April 3, 2020

Spring 2020 effectively brought us two Budgets. There was the “core” Budget delivered on 11 March, setting out medium-term tax and spending plans, and then there has, in effect, been an emergency Budget aimed at dealing with the immediate potential consequences of the COVID-19 coronavirus.

All of the economic forecasts on which the core Budget was based were put together before any significant effects of the COVID-19 coronavirus were fully accounted for, and were therefore essentially out of date at the moment of publication. With recent developments, it is now apparent that the short-term disruption first envisaged will not be short-term at all. The significant longer-term effects will almost certainly be felt in a period of deep economic recession, with many predictions of a considerable shrinking of the UK economy in the second quarter of this year at least, and will likely mean the tax and spending plans set out on 11 March 2020 will lead to an even bigger deficit in the first few years of this decade (at least). It is, however, too early to meaningfully comment on the full long-term effects of the COVID-19 coronavirus.

This alert, therefore, aims to update clients on various key tax-related announcements and developments in Q1 2020 that we consider will be of most interest, mainly unrelated to the COVID-19 coronavirus (including the key proposals in the “core” 2020 Budget).

For our client alert on tax measures in respect of the COVID-19 coronavirus, please see EU Economic and Fiscal Measures.

We hope that you find this alert useful. Please do not hesitate to contact us with any questions or requests for further information.

Table of Contents

A. UK Budget 2020

- Review of UK funds regime, including consultation on the tax treatment of asset holding companies in alternative investment fund structures

- VAT treatment of financial services

- Changes to Entrepreneurs’ Relief lifetime limit for capital gains tax

- Consultation on hybrid mismatch rules

- Notification of uncertain tax treatments for large businesses

- Tax consequences of IBOR-discontinuation

- Real estate-specific updates

- Digital Services Tax

B. Other Significant Developments

- International Tax Enforcement (Disclosable Arrangements) Regulations 2020 (DAC6) update

- COVID-19 coronavirus and internationally mobile workers

- Cayman Islands added to EU list of “non-cooperative jurisdictions”

C. Recent Notable Cases

- Melford Capital General Partner v Revenue and Customs Commissions

- Blackrock Investment Management (UK) Limited v United Kingdom

- Assem Allam v HMRC

- Walewski v HMRC

A. UK Budget 2020

I. Review of the UK funds regime, including consultation on the tax treatment of asset holding companies in alternative investment fund structures

| In the course of 2020, the UK government has committed to undertake a review of the UK’s funds regime. In addition to regulatory matters, the direct and indirect taxes to which funds are subject will be considered, “with a view to considering the case for policy changes”. This will include a review of the VAT treatment of fund management fees (as to which, see below), and a consultation regarding the tax treatment of intermediate fund entities (rather than fund vehicles themselves). |

The aim of the consultation on intermediate fund entities is to “gather evidence and explore the attractiveness of the UK as a location for intermediate entities through which alternative funds hold assets”. “Alternative funds”, for this purpose, means funds that are “not subject to investor protection regulation” – generally being “closed-end funds that raise capital from sophisticated investors [typically pension funds, insurance companies and sovereign wealth funds]…and invest in…higher risk assets”.

According to the government, the consultation (which will run until 20 May 2020) is a response to representations from the fund industry that there are “barriers to the establishment of these intermediate fund entities in the UK”. Some of the issues cited are specific to particular kinds of funds, while others are more general in nature:

- Credit funds:

- Distribution treatment for results-dependent interest (including issues in structuring back to back lending arrangements, where returns are intended to track underlying instruments); and

- The relative narrowness of the UK’s securitisation regime;

- Real estate funds:

- The trading condition to the UK’s capital gains participation exemption (the so-called “substantial shareholding exemption”); and

- Relatively stringent conditions to accessing the UK REIT regime;

- Private equity:

- Income treatment on the distribution by intermediate holding companies to funds of disposal proceeds from the sale of underlying assets (in particular in the context of share buybacks); and

- General:

- Administrative burdens in qualifying for exemption from interest withholding tax; and

- The application of hybrid-mismatch rules to exempt fund investors, and difficulties arising from investors being treated as “acting together” for the purposes of the rules.

The government has confirmed that it is prepared to make legislative changes in response to the consultation, and expressly notes that while it is open to adopting isolated changes, it would also consider a more comprehensive overhaul of the regime. However, there are limits on how far it is willing to go. The consultation stresses (a) that the government is not willing to make changes which would take income or gains outside the scope of UK tax in a manner which is “inconsistent with the overall principles of the UK tax system” and (b) that any such changes must be compatible with the UK’s international obligations under the OECD BEPS project and the UK’s obligations in respect of state aid.

In particular, it is worth noting that the government has called for evidence of how the UK’s regime compares to other jurisdictions, and whether/how the problems identified in the UK are addressed elsewhere. This may perhaps indicate that the UK government’s inclination is to match, but go no further than, its competitors. Although not expressly mentioned, an example which will surely inform their thinking is Luxembourg, which has a mature and generous regime for intermediate holding companies (featuring no withholding tax on interest, and a broad participation exemption for dividends and capital gains) and a well-functioning supporting infrastructure. Following the wide-spread adoption of the OECD’s Multilateral Instrument (with its principle purpose test and ever more stringent substance requirements), the trend within the funds industry has been to accumulate holding vehicles in a single jurisdiction, in order to achieve a critical mass. If the UK wishes to compete with, and lure funds away from, Luxembourg and other investment hubs, it is hoped that the government will be ambitious in its thinking.

II. VAT treatment of financial services

Wider exemption for SIF management

| The UK government has published legislation providing for a wider VAT exemption for the management of so-called “Special Investment Funds” (“SIFs”). Conditions for close-ended collective investment undertakings (“CECIVs”) will be relaxed, and an existing concession for defined contribution pension funds will be codified. |

Currently, the exemption for SIFs applies to the management of open ended investment companies, authorised unit trusts and any similar collective investment undertakings competing in the UK retail market (including CECIVs) . However, the management of CECIVs is currently exempt only if its sole object is “the investment of capital, raised from the public, wholly or mainly in securities”.

The new legislation, which takes effect from 1 April 2020, broadens the fund management exemption on two fronts:

- A concession applying to the management of “qualifying pension funds”, which has been in place since 2014, will now be put on legislative footing. The exemption will now apply to the management of funds meeting the following conditions:

- The pension fund must be established in the UK or an EU member state, and funded solely (either directly or indirectly) by the pooled contributions of those entitled to benefit from distributions from the pension fund (so-called “members”); and

- The members must bear investment risk, which must be spread over a range of investments. Accordingly, the exemption would not apply to the management of defined benefit, as opposed to defined contribution, pension schemes.

- To qualify for the exemption, CECIVs will no longer need to invest “wholly or mainly in securities”. This change is timely, in light of the recent AG opinion in Blackrock Investment Management (UK) Limited v. United Kingdom C-231/19 (discussed below). If apportionment of consideration between exempt and non-exempt supplies proves not to be possible, the UK’s move to widen what constitutes a SIF may increase the likelihood of mixed supplies being characterised as predominantly exempt. Whether that is good news, or bad, will depend on the circumstances of the particular taxpayer.

Review of VAT treatment of fund management fees and financial services

| As part of a broader review of the UK funds regime, the UK government intends to “consider the VAT treatment of fund management fees”. In addition, an industry working group “to consider the VAT treatment of financial services” more generally will be created. |

No detailed information has yet been published regarding the precise issues to be considered as part of this review.

EU laws already give member states relatively broad latitude regarding the scope of the VAT exemption for fund management, by granting discretion in determining what constitutes a “SIF” (as to which, see further above). However, the above could suggest that the UK intends to implement a more wide-ranging overhaul. It remains to be seen whether, in a bid to maintain its attractiveness as a location for fund management and financial services, the UK will (at the end of the Brexit transitional period) exercise its new freedom to depart from EU VAT rules. Whatever route is chosen, it is hoped that the government will be mindful of the potential compliance burden for pan-European businesses in navigating different regimes, and that any changes will be either easy to administer, or sufficiently material to outweigh such hindrance.

III. Changes to Entrepreneurs’ Relief Lifetime Limit for Capital Gains Tax

| After much speculation in the run up to the Budget, Entrepreneurs’ Relief (“ER”) escaped abolition. However, its utility has been much reduced, via an immediate reduction in the lifetime limit from £10 million to £1 million. As changes to the scope of the relief were widely expected, special measures have been introduced to defeat planning done in anticipation. |

In practical terms, the changes will result in a reduction of the maximum relief available from £1 million to £100,000 for individuals who realise gains that qualify for ER (i.e. in view of the 10% rate of capital gains tax that applies in respect of the lifetime limit when the conditions are met).

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the measure is the timing of its introduction. The changes will affect disposals taking place on or after 11 March 2020, allowing no time for planning. Generally, those who completed sales to unconnected buyers before 11 March 2020 should be able to benefit from the higher lifetime limit. However, this is subject to an important qualification: those who entered into uncompleted sale contracts or certain share exchanges pre-Budget in an attempts to circumvent expected changes to the relief may fall foul of anti-forestalling provisions, and be denied the benefit of the higher lifetime limit.

As a general rule, the time of disposal for capital gains purposes is the time when the contract for sale becomes unconditional (rather than the time of completion). Parties to an uncompleted pre-11 March 2020 sale contract will be subject to the £1 million lifetime limit unless they can demonstrate (a) that no purpose of entering into the contract was to take advantage of this timing rule (in order to circumvent the widely reported narrowing of ER) and, (b) in the case of connected parties, that the contract was also entered into for wholly commercial reasons.

In addition, where shares have been exchanged for those in another company in the period from 6 April 2019 to (and including) 10 March 2020, and an election to crystallise the gain on the exchange (rather than adopt rollover treatment) is made on or after 11 March 2020, the new lifetime limit will apply if, broadly, either:

- the companies whose shares are exchanged are under common control; or

- the consequence of the exchange is that the exchanging shareholders’ proportionate shareholding is increased, and qualifies for ER.

In many ways, it is unsurprising that the Chancellor has opted to reduce the significant cost of the relief, which was £2.3 billion in 2017/18. ER has been a politically unpopular measure among certain sectors of the general electorate, with its benefit concentrated amongst the relatively small pool of persons making material gains. The surprise is perhaps that its scope was limited only after, and not before, the election.

Historically, a significant element of acquisition structuring in the private equity sphere has involved ensuring that target management can benefit from ER on exit. Now that the value of such structuring has been materially diluted, it will be for buyers to decide whether the time and energy such planning requires is still justified. This will likely be a question to be answered on a case by case basis.

As an aside, it’s also worth noting that it has been proposed that ER in its new form will be known as “business asset disposal relief” – a move that has drawn criticism from some quarters on the basis that it does not accurately describe the nature of the relief and may lead to taxpayer confusion.

IV. Consultation on UK hybrid mismatch rules

| The UK was an early adopter of the OECD’s proposals on countering hybrid mismatch arrangements, introducing a “gold-plated” domestic regime in 2017 (which in some instances went beyond the BEPS proposals). The mechanical operation of these rules has, however, resulted in unexpected material disallowances for some taxpayers. This is particularly true in the context of US multinationals with UK “check the box” entities – even where there is no UK tax advantage being obtained. A consultation on certain technical aspects of the hybrid rules has been launched, providing a welcome opportunity for taxpayers to engage with the government to ensure that the rules work proportionately and as intended. However, it should be noted that the consultation only addresses certain issues with the rules, and other problems and uncertainties remain unresolved for now (including, for example, the interaction of the rules with other parts of the UK tax code dealing with the deductibility of payments, and how the rules might be applied to entities with special tax status, such as UK securitisation companies). |

The consultation on the UK hybrid mismatch rules focuses on three areas, as set out below.

Double deduction mismatches

Expenses deducted twice (either in two jurisdictions or by more than one taxpayer) in relation to arrangements where a hybrid entity is involved – for example, where expenses are both deductible for a US parent company and a subsidiary company in the UK treated as a disregarded entity for US federal income tax purposes – may trigger a counteraction under the UK hybrid mismatch rules, such that a UK tax deduction would be denied to a relevant UK entity within scope of the rules. However, no counteraction is required to the extent that the expenses are deducted from so-called “dual inclusion income”. This is broadly intended to refer to the same amounts of income brought into the charge to tax for different taxpayers. However, there are strict limits as to when amounts so brought into account would qualify. Despite changes made in 2018 (specifically, the introduction of section 259ID Taxation (International and Other Provisions) Act 2010), it is generally recognised that the double deduction rules can often apply more widely than they should, targeting genuinely commercial arrangements where there is no economic mismatch. This is largely due to their formulaic nature, which cannot comprehensively contemplate the nuances of particular non-UK laws. In contrast, the equivalent rules in other jurisdictions (notably Ireland) adopt a more substance-based approach, and seek to filter out arrangements where there is no egregious mismatch.

In addition, HMRC has acknowledged that the “fix” intended to be introduced by section 259ID Taxation (International and Other Provisions) Act 2010 – which broadly can treat amounts paid to an investor in a UK hybrid entity which are then paid on to the UK hybrid entity as dual inclusion income – is narrow in its application.

In the absence of amendments to the UK rules, many affected taxpayers would have no choice but to take laborious steps to restructure their operations only to preserve the same net economic outcome – something which may adversely impact long-term inbound investment into the UK. It seems that HMRC may have come to recognise this – although questions in the consultation regarding the barriers to such restructurings suggest that there may be limits on how far they are willing to go.

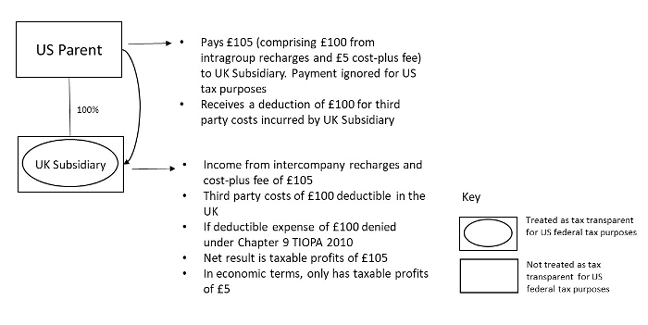

| The following example illustrates one scenario we have encountered that poses problems in connection with the double deduction rules (where section 259ID TIOPA 2010 does not obviously apply on the particular facts):

Potential issues:

|

Acting together

Broadly, in the absence of “structured arrangements”, the hybrid rules will only apply where parties to the arrangements are connected. In applying this test, parties who are “acting together” will be deemed to be connected. The purpose is to prevent otherwise unconnected parties from working together or being used to circumvent the effect of the rules. Nevertheless, the consultation acknowledges that the test can throw up practical difficulties (e.g. as a result of difficulties in obtaining sufficient information about counterparties’ structures to assess whether the deeming provisions apply). HMRC has therefore called for evidence of circumstances where taxpayers feel the impact of the deeming provisions should be modified. Fund structures may well provide ample raw material, with the risk of limited partners being considered to act together constituting a frequent cause of concern.

The consultation states that if the rules were tweaked to narrow the scope of the “acting together” provisions, the targeted anti-avoidance rules would apply to non-commercial arrangements put in place to benefit from the changes. Additionally, it would still be necessary for taxpayers to consider whether they may be party to “structured arrangements” (and hence still subject to the application of the rules).

Exempt investors in hybrid entities

An expense in a UK company would not typically be disallowed if the payment is made directly to an exempt investor (e.g. a pension fund or sovereign wealth fund). However, where the payment is indirectly made to such exempt investors (e.g. where the payment is made to a fund in which exempt investors are members) there is no equivalent general dispensation. This goes against the overarching intention of the UK tax system to achieve tax neutrality for collective investment, and unduly penalises exempt investors in fund structures featuring entities which are transparent in the UK and opaque in the investors’ jurisdiction. HMRC is consulting on options to improve the operation of the rules, e.g. a “white list” of entities which would not give rise to a counteraction.

V. Notification of uncertain tax treatments for large businesses

| From April 2021 large businesses will be required to notify HMRC when they take a tax position which HMRC is likely to challenge. |

The proposal is designed to improve HMRC’s ability to identify issues where businesses have adopted a different “legal interpretation” to HMRC’s view. This includes the interpretation of legislation, case-law and guidance. Taxes covered by the proposal include corporation tax, income tax (including PAYE), VAT, excise and customs duties, insurance premium tax, stamp duty land tax, stamp duty reserve tax, bank levy and petroleum revenue tax. Interestingly, one example given by HMRC of a scenario in focus is a disagreement regarding the accounting treatment of a transaction (which is of course different to “legal interpretation”).

The intention is to catch all such “uncertain tax positions”, irrespective of whether they derive from genuine uncertainty or “with the deliberate intention of pushing the boundaries of the law to their advantage”. There are, however, exceptions. Only “large” businesses (broadly expected to be those with a turnover above £200million and/or a balance sheet total above £2billion) will be within scope. Notification will not be necessary where (a) a transaction is disclosed under the Disclosure of Tax Avoidance Schemes rules or under DAC6 or (b) the uncertainty is the subject of formal discussion with HMRC or HMRC confirms that it already has sufficient information regarding the uncertainty. Similarly, (although not a formal exemption) HMRC would (unsurprisingly) not consider the rules to bite where they have previously provided clearance and there is no change in facts or circumstances. It is also proposed that uncertain tax treatments which, individually or combined, amount to a maximum of less than £1million in the tax outcome, will not be notifiable. In terms of practicalities, the administrative and penalty features of the regime will be similar to that of the Senior Accounting Office (“SAO”) regime. In particular, one individual within affected organisations will need to take personal responsibility for ensuring compliance (or potentially face personal penalties).

HMRC draws an analogy between the proposal and similar assessments which must be made for accounting purposes (namely in accordance with IFRIC23). It is notable, however, that (in contrast with the accounting-based obligations) uncertainty is defined by reference to the likelihood of HMRC, and not the courts, disagreeing. Comparisons are also made to existing notification obligations in the US and Australia. Those regimes, however, are more closely aligned with accounting judgments (as well as being narrower in scope and subject to higher thresholds regarding the tax at stake). Justification is, at least, offered for HMRC’s approach: the measure is, apparently, not intended to promote any assumption that HMRC’s interpretation is always correct, nor that HMRC is a final arbiter of disputes relating to tax law. HMRC’s intention is instead to identify areas of disagreement and accelerate discussions with taxpayers. It may, however, equally be construed as a wielding of soft power, and an addition to HMRC’s already substantial information gathering powers. It remains to be seen whether HMRC is leaning in its thinking towards more formal regulation of tax advisers, potentially raising interesting parallels with financial services regulation.

VI. Tax consequences of IBOR discontinuation

| It is expected that, from the end of 2021, London interbank offered rates (“LIBORs”), which are used as reference rates in the loan, bond and derivatives markets, will cease to be published. Instead, these rates are to be replaced with ‘nearly risk free’ benchmark rates (“RFRs”). Similar processes are occurring with other benchmark rates e.g. EONIA. The UK government has launched a consultation calling for information from taxpayers regarding “tax issues that arise from the reform of LIBOR and other benchmark rates”. |

The most significant tax concerns in respect of this transition relate to so-called “legacy contracts” – existing contracts with a term beyond the end of 2021 which will need to be amended to reflect the switch-over. It is generally accepted that, despite efforts to minimise resultant value transfers, they cannot be completely avoided. At the same time as the consultation document was released, HMRC published draft guidance addressing some of the resultant issues:

- Parties to legacy contracts that are subject to corporation tax are generally taxed in accordance with their accounts. The transition may result in amounts being recognised in the profit or loss statement for accounting purposes, either as a result of a “modification” to the instrument, or because the conditions to hedge accounting are no longer met. In addition, although not expressly mentioned by HMRC, increased hedge ineffectiveness going forward may also result in profit and loss recognition. Accounting relief may be available in respect of some of these impacts. However, if not, the draft guidance notes that “where amounts are recognised in the income statement, these will typically be brought into account for tax purposes”.

- For certain tax purposes, it is necessary to consider whether interest constitutes more than a reasonable commercial return (e.g. distribution provisions, grouping provisions, the stamp duty/SDRT loan capital exemption) or an arm’s length provision (e.g. transfer pricing). If this question had to be assessed by reference to prevailing rates at the time of amendment, the revised interest rate could fall foul of the relevant provisions. Helpfully, it seems that HMRC generally considers that these questions can be answered by reference to the position when the legacy contracts were first entered into.

- If sufficiently material, amendments could be treated as giving rise to the end of the legacy contract, and the creation of a new contract. This could jeopardise any grandfathering the taxpayer relies on, and require clearances obtained in respect of the legacy contract to be refreshed. The draft guidance indicates that generally, amendments won’t be treated as giving rise to new contracts.

However, for (b) and (c), the guidance indicates that favourable treatment will, to varying degrees, depend on the extent to which the amendments change the economics between the parties. This is particularly unhelpful in two regards: first, it introduces an element of value judgment and uncertainty and second, the degree of value transfer which HMRC considers acceptable seems to vary depending on the context (exacerbating the problem).

Although the guidance will go some way in easing taxpayer concerns regarding tax issues arising from benchmark transition, there are notable concerns on which the draft guidance is silent. Most significantly, the draft guidance (which is noted as applying only to businesses) does not confirm whether (for individuals, for example) amendments to contracts could give rise to a disposal for capital gains tax purposes. This will make it particularly difficult for those who have issued notes referencing LIBOR into retail markets to pursue consent-solicitation processes (to amend the notes). Moreover, timing remains an issue. Regulators have indicated that, generally, the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic will not impact the transition timetable, and financial institutions in particular are coming under increasing pressure from government bodies to amend legacy contracts. In the absence of final guidance from HMRC, taxpayers may be forced to do so without certainty of tax treatment.

The consultation document, the draft guidance and potential issues which are yet to be resolved will be discussed in further detail in an upcoming Gibson Dunn client alert.

VII. Real estate-specific updates

| For real estate, this year’s Budget is neither as hostile nor dramatic as previous years. Rather, with Budget 2020, HMRC seem (for the most part) to be content to tinker with existing measures. That has, in general, produced something of a mixed bag – with both good news, and bad, to be found. |

Structures and Buildings Allowance

Businesses that incur qualifying expenditure on the construction, renovation or conversion of non-residential structures and buildings on or after 29 October 2018 may claim Structures and Buildings Allowances (“SBA”). The annual rate of SBA will increase from 2% to 3% from 1 April 2020 for corporation tax purposes, and 6 April 2020 for income tax purposes. While the change is certainly modest, it is nevertheless welcome.

Corporation tax on non-UK resident companies with UK property income

Non-UK resident companies with UK property income have traditionally been liable to income tax – not corporation tax – on net rental profits. However, as previously announced, from 6 April 2020, these profits will instead become liable to corporation tax – with resulting differences in the applicable rates, computational rules, and payment and filing requirements.

Broadly, going forward:

- corporation tax will be levied at 19% (instead of the 20% rate of income tax);

- expenses of management should be deductible (which was not possible under the income tax rules);

- surrenders of losses between such non-residents and UK resident group members will now be possible;

- financing arrangements will be subject to the loan relationship rules, with net debits and credits being calculated separately before being set-off against rental profits.

There are, however, downsides, including potential restrictions on:

- the deduction of interest and other finance costs under the hybrid mismatch rules (if applicable) or the corporate interest restriction (which broadly limits deductions in excess of £2 million per group to 30% of EBITDA as a default position, subject to available exemptions and elections);

- the use of carried forward income and capital losses (which, cannot be set-off against more than 50% of profits exceeding £5 million in any year). However, pre-6 April 2020 property rental losses can still be carried forward for use against future profits without restriction.

More practically, existing income tax withholding provisions under the non-resident landlord scheme (the “NRLS”) will continue to apply, unless the non-UK resident company has permission to be paid gross (notwithstanding that amounts withheld will be within the corporation tax regime).

To facilitate a smooth transition to the new regime, changes announced in the Budget include a number of technical changes to the legislation facilitating the above changes. These include a new ability to obtain relief for financing costs incurred in the seven years prior to its carrying on a UK property business.

New Stamp Duty Land Tax surcharge for non-UK residents

From 1 April 2021, a 2% Stamp Duty Land Tax surcharge will apply where non-UK residents purchase residential property in England and Northern Ireland. The changes will impact non-UK resident trusts and companies, as well as individuals, and it is expected that commercial purchases of residential developments will be within scope. The change follows a consultation last year. More details about the proposed scope of the new measures will likely be available when the responses to the consultation are published later this year.

The rate increase is the most recent in a series of reactive moves by HMRC against non-residents investing in the UK property market. While it appears that the UK government is interested in seeking inward investment (as to which, see the forthcoming review of the funds regime mentioned above), the welcome will not, it seems, be extended to all equally. It remains to be seen whether the economic impact of the COVID-19 coronavirus, and the impending need to jump-start the economy thereafter, will result in a softening of HMRC’s stance. However, a U-turn seems unlikely.

Construction Industry Scheme domestic reverse charge

The construction industry scheme (“CIS”) requires contractors (including “deemed contractors”) to withhold tax from payments to their sub-contractors, and account for the money to HMRC. The amount withheld may then be applied against certain of the sub-contractors’ tax and national insurance contribution liabilities (potentially resulting in refund payments). The government is introducing measures which will tighten the evidentiary requirements sub-contractors will need to meet before deductions can be so applied against their tax and national insurance liabilities. Specifically, HMRC will reduce or deny the credit claimed by the sub-contractor against employment tax liabilities if the sub-contractor is unable to evidence the deductions. New measures will also simplify the rules covering those who are deemed to be contractors, clarify the rules on allowable deductions for expenditure on materials, and expand the scope of the penalty for supplying false information when registering for CIS. In addition, the government has published a consultation regarding the promotion of supply chain due diligence, including proposals for tackling fraud in supply chains.

HMRC clearly has abuse within the construction industry (whether real or perceived) within its sights. It has already consulted on measures for tackling fraud in the industry, resulting in the proposed VAT domestic reverse charge for building and construction services, although it is to be noted that the implementation of the reverse charge has been delayed until 1 October 2020 (and it remains to be seen whether it will be deferred again). It is to be hoped that any further measures taken are proportionate, and will not result in an excessive administrative burden for a sector which will likely suffer a significant downturn during the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic.

VIII. Digital Services Tax

The Finance Bill 2020 includes draft legislation in respect of the new 2% tax on revenues of large businesses that provide a social media service, search engine, or online marketplace to UK-based users. The UK digital services tax will apply from 1 April 2020.

The UK’s digital services tax will be discussed in detail in an upcoming Gibson Dunn client alert.

B. Other Significant Developments

I. International Tax Enforcement (Disclosable Arrangements) Regulations 2020 (DAC6) update

| Final regulations implementing DAC6 in the UK were published on 13 January 2020. DAC6, is the most recent EU reporting regime and requires promoters and “service provider” intermediaries to report details of certain cross-border tax arrangements that feature one or more “hallmarks”. Such arrangements are captured where the first implementation step was made on or after 25 June 2018, although first reporting will be due in August 2020. It is not clear whether the reporting timetable will be delayed because of the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. |

In January 2020, UK regulations implementing Directive (EU) 2018/822 (the “Directive”) were published. Even though the UK has officially left the EU, it is still legally obliged to implement the EU Directive properly and, therefore, the scope of the UK rules closely follows that of the EU Directive. Any deviation from this would mean the UK would not meet its international obligations and could also lead to potential differences in the approaches of the UK and other countries.

The government has acknowledged that the Directive is wide and HMRC has, in some instances, indicated a willingness to take helpful positions (where the wording of the Directive allows). This is reflected in some interpretations adopted by HMRC in draft guidance (most recently published in March) . However, such guidance does not carry the force of law and is not binding on HMRC. It will only – at best – outline HMRC’s (current) interpretation of the rules and provide insight into HMRC’s (current) practical approach to the regulations. While it can, of course, be useful, it should be treated with caution.

As there is no legislative framework for taxpayers to exercise any control over the information which is reported by intermediaries, taxpayers may wish to consider whether it is necessary to put contractual arrangements in place to maintain some oversight over the process.

The first DAC6 reports are due to be made by taxpayers in August this year. In light of the recent COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic, requests have been made to HMRC from numerous trade bodies for this reporting timetable to be delayed. However, such matters would need to be decided at an EU level, and Brexit negotiations may limit the government’s willingness to make requests of the EU at this time. Another difficulty for the UK government with delaying the timetable is its stated public policy and the risk of appearing lenient on perceived tax avoidance (however misunderstood) whilst upholding pledges to further reduce the tax gap through additional compliance activity. Nevertheless, calls for a delay to the reporting timetable are being made from all corners of the EU and Gibson Dunn is following any and all developments closely.

II. Impact of COVID-19 coronavirus measures on internationally mobile workers

| Travel restrictions implemented in response to the COVID-19 coronavirus outbreak raise concerns regarding the tax implications of persons being stranded in unintended places. For businesses, there may be possible consequences for corporate residency, permanent and VAT establishments, transfer pricing apportionment, controlled foreign company attributions and employment taxes. Individuals may also have concerns about residency and their own employment tax liabilities. |

With lockdowns announced around the world due to the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic (including in the UK on 23 March 2020) travel has been severely curtailed and business practices are having to change accordingly. The physical location of people – of course – is a critical factor in determining where tax should be paid for cross-border businesses. These restrictions may therefore have implications across a wide range of potential taxes (particularly if maintained for material periods):

- Corporate tax residency: Broadly, a company will be UK tax resident if it is either (a) incorporated in the UK or (b) centrally managed and controlled in the UK (which is typically determined by reference to where the board of directors, or others involved in high-level strategy setting, make decisions). If directors of non-UK companies take decisions from the UK, there is a risk that they may render the relevant companies UK tax resident. Conversely, where entities are not incorporated in the UK and maintenance of UK tax residence is dependent on board meetings being held in the UK, the inability of non-UK resident directors to travel may jeopardise UK tax residence. Companies that either acquire or lose their usual corporate tax residency status are also at risk of suffering exit charges. Companies should also take care to check their articles of association which may include protocols to preserve tax residency e.g. restrictions on directors holding board meetings or participating by telephone or other electronic means from certain locations.

- Permanent establishments and VAT establishments: The requirement for employees to switch to remote working due to mandatory office closures may inadvertently create a permanent establishment (for corporation tax purposes), or a VAT fixed establishment, if employees are forced to work from jurisdictions in which their employer does not already have a place of business.

- Substance requirements: There is a risk that substance requirements may not be met where, as a result of lockdowns, employees (and in particular key employees) are unable to work from the jurisdiction in which their usual workplace is located.

- Transfer pricing allocations and controlled foreign company rules: The application of both sets of rules depends on significant people functions being located in particular jurisdictions. As with substance, this is not necessarily a question of quantity, and the absence / presence of certain critical persons for a sustained period could have an impact.

- Employment tax: Rules governing (a) the income tax and national insurance contributions payable by employees, (b) employer liabilities for national insurance contributions and (c) employer obligations to operate PAYE withholding, depend, to varying degrees, on:

- the tax residence of the individual, which is itself generally determined by reference to the number of days spent in a particular jurisdiction in a given year; and

- the location in which the employee’s duties are carried out and whether such duties are “incidental”.

Both employees and their employers will therefore be concerned about the risk of employees exceeding relevant thresholds.

Certain jurisdictions, such as Ireland and Australia, have issued guidance allaying taxpayer concerns about most (if not all) of the above issues. To address residency concerns, the Luxembourg authorities have enacted legislation enabling Luxembourg resident companies to hold virtual board meetings, which will be deemed to have been held at the company’s registered office. Meanwhile, authorities in Jersey and Guernsey have published guidance confirming that economic substance will not be jeopardised by changes in operating practices arising from coronavirus restrictions.

In contrast, HMRC has, thus far, remained silent on most of the above issues. Its only (minimal) concession to date has been to allow (subject to certain conditions) a maximum grace period of 60 days’ physical presence in the UK in applying statutory residence tests where individuals are stranded here due to COVID-19 coronavirus-related travel restrictions. It is hoped that more expansive guidance will be forthcoming.

Gibson Dunn is seeking HMRC’s confirmation on certain issues raised in this section. If there are specific concerns you would like us to address, please contact a member of the Gibson Dunn tax team.

III. Cayman Islands added to EU list of “non-cooperative jurisdictions”

| On 18 February 2020, it was announced that the EU’s Economic and Financial Affairs Counsel (“ECOFIN”) had added the Cayman Islands to its list of “non-cooperative jurisdictions” (countries which the EU considers to have sub-par tax governance standards). The move stems from the Cayman Islands’ late implementation of “economic substance” requirements for collective investment vehicles. |

Many jurisdictions have their own list of “non-cooperative” jurisdictions which mirrors or closely models the EU’s. Addition to such local lists can have significant consequences for those transacting with counterparties in blacklisted jurisdictions. For example, in France, payments to persons resident in non-cooperative jurisdictions may be subject to 75% withholding tax. Moreover, the EU Council has invited member states which haven’t yet implemented defensive measures (such as withholding tax, and denial of deductions, on payments made to blacklisted jurisdictions) to do so by 1 January 2021. On March 25, the Luxembourg government heeded the call, announcing its intention to restrict deductions on payments of interest and royalties to residents in non-cooperative jurisdictions. This suggests that others may well follow.

No such defensive measures have been adopted in the UK and the UK government has not given any indication whether it intends to do so. Accordingly, (for the moment at least) the addition of the Cayman Islands to the blacklist should not have any substantive UK tax implications. However, the addition of the Cayman Islands to the list is relevant to UK (and EU) reporting consequences. Broadly, under DAC6 (see section B.I.) certain cross border arrangements which take place after 25 June 2018 and feature specific “hallmarks” will need to be reported to the tax authorities of the UK and EU member states. One such “hallmark” is the making of deductible payments to associated persons in EU/OECD non-cooperative jurisdictions. It is not necessary for the parties to have a main benefit of obtaining a tax advantage. However, it is likely that such arrangements involving the Cayman Islands would be reportable in any event under DAC6, based on the “hallmark” that looks at deductible payments to associated persons in jurisdictions which do not impose tax on the receipt of such payments.

It is expected that ECOFIN will next update the blacklist in October 2020, and that the Cayman Islands will, at such time, be removed (although it is unclear whether the ECOFIN timetable may be impacted by the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic).

C. Recent Notable Cases

I. Melford Capital General Partner v Revenue and Customs Commissions [2020] UKFTT 6 (TC)

| In Melford, the UK First Tier Tribunal (FTT) revisited the often controversial subject of holding company VAT recovery – this time, in the context of a private equity fund investment structure. In a victory for the industry, good sense prevailed, and the VAT recovery position of the structure in question was affirmed. |

Melford involved the following private equity fund investment structure comprised of two VAT groups:

- The appellant (the “GP”) was the general partner of a private equity fund vehicle (an English limited partnership). For VAT purposes, the activities of a limited partnership are treated as the activities of its general partner. The GP was a member of a VAT group (the “Group”) with the fund’s investment advisor (the “Investment Manager”).

- The fund’s investment holding vehicle held shares in various SPVs which themselves held properties. These entities (“the Portfolio”) formed a second VAT group.

The Investment Manager provided investment management services to the fund (which were disregarded due to the existence of the Group) and the Portfolio (which were standard rated). The fund also provided interest free loans to the SPVs. The GP incurred costs in setting up the fund and providing management services to the SPVs, and applied for full recovery of the associated input VAT.

To obtain full recovery either (a) the relevant costs must be directly related to the provision of taxable supplies or (b) if part of general overheads, the taxpayer must only provide (non-exempt) supplies in the course of an economic activity. The Group’s claim was challenged by HMRC, who contended that (a) the setting up costs were directly related to the fund’s non-economic investment activity and (b) the ongoing management costs were general overheads which should, in light of such non-economic activity, only be partially recoverable.

In particular, HMRC considered that the ECJ judgement in Larentia + Minerva (C-108/14) (which concluded that corporate holding companies’ costs in acquiring subsidiaries are fully recoverable if the holding company provides, or intends to provide, management services to the subsidiaries) should not apply to funds. The FTT disagreed, and found that (a) the setting up costs were directly related to the Group’s economic activity of managing the subsidiaries and (b) the Group was not carrying on a separate non-economic investment activity. Indeed, the FTT appears to have gone further: in noting that the “setting up costs [were] incurred for the purpose of subscribing for shares in or providing loans to [the Portfolio] with the intention of providing the advisory services to them”, the tribunal appears to characterise the loans as part of the Group’s economic activities in managing the Portfolio.

It is not yet known whether HMRC has appealed the FTT’s decision. However, for the moment at least, Melford confirms that the VAT structuring used by the taxpayer (which is widely replicated within the private equity industry) works. Although sometimes considered a “post-completion” issue, for costs incurred in formation/acquisition to be recovered, it must be clear that management services are being (or are intended to be) provided. Best practice is therefore to ensure that a management agreement is in place, and that services are provided thereunder, from the outset.

Looking forward, HMRC’s choice to challenge the Group’s claim may perhaps have given rise to a concern that, after the Brexit transitional period comes to an end, the UK would utilise its new legislative freedom to reverse the effect of Minerva for UK investment structures. However, the almost two year gap between the Melford hearing and delivery of the judgment may perhaps have given HMRC pause for thought; the implication from the Budget documents (see further above) is that the UK wishes to revisit the VAT treatment of financial services in a manner which is competitive, and helpful to taxpayers. It is hoped that, as regards the VAT treatment of the fund management industry, this may indicate an intention on HMRC’s part to play the role of friend, rather than foe.

II. Blackrock Investment Management (UK) Limited v. United Kingdom C-231/19

| The Advocate General (“AG”) opinion in Blackrock will be of interest to fund managers providing investors with a mix of exempt and VAT-able supplies (or receiving such mixed supplies from counterparties) – as the AG advised that apportionment of consideration between the two should not generally be possible. |

The management of so-called special investment funds (“SIFs”) is exempt for VAT purposes (as to which, see above). The taxpayer (“Blackrock”) predominantly managed SIFs, but it also provided some VAT-able investment advisory services to non-SIFs. A related US entity (“Blackrock US”) provided investment management services to Blackrock in the form of an AI platform known as “Aladdin”. Blackrock applied for a refund of the portion of the VAT thereon attributable to Aladdin’s use in the management of non-SIFs. HMRC denied the claim, arguing that, as Blackrock US had provided a single supply, its characterisation as exempt or taxable could not be bifurcated, and must be determined by reference to its predominantuse.

At HMRC’s request, the UK’s Upper Tribunal (a chamber of the High Court) sought confirmation from the ECJ as to whether the VAT exemption for the management of SIFs justified a departure from general rules preventing bifurcation of single supplies. As is customary, the ECJ’s judgment (which has not yet been delivered) has been preceded by an advisory opinion of the AG. The AG considered that the supply by Blackrock US could not be apportioned, because it was a single indivisible supply, which must be treated uniformly. The conclusion was influenced by the need to interpret exemptions from VAT strictly, but practical considerations also appear to have been a factor: the nature of the supplies provided by Blackrock US did not vary depending on whether they were used in the management of SIFs or non-SIFs. If (as Blackrock suggested) the supply was apportioned by reference to the value of SIF and non-SIF funds under its management (a) the applicable rate of VAT would be subject to constant variation and (b) the management of non-SIFs could be rendered (albeit partially and proportionately) exempt.

If the opinion is followed by the ECJ, the consequences for taxpayers would vary depending on their VAT position. For example, those providing a limited number of taxable services who wish to reduce the cost to their investors may welcome such an approach. In contrast, if fund managers would prefer to improve their VAT recovery position, it is likely to be unhelpful.

However, the opinion does offer a route to a sensible result if care is taken. The AG considered that apportionment would be possible where detailed evidence could be provided that services were provided specifically and solely for SIFs. If followed, the practical (if unintended) impact may well be to offer taxpayers flexibility regarding the characterisation of supplies, by serving to highlight the importance of clear contractual arrangements. Where a mix of exempt and taxable supplies are to be made/received, if it is obvious that they are exclusively or predominantly exempt (or alternatively, taxable) then a single contract should suffice – and may perhaps be preferable, depending on the circumstances. However, if not, (while supplies should not be artificially split) it may be advisable to contract for the supplies separately.

III. Assem Allam v HMRC

| In Assem Allam, the FTT (a) rejected the application of a strict numerical threshold when assessing whether non-trading activity was “substantial” for the purposes of Entrepreneurs’ Relief and (b) concluded that the transactions in securities (“TiS”) rules (which re-characterise capital receipts as income in certain circumstances) did not apply, as the transaction was undertaken for commercial reasons – notwithstanding that it could have been structured in a manner which attracted more tax. |

Dr Allam transferred his shares in a property holding company (which undertook some development activities) to another entity he owned. He claimed Entrepreneurs’ Relief (“ER”) (which reduces the rate of capital gains tax to 10%) in respect of the transfer. HMRC denied the relief, arguing that the company transferred was not a trading company (as is required for ER) and that the TiS rules applied to re-characterise the disposal proceeds as income.

Entrepreneurs’ Relief

To claim ER on the disposal of shares, the company being transferred must not undertake “substantial” non-trading activities. HMRC guidance considers that “substantial” means more than 20% by reference to certain measures (e.g. income, asset-base, expenses incurred, time spent by employees). In finding that the condition was not met, the FTT looked to neither HMRC’s 20% threshold, nor Dr Allam’s suggested 50% threshold, noting “that there is no sanction in the legislation for the application of a strict numerical threshold”. Instead, the tribunal considered the question on first principles, concluding that words must be given “their ordinary and natural meaning in their statutory context” and that substantial should mean “of material or real importance in the context of the activities of the company as a whole”.

HMRC’s guidance had not offered a true safe harbour (in that a subjective weighing of the above-mentioned factors was required). However, by denying taxpayers the comfort of an objective threshold, the judgment will increase uncertainty (particularly where a company’s non-trading activities would fall below the 20% threshold on all measures). It remains to be seen whether the same approach will be applied in other legislative contexts where “substantial non-trading activities” are relevant (e.g. the UK’s capital gains participation exemption / “SSE”). More generally, the judgment serves as a reminder that HMRC guidance should be treated with some caution. In the event of conflict, it will be the terms of the relevant legislation, and not necessarily HMRC’s interpretation of it, which will be determinative.

Transactions in securities rules

For the TiS rules to apply, the taxpayer must have a tax avoidance motive. In this respect, Mr Assam relied on his commercial purposes for the transfer (e.g. the desire to group the two companies for corporation tax purposes and extract cash for his retirement). HMRC argued that Mr Assam would nevertheless have a tax avoidance motive if the transaction was deliberately structured in a manner which resulted in a smaller tax liability (as against alternative structures).

HMRC’s stance was aggressive, in light of existing case law which confirms that taxpayers are not obliged to structure their affairs so as to incur the maximum amount of tax. Although the FTT rejected HMRC’s argument, it was less than robust in defending this principle. The tribunal concluded that “the mere fact that there exists an alternative means of undertaking a transaction which has a different tax result is not conclusive of the question as to whether an inference can be drawn that the obtaining of an income tax advantage was a main purpose of the transaction” (emphasis our own) and that “in a particular case, the fact that [such] an alternative transaction existed and was perhaps considered but rejected, may be a factor in deciding whether or not [such] an inference can be drawn”. The judgement could be interpreted as an unfortunate watering down of the meaning of tax avoidance.

The decision to bring the case may well be a worrying indication that HMRC’s stance towards tax planning is growing ever-less tolerant. More concerning, however, is the suggestion that taxpayers may no longer be able to rely on established case law to protect them from HMRC’s most severe positions; regrettably, it appears that outcomes will turn on the particular facts, rather than long-held principles.

IV. Nicolas Walewski v HMRC [2019] UKFTT 0058

| The mixed partnership rules are anti-avoidance measures which prevent individuals from diverting their partnership profit share to the corporate partners they control (so that income may be taxed at the lower corporation tax rate). These rules were examined for the first time by the FTT in Walewski. The FTT found in HMRC’s favour, concluding that the rules applied to reallocate profits from a company the taxpayer was director of, to the taxpayer himself. |

In Walewski, the taxpayer was an investment advisor. He provided his services to clients through two LLPs, of which he was an individual member and employee. A UK company (“UKCo”), of which the taxpayer was an employee and director, was a second member of the LLPs. UKCo was indirectly owned by an offshore trust established for the benefit of the taxpayer’s children, but from which he could not benefit. As provided for by the partnership deeds of the LLPs, c. 99% of the profits were (directly or indirectly) distributed to UKCo, which in turn distributed them to the offshore trust.

Reallocation under the mixed partnership rules occurs, broadly, when (a) the profits allocated to a corporate partner exceed the notional return attributable to services or capital the corporate partner provides to the partnership and (b) it is reasonable to suppose that the excess allocation is attributable to an individual partner, via their power to enjoy the corporate partner’s profits. HMRC argued that both these tests were met, such that the profits allocated to UKCo should be reallocated to the taxpayer in his capacity as an individual member of the LLPs. The FTT agreed with HMRC.

The FTT considered that it was not possible to attribute UKCo’s allocation to its capital contribution (which was not significant) or the services provided by UKCo (via the taxpayer) to the LLPs. There was “no commercial, physical or temporal separation of the [taxpayer’s] activities”, so they could not be characterised merely as services provided to the LLPs in his capacity as employee of UKCo. As there was no commercial justification for the excessive allocation to UKCo, it was reasonable to suppose that it was attributable to the taxpayer’s power to enjoy the profits (and hence, to the services provided by the taxpayer to the LLPs directly). The FTT was unconvinced by the taxpayer’s argument that he did not have power to enjoy UKCo’s profits as he was a mere employee; his indirect power to enjoy them via the overseas trust to which his children were entitled was sufficient.

The case emphasises the importance of clear contractual arrangements supporting the provision of services in mixed fund structures. The capacity in which persons are acting when they provide services to the fund must be apparent – both as a matter of contract, and in practice. In this respect, where possible, simplicity should be favoured. Tiers of service providers may well result in boundaries being blurred in practice, running the risk that contractual arrangements may not be respected if tested before the courts. Moreover, where profit allocations exceed the amount attributable to capital or services, a clear commercial justification must be evidenced. This should be considered at the outset, and should not merely follow enquiries from HMRC. That being said, existing mixed fund structures should test their arrangements, and ensure that they are comfortable that allocations are justifiable, and not liable to fall foul of the mixed partnership rules.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist with any questions you may have regarding these developments. For further information, please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, any member of the Tax Practice Group or the authors:

Sandy Bhogal – London (+44 (0) 20 7071 4266, [email protected])

Ben Fryer – London (+44 (0)20 7071 4232, [email protected])

Panayiota Burquier – London (+44 (0)20 7071 4259, [email protected])

Bridget English – London (+44 (0)20 7071 4228, [email protected])

Fareed Muhammed – London (+44(0)20 7071 4230, [email protected])

© 2020 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.