The State of Louisiana Is Granted Primacy Over Class VI Wells

Client Alert | January 8, 2024

The final rule marks a significant transition in the regulatory oversight of the carbon capture and sequestration industry within Louisiana.

On December 28, 2023, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) signed a final rule giving the State of Louisiana primary enforcement authority (or “primacy”) over Class VI underground injection wells, which are used by the carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) industry to permanently sequester captured carbon in underground geological formations, within the state.[1] The final rule represents a long-sought and important win for Louisiana, which initially submitted its application for Class VI primacy to the EPA on September 17, 2021.[2] It also marks a significant transition in the regulatory oversight of the CCS industry within Louisiana, as the primary regulatory body for the CCS industry in the state shifts from the EPA to the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources (LDNR).[3] The Class VI permitting process under the LDNR is expected to be faster than the process under the EPA, leading to accelerated growth of the CCS industry within Louisiana. Louisiana now joins North Dakota and Wyoming among states with Class VI primacy.

Class VI Wells, Primacy and Federal Incentives

Class VI underground injection wells are specifically designed for the permanent geological sequestration of carbon dioxide, playing a crucial role in CCS technologies aimed at mitigating climate change.[4] Geological sequestration involves injecting captured carbon dioxide into underground rock formations, such as in deep saline formations, at depths and pressures high enough to keep the carbon dioxide in a supercritical fluid phase, which allows more carbon dioxide to be sequestered and is less likely to lead to the carbon dioxide escaping into the atmosphere or migrating into other underground formations.[5] Class VI wells are distinct from other injection wells in that they are exclusively dedicated to long-term storage of carbon dioxide that is either captured directly from the ambient atmosphere (in direct air capture CCS projects) or from industrial emissions or other anthropogenic sources (in point source CCS projects).

Federal income tax credits are available under the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (IRA) for the capture and utilization or sequestration of qualified carbon oxides (see our previous alert here). Significantly greater credits are awarded for “secure” geological sequestration of carbon oxides, and Class VI wells generally satisfy IRS and Treasury requirements for such secure sequestration. The IRA further enhanced the economic benefit of these credits by making it easier to monetize them, extending the benefit of new direct payment (see our previous client alert here) and transferability (see our previous client alert here) rules to these credits. Additional federal funding for CCS projects was also made available under the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.[6]

Class VI wells are subject to stringent regulations under the Safe Drinking Water Act’s Underground Injection Control (UIC) program. Under the Act, the EPA is responsible for developing UIC requirements for injection wells of all classes that are intended to protect underground sources of drinking water, among other objectives. Any state, territory, or tribe can obtain primary enforcement authority over a given class of injection wells by adopting injection well requirements that are at least as stringent as the EPA’s requirements and subsequently applying to the EPA for primary enforcement authority over that class of injection well.[7] If the EPA approves the primacy application, the state, territory, or tribe will then implement and manage the permitting and compliance processes for the applicable class of injection well. However, if a state, territory, or tribe does not adopt its own injection well requirements or apply for enforcement authority over a given class of wells, then the EPA will remain responsible for implementing and enforcing the UIC requirements for that class of wells.

Permitting Backlog at the EPA Driving Interest in Class VI Primacy

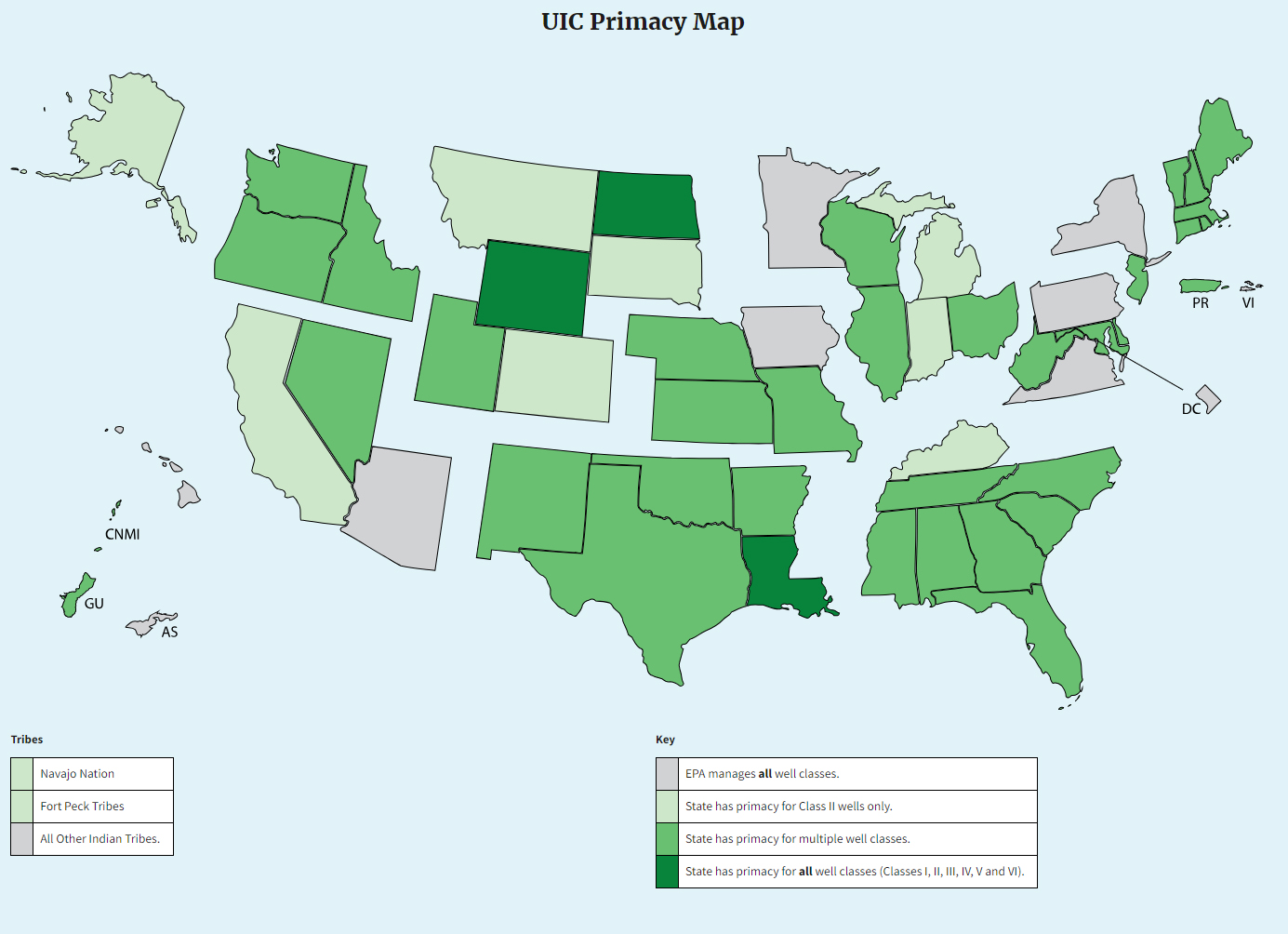

As shown in the map below, many states have been granted primacy by the EPA over multiple classes of injection wells, particularly Class II injection wells, which can be utilized for CCS projects utilizing captured carbon for enhanced oil recovery projects.[8] However, prior to Louisiana, only North Dakota and Wyoming had successfully applied for primacy over Class VI wells. As a result, the EPA retains oversight over nearly all Class VI well permit applications in the US.

As of 1/1/24. Source: The United States Environmental Protection Agency

The EPA’s process for granting a Class VI well permit is rigorous and requires applicants to provide extensive (and expensive) data and modeling to show that the Class VI well will protect drinking water and prevent the escape or migration of carbon dioxide.[9] Although the EPA currently estimates that the Class VI permitting process for new permits will take about 25 months from start to finish, some Class VI permits have taken as long as six years to be approved.[10]

The EPA has also issued very few Class VI permits, leading to a backlog of pending permit applications. As of January 1, 2024, the EPA has only issued six Class VI permits, all for projects in Illinois, and of those six permits, only two have been utilized in connection with an active CCS project.[11] The EPA is nearing final approval of six additional Class VI well permits for CCS projects in Indiana and California, but these represent a fraction of the pending Class VI well permit applications before the EPA.[12] As of December 22, 2023, there were 63 permit applications covering 179 wells at some point in the EPA’s permitting process, and most applications are not close to approval, as shown in the attached CHART. (As of 12/22/23. Source: The United States Environmental Protection Agency.)

The permitting backlog at the EPA is one of the reasons Louisiana sought primacy over Class VI wells. Of the 63 pending permit applications before the EPA, approximately one-third were for CCS projects located in Louisiana, and the lengthy approval process was a major impediment to CCS projects in the state. Now that Louisiana has obtained primacy over Class VI wells, all pending permits before the EPA will be transferred to the LDNR for review, and the LDNR will have oversight of all future Class VI well applications in Louisiana. Many CCS industry participants have welcomed the switch to the review process under the LDNR, which is expected to be more efficient and to take a shorter period of time than the EPA’s process, a belief which is supported by the Class VI permit process in North Dakota, which has produced eight Class VI permits since North Dakota obtained Class VI primacy in 2018 (compared to the six Class VI well permits issued by the EPA nationwide since the UIC program was implemented in 2010).[13]

Class VI Requirements Adopted by Louisiana

The Class VI well requirements adopted by Louisiana are more stringent than the EPA’s requirements in several key areas, including:

- requiring each individual Class VI well to be reviewed and permitted on its own, rather than issuing permits for multiple wells in a given project at once;

- prohibiting the sequestration of carbon dioxide in salt caverns;

- not granting waivers to injection depth requirements; and

- requiring additional monitoring systems and operating requirements, over and above those required by the EPA.[14]

In addition, the EPA included several environmental justice requirements in the Memorandum of Agreement between Louisiana and the EPA, including an environmental justice review process. These requirements include:

- adding steps to enhance the public’s participation in the permit application process;

- analyzing environmental justice impacts on communities as part of the permitting process, including identifying environmental hazards, potential exposure pathways, and susceptible populations; and

- incorporating mitigation measures to ensure Class VI wells do not increase environmental impacts and public health risks in already overburdened communities, such as installing carbon dioxide monitoring networks, carbon dioxide release networks, and enhanced pollution controls.[15]

Class VI applications before LDNR for review will need to be evaluated to ensure that they comply with Louisiana’s enhanced regulations and environmental justice requirements, and companies with pending Class VI applications that will be transferred to the LDNR may need to amend their applications if they do not meet these requirements.

Additional States Seeking Class VI Primacy

Louisiana’s successful primacy application over Class VI wells is likely to encourage other states to apply for Class VI primacy. Currently, only Texas, West Virginia, and Arizona are actively seeking Class VI primacy, but all three states are in the early stages of the primacy application process and are not expected to be given primacy in the near future.[16] Texas, for example, consolidated jurisdiction for Class VI wells under the Railroad Commission of Texas (RRC) in 2021 and submitted its formal application for primacy on December 19, 2022.[17] The EPA has reviewed Texas’s application for completeness, but the EPA still considers Texas to be in the “pre-application activities” phase of the primacy application process.[18] The RRC has adopted several amendments to the Texas Administrative Code to meet the EPA’s Class VI requirements, and the RRC submitted its final rules to the EPA in August 2023.[19]

States that seek Class VI primacy should pay close attention to Louisiana’s application for guidance on how to approach the primacy application process, especially with respect to the environmental justice requirements, as the EPA has indicated that Louisiana’s environmental justice commitments are a clear benchmark for any state that seeks Class VI primacy in the future.[20]

Conclusion

The recent signing of the final rule granting the State of Louisiana primary enforcement authority over Class VI wells signals a pivotal moment in the regulation of the CCS industry. This achievement, following a protracted application process, not only provides Louisiana with autonomy in overseeing Class VI wells but also signifies a significant shift from federal EPA oversight to the LDNR. With expectations of a more expedited and efficient permitting process under the LDNR, the decision is poised to catalyze accelerated growth in the CCS industry within the state.

[2] Id.

[3] https://gov.louisiana.gov/index.cfm/newsroom/detail/4372

[4] https://www.epa.gov/uic/class-vi-wells-used-geologic-sequestration-carbon-dioxide

[5] “Sequestration of Supercritical CO2 in Deep Sedimentary Geological Formations”, Negative Emissions Technologies and Reliable Sequestration: A Consensus Study Report of The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, pg. 320.

[8] The Underground Injection Control program consists of six classes of injection wells. Each well class is based on the type and depth of the injection activity, and the potential for that injection activity to result in endangerment of an underground source of drinking water (USDW). Class I wells are used to inject hazardous and non-hazardous wastes into deep, isolated rock formations. Class II wells are used exclusively to inject fluids associated with oil and natural gas production. Class III wells are used to inject fluids to dissolve and extract minerals. Class IV wells are shallow wells used to inject hazardous or radioactive wastes into or above a geologic formation that contains a USDW. Class V wells are used to inject non-hazardous fluids underground. Class VI wells are wells used for injection of carbon dioxide into underground subsurface rock formations for long-term storage, or geologic sequestration.

[9] https://www.epa.gov/uic/class-vi-wells-used-geologic-sequestration-carbon-dioxide#ClassVI_PermittingProcess

[10] Observations on Class VI Permitting: Lessons Learned and Guidance Available, Bob Van Voorhees et al. at 3 (https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/items/117640); see EPA Permit Tracker Chart.

[11] Id.; https://www.epa.gov/uic/table-epas-draft-and-final-class-vi-well-permits.

[12] https://www.epa.gov/uic/table-epas-draft-and-final-class-vi-well-permits.

[13] https://www.dmr.nd.gov/dmr/oilgas/ClassVI.

[15] Id.

[16] Id.

[20] Id.

Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have about these developments. To learn more, please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, any leader or member of the firm’s Oil and Gas, Tax, or Environmental Litigation and Mass Tort practice groups, or the authors:

Oil and Gas:

Michael P. Darden – Houston (+1 346.718.6789, mpdarden@gibsondunn.com)

Rahul D. Vashi – Houston (+1 346.718.6659, rvashi@gibsondunn.com)

Graham Valenta – Houston (+1 346.718.6646, gvalenta@gibsondunn.com)

Tax:

Michael Q. Cannon – Dallas (+1 214.698.3232, mcannon@gibsondunn.com)

Matt Donnelly – Washington, D.C. (+1 202.887.3567, mjdonnelly@gibsondunn.com)

Josiah Bethards – Dallas (+1 214.698.3354, jbethards@gibsondunn.com)

Environmental Litigation and Mass Tort:

Stacie B. Fletcher – Washington, D.C. (+1 202.887.3627, sfletcher@gibsondunn.com)

David Fotouhi – Washington, D.C. (+1 202.955.8502, dfotouhi@gibsondunn.com)

Rachel Levick – Washington, D.C. (+1 202.887.3574, rlevick@gibsondunn.com)

© 2024 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP. All rights reserved. For contact and other information, please visit us at www.gibsondunn.com.

Attorney Advertising: These materials were prepared for general informational purposes only based on information available at the time of publication and are not intended as, do not constitute, and should not be relied upon as, legal advice or a legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances. Gibson Dunn (and its affiliates, attorneys, and employees) shall not have any liability in connection with any use of these materials. The sharing of these materials does not establish an attorney-client relationship with the recipient and should not be relied upon as an alternative for advice from qualified counsel. Please note that facts and circumstances may vary, and prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome.