January 9, 2019

One hundred and fifty-five years after Congress enacted the False Claims Act (FCA), it remains the government’s primary tool to combat fraud with respect to government programs, a source of noteworthy Supreme Court jurisprudence, and a window into the government’s enforcement priorities and policy efforts. Especially during the last decade, few areas of law have generated so much attention among the courts, and so much in damages and penalties paid to the government by private industry. This year was no exception.

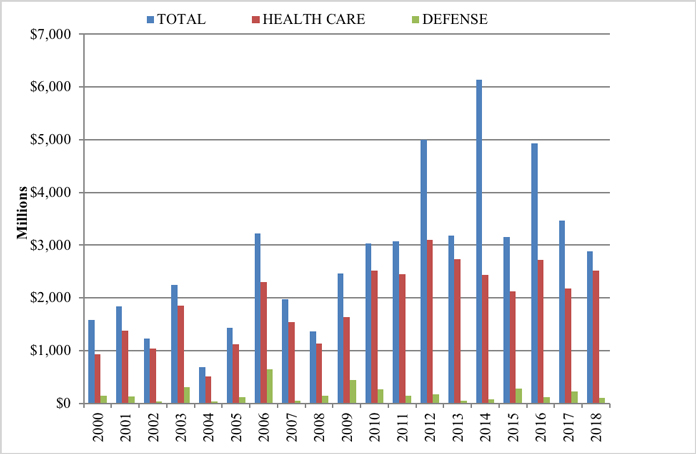

In fiscal year 2018, the Department of Justice (DOJ) recovered almost $2.9 billion from companies that do business with the government. This total marks a slight downturn from recent years, but is still one of the top ten totals of all time (all ten of which have occurred since 2006). There were also more than 760 new FCA matters initiated during 2018, marking the ninth year in a row that companies were hit with more than 700 new matters. By all measures, therefore, the breakneck pace of FCA investigations and litigation set during the last decade is not slowing.

It is perhaps no surprise then, that key legal questions underpinning FCA litigation also continued to garner significant attention from the federal courts. For their part, the lower courts continued to deal with a wide range of thorny legal issues, including threshold jurisdictional issues, pleading requirements under the FCA, and standards of liability and proof under the Supreme Court’s seminal 2016 decision in Universal Health Services, Inc. v. United States ex rel. Escobar, 136 S. Ct. 1989 (2016). The Supreme Court, meanwhile, agreed to hear an important case concerning the statute of limitations in whistleblower suits brought under the FCA, marking the fourth time in as many years that the Supreme Court has opted to interpret the FCA (and the eighth time in the last decade).[1]

Not to be outdone by developments on the enforcement and case law fronts, there were also several important legislative and policy developments. Most notably, DOJ leadership announced significant policy changes in the first half of 2018 that guide how and when the government will pursue FCA actions. And in the second half of 2018, even though they are still in their early stages, we started to see those changes put into effect. Indeed, DOJ sought to pull the plug on a dozen FCA cases.

We address all of these and other developments in greater depth below. We first provide an overview of enforcement activity at the federal and state levels during fiscal year 2018 and summarize the most notable FCA settlements that were announced in the second half of 2018 (settlements from the first half of the year were covered in our 2018 Mid-Year Update). We turn next to the noteworthy developments on the legislative and policy fronts, and then conclude with an analysis of significant cases from the past six months.

As always, Gibson Dunn’s recent publications on the FCA may be found on our website, including industry-specific articles, webcasts, presentations, and practical guidance to help companies avoid or limit liability under the FCA. And, of course, we would be happy to discuss these developments—and their implications for your business—with you.

I. FCA ENFORCEMENT ACTIVITY

A. Total Recovery Amounts: 2018 Recoveries Reach Almost $2.9 Billion

The federal government recovered almost $2.9 billion in civil settlements and judgments under the FCA during the 2018 fiscal year. This number, while sizable, marks the first time since 2009 that recoveries failed to crack the $3 billion threshold.[2] Still, this total is the tenth highest one-year total in history, a sign of just how historic the past decade has been.

The health care industry, as in most years, was the primary FCA target in the 2018 fiscal year, as companies and individuals in that industry agreed to pay $2.5 billion to DOJ in 2018 in FCA matters. There were 767 new FCA cases filed in 2018, more than 500 of them in the health care space.

B. Qui Tam Activity

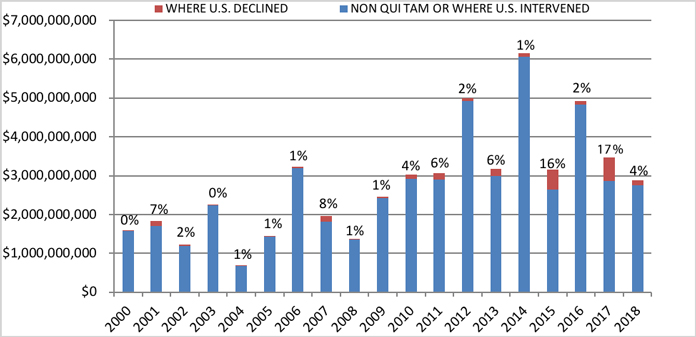

Of the nearly $2.9 billion that the government recovered in 2018, $2.1 billion came from qui tam cases—the lowest number for recoveries from qui tam cases since 2009.[3] Of that total, the vast majority came in cases where the government intervened, while qui tam cases where the government declined intervention accounted for just $119 million of the $2.1 billion in qui tam recoveries, a sharp decline from last year’s figures.

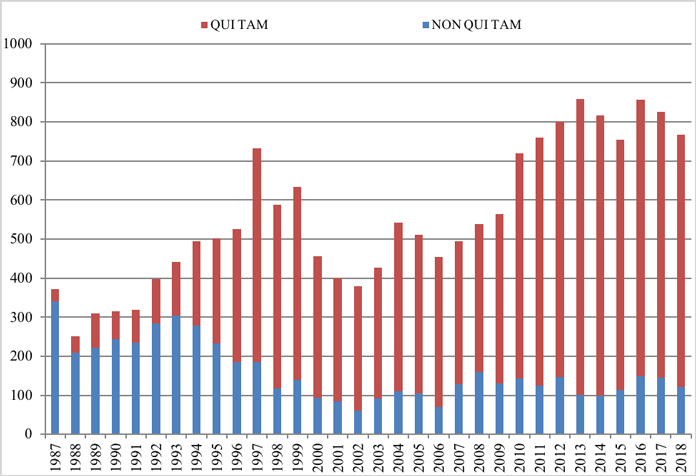

Even as qui tam recoveries decreased, the proportion of all cases initiated by a whistleblower remained in tune with historical averages at 84% (645 of 767) in 2018—a figure that has vacillated between 77% and 88% every year since 2009. Going back farther in time, however, it is important to recall that the amount and proportion of qui tam cases has increased substantially since Congress amended the FCA in 1986: from 1987 to 1991, only about one-quarter of FCA cases were qui tam cases, but whistleblowers have now brought over 12,000 qui tam cases since then—71% of the total.

Of course, qui tam cases are not the only way FCA cases begin. This year also saw far more than the usual amount of recoveries in cases originally filed by the government. This was true even as DOJ seemingly took steps to rein in FCA enforcement activity in certain areas. Indeed, recoveries in such cases leapt to $767 million in 2018—more than double the amount of last year—and above the total in many other recent years (although still lower than in 2012, 2014, and 2016—all of which saw non-qui tam recoveries north of $1.5 billion).

The chart below demonstrates both the increase in overall FCA litigation activity since 1986 and the distinct shift from largely government-driven investigations and enforcement to qui tam-initiated lawsuits. Although there was a slight decline compared to the prior two years, the total number of FCA cases remains far north of where it was in the first decade of the new millennium, when an average of 476 cases were brought per year.

Number of FCA New Matters, Including Qui Tam Actions

Source: DOJ “Fraud Statistics – Overview” (Dec. 21, 2018)

The government opts to intervene in FCA cases filed by qui tam relators about 20% of the time.[4] Even if the government declines to intervene, 70% of any recovery still goes to the government. In fiscal year 2017, the large majority of cases where the government declined to intervene accounted for 17% of all federal recoveries—only the second time such recoveries exceeded 9%. That figure dropped to just 4% in fiscal year 2018, however, marking a return to levels more typically seen in past years.

Settlement or Judgments in Cases where the Government Declined Intervention as a Percentage of Total FCA Recoveries

Source: DOJ “Fraud Statistics – Overview” (Dec. 21, 2018)

C. Trump Administration Enforcement Policy

DOJ began the year by issuing a series of internal guidance memoranda and public speeches in an apparent attempt to shift FCA enforcement policy. In our 2018 Mid-Year Update, we addressed a memorandum from Michael Granston, the Director of the Fraud Section of DOJ’s Civil Division, (the “Granston Memo”) and a memorandum from then-Associate Attorney General Rachel Brand (the “Brand Memo”), which appeared to take at least some initial steps towards addressing potential costs of unbridled FCA enforcement.

As detailed further in our 2018 Mid-Year Update, the Granston Memo directs government lawyers evaluating whether to decline intervention in a qui tam FCA action also to “consider whether the government’s interests are served” by seeking dismissal of the underlying qui tam claims pursuant to 31 U.S.C. § 3730(c)(2)(A).[5] Outlining seven factors for prosecutors to consider when evaluating dismissal of a declined qui tam action, the Granston Memo emphasizes DOJ’s “important gatekeeper role in protecting the [FCA]” and the role that dismissal can play in “preserv[ing] limited resources” and “avoid[ing] adverse precedent.” In addition, the Brand Memo prohibits DOJ from basing its theories of liability in affirmative civil enforcement cases on noncompliance with other agencies’ guidance documents and from using “its enforcement authority to effectively convert agency guidance documents into binding rules.”[6] We also addressed a June 14 speech from Acting Associate Attorney General Jesse Panuccio describing these memos and other policy initiatives, including efforts to formalize Department practices around cooperation credit, compliance program credit, and “piling on” by other agencies and regulatory bodies in settlement discussions.

Although these actions signaled some potentially significant shifts in the FCA enforcement space, it has been less clear how these changes would be put into practice. Several additional announcements by the Trump Administration in the latter half of the year have now set those wheels in motion.

Most notably, on September 25, DOJ announced the rollout of an updated United States Attorneys’ Manual—now titled the Justice Manual.[7] Twenty years’ coming, the Justice Manual appears to incorporate the recommendations set forth in the Granston Memo. Although it does not adopt the Granston Memo wholesale, the Justice Manual does encourage the Department to evaluate a non-exhaustive list of factors, any one of which may be sufficient to support dismissal.[8] In addition to preserving government resources, these factors include “[c]urbing meritless qui tam claims that facially lack merit (either because the relator’s legal theory is inherently defective, or the relator’s factual allegations are frivolous),” “[p]reventing parasitic or opportunistic qui tam actions” that add “no useful information to a pre-existing government investigation,” and “[p]reventing interference with an agency’s policies or the administration of its programs.” The enumerated factors also include controlling litigation brought on behalf of the government “to protect the Department’s litigation prerogatives,” “[s]afeguarding classified information and national security interests,” and “[a]ddressing egregious procedural efforts that could frustrate the government’s efforts to conduct a proper investigation.”

That the Justice Manual made official substantial portions of the Granston Memo (which was not officially released publicly) may reinforce a trend towards more judicious FCA enforcement by DOJ. Other data points also show that trend. In November, DOJ notified the U.S. Supreme Court via an amicus brief that it would move to dismiss the high-profile FCA case against Gilead Sciences (Gilead Sciences., Inc. v. United States ex rel. Campie, 138 S. Ct. 1585 (2018) (discussed in greater detail infra)), should that matter be remanded to the district court in accordance with the Ninth Circuit’s ruling.[9] Then in December, DOJ moved to dismiss 11 qui tam FCA actions brought by Health Choice Group, LLC against multiple pharmaceutical companies.[10] In rejecting allegations that the defendants violated the Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS) by providing assistance with prior authorizations and arranging for nurses to educate patients on proper administration of newly-prescribed medicines, among other items, the government stated that the relators’ allegations “lack[ed] sufficient factual and legal support” and would be contrary to previous guidance issued by the Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General (HHS OIG).[11] Emphasizing that the right for a qui tam plaintiff to proceed with an action without government intervention “is not absolute,” the government moved for dismissal given the need to “preserv[e] scarce government resources and protect[] important policy prerogatives of the federal government’s healthcare programs.”[12] Specifically, the government emphasized that the “relators should not be permitted to indiscriminately advance claims on behalf of the government against an entire industry that would undermine common industry practices the federal government has determined are . . . appropriate and beneficial to federal healthcare programs and their beneficiaries.”[13]

Building on DOJ’s promises to solidify its practices around providing cooperation credit, Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein also announced in November a set of policy changes to “restore” discretion to DOJ attorneys. Most notably, DOJ now will give cooperation credit to companies that identify every individual who was “substantially involved in or responsible for the criminal conduct” under investigation in white collar investigations.[14] This shift recalibrates DOJ policy after the so-called “Yates Memo,” issued by then-Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates, which required corporations to provide “all relevant facts” about individuals involved in misconduct and appeared to apply regardless of the significance of those individuals’ involvement. As such, this policy shift may allow companies to tailor their investigations and advocacy efforts more closely to those individuals most likely to face criminal prosecution. In addition, Deputy Attorney General Rosenstein announced that DOJ attorneys will be “permitted to negotiate civil releases for individuals who do not warrant additional investigation in corporate civil settlement agreements.”[15] Although focused primarily on the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, Deputy Attorney General Rosenstein also remarked on the impact the new standard could have on companies facing civil FCA liability.

In September, HHS OIG unveiled a “Fraud Risk Indicator,” designed to increase transparency for health care organizations and their counsel.[16] According to the HHS OIG website, the Indicator is designed to assess “the future risk posed by persons who have allegedly engaged in civil healthcare fraud”—in other words, parties who have entered into settlement agreements in which the government alleges fraudulent conduct and the settling parties neither admit liability nor enter into a corporate integrity agreement (CIA). Using published criteria for potential exclusion from federal health care programs, the Indicator assigns the settling party to one of five risk categories, ranging from “High Risk – Exclusion” to “Low Risk – Self-Disclosure.” Although intended to better inform “various stakeholders, including patients, family members, and healthcare industry professionals,” the Indicator may well give rise to more questions than answers. For example, it is unclear whether there is a designated process for disputing HHS OIG’s risk assessment (and, if so, how transparent the process will be). HHS OIG also has not shared how it will use the risk classifications when evaluating whether the company must enter a CIA as part of an FCA resolution.

Lastly, there has also been speculation about what approach William Barr, President Trump’s nominee for Attorney General, would bring to FCA enforcement. In the past, Barr has made comments calling the FCA unconstitutional and an “abomination.”[17] While serving at DOJ during the administration of President George H.W. Bush, Barr authored a memorandum questioning the constitutionality of the FCA’s qui tam provisions based on separation of powers concerns. The Supreme Court (and lower courts) have since rejected such arguments. See, e.g., Vermont Agency of Natural Resources v. United States ex rel. Stevens, 529 U.S. 765 (2000). Even if that issue is settled, however—and there have been reports that Barr will back-off such positions during his confirmation hearing—we will be watching carefully to see how Attorney General Barr (if confirmed) influences enforcement of a statute he has so strongly criticized in the past.

D. Industry Breakdown

The distribution of recoveries by industry skewed more heavily towards health care than in prior years. This largely reflects the steep drop in recoveries from the financial industry now that ten years have passed since the financial crisis.[18]

Settlement or Judgments by Industry in 2018

1. Health Care and Life Sciences Industries

2018 was a record setting year in that the health care industry paid nearly 90% of all sums owed to the government in connection with FCA resolutions or cases, eclipsing the total percentage in years past. Even while the percentage share increased, the total amount, approximately $2.5 billion in 2018, recovered from health care companies remained in line with past figures. Since 2010, the government has recovered between $2.4 billion and $2.7 billion from health care companies in each year but two.

As in years past, a handful of large settlements drove the ten-figure sum—with just five settlements accounting for well over $1.5 billion of the total recovery in the health care sector. Nearly a billion dollars came from just two settlements—one in which a California-based pharmaceutical company agreed to pay $360 million to settle allegations that it used a non-profit foundation as a conduit to fund copays of Medicare patients in alleged violation of the AKS,[19] and another in which a wholesale drug manufacturer and its subsidiaries agreed to pay $625 million to resolve allegations that they improperly distributed overfill oncology-supportive drugs and paid kickbacks to induce use of the drugs.[20] Meanwhile, just three other settlements of $150 million,[21] more than $260 million,[22] and $270 million[23] accounted for an additional nearly three quarters of a billion dollars.

DOJ’s and HHS OIG’s enforcement activities once again focused heavily on compliance with the AKS and the Stark Law. The AKS prohibits giving or offering—and requesting or receiving—any form of payment in exchange for referring a product or a service that is covered by federally funded health care programs—and claims resulting from a violation of the AKS are deemed “false” for purposes of the FCA. The Stark Law, or so-called “self-referral” law, prohibits physicians from referring patients to a provider with which the physician has a financial relationship.

While FCA recoveries continued to center on pharmaceutical companies, medical device companies, outpatient clinics, and others, some notable settlements involved hospitals and hospital systems. For instance, a large hospital chain agreed to pay over $260 million to resolve criminal and civil charges premised on allegations that it inflated fees, such as billing for inpatient services that should have been billed as outpatient services, and remunerated physicians for referrals.[24] Further, a regional based hospital chain agreed to pay $84.5 million to resolve allegations that it billed for services provided to patients illegally referred in violation of the AKS and Stark Law.[25]

2. Government and Defense Contracting, Financial, and Other Industries

After an increase to $220 million in 2017, recoveries from government contracting firms fell in 2018 to approximately $100 million. Defense contractors comprised the bulk of government contracting enforcement actions in 2018, in contrast to the prior year, when contractors who provide more routine government services were more of a focus of FCA cases.

Ten years out from the 2008 financial crisis, 2018 saw FCA recoveries from financial services companies trickle to their lowest amount ever, with only a pair of notable settlements (involving two mortgage companies) exceeding $10 million.

II. NOTEWORTHY SETTLEMENTS AND JUDGMENTS ANNOUNCED DURING THE SECOND HALF OF 2018

We summarize below a number of the notable FCA settlements announced during the past six months (we covered notable settlements and judgments from the first half of the year in our 2018 Mid-Year Update). These summaries provide insight into not only the industries that the government has targeted, but also the specific theories of liability that the government and relators have advanced.

A. Settlements

1. Health Care and Life Sciences Industries

- On July 9, 2018, a New York-based family of integrated hospitals and two of its subsidiaries agreed to pay over $14.7 million to settle allegations that they submitted inflated or otherwise ineligible claims for payment. As part of the settlement, the hospital system admitted to, inter alia, submitting claims without sufficient documentation to support the level of services billed; submitting claims for home health services without sufficient medical records to support the claims; and billing Medicare for services referred by physicians with whom the system had a direct financial relationship, in violation of the Stark Law and AKS. The hospital system agreed to pay an additional $895,427 to the State of New York and entered into a CIA with HHS OIG. In total, the four whistleblowers will receive approximately $2.8 million of the recovered funds.[26]

- On July 18, 2018, a New York-based medical device manufacturer agreed to pay $12.5 million to settle allegations that it caused health care providers to submit false claims for procedures involving two unapproved devices that it marketed with purportedly false and misleading statements. The whistleblower, who formerly worked in the manufacturer’s marketing department, will receive approximately $2.3 million of the settlement.[27]

- On July 18, 2018, two consulting companies and nine affiliated skilled nursing facilities in Florida and Alabama agreed to pay $10 million to settle allegations that they submitted, or caused the submission of, claims for unnecessary rehabilitation therapy services. The three whistleblowers, former employees of one of the nursing facilities, will receive $2 million of the recovery.[28]

- On August 2, 2018, a Detroit-based regional hospital system agreed to pay $84.5 million to resolve allegations that it maintained improper relationships with eight referring physicians, submitted claims for services provided to illegally referred patients in violation of the AKS and Stark Law, and misrepresented the qualifications of a radiology center to federal programs. The hospital system has also entered into a five-year CIA with HHS OIG. The four whistleblowers will receive 15% to 25% of the recovery.[29]

- On August 2, 2018, a South Carolina behavioral-therapy provider for children with autism paid approximately $8.8 million to resolve allegations that it billed for services either misrepresented in the claims or not provided at all. As part of the settlement, the provider and its parent company entered into a CIA with HHS OIG. The whistleblower, a former employee, will receive $435,000.[30]

- On August 3, 2018, a national hospital system, as well as its founder and chief executive officer, agreed to pay $65 million to settle allegations that 14 of its California hospitals admitted Medicare patients for unnecessary inpatient treatment and up-coded claims by falsifying information about patient diagnoses. As part of the settlement, the system entered a five-year CIA with HHS OIG. The whistleblower, a former director of improvement at one of the California hospitals, will receive over $17.2 million of the recovery.[31]

- On August 8, 2018, a pharmaceutical company agreed to pay at least $150 million to resolve allegations that it improperly paid medical practitioners to prescribe its opioid medication, in violation of the AKS.[32] The company’s founder and five other former executives face criminal charges, including a potential January 2019 trial for conspiracy to commit racketeering, mail and wire fraud, and conspiracy to violate the AKS, and at least two of the defendants have agreed to plead guilty already, including the ex-CEO.[33]

- On August 15, 2018, a Pennsylvania-based operator of long-term care and rehabilitation hospitals agreed to pay more than $13 million to resolve allegations that they knowingly submitted claims for services referred and provided in violation of the AKS and Stark Law. Pursuant to the settlement, the operator will pay additional monies to Texas and Louisiana, and has entered a five-year CIA with HHS OIG. The whistleblower will receive approximately $2.3 million of the recovered funds.[34]

- On August 16, 2018, a Florida-based nationwide provider of oxygen and home respiratory-therapy services paid $5.25 million to settle allegations that it offered illegal price reductions to Medicare beneficiaries, in violation of the AKS. The whistleblower, a former billing supervisor for the company, will receive $918,750 of the recovery.[35]

- On August 23, 2018, a Texas-based national provider of rehabilitation-therapy services agreed to pay $6.1 million to resolve allegations that it offered improper inducements to skilled nursing facilities and physicians in relation to services provided to Medicare beneficiaries. The whistleblower will receive approximately $915,000 of the recovery.[36]

- On August 27, 2018, seven ambulance industry defendants agreed to pay more than $21 million to settle allegations that they offered kickbacks to several municipal entities to secure business. The whistleblower will receive over $4.9 million of the recovery.[37]

- On September 25, 2018, a Florida-based hospital chain, and a Pennsylvania-based subsidiary, agreed to pay over $260 million to resolve criminal and civil charges for allegedly billing for inpatient services that should have been billed as outpatient services, remunerating physicians for referrals, and inflating claims for emergency department fees, as well as allegations Hospital administrators and executives set mandatory admission-rate benchmarks and pressured physicians to meet them by admitting patients in non-medically necessary cases. A portion of the recovery will go to participating state programs. The allegations resolved by the settlement were originally brought in eight whistleblower law suits. Two whistleblowers will receive $15 million and $12.4 million of the recovery; the other whistleblowers’ shares have not yet been determined.[38]

- On September 28, 2018, a Montana-based regional health care system and six subsidiaries agreed to pay $24 million to settle allegations that they submitted claims to Medicare for services referred in violation of the Stark Law and AKS. The health care system allegedly paid excessive compensation to more than 60 physicians, paid excessive compensation to induce referrals, and provided administrative services at below fair market value. The whistleblower, a former chief financial officer for the system’s physician network, will receive approximately $5.4 million of the recovery.[39]

- On October 1, 2018, a wholesale drug manufacturer and its subsidiaries agreed to pay $625 million to resolve allegations that they improperly repackaged and distributed overfill oncology drugs. Last year, one of the subsidiaries pled guilty to illegally distributing misbranded drugs that were not registered with the FDA, and agreed to pay $260 million to resolve criminal charges. This year’s settlement resolves the parent’s civil liability for submitting purportedly false claims for the allegedly illegally repackaged drugs and allegedly providing kickbacks to induce physicians to purchase the repackaged drugs. The whistleblower will receive approximately $93 million of the civil settlement.[40]

- On October 1, 2018, a Medicare Advantage provider agreed to pay $270 million to resolve allegations that it provided inaccurate information that resulted in Medicare Advantage Plans receiving inflated Medicare payments. The whistleblower will receive approximately $10.1 million of the settlement.[41]

- On November 6, 2018, an Indiana-based dental care firm agreed to pay approximately $5.1 million to resolve allegations that it submitted false claims by up-coding dental procedures, billing for unperformed or medically unnecessary procedures, and that it allegedly violated state law prohibiting rewarding, disciplining, or otherwise directing personnel in a manner that compromises clinical judgment. The firm will pay approximately $3.4 million to the United States and $1.8 million to Indiana. Notably, the firm declined to agree to a proposed CIA, and as a result, is considered by the government a “continuing high risk” to health care programs and beneficiaries.[42]

- On December 4, 2018, the world’s largest medical device maker agreed to pay $50.9 million to settle allegations relating to conduct by two of its subsidiaries. The total settlement included $17.9 million in connection with its pleading guilty to a misdemeanor for allegedly distributing an adulterated neurovascular device in violation of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act; $13 million to resolve civil liability for allegedly paying kickbacks to hospitals and institutions to induce the use of a medical device for stroke patients;[43] and an additional $20 million to resolve a DOJ investigation into its subsidiaries’ market-development and physician-engagement activities.[44]

- On December 6, 2018, a California-based pharmaceutical company agreed to pay $360 million to settle claims that it used a non-profit foundation as an illegal conduit to pay copays of Medicare patients taking its drug, in violation of the AKS, based on allegations that, rather than allowing financially needy Medicare patients to participate in the company’s free drug program, it referred them to the foundation, which paid their copays, resulting in claims to Medicare for the remaining cost.[45]

- On December 11, 2018, an integrated health care system located in Wisconsin, Illinois, and Michigan agreed to pay $12 million to settle allegations that it entered into improper compensation arrangements with two physicians in violation of the Stark Law.[46]

- On December 11, 2018, a Pennsylvania-based health system and its chief executive officer agreed to pay $12.5 million to settle allegations that the health system submitted inflated claims for orthopedic surgeries by unbundling and separately billing for services that were part of the same surgery. The system entered a five-year CIA with HHS OIG as part of the settlement.[47]

2. Government Contracting and Defense/Procurement

- On July 6, 2018, a Colorado-based energy industry services company and its owner agreed to pay $14.4 million to resolve allegations that they submitted fraudulent claims for reimbursement to the Department of Energy. A week earlier, the company’s owner was sentenced to 18 months in prison after pleading guilty to a felony count of intentional submission of false claims. The government alleged that company’s owner submitted fake invoices for work by contractors and engineers that was never performed, as well as that the owner funneled award money to pay for legal fees, jewelry, car payments, and international travel.[48]

- On July 26, 2018, a Minnesota-based consumer goods and health care conglomerate agreed to pay $9.1 million to settle whistleblower claims alleging that it knowingly sold defective earplugs to the U.S. military.[49] The whistleblower was awarded $1.9 million of the settlement.

- On November 14, 2018, three South Korea-based oil refiners and logistics companies agreed to pay a total of $236 million in criminal fines and civil damages to resolve allegations of a bid-rigging conspiracy. The settlements consisted of $82 million in criminal fines and $154 million for alleged civil antitrust and FCA violations. The FCA civil investigation arose from a whistleblower lawsuit involving allegations of false statements made to the government in connection with the companies’ decade-long conspiracy to rig bids on Department of Defense contracts to supply fuel to Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force bases in South Korea.[50]

3. Financial Services

- On October 19, 2018, a Florida-based mortgage company agreed to pay $13.2 million to resolve claims that it had falsely certified compliance with Federal Housing Administration (FHA) mortgage insurance requirements. The company had participated as a direct endorsement lender (DEL) in the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s FHA insurance program. Under the program, if a DEL approves a loan for FHA insurance and the loan later defaults, the holder of the loan can submit an insurance claim to HUD for the losses. Because the FHA does not review a loan for compliance before it endorses the loan, DELs are required to follow certain program rules to ensure that they are properly underwriting and certifying mortgages. The government alleged that the company knowingly submitted loans for FHA Insurance that did not qualify, improperly incentivized underwriters, and knowingly failed to perform quality control reviews. The whistleblower, a former employee of the company’s related entity, will receive almost $2 million of the settlement.[51]

- On December 12, 2018, a Pennsylvania-based mortgage company agreed to pay $14.5 million to resolve similar claims regarding compliance with FHA insurance requirements. A business that the company acquired in 2015 had participated as a DEL in the FHA insurance program. The government alleged that the business had misrepresented that its loans met certain origination, underwriting, and quality control requirements. The investigation was triggered by a whistleblower qui tam suit filed by one of the business’s former employees, who will receive about $2.4 million of the settlement.[52]

4. Other

- On November 13, 2018, two international airlines agreed to pay $5.8 million to resolve claims that they falsely reported mail delivery times under contracts with the United States Postal Service (USPS). USPS had contracted with the commercial airlines to deliver mail to domestic and international locations, and the government alleged that the airlines had submitted false scans reporting the time of delivery.[53]

- On December 4, 2018, a New York-based law firm agreed to pay a total of more than $4.6 million to resolve allegations that it submitted false and inflated bills to Fannie Mae and the Department of Veterans Affairs for legal work in connection with foreclosures and evictions. The case arose from a whistleblower lawsuit, in which the law firm agreed to pay the United States an additional $1.5 million, for a total recovery to the United States of more than $6.1 million arising out of these claims.[54]

III. LEGISLATIVE ACTIVITY

A. Federal Legislation

FCA-related federal legislative activity remained quiet through the end of 2018. As lawmakers’ attention turned to election-year campaigning, House and Senate Republicans chose not to renew their attempts to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which could have impacted the ACA’s amendments to the FCA as discussed in our 2017 Mid-Year Update. That said, a recent decision by a district court in Texas striking down the ACA in its entirety could, if it withstands appellate scrutiny, negate the ACA’s amendments to the FCA. See Texas v. United States, 340 F. Supp. 3d 579 (N.D. Tex. 2018). We will be watching that case carefully.

Legislators did not ignore the FCA entirely in the latter half of the year. In August, Senator Chuck Grassley (R-IA), a longtime champion of the FCA, penned an op-ed highlighting the importance of whistleblowers in protecting taxpayer dollars and arguing for greater congressional oversight of federal health care programs. Specifically, Senator Grassley lobbied for support for bipartisan legislation cosponsored by Senator Richard Blumenthal (D-CT) that would strengthen the Physician Payment Sunshine Act (PPSA). Enacted as part of the ACA, the PPSA requires drug and medical device manufacturers to report transfers of value to physicians or teaching hospitals to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, which become public after a 30-day review period. The Senators’ bill would expand the PPSA to include transfers of value to nurse practitioners and physicians assistants as well.[55] The Senate has not yet moved on this legislation, but we will track any progress in our 2019 Mid-Year Update.

We also are watching closely as the Trump Administration and the new House majority push forward with various policy initiatives, including those targeted at drug pricing. FCA cases premised on drug-pricing theories have been common in recent years, including cases based on reporting of drug prices to the government and alleged AKS violations connected to drug prices. See, e.g., United States ex rel. Derrick v. Roche Diagnostics Corp., 2018 WL 2735090 (N.D. Ill. June 7, 2018) (denying a motion to dismiss an FCA case alleging that Roche Diagnostics violated the AKS by forgiving a disputed drug rebate amount owed to it by a Medicare Advantage plan). Any legislation (or regulations or guidance) that changes the rules for drug pricing could therefore have significant effects on potential FCA liability.

B. State Legislation

As detailed in our 2018 Mid-Year Update and elsewhere, Congress created financial incentives in 2005 for states to enact their own false claims statutes that are as effective as the federal FCA in facilitating qui tam lawsuits. States passing review by HHS OIG may be eligible to “receive a 10-percentage-point increase in [their] share of any amounts recovered under such laws” in actions filed under state FCAs.[56] As of mid-2018, HHS OIG approved laws in 12 states (Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Massachusetts, Montana, Nevada, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, and Vermont), while 17 states are still working towards FCA statutes that meet the federal standard (California, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Louisiana, Michigan, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Rhode Island, Virginia, Washington, and Wisconsin).

HHS OIG previously issued an end-of-2018 deadline for states to bring their FCA statutes into compliance or risk losing the 10-percentage-point increase. As predicted in our 2018 Mid-Year Update, this deadline has spurred some action, and FCAs in three additional states—North Carolina, Virginia, and Washington—have since received HHS OIG’s stamp of approval.

Apart from those three states, however, other states with FCA statutes not yet meeting the federal standard have made little progress in amending those statutes. For example, a Michigan bill that would expand the state’s current False Claims Act beyond the Medicaid context has stalled in the state’s Senate Committee on the Judiciary since January 2017,[57] and another Michigan bill that would amend the civil penalties in the Act to mirror those allowed under the federal FCA has been stuck in the same committee since November 2017.[58] Similarly, a Pennsylvania bill to create the state’s False Claims Act has languished in the state’s House Judiciary Committee since March 2017,[59] and a New York bill that would increase civil penalties for violations of the state’s FCA was returned to the General Assembly after dying in the state Senate in January 2018.[60]

Although HHS OIG’s “grace period” for states to receive the 10-percentage point incentive is expiring, we will notify you of any additional state-level FCA developments in our next Mid-Year Update.

IV. NOTABLE CASE LAW DEVELOPMENTS

A. The Supreme Court Grants Certiorari in One Case and Considers Two Others

The Supreme Court has considered issues under the FCA four times in the last four years, and 12 times in the last eighteen years. Yet again in 2018, the Court has indicated its intent to scrutinize lower courts’ interpretation of the FCA.

The Supreme Court granted certiorari in a case that presents issues related to the FCA’s statute of limitations, United States ex rel. Hunt v. Cochise Consultancy, Inc., 887 F.3d 1081, 1083 (11th Cir. 2018). The FCA has a default six-year statute of limitations, which can be extended up to 10 years when information relevant to the claim does not become known to the relevant government official until later in time. Circuit courts have split on whether a qui tam relator may take advantage of that longer, ten-year period in cases where the government has declined to intervene. The questions presented by petitioners’ writ of certiorari are “whether a relator in a False Claims Act qui tam action may rely on the statute of limitations in 31 U.S.C. § 3731(b)(2) in a suit in which the United States has declined to intervene and, if so, whether the relator constitutes an ‘official of the United States’ for purposes of Section 3731(b)(2).” Gibson Dunn represents the petitioners in the case, and we will be sure to report back in these pages when the Court decides the case.

As we reported in our 2018 Mid-Year Update, the Court asked for the Solicitor General’s input in a case involving Gilead Sciences Inc. Many Court observers thought the case had a good chance of being heard because it raised important issues about, among other things, application of the Court’s landmark 2016 decision in Escobar.[61] But the Solicitor General’s response argued strongly that the Court should not grant certiorari.[62] Further, the government indicated it would move to dismiss the case if it were sent back to the district court, contending that the case is “not in the public interest.”[63] DOJ explained that its decision was based on a “thorough investigation” of the merits of the case, but also concerns about the “burdensome” discovery requests that the parties would make of the FDA if the case is allowed to continue.[64] The about-face by the government, after years of permitting the case to move forward through the lower courts, may indicate heightened concern within DOJ about adverse rulings under Escobar (and, of course, the burden of discovery into government knowledge, which Escobar explained is a key factor in assessing materiality). As noted above, it also marks a high-profile exercise of the DOJ’s avowed rededication to dismissing at least some unmeritorious cases under the analysis set forth in the Justice Manual and the Granston Memo. On January 7, 2019, the Supreme Court heeded the Solicitor General’s views and denied certiorari.

Finally, as we’ve reported in these pages before, parties in recent years have frequently asked the Court to resolve a circuit split on the pleading standard for FCA claims under Rule 9(b). The key question that recurs in lower courts is how much specificity a relator must provide under the FCA, and, in particular, whether the relator must provide examples of actual false claims, or just information alleged to be sufficient to infer that such claims were likely submitted. Almost every year, some plaintiff or defendant petitions for certiorari on this issue. But despite showing some initial interest back in 2014, when the Court requested the view of the Solicitor General on these issues before ultimately denying certiorari,[65] the Court has since steadfastly rejected these cases. This year was no exception, with the Court denying certiorari in another case raising pleading questions under the FCA.[66] Absent further divisions in the courts of appeal, it is unlikely that this issue will make it to the Supreme Court anytime soon.

B. Courts Continue to Grapple with Escobar

Since it was decided in 2016, Escobar has become a focal point of FCA litigation at both the appellate and trial court levels. Indeed, a number of courts have issued opinions interpreting Escobar as it pertains to the implied false certification theory and more generally to the Court’s direction that “rigorous” enforcement of the materiality and scienter elements will protect against “concerns about fair notice and open-ended liability” in FCA matters. Escobar, 136 S. Ct. at 2002. As recent decisions demonstrate, Escobar continues to have a wide-ranging impact on FCA jurisprudence.

1. The Ninth Circuit Addresses the Impact of Escobar on Its Prior Precedents

In United States ex rel. Rose v. Stephens Institute, 909 F. 3d 1012 (9th Cir. 2018), amending and superseding 901 F.3d 1124 (9th Cir. 2018), the Ninth Circuit addressed the impact of Escobar on two of its prior precedents.

First, the Ninth Circuit explicitly, albeit reluctantly, acknowledged that Escobar changed the landscape of FCA liability in the Ninth Circuit and overruled its prior holding in Ebeid ex rel. United States v. Lungwitz, 616 F.3d 993 (9th Cir. 2010). In Ebeid, the Ninth Circuit held that a relator could plead an implied false certification claim merely by alleging that a defendant submitted a claim for payment while in noncompliance with a “law, rule, or regulation” that “is implicated in” submitting such a claim. Id. at 998. In Escobar, however, the Supreme Court held that FCA liability can exist under an implied false certification theory under two conditions: “First, the claim does not merely request payment, but also makes specific representations about the goods or services provided; and second, the defendant’s failure to disclose noncompliance with material statutory, regulatory, or contractual requirements makes those representations misleading half-truths.” 136 S.Ct. at 2001.

Revisiting Ebeid, the Ninth Circuit observed in Rose that Escobar, if analyzed “anew,” would not necessarily require Ebeid to be overruled because Escobar “did not state that its two conditions were the only way to establish liability under an implied false certification theory.” Id. at 1018 (emphasis in original). Regardless, the Rose court conceded that other Ninth Circuit cases since Escobar have gone the opposite direction. The Ninth Circuit’s prior holdings in United States ex rel. Kelly v. Serco, Inc., 846 F.3d 325 (9th Cir. 2017) and United States ex rel. Campie v. Gilead Sciences, Inc., 862 F.3d 890, 901 (9th Cir. 2017)—”without discussing whether Ebeid has been fatally undermined—appeared to require Escobar’s two conditions nonetheless.” Id. (emphasis in original).

Second, the Rose court also considered whether Escobar had any impact on the Ninth Circuit’s decision in United States ex rel. Hendow v. University of Phoenix, 461 F.3d 1166 (9th Cir. 2006). The Hendow court held at the pleading stage that the relevant question for materiality “is merely whether the false certification . . . was relevant to the government’s decision to confer a benefit.” Id. at 1173. Accordingly, the Ninth Circuit determined that a failure to comply with a regulatory requirement that allegedly was a condition of payment was material to government payment. Id. at 1177. In Escobar, however, the Supreme Court concluded that whether the government has made compliance with a statutory or regulatory provision a “condition of payment is relevant, but not automatically dispositive” of materiality. 136 S.Ct at 2003.

Nevertheless, the Rose court found no basis for overruling Hendow on this point because Hendow “did not state that noncompliance [with a statute, regulation, or contract] is material in all cases.” Id. at 1019 (emphasis in original) (citation omitted). The court went on to clarify its view that Escobar provides a “‘gloss’ on the analysis of materiality”; although “it is clear that noncompliance with the incentive compensation ban is not material per se” after Escobar, nonetheless “the four basic elements of a False Claims Act claim, set out in Hendow, remain valid.” Id. at 1020. In applying the Escobar materiality factors, the majority noted that conditioning payment on compliance with the incentive compensation ban “may not be sufficient, without more, to prove materiality, but it is certainly probative evidence of materiality.” Id.

In a dissenting opinion, Judge Smith argued that Hendow‘s reasoning—which gave no weight to whether the government had prosecuted violations of the incentive compensation ban and found materiality based solely on statutory, regulatory, and contractual provisions conditioning payment on compliance with the ban—had been explicitly overruled by Escobar, which focuses the materiality inquiry on whether the government “would truly find . . . noncompliance material to a payment decision.” Id. at 1024.

2. The Sixth Circuit Addresses Pleading Requirements for Materiality Post-Escobar

In Escobar, the Supreme Court identified factors that can bear on the materiality evaluation, including, but not limited to, whether “the defendant knows that the Government consistently refuses to pay claims in the mine run of cases based on non-compliance,” whether “the Government regularly pays a particular type of claim in full despite actual knowledge that certain requirements were violated,” and whether the noncompliance was “minor or insubstantial.” 136 S.Ct. at 2003-04. In United States ex rel. Prather v. Brookdale Senior Living Communities, Inc., 892 F.3d 822 (6th Cir. 2018) (Prather II), the Sixth Circuit weighed in on the specific application of some of these factors at the motion to dismiss stage. The relator asserted that the defendants fraudulently sought reimbursements from Medicare for home health services without first obtaining a certification of need from a physician as required by the applicable federal regulations.

Reversing the district court opinion dismissing the allegations, the Prather II court held that Escobar does not require FCA plaintiffs to allege in their pleadings that the government has previously brought enforcement actions under similar circumstances in order to establish materiality. Prather II, 892 F.3d at 833-34. The court further noted that Escobar itself held that none of the materiality factors is dispositive, that information about prior government action may be particularly difficult for relators to obtain at the pleading stage, and that on a motion to dismiss the complaint must be construed in the plaintiff’s favor. Id. at 834.

Additionally, the Prather II court also held that the government’s decision not to intervene was irrelevant to the materiality inquiry. Id. at 836. Specifically, it noted that the government had declined to intervene in Escobar itself, but that this had gone unmentioned in Escobar‘s materiality analysis. Id. Moreover, the Sixth Circuit held that a contrary finding would undermine the purpose of the FCA, which is “designed to allow relators to proceed with a qui tam action even after the United States has declined to intervene.” Id.

3. The Third, Sixth, and Seventh Circuits Strictly Construe the FCA’s Scienter Requirement

Three recent circuit court decisions address the “strict enforcement” of the scienter requirement mandated by Escobar.

In United States ex rel. Streck v. Allergan, No. 17-1014, 2018 WL 3949031 (3d Cir. 2018), the Third Circuit held that a relator fails to plead scienter where the defendant acted based on a reasonable, if incorrect, interpretation of relevant statutory and regulatory guidance. In so doing, the court relied on the three-part analysis set forth by the D.C. Circuit in United States ex rel. Purcell v. MWI Corp., 807 F.3d 281, 287-88 (D.C. Cir. 2015), which built on the Supreme Court’s decision in Safeco Insurance Co. v. Burr, 551 U.S. 47 (2007). The relator in Streck had alleged that pharmaceutical companies violated the FCA by failing to account for “price-appreciation credits” in submitting Average Manufacturing Prices (AMP) for certain drugs for the purposes of calculating rebated owed by those companies to Medicaid under the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program. 2018 WL 3949031 at *1.

In affirming the district court’s rejection of relator’s claims, the court first considered “whether the relevant statute was ambiguous.” Id. at *3. Second, the court evaluated “whether [the] defendant’s interpretation of that ambiguity was objectively reasonable.” Id. And finally, the court assessed “whether [the] defendant was ‘warned away’ from that interpretation by available administrative and judicial guidance.” Id. The court held that the statutory definition of “price paid to the manufacturer” for AMP purposes was unclear because it did not specify “initial” price (which would have excluded subsequent price-appreciation credits) or “cumulative” price (which would have included them). Id. at *4-5. Although the court acknowledged that defendants’ interpretation excluding price-appreciation credits may not be the “best interpretation of the statute,” it nonetheless held that “this reasonable interpretation of an ambiguous statute was inconsistent with the reckless disregard [relator] was required to allege at this stage of the litigation” and that there was not any guidance “warn[ing] away” from that interpretation. Id. at *6. Accordingly, the relator failed to properly allege scienter. Id.

In United States ex rel. Harper v. Muskingum Watershed Conservancy District, 739 Fed. App’x 330 (6th Cir. 2018), the Sixth Circuit made clear that while pleading scienter is not subject to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 9(b)’s heightened fraud pleading standard, “a complaint that shows no more than ‘the mere possibility of misconduct . . . is insufficient.'” Id. at 334 (quoting Ashcroft v. Iqbal, 556 U.S. 662, 679 (2009)). The relator alleged that the defendant “fail[ed] to transfer certain property interests to the United States after determining those interests were no longer necessary to perform its charter provisions” as required under a 1939 agreement with the federal government. Id. at 331-33. The relator asserted that board minutes from 1939 demonstrated that the defendant was aware of this obligation. Id. at 333. The court recognized that the minutes “could mean that [the defendant] believed more than seventy years later that [its behavior] violated that obligation,” but held that “[a] complaint that requires [a court] to make[] inference[s] upon inferences to supply missing facts does not satisfy Rule 8’s pleading requirements.” Id. at 334 (emphasis in original) (internal quotations omitted).

In United States ex rel. Berkowitz v. Automation Aids, Inc., 896 F.3d 834 (7th Cir. 2018), the Seventh Circuit emphasized that to plead scienter a plaintiff must make factual allegations specific to the allegedly false claims for payment, rather than general allegations of an existing duty that was violated. The relator asserted an implied false certification claim, alleging that the defendants, who had contracted with the government to provide office and IT supplies, violated the FCA by submitting bills for products made in countries that were not on an approved list. Id. at 838. The court found that the relator had failed to allege “any specific facts demonstrating what occurred at the individualized transactional level for each defendant,” including “what particular information any sales orders submitted by the defendants contained.” Id. at 841. Accordingly, the court held that the complaint only established that “the defendants may have sold non-compliant products during a certain time period,” which “does not equate to the defendants making a knowingly false statement in order to receive money from the government.” Id. at 841–42. Thus, given Escobar‘s guidance that the “scienter requirement[]” should be “strict[ly] enforce[d],” the relator had “[a]t most” alleged that “defendants made mistakes or were negligent,” which “is insufficient to infer fraud under the FCA.” Id. at 842.

C. The Ninth and Tenth Circuits Clarify the FCA’s Falsity Requirement

The FCA prohibits presentation of “false or fraudulent claim[s]” for payment, but does not specifically define what it means for a claim to be false or fraudulent. 31 U.S.C. § 3729. Two recent circuit court decisions have sought to clarify the falsity element.

In United States ex rel. Polukoff v. St. Mark’s Hospital, 895 F.3d 730 (10th Cir. 2018), the relator alleged that a cardiologist with whom he had worked performed numerous medically unnecessary heart surgeries billed to Medicare. Id. at 737–38. The district court granted defendant’s motion to dismiss, holding that a medical judgment—such as a physician’s judgment as to the medical necessity of a procedure—”‘cannot be false’ for purposes of an FCA claim” absent regulations specifically restricting that judgment. Id. at 741–42. The Tenth Circuit reversed, rejecting “a bright-line rule that medical judgment can never serve as a basis for an FCA claim.” Id. at 742. Rather, the court held that “[i]t is possible for a medical judgment to be ‘false or fraudulent’ as proscribed by the FCA,” noting that the Medicare Program Integrity Manual states that a claim is not reimbursable unless it meets the government’s definition of “reasonable and necessary.” Id. Accordingly, the court concluded that a doctor’s certification of medical necessity “is ‘false’ under the FCA if the procedure was not reasonable and necessary under the government’s definition of the phrase,” id. at 743, which the court found to be adequately alleged in the case before it.

In United States ex rel. Berg v. Honeywell International, Inc., 740 Fed. App’x 535 (9th Cir. 2018), the Ninth Circuit affirmed a district court opinion holding that where calculations underlying cost estimates submitted in connection with a government contract are sufficiently disclosed, those estimates are not false for FCA purposes even where they were incorrect under the relevant statutory and regulatory framework. The relator in Berg alleged that Honeywell had submitted false estimates of energy savings relating to improvements to Army buildings. Berg, 740 Fed. App’x at 537. The district court granted summary judgment in Honeywell’s favor, finding that because Honeywell “disclosed the assumptions and math underlying its estimates” those estimates were not false for FCA purposes. Id. The Ninth Circuit affirmed, noting that “the scope of Honeywell’s statements and the qualifications upon them were sufficiently clear, so that the statements—as qualified—were not objectively false or fraudulent.” Id. The court further clarified that even if Honeywell’s estimates were incorrect under the statutory and regulatory framework governing the kinds of contracts at issue, “the statutory phrase ‘known to be false’ does not mean incorrect as a matter of proper accounting methods, it means a lie.” Id. at 538.

D. Courts Further Elaborate on the Application of Rule 9(b)’s Particularity Requirement to FCA Claims

In last year’s year-end update, we took note of the “varying approaches” circuit courts have taken to applying Rule 9(b)’s heightened pleading standards to FCA claims. Rule 9(b) requires a party “alleging fraud or mistake . . . [to] state with particularity the circumstances constituting fraud or mistake.” Once again, this year, several circuits addressed how that standard applies in FCA cases, even while, as noted above, the Supreme Court declined once again to enter the fray.

1. The Ninth Circuit Addresses Rule 9(b) Pleading Standards in the Context of Alleged Group Fraud

In United States ex rel. Silingo v. WellPoint, Inc., 904 F.3d 667 (9th Cir. 2018), the Ninth Circuit addressed Rule 9(b)’s heightened pleading standard as applied to an FCA suit filed against multiple defendants in a case of so-called “group fraud.” In Silingo, the relator worked for a company that provided in-home health assessments of Medicare beneficiaries for Medicare Advantage organizations. Id. at 674. The relator alleged not only that her company, but also the organizations who contracted with her company, submitted fraudulent Medicare Advantage reimbursement claims based on inadequate or false health documentation provided by her company. Id. at 674–75. The organizations moved to dismiss the complaint on the grounds that it failed to plead fraud with sufficient particularity as to any individual organization. Id. at 676. The district court agreed, and dismissed the claims. Id.

The Ninth Circuit reversed, holding that when defendants have “the exact same role in a fraud,” a complaint does not need to distinguish between them in order to satisfy the particularity requirement of Rule 9(b). Id. at 677. In other words, “[t]here is no flaw in a pleading . . . where collective allegations are used to describe the actions of multiple defendants who are alleged to have engaged in precisely the same conduct.” Id. (quoting United States ex rel. Swoben v. United Healthcare Ins. Co., 848 F.3d 1161, 1184 (9th Cir. 2016)). The court analogized this type of fraud to a “wheel conspiracy” in which a single party (the wheel) separately agrees with two or more other parties (the spokes)—whose “parallel actions . . . can be addressed by collective allegations.” Id. at 678.

2. The Eleventh Circuit Requires Relators to Plead at Least One False Claim with Specificity

In Carrell v. AIDS Healthcare Foundation, Inc., 898 F.3d 1267 (11th Cir. 2018), the Eleventh Circuit considered the adequacy of pleadings that alleged fraudulent activity was the basis for claims made to the government, but otherwise failed to explicitly link any such activity to a single purportedly false claim. The relators alleged generally that the defendant had unlawfully incentivized employees to register patients for medical treatment, and that the treatment had then been submitted for reimbursement through federal health care programs. Id. at 1270. The district court dismissed all but two of the relators’ claims for lack of particularity pursuant to Rule 9(b). Id. at 1271.

The Eleventh Circuit upheld the dismissal of these claims on the pleadings, holding that Rule 9(b)’s particularity requirement necessitated a “specific allegation of the ‘presentment of [a false] claim.'”[67] Id. at 1278 (quoting United States ex rel. Clausen v. Lab. Corp. of Am., 290 F.3d 1301, 1311 (11th Cir. 2002)). Thus, even if the “mosaic of circumstances” alleged by the relators—”that the Foundation provided incentives to certain patients and employees, that the Foundation frequently requested reimbursement from federal health care programs, and that Foundation policies focused on aggressive patient recruitment”—was assumed to be true, the relators’ claims must be dismissed for “fail[ure] to allege with particularity that these background factors ever converged and produced an actual false claim[.]” Id. at 1277.

E. The Second Circuit Expands A Circuit Split Regarding the First-to-File Bar

The FCA’s so-called “first-to-file bar” limits the ability of qui tam relators to bring “a related action based on the [same] facts” as a “pending action.” 31 U.S.C. § 3730(b)(5). As discussed in last year’s update, there is a developing circuit split regarding whether a relator may escape the first-to-file bar by filing an amended complaint once the earlier, “pending action” has been dismissed. In the First Circuit, such an amendment has been deemed by the court in at least some circumstances to cure the first-to-file failure. United States ex rel. Gadbois v. PharMerica Corp., 809 F.3d 1, 4–5 (1st Cir. 2015). But in the D.C. Circuit a relator is not permitted to proceed based on an amended complaint if the same relator’s original complaint was otherwise prohibited by the first-to-file bar. United States ex rel. Shea v. Cellco P’ship, 863 F.3d 923, 926 (D.C. Cir. 2017). The difference in approach is potentially significant for relators; if they are forced to re-file their complaint, it may be time-barred, whereas they can contend that the date of an amended complaint relates back to the original complaint for statute-of-limitations purposes.

In United States ex rel. Wood v. Allergan, Inc., 899 F.3d 163 (2d Cir. 2018), the Second Circuit sided with the D.C. Circuit on this disagreement. Relying on the plain language of the statute—which mandates dismissal when a relator “brings” an action while a related action is pending—the Wood court held that amendment could not cure a first-to-file defect because “a claim is barred by the first-to-file bar if at the time the lawsuit was brought a related action was pending.” Id. at 172. The court did confirm, however, that dismissal based on the first-to-file bar should be without prejudice, id. at 175, and that “absent a statute of limitations issue, the relator will be able to re-file her action, without violating the first-to-file bar,” id. at 174.

Additionally, the Wood court further expanded a different circuit split regarding whether a complaint that fails to allege fraud with sufficient particularity pursuant to Rule 9(b) can bar a later-filed complaint under the first-to-file rule. The Sixth Circuit has held that a complaint that was “legally infirm under Rule 9(b)” cannot “preempt [a] later-filed action” even though the allegations of the first-filed complaint “‘encompass’ the specific allegations of fraud made” in the later-filed action. Walburn v. Lockheed Martin Corp., 431 F.3d 966, 973 (6th Cir. 2005). However, the Second Circuit declined to adopt that standard, but instead followed the D.C. Circuit’s decision in United States ex rel. Batiste v. SLM Corp., 659 F.3d 1204 (D.C. Cir. 2011) by holding that there was no basis to incorporate Rule 9(b)’s particularity requirement into the statute. Wood, 899 F.3d at 169–70. Accordingly, the fact that a subsequent complaint might be “more detailed” had no bearing on the application of the first-to-file bar. Id. at 169.

As more courts provide their insights on these issues, they may need to be resolved by the Supreme Court.

F. The Third Circuit Clarifies Application of Public Disclosure Bar

The FCA’s public disclosure bar mandates the dismissal of a FCA action “if substantially the same allegations or transactions” forming the basis of the action have been publicly disclosed and the relator is not an “original source.” 31 U.S.C. § 3730(e)(4).

In United States v. Omnicare, Inc., 903 F.3d 78 (3d Cir. 2018), the Third Circuit addressed the situation where a relator uses publicly available information to shed light on certain non-public information known to the relator. The relator alleged that one of the defendants, PharMerica—an owner and operator of institutional pharmacies serving nursing homes—”unlawfully discounted prices for nursing homes’ Medicare Part A patients . . . in order to secure contracts to supply services to patients covered by Medicare Part D and Medicaid.” Id. at 81. The district court determined that “various reports cumulatively disclosed the alleged fraudulent transactions,” including guidance from the Department of Health and Human Services, publicly available reports discussing the institutional pharmacy market generally, and PharMerica’s 10-k financial disclosures, which the relator admitted provided the “information needed to deduce the fraud.” Id. at 85, 93 (emphasis in original).

The Third Circuit held that the key question is whether “a relator’s non-public information permits an inference of fraud that could not have been supported by the public disclosures alone.” Id. at 86. In the context at issue, the court held that a general report on fraud within a particular industry, standing alone is inadequate to trigger the public disclosure bar because it “merely indicate[s] the possibility that such a fraud could be perpetrated” in that industry. Id. The court elaborated that “the FCA’s public disclosure bar is not triggered when a relator relies upon non-public information to make sense of publicly available information where the public information—standing alone—could not have reasonably or plausibly supported an inference that the fraud was in fact occurring.” Id. at 89.

The court clarified that it is the responsibility of the court to “determine whether the publicly available documents in fact disclosed information sufficient to raise the inference of fraud.” Id. at 93 (emphasis in original). “[A] relator’s subjective belief that he relied upon certain information is immaterial to the court’s decision [on whether there was a prior public disclosure], which must be based on an independent assessment of the scope of the information disclosed by the public documents.” Id. Thus, a relator’s admission that “he relied upon certain public documents to deduce [the alleged] fraud” has no bearing on the analysis of whether public documents “disclose the fraud in sufficient detail.” Id. at 92–93.

G. Several Circuits Narrow Scope of Liability for FCA Retaliation Claims

Several circuits this year tightened the range of circumstances under which an employee or former employee may successfully recover under the FCA’s anti-retaliation provision, which entitles employees, contractors, and agents of an employer to relief if they are “discharged, demoted, suspended, threatened, harassed, or in any other manner discriminated against in the terms and conditions of employment because of lawful acts done by the employee”

in furtherance of the FCA. 31 U.S.C. § 3730(h)(1).

1. The Tenth Circuit Addresses “Constructive Knowledge” and “Cat’s Paw” Theories of Liability, and Limits Retaliation Claims to Retaliation that Occurs During Employment

Two recent Tenth Circuit decisions have placed significant limitations on retaliation claims. In Armstrong v. The Arcanum Group, Inc., 897 F.3d 1283 (10th Cir. 2018), the court rejected a former employee’s retaliation claim against a government contractor on summary judgment because there was insufficient circumstantial evidence to prove that the employee’s supervisor either directly knew of her complaints, id. at 1288–89, or had “constructive knowledge” of her complaints. Id. at 1289. Notably, the court explained that constructive knowledge could not be imputed based on a theory of deliberate ignorance because the supervisor actively tried to learn why the client agency was unhappy with the employee’s performance, but was “rebuffed.” Id. at 1289. The court also rejected the plaintiff’s argument that another “management-level” employee’s knowledge of the relator’s complaint should be imputed to her supervisor, holding that “the knowledge of someone who had no role in the [termination] decision is irrelevant to the motive for the decision.” Id. at 1290.

Finally, the court rejected the employee’s attempt to import a “cat’s paw” theory of liability from other discrimination jurisprudence—which would establish liability on the part of an employer who “uncritically relies on [a] biased subordinate’s reports and recommendations in deciding to take adverse employment action.” Id. at 1290 (internal citation omitted). While the Tenth Circuit held that the facts of the case did not support such a theory, it left open the question of whether such a theory could support a retaliation claim under the FCA under a different set of facts. Id. at 1291.

In Potts v. Center for Excellence in Higher Education, Inc., 908 F.3d 610 (10th Cir. 2018), the Tenth Circuit affirmed a dismissal for failure to state a claim and held that a former employee does not have a cause of action against an employer for “retaliation” that allegedly occurs after the employee is no longer employed. The court held that the term “employee,” as it is used in the FCA, “includes only persons who were current employees when their employers retaliated against them.” Id. at 614. As such, the FCA’s anti-retaliation provision “unambiguously excludes relief for retaliatory acts occurring after the employee has left employment.” Id. at 618.

2. The Fourth Circuit Joins Majority of Circuits in Adopting “But For” Causation Standard

A growing number of circuits that have held that whatever their respective approaches might have been previously, the Supreme Court’s decisions in Gross v. FBL Financial Services., Inc. 557 U.S. 167 (2009) and University of Texas Southwest. Medical Center. v. Nassar, 570 U.S. 338 (2013) mandate a “but for” standard of causation in FCA retaliation cases—meaning a plaintiff must show that he would not have faced adverse employment action “but for” his alleged protected activity. See, e.g., DiFiore v. CSL Behring, LLC, 879 F.3d 71, 77–78 (3d Cir. 2018); United States ex rel. King v. Solvay Pharm., Inc., 871 F.3d 318, 333 (5th Cir. 2017); United States ex rel. Marshall v. Woodward, Inc., 812 F.3d 556, 564 (7th Cir. 2015).

In United States ex rel. Cody v. ManTech International, Corp., No. 17-1722, 2018 WL 3770141 (4th Cir. Aug. 8, 2018), the Fourth Circuit followed suit by relying on Gross and Nassar to adopt—albeit in an unpublished decision—a “but for” causation standard for retaliation claims under the FCA. Prior to Cody, it was an “open question” in the Fourth Circuit whether retaliation claims proceeded under a “but for” standard of causation or under the more lenient “contributing factor” standard. Id. at *7. Moving forward, however, there is little reason to believe the “but for” standard announced in Cody will not prevail.

V. CONCLUSION

As always, Gibson Dunn will continue to monitor developments in the ever-changing and high-stakes FCA space and stands ready to answer any question you may have. We will report back to you on the latest news mid-year, in early July.

[1] State Farm Fire & Cas. Co. v. United States ex rel. Rigsby, 137 S. Ct. 436 (2016); Universal Health Servs., Inc. v. United States ex rel. Escobar, 136 S. Ct. 1989 (2016); Kellogg Brown & Root Servs., Inc. v. United States ex rel. Carter, 135 S. Ct. 1970 (2015); Schindler Elevator Corp. v. United States ex rel. Kirk, 563 U.S. 401 (2011); Graham Cnty. Soil & Water Conservation Dist. v. United States ex rel. Wilson, 559 U.S. 280 (2010); United States ex rel. Eisenstein v. City of New York, New York, 556 U.S. 928 (2009); Allison Engine Co. v. United States ex rel. Sanders, 553 U.S. 662 (2008).

[2] See Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Justice Department Recovers Over $2.8 Billion from False Claims Act Cases in Fiscal Year 2018 (Dec. 21, 2018),

https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-recovers-over-28-billion-false-

claims-act-cases-fiscal-year-2018 [hereinafter DOJ FY 2018 Recoveries Press Release].

[3] See U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Fraud Statistics Overview (Dec. 21, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/civil/page/file/1080696/download?utm_medium=email&

utm_source=govdelivery [hereinafter DOJ FY 2018 Stats].

[4] See Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Acting Assistant Attorney General Stuart F. Delery Speaks at the American Bar Association’s Ninth National Institute on the Civil False Claims Act and Qui Tam Enforcement (June 7, 2012), http://www.justice.gov/iso/opa/civil/speeches/2012/civ-speech-1206071.html.

[5] See Memorandum, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Factors for Evaluating Dismissal Pursuant to 31 U.S.C. 3730(c)(2)(A) (Jan. 10, 2018), https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/4358602/Memo-for-

Evaluating-Dismissal-Pursuant-to-31-U-S.pdf.

[6] See Memorandum, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Limiting Use of Agency Guidance Documents In Affirmative Civil Enforcement Cases (Jan. 25, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/file/1028756/download.

[7] See Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Department of Justice Announces the Rollout of an Updated United States Attorneys’ Manual (September 25, 2018),

https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/department-justice-announces-rollout-updated-united-

states-attorneys-manual

[8] U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Justice Manual, Section 4-4.111, U.S. Dep’t of Justice,

https://www.justice.gov/jm/jm-4-4000-commercial-litigation#4-4.111.

[9] Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae at 15, Gilead Sciences., Inc. v. United States ex rel. Campie, No. 17-936, 2018 WL 6305459 (U.S. Sup. Ct. Nov. 30, 2018).

[10] See United States’ Mot. to Dismiss Relator’s Second Am. Compl., United States ex rel. Health Choice Grp., LLC v. Bayer Corp., Onyx Pharm., Inc., Amerisourcebergen Corp., & Lash Grp., No. 5:17-CV-126-RWS-CMC (E.D. Tex. Dec. 17, 2018).

[11] Id. at 3, 14.

[12] Id. at 8, 14.

[13] Id. at 16.

[14] See Rod J. Rosenstein, U.S. Deputy Attorney General, Remarks at the American Conference Institute’s 35th International Conference on the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (November 29, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/deputy-attorney-general-rod-j-rosenstein-

delivers-remarks-american-conference-institute-0 (emphasis added).

[15] Id.

[16] U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs.—Office of Inspector Gen., Fraud Risk Indicator,

https://oig.hhs.gov/compliance/corporate-integrity-agreements/risk.asp.

[17] Alison Frankel, AG nominee Barr to back off previous attack on antifraud law: source, Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-trump-barr/ag-nominee-barr-to-back-off-previous-attack-on-antifraud-law-source-idUSKCN1OW1TJ.

[18] See DOJ FY 2018 Recoveries Press Release.

[19] See Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Drug Maker Actelion Agrees to Pay $360 Million to Resolve False Claims Act Liability for Paying Kickbacks (Dec. 6, 2018),

https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/drug-maker-actelion-agrees-pay-360-million

-resolve-false-claims-act-liability-paying.

[20] See Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, AmerisourceBergen Corporation Agrees to Pay $625 Million to Resolve Allegations That it Illegally Repackaged Cancer-Supportive Injectable Drugs to Profit from Overfill (Oct. 1, 2018),

https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/amerisourcebergen-corporation-agrees-pay-625-million-

resolve-allegations-it-illegally.

[21] See Nate Raymond & Andy Thibault, Insys to pay $150 million to settle U.S. opioid kickback probe, Reuters (Aug. 8, 2018), https://www.reuters.com/article/us-insys-opioids/insys-to-pay-150-

million-to-settle-u-s-opioid-kickback-probe-idUSKBN1KT1G5.

[22] See Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Hospital Chain Will Pay Over $260 Million to Resolve False Billing and Kickback Allegations; One Subsidiary Agrees to Plead Guilty (Sept. 25, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/hospital-chain-will-pay-over-260-million-

resolve-false-billing-and-kickback-allegations-one.

[23] See Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Medicare Advantage Provider to Pay $270 Million to Settle False Claims Act Liabilities (Oct. 1, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/medicare-advantage-provider-pay-270-million-settle-false-

claims-act-liabilities.

[24] See Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Hospital Chain Will Pay Over $260 Million to Resolve False Billing and Kickback Allegations; One Subsidiary Agrees to Plead Guilty (Sept. 25, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/hospital-chain-will-pay-over-260-

million-resolve-false-billing-and-kickback-allegations-one.

[25] See Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Detroit Area Hospital System to Pay $84.5 Million to Settle False Claims Act Allegations Arising From Improper Payments to Referring Physicians (Aug. 2, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/detroit-area-hospital-system-

pay-845-million-settle-false-claims-act-allegations-arising.

[26] See Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Health Quest and Putnam Hospital Center to Pay $14.7 Million to Resolve False Claims Act Allegations (July 9, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/health-quest-and-putnam-hospital-center-pay-147-million-

resolve-false-claims-act-allegations.