The English Supreme Court’s February 12, 2021 judgment in Okpabi and others v Royal Dutch Shell Plc and another [2021] UKSC 3 is a landmark decision in the field of human rights and environmental protection. In a unanimous ruling,[1] the Court allowed the claimants to continue with a claim that the UK-domiciled parent of a multinational group owed a duty of care to those allegedly harmed by the acts of a foreign subsidiary.

The judgment raises important issues regarding the proper approach to jurisdictional challenges and provides insight into the criteria that English courts will consider when determining questions of liability in respect of harm caused by foreign subsidiaries.

Background

In 2015, inhabitants of the Bille and Ogale communities in Nigeria brought parallel claims in negligence in England against UK company Royal Dutch Shell plc (‘RDS’) and its Nigerian subsidiary, the Shell Petroleum Development Company of Nigeria Limited (‘SPDC’). Both claims sought damages for allegedly serious pollution and environmental damage caused by oil leaks from pipelines that SPDC operated on behalf of an unincorporated joint venture. The claimants argued that RDS, the UK parent, owed them a duty of care because it exercised significant control over material aspects of SPDC’s operations and/or assumed responsibility for SPDC’s operations.

The defendants challenged the English court’s jurisdiction and sought to set aside service out of the jurisdiction on SPDC. Following a three-day hearing in November 2016, Mr Justice Fraser held that while the court had jurisdiction to try the claims against RDS, it was “not reasonably arguable that there [was] any duty of care upon RDS.” As a result, the conditions for granting permission to serve the claim on SPDC were not made out, and the Claimants’ case against RDS was struck out. The Claimants appealed.

The Court of Appeal hearing took place in November 2017. The Court considered that Fraser J had erred in his approach to the evidence, and decided that it was entitled to review the evidence for itself, including fresh evidence adduced on appeal. By that stage, some 43 witness statements and expert reports had been filed. In fact, the parties chose to “swamp” the Court of Appeal with evidence, with the witness statements running to more than 2,000 pages of material and eight files of exhibits.[2] Nevertheless, the Court of Appeal undertook a detailed review of the facts and, in February 2018, the majority upheld the judgment of Fraser J (Sales LJ dissenting).

The Claimants’ application for permission to appeal to the Supreme Court was stayed pending judgment in Vedanta Resources PLC and another v Lungowe and others [2019] UKSC 20, a case which the Supreme Court Justices acknowledged was “very relevant to both the procedural and the substantive issues raised on this appeal.”

The Supreme Court judgment in Vedanta

In the Vedanta litigation, a similar question arose as to whether a parent company, Vedanta Resources Plc, could be held liable for alleged acts of environmental damage in Zambia associated with the Nchanga copper mine and caused by its subsidiary, Konkola Copper Mines plc (“KCM”).

The Supreme Court was asked to decide whether the courts of England and Wales had jurisdiction to hear claims of common law negligence and breach of statutory duty against the parent and subsidiary. Among other things, the defendants asserted that the claimants’ pleaded case and supporting evidence disclosed no real triable issue: Vedanta could not be shown to have done anything in relation to the operation of the mine sufficient to give rise to a common law duty of care, or statutory liability under Zambian environmental protection, mining and public health legislation. Vedanta was, it was said, merely an indirect owner of KCM, and no more than that.

The Supreme Court rendered its decision in April 2019. In delivering the Supreme Court’s unanimous judgment, Lord Briggs confirmed that the appropriate test of whether there is a real issue to be tried replicates the summary judgment test; i.e. the question is whether the claim has a real prospect of success at trial.

Lord Briggs also made clear that the liability of parent companies in relation to activities of their subsidiaries is not, of itself, a distinct category of liability in negligence. Ordinary principles of the law of tort regarding the imposition of a duty of care should apply. On the facts, whether a duty of care arises “depends on the extent to which, and the way in which, the parent availed itself of the opportunity to take over, intervene in, control, supervise or advise the management of the relevant operations (including land use) of the subsidiary” (para 49). The Supreme Court held, among other things, that it was “well arguable that a sufficient level of intervention by Vedanta in the conduct of operations at the Mine may well be demonstrable at trial, after full disclosure of the relevant internal documents […].” (para 61). The question whether Vedanta owed a duty of care was, therefore, a real triable issue and for this, and other reasons, the English court had jurisdiction to hear the claim.

Okpabi: the arguments

The claimants

|

The claimants in Okpabi amended their case in light of the Vedanta ruling, and argued that there were four “routes” by which RDS could be shown to owe the claimants a duty of care:

|

The above routes are, therefore, guides to the sorts of issues that claimants will explore in seeking to demonstrate that a parent company has intervened in the business of the subsidiary to such a degree that it owes a duty of care to individuals harmed by the activities of that subsidiary.

With regard to the evidence, the claimants relied, among other things, on the fact that RDS had enforced mandatory group-wide health and safety policies, had centralised expertise and exercised top-down control of the health, safety, security and environmental areas of the business, and/or had joint management of the response to the oil spills. The claimants also relied on public Shell documents such as sustainability reports, and on material said to show that RDS had detailed knowledge of the environmental damage caused by SPDC. They relied on two documents in particular; the RDS Control Framework and the RDS HSSE Control Framework (the Health, Security, Safety and Environment framework). The former allegedly showed that the Shell Group was organised along “Business” and “Function” lines directly accountable to RDS and the RDS HSSE Control Framework was said to show the extent of control that the RDS Board exercised over the health, safety and environmental practices of its subsidiaries.

The defendants

The defendants argued that RDS could not be responsible for environmental pollution caused by third-party acts of theft, sabotage and pipeline interference; while RDS has mandatory policies and guidelines in place, it leaves their enforcement and implementation to subsidiaries; and although it requires subsidiaries to have health and safety audits, it leaves overall control over pipelines and related infrastructure to subsidiaries.

|

The Supreme Court judgment in Okpabi The jurisdiction question

The factual questions

|

Comment

The decision in Okpabi concludes an extremely important chapter on the court’s approach to claims alleging a duty of care on the part of the parent for harm said to be caused by a foreign subsidiary. On jurisdiction, and on the question whether there is a real issue to be tried, the court will not conduct a mini-trial. Defendants need to be aware that the vast reams of evidence in Okpabi were not enough to stop the claim: at this interlocutory stage the court will remain focussed on the facts alleged in the particulars of claim, and accept them unless they are demonstrably untrue or unsupportable. Alternative routes are available, however, by which cases may be resisted on the right facts, such as limitation challenges, and/or an application that the case be struck out as an abuse of process.

Further, parent companies should not take false comfort in the local implementation of global policies, and should consider carefully how management, supervision, advice and policy are handled. Ultimately, each case will turn on its own facts.

While the decision may bring clarity to the legal and factual questions at issue, like Vedanta, it also highlights the enduring difficulty for corporates trying to establish good governance, particularly in group structures where subsidiaries operate independently with local oversight and implementation of policy. As discussed in our separate client alert, European legislation may be in the pipeline, requiring parent companies to conduct human rights, environmental and good governance due diligence throughout their value chain. Importantly, the current draft of that legislation expressly includes subsidiaries in the definition of value chain. With many UK parent companies having a European commercial footprint (and therefore falling within scope of the European initiative), litigation of this nature is likely only to increase.

In the meantime, the Okpabi matter will return to the High Court to proceed on the merits, with scrutiny of liability, quantum and potential additional jurisdictional challenges yet to come.

___________________

[1] For the purposes of the Judgment, the Court was deemed constituted without Lord Kitchin, who was absent due to illness.

[2] See paragraph 105 of Lord Hamblen’s judgment in the Supreme Court and paragraphs 17 and 18 of Simon LJ’s judgment in the Court of Appeal.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding the above developments. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, any member of the firm’s Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Practice, or the following authors in London:

Susy Bullock (+44 (0) 20 7071 4283, sbullock@gibsondunn.com)

Allan Neil (+44 (0) 20 7071 4296, aneil@gibsondunn.com)

Stephanie Collins (+44 (0) 20 7071 4216, scollins@gibsondunn.com)

© 2021 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.

New York partner Alexander Southwell is the author of “What’s to Come for Cybersecurity in the Biden Era,” [PDF] published by The National Law Journal on February 10, 2021.

With the emergence of COVID-19, 2020 was a year of significant and unprecedented change in daily life and the economy. In particular, 2020 was a busy year for Employee Retirement Income Security Act (“ERISA”) lawsuits—across industries—implicating employers’ retirement and healthcare plans. Not only were there significant decisions on a number of key issues impacting these lawsuits, but COVID-19 also triggered new and different legal exposure for plan sponsors and administrators. Recognizing the importance of this area of law to its clients, in 2020, Gibson Dunn launched an ERISA Disputes Practice Area, bringing together the Firm’s deep knowledge base and significant experience from across a variety of its award-winning practice groups, including: Executive Compensation & Employee Benefits, Class Actions, Labor & Employment, Securities Litigation, FDA & Health Care, and Appellate & Constitutional Law.

This 2020 year-end update summarizes key legal opinions and provides helpful analysis to assist plan sponsors and administrators navigating this unprecedented time.

Section I highlights four notable opinions from the United States Supreme Court addressing ERISA’s statute-of-limitations, Article III standing, and ERISA preemption. The Court also remanded a case to the Second Circuit concerning the pleading standard for alleging a breach of the duty of prudence under ERISA on the basis of a failure to act on insider information.

Section II provides a summary of hot topics in ERISA class-action litigation, including notable developments in fiduciary breach litigation and a growing trend of COBRA notice litigation.

Section III addresses evolving procedural issues, including the standard of review of benefits claim decisions, and an emerging circuit split on the arbitrability of claims brought on behalf of plans.

Section IV offers an overview of key issues in health plan litigation, including trends in behavioral health and residential treatment coverage disputes, and updates on assignments and anti-assignment clauses.

I. Significant Activity in the Supreme Court

2020 saw a significant rise in ERISA cases reaching the United States Supreme Court. In fact, the Court decided four ERISA cases in 2020, which is more than the Court has decided in any other year of the statute’s 45-year existence. These decisions provide helpful guidance to litigants on important topics in ERISA litigation. In Intel Corp. Investment Policy Committee v. Sulyma, 140 S. Ct. 768 (2020), the Court resolved a circuit conflict regarding when employers and plan fiduciaries can invoke the three-year statute of limitations period under Section 413(2) for an alleged breach of fiduciary duty. In Thole v. U.S. Bank N.A., 140 S. Ct. 1615 (2020), addressing fiduciary breach claims against a defined-benefit pension plan, the Court clarified when participants in an ERISA plan have Article III standing to sue for statutory violations. In Rutledge v. Pharmaceutical Care Management Ass’n, 141 S. Ct. 474 (2020), the Court again addressed the scope of ERISA preemption, particularly with respect to state regulations of health care and prescription drug costs, as well as state regulations of intermediaries. Finally, in Retirement Plans Committee of IBM v. Jander, 140 S. Ct. 592 (2020), the Supreme Court was expected to address whether the “more harm than good” pleading standard from Fifth Third Bancorp v. Dudenhoeffer, 573 U.S. 409, 430 (2014), can be satisfied by generalized allegations that the harm resulting from the inevitable disclosure of an alleged fraud generally increases over time, but instead, in a per curiam decision, declined to rule on the merits and remanded the case to the Second Circuit.

A. Intel Corp. Investment Policy Committee, et al. v. Sulyma Addresses Statute of Limitations

In Intel Corp. Investment Policy Committee, et al. v. Sulyma, 140 S. Ct. 768 (2020), the Supreme Court addressed the circumstances in which employers and plan fiduciaries can invoke ERISA’s three-year statute of limitations for an alleged breach of fiduciary duty, unanimously holding that in order to trigger the three-year limitations period, an employee must have become “aware of” the plan information and that a fiduciary’s disclosure of plan information alone does not meet the “actual knowledge” requirement.

The plaintiff, a former employee of Intel, sued Intel’s investment committee, administrative committee and finance committee (collectively, “Intel”), alleging that his retirement plans improperly overinvested in alternative investments. Id. at 774. Under Section 413(1) of the Employment Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA), breach of fiduciary duty claims may be brought within six years of the breach or violation. However, Section 413(2) of ERISA shortens the limitations period to “three years after the earliest date on which the plaintiff had actual knowledge of the breach or violation.” 29 U.S.C. § 1113(2). Plaintiff filed suit within six years of the alleged breaches but more than three years after petitioners had disclosed their investment decisions to him. Sulyma, 140 S. Ct. at 774. While Intel provided records showing that the plaintiff had received numerous disclosures explaining the extent to which his retirement plans were invested in alternative assets, the plaintiff testified in a deposition that he didn’t remember reviewing the disclosures and also stated in a declaration that he was unaware that his account was invested in alternative investments. Id. at 775.

The Court unanimously affirmed the Ninth Circuit’s decision holding that a plaintiff does not necessarily have “actual knowledge” based on receipt alone of information if he did not read it. Id. at 779. While the disclosure of information to plaintiff is “no doubt relevant in judging whether he gained knowledge of that information,” to meet § 1113(2)’s “actual knowledge” requirement, the plaintiff must have become aware of that information. Id. at 777. The Court emphasized that its decision does not foreclose any of the “usual ways” to prove actual knowledge at any stage in litigation—including through proof of willful blindness—and that the decision will not prevent defendants from using circumstantial evidence to show actual knowledge. Id. at 779.

Gibson Dunn submitted an amicus brief on behalf of the National Association of Manufacturers, the American Benefits Counsel, the ERISA Industry Committee, and the American Retirement Association in support of petitioner: Intel Corp. Investment Policy Committee.

As we discussed in our Appellate Update on the Sulyma decision, we expect the Court’s holding to lead to an uptick in lawsuits against employers and plan fiduciaries, based on allegations that the three-year limitations period is inapplicable because they did not read or cannot recall reading plan documents.

B. Thole v. U.S. Bank N.A. Addresses Article III Standing

As we reported in our Appellate Update, in June of last year, the Supreme Court held that participants in a fully funded defined-benefit pension plan lacked Article III standing to sue under ERISA for breach of fiduciary duties because they had no “concrete stake in the lawsuit.” Thole v. U.S. Bank N.A., 140 S. Ct. 1615, 1619 (2020). The plaintiffs in Thole alleged that the plan fiduciaries “violated ERISA’s duties of loyalty and prudence by poorly investing the assets of the plan,” resulting in a loss of $750 million. Id. at 1618. Defendants moved to dismiss for lack of standing, which the district court granted. Id. at 1619. The Eighth Circuit “affirmed on the ground that the plaintiffs lack[ed] statutory standing [under ERISA].” Id.

The Supreme Court, in a 5-4 decision authored by Justice Kavanaugh, affirmed on the ground that plaintiffs lacked Article III standing. Id. The Court explained that “[t]here is no ERISA exception to Article III” and that the plaintiffs lacked standing “for a simple, commonsense reason: They have received all of their vested pension benefits so far, and they are legally entitled to receive the same monthly payments for the rest of their lives.” Id. at 1622. Accordingly, the Court reasoned that the plaintiffs did not have a “concrete stake in the lawsuit” as “[w]inning or losing [the] suit would not change the plaintiffs’ monthly pension benefits.” Id.

In so ruling, the Court rejected each of the four theories plaintiffs raised to demonstrate their standing. Id. at 1619–21. First, the Court rejected plaintiffs’ argument, based on trust-law principles, that they have an equitable or property interest in the plan. Id. at 1619–20. The Court reasoned that “a defined-benefit plan is more in the nature of a contract” than a trust as “[t]he plan participants’ benefits are fixed and will not change, regardless of how well or poorly the plan is managed.” Id. at 1620. Second, the Court held that plaintiffs lacked standing to sue “as representatives of the plan itself” because they had not been “legally or contractually appointed to represent the plan.” Id. Third, the Court found that even though ERISA affords all participants “a general cause of action to sue” it does not “affect the Article III standing analysis.” Id. Fourth, and finally, the Court rejected plaintiffs’ argument that defined-benefit plans will not be “meaningfully regulate[d]” if plan participants lack standing to sue as employers have “strong incentives” to manage plans and the Department of Labor can “enforce ERISA’s fiduciary obligations.” Id. at 1621.

In a concurring opinion, Justice Thomas, joined by Justice Gorsuch, objected to the Court’s “practice of using the common law of trusts as the ‘starting point’ for interpreting ERISA” and recommended that the Court “reconsider our reliance on loose analogies in both our standing and ERISA jurisprudence.” Id. at 1623. The concurrence called for the Court to return to a “simpler framework” for standing, and one in which the party must show injury to private rights. Justice Thomas stated there was no such injury in Thole because the private rights the petitioners alleged were violated did not belong to them; they belonged to the plan, and petitioners had no legal or equitable ownership interest in the plan assets. Id.

The Supreme Court’s decision in Thole is welcome news to plan sponsors, fiduciaries, and administrators, all of whom can now rely on this decision to argue that participants of ERISA plans cannot sue for breach of fiduciary duty unless they have a “concrete stake in the lawsuit,” such as a failure by the plan to make required benefits payments. Id. at 1619. In addition, Thole—and in particular Justice Kavanaugh’s forceful statement that “[t]here is no ERISA exception to Article III”—provides strong support for application of Article III requirements and jurisprudence to cases brought under ERISA.

More litigation is ahead on these issues. For instance, a split among district courts has developed on the question of whether participants in defined-contribution plans have standing to bring claims challenging investments in which they did not personally invest. Compare Cryer v. Franklin Templeton Res., Inc., 2017 WL 4023149, at *4 (N.D. Cal. July 26, 2017) (holding plaintiff had standing to sue for funds “in which he did not invest” because “the lawsuit seeks to restore value to and is therefore brought on behalf of the [p]lan”); McDonald v. Edward D. Jones & Co., L.P., 2017 WL 372101, at *2 (E.D. Mo. Jan. 26, 2017) (finding that “a plan participant may seek recovery for the plan even where the participant did not personally invest in every one of the funds that caused an injury to the plan”), with Wilcox v. Georgetown Univ., 2019 WL 132281, at *9–10 (D.D.C. Jan. 8, 2019) (finding that plaintiffs did not have standing to challenge options in which they did not invest); Marshall v. Northrop Grumman Corp., 2017 WL 2930839, at *8 (C.D. Cal. Jan. 30, 2017) (holding that plan participants lacked standing because they failed to allege that they invested in the particular fund). Since the Supreme Court made clear that injuries to the plan do not necessarily confer standing to the plan participants, Thole may support the argument that plaintiffs lack standing to bring suit when they did not personally invest in a challenged plan investment option. It remains to be seen whether, going forward, the courts adopt this interpretation of Thole to set limits on Article III standing in defined-contribution plan suits.

C. Rutledge v. Pharmaceutical Care Management Association Narrows ERISA Preemption

On December 10, 2020, the Supreme Court issued an 8-0 decision (Justice Barrett did not participate) in Rutledge v. Pharmaceutical Care Management Association holding that ERISA did not preempt an Arkansas statute regulating the rates at which pharmacy benefit managers reimburse pharmacies for prescription drug costs. Justice Sotomayor, who authored the opinion on behalf of the unanimous Court, relied on “[t]he logic of” the Court’s previous decision in New York State Conference of Blue Cross & Blue Shield Plans v. Travelers Ins. Co., 514 U.S. 645 (1995), to conclude that the Arkansas law “is merely a form of cost regulation . . . [that] applies equally to all PBMs and pharmacies in Arkansas,” and therefore is not subject to ERISA preemption because it did not have an impermissible connection with or reference to ERISA. 141 S. Ct. 474, 481 (2020). Rutledge is likely to be viewed by regulators as supporting state authority to regulate health care costs without running afoul of ERISA preemption. (Gibson Dunn’s Appellate Update discussing this case can be found here). Gibson Dunn submitted an amicus brief on behalf of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce in support of the Pharmaceutical Care Management Association.

In Rutledge, the Court ruled that “ERISA is . . . primarily concerned with pre-empting laws that require providers to structure benefit plans in particular ways,” which include those that require “payment of specific benefits,” those that bind “plan administrators to specific rules for determining beneficiary status,” and those where “acute, albeit indirect, economic effects of the state law force an ERISA plan to adopt a certain scheme of substantive coverage.” Id. at 480. The Court found that the need for regulatory uniformity—in particular, cost uniformity—is not absolute, and that it does not alone justify application of ERISA preemption: “[N]ot every state law that affects an ERISA plan or causes some disuniformity in plan administration has an impermissible connection with an ERISA plan,” which the Court noted is “especially so if a law merely affects costs.” Id. The following sentence from the Court’s opinion encapsulates its holding: “ERISA does not pre-empt state rate regulations that merely increase costs or alter incentives for ERISA plans without forcing plans to adopt any particular scheme of substantive coverage.” Id.

The Rutledge decision will impact future litigation regarding the scope of ERISA preemption. In particular, state regulators likely will rely on this decision in seeking to insulate state laws concerning prescription drug prices and pharmacy benefit managers from preemption. The reach of Rutledge, however, likely will be tested even beyond this immediate context, because state regulators can be expected also to defend other state laws and regulations on the basis that they merely impact health care costs and lack the necessary connection with ERISA plans under Rutledge. States may also attempt to enact new statutes and issue regulations of those health care intermediaries and other service providers to covered plans.

ERISA preemption will continue to be a hot area this year with the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals hearing argument in Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association v. CA Secure Choice Retirement Savings Program later this month, for example. In that case, the Ninth Circuit will evaluate whether ERISA preempts California’s state-run auto-IRA program, which transfers portions of a person’s paycheck into a retirement account.

D. Retirement Plans Committee of IBM v. Jander Remands Questions About Dudenhoeffer Pleading Standard to Second Circuit

As we discussed in a recent Securities Litigation Update, in Retirement Plans Committee of IBM v. Jander, 140 S. Ct. 592, 594 (2020), the Supreme Court was slated to address whether the “more harm than good” pleading standard from Fifth Third Bancorp v. Dudenhoeffer, 573 U.S. 409, 430 (2014), “can be satisfied by generalized allegations that the harm of an inevitable disclosure of an alleged fraud generally increases over time.” In Dudenhoeffer, the Court held that, in order to state a claim for breach of the duty of prudence under ERISA on the basis of a failure to act on insider information, a complaint must plausibly allege an alternative action that the fiduciaries could have taken that would not have violated securities laws and that a prudent fiduciary in the same circumstances would not have viewed as more likely to harm the fund than to help it. 573 U.S. at 428.

In Jander, plaintiffs, IBM employees who participated in an employee stock ownership plan (ESOP) sponsored by IBM, sued IBM’s retirement plan fiduciary committee for breach of fiduciary duty, alleged that IBM misrepresented the value of its microelectronics division, thereby artificially inflating the value of company stock, and caused a drop in the stock price upon selling the microelectronics division. Jander v. Ret. Plans Comm. of IBM, 272 F. Supp. 3d 444, 446–47 (S.D.N.Y. 2017). Plaintiffs’ claims were dismissed by the district court on the basis that the complaint lacked context-specific allegations as to why a prudent fiduciary couldn’t have concluded that plaintiff’s hypothetical alternatives were more likely to do more harm than good, failing to satisfy the Dudenhoeffer pleading standard. Id. at 449–54.

The Second Circuit reversed, holding that plaintiffs had pled a plausible claim for violation of ERISA’s duty of prudence based on (1) the fiduciaries’ knowledge that the stock was inflated through accounting violations; (2) their power to disclose these accounting violations; and (3) their failure to promptly disclose the true value of the microelectronics division. Jander v. Ret. Plans Comm. of IBM, 910 F.3d 620, 628–31 (2d Cir. 2018). Ultimately, the Second Circuit held that if the fiduciaries knew that disclosure of the insider information was inevitable, then delaying this disclosure would cause more harm than good to the ESOP. Id. at 630.

In a per curiam decision issued on January 14, 2020, the Supreme Court declined to rule on the merits in Jander, and vacated and remanded the case for the Second Circuit to address two unresolved issues raised by the parties: (1) whether ERISA ever imposes a duty on a fiduciary for an ESOP to act on inside information, and (2) whether ERISA requires disclosures that are not otherwise required by the securities laws. 140 S. Ct. at 594–95. Justice Kagan (joined by Justice Ginsburg) and Justice Gorsuch issued concurring opinions, articulating differing views on how these questions should be resolved on remand. See id. at 595–96 (Kagan, J. concurring); id. at 596–97 (Gorsuch, J. concurring). On remand, the Second Circuit reinstated its original opinion, again reversing the district court’s decision. Jander v. Ret. Plans Comm. of IBM, 962 F.3d 85, 86 (2d Cir. 2020) (per curiam).

While not purporting to break new ground, the Court nevertheless noted two things. First, the Court explained that the Dudenhoeffer “more harm than good” standard is the correct standard to apply to ESOP fiduciaries. See 140 S. Ct. at 594. Second, the Court made clear that ERISA’s fiduciary duty of prudence does not require fiduciaries to act in a way that violates securities laws. See id. However, the opinion leaves unresolved whether there may be circumstances in which ESOP fiduciaries are required to act on the basis of inside information to benefit an ESOP, and whether the Dudenhoeffer standard requires ESOP fiduciaries to disclose information that is not required by federal securities laws. See id. at 594–95.

In recent cases following Jander, at least one district court has concluded that the Second Circuit’s decision should be classified as an outlier because “the overwhelming majority of circuit courts to consider an imprudence claim based on inside information post-Dudenhoeffer [have] rejected the argument that public disclosure of negative information is a plausible alternative.” Burke v. Boeing Co., No. 19-cv-2203, 2020 WL 6681338, at *5 (N.D. Ill. Nov. 12, 2020). Given this circuit split, plaintiffs may be more likely to target the Second Circuit for stock-drop and similar suits. However, in a recent decision from the Second Circuit, the court affirmed dismissal of an imprudence claim brought by a plaintiff who argued that two alternative actions—earlier disclosure and closure of the fund to additional investment—were “on par with those found sufficient in Jander.” Varga v. Gen Elec. Co., No. 20-1144, — F. App’x —-, 2021 WL 391602, at *2 (Feb. 4, 2021). The court found plaintiff’s allegations insufficient, conclusory, and not consistent with those in Jander, concluding that she had “failed to adequately plead alternative actions that the fiduciaries could have taken.” Id. at *2–3. Thus, while Jander remains good law in the Second Circuit, the Varga decision suggests that courts will still look closely at plaintiffs’ allegations of plausible alternative actions in the context of motions to dismiss.

II. Class Actions Continued To Be a Significant Focus of ERISA Litigation in 2020

The year 2020 was again a busy period in ERISA class-action litigation, particularly fiduciary-breach litigation. While large plans continue to be the primary targets of these lawsuits, plaintiffs are also targeting smaller plans—and some cases attempting to aggregate these claims by suing administrators or service providers to multiple plans. We discuss below two important circuit splits in the field of ERISA fiduciary-breach class actions, and also an emerging area of litigation concerning the required contents of COBRA notices.

A. Hot Topics in ERISA Fiduciary Breach Litigation

We continued to see significant activity in ERISA fiduciary-breach litigation in 2020, including on issues concerning (1) whether plaintiffs can state a fiduciary-breach claim based on offering a particular mix of investment options in a plan, and (2) whether single-stock funds are per-se imprudent under ERISA. We also may see changes regarding the rules governing whether investing in environmental, social, and corporate governance (“ESG”) funds could constitute a fiduciary breach under ERISA.

As to the first issue, the Seventh, Third, and Eighth Circuits have all recently addressed whether plaintiffs can state a fiduciary-breach claim by alleging that a plan offered certain underperforming investment options, as well as other unobjectionable options. In Divane v. Northwestern University, 953 F.3d 980 (7th Cir. 2020), the Seventh Circuit held that plaintiffs failed to allege a fiduciary breach by claiming that defendants provided investment options that were “too numerous, too expensive, or underperforming,” when the defendant also offered low-cost index funds, among other options that the plaintiffs found unobjectionable. Id. at 991–92. A few months after the Seventh Circuit’s decision in Divane, the Eighth Circuit appeared to adopt a more plaintiff-friendly interpretation by holding that plaintiffs could state a claim by alleging that “fees were too high” and that the defendants “should have negotiated a better deal.” Davis v. Wash. Univ. of St. Louis, 960 F.3d 478, 483 (8th Cir. 2020); see also Sweda v. Univ. of Pennsylvania, 923 F.3d 320, 330 (3d Cir. 2019) (stating that “a meaningful mix and range of investment options” does not necessarily “insulate[] plan fiduciaries from liability for breach of fiduciary duty”). These holdings may suggest to plaintiffs that the Third and Eighth Circuits will be more receptive to these types of claims, prompting an increase in fee-suit litigation in those jurisdictions.

Additionally, a circuit split may have recently developed concerning whether single-stock funds are per se imprudent plan offerings under ERISA. In May 2020, the Fifth Circuit affirmed the dismissal of a putative fiduciary breach class action in Schweitzer v. Investment Committee of Phillips 66 Savings Plan, 960 F.3d 190 (5th Cir. 2020). The court held that defendants satisfied their fiduciary duties to diversify and to act prudently because they provided plan participants with an array of investment options that “enable[d] participants to create diversified portfolios.” Id. at 196–98. Accordingly, the Fifth Circuit in Schweitzer rejected plaintiffs’ claim that “a single-stock fund is imprudent per se.” Id. at 197–98. But only a few months later, the Fourth Circuit held the opposite, concluding that defendants breached their fiduciary duty when offering a single-stock fund. Stegemann v. Gannett Co., 970 F.3d 465, 468 (4th Cir. 2020). The Fourth Circuit rejected the argument that “diversification must be judged at the plan level rather than the fund level,” holding that “each available fund on a menu must be prudently diversified.” Id. at 476–77 (emphasis added). In dissent, Judge Niemeyer argued that “the majority merge[d] the duties of diversification and prudence,” and, in effect, made it impossible for an employer to “ever prudently offer a single-stock, non-employer fund.” Id. at 484, 488. No other court has yet adopted the Fourth Circuit’s standard. Defendants in Stegemann filed a petition for a writ of certiorari, and on January 4, 2021, the Supreme Court called for a response from plaintiffs, indicating that the Justices may be interested in hearing the case.

Last, in the final year of the Trump administration, the Department of Labor (“DOL”) proposed and adopted a new rule that ERISA fiduciaries must make investment decisions “based solely on pecuniary factors”; and an investment intended “to promote non-pecuniary objectives” at the expense of sacrificing returns or taking on additional risk would constitute a breach of the fiduciary’s duty. Financial Factors in Selecting Plan Investments, 85 Fed. Reg. 72,846, 72,851, 72,848 (Nov. 13, 2020). Though the final version of the rule does not explicitly reference ESG funds, the DOL’s press release announcing the rule expressly stated that the rule’s purpose was to provide further guidance “in light of recent trends involving [ESG] investing.” U.S. Dep’t of Labor, U.S. Department of Labor Announces Final Rule to Protect Americans’ Retirement Investments (Oct. 30, 2020), https://www.dol.gov/newsroom/releases/ebsa/ebsa20201030. The new rule took effect on January 12, 2021, 85 Fed. Reg. at 72,885, and there have not yet been any cases addressing when and whether investment in an ESG fund could constitute a fiduciary breach. Notably, the new rule appears to conflict with many of the Biden administration’s stated environmental goals, and the DOL rule may be a target for reversal by the new administration.[1]

B. Growing Challenges Related to COBRA Notice

The year 2020 also saw a rise in COBRA notice litigation. The Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985 (COBRA) allows employees and their dependents the opportunity to continue to participate in their employer’s group health plan when coverage would otherwise be lost due to a termination of employment or other “qualifying event[s].” 29 U.S.C. § 1163. And plan administrators are required to provide notice to employees informing them of their right to elect COBRA coverage. 29 C.F.R. § 2590.606-4. COBRA mandates that the notice include specific information and be “written in a manner calculated to be understood by the average plan participant.” Id. § 2590.606-4(b)(4). Plaintiffs have filed numerous class actions against employers alleging technical violations in the language of the notices, seeking statutory penalties up to $110 per day for each participant that received inadequate notice.

Many COBRA notice lawsuits have been filed in Florida, with others filed in venues that include New York and South Carolina. The number of such lawsuits has recently been spurred by COVID-19 layoffs. Plaintiffs’ allegations are substantially similar across cases, and generally allege that COBRA notices were deficient for one or more of the following reasons:

- Notice failed to identify the name, address, and telephone number of the plan administrator;

- Notice failed to identify the qualifying event;

- Notice failed to explain how to enroll in COBRA coverage;

- Notice failed to provide all the required explanatory language regarding the coverage;

- Notice was not written in a manner calculated to be understood by the average plan participant; and/or

- Notice failed to comply with the model notice created by the Department of Labor (“DOL”).

The influx of COBRA notice litigation highlights the importance for employers of reviewing their COBRA notices to assess whether any changes may be necessary to ensure compliance with statutory guidelines and regulations. To assist employers, the DOL has issued model notices on its website that employers can review against their own notices to ensure they are in compliance. Employers who have outsourced COBRA administration should also periodically check in with their third-party administrators to confirm compliance with all guidelines and regulations and may want to consider clearly assigning responsibility for compliance with notice requirements in their vendor agreements.

III. Key Decisions on Important ERISA Procedural Issues

The courts also issued important guidance this year to ERISA practitioners, plan sponsors, and plan administrators concerning ERISA procedural issues. In particular, the courts issued rulings concerning the standard of review for benefits claims, and provided further guidance on the ability to compel arbitration of claims brought by participants on behalf of a plan. Both of these topics are discussed below.

A. The Evolving Abuse of Discretion Standard of Review

In 2020, courts continued to wrestle with the degree of deference owed to benefit determinations made by plan administrators. The well-established rule is that a court reviews the plan administrator’s decision de novo unless the terms of the benefit plan give the administrator discretion to interpret the plan and award benefits. See Firestone Tire & Rubber Co. v. Bruch, 489 U.S. 101, 115 (1989). Where the plan terms grant this discretion to the administrator, courts review the administrator’s determinations under a deferential “abuse of discretion” standard (or arbitrary and capricious review, as some circuits call it). Id. Because it is common for benefit plans to give the administrator this discretion, the deferential standard often applies, and the Supreme Court has repeatedly parried attempts by plaintiffs to strip administrators of this deference. See Metro. Life Ins. Co. v. Glenn, 554 U.S. 105, 115 (2008) (abuse of discretion standard applies even when administrator has conflict of interest); Conkright v. Frommert, 559 U.S. 506, 522 (2010) (abuse of discretion standard applies even when court of appeals found previous related interpretation by administrator to be invalid).

Last year, plaintiffs persisted in their efforts to curtail the deferential abuse of discretion standard, and they found success in some instances. For example, in Lyn M. v. Premera Blue Cross, 966 F.3d 1061 (10th Cir. 2020), even though the plan gave the administrator discretion, the court nonetheless held that a de novo standard applied because plan members “lacked notice” of the discretion. Id. at 1065. The administrator failed to disclose the document granting discretion, and the plan summary it did disclose “said nothing about the existence” of that document. Id. at 1067. To preserve plan discretion under Lyn M., plan documents—including the summary plan description that plans are required to provide to their members—should disclose either the grant of discretion to the administrator or the precise document conferring that discretion.

Additionally, even when an abuse of discretion standard is found to apply, courts have developed ways to limit the degree of deference given to plan administrators. The Ninth Circuit, for example, continues to apply varying degrees of “skepticism” to the administrators’ determinations—as part of abuse of discretion review—when certain factors such as a conflict of interest are present. The precise degree of skepticism applied may provide a focal point for appellate review. In Gary v. Unum Life Insurance Co. of America, 831 F. App’x 812 (9th Cir. 2020), the circuit held that the district court “applied the incorrect level of skepticism to its abuse-of-discretion review.” Id. at 814. The district court had applied a “moderate degree” of skepticism because it found that the plan administrator had a structural conflict of interest (based on the district court’s belief that the administrator was responsible both for assessing and paying out claims) and had failed to afford the plaintiff a “full and fair review.” Id. at 813. But the Ninth Circuit held that, viewing the evidence in the light most favorable to the plaintiff, the circumstances in the case called for an even “higher degree of skepticism.” Id. This heightened skepticism was warranted, in the court’s view, because it found that the administrator’s consultants had “cherry-picked certain observations from medical records numerous times,” the administrator had not conducted an in-person examination of the plaintiff, and the administrator had reversed in part its initial decision denying benefits in full. Id. at 814. This decision suggests that, at least in the Ninth Circuit, courts may limit the degree of deference afforded to administrators—even under an abuse of discretion review—in particular circumstances.

However, not all circuits have been so receptive to plaintiffs’ efforts. The Eighth Circuit recently clarified its case law in this area, holding that, despite what an older circuit decision may have suggested and whatever other circuits may hold, a plan administrator’s delay in deciding an appeal of a benefits denial does not warrant de novo review. McIntyre v. Reliance Standard Life Ins. Co., 972 F.3d 955, 960, 964–65 (8th Cir. 2020). As with a conflict of interest, such delay is just a factor to be considered when applying abuse of discretion review. Id. at 965. The First Circuit also recently reaffirmed “the importance of giving deference” to plan administrators. Arruda v. Zurich Am. Ins. Co., 951 F.3d 12, 24 (1st Cir. 2020). The plaintiff in Arruda argued that courts can find an administrator’s decision arbitrary even when the administrator “relied on several independent experts” and a record consistent with its benefits determination. Id. at 21–22, 24. The First Circuit disagreed, finding this proposal to be “in considerable tension with” the abuse of discretion standard. Id. at 24.

Last year also saw circuit courts rebuff creative attempts by plaintiffs to avoid abuse of discretion review. For instance, in Ellis v. Liberty Life Assurance Co. of Boston, 958 F.3d 1271 (10th Cir. 2020), petition for cert. filed, (U.S. Jan. 8, 2021) (No. 20-953), all parties agreed that the plan conferred discretion on the administrator, and the plan provided that it was governed by the law of Pennsylvania, but the plaintiff sought de novo review on the ground that a Colorado statute prohibited grants of discretion in insurance policies. Id. at 1275. The court rejected the plaintiff’s argument that Colorado law should apply, holding that the law of the state selected by a plan’s choice-of-law provision normally applies, “to effectuate ERISA’s goals of uniformity and ease of administration.” Id. at 1280. Notably, the court observed that this choice-of-law question “could be avoided if ERISA preempts the Colorado statute,” but it declined to resolve this preemption issue, leaving it open for future litigation. Id. at 1279.

Finally, in Davis v. Hartford Life & Accident Insurance Co., 980 F.3d 541 (6th Cir. 2020), once again all parties agreed that the plan conferred discretion to the administrator, but the plaintiff contended that the administrator exercised no discretionary authority because a different company in the same corporate family had actually made the decision to terminate benefits. See id. at 545–46. But the Sixth Circuit found this argument “d[id] not add up as a factual matter.” Id. at 546. Even though the plan’s decisionmakers received their salaries from the other company, they were still adjudicating claims under the administrator’s policies, not the other company’s policies. Id. This precedent presents a potential obstacle for future plaintiffs who try to use the structure of a plan administrator’s corporate family as a backdoor means of securing de novo review.

B. A Possible Split on Arbitrability of ERISA § 502(a)(2) Claims

Arbitrability of ERISA section 502(a)(2) fiduciary-breach claims brought on behalf of a plan continued to be a hot topic in 2020 as courts applied key appellate decisions in this space from 2018 and 2019. In 2018, the Ninth Circuit held that section 502(a)(2) claims belong to the Plan, not the individual employee(s), and thus individual arbitration agreements that bound plan participants to arbitrate could not be used to compel the arbitration of claims brought on behalf of the plan. Munro v. Univ. of S. Cal., 896 F.3d 1088, 1092 (9th Cir. 2018). One year later, the court accordingly held that § 502(a)(2) claims are, in fact, arbitrable when the Plan has agreed to arbitration. Dorman v. Charles Schwab Corp., 780 F. App’x 510, 513–14 (9th Cir. 2019). According to the Ninth Circuit, “[t]he relevant question is whether the Plan agreed to arbitrate the § 502(a)(2) claims,” and when a “Plan [does] consent in the Plan document to arbitrate all ERISA claims,” a mandatory arbitration agreement is enforceable. Id. (emphasis added). Hence, in the Ninth Circuit, even when an individual employee has “agreed to arbitrate their claims in their employment contracts,” a § 502(a)(2) claim belongs to the plan and “that claim is not subject to arbitration unless the plan itself has consented.” Ramos v. Natures Image, Inc., 2020 WL 2404902, at *6–7 (C.D. Cal. Feb. 19, 2020) (emphasis added). Meanwhile, as noted in one of our recent class action updates, the Supreme Court has continued to enforce arbitration provisions in various contexts, and these decisions can be brought to bear in ERISA cases as well.

A circuit split may now be emerging on this issue. In Smith v. Greatbanc Trust Co., the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois rejected the Ninth Circuit’s holding in Dorman, even though in Smith (like Dorman) the plan documents indicated that the plan agreed to arbitrate. 2020 WL 4926560, at *3–4 (N.D. Ill. Aug. 21, 2020), appeal docketed, No. 20-2708 (7th Cir. Sept. 9, 2020). The court in Smith concluded that failure to notify a former employee (who remained a participant in the plan) of changes to the plan that compelled arbitration was inconsistent with ERISA’s notice requirements, and that, to the extent the arbitration agreement served as a “waiver of a party’s right to pursue statutory remedies,” the agreement was unenforceable. Id. (quoting Am. Express Co. v. Italian Colors Restaurant, 570 U.S. 228, 235–36 (2013)). The case is now pending appeal.

These decisions provide important guidance for employers considering amending their plans (or other plan-related documents, such as administrative services contracts) to include arbitration provisions. Under the Ninth Circuit’s Dorman decision, arbitration provisions in the plan documents can be used to bind the plan and to compel arbitration of claims brought on behalf of the plan. The Smith decision, however, underscores the importance of providing plan participants notice of any changes to plans, such as the addition of arbitration provisions, that would potentially impact participants’ rights to pursue statutory remedies.

IV. ERISA Health Plan Litigation

Finally, litigation concerning health plans remains a substantial part of the ERISA litigation landscape. In 2020, the federal courts of appeals addressed a significant number of disputes over behavioral-health coverage and issued a wide range of decisions addressing plan participants’ ability to assign their rights to providers.

A. Behavioral Health and Residential Treatment

ERISA disputes over behavioral-health coverage and residential treatment remained a significant source of litigation and appeals in 2020. Appellate decisions in this area mainly involved individual claims by patients challenging coverage determinations. Last year the courts of appeals decided at least 9 cases involving the denial of coverage for behavioral-health treatment, each of which involved individual claims by patients.

In disputes over individual coverage, the appellate courts in 2020 tended to afford significant deference to plan administrators’ determinations that behavioral-health treatment—and in particular residential treatment—was not medically necessary or did not qualify as emergency care. For example:

- In Doe v. Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, Inc., the First Circuit affirmed a district judge’s application of de novo review when she found that a patient’s residential treatment for psychological illness was medically unnecessary because medical experts had concluded that the patient did not require 24-hour supervision, her condition could be managed at a lower level of care, and medication had improved her condition before treatment. 974 F.3d 69, 72–74 (1st Cir. 2020).

- In Tracy O. v. Anthem Blue Cross Life & Health Insurance, the Tenth Circuit concluded that Anthem did not act arbitrarily and capriciously in denying coverage for a residential stay at a psychiatric facility because Anthem reasonably relied on four doctors’ conclusions that the patient’s condition had not significantly deteriorated and that her behavior could be managed in an outpatient setting. 807 F. App’x 845, 853–55 (10th Cir. 2020).

- In Brian H. v. Blue Shield of California, the Ninth Circuit affirmed a district judge’s determination that Blue Shield had not abused its discretion because it reasonably relied on expert opinions that a patient’s stay at a residential-treatment facility was not medically necessary because he would not have posed a danger to himself or others if treated in a less intensive setting. 830 F. App’x 536, 537 (9th Cir. 2020).

- In Meyers v. Kaiser Foundation Health Plan, Inc., the Ninth Circuit affirmed a district judge’s conclusion that Kaiser (regardless of whether de novo or abuse-of-discretion review applied) properly denied coverage for a patient’s out-of-network residential treatment because it did not meet the plan’s requirements for out-of-network coverage: It did not qualify as emergency services and, even if the treatment was unavailable in-network, the patient did not obtain Kaiser’s permission prior to treatment. 807 F. App’x 651, 653–54 (9th Cir. 2020).

- In Todd R. v. Premera Blue Cross Blue Shield of Alaska, 825 F. App’x 440, 441–42 (9th Cir. 2020), the Ninth Circuit, vacating the district court’s de novo judgment for the plaintiffs, held that a plan administrator correctly determined that a medical policy’s criteria for residential treatment were not met but remanded for the district court to consider in the first instance the plaintiff’s argument that those criteria were improper.

In each of these decisions, the court of appeals accorded deference to individual denials of coverage by administrators. By contrast, in Katherine P. v. Humana Health Plan, Inc., 959 F.3d 206, 209 (5th Cir. 2020), the Fifth Circuit determined that the district judge improperly granted summary judgment to the plan administrator. The Fifth Circuit reaffirmed prior precedent holding that when review of a coverage determination is de novo, the ordinary summary-judgment standard applies and a material dispute of fact should be decided by a bench trial. Id. The panel thus vacated the district judge’s grant of summary judgment to a plan administrator and remanded for the district judge to decide a dispute of material fact about whether treatment at a level of care less intense than partial hospitalization had been unsuccessful in controlling the plaintiff’s eating, purging, and compulsive exercise. Id. at 209–10; see also Lyn, 966 F.3d at 1064 (remanding for district court to apply de novo review to residential treatment claim rather than abuse of discretion standard).

Given the broad judicial deference ordinarily accorded to plan administrators’ medical determinations, plaintiffs have sought other grounds for challenging denials of coverage for behavioral healthcare. One common strategy is to invoke the federal Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act, and related state parity acts, which require that health plans provide equal coverage for mental illnesses and physical illnesses. In Stone v. UnitedHealthcare Insurance Co., for instance, the plaintiff alleged that the health plan and its administrator violated the federal and California mental health parity acts when they refused to cover her daughter’s out-of-state residential-care treatment, but the Ninth Circuit affirmed the judgment for the defendants. 979 F.3d 770, 774–77 (9th Cir. 2020). Because the plan imposed the same limitations on out-of-state mental- and physical-health treatments, the plaintiff had not shown that the defendant treated mental health less favorably than physical health. Id. at 777.

More novel theories have met skepticism in the courts of appeals. In I.M. v. Kaiser Foundation Health Plan, Inc., for example, the plaintiff alleged that Kaiser breached its fiduciary duty to him by excluding coverage for residential treatment for eating disorders from its plans and inhibiting physicians from referring him to a residential-treatment facility. 2020 WL 7624925, at *2 (9th Cir. Dec. 22, 2020). The Ninth Circuit disagreed, finding no evidence in the record that Kaiser had erected barriers to residential treatment. Id.

B. Assignments and Anti-Assignment Clauses

The assignment of benefits remains a critical issue in ERISA health plan litigation. Under ERISA § 502(a), only “a participant or beneficiary” may sue an insurer to recover benefits owed to her or to enforce her rights under her plan. 29 U.S.C. § 1132(a)(1)(B). Ordinarily, this would mean that a patient herself would have to sue an insurer under § 502(a). However, courts have deemed it permissible for participants to “assign” their benefits to healthcare providers. See, e.g., Plastic Surgery Ctr. v. Aetna Life Ins. Co., 967 F.3d 218, 228 (3d Cir. 2020). Once a participant has validly assigned her benefits to a healthcare provider, that provider can stand in the shoes of the participant and bring suit against an insurer for non-payment under § 502(a). Id. The appellate courts in 2020 addressed a variety of issues related to the assignment of benefits

1. Scope of the Rights Conveyed

Appellate courts continue to grapple with the scope of the rights conveyed by an assignment. Decisions in 2020 reflect at least two distinct approaches. In American Colleges of Emergency Physicians v. Blue Cross & Blue Shield of Georgia, the Eleventh Circuit took a blanket approach, holding categorically that “the assignment of the right to payment includes the right to seek equitable relief.” 833 F. App’x 235, 240 (11th Cir. 2020). The Sixth and Ninth Circuits, in contrast, held that the scope of an assignment of benefits depends on the specific language used; where an assignment’s language appears to encompass only causes of actions for benefits, then additional potential causes of action under ERISA are not included. See DaVita Inc v. Amy’s Kitchen, Inc., 981 F.3d 664, 678–79 (9th Cir. 2020) (holding that assignment of “any cause of action . . . for purposes of creating an assignment of benefits” did not include the right to seek equitable relief); DaVita, Inc. v. Marietta Mem’l Hosp. Emp. Health Benefit Plan, 978 F.3d 326, 344 (6th Cir. 2020) (concluding that identical language did not include the right to bring breach-of-fiduciary-duty claims under § 1104(a)(1)(B)); see also McKennan v. Meadowvale Dairy Emp. Benefit Plan, 973 F.3d 805, 808–09 (8th Cir. 2020) (holding that an assignment of “any and all causes of action” did not include the right to challenge the rescission of the assignor’s coverage, at least where deceased assignor failed to comply with plan provisions as to third-party representatives). These decisions can be a mixed bag for plans, insurers, and administrators. The Eleventh Circuit’s approach allows providers to bundle benefits claims with equitable claims, while protecting insurers against having to litigate separate claims by patients and providers as to the same underlying treatment. The opposite is true for the Sixth and Ninth Circuit decisions: Where the assignment excludes equitable relief, providers have fewer arrows in their quiver to use against insurers, but insurers could face multiple lawsuits for the same treatment.

2. Waivability of Assignment Issues

Courts sometimes treat the existence and scope of an assignment as a jurisdictional question—going to the existence of Article III standing—that therefore cannot be waived. Cell Sci. Sys. Corp. v. La. Health Serv., 804 F. App’x 260, 264 (5th Cir. 2020) (stating that the existence “of valid and enforceable assignments of benefits” is necessary for Article III standing). In the Sixth Circuit’s DaVita decision, however, the court held that a defendant had waived the argument that one of the plaintiff’s claims fell outside of the scope of the assignment. 978 F.3d at 345. The panel explained that “[t]he question of whether [a patient] has transferred their interest to [a provider] . . . deals not with Article III standing” but with Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 17’s requirement that an action “‘must be prosecuted in the name of the real party in interest.’” Id. The court thus found Article III standing without deciding the dispute about the scope of the assignment. Id. at 341 n.8.

3. Anti-Assignment Clauses

In recent years, ERISA health plans have increasingly elected to include “anti-assignment” clauses. See Plastic Surgery Ctr., 967 F.3d at 228. These clauses bar patients from assigning their benefits to providers, or place certain limits on the scope of what claims can be assigned (or in what circumstances), putting providers back in the position of having to bill patients directly. Id. Should the patient prove unable or unwilling to pay, providers must then either rely on the patient to bring an ERISA suit or sue the patient directly. Id.

Many circuits have addressed these clauses, and they have unanimously determined that the clauses are, in general, permissible and enforceable. See Am. Orthopedic & Sports Med. v. Indep. Blue Cross Blue Shield, 890 F.3d 445, 453 (3d Cir. 2018). Still, appellate decisions in 2020 reflect multiple strategies through which providers have attempted to avoid the effect of anti-assignment clauses, with varying degrees of success:

- In Beverly Oaks Physicians Surgical Center, LLC v. Blue Cross & Blue Shield of Illinois, the Ninth Circuit held that an insurer had waived its right to invoke an anti-assignment clause by failing to raise it during the administrative claim process. 983 F.3d 435, 440–42 (9th Cir. 2020). The court also held that the plaintiff had pleaded sufficient facts to adequately allege that insurer was “equitably estopped from raising” the anti-assignment clause because the insurer had promised the provider that it was eligible to receive payment under plan. Id. at 442–43.

- In Cell Science, by contrast, the Fifth Circuit rejected an argument that an insurer was estopped from invoking anti-assignment clause. 804 F. App’x at 264–66. The court emphasized that there was “no indication from the record that [the insurer] either misrepresented or misled [the provider] with respect to its intention to enforce the anti-assignment clause in its plan.” Id. at 265.

- In King v. Community Insurance Co., the Ninth Circuit held that an assignment fell outside of the scope of the plan’s anti-assignment clause. 829 F. App’x 156, 159–60 (9th Cir. 2020). The plan expressly allowed payments to “providers” and forbade beneficiaries from assigning benefits to “anyone else.” Id. at 159. The Ninth Circuit rejected the insurer’s argument that the phrase “anyone else” meant anyone other than the beneficiary. Id. at 160. The court also held that the anti-assignment clause was unenforceable because it was not properly included in any plan document. Id. at 160–62.

____________________

[1] Congress may also attempt to take action against the rule. The Congressional Review Act provides a procedure for Congress to pass a Joint Resolution of Disapproval within 60 legislative working days that, if signed by the President, deems recent administrative rulemaking to not have had any effect. The DOL’s new rule is still within that 60-day timeframe.

The following Gibson Dunn lawyers assisted in the preparation of this alert: Karl Nelson, Geoffrey Sigler, Katherine Smith, Heather Richardson, Lucas Townsend, Jennafer Tryck, Matthew Rozen, Jennifer Roges, Luke Zaro, Daniel Weiss, Jialin Yang, Christopher Wang, Robert Batista, Zachary Copeland, and Brian McCarty.

Gibson Dunn lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have about these developments. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, or any of the following:

Karl G. Nelson – Dallas (+1 214-698-3203, knelson@gibsondunn.com)

Geoffrey Sigler – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3752, gsigler@gibsondunn.com)

Katherine V.A. Smith – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7107, ksmith@gibsondunn.com)

Heather L. Richardson – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7409,hrichardson@gibsondunn.com)

Lucas C. Townsend – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3731, ltownsend@gibsondunn.com)

Jennafer M. Tryck – Orange County (+1 949-451-4089, jtryck@gibsondunn.com)

Matthew S. Rozen – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3596, mrozen@gibsondunn.com)

© 2021 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.

Please join the authors of An Employer Playbook for the COVID “Vaccine Wars”: Strategies and Considerations for Workplace Vaccination Policies (Feb. 2021) for the latest information and trends relating to workplace vaccination policies and programs. Topics will include whether to mandate COVID-19 vaccinations or merely encourage them; pros and cons of both approaches; pertinent EEOC, OSHA, and CDC guidance; ways to minimize obstacles to employee vaccination including whether to provide vaccinations on site; issues relating to incentives programs; how to handle employees who cannot be, or claim they cannot be, vaccinated; how to build buy-in and plan for conflict resolution; workplace mask and social distancing requirements for vaccinated workers; how the National Labor Relations Act may be implicated; and whether there is a role for waivers or risk disclosures to reduce potential liability.

View Slides (PDF)

PANELISTS:

Jessica Brown is a partner in the Denver office of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher and a member of the firm’s Labor and Employment and White Collar Defense and Investigations Practice Groups. Ms. Brown advises corporate clients regarding COVID-19 liability risks, workplace vaccination policies, Colorado Equal Pay for Equal Work Act Transparency Rules, anti-harassment, whistleblower complaints, reductions in force, mandatory arbitration programs, return-to-work protocols, and matters that intersect with intellectual property law, such as noncompete agreements and trade secrecy programs. She has assisted clients to conduct audits of their pay practices for purposes of compliance with state and federal equal pay and wage and hour laws. In addition, Ms. Brown has defended nationwide and state-wide class action and individual lawsuits alleging, for example, gender discrimination under Title VII, failure to permit facility access under the Americans with Disabilities Act, and failure to compensate workers properly under the Fair Labor Standards Act. She has been ranked by Chambers USA as a leading Labor and Employment lawyer in Colorado for 16 consecutive years and is currently ranked in Band 1. She also is the current President of the Colorado Bar Association.

Lauren Elliot is a partner in the New York office of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher and a member of the firm’s Life Sciences, Product Liability, and Labor and Employment Practice Groups. Ms. Elliot has defended pharmaceutical and biotech companies in cases involving a broad spectrum of well-known life sciences products including vaccines. She served as national counsel to Wyeth (now Pfizer) in close to 400 product liability actions in which plaintiffs alleged that childhood vaccines cause autism spectrum disorders. She also often assesses product liability risks in connection with planned corporate acquisitions on behalf of acquiring companies. Legal Media Group has named Ms. Elliot to its Expert Guides Guide to the World’s Leading Women in Business Law for Product Liability three times and she has served two terms as a member of the Product Liability Committee for the Association of the Bar of the City of New York. Ms. Elliot also has spent close to a decade defending labor and employment claims in class actions and individual lawsuits alleging violations of state labor laws and the Fair Labor Standards Act.

MCLE CREDIT INFORMATION:

This program has been approved for credit in accordance with the requirements of the New York State Continuing Legal Education Board for a maximum of 1.0 credit hour, of which 1.0 credit hour may be applied toward the areas of professional practice requirement. This course is approved for transitional/non-transitional credit.

Attorneys seeking New York credit must obtain an Affirmation Form prior to watching the archived version of this webcast. Please contact CLE@gibsondunn.com to request the MCLE form.

Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP certifies that this activity has been approved for MCLE credit by the State Bar of California in the amount of 1.0 hour.

California attorneys may claim “self-study” credit for viewing the archived version of this webcast. No certificate of attendance is required for California “self-study” credit.

Palo Alto partner Mark Lyon is the co-author of “ITC Section 337 Patent Investigations: Overview,” [PDF] published by Thomson Reuters Practical Law in February 2021.

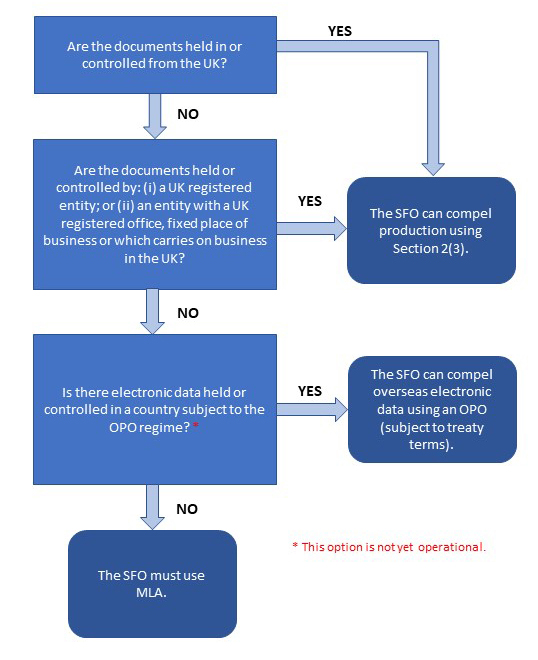

On February 5, 2021, in a unanimous decision, the UK Supreme Court ruled that the SFO’s so-called “Section 2” power, found in section 2(3) of the Criminal Justice Act 1987 (“CJA”), cannot be used to compel a foreign company that has no UK registered office or fixed place of business and which has never carried on business in the UK, to produce documents it holds outside the UK. In so ruling, the Supreme Court overruled a 2018 Divisional Court decision that held that the SFO could use its power in this way, provided that there was a “sufficient connection” between the foreign company and the UK.

In this alert we provide an overview of the Supreme Court’s decision and offer our observations on the implications of the judgment for the SFO and foreign companies under investigation. We conclude with an illustrative summary of the different methods available to the SFO to obtain documents following the Supreme Court’s decision.

The decision will come as a setback for the SFO, which will now have to rely on the often cumbersome and slow Mutual Legal Assistance (“MLA”) route to obtain documents in these circumstances. The loss is compounded as the Supreme Court decision comes shortly after the UK lost access to certain investigatory powers it enjoyed by virtue of the UK’s (now prior) Membership of the European Union (“EU”), such as the European Investigation Order (“EIO”), which enabled the SFO to quickly obtain evidence, including documents, located in the EU.

Waiting to become operational is the agreement signed between the UK and U.S. in October 2019 to implement the Crime (Overseas Production Orders) Act 2019. Once in effect, the SFO, as well as other UK investigations agencies, including the Financial Conduct Authority, will be able to obtain certain “electronic data” located or controlled from the U.S. via an Overseas Production Order (“OPO”). OPOs will be issued by an English court, and the recipient must provide the data, ordinarily within seven days, to the agency named in the OPO. Although OPOs will enable authorities to obtain evidence faster, they do not apply to hard copy and certain other material, such that MLA requests will remain a necessary route in many instances. Whilst it is the intention of the UK Government to enter into agreements with other countries and blocs such as the EU, the UK/U.S. agreement is the only such agreement currently in place.

The Supreme Court decision will obviously be disappointing for the SFO. However, it will support an argument that the Government needs to consider the scope of the SFO’s powers, to ensure it has the tools necessary to investigate sophisticated, organised criminal wrongdoing in an increasingly globalised world.

Section 2 Notices

Section 2(3) of the CJA provides that “The Director [of the SFO] may by notice in writing require the person under investigation or any other person to produce … any specified documents which appear to the Director [of the SFO] to relate to any matter relevant to the investigation or any documents of a specified description which appear to him so to relate”.

It is a criminal offence to fail to comply with section 2(3) of the CJA without a “reasonable excuse”.

Section 2 notices are attractive to the SFO because the SFO alone may determine whether to compel a recipient to produce documents, and may serve the notice directly upon the recipient and enforce non-compliance. It requires no court or other third-party intervention, thereby providing a rapid, effective and largely self-regulated method of compelling the production of documents.

Background

KBR, Inc. is a U.S. incorporated engineering and construction company and the parent company of the KBR Group. In 2017, KBR, Inc.’s UK subsidiary, Kellogg Brown & Root Ltd (“KBR UK”), was under investigation by the SFO for suspected bribery. During this investigation, a representative of KBR, Inc. attended a meeting with the SFO in the UK to discuss its investigation into KBR UK. During that meeting, the SFO issued a notice to KBR, Inc. under section 2(3) of the CJA compelling the production of documents held outside of the UK (the “July Section 2 Notice”). KBR, Inc. did not have a fixed place of business in the UK and had never carried on business in the UK.

KBR, Inc. sought permission to apply for judicial review of the decision and to quash the July Section 2 Notice in the Divisional Court, on three grounds:

- The July Section 2 Notice was ultra vires the CJA as it requested material held outside of the UK from a company incorporated outside of the UK;

- The Director of the SFO made an error of law in issuing the July Section 2 Notice instead of using its power to seek MLA from the U.S. authorities under the UK’s 1994 bilateral U.S. MLA Treaty; and

- The July Section 2 Notice was not properly served on KBR, Inc. under the CJA.

In September 2018, the Divisional Court held that the SFO could require a foreign company to produce documents held overseas pursuant to section 2(3) of the CJA where there is a “sufficient connection between the company and the jurisdiction”. The Court held that there was a sufficient connection between KBR, Inc. and the UK in this case, as payments made by KBR UK required the express approval of KBR, Inc., were paid by KBR, Inc. through its U.S.-based treasury function, and for a period of time KBR, Inc.’s compliance function was required to approve the payments. In addition, an officer of KBR, Inc. was based in the KBR Group’s UK office. The fact that KBR, Inc. was the parent company of KBR UK was not sufficient by itself to establish a “sufficient connection”.

The Supreme Court Case

KBR, Inc. was granted leave to appeal and made the following arguments in the Supreme Court:

- Presumption against Extra-Territorial Effect and Principle of International Comity: there is a presumption under English law that a statute has no extra-territorial effect, as this would constitute a breach of international comity – namely, the principle of recognising, upholding and respecting other jurisdictions’ legislative and judicial acts.

- Wording of the CJA: the terms of the CJA do not suggest a Parliamentary intention to confer extraterritorial powers upon the SFO.

- Role of Parliament vs the Court and the “Sufficient Connection” test: the decision regarding the extraterritorial application of the CJA is a matter for Parliament rather than the Court. As such, the decision to introduce a “sufficient connection” test would be a question to be answered by legislation, rather than one of judicial interpretation.

Presumption against Extra-Territorial Effect and Principle of International Comity

The Supreme Court held that the “starting point” for the consideration of the scope of section 2(3) is the presumption in English law that “legislation is generally not intended to have extra-territorial effect”. This presumption, according to the Supreme Court, is rooted in both the requirements of international law and the concept of comity, which is founded on mutual respect between states.

The Supreme Court emphasised that whilst the principle of comity was not a “rule of international law” as such, the “lack of precisely defined rules in international law as to the limits of legislative jurisdiction makes resort to the principle of comity as a basis of the presumption applied by courts in this jurisdiction all the more important”.

Lord Lloyd-Jones, writing for the Supreme Court, acknowledged the “legitimate interest of States in legislating in respect of the conduct of their nationals abroad”, however, he held that this case did not concern the conduct of a UK national or UK registered company abroad. If the addressee of the July Section 2 Notice had been a UK registered company, section 2(3) would have authorised the service of a notice to produce documents held abroad by that company.

Since the addressee of the July Section 2 Notice, KBR, Inc., had never carried on business in the UK or had a registered office or any other presence in the UK, the Supreme Court held that the presumption against extra-territorial effect clearly did apply to this case. The question for the Supreme Court was, therefore, whether Parliament intended section 2(3) to displace the presumption to give the SFO the power to compel a foreign registered company with no registered office or fixed place of business in the UK and which did not conduct business in the UK to produce documents it holds outside the UK.

Wording of the CJA

With respect to the question of whether the presumption against extra-territorial effect had been rebutted by the language of the CJA, the Supreme Court held that the “answer will depend on the wording, purpose and context of the legislation considered in the light of relevant principles of interpretation and principles of international law and comity.”

The Supreme Court noted that “when legislation is intended to have extra-territorial effect Parliament frequently makes express provision to that effect” and, unlike other statutory provisions, section 2(3) “includes no such express provision”. Moreover, the Supreme Court found that the other provisions of the CJA do not provide “any clear indication, either for or against the extra-territorial effect.”

Role of Parliament vs the Court and the “Sufficient Connection” Test

KBR, Inc. submitted that: