March 7, 2019

Two years into the Trump Administration, the regulatory and enforcement landscape impacting health care providers continues to be extraordinarily dynamic and complex. Recent policy statements and changes indicate that while the government’s health oversight enforcement efforts remain very robust in some areas, particularly in opioid-related cases, there may be a more tempered approach in other areas. For example, consistent with prior pronouncements, the Trump Administration evidenced a further move away from health care regulation in December 2018 when it published a 119-page report suggesting, among other policy changes, an overall easing of state and federal health care laws in an effort to promote market efficiency.[1] And, as we discuss further below, the Affordable Care Act continues to be challenged in the court system following legislative removal of the statute’s individual mandate and other developments.

Through the end of 2018, the U.S. Department of Justice (“DOJ”) and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (“HHS”) continued to achieve resolutions in a steady stream of investigations of health care providers, which featured substantial financial recoveries and negotiated corporate integrity agreements (“CIAs”)—albeit on a smaller scale than that seen during the Obama administration. Moreover, the enforcement tone from the top appears to be shifting. As Deputy Associate Attorney General Stephen Cox stated at the 2019 Advanced Forum on False Claims and Qui Tam Enforcement, the DOJ is committed to its role as “gatekeeper,” to prevent “non-meritorious” or “abusive” qui tam cases from going forward:

Bad cases that result in bad case law inhibit our ability to enforce the False Claims Act in good and meritorious cases . . . . This is why we have instructed our lawyers to consider dismissing qui tam cases when they are not in our best interests. This authority is an important tool to protect the integrity of the False Claims Act and the interests of the United States.[2]

In his address, Deputy Associate Attorney General Cox discussed another recent DOJ reform signaling a shift away from certain affirmative enforcement actions: its ban on using guidance documents and other non-legally binding materials to create binding requirements. He stated that “it is improper to try to use guidance to bind the public by imposing legal obligations beyond those already enshrined in existing statutes or properly promulgated regulatory provisions. Put simply, agency guidance should educate, not regulate.”[3]

In this year-end update, we begin with an overview of recent DOJ and HHS enforcement efforts affecting health care providers, including a review of notable case law developments in the False Claims Act (“FCA”) space, followed by a discussion of recent regulatory and case law developments in the Anti-Kickback Statute (“AKS”) and the Stark Law.

As always, we are happy to discuss these developments with you. A further collection of recent publications and presentations on these and other key issues is available here.

I. DOJ ENFORCEMENT ACTIVITY

A. False Claims Act Enforcement Activity

The second half of 2018 continued the recent downward trend in the number of FCA health care provider settlements as compared to prior years. In the 2018 calendar year, the DOJ announced a total of about 65 settlements involving providers, as compared to 87 resolutions and 106 resolutions in 2017 and 2016, respectively. These 65 settlements amounted to approximately $985 million, which is below the $1.2 billion and $1.1 billion collected by the government from health care providers in FCA settlements in the prior two years. As a typical FCA case can take two years or more to investigate before reaching resolution or an intervention decision by the government, it is difficult to say whether the lower number of settlements in 2018 compared to prior years is due to a change in DOJ policies or priorities. There is reason to anticipate, however, that providers may have success pushing back on aggressive FCA enforcement going forward, if the Brand Memo and related statements by the DOJ are any indication.

Indeed, the DOJ continues to announce policy changes that, individually and in the aggregate, clearly suggest a more tempered affirmative civil enforcement approach. In November, Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein announced a revised DOJ policy regarding company cooperation and the identification of culpable individuals in corporate cases—a revision of 2015’s so-called “Yates memo” policies.[4] Though the DOJ is still focused on prosecuting responsible individuals in corporate cases, the revisions suggest it will limit its scarce enforcement resources to pursuing key individuals, rather than every employee whose “routine activities . . . were part of an illegal scheme.” Therefore, to qualify for maximum cooperation credit, companies are instructed to focus on providing information about every individual who had substantial culpable involvement in the relevant conduct, rather than seeking to identify every single individual who was even remotely involved in the alleged conduct. Additionally, the revised policy restores discretion to DOJ attorneys to grant releases for individuals in corporate settlements where the DOJ is unlikely to pursue separate enforcement actions against those individuals.

In light of these developments, it is interesting that the average recovery per settlement in 2018 ($15 million) nevertheless exceeded the averages in 2017 ($13 million) and 2016 ($9 million). The three largest recoveries from 2018 are on par with, or greater than, the top recoveries for FCA settlements of health care providers in recent years. In fact, this year’s top three recoveries—$270 million,[5] $216 million,[6] and $84 million[7]—are significantly higher than those in 2017 ($155 million, $118 million, and $75 million), and are roughly in line with those from 2016 ($368 million, $145 million, and $125 million). This may demonstrate that even if providers have been somewhat successful in pushing back against FCA actions, enforcement actions against providers remain a cornerstone of the DOJ’s FCA enforcement efforts.

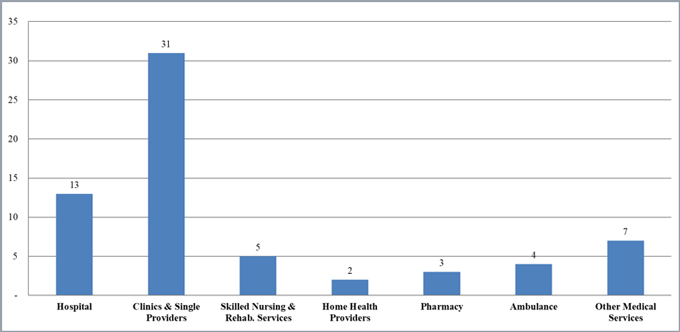

Number of FCA Settlements with Providers, by Provider Type

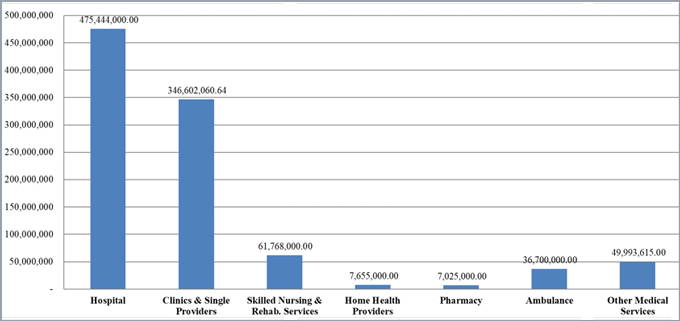

FCA settlements announced in 2018 spanned a variety of legal theories and provider types, including hospitals (13 total), clinics and single providers (31 total), skilled nursing and rehabilitation services (5 total), ambulance services (4 total), pharmacies (3 total), and home health providers (2 total). The “Other” medical services group (7 total) included providers such as an autism therapy services provider, intra-operative monitoring services, diagnostic laboratory testing, and wound care. As in prior years, clinics and single providers comprised the bulk of settlements by count, but did not represent the most significant settlements by dollar amount. Rather, as illustrated by the chart below, the sum from the 13 settlements with hospitals amounted to over $475 million (on average, $36 million per case), whereas the total from the 31 settlements with clinics and single providers amounted to only about $347 million (on average, $11 million per case).

FCA Settlement Totals with Providers, by Provider Type

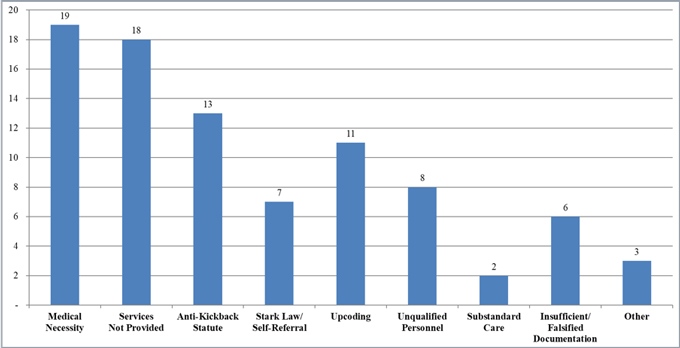

In 2018, as in prior years, the most prevalent legal theory among health care provider settlements was that the provider had billed government health programs for items or services that were not medically necessary (19 claims). This is illustrated in the below table. For many of these cases, medical necessity was the sole underlying theory of liability (13 cases), but in at least 6 cases, the DOJ presented alternative theories of liability, including claims the provider had submitted insufficient or falsified documentation.[8]

Number of FCA Settlements with Providers, by Allegation Type

Of note, claims alleging providers billed federal health programs for services that were not provided increased significantly from 2017. By year-end 2018, there were at least 18 such claims, representing about 21% of the roughly 87 claims.[9] In 2017, by contrast, only about 15 of the 110 claims (14%) alleged providers had billed for services not provided.[10] In one case out of the District of South Carolina, the DOJ settled with an autism therapy services company for $8.8 million based on allegations the provider had billed federal and state government health programs for services that were not actually provided, or misrepresented the services actually provided.[11] In addition, the DOJ settled with five Maryland medical practices and providers for services not provided, alleging that each of the providers billed for an additional test that was not actually performed.[12]

In 2018, the DOJ also settled a number of claims based on the AKS (13 claims), upcoding (11 claims), unqualified personnel providing care (8 claims), physician self-referral (7 claims), claims of insufficient/falsified documentation (6 claims), and substandard care (2 claims). Notably, three of the top five settlements from 2018 involved allegations of upcoding, and many cases with claims of upcoding included additional theories of liability. For example, in one case out of the Central District of California, the DOJ settled with a national Medical Services Organization (“MSO”) for $270 million based on allegations that the MSO had engaged in a variety of practices, including disseminating improper medical coding guidance, that yielded artificially increased CMS reimbursements.[13] The settlement also resolved whistleblower allegations that the provider had engaged in “one-way” chart reviews, in which the provider scoured its patients’ medical records to find additional diagnoses to enable managed care plans to obtain added revenue from the Medicare program, but ignored inaccurate diagnosis codes revealed by these reviews that, if deleted, would have decreased Medicare reimbursement or required the pans to repay money to Medicare.[14]

The DOJ also continues to prioritize the investigation and settlement of AKS claims, with roughly 13 claims settled by the DOJ against health care providers this year. Many of the cases involving AKS claims also allege claims of physician self-referral and/or improper billing. For example, in August 2018, a regional hospital system based Detroit, Michigan, paid $84.5 million to resolve such allegations; this settlement is discussed further in Section III, below.

B. FCA-Related Case Law Developments

1. Developments in Implied False Certification Theory

Even as the number of appellate courts interpreting the Supreme Court’s 2016 decision in Universal Health Services, Inc. v. United States ex rel. Escobar[15] proliferate, lower courts continue to grapple with the standards for materiality and scienter under the implied false certification theory. As we discussed in our 2018 Mid-Year Update, 2018 saw a growing circuit split regarding the extent to which the government’s continued payment to a defendant after gaining awareness of alleged non-compliance negates FCA materiality. The First, Second, and Third Circuits have previously found that the government’s failure to take action against the defendant despite knowledge of the alleged regulatory violations was conclusive proof that those violations were not material to payment,[16] while the Ninth Circuit has found that continued payment does not render alleged violations immaterial as a matter of law.[17]

In January 2018, the Middle District of Florida overturned a $350 million jury verdict on the grounds that the evidence did not support a finding of FCA materiality and scienter where the government continued making payments to the defendants despite being on notice of defendants’ alleged billing violations.[18] In July 2018, the DOJ filed an amicus brief in support of the appeal pending before the Eleventh Circuit, arguing that the government’s failure to recoup payments or take enforcement actions after learning of a provider’s non-compliance does not bar recovery under the FCA, and that under Escobar, the court’s focus should be on what action the government might have taken if violations were known prior to payment being made.[19] The DOJ argued that under Escobar, “the materiality inquiry is meant to shed light on the government’s decision-making at the time of the relevant transaction—not at some later date after the transaction is over.”[20]

In January 2019, the Supreme Court denied the petition for certiorari in United States ex rel. Campie v. Gilead Sciences, Inc., leaving in place the Ninth Circuit’s holding in favor of relators with respect to materiality.[21] The decision came after the DOJ filed an amicus brief recommending that the petition be denied and stating that the DOJ would move to dismiss the case if it was sent back to the district court in accordance with the Ninth Circuit’s ruling.[22] Of note, the DOJ agreed with the Ninth Circuit’s ruling that Plaintiffs had sufficiently pleaded materiality under Escobar; however, it argued that the case would be a poor vehicle for considering the question presented, because it is unclear what the government knew and when.[23]

A petition for certiorari seeking review of the Sixth Circuit’s decision reinstating a qui tam claim in Brookdale Senior Living Communities, Inc. v. U.S. ex rel. Prather is also pending before the Supreme Court.[24] In Brookdale, the relator alleged that the Defendant had violated Medicare regulations by failing to obtain physician signatures on home health certifications as soon as possible after the physician established a plan of care and submitted those services for payment.[25] The district court dismissed the case for failure to plead sufficiently the elements of materiality.[26] On appeal, the Sixth Circuit reversed, holding that the relator’s failure to plead facts related to the government’s past payment practices did not affect the materiality analysis at the pleading stage.[27] In its petition for certiorari, the Defendant argues that the materiality element requires the plaintiff to show that the government refused payment on the basis of similar violations in the past and that the scienter element requires the defendant to possess knowledge that the alleged violation was material to the government’s payment decision.[28] We will continue to monitor these cases and report back in a future update.

2. Developments in FCA Statute of Limitations Provisions

In a seemingly technical aspect of FCA law that will nonetheless have a substantial impact on FCA litigation against providers, on November 16, the Supreme Court took up review of a circuit split regarding the proper application of the FCA’s statute-of-limitations tolling provision, 31 USC § 3731(b)(2), to relators in cases where the government has not intervened. Section 3731(b) requires that an FCA case be filed either (1) six years after the date on which the violation is committed, or (2) three years after the date when facts material to the right of action are known or reasonably should have been known by the official of the United States charged with responsibility to act in the circumstances, but in no event more than 10 years after the date on which the violation is committed.[29] The Court granted Gibson Dunn’s petition for cert to review the Eleventh Circuit’s decision in United States ex rel. Hunt v. Cochise Consultancy, Inc.,[30] which held (i) that the longer limitations period in section 3731(b)(2) was available to qui tam relators even if the government declined to intervene in the case, and (ii) that the three-year limitations period began when the government—not the relator—had actual or constructive knowledge of the fraud allegations. Previously, the Third and Ninth Circuits had held that the section 3731(b)(2) limitations period is available to qui tam relators in the absence of government intervention, but it ran from the time of the relator’s knowledge in those circumstances.[31] In contrast, the Fourth and Tenth Circuits had held that section 3731(b)(2) is available only if the government intervenes, not in a case a relator handles alone after declination.[32] The Supreme Court’s ruling will hopefully resolve this three-way divide and provide clarity for future application of the FCA’s statute of limitations provisions, which in turn could have a material effect on the number of qui tam cases brought by relators.

C. Affordable Care Act Developments

Nearly nine years after its passage, the Affordable Care Act continues to be tested in the court system. In December 2018, a Texas federal judge struck down the entire Affordable Care Act, finding that the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate provision will no longer be a valid exercise of congressional taxing power when the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 eliminates the mandate’s tax penalty in 2019.[33] U.S. District Judge Reed O’Connor held that the Supreme Court’s reasoning in National Federation of Independent Businesses v. Sebelius[34] “compels the conclusion that the Individual Mandate may no longer be upheld under the Tax Power. And because the Individual Mandate continues to mandate the purchase of health insurance, it remains unsustainable under the Interstate Commerce Clause.”[35] Judge O’Connor held that the remaining provisions of the ACA are “inseverable” from the individual mandate and are therefore invalid.[36] The underlying case was brought by a coalition of Republican attorneys general from twenty states. Democrat attorneys general for sixteen states and the District of Columbia, who intervened as defendants in the Texas case, filed a notice of appeal to the Fifth Circuit.[37] The Affordable Care Act remains in effect pending the appeals process.[38] If both aspects of the ruling are upheld, the decision would have a wide-ranging impact on health care regulatory provisions far beyond the individual mandate and insurance exchanges, such as on the ACA’s provisions relating to drug approvals and prices, consumer protections, Medicare reimbursement, Anti-Kickback Statute amendments, and other critical regulatory and enforcement issues.

In contrast, in September 2018, Maryland filed a complaint seeking a declaratory judgment that the Affordable Care Act is constitutional and enforceable.[39] In its complaint, Maryland argued that the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate will not become unconstitutional when its tax penalty disappears, such that no portion of the Affordable Care Act need be struck down.[40] Just this month, the District of Maryland issued a memorandum opinion denying the request for declaratory judgment and dismissing the case without prejudice due to lack of standing.[41] The Court found that Maryland had failed to show a “concrete and particularized injury” because its allegations did not demonstrate a real threat that the Trump administration would cease enforcement of the ACA; however, it explicitly invited Maryland to revive the suit if the injury alleged becomes more concrete. We will watch these cases as they progress through the federal courts, and report on continuing developments in our 2019 mid-year update.

D. Opioid Crisis Enforcement Efforts

The DOJ has continued its assault on the nation’s opioid crisis through, among other means, a broad-based use of criminal prosecutions and civil enforcement actions against a wide variety of targets in the distribution chain. In August 2018, the DOJ issued the first-ever civil injunctions under the Controlled Substances Act against doctors who allegedly prescribed opioids illegally.[42] The DOJ filed complaints against two Ohio doctors and obtained temporary restraining orders barring them from writing prescriptions after an investigation led to allegations that the doctors had recklessly and unnecessarily prescribed opioids and other drugs, providing them to patients upon request.[43] Then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions described the announcement as a “warning to every trafficker, every crooked doctor or pharmacist, and every drug company.”[44]

The DOJ also sent a warning message to foreign synthetic opioid manufacturers when it unsealed a 43-count indictment against leaders of a Chinese fentanyl trafficking organization.[45] Two Chinese citizens were charged with operating a conspiracy to manufacture and ship deadly fentanyl analogues and 250 other drugs to at least 25 countries and 37 states.[46] The indictment alleged that the organization was responsible for the fatal overdoses of two people in Akron, Ohio.[47]

As we discussed in our 2018 Mid-Year Update, the DOJ previously launched Operation Synthetic Opioid Surge, or Operation S.O.S., to focus on prosecuting suppliers of synthetic opioids, rather than drug users. In a September statement at Office of Justice Programs’ National Institute of Justice Opioid Research Summit, then-Attorney General Sessions applauded the success of Operation S.O.S.[48] He credited the shift in focus from prosecuting users to suppliers with helping to reduce the amount of overdose deaths in Manatee County, Florida by half since last year.[49] In an effort to replicate those results elsewhere, then-Attorney General Sessions announced that the DOJ sent ten prosecutors to help implement the “no amount too small” strategy in ten districts with exceptionally high rates of drug-related deaths.[50] Sessions noted that this is in addition to the twelve prosecutors sent to drug “hot spot districts” and the more than 300 new prosecutors he dispatched around the country.[51]

Most recently, in October 2018, the DOJ announced an award of almost $320 million to a variety of entities and programs, including drug courts, research efforts, and programs aimed helping impacted children and youth, in an effort to combat the opioid crisis in America. The funds will be invested into all three parts of the Administration’s plan to end the opioid epidemic: prevention, treatment, and enforcement.[52] The funding is further evidence of the DOJ’s ongoing commitment to leveraging its resources against opioid-related health care fraud and crimes. We have no reason to expect this to change under the newly-confirmed Attorney General, William Barr.

II. HHS ENFORCEMENT ACTIVITY

A. HHS OIG Activity

1. 2018 Developments and Trends

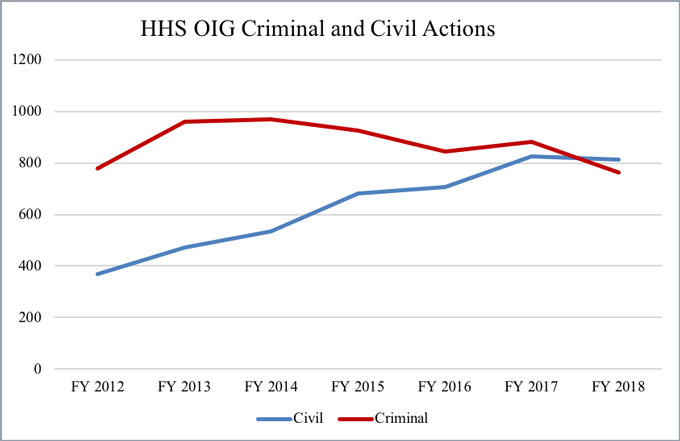

According to its Semiannual Report to Congress, HHS OIG will report approximately $3.43 billion in expected recoveries from its investigative and audit enforcement efforts in 2018.[53] As we predicted in our 2018 Mid-Year Update, recoveries are slightly down from the agency’s $4.13 billion in 2017 recoveries and $5.66 billion in 2016 recoveries.[54] Expected recoveries consist of audit receivables (representing amounts identified in HHS OIG audits that HHS officials have determined should not be charged to the government) and investigative receivables (consisting of expected criminal penalties, civil or administrative judgments, or settlements that have been ordered or agreed upon).[55] HHS OIG’s drop in recoveries was partly driven by the decrease in investigative receivables from $4.13 billion in Fiscal Year 2017 to $2.91 billion in Fiscal Year 2018.[56]

For Fiscal Year 2018, HHS OIG reported 764 open criminal actions and 813 open civil actions, including FCA suits, civil monetary penalty (“CMP”) settlements, and administrative recoveries, against individuals or entities.[57] Both figures indicate a decrease on the criminal side as compared to Fiscal Year 2017, where HHS OIG reported 881 criminal actions and 826 civil actions.[58] This reflects a drop of over 13% in the number of criminal actions, and, as noted in the 2018 Mid-Year Update, the slight decrease in the number of civil actions breaks a years-long steady rise in civil actions. Additionally, this is the first time in recent years we have seen civil enforcement actions surpass criminal enforcement actions.

2. Proposed and Final Rules

Despite assertions by the current administration that agency rulemaking would be curtailed, throughout the last fiscal year, CMS and HHS OIG finalized multiple rules and proposed many more.[59]

In August 2018, CMS finalized the inpatient and long-term care hospital prospective payment system (IPPS/LTCH PPS) rule, which contained new requirements mandating that hospitals publicize a list of their standard changes online in a machine-readable format by January 1, 2019.[60] The rule also states that hospitals must update their list of prices at least annually. CMS explained its reasoning for the new requirement as stemming from its “concern[] that challenges continue to exist for patients due to insufficient price transparency, including patients being surprised by out-of-network bills for physicians, such as anesthesiologists and radiologists, who provide services at in-network hospitals, and by facility fees and physician fees for emergency room visits.”[61]

Additionally, in November 2018, CMS published its final rule updating the Physician Fee Schedule. While this rulemaking is generally standard, notable in this year’s rule is that, starting in 2019, CMS will be reimbursing doctors for virtual check-ins, remote image evaluation, and other technology-enabled services that have begun to proliferate in recent years.[62]

3. Notable Reports and Reviews

In this year’s report on the Top Management and Performance Challenges, HHS OIG identified twelve key challenges it is currently facing in the enforcement space.[63] The number one challenge, consistent with DOJ and other agency enforcement efforts, is preventing and treating opioid misuse. HHS OIG noted that as an agency, it has “many opportunities” to address the issue and listed some of the ways in which it has addressed the challenge.[64] For example, HHS OIG highlighted efforts by CMS to provide guidance in combating the opioid crisis by identifying substance use disorders covered by Medicaid, as well as the “more than 160 defendants [] charged with participating in Medicare and Medicaid fraud schemes related to opioids or treatment for opioid use disorders.”[65]

Among its other top challenges, HHS OIG includes more general goals such as “ensuring program integrity,” “protecting the health and safety of vulnerable populations,” and “improving financial and administrative management and reducing improper payments.”[66]

4. Significant HHS OIG Enforcement Activity

a) Exclusions

HHS OIG is permitted in some cases and required in others to exclude entities and individuals from participation in federal health care programs,[67] a powerful tool and potential collateral consequence that looms over other civil and criminal enforcement proceedings. After record-setting exclusion figures for 2014 and 2015, HHS OIG reported a decline in exclusions in 2016 and again in 2017. In 2018, that trend continued, with 2,712 entities and individuals excluded this year, in comparison to 3,244 entities and individuals excluded in 2017.[68]

These exclusions involve 59 entities – matching 2017’s total – with pharmacies accounting for 17 exclusions, up from 12 exclusions in 2017.[69] While mental health facilities and home health agencies accounted for the next most frequent entity exclusions in 2017, these were not commonly excluded entities in 2018; after pharmacies, the next most commonly excluded entity was community mental health centers (12 exclusions) followed by clinics (4 exclusions). [70] Among excluded individuals, 270 were identified as business owners or executives, down from last year’s high of 348 business owners or executives.[71] This year, nearly half of all excluded individuals – 42% – were identified as nurse practitioners, nurses, or nurse’s aides working as non-business owner licensed health care service providers.

b) Civil Monetary Penalties

In the 2018 calendar year, HHS OIG announced 135 civil monetary penalties (“CMPs”) resulting from settlement agreements and self-disclosures that recovered approximately $71.07 million.[72] As we predicted in our 2018 Mid-Year Update, these recoveries represent a significant increase in comparison to last year’s recoveries of $36.5 million over 95 CMPs.[73] In line with past years, false or fraudulent billing continues to be a leading reason for assessment of CMPs, accounting for 58 CMPs (43% of the total number), and about $44.8 million, or 63%, of total recoveries assessed in 2018. As in past years, HHS OIG also routinely pursued CMPs in which entities employed individuals that the entities allegedly knew or should have known were excluded from federal health care programs. These cases account for 47 of the CMPs assessed this year, amounting to about $6.0 million in penalties. Some of the largest penalties this year came from violations of AKS and Stark Law physician self-referral prohibitions. The 17 penalties in AKS and Stark cases amounted to approximately $15.6 million together. Penalties also were assessed for violations of the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (“EMTALA”) and other issues.

The largest penalties in 2018, as in 2017 and 2016, have stemmed from self-disclosure cases. HHS OIG’s self-disclosure protocol provides for reduced penalties as an incentive, so this may be an indication that these cases would have had even larger repayment amounts had they not been self-disclosed. Each of the top ten largest penalties in 2018 resulted from self-disclosure to HHS OIG. Most of the larger penalties came during the first half of the year and are summarized in our 2018 Mid-Year Update; the largest CMPs assessed during the second half of this year are summarized below:[74]

- On September 13, 2018, after self-disclosing conduct, a hospital in Manhattan, Kansas agreed to pay approximately $3.8 million to resolve allegations that it submitted claims to federal health care programs for medically unnecessary bronchoscopies that lacked medical documentation.

- After it self-disclosed conduct to HHS OIG, on October 23, 2018, a hospital in Columbus, Georgia agreed to pay approximately $3.3 million to resolve allegations that it had paid remuneration to a management company in the form of incentive payments for performance metrics that were not met and were not materially updated to incentivize performance. HHS OIG further contended that the hospital paid remuneration to a cardiology practice in the form of a forgiven or uncollected debt owed as a result of the practice exceeding the tenant improvement allowances of their lease agreement.

- A general hospital in Raleigh, North Carolina agreed to pay approximately $2.3 million on September 24, 2018 after it disclosed that it leased an employed physician from a community hospital for the provision of cardiology services at the community hospital. HHS OIG contended that during this time the community hospital paid the general hospital a fee for the lease of the physician, and the general hospital paid the physician salary and bonus payments for the cardiology services performed by the physician at the community hospital. HHS OIG alleged that the general hospital offered and paid remuneration in the form of salary and bonus payments to the physician that were in excess of the community hospital’s lease fee to the general hospital and that should have been paid by the community hospital.

c) Corporate Integrity Agreements

HHS OIG continues to employ CIAs as a mechanism to resolve enforcement actions and create assurances that the provider will comply with Medicare and Medicaid rules and regulations. In Fiscal Year 2018, 31 CIAs took effect, a decline from last year’s 51 CIAs.[75] CIAs are often linked with other enforcement penalties, particularly FCA and AKS settlements with the DOJ, because HHS OIG often agrees to waive its permissive exclusion authority—which can be triggered by FCA claims—in exchange for the defendant’s acceptance of prospective integrity obligations.

In the largest health care FCA settlement of 2018, a wholesale pharmaceutical company paid $625 million to resolve allegations arising from its operation of a facility that improperly repackaged oncology-supportive injectable drugs into pre-filled syringes and improperly distributed those syringes to physicians treating cancer patients.[76] This settlement surpasses last year’s largest payment of $465 million.[77] The company had also agreed to pay $260 million in criminal fines and forfeiture for this conduct last year, bringing the total penalties it has paid to resolve liability to $885 million.[78] As part of its settlement, the company entered into a five-year CIA.[79] Though the company had already established a compliance program, the CIA requires the company to re-commit to and expand its compliance program.[80] The CIA requires that the company put in place an incentive compensation restriction plan to fine senior management that have violated company policies and, notably, mandates extensive certification of compliance with Drug Enforcement Agency (“DEA”) requirements.[81] According to the terms of the CIA, the Chief Compliance Officer must report directly to the audit committee of the board of directors.[82]

In the latter half of 2018, multiple settlements with CIAs resolved allegations of kickbacks and improper physician relationships, continuing the recent strong focus on AKS and Stark Law enforcement. For example, a Pennsylvania-based operator of long‑term care and rehabilitation hospitals across the country agreed to pay $13.2 million to resolve allegations that it used contracts with physicians to induce them to refer patients to its hospitals.[83] The company also entered into a five-year CIA as part of the agreement, which requires, among other things, that the company appoint a Compliance Officer who “shall not be . . . subordinate to the General Counsel or Chief Financial Officer or have any responsibilities that involve acting in any capacity as legal counsel.”[84] The company is also required to track all remuneration and document all fair market value determinations for arrangements that could potentially implicate AKS.[85] Similarly, a Philadelphia-based group of vascular centers entered into a CIA and a minimum $3.8 million settlement to resolve allegations that it submitted false claims to Medicare for services that resulted from referrals that the group had induced through improper remuneration to physician investors and medical directors.[86] The CIA requires the company to “engage in significant compliance efforts over the next five years, including a focus on [the company’s] arrangements with physicians and other health care providers for compliance with [AKS.]”[87]

As described in the 2018 Mid-Year Update, a wider variety of entities are being subjected to CIAs. In the second half of 2018, for example, CIAs were imposed upon multiple hospital systems. In a matter that concluded in both a civil recovery and criminal plea, a former hospital chain paid over $216 million to resolve civil allegations that it billed government health care programs for more-costly inpatient services that should have been billed as observation or out-patient services, paid illegal remuneration to physicians in return for patient referrals to its hospitals, and inflated claims for emergency department facility fees.[88] In addition to these civil recoveries, the hospital chain’s subsidiary pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy to commit health care fraud arising from illegal conduct designed to aggressively increase admissions to the hospital and paid a $35 million monetary penalty.[89]

B. Significant CMS Activity

1. Transparency and Data Accessibility

CMS released an eighth update of the Market Saturation and Utilization Tool[90]—the second update of this data tool in 2018 after an update was released in April, as described in our 2018 Mid-Year Update.[91] This tool provides interactive maps and related data sets showing provider services and utilization data for selected health services, and is one of many tools used by CMS to monitor and manage market saturation as a means to help prevent potential fraud, waste, and abuse. The updated tool includes a quarterly update of the data regarding the twelve health services areas from the previous release, and also includes Cardiac Rehabilitation Programs and Psychotherapy data.

2. Continued Implementation of Moratoria

As explained in past updates, the Affordable Care Act authorizes CMS to impose moratoria on certain regions, preventing new provider enrollments in certain geographic areas deemed as “hot spots” for fraud. The moratoria are imposed after consultation with the DOJ and HHS OIG and reviewed for continued necessity every six months. The moratoria, which block any new provider enrollments for nonemergency ambulance services in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Texas, and for home health agencies in Florida, Texas, Illinois, and Michigan, were reviewed and extended again for a six month period on August 2, 2018.[92]

C. OCR and HIPAA Enforcement

As cybersecurity and data privacy issues have increasingly appeared as headline news and become cutting edge areas of the law, so too has HHS increasingly focused on enforcement of patient information protections under the Health Information Portability and Accountability Act (“HIPAA”). HHS’s Office of Civil Rights (“OCR”) reported that as of January 31, 2019, it had reviewed and resolved 194,951 HIPAA complaints since HIPAA privacy rules went into effect in April 2003.[93] In 2018, OCR reported ten settlements or rulings amounting to approximately $25.7 million in fines for HIPAA violations.[94] This year marks the highest total recoveries from HIPAA settlements and rulings, surpassing 2016’s $23.5 million then-record total.

This year’s record HIPAA enforcement haul was driven in large part by the largest HIPAA settlement in history—a fine of $16 million paid by a national health insurance company after a series of cyberattacks led to the largest-ever health data breach and exposed the electronic protected health information of almost 79 million people.[95] In addition, this year an Administrative Law Judge ruled that a comprehensive cancer center in Texas violated HIPAA and granted summary judgment to OCR on all issues, requiring the center to pay $4.3 million in penalties.[96]

1. Developments in HIPAA Compliance Guidance

Protection of patients’ confidential information, and electronically stored information in particular, continues to be a high priority for HHS enforcement, just as cybersecurity and data privacy issues explode in complexity and public attention. As discussed in past updates, OCR continues to issue regular Cybersecurity Newsletters to provide guidance on the specific security measures providers can take to decrease exposure to various security threats and vulnerabilities that exist in the health care sector, and how to reduce breaches of electronic-protected health information (“ePHI”). HHS has not said that following the measures outlined in these newsletters creates any kind of safe harbor; rather, the newsletters are designed to “assist” the regulated community to become more knowledgeable about risk areas. Brief summaries of the newsletters that have been issued in the second half of this year are below; for those issued in the first half of the year, see the 2018 Mid-Year Update.

- The July newsletter discusses the importance of disposing of electronic devices in a secure manner, since improper disposal of these devices and media puts the information stored on these items, which may be ePHI, at risk of a potential breach.[97] The newsletter reminds readers that HIPAA-covered entities and business associates are required to implement policies and procedures regarding the disposal and re-use of hardware and electronic media containing ePHI.

- The August 2018 newsletter reviews considerations for securing electronic media and devices in order to reduce the risk of loss and theft of these items containing ePHI.[98] The importance of training, inventory, and records of movement is emphasized.

- The final Cybersecurity Newsletter of 2018, released in October, uses National Cybersecurity Awareness Month to review cybersecurity safeguards, including encryption, social engineering, audit logs, and secure configurations.[99]

III. ANTI-KICKBACK STATUTE DEVELOPMENTS

As evidenced by the enforcement decisions summarized above, the AKS remains a primary theory for actions against health care providers, and case law developments in the second half of 2018 continue to impact the risk environment for providers. At the same time, renewed attention has been paid to the ways in which the AKS prevents the adoption of a value-based care approach. We discuss important AKS-related regulatory and case developments below.

A. AKS-Related Case Law

Similar to the first half of 2018, the second half of 2018 was relatively quiet with respect to AKS case law. However, there were a few cases of note, including additional guidance interpreting materiality under Escobar.

The AKS prohibits an individual from knowingly or willingly offering, soliciting or receiving “remuneration” in exchange for referrals of health care items or services reimbursable by federal health care programs.[100] Courts have interpreted the word “remuneration” broadly to include anything of value. This trend of broad interpretation continued in State v. MedImmune, Inc.[101] In that case, the District Court for the Southern District of New York held that the State of New York adequately pled that “the sharing of [personal health information] with specialty pharmacies could plausibly constitute ‘remuneration’ in violation of the federal anti-kickback statute.”[102] The State had sued MedImmune under the New York False Claims Act based on purported AKS violations, alleging that MedImmune sales personnel would “curry favor” with hospital administrators in exchange for access to confidential personal health information, MedImmune allegedly would pass on to a specialized pharmacy to use in identifying prime candidates for MedImmune’s neonatal respiratory drug.[103] The ruling joins the growing number of district courts taking a broad approach to the definition of “remuneration” under the AKS at the motion to dismiss stage.

In Carrel v. AIDS Healthcare Foundation, Inc.,[104] the Eleventh Circuit held that a nonprofit health care organization can pay a bonus to its employees for referring patients to the organization without violating the AKS. The relators claimed that the $100 bonuses that the AIDS Healthcare Foundation paid to its employees for patients who completed follow-up procedures at the Foundation constituted kickbacks. Affirming a ruling by the Southern District of Florida, the court determined that the referral bonus fell within the AKS’s employee safe harbor provision, which protects from AKS enforcement payments from employers to employees in a bona fide employment relationship for items or services payable by federal health care programs.[105] In its decision, the court noted that the Ryan White Act establishes the referral of patients as a “standalone compensable ‘service’” that is thus covered by the safe harbor’s exemption for payments to employees “in the provision of covered items or services.”[106] Of note, the DOJ filed a statement of interest in support of the Foundation’s motion to dismiss, maintaining that the Foundation had correctly interpreted the law regarding the safe harbor.[107]

In United States ex rel. Capshaw v. White,[108] the court denied the defendant’s motion to dismiss the government’s AKS and FCA claims on materiality grounds, holding that AKS violations are “inherently material” to government payment.[109] At issue were allegations that the defendants, a physician and nurse who owned a small number of hospice companies, gave remuneration to a home health care company that was struggling financially in exchange for Medicare referrals. The Northern District of Texas court in White found that the government sufficiently alleged that the defendants violated the AKS through these payments.[110] In coming to its conclusion, the court cited several reasons. First, AKS violations in general are not “insubstantial regulatory violation[s]” but rather are “serious, consequential felon[ies]” that carry the possibility of prison terms.[111] Next, the court noted that the language of the AKS expressly provided that a claim that results from a violation of the AKS “constitutes a false or fraudulent claim.”[112] Third, AKS compliance is a condition of payment under Medicare Part D provider agreements (and under many state Medicaid provider applications).[113] Based on this reasoning, the court rejected the defendants’ argument that AKS violations are similar to “garden-variety breaches of contract or regulatory violations.”[114] The court concluded that the principles of materiality espoused in Escobar did not apply to the AKS.[115]

B. Regulatory Developments

In August, HHS OIG issued a request for information (“RFI”) to identify ways in which it might modify or add new safe harbors to the AKS and exceptions to the beneficiary inducement provisions of the CMP statute in order to promote care coordination and value-based care initiatives. The RFI, which is part of HHS OIG’s “Regulatory Sprint to Coordinated Care,” seeks input on regulations that “may act as barriers to coordinated care” or “value-based care.”[116]

In its solicitation, HHS OIG identified several categories of particular interest and requested comments that address the following:

- alternative payment models, arrangements involving innovative technology, or other novel financial arrangements that the industry is interested in pursuing;

- incentives that industry is interested in providing to beneficiaries to promote care coordination and engagement, or proposals for reduction or elimination of beneficiary cost-sharing obligations;

- other topics, including current fraud and abuse waivers developed for testing models under the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, donations for cybersecurity-related items, the Accountable Care Organization Beneficiary Incentive Program, and telehealth technologies; and

- whether there should be alignment between Stark law exceptions and the AKS safe harbors.

In the RFI, HHS OIG stated that it seeks to add new safe harbors in order to promote coordination of care and increase value-based care, while continuing to protect against fraud and abuse.[117] The comment period closed on October 26, 2018; additional guidance has not been issued.

C. Notable HHS OIG Advisory Opinions

During the second half of 2018, HHS OIG issued several AKS advisory opinions that provide useful guidance for health care providers.

On July 18, HHS OIG evaluated a proposal by the offeror of Medicare Supplemental Health Insurance (“Medigap”) policies to enter into a preferred network arrangement with hospitals under which it would receive discounts on Medicare inpatient deductibles for its policyholders.[118] The plan would then provide a credit of $100 to policyholders who used an in-network hospital for their inpatient stay. HHS OIG determined that the arrangement neither met the requirements for protection under the safe harbor for waivers of beneficiary coinsurance and deductible amounts, nor the safe harbor for reduced premium amounts offered by health care plans.[119] However, despite the lack of safe harbor protection, HHS OIG concluded that the proposal presented a low risk under the AKS, reasoning that the arrangement (i) would not impact per-service Medicare payments, (ii) was unlikely to prompt overutilization, (iii) would not unfairly affect competition among hospitals, (iv) was unlikely to impact clinical decision-making by providers, and (v) would operate transparently.[120] On August 21 and October 29, HHS OIG approved two substantially similar arrangements involving Medigap policies under the same reasoning as set forth above.[121]

On August 6, 2018, HHS OIG evaluated a proposal by a Group Purchasing Organization (“GPO”) to serve as the purchase agent for health care facilities that share a common parent organization with the GPO, referred to as “Affiliated Facilities.”[122] The services the GPO provides for its current members extend beyond typical products and services to include negotiating discounts for IT platforms, emergency department staffing, physician recruitment, and telemedicine consults.[123] Although HHS OIG concluded that the arrangement did not meet the GPO safe harbor, it concluded that the arrangement “would not materially increase the risk of fraud and abuse” under the AKS, reasoning that the majority of the GPO’s members would still be unrelated to the GPO and distinguishing the arrangement from suspect arrangements under which a wholly-owned subsidiary under a single corporate entity is essentially seeking referral fees.[124] HHS OIG also noted that the larger volume might increase the GPO’s ability to obtain lower prices on goods and services.[125]

In an advisory opinion issued on October 11, HHS OIG evaluated a health plan’s “proposal to pay providers and clinics to increase the amount of Early Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment services” that they provide to Medicaid beneficiaries, finding that the proposed arrangement satisfied the safe harbor for eligible managed care organizations.[126] In its opinion, HHS OIG explained that the safe harbor is satisfied because the plan is an eligible managed care organization, has an appropriate agreement to provide services, and the arrangement could help achieve the goal of increasing early diagnosis and treatment of health problems.[127]

On November 13, HHS OIG found that a manufacturer’s proposal to provide free doses of its drug to hospitals to treat inpatients could constitute improper remuneration under the AKS.[128] The company proposed to stock the drug at participating hospitals on a consignment basis, under which physicians seeking to prescribe the drug would submit a referral to the drug’s reimbursement hub and initiate therapy using the free vial.[129] The reimbursement hub would provide additional free vials if needed for inpatient use and would provide the same for outpatients unable to secure insurance coverage for the drug.[130]

Considering publicly available information outside of the materials submitted by the drug company, HHS OIG offered several reasons for its negative opinion. HHS OIG’s reasons included: (i) the proposed arrangement “would relieve a hospital of a significant financial obligation that [it] otherwise would incur” in light of the “substantial price increases” for the drug in recent years; (ii) the savings to the hospital would not be passed on to the government, since the drug is not separately reimbursable in the inpatient setting; (iii) the proposal “could function as a seeding arrangement” because insurers, including federal health care programs, may end up paying for the drug when insured patients need to finish the treatment on an outpatient basis, and because providing the free drug to inpatients “facilitates [the] high price for the Drug’s other indications”; (iv) it “could result in steering or unfair competition” by encouraging hospitals to “influence prescribers to consider the Drug as a first option”; and (v) two of the barriers cited by the drug company (delayed access to the product and unwillingness to bear excess inventory risks) could be eliminated by stocking the drug on consignment basis without also providing the drug for free. Significantly, HHS OIG also rejected the idea that the free vials would not be contingent on future purchases, explaining that patients would need to continue treatment with the drug as outpatients to avoid adverse medical consequences from halting the treatment they began for free on an inpatient basis.[131]

IV. STARK LAW DEVELOPMENTS

The physician self-referral law, or Stark Law, imposes strict liability on any physician who makes referrals for certain health services to an entity with which the physician or his or her immediate family member has a “financial relationship,” or bills the government for any such referred services. The Stark Law was enacted in an effort to “disconnect a physician’s health care decision making from his or her financial interests in other health care providers,” with the ultimate goal of ensuring that patients were presented with the best value and quality options. In the time since the bill’s passage in 1989, industry stakeholders have realized that the Stark Law’s broad conception of a “financial relationship” and narrow, enumerated exceptions has the undesired effect of limiting innovative, high-value, cost-effective health care arrangements. As discussed in our previous alerts, Stark Law reform is a common topic, and is receiving new attention under the Trump Administration. CMS Administrator Seema Verma promised action on Stark Law reform and announced she hoped to issue proposed regulations loosening physician self-referral regulations by the end of 2018. While proposed regulations are not yet available, regulatory and legislative developments indicate that reform may be on the horizon.

A. Regulatory and Legislative Updates

As part of HHS’s “Regulatory Sprint” to improve coordinated care by identifying and eliminating regulatory obstacles, CMS published an RFI in June 2018 seeking “input from the public on how to address any undue regulatory impact and burden of the physical self-referral law.”[132] To aid in assessment of existing obstacles, CMS invited broad comments on the Stark Law and its impacts and burdens, including feedback on the following:

- Existing or potential arrangements that involve designated health service (“DHS”) entities and referring physicians that participate in “alternative payment models or other novel financial arrangements,” regardless of whether such models and financial arrangements are sponsored by CMS;

- Exceptions to the Stark Law that would protect financial arrangements between DHS entities and referring physicians who participate in the same alternative payment model;

- Exceptions to the Stark Law that would protect financial arrangements that involve “integrating and coordinating care outside of an alternative payment model”; and

- Addressing the application of the Stark Law to financial arrangements among providers in “alternative payment models and other novel financial arrangements.”[133]

Over the course of the two-month comment period, 375 responses poured in from industry stakeholders.[134] CMS has not yet officially responded to the comments received, but a proposed regulation is anticipated sometime in 2019.

On the legislative front, President Trump’s budget for Fiscal Year 2019 specifically included a legislative proposal to establish a new Stark Law exception for referral arrangements arising from an alternative payment model.[135] In December, the Administration published a report entitled “Reforming America’s Healthcare System Through Choice and Competition,” calling for a widespread loosening of federal and state laws and regulations that impact the health care markets. Among the solutions proposed in the report was a recommendation to repeal restrictions on the opening and expansion of physician-owned hospitals, restrictions that had been put in place under the Affordable Care Act.[136]

B. Notable Stark Law Enforcement

The DOJ entered into two notable Stark Law settlements in the second half of 2018.

In August, a Detroit-area hospital system agreed to pay $84.5 million to settle federal and state allegations that it offered financial incentives to physicians in return for patient referrals.[137] As part of a CIA entered with HHS OIG, the hospital also agreed to a five-year independent outside review of its referral arrangements. The case arose from four different cases brought in 2010 and 2011, which alleged that the hospital provided free or below-fair-market-value office space to a group of physicians, to induce referrals.[138]

A health system serving patients in Illinois and parts of Wisconsin and Michigan agreed in December to pay $12 million to the United States and the State of Wisconsin to settle allegations that it violated the Stark Law by entering into unjustifiable compensation arrangements with two cardiologists.[139] The DOJ alleged that the health system offered the physicians a compensation package above fair market value that accounted for anticipated future referrals from those physicians.

V. CONCLUSION

We anticipate a variety of interesting and notable developments in 2019, as the DOJ and HHS continue to define their priorities and undertake enforcement actions. We look forward to updating you on the latest in our 2019 Mid-Year Alert. In the meantime, we welcome the opportunity to speak with you about these updates or any other related issues.

[1] See U.S. Dep’t of the Treasury, Reforming America’s Healthcare System Through Choice and Competition (Dec. 2018), https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/Reforming_Americas_Healthcare_System_Through_Choice_and_Competition.pdf [hereinafter “Reforming Healthcare Report”].

[2] Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Deputy Associate Attorney General Stephen Cox Delivers Remarks at the 2019 Advanced Forum on False Claims and Qui Tam Enforcement (Jan. 28, 2019), https://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/deputy-associate-attorney-general-stephen-cox-delivers-remarks-2019-advanced-forum-false.

[3] Id.

[4] See Rod J. Rosenstein, Deputy Att’y General, Remarks at the American Conference Institute’s 35th International Conference on the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (Nov. 29, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/deputy-attorney-general-rod-j-rosenstein-delivers-remarks-american-conference-institute-0.

[5] Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Medicare Advantage Provider to Pay $270 Million to Settle False Claims Act Liabilities (Oct. 1, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/medicare-advantage-provider-pay-270-million-settle-false-claims-act-liabilities.

[6] Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Hospital Chain Will Pay Over $260 Million to Resolve False Billing and Kickback Allegations; One Subsidiary Agrees to Plead Guilty (Sept. 25, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/hospital-chain-will-pay-over-260-million-resolve-false-billing-and-kickback-allegations-one [hereinafter “HMA Settlement”] (the hospital chain also agreed to pay $216 as part of a related civil settlement).

[7] Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Detroit Area Hospital System to Pay $84.5 Million to Settle False Claims Act Allegations Arising From Improper Payments to Referring Physicians” (Aug. 2, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/detroit-area-hospital-system-pay-845-million-settle-false-claims-act-allegations-arising.

[8] E.g., Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Banner Health Agrees to Pay Over $18 Million to Settle False Claims Act Allegations (Apr. 12, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/banner-health-agrees-pay-over-18-million-settle-false-claims-act-allegations; Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Signature HealthCARE to Pay More Than $30 Million to Resolve False Claims Act Allegations Related to Rehabilitation Therapy (June 8, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/signature-healthcare-pay-more-30-million-resolve-false-claims-act-allegations-related.

[9] Note that the number of claims is greater than the number of cases because many cases involve more than one theory of liability.

[10] The 2016 numbers (33 out of 146 claims, or 23%), are closer to those from this year.

[11] Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Early Autism Project, Inc., South Carolina’s Largest Provider of Behavioral Therapy for Children with Autism, Pays the United States $8.8 Million to Settle Allegations of Fraud (Aug. 2, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/usao-sc/pr/early-autism-project-inc-south-carolinas-largest-provider-behavioral-therapy-children.

[12] Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, United States Reaches Settlement With Maryland Healthcare Providers To Settle False Claims Allegations Relating To In Office Testing (Mar. 16, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/usao-md/pr/united-states-reaches-settlement-maryland-healthcare-providers-settle-false-claims-act.

[13] Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Medicare Advantage Provider to Pay $270 Million to Settle False Claims Act Liabilities (Oct. 1, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/medicare-advantage-provider-pay-270-million-settle-false-claims-act-liabilities.

[14] Id.

[15] 136 S. Ct. 1989 (2016).

[16] See United States ex rel. Nargol v. DePuy Orthopaedics, Inc, 865 F.3d 29 (1st Cir. 2017); Coyne v. Amgen, Inc, No. 17-1522-cv, 2017 WL 6459267 (2nd Cir. Dec. 18, 2017); United States ex rel. Petratos v. Genentech Inc., 855 F.3d 481 (3d Cir. 2017).

[17] See United States ex rel. Campie v. Gilead Sciences, Inc., 862 F.3d 890, 907 (9th Cir. 2017).

[18] United States ex rel. Ruckh v. Salus Rehabilitation, LLC, 304 F. Supp. 3d 1258 (M.D. Fla. 2018).

[19] See Brief for the United States of America as Amicus Curiae in Support of Appellant, Angela Ruckh v. Salus Rehabilitation, LLC, et al, No. 18-10500 (11th Cir. July 20, 2018).

[20] See id. at 19.

[21] See Pet. for a Writ of Cert., Gilead Sciences Inc. v. United States ex rel. Campie (filed Dec. 26, 2017).

[22] See Brief for the United States of America as Amicus Curiae, Gilead Sciences Inc. v. United States ex rel. Campie, No. 17-936 (Nov. 30, 2018).

[23] Id.

[24] See Pet. for a Writ of Cert., Brookdale Senior Living Communities, Inc. v. U.S. ex rel. Prather (filed Dec. 26, 2017).

[25] See United States ex rel. Prather v. Brookdale Senior Living Communities, Inc., 265 F. Supp. 3d 782, 787-90 (M.D. Tenn. 2017), rev’d and remanded sub nom. United States v. Brookdale Senior Living Communities, Inc., 892 F.3d 822 (6th Cir. 2018).

[26] See Brookdale Senior Living, 265 F. Supp. 3d at 801.

[27] See Brookdale Senior Living, 892 F.3d at 836.

[28] See Pet. for a Writ of Cert., Brookdale Senior Living Communities, Inc. v. U.S. ex rel. Prather (filed Nov. 20, 2018).

[29] 31 USC § 3731(b)(2).

[30] 887 F.3d 1081 (11th Cir. 2018). Gibson Dunn is handling this case.

[31] See United States ex rel. Malloy v. Telephonics Corp., 68 F. App’x 270 (3d Cir. 2003); United States ex rel. Hyatt v. Northrop Corp., 91 F.3d 1211 (9th Cir. 1996).

[32] See United States ex rel. Sanders v. N. Am. Bus Indus., Inc., 546 F.3d 288 (4th Cir. 2008); United States ex rel. Sikkenga v. Regence BlueCross BlueShield of Utah, 472 F.3d 702 (10th Cir. 2006).

[33] See Order Granting Plaintiffs Partial Summary Judgment, Texas et al. v. United States of America et al, No. 4:18-cv-00167-O (N.D. Tex. Dec. 14, 2018).

[34] 567 U.S. 519 (2012).

[35] Id. at 2.

[36] See id. at 55.

[37] See Intervenor-Defendants’ Notice of Appeal, Texas et al. v. United States of America et al., No. 4:18-cv-00167-O (filed Jan. 3, 2019).

[38] See Order Granting Stay and Partial Final Judgment, Texas et al. v. United States of America et al., No. 4:18-cv-00167-O (N.D. Tex. Dec. 30, 2018).

[39] See Complaint, Maryland v. U.S. et al., No. 1:18-cv-02849 (D. Md. 2018).

[40] Id.

[41] See Memorandum Opinion, Maryland v. U.S. et al., No. 1:18-cv-02849 (D. Md. Feb. 1, 2018).

[42] See Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, US Dep’t of Justice, Justice Department Takes First-of-its-Kind-Legal Action to Reduce Opioid Over-Prescription (Aug. 22, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-takes-first-its-kind-legal-action-reduce-opioid-over-prescription.

[43] Id.

[44] Id.

[45] See Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Two Chinese Nationals Charged with Operating Global Opioid and Drug Manufacturing Conspiracy Resulting in Deaths (Aug. 22, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/two-chinese-nationals-charged-operating-global-opioid-and-drug-manufacturing-conspiracy.

[46] Id.

[47] Id.

[48] See Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Attorney General Sessions Delivers Remarks at the Office of Justice Programs’ National Institute of Justice Opioid Research Summit (Sept. 25, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/attorney-general-sessions-delivers-remarks-office-justice-programs-national-institute.

[49] Id.

[50] Id.

[51] Id.

[52] See Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, US Dep’t of Justice, Justice Department is Awarding Almost $320 Million to Combat Opioid Crisis (Oct. 1, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-awarding-almost-320-million-combat-opioid-crisis.

[53] See U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of the Inspector Gen., Semiannual Report to Congress (Apr. 1 to Sept. 30, 2018), at 4, https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/archives/semiannual/2018/2018-fall-sar.pdf [hereinafter 2018 SA Report].

[54] See U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of the Inspector Gen., Semiannual Report to Congress (Apr. 1 to Sept. 30, 2017), at 4, https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/archives/semiannual/2017/sar-fall-2017.pdf [hereinafter 2017 SA Report]; U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of the Inspector Gen., Semiannual Report to Congress (Apr. 1 to Sept. 30, 2016), at iv, https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/archives/semiannual/2016/sar-fall-2016.pdf [hereinafter 2016 SA Report].

[55] 2016 SA Report, supra n.54, at iv.

[56] 2018 SA Report, supra n.53, at 4; 2017 SA Report, supra n.54, at 32; U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of the Inspector Gen., Semiannual Report to Congress (Oct. 1 to Mar. 31, 2017), at ix, https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/archives/semiannual/2017/sar-spring-2017.pdf [hereinafter 2017 Midyear SA Report]. Approximately $600,000 in audit receivables were reported in Fiscal Year 2017, compared with $521 million in Fiscal Year 2018. See 2017 SA Report, supra n.54, at 67; 2017 Midyear SA Report at 40; ; 2018 SA Report, supra n.53, at 4.

[57] 2018 SA Report, supra n.53, at 4.

[58] 2017 SA Report, supra n.54, at 4.

[59] See Office of Information & Regulatory Affairs, Office of Management & Budget, Agency Rule List – Fall 2018, https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/eAgendaMain?operation=OPERATION_GET_AGENCY_RULE_LIST¤tPub=true&agencyCode=&showStage=active&agencyCd=0900 (last visited Jan. 5, 2019).

[60] See Ctrs. for Medicare & Medicaid Servs., Fact Sheet: Fiscal Year (FY) 2019 Medicare Hospital Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS) and Long-Term Acute Care Hospital (LTCH) Prospective Payment System Final Rule (CMS-1694-F) (Aug. 2, 2018), https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/fiscal-year-fy-2019-medicare-hospital-inpatient-prospective-payment-system-ipps-and-long-term-acute-0.

[61] Id.

[62] See Ctrs. for Medicare & Medicaid Servs., Fact Sheet: Final Policy, Payment, and Quality Provisions Changes to the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule for Calendar Year 2019 (Nov. 1, 2018), https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/final-policy-payment-and-quality-provisions-changes-medicare-physician-fee-schedule-calendar-year.

[63] U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of Inspector Gen., 2018 Top Management and Performance Challenges, available at https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/top-challenges/2018/2018-tmc.pdf [hereinafter TMPC Report].

[64] Id.

[65] Id.

[66] Id.

[67] 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7a.

[68] 2018 SA Report, supra n.53, at 4; 2017 SA Report, supra n.54, at 4.

[69] U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of the Inspector Gen., LEIE Downloadable Databases, http://oig.hhs.gov/exclusions/exclusions_list.asp (last visited Jan. 4, 2019).

[70] Id.

[71] Id.

[72] Data gathered through HHS OIG press releases and publicly available information. See generally U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of the Inspector Gen., Civil Monetary Penalties and Affirmative Exclusions, http://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/enforcement/cmp/index.asp (last visited Jan. 4, 2019) [hereinafter CMP Assessments]; U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of the Inspector Gen., Provider Self-Disclosure Settlements, http://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/enforcement/cmp/psds.asp (last visited Jan. 4, 2019) [hereinafter Provider Self-Disclosure Settlements].

[73] See id.

[74] Id.

[75] See U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of Inspector Gen., Corporate Integrity Agreement Documents, https://oig.hhs.gov/compliance/corporate-integrity-agreements/cia-documents.asp (last visited Jan. 6, 2019).

[76] See Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, AmerisourceBergen Corp. To Pay $625 Million To Settle Civil Fraud Allegations Resulting From Its Repackaging And Sale Of Adulterated Drugs And Unapproved New Drugs, Double Billing And Providing Kickbacks (Oct. 1, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/usao-edny/pr/amerisourcebergen-corp-pay-625-million-settle-civil-fraud-allegations-resulting-its [hereinafter “ABC Settlement”].

[77] See Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Mylan Agrees to Pay $465 Million to Resolve False Claims Act Liability for Underpaying EpiPen Rebates (Aug. 17, 2017), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/mylan-agrees-pay-465-million-resolve-false-claims-act-liability-underpaying-epipen-rebates.

[78] See ABC Settlement, supra n.76.

[79] See AmerisourceBergen Corporation Corporate Integrity Agreement (Sept. 27, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/ usao-edny/press-release/file/1097511/download.

[80] Id.

[81] Id.

[82] Id.

[83] See Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Post Acute Medical Agrees to Pay More Than $13 Million to Settle Allegations of Kickbacks and Improper Physician Relationships (Aug. 15, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/post-acute-medical-agrees-pay-more-13-million-settle-allegations-kickbacks-and-improper.

[84] Id.

[85] Id.

[86] See Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Vascular Access Centers to Pay at Least $3.825 Million to Resolve False Claims Act Allegations (Oct. 23, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/vascular-access-centers-pay-least-3825-million-resolve-false-claims-act-allegations.

[87] Id.

[88] See HMA Settlement, supra n.6.

[89] Id.

[90] Press Release, Ctrs. for Medicare & Medicaid Servs., Market Saturation and Utilization Data Tool (Oct. 29 2018), https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/market-saturation-and-utilization-data-tool-4.

[91] Press Release, Ctrs. for Medicare & Medicaid Servs., Market Saturation and Utilization Data Tool (April 13, 2018), https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/market-saturation-and-utilization-data-tool.

[92] 83 Fed. Reg. 37747 (Aug. 2, 2018), https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2018/08/02/2018-16547/medicare-medicaid-and-childrens-health-insurance-programs-announcement-of-the-extension-of-temporary.

[93] U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Health Information Privacy, Enforcement Highlights (Jan. 31, 2019), https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/compliance-enforcement/data/enforcement-highlights/index.html.

[94] Data gathered through HHS press releases and other publicly available information. See generally U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., HIPAA News Releases & Bulletins, https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/newsroom (last visited Jan. 7, 2019).

[95] Id.

[96] Id.

[97] U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of Civil Rights, Guidance on Disposing of Electronic Devices and Media (July 2018), https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cybersecurity-newsletter-july-2018-Disposal.pdf.

[98] U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of Civil Rights, Considerations for Securing Electronic Media and Devices (Aug. 2018), https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cybersecurity-newsletter-august-2018-device-and-media-controls.pdf.

[99] U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of Civil Rights, National Cybersecurity Awareness Month (Oct. 2018), https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cybersecurity-newsletter-october-2018-cybersecurity-month.pdf.

[100] 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b(b).

[101] 342 F. Supp. 3d 544, (S.D.N.Y Sept. 2018).

[102] Id. at 553.

[103] Id. at 549.

[104] Carrel v. AIDS Healthcare Foundation, Inc., 898 F.3d 1267 (11th Cir. 2018).

[105] Id. at 1272-75.

[106] Id. at 1273.

[107] Id. at 1271.

[108] United States ex rel. Capshaw v. White, No. 3:12-CV-4457-N, 2018 WL 6068806 (N.D. Tex. Nov. 20, 2018).

[109] Id. at *4 (internal quotation marks omitted).

[110] Id. at *3.

[111] Id. at *4 (internal citations and quotation marks omitted).

[112] Id. (internal citations and quotation marks omitted).

[113] Id.

[114] Id.

[115] Id.

[116] Medicare and State Health Care Programs: Fraud and Abuse; Request for Information Regarding the Anti-Kickback Statute and Beneficiary Inducements CMP, 83 Fed. Reg. 43607 (Aug. 27, 2018), https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2018/08/27/2018-18519/medicare-and-state-health-care-programs-fraud-and-abuse-request-for-information-regarding-the.

[118] U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of Inspector Gen., OIG Advisory Op. 18-06 at 2-3 (July 18, 2018), https://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/docs/advisoryopinions/2018/AdvOpn18-06.pdf.

[119] Id. at 5.

[120] Id. at 5-6.

[121] See U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of Inspector Gen., OIG Advisory Op. 18-09 (Aug, 21, 2018), https://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/docs/advisoryopinions/2018/AdvOpn18-09.pdf; U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of Inspector Gen., OIG Advisory Op. 18-12 (Oct. 29, 2018), https://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/docs/advisoryopinions/2018/AdvOpn18-12.pdf.

[122] U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of Inspector Gen., OIG Advisory Op. 18-07 at 2-3 (Aug. 6, 2018), https://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/docs/advisoryopinions/2018/AdvOpn18-07.pdf.

[123] Id.

[124] Id. at 6-7.

[125] Id.

[126] U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Office of Inspector Gen., OIG Advisory Op. 18-11 at 9 (Oct. 11, 2018), https://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/docs/advisoryopinions/2018/AdvOpn18-11.pdf.

[127] Id. at 6-9.

[128] U.S. Dep’t of Health and Human Servs., Office of Inspector Gen., OIG Advisory Op. 18-14, at 1-2 (Nov. 13, 2018), https://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/docs/advisoryopinions/2018/AdvOpn18-14.pdf.

[129] Id. at 4.

[130] Id.

[131] Id. at 10-12.

[132] U.S. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., Ctrs. for Medicare & Medicaid Svcs., Medicare Program; Request for Information Regarding the Physician Self-Referral Law, 83 Fed. Reg. 29524, 29524 (June 25, 2018), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2018-06-25/pdf/2018-13529.pdf.

[133] Id. at 29525-26

[134] Roxanna Guilford-Blake, Sprinting Toward Value: HHS & Congress May Be Ready to Reconsider the Stark Law, Cardiovascular Business (Nov. 18, 2018), https://www.cardiovascularbusiness.com/topics/healthcare-economics/sprinting-toward-value-hhs-congress-may-be-ready-reconsider-stark-law.

[135] 83 Fed. Reg. at 29525.

[136] See Reforming Healthcare Report, supra n.1, at 73-74.

[137] Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Detroit Area Hospital System to Pay $84.5 Million to Settle False Claims Act Allegations Arising from Improper Payments to Referring Physicians (Aug. 2, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/detroit-area-hospital-system-pay-845-million-settle-false-claims-act-allegations-arising.

[138] Id.

[139] Press Release, U.S. Atty’s Off., U.S. Dep’t of Justice, E.D. Wis., Aurora Health Care, Inc. Agrees to Pay $12 Million to Settle Allegations Under the False Claims Act and the Stark Law (Dec. 11, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/usao-edwi/pr/aurora-health-care-inc-agrees-pay-12-million-settle-allegations-under-false-claims-act.

The following Gibson Dunn lawyers assisted in the preparation of this client update: Stephen Payne, John Partridge, Jonathan Phillips, Julie Rapoport Schenker, Claudia Kraft, Maya Nuland, Stevie Pearl, Susanna Schuemann, Margo Uhrman, and Madelyn La France.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these developments. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work or any of the following:

Washington, D.C.

Stephen C. Payne, Chair, FDA and Health Care Practice Group (+1 202-887-3693, [email protected])

F. Joseph Warin (+1 202-887-3609, [email protected])

Marian J. Lee (+1 202-887-3732, [email protected])

Daniel P. Chung (+1 202-887-3729, [email protected])

Jonathan M. Phillips (+1 202-887-3546, [email protected])

Los Angeles

Debra Wong Yang (+1 213-229-7472, [email protected])

San Francisco

Charles J. Stevens (+1 415-393-8391, [email protected])

Winston Y. Chan (+1 415-393-8362, [email protected])

New York

Alexander H. Southwell (+1 212-351-3981, [email protected])

Denver

Robert C. Blume (+1 303-298-5758, [email protected])

John D. W. Partridge (+1 303-298-5931, [email protected])

© 2019 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.