January 2, 2018

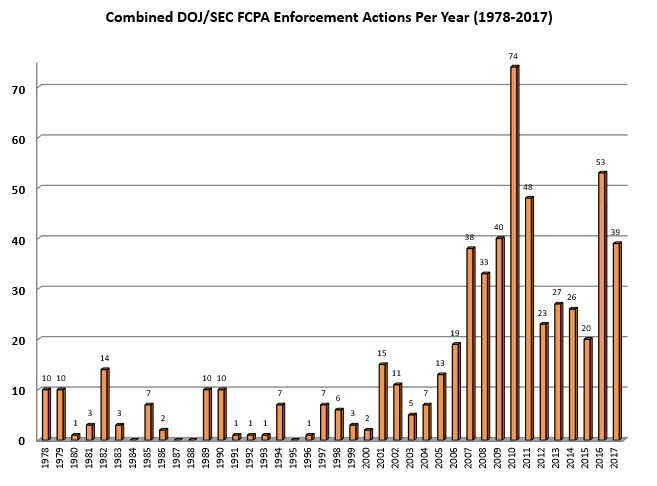

When President Jimmy Carter signed the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (“FCPA”) into law on December 19, 1977, not many predicted the dramatic impact this singular U.S. statute would still be having on the global rule of law some 40 years later. Indeed, the FCPA seems to have truly hit its stride as it passes 40 and looks toward its fifth decade of existence. Almost poetically, this 40th year of the FCPA saw 39 combined enforcement actions by the U.S. Department of Justice (“DOJ”) and Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”), the statute’s dual enforcers, joined in many cases by a global legion of anti-corruption enforcers unlike anything imagined four decades ago. In no small part the FCPA’s coming of age is due to the fact that the FCPA—the only one of its kind when enacted—is now joined by numerous other international corruption laws, multinational conventions, and hundreds of investigators, prosecutors, and regulators worldwide with a mission of ensuring a level playing field in global business markets.

This client update provides an overview of the FCPA and other domestic and foreign anti-corruption enforcement, litigation, and policy updates in 2017, as well as the trends we see from this activity.

FCPA OVERVIEW

The FCPA’s anti-bribery provisions make it illegal to corruptly offer or provide money or anything else of value to officials of foreign governments, foreign political parties, or public international organizations with the intent to obtain or retain business. These provisions apply to “issuers,” “domestic concerns,” and those acting on behalf of issuers and domestic concerns, as well as to “any person” who acts while in the territory of the United States. The term “issuer” covers any business entity that is registered under 15 U.S.C. § 78l or that is required to file reports under 15 U.S.C. § 78o(d). In this context, foreign issuers whose American Depository Receipts (“ADRs”) are listed on a U.S. exchange are “issuers” for purposes of the FCPA. The term “domestic concern” is even broader and includes any U.S. citizen, national, or resident, as well as any business entity that is organized under the laws of a U.S. state or that has its principal place of business in the United States.

In addition to the anti-bribery provisions, the FCPA also has “accounting provisions” that apply to issuers and those acting on their behalf. First, there is the books-and-records provision, which requires issuers to make and keep accurate books, records, and accounts that, in reasonable detail, accurately and fairly reflect the issuer’s transactions and disposition of assets. Second, the FCPA’s internal controls provision requires that issuers devise and maintain reasonable internal accounting controls aimed at preventing and detecting FCPA violations. Prosecutors and regulators frequently invoke these latter two sections when they cannot establish the elements for an anti-bribery prosecution or as a mechanism for compromise in settlement negotiations. Because there is no requirement that a false record or deficient control be linked to an improper payment, even a payment that does not constitute a violation of the anti-bribery provisions can lead to prosecution under the accounting provisions if inaccurately recorded or attributable to an internal controls deficiency.

40 YEARS OF FCPA ENFORCEMENT STATISTICS

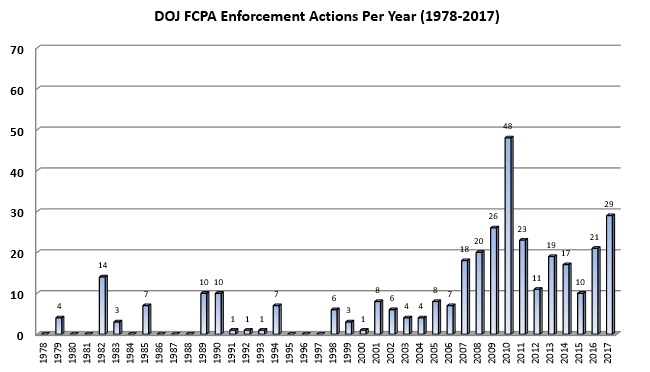

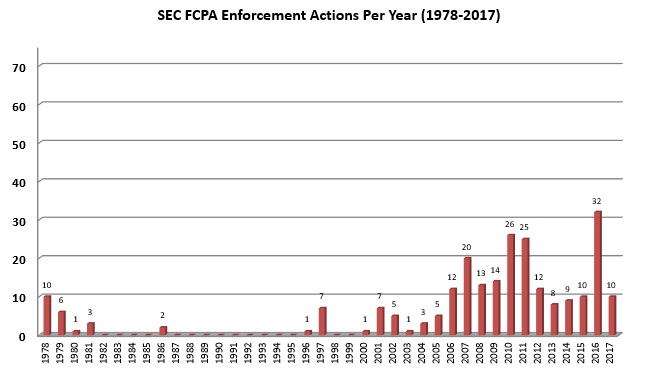

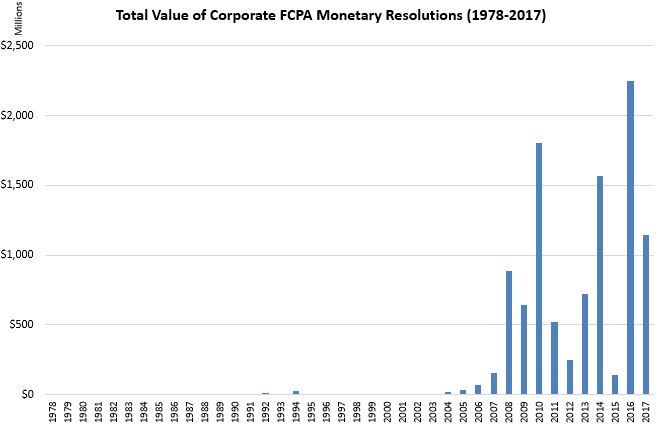

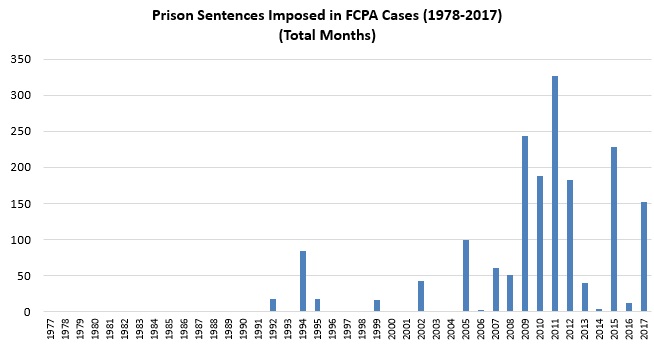

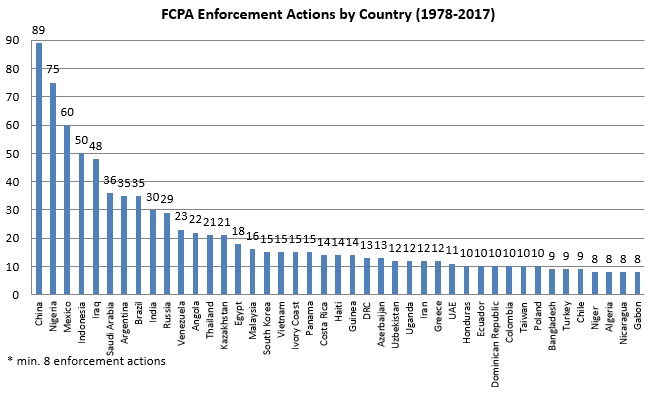

On this the 40th anniversary of the FCPA, we have expanded the traditional 10-year FCPA enforcement statistics that have become a mainstay of our semi-annual updates over the past decade to detail the entire history of FCPA enforcement by the numbers. These statistics detail the meteoric rise of FCPA enforcement—from the sleepy 1970s, 80s, and 90s, through the bustling 2000s. They also demonstrate the increasingly stiff penalties imposed in FCPA enforcement actions, by dollar and by the increasing certitude of time behind bars, as well as the most frequent situses of FCPA violations, with China holding a commanding lead after dominating the last decade in FCPA enforcement.

2017 FCPA ENFORCEMENT TRENDS

With dozens of dedicated and talented enforcement lawyers at DOJ and the SEC, and a team of law enforcement agencies working alongside them, it is little wonder that the FCPA’s 40th year was one of its most prolific. There is an energy in the hallways of the Bond Building, where DOJ’s FCPA Unit is staffed with a driven and relatively young team of prosecutors—clocking in at a median age just shy of 40, most were not alive when the statute was signed into law. Led by the articulate and indefatigable Dan Kahn, the majority of the 31 attorneys currently assigned to the Unit attended elite law schools, nearly 70% completed prestigious federal judicial clerkships early in their careers, and while more than 80% have private practice experience, the majority started with prior prosecutorial experience. Charles Cain, a quick study who distills complicated scenarios effortlessly, just this year assumed leadership of the SEC’s FCPA Unit. His attorneys likewise have deep experience, with the majority of the 31 attorneys joining the Unit from other positions at the SEC and nearly half having spent five years or more in the Unit. Each agency’s commitment to anti-corruption enforcement was on display during the second half of the year, with 21 combined FCPA enforcement actions in the last six months, bringing the total to 39 in 2017.

In each of our year-end FCPA updates, we seek not only to report on the year’s FCPA enforcement actions but also to identify and synthesize the trends that stem from these actions. For 2017, five key enforcement trends stand out from the rest:

1. Multi-jurisdictional anti-corruption resolutions continue apace;

2. DOJ continues to demonstrate a focus on culpable individuals;

3. DOJ and the SEC bring FCPA cases absent proof of bribery;

4. Recurring enforcement actions; and

5. DOJ and the SEC push the boundaries of “foreign official.”

Multi-Jurisdictional Anti-Corruption Resolutions Continue Apace

The FCPA was born of the policy judgment that corruption is bad business, and U.S. persons, companies, and those operating within the U.S. financial system should not profit from it. Of course, this was not a view uniformly held in 1977, and the reality is that there are still corners of the world where corruption is the norm rather than the exception. In these economies, the criticism has long been that foreign companies and individuals who do not have to play by the U.S. rulebook have an unfair advantage over those subject to the FCPA. Thus, one of the most important efforts in FCPA enforcement has been DOJ and SEC lawyers helping to build an aligned multinational network of law enforcers, aided by expanded legal tools, that together are making it increasingly more difficult for corrupt actors to engage in bribery with impunity. One way in which this increasingly complex enforcement environment manifests itself is coordinated, multi-jurisdictional anti-corruption actions involving DOJ and/or the SEC and any one (or more) of a growing number of their foreign counterparts. Four examples highlighted this phenomenon in 2017, resulting in more than $3 billion in cumulative corporate penalties.

The year in 2017 FCPA enforcement came to a roaring close with the announcement of a coordinated anti-corruption resolution with Singaporean shipyard company Keppel Offshore & Marine Ltd. (“KOM”). KOM is alleged to have paid, between 2001 and 2014, approximately $55 million in bribes to Brazilian government officials, including certain officers of Petróleo Brasileiro S.A. – Petrobras (“Petrobras”), Brazil’s state-owned oil company and the center of the Operation Car Wash investigation we have been reporting on for the past several years. The corrupt payments reportedly helped KOM win 13 contracts that netted the company more than $351 million in profits.

To resolve these allegations, KOM agreed to pay combined financial penalties of more than $422 million to authorities in the United States, Brazil, and Singapore. Specifically, DOJ calculated a total U.S. criminal fine of $422,216,980, and agreed with KOM, the Ministério Público Federal in Brazil, and the Attorney General’s Chambers in Singapore that this criminal fine would be satisfied by KOM paying 50% ($211,108,490) to Brazilian authorities and 25% ($105,554,245) to each of the other two. The total U.S. criminal fine reflected a 25% discount from the bottom of the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines range, the maximum amount KOM was entitled to under DOJ policy based on its significant cooperation but failure to voluntarily disclose the conduct at issue. The U.S. resolution took the form of a deferred prosecution agreement with KOM and a guilty plea by its U.S. subsidiary, each charging conspiracy to violate the FCPA’s anti-bribery provisions; the Singaporean resolution took the form of a “conditional warning” from the Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau; and the Brazilian resolution took the form of a leniency agreement with the Ministério Público Federal. DOJ did not impose a compliance monitor on KOM, but KOM did agree to submit annual reports to DOJ on the status of its compliance program over the three-year term of the deferred prosecution agreement. Because KOM is not an issuer, there was no parallel SEC enforcement action.

In another multi-jurisdictional enforcement action arising from Operation Car Wash, on November 29, 2017, DOJ announced an FCPA resolution with Dutch oil and gas services provider SBM Offshore N.V. According to the charging documents, from 1996 to 2012 SBM conspired to pay more than $180 million in commissions to third parties, knowing that at least part of the funds would be used to bribe government officials in Angola, Brazil, Equatorial Guinea, Iraq, and Kazakhstan. SBM reportedly gained more than $2.8 billion in profits from projects received in return for these illicit payments.

As we reported in our 2014 Year-End FCPA Update, SBM previously reached a $240 million anti-corruption settlement with the Dutch Public Prosecutor (Openbaar Ministerie) in November 2014 arising from substantially the same course of conduct. DOJ closed its investigation at that time, with no intention of bringing a parallel enforcement action of its own, since at that time there was no evidence of conduct in the United States sufficient to vest jurisdiction over the non-issuer Dutch entity. However, in 2016 DOJ reopened its investigation based on new evidence that a substantial portion of the corrupt scheme was allegedly managed by a U.S.-based executive of a U.S. subsidiary of SBM. In addition, this new evidence opened the allegations of corruption in Iraq and Kazakhstan, which were not part of the original resolution with Dutch authorities.

To resolve the November 2017 U.S. charges, SBM agreed to pay a $238 million criminal penalty in connection with a deferred prosecution agreement, and to have its U.S. subsidiary plead guilty, with both charging documents alleging a conspiracy to violate the FCPA’s anti-bribery provisions. Notably, SBM did not receive voluntary disclosure credit from DOJ, even though it voluntarily disclosed the matter to DOJ and Dutch authorities, because SBM allegedly failed to bring the full facts and circumstances to DOJ’s attention for one year, which was not timely according to DOJ. With only a 25% discount from the bottom of the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines range for cooperation, rather than the 50% discount from a lower Guidelines range it may have received if this matter had been viewed as a voluntary disclosure, SBM’s penalty should have been set at $3.83 billion. The $238 million fine (roughly 7% of this discounted figure) reflects the $240 million already paid to Dutch authorities, an additional amount (reportedly $342 million) to be paid to Brazilian authorities, and most significantly, a desire to “avoid[] a penalty that would substantially jeopardize the continued viability of the Company.” DOJ did not impose a compliance monitor on SBM, but SBM did agree to submit annual reports to DOJ on the status of its compliance program over the three-year term of the deferred prosecution agreement. Because SBM is not an issuer, there was no parallel SEC enforcement action.

Still another multi-jurisdictional anti-corruption resolution is that of Swedish telecom company and former ADR issuer Telia Company AB, which was announced jointly by authorities in the United States, the Netherlands, and Switzerland on September 21, 2017. Weighing in at more than $965 million, the Telia enforcement action is one of the largest in global anti-corruption history. Similar to the VimpelCom resolution, reported in our 2016 Mid-Year FCPA Update, this case arose from allegations that Telia paid hundreds of millions of dollars to the daughter of the President of Uzbekistan—including making payments to a shell company beneficially owned by the daughter, as well as purchasing at an inflated price a company in which she held a financial stake—all to facilitate entry into and licenses to operate in the Uzbek telecommunications market. The revenue Telia generated from its business in Uzbekistan allegedly totaled more than $2.5 billion, on which Telia allegedly earned $457 million in profits.

To resolve the U.S. charges, Telia entered into a deferred prosecution agreement with DOJ and had its Uzbek subsidiary plead guilty to charges of conspiracy to violate the FCPA’s anti-bribery provisions. The parent also consented to an SEC administrative cease-and-desist order alleging FCPA bribery and internal controls violations. In addition, Telia reached parallel resolutions with the Dutch Public Prosecutor (Openbaar Ministerie) and Swedish Prosecution Authority (Åklagarmyndigheten). After netting out a series of financial credits and offsets, Telia is expected to pay $274.6 million to DOJ, $274 million to the Dutch Public Prosecutor, $208.5 million to the SEC, and $208.5 million to either the Dutch Public Prosecutor or Swedish Prosecution Authority. (The uncertainty of the final payment is a function of Swedish law, which may require prosecutors to first establish the corruption beyond a reasonable doubt in ongoing criminal cases against individual Telia executives before it may accept its share of the corporate settlement.) Notably, not only was Telia able to escape a compliance monitor as part of its U.S. resolution, but it also is not required to report annually on its compliance program during the term of the deferred prosecution agreement.

In addition to the three discussed above, we reported on a fourth multi-jurisdictional anti-corruption enforcement action of 2017, involving Rolls Royce plc, in our 2017 Mid-Year FCPA Update. The following chart captures such resolutions from 2016 and 2017 and demonstrates this growing trend, which we expect will continue to be a significant part of global anti-corruption enforcement.

Multi-National Anti-Corruption Enforcement Actions – 2016 & 2017

|

Company |

Total Resolution |

U.S. Portion |

Other Countries Involved – Payments |

|

|

Keppel Offshore & Marine |

$ 422,216,980 |

$ 105,554,245 |

Brazil (Ministério Público Federal) |

$ 211,108,490 |

|

SBM Offshore |

$ 820,000,000 |

$ 238,000,000 |

Brazil (Ministério Público Federal) |

$ 342,000,000 |

|

Telia |

$ 965,773,949 |

$ 483,273,949 |

Netherlands (Openbaar Ministerie) |

$ 274,000,000 |

|

Rolls-Royce |

$ 800,305,272 |

$ 169,917,710 |

Brazil (Ministério Público Federal) |

$ 25,579,170 |

|

Odebrecht & Braskem |

$ 3,557,625,337 |

$ 252,893,801 |

Switzerland (Swiss Attorney General) |

$ 210,893,801 $ 3,093,837,736 |

|

Embraer |

$ 205,000,000 |

$ 185,000,000 (DOJ / SEC) |

Brazil (Federal Prosecution Office) |

$ 19,300,000 |

|

GlaxoSmithKline |

$ 509,000,000 |

$ 20,000,000 |

China (Changsha People’s Court) |

$ 489,000,000 |

|

VimpelCom |

$ 795,300,000 |

$ 397,600,000 |

Netherlands (Openbaar Ministerie) |

$ 397,500,000 |

DOJ Continues to Demonstrate a Focus on Culpable Individuals

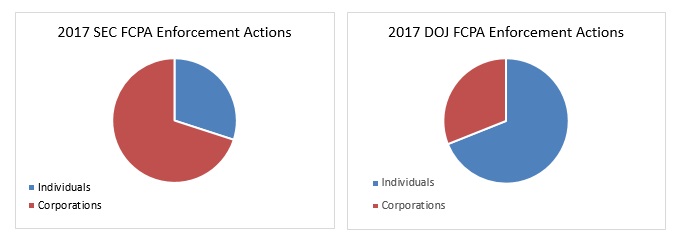

After years of Deputy Attorneys General issuing namesake memoranda pronouncing DOJ policy for corporate prosecutions, the 2015 “Yates Memo” signaled an emphatic shift toward holding individual actors accountable for corporate misconduct. This focus on individual liability has survived and even flourished through the shift in administrations, with nearly 70% of DOJ’s 2017 FCPA enforcement docket constituting prosecutions against individual defendants. (The percentage is even higher if non-FCPA charges arising from FCPA investigations are considered.) Indeed, DOJ’s 20 individual FCPA prosecutions this year is the highest number in any of the FCPA’s 40-year history except 2010, the year of the numerous (and subsequently dismissed) SHOT Show indictments. The SEC, for its part, continues to espouse the importance of individual accountability, with Co-Director of Enforcement Steven Peiken most recently asserting that individual liability will be an “intense focus [of the SEC] in every FCPA investigation.” Yet the SEC’s numbers for 2017 continue to reflect the inverse of DOJ’s, with individuals representing 30% of the SEC’s FCPA enforcement docket.

There are several subsidiary points to be made of DOJ’s focus on individual culpability.

First, it has been a commonly recited critique of recent years that DOJ and the SEC have focused too heavily on corporate liability in FCPA enforcement, and not sufficiently on holding accountable the individual actors responsible for the corporate FCPA violations. Whether or not this is a fair criticism historically, certainly it does not accurately reflect 2017 FCPA enforcement, and our suspicion is that it will not in years to come. DOJ’s 2017 enforcement docket, in particular, makes good on statements that DOJ officials have been making for years about its focus on prosecuting culpable individuals. Examples from 2017 FCPA enforcement include:

- KOM Lawyer – On August 29, 2017, senior KOM lawyer Jeffrey S. Chow entered a guilty plea in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York to a single count of conspiracy to violate the FCPA’s anti-bribery provisions. As allocuted at his plea hearing, Chow was a more than 25-year lawyer at KOM responsible for, among other things, drafting and preparing contracts with the company’s agents. In the course of executing these duties, Chow became aware that the agent KOM had hired for Petrobras business was being overpaid, sometimes by millions of dollars. Although he did not negotiate the contracts or make the decision to pay the bribes, Chow admitted that his role in drafting the contracts gave the illicit payments a semblance of legality and was therefore an important part of the corrupt scheme. Chow’s plea was unsealed on December 26, 2017, days after charges were filed against his former employer as described above.

- Rolls-Royce Five – On November 7, 2017, nearly a year after the corporate resolution covered in our 2017 Mid-Year FCPA Update, FCPA charges were unsealed in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Ohio against three former Rolls-Royce employees (James Finley, Keith Barnett, and Aloysius Johannes Jozef Zuurhout), a former company intermediary (Petros Contoguris), and an executive of an international engineering and consulting firm working with Rolls-Royce (Andreas Kohler). The allegations concern an alleged plot to bribe officials of a state-owned joint venture between the governments of China and Kazakhstan, formed to transport natural gas between the two nations. The Rolls-Royce defendants allegedly disguised corrupt payments as commissions to Contoguris’s company, which then passed portions of those payments on to Kohler’s firm to use as bribes. Contoguris, a Greek citizen believed to be residing in Turkey, has yet to be brought before the court and has been deemed by DOJ to be a fugitive. Contoguris has been indicted on seven counts of FCPA bribery, 10 counts of money laundering, and one count each of conspiracy to violate these two statutes. The other four defendants have each pleaded guilty to criminal informations charging conspiracy to violate the FCPA and/or substantive FCPA bribery violations.

- SBM Executives – In early November 2017, weeks before the corporate resolution described above, two former executives of SBM Offshore were charged criminally for their role in the corruption scheme. Anthony Mace and Robert Zubiate, respectively the former CEO of the parent company and a sales and marketing executive of its U.S. subsidiary, pleaded guilty to one count each of FCPA conspiracy in connection with the company’s bribery of government officials in Angola, Brazil, and Equatorial Guinea. The charges against Mace are noteworthy not only in that he was the CEO of a major international company, but also because the entire theory of liability was so-called willful blindness—i.e., that he authorized payments to third parties without actually knowing that they would be used for corrupt purposes, but while being “aware of a high probability [that] these payments were bribes and deliberately avoided learning the truth” about them.

- Embraer Executive – On December 21, 2017, more than a year after the corporate resolution covered in our 2016 Year-End FCPA Update, former Embraer sales executive Colin Steven was charged by criminal information in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York. Steven, a UK citizen residing in the United Arab Emirates while working for the Brazilian aircraft company, pleaded guilty to substantive and conspiracy FCPA and money laundering violations in connection with a scheme to pay $1.5 million in bribes to an official of Saudi Arabia’s state-owned oil company to secure the $93 million sale of three airplanes, as well as a related personal enrichment kickback scheme. Steven also pleaded guilty to making a false statement to FBI agents concerning the purpose of the funds related to the kickback scheme.

- Odebrecht-Related Charges – Although little is known about these cases due to the fact that virtually all filings are under seal, FCPA Unit prosecutors have filed non-FCPA charges against two individuals reportedly connected to the wide-ranging Odebrecht bribery scheme reported on in our 2016 Year-End FCPA Update. On April 20, 2017, Paulo César de Miranda and Barry W. Herman were charged by criminal complaint with one count each of failing to report a foreign financial account. Miranda was also charged with a second count of making and using a false document.

Second, the FCPA’s anti-bribery provisions, by their plain terms, do not cover the receipt of bribes by foreign government officials. This was a conscious decision by Congress, which in passing the FCPA sought to regulate the domestic effects of corrupt business practices without treading too much upon the sovereignty of foreign nations and their own government officials. Decades ago, DOJ sought to get around this statutory barrier by charging foreign official bribe recipients with conspiracy to violate the FCPA. This approach was soundly rejected in a per curiam opinion of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in United States v. Castle, 925 F.2d 831 (5th Cir. 1991), and has not been revisited since. However, as we have noted in recent years (e.g., 2011 Year-End FCPA Update), DOJ has found the money laundering statute to be an effective tool for holding foreign official bribe recipients criminally liable where they use the U.S. financial system to launder the proceeds of their corruption. Although these are not “FCPA” cases, they are generally prosecuted by the FCPA Unit, often in conjunction with FCPA cases, as can be seen from the following 2017 examples:

- PDVSA Defendants – DOJ has announced and unsealed the ninth and tenth guilty pleas in its ongoing investigation of a “pay to play” corruption scheme involving Venezuelan state-owned oil company Petróleos de Venezuela S.A. (“PDVSA”), which we last covered in our 2017 Mid-Year FCPA Update. Specifically, on October 11, 2017, Florida businessman Fernando Ardila-Rueda pleaded guilty to substantive and conspiracy FCPA bribery charges, and on June 21, 2017, the Court unsealed the prior guilty plea to money laundering conspiracy by PDVSA purchasing representative and foreign official Karina Del Carmen Nunez-Arias, in connection with hundreds of thousands of dollars in bribes paid to place Ardila-Rueda’s company on bidding panels for PDVSA projects. In total, six businesspersons and four PDVSA officials have been charged with and pleaded guilty to FCPA and money laundering offenses, respectively, in connection with this investigation to date. Notably, Nunez-Arias was charged in 2016, but the charges were kept under seal while the investigation developed, a standard practice in FCPA investigations that leads us always to caution that the true extent of FCPA enforcement during a given period is not always public knowledge.

- Petroecuador Defendant – On October 12, 2017, DOJ charged a former executive of Ecuadorean state-owned oil company Petroecuador, Marcelo Reyes Lopez, for his alleged role in an FCPA-related money laundering scheme. The public, unredacted version of the indictment is extremely sparse, but a DOJ motion to enter a protective order limiting disclosure of information about the case alleges that it has developed evidence of an “extensive bribery scheme that existed to provide illicit payments to officials from [Petroecuador] in order to secure and profit from contracts with that company.” Lopez has been detained pending a June 2018 trial date, and DOJ is seeking the forfeiture of six of his properties in Florida.

Third, debates often ensue about whether the suspected corrupt payments at issue in FCPA cases were actually used for corruption or simply pocketed by a third party as fraud. This truism of FCPA enforcement was explicitly alleged in two 2017 FCPA cases as follows:

- Vietnamese Skyscraper Defendants – We reported in our 2017 Mid-Year FCPA Update on FCPA charges arising from a plot to bribe an official of a Middle Eastern sovereign wealth fund to induce the official to cause the fund to purchase a financially distressed skyscraper in Hanoi. On October 31, 2017, FBI agents arrested real estate broker Andrew Simon for his alleged role in the plot, which involves Simon’s former co-workers, Sang Woo and Joo Hyun Bahn; Bahn’s father and executive of the South Korean construction company who owned the distressed property, Ban Ki Sang; and a fashion designer who was supposed to broker the corrupt deal, Malcolm Harris. Much to the surprise of everyone else in the alleged deal, Harris did not actually know the official at the sovereign wealth fund and used the $500,000 down payment on an agreed-upon $2.5 million bribe for his own enrichment. Harris pleaded guilty to non-FCPA fraud charges and was sentenced in October 2017 to 42 months in prison; Woo has reportedly pleaded guilty and is cooperating with DOJ; Bahn is reportedly in plea discussions with DOJ; Simon has pleaded not guilty; and Sang, who is in South Korea, has not yet been brought before the court. DOJ’s theory of FCPA liability for these defendants, even where there was no real corruption of a foreign official, is that the defendants (other than Harris) agreed to bribe a foreign official and that the agreement itself, even without money changing hands, was a violation of the anti-bribery provisions.

- Haitian Development Defendant – On August 29, 2017, DOJ unsealed a criminal complaint charging Joseph Baptiste, a retired U.S. Army colonel and founder of a non-profit formed to help Haiti’s poor, on charges stemming from his alleged role in a corruption scheme connected to a Haitian development project. Unbeknownst to Baptiste, the project’s investors who provided him the bribe money were undercover FBI agents. Unbeknownst to the undercover FBI agents, Baptiste used the $50,000 down payment on a bribe for his own personal expenses. DOJ alleges that there was an FCPA violation because Baptiste allegedly intended to use additional payments for actual bribery of Haitian port officials. Baptiste reportedly entered into a signed plea agreement with DOJ after being approached by authorities and before the charges were made public, but then backed out of that deal, leading to his arrest. On October 4, 2017, DOJ filed an indictment charging Baptiste with FCPA, Travel Act, and money laundering violations.

The final set of individual cases brought by DOJ in 2017 concerns a new branch of corruption at the United Nations. We first reported in our 2015 Year-End FCPA Update on bribery charges implicating former President of the U.N. General Assembly John Ashe and a scheme to corruptly influence a plan to build a U.N.-sponsored conference center in Macau (a 2017 trial conviction of one of the businessmen involved in this scheme is discussed below). On November 20, 2017, DOJ unsealed a criminal complaint alleging a completely distinct bribery scheme involving Ashe’s successor to the U.N. General Assembly presidency. Chi Ping Patrick Ho, the head of a non-governmental organization that holds “special consultative status” at the United Nations and is associated with the China Energy Fund, and Cheikh Gadio, the former Foreign Minister of Senegal and a business consultant, were each charged with substantive and conspiracy FCPA and money laundering violations associated with two separate bribery schemes. The first involved an alleged scheme to pay $2 million to the President of Chad to secure valuable oil concessions and reduce a substantial fine for environmental violations by Ho’s Chinese employer. The second scheme, allegedly “hatched in the hallways of the United Nations,” involved a separate plan to bribe the current Foreign Minister of Uganda and then-President of the U.N. General Assembly with $500,000 for various illicit benefits, including a share in profits from a Ugandan joint venture with Ho’s Chinese employer. Ho alone was indicted on these charges on December 18, 2017. Neither individual has yet (publicly) entered a plea in connection with these charges.

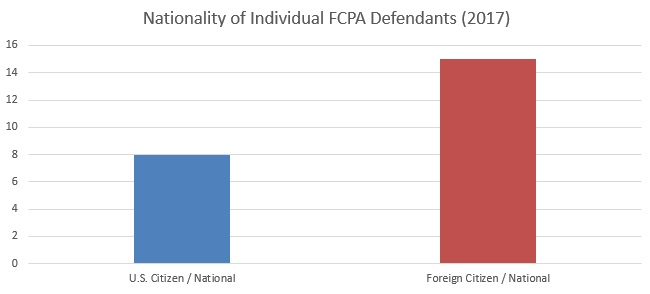

As noted in many of the cases described above, a substantial portion of the individual FCPA defendants in 2017 are foreign nationals. Specifically, as shown below, 15 of the 23 individual defendants (nearly two-thirds) were foreign nationals.

DOJ and the SEC Bring FCPA Cases Absent Proof of Bribery

In the opening paragraphs of each of our semi-annual reports we note that the FCPA’s accounting provisions enable DOJ and the SEC to bring FCPA charges against issuers and their representatives even in the absence of proven bribery. This year, DOJ and the SEC utilized these provisions to bring several cases predicated upon aggressive theories of FCPA liability.

In our 2017 Mid-Year FCPA Update, we reported on two such FCPA enforcement cases containing no allegations of actual bribery: (1) the SEC’s cease-and-desist proceeding against Cadbury / Mondelēz International, where the violation alleged by the SEC was payments to an agent on whom due diligence was not conducted and no written documentation of activities was obtained; and (2) DOJ’s non-prosecution agreement with Las Vegas Sands, where the violation alleged by DOJ was payments to a Chinese consultant, continuing even after being warned of the consultant’s allegedly dubious business practices.

More recently, on July 27, 2017, the SEC announced an FCPA cease-and-desist action against Texas-based oilfield services provider Halliburton Company relating to alleged accounting violations arising from its retention of a local Angolan company. According to the charging document, in 2008 Halliburton customer Sonangol, the Angolan state-owned oil company, put pressure on Halliburton to partner with more locally-owned businesses to satisfy local content regulations for foreign firms operating in Angola. In response, Halliburton retained and paid $3.7 million to a local company owned by a neighbor and friend of the Sonangol official responsible for approving Halliburton’s contracts. There was no bribery alleged. But the SEC contended that Halliburton violated its own internal controls over the approval of local business partners, including by subverting a required internal bidding process and by reclassifying the type of vendor to one with a lower degree of scrutiny, to expedite the retention of this local firm. Further, while the SEC acknowledged that there were “possible justifications for selecting the local Angolan company,” the SEC found it significant that these justifications were discussed only in company e-mails and not documented in Halliburton’s accounting system. Collectively these actions, the SEC contended, violated the books-and-records and internal controls provisions of the FCPA.

To resolve these charges, Halliburton consented to the entry of a cease-and-desist order and agreed to pay $29.2 million, consisting of $14 million in disgorgement from contracts awarded during the relevant period, $1.2 million in prejudgment interest, and a $14 million civil penalty. In addition, Halliburton was required to retain an independent consultant, focused on African operations, for an 18-month term. Finally, the SEC also brought an action against Halliburton’s former Angola country manager, Jeannot Lorenz, who allegedly selected and caused the accounting violations associated with the retention of the vendor in question. To settle his charges, Lorenz paid a $75,000 civil penalty and agreed to cease and desist from future violations of the FCPA’s accounting provisions. DOJ closed its investigation without taking any action.

Recurring Enforcement Actions

The FCPA now having been around for four decades, as well as the subject of some of the most aggressive corporate enforcement seen over the last 10-15 years, we are beginning to see more and more companies find themselves the subject of a second FCPA enforcement action. For example, the Halliburton action of July 2017, described immediately above, follows a somewhat larger scale FCPA resolution between the company and the SEC in 2009 arising from the participation of its former subsidiary in the Bonny Island “TSKJ” liquid natural gas consortium in Nigeria, as covered in our 2009 Mid-Year FCPA Update.

But Halliburton was only one of three companies to register a second FCPA charge in 2017. In addition, as covered in our 2017 Mid-Year FCPA Update, Zimmer Biomet Holdings (formerly Biomet, Inc.) and Orthofix International each reached FCPA resolutions during the first half of the year that each followed prior FCPA enforcement actions in 2012. Notably, it appears from the public documents that the companies’ reporting and oversight obligations imposed as part of the first FCPA resolutions played a role in some or all three of these companies uncovering the conduct leading to the second FCPA resolutions. The lesson to be learned is that companies must not let down their guard following an FCPA settlement with DOJ and/or the SEC, as the standard obligation in most corporate FCPA resolutions to report for several years “credible evidence” of “corrupt payments” presents significant ongoing risk to the company if not handled appropriately.

With an acknowledgement that the ever-changing corporate form renders this a somewhat imprecise exercise, at least 12 companies have had multiple FCPA resolutions. The industry sectors range widely from pharmaceutical companies, to information and infrastructure, to technology and telecommunications.

DOJ and the SEC Push the Boundaries of “Foreign Official”

For years there has been debate, from the courts to congressional committees, about the FCPA’s application to employees of commercial entities owned or controlled by foreign governments. To date, DOJ and the SEC have gotten the better of this “state-owned entities” argument, as efforts to amend the statute petered out and the courts have with virtual unanimity sided with the government’s view. Unless and until there are further developments, we are guided by complex, multi-factored tests from United States v. Esquenazi, 752 F.3d 912 (11th Cir. 2014) and the DOJ/SEC FCPA Resource Guide, as described in our 2014 Mid-Year and 2012 Year-End FCPA updates, respectively.

In 2017, DOJ and the SEC pushed the boundary on who constitutes a “foreign official” for purposes of the FCPA perhaps even a step further. In two corporate FCPA settlements, they included allegations buried deep in the charging documents that, although they do not constitute binding precedent as they were settled outside of court, do give a window into the government’s increasingly expansive view of the statute’s coverage.

The SEC’s final FCPA charges of 2017 were levied against Massachusetts-based medical diagnostic test manufacturer Alere, Inc. On September 28, 2017, the SEC announced that Alere consented to a cease-and-desist order alleging a variety of accounting violations, principally related to alleged revenue recognition violations, but which also included the failure to prevent and properly record improper payments to foreign officials in Colombia and India. To resolve the charges, Alere without admitting or denying the SEC’s findings agreed to pay more than $3.8 million in disgorgement plus prejudgment interest and a $9.2 million civil penalty. Alere has announced that DOJ closed its investigation without taking action.

The SEC alleged that Alere made corrupt payments to a manager of a health insurance company in Colombia. Although the health insurance company was privately incorporated, the SEC alleged that Colombia’s Ministry of Health took control of the company following allegations of mismanagement. According to the SEC, the health insurance company thus became “an instrumentality of the Government of Colombia and its employees were officials of the Government of Colombia.”

The second allegation of note in this regard concerns DOJ’s charges against SBM Offshore discussed above, and specifically the allegations of corruption in Kazakhstan. SBM was alleged to have made corrupt payments to obtain oil exploration and development contracts both to an employee of KazMunayGas, Kazakhstan’s state-owned oil company, and to an employee of a subsidiary of an Italian oil and gas company. Although the latter entity is clearly commercial in nature, DOJ alleged that its employee “was acting in an official capacity for or on behalf of KazMunayGas” because his employer was granted a concession to operate the oil field. In other words, consistent with a view espoused in FCPA Opinion Procedure Release 2010-03, covered in our 2010 Year-End FCPA Update, DOJ treated an employee of a commercial company as a “foreign official” for purposes of the FCPA based on the company’s license to operate on behalf of a state-owned entity.

2017 FCPA-RELATED POLICY DEVELOPMENTS

New FCPA Corporate Enforcement Policy

One of the most challenging decisions any corporate counsel faces is whether, upon learning of suspected misconduct within the company, to self-report that information to government prosecutors and regulators. Most companies operate with a sincere commitment to ethical conduct and transparency, and would be naturally inclined to make such reports and see the wrongdoers held accountable, particularly since in so many cases it is the company that has been victimized by the misconduct. But the U.S. legal construct of respondeat superior liability, whereby the company itself may be held civilly or even criminally liable for the misdeeds of its representatives if there was at least some intention to benefit the company, even where the action was clearly against corporate policy, gives any company counsel pause. Add to that prospect of potential corporate criminal liability the cost, collateral consequences (such as civil litigation), distraction, length, and uncertainty of corporate criminal investigations, and you have a recipe for what inevitably is a difficult disclosure decision.

Recognizing these difficulties, and incentivized to encourage more corporate disclosures, DOJ has sought to provide greater certainty and transparency concerning the benefits of voluntary disclosure in anti-corruption cases. This effort began with the announcement of a 12-month “FCPA Pilot Program” in April 2016, covered in our 2016 Mid-Year FCPA Update, which was subsequently extended and then, finally, codified in the U.S. Attorneys’ Manual as the new “FCPA Corporate Enforcement Policy,” announced by Deputy Attorney General Rod J. Rosenstein on November 29, 2017.

The FCPA Corporate Enforcement Policy introduces a presumption that DOJ will decline prosecution of a company that voluntarily discloses FCPA-related misconduct, cooperates fully in the ensuing investigation, and appropriately remediates the misconduct. There are, however, many caveats.

First and foremost is what DOJ considers “appropriate remediation.” To qualify for a “declination” under the FCPA Corporate Enforcement Policy, companies are required to disgorge any allegedly improper profits from the conduct. This can be accomplished in the form of a resolution with a parallel regulator, such as the SEC, or it could take the form of the so-called “declination with disgorgement” resolutions we covered in our 2016 Year-End and 2017 Mid-Year FCPA updates. In either event, even a “declination” under this policy may be accompanied by public allegations (or even admissions) of corporate misconduct and financial “penalties.”

Second, the “presumption” of declination that accompanies a voluntary disclosure is just that, a “presumption” that may be overcome by “aggravating circumstances.” Such circumstances enumerated in the FCPA Corporate Enforcement Policy include, but according to DOJ are not necessarily limited to: (1) the involvement of executive management in the misconduct; (2) significant profits from the misconduct; (3) misconduct that was pervasive; and (4) “criminal recidivism.” If DOJ determines that such aggravating circumstances (or others, not enumerated in the Policy) render it inappropriate to provide a “declination,” the FCPA Corporate Enforcement Policy provides that in the ensuing prosecution it will provide a 50% reduction off the low end of the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines range (except in cases of recidivism) and also generally not require a monitor for organizations that have implemented an effective compliance program. Like the FCPA Pilot Program, for companies that do not self-disclose, but otherwise cooperate and undertake appropriate remediation, DOJ will provide at most a 25% discount off the bottom of the Guidelines range.

There is no question that DOJ’s FCPA Corporate Enforcement Policy is a positive step forward in providing some transparency to companies that discover corruption-related misconduct. Nevertheless, many questions concerning this policy abound. For example, what is a “criminal recidivist”? Another interesting and rather novel statement included in the Policy with no elaboration is that as a precursor to receiving mitigation credit, a company must “prohibit[] employees from using software that generates but does not appropriately retain business records and communications.” Given the prevalence of commercial messaging apps throughout the workforce, the vast majority of which are used for completely legitimate means, companies will need to be prepared to address this issue.

Following Kokesh, IRS Reaffirms View Disgorgement Is Not Tax Deductible

As reported in our client alerts 2017 Mid-Year FCPA Update and United States Supreme Court Limits SEC Power to Seek Disgorgement Based on Stale Conduct, in Kokesh v. SEC, 137 S. Ct. 1635 (2017), the Supreme Court unanimously held that disgorgement in an SEC enforcement proceeding is a “penalty” within the meaning of 28 U.S.C. § 2462 and therefore is subject to the five-year statute of limitations. This decision limits the SEC’s ability to seek disgorgement based on conduct that occurred more than five years earlier, and also rejects the SEC’s long-held position that disgorgement is an equitable remedy not subject to any limitations period.

Following Kokesh, on December 1, 2017, the Internal Revenue Service released a Chief Counsel Advice Memorandum (CCA 201748008) addressing the deductibility of amounts paid as disgorgement for securities law violations. Similar to the May 2016 CCA covered in our 2016 Mid-Year FCPA Update, the IRS concludes that a taxpayer cannot claim a U.S. federal income tax deduction for a disgorgement payment associated with a securities law violation. Section 162(f) of the Internal Revenue Code prohibits a deduction for any fine or similar penalty paid to a government for a violation of law. In light of the Supreme Court’s ruling in Kokesh that disgorgement is equivalent to a penalty, the IRS took the view that disgorgement payments are penalties and therefore not deductible.

Global Magnitsky Executive Order on Human Rights Abuses / Corruption

We have for years been following the U.S. government’s increasing focus on sanctioning foreign government officials engaged in corruption. Examples covered in this Update include the increased employment of the money laundering statute for criminal prosecution of the individuals discussed above and in rem civil forfeiture actions against the corrupt proceeds discussed below.

On December 20, 2017, prosecutors and regulators were handed still another tool in the fight against international corruption. In an Executive Order titled, “Blocking the Property of Persons Involved in Serious Human Rights Abuse or Corruption,” President Trump declared “that the prevalence and severity of human rights abuse and corruption . . . have reached such scope and gravity that they threaten the stability of international political and economic systems.” Relying on the Executive Order, on December 21, 2017 the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (“OFAC”) designated 52 persons and entities, thereby making it unlawful for U.S. persons to engage with them in business transactions of any kind absent an OFAC license. Notably, several of the listed individuals have been tied, directly or indirectly, to recent FCPA enforcement actions, including Dan Gertler, Gulnara Karimova, and Ángel Rondón Rijo.

2017 FCPA ENFORCEMENT LITIGATION

DOJ Secures Three FCPA-Related Trial Convictions

As discussed in our 2009 Year-End FCPA Update, in 2009 the then-Assistant Attorney General for the Criminal Division proclaimed that year “the year of the FCPA trial” following four high-profile FCPA trial convictions. The intervening years have seen somewhat more mixed results for DOJ’s FCPA Unit. But 2017 again saw DOJ back on top, securing convictions in three separate trials involving FCPA and FCPA-related charges.

First, as reported in our 2017 Mid-Year FCPA Update, on May 3, 2017 former Guinean Minister of Mines and Geology Mahmoud Thiam was found guilty by a Manhattan federal jury on one count of transacting in criminally derived property and one count of money laundering in connection with the alleged receipt of bribes to secure valuable investment rights in Guinea. The Honorable Denise L. Cote denied Thiam’s motion for a new trial on July 11, and on August 25 sentenced Thiam to seven years’ imprisonment and ordered him to forfeit $8.5 million. Thiam is appealing to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit.

Second, on July 17, 2017, Heon-Cheol Chi, Director of the Korea Institute of Geoscience and Mineral Resources (“KIGAM”) Earthquake Research Center, was convicted by a federal jury in Los Angeles of one count of transacting in criminally derived property associated with payments from two seismological companies with business before KIGAM. The jury did not reach a verdict on the other five money laundering counts with which Chi was charged, which were subsequently dismissed on DOJ’s motion. On October 2, the Honorable John F. Walter sentenced Chi to 14 months in prison, along with a $15,000 fine. Chi is appealing to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit.

Third, on July 27, 2017, Macau billionaire Ng Lap Seng was convicted by a Manhattan federal jury for his role in a scheme to pay more than $1 million in bribes to two U.N. officials in connection with, among other things, a plan to build a U.N.-sponsored conference center in Macau. After a four-week trial, the jury needed only hours to return a verdict finding Seng guilty on all six counts, including FCPA, federal programs bribery, and money laundering charges. Seng has filed a Rule 33 motion for a new trial, which remains pending before the Honorable Vernon S. Broderick. Judge Broderick denied DOJ’s request to revoke bail following the conviction, but has placed Seng on house arrest pending an early 2018 sentencing date.

Och-Ziff Defendants Oppose SEC Disgorgement and Injunctive Relief

In our 2017 Mid-Year FCPA Update we covered the SEC’s civil complaint alleging that former Och-Ziff executive Michael Cohen and analyst Vanja Baros violated the FCPA’s anti-bribery provisions, among other securities law violations. Cohen and Baros have filed separate motions to dismiss arguing, among other things, that the SEC is barred from seeking disgorgement and injunctive relief under the Kokesh decision, in which as discussed above the Supreme Court held that disgorgement is a “penalty” within the meaning of 28 U.S.C. § 2462 and therefore subject to the five-year statute of limitations. Cohen and Baros contend that the bulk of the conduct in the SEC’s complaint is at least 10 years old. Cohen further argues that the SEC’s complaint does not sufficiently allege that he had knowledge of the bribery scheme, while Baros, an Australian citizen living in the United Kingdom, argues that the court does not have personal jurisdiction over him. The SEC opposed the motions to dismiss, and the parties presented oral argument before the Honorable Nicholas G. Garaufis of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York on December 19, 2017. A ruling is pending.

Hearing on Dmitry Firtash’s Motion to Dismiss

As noted in our 2017 Mid-Year FCPA Update, in February 2017 Austria’s Constitutional Court approved the extradition of Ukrainian billionaire Dmitry Firtash to the United States to face FCPA charges that he authorized $18.5 million in bribes to Indian officials. But on December 12, 2017, the extradition was stayed by the Austrian Supreme Court pending Firtash’s request for a new hearing in Austria and request that the Court of Justice of the European Union hear whether the extradition would violate the EU Charter on Human Rights.

Meanwhile, in the U.S. proceedings, Firtash has moved in absentia to dismiss the indictment pending against him in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois, arguing improper venue, that the laws he is charged with violating have no extraterritorial effect, and that “the prosecution is a violation of [his] due process rights because the United States has no legitimate interest in prosecuting the charged conduct.” The Honorable Rebecca R. Pallmeyer heard two days of oral argument in September 2017, which of note featured DOJ FCPA Unit Chief Dan Kahn. A ruling is pending.

Novel Motion to Unseal Indictment by Potential FCPA Defendant

We reported in our 2017 Mid-Year FCPA Update on the curious case of a “John Doe” plaintiff who brought suit against DOJ alleging that DOJ violated his due process rights by accusing him in all but name of participating in the infamous Bonny Island Nigeria corruption scheme. On April 11, 2017, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit affirmed a district court order dismissing the novel claim as barred by the statute of limitations.

Then, on September 29, 2017, “John Doe” Samir Khoury made the even more unorthodox move of filing a motion to unseal and then dismiss an indictment that may or may not have ever been filed against him. Khoury, who is overtly described in public court records only as “LNG Consultant,” contends that the identifying information about his employment history, citizenship, and business relationship with various named parties together have “identified [him] in all respects except by name.” Based on the conduct attributed to him in the charging documents of other defendants, as well as DOJ’s alleged refusal to confirm his status in the investigation, Khoury alleges that it is likely that an indictment has been pending against him under seal of the court since 2009, waiting for him to travel to the United States or another country with an extradition treaty. Khoury contends that this amounts to a violation of his Speedy Trial Act rights and that any indictment must be unsealed and then dismissed as untimely under the applicable statute of limitations.

DOJ attorneys have entered appearances in Khoury’s case, but all further substantive pleadings have been made under seal.

Siemens Defendant Makes Initial Court Appearance; Pleads Not Guilty

In a case nearly as old as the Bonny Island bribery scandal, on December 22, 2017, former Siemens executive Eberhard Reichert appeared in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York and entered a not guilty plea before the Honorable Denise L. Cote. As discussed in our 2011 Year-End FCPA Update, Reichert was one of eight Siemens representatives indicted on FCPA charges in December 2011. Since then, only one other defendant (Andres Truppel) has appeared to answer the criminal charges. Reichert, who was extradited to the United States following his arrest in Croatia in September 2017, was released on bond pending a July 2018 trial date.

2017 FCPA-RELATED SENTENCING DOCKET

Fifteen defendants were sentenced on FCPA and FCPA-related charges in 2017. Sentences ranged from probationary, non-custodial sentences to as high as seven years in prison. Similar to an observation we made in our 2015 Year-End FCPA Update, the data for 2017 show that one of the most pertinent factors in the sentencing of a defendant involved in an FCPA-related prosecution is whether the defendant additionally (or instead) faces a money laundering charge. Whereas the FCPA carries a statutory maximum of five years per violation, the statutory maximum for money laundering is 20 years. Further, the way in which sentences for money laundering offenses are calculated under the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines generally leads to higher advisory prison terms. Although sentences vary by a wide degree depending on the facts of the case, the average prison term in 2017 for FCPA convictions not including a money laundering count was 19 months, whereas the average of FCPA-related convictions including a money laundering count was more than one-and-a-half times that, at 33.5 months.

The sentences imposed in FCPA and FCPA-related cases in 2017 follow:

|

Defendant |

Sentence |

Date Sentenced |

Date Charged |

Court (Judge) |

Comment |

$ Laundering Conviction? |

|

Ernesto Hernandez Montemayor |

24 months |

01/23/2017 |

11/06/2015 |

S.D. Tex. (Bennett) |

$2 million forfeiture |

Yes (no FCPA charge) |

|

Kamta Ramnarine |

3 years’ probation |

02/02/2017 |

08/15/2016 |

S.D. Tex. (Hinojosa) |

|

No |

|

Daniel Perez |

3 years’ probation |

02/02/2017 |

08/15/2016 |

S.D. Tex. (Hinojosa) |

|

No |

|

Victor Hugo Valdez Pinon |

12 months, 1 day |

03/02/2017 |

09/15/2016 |

S.D. Tex. (Bennett) |

$90,000 restitution + $275,000 forfeiture |

No |

|

Douglas Ray |

18 months |

04/17/2017 |

09/15/2016 |

S.D. Tex. (Bennett) |

$590,000 in restitution + $2.1 million forfeiture |

No |

|

Samuel Mebiame |

24 months |

06/14/2017 |

08/12/2016 |

E.D.N.Y. (Garaufis) |

|

No |

|

Dmitrij Harder |

60 months |

07/19/2017 |

01/06/2015 |

E.D. Pa. (Diamond) |

$100,000 fine + $1.9 million forfeiture |

No |

|

Mahmoud Thiam |

84 months |

08/28/2017 |

12/12/2016 |

S.D.N.Y. (Cote) |

$8.5 million forfeiture |

Yes (no FCPA charge) |

|

Frederic Pierucci |

30 months |

09/25/2017 |

11/27/2012 |

D. Conn. (Arterton) |

$20,000 fine |

No |

|

Amadeus Richers |

~ 8 months |

09/27/2017 |

12/04/2009 |

S.D. Fla. (Martinez) |

Extradited from Panama |

No |

|

Heon-Cheol Chi |

14 months |

10/02/2017 |

12/12/2016 |

C.D. Cal. (Walter) |

$15,000 fine |

Yes (no FCPA charge) |

|

Malcolm Harris |

42 months |

10/05/2017 |

12/15/2016 |

S.D.N.Y. (Ramos) |

$760,000 restitution + $500,000 forfeiture |

No (no FCPA charge) |

|

Boris Rubizhevsky |

12 months, |

11/13/2017 |

10/29/2014 |

D. Md. (Chuang) |

$26,500 forfeiture |

Yes (no FCPA charge) |

|

Eduardo Betancourt |

12 months, |

12/21/2017 |

02/02/2016 |

S.D. Tex. (Harmon) |

$150,000 restitution |

No (no FCPA charge) |

|

Franklin Marsan |

12 months, |

12/21/2017 |

02/02/2016 |

S.D. Tex. (Harmon) |

$150,000 restitution |

No (no FCPA charge) |

2017 KLEPTOCRACY FORFEITURE ACTIONS

For years we have been following DOJ’s Kleptocracy Asset Recovery Initiative, spearheaded by DOJ’s Money Laundering and Asset Recovery Section, which uses civil forfeiture actions to freeze, recover, and, in some cases, repatriate the proceeds of foreign corruption. 2017 saw increased coordination between attorneys from this section and DOJ’s FCPA Unit, as frequently they have been appearing in one another’s enforcement actions, working hand-in-glove across section lines.

In our 2016 Year-End and 2017 Mid-Year FCPA updates, we reported on DOJ’s massive civil forfeiture action seeking to recover more than $1 billion in assets associated with Malaysian sovereign wealth fund 1Malaysia Development Berhad (“1MDB”). In September 2017, however, DOJ obtained an indefinite stay of the forfeiture actions pending before the Honorable Dale S. Fischer of the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California because of concerns the civil forfeiture actions could jeopardize DOJ’s ongoing criminal investigation.

In another significant civil forfeiture action, on July 14, 2017, DOJ announced the filing of a complaint to seize and forfeit $144 million in proceeds of alleged corruption involving Nigeria’s former Minister for Petroleum Resources, Diezani Alison-Madueke, and Nigerian businessmen Kolawole Akanni Aluko and Olajide Omokore. The assets named in the complaint include most prominently an $80 million yacht and a $50 million Manhattan apartment. Various parties have made an appearance in the action and asserted an interest in the property to be seized, including the Federal Republic of Nigeria.

2017 FCPA-RELATED PRIVATE CIVIL LITIGATION

Despite the fact that the FCPA does not provide for a private right of action, civil litigants have long used a variety of causes of action, with varying degrees of success, to pursue private redress for losses allegedly associated with FCPA-related misconduct.

Shareholder Lawsuits

Shareholder litigation all too frequently follows a company’s announcement of an FCPA-related event, either through a class action lawsuit brought on behalf of shareholders whose stock value has dropped, allegedly as a result of the misconduct, or a shareholder derivative lawsuit brought against the company’s directors for allegedly violating their fiduciary duties to run the business in a compliant manner. Examples with significant developments during the second half of 2017 include:

- Braskem S.A. – On September 14, 2017, Brazilian chemical company Braskem agreed to a settle a class action lawsuit with a payment of $10 million to investors who alleged that the company committed securities fraud by misleading them regarding its role in the Operation Car Wash scandal. As covered in our 2016 Year-End FCPA Update, Braskem pleaded guilty in December 2016 to conspiring to violate the FCPA’s anti-bribery provisions. The Honorable Paul A. Engelmayer of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York has granted preliminary approval to the settlement, with a final settlement hearing scheduled for February 2018.

- Och-Ziff Capital Mgmt. Group LLC – On September 29, 2017, the Honorable J. Paul Oetken of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York for the second time dismissed certain securities fraud claims against Och-Ziff and senior executives alleging, among other things, that they failed to timely disclose the investigation that led to the DOJ/SEC FCPA resolution covered in our 2016 Year-End FCPA Update. Other claims were allowed to proceed to discovery. Plaintiffs’ motion to certify a class of investors is now fully briefed and awaiting disposition.

- Sinovac Biotech Ltd. – On July 3, 2017, shareholders of vaccine developer Sinovac Biotech filed a putative class action lawsuit in the U.S. District Court for the District of New Jersey alleging that the company misled investors about its corrupt business dealings in China. The action came in the wake of a 2016 report published by a financial research firm that Sinovac’s CEO had bribed a Chinese official to obtain vaccine approval. The report prompted an SEC investigation, later joined by DOJ, which allegedly caused the company’s stock price to drop. On September 6, 2017, the named plaintiff voluntarily dismissed the action, which the court granted without prejudice.

- VimpelCom Ltd. – In late 2015, a putative class of investors sued VimpelCom (now VEON Ltd.) alleging violations of the federal securities laws after the company’s stock price dropped following revelations of the investigation leading to the FCPA resolution covered in our 2016 Mid-Year FCPA Update. Among the allegations, the plaintiffs contend that VimpelCom made material misstatements and omissions in its SEC filings, including referencing an increase in the company’s subscriptions and revenue in Uzbekistan without disclosing that this was, at least in part, a result of bribery. On September 19, 2017, the Honorable Andrew L. Carter, Jr. of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York denied VimpelCom’s motion to dismiss most of the claims. The company is scheduled to file an answer to the complaint in early 2018.

Civil Fraud Actions

Associação Brasileira De Medicina De Grupo (“Abramge”), an association of Brazilian health insurers, has filed civil fraud and conspiracy complaints in various federal district courts against numerous medical device companies, including Abbott Laboratories, Inc. (Northern District of Illinois), Arthrex, Inc., Boston Scientific Corporation, and Zimmer Biomet Holdings (District of Delaware), and Stryker Corporation (Western District of Michigan). Abramge alleges that the defendants, which it dubs “the Prosthetic Mafia,” engaged in corrupt practices that inflated prices for medical devices ultimately reimbursed by the association’s members.

Abramge filed a motion with the Judicial Panel on Multidistrict Litigation, seeking to consolidate the actions before one court. This motion was denied by the Panel on May 31, 2017, on the grounds that the allegations in each case were distinct enough, and the number of actions few enough, to proceed with the cases separately. In the Stryker case, on June 28, 2017, the Honorable Robert J. Jonker dismissed the action on the doctrine of forum non conveniens, holding that the fraud allegations belong in Brazilian, not American, court. Not long after, Abbott Laboratories consented to jurisdiction in Brazil and Abramge voluntarily dismissed its U.S. lawsuit on August 29, 2017. Arthrex, Boston Scientific, and Zimmer Biomet have moved to dismiss the case in Delaware, which motion is pending.

Another civil fraud action with ties to international corruption allegations concerns the lawsuit of husband and wife private investigators Peter Humphrey and Yu Yingzeng against their former client GlaxoSmithKline plc (“GSK”). As we reported in our 2014 Year-End FCPA Update, Humphrey and Yu were convicted in Chinese court and spent more than a year in Chinese prison for illegally obtaining private information while investigating a corruption-related whistleblower claim on behalf of GSK. In November 2016, they brought a Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (“RICO”) Act lawsuit against their former client, alleging that the company misled them into believing that the whistleblower’s claims were false and failed to disclose that the whistleblower had powerful connections in China. On September 29, 2017, the Honorable Nitza I. Quiñones Alejandro of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania granted GSK’s motion to dismiss the complaint in its entirety, holding that Humphrey and Yu did not suffer a domestic injury and RICO does not cover injuries that occurred entirely outside of the United States.

Corruption as Support of Terrorism Allegations

On October 17, 2017, scores of American service members and their families filed an Anti-Terrorism Act lawsuit in U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia against five healthcare companies and various subsidiaries alleging a pattern of corruption in Iraq that ultimately funded a terrorist organization. Specifically, plaintiffs allege that between 2005 and 2009 the defendant entities provided extra “in-kind” goods to the Iraqi Ministry of Health, beyond those called for in contracts, which goods were then sold on the black market to support the Jaysh al-Mahdi, which purportedly controlled the Ministry of Health during this period of conflict in Iraq. Defendants’ response to the complaint is currently due in February 2018.

Breach of Contract Litigation

On March 23, 2017, Cicel (Beijing) Science & Technology Co. Ltd. filed a breach of contract action against Misonix, Inc. in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York. Misonix argued that it terminated Cicel, its Chinese distributor, after discovering potentially corrupt conduct and disclosing the same to DOJ and the SEC. Cicel claimed this justification was a pretext and nevertheless that Misonix breached the parties’ contractual arrangement by terminating the relationship. On October 7, 2017, the Honorable Arthur D. Spatt denied Misonix’s motion to dismiss the breach of contract claim, allowing the case to proceed to discovery.

2017 INTERNATIONAL ANTI-CORRUPTION DEVELOPMENTS

World Bank Integrity Vice Presidency

Pascale Hélène Dubois is now the leader of World Bank Group Integrity Vice Presidency (“INT”), a unit that plays an important role in global anti-corruption enforcement. INT kept an active docket under Dubois’s leadership in Fiscal Year 2017, sanctioning 60 entities and individuals, honoring 84 cross-debarments from other development banks, and making 456 referrals to national authorities in more than 100 countries.

World Bank investigations and sanctions proceedings can at times place targets involved in parallel criminal proceedings in a difficult spot. That tension was on display in Sanctions Board Decision No. 93, issued June 2, 2017. The respondent was charged with obstruction after refusing to allow INT to audit its records, asserting that the audit would compromise its right against self-incrimination in the context of a pending criminal charge. The Sanctions Board, however, upheld the INT sanction, concluding that the respondent could not use the right against self-incrimination to avoid its contractual obligations to the World Bank. This case is part of a larger World Bank and criminal inquiry involving Wassim Tappuni, a former World Bank consultant who, as discussed below, was convicted in July 2017 in the United Kingdom for his involvement in a scheme to defraud World Bank and U.N. Development Programme projects.

United Kingdom

As we will cover in significantly greater detail in our forthcoming 2017 Year-End UK White Collar Crime Update, to be released on January 8, 2018, the year 2017 was a record for UK anti-corruption enforcement. Including the domestic bribery cases prosecuted under the UK Bribery Act 2010, 27 individuals were convicted and three companies concluded enforcement actions, two with convictions and one with a deferred prosecution agreement. To assist our clients with these challenges, we are pleased to announce that Sacha Harber-Kelly has joined the firm as a partner after working at the SFO for many years. A brief summary of the international anti-corruption actions follows.

In our 2017 Mid-Year UK White Collar Crime Update, we reported that the UK Serious Fraud Office (“SFO”) had announced charges against F.H. Bertling Limited and seven individuals relating to an alleged conspiracy to pay $250,000 to an agent of Angolan state oil company Sonangol. Between September 2016 and August 2017, the SFO secured guilty pleas by F.H. Bertling and six of the individuals for conspiracy to make corrupt payments, in violation of section 1 of the Criminal Law Act 1977 and section 1 of the Prevention of Corruption Act 1906. On October 20, 2017, three of the individuals were given suspended 20-month prison sentences, fined £20,000, and disqualified from serving as company directors for five years. The only defendant to take his case to trial was acquitted by a jury at Southwark Crown Court on September 21, 2017.

In November 2017, the SFO announced Prevention of Corruption Act 1906 charges against five individuals in its ongoing investigation of contracts awarded by Unaoil to SBM Offshore in Iraq. Three of the individuals are former Unaoil employees—Ziad Akle, Basil Al Jarah, and Saman Ahsani—and two are former SBM Offshore employees—Paul Bond and Stephen Whiteley.

On July 25, 2017, World Bank and U.N. Development Programme consultant Wassim Tappuni was convicted by a jury at Southwark Crown Court of corruption-related charges associated with his receipt of £1.7 million in bribes to skew his evaluation and otherwise to subvert the competitive process of the tenders he oversaw. Tappuni was sentenced to six years’ imprisonment on September 22, 2017.

Rest of Europe

France

As reported in our 2017 Mid-Year FCPA Update, Teodoro Nguema Obiang Mangue, the son of the President and himself Second Vice President of Equatorial Guinea, went on trial in France for allegedly embezzling more than $112 million from his home country. In October 2017, Obiang was convicted, fined €30 million, given a suspended three-year prison sentence, and had his assets in France confiscated.

Greece

In our 2014 Year-End and 2015 Mid-Year FCPA updates, we reported on the indictment of 64 individuals in the Siemens – OTE corruption case. On July 28, 2017, an Athens appeals court found former Greece Transport Minister Tassos Mantelis guilty of money laundering in connection with payments by Siemens’s Greek branch in 1998 and 2000 to secure contracts to digitalize phone lines for the then state-owned Greek telecom. The court found that some 450,000 Deutsche Marks were transferred to an account controlled by Mantelis as a kickback, rather than as a campaign contribution as Mantelis had claimed. Another defendant, Ilias Georgiou, a former Siemens executive in Greece, was convicted of money laundering and bribery in connection with his role in transferring the funds to Mantelis. Aristidis Mantas, a former Mantelis aide, also was convicted of complicity in the money laundering scheme but was acquitted of complicity to bribe.

Italy

On December 20, 2017, an Italian judge granted the Milan Public Prosecutor’s Office’s request to indict oil and gas giants Royal Dutch Shell and Eni—as well 11 of the companies’ current and former executives, including current Eni CEO Claudio Descalzi and former Shell UK Chairman Malcolm Brinded—on corruption charges associated with a $1.3 billion deal for oil exploration rights in an offshore block in Nigeria. Among other things, prosecutors allege that $520 million from the 2011 deal was converted to cash for payments to then-Nigerian president Goodluck Ebele Azikiwe Jonathan and other officials. The Nigerian government seized the offshore block in January 2017. Shell, Eni, and the individuals have denied wrongdoing, and the case is currently scheduled to go to trial beginning in March 2018.

Portugal

In July 2017, the Portuguese Public Prosecutor’s Office filed corruption and forgery charges against four former TAP Airlines employees, including former TAP board member Fernando Sobral, in connection with up to €25 million in payments allegedly received from SonAir, an Angolan air transport provider. Prosecutors allege that, between 2008 and 2009, SonAir paid TAP for aircraft maintenance services that were never provided, laundering the money through an intermediary that took a 75% commission before funneling the remaining funds to offshore accounts owned by SonAir. Prosecutors also charged three lawyers accused of assisting with money laundering. Notably, the conduct came to light during an internal audit and internal investigation by TAP, after which it self-reported to prosecutors in Lisbon.

Russia

On July 1, 2017, President Vladimir Putin signed into law a measure establishing a register of government employees terminated due to corruption. Although there is no provision that would affirmatively prevent these individuals from occupying government positions, the Presidential Administration expects the publication of the register will assist in screening government service candidates. In addition, to improve corporate anti-corruption compliance, the Ministry of Labor and the Ministry of Economic Development of the Russian Federation proposed a federal bill that, starting in 2019, would require companies to implement anti-corruption measures in accordance with federal anti-corruption standards.

Sweden

We reported in our 2017 Mid-Year FCPA Update on the March 2017 arrest of Evgeny Pavlov by Swedish authorities for suspected bribery in connection with helping his former employer, aerospace and transportation company Bombardier, secure a $350 million railway contract in Azerbaijan. On October 11, 2017, a Swedish court found Pavlov not guilty. Nevertheless, Sweden’s National Anti-Corruption Unit continues to investigate five other Bombardier employees referenced in the prosecution’s case against Pavlov. In addition, Swedish prosecutors have charged three former Telia executives—former CEO Lars Nyberg, former deputy CEO and head of Eurasia Tero Kivisaari, and former general counsel for Eurasia Olli Tuohimaa—in connection with the Uzbek telecommunications corruption scandal described above.

The Americas

Argentina

We have been covering in recent years corruption-related prosecutions of political luminaries at the highest levels of the Argentinian government. This year was no exception, with the indictment of former President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and her former Vice President, Amado Boudou. On the legislative front, the Corporate Liability Bill is now law. The Bill imposes criminal liability on corporations (in addition to individuals) for certain crimes against the government, including bribery, foreign corruption, and falsifying balance sheets. Fines of two-to-five times the illegal gains may be imposed, in addition to potential suspension and debarment from government contracts. Pursuant to the Bill, companies may avoid prosecution by voluntarily self-disclosing the conduct, demonstrating an effective compliance program, and disgorging profits. Moreover, even if unable to avoid prosecution entirely, companies can negotiate leniency agreements and obtain up to a 50% discount off the bottom end of the applicable fine range if they provide information that leads to uncovering all relevant facts.

Brazil

Even in the face of significant political turmoil, the long-running Lava Jato (Car Wash) investigation into allegations of corruption related to contracts with Petrobras and other state-owned entities continues. Following perhaps the most notable conviction arising from the investigation to date, former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva was sentenced on July 12, 2017 to 9.5 years in prison after he was found guilty of accepting bribes. Brazilian authorities have now charged more than 375 individuals and obtained 177 convictions, with total sentences of more than 1,750 years in prison.

Despite, or perhaps because of, this success, tension has arisen over potential efforts to curb the investigation. In May 2017, President Michel Temer appointed a close political ally, Torquato Jardim, to head the Ministry of Justice, which oversees the Federal Police. In July 2017, the Federal Police announced it would shut down the Car Wash Task Force and absorb its members into a broader anti-corruption unit, a move that prompted widespread objections. More recently, former Prosecutor General Rodrigo Janot, whom Temer replaced in mid-September, alleged that the personnel changes were part of an effort to divert graft investigations. In the months before leaving his post, Janot charged Temer with corruption, obstruction of justice, and criminal conspiracy. Temer avoided standing trial, however, after twice lobbying Brazil’s Congress to block his prosecution.

2017 also saw Brazilian authorities continue to investigate other instances of alleged corruption. In September, Joesley Batista, one of the owners of Brazilian meatpacker JBS S.A., surrendered to police after a court revoked the immunity granted to him under a previous plea deal described in our 2017 Mid-Year FCPA Update. JBS executive Ricardo Saud also was arrested. Then-Prosecutor General Janot sought the arrests after Batista’s attorneys inadvertently produced a recording of Batista and Saud discussing crimes not covered by the plea deal. In another prominent case, in October 2017, the head of Brazil’s Olympic Committee, Carlos Arthur Nuzman, and the Director of Operations for the Rio de Janeiro Olympic Games, Leonardo Gryner, were detained on suspicion that they paid bribes to ensure Rio de Janeiro’s selection to host the 2016 Summer Games. Former governor of Rio de Janeiro State Sérgio Cabral and Brazilian businessman Arthur César de Menezes Soares Filho also have been accused of involvement, and Cabral has been sentenced to a total of more than 87 years in prison in connection with Operation Car Wash.