The UK’s New National Security Regime

Client Alert | November 18, 2020

The UK Government (the “Government”) has announced plans to upgrade and widen significantly its intervention powers on grounds of national security.

The proposal is for a ‘hybrid regime’ whereby notification and approval would be mandatory prior to completing certain deals (described further below) in specified areas of the economy deemed particularly sensitive. Here, clearance would be required to be obtained prior to closing. Further, any failure to notify would result in a transaction that is ‘legally void’,[1] sanctions would be applicable and the Government would have a potentially indefinite period to ‘call-in’ the deal (a period which would be reduced to 6 months if the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (the “SoS”) becomes aware of the deal). Notification will otherwise be voluntary. However, the Government will be able to ‘call-in’ such transactions for a period of up to 5 years (again, this period would be reduced to a period of 6 months if the SoS becomes aware of the deal). Once a transaction has been called in and assessed, where necessary and proportionate, the Government will have the power to impose a range of remedies to address any national security concerns.

The proposed regime represents a significant expansion and extension of the current rules, including a significant broadening of the nature of transactions that can be reviewed (e.g. removing safe harbours based on turnover and market share and including acquisitions of certain qualifying assets, including acquisitions of land, physical assets and IP).[2] It is expected to result in significantly higher levels of scrutiny going forward. Indeed, the Government estimates that around 1,000-1,830 notifications could be received a year with 70-95 cases called in for a full national security assessment under the new regime. However, practitioners are of the view that the bill and the proposed secondary legislation detailing the sensitive sectors (as currently drafted) could result in many more notifications.

The Government, however, continues to emphasise the importance of foreign direct investment projects in the UK and the need to ensure that the UK remains an attractive place to invest. Indeed, the Government’s commitment to staying open to foreign investment is reflected in the Prime Minister’s recent announcement of the creation of the Office for Investment. This is a Government unit aimed at driving foreign investment into the UK (tasked to land high value investment opportunities and to resolve potential barriers to landing ‘top tier’ investments).[3] The Business Secretary Alok Sharma also specifically stated on the bills introduction to Parliament that: “The UK remains one of the most attractive investment destinations in the world and we want to keep it that way […] This Bill will mean that we can continue to welcome job-creating investment to our shores, while shutting out those who could threaten the safety of the British people.” The emphasis of the new proposals is thus on encouraging engagement, so that the Government becomes aware of a greater number of deals and can check that they do not pose risks to the UK’s national security. It has been emphasised that a targeted and proportionate approach to enforcement will be adopted, and that most transactions will be cleared without intervention (albeit that conditions will be required to be imposed in some cases and reviews will impact transaction timetables). The regime also introduces a clearer and more defined process for national security reviews than is currently the case, which should assist with transaction planning.[4]

The proposal is set out in the ‘National Security and Investment Bill’ (the “NSIB”) which will be subject to Parliamentary scrutiny before being passed into law.[5] However, in the interim, investors will need to be aware that the proposed legislation will give the Government the retroactive power from commencement to open an investigation into a transaction that has been completed following the introduction of the NSIB to Parliament (i.e. on or from 12 November 2020) but prior to the commencement of the Act. In such circumstances, the Government will have 6 months from the commencement day to intervene, if the SoS previously became aware of the transaction. Otherwise, the Government will be able to ‘call-in’ the deal up to 5 year’s following the commencement date, unless the SoS becomes aware of the transaction earlier in which case this period is reduced to 6 months from when the SoS becomes aware of the deal.[6]

Key aspects of the proposed new regime are detailed below. At the end of this briefing, we also include some practical tips for transacting parties.

Mandatory vs voluntary notification

- The NSIB provides for the mandatory pre-closing notification of certain acquisitions of voting rights or shares (see “Trigger events/qualifying transactions”, below) in entities active in specified sectors and involved in activities considered higher risk.

- The Government is currently consulting on the proposed sectors, and which parts of each sector, should fall within the scope of the mandatory regime, which will later be defined through secondary legislation.[7]

- As currently proposed, the following 17 sectors would be affected: advanced materials; advanced robotics; artificial intelligence; civil nuclear; communications; computing hardware; critical suppliers to government; critical suppliers to the emergency services; cryptographic authentication; data infrastructure; defence; energy; engineering biology; military or dual-use technologies; quantum technologies; satellite and space technologies and transport.

- The NSIB will provide the Government with powers to amend the types of transactions in scope of the mandatory notification regime – which will include powers to amend the sectors subject to mandatory notification as well as the nature of transactions giving rise to mandatory notification requirements (discussed further below) and exempting certain types of acquisition. It is not clear as yet the circumstances in which dispensations will be granted – it is expected that these will be developed over time (if, for example, the Government finds that certain types of transactions caught by the mandatory regime routinely do not require remedies and thus do not present sufficient security concerns – this may, for example, be based on the characteristics of the investors involved or the type of transaction).

- The fact that sectors of the economy giving rise to mandatory notification requirements will be defined in secondary legislation gives ministers significant discretion to alter the regime without full parliamentary scrutiny. Indeed, it has been specifically called out by the Government that such sectors are ‘highly likely to change over time’, in response to changing risks.

- As mentioned above, if parties fail to notify a trigger event that is subject to mandatory notification, the Government can call it in whenever it is discovered – albeit that the Government is under a 6 month deadline from which the SoS becomes aware of the transaction to call-in the deal. This does not apply to events which take place prior to the commencement of the NSIB, as no mandatory notification requirement will apply until that point.

- In addition to the mandatory regime, parties will be able to voluntary notify deals. The NSIB will permit ministers to ‘call-in’ transactions (not subject to the mandatory regime) up to 6 months after the SoS becomes aware of the transaction (including potentially, through coverage of the deal in a national news publication[8]) provided that this is done within 5 years and there is a ‘reasonable suspicion’ that it may give rise to a national security risk (a transaction cannot be ‘called-in’ for any broader economic interest issues such as employment).[9]

Trigger events / qualifying transactions

- The NSIB envisages that a number of transactions will give rise to so called ‘trigger events’, which will provide an opportunity for the Government to review a transaction. These include acquisitions of:

- More than 25%, 50% and 75% of the voting rights or shares of an entity (with increases in shareholding passing over these thresholds notifiable);

- Voting rights that ‘enable or prevent the passage of any class of resolution governing the affairs of the entity’;

- ‘Material influence’ over an entity’s policy; and

The concept of ‘material influence’ is an existing concept under the UK’s competition regime. It can be based on an acquirer’s shareholding, its board representation or other factors. For shareholdings, the CMA may examine shareholdings of 15% or more to determine whether an acquirer will have material influence. Even a shareholding of less than 15% might attract scrutiny in exceptional cases (where other factors indicate that the ability to exercise material influence over policy are present).

-

- A right or interest in, or in relation to, a qualifying asset providing the ability to:

- use the asset, or use it to a greater extent than prior to the acquisition; or

- direct or control how the asset is used, or direct or control how the asset is used to a greater extent than prior to the acquisition.

- A right or interest in, or in relation to, a qualifying asset providing the ability to:

Assets in scope of the regime will be defined in the NSIB – as currently proposed, this includes land, tangible moveable property,[10] and ideas, information, or techniques with industrial, commercial or other economic value (including, for example, trade secrets, databases, algorithms, formulae, non-physical designs and models, plans, drawings and specifications, software, source code and IP).

- The mandatory notification requirement would apply to the trigger events specified in (i) and (ii), above, plus an acquisition of 15% or more of the voting rights or shares of an entity. Whilst the latter is not a ‘trigger event’ for notification per se, it is designed to bring transactions to the attention of the SoS so that they can decide whether trigger event (iii) has occurred.

- So, in summary, the NSIB envisages that it could apply to shareholding as low as 10-15% and will cover deals involving a broad range of asset types.

- Moreover there are currently no safe harbour provisions (e.g. in terms of UK market share or turnover requirements) pursuant to which the Government would not have jurisdiction to review the transaction. However, transactions will require a UK nexus (as discussed below).

UK nexus

- The new regime will apply to investors from any country, including where acquirers and sellers do not have a direct link to the UK. To intervene in such circumstances, the SoS must be satisfied that:

- in respect of a target entity formed or recognised under laws outside of the UK, the entity carries on activities in the UK or supplies goods or services to persons in the UK; and

- in respect of a target asset situated outside of the UK or intellectual property, the asset must be used in connection with activities carried on in the UK or the supply of goods or services to persons in the UK.[11]

- This means, for example, that a business in one country acquiring a business in another country may fall within the regime if the latter carries out activities or provides services or goods in the UK with national security implications. This is also the case in relation to assets which may be used in connection with goods or services provided to UK persons e.g. deep-sea cables located outside of the UK’s geographical borders delivering energy to the UK or intellectual property located outside of the UK but key to the provision of critical functions in the UK.

- The Government intends to legislate for a tighter nexus test in the case of mandatory transactions, but this would not preclude the Government from using the call-in power to intervene in transactions with less direct links to the UK.

Likelihood of intervening – voluntary notifications

- The Government intends to publish a Statutory Statement of Policy Intent (which will be reviewed at least every 5 years), setting out when the Government expects to use its call-in power. This document will assist with the assessment of when a voluntary notification is more likely to be called in – however, a large amount of discretion will still be exercisable when deciding whether or not to intervene.

- The current draft Statutory Statement of Policy Intent, published alongside the NSIB,[12] states that the SoS will consider three factors when deciding whether or not to exercise its powers, namely:

- Acquirer risk (i.e. the extent to which the acquirer raises national security concerns);

- Target risk (i.e. the nature of the target and whether it is active in an area of the economy where the Government considers risks more likely to arise e.g. within the headline sectors where mandatory notification is required); and

- Trigger event risk (i.e. the type and level of control being acquired and how this could be used in practice to undermine national security).

Examples of trigger event risk include – but are not limited to – the potential for: (i) disruptive or destructive actions: the ability to corrupt processes or systems; (ii) espionage: the ability to have unauthorised access to sensitive information; (iii) inappropriate leverage: the ability to exploit an investment to influence the UK; and (iv) gaining control of a crucial supply chain or obtaining access to sensitive sites, with the potential to exploit them. The risk will be assessed according to the practical ability of a party to use an acquisition to undermine national security.

- The type of asset acquisitions where Government may encourage a notification will also be set out in the Statutory Statement of Policy Intent. The current draft suggests that the SoS will intervene ‘very rarely’ in asset transactions. However, where assets are integral or closely related to activities deemed particularly sensitive (e.g. in sectors subject to the mandatory regime) or, in the case of land, where it is or is proximate to a sensitive site or location (e.g. critical national infrastructure sites or government buildings), acquisitions are more likely to be called in. The SoS may also take into account the intended use of the land.

Procedure

- Unsurprisingly, decisions will be taken by the SoS (currently responsible for making decisions in most national security cases under the current regime) rather than an independent body (as with competition cases).

- The SoS will be supported by the Investment Security Unit, which will sit within the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy and provide a single point of contact for businesses wishing to understand the NSIB and notify the Government about transactions. The unit will also coordinate cross-government activity to identify, assess and respond to national security risks arising through market activity.

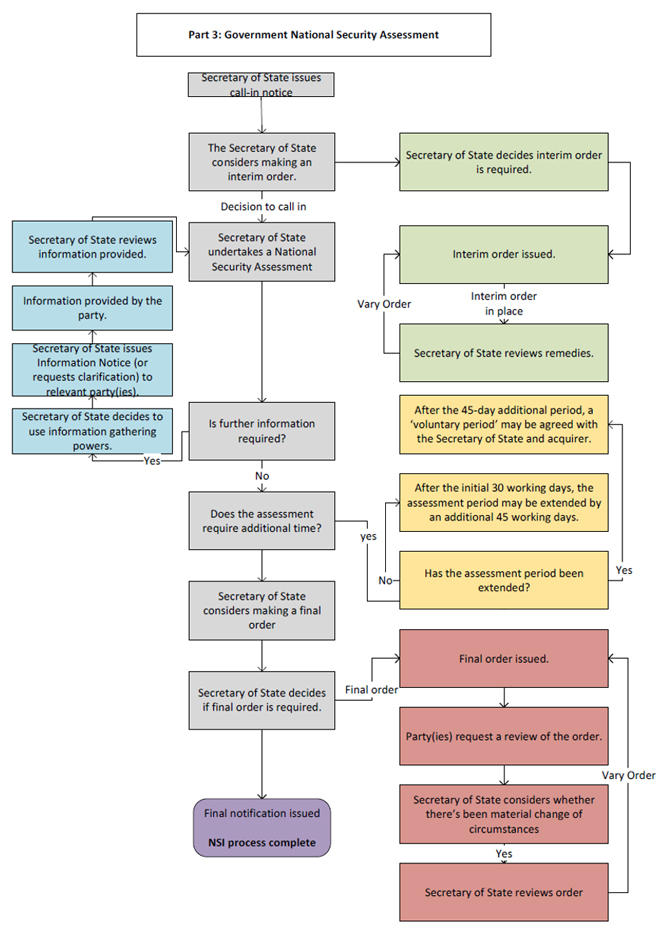

- Where a notification has been made (whether mandatory or voluntary) the SoS will have an initial 30 working day ‘screening period’ to issue a ‘call-in’ notice. Where a transaction is ‘called in’ (including for non-notified transactions), the Government will then have a 30 working day preliminary assessment period. This period would be extendable by a further 45 working days where the initial assessment period is not sufficient to fully assess the risks involved. Further extensions, beyond 75 working days, may be agreed between the acquirer and the SoS for problematic transactions. The SoS will also have the ability to ‘stop the clock’ through formally issuing an information notice or attendance notice during the process, until such a notice is complied with.

- At the end of its review, the SoS will either clear the transaction or must decide to issue a final order, if satisfied that the transaction poses, or would pose, a national security risk (on the balance of probabilities). Such orders may impose conditions or may rule that the transaction should be blocked or unwound.

- The SoS will have a range of remedies available to address national security risks associated with transactions, both while assessments take place and after their completion.

- It is not intended, as under the current regime, that parties will be able to voluntarily offer up undertakings to address concerns (however, parties will be encouraged to maintain a dialogue with the Government throughout the assessment process and it is anticipated that these conversations will assist in designing remedies; further, there will be opportunity for the parties to make representations on remedies during the assessment process). All conditions to approval will be formalised in an order and enforceable through sanctions.

- During an investigation, the Government may also issue interim orders to prevent parties from completing a transaction or, where deals have closed, integrating their operations. Such orders may have extra-territorial effects.

- Legal challenges to decisions will be subject to the standard judicial review process (subject, for certain decisions, to a shortened time limit – 28 days as opposed to the usual three-month period, although the court can give permission to bring the claim after the expiry of the 28 days). The key implication being that it will not be possible to open up decisions for a full appeal on the merits (except in respect of decisions relating to civil penalties, for which a full merits appeal will be available). Close material procedures (“CMPs”) will be utilised to ensure that sensitive materials are not improperly disclosed.[13]

Sanctions

- The proposed legislation creates a number of sanctions, civil and criminal, that will apply in the event of non-compliance. For instance, criminal and civil sanctions are applicable where an acquirer progresses to completion an acquisition subject to the mandatory notification regime, without first obtaining clearance from the SoS. The recommendation would thus be to engage early with the Government and complete the notification process in such circumstances.[14]

Anticipated impact

According to Government data, the NSIB could result in approximately 1,000-1,830 notifications a year, with call-ins/full national security assessments conducted in 70-95 cases a year and remedies anticipated in around 10 cases a year.

By comparison, the UK’s competition regime typically investigates less than 100 deals per year whilst the EU merger control regime – which is one of the toughest in the world – covered 645 cases in 2019 (283 of which were under its simplified procedure regime). Further, the current regime has involved just 12 interventions on a national security basis since 2002 (the peak year for interventions being 2019, in which 4 interventions were issued).

If enacted, this would clearly take the UK from having one of the lightest touch regimes in Europe to arguably one of the most expansive. However, it is also clear that, whilst the Government expects to be engaged and have the opportunity to review transactions (which may have consequences in terms of deal timelines and give rise to hold separate obligations in anticipated and/or completed deals), most transactions will be cleared without any intervention by way of remedies.

Timing and next steps

It is anticipated that the National Security and Investment Act will commence during the first half of next year. The Second Reading of the NSIB took place on Tuesday 17 November 2020. The committee stage (where the bill will undergo a line by line examination, with every clause agreed to, changed or removed) is scheduled for 24 November 2020.

The consultation period on the mandatory notification sectors closes on 6 January 2021. Industry is encouraged to respond and provide views on the scope of the sectors and activities currently covered by this process – as currently drafted, there a number of areas where the scope is potentially over-reaching and insightful, technical input from the market will be welcome.

Other points of note

The national security assessment will run in parallel to any competition assessment for a transaction (which will continue to be conducted by the UK Competition and Markets Authority, the “CMA”). However, whilst the two processes will be separate, there will be interactions and, in practice, outcomes will be intertwined. In particular, the legislation will include a power that would allow the SoS to intervene where competition remedies run contrary to national security interests, where this is considered necessary and proportionate. Further, the Government’s intention is that, as far as possible, any national security remedies will be aligned with competition remedies (and that the timetables will be aligned, to the extent possible, within the statutory framework to achieve this).

The Government is clear that any conflict between competition remedies and risks posed to national security will be resolved after consultation with the CMA and that mutually beneficial remedies will be imposed wherever possible. Interaction between the two regimes will be covered in more detail in a Memorandum of Understanding with the CMA. The CMA will also be under a duty to share information with the SoS and provide other assistance reasonable required to perform its functions.

What does this mean for transacting parties?

This new proposal will have a potentially significant impact on targets, sellers and acquirers alike.

For targets and sellers, it will be incumbent to undertake a review of the target’s business and activities to consider if they fall within one of the sensitive sectors and to be alive to this risk in conjunction with future capital raises, share transfers or sales of all or parts of the business, including sales of key assets, going forwards. There may be structuring options to consider. If targets or sellers are undertaking sale processes, there will also need to be greater scrutiny of acquirers in assessing transaction risk. Auction processes should also take into account the risk that a bidder may pose.

For acquirers (whether domestic or foreign – as the regime is not only designed to capture non-UK parties) consideration should be given to their ultimate controllers, the track record of those people in relation to other acquisitions or holdings, whether the acquirer has control or significant holdings in other entities active in the same sector and any relevant criminal offences or known affiliations of parties involved in the transaction, whereby an acquirer may be regarded as giving rise to acquirer risk from the SoS perspective. It is not clear to what extent parties may be able to pre-clear or seek constructive guidance in advance from the Government. There is reference in the proposals, for example, to parties having informal discussions with the Government earlier on in a sale process. However, these appear to envisage a situation whereby a specific transaction is under contemplation. Further, the Government has flagged that in a competitive process any mandatory or voluntary notification should only be made by the final bidder or acquirer in the process.

Transactions and investment deals will need to be structured to accommodate this additional risk including through introducing additional conditionality. The UK has always been open to foreign investment and, consistent with this, no transaction has been blocked to date on national security concerns. However, strict conditions have been required for deals to be cleared under the current regime. Such implications need to be considered up-front by an acquirer when planning a transaction (and risk, procedural and timing impacts appropriately factored into contractual documentation).

Given the increasing and widening emphasis on screening transactions for national security concerns, it will be important to analyse early on the risks of Government intervention/concerns arising for a transaction. Whilst concerns will be highest in the context of a takeover by a buyer affiliated to a ‘hostile state or actor’ or where a buyer owes allegiance to a hostile state or organisation, foreign nationality more generally has been considered a risk factor under the current regime. Interventions have been launched, for example, in the past, in response to investments from the United States, Canada and elsewhere in Europe. Any foreign entity may thus face close scrutiny. Concerns over asset stripping and rationalisation motivations may also provoke investigations when the acquiring company is a UK entity.

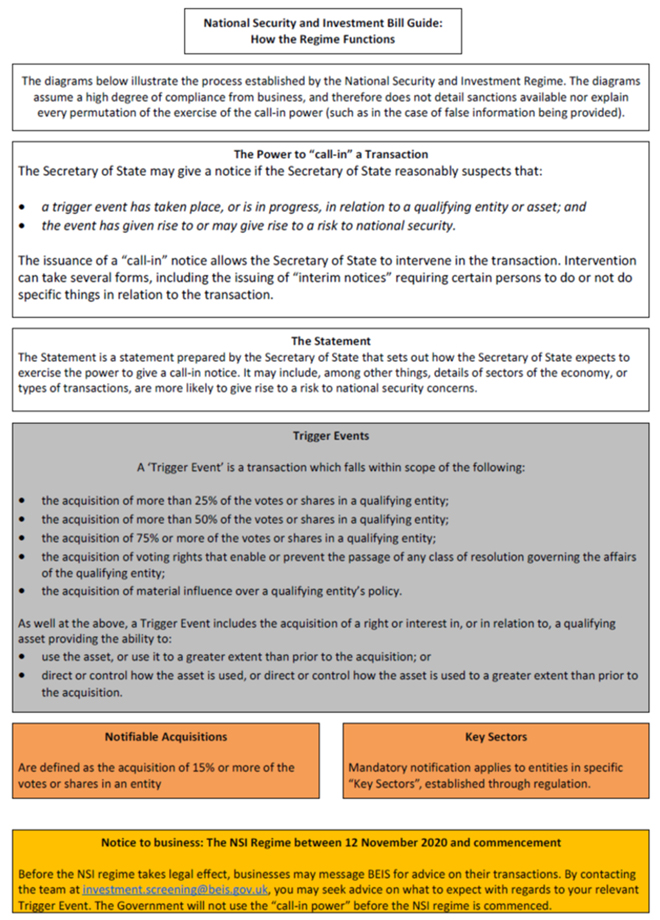

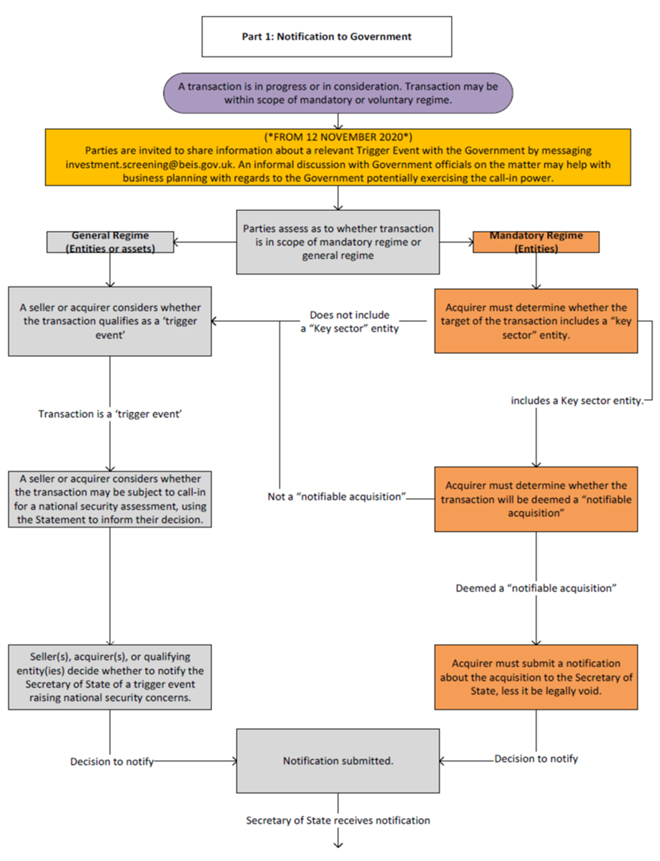

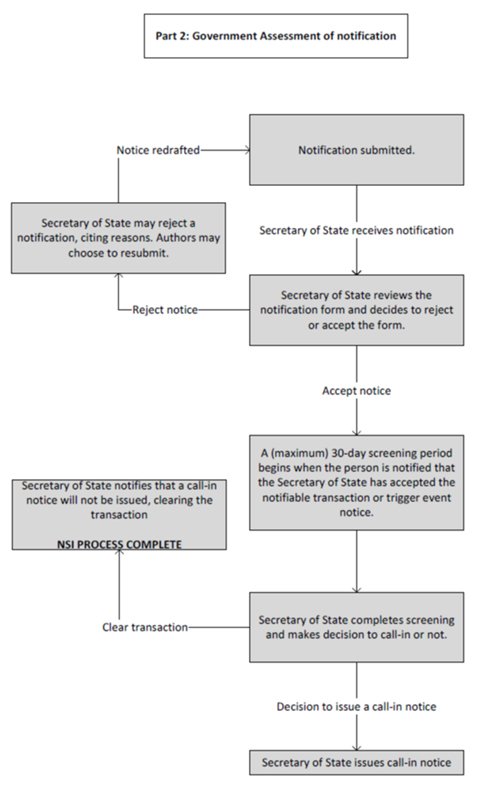

Appendix – Government Guidance, Flow Charts on Process [15]

[2] ‘Entities’ are also broadly defined , covering any entity (whether or not a legal person) but not individuals. This includes a company, LLPs, other body corporates, partnerships, unincorporated associations and trusts.

[3] See further: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-office-for-investment-to-drive-foreign-investment-into-the-uk.

The draft Statutory Statement of Policy Intent published concerning the new national security regime also specified with respect to the new regime that: “Its use will not be designed to limit market access for individual countries; the transparency, predictability, and clarity of the legislation surrounding the call-in power is designed to support foreign direct investment in the UK, not to limit it.”

[4] See further the Government’s press release on this development, available here: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-powers-to-protect-uk-from-malicious-investment-and-strengthen-economic-resilience.

[7] See further: https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/national-security-and-investment-mandatory-notification-sectors.

[8] See, to this effect, the draft Statement of Policy Intent published: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-security-and-investment-bill-2020/statement-of-policy-intent.

[9] The regime only applies to issues of national security. Other public interest issues concerning e.g. media plurality, financial stability or the UK’s ability to maintain in the UK the capability to combat, and to mitigate the effects of, public health emergencies, will continue to be dealt with through the existing channels and processes.

[10] The types of tangible moveable property of greatest national security interest will vary across sectors but are likely to be closely linked to the activities of companies in areas more likely to raise national security concerns (as identified through the requirements of the mandatory notification regime). Examples of such assets may include physical designs and models, technical office equipment, and machinery.

[12] See: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-security-and-investment-bill-2020/statement-of-policy-intent.

[13] CMPs are civil proceedings in which the court is provided with evidence by one party that is not shown to another party to the proceedings. Any restricted evidence is heard in closed hearings, with the other party(ies) excluded and their interests represented by a Special Advocate. The rationale behind CMPs is to ensure that evidence can still be used in the proceedings, rather than being excluded completely under the doctrine of public interest immunity (and, specifically, on grounds of national security).

[14] Further examples are listed below – however, this is not an exhaustive list of proposed sanctions.

Failure to notify or non-compliance with interim or final orders could result in fines of up to 5% of total worldwide turnover or £10 million (whichever is higher) on businesses and prison sentences and/or fines for individuals. Failing to comply, without reasonable excuse, with an information or attendance request could results in fines on companies and fines and/or imprisonment for individuals. It will also be an offence to knowingly or recklessly supply information that is false or misleading in a material respect – punishable through fines and/or through the sentencing of individuals to prison. There would also be an opportunity for the SoS to reconsider decisions and (re-)review a trigger event in these circumstances, even if outside of the prescribed ‘call-in’ period for voluntary transactions. Unauthorised use or disclosure of regime information would also see individuals subject to imprisonment and/or a fine.

[15] Source: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/934438/process-flow-chart-for-businesses.pdf.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions that you may have regarding the issues discussed in this update. For further information, please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, any member of the firm’s Antitrust and Competition, Mergers and Acquisitions, or International Trade practice groups, or the authors:

Ali Nikpay – Partner – Head of Competition and Consumer Law, London (+44 (0) 20 7071 4273, anikpay@gibsondunn.com)

Deirdre Taylor – Partner – Antitrust and Competition, London (+44 (0) 20 7071 4274, dtaylor2@gibsondunn.com)

Attila Borsos – Partner – Competition and Trade, Brussels (+32 2 554 72 11, aborsos@gibsondunn.com)

Selina S. Sagayam – Partner – International Corporate, London (+44 (0) 20 7071 4263, ssagayam@gibsondunn.com)

Sarah Parker – Associate – Competition and Consumer Law, London (+44 (0) 78 3324 5958, sparker@gibsondunn.com)

Tamas Lorinczy – Associate – Corporate, London (+44 (0) 20 7071 4218, tlorinczy@gibsondunn.com)

© 2020 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.