the First Circuit saw “little reason for Rule 9(b) to require Relators to plead false claims with more particularity than they have done” as the complaint “alleges the details of a fraudulent scheme with ‘reliable indicia that lead to a strong inference that claims were actually submitted.'” Id. (quoting United States ex rel. Duxbury v. Ortho Biotech Prods., L.P., 579 F.3d 13, 29 (1st Cir. 2009)).

3. The Sixth Circuit Requires the Entire Chain Linking Defendant’s Conduct to the Eventual Submission of Claims to Be Pleaded With Particularity

In United States ex rel. Ibanez v. Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., 874 F.3d 905 (6th Cir. 2017), the Sixth Circuit considered the application of Rule 9(b) to allegations involving “a long chain of causal links from defendants’ conduct to the eventual submission of claims.” Id. at 914. Ibanez involved allegations of false claims stemming from an off-label promotion scheme of Abilify, “an antipsychotic drug approved for various prescriptive uses by the FDA.” Id. at 912. Specifically, the relator alleged that the defendant improperly promoted Abilify to a physician, who then prescribed the medication to a patient for an off-label use. That patient thereafter filled the prescription at a pharmacy, with the pharmacy subsequently submitting a claim to the government for reimbursement of the prescription. Id. at 915. The Sixth Circuit held that the complaint must “adequately allege the entire chain—from start to finish—to fairly show defendants cause[d] false claims to be filed,” including “alleg[ing] specific intervening conduct” along the chain. Id. at 914–15. Because relators failed to provide details of “any representative claim that was actually submitted to the government for payment,” the district court’s dismissal of the claim was upheld. Id. at 915.

Additionally, in Ibanez, the Sixth Circuit further clarified the boundaries of the circuit’s “personal knowledge exception” for applying a “relaxed Rule 9(b) pleading standard,” established in United States ex rel. Prather v. Brookdale Senior Living Communities, Inc., 838 F.3d 750 (6th Cir. 2016). Ibanez, 874 F.3d at 915 (internal quotations omitted). The Sixth Circuit held that the exception only “applies in limited circumstances . . . where the relator was specifically employed to review [the] documentation allegedly submitted to [the government].” Id. at 915. It was this knowledge, paired with specific allegations regarding payment requests, “that satisfied a relaxed 9(b) standard.” Id. at 915–16. Based on this decision, along with a decision earlier this year in United States ex rel. Hirt v. Walgreen Co., 846 F.3d 879 (6th Cir. 2017), it appears that outside of the specific circumstance in Prather, the Sixth Circuit will employ a “strict” Rule 9(b) analysis in FCA cases.

C. Developments in the FCA’s Public Disclosure Bar

As amended by the Affordable Care Act in 2010, the public disclosure bar states that a court “shall dismiss” an FCA action if “substantially the same allegations or transactions were publicly disclosed” through listed sources, as long as the relator does not qualify as an “original source.” 31 U.S.C. § 3730(e)(4) (2010). A relator is an “original source” when he or she “has knowledge that is independent of and materially adds to the publicly disclosed allegations or transactions.” Id. § 3730(e)(4)(B).

Courts have grappled with the extent to which their precedent interpreting the prior version of the statute survived the 2010 amendments, including when assessing whether the bar remains jurisdictional (which the prior version of the statute had indicated), how similar allegations must be to previous disclosures before triggering the bar, and how much detail a relator must add to qualify as an original source.

1. The Seventh Circuit Interprets the Public Disclosure Bar and Original Source Standards

The Seventh Circuit assessed the as-amended language in Bellevue v. Universal Health Services of Hartgrove, Inc., 867 F.3d 712, 721 (7th Cir. 2017), in which it dismissed claims that the defendant submitted false certifications to the government. Analyzing both versions of the statute, the Seventh Circuit noted that it was “unclear” whether the amended public disclosure bar remained jurisdictional (like its predecessor), but ultimately declined to reach the issue, choosing instead to apply the jurisdictional bar under the pre-amendment framework because some of the alleged conduct occurred before 2010. Id. at 717–18. Turning to the substantive impact of the amendments, the Seventh Circuit explained that the amended version of the statute “expressly incorporates the ‘substantially similar’ standard” previously used by the Seventh and other circuits when assessing whether the current action was “based upon” previous public disclosures. Id. at 718. The court also held that the amendment to the “original source” definition was a “clarification rather than a substantive change,” and thus would apply retroactively to conduct occurring before 2010. Id.

With regard to the disclosure, the court explained that allegations are publicly disclosed for purposes of the bar “when the critical elements exposing the transaction as fraudulent are placed in the public domain.” Id. (internal citation omitted). Rejecting the relator’s argument that the prior public disclosure found in audit reports and letters did not reference any knowing misrepresentation of facts, the court clarified that it is enough to be able to “infer, as a direct and logical consequence of the disclosed information,” that a defendant knowingly submitted false claims to the government. Id. at 718–19 (internal citation omitted). The court distinguished other case law involving “qualitative judgments” as to appropriate standards of care, for example, and found that the allegations had been publicly disclosed where the “audit report and letters provided a sufficient basis to infer that [the defendant] was presenting false information to the government.” Id. at 719.

In assessing whether the allegations were “substantially similar,” the court listed several factors to consider, including whether a relator alleged “a different kind of deceit,” presented allegations that “required independent investigation and analysis to reveal any fraudulent behavior,” or alleged information involving “an entirely different time period.” Id. (internal citation omitted). Ultimately, the court found that the alleged conduct was “based upon” allegations publicly disclosed through the audit report and letters. Id. at 720.

As to whether the relator qualified as an original source, the court applied the as-amended standard, which requires that the relator have knowledge that “is independent of and materially adds to the publicly disclosed allegations or transactions.” Id. (quoting 31 U.S.C. § 3730(e)(4)(B) (2010)). The court concluded that the relator had “not ‘materially added’ to the publicly disclosed allegations,” and therefore did not address the question of whether the relator had independent knowledge, indicating a deficiency in either element undermines a relator’s original source status. Id.

2. The Fifth Circuit Assesses Pre-Filing Disclosure Requirements Under the Public Disclosure Bar

Before a relator brings an FCA claim in the name of the government, the relator must disclose to the government information on which the allegations are based, in order to qualify as an “original source.” 31 U.S.C. § 3730(e)(4)(A). This is in addition to another pre-filing disclosure requirement found in the FCA. Id. § 3730(b)(2). In United States ex rel. King v. Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 871 F.3d 318 (5th Cir. 2017), the Fifth Circuit clarified that not just any “disclosure” to the government will satisfy the “original source” pre-filing disclosure requirement. Instead, the disclosure must “suggest an FCA violation” to qualify. Id. at 327. Specifically, in affirming dismissal of the action at issue, the Fifth Circuit found that the relators “failed to present any evidence indicating that their pre-suit disclosure connected the knowledge of [the defendant’s] conduct to false claims made to the government.” Id. at 326. The court explained that the disclosure “must—at a minimum—connect direct and independent knowledge of information about [the defendant’s] conduct to false claims submitted to the government.” Id. at 327. Because the pre-suit disclosure at issue, although providing details regarding alleged FDCA and AKS violations, was “completely devoid of any indication connecting such information with false claims presented to the government,” the court found the disclosure insufficient to satisfy the FCA’s “original source” pre-filing disclosure requirement.

3. The Sixth Circuit Analyzes How the Public Disclosure Bar May Apply to Allegations of Later Conduct

The Sixth Circuit assessed whether a relator’s claims may move forward despite public disclosures of similar conduct if the allegations in the current action pertain to a different time period. In Ibanez, the court determined that the “common principle” that a “public disclosure occurs when enough information exists in the public domain to expose the fraudulent transaction” survived the amendments to the statute. 874 F.3d at 918. But the court disagreed with the defendant’s claim that the government’s previous FCA actions and related corporate integrity agreements with the defendant publicly disclosed the allegedly improper promotion of the product at issue. Id. at 919. Rather, the Sixth Circuit found that allegations—like those asserted by the relator—”that [a] scheme either continued despite the agreements or was restarted after the agreements”—would not be precluded by the allegations previously disclosed through corporate integrity agreements, even if the present allegations resembled those of the previously resolved scheme. Id. The court clarified that this conclusion “may be true only to the extent that the new allegations are temporally distant from the previously resolved conduct.” Id. at 919 n.4.

4. The Eighth Circuit Interprets the Original Source Standard

Interpreting the original source exception under the pre-amendment version of the public disclosure bar, the Eighth Circuit found in In re Baycol Products Litigation, 870 F.3d 960, 962 (8th Cir. 2017), that in some circumstances a relator need not have direct and independent knowledge of a defendant’s allegedly false communications to the government. The defendant argued that lawsuits, news articles, public filings, and medical literature publicly disclosed the relator’s allegations that the defendant concealed drug risks through its marketing efforts, and that the relator did not qualify as an original source. Disagreeing with the defendant’s arguments, the court emphasized that a relator need only “possess direct and independent knowledge of the ‘information’ on which her allegations are based, not of the ‘transaction.'” Id.

As such, the court relied upon precedent to explain that the bar does not require a relator to have direct and independent knowledge of “‘all of the vital ingredients to a fraudulent transaction.'” Id. (quoting United States ex rel. Springfield Terminal Ry. Co. v. Quinn, 14 F.3d 645, 656–57 (D.C. Cir. 1994)). In light of the statute’s specific wording and the fact that the government “already knows about communications made to [it] by an alleged defrauder,” the court concluded that a relator’s “‘direct and independent knowledge of any essential element of the underlying fraud transaction'” is enough to afford “original-source status under the [FCA].” Id. (quoting Springfield, 14 F.3d at 657). The Eighth Circuit ultimately remanded the matter to the district court to determine whether the relator possessed direct and independent knowledge of the “true state of the facts,” specifically whether the defendant had evidence of the inefficacy and risks of the product at issue. Id.

D. Developments in Application of the First-to-File Bar

The FCA’s so-called “first-to-file bar” limits the ability of qui tam relators to bring an action based on facts already at issue in another pending FCA matter. Specifically, the statute provides that, when a qui tam action is “pending,” “no person other than the Government may intervene or bring a related action based on the [same] facts.” 31 U.S.C. § 3730(b)(5). In the past six months, the Fourth and D.C. Circuits weighed in on what, if any, impact the resolution of the original action would have on an ongoing suit that otherwise would run afoul of the first-to-file bar, as well as the ability of relators to avoid the first-to-file bar by amending the later-filed complaint.

In United States ex rel. Carter v. Halliburton Co., 866 F.3d 199, 203 (4th Cir. 2017), following a complicated procedural history that culminated in an appeal before the Supreme Court, the Fourth Circuit faced both of these questions. The Fourth Circuit first found the bar applies, even if the earlier-filed action has since been dismissed. The Court held that the “appropriate reference point for a first-to-file analysis is the set of facts in existence at the time that the FCA action under review is commenced,” and that “[f]acts that may arise after the commencement of a relator’s action, such as the dismissals of earlier-filed, related actions pending at the time the relator brought his or her action, do not factor into this analysis.” Id. at 207. Referencing the Supreme Court, which described the first-to-file rule as “one of ‘a number of [FCA] provisions that do require, in express terms, the dismissal of a relator’s action,'” the Fourth Circuit held that it must dismiss the action without prejudice, even though the statute of limitations could prevent the relator from re-filing. Id. at 209 (quoting State Farm Fire & Cas. Co. v. United States ex rel. Rigsby, 137 S.Ct. 436, 442–43 (2016)). Next, the Fourth Circuit rejected the argument that a relator could propose amendments to the complaint (to file after the earlier case had been dismissed) and that such would cure the first-to-file bar: the “proposed amendment simply adds detail to [the relator’s] damages theories,” instead of “address[ing] any matters potentially relevant to the first-to-file rule, such as the dismissals of the [other actions].” Id. at 210.

The D.C. Circuit, in United States ex rel. Shea v. Cellco Partnership, 863 F.3d 923, 930 (D.C. Cir. 2017), came to a similar conclusion. There, the court held that the relator’s action “was incurably flawed from the moment he filed it,” because the relator’s earlier-filed separate action was still pending at the time. This was true even though the earlier-filed action was subsequently settled and dismissed. Id. at 927. On appeal, a divided panel affirmed, interpreting the bar to apply even when the initial action was no longer pending, since it had been “pending” at the time the second action was actually filed. Id. at 928. The D.C. Circuit also agreed with the district court that the relator could not amend his complaint, holding that it could not salvage his claims from the first-to-file bar and that the relator would need to re-file a new action if he wanted to litigate further. Id.

These cases stand in contrast to United States ex rel. Gadbois v. PharMerica Corp., 809 F.3d 1, 6 (1st Cir. 2015), discussed in a previous update, which effectively found a relator could amend his complaint, after a prior case had been dismissed, to avoid the first-to-file bar. This sets up a potential split of authority that may eventually reach the Supreme Court.

E. The Ninth Circuit Examines the Scope of the Government-Action Bar

Although the public disclosure bar and first-to-file bar are more commonly litigated, they are not the only bars that apply in FCA cases. The related “government-action bar” prohibits a relator from bringing a qui tam suit “based upon allegations or transactions which are the subject of a civil suit . . . in which the Government is already a party.” 31 U.S.C. §3730(e)(3). In a case of first impression, the Ninth Circuit recently clarified the reach of the government-action bar in a decision with potentially important ramifications for companies facing FCA liability. United States ex rel. Bennett v. Biotronik, Inc., 876 F.3d 1011 (9th Cir. 2017).

The case concerned a relator who tried to bring an FCA suit against a company that had already settled similar allegations with the government in a different suit, brought by a separate relator. Id. at 1014–15. The second relator argued that, because the first suit was no longer pending, the government-action bar no longer barred his subsequent suit. Affirming summary judgment for the defendant company, the Ninth Circuit held “that the government-action bar applies even when the Government is no longer an active participant in an ongoing qui tam lawsuit.” Id. at 1016. In so holding, the court rejected arguments that the government was no longer a “party” in a suit it has settled. Id. at 1019–20.

Notably, the court also held that when the government-action bar applies, it applies to all claims that overlap with the earlier-settled suit, regardless of whether those specific claims were part of the government settlement. In other words, if the government settles a qui tam action, that settlement bars subsequent suits based on any of the theories advanced by the original suit, regardless of whether those specific theories were investigated and included in the settlement. Id. at 1020–21. According to the Ninth Circuit, so long as “the Government was made aware of the claims it ultimately chose not to settle,” the government became “a ‘party’ to the suit as a whole,” and the government-action bar therefore likewise applies to the “suit as a whole.” Id. at 1021.

This provides an important point of reference for defendants, particularly those who face repeated FCA actions, to evaluate how earlier FCA actions may affect the viability of new cases. Based on Bennett, claims that were involved in—but not settled by—government-settled cases may be off limits from further litigation by other relators.

F. The Fifth and Seventh Circuits Explore Causation Under the FCA

For years, the Seventh Circuit stood as the sole circuit to apply a “but for” causation standard for damages in FCA cases, allowing plaintiffs to recover for those events that were “but for” caused by the alleged misconduct, even if the alleged misconduct was not a predominant or primary cause of the event at issue. In Luce, discussed above, the Seventh Circuit finally joined its sister circuits by requiring that plaintiffs also show proximate causation, not just “but for” causation, to establish damages in an FCA matter.

The case involved allegations that the defendant “had defrauded the Government by falsely asserting that he had no criminal history so that his company could participate in the FHA’s insurance program.” 873 F.3d at 1000. The district court, applying the Seventh Circuit’s prior “but for” causation standard, granted summary judgment for the government, finding the defendant could be liable for government-insured loans that later went into default because, without the defendant’s initial alleged false assertion, defendant would not have been able to participate in the program. The district court found this should be the case, even if the loans went into default for reasons unrelated to the defendant’s actions (such as because of reasons associated with borrower hardship or other borrower-related reasons). Id. On appeal, the Seventh Circuit reversed, and reversed its view on causation. The Seventh Circuit, recognizing the unfair and inappropriate aspects of “but for” causation, found that a plaintiff should have to prove proximate causation, by showing both that the “defendant’s conduct was a material element and a substantial factor in bringing about the injury,” (cause in fact) and that “the injury is of a type that a reasonable person would see as a likely result of his or her conduct” (legal cause). Id. at 1012 (internal citations and quotations marks omitted). The Seventh Circuit remanded the case for further proceedings on the issue of proximate causation.