New York Updates Law on Recognition of Foreign Country Money Judgments to Bring in Line with Other U.S. Jurisdictions

Client Alert | June 22, 2021

On June 11, 2021, New York Governor Andrew M. Cuomo signed into law a Uniform Foreign Country Money Judgments Act (the “2021 Recognition Act”), amending New York’s Uniform Foreign Country Money-Judgments Recognition Act of 1970 (the “1970 Recognition Act”).[1] The bill was designed to update and bring New York’s existing legislation in line with the revisions proposed by the Uniform Law Commission in 2005.[2] With this enactment, New York follows a growing number of U.S. states that have modernized their recognition acts over the last decade.

As detailed herein, the 2021 Recognition Act both clarifies the procedural mechanisms and substantive arguments that litigants can invoke in a proceeding to recognize foreign country money judgments (“foreign judgments”), while also significantly expanding the defenses to recognition and enforcement of foreign judgments available to defendants in New York. In particular, the substantive changes seek to ensure that the New York courts only recognize foreign judgments that have been procured through a fair and impartial process.

I. Overview of Recognition of Foreign Judgments in the United States

There is no federal law governing recognition of foreign judgments in the United States. However, the rules are broadly similar across all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia, providing for recognition of foreign judgments that are final, conclusive, and enforceable where rendered. Over the last 60 years, a majority of U.S. states have codified their rules on recognition, following initially the Uniform Foreign Money Judgments Recognition Act of 1962 (the “1962 Uniform Act”) or now increasingly the Uniform Foreign-Country Money Judgments Recognition Act of 2005 (the “2005 Uniform Act”).

The 1962 Uniform Act was designed to increase the predictability and stability in this area of the law, facilitate international commercial transactions, and encourage foreign courts to recognize U.S. judgments.[3] Notably, the 1962 Uniform Act did not prescribe any enforcement procedure, providing instead that a foreign judgment, once domesticated, is enforceable in the same manner as the judgment of a court of a sister U.S. state, which is entitled to full faith and credit. That is still the prevailing rule today.

The 1962 Uniform Act defined certain threshold requirements for recognition and outlined certain mandatory and discretionary grounds for non-recognition. For example, the recognizing U.S. court was directed to consider, inter alia, whether the judgment was rendered under a judicial system that provides for impartial tribunals and procedures compatible with due process; whether the foreign court had personal and subject matter jurisdiction; whether the defendant received sufficient notice of the proceedings to mount a defense; whether the judgment was obtained by fraud; and whether the cause of action or claim for relief on which the judgment is based is repugnant to the public policy of the recognizing state.

In 2005, the Uniform Law Commission issued the 2005 Uniform Act.[4] Its purpose was to update and clarify the 1962 Uniform Act and “to correct problems created by the interpretation of the provisions of that Act by the courts over the years since its promulgation” while maintaining “the basic rules or approach.”[5] In particular, the 2005 Uniform Act created new discretionary bases for non-recognition, updated and clarified the definitions section, clarified the procedure for seeking (and resisting) recognition of a foreign judgment, expressly allocated the burden of proof, and established a statute of limitations for recognition actions.[6]

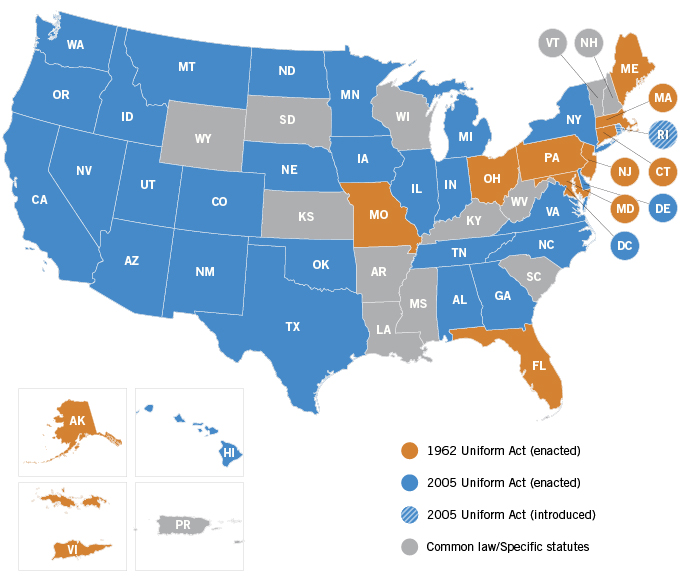

Since 2007, a growing number of U.S. states have enacted the modernized 2005 Uniform Act (see map below). As of June 2021, 27 states and the District of Columbia have adopted the 2005 Uniform Act, while one state has introduced this legislation.[7] Another 11 states and the U.S. Virgin Islands currently still apply the 1962 Uniform Act.[8] In the remaining 12 states, the recognition of judgments remains primarily a matter of common law or unique statutory provisions.

Law on Recognition of Foreign Judgments in the United States

Data Source: Uniform Law Commission

II. Overview of Recognition of Foreign Judgments in New York

New York adopted the 1962 Uniform Act as CPLR Article 53 in 1970. Traditionally in New York, once the judgment creditor had made the initial showing that the foreign judgment falls within the scope of New York’s recognition statute, the judgment debtor had to establish a basis for non-recognition if it wished to avoid recognition. As in most U.S. states, New York’s 1970 Recognition Act set out both mandatory grounds for non-recognition—under which the court is prohibited from granting recognition—and discretionary bases on which a court may decline recognition.

With the enactment of the 2021 Recognition Act, New York largely leaves intact the legal framework established by the 1970 Recognition Act while adopting the key updates from the 2005 Uniform Law:

- New Proceeding-Specific Discretionary Criteria. There are two new discretionary criteria for non-recognition, providing that a court may decline recognition where (i) “the judgment was rendered in circumstances that raise substantial doubt about the integrity of the rendering courts with respect to the judgment,”[9] or (ii) “the specific proceeding in the foreign court leading to the judgment was not compatible with the requirement of due process of law.”[10] These two new grounds are significant because they are proceeding-specific—i.e., the judgment debtor can challenge recognition based on a lack of due process or impartial tribunals in the specific proceedings that gave rise to the foreign judgment, regardless of the fairness or procedural safeguards available in the foreign country’s judicial system overall. Under the 1970 Recognition Act, by contrast, complaints about the particular proceeding against the judgment debtor were generally insufficient. To avoid recognition, by statute, a judgment debtor had to establish that the foreign country’s judicial system as a whole lacked impartial tribunals or due process—a high bar in state courts that may be loath to condemn the entire judicial system of a foreign country. Nonetheless, as the Uniform Law Commission noted in its letter of support of the bill, a number of U.S. courts applying the 1962 Uniform Act were either ignoring the “system” language in the governing statute or else “stretching” that language to import proceeding-specific considerations.[11] Such interpretative issues were sufficiently significant to warrant the Uniform Law Commission’s revision of the 1962 Uniform Act.[12]

- Updated Grounds for Non-Recognition. The 2021 Recognition Act also expands the mandatory and discretionary grounds for non-recognition available to a judgment debtor seeking to resist recognition. For example, whereas a lack of subject matter jurisdiction was a discretionary basis for non-recognition under the 1970 Recognition Act, it is mandatory under the 2021 Recognition Act, meaning that a New York court must refuse recognition where the foreign court lacked subject matter jurisdiction over the underlying dispute.[13] Further, the 2021 Recognition Act expands the scope of the (discretionary) public policy non-recognition ground, providing that a court may consider either whether the foreign judgment or the cause of action on which the judgment is based is “repugnant to the public policy of New York or of the United States.”[14] Under the 1970 Recognition Act, this ground was limited to cases where the underlying cause of action—and not the foreign judgment itself—was repugnant to New York’s public policy.

- Burden of Proof. The 2021 Recognition Act clarifies and makes explicit that the party seeking recognition of a foreign judgment bears the burden of establishing that the judgment is subject to the act,[15] while the party resisting recognition has the burden of establishing that a specific ground for non-recognition applies.[16]

- Procedure. The Act clarifies that when recognition is sought as an original matter, the party seeking recognition must file an action on the judgment (or a motion for summary judgment in lieu of complaint) to obtain recognition,[17] but when recognition is sought in a pending action, it may be filed as a counter-claim, cross-claim, or affirmative defense.[18]

- Statute of Limitations. The 2021 Recognition Act establishes a limitations period, providing that a New York court may only enforce a foreign judgment that is still “effective in the foreign country.”[19] If there is no limitation on enforcement in the country of origin, recognition must be sought within 20 years of the date that the judgment became effective in the foreign country.[20]

As with the 1970 Recognition Act, the 2021 Recognition Act applies to any foreign judgment that is “final, conclusive and enforceable” where rendered.[21] It does not apply to a foreign judgment for taxes, a fine or penalty, and it further clarifies that it does not apply to a “judgment for divorce, support or maintenance, or other judgment rendered in connection with domestic relations.”[22] Within those defined limits, the 2021 Recognition Act will apply to all recognition actions commenced on or after the effective date of the act (i.e., June 11, 2021)[23] even if the relevant transactions or proceedings in the foreign country took place before then.

III. Implications of New York’s 2021 Recognition Act

As noted above, the 2021 Recognition Act provides certain definitional, procedural, and substantive changes that will impact judgment creditors and debtors litigating recognition in New York courts.

Many of these revisions will benefit both parties by providing greater clarity and precision about the procedural mechanisms and substantive arguments they can plausibly invoke in a recognition proceeding. Some of the revisions, like the statute of limitations, reduce the incentive to forum-shop where foreign law provides for a shorter effectiveness period than New York law.

The most immediate effect of the 2021 Recognition Act will be felt on the scope and complexity of litigation. As the Sponsor Memo noted, the 2021 Recognition Act “revises the grounds for denying recognition of foreign country money judgements to better reflect the even more varied forms of judicial process on the modern global stage.”[24] Notably, the 2021 Recognition Act will permit judgment debtors to challenge foreign judgments based on proceeding-specific concerns so as to ensure the foreign judgment being recognized has adhered to fundamental principles of due process that the New York courts have a vested interest in protecting. This was previously more difficult to do where only systemic (as opposed to proceeding-specific) due process considerations could be considered in denying recognition.[25] The inclusion of proceeding-specific grounds, which will inevitably expand the range of arguments a judgment debtor can now raise, will likely increase the number of foreign judgments denied recognition in New York courts.

These additional defenses will require greater sophistication by both judgment creditors and debtors in recognition actions in terms of what kinds of foreign legal and expert evidence to marshal. At the same time, these defenses give the New York courts additional bases to ensure that they only recognize judgments that result from a fair and impartial proceeding.

______________________________

[1] The bill was signed into law (Chapter 127) on June 11, 2021. See Senate Bill S523A, N.Y. State Senate (last visited June 21, 2021), https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2021/s523.

[2] S.B. S523A (N.Y. 2021) (“An act to amend [New York’s] civil practice law and rules, in relation to revising and clarifying the uniform foreign country money-judgments recognition act.”).

[3] See Uniform Law Comm’n, Uniform Foreign Money-Judgments Recognition Act (with Prefatory Note and Comments) (1962).

[4] See Uniform Law Comm’n, Uniform Foreign-Country Money Judgments Recognition Act (with Prefatory Note and Comments) (2005).

[5] Id., Prefatory Note, at 1.

[7] Foreign-Country Money Judgments Recognition Act 2005, Uniform Law Comm’n (last visited June 22, 2021), https://www.uniformlaws.org/committees/community-home?CommunityKey=ae280c30-094a-4d8f-b722-8dcd614a8f3e.

[8] Foreign-Country Money Judgments Recognition Act 1962, Uniform Law Comm’n (last visited June 22, 2021), https://www.uniformlaws.org/committees/community-home?CommunityKey=9c11b007-83b2-4bf2-a08e-74f642c840bc.

[9] N.Y. CPLR § 5304(a)(7) (McKinney 2021).

[11] See Letter from the Uniform Law Commission to the Chairmen of the New York Assembly Judiciary Committee, dated March 11, 2021, at 2.

[13] N.Y. CPLR § 5304(a)(3) (McKinney 2021).

[24] Sponsor’s Mem., S.B. S523A (N.Y. 2021), https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2021/s523.

[25] See, e.g., Shanghai Yongrun Inv. Management Co., Ltd. v. Kashi Galaxy Venture Capital Co., Ltd., No. 156328/2020, 2021 WL 1716424 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. Apr. 30, 2021); Chevron Corp. v. Donziger, 974 F. Supp. 2d 362 (S.D.N.Y. 2014), aff’d, 833 F.3d 74 (2d Cir. 2016); Bridgeway Corp. v. Citibank, 45 F. Supp. 2d 276 (S.D.N.Y. 1999), aff’d, 201 F.3d 134 (2d Cir. 2000). See also Osorio v. Dole Food Co., 665 F. Supp. 2d 1307 (S.D. Fla. 2009), aff’d sub nom. Osorio v. Dow Chem. Co., 635 F.3d 1277 (11th Cir. 2011); Bank Melli Iran v. Pahlavi, 58 F.3d 1406 (9th Cir. 1995).

The following Gibson Dunn lawyers prepared this client alert: Rahim Moloo, Lindsey D. Schmidt, Maria L. Banda, and Peter M. Wade.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these issues. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, any member of the firm’s International Arbitration, Judgment and Arbitral Award Enforcement or Transnational Litigation practice groups, or the following:

Rahim Moloo – New York (+1 212-351-2413, rmoloo@gibsondunn.com)

Lindsey D. Schmidt – New York (+1 212-351-5395, lschmidt@gibsondunn.com)

Anne M. Champion – New York (+1 212-351-5361, achampion@gibsondunn.com)

Maria L. Banda – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3678, mbanda@gibsondunn.com)

Please also feel free to contact the following practice group leaders:

International Arbitration Group:

Cyrus Benson – London (+44 (0) 20 7071 4239, cbenson@gibsondunn.com)

Penny Madden QC – London (+44 (0) 20 7071 4226, pmadden@gibsondunn.com)

Judgment and Arbitral Award Enforcement Group:

Matthew D. McGill – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3680, mmcgill@gibsondunn.com)

Robert L. Weigel – New York (+1 212-351-3845, rweigel@gibsondunn.com)

Transnational Litigation Group:

Susy Bullock – London (+44 (0) 20 7071 4283, sbullock@gibsondunn.com)

Perlette Michèle Jura – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7121, pjura@gibsondunn.com)

Andrea E. Neuman – New York (+1 212-351-3883, aneuman@gibsondunn.com)

William E. Thomson – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7891, wthomson@gibsondunn.com)

© 2021 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.