February 1, 2018

2017 brought a furious and nearly unprecedented rate of new filings, as well as several important developments in securities law. This year-end update highlights what you most need to know in securities litigation developments and trends for the latter half of 2017:

- The Supreme Court heard oral argument in Cyan, which should resolve whether state courts have subject matter jurisdiction over class actions brought under the Securities Act of 1933. Although there is evidence that the pace of filings of state securities lawsuits has slowed somewhat, defendants in pending state court cases have generally been unsuccessful in using Cyan to procure a stay or remove such cases to federal court.

- The Supreme Court also granted certiorari in China Agritech to address whether the filing of a class action tolls the statute of limitations for absent class members who bring subsequent class actions.

- A settlement by the parties in Leidos means the Supreme Court will not yet resolve the split between the Second and Ninth Circuits over whether omission of a disclosure required by Item 303 of the SEC’s Regulation S-K is actionable under Section 10(b) and Rule 10b–5 of the federal securities laws, leaving uncertainty as to the scope of companies’ disclosure obligations under Item 303.

- We explain important developments in Delaware courts, including the Court of Chancery’s application of Corwin, as well as the Delaware Supreme Court’s treatment of (1) deal price in appraisal litigation, (2) Caremark claims, (3) shareholder ratification of director self-compensation decisions, and (4) collateral estoppel in the context of prior determinations of demand futility.

- Finally, we highlight significant cases interpreting and applying the Supreme Court’s decisions in Omnicare and Halliburton II.

I. Filing and Settlement Trends

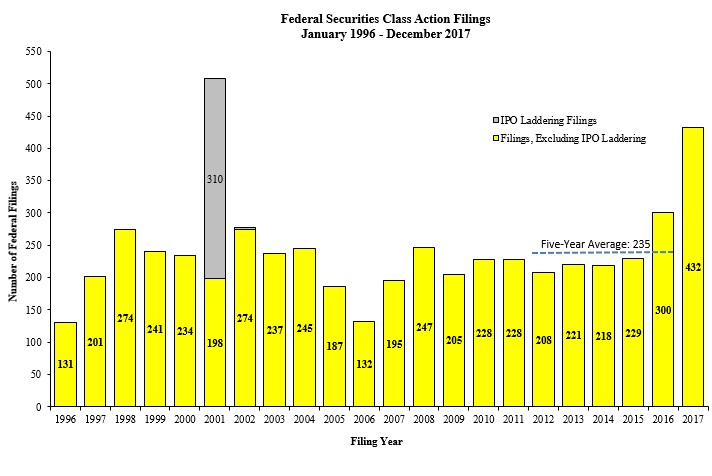

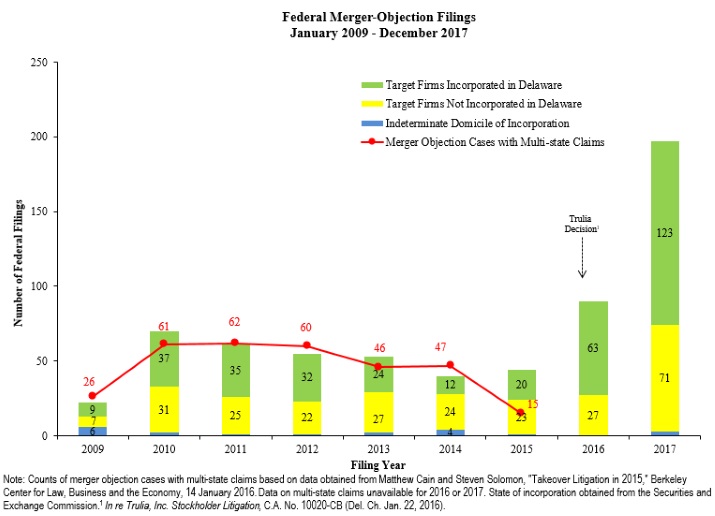

The number of new securities class actions filed in federal court in 2017 significantly exceeded filings in previous years. According to a newly-released NERA Economic Consulting study (“NERA”), 432 cases were filed in 2017, compared to 300 in 2016 and an average of 235 cases filed annually over the last five years. The only year in the past two decades that remotely compares is 2001, but that year included a significant number of so-called “IPO laddering” cases. Although there is not a similar singular explanation for the marked increase in filings in 2017, so-called “merger objection” cases appear to be one driving force. According to NERA, nearly 200 merger objection cases were filed in federal court in 2017, more than double the number filed in 2017 (90), and quadruple the number filed in 2015 (46).

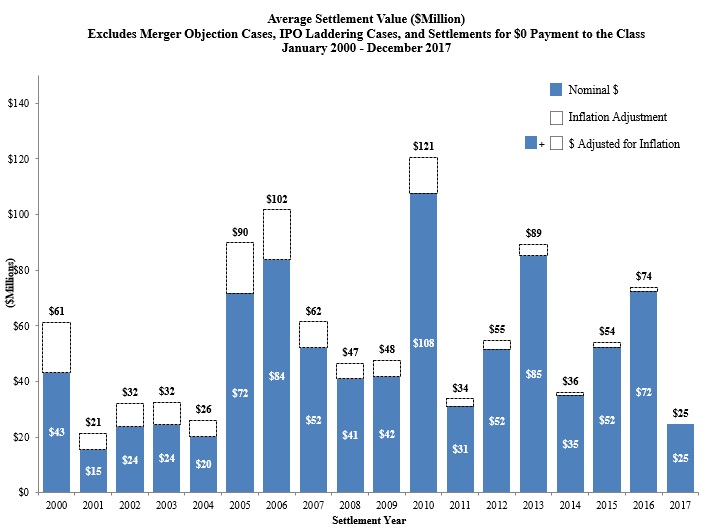

The other big takeaway from the data may be more welcome news: while the number of filings is up, both average and median settlement amounts were down in 2017. More than 60% of settlements in 2017 were under $10 million, while only 8% were more than $100 million and none exceeded $500 million. Most significantly, median settlement amounts as a percentage of investor losses continue to reflect a pattern that has persisted for decades. In the last fifteen years, median settlement amounts have never exceeded 3% of total alleged investor losses. In 2017, that percentage was 2.6%.

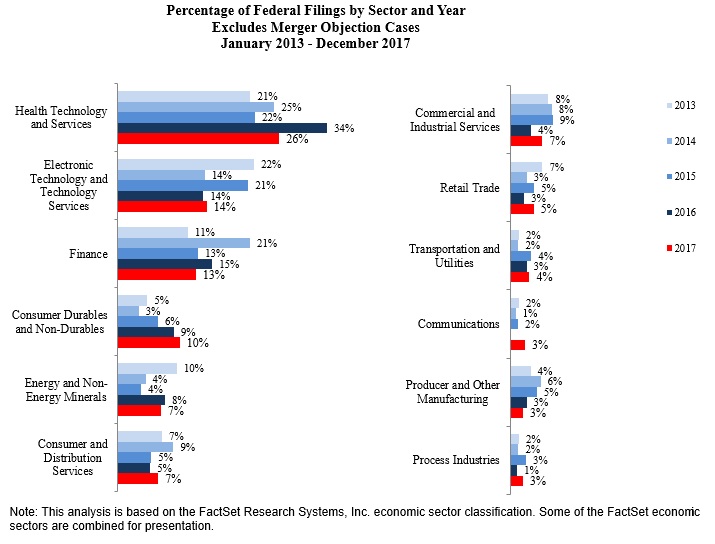

The industry sectors most frequently sued in 2017 continue to be healthcare (26% of all cases filed), tech (14%), and finance (14%). 2017 also continued the upward trend in the percentage of cases filed against consumer products companies, which accounted for 10% of cases in 2017.

A. Filing Trends

Figure 1 below reflects filing rates for 2017 (all charts courtesy of NERA). Four hundred and thirty-two cases were filed this year. This figure does not include the many class suits filed in state courts or the increasing number of state court derivative suits, including many such suits filed in the Delaware Court of Chancery. Those state court cases represent a “force multiplier” of sorts in the dynamics of securities litigation today.

Figure 1:

B. Mix of Cases Filed in 2017

1. Filings By Industry Sector

Following a significant bump in the percentage of cases filed against healthcare companies last year, new 2017 filings show a relative decline in this sector. Health technology and services still accounts for more than 1 out of every four 4 cases, however. The percentage of new cases involving consumer products continues a three-year trend upward, now comprising 10% of all filings in 2017. The proportion of cases in the electronics, finance, and energy sectors remained roughly consistent as compared to 2016. See Figure 2 below.

Figure 2:

2. Merger Cases

As shown in Figure 3 below, almost 200 “merger objection” cases were filed in 2017. This is more than double the number of such cases filed in 2016, and more than quadruple the number filed in 2014 and 2015. Note that this statistic only tracks cases filed in federal courts. Most M&A litigation occurs in state court, particularly the Delaware Court of Chancery. But as we have discussed in our prior updates, the Delaware Court of Chancery announced in early 2016 in In re Trulia Inc. Stockholder Litigation, 29 A.3d 884 (Del. Ch. 2016) that the much-abused practice of filing an M&A case followed shortly by an agreement on “disclosure only” settlement is just about at an end. This is likely driving an increasing number of cases to federal court.

Figure 3:

C. Settlement Trends

As Figure 4 shows, median settlements were $6 million in 2017, lower than the median amounts in any of the last dozen years. In any given year, of course, the statistics can mask a number of important factors that contribute to any particular settlement value, such as (i) the amount of D&O insurance; (ii) the presence of parallel proceedings, including government investigations and enforcement actions; (iii) the nature of the events that triggered the suit, such as the announcement of a major restatement; (iv) the range of provable damages in the case; and (v) whether the suit is brought under Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act or Section 11 of the Securities Act. Median settlement statistics also can be influenced by the timing of large settlements, any one of which can skew the numbers, but those big settlements were markedly absent this year. In 2017, the percentage of settlements above $100 million decreased sharply from 15% to 8% of all settlements, and there were no settlements over $500 million for the first time in the last decade. At the same time, the percentage of settlements below $10 million increased from 51% to 61%.

Figure 4:

D. Emerging Areas: Data Breaches and Cryptocurrencies

One much-publicized source of securities litigation in 2017 was corporate data breaches. Although previous breach-related derivative suits have been largely unsuccessful, many believe that a significant increase in the number of securities fraud cases targeting companies’ disclosures related to major data breaches is likely. In the second half of 2017 shareholders launched class actions against, among others, Equifax and PayPal that are currently pending. The results of these cases could affect the number and scope of similar securities cases we see in 2018 and beyond.

Another area to watch closely in the coming year is crytpocurrencies. The dramatic rise in value of Bitcoin and series of initial coin offerings in 2017 have been met with increased attention not only from the media but also the SEC and securities litigation plaintiffs’ attorneys. Indeed, the end of 2017 saw securities class actions filed against multiple cryptocurrency-related entities including Tezos, Centra Tech, Monkey Capital, ATBCOIN, and The Crypto Company.

We will monitor these and other similar cases in 2018.

II. What to Watch for in the Supreme Court

A. Leidos Removed from Oral Argument Calendar after Parties Reach Settlement

In our 2017 Mid-Year Securities Litigation Update, we highlighted Leidos v. Indiana Public Retirement System, No. 16-581, in which the Supreme Court was scheduled to hear oral argument on November 6, 2017. As readers will recall, Leidos concerned a circuit split on whether a private class action under Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5 could be premised on alleged omissions from disclosures required by Item 303 of the SEC’s Regulation S-K, 17 C.F.R. § 229.3030. However, the Court has removed the case from its oral argument calendar after the parties informed the Court that they had agreed to settle the litigation. The case is now being held in abeyance pending the district court’s approval of the parties’ settlement agreement. See Stipulation of Settlement (Dkt. 179), In re SAIC, Inc. Secs. Litig., No. 1:12-cv-01353-DAB (S.D.N.Y. Dec. 13, 2017).

We analyze the implications of the Leidos settlement, including the continuing unresolved split between, on one hand, the Second Circuit and, on the other hand, the Third and Ninth Circuits, in Section V below.

Gibson Dunn represents petitioner in this case.

B. Making Sense of “Gibberish” – Cyan and the Securities Litigation Uniform Standards Act

As readers will recall, the Supreme Court granted the petition for a writ of certiorari in Cyan v. Beaver County Employees Retirement Fund, No. 15-1439, on June 27, 2017. The fundamental issue in Cyan is whether Congress intended to preclude state-court jurisdiction over “covered class actions” under the Securities Act of 1933 when it enacted the Securities Litigation Uniform Standards Act (“SLUSA”) in 1998. As amended by SLUSA, the Securities Act provides for concurrent jurisdiction “except as provided in section 77p of this title with respect to covered class actions.” 15 U.S.C. § 77v(a).

Federal courts have been sharply divided over this issue in recent years. Of note, courts in the Second Circuit have favored exclusive federal jurisdiction while courts in the Ninth Circuit have permitted state courts to exercise concurrent jurisdiction. This divergence is significant because the Second and Ninth Circuits handle more federal securities litigation than the other circuits combined. California state courts have been particularly active in this area since 2011, when the California Court of Appeal held that states have concurrent jurisdiction. See Luther v. Countrywide Fin. Corp., 195 Cal. App. 4th 789 (2011). Indeed, Cyan originated in California state court, where the lower court denied the petitioners’ motion for a judgment on the pleadings for lack of subject matter jurisdiction.

In their merits brief, petitioners (defendants below) argue that while state courts generally have concurrent jurisdiction to decide claims under the Securities Act, SLUSA constricted state courts’ jurisdiction to cases “except as provided in section 16 with respect to covered class actions [i.e., those involving fifty or more people].” Brief for Petitioners at 10 (quoting 15 U.S.C. § 77v(a)). In other words, petitioners contend that by referencing covered class actions within an “except” clause, Congress intended to define the “covered” Securities Act claims that could no longer be adjudicated by state courts.

In their responsive brief on the merits, respondents (plaintiffs below) argue that Congress did not intend to alter the longstanding concurrent jurisdiction of state courts to hear claims under the Securities Act when it enacted SLUSA. Brief for Respondents at 6. Rather, respondents maintain that SLUSA only stripped state courts of jurisdiction to hear so-called “mixed claims,” or those covered class actions raising both state-law and federal Securities Act claims. Id. at 13–14.

The United States, appearing as amicus curiae, argues that SLUSA does not preclude state-court jurisdiction over Securities Act claims, but that it did permit removal of Securities Act suits “like this one”: “class actions that assert claims only under the [Securities] Act.” Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae at 7.

On November 28, 2017, the Supreme Court heard oral argument. Several Justices, seemingly frustrated by the statute’s confusing language, characterized SLUSA’s jurisdictional limitation as “obtuse” at best and “gibberish” at worst. See Transcript of Oral Argument at 11, 47. Justice Alito in particular found the statute so poorly drafted that he asked the government’s lawyer whether there is “a certain point at which we say this means nothing, we can’t figure out what it means, and, therefore, it has no effect, it means nothing?” Id. at 41. On the other hand, Justice Gorsuch noted that that it was the Supreme Court’s “job to try and give effect whenever possible to Congress’s language.” Id. at 47.

We expect a decision in Cyan by the end of the 2017 Supreme Court Term in June 2018. We will continue to monitor developments in this area and report on any updates in our 2018 Mid-Year Securities Litigation Update.

C. China Agritech and the Limits of American Pipe Tolling

On December 8, 2017, the Supreme Court granted certiorari in China Agritech, Inc. v. Resh, No. 17-432, to consider whether a statute of limitations is tolled for absent class members who bring subsequent class actions outside the applicable limitations period. While China Agritech does not directly affect substantive securities laws, the holding will likely be of great significance to securities litigators who routinely encounter class actions.

China Agritech is set to address the familiar class action tolling rules announced by the Supreme Court in American Pipe and Construction Co. v. Utah, 414 U.S. 538 (1974), and Crown, Cork & Seal Co. v. Parker, 462 U.S. 345 (1983). In American Pipe, the Supreme Court held that “the commencement of the original class suit tolls the running of the statute for all purported members of the class who make timely motions to intervene after the court has found the suit inappropriate for class action status.” 414 U.S. at 553. In Crown, the Supreme Court extended the American Pipe rule to “class members . . . choos[ing] to file their own suits.” 462 U.S. at 354. Accordingly, “[o]nce the statute of limitations has been tolled, it remains tolled for all members of the putative class until class certification is denied.” Id. at 354. If class certification is denied, the Court explained that “class members may [then] choose to file their own suits or to intervene as plaintiffs in the pending action.” Id.

The procedural history of China Agritech highlights the need for further development of American Pipe and Crown. On June 30, 2014, Michael Resh, an individual stockholder, filed a putative class action against China Agritech and several individual defendants, alleging that they violated federal securities laws by making material misstatements in the company’s SEC filings in 2008 and 2009. The complaint was based on the same facts and circumstances, and on behalf of the same would-be class, as two previously filed class actions that had been dismissed several months before. Of note, Resh filed the suit seventeen months after the relevant two-year statute of limitations would have expired absent tolling. The district court granted the defendants’ motion to dismiss on December 1, 2014, concluding that the rules in American Pipe and Crown would only toll the statute of limitations for Resh’s individual claims, and not for a subsequent class action. Resh v. China Agritech, 2014 WL 12599849, at *5 (C.D. Cal. Dec. 1, 2014). To hold otherwise, the district court opined, “would allow tolling to extend indefinitely as class action plaintiffs repeatedly attempt to demonstrate suitability for class certification on the basis of different expert testimony and/or other evidence.” Id.

On May 24, 2017, the Ninth Circuit reversed. Resh v. China Agritech, Inc., 857 F.3d 994 (9th Cir. 2017). The court held that American Pipe tolls the limitations period for otherwise untimely class actions and that a plaintiff who seeks to bring a new class action raising the same issues is barred only by “the criteria of Rule 23” and “comity [and] preclusion principles.” Resh, 857 F.3d at 1005.

China Agritech filed a petition for a writ of certiorari to the Supreme Court on September 21, 2017. It contended that the Ninth Circuit’s holding “cannot be reconciled with the principles animating American Pipe tolling and would lead to significant adverse policy consequences,” primarily that “the tolling period ends only when previously absent plaintiffs stop trying to certify new class actions.” Petition for Writ of Certiorari at 22. Such a rule, petitioner argued, would make it difficult to settle disputes in a timely manner, among other practical problems. See id. at 26. Petitioner also identified a three-way circuit split on the issue. It posited that the First, Second, Fifth, and Eleventh Circuits reject American Pipe tolling for subsequent class actions, while the Sixth, Seventh, and Ninth Circuits take the opposite position and extend American Pipe tolling to the limitations period for otherwise untimely class actions. Petitioner further noted that the Third and Eighth Circuits split the difference by allowing tolling for successive class actions in some circumstances but not when class certification was previously considered and denied. See id. at 11–18. The Resh plaintiffs filed their opposition brief on October 23, 2017, disputing the existence of a circuit split regarding American Pipe‘s application to subsequent class actions as well as petitioners’ contention that the Ninth Circuit’s opinion permits endless re-litigation of class certification determinations. See id. at 15–21.

As noted above, the Supreme Court granted certiorari in December 2017. We expect that the parties will submit their briefing to the Supreme Court in the Spring of 2018, with oral argument to follow in the coming months. We will continue to monitor this appeal and provide an update in our 2018 Mid-Year Securities Litigation Update.

Gibson Dunn represents the Chamber of Commerce and Retail Litigation Center as amici curiae supporting petitioner in this case.

D. Recent Developments in SEC Enforcement Litigation – Lucia and Digital Realty

The Supreme Court has also been active in cases relevant to both SEC enforcement and civil securities litigation.

On July 21, 2017, Raymond Lucia and Raymond Lucia Companies, Inc., filed a petition for a writ of certiorari to review the D.C. Circuit’s opinion that SEC administrative law judges (“ALJs”) are not officers of the United States within the meaning of the Appointments Clause and, therefore, do not need to be nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate. Lucia v. SEC, No. 17-130. Notably, the Tenth Circuit recently held the contrary in Bandimere v. SEC, 844 F.3d 1168 (10th Cir. 2016), which called into question the validity of many ALJs’ prior rulings. Moreover, while the SEC took the position in the courts of appeals that its ALJs were mere “employees,” the Solicitor General now takes the position in the Supreme Court that ALJs are “Officers.” The Supreme Court granted review on January 12, 2018, and will hear oral arguments in April. Gibson Dunn represents petitioners in this case.

Separately, on November 28, 2017, the Supreme Court heard oral argument in Digital Realty Trust, Inc. v. Somers, No. 16-1276. Digital Realty concerns whether the anti-retaliation provision for “whistle-blowers” in the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 extends to individuals who have not reported a violation of the securities laws to the SEC and thus fall outside the Act’s literal definition of a “whistle-blower.” We expect a decision by June 2018.

For further analysis of Lucia and Digital Realty, please see our 2017 Year-End Securities Enforcement Update.

III. Delaware Developments

A. Corwin Doctrine

In Corwin v. KKR Financial Holdings LLC, the Delaware Supreme Court held that the business judgment standard of review should be applied to transactions approved (and thereby ratified or “cleansed”) by a non-coerced, fully informed stockholder vote in the absence of a controlling stockholder. 125 A.3d 304 (Del. 2015). As discussed in our 2017 Mid-Year Update, the Court of Chancery declined to extend the Corwin doctrine under the circumstances in In re Massey Energy, Co. Derivative & Class Action Litigation, where plaintiffs filed Caremark claims to hold defendant directors personally liable for their roles in deliberately flouting mining safety laws and permitting a massive explosion that claimed the lives of twenty-nine miners. 160 A.3d 484, 507 (Del. Ch. 2017) (reasoning that Corwin was not meant to “exonerate[e] corporate fiduciaries for any and all of their actions or inactions preceding their decision to undertake a transaction for which stockholder approval is obtained”). In the second half of 2017, the Court of Chancery continued to apply the Corwin doctrine where fully informed, uncoerced stockholders approved an underlying transaction. E.g., van der Fluit v. Yates, 2017 WL 5953514, at *7–8 (Del. Ch. Nov. 30, 2017) (finding stockholders were not fully informed, and thus Corwin was not satisfied, where the company failed to disclose which of its representatives were involved at key stages of negotiations); Morrison v. Berry, 2017 WL 4317252, at *1 (Del. Ch. Sept. 28, 2017) (applying Corwin in “an exemplary case of the utility of the ratification doctrine”).

In one exceptional case, however, the Court of Chancery declined to extend the Corwin doctrine to books-and-records-requests under Section 220 of the Delaware General Corporation Law. Lavin v. West Corp., 2017 WL 6728702 (Del. Ch. Dec. 29, 2017). There, the plaintiff’s stated purpose for inspecting the company’s books and records was to “determine whether wrongdoing and mismanagement had taken place” in connection with the underlying merger, and “to investigate the independence and disinterestedness” of the selling company’s board. Id. at *1. The defendant company moved to dismiss the plaintiff’s complaint, arguing that the plaintiff failed to state a credible basis of wrongdoing against the company’s board because the company’s disinterested stockholders’ voluntary, fully informed vote “cleansed” any purported breaches of fiduciary duty by satisfying the Corwin doctrine. Id. But the Court of Chancery rejected this argument. Instead, the court held that “Corwin does not fit within the limited scope and purpose of a books and records action in this court,” and explained that “Delaware courts generally do not evaluate the viability of the demand based on the likelihood that the stockholder will succeed in a plenary action.” Id. at *9.

B. The Delaware Supreme Court Reaffirmed The Role Of Deal Price In Appraisal Litigation—But Stopped Short Of Establishing A Bright-Line Presumption

In our 2017 Mid-Year Update, we reported on a clear trend in Delaware appraisal litigation in which courts increasingly defer to deal prices following a robust sale process. Recently, the Delaware Supreme Court affirmed this trend in Dell, Inc. v. Magnetar Global Event Driven Master Fund Ltd., 2017 WL 6375829, at *1–2 (Del. Dec. 14, 2017). There, the Supreme Court reversed the Court of Chancery’s decision to accord the negotiated deal price no weight, concluding that, “[t]aken as a whole, the market-based indicators of value—both Dell’s stock price and deal price—have substantial probative value.” Id. at *25. In particular, the Supreme Court noted, “when the evidence of market efficiency, fair play, low barriers to entry, outreach to all logical buyers, and the chance for any topping bidder to have the support of [management’s] own votes is so compelling, then failure to give the resulting price heavy weight because the trial judge believes there was mispricing missed by all the [company] stockholders, analysts, and potential buyers abuses even the wide discretion afforded the Court of Chancery in these difficult cases.” Id. at *26.

Nonetheless, the Supreme Court also declined to adopt “a presumption that the deal price reflects fair value if certain preconditions are met, such as when the merger is the product of arm’s-length negotiation and a robust, non-conflicted market check, and where bidders had full information and few, if any, barriers to bid for the deal,” because the appraisal statute “require[s] that the Court of Chancery consider ‘all relevant factors'” in its analysis. Id. at *14 (quoting 8 Del. C. § 262(h)).

1. The Court of Chancery accorded deal price no weight

The Court of Chancery relied on three central premises in concluding deal price was “not the best evidence of [Dell’s] fair value” and assigning it no weight. Id. at *10. First, the court hypothesized that the bidding over Dell was anchored at an artificially low price due to a “valuation gap” between the company’s stock price and its intrinsic value resulting from “investor myopia” and fatigue from a recent company transformation. Id. at *16. Second, the court suggested that the deal price was below fair value because of the absence of pre-signing competition from a strategic buyer in the sale process. Id. at *16; see also In re Appraisal of Dell Inc., 2016 WL 3186538, at *28, *36 (Del. Ch. May 31, 2016). In particular, the court found that “[t]he factual record in this case demonstrates that the price negotiations during the pre-signing phase were driven by the financial sponsors’ willingness to pay based on their LBO pricing models, rather than the fair value of [Dell].” Id. at *30. Third, the court concluded that factors endemic to MBOs further eroded the deal price’s credibility. Dell, 2017 WL 6375829, at *16. In particular, the Court of Chancery identified structural issues that the Court found inhibited the effectiveness of the go-shop, including the size and complexity of Dell and that bidders considering a proposed MBO “rarely submit topping bids because they have no realistic pathway to success.” Id. at *23.

2. The Delaware Supreme Court held that deal price deserved heavy weight under the circumstances

On appeal, the Delaware Supreme Court held that “[t]here is no requirement that a company prove that the sale process is the most reliable evidence of its going concern value in order for the resulting deal price to be granted any weight,” id. at *25, and reversed the Court of Chancery “because the reasoning behind the trial court’s decision to give no weight to any market-based measure of fair value runs counter to its own factual findings.” Id. at *12.

In particular, the Supreme Court found that “[t]he three central premises that the Court of Chancery relied upon to assign no weight to the deal price were flawed.” Id. at *16. First, the Supreme Court found that the record “provides no rational, factual basis for … a ‘valuation gap.'” Id. at *17. According to the Supreme Court, “the record shows that Dell had a deep public float, was covered by over thirty equity analysts in 2012, boasted 145 market makers, was actively traded with over 5% of shares changing hands each week, and lacked a controlling stockholder.” Id. at *17 (internal citations omitted).

Second, the Supreme Court reaffirmed its prior holding that a buyer’s status as a financial sponsor is not rationally related to whether the deal price is fair (a “private equity carve out”) and rejected the lack of strategic bidders as a credible basis for disregarding deal price. Id. at *20. “Here,” the Supreme Court explained, “it is clear that Dell’s sale process bore many of the same objective indicia of reliability that we [previously] found persuasive enough to diminish the resonance of any private equity carve out or similar such theory….” Id. (citing DFC Global Corp. v. Muirfield Value Partners, 172 A.3d 346, —, 2017 WL 3261190, at *22–23 (Del. Aug. 1, 2017)). Other facts contradicting the trial court’s conclusion include that an independent committee armed with the power to say “no” persuaded the buyer to raise its bid six times, investment bankers canvassed 67 potential buyers—20 of which were strategic acquirers, and that “the go-shop’s overall design rais[ed] fewer structural barriers than the norm.” Id. at *20–21.

Third, the Supreme Court found that the case presented none of the three features “endemic to MBOs” that theoretically could have undermined the reliability of the deal price. Id. at *22. For example, the Supreme Court found that the structure of the go-shop provided rival financial bidders “a realistic pathway to succeeding if they desired,” and even the petitioner’s expert characterized the go-shop as “rais[ing] fewer structural barriers than the norm.” Id. at *23. As for the potential for a “winner’s curse,” competing bidders were permitted “to undertake extensive due diligence, diminishing the information asymmetry that might otherwise facilitate a winner’s curse,” and “[t]he trial court even concluded that the [c]ommittee appears to have addressed the problem of information asymmetry and the risk of the winner’s curse as best they could.” Id.

C. Caremark Claims

Generally, a Caremark claim seeks to hold directors personally accountable for damages to the company arising from a failure to properly monitor or oversee employee misconduct or violations of law. The Delaware Supreme Court recently affirmed dismissal of a complaint for failure to adequately plead a Caremark claim in City of Birmingham Retirement & Relief System v. Good, 2017 WL 6397490 (Del. Dec. 15, 2017) (“Duke Energy“).

The Duke Energy plaintiffs asserted that they were not required to make a demand on Duke Energy’s board prior to instituting litigation because the board’s management of the company’s environmental policies amounted to a Caremark violation when a ruptured storm pipe caused twenty-seven million gallons of coal ash slurry and wastewater to spill into the Dan River—ultimately leading the company to plead guilty to nine misdemeanor violations of the Federal Clean Water Act and pay a $102 million fine. The Court of Chancery, however, dismissed the plaintiffs’ derivative complaint, holding that “to hold directors personally liable for a Caremark violation, the plaintiffs must allege that the directors intentionally disregarded their oversight responsibilities such that their dereliction of fiduciary duty rose to the level of bad faith,” and “reports from management relied on by the board to address coal ash storage problems negated any reasonable pleading-stage inference of bad faith conduct by the board.” Id. at *1.

The Delaware Supreme Court agreed, emphasizing that “plaintiff[s] must allege with particularity that the directors acted with scienter, meaning ‘they had actual or constructive knowledge that their conduct was legally improper,'” and that “[i]nferences that are not objectively reasonable cannot be drawn in the plaintiff[s’] favor.” Id. at *5 (internal citations and quotations omitted). The Court rejected plaintiffs’ description of the information presented to the Board as unfair, concluding that a fair characterization of management’s board presentations “do[es] not lead to the inference that the board consciously disregarded its oversight responsibility by ignoring environmental concerns.” Id. at *8. The Court also rejected as inadequate plaintiffs’ allegations that Duke Energy illegally colluded with a corrupt regulator, noting that “general allegations regarding a regulator’s business-friendly policies are insufficient to lead to an inference that the board knew Duke Energy was colluding with a corrupt regulator.” Id. at *11.

D. Ratification Defense Limited In Executive Compensation Context

Considering stockholder ratification of director self-compensation decisions for the first time in more than fifty years, in In re Investors Bancorp, Inc. Stockholder Litigation, the Delaware Supreme Court limited the ratification defense when directors make equity awards to themselves under the general parameters of an equity incentive plan. 2017 WL 6374741, at *1 (Del. Dec. 13, 2017). Absent stockholder approval, directors must prove that, when challenged by stockholders, equity incentive awards they grant to themselves are entirely fair to the company. Similar to the Corwin doctrine, when a majority of fully informed, uncoerced, and disinterested stockholders approve a challenged equity incentive award that directors granted to themselves, the ordinary entire fairness standard of review shifts to business judgment review. Before Investors Bancorp, this was generally true with respect to equity incentive plans with fixed terms and discretionary terms, like those at issue in Investors Bancorp, id. at *11, so long as discretionary terms have “meaningful limits” on the awards directors can make to themselves.

In Investors Bancorp, however, the Supreme Court extended Sample v. Morgan, 914 A.2d 647 (Del. Ch. 2007), which “underline[d] the need for continued equitable review of self-interested discretionary director self-compensation decisions,” Investors Bancorp, 2017 WL 6374741, at *11. In this case, the plaintiffs alleged stockholders were told initially that the plan would reward future performance, but that the board instead granted themselves awards to reward past efforts. Id. at *12. Additionally, the rewards were purportedly unusually higher than peer companies’. Id. The Supreme Court found that “[t]he plaintiffs have alleged facts leading to a pleading stage reasonable inference that the directors breached their fiduciary duties,” and “[b]ecause the stockholders did not ratify the specific awards the directors made under the [plan], the directors [were required to] demonstrate the fairness of the awards to the [c]ompany.” Id. at *13.

E. Delaware Supreme Court Rules On The Application Of Collateral Estoppel To Prior Judgments Of Demand Futility

On January 25, 2018, the Delaware Supreme Court in California State Teachers Retirement System v. Alvarez unanimously affirmed a previous Court of Chancery decision by Chancellor Andre Bouchard that stockholders who were pursuing derivative claims were collaterally estopped from continuing because, in a parallel case, a federal court in Arkansas had held that demand was not futile. As discussed in our 2016 Year-End Securities Litigation Update, the Delaware Court of Chancery had then recently been exploring the contours of the application of collateral estoppel to prior judgments of demand futility. Among these decisions was the decision by Chancellor Bouchard, granting the Defendants’ Motion to Dismiss in this case, that applied the Delaware Supreme Court’s decision in Pyott v. Lampers, 74 A.3d 612, 618 (Del. 2013), to hold that a federal stockholder derivative plaintiff’s election not to use books and records procedures under Section 220 of Delaware’s General Corporation Law did not bar the application of preclusion doctrines in subsequent stockholder derivative suits.

After initial briefing and a hearing on appeal, the Delaware Supreme Court remanded to the Court of Chancery for the limited purpose of further discussing potential Due Process issues raised by the dismissal on the grounds of collateral estoppel. Reconsidering his prior ruling, Chancellor Bouchard’s supplemental opinion recommended that the Delaware Supreme Court adopt a rule proposed, in dictum, in In re EZCORP, Inc. Consulting Agreement Derivative Litigation, 130 A.3d 934, 948 (Del. Ch. 2016). Under the EZCORP rule, a judgment could not bind “the corporation or other stockholders in a derivative action until the action has survived a Rule 23.1 motion to dismiss, or the board of directors has given the plaintiff authority to proceed by declining to oppose the suit.” Id.

On return from remand, the Delaware Supreme Court declined to adopt the EZCORP rule, aligning instead with federal courts that “each arrived at the same conclusion: the Due Process rights of subsequent derivative plaintiffs are protected, and dismissal based on issue preclusion is appropriate, when their interests were aligned with and were adequately represented by the prior plaintiffs.” California State Teachers Retirement System v. Alvarez, No. 295, 2016, 2018 WL 547768 at *11 (Del. Jan. 25, 2018). Further, “the ‘dual’ nature of a derivative action does not transform a stockholder’s standing to sue on behalf of the corporation into an individual claim belonging to the stockholder,” because “[t]he named plaintiff, at this stage, only has standing to seek to bring an action by and in the right of the corporation and never has an individual cause of action.” Id. at *16. This “highlights a fundamental distinction from class actions, where the named plaintiff initially asserts an individual claim and only acts in a representative capacity after the court certifies that the requirements for class certification are met.” Id.

The Delaware Supreme Court also found—applying Arkansas law and noting that federal decisions on privity in derivative actions come to the same conclusion—that privity applies between different groups of stockholder derivative plaintiffs. Id. at *15-18. Thus “the evaluation of the adequacy of the prior representation becomes the primary protection for the Due Process rights of subsequent derivative plaintiffs.” Id. at *19.

The court went on to find that the Arkansas Plaintiffs’ representation was adequate because (1) the interests of the plaintiffs were aligned, (2) both groups of plaintiffs recognized that a judgment in their case could impact the other stockholders and thus the derivative plaintiffs understood they were acting in a representative capacity, and (3) it was undisputed that Delaware Plaintiffs had notice of the Arkansas action (although the court noted it did not need to resolve whether such notice was required). Id. at *19-20. The court also reasoned that representation was adequate under the framework of the Restatement, because the Arkansas Plaintiffs were not grossly deficient in their representation and their economic interests were not antagonistic to other stockholders. Id. at *20-21. The Delaware Supreme Court agreed with the previous decision of the Court of Chancery that the Arkansas Plaintiffs’ failure to seek books and records did not make them grossly deficient. Id. at *21.

The court emphasized that “our state’s interest in governing the internal affairs of Delaware corporations must yield to the ‘stronger national interests that all state and federal courts have in respecting each other’s judgments'”—and concluded that adopting the EZCORP rule would impair this “delicate balance.” Id. at *23.

IV. State Securities Suits and the PSLRA – Status of State Securities Act Class Action Filings in Light of Cyan

As reported above, the United States Supreme Court’s decision in Cyan may have a transformational impact on Securities Act class actions filed in state courts. Unsurprisingly, this pending sea change has brought uncertainty to the bar and courts. But anecdotal evidence suggests that the status quo has remained in place pending the Court’s decision. Plaintiffs have continued to file securities class actions in state courts that are historically hospitable to such suits—though there is evidence the pace has slowed. Defendants, in light of Cyan, seem more eager to try their luck at removal, even when such efforts have been historically unsuccessful. And, consistent with prior rulings on this jurisdictional issue, federal courts—especially those in California—have generally found in favor of state court jurisdiction and refused to stay cases pending the decision in Cyan.

Though full-year 2017 data has not yet been compiled, it appears that, at least in California, the pace of Securities Act class actions filed in state court has slowed somewhat. As we reported in the Mid-Year Update, since 2011, Securities Act Section 11 filings skyrocketed in California after a California Court of Appeal held that states have concurrent jurisdiction over Securities Act class actions. See Luther v. Countrywide Fin. Corp., 195 Cal.App.4th 789 (2011). As the Cyan petitioners noted, between 1998 and 2011, only six class actions alleging violations of Section 11 were filed in California state court. See Petitioners’ Br. at 8 n. 6. By contrast, 14 were filed in 2015 alone. Id. And in 2016, 18 were filed. However, “[i]n the first half of 2017, there were four [such] cases brought in California state courts, distinctly fewer than observed in either the first or second halves of 2016.” See Cornerstone Research, Securities Class Actions Filings – 2017 Midyear Assessment at 4 (2017). The Cyan respondents argue that this is a return to the norm after the 2016 aberration. See Resp. Supp. Br. at 1.

Defendants in these suits in California have attempted to use the pending Cyan decision as an opportunity to again try their luck at removal—without much success. In multiple California cases, defendants sought to remove state-filed securities class actions to federal court, where they then sought an order of a stay pending the Cyan decision. See, e.g., Guo v. ZTO Express (Cayman) Inc., Case No. 17-cv-05357-JST, Dkt. No. 41 (N.D. Cal. Dec. 22, 2017); Seafarers Officers & Empls. Pension Plan v. Apigee Corp., Case No. 17-cv-04106-JD, Dkt. No. 16 (N.D. Cal. Sep. 1, 2017); Bucks Cty. Empls. Ret. Fund v. NantHealth, Inc., No. 2:17-cv-03964-SVW-SS, 2017 WL 3579889, at *2 (C.D. Cal. Aug. 18, 2017); Olberding v. Avinger, Inc., No. 17-CV-03398-CW, 2017 WL 3141889, at *3 (N.D. Cal. July 21, 2017); Book v. ProNAi Therapeutics, Inc., No. 5:16-CV-07408-EJD, 2017 WL 2533664, at *1 (N.D. Cal. June 12, 2017). In each case, the district court denied defendants’ request. These courts cited the unanimity in the Ninth Circuit that such cases should be remanded and found that there was no basis for a stay pending the decision in Cyan. See, e.g., Seafarers Officers, Case No. 17-cv-04106-JD, Dkt. No. 16.

Though California has dominated the scene when it comes to these filings, federal courts in other states confronting this issue in 2017 have generally come to the same conclusion. See e.g., Christians v. KemPharm, Inc., 265 F. Supp. 3d 971, 984 (S.D. Iowa 2017). However, one court did break from the majority and granted a stay pending the outcome in Cyan. See City of Birmingham Ret. & Relief Sys. v. ZTO Express (Cayman), Inc., No. 2:17-CV-1091-RDP, 2017 WL 3750660 (N.D. Ala. Aug. 29, 2017). Though that court acknowledged that “most of the district courts in the First, Seventh, Ninth, and Eleventh circuits have remanded [similar] cases back to state court,” it nonetheless denied the motion to remand without prejudice and granted a stay. Id. at *1. Notably, the City of Birmingham court did not expound on its reasoning, other than to say that “it is prudent to await the Supreme Court’s guidance” in Cyan.

A decision in Cyan is expected in June 2018. We will report back on the impact of this decision in our 2018 Mid-Year or Year-End Securities Litigation Update.

V. Leidos. Scope of Item 303 Liability Remains Uncertain After Settlement Forestalls Supreme Court’s Consideration of Issue

As noted in Section II(A) above, in light of a settlement reached between the parties in the closely watched Leidos case, the Supreme Court announced in October that it would not address an important question of federal securities law: whether omitting information required to be disclosed under Item 303 of SEC Regulation S-K, which governs the contents of the Management’s Discussion & Analysis section of a company’s quarterly and annual reports, gives rise to a private claim for securities fraud under Section 10(b) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and Rule 10b-5.

The Supreme Court’s anticipated visitation of this question was significant, as it would have resolved a circuit split over the extent of a company’s Section 10(b) liability premised on violations of Item 303. The Supreme Court has long held that “[s]ilence, absent a duty to disclose, is not misleading under Rule 10b–5.” Basic, Inc. v. Levinson, 485 U.S. 224, 239 n.17 (1988) (internal quotation marks omitted). Indeed, the Supreme Court has held that a duty to disclose under Section 10(b) and Rule 10b–5 arises only when an omission would render an affirmative statement misleading or would violate a special duty founded in a relationship of trust and confidence; thus, companies can “control what they have to disclose . . . by controlling what they say to the market.”

Against this backdrop, the Second Circuit nevertheless held in Indiana Public Retirement System v. SAIC, Inc. (“SAIC“) that an omission under Item 303 can give rise to Section 10(b) and Rule 10b–5 liability. 818 F.3d 85, 94–95 (2d Cir. 2016). The plaintiffs in SAIC had brought claims in the Southern District of New York under various securities laws, including Section 10(b), alleging that Leidos’s predecessor, SAIC, Inc., made material omissions by failing to disclose federal and state investigations into the company’s unlawful overbilling practices in connection with a government contract with the City of New York. Id. at 88. Plaintiffs charged that SAIC should have disclosed this allegedly known and potentially significant exposure in its March 2011 Form 10-K because Item 303 requires that such disclosures “[d]escribe any known trends or uncertainties that have had or that the registrant reasonably expects will have a material favorable or unfavorable impact on net sales or revenues or income from continuing operations,” 17 C.F.R. § 229.303(a)(3)(ii). Id.

The district court dismissed this claim for failure to plead facts establishing that “management (1) had knowledge that the company could be implicated in the . . . fraud or (2) could have predicted a material impact on the company.” In re SAIC, Inc. Securities Litigation, 2014 WL 407050, at *4 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 30, 2014). Thus, while not disagreeing with the proposition that an Item 303 omission could be actionable under Section 10(b) and Rule 10b–5, the district court found insufficient allegations that SAIC had a disclosure obligation under Item 303 with the facts as pled.

On appeal, the Second Circuit vacated the portion of the district court’s ruling related to Item 303 and remanded it for further proceedings. SAIC, 818 F.3d at 88. The Second Circuit agreed that Item 303 requires the registrant to disclose only those trends, events, or uncertainties that it “actually knows of”—as opposed to those that it “should have known”—when it files with the SEC, but it concluded that SAIC was allegedly “aware of the fraud” at the time of the report. Id. at 94.

The Second Circuit’s decision in SAIC on the Item 303 issue placed it in conflict with earlier-issued decisions by the Ninth and Third Circuits, which held that violations of Item 303 are not actionable under Section 10(b) and Rule 10b–5. In 2014, the Ninth Circuit in In re NVIDIA Corp. Sec. Litig. held that “Item 303 does not create a duty to disclose for purposes of Section 10(b) and Rule 10b–5.” 768 F.3d 1056 (9th Cir. 2014). In so holding, the Ninth Circuit relied on a Third Circuit decision authored in 2000 by then-Circuit Judge Samuel Alito, Oran v. Stafford, where the Third Circuit declared that “a violation of the disclosure requirements of Item 303 does not lead inevitably to the conclusion that such disclosure would be required under Rule 10b–5,” and, accordingly, “that a violation of SK-303’s reporting requirements does not automatically give rise to a material omission under Rule 10b-5.” 226 F.3d 275, 287–88 (3d Cir. 2000).

This circuit split between the Second Circuit on the one hand, and the Ninth and Third Circuits on the other, teed up the issue for resolution by the Supreme Court, which granted certiorari in Leidos on March 27, 2017, and had set oral argument for November 6, 2017. But exactly one month prior to the scheduled arguments, on October 6, 2017, the parties filed a joint motion advising the Court that they had “reached an agreement in principle to settle” the dispute. On October 17, 2017, the Supreme Court granted the parties’ motion, and ordered that same day that the case be removed from the November 6, 2017 argument calendar.

With Leidos no longer before the Supreme Court, the Second-Ninth Circuit split over the scope of Item 303 liability remains. As things currently stand, Leidos continues to control in the Second Circuit, while In re NVIDIA Corp. Sec. Litig. still controls in the Ninth Circuit. This lingering divide, according to some legal commentary, will have important implications for litigants, for the courts themselves, and for companies seeking to avoid Item 303 liability going forward.

For one, in light of the Leidos decision, which effectively endorsed a private right of action under Section 10(b) for violations of Item 303, plaintiffs will likely continue to flock to the Second Circuit to litigate securities fraud claims premised on Item 303 deficiencies. Conversely, the Ninth Circuit, which has shown itself to be far less amenable to such claims, will likely see far fewer shareholders bring their claims in that court.

Furthermore, because the Second and Ninth Circuits together handle more federal securities cases than the rest of the circuits combined, the existing circuit split may well create a deepening fissure among those two circuits. And other courts that have yet to take up the issue will likely follow either one of the Second or Ninth Circuits’ approaches, leading to a further divergent development of caselaw. In addition to looking to Second and Ninth Circuit authority, these as-yet-decided courts may also choose to take note of the amicus brief filed by the SEC in Leidos, which was consistent with the Second Circuit’s ultimate holding in that case. Specifically, the Commission asserted in its brief, “[a] reasonable investor, reading an MD&A in the applicable legal context, understands it to contain all the information required by Item 303. An MD&A that discloses only some of the information Item 303 requires therefore is misleading.”

The Leidos settlement, and the circuit split that remains in its wake, may also have important implications for companies trying to ascertain the scope of their disclosure obligations under Item 303. Until the Supreme Court weighs in on this issue, uncertainty is likely to abound for companies over, what, exactly, are considered to be “known trends and uncertainties,” among other relevant issues. Accordingly, in an effort to stave off legal challenges further down the road, companies susceptible to jurisdiction in the Second Circuit may choose to over-disclose.

Despite the present uncertainty, the Supreme Court will certainly be petitioned again upon the next circuit court decision on the matter. (Indeed, regardless of whether the next decision is plaintiff- or defendant-friendly, the issue will be ripe for appeal given the existing circuit split.) One candidate to reignite a Supreme Court resolution is Plumbers and Steamfitters Local 137 Pension Fund v. Am. Express Co., 2017 WL 4403314 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 30, 2017). In Plumbers, a group of purchasers of American Express’s common stock brought a putative class action against American Express, asserting claims under Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5 in connection with American Express’s non-renewal of its co-brand agreement with Costco (an agreement under which the two companies had partnered to offer co-branded cards for consumers and small businesses). Plaintiffs alleged, in relevant part, that American Express violated its duty to quantify and disclose “the expected impact of known trends and uncertainties in Amex’s business,” in violation of Item 303. Plumbers, WL 4403314, at *17. Specifically, plaintiffs argued that American Express failed to disclose 1) the expected impact that increased competition with respect to obtaining co-branded agreements would have on American Express’s business, and 2) its uncertainty regarding renewal of its agreement with Costco, as well as the impact of nonrenewal of the agreement—omissions that, plaintiffs asserted, gave rise to Section 10(b) liability. Id. The district court disagreed. In dismissing plaintiffs’ complaint, it noted that American Express had complied with Item 303 by sufficiently disclosing the trend at issue (“[w]e also face substantial and increasingly intense competition for partner relationships”), and how that negative trend could affect its business (“we could lose partner relationships”). Id. at *19. Accordingly, the court concluded, American Express had met its disclosure obligations and did not omit required quantitative information under Item 303, thus precluding Section 10(b) liability on that basis. Id. Plaintiffs subsequently appealed the decision to the Second Circuit.

If the Second Circuit reverses the district court’s finding that American Express met its Item 303 disclosure obligations, the matter could again be teed up for resolution by the Supreme Court. Gibson Dunn will continue to monitor for developments in connection with this topic.

VI. Falsity of Opinions – Omnicare Update

Federal courts continue to put flesh onto the bones of the Supreme Court’s 2015 decision in Omnicare, Inc. v. Laborers Dist. Council Constr. Indus. Pension Fund, 135 S. Ct. 1318 (2015). That decision addressed the scope of liability for false opinion statements under Section 11 of the Securities Act. The Court held that “a sincere statement of pure opinion is not an ‘untrue statement of material fact,’ regardless of whether an investor can ultimately prove the belief wrong.” 135 S. Ct. at 1327. An opinion statement can give rise to liability only when the speaker does not “actually hold[] the stated belief,” or when the opinion statement contains “embedded statements of fact” that are untrue. Id. at 1326–27. In addition, the Court held that an omission gives rise to liability when the omitted facts “conflict with what a reasonable investor would take from the statement itself.” Id. at 1329. Put differently, an opinion statement becomes misleading “if the real facts are otherwise, but not provided.” Id. at 1328.

In the second half of 2017, two courts issued notable opinions regarding the threshold question of what constitutes a statement of opinion under Omnicare. First, the Ninth Circuit held that the statement “FDA clearance risk has been achieved” – made on behalf of drug company Atossa Genetics regarding certain drug tests – is a statement of opinion. See In re Atossa Genetics Inc. Sec. Litig., 868 F.3d 784, 801 (9th Cir. 2017). The court reasoned that whether FDA clearance risk has been “achieved” is not definite enough to be a statement of fact, as this could mean that FDA clearance risk is completely eliminated or just that an acceptable level of risk has been eliminated; “[i]ndeed, it is the speaker’s personal definition of ‘achieved’ that here produces the opinion.” See id.

In what is sure to be a controversial decision, the court in Bielousov v. GoPro Inc., No. 16-cv-06654-CW, 2017 WL 3168522, at *4–5 (N.D. Cal. July 26, 2017), decided that a statement that seemingly met the requirements of the PSLRA’s safe harbor for forward-looking statements was nonetheless an actionable statement of opinion. One of the statements challenged by plaintiff was the CFO’s statement that “we believe” that GoPro was “on track” to meet its previously-issued revenue guidance. See id. at *4. Although defendants argued this was a forward-looking statement protected by the safe harbor, the court held that by including the phrase “we believe” the CFO “was representing his and GoPro’s existing state of mind” which is “a statement of present opinion . . . not covered by the PSLRA safe harbor provision.” See id. at *5. Taken to its logical conclusion, the GoPro court’s reasoning would turn most statements previously considered forward-looking in nature into actionable statements of opinion. While this appears to be an outlier opinion, we will monitor further developments in this area of securities law.

Numerous recent opinions showcase the difficulty of pleading the falsity of opinion statements after Omnicare. In Markette v. XOMA Corp., No. 15-CV-03425-HSG, 2017 WL 4310759, at *5 (N.D. Cal. Sept. 28, 2017), the court held that conclusory allegations that defendants did not believe in their opinion statements are insufficient to plead falsity. While the court did not analyze this issue in depth, the court implicitly reasoned that a plaintiff must allege specific facts showing that a defendant did not believe in his stated opinion in order for plaintiff’s claim to survive a motion to dismiss. In Wilbush v. Ambac Fin. Grp., Inc., the court reaffirmed the principle that plaintiffs cannot state a claim by pleading “fraud by hindsight” – that is, a plaintiff cannot show that an opinion was false when made solely by pointing to subsequent developments that are inconsistent with that opinion. See No. 16 Civ. 5076-RMB, 2017 WL 4125364, at *10 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 5, 2017) (opinion about adequacy of loss reserves for investments not false solely because company ultimately suffered losses on investments). Finally, the court in Jaroslawicz v. M&T Bank Corp., No. 15-897-RGA, 2017 WL 4856864 (D. Del. Oct. 27, 2017), highlighted what plaintiffs need to allege to plead an actionable omission of “material facts about the issuer’s inquiry into or knowledge concerning a statement of opinion.” See Omnicare, 135 S. Ct. at 1329. In this Section 14(a) case, the court rejected as insufficient “hypotheticals” about what defendants could have done to make an inquiry before rendering an opinion about the company’s compliance with banking laws, holding that plaintiffs needed to instead plead “particular facts about what Defendants did or did not do in forming the compliance opinion” at issue. See 2017 WL 4856864 at *6 (dismissing allegations that opinion about legal compliance would have been shown to be false if defendants performed “adequate due diligence” or hired a “trained, independent consultant”).

Of course, if plaintiffs can plead specific facts as to the falsity of an opinion statement, courts are willing to allow plaintiffs’ cases to proceed. In the Atossa Genetics case, for example, the Ninth Circuit held that plaintiffs sufficiently pleaded the opinion that “FDA clearance risk has been achieved” was misleading by omission because they alleged (i) only part of the multi-part drug test at issue had been approved by the FDA, and (ii) the FDA had expressed concerns to Atossa about this lack of complete clearance. See 868 F.3d at 802. These facts, the court held, “relate directly to the basis for” the opinion statement, and “conflict with what a reasonable investor would take away from the statement.” Id. And in Perez v. Higher One Holdings, Inc., No. 3:14-cv-755-AWT, 2017 WL 4246775, at *6 (D. Conn. Sept. 25, 2017), the court – after dismissing plaintiffs’ previous complaint with leave to amend – denied a motion to dismiss the amended complaint as to an opinion that Higher One Holdings does “not expect any further losses as a result of” an FDIC investigation that led to a consent order in 2012. Because the amended complaint alleged specific facts showing that defendants were violating the 2012 consent order and were specifically warned “about their ongoing violative conduct,” the court held that plaintiffs sufficiently pleaded falsity because “defendants could not have reasonably believed their own statements of corporate optimism.” See id.

As reported in previous updates, we continue to see courts applying Omnicare outside of the Section 11 context. Most of the foregoing decisions arose out of complaints alleging violations of Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act, which continues a trend we highlighted in previous updates. Additionally, courts are applying Omnicare in actions asserting claims under a variety of other securities laws. See Jaroslawicz v. M&T Bank Corp., 2017 WL 4856864 (Section 14(a) of the Exchange Act); Knurr v. Orbital ARK, Inc., No. 1:16-cv-1031, 2017 WL 4286273 (E.D. Va. Sept. 26, 2017) (Section 14(a) of the Exchange Act); Fed. Hous. Fin. Agency v. Nomura Holding Am., Inc., 873 F.3d 85 (2d Cir. 2017) (Section 12(a) of the Securities Act). And, in a natural extension of Omnicare, given its roots in disclosure-based law, the court in Hutton v. McDaniel, 264 F. Supp. 3d 996, 1021 (D. Ariz. 2017), applied Omnicare to a state law breach of fiduciary duty claim arising out of directors’ alleged failure to disclose information to shareholders.

VII. Halliburton II Market Efficiency and Price Impact Cases

As discussed in our 2017 Mid-Year Update, courts across the country continue to grapple with implementing the Supreme Court’s landmark ruling in Halliburton Co. v. Erica P. John Fund, Inc., 134 S. Ct. 2398 (2014) (Halliburton II), and several recent decisions are beginning to shape the post-Halliburton II landscape. In Halliburton II, the Supreme Court preserved the “fraud-on-the-market” presumption—a presumption enabling plaintiffs to maintain the common proof of reliance that is essential to class certification in a Rule 10b-5 case—but made room for defendants to rebut that presumption at the class certification stage with evidence that the alleged misrepresentation had no impact on the price of the issuer’s stock. Two key questions continue to recur: first, how should courts reconcile the Supreme Court’s explicit ruling in Halliburton II that direct and indirect evidence of price impact must be considered at the class certification stage, Halliburton II, 123 S. Ct. at 2417, with its previous decisions holding that plaintiffs need not prove loss causation or materiality until the merits stage, see Erica P. John Fund, Inc. v. Halliburton Co., 563 U.S. 804 (2011) (“Halliburton I“); Amgen Inc. v. Conn. Ret. Plans & Trust Funds, 133 S. Ct. 1184 (2013). And second, what standard of proof must defendants meet to rebut the Basic presumption with evidence of no price impact?

As discussed in our January 18, 2018 Client Alert, the Second Circuit recently addressed both of these issues in two substantive opinions: Waggoner v. Barclays, 875 F.3d 79 (2d Cir. 2017) and Ark. Teachers Ret. Sys. v. Goldman Sachs, — F.3d –, Case No. 16-250, 2018 WL 385215 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 12, 2018). In so doing, the Second Circuit joined the Eighth Circuit as the only federal circuit courts of appeals to interpret Halliburton II since it was issued. In Goldman Sachs, the Second Circuit directed that price impact evidence must be analyzed prior to certifying a class, even though “price impact touches on materiality,” which is to be reserved for trial. Goldman Sachs, 2018 WL 385215, at *7-8. However, the Barclays and Goldman Sachs decisions leave the Second Circuit at odds with the Eighth Circuit’s 2016 decision in IBEW Local 98 Pension Fund v. Best Buy Co., 818 F.3d 775 (8th Cir. 2016) on the standard of proof defendants must meet to rebut the Basic presumption.

A. Evidence Properly Considered at the Class Certification Stage

In Goldman Sachs the Second Circuit vacated the district court’s order certifying a class, and remanded for further proceedings to determine whether the defendants had presented sufficient evidence to demonstrate that the alleged misstatements did not impact Goldman Sachs’ stock price. The Second Circuit encouraged the district court to hold any evidentiary hearing or oral argument it finds appropriate to address the issue on remand.

In the district court, defendants attempted to rebut the presumption of reliance by presenting evidence that the statements at issue had no impact on Goldman Sachs’ stock price. They offered evidence that (1) the stock price did not increase on the days when the alleged misstatements were made and (2) the stock price did not decrease when those statements were “corrected” by news that was publicly revealed on thirty-four separate occasions before the alleged corrective disclosure dates. Goldman Sachs, 2018 WL 385215 at *7. If the prior disclosures “correcting” the alleged misstatements did not negatively impact the company’s stock price, defendants reasoned, then the alleged misstatements themselves “did not affect the price of Goldman stock and plaintiffs could not have relied on them in choosing to buy shares at that price.” Id. at *4. The district court rejected defendants’ evidence regarding the lack of price impact based on these earlier “corrective” press reports, labeling the argument a premature “materiality” argument.

The Second Circuit acknowledged that price impact “touches on materiality,” but nonetheless instructed the trial court, on remand, to consider defendants’ price impact evidence. Goldman Sachs, 2018 WL 385215 at *8. The court explained that price impact and materiality are distinct, and that price impact “refers to the effect of a misrepresentation on a stock price.” Id. (quoting Halliburton I, 563 U.S. at 814). “Whether a misrepresentation was reflected in the market price at the time of the transaction—whether it had price impact—” the court explained, “‘is Basic‘s fundamental premise.'” Id. (quoting Halliburton II, 134 S. Ct. at 2416). Therefore, a defendant’s evidence of a lack of price impact must be fully considered at the class certification stage. Id.

B. Standard of Proof to Rebut the Presumption

In Barclays, the Second Circuit’s only substantive Halliburton II discussion addressed the standard of proof required to rebut the presumption of reliance. There, the court upheld the district court’s certification of a class, holding that once a plaintiff establishes that the presumption applies, the defendant bears the burden of persuasion to rebut it. This standard, reaffirmed in Goldman Sachs, puts the Second Circuit at odds with the Eighth Circuit, which cited Rule 301 of the Federal Rules of Evidence (“Rule 301”) when reversing that trial court’s certification order. Best Buy, 818 F.3d at 782. Rule 301 assigns only the burden of production—i.e., producing some evidence—to the party seeking to rebut a presumption, but “does not shift the burden of persuasion, which remains on the party who had it originally.” By its own terms, Rule 301 applies in all civil cases “unless a federal statute or these rules provide otherwise.” In both Barclays and Goldman Sachs, the Second Circuit panels reasoned that “the Basic presumption is a substantive doctrine of federal law that derives from the securities fraud statutes” in departing from the standard burden-shifting paradigm of Rule 301. Goldman Sachs, 2018 WL 385215, at *6-7 (citing Barclays, 875 F.3d at 102–03).

We will continue to monitor the Goldman Sachs remand and cases in all courts throughout the year.

The following Gibson Dunn lawyers assisted in the preparation of this client update: Monica Loseman, Matt Kahn, Brian Lutz, Laura O’Boyle, Mark Perry, Lissa Percopo, Travis Andrews, Jefferson Bell, Scott Campbell, Vivek Gopalan, Michael Kahn, Kim Kirschenbaum, Mark Mixon, Emily Riff, Samantha Weiss, Christopher White and Zachary Wood.

Gibson Dunn lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these developments. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, or any of the following members of the Securities Litigation Practice Group Steering Committee:

Robert F. Serio – Co-Chair, New York (+1 212-351-3917, [email protected])

Meryl L. Young – Co-Chair, Orange County (+1 949-451-4229, [email protected])

Brian M. Lutz – Co-Chair, San Francisco/New York (+1 415-393-8379/+1 212-351-3881, [email protected])

Thad A. Davis – San Francisco (+1 415-393-8251, [email protected])

Jennifer L. Conn – New York (+1 212-351-4086, [email protected])

Ethan Dettmer – San Francisco (+1 415-393-8292, [email protected])

Barry R. Goldsmith – New York (+1 212-351-2440, [email protected])

Mark A. Kirsch – New York (+1 212-351-2662, [email protected])

Gabrielle Levin – New York (+1 212-351-3901, [email protected])

Monica K. Loseman – Denver (+1 303-298-5784, [email protected])

Jason J. Mendro – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3726, [email protected])

Alex Mircheff – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7307, [email protected])

Robert C. Walters – Dallas (+1 214-698-3114, [email protected])

Aric H. Wu – New York (+1 212-351-3820, [email protected])

© 2018 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.