January 23, 2018

As 2016 came to a close, pharmaceutical and medical device companies waited expectantly and wondered aloud about what 2017 and the arrival of the Trump Administration would bring. With 2017 behind us, we now have initial indications—and some answers—about what the arrival of this new Administration means for drug and device companies.

On the enforcement front, the Department of Justice (“DOJ”), the Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General (“HHS OIG”), and the Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”) showed no signs of scaling back their efforts. Instead, 2017 marked yet another year of massive recoveries from drug and device companies to settle the standard mélange of allegations under the False Claims Act (“FCA”), Anti-Kickback Statute (“AKS”), Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (“FDCA”), Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (“FCPA”), and other enforcement statutes. Although some of these settlements were leftovers from the Obama Administration, we have seen no evidence that the enforcement agencies are pulling punches under President Trump.

On the regulatory front, meanwhile, the picture is more complicated. On the one hand, pharmaceutical and medical device companies have yet to see the type of regulatory roll-back that the Trump Administration has promised—and started to deliver—in certain other industries. On the other hand, there have been nascent efforts by the new Administration to reign in burdensome regulations. For example, the Administration has undertaken efforts to streamline review processes for medical devices. As the new Administration hits its stride, and (perhaps) leaves the oxygen-consuming debate over repeal of the Affordable Care Act in the past, it remains to be seen just how much regulatory relief pharmaceutical and medical device companies can expect.

Below, we cover the most important regulatory and enforcement developments affecting drug and device manufacturers. As in past updates, we begin with an overview of government enforcement efforts against drug and device companies under the FCA, the FDCA, and other laws. We then address evolving regulatory guidance and action on topics of note to drug and device companies: promotional activities, manufacturing practices, and the AKS. And we conclude with a discussion of developments of particular note to device manufacturers.

As always, we would be happy to discuss these developments—and their implications for your business—with you.

I. DOJ ENFORCEMENT IN THE PHARMACEUTICAL AND MEDICAL DEVICE INDUSTRIES

Despite a new Administration, DOJ remains committed to enforcing the FCA and other statutes against entities in the health care industry, and in the drugs and devices sectors in particular. In sum, DOJ obtained more than $3.7 billion in civil settlements and judgments under the FCA during the 2017 fiscal year.[1] With nearly 800 new FCA cases filed in 2017 and roughly $1.5 billion in federal recoveries alone from drug and device companies,[2] DOJ (and qui tam relators) have shown no sign of turning their attention elsewhere.

FCA resolutions continue to drive the government’s recoveries from drug and device companies. In 2017, those resolutions included Shire Pharmaceuticals LLC’s settlement for more than $200 million in January and Mylan Inc.’s $465 million settlement in August.

Although recent federal FDCA and FCPA enforcement activity against drug and device companies has been relatively quiet, several of DOJ’s FCA resolutions involved FDCA-related allegations, and several high-profile FCPA investigations continue apace. We address these and other notable developments in the enforcement arena, including the Trump Administration’s efforts to address the opioid crisis, in more detail below.

A. False Claims Act

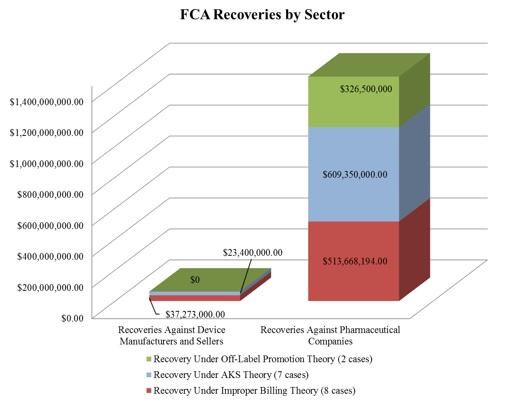

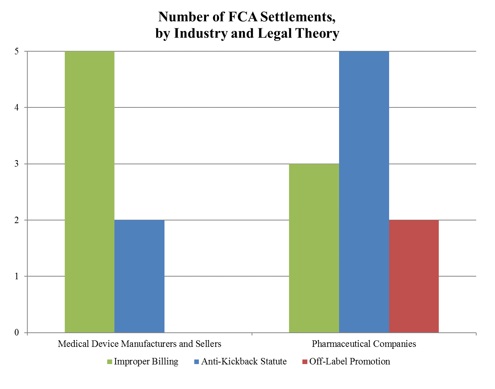

Surpassing last year’s recoveries of $1.4 billion, approximately $1.5 billion of the FCA recoveries in 2017 stemmed from resolutions with drug and device manufacturers. The total number of FCA cases settled by DOJ with these manufacturers (16) nearly matched that from last year (15), but the proportion of device-to-pharmaceutical settlements flipped. In comparison with last year, in which DOJ settled twice as many cases against device manufacturers as against pharmaceutical manufacturers, DOJ settled 9 cases with pharmaceutical companies and only 6 cases with device manufacturers in 2017. In addition, the vast majority of DOJ’s settlement recoveries this year—over 95%—resulted from cases against pharmaceutical companies.[3]

As illustrated below,[4] DOJ continues to pursue FCA actions under multiple theories, including improper billing resulting from alleged violations of various federal health care program rules, illegal kickbacks under the AKS, and, to a much lesser extent, off-label promotion. Of note, there were no off-label promotion recoveries this year against device manufacturers.

1. Settlements in FCA Matters Relating to Federal Health Program Rules

The largest recovery of the past six months came from DOJ’s settlement in August with Mylan Inc. and Mylan Specialty L.P. (collectively “Mylan”).[5] Mylan, which markets numerous drugs and devices including EpiPen, agreed to pay $465 million to resolve allegations that it knowingly misclassified EpiPen as a generic drug to avoid paying rebates under the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (and also secured large increases in the price of the drug on the private market).[6] As part of the settlement, Mylan agreed to enter into a five-year corporate integrity agreement requiring independent annual review of its Medicaid drug rebate program practices.[7] The case originated with a complaint by another pharmaceutical manufacturer, Sanofi-Aventis US LLC, which will receive approximately $38.7 million from the federal recovery.[8]

In September, drug maker Aegerion also agreed to pay more than $35 million to settle allegations that it violated the FCA, FDCA, and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (“HIPAA”) through activities associated with its drug, Juxtapid.[9] As described in further detail below, the government alleged that the drug was misbranded due to the company’s failure to comply with a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (“REMS”). According to the government, the company caused the submission of false claims through its alleged promotion of the drug for patients for whom the drug was not indicated, purportedly false and misleading statements to doctors regarding the appropriateness of using the drug for certain patients, and alleged falsification of medical necessity statements and prior authorizations submitted to federal health care programs.[10] The settlement also resolved allegations that the company paid patients’ copay obligations with funds channeled through a purported non-profit patient assistance organization. Of the total settlement, $28.8 million will go toward the resolution of federal and state FCA charges. Further, Aegerion entered into a separate deferred prosecution agreement to resolve criminal allegations that it conspired to obtain patient health information for commercial gain without patient authorization in violation of HIPAA.[11]

2. Settlements in AKS-Related FCA Matters

As reported in our Mid-Year Update, 2017 began with the largest-ever FCA recovery in a kickback case involving a medical device. Significant AKS-related enforcement actions in the latter half of 2017 included United Therapeutics’ $210 million settlement. From 2010 to 2014, a tax-exempt non-profit foundation purportedly used donations made by the Maryland-based pharmaceutical company to pay Medicare patient copays for the company’s pulmonary arterial hypertension drugs; according to the government, this amounted to inducing patients to purchase the company’s drugs.[12] The government claimed that, when deciding on donations, United Therapeutics obtained data from the foundation detailing the amounts spent by the foundation on patients who were using each of the company’s drugs. The settlement is just one of a number of recent developments reflecting increased scrutiny of patient assistance programs by DOJ and HHS OIG, discussed further in Section V below.

In addition to the settlement with Aegerion discussed above, DOJ reached two other notable AKS-related settlements with pharmaceutical and medical device companies in the last six months of 2017:

- In August, the government agreed to a $12 million settlement with Sightpath Medical, Inc., TLC Vision Corporation, and their former CEO, James Tiffany.[13] According to the complaint, Sightpath and Cameron-Ehlen Group (the subject of an underlying lawsuit that the government likewise joined) allegedly provided kickbacks to ophthalmologists in the form of luxury ski vacations and other high-end fishing, golfing, and hunting trips to persuade the physicians to use the companies’ intraocular lenses and ophthalmic surgical equipment.[14]

- In September, Galena Biopharma agreed to pay more than $7.55 million to resolve allegations that it induced doctors to prescribe its fentanyl-based drug Abstral through free meals, speaker fees, and an advisory board planned and attended by Galena’s sales team, as well as through payments to a physician-owned pharmacy under a performance-based rebate agreement.[15] The government also contended that Galena compensated doctors for referring patients to Galena’s RELIEF patient registry study—purportedly a sham program designed to obtain data on patients’ experiences with the company’s drug.[16] Two of the doctors who allegedly received the kickbacks have been tried and convicted in the Southern District of Alabama for offenses related to their subsequent prescribing of the drug.[17]

3. Resolution of Off-Label Promotion Investigations

As reported in last year’s Year-End Update, developing case law has imposed potentially significant First Amendment obstacles to the enforcement of off-label promotion claims under the FCA. In spite of this trend, however, DOJ has continued to recover settlements based on off-label theories.

In July, for example, New Jersey-based pharmaceutical manufacturer Celgene Corp. agreed to a $280 million settlement to resolve allegations that the company promoted two of its cancer drugs for uses that were not approved by FDA or covered by federal and state health care programs.[18] The settlement also resolved allegations that Celgene paid kickbacks to physicians and made false and misleading statements about the drugs.

The government also reached a settlement with pharmaceutical manufacturer Novo Nordisk, Inc. in early September. In addition to alleged FDCA violations discussed in further detail below, the settlement resolved allegations that the company promoted its Type II diabetes drug Victoza for use by adult patients who do not suffer from Type II diabetes—a use that FDA had not approved as safe and effective.[19] Roughly $47 million of the $58 million total settlement will go towards resolving FCA allegations under theories of off-label promotion and other purported conduct.[20]

4. Developments in the Implied Certification Theory’s Materiality Requirement

Our 2016 Year-End and 2017 Mid-Year Updates discussed at length recent efforts to interpret the materiality requirement set forth by the Supreme Court in Universal Health Services, Inc. v. United States ex rel. Escobar, 136 S. Ct. 1989 (2016). In particular, courts have continued to grapple with what, if any, impact continued government payments may have on the materiality analysis. As recent case law developments have shown, how lower courts interpret Escobar will have particular relevance to drug and device companies, who are subject to a wide range of regulatory requirements that are steps removed from government payment but potentially could be subject to FCA actions under an implied certification theory.

In September, the Fifth Circuit issued a per curiam opinion in United States ex rel. King v. Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc. hinting at potential new materiality obstacles that courts might erect in the way of the government or relators attempting to prove materiality in off-label cases under the FCA. Among other purported violations, the relator in King alleged that the defendant caused false claims to be submitted under the FCA by promoting three of its drugs for off-label uses.[21] Despite supposed evidence that the company discussed off-label drug uses with physicians and sponsored off-label use studies, the court found there was insufficient evidence to show that the company’s actions caused any false claims.[22]

Affirming the district court’s grant of summary judgment as to the off-label claims on those grounds, the court went further, suggesting that it harbored doubts that mere allegations of off-label promotions would satisfy Escobar‘s materiality standard.[23] Because “Medicaid pays for claims without asking whether the drugs were prescribed for off-label uses or asking for what purpose the drugs were prescribed[,]” and “given that it is not uncommon for physicians to make off-label prescriptions,” the Fifth Circuit reasoned that “it is unlikely that prescribing off-label is material to Medicaid’s payment decisions under the FCA.”[24] Although dicta, those comments build upon the Supreme Court’s holding in Escobar that certain federal health care program requirements are not material where the government pays the claims despite knowing of violations of these requirements.[25] Further, the Fifth Circuit’s observation may suggest it is receptive to arguments that failure of the government to take affirmative steps in assessing reimbursement requirements could undermine its materiality arguments. In any event, King may prove a strong foothold for drug and device makers battling FCA claims predicated upon alleged off-label promotion in Medicaid and similar cases.

The Supreme Court soon may have occasion to elaborate on the materiality requirements outlined in Escobar and on the implications of government action—or inaction—in particular. In a recent petition for certiorari, Gilead Sciences asked the Supreme Court to review the Ninth Circuit’s decision in United States ex rel. Campie v. Gilead Sciences, Inc.

As discussed in our 2017 Mid-Year Update, the relators in that case alleged that Gilead fraudulently obtained approval for certain of its drugs by making false statements to FDA about the manufacturing source of the drugs’ active ingredient and purported later contamination by that supplier.[26] After finding that the defendant’s proprietary drug names could constitute actionable “specific representations,” and after concluding that fraud on one agency constitutes fraud on a separate agency as long as the two are “overseen” by the same cabinet secretary,[27] the court concluded that the relators adequately pled materiality. Reasoning that “FDA approval is ‘the sine qua non‘ of federal funding here” and noting that the company had stopped using the manufacturing site in question, the Ninth Circuit rejected Gilead’s arguments focusing on the government’s continued drug reimbursements even after relators brought suit. The Ninth Circuit also determined it was premature to decide whether the government paid despite knowing of the defendant’s noncompliance.[28] Gilead’s petition for certiorari focuses narrowly on whether the government’s decision to continue reimbursement even “after learning of alleged regulatory infractions” would suffice to undermine the relators’ materiality arguments.[29] Gilead takes issue with the potential impact on defendants’ ability to dismiss a complaint on materiality grounds at the motion to dismiss stage, as contemplated by Escobar.[30] Given the brewing disagreement among federal circuit and district courts as to how to apply Escobar‘s materiality standard, the Supreme Court may well seize this opportunity to provide clarity on the subject of materiality and government knowledge.

5. Rule 9(b) Particularity

As detailed in our 2017 Mid-Year Update, federal circuit and district courts also have continued to take differing approaches as to how Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 9(b)’s heightened pleading requirements should be applied to FCA claims at the motion to dismiss stage. Rule 9(b) requires FCA plaintiffs to plead allegations with particularity. But questions about the extent of detail required to meet this standard have remained open to debate, especially in cases against drug and device manufacturers where there are allegations about the manufacturers’ conduct but scant details about the claims submitted by third-party physicians or pharmacies.

The Sixth Circuit recently addressed this issue in United States ex rel. Ibanez v. Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., in affirming the lower court’s dismissal and denying leave to amend where relators failed to plead a specific, representative false claim submitted to the government for payment.[31] Brought by former employees, the case involved allegations that Bristol-Myers Squibb and Otsuka America Pharmaceuticals Inc. engaged in an illegal nationwide scheme to promote the antipsychotic drug Abilify for off-label uses.[32] Although the relators alleged some details regarding the purported promotional scheme, the lower court nonetheless dismissed the relators’ suit after finding that they failed to allege at least one representative claim submitted to the government that stemmed directly from the defendants’ allegedly illegal practices.[33]

The Sixth Circuit agreed with the district court and refused to apply the “personal knowledge” exception to the Circuit’s otherwise strict application of Rule 9(b)’s particularity requirements. Because the relators’ allegations only involved personal knowledge of an allegedly fraudulent scheme rather than of the defendant’s billing practices, the Sixth Circuit refused to allow the complaint to proceed based solely on other “reliable indicia” that claims actually were submitted.[34] In so holding, the Sixth Circuit explained that the complaint must “adequately allege the entire chain—from start to finish—to fairly show defendants cause[d] false claims to be filed,” including any “specific intervening conduct” along the chain.[35] For example, the complaint must allege that a physician targeted by the allegedly improper promotion “prescribed the medication for an off-label use or because of an improper inducement,” a patient filled the prescription, and the filling pharmacy submitted a claim “for reimbursement on the prescription.”[36] The court also held that the relator’s proposed third amended complaint similarly failed to provide sufficient allegations to meet either the relaxed or strict particularity requirements.[37]

Another FCA case from the First Circuit charted a different course in evaluating Rule 9(b)’s particularity standard. In United States ex rel. Nargol v. DePuy Orthopaedics, Inc., the relators alleged that Depuy Orthapaedics, Inc., and related entities caused third parties to submit fraudulent claims after purportedly distributing implants with latent defects.[38] Although the First Circuit typically has applied a “strict” Rule 9(b) pleading standard, the court accepted that a complaint can meet Rule 9(b) requirements where it “essentially alleges facts showing that it is statistically certain that [the defendant] cause[d] third parties to submit many false claims to the government.”[39] Although the complaint did not allege specific information regarding submitted claims, the court reasoned that the doctors would not have been on notice not to subsequently bill federal health care programs since there was no reason to believe that anyone other than the defendants knew of the purported defects or that they could have been readily discovered during surgery.[40] According to the First Circuit, because doctors presumably sought reimbursement for the defective devices, every sale of the devices likely “was accompanied by an express or plainly implicit representation” that the product was FDA-approved and not a “materially deviant version,” and because it was “highly likely” that uninsured patients did not bear the expense in most cases, it was “virtually certain that the insurance provider in many cases was Medicare, Medicaid, or another government program.”[41] As such, the court distinguished the alleged scheme from other off-label promotion allegations and agreed that a different, “more flexible” Rule 9(b) standard of particularity was appropriate.[42] Because the complaint alleged “the details of the scheme with reliable indicia that le[]d to a strong inference that claims were actually submitted,” the court overturned the district court’s dismissal of the relators’ claim.[43]

B. Developments in Enforcement Actions Against Opioid Manufacturers and Distributors

The nation’s opioid crisis and promises by the Trump Administration to take a more aggressive approach triggered a new DOJ initiative in 2017. Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced the formation of the Opioid Fraud and Abuse Detection Unit—a DOJ pilot program aimed at “ulitiz[ing] data to help combat the devastating opioid crisis that is ravaging families and communities across America.”[44] To aid this mission, DOJ announced that it has selected twelve districts across the country to participate in the program and has assigned a dozen prosecutors to focus entirely on investigating and prosecuting opioid-related health care fraud cases.[45] Attorney General Sessions also announced increased funding for state and local law enforcement agencies,[46] as well as plans to designate “opioid coordinators” in each U.S. Attorney’s Office to advance DOJ’s “anti-opioid mission[.]”[47]

The widespread DOJ scrutiny of opioid manufacturers and distributors already has led to several public enforcement actions. In October, DOJ announced its first ever indictments against Chinese manufacturers of Fentanyl and other opioid substances.[48] The indictments charge two Chinese nationals and their North American-based distributor counterparts with conspiracies to distribute large quantities of Fentanyl, Fentanyl analogues, and other opiate substances throughout the United States.[49] Both Chinese nationals face potentially significant jail time and millions of dollars in fines.[50]

Soon after, DOJ announced the arrest of John N. Kapoor—the founder and majority owner of Insys Therapeutics—for allegedly heading a nationwide conspiracy to illegally distribute a Fentanyl spray originally intended for cancer patients.[51] The charges against Mr. Kapoor include conspiracy under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (“RICO”), as well as conspiracy to violate the AKS and to defraud health insurance providers who initially were hesitant about approving the spray for non-cancer patients.[52] Superseding indictments also leveled charges against numerous other executives of the company, which itself faced DOJ enforcement actions for allegedly deceptive marketing practices earlier this year.[53] Although the final details of the company’s earlier settlement are not yet available, Insys has announced that it expects to face a nearly $150 million liability and pay out any settlement over the course of five years.[54]

C. Notable Developments in FDCA Enforcement

Several resolutions discussed above also involved FDCA-focused theories. Novo Nordisk, for example, resolved alleged FDCA violations from 2010 to 2012 regarding its purported failure to comply with its required REMS.[55] Specifically, the government alleged that the company obscured the REMS-required message about a risk of taking Novo Nordisk’s Type II diabetes drug Victoza for patients with a rare form of cancer known as Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma, thus rendering the drug “misbranded” under the FDCA.[56] According to the complaint, Novo Nordisk instructed its sales force to provide statements to doctors that downplayed the potential risk rather than increasing awareness about it. As part of the agreement, Novo Nordisk agreed to disgorge roughly $12.2 million for the alleged FDCA violations.[57]

DOJ likewise resolved several misbranding allegations against Aegerion Pharmaceuticals Inc.[58] Roughly one-fifth of the company’s overall $35 million settlement stemmed from allegations that Aegerion failed to provide complete and accurate information to health care providers regarding how Juxtapid—a drug approved to treat patients with a rare cholesterol-related condition—also may cause liver toxicity.[59] The complaint further alleged that Aegerion violated the FDCA by distributing Juxtapid as a treatment for high cholesterol generally without providing adequate instructions for such use.[60]

Apart from the FDCA settlements discussed above, DOJ also obtained several injunctions in the last six months against pharmaceutical manufacturers and distributors to prevent the distribution of allegedly unapproved and misbranded drugs. In September, for example, DOJ announced that the U.S. District Court for the District of New Jersey entered a consent decree and permanent injunction against Flawless Beauty LLC, RDG Imports LLC, and two related individuals.[61] DOJ alleged that the products distributed by the defendants were misbranded because they had been marketed with false and misleading claims, including that the products “contribute to good liver function” and “clinically treat degenerative brain and liver diseases[.]”[62]

DOJ also secured permanent injunctions in October against Philips North America LLC and two executives of the company preventing Philips from distributing certain of its external defibrillators until the company takes remedial steps to comply with deficiencies discovered by FDA inspectors at one of its facilities in 2015, including the company’s purported failure to establish procedures for implementing corrective and preventive actions following customer complaints.[63]

D. FCPA Investigations

As we discussed in our 2016 Year-End Update, last year ended with the largest-ever FCPA payment by a pharmaceutical company (specifically, the U.S. government’s $519 million resolution with Teva Pharmaceuticals Industries Ltd.). By comparison, the last six months of FCPA enforcement have not seen any resolutions involving drug and device makers. Although DOJ and SEC investigations into the foreign sales practices of many drug and device companies (e.g., Alexion Pharmaceuticals Inc.) remain ongoing,[64] DOJ and SEC did not announce any major FCPA settlements with pharmaceutical and medical device manufacturers in the latter half of the year.

Despite the recent dearth of settlements in this space, companies would do well to remain cautious. As suggested in a July 25, 2017 speech by Sandra Moser, Principal Deputy Chief of DOJ’s Fraud Section, DOJ plans to ramp up its enforcement of the FCPA in the health care arena,[65] and FCPA prosecutors will partner with prosecutors from the Healthcare Fraud Unit’s Corporate Strike Force to scrutinize health care company practices abroad.[66]

II. PROMOTIONAL ISSUES

Continuing the trend noted in our Mid-Year Update, 2017 was relatively quiet regarding the regulation of promotion of drugs and devices as compared to prior years. And, once again, the year came and went with minimal progress in FDA’s long-awaited overhaul of its regulatory policies regarding truthful and non-misleading promotional speech. Indeed, in January 2018, FDA announced yet again that it is delaying its controversial proposed rule that would allow the agency to consider the “totality of the evidence” when evaluating intended use under the FDCA. But a number of other regulatory and enforcement developments in the latter half of 2017 show that promotional issues continue to receive a lot of government attention, even if they may not be as top-of-mind as they were in earlier years. Below, we discuss the regulatory enforcement and guidance, jurisprudence, and legislative action concerning promotion of drugs and devices during the last six months of 2017.

As discussed below, FDA’s enforcement and regulatory activity over the past six months focused largely on addressing misleading or deceptive advertisements, which FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb identified as a priority for the agency in remarks in December in connection with the issuance of the promotional guidance discussed below. Commissioner Gottlieb’s remarks recognized that “[p]romotional material that drug makers share with patients and providers can be a helpful tool for encouraging patients to seek medical care and raising awareness about new and different treatment options.”[67] At the same time, he cautioned that a key aspect of FDA’s oversight lies in combatting “claims in prescription drug promotion that have the potential to deceive or mislead consumers and healthcare professionals.” Calling FDA’s efforts “part of an ongoing policymaking process aimed at making sure our practices protect consumers[,]” Commissioner Gottlieb recognized the need for “clear rules for how sponsors can present certain information, even elements as straightforward as the product name, and do so without introducing features that could mislead patients.”[68] How the agency sharpens its focus on misleading or deceptive promotional practices, particularly against the backdrop of the new Administration’s general deregulatory posture, surely will be a key issue to watch in 2018.

A. FDA Enforcement Activity—Advertising and Promotion

The latter half of the year saw a slight uptick in FDA’s enforcement activity in this area, with the Office of Prescription Drug Promotion (“OPDP”) issuing three Warning Letters, up from the one letter issued during the first half of the year.[69] The year’s grand total of just four letters represents a notable decrease in enforcement activity as compared to the eleven letters issued in 2016 and the nine letters issued in 2015. As FDA’s agenda and priorities under the new Administration continue to take shape into 2018, they will continue to shed light on whether this decline in enforcement activity is a temporary artifact of the agency’s leadership transition, or represents the new normal.

Each of the three Warning Letters issued during the past six months concerned the misleading omission of risk information in a drug’s promotional materials, which has been the focus of a majority of letters issued by OPDP in the past few years, as well as failure to include information concerning limitations on use contained in the FDA-approved indication for the product. In contrast to OPDP’s prior focus on electronic advertising, the letters issued in the past six months pertained largely to product information contained in print materials directed at medical professionals, such as professional detail aids and exhibits at annual medical conferences.

- In an August 24, 2017 Warning Letter to Cipher Pharmaceuticals Inc., OPDP asserted that the company’s professional detail aid for a prescription opioid medication made false or misleading representations because it advertised the drug’s efficacy for pain relief without referencing any of the risks associated with the product, including the heightened risk of addiction, abuse, and misuse.[70] OPDP further contended that the detail aid omitted material facts by failing to include the portion of the FDA-approved indication limiting the drug’s intended use solely to instances where alternative treatment options are inadequate.[71]

- In a November 14, 2017 Warning Letter addressed to both Amherst Pharmaceuticals, LLC and Magna Pharmaceuticals, Inc., OPDP raised similar objections with respect to the presentation of a prescription sleep aid on Amherst’s company website and on Magna’s exhibit panels at an annual conference on sleep medicine.[72] According to OPDP, the materials contained false or misleading representations because they made claims about the drug’s efficacy while omitting any risk information.[73] Additionally, OPDP concluded that the materials were false or misleading because they failed to cite references or data to support claims of efficacy and omitted material information regarding the FDA-approved indication for use.[74]

- Finally, in a December 19, 2017 Warning Letter to Avanthi, Inc., OPDP asserted that the company presented false or misleading information in an exhibit for a weight loss medication displayed at two annual medical conferences.[75] As with the two letters issued earlier in the year, OPDP asserted that the promotional materials were misleading by making claims about the benefits of the product without communicating any information about the drug’s risks and omitting the limitations on use in the FDA-approved product indication.[76]

B. FDA’s Promotional Guidance

FDA did not deliver in 2017 on its promise to provide new promotional guidance for the industry regarding off-label promotion of drugs and devices, which FDA first pledged to issue more than three years ago as part of a comprehensive review of its policies in the face of rising First Amendment concerns. Apart from the January 2017 memorandum in which FDA identified and rejected 12 alternative approaches to off-label promotion under the First Amendment, and the related commentary period discussed in our Mid-Year Update, the year saw no further public progress towards FDA’s announced goal. We will continue to monitor FDA’s progress in the upcoming year.

As 2017 came to a close, FDA issued one final guidance document on promotional issues—part of what Commissioner Gottlieb described at the time as FDA’s “ongoing” efforts to protect consumers against deceptive or misleading prescription drug advertising claims by setting “clear rules for how sponsors can present” such information in a non-misleading manner, as noted above.[77]

Issued on December 11, 2017, FDA’s guidance clarifies the requirements for product name placement, size, prominence, and frequency in promotional labeling and advertising for prescription drugs, including biological drug products.[78] The new guidance focuses specifically on the juxtaposition of the proprietary and established names of a drug and the frequency with which to use the established name on promotional materials. The guidance applies to promotional labeling and advertisements across a range of media, including print, audiovisual, broadcasting, and electronic and computer-based materials.[79]

- With respect to drugs containing one active ingredient, the guidance provides specific recommendations for complying with the various requirements set forth in regulations 21 C.F.R. §§ 201.10(g)(1) and (2), and 202.1(b)(1) and (2), concerning the appropriate juxtaposition of proprietary and established names, the size of proprietary and established names on labeling and advertisements, the prominence of the established name in relation to the proprietary name, and frequency of disclosure of the proprietary and established names using various media. With respect the last category, the guidance identifies examples in which FDA “does not intend to object” to fewer references to the established name, so long as certain criteria are met.[80]

- With respect to drugs containing two or more active ingredients, the guidance provides recommendations of how to appropriately reference proprietary and established names as set forth in regulations 21 C.F.R. §§ 201.10(h)(1) and 202.1(c) and (d)(1), in situations where a product “might not have a single established name corresponding to the proprietary name” or in which “a proprietary name might refer to a combination of active ingredients present in more than one preparation (e.g., individual preparations differing from each other as to quantities of active ingredients and/or the form of the finished preparation), and there might not be an established name corresponding to the proprietary name.”[81]

As we noted in our 2017 Mid-Year Update, in January 2017, as part of the Obama Administration’s last-minute efforts to shape FDA promotional policies, FDA issued two draft guidance documents relating to promotional practices, the first being a “Questions and Answers” guidance entitled “Medical Product Communications That Are Consistent with the FDA-Required Labeling,”[82] and the second draft guidance document addressing communication of health care economic information to payors about both approved and investigational drugs and devices.[83] As of the end of 2017, FDA has not taken further action with respect to these guidance documents, both of which remain in draft form.

Finally, on January 12, 2018, FDA announced that it was yet again delaying—this time, “until further notice”—the effective date of a controversial final rule that would amend the agency’s definition of “intended use” for drugs and devices to allow the agency “additional time” for further consideration of the rule.[84] The final rule, issued in January 2017, shortly prior to the change of administration, would adopt a “totality of the evidence” standard for assessing how a manufacturer intended for its product to be used by doctors and patients, carrying significant implications for drug and device manufacturers regarding promotional activities and related enforcement of the FDCA and its implementing regulations. The proposed rule has been met with heavy criticism from the industry, including that it imposes an unworkably vague standard—a concern Commissioner Gottlieb expressly recognized in a statement issued in connection with the delay, in which he conceded that the regulation “wasn’t clear” and pledged that the agency would “ensure the clarity of our rules on the subject.”[85] In the meantime, he noted, FDA was “reverting to the agency’s existing and longstanding regulations and interpretations on determining intended use for medical products.”[86] FDA has opened a comment period through February 5, 2018, to solicit input on the decision to indefinitely delay the rule.[87]

We will report on further developments in the coming year in regards to whether FDA modifies the final rule or permanently abandons its efforts to redefine the intended use standard.

C. Notable Litigation Pertaining to Promotional Issues

Although 2017 saw little in the way of jurisprudence concerning the intersection of promotional issues and the First Amendment, it produced several other notable cases.

Opinions dismissing FCA actions predicated on off-label promotion from the Fifth Circuit in United States ex rel King v. Solvay Pharm., Inc.,[88] and Sixth Circuit in United States ex rel. Ibanez v. Bristol-Myers Squibb Co.,[89] discussed in detail above, underscored the importance of and difficultly involved in pleading and proving the causal chain in such cases. The complex series of events involved create significant hurdles to pleading and proving that it was the defendant’s alleged off-label promotion that actually caused the submission of any false claims—i.e., that a physician to whom a product was allegedly improperly promoted prescribed the medication to a patient for an off-label use because of that promotion, resulting in the patient filling the prescription at a pharmacy, and the filling pharmacy then submitting a claim to the government for reimbursement. Although these judicial opinions do not entirely foreclose any theory of FCA liability predicated on off-label promotion, they provide a useful tool for drug and device manufacturer defendants to assert lack of causation arguments.

Based on similar causation principles, the Seventh Circuit held, in Sidney Hillman Health Ctr. of Rochester v. Abbott Labs., that as a matter of law third-party payors may not recover treble damages under RICO’s civil liability provision based on a manufacturer’s allegedly unlawful off-label representations made to physicians.[90] There, two welfare benefit plans that paid for some off-label drug uses brought a suit seeking civil RICO recovery against the manufacturer following its 2012 guilty plea and payments to settle a criminal investigation and qui tam actions. Joining the majority of circuit courts to have addressed the issue, the Seventh Circuit held that the causal chain involved in such a claim was “too long” and too rife with “independent decisions” to pass muster under Supreme Court precedent,[91] because it would require showing that physicians who received the off-label communications changed the medication they would have otherwise prescribed to certain patients as a result of the communications, that some of those patients were worse off as opposed to better, that payors bore some of the cost, and that those payors were made worse off to the extent the drug at issue was more expensive than the alternative drug.[92]

D. Legislative Developments

On the whole, 2017 saw relatively little legislative activity relating to off-label promotion at the state or federal levels.

For its part, Congress took no further action on two draft bills on which we reported in our 2017 Mid-Year Update: (1) the Pharmaceutical Information Exchange Act, which would give drug and device manufacturers’ greater freedom to share economic information about expected cost-effectiveness with insurers prior to FDA approval of a product;[93] and (2) the Medical Product Communications Act of 2017, which would enable manufacturers to proactively discuss certain off-label information with health care provider, so long as the information is supported by competent and reliable scientific evidence and accompanied by various disclaimers.[94]

The House Energy & Commerce Committee held hearings on both bills in July, at which time some lawmakers and industry groups expressed support for the proposed clarification concerning off-label communications and for providing for more information to payers and health-care decision makers aimed at improving patient access to new treatments.[95] Other lawmakers and industry groups, however, expressed concern that the bills, and the Medical Product Communications Act in particular, would undermine efforts to prevent marketing of unsafe or ineffective medical products and could ultimately put patient health and safety at risk.[96] To date, neither bill has advanced out of committee.

At the state level, as we reported in our Mid-Year Update, Arizona became the first state to allow drug and device manufacturers to communicate directly with physicians and insurers about off-label uses of FDA-approved prescription drugs. Although Arizona remains alone for the time being, that may change in the coming year as industry advocates continue to pursue the introduction of similar measures in other state legislatures.[97]

E. Settlements

One notable recent settlement this year also demonstrated the states’ interest and capacity for enforcement actions targeting off-label promotion as misleading or deceptive advertising under state law. On December 20, 2017, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. agreed to pay $13.5 million to all 50 states and the District of Columbia to resolve claims asserted under various state consumer protection laws predicated on its alleged off-label marketing and certain allegedly misleading representations it made in promoting the drugs at issue.[98] Several years earlier BIPI resolved claims under the federal FCA based on the same alleged off-label marketing and alleged misrepresentations in a $93 million settlement with the federal government.[99]

III. DEVELOPMENTS IN CGMP REGULATIONS AND OTHER MANUFACTURING ISSUES

In 2017, FDA continued the robust scrutiny of drug companies’ current good manufacturing practice (“cGMP”) compliance that we have come to expect in recent years. These developments, which include relevant enforcement actions and new draft guidance, are discussed below.

A. Notable cGMP Compliance and Enforcement Activity

1. Executive of Pharmaceutical Company Pleads Guilty

In June 2017, the owner/president, Paul Elmer, and compliance director, Caprice Bearden, of Indiana pharmacy Pharmakon Pharmaceuticals, Inc., were indicted for allegedly introducing adulterated drugs into interstate commerce by manufacturing and selling drugs whose potency differed than what was reflected on the label.[100] According to DOJ, the officers’ actions resulted in several infants being given morphine sulfate that was nearly 25 times more potent than indicated, leading to severe health problems for at least one of the infants. Although both initially pled not guilty, in November 2017, Bearden pled guilty to introducing adulterated drugs into interstate commerce and conspiracy to defraud the United States by obstructing FDA’s lawful functions.[101] Commissioner Gottlieb called the case “an egregious example of how harmful conduct can result in risk to patients” and added that FDA “will not tolerate substandard practices, like failing to meet federal manufacturing standards like those found at Pharmakon” relating to out-of-specification drug potency test results, “that put patients at risk and will aggressively pursue individuals that put profit ahead of patient safety.”[102]

2. Consent Decrees Involving Two Drug Manufacturers, One Device Manufacturer

During the last six months, DOJ announced three notable consent decrees of permanent injunction entered by federal district courts against manufacturers to stop the distribution of unapproved, misbranded, and adulterated drugs and devices. On July 5, 2017, the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Alabama enjoined Medistat RX LLC, its owners, production manager, and quality manager from manufacturing, holding or distributing drugs until they comply with the FDCA and its regulations.[103] The government alleged that the defendants failed to comply with cGMP because, after identifying a microbial contamination, they failed to adequately investigate or take sufficient corrective action, resulting in the contamination of certain sterile areas within the facility.

On August 3, the U.S. District Court for the District of Utah entered a consent decree including a permanent injunction against Isomeric Pharmacy Solutions, LLC and three affiliated individuals, including the Chief Operating Officer.[104] FDA accused the defendants of distributing drugs that had visible “black particles” in them, despite passing visual inspections conducted by the defendants’ employees. The complaint alleged that the defendants’ manufacturing methods did not conform to cGMP because they failed to verify the drug products’ safety, identity, strength, and quality and purity characteristics, as required by the FDCA. FDA also alleged that the company had a history of manufacturing drug products under suboptimal conditions and demonstrated an unwillingness or inability to take corrective actions to ensure the sterility of its products. Consequently, the consent decree prohibits Isomeric from distributing drug products until they hire a consultant who makes a determination that the company is in compliance with cGMP requirements.

Lastly, on October 31, the U.S. District Court for the District of Massachusetts enjoined Philips North America LLC and two of its executives from distributing certain medical devices until remedial steps are taken to bring the company in compliance with cGMP.[105] FDA alleged that the company failed to establish and maintain adequate procedures for implementing corrective and preventative action in response to complaints about the performance of a certain defibrillator and cardiopulmonary resuscitation device. The consent decree requires Philips to institute a number of remedial measures, including hiring an expert consultant to inspect its units and ensure that the devices are complying with cGMP regulations.

3. cGMP-Based Warning Letters

FDA’s Office of Manufacturing Quality in the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (“CDER”) issued 22 warning letters in the second half of 2017 for a total of 48 letters for the year, exceeding the 44 letters it issued in 2016.[106] In the latter half of this year, FDA focused primarily on companies’ failure to maintain adequate quality control units, incomplete testing procedures, subpar sterilization and sanitation techniques, and inadequate testing procedures.

Consistent with prior years, FDA has continued its foreign-inspection activity, issuing warning letters to companies in Korea, Canada, China, India, Philippines, and Italy. Notably, only one of the letters FDA issued in 2017 was to a U.S.-based company.[107] Several of the more notable warning letters from the second half of the year are summarized below.

One of the more common complaints by FDA in the latter half of this year was companies’ failure to maintain adequate quality control units:

- In October, Chinese drugmaker Guangdong Zhanjiang Jimin Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., received a warning letter stating that it had failed to establish an adequate quality control unit and consequently used the wrong active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) in one of its products.[108] Although the company recalled all of the product distributed in the U.S., it failed to document its investigation into the mistake or a plan to prevent its recurrence, nor did it have a program in place to monitor process controls. As such, FDA strongly recommended that the company engage a consultant to assist with cGMP requirements.

- In December, FDA issued a warning letter to South Korean drug-maker Seindni Co. Ltd. for failing to establish a quality control unit that could oversee packaging, labeling, and other elements of drug production.[109] Notably, FDA stressed the particular importance of such a unit in light of the company’s use of contract manufacturers to manufacture its over-the-counter (OTC) drug products. FDA ordered Seindni to provide written procedures establishing an adequate quality control unit with the authority to carry out various responsibilities, including batch review and release processes and supplier and contractor qualification, selection, and oversight.

Many of FDA’s warning letters this year focused on companies’ failure to adequately test and verify the identity of each component of their drug products.

- In August, FDA issued a warning letter to Canadian homeopathic manufacturer Homeolab USA Inc. in connection with toddler teething tablets that contained belladonna, a toxic substance also known as deadly nightshade.[110] The letter alleged numerous cGMP violations, including the company’s failure to perform adequate testing for the purity, strength, and quality of components used in its manufacturing process. It also stated that, during FDA’s inspection of the company’s facilities, a Homeolab employee “impeded the inspection by preventing [the] investigator from photographing” a piece of equipment. FDA recommended that Homeolab hire a cGMP consultant to assist the company in meeting cGMP regulations.

- South Korean drug-maker Dasan E&T Co. Ltd. received a warning letter in September for failing to analyze glycerin raw material from a supplier prior to approving the material for use in its drug products.[111] Specifically, it alleged that Dasan failed to screen for the presence of diethylene glycol (DEG), a chemical found in antifreeze that “has resulted in various lethal poisoning incidents in humans worldwide.” FDA directed Dasan to develop a detailed risk assessment regarding glycerin-containing products.

- More recently, in November, Dae Young Foods Company, a Korean manufacturer of homeopathic smoking cessation gum and lozenges, received a warning letter alleging that the company failed to test drug components for identity, purity, strength, and quality.[112] It also alleged that the suppliers Dae Young used were not properly vetted. FDA ordered the company to provide a scientific justification for how it will ensure that all of its components will meet appropriate specifications before use in manufacturing, as well as a risk assessment for any drug product batches that were not already adequately tested.

FDA also issued numerous letters identifying issues relating to the sanitization and/or sterilization of equipment and utensils involved in the manufacturing of drug products:

- In July 2017, FDA asserted that India-based Vista Pharmaceuticals violated cGMP by, among other things, failing to maintain several pieces of manufacturing equipment, which were observed to have “holes and corrosion.”[113] The letter noted that FDA had received a claim that metal was found in one of its isoxsuprine hydrochloride tablets and, during a subsequent inspection, FDA was told that the company’s employee who investigated the claim “failed to consider whether the poor condition of [the] equipment may have contributed to the problem.” Consequently, FDA directed the company to submit an evaluation of all production equipment to ensure that it is in appropriate condition for manufacturing.

- Similarly, on December 18, FDA sent a warning letter to Deserving Health International, a Canadian homeopathic drug manufacturer, stating that the company failed to implement an appropriate manufacturing process that could ensure the sterility of its Symbio Muc Eye Drops 5X, an ophthalmic product.[114] Specifically, the letter claimed that the method used “to attempt sterilization” was not suitable for its intended use, and that the product was manufactured using “unsuitable water.” The letter noted that FDA placed Deserving Health International on Import Alert on November 2 of this year and recommended that the company employ a cGMP consultant to assist in undertaking a “comprehensive assessment” of the company’s manufacturing operations to ensure compliance with cGMP regulations.

B. cGMP Rulemaking and Guidance Activity

1. FDA Draft Guidance

While FDA has continued to be quite active in enforcement of manufacturing standards, since June, it has issued just one final guidance document pertaining to manufacturing and quality issues.

Expiration Dating. On August 8, 2017, FDA issued revised draft guidance addressing the repackaging of prescription and OTC solid oral dosage form drugs into individual unit-dose containers by commercial pharmaceutical repackaging firms.[115] Under current FDA cGMP regulations, each drug product must have an expiration date determined by appropriate stability testing relating to storage conditions on the label, as determined by stability studies. As the guidance observes, the increase in unit-dose repackaging over the last few decades has raised questions about the stability and expiration dates for such repackaged products. Consequently, the latest draft guidance amends an earlier draft guidance published in 2005 to accomplish a number of objectives: “shorten[ing] the expiration date to be used under certain conditions for solid oral dosage forms repackaged in unit-dose containers”; “provid[ing] an expiration date exceeding 6 months if supportive data from appropriate studies are available and other conditions are met”; “exclud[ing] from the scope of the guidance products repackaged by State-licensed pharmacies, Federal facilities, and outsourcing facilities”; “exclud[ing] from the scope of the guidance all dosage forms other than solid oral dosage forms”; and “provid[ing] for the use of containers meeting USP [] Class B standards if certain conditions are met.”[116]

IV. ANTI-KICKBACK STATUTE

As the enforcement statistics discussed above make clear, compliance with the AKS remains one of the highest risk areas for pharmaceutical and medical device companies, with notable large settlements in AKS being announced virtually every year, including in 2017. There were several notable developments in AKS enforcement during the second-half of 2017—from the courts and regulatory agencies—that affect and define the stakes.

A. AKS-Related Case Law

First, federal courts issued several noteworthy decisions interpreting the AKS during the second half of 2017 on the topics of causation and scienter.

In September, the Fifth Circuit affirmed summary judgment for Solvay Pharmaceuticals, dismissing allegations that the company violated the FCA through off-label marketing efforts (as discussed above) and kickbacks to physicians.[117] In addition to the Fifth Circuit’s rulings regarding off-label promotion theories, the Fifth Circuit also summarily dismissed the relator’s AKS allegations after finding no credible evidence on summary judgment that payments to physician-consultants caused those physicians to write prescriptions that were reimbursed by Medicaid.[118] Evidence submitted to the court showed that physicians participated in Solvay speaker programs in which they were compensated for consultations or presentations.[119] The court explained that “[t]here was nothing illegal about paying physicians for their participation in these types of [marketing] programs and there is no evidence that participation was conditioned upon prescribing Solvay’s drugs to Medicaid patients.”[120] Although the court acknowledged that Solvay likely “intended these programs to boost prescriptions”―as is true with most marketing practices, of course―the court nonetheless held that “it would be speculation to infer that compensation for professional services legally rendered actually caused the physicians to prescribe Solvay’s drugs to Medicaid patients.”[121] This is clearly at odds with DOJ’s persistent position that the payment of a kickback “taints” physician decision-making and that allegations of improper payments do not need to show that prescriptions or referrals were “caused” by the kickback. For example, in 2015, DOJ reached a settlement with Novartis based on allegations that the company made payments to influence specialty pharmacies to provide patients one-sided advice about their product, without disclosing potentially serious side effects. Then U.S. Attorney for Manhattan stated that that the AKS “was enacted to ensure that the medical treatment and advice patients receive, and federal programs pay for, are free from the taint of corporate kickbacks.”[122] We will continue monitoring this development to see if courts continue to require a showing of cause, not mere “taint,” and DOJ’s response.

In United States v. Nerey, meanwhile, the Eleventh Circuit reached a less favorable conclusion for the defendant in an alleged kickback scheme, holding that the government had sufficiently proved willful conduct in connection with a federal health care program because of the defendant’s attempts to hide illegal kickbacks.[123] In so holding, the court reaffirmed that proving “willful conduct” under the AKS requires strong evidence of scienter, requiring that the act was “committed voluntarily and purposely, with the specific intent to do something the law forbids, that is with a bad purpose, either to disobey or disregard the law.”[124] But the court had no problem finding willful conduct in light of the “overwhelming” evidence that the defendant explicitly sought cash payments to avoid a paper trail, attempted to funnel kickbacks by masking them as therapy services, referred to kickbacks by code names because of their illegal nature, pre-arranged a fallback story in the event of a Medicare audit, and was caught saying that it would be nice to “break [a suspected confidential informant’s] head.”[125]

B. Guidance and Regulations

1. HHS OIG Increases Scrutiny of Patient Assistance Programs

For years, pharmaceutical and device manufacturers have supported, directly and indirectly, various patient assistance programs that help needy patients access their products. And for years, OIG has approved of these arrangements, subject to certain recommended contours, through formal and informal guidance reflecting that these programs meet important access-to-care goals.

Recently, however, OIG has issued updated guidance to refine its views on patient assistance programs and strongly suggest that it is taking a closer look at how these programs are organized and operated. While the OIG formerly viewed these programs as important safety nets for patients who face chronic illnesses and high drug costs, newer guidance suggests that OIG is concerned that patient assistance programs that are limited to specific diseases or products—often with the support of pharmaceutical and medical device companies—pose a high risk of abuse. That trend continued in 2017 amidst a broader landscape of DOJ enforcement actions, as discussed in Section I above.

First, in March, HHS OIG revised previous guidance to address aspects of patient assistance programs that it has newly determined are “problematic.”[126] Specifically, HHS OIG modified a prior advisory opinion to require that a non-profit operator of patient assistance programs make three new certifications to remain in compliance with the AKS: (1) that the charity “will not define its disease funds by reference to specific symptoms, severity of symptoms, method of administration of drugs, stages of a particular disease, type of drug treatment, or any other way of narrowing the definition of widely recognized disease states”; (2) that the charity will “not maintain any disease fund that provides copayment assistance for only one drug or therapeutic device, or only the drugs or therapeutic devices made or marketed by one manufacturer or its affiliates”; and (3) that the charity will not limit its assistance to high-cost or specialty drugs.[127]

Next, in November, HHS OIG took the unprecedented step of rescinding guidance it had previously issued related to a patient assistance program operated by the industry-funded charity Caring Voice Coalition (CVC).[128] HHS OIG explained that the charity had allegedly breached two commitments related to independence from donors, which opened the door to steering Medicare beneficiaries toward specific prescription drugs.[129] In one alleged breach, the charity gave patient-specific data to one or more donors, enabling them to “correlate the amount and frequency of their donations with the number of subsidized prescriptions or orders for their products.”[130] In a second alleged breach, the charity “allowed donors to directly or indirectly influence the identification or delineation of [r]equestor’s disease categories.”[131] According to HHS OIG, these violations “materially increased the risk that [r]equestor served as a conduit for financial assistance from a pharmaceutical manufacturer donor to a patient, and thus increased the risk that the patients who sought assistance from [r]equestor would be steered to federally reimbursable drugs that the manufacturer donor sold.”[132] HHS OIG expressed concern that this steering can provide manufacturers with a greater ability to raise the prices of their drugs while protecting patients from the effects of the price increases, leaving federal programs and taxpayers to bear the cost.[133]

HHS OIG and DOJ are clearly taking a hard look at these types of issues industry-wide, and the results of this scrutiny are beginning to show in more than just HHS OIG advisory opinions. For example, as noted above, United Therapeutics Corp. paid $210 million to resolve allegations that it used a nonprofit organization as a conduit to give improper benefits to thousands of patients who used its medications from 2010 to 2014.[134] Specifically, the government alleged that United Therapeutics donated money to CVC, which in turn paid the copay obligations of thousands of Medicare patients taking drugs manufactured by the company.[135] Several other companies have reported being subject to similar probes in the past year, all launched by the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Massachusetts.[136]

Yet, even as DOJ and HHS OIG seek to reign in alleged abuses in patient assistance programs, HHS OIG, at least, has nevertheless continued to encourage manufacturers to provide access to free drugs for needy patients. After its unprecedented action against CVC, which led CVC to announce it would not offer any financial assistance in 2018, HHS OIG wrote immediately to Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (“PhRMA”) to urge pharmaceutical companies to offer free drugs to former CVC beneficiaries.[137] To incentivize companies to participate in this stop-gap measure, HHS OIG promised that it “will not pursue administrative sanctions against any Drug Company for providing free drugs during 2018 to federal health care program beneficiaries who were receiving cost sharing support for those drugs from CVC as of November 28, 2017,” provided certain conditions are met, including that: (1) the “drugs are provided in a uniform and consistent manner to Federal health program beneficiaries” who were receiving drugs from CVC at the time of CVC’s decision; (2) “[t]he free drugs are awarded without regard to the beneficiary’s choice of provider, practitioner, supplier or health plan[;]” (3) “[t]he free drugs are not billed to any Federal health care program” or a third party payor; (4) “[t]he provision of free drugs is not contingent on future purchases” of drugs; and (5) the Drug Company maintains complete and accurate records of the free drugs provided to Federal health care program beneficiaries.[138] Even with this significant policy statement early in the year, there may well be additional fallout for manufacturers’ charitable programs in 2018, given the government’s clear enforcement focus on this area.

2. HHS OIG clarifies scope of warranty safe harbor

The AKS makes it a criminal offense to knowingly and willfully exchange anything of value in an effort to induce the referral of services which are payable by a federal program, but the statute and its implementing regulations also create certain safe-harbors against liability.[139] For example, the “warranty safe harbor” shields from penalty certain written warranties offered by drug and device companies, including (1) a written affirmation that relates to the nature of the material or workmanship of a product and that affirms or promises that the material or workmanship is defect-free or will meet a specified level of performance over a specified period of time; or (2) any undertaking in writing by a supplier to take remedial action if a product fails to meet the promises set forth by the supplier of a consumer product.[140] Previous HHS OIG guidance had limited the scope of the warranty safe harbor to product failure.[141]

In a new advisory opinion issued in August, however, HHS OIG seemingly expanded the scope of the warranty safe harbor. Specifically, HHS OIG considered a “pharmaceutical manufacturer’s proposal to replace products that require specialized handling that could not be administered to patients for certain reasons, at no additional charge to the purchaser[.]”[142] According to the opinion, the requestor sells a variety of products, some of which “are sensitive to temperature changes, direct sunlight, or movement[.]”[143] Under the arrangement, the pharmaceutical manufacturer would replace products that had spoiled or otherwise become unusable after purchase so long as the customer had not administered the product or billed for it.[144]

HHS OIG analyzed the proposal under the safe harbor for warranties, which it explained “protects remedial actions by suppliers to address products that fail to meet bargained-for requirements.”[145] Although HHS OIG concluded that the proposal did not fall squarely within either of the safe harbor’s definitions, it nonetheless concluded that the proposed arrangement posed a “low risk of fraud and abuse under the [AKS].”[146] HHS OIG reached this conclusion for a number of reasons. First, the replacement would be restricted to unintentional circumstances. Second, there was low risk that this arrangement would lead to increased cost or overutilization because, if the customer administered the product or billed for the product, then a replacement product would not be available. Third, even though the proposed arrangement could affect competition, there was an acceptably low risk that a customer would choose products based on this arrangement. Last, the proposed arrangement bears some similarity to an insurance policy and the cost of this can be built into the cost of the product.[147] HHS OIG also noted that the proposal could increase patient safety and care.[148]

This guidance expands the number of warranty types for which the OIG has recognized the availability of the warranty safe harbor, thereby affording manufacturers greater flexibility to tie product pricing to performance, further incentivizing providers to deal with product sellers and manufacturers who are willing to stand behind the performance of their products by sharing the risk on outcomes.

3. HHS OIG permits pilot program to provide Medicare Advantage pharmacists with real-time access to patient discharge information

In December, HHS OIG approved a proposal to allow a vendor to develop and make available an interface that would allow pharmacists to view relevant clinical data in real-time during discharge for Medicare Advantage plan beneficiaries who were admitted with one of five eligible diagnoses.[149] The pilot program aims to “gain insight into the degree to which technology that provides . . . pharmacists with real-time access to discharge information can help improve transitions of care and decrease re-hospitalizations.”[150]

HHS expressed concern that the interface would have an independent value, and therefore be an improper remuneration, because it would remove an administrative burden and that pharmacists would be in a position to influence which medications a patient is prescribed.[151] Ultimately, HHS OIG concluded that it would not impose sanctions under the AKS. Importantly, the manufacturer protected against the risk that the pharmacist would recommend the manufacturer’s product by including language in the agreements and operative documents that the collaboration would have no bearing on formulary recommendations or referrals of business, and ensuring that nothing in the interface would guide the pharmacist to choose one product over another.[152] HHS OIG also focused on patient care and patient outcomes. OIG concluded that the proposed arrangement would be unlikely to lead to increased costs or overutilization of federally reimbursable services because the Medicare Advantage plan, “as the payor, has a strong incentive for its members to receive the most appropriate and cost-effective treatment to promote their recovery and good health.”[153] Further, the proposal would be unlikely to have a negative outcome on patient quality of care.[154] And lastly, HHS OIG concluded that the small scale of the program—limited to approximately 200 patients and five diagnoses—reduces the risk that the remuneration involved would influence referrals to or recommendations for the manufacturer’s products.[155]

V. MEDICAL DEVICES

After a relatively quiet start to the year, the second half of 2017 brought a number of guidance documents and enforcement actions concerning medical device manufacturers. We begin this section with an overview of notable guidance issued by FDA before walking through recent device-related enforcement activity.

A. FDA Guidance

In the past six months, FDA issued guidance on several noteworthy subjects, including digital health, pre-market approval standards, and expedited approval processes. As continued technological advances continue to pave the way for new clinical opportunities, FDA has emphasized its focus on streamlining the review process and providing access to newly vetted medical devices.

In addition to the topics discussed in detail below, President Trump in August 2017 signed into law the FDA Reauthorization Act (“FDARA”), which, among other things, reauthorizes the Medical Device User Fee Amendments through fiscal year 2022.[156] With the return of the Affordable Care Act’s medical device tax on the horizon in 2018, a new user fee will be assessed under FDARA for de novo classification requests, and user fees will be adjusted annually for inflation.[157] FDARA also sets forth a risk-based inspection schedule for establishments engaged in the manufacture, propagation, compounding, or processing of devices and requires FDA to establish uniform inspection processes and standards.[158] Be on the lookout in the coming year for possible inspection-related draft guidance.[159]

1. Digital Health

On July 27, 2017, FDA took a step into a new digital-health era with the announcement of its Digital Health Innovation Action Plan and the launch of its “Pre-Cert for Software Pilot Program.”[160] Framed as FDA’s response to the “revolution in health care,” driven by technology such as mobile medical apps, fitness trackers, and decision-supporting software, the Action Plan outlines the Center for Devices and Radiological Health’s (“CDRH”) “vision for fostering digital health innovation while continuing to protect and promote the public health.”[161] The plan contemplates providing guidance on the 21st Century Cures legislation’s medical software provisions, as well as launching a pilot pre-certification program that focuses on the developer instead of the product in the hopes of “replac[ing] the need for a premarket submission for certain products,” decreasing the required submission content, and speeding up the review of marketing submissions.[162] FDA plans to share updates about the program at a public workshop in January 2018.[163]

As anticipated by the Action Plan, on December 7, 2017, FDA announced three draft and final guidance documents that further clarify its approach to digital devices:

- Clinical and Patient Decision Support Software. The revised definition of “medical device” in the 21st Century Cures Act excluded certain types of software intended to provide clinical decision support. The first draft guidance describes FDA’s interpretation of this revised definition and generally extends this interpretation to patient decision support software.[164] The guidance states that FDA will continue to regulate clinical decision support (“CDS”) software “intended to acquire, process, or analyze a medical image, a signal from an in vitro diagnostic device, or a pattern or signal from a signal acquisition system,” but it will not regulate software that provides health care professionals with recommendations or treatment decisions that are consistent with the FDA-required labeling or clinical guidelines and that the professionals could have made independently.[165] The critical factor, in FDA’s interpretation, is that the user should be able to reach independently the clinical recommendation provided by the software. Furthermore, the sources for the software recommendation should be publicly available, such as in the published scientific literature. Likewise, with respect to software intended to support patient decision-making, FDA does not intend to focus its regulatory oversight on “low-risk” software that offers patients recommendations they could have reached independently without the software.[166]

- Changes to Medical Software Policies After the Cures Act. In this draft guidance, FDA addressed the software functions that were excluded from the definition of “medical device” by the 21st Century Cures Act: hospital administrative functions, software intended for maintaining or encouraging a healthy lifestyle, electronic health records, and software for transferring, storing, or displaying data [167] As a result of the statutory amendments, certain types of software that were previously under FDA enforcement discretion are no longer classified as “medical devices” under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. The guidance clarifies that Laboratory Information Management Systems are not devices and reiterates that FDA does not intend to examine or regulate “low-risk general wellness products,” such as a mobile application that plays music to relieve stress.[168] In describing its approach to such products, FDA references the General Wellness Guidance detailed in our 2016 Year-End Update[169] and offers examples illustrating when electronic patient record software and Medical Device Data Systems do not qualify as devices.[170] FDA is updating the prior software-specific guidances to reflect the 21st Century Cures Act.

- Clinical Evaluation of Software as a Medical Device (SaMD). On December 8, 2017, FDA issued final guidance on its approach to Software as a Medical Device (“SaMD”), which is software intended to be used for one or more medical purposes that perform these purposes without being part of a hardware medical device.[171] This guidance adopts the principles set forth by the International Medical Device Regulators Forum (“IMDRF”), a group of international medical device regulators focused on harmonization of device regulation. These principles address risk-based analysis and assessments of SaMD and considerations to use in evaluating the safety and effectiveness of SaMD.[172] The guidance discusses the assessment of: (1) the clinical association between the SaMD and the targeted clinical condition; (2) the SaMD’s ability to correctly process data to provide accurate, reliable, and precise output data; and (3) the use of the output data to achieve the intended purpose in clinical care. The guidance explains when independent review of a clinical evaluation of a SaMD may be necessary, offers considerations for continuous learning throughout a SaMD’s lifecycle, and provides a comparison of the SaMD clinical evaluation process to the process for generating clinical evidence for in vitro diagnostic medical devices.[173]

2. “Least Burdensome Approach” Guidance

In keeping with its focus on streamlined review processes, FDA issued new draft guidance on December 15, 2017, detailing updates to the “least burdensome approach” used during premarket review of devices.[174] Commissioner Gottlieb and CDRH Director Dr. Jeffrey Shuren have touted the benefits of the program, emphasizing the ability to devote resources to the “issues of highest public health concern” and to approve greater numbers of medical devices.[175]