July 26, 2018

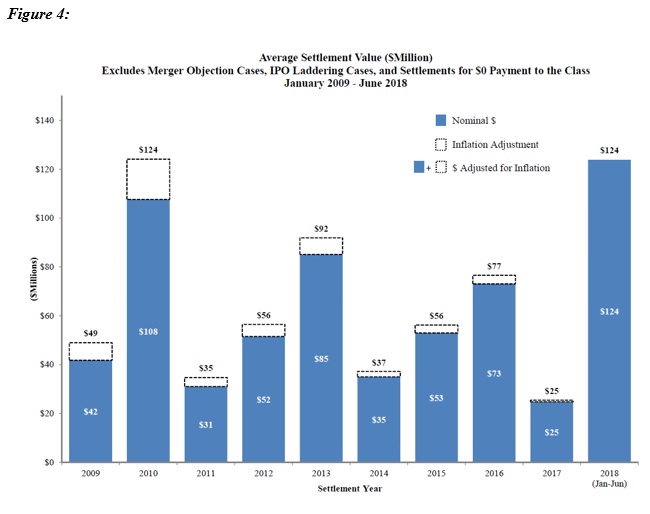

The continued explosion in the number of securities class action filings is once again the big headline in our half yearly update. The now-sustained increase in both the number of filings and average and median settlement amounts—including a five-fold increase in average settlement amounts in the first half of 2018 to $124 million from $25 million in 2017—is causing significant alarm in the securities defense bar, prompting insurance carriers and others to seek regulatory reform and explore other alternatives to reverse these trends. The trends and critical case law updates are explored in detail below.

I. Filing and Settlement Trends

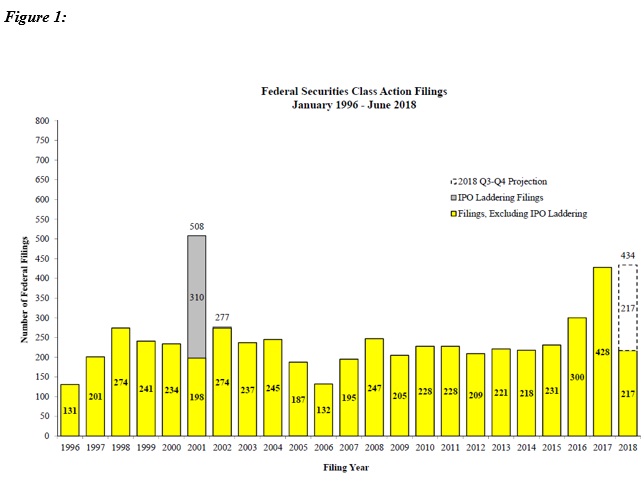

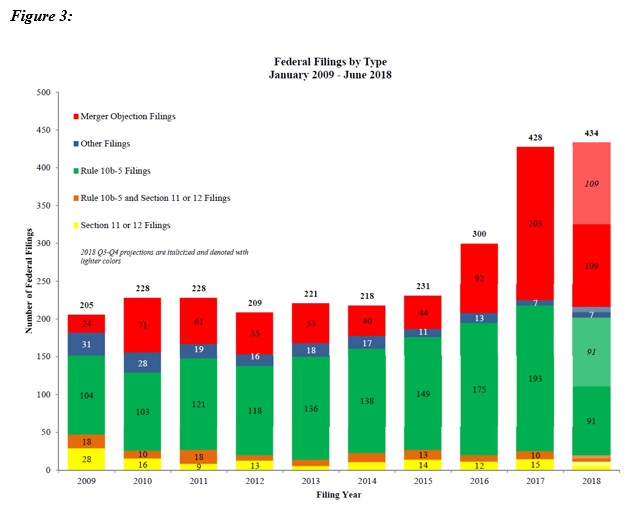

In the first half of 2018, new securities class actions filings are on pace to repeat the 2017 results of significantly exceeding annual filing rates in previous years. According to a newly-released NERA Economic Consulting study (“NERA”),[1] 217 cases were filed in the first half of this year. While this lags slightly behind the first half of 2017, which saw 246 new filings, the 2018 rate nonetheless substantially outpaces the average number of 235 cases filed annually over the five years from 2012-2016. At the current pace, filings for 2018 are projected to reach 434 total cases—compared with 428 total cases filed in 2017. So-called “merger objection” cases, which more than doubled each year from 2015 to 2017, remain a driving force although the rate of increase in the number of such cases filed has greatly slowed. NERA projects that the number of merger objection cases filed in federal court in 2018 will be slightly greater than 2017, representing 218 projected filings of the 434 total projected federal filings for 2018 compared to 203 merger objection filings in 2017.

While the total number of such federal filings is not projected to increase drastically over the number of filings in 2017, both average and median settlement amounts are up significantly in the first half of 2018. Notably, median settlement amounts as a percentage of alleged investor losses also increased significantly, and have broken a pattern that has persisted for decades. In the last fifteen years, median settlement amounts have never exceeded 3% of total alleged investor losses. In the first half of 2018, that percentage is 3.9%, up sharply from 2.6% in 2017.

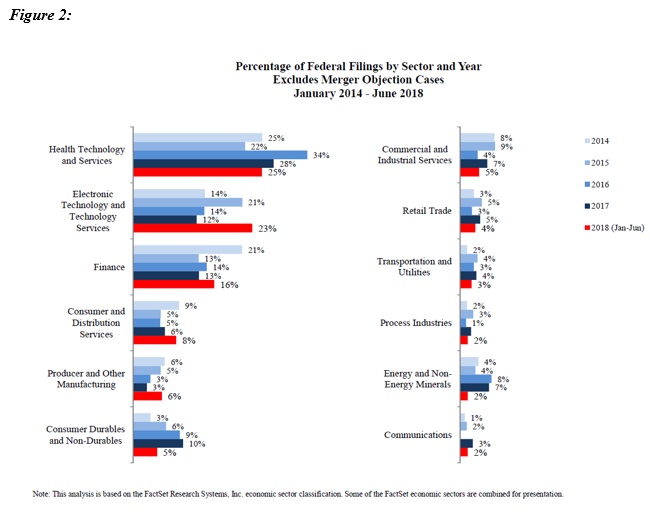

The industry sectors most frequently sued in 2018 continue to be healthcare (25% of all cases filed), tech (23%), and finance (16%). Cases filed against healthcare companies in the first half of 2018 are showing the continuation of a downward trend from a spike in 2016. Cases filed against tech and finance companies are both on pace for increases from 2017. The tech sector’s share of filings is showing a near-doubling from 2017, with the first-half 2018 numbers indicating 23% of cases filed in this sector—up from 12% in 2017.

A. Filing Trends

Figure 1 below reflects filing rates for the first half of 2018 (all charts courtesy of NERA). Two hundred and seventeen cases have been filed so far this year, annualizing to 434 cases. This figure does not include the many class suits filed in state courts or the rising number of state court derivative suits, including many such suits filed in the Delaware Court of Chancery.

B. Mix of Cases Filed in First Half of 2018

1. Filings by Industry Sector

New filings for the first half of 2018 show a marked increase in cases targeting defendants in the tech industry, reversing a downward trend from 2016 and 2017. Tech sector filings have spiked significantly, from 12% of the total in 2017 to 23% of the total for the first half of 2018. Healthcare still owns the dubious honor as the top industry in the category of new filings, at 25% of total filings, but the industry is showing a continued downward trend from a high of 34% in 2016. Among the top five industries by number of new cases filed so far in 2018, healthcare is the only sector on pace for fewer filings than in 2017. Tech, finance, consumer and distribution services, and producer/manufacturing sectors each are on pace for increases from 2017. Outside of the top-five industry sectors for new filings, all other measured industry sectors show a decline in their respective 2017 shares of new cases filed. Of these sectors, the two reflecting the largest decline are consumer durables and non-durables (at 5%, down from 10% in 2017) and energy and non-energy minerals (at 2%, down from 7% in 2017).

2. Merger Cases

As shown in Figure 3, 109 “merger objection” cases have been filed in federal court in the first half of 2018 alone—continuing a high rate of such filings from 2017, which saw a drastic increase in the number of such cases over previous years. If the 2018 pace continues, this year will see an increase both in the total number of these cases filed in federal court and in the percentage of federal filings that are merger objection filings.

C. Settlement Trends

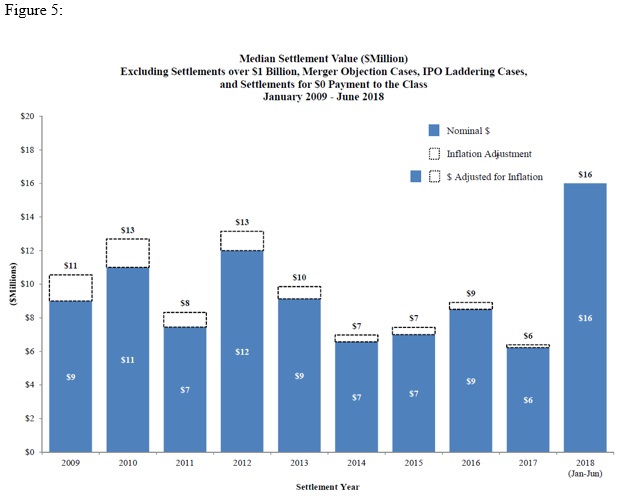

As Figure 4 shows below, after a significant decrease year-over-year from 2016 to 2017, average settlements jumped from $25 million in 2017 to an eye-popping $124 million in the first half of 2018. As we have noted in previous updates, in any given year the statistics can mask a number of important factors that contribute to any particular settlement value. Average and median settlement statistics also can be influenced by the timing of large settlements. In 2017, there were no settlements at $1 billion or greater; while in the first half of 2018, $3.0 billion of a total $3.8 billion of aggregate settlement value is accounted for by settlements of $1 billion or more. Removing settlements over $1 billion shows a much smaller increase in the average settlement—from $25 million in 2017 to $28 million in the first half of 2018. However, as Figure 5 shows, the median settlement value, even when excluding settlements over $1 billion, still shows a significant increase from $6 million in 2017 to $16 million in the first half of 2018. In the first half of 2018, the percentage of settlements above $100 million shows a continuation of a downward trend—from 15% in 2016 to 8% in 2017 to 6% in the first half of 2018. The percentage of settlements below $10 million decreased substantially from 61% in 2017 to 39% in the first half of 2018, while over the same period settlements valued between $20 million and $49.9 million increased substantially from 14% to 32%.

Mid-Year 2018 Securities Litigation Update: What to Watch for in the Supreme Court

A. Making Sense of “Gibberish”—Cyan and the Securities Litigation Uniform Standards Act

As readers may recall, on November 28, 2017, the Supreme Court heard oral argument in Cyan, Inc. v. Beaver County Employees Retirement Fund, No. 15-1439. The fundamental issue in Cyan was whether Congress intended to preclude state court jurisdiction over “covered class actions” under the Securities Act of 1933 (the “1933 Act”) when it enacted the Securities Litigation Uniform Standards Act (“SLUSA”) in 1998. As amended by SLUSA, the 1933 Act provides for concurrent state and federal court jurisdiction “except as provided in section 77p of this title with respect to covered class actions.” 15 U.S.C. § 77v(a). The Court also considered a secondary question raised by the U.S. government as amicus curiae: whether SLUSA granted defendants the ability to remove a 1933 Act class action from state to federal court.

As we reported in our 2017 Year-End Securities Litigation Update, at oral argument, several Justices referred to SLUSA’s jurisdictional limitation as “obtuse” at best and “gibberish” at worst and seemed frustrated by the statute’s confusing language. See, e.g., Transcript of Oral Argument at 11, 47. Those concerns were not reflected, however, in the Court’s decision: In an opinion authored by Justice Kagan and joined by all other Justices, the Court concluded on March 20, 2018 that SLUSA did not preclude state court jurisdiction over 1933 Act suits. Cyan, Inc. v. Beaver Cty. Employees Ret. Fund, 138 S. Ct. 1061, 1069 (2018).

Parsing the statutory text, the Court explained that the “except clause” in § 77v(a) only precluded concurrent jurisdiction over class actions based on state law. Id. Consequently, “as a corollary of that prohibition,” SLUSA allowed state courts the ability to remove state law-based suits to federal courts for dismissal. Id. The Court also noted that the statute was silent with respect to class actions based on federal law, and interpreted this silence to suggest that Congress did not intend to deprive state courts of the ability to hear those cases. Id.

The Court declined to accept Cyan’s textual argument that the definition of “covered class actions,” located in § 77p(f)(2), which denotes individual lawsuits seeking damages on behalf of more than 50 people or in which at least one named party seeks “to recover damages on a representative basis,” as well as groups of lawsuits seeking damages on behalf of more than 50 people or which have been “joined, consolidated, or otherwise proceed as a single action,” exempted all sizable class actions from state court jurisdiction, explaining that a “definition does not provide an exception, but instead gives meaning to a term.” Id. at 1070. The Court elaborated that Cyan’s interpretation of the definition “fits poorly with the remainder of the statutory scheme” because it would prohibit state courts from hearing any 1933 Act class actions made up of more than 50 class members regardless of whether or not they were “covered class actions” under § 77p. Id. at 1071.

The Court similarly rejected Cyan’s legislative intent arguments, noting that SLUSA was initially created in order “[t]o prevent plaintiffs from circumventing” the requirements of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act (“PSLRA”). Id. at 1067. The Court thus reasoned that “stripping state courts of jurisdiction over 1933 Act class suits” was simply not something Congress needed or intended to do in order to effect that goal. Id. at 1072–73. Cyan also argued that SLUSA’s legislative reports demonstrated Congress’s intent to keep securities class actions solely in federal court. Id. at 1072. In response, the Court explained that SLUSA already ensured that most securities class action cases would be brought in federal court by amending the Securities Act of 1934 to provide for exclusive jurisdiction in federal court. Id. at 1073. Ultimately, the Court summarized its decision by stating that “we have no sound basis for giving the except clause a broader reading than its language can bear.” Id. at 1075.

The Court similarly rejected the Solicitor General’s argument that § 77p(c) permits the removal of 1933 Act cases to federal court if they allege the types of misconduct listed in § 77p(b), including “false statements or deceptive devices in connection with a covered security’s purchase or sale.” Id. Instead, the Court held that in light of its determination that § 77p(b) only prohibited claims based on state law, the state law claims were removable, and therefore subject to dismissal in federal court. Id. However, federal law suits—like Cyan—which alleged 1933 Act violations are not “covered class actions,” and therefore, they “remain subject to the 1933 Act’s removal ban.” Id.

B. China Agritech and the Limits of American Pipe Tolling

As discussed in our 2017 Year-End Securities Litigation Update, on December 8, 2017, the Supreme Court granted certiorari in China Agritech, Inc. v. Resh, No. 17-432. The principal issue raised by China Agritech was whether a statute of limitations is tolled for absent class members who bring successive class actions outside the applicable limitations period, rather than just individual claims.

By way of background, as readers will know, the Supreme Court held in American Pipe and Construction Co. v. Utah, 414 U.S. 538 (1974), that the statute of limitations is tolled by “the commencement of the original class suit” “for all purported members of the class who make timely motions to intervene after the court has found the suit inappropriate for class action status.” Id. at 553. The Court then extended this holding in Crown, Cork & Seal Co. v. Parker, 462 U.S. 345 (1983), to include “class members . . . choos[ing] to file their own suits,” effectively allowing the statute of limitations to remain tolled for individual suits by any “members of the putative class until class certification is denied.” Id. at 354. Crown went on to hold that in the event class certification is denied, “class members may [then] choose to file their own suits or to intervene as plaintiffs in the pending action.” Id.

In Smith v. Bayer, 564 U.S. 299, 314 n.10 (2011), the Court summarized the rule of American Pipe and Crown thusly: “[A] putative member of an uncertified class may wait until after the court rules on the certification motion to file an individual claim or move to intervene in the suit.”

At oral argument on March 26, 2018, China Agritech argued that American Pipe should not be expanded to toll the claims of “absent class members who have not shown diligence . . . by not filing their own claims when class certification was denied” and that the Court should “require that anyone who wants to file a class action come to court early and in no event later than the running of the statute of limitations.” Transcript of Oral Argument at 3. Several of the Justices questioned China Agritech’s push to force additional actions to file while other actions may still be pending. Justice Sotomayor, for example, observed that “if my financial interest is moderately sized or small sized, there’s no inducement for me to do anything other than what American [Pipe] tells me to do, which is to wait until the class issues are resolved before stepping forward. . . . [Y]our regime is encouraging the very thing that American Pipe was trying to avoid, which is having a multiplicity of suits being filed and encouraging every class member to come forth and file their own suit.” Id. at 8–9.

On the other hand, Justice Gorsuch commented that extending American Pipe could lead plaintiffs to “stack [cases] forever, so that try, try again, [] the statute of limitations never really has any force in these cases[.]” Id. at 39. Chief Justice Roberts echoed this concern, noting that American Pipe’s holding applied only to plaintiffs who sought to bring individual claims past the statute of limitations period and that “if you allow [plaintiffs to bring class actions after the statute of limitations have run every time class certification is denied], you’ve got to allow the third and then the fourth and the fifth. And there’s no end in sight.” Id. at 46.

Ultimately, these concerns about a never-ending succession of class actions prevailed, and on June 11, 2018, the Court issued an 8-1 opinion declining to extend American Pipe to successive class actions. Specifically, the Court held that after the denial of class certification, a putative class member may not commence a new class action beyond the time allowed by the statute of limitations. China Agritech, Inc. v. Resh, 138 S. Ct. 1800, 1804 (2018).

The Court dismissed Resh’s concerns that such a holding would result in a “needless multiplicity” of protective class action filings, pointing to the Second and Fifth Circuits—both of which had long ago declined to extend American Pipe in this context—and neither of which has faced excessive filings as a result. Id. at 1810. The Court went on to explain that its decision would not harm prospective plaintiffs or require them to file a protective, duplicative class action simply to protect against possible statute of limitations issues because “[a]ny plaintiff whose individual claim is worth litigating on its own rests secure in the knowledge that she can avail herself of American Pipe tolling if certification is denied to a first putative class.” Id. (emphasis added). Furthermore, even if courts faced an influx of multiple pre-emptive class actions, district courts have sufficient tools, “including the ability to stay, consolidate, or transfer proceedings” to deal with such an increase in an efficient way. Id. at 1811.

Justice Sotomayor concurred in the decision, stating that although she agreed with the majority that plaintiffs in the instant case should not be permitted to bring successive class actions under the American Pipe tolling provision, she believes that this bar should apply only to class actions brought under the PSLRA. Id. (Sotomayor, J., concurring).

Gibson Dunn represented the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, Retail Litigation Center, and American Tort Reform Association as amici curie supporting China Agritech in this case.

C. Lorenzo: Can Misstatement Claims Be Repackaged as Fraudulent Scheme Claims Post-Janus?

On June 18, 2018, the Supreme Court granted certiorari in Lorenzo v. Securities and Exchange Commission, No. 17-1077, which raises the question of whether a securities fraud claim premised on a misstatement that does not meet the elements set forth in the Court’s decision in Janus Capital Group, Inc. v. First Derivative Traders for a Rule 10b-5(b) claim can instead be pursued as a “fraudulent scheme” claim under Rule 10b-5(a) and 10b-5(c). See Petition for Writ of Certiorari at i. The decision could limit the scope of Rule 10b-5 and significantly affect how the SEC chooses to pursue fraud claims against defendants who are alleged to have made false statements to investors.

We expect that, in Lorenzo, the Court will further explicate its holding in Janus that only the “maker” of a fraudulent statement could be held liable for that misstatement under Section 10(b) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and Rule 10b-5(b). 564 U.S. 135, 142 (2011). In Lorenzo, the SEC accused brokerage firm director Francis Lorenzo of violating Rule 10b-5 by providing false information about a debenture offering to two potential investors. Lorenzo claimed that he did not intentionally convey any false information and that he had merely copied and pasted information from an email he received from his boss without checking to see if it was accurate. In the Matter of Francis V. Lorenzo, File No. 3-15211, at 15–16 (Dec. 31, 2013).

Nevertheless, an SEC Administrative Law Judge found that Lorenzo had violated all three parts of Rule 10b-5: (a) employing a “device, scheme or artifice to defraud;” (b) making a false statement or omitting information that misleads investors; and (c) engaging in conduct that “would operate as a fraud or deceit.” Id. at 8–17. This decision was affirmed by the Commission. Id. at 17. Lorenzo was barred from associating with other advisers, brokers, or dealers in the industry and from participating in penny stock offerings and ordered to pay a $15,000 penalty and to cease and desist from further violations. Id. at 1.

Lorenzo appealed to the D.C. Circuit, arguing that under Janus, he could not be liable for a violation of Rule 10b-5(b) because he had not intended to convey false information to the investors and had merely transmitted information he received from his firm. The D.C. Circuit agreed, finding that Lorenzo was not “the ‘maker’ of the false statements” and therefore could not be liable for a 10b-5(b) violation. Lorenzo v. Sec. & Exch. Comm’n, 872 F.3d 578, 580 (D.C. Cir. 2017). Nevertheless, the D.C. Circuit upheld the SEC’s findings that Lorenzo violated Rule 10b-5(a) and (c) and remanded back to the SEC to redetermine the appropriate sanctions. Id. at 595. Judge Kavanaugh dissented, arguing that the majority’s decision “create[d] a circuit split by holding that mere misstatements, standing alone, may constitute the basis for so-called scheme liability under [Rules 10b-5(a) and (c)]—that is, willful participation in a scheme to defraud—even if the defendant did not make the misstatements.” Id. at 600 (Kavanaugh, J., dissenting).

Lorenzo filed a petition for a writ of certiorari to the Supreme Court on January 26, 2018. The petition contended that the D.C. Circuit’s holding “allows the SEC and private plaintiffs to sidestep Janus’ carefully drawn out elements of a fraudulent statement claim merely by relabeling the claim—with nothing more—as a fraudulent scheme claim.” Petition for Writ of Certiorari at 5. Lorenzo identified a 3-2 circuit split on the issue, noting that Second, Eighth, and Ninth Circuits have all held that a fraudulent scheme claim cannot be premised on misstatements alone, id. at 17–20, while the Eleventh and D.C. Circuits opine that a person can be liable for violations of Rule 10b-5(a) and (c) even where they are not the “maker” of an untrue statement, id. at 20–21. The Petition further argued that the D.C. Circuit’s opinion “erases the important distinction between primary and secondary violators of the securities laws and opens up large numbers of defendants who are secondary actors at best to claims for securities fraud—claims that would otherwise be barred in private litigation.” Id. The SEC filed its opposition brief on May 2, 2018, arguing that the Second, Eighth, Ninth, Eleventh, and D.C. Circuit’s “inconsistent” rulings on Rule 10b-5(a) and (c) violations are distinguishable because they “have involved different conduct by the defendants, and they arose out of suits brought by private plaintiffs, rather than (as in this case) an administrative enforcement action brought by the SEC.” Respondent’s Opposition to Writ of Certiorari at 8. Respondent further contended that “petitioner does not identify any conflict over the scope of liability under Section 17(a)(1),” which uses the same language as Rule 10b-5(a) and makes it unlawful “to employ any device, scheme, or artifice to defraud.” Id.

The Supreme Court granted certiorari on June 18, 2018. We expect that the parties will submit their briefs to the Supreme Court in the Fall of 2018, with oral argument to follow in the coming months. We will continue to monitor this matter and provide an update in our 2018 Year-End Securities Litigation Update.

D. Securities Enforcement Updates

In our 2017 Year-End Securities Litigation Update, we noted that the Court granted certiorari in two major SEC enforcement actions: Lucia v. SEC, No. 17-130 and Digital Realty Trust, Inc. v. Somers, No. 16-1276. For further analysis of Lucia and Digital Realty, please see our 2018 Mid-Year Securities Enforcement Update.

II. Delaware Developments

A. Transactions Involving A Potentially Controlling Stockholder

Four recent decisions involved transactions with a potentially controlling stockholder. In one, the Court of Chancery extended the MFW standard of review-shifting framework to all transactions in which a controlling stockholder receives a “non-ratable” benefit. In another, the court concluded a company’s visionary founder was a controlling stockholder in part due to longstanding public acknowledgement of his influence. In a similar case, the Court of Chancery held demand was excused because a majority of a board was not independent of its visionary founder, but stopped short of deciding whether that founder was a controlling stockholder. Last, the Court of Chancery declined to enjoin a controlling stockholder from interfering with a special committee’s plan to dilute its voting control from around 80% to 17%.

1. Controlling stockholder transactions satisfying the requirements of MFW will be reviewed under the business judgment rule.

In Kahn v. M & F Worldwide Corp., the Delaware Supreme Court held that the business judgment rule applies to a merger between a controlling stockholder and its subsidiary where the merger is conditioned on “both the approval of an independent, adequately-empowered Special Committee that fulfills its duty of care; and the uncoerced, informed vote of a majority of the minority stockholders.” 88 A.3d 635, 644 (Del. 2014). Late last year, the Court of Chancery extended MFW to stock reclassifications. IRA Tr. FBO Bobbie Ahmed v. Crane, 2017 WL 7053964, at *9 (Del. Ch. Dec. 11, 2017). In Crane, NRG Yield, Inc. was dominated by a controlling stockholder, NRG Energy, Inc. (“NRG”), as part of a “yieldco” ownership structure. When stock issuances threatened NRG’s control, the NRG-dominated board sought to eliminate or reduce the voting rights of the publicly-traded stock class through reclassification. The independent Conflicts Committee negotiated an agreement with NRG whereby both NRG and minority stockholders were issued new classes of stock with 1/100 of a voting share each, substantially slowing down NRG’s vote dilution, and conditioned the deal on the approval of a majority of minority stockholders. The measure passed, and a minority stockholder challenged the transaction. As a matter of first impression, the Court of Chancery held that the reclassification’s compliance with MFW shifted the standard of review from entire fairness to the business judgment rule because “[t]he animating principle of the MFW framework is that . . . the controlled company replicates an arms-length bargaining process in negotiating and executing a transaction.” Id. at *11. Importantly, however, the Court of Chancery expressly extended its holding beyond reclassifications, reasoning that there is “no principled basis on which to conclude that the dual protections in the MFW framework should apply to squeeze-out mergers but not to other forms of controller transactions.” Id.

2. Elon Musk is Tesla’s controlling stockholder.

In In re Tesla Motors Inc. Stockholder Litigation, the Court of Chancery denied defendants’ motion to dismiss and found, “in a close call,” that the complaint sufficiently alleged that Tesla’s CEO and Chairman Elon Musk is its controlling stockholder for purposes of its 2016 acquisition of SolarCity, a Musk-related entity. 2018 WL 1560293 (Del. Ch. Mar. 28, 2018). According to the court, Musk’s ownership of 22% of Tesla’s outstanding stock and a combination of “other factors” made him a controlling stockholder for purposes of the SolarCity acquisition. First, Musk pitched the proposed transaction to the board on three separate occasions, and the board did not consider any other solar power companies or form an independent committee to consider the proposal. Second, a majority of the five directors who approved the acquisition “were interested in the Acquisition or not independent of Musk.” Id. at *17. Third, the court relied on Musk’s and the board’s public statements acknowledging Musk’s influence on Tesla, such as Musk’s role in shaping the company’s vision, hiring executives and engineers, and raising capital. The court concluded that the combination of Musk’s control over the board, board level conflicts, and the public acknowledgment of Musk’s influence allowed a reasonable inference that Musk enjoyed “the equivalent of majority voting control” in the transaction. Id. at *15.

3. A majority of Oracle’s board of directors is not independent of Larry Ellison.

In a similar vein, the Court of Chancery found that plaintiffs sufficiently alleged demand futility against the board of Oracle Corporation because the majority of the board was not independent of Larry Ellison, Oracle’s co-founder and Chairman, for purposes of the acquisition of NetSuite, Inc., another Ellison-founded company. In re Oracle Corp. Derivative Litig., 2018 WL 1381331 (Del. Ch. Mar. 19, 2018). Because a breach of loyalty claim belongs to the company, in the normal course a plaintiff must demand that the board take a particular action before bringing a lawsuit. In lieu making a demand on the board, however, a plaintiff may plead that demand is excused because a majority of the directors were not independent or disinterested. At the time of the challenged acquisition, Ellison owned roughly 28% of Oracle and about 45% of NetSuite. After concluding that Ellison and the four manager directors were not independent due to Ellison’s outsized impact on the company’s day-to-day operations, the court went on to find that three other directors, including two of the three directors on the Special Committee that approved the NetSuite acquisition, had sufficient entanglements with Ellison to call into question their independence with respect to the acquisition of the Ellison-controlled NetSuite. Specifically, those directors had substantial business ties with Ellison, and two of the three directly owed their director positions to Ellison because a majority of non-Ellison stockholders disapproved of their performance on the Compensation Committee. Without deciding whether Ellison “qualif[ies] as a controller,” the court held that the “constellation of facts” were sufficient, “taken together, [to] create reasonable doubt” about the ability of the directors to “objectively consider a demand.” Id. at *16, *18.

4. Equity favors a controller’s right to protect its control preemptively.

In CBS Corp. v. National Amusements, Inc., CBS and a special committee of five independent directors sought to enjoin CBS’s controlling stockholder from interfering with their plan to dilute its voting power from around 80% to 17%. 2018 WL 2263385, at *1 (Del. Ch. May 17, 2018). Through her control of National Amusements, Inc. (“NAI”), Shari Redstone controls 79.6% of CBS’s voting power, even though NAI owns only 10.3% of CBS’s economic stake. Id. According to the plaintiffs, dilution was justified by Ms. Redstone’s efforts to combine CBS with Viacom, which she also controls, and various actions she took over two years that “present[ed] a significant threat of irreparable and irreversible harm to [CBS]” and “the interests of the stockholders who hold approximately 90% of [its] economic stake.” Id. at *1, *4. The Court of Chancery agreed that the plaintiffs allegations were “sufficient to state a colorable claim for breach of fiduciary duty against Ms. Redstone and NAI as CBS’s controlling stockholder,” id. at *4. Nonetheless, the court declined to issue the unprecedented temporary restraining order because case law “expressly endorsed a controller’s right to make the first move preemptively to protect its control interest” and subjected exercise of that right to further judicial review. Id.

This dispute is ongoing, and an expedited trial is scheduled for the fall.

B. Bad Faith, Waste, And The Business Judgment Rule

Delaware’s default standard of review, the business judgment rule presumes that a company’s directors make business decisions in good faith, on an informed basis, and in the honest belief that the decisions are in the best interest of the company. In general, unless a plaintiff rebuts this presumption, its claims will not survive a motion to dismiss. In the first half of 2018, plaintiffs survived a motion to dismiss in three notable cases.

1. Directors who knowingly cause a corporation to violate the law act in bad faith.

A plaintiff’s breach of loyalty claim survived a motion to dismiss where the complaint adequately alleged that “the directors knowingly permitted [the company] to continue with marketing campaigns containing false representations in violation of law.” City of Hialeah Emps.’ Ret. Sys. v. Begley, 2018 WL 1912840, at *4 (Del. Ch. Apr. 20, 2018). The defendants in Begley were directors of a company that operated DeVry University. Id. at *1. According to the complaint, the defendants authorized marketing campaigns that misrepresented DeVry graduates’ employment rates and income despite knowing the information was wrong and the campaigns violated federal law, resulting in the company paying over $100 million to settle various government lawsuits and investigations. Id. The Court of Chancery denied the defendants’ motion to dismiss, concluding that specific facts alleged in the complaint supported a reasonable inference that “the defendants chose to maintain DeVry’s marketing campaign and operate DeVry in violation of law because that was the route to maximizing DeVry’s profits.” Id. at *3. Operating a company in violation of law to maximize profits “expose[s] [directors] to liability for acting in bad faith, which is a breach of the duty of loyalty.” Id. at *3.

2. A board commits waste when it fails to consider terminating an incapacitated employee earning millions of dollars.

In an “extreme factual scenario,” the Court of Chancery found that plaintiffs successfully pleaded demand futility and stated a claim for corporate waste with respect to payments made to CBS’s controlling stockholder, Sumner Redstone, during his twenty-month incapacitation beginning in 2014. Feuer on behalf of CBS Corp. v. Redstone, 2018 WL 1870074 (Del. Ch. Apr. 19, 2018), judgment entered sub nom. Feuer v. Redstone, 2018 WL 2006677 (Del. Ch. 2018). Despite having the inherent ability to terminate his employment agreement, CBS continued making payments to Redstone after he fell critically ill. Id. at *12. Because the board “made no effort to reckon with the financial consequences of Redstone’s severe incapacity,” id. at *14, however, and Redstone’s contributions during that time “were so negligible and inadequate in value that no person of ordinary, sound business judgment would deem them worth the millions of dollars in salary that the Company was paying him,” the court held that the board faced “a substantial threat of liability for non-exculpated claims for waste and/or bad faith,” id. at *13, and denied the defendants’ motion to dismiss.

3. A transaction negotiated by an allegedly conflicted CEO is not protected by the business judgment rule.

In In re Xerox Corp. Consolidated Shareholder Litigation, the New York Supreme Court recently enjoined a multi-billion dollar merger of Xerox Corp. and Fujifilm Holdings Corp. (“Fuji”), concluding the plaintiffs adequately rebutted the business judgment rule and showed a likelihood of success on the merits of their claims that the merger was not entirely fair. 2018 WL 2054280, at *8 (N.Y. Sup. Apr. 27, 2018). The merger arose from a decades-long joint venture between Xerox and Fuji whose governing documents made it difficult for Xerox to do a deal with anyone else. Id. at *2. The transaction was structured so that Fuji would transfer its 75% stake in the joint venture without additional consideration to Xerox and be issued enough new Xerox shares to become its 50.1% stockholder; simultaneously, Xerox would borrow $2.5 billion to pay its non-Fuji stockholders a special dividend in the same amount. Id. at *1. The Supreme Court enjoined the deal, however, because Xerox’s CEO, who negotiated the deal, was “massively conflicted” and a majority of Xerox’s board lacked independence. Id. at *7. According to the court, the CEO was conflicted because after Carl Icahn, Xerox’s largest stockholder, stated his preference for an all-cash deal and convinced the board to fire the CEO, the CEO negotiated a non-cash deal in which he would remain as the CEO of the combined entity. Id. The court also concluded that Xerox’s board lacked independence from the CEO because he recommended by name a majority of Xerox’s directors to continue as directors after the merger. Id.

This decision is on appeal to the First Department.

B. Delaware Continues to Restrict Appraisal Awards

In our 2017 Year-End Update, we reported on the significant shift in Delaware appraisal law in Dell, Inc. v. Magnetar Global Event Driven Master Fund Ltd., 177 A.3d 1 (Del. 2017). In Dell, the Delaware Supreme Court held that “[t]here is no requirement that a company prove that the sale process is the most reliable evidence of its going concern value in order for the resulting deal price to be granted any weight,” id. at 35, and reversed “the trial court’s decision to give no weight to any market-based measure of fair value.” Id. at 19.

The Court of Chancery began interpreting the high court’s directives in the first half of 2018. In Verition Partners Master Fund Ltd. v. Aruba Networks, Inc., for example, the Court of Chancery interpreted Dell as (i) endorsing a company’s unaffected market price and deal price as reliable indicators of value when, respectively, the market for the company’s stock is efficient or a third-party merger is negotiated at arm’s length; and (ii) cautioning against relying on discounted cash flow analyses when such reliable market indicators are available. 2018 WL 2315934, at *1 (Del. Ch. May 21, 2018) (awarding $17.13 per share—the unaffected market price and significantly below the $24.67 deal price—as the only reliable indicator of value). And in In re AOL, Inc., the Court of Chancery found the deal was not “Dell-compliant” based both on provisions in the merger agreement and on the CEO’s public statements that the deal was “done.” 2018 WL 1037450, at *1 (Del. Ch. Feb. 23, 2018) (conducting its own discounted cash flow analysis where the deal price was unreliable, but awarding a price close to it). These two cases suggest that while there may continue to be some uncertainty as to when and how the Delaware Court of Chancery will choose among market indicators of a company’s value, the Court will continue to enforce the Supreme Court’s directive to use market factors to determine the fair value of a company’s stock, which should continue to keep appraisal awards in check.

III. Loss Causation Developments

The first half of 2018 saw several notable circuit court opinions addressing loss causation, including continued developments relating to Halliburton Co. v. Erica P. John Fund, Inc., 134 S. Ct. 2398 (2014), discussed below in Section VI.

Leading the way, on January 31, 2018, the Ninth Circuit issued a per curiam opinion resolving a perceived ambiguity in prior precedent regarding the correct test for loss causation under the Exchange Act. See Mineworkers’ Pension Scheme v. First Solar Inc., 881 F.3d 750 (9th Cir. 2018). The First Solar court held that “to prove loss causation, plaintiffs need only show a causal connection between the fraud and the loss . . . by tracing the loss back to the very facts about which the defendant lied.” Id. at 753 (internal citations and quotation marks removed). This test does not require loss causation to rest on a revelation of fraud to the marketplace. Instead, “[a] plaintiff may also prove loss causation by showing that the stock price fell upon the revelation of an earnings miss, even if the market was unaware at the time that fraud had concealed the miss.” Id. at 754. In so holding, the Ninth Circuit rejected a more “restrictive view,” in which “[s]ecurities fraud plaintiffs can recover only if the market learns of the defendants’ fraudulent practices” before the claimed loss. Id. at 752. As long as the revelation that caused the decline in a company’s stock price is related to the facts allegedly concealed, a plaintiff has adequately plead loss causation for the purposes of stating a claim under the Exchange Act. At least one district court has relied upon First Solar to deny a defendants’ motion for summary judgment on the issue of loss causation. See Mauss v. NuVasive, Inc., No. 13CV2005 JM (JLB), 2018 WL 656036, at *5 (S.D. Cal. Feb. 1, 2018) (rejecting defendants’ argument that plaintiffs failed to show that the market learned of the actual fraud, because “the Ninth Circuit does not require that fraud be affirmatively revealed to the market to prove loss causation”).

Over in the Fourth Circuit, a split panel issued a decision on February 22, 2018 holding that a plaintiff can plead loss causation based on “an amalgam” of two theories: corrective disclosure and the materialization of a concealed risk. Singer v. Reali, 883 F.3d 425 (4th Cir. Feb. 22, 2018). The complaint in Singer alleged that TranS1, Inc., a medical device company, and its officers made misrepresentations and omissions in public filings by failing to disclose that a large portion of TranS1’s revenues were generated by a purportedly fraudulent reimbursement scheme. In vacating the lower court opinion dismissing the complaint, the majority concluded that two disclosures highlighted in the complaint—a Form 8-K reporting that TranS1 had received a subpoena from the Department of Health and Human Services and an analyst report revealing that the subpoena sought communications relating to certain reimbursements—sufficiently revealed information for investors to recognize that defendants had perpetrated a fraud on the market. Id. at 447. Moreover, the allegation that the disclosures resulted in a 40% stock price drop was sufficient to plead that the revelation of the purported fraud was at least “one substantial cause” of the drop. Id. The decision in Singer adds to the debate about the extent to which the disclosure of a government investigation, without a later disclosure of wrongdoing, is sufficient to establish loss causation. See, e.g., Public Employees’ Retirement System of Mississippi v. Amedisys, Inc., 769 F.3d 313, 323-24 (5th Cir. 2014) (“commencement of government investigations . . . do not, standing alone, amount to a corrective disclosure,” but can support a finding of loss causation when coupled with other disclosures); Meyer v. Greene, 710 F.3d 1189, 1201 (11th Cir. 2013) (company disclosure of SEC investigations were not “corrective disclosures” for the purposes of loss causation); SEC investigation was insufficient to plead loss causation).

2018 Mid-Year Securities Litigation Update: Falsity of Opinions Under Omnicare

As we have reported in our past several updates, courts continue to grapple with the reach of Omnicare, Inc. v. Laborers Dist. Council Const. Indus. Pension Fund, 135 S. Ct. 1318 (2015). The Supreme Court’s Omnicare decision addressed the scope of liability for false opinion statements under Section 11 of the Securities Act. The Court held that “a sincere statement of pure opinion is not an ‘untrue statement of material fact,’ regardless whether an investor can ultimately prove the belief wrong.” Id. at 1327. An opinion statement can give rise to liability only when the speaker does not “actually hold[] the stated belief,” or when the opinion statements contains “embedded statements of fact” that are untrue. Id. at 1326–27. In addition, the Court held that a factual omission from a statement of opinion gives rise to liability only when the omitted facts “conflict with what a reasonable investor would take from the statement itself.” Id. at 1329.

In the first half of 2018, two courts issued notable opinions about how Omnicare applies to disclosure of financial information. The United States District Court for the Central District of California denied a motion to dismiss when plaintiffs alleged that defendants issued false opinions about the company’s financial health by recognizing revenue in violation of Generally Accepted Accounting Principles. In re Capstone Turbine Corp. Sec. Litig., No. CV 15-8914, 2018 WL 836274, at *7–8 (C.D. Cal. 2018). The parties disputed whether the amount of revenue recognized in a particular period is an opinion or a statement of fact, and the court held that “revenue is an opinion with an embedded fact,” clarifying that “[t]he fact is the actual quantity of the sales and the opinion is that collectability on these sales is reasonably assured.” Id. at *6. The court further concluded that the falsity of the opinion portions of the statements regarding revenue recognition were sufficiently pled under Omnicare because the complaint alleged facts showing that defendants knew collectability was not reasonably assured. Id. at *7. In the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts, plaintiffs brought a suit under Massachusetts security law, which closely mirrors federal securities law, alleging that an auditor’s statement of compliance with PCAOB standards was false. Miller Inv. Trust v. Morgan Stanley & Co., No. 11-12126, 2018 WL 1567599 (D. Mass. Mar. 30, 2018) appeal docketed No. 18-1460 (1st Cir. May 17, 2018). Acknowledging that courts have reached contradictory conclusions as to whether an auditor’s statements of compliance are statements of fact or statements of opinion, the court ultimately reasoned that “statements by auditors of their own compliance with [standards] are statements of fact” even though “one auditor may apply the standards differently from another.” Id. at *11–12.

Omnicare continued to act as a pleading barrier to securities fraud claims in the first half of this year, with courts paying close attention to the role of context in determining whether an opinion could be allegedly false. For example, in Martin v. Quartermain, investors alleged that a mining company’s opinion statements expressing continued optimism in its mining operations were false when the company failed to disclose that one of its experts had expressed doubt. No. 17-2135, 2018 WL 2024719 (2d Cir. May 1, 2018). Investors alleged that the opinion was false on two theories: first, that company did not actually believe its statement of continued optimism given that one of its experts had expressed concern with the mine’s projected viability; and, second, that the company’s failure to disclose this concern was an omission that made the opinion statement misleading to a reasonable investor. Id. at 2. As to the first theory, the court held that the plaintiffs failed to show that the company believed the concerned expert instead of the optimistic projection, so plaintiffs failed to show that the company did not hold the stated belief. As for the second theory, the Second Circuit concluded that omitting the concerned expert’s views did not render the opinion misleading when viewed in context, even if the company knew “but fail[ed] to disclose some fact cutting the other way.” Id. at *3 (citing Omnicare, 135 S. Ct. at 1329). The court reasoned that the risk that a mine will not be successful is part of the “broader frame” of the industry that a reasonable investor would understand as part of the “weighing of competing facts.” Id. (citing Omnicare, 135 S. Ct. 1329).

Similarly, the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York rejected allegations that a company’s guardedly optimistic assessments about the implementation of a new software program were false because they did not include disclosure of implementation challenges the company was facing. Oklahoma v. Firefighters Pension and Ret. Sys. v. Xerox Corp., 300 F. Supp. 3d 551, 575 (S.D.N.Y. 2018), appeal docketed No. 18-1165 (2d Cir. April 20, 2018). The court reasoned that these “quintessential statements of opinion” were not false even though the defendant only disclosed in general terms the challenges it was facing because a reasonable investor “does not expect that every fact known to an issuer supports its opinion statement.” Id. at 577 (citing Omnicare, 135 S. Ct. 1329). Another court in the Southern District of New York permitted an omission claim to proceed, but this case may simply highlight how difficult it is to overcome Omnicare. Plaintiffs alleged that Blackberry’s optimistic sales projections were contradicted by omitted data Blackberry had about its sales numbers. Pearlstein v. Blackberry Ltd., No. 13-CV-7060, 2018 WL 1444401 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 19, 2018). In their second amended complaint, plaintiffs supplemented these allegations with evidence that came to light in a related criminal trial that revealed that Blackberry had adverse sales data when it issued its optimistic projections. The court concluded that Blackberry’s failure to disclose adverse sales data could plausibly be misleading to a reasonable investor. Id. at *3–4. Most plaintiffs, of course, do not have the benefit of evidence unearthed in a related criminal proceedings to demonstrate that an opinion is false.

Further highlighting the barriers imposed by Omnicare, two courts in the first half of this year also rejected claims alleging that pharmaceutical companies made false statements about their clinical trials. One court held that plaintiff’s allegations that defendants issued a false opinion when they opined on a drug’s efficacy but failed to disclose an allegedly flawed clinical methodology did not support a Section 10(b) claim because plaintiff’s claims amounted to nothing more than an attack on the trial’s methodology. Hoey v. Insmed Inc., No. 16-4323, 2018 WL 902266, at *9, 14 (D.N.J. Feb. 15, 2018). The court noted that the failure to reveal that the results of a study were inaccurately reported or that a study was manipulated to conceal data may support allegations that an omission made a statement of opinion misleading, but that disagreements over the proper methodology will not support such an allegation. Likewise, a company’s failure to disclose the recurrence of a known side effect did not render opinions that the clinical trial was “predictable and manageable” and that the company was seeing “favorable clinical data” false or misleading since a reasonable investor would expect the recurrence of a known side effect. In re Stemline Therapeutics, Inc. Sec. Litig., No. 17 CV 832, 2018 WL 1353284, at *5 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 15, 2018) appeal docketed No. 18-1044 (2d Cir. Apr. 12, 2018).

Courts in the first half of 2018 also provided guidance for companies making opinion statements about legal and compliance risks. The United States District Court for the Southern District of Texas rejected allegations that a company’s opinion that it was in “substantial compliance” with regulations was false on the ground that a regulatory agency had sent informal communications and had issued two infraction notices about recordkeeping practices on a different and small part of the company’s large-scale and pipeline operations. In re Plains All Am. Pipeline, L.P. Sec. Litig., No. H:15-02404 2018 WL 1586349, at * 38–39 (S.D. Tex. Mar. 30, 2018) appeal docketed No. 18-20286 (5th Cir. May 7, 2018). The court reasoned that the opinion that the company was in “substantial compliance,” when combined with other hedges and qualifications, would inform a reasonable investor that the company was operating in substantial, but not perfect, compliance with relevant laws. Id. at *39. On the other hand, the United States District Court for the Northern District of Georgia permitted a claim to proceed where the defendant opined that it had been in material compliance with the laws and that pending lawsuits had no merit because plaintiffs’ complaint sufficiently alleged that defendant had been informed by legal counsel that its model was not in compliance with applicable laws. In re Flowers Foods, Inc. Sec. Litig., No. 7:16-CV-222, 2018 WL 1558558, at *7–8 (M.D. Ga. Mar. 23, 2018).

IV. Halliburton II Market Efficiency and “Price Impact” Cases

Courts across the country continue to grapple with implementing the Supreme Court’s landmark ruling in Halliburton Co. v. Erica P. John Fund, Inc., 134 S. Ct. 2398 (2014) (“Halliburton II“), and the first half of 2018 did not bring any new decisions from the federal circuit courts of appeal. In Halliburton II, the Supreme Court preserved the “fraud-on-the-market” presumption—a presumption enabling plaintiffs to maintain the common proof of reliance that is essential to class certification in a Rule 10b-5 case—but made room for defendants to rebut that presumption at the class certification stage with evidence that the alleged misrepresentation had no impact on the price of the issuer’s stock. Two key questions continue to recur: first, how should courts reconcile the Supreme Court’s explicit ruling in Halliburton II that direct and indirect evidence of price impact must be considered at the class certification stage, Halliburton II, 123 S. Ct. at 2417, with its previous decisions holding that plaintiffs need not prove loss causation or materiality until the merits stage, see Erica P. John Fund, Inc. v. Halliburton Co., 563 U.S. 804 (2011) (“Halliburton I“); Amgen Inc. v. Conn. Ret. Plans & Trust Funds, 568 U.S. 455 (2013). And second, what standard of proof must defendants meet to rebut the presumption with evidence of no price impact of Basic Inc. v. Levinson, 485 U.S. 224, 237 (1988)?

As we reported in our 2017 Year-End Securities Litigation Update, the Second Circuit recently addressed both of these key questions in Waggoner v. Barclays PLC, 875 F.3d 79 (2d Cir. 2017) (“Barclays“) and Ark. Teachers Ret. Sys. v. Goldman Sachs, 879 F.3d 474 (2d Cir. 2018) (“Goldman Sachs“). Those decisions remain the most substantive interpretations of Halliburton II. Barclays addressed the standard of proof necessary to rebut the presumption of reliance and held that after a plaintiff establishes the presumption of reliance applies, defendant bears the burden of persuasion to rebut the presumption by a preponderance of the evidence. As we have previously noted, this puts the Second Circuit at odds with the Eighth Circuit, which cited Rule 301 of the Federal Rules of Evidence when reversing a trial court’s certification order on price impact grounds, see IBEW Local 98 Pension Fund v. Best Buy Co., 818 F.3d 775, 782 (8th Cir. 2016), because Rule 301 assigns only the burden of production—i.e., producing some evidence—to the party seeking to rebut a presumption, but “does not shift the burden of persuasion, which remains on the party who had it originally.” In Goldman Sachs, the Second Circuit directed that price impact evidence must be analyzed prior to certifying a class, even if price impact “touches” on the issue of materiality. Goldman Sachs, 879 F.3d at 486. In April, the Supreme Court declined to take up the Barclays case, Waggoner v. Barclays PLC, 875 F.3d 79 (2d Cir. 2017), cert. denied, 138 S. Ct. 1702 (2018), and Goldman Sachs remains pending before the Southern District of New York on remand, where an evidentiary hearing and oral argument on class certification was held on July 25, 2018.

The Third Circuit is poised to be the next to substantively address the issue, as the court recently agreed to review Li v. Aeterna Zentaris Inc., 324 F.R.D. 331 (D.N.J. 2018) (“Aeterna“). See Order, Vizirgianakis v. Aeterna Zentaris, Inc., No. 18-8021 (3d Cir. Mar. 30, 2018). That ruling is likely to address the nature of the evidence a defendant must put forward to defeat plaintiff’s presumption of reliance. Before the district court, defendants sought to rebut plaintiffs’ presumption of reliance by challenging plaintiffs’ expert’s event study for failing to demonstrate price impact to the industry’s standard level of confidence. Aeterna, 324 F.R.D. at 344-45. The argument failed to convince the court, which noted that (1) plaintiffs’ report had been prepared to show an efficient market, not to demonstrate price impact, (2) the report’s failure to find a movement with 95% confidence did not prove the “lack of price impact with scientific certainty,” and (3) defendants did not present any competent evidence of their own to demonstrate price impact. Id. at 345 (citation omitted). Defendants’ 23(f) petitions requesting review of class certification on price impact grounds are pending in several other circuit courts of appeal.

We will continue to monitor developments in these and other cases.

The following Gibson Dunn lawyers assisted in the preparation of this client update: Monica Loseman, Matt Kahn, Brian Lutz, Laura O’Boyle, Mark Perry, Lissa Percopo, Lauren Assaf, Jefferson Bell, Michael Eggenberger, Kim Lindsay Friedman, Leesa Haspel, Mark Mixon, Emily Riff, and Zachary Wood.

Gibson Dunn lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these developments. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, or any of the following members of the Securities Litigation Practice Group Steering Committee:

Brian M. Lutz – Co-Chair, San Francisco/New York (+1 415-393-8379/+1 212-351-3881, [email protected])

Robert F. Serio – Co-Chair, New York (+1 212-351-3917, [email protected])

Meryl L. Young – Co-Chair, Orange County (+1 949-451-4229, [email protected])

Thad A. Davis – San Francisco (+1 415-393-8251, [email protected])

Jennifer L. Conn – New York (+1 212-351-4086, [email protected])

Ethan Dettmer – San Francisco (+1 415-393-8292, [email protected])

Barry R. Goldsmith – New York (+1 212-351-2440, [email protected])

Mark A. Kirsch – New York (+1 212-351-2662, [email protected])

Gabrielle Levin – New York (+1 212-351-3901, [email protected])

Monica K. Loseman – Denver (+1 303-298-5784, [email protected])

Jason J. Mendro – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3726, [email protected])

Alex Mircheff – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7307, [email protected])

Robert C. Walters – Dallas (+1 214-698-3114, [email protected])

Aric H. Wu – New York (+1 212-351-3820, [email protected])

© 2018 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.