July 26, 2018

A year and a half into the new Administration, we are seeing new and shifting enforcement and regulatory trends in the health care provider space. While the staying power of these trends remains uncertain, it is increasingly clear that the Administration is implementing changes—including potentially significant ones—at each of the principal health care enforcement agencies. The first half of 2018 also saw notable case law developments on some of the most hot-button issues facing health care providers, helping to round out an eventful six months across the health care compliance and enforcement landscape. We cover all of these trends and developments in greater depth below.

First, while the U.S. Department of Justice (“DOJ”) and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (“HHS”) stepped up their opioid-related enforcement efforts, other areas of enforcement saw less aggressive pursuit over the past six months compared to the first half of 2017. Notably, DOJ gave several indications of letting up on affirmative enforcement actions, including with the release of then-Associate Attorney General Rachel Brand’s memorandum (the “Brand Memo”), which prohibits DOJ from using guidance documents and sub-regulatory actions to “create binding requirements that do not already exist by statute or regulation.” The Brand Memo and other recent DOJ pronouncements are particularly salient for health care providers, for whom enforcement actions can often be grounded in agency and contractor guidance. That said, if the degree of ongoing criminal and civil enforcement efforts related to opioids is any indication, we anticipate a very busy second half of 2018 for both DOJ and the HHS Office of Inspector General (“HHS OIG”), and the Administration may be poised for a net increase in resolution numbers in the second half of the year and into 2019, notwithstanding the let-up in other areas.

Second, the first six months of 2018 also saw several notable case law developments that could have a lasting impact on health care providers. We report below on courts’ ongoing efforts to make sense of the implied certification basis for False Claims Act (“FCA”) liability recognized by the Supreme Court in Universal Health Services, Inc. v. United States ex rel. Escobar. We also survey key developments regarding FCA liability in cases where a difference of medical opinion underlies providers’ alleged liability, as well as courts’ recent approaches toward statistical sampling to prove liability and damages in FCA cases.

Finally, we discuss recent regulatory and case law developments salient to two of the most important and prevalent issues for health care providers—the Anti-Kickback Statute (“AKS”) and the Stark Law.

As always, a collection of Gibson Dunn’s recent publications and presentations on health care issues impacting providers may be found on our website. And, of course, we would be happy to discuss these developments—and their implications for your business—with you.

I. DOJ Enforcement Activity

A. False Claims Act Enforcement Activity

Between January 1 and June 30, 2018, DOJ announced approximately $201 million in FCA recoveries through settlements with health care providers, significantly below the $817 million figure recovered by DOJ through settlements as of June 30, 2017.[1] This is likely due to the fact that in the first half of 2017, DOJ settled eight cases for more than $30 million (the approximate amount of the single highest settlement in the first half of 2018) including one for $155 million.[2] The total of forty health care provider settlements announced by DOJ during the first half of 2018 is also considerably lower than the fifty-four health care provider settlements announced during the first half of 2017, the forty-nine settlements announced during the first half of 2016, and the fifty-seven settlements announced during the first half of 2015.

Given the long road most FCA matters take to resolution—the average FCA case can take two years or more to investigate before the government decides whether to pursue it—it is hard to tell if the lower number of settlements in the first half of 2018 compared to last year is a result of a change in DOJ policies or priorities. But there is reason to think providers may have success pushing back on aggressive FCA enforcement going forward, if the Brand Memo and related statements by DOJ are any indication.

The January 25, 2018 Brand Memo cabined the ability of prosecutors to use non-compliance with agency guidance as the basis of an FCA claim.[3] Specifically, the Brand Memo prohibits (1) using non-compliance with other agencies’ “guidance documents as a basis for proving violations of applicable law” in affirmative civil enforcement cases, and (2) using an agency’s “enforcement authority to effectively convert agency guidance documents into binding rules.” The Brand Memo applies to administrative guidance issued by DOJ or any other executive agency. The Brand Memo may have particular relevance to providers in medical necessity cases, which frequently involve non-binding guidance and recommendations, such as where the government’s or relator’s theories are grounded in provisions of the Medical Benefit Policy Manual and/or contractors’ local coverage determinations (NCDs and LCDs).

Although the memo’s author, Rachel Brand, has left DOJ, in a June speech, Acting Associate Attorney General Jesse Panuccio reiterated the Brand Memo’s importance to DOJ in its reform of FCA enforcement. As we described in more detail in our June 2018 Client Alert, he also highlighted other measures DOJ is undertaking, including formalizing cooperation credit processes, in an effort to improve FCA enforcement. We will continue to monitor these developments and settlement numbers and will report further in our 2018 Year-End Update.

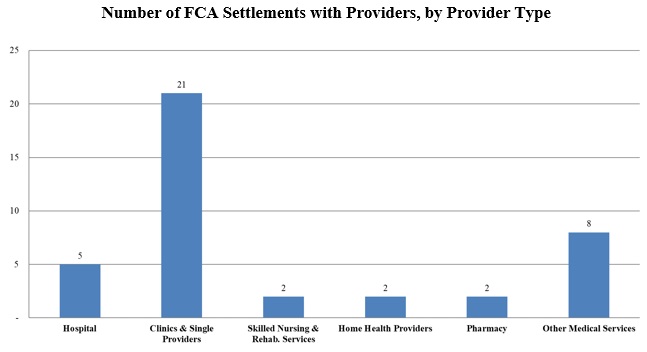

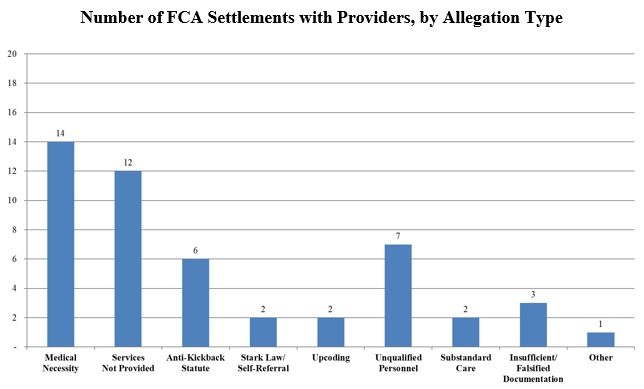

Notwithstanding the lower overall number of settlements, the FCA settlements announced so far this year have rested on the same mélange of legal theories as past years and have involved a number of different types of providers, including hospitals, clinics and single providers, skilled nursing and rehabilitation services, home health care services, and pharmacies.

As indicated in the chart above, for the first half of 2018, the vast majority of FCA health care provider settlements have involved clinics and single providers; however, these settlements made up a disproportionately small amount of the financial recoveries—averaging roughly $2.3 million per case. Within this category, the majority of settlements have resolved actions primarily predicated on legal theories of services not provided (eleven cases), while smaller numbers of settlements included additional theories of medically unnecessary or unreasonable services (five cases), unqualified personnel providing care (four cases), upcoding (three cases), AKS claims (two cases), physician self-referral claims (one case), and the provision of sub-standard care (one case).[4] The second highest number of settlements were with “other” medical services, as depicted in the chart. These services included ambulance services, diagnostic laboratory testing, radiation services, ophthalmology services, intra-operative monitoring services, health management/mental health services, and wound care services.

Consistent with the recent past, the most prevalent legal theory among health care provider settlements was that the provider had billed government health programs for items or services that were not medically necessary. In many of those cases, medical necessity was the sole underlying theory of liability, reflecting DOJ’s continued focus on issues of medical necessity. DOJ also commonly includes medical necessity allegations in broader and more complex allegations of misconduct. For example, an Arizona-headquartered health care organization, that owns and operates twenty-eight acute-care hospitals in multiple states, agreed to pay over $18 million to settle allegations that twelve of its hospitals in Arizona and Colorado had “knowingly submitted false claims to Medicare by admitting patients who could have been treated on a less costly outpatient basis.”[5] According to the press release, these twelve hospitals had knowingly overcharged Medicare patients for short-stay inpatient procedures that should have been billed on an outpatient basis. In addition to these medically unnecessary inpatient admissions, the hospitals allegedly provided falsified documentation in their reports to Medicare by artificially inflating the number of outpatient observation hours received by patients. In addition to the monetary settlement, the health care organization entered into a corporate integrity agreement with HHS OIG, requiring the company to engage in “significant compliance efforts” over the next five years, including retaining an independent review organization to review the accuracy of the company’s claims for services furnished to Medicaid and Medicare beneficiaries.

Lack of medical necessity also served as the underlying legal theory in a settlement with a provider of opioids and other prescription pain killers, as part of the recent focus on cracking down on the nation’s opioid epidemic. In that case, a Tennessee chiropractor and his pain management company agreed to pay $1.45 million, and a pain clinic nurse practitioner agreed to pay $32,000 and surrender her DEA registration, to resolve claims that from 2011 through 2014, the chiropractor and his company “caused pharmacies to submit requests for Medicare and TennCare payments for pain killers, including opioids . . . which had no legitimate medical purpose.”[6] With respect to this settlement, Attorney General Jeff Sessions noted, “[i]f we’re going to end this unprecedented [opioid] drug crisis, which is claiming the lives of 64,000 Americans each year, doctors must stop overprescribing opioids and law enforcement must aggressively pursue those medical professionals who act in their own financial interests, at the expense of their patients’ best interests.”[7] We address the ongoing opioid enforcement efforts further below.

In addition to the settlement involving the Arizona-based health care organization, the first half of 2018 saw a number of other settlements involving multiple-facility providers nationwide, many under more than one theory of liability. For example, in one case involving a Louisville, Kentucky-based company that owns and operates about 115 skilled nursing facilities, DOJ alleged that the company had “knowingly submitted false claims to Medicare for rehabilitation therapy services that were not reasonable, necessary and skilled.”[8] The settlement, which was initiated by two individuals under the qui tam provisions of the FCA, required the company to pay more than $30 million and also resolved allegations that the company had submitted forged pre-admission certifications of patient need for skilled nursing to the State of Tennessee’s Medicaid program. In another case, DOJ settled with a dental provider for $23.9 million following allegations that the company had, throughout clinics in seventeen states, submitted false claims for medically unnecessary dental procedures and for procedures not actually provided.[9] DOJ’s case was initiated by five lawsuits filed under the qui tam provision of the FCA. DOJ likewise settled for $22.51 million with a company that manages nearly 700 hospital-based wound care centers nationwide to resolve allegations that the company had knowingly caused wound care centers to bill Medicare for medically unnecessary and unreasonable procedures.[10] That case arose from two separate lawsuits filed by former employees of the company under the qui tam provision of the FCA.

The first half of 2018 also saw a relatively high number of resolutions resting on theories of services not provided, including nine settlements based on allegations that services billed for were not provided at all. In one settlement, which involved the coordinated effort of the Alaska Medicaid Fraud Control Unit, HHS OIG, and the Alaska Medicaid Program, an Anchorage-based provider of services to individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities agreed to pay nearly $2.3 million to resolve allegations it had billed for services not provided and for overlapping services with the same provider.[11] The settlement also required the health care provider to enter into a five-year corporate integrity agreement with HHS OIG. Finally, in one of the largest civil resolutions of the first half of 2018,[12] a judge found a Houston-area laboratory liable for nearly $30.6 million for overbilling Medicare for services (transportation miles) that the company’s lab technicians had never actually traveled.[13]

B. FCA-Related Case Law Developments

1. Developments in Implied False Certification Theory

Our previous updates discussed in detail the unanimous 2016 Supreme Court decision in Universal Health Services, Inc. v. United States ex rel. Escobar,[14] affirming the validity of an “implied certification” theory for FCA liability following a “rigorous” and “demanding” analysis of whether the alleged fraud was “material” to the government’s decision to pay the claim at issue. Courts have continued to interpret Escobar and unpack the meaning of “materiality” in this context.

In January 2018, the Middle District of Florida overturned a $350 million jury verdict on the grounds that the evidence did not support a finding of FCA materiality and scienter where the government continued making payments to the defendants despite being on notice of defendants’ alleged misconduct.[15] Plaintiffs alleged that the defendants, operators of a chain of skilled nursing facilities and a management services organization, misrepresented the conditions of and treatments provided to patients in its facilities. In support of these allegations, plaintiffs presented a variety of paperwork containing defects such as missing dates or signatures. The judge noted that while the defective paperwork was demonstrably non-compliant with contractual requirements for comprehensive care plans, the government nonetheless made payments and took no steps to enforce compliance. With these facts in mind, the judge concluded there was no reason to believe the deviations from the terms of the comprehensive care plans were material to payment, and that overturning the jury verdict was consistent with Escobar which “rejects a system of government traps, zaps, and zingers that permits the government to retain the benefit of a substantially conforming good or service but to recover the price entirely—multiplied by three—because of some immaterial contractual or regulatory non-compliance.”[16] An appeal of this ruling was filed in early July and is pending in the Eleventh Circuit.

Courts nationwide continue to disagree about the extent to which government payment after awareness of non-compliance defeats the materiality standard. We will continue to watch as the Supreme Court considers whether to hear at least one cert petition seeking clarification of that precise issue, in United States ex rel. Campie v. Gilead Sciences, Inc., during the 2018 term.[17]

2. Developments in “Objective Falsity” Jurisprudence

As we have discussed in prior updates, courts continue to consider the animating logic of the March 2016 AseraCare case, in which the District Court for the Northern District of Alabama, after the government prevailed in the first phase of a bifurcated trial, granted summary judgment sua sponte for the hospice provider on the grounds that the government failed to show evidence of an objective falsehood. In support of its allegation that the defendant hospice provider submitted false claims for services where the patient did not qualify for hospice care, the government had proffered a trial expert’s review of patient medical records. The district court found that a “contradiction based on clinical judgment or opinion alone [i.e. between the government’s expert and another expert or the treating physician] cannot constitute falsity under the FCA as a matter of law.”[18] Other courts have similarly declined to find objective falsity in cases where the challenged care and services were the product of providers’ clinical judgment. For example, in a December 2017 decision, the Central District of California reached a similar conclusion in United States ex rel. Winter v. Gardens Regional Hospital and Medical Center, finding no basis for liability in pleadings premised on questions of medical judgment regarding the appropriateness of hospital admissions.[19] In a similar vein, in June 2017, the district court in United States ex rel. Dooley v. Metic Transplantation Lab held that defendants could only be found to have submitted objectively false claims if they, in their medical opinion, knew that they were selecting medically unnecessary tests.[20]

Two recent circuit court decisions, however, held that medical judgments can be challenged as false or fraudulent for purposes of the FCA, at least in certain circumstances.

First, in United States v. Paulus, the Sixth Circuit rejected a district court’s decision to overturn the conviction of a medical doctor for allegedly fraudulently ordering an unusually high number of angiograms, and then finding high levels of stenosis based on erroneous and exaggerated readings of those angiograms.[21] The district judge found that the medical interpretation of the amount of stenosis shown on angiograms was “incapable of confirmation or contradiction” and not an “objectively verifiable fact,”[22] but the Sixth Circuit strongly disagreed, stating “[w]e believe we were clear then, but we make it explicit now: The degree of stenosis is a fact capable of proof or disproof.”[23] The Department of Justice lauded the Paulus decision, filing a letter with the Eleventh Circuit stating that Paulus “squarely rejected” the reasoning of AseraCare. In a responsive filing, AseraCare argued that the cases are distinguishable due to the factual nature of the determinations being made—while Paulus involved a factual determination about the measurable degree of blockage in arteries, the judgments in AseraCare centered on life expectancy, which AseraCare describes as a judgment that “necessarily and by law involves a subjective opinion.” The Eleventh Circuit heard oral arguments in AseraCare in March 2017, and a decision is forthcoming.

Second, in United States ex rel. Polukoff v. St. Mark’s Hospital,[24] a Tenth Circuit panel held that certifications of “reasonable and necessary” care can be deemed false for purposes of FCA liability if procedures are found to be “not reasonable and necessary under the government’s definition of the phrase.”[25] This decision overturned a District of Utah opinion declaring that a doctor’s opinion regarding the potential uses for patent formen ovale (“PFO”) closures could not be objectively false since the doctor exercised his professional medical judgment in reaching this conclusion.[26] Although PFO closures are typically conducted only on patients who have previously endured a stroke, the provider-defendant believed they had the potential to serve as a “preventative measure” for patients with an “elevated risk of stroke.”[27] As a result of his view that PFO closures had broader potential usage, the doctor performed PFO closures far more often than normal in the industry: in a time period where the Cleveland Clinic performed 37 PFO closures, the defendant performed 861.[28] The Tenth Circuit unanimously rejected the district court’s decision that the doctor’s view of the wider usefulness of PFO closures was sufficient to defeat a finding of falsity, emphasizing that providers cannot use professional judgment as a shield against liability for unnecessary procedures. Rather, for purposes of determining whether a claim is reimbursable, the Tenth Circuit found that government guidance such as the Medicare Program Integrity Manual provides a reliable rulebook for what constitutes “reasonable and necessary” under the FCA.[29] The case will now return to the district court for reconsideration.

The extent to which a disagreement in professional opinion can be construed as an indicator of falsity is not fully settled. Following recent cases, it is clear that prosecutors must provide evidence of falsity beyond mere disagreement of another health professional. Nonetheless, the Paulus and Polukoff decisions suggest that providers’ medical judgment may not be protected when other factors suggest that they veer significantly from the mainstream. The Tenth Circuit’s statements about using government manuals to define “reasonable and necessary” for FCA purposes may prompt particular controversy because as other courts have recognized, these manuals lack the force of law, and in any event, they, too, have vague standards that are susceptible to multiple interpretations. In that regard, key questions remain about the parameters of defining falsity in medical necessity determinations; we will continue to monitor pending litigation in this area and will report on further judicial developments.

3. Developments Regarding the Use of Statistical Sampling

As noted in prior updates, dating back to our 2014 Year-End Update, we continue to track developments in the use of statistical evidence and sampling to support wide-scale FCA allegations, especially against multi-site providers. Two courts recently rejected plaintiffs’ attempts to use statistical data to establish fraud under the FCA. In United States ex rel. Wollman v. The General Hospital Corporation, the District of Massachusetts granted defendants’ motion to dismiss on the grounds that relator’s allegations based on statistical data fell short of pleading specific details regarding the actual submission of claims.[30] Although the First Circuit generally has relaxed pleading standards and allows the use of statistical evidence to strengthen an inference of fraud, the Wollman court found that relators’ use of statistical data fell short of creating any inference that surgeons committed fraud by billing Medicare and Medicaid for “overlapping” surgeries.[31]

Similarly, in April 2018, in United States ex rel. Conroy v. Select Medical Corporation, a magistrate judge in the Southern District of Indiana rejected a relator’s attempt to use statistical sampling to determine “the number of fraudulent Medicare claims and the damages flowing from them.”[32] The court held that the plaintiffs failed to provide any evidence in support of the proposition that showing “a particular Medicare reimbursement claim was fraudulent based on a theory of lack of medical necessity can be done by a random-sampling method.” Instead, the court found that a case-by-case analysis would be necessary to “evaluate whether each particular claim for which the plaintiffs seek relief was actually knowingly false within the meaning of the FCA.”[33] DOJ, despite initially declining to intervene in the case, filed a letter of interest challenging the magistrate judge’s discovery order as “contrary to long-established precedent recognizing statistical sampling as admissible and valid method of proof” in contexts applicable to the FCA.[34] The court has not yet addressed DOJ’s letter.

As the government and FCA relators continue to attempt to support region-wide or nationwide cases against multi-facility providers using statistical sampling evidence, these issues are sure to have an important presence in the FCA case law, and we will continue to monitor and report on them.

C. Opioid Crisis Enforcement Efforts

The government continues to aggressively target the opioid crisis in its criminal, as well as civil, enforcement efforts, with the initial focus on opioid manufacturers widening to include prescribers, and even pharmacy dispensers, of opioids.

On June 6, the CEO of a health care company and four physicians were charged in a superseding indictment as part of an investigation into an alleged $200 million health care fraud scheme involving the distribution of medically unnecessary controlled substances and injections that resulted in patient harm.[35] The indictment alleges that the physicians prescribed over 4.2 million dosage units of medically unnecessary controlled substances to Medicare beneficiaries, including some who were addicted to narcotics. Further, the physicians allegedly required the Medicare beneficiaries to consent to medically unnecessary injections, which were billed to Medicare in order to increase revenue for all defendants. Trial in the Eastern District of Michigan is scheduled to begin at the end of July.

In our 2017 Mid-Year Update, we highlighted DOJ’s announcement of what was then the largest-ever health care fraud enforcement action, involving charges against more than 400 defendants for more than $1.3 billion in fraud. The enforcement action focused heavily on the prescription and distribution of medically unnecessary prescription drugs, including opioids and other narcotics.

On June 28, DOJ announced a new record for the largest health care fraud enforcement action in history.[36] This enforcement action involved charges against 601 individuals across 58 federal districts, allegedly responsible for over $2 billion in fraud losses. Of the individuals charged, 162 defendants (including seventy-six doctors) were charged for playing a role in prescribing and distributing opioids and other narcotics. In the press release, Attorney General Jeff Sessions described the underlying conduct as “despicable crimes” that led DOJ to take “historic new steps to go after fraudsters, including hiring more prosecutors and leveraging the power of data analytics.”[37] Attorney General Sessions emphasized that “[t]his is the most fraud, the most defendants, and the most doctors ever charged in a single operation—and we have evidence that our ongoing work has stopped or prevented billions of dollars’ worth of fraud.”[38] The enforcement action involved coordinated efforts by DOJ’s Criminal Division and Health Care Fraud Unit, HHS OIG, the Drug Enforcement Administration, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, IRS Criminal Investigations, the Department of Labor, State Medicaid Fraud Control Units, and others. HHS Secretary Alex Azar lauded the “Takedown Day” as “a significant accomplishment for the American people,” stating that every dollar recovered in the operation is “a dollar that can go toward providing healthcare for Americans in need[.]”[39]

In the middle of July, DOJ announced Operation Synthetic Opioid Surge, or Operation S.O.S., in an effort to target distribution of synthetic opioids in the districts with the highest rates of overdose deaths.[40] U.S. Attorney’s Offices in key districts will identify a county in which it will prosecute “every readily provable case involving . . . synthetic opioids, regardless of drug quantity.” The goal of the intensive effort, which will be coordinated with the DEA Special Operations Division, is to use these smaller prosecutions to identify larger distribution networks for synthetic opioids and ultimately reduce overdose deaths.

The recent takedown and Operation S.O.S. initiative are further evidence of DOJ’s continued prioritization of the opioid crisis by criminally targeting fraudulent distribution of prescription medications; however, DOJ continues to target these issues through civil remedies as well. On February 27, 2018, DOJ announced the formation of a Prescription Interdiction and Litigation Task Force designed to enforce compliance with federal regulations created to prevent improper prescribing of medications. In his speech announcing the Task Force formation, Attorney General Sessions noted that the Task Force would coordinate with various agencies and employ a wide range of enforcement tools—including the FCA—to crack down on illegal prescriptions.

II. HHS Enforcement Activity

A. HHS OIG Activity

1. 2017 and 2018 Developments and Trends

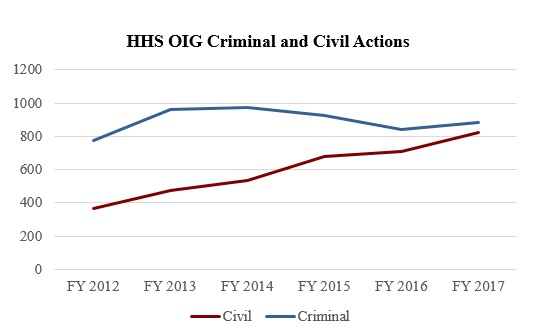

In the period between October 1, 2017, and March 31, 2018, HHS OIG reported 424 criminal actions, a decrease of approximately 9% from the 468 criminal actions reported in the first half of FY 2017.[41] HHS OIG experienced a larger drop—nearly 25%—in the number of civil actions, reporting 349 in the first half of FY 2018, compared to 461 in the first half of FY 2017.[42] While the yearly number of criminal actions has fluctuated over the past several years (see the chart below), the yearly number of civil actions has been steadily rising—a streak which may break in 2018 based on first-half numbers.

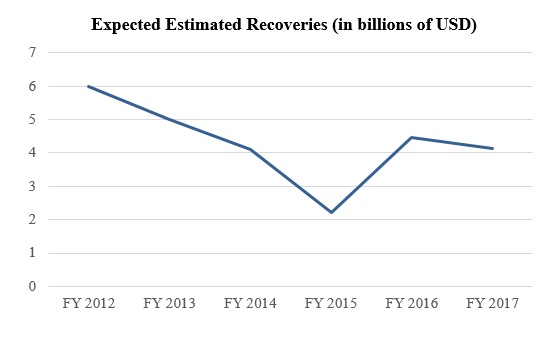

In the first half of FY 2018, HHS OIG also reported expected investigative recoveries of $1.46 billion.[43] In the first half of FY 2017, by contrast, this figure was approximately $2.04 billion.[44] These recovery figures suggest that FY 2018 may continue the general downward shift in HHS OIG’s yearly expected recoveries over the last several years, as depicted in the chart below. This downward trend may be due in part to decreases in the frequency and magnitude of large settlements with pharmaceutical companies. In FY 2012 and FY 2013, for example, HHS OIG’s year‑end reports highlighted a total of approximately $4.35 billion in settlements with pharmaceutical companies, whereas HHS OIG’s year‑end reports for FY 2014 through FY 2017 highlighted a total of only about $1.32 billion in settlements with pharmaceutical companies.[45]

2. Significant HHS OIG Enforcement Activity

a) Exclusions

HHS is required to exclude from participation in the federal health care programs any individual or entity that is (1) convicted of a crime related to Medicare, (2) convicted of a crime related to patient abuse or neglect, (3) convicted of felony health care fraud, or (4) convicted of a felony related to the manufacturing, distribution, prescription, or dispensing of a controlled substance.[46] HHS also has permissive authority to exclude individuals and entities falling into sixteen other categories, including those convicted of fraudulent conduct related to health care, those excluded or suspended from a state health care program, and those HHS determines have paid kickbacks as defined by the Anti‑Kickback Statute.[47]

In the first half of calendar year 2018, HHS OIG reported 1,525 exclusions from the federal health care programs.[48] Of that number, thirty exclusions were of entities, a 9% drop compared to the same period in calendar year 2017 and a 3% drop compared to the same period in calendar year 2016.[49] Notably, this number is an increase as compared to calendar years 2015 and 2014. The entity exclusions included thirteen pharmacies and four entities identified as either community mental health centers or psychology practices.[50] The remaining 1,495 exclusions reported in the Exclusions Database for the first half of FY 2018 were of individuals, 158 of whom were classified as business owners or executives, and 104 of whom were classified as physicians.[51] Among business owners or executives, approximately 25% were affiliated with home health agencies, approximately 7% with pharmacies, and approximately 12% with clinics.[52] Of the excluded physicians, approximately 66% were family practitioners, general practitioners, internists, or psychiatrists.[53]

Consistent with HHS OIG’s focus on pharmacies and on combating the illegal provision of opioids, HHS OIG’s semiannual report to Congress covering the first half of FY 2018 highlighted an exclusion case involving a pharmacy owner in Kentucky who was convicted of illegally dispensing oxycodone, hydrocodone, and pseudoephedrine and was sentenced to thirty years in prison. The pharmacy owner’s exclusion from the federal health care programs will last at least fifty years.[54]

b) Civil Monetary Penalties

Compared to the same period in calendar year 2017, the first half of calendar year 2018 witnessed an uptick in civil monetary penalties (“CMPs”) as a result of settlement agreements and voluntary self‑disclosures. HHS OIG announced 61 CMPs totaling approximately $46 million,[55] marking an increase of nearly 30% in the number of cases, and a 100% increase in total recovery amount, compared to the first half of calendar year 2017.[56] CMPs resulting from self‑disclosures represented approximately 86% of the CMPs, in terms of dollar value, in the first half of the 2018 calendar year, with the largest self‑disclosure settlement representing approximately six times the amount of the largest settlement not involving self‑disclosure. Self‑disclosure cases also accounted for eight of the top ten settlements by dollar amount.

Consistent with the trend in the first half of last year, cases involving allegedly false claims or improper billing practices accounted for the lion’s share—thirty-one cases totaling nearly $35 million— of CMPs imposed by HHS OIG. Employment of individuals who had been excluded from the federal health care programs was the second most common basis for CMPs, accounting for fourteen cases totaling nearly $1.9 million. However, these cases were overshadowed in terms of dollar amount by the eight CMPs involving alleged AKS or Stark Law violations and amounting to nearly $8.9 million in penalties and settlements.

The three largest CMPs assessed against providers in the first half of 2018 are summarized below:

- Northwell Health Inc. (Northwell): On February 13, 2018, after self-disclosing conduct, Northwell agreed to pay approximately $12.7 million to resolve allegations from HHS OIG that Northwell submitted Medicare claims that lacked sufficient documentation for a certain Medicare Local Coverage Determination, “Vertebroplasty and Vertebral Augmentation – Percutaneous, L26439.”[57]

- Shands Jacksonville Medical Center, Inc. (Shands) and University of Florida Jacksonville Physicians, Inc. (UF JPI): Shands and UF JPI made a self‑disclosure to HHS OIG, and on January 30, 2018, reached a settlement of approximately $4.5 million to resolve allegations that Shands and UF JPI submitted Medicare and Medicaid claims for ophthalmology surgical procedures that were not medically necessary.[58]

- Nazareth Hall (Nazareth): Following a self‑disclosure, on February 23, 2018, Nazareth reached a settlement of approximately $4 million to resolve HHS OIG allegations that Nazareth submitted Change of Therapy forms for rehabilitative therapy services without following Medicare requirements.[59]

c) Corporate Integrity Agreements

Although we frequently make observations regarding the types of integrity agreements entered into by HHS OIG, the Government Accountability Office (“GAO”) issued a report earlier this year that provides a comprehensive survey of these agreements from the period spanning from July 2005 through July 2017.[60] The report found that, during this period, HHS OIG entered into 652 agreements[61] with thirty types of entities, but that individual or small group practices, hospitals, and skilled nursing facilities together accounted for over half of all agreements.[62] Cases that ended with integrity agreements most often started with allegations that the relevant entity or individual billed for medically unnecessary services or for services not provided.[63] Significantly, the report also noted that DOJ settlements accompanied 619 of the 652 integrity agreements reached in the period reviewed.[64] Overall, however, the total number of integrity agreements in effect decreased by 44% from 2006 to 2016,[65] as a result of HHS OIG’s self‑described efforts to prioritize entities that pose the most significant fraud risks.[66]

In the first half of calendar year 2018, HHS OIG entered into thirteen corporate integrity agreements (“CIAs”), down from twenty-four in the same period in 2017.[67] In one particularly notable example, an Anchorage, Alaska, non‑profit organization that provides services to individuals with developmental disabilities entered into a five‑year CIA with HHS OIG. Under the agreement, the organization was required to implement significant compliance enhancements, including the appointment of a compliance officer and the establishment of a compliance committee, as well as the implementation of specific compliance controls and review procedures at the board of directors level.[68] HHS OIG has signaled that it views these sorts of requirements as a floor, not a ceiling, for providers’ compliance programs. For example, in a case involving a non‑profit hospital operator accused of violating the FCA by seeking Medicare reimbursement for inpatient services that could have been provided on a less costly outpatient basis,[69] HHS OIG imposed a five‑year CIA that specified similar board- and management-level compliance enhancements, despite the fact that the entity had “voluntarily established a Compliance Program” before the CIA was executed.[70] The agreement specified that the procedures it imposed on the hospital operator were to be treated as minimum requirements for its compliance program.[71]

In other instances, HHS OIG has used CIAs to require significant compliance undertakings more closely tailored to the alleged conduct at issue. For example, in a CIA that involved a parallel settlement with DOJ, a radiation therapy provider that allegedly violated the AKS was required to implement an oversight program to ensure that certain contractual arrangements were “supported by and consistent with fair market valuation reports conducted by independent, objective, and qualified individuals or entities with fair market valuation expertise[.]”[72] Fair market valuations help provide shelter from liability under AKS and the Stark Law for certain contractual arrangements, such as employment compensation arrangements, as they support the relevant arrangement as an arm’s-length transaction that does not account for the value or volume of referrals.

Notably, several of the CIAs entered into so far this year involved individuals in addition to entities. For example, in February, HHS OIG reached a three‑year CIA with a North Carolina eye-care provider and its physician-owner that requires, among other provisions: enhanced training and education, the retention of an independent review organization (“IRO”), and enhanced screening processes for employees and third-party service providers. The physician-owner is required to submit certifications of the practice’s compliance in conjunction with the IRO’s review and reporting activities.[73] In another case, the individual owner of a hospice provider was made a party to a CIA with the provider itself, which imposes a five‑year term and the implementation of a detailed set of management‑level compliance enhancements and controls.[74] And, in at least one case, HHS OIG put in place a CIA that imposes obligations on an individual only, without placing parallel obligations on any entity affiliated with the individual.[75] The agreement requires the individual to do the following, among other things: undergo training on billing, coding, and record documentation, and ensure that the individual’s employees and contractors received such training; engage an IRO to audit the individual’s claims submitted to Medicare and Medicaid; screen the individual’s employees and contractors to ensure their eligibility to participate in the federal health care programs, and remove any individuals who have been excluded from participation; and track and communicate certain “reportable events” to HHS OIG.[76] Under the agreement, breach of any of these obligations would trigger a daily stipulated penalty of $1,000 or $1,500, depending on the obligation breached—as well as the possibility of exclusion from the federal health care programs in the event of certain material breaches.[77]

B. CMS Activity

1. Transparency and Data Accessibility

Over the past few years, CMS has prioritized improving access to data related to the use of Medicare and Medicaid services. On April 13, 2018, CMS released the seventh update of the Market Saturation and Utilization Tool.[78] This tool provides interactive maps and related data sets showing provider services and utilization data for selected health services, and is one of many tools used by CMS to monitor and manage market saturation as a means to help prevent potential fraud, waste, and abuse. The seventh update includes a trend analysis graphing tool that shows the percentage change and trend over time across the available metrics and health service areas. CMS explained that in addition to serving as a monitoring tool to prevent potential fraud and abuse, “[t]he data can also be used to reveal the degree to which use of a service is related to the number of providers servicing a geographic region.”[79] CMS noted that one of the secondary objectives of making the data public is to “assist health care providers in making informed decisions about their service locations and the beneficiary population they serve.”[80]

2. Continued Implementation of Moratoria

As we’ve described in past updates, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act authorizes CMS to impose moratoria on certain regions to prevent new provider enrollments in certain geographic areas identified as fraud “hot spots.” The moratoria are imposed after consultation with DOJ and HHS OIG and reviewed for continued necessity every six months. The moratoria, which block any new provider enrollments for Medicare Part B non-emergency ground ambulance providers and Medicare home health agencies in Florida, Illinois, Michigan, Texas, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey, were reviewed and extended again for a six-month period on January 29, 2018.[81]

C. OCR and HIPAA Enforcement

1. HIPAA Enforcement Actions

HHS’s Office of Civil Rights (“OCR”) reported that as of June 30, 2018, it had reviewed and resolved over 184,614 Health Information Portability and Accountability Act (“HIPAA”) complaints since HIPAA privacy rules went into effect in April 2003.[82] OCR has resolved 96% of these cases (177,194).[83] Since January, OCR has reported only two settlements and one decision from an HHS Administrative Law Judge (“ALJ”), amounting to approximately $7.9 million in fines.[84] If OCR’s enforcement continues at this pace, 2018 will see a dramatic decline in HIPAA enforcement actions. In the 2017 calendar year, OCR announced ten settlements amounting to approximately $19.4 million in fines, and in 2016, OCR reported thirteen settlements totaling approximately $23.5 million.[85] It remains to be seen whether the downtick in enforcement during the first half of 2018 signals a change in priorities, or whether we will see an acceleration of HIPAA settlements in the second half of the year.

On February 1, 2018, OCR announced the first HIPAA settlement of the year, with Fresenius Medical Care North America (“FMCNA”), a nationwide dialysis provider that also runs labs, urgent care centers, and post-acute practices. FMCNA agreed to pay $3.5 million and adopt a comprehensive corrective action plan in order to settle potential HIPAA violations in connection with five data breaches that occurred at separate FMCNA-owned entities over a five-month period in 2012, which impacted 521 individuals.[86] Following an investigation, OCR found that FMCNA “failed to conduct an accurate and thorough risk analysis of potential risks and vulnerabilities to the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of all its [electronic protected health information (PHI)].”[87] OCR Director Roger Severino commented, “[t]he number of breaches, involving a variety of locations and vulnerabilities, highlights why there is no substitute for an enterprise-wide risk analysis for a covered entity.”[88] A corrective action plan requires the company to complete a risk analysis and risk management plan, revise policies and procedures, develop an encryption report, and provide employee education on policies and procedures.[89]

Less than two weeks later, OCR announced a $100,000 settlement with Filefax, Inc. (“Filefax”), a company that stored and delivered medical records. The case came to the attention of the authorities in February 2015 when OCR received an anonymous complaint alleging that an individual took paper files out of an unlocked dumpster outside of a Filefax office in Illinois and brought it to a nearby paper shredding shop, hoping to receive payment for providing recyclable material. The complaint led to an OCR investigation. Filefax dissolved during the course of the investigation, which ultimately concluded that “Filefax impermissibly disclosed the PHI of 2,150 individuals by leaving the PHI in an unlocked truck in the Filefax parking lot, or by granting permission to an unauthorized person to remove the PHI from Filefax, and leaving the PHI unsecured outside the Filefax facility.”[90] This settlement cautions against the careless handling of PHI and demonstrates that companies cannot escape obligations under the law for HIPAA violations even after closing for business. The receiver appointed to liquidate the assets of Filefax, has agreed to pay the $100,000 and properly store and dispose the remaining medical records in a HIPAA-compliant manner.[91]

On June 18, 2018, an HHS ALJ granted summary judgment against the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (“MD Anderson”), requiring the provider to pay $4.3 million in civil monetary penalties for HIPAA violations.[92] This is the fourth largest amount awarded to OCR by an ALJ or secured in a settlement for HIPAA violations; it is also the second summary judgment victory in OCR’s history of HIPAA enforcement.[93] The litigation arose out of three data breaches from 2012 and 2013 involving the theft of an unencrypted laptop from an MD Anderson employee and the loss of two unencrypted USB thumb drives containing the information of 33,500 individuals. MD Anderson “failed to adopt an effective mechanism” to protect patient data.[94] The ALJ rejected the argument that stolen information is only disclosed when it is viewed by a third party, holding, “The plain language of the regulation doesn’t suggest that. Moreover, to interpret the regulation so narrowly as Respondent suggests would render its prohibitions against unauthorized disclosure to be meaningless.”[95] In a statement regarding the decision, Director Severino underscored that “OCR is serious about protecting health information privacy and will pursue litigation, if necessary, to hold entities responsible for HIPAA violations.”[96]

2. Cybersecurity

Protection of patients’ confidential information, and electronically stored information in particular, continues to be a high priority for HHS enforcement, just as cybersecurity and data privacy issues explode in complexity and public attention. As discussed in past updates,[97] OCR continues to issue monthly “Cybersecurity Newsletters” in order to provide guidance on what specific security measures providers can take to decrease exposure to various security threats and vulnerabilities that exist in the health care sector, and how to reduce breaches of electronic-protected health information (“ePHI”).[98] HHS has not said that following the measures outlined in these newsletters creates any kind of safe harbor; rather, the newsletters are designed to “assist” the regulated community to become more knowledgeable about risk areas. Providers would do well to adhere to this guidance to avoid being caught in the crosshairs of OCR.[99] Brief summaries of the newsletters that have been issued so far this year are below.

- The January newsletter discusses the issue of cyber extortion, which may include stealing sensitive data such as ePHI, and explains what organizations can do to prevent falling victim to attackers, including implementing an organization-wide risk analysis and risk management program, training employees, patching systems, and encrypting sensitive data. Organizations are encouraged to remain vigilant for new and emerging cyber threats.[100]

- OCR’s February newsletter warns against the dangers of “phishing,” a type of cyberattack used to trick individuals to disclose sensitive information electronically by impersonating a trustworthy source, and provides tips on avoiding phishing attacks.[101]

- The purpose of the April newsletter is to provide a concise explanation of the differences between a “risk analysis” required by the HIPAA Security Rule’s regulatory requirement and a “gap analysis.” In short, a risk analysis is a comprehensive, enterprise-wide evaluation to identify the ePHI and the risks and vulnerabilities to the ePHI; the results of a risk analysis may be used to make enterprise-wide modifications to ePHI systems. By contrast, a gap analysis is a narrower examination of an enterprise to assess whether certain controls or safeguards required by the Security Rule have been implemented and to spot “gaps.”[102]

- The May newsletter reminds organizations about the importance of the physical security of workstations to safeguard access to ePHI, which OCR notes is often overlooked. OCR warns that “[f]ailure to take reasonable steps regarding physical security may have serious consequences,” citing investigations that have resulted in hefty fines for violations of HIPAA’s Security Rule.[103]

- Finally, the June newsletter provides guidance on software vulnerabilities and the necessity of patching software bugs to close security vulnerabilities and prevent hackers from gaining unauthorized access to a user’s computer or an organization’s network. OCR sets forth the responsibilities of HIPAA-covered entities and business associates to conduct a risk analysis of the potential vulnerabilities to the confidentiality of the ePHI they hold; this includes identifying and mitigating risks and vulnerabilities that unpatched software poses to an organization’s ePHI.[104]

III. Anti-Kickback Statute

During the first six months of 2018, the AKS has remained one of the most prominent theories of liability in health care enforcement actions. That is perhaps unsurprising, since the government typically takes the position that the damages resulting from AKS liability are the full amount of the claims supposedly “tainted” by the alleged kickbacks. But given the interplay between the AKS and the FCA, the numerous resulting elements of proof for an AKS case, and the complexities of the AKS’s many safe harbors, AKS theories also continue to be actively debated in the health law field and in the courts. Below, we summarize the guidance and case law developments that explore the scope of that potential liability.

A. Notable HHS OIG Advisory Opinions

HHS OIG issued a number of advisory opinions discussing the AKS in the first half of 2018. Notably, the Office gave its imprimatur to each arrangement on which companies requested its input, from sharing savings generated from cost-reduction measures with health care providers to providing support resources to caregivers of patients with chronic conditions.

On January 5, HHS OIG considered an arrangement under which neurosurgeons implementing cost-reduction measures with respect to spinal fusion surgeries split the savings from these measures with the medical center in which they operate.[105] These cost-reduction measures included a shift to using certain products only on an as-needed basis and standardizing the selection of certain devices and supplies based on price.[106] In concluding that this arrangement presented a low risk of AKS violations, HHS OIG noted approvingly safeguards designed to reduce neurosurgeons’ incentive to increase referrals to the medical center. These safeguards included distributing the incentive payments on a per-surgeon, rather than per-patient, basis; reviewing patient data to confirm a historically consistent selection of patients; reserving a portion of the savings for administrative expenses that would otherwise be distributed to the neurosurgeons; and tying incentive payments to verifiable cost savings attributable to each recommendation implemented in a procedure.[107]

On May 31, HHS OIG opined that an arrangement under which a not-for-profit health center would use state Department of Health grant funds to give a county clinic a computer, videoconferencing software, and other telemedicine items to enable the county clinic to provide health care consultation services remotely would present a low risk of AKS violations.[108] The agency noted that this donation of equipment could conceivably induce the county clinic to refer patients to the health center, but found that the risk of such referrals was low given the clinic would not recommend the health center, or any other specific health care provider, to patients, and that the health center was located 80 miles from the county clinic.[109]

On June 14, HHS OIG analyzed the use of a preferred hospital network as part of Medicare Supplemental Health Insurance (“Medigap”) policies, whereby insurance companies would contract with hospitals for discounts on Medicare inpatient deductibles for their policyholders and then provide a $100 credit to policyholders who utilized an in-network hospital for their inpatient stay.[110] HHS OIG first concluded that the arrangement did not meet the requirements for protection under either the safe harbor for waivers of beneficiary coinsurance and deductible amounts or the safe harbor for reduced premium amounts offered by health care plans.[111] The safe harbor for coinsurance and deductible waivers specifically excludes such waivers when they are part of an agreement with insurers, and the safe harbor for reduced premium amounts requires that all enrollees be offered the same cost‑sharing or reduced premium amounts.[112] HHS OIG then concluded that, notwithstanding the absence of safe harbor protection, the arrangement presented a low risk of AKS violations because neither the discounts nor the premium credits would increase per-service Medicare payments, the arrangement would have little impact on patient utilization, and physicians would receive no remuneration as a result of the arrangement.[113]

On June 18, HHS OIG issued an opinion regarding whether a non-profit medical center may provide support resources and services to family members and other caregivers who care for patients with chronic conditions.[114] The provider proposed to give those caregivers, among other things, educational sessions, support groups, rental iPods, and low-fee stress reduction workshops.[115] HHS OIG noted that certain services the provider made available to the caregivers alleviated the caregivers’ financial burdens in providing care and could influence the caregivers to refer patients to the provider, and HHS OIG determined that no exception to the Beneficiary Inducements CMP or AKS applied.[116] However, HHS OIG determined that it would not impose sanctions on the provider, because (1) the services mostly benefitted caregivers, and posed a low risk of influencing them to select the provider for any particular federally reimbursable services; (2) all caregivers could access the services; (3) the provider did not “actively market” the services; and (4) the provider’s practices posed little risk of increasing costs incurred by the federal health care programs. For these reasons, HHS OIG concluded that the provider’s conduct would not subject it to sanctions under the AKS.[117]

B. Notable Case Law Involving the AKS

While the first half of 2018 was relatively quiet with respect to AKS case law, there were a couple of notable opinions. In particular, the Third Circuit rejected a “but for” causation standard for establishing FCA liability predicated on alleged AKS violations, while an Illinois district court rejected an AKS theory as too speculative. We discuss both below.

In January, the Third Circuit affirmed a U.S. District Court for the District of New Jersey ruling granting summary judgment to a pharmaceutical company accused of FCA and AKS violations in United States ex rel. Greenfield v. Medco Health Solutions, Inc.[118] The relator alleged that a pharmacy (Accredo Health Group), which provided home care for patients with hemophilia, violated the AKS, and in turn the FCA, when it made donations to two charities that then recommended the company to hemophilia patients.[119] The District Court denied the relator’s motion for summary judgment and granted the company’s, on the ground that the relator was unable to show that the charities’ referral of several federally insured patients resulted from the pharmacy’s charitable contributions.[120]

On appeal, the relator argued that the District Court erred in requiring a “direct link” between the contributions and the referrals.[121] The government filed an amicus brief contending that the Court erred “to the extent that it required relator to prove a causal connection between the kickbacks and the claims.”[122] In other words, “the district court incorrectly appeared to believe it was necessary for relator to show that the kickbacks in fact corrupted the charities’ decision to refer patients to” the pharmacy, and that “those referrals and recommendations in fact corrupted the patients’ decisions to use” the company’s services.[123] Instead, the government urged the Court to hold that “relator is not required to prove that the kickbacks caused the charities to make the referrals and recommendations or that the referrals and recommendations caused the patients to use” the pharmacy’s services.[124]

The Third Circuit affirmed the District Court’s grant of summary judgment in favor of the company, holding that a relator must, at minimum, show that at least one of the patients for whom the company provided services and submitted reimbursement claims was “exposed to” a referral from one of the charities to which the company donated.[125] Addressing the parties’ respective arguments about what suffices as FCA proof in the AKS context, the Third Circuit explained that “[i]t is not enough . . . to show temporal proximity between [the company’s] alleged kickback plot and the submission of claims for reimbursement. Likewise, it is too exacting to follow [the company’s] approach, which requires a relator to prove that federal beneficiaries would not have used the relevant services absent the alleged kickback scheme.”[126] The Third Circuit therefore largely adopted the government’s view that a “but for” causation standard would be unworkable in this context, holding instead that relators must present “some record evidence that shows a link between the alleged kickbacks and the medical care received by at least one of” the company’s federally insured patients.[127]

In United States v. United Healthcare Ins. Co., the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois granted a health care insurer’s motion to dismiss a relator’s complaint alleging FCA violations predicated on alleged AKS violations.[128] The defendant was a Medicare Advantage plan that offered, among other services, in-home physical examinations to its patients and $25 Walmart gift cards to patients who accepted offers to join the in-home program.[129] The relator, a patient of the company who participated in the in-home program, alleged that the program violated the FCA because the in-home visits were not medically necessary and led to the procurement of risk adjustment data that could lead to a patient receiving a higher risk designation by CMS, thereby increasing the per-month payment the company would receive from the government for that patient.[130] The Court rejected the relator’s theory as too speculative. The Court noted that the company “ha[d] neither received a kickback for its remunerations nor has Medicare been injured through increased reimbursements.”[131] Rather, the company “paid for the in-home examinations itself, and then provided services to its plan participants free of charge. This does not violate the purpose of the Anti-Kickback Statute—’to prevent kickbacks from influencing the provision of services that are charged to Medicare.'”[132]

IV. Stark Law

The federal physician self-referral law, commonly known as the Stark Law, provides for strict liability for any physician who refers to an entity with which it has a “financial relationship,” which is broadly defined, and even more broadly interpreted by DOJ and HHS OIG. The Stark Law has been a frequent target of proposed reforms for many years (as discussed in our previous alerts ), reflecting industry and regulator recognition that the Stark Law sometimes creates unintentional and unnecessary restrictions on innovative and efficient health care arrangements. But in the main, those reform efforts have stalled and died before offering meaningful relief. During the first half of 2018, however, there were several notable developments relating to the Stark Law that may finally result in actual reform.

A. Regulatory and Legislative Updates

In January 2018, CMS Administrator Seema Verma announced that CMS, DOJ, and HHS OIG would undertake an inter-agency review of the Stark Law.[133] The review was spurred by feedback from providers as part of CMS’s “Patients Over Paperwork” Initiative,[134] which sought industry feedback about how to reduce burdensome regulations. According to Administrator Verma, the Stark Law was one of the most commonly identified of the “burdensome regulations and burdensome issues.”[135] Administrator Verma noted that the Stark Law was “developed a long time ago” and that there is a “need to bring along some of those regulations” to account for modern developments in payment models and health delivery systems.[136] Although Administrator Verma acknowledged that the solution may require “Congressional intervention,” she confirmed that CMS is committed to “working through it.”[137]

In June, CMS requested feedback on possible regulatory changes to the Stark Law, suggesting a willingness to act, separate from any Congressional action.[138] The agency stated that lowering Stark Law hurdles would support coordinated care.[139] Eric Hargan, Deputy Secretary at HHS, further stated that “[r]emoving unnecessary government obstacles to care coordination is a key priority for this Administration.”[140]

CMS explained that it is interested in addressing “real or perceived” obstacles to coordinated care that are caused by the Stark Law.[141] Beyond simply clarifying or simplifying the current law, the agency asked commenters whether the existing exceptions to the Stark law are useful and whether the agency should create new exceptions.[142] It also requested that commenters share ideas for defining important concepts such as “commercial reasonableness” and “fair market value” within exceptions to the Stark Law.[143] CMS also asked whether increased transparency could address problems, suggesting that transparency measures could include disclosures about pricing or a physician’s financial relationships.

Among other related items, CMS is seeking suggestions regarding:

- Existing or potential arrangements that involve designated health service (“DHS”) entities and referring physicians that participate in “alternative payment models or other novel financial arrangements,” regardless of whether such models and financial arrangements are sponsored by CMS;

- Exceptions to the Stark Law that would protect financial arrangements between DHS entities and referring physicians who participate in the same alternative payment model;

- Exceptions to the Stark Law that would protect financial arrangements that involve “integrating and coordinating care outside of an alternative payment model”; and

- Addressing the application of the Stark Law to financial arrangements among providers in “alternative payment models and other novel financial arrangements.”[144]

B. Notable Stark Law Enforcement

There were also two notable Stark Law enforcement actions in the first half of 2018.

In January, two California urologists agreed to pay more than $1 million to settle allegations that they had violated the Stark Law and the AKS.[145] The doctors, who own and operate both a urology practice and a radiation oncology center, allegedly submitted and caused the submission of false claims to Medicare for image-guided radiation therapy by billing for their own image-guided radiation therapy referrals to their oncology center. The two practices were separate entities, even though both owned by the urologists, and the financial arrangements did not comply with any exceptions to the Stark Law.[146] This case is a warning for providers who own businesses that provide complementary services.

In March, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Hamot (“Hamot”), a Pennsylvania hospital, and Medicor Associates Inc. (“Medicor”), a cardiology group, agreed to pay $20.75 million to settle allegations that they violated a number of statutes, including the AKS and the Stark Law.[147] DOJ alleged that they orchestrated a kickback scheme for patient referrals when Hamot paid Medicor up to $2 million per year under twelve physician and administrative services arrangements that had been created to secure patient referrals from the cardiology group. Hamot allegedly had no legitimate need for the contracted services, and in some instances the services were duplicative or not performed at all.[148] Notably, the claims were brought by a whistleblower, and the federal government initially declined to intervene. The whistleblower proceeded on his own and won summary judgment on his claims that some of the arrangements violated the Stark Law, which in turn caused false claims to be knowingly submitted to federal health programs in violation of the FCA.[149] The whistleblower received over $6 million as part of the settlement.[150] The whistleblower’s post-declination success may encourage other whistleblowers to proceed on their own, even in complicated Stark Law cases such as this one.

V. CONCLUSION

As these issues and others important to the health care provider community continue to develop, we will track them and report back in our 2018 Year-End Update.

[1] See Gibson Dunn 2017 Mid-Year FDA and Health Care Compliance and Enforcement Update – Providers (Sept. 4, 2017) [hereinafter “Gibson Dunn 2017 Mid‑Year Update”].

[2] Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Electronic Health Records Vendor to Pay $155 Million to Settle False Claims Act Allegations (May 31, 2017), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/electronic-health-records-vendor-pay-155-million-settle-false-claims-act-allegations.

[3] U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Associate Attorney General Rachel Brand, Limiting Use of Agency Guidance Documents In Affirmative Civil Enforcement Cases (Jan. 25, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/file/1028756/download.

[4] The total is greater than twenty-one because some cases had multiple claims.

[5] Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Banner Health Agrees to Pay Over $18 Million to Settle False Claims Act Allegations (Apr. 12, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/banner-health-agrees-pay-over-18-million-settle-false-claims-act-allegations.

[6] Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Tennessee Chiropractor Pays More Than $1.45 Million to Resolve False Claims Act Allegations (Jan. 24, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/tennessee-chiropractor-pays-more-145-million-resolve-false-claims-act-allegations.

[7] About a month later, at the end of February, Attorney General Sessions announced that there would be a new, special task force devoted to targeting opioid drug manufacturers and distributors who were fueling the opioid epidemic. Dan Mangan, Attorney General Jeff Sessions Announces New Opioid Task Force to Target Drug Manufacturers, Distributors Who Fuel Prescription Painkiller Epidemic, CNBC (Feb. 27, 2018), https://www.cnbc.com/2018/02/27/attorney-general-jeff-sessions-announces-new-opiod-task-force.html.

[8] Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Signature HealthCARE to Pay More Than $30 Million to Resolve False Claims Act Allegations Related to Rehabilitation Therapy (June 8, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/signature-healthcare-pay-more-30-million-resolve-false-claims-act-allegations-related.

[9] Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Dental Management Company Benevis and Its Affiliated Kool Smiles Dental Clinics to Pay $23.9 Million to Settle False Claims Act Allegations Relating to Medically Unnecessary Pediatric Dental Services (Jan. 10, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/dental-management-company-benevis-and-its-affiliated-kool-smiles-dental-clinics-pay-239.

[10] Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Healogics Agrees to Pay Up to $22.51 Million to Settle False Claims Act Liability for Improper Billing of Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy (June 20, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/healogics-agrees-pay-2251-million-settle-false-claims-act-liability-improper-billing.

[11] Press Release, Alaska Dep’t of Law, The ARC of Anchorage to Pay Nearly $2.3 Million Dollars to Settle Medicaid False Claims Act Allegations (Apr. 24, 2018), http://www.law.state.ak.us/press/releases/2018/042418-MFCU.html.

[12]Amount not reflected in the data above because the case went to trial.

[13]United States ex rel. Drummond v. BestCare Laboratory Services, LLC., No. CV H-08-2441, 2018 WL 1609578, at *3 (S.D. Tex. Apr. 3, 2018).

[14] 136 S. Ct. 1989 (2016).

[15] United States ex rel. Ruckh v. Salus Rehabilitation, LLC, 304 F. Supp. 3d 1258 (M.D. Fla. 2018).

[16] Id. at 1263.

[17] In our 2017 Year-End Update, we discussed Gilead Sciences’ petition for certiorari to the Supreme Court, asking for review of the Ninth Circuit’s decision in United States ex rel. Campie v. Gilead Sciences, Inc. The Court has yet to issue a decision on whether they will grant the petition. See Pet. for a Writ of Cert., Gilead Sciences Inc. v. United States ex rel. Campie (filed Dec. 26, 2017).

[18] United States ex rel. Paradies v. AseraCare, Inc., 176 F. Supp. 3d 1282 (N.D. Ala. 2016).

[19] United States ex rel. Winter v. Gardens Regional Hospital and Medical Center, No. 14-CV-08850, 2017 WL 8793222 (C.D. Cal. Dec. 29, 2017).

[20] United States ex rel. Dooley v. Metic Transplantation Lab, No. 13-CV-07039, 2017 WL 4323142 (C.D. Cal. June 27, 2017).

[21] United States v. Paulus, 894 F.3d 267 (6th Cir. 2018).

[22] United States v. Paulus, 2017 WL 908409 (E.D. Ky. Mar. 7, 2017), rev’d in part, vacated in part, 894 F.3d 267 (6th Cir. 2018).

[23] Paulus, 894 F.3d, at 275.

[24] United States ex rel. Polukoff v. St. Mark’s Hospital, No. 17-cv-4014, 2018 WL 3340513 (10th Cir. July 9, 2018).

[25] Id.

[26] United States ex rel. Polukoff v. St. Mark’s Hospital, No. 2:16-cv-00304, 2017 WL 237615 (D. Utah Jan. 19, 2017), rev’d and remanded sub nom. United States ex rel. Polukoff v. St. Mark’s Hospital, No. 17-cv-4014, 2018 WL 3340513 (10th Cir. July 9, 2018).

[27] Id.

[28] Polukoff, No. 17-cv-4014, 2018 WL 3340513, at *4.

[29] Id. at *8.

[30] United States ex rel. Wollman v. The General Hospital Corporation, No. 1:15-cv-11890, 2018 WL 1586027 (D. Mass. Mar. 30, 2018).

[31] Id.

[32] United States ex rel. Conroy v. Select Med. Corp., 307 F. Supp. 3d 896, 905 (S.D. Ind. 2018).

[33] Id.

[34] The United States’ Statement of Interest in Support of Relators’ Objection to Magistrate Judge’s April 2, 2018 Order Concerning the Use of Statistical Sampling, 307 F. Supp. 3d 896, (S.D. Ind. 2018).

[35] See Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Health Care CEO and Four Physicians Charged in Superseding Indictment in Connection with $200 Million Health Care Fraud Scheme Involving Unnecessary Prescription of Controlled Substances and Harmful Injections (June 6, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/health-care-ceo-and-four-physicians-charged-superseding-indictment-connection-200-million.

[36] See Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, US Dep’t of Justice, National Health Care Fraud Takedown Results in Charges Against 601 Individuals Responsible for Over $2 Billion in Fraud Losses (June 28, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/national-health-care-fraud-takedown-results-charges-against-601-individuals-responsible-over.

[37] Id.

[38] Id.

[39] Id.

[40] Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Attorney General Jeff Sessions Announces the Formation of Operation Synthetic Opioid Surge (S.O.S.) (July 12, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/attorney-general-jeff-sessions-announces-formation-operation-synthetic-opioid-surge-sos.

[41] See U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of the Inspector Gen., Semiannual Report to Congress, at 4 (Oct. 1, 2017 – Mar. 31, 2018), https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/archives/semiannual/2018/sar-spring-2018.pdf [hereinafter “2018 SA Report”]; U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of the Inspector Gen., Semiannual Report to Congress, at ix (Oct. 1, 2016 – Mar. 31, 2017), https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/archives/semiannual/2017/sar-spring-2017.pdf [hereinafter “2017 SA Report”].

[42] See 2018 SA Report at 4; 2017 SA Report at ix.

[43] See 2018 SA Report at 4.

[44] See 2017 SA Report at ix.

[45] See U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of the Inspector Gen., Semiannual Report to Congress (Apr. 1, 2012 – Sept. 30, 2012), https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/archives/semiannual/2012/fall/sar-f12-fulltext.pdf ; U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of the Inspector Gen., Semiannual Report to Congress (Apr. 1, 2013 – Sept. 30, 2013), https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/archives/semiannual/2013/SAR-F13-OS.pdf ; U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of the Inspector Gen., Semiannual Report to Congress (Apr. 1, 2014 – Sept. 30, 2014), https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/archives/semiannual/2014/sar-fall2014.pdf ; U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of the Inspector Gen., Semiannual Report to Congress (Apr. 1, 2015 – Sept. 30, 2015), https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/archives/semiannual/2015/sar-fall15.pdf ; U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of the Inspector Gen., Semiannual Report to Congress (Apr. 1, 2016 – Sept. 30, 2016), https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/archives/semiannual/2016/sar-fall-2016.pdf ; U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of the Inspector Gen., Semiannual Report to Congress (Apr. 1, 2017 – Sept. 30, 2017), https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/archives/semiannual/2017/sar-fall-2017.pdf.

[46] 42 U.S.C. § 1320a‑7(a).

[47] 42 U.S.C. § 1320a‑7(b).

[48] See U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of the Inspector Gen., LEIE Downloadable Databases, https://oig.hhs.gov/exclusions/exclusions_list.asp (last visited June 28, 2018) [hereinafter “Exclusions Database”].

[49] See Gibson Dunn 2017 Mid‑Year Update.

[50] See Exclusions Database.

[51] See id.

[52] See id.

[53] See id.

[54] See 2018 SA Report at 6, 36.

[55] Data gathered through HHS OIG press releases and publicly available information. See generally U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of the Inspector Gen., Civil Monetary Penalties and Affirmative Exclusions, http://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/enforcement/cmp/index.asp (last visited July 24, 2018) [hereinafter “CMP Assessments”]; U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of the Inspector Gen., Provider Self-Disclosure Settlements, http://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/enforcement/cmp/psds.asp (last visited July 24, 2018) [hereinafter “Provider Self-Disclosure Settlements”].

[56] See Gibson Dunn 2017 Mid‑Year Update at II.A.3.b (stating that “[i]n the first half of the 2017 calendar year, HHS OIG announced 47 CMPs as a result of settlement agreements and self-disclosures and recovered nearly $23 million”).

[57] Provider Self‑Disclosure Settlements, supra note 55.

[58] Id.

[59] Id.

[60] See U.S. Gov’t Accountability Office, GAO-18-322, Dep’t of Health & Human Servs.: Office of Inspector General’s Use of Agreements to Protect the Integrity of Federal Health Care Programs (Apr. 2018), https://www.gao.gov/assets/700/691349.pdf.

[61] Id. at 8.

[62] Id. at 11-12.

[63] See id. at 16-17.

[64] Id. at 10.

[65] Id. (GAO used partial-year data for 2005 and 2017, so compared the full-year data from 2006 through 2016.)

[66] Id.

[67] See U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of Inspector Gen., Corporate Integrity Agreement Documents, https://oig.hhs.gov/compliance/corporate-integrity-agreements/cia-documents.asp#cia_list (last visited July 3, 2018) [hereinafter “CIA Documents”].

[68] See Corporate Integrity Agreement Between the Office of Inspector Gen. of the Dep’t of Health & Human Servs. & Arc of Anchorage 1-16 (Apr. 23, 2018), https://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/cia/agreements/Arc_of_Anchorage_04232018.pdf.

[69] See Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Banner Health Agrees to Pay Over $18 Million to Settle False Claims Act Allegations (Apr. 12, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/banner-health-agrees-pay-over-18-million-settle-false-claims-act-allegations.

[70] Corporate Integrity Agreement Between the Office. of Inspector Gen. of the Dep’t of Health & Human Servs. & Banner Health 1 (Apr. 9, 2018), https://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/cia/agreements/Banner_Health_04092018.pdf.

[71] Id.

[72] Corporate Integrity Agreement between the Office of Inspector Gen. of the Dep’t of Health & Human Servs. & Integrated Oncology Network Holdings, LLC, et al. 22 (Mar. 19, 2018). See also Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Radiation Therapy Company Agrees to Pay up to $11.5 Million to Settle Allegations of False Claims and Kickbacks (Mar. 29, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/radiation-therapy-company-agrees-pay-115-million-settle-allegations-false-claims-and.

[73] See Integrity Agreement Between the Office of Inspector Gen. of the Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Albemarle Eye Center, PLLC, & Jitendra Swarup, M.D. 1-5, 11-13 (Feb. 5, 2018).

[74] See Corporate Integrity Agreement Between the Office of Inspector Gen. of the Dep’t of Health & Human Servs. and 365 Hospice, LLC and John C. Rezk 1-15 (Feb. 8, 2018).

[75] See generally Integrity Agreement Between the Office of Inspector Gen. of the Dep’t of Health & Human Servs. & Sureshkumar Muttath, M.D. (May 11, 2018), https://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/cia/agreements/Sureshkumar_Muttath_MD_05112018.pdf.

[76] Id. at 2-9.

[77] See id. at 15-16.

[78] Ctrs. for Medicare & Medicaid Servs., Market Saturation and Utilization Dataset 2018-04-13 (Apr. 13, 2018), https://data.cms.gov/Special-Programs-Initiatives-Program-Integrity/Market-Saturation-And-Utilization-Dataset-2018-04-/x3vv-caiy.

[79] Ctrs. for Medicare & Medicaid Servs., Market Saturation and Utilization Data Tool (Apr. 13, 2018), https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2018-Fact-sheets-items/2018-04-13.html.

[80] Id.