2022 Year-End False Claims Act Update

Client Alert | February 8, 2023

A dull year is rare when it comes to the False Claims Act (FCA), but this last year was exceptional by any standard. In the last twelve months, the Supreme Court decided to take up two different issues under the FCA, while the Department of Justice (DOJ) announced, yet again, billions in recoveries and nearly a thousand new FCA cases, a new record.

DOJ’s $2.2 billion in recoveries during FY 2022 marked the fourteenth straight year where recoveries exceeded $2 billion, dating back to 2008. But even more notable than the dollar amount was the sheer volume of FCA activity. DOJ obtained its recoveries from the second-highest number of settlements in history, and there were more new FCA matters initiated in FY 2022 than in any prior year, meaning the pipeline of FCA lawsuits is very full.

As in past years, FCA recoveries in the healthcare and life sciences industries continued to dominate enforcement activity in terms of the number and value of settlements, including several seven- and eight-figure settlements for alleged kickback schemes during the second half of the year. Meanwhile, notwithstanding the relatively few FCA enforcement actions related to COVID-19 in 2022, the government also signaled that it continues to take pandemic-related fraud seriously, and we expect to see increasing FCA enforcement in response to conduct arising out of the pandemic.

If there was one quiet area this year, it was on the legislative front. The FCA Amendments Act of 2021—which briefly gained momentum last year as Senator Chuck Grassley (R-IA) pushed to overhaul the FCA—remained at a standstill in Congress, and there were no other major developments in FCA legislation (federal or state).

But activity in the courts more than made up for the lack of legislation. As noted above, the Supreme Court took up two critical issues under the FCA. In December, the Supreme Court heard argument about the level of scrutiny that applies when DOJ seeks to dismiss an FCA case over the whistleblower’s objection. And just last month, the Supreme Court agreed to hear a case concerning the scienter standard under the FCA, which will have important implications for the scope of FCA liability in cases premised on alleged statutory or regulatory violations in ambiguous areas of law. Meanwhile, federal circuit courts also continued to consider the FCA’s pleading standards under Rule 9(b); the relationship between the anti-kickback statute and the FCA; and the FCA’s materiality standard, among other FCA issues.

* * *

We cover all of this, and more, below. We begin by summarizing recent enforcement activity, then provide an overview of notable legislative and policy developments at the federal and state levels, and finally analyze significant court decisions from the past six months.

As always, Gibson Dunn’s recent publications regarding the FCA may be found on our website, including in-depth discussions of the FCA’s framework and operation, industry-specific presentations, and practical guidance to help companies avoid or limit liability under the FCA. And, of course, we would be happy to discuss these developments—and their implications for your business—with you.

I. FCA ENFORCEMENT ACTIVITY

A. NEW FCA ACTIVITY

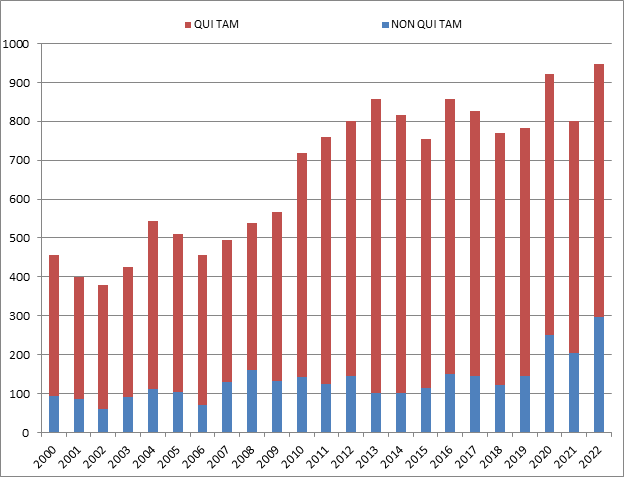

There were more new FCA cases filed in 2022 than in any year in history.[1] The government and qui tam relators filed 948 new cases, surpassing the previous record set in 2020, when there were 922 new cases. This new high-water mark shows that the volume of FCA activity is only accelerating.

Of the new cases, the government itself initiated 296 cases (referrals and investigations) outside of the qui tam setting, which is also a new record, both in terms of the total number of FCA cases initiated by the government, and as a percentage of the total number of new FCA cases.[2] In other words, the Department of Justice is bringing FCA cases on its own accord at an unprecedented pace.

This is extremely important because, historically, the vast majority of FCA recoveries come in cases where the government either brings the case or later intervenes. The relatively high level of activity from the government, therefore, suggests that recoveries in future years could be on the rise.

Number of FCA New Matters, Including Qui Tam Actions

Source: DOJ “Fraud Statistics – Overview” (Feb. 7, 2023)

B. TOTAL RECOVERY AMOUNTS: 2022 RECOVERIES EXCEED $2.2 BILLION

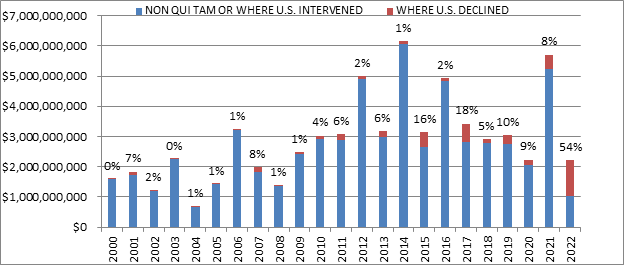

While most metrics point to a banner year, the total dollars recovered in FY 2022 ($2.2 billion) was down considerably from 2021 (when DOJ announced more than $5.6 billion), and the lowest more than a decade. This appears to reflect a relatively low number of blockbuster settlements (e.g., those in the nine-figure range). Nonetheless, it was the fourteenth consecutive year, dating back to 2008, that DOJ announced more than $2 billion in recoveries.[3]

Although the dollar value of recoveries is the lowest in more than a decade, the FCA enforcement activity is as high as ever. Indeed, DOJ touted that “[t]he government and whistleblowers were party to 351 settlements and judgments, the second-highest number of settlements and judgments in a single year.”[4] In other words, even if the dollar figures were not record setting, the number of successful DOJ cases was.

Whistleblower activity also remains a critical part of the FCA. Of the $2.2 billion in recoveries DOJ reported, more than $1.9 billion came from lawsuits that were initially filed under the qui tam provisions of the FCA (and then pursued by either the government or whistleblowers).[5] This is consistent with historical trends.

A more unusual datapoint this year was the percentage obtained in cases where the U.S. declined to intervene. Historically, DOJ’s decision on whether to intervene is a critical inflection point that strongly predicts whether a case will be successful: this makes sense, as DOJ is more likely to intervene in cases that it believes are “winners.” But this year, a remarkable 54% of recoveries were in non-intervened cases. This number is strongly skewed, however, by a single case against a pharmaceutical company where DOJ did not intervene and the Relator obtained a settlement of nearly $900 million. If that case is removed, then the data looks much more consistent with historical trends—suggesting the continued importance of DOJ intervention decisions.

Settlements or Judgments in Cases Where the Government Declined Intervention as a Percentage of Total FCA Recoveries

Source: DOJ “Fraud Statistics – Overview” (Feb. 7, 2023)

C. FCA Recoveries by Industry

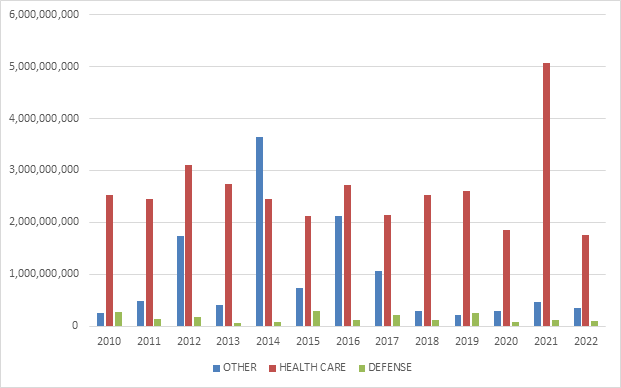

The relative breakdown of FCA recoveries across industries remained relatively consistent with past years. Healthcare cases comprised 80% of total recoveries, Department of Defense procurement issues made up 5%, and the remaining 15% was split among other industries.[6]

Within the healthcare industry, DOJ announced significant recoveries across a range of theories, including Medicaid fraud, unnecessary and substandard care, kickbacks, and Medicare Advantage fraud. DOJ also announced significant recoveries from Department of Defense contractors, and, as discussed further below, the beginnings of significant COVID-19 related activity.[7]

FCA Recoveries by Industry

Source: DOJ “Fraud Statistics – Overview” (Feb. 7, 2023)

II. NOTEWORTHY DOJ ENFORCEMENT ACTIVITY DURING THE SECOND HALF OF 2022

We summarize below the most notable FCA settlements in the second half of calendar year 2022, with a focus on the industries and theories of liability involved. We covered settlements from the first half of the year in our 2022 Mid-Year Update.

FCA recoveries in the healthcare and life sciences industries continued to dominate enforcement activity during the second half of the year in terms of the number and value of settlements.

- On June 28, 15 Texas-based doctors agreed to pay a total of $2.83 million to settle allegations that they violated the FCA by accepting illegal kickbacks in exchange for patient referrals to three companies providing laboratory testing services. The government alleged that one of the testing companies paid “volume-based commissions” to independent recruiters, who, in turn, used management service organizations (MSOs) to pay the doctors for their referrals to the testing companies. The payments from the MSOs to the doctors “were allegedly disguised as investment returns but in fact were based on, and offered in exchange for, the doctors’ referrals.” As of June 28, the United States had reached settlements with 33 physicians, two executives, and a laboratory in the same alleged scheme, and in May 2022, it filed a FCA lawsuit in the Eastern District of Texas against, inter alia, the three chief executive officers of the testing companies. See United States ex rel. STF, LLC v. True Health Diagnostics, LLC, No. 4:16-cv-547 (E.D. Tex.).[8]

- On June 30, a Florida nursing and assisted living system agreed to pay $1.75 million to resolve allegations that it violated the FCA by providing COVID-19 vaccinations for hundreds of ineligible individuals. The government alleged that the system invited and facilitated vaccines for board members, donors and potential donors, and other ineligible individuals as part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Pharmacy Partnership for Long-Term Care Program, which was designed to vaccinate long-term care facility residents and staff when doses of COVID-19 vaccine were in limited supply early in the CDC vaccination program.[9]

- On July 1, a spinal implant devices distributor headquartered in Utah, its two owners, and two of their physician-owned distributorships agreed to pay $1 million to resolve a lawsuit against them alleging that they violated the FCA by paying purported kickbacks to physicians. The government alleged that the distributor’s physician-owned distributorships allowed them to pay physicians to use the distributor’s medical devices in surgeries. The settlement was reached after the first day of trial.[10]

- On July 7, a West Virginia hospital agreed to pay $1.5 million to resolve allegations that it violated the FCA by knowingly submitting or causing the submission of claims to Medicare in violation of the Stark Law. The settlement stems from the hospital’s voluntary self-disclosure of potential violations of the Stark Law by paying compensation to referring physicians that allegedly exceeded fair market value or took into account the volume or value of the physicians’ referrals to the hospital.[11]

- On July 13, a Florida-based pharmacy entered into a deferred prosecution agreement (DPA) and agreed to pay a $1.31 million civil settlement to resolve allegations that it submitted fraudulent claims to Medicare for a high-priced drug used in rapid reversal of opioid overdoses. The government alleged that the pharmacy completed prior authorization forms for the drug in place of the prescribing physicians, including instances in which the pharmacy staff signed the forms without the physician’s authorization and listed the pharmacy’s contact information as if it were the physician’s information. The government further alleged that the pharmacy submitted prior authorization requests for the drug that contained false clinical information to secure approval for the expensive drug. In connection with the settlement, HHS agreed to release its right to exclude the pharmacy and its CEO in exchange for their agreements to enter into a three-year Integrity Agreement with the U.S. Department of Health, Office of Inspector General (HHS OIG) that requires, among other things, the pharmacy to implement measures designed to ensure that its submission of claims for pharmaceutical products complies with applicable law relating to prior authorizations and collection of beneficiary co-payment obligations. The settlement resolves claims brought in a qui tam suit by a former employee of the manufacturer of the drug. As part of this resolution, the relator will receive $262,000 of the settlement amount.[12]

- On July 14, a New Jersey company providing laboratory testing services and its corporate parent agreed to pay $9.85 million to resolve alleged violations of the FCA arising from the company’s payment of above-market rents to physician landlords for office space in exchange for patient referrals from those physicians. The testing company rented office space from several physicians and physicians’ groups for Patient Service Centers (PSCs), where it collected blood samples from patients. In the settlement agreement, the testing company admitted that it artificially inflated its rental payments to physician landlords for the PSCs by (i) “inaccurately measur[ing] the amount of space that [it] would use exclusively,” and (ii) “includ[ing] a disproportionate share of the common spaces” in the calculations of office space for which it made payments. The testing company also admitted that it considered the number of referrals it received from physician landlords “when deciding whether to open, maintain or close” the PSCs, and that both the testing company and its parent entity had conducted internal audits that previously identified some of the above-market lease payments but did not report these findings to the Federal Government. Under the settlement, the testing company and its parent entity will also pay the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and the State of Connecticut $141,041 and $5,001, respectively, to resolve alleged violations of those states’ FCA statutes, and the testing company entered into a separate Corporate Integrity Agreement (CIA) with HHS OIG. The settlement also resolved claims brought under a qui tam suit filed by a former employee of both the testing company and the parent entity; the whistleblower will receive $1.7 million as her share of the recovery.[13]

- On July 20, a Texas-headquartered clinical laboratory agreed to pay $16 million to resolve allegations that it submitted false claims for payment to federal healthcare programs, including Medicare. The government alleged that the clinical laboratory systematically conducted unnecessary additional testing on biopsy specimens prior to a pathologist’s review and without an individualized determination confirming the legitimate necessity for additional testing. The settlement resolved a qui tam suit filed by a relator who received $2.72 million of the recovery amount.[14]

- On July 22, an Oregon-based medical device manufacturer agreed to pay $12.95 million to settle allegations that it violated the FCA by paying illegal kickbacks to physicians to induce their use of the manufacturer’s pacemakers, defibrillators, and other implantable cardiac devices. The settlement resolved allegations that the manufacturer made excessive payments to physicians it hired to train its new employees, such as “for training events that either never occurred or were of little or no value to the trainees,” to induce or reward the physicians’ use of the manufacturer’s devices. Additionally, the settlement resolved separate allegations that the manufacturer paid physicians illegal kickbacks in the form of “holiday parties, winery tours, lavish meals with no legitimate business purpose and international business class airfare and honoraria in exchange for making brief appearances at international conferences.” The settlement also includes a resolution of claims brought in a qui tam suit by two of the manufacturer’s former sales representatives, who will receive approximately $2.1 million total as their share of the recovery.[15]

- On July 22, clinical laboratories in Mississippi and Texas and two of their owner/operators agreed to pay $5.7 million to resolve allegations that they caused the submission of false claims to Medicare by paying kickbacks in return for genetic testing samples. The government alleged that the laboratories and their owner/operators participated in a genetic testing fraud scheme with various marketers whereby the marketers solicited genetic testing samples from Medicare beneficiaries and arranged to have a physician fraudulently attest that the genetic testing was medically necessary. The laboratories would then process the tests, receive reimbursement from Medicare, and pay a portion of that reimbursement to the marketers. The owner/operators have each previously pled guilty to one count of conspiracy to defraud the United States in connection with this scheme.[16]

- On August 18, a California organized health system and three medical care providers agreed to pay a total of $70.7 million to settle allegations that they broke federal and state laws by submitting or causing the submission of false claims to Medi-Cal related to Medicaid Adult Expansion under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. The settlements resolve allegations that the parties knowingly submitted or caused the submission of false claims to Medi-Cal for “Additional Services” provided to Adult Expansion Medi-Cal members between January 1, 2014 and May 31, 2015. In addition to the FCA settlement, two of the parties entered into a CIA. The settlements resolve claims brought by qui tam relators under the FCA and the California False Claims Act.[17]

- On August 23, a Texas company that manufactures, markets, and distributes optical lenses agreed to pay $16.4 million to resolve allegations that it violated the FCA by paying illegal kickbacks to eye care providers, such as optometrists and ophthalmologists, to induce them to prescribe the company’s products to patients. The company also entered into a CIA. The settlement also resolved claims brought in two qui tam suits filed by several of the company’s former district sales managers; the whistleblowers’ share of the recovery was not reported.[18]

- On September 1, a manufacturer of durable medical equipment (DME) agreed to pay $24 million to settle allegations that it misled multiple federal healthcare programs by paying kickbacks to DME suppliers. The government alleged that the manufacturer cased DME suppliers to submit false claims for oxygen concentrators, ventilators, CPAP and BiPAP machines, and other respiratory-related medical equipment because the manufacturer provided illegal inducements to the DME suppliers by providing them with physician prescribing data free of charge that could assist their marketing efforts. The settlement required the manufacturer to pay $22.62 million to the United States, and $2.13 million to various states as a result of the impact to their Medicaid programs, pursuant to the terms of separate settlement agreements entered into with the respective states. Additionally, the manufacturer entered into a CIA. The settlement also resolved a qui tam lawsuit brought by an employee of the manufacturer, who received approximately $4.3 million of the recovery amount.[19]

- On September 2, a pharmaceutical manufacturer agreed to pay $40 million to resolve allegations that the manufacturer paid kickbacks to hospitals and physicians to induce them to utilize certain drugs, marketed these drugs for off-label uses that were not reasonable and necessary, and downplayed the safety risks of a drug used to control bleeding in certain heart surgeries. The government also alleged that the manufacturer downplayed the efficacy and health risks associated with a drug used to treat cholesterol and induced a government agency to renew certain contracts relating to the same drug. The settlement resolved allegations brought in two qui tam suits by a former employee, who will receive approximately $11 million from the proceeds of the settlement.[20]

- On September 13, DOJ announced a settlement with a Texas bank for allegedly processing a Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loan on behalf of an ineligible borrower. The U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of Texas, which brought the case, described the settlement as the “first-ever” settlement under the FCA from a PPP “lender”—i.e., the bank that made the loan, not a fraudulent borrower.[21]

- On September 15, a pharmaceutical company agreed to pay $7.9 million to settle allegations that it violated the FCA by causing the submission of claims to Medicare Part D for several generic drugs that utilized outdated “prescription-only” (“Rx-only”) labeling, even though the drugs had lost their Rx-only status and thus were no longer reimbursable under Medicare Part D. Under federal law, pharmaceuticals that require a prescription to be dispensed (i.e., Rx-only drugs) are reimbursable under Medicare Part D, whereas pharmaceuticals that do not require a prescription—and can be sold to customers over the counter (OTC)—are not eligible for reimbursement. As part of the settlement, the pharmaceutical company admitted that in order to boost profits, it delayed seeking conversion of three generic drugs it manufactures “even after learning that the brand-name drugs for each had converted to OTC status,” and that it continued to sell the drugs under “obsolete Rx-only labeling” rather than taking the drugs off the market. The pharmaceutical company received credit under the DOJ’s prosecution guidelines for disclosure, cooperation, and remediation. The settlement also resolved claims brought by a whistleblower in a qui tam suit; the whistleblower will receive approximately $946,000 as their share of the recovery.[22]

- On September 26, a pharmaceutical company agreed to pay $900 million to resolve allegations that it caused false claim submissions to Medicare and Medicaid by paying kickbacks to physicians as part of a scheme to induce them to prescribe the pharmaceutical company’s drugs. The allegations stem from a qui tam lawsuit filed by a former employer of the pharmaceutical company; the government declined to intervene in the lawsuit, which the whistleblower pursued individually. The whistleblower’s complaint alleged that the company offered and paid remuneration in various forms to induce physicians to prescribe the company’s drugs, including speaker honoraria and training fees, consulting fees to healthcare professionals who participated in the company’s speaker programs, training meetings, or consultant programs. The whistleblower received 29.6% or approximately $266 million from the settlement proceeds, the largest single whistleblower award on record, according to the whistleblower’s attorney. The $900 million settlement is also the largest recovery ever in a declined case.[23]

- On October 12, several pharmacy companies agreed to pay nearly $6.9 million to settle allegations that they violated the FCA by waiving patient copays, overcharging government health insurance programs, and trading healthcare business after they were removed from networks. Specifically, the government alleged that a compounding pharmacy and a related entity, created to handle the compounding pharmacy’s billing, created a copay-waiver program for patients and misled the government about the price being charged to uninsured, cash-paying patients by stating that that price was higher than it was, resulting in TRICARE beneficiaries being charged more than uninsured, cash-paying patients. The government also alleged that the compounding pharmacy sold its out-of-network prescriptions to other pharmacies after it was removed by some networks and received a portion of proceeds back. The settlement resolved allegations brought in a qui tam suit by a former accountant of the compounding pharmacy. She will receive approximately $1.4 million as her share of the recovery from the settlement.[24]

- On October 17, a healthcare services provider in California agreed to pay approximately $13 million to resolve allegations that it violated the FCA by billing federal insurance programs for urine toxicology tests that it did not actually perform. The United States alleged that under the terms of a contract with another company, urine toxicology specimens from physicians and laboratories were forwarded to the healthcare services provider. The United States contended that the provider sought reimbursement from the federal government for thousands of tests that it did not perform and that “were instead performed by third-party labs.”[25]

- On October 18, an Oklahoma-based for-profit home health provider, its affiliates, and the President and COO agreed to pay $7.2 million to resolve allegations that they violated the FCA by billing the Medicare program for medically unnecessary therapy provided to patients in Florida. The government alleged that the home health provider billed Medicare knowingly and improperly for home healthcare patients in Florida based on therapy provided without regard to medical necessity and overbilled for therapy by upcoding patients’ diagnoses. Both the President and COO agreed to be excluded from participation in all federal healthcare programs for a period of five years. The home health provider agreed to be bound by the terms of a CIA with HHS OIG. The settlement resolves a qui tam action brought by therapists formerly employed by the home health provider. The relators will together receive $1.3 million as their share of the settlement. Contemporaneous with the settlement, the home health provider agreed to pay an additional $22.9 million to resolve another qui tam action brought in the Western District of Oklahoma which alleged that the home health provider improperly paid remuneration to its home health medical directors in Oklahoma and Texas for the purpose of inducing referrals of Medicare and TRICARE home health patients.[26]

- On November 1, a cloud-based electronic health record (EHR) technology vendor agreed to pay $45 million to settle allegations that it violated the FCA by accepting and paying unlawful remuneration in exchange for referrals through multiple kickback schemes. The government alleged that the EHR technology vendor, who sells EHR systems subscriptions services, petitioned and accepted kickbacks in exchange for recommending and arranging for its users to utilize another company’s pathology laboratory services. Additionally, the EHR technology vendor allegedly conspired with the same third-party laboratory to improperly donate EHR to healthcare providers with the goal to increase lab orders for the third-party laboratory and concurrently increase the EHR technology vendor’s user base. The government further alleged that the EHR technology vendor paid kickbacks to its customers and to other influential parties in the healthcare industry to secure recommendations and referral for its EHR The settlement also resolved, in part, the qui tam lawsuit filed by a former vice president of the EHR technology vendor, who received approximately $9 million from the settlement agreement.[27]

- On November 9, the successor in interest to a Tennessee-based real estate investment trust agreed to pay $3 million to resolve allegations that the trust violated the FCA by submitting false claims to Medicare and Medicaid. The government alleged that the trust paid kickbacks to physicians to induce them to refer patients to a hospital developed by an affiliated party. The government alleged that the trust offered the physicians a low-risk, high-reward investment in a joint venture formed by one of the parties to purchase the hospital and lease it back to the affiliated party. The allegations were initially brought in a qui tam lawsuit by two relators. The qui tam suit remains under seal, subject to an order of the Court permitting the United States to disclose the settlement.[28]

- On November 10, a birth-related injury compensation plan created by the State of Florida and the plan’s administrator agreed to pay $51 million to settle a qui tam lawsuit alleging that it violated the FCA by causing participants in the plan to submit covered claims to Medicaid rather than to the compensation plan, contrary to “Medicaid’s status as the payer of last resort under federal law.” The whistleblowers will receive $12,750,000 as their share of the recovery. While the United States did not intervene in the case, it assisted the whistleblowers with defending against a motion to dismiss filed by the defendants and with negotiating the settlement.[29]

- On December 5, a New Jersey based opioid abuse treatment facility agreed to pay $3.15 million to settle civil and criminal allegations that it paid kickbacks, obstructed a federal audit, and submitted fraudulent claims to Medicaid. The government alleged that the facility submitted false claims to Medicaid related to a kickback relationship with a methadone mixing company with whom it shared a related ownership and management history. The settlement further resolved allegation that the facility failed to maintain adequate supervision and staffing, relying instead on non-credentialed interns to provide services. Related to the criminal allegations, the facility agreed to enter into a three-year deferred prosecution agreement that requires it to abide by certain measures, including, among other things, creating an independent board of advisors to oversee the company’s compliance relating to federal healthcare laws.[30]

- On December 12, a not-for-profit health system, community hospital, and medical center agreed to pay $22.5 million to resolve allegations that they violated the FCA and California FCA by submitting claims for services that were unallowable medical expenses under the contract between the California’s Department of Health Care Services and a California county organized health system. The settlement also resolved allegations that the reimbursements for services did not reflect the fair market value of services provided and that services were duplicative of services already required to be rendered. Further, the government alleged that the payments were unlawful gifts of public funds in violation of the California Constitution. The settlement also resolved allegations brought in a qui tam suit by a former medical director of a California county organized health system, who will received $3.9 million as his share of the federal recovery.[31]

- On December 13, a Jacksonville-based company and its subsidiary agreed to pay $3 million to resolve allegations that they violated the FCA by paying and receiving kickbacks in connection with genetic testing samples. The government alleged that the companies solicited genetic testing samples from Medicare beneficiaries and paid physicians to falsely attest that the genetic testing was medically necessary and arranged for laboratories to process the tests. The laboratories would pay a portion of the reimbursement to the company. The settlement also resolved allegations brought in a qui tam suit by two individuals who were approached to participate in the scheme. They received approximately $570,000 as their share of the recovery.[32]

III. LEGISLATIVE AND POLICY DEVELOPMENTS

A. FEDERAL POLICY AND LEGISLATIVE DEVELOPMENTS

1. Changes to Rules Regarding Overpayments

On December 14, CMS issued a proposed rule which would, among other things, change the standard for what it means for Medicare program participants to “identify” overpayments.[33] The Affordable Care Act requires any person who has received an overpayment from a federal healthcare program to report and return that overpayment within 60 days after it is “identified.” Under Medicare rules issued in 2014 and 2015, CMS advised that a program participant has “identified” an overpayment when it “has, or should have through the exercise of reasonable diligence, determined” that it received an overpayment.[34] The definition is significant to the FCA because, once an overpayment is “identified,” then an “obligation” may exist under the “reverse false claim” provision of the FCA, which prohibit acts of fraud aimed at avoiding paying money to the United States, if the overpayment is not returned within the required 60-day period.[35]

CMS’s stated rationale behind its interpretation of the term “identified” was that it would align with the FCA’s knowledge requirement, which creates fraud liability if an overpayment is improperly retained with actual knowledge, reckless regard, or deliberate ignorance of that overpayment. In 2018, however, a federal district court ruled that to the contrary, the “should have through the exercise of reasonable diligence” standard created by CMS has the effect of punishing simple negligence instead.[36] In direct response to that opinion, the new proposed rule would eliminate the “reasonable diligence” standard and instead deem an overpayment “identified” when a program participant—consistent with the scienter requirement of the FCA—has actual knowledge of an overpayment, or deliberately ignores or recklessly disregards an overpayment.[37]

In a related development, CMS finalized a rule on January 30, 2023 that enhances the government’s audit powers over Medicare Advantage plans (i.e., Medicare “private” plans).[38] The rule provides that, when seeking to collect overpayments from Medicare Advantage plans via Risk Adjustment Data Validation (RADV) audits, CMS will extrapolate audit findings for the relevant year forward to all payment years; however it will do so starting only with payment year (PY) 2018.[39] This is an important change from the initial proposed rule, which would have called for extrapolation starting in PY 2011.[40] The new RADV rule nevertheless has the potential to significantly expand the universe of risk adjustment data that is subject to audit, as the RADV audits are a primary program integrity tool for CMS in overseeing the Medicare Advantage program. That, in turn, creates additional potential “obligations” under the FCA and the forthcoming new CMS interpretative guidance regarding the 60-Day Rule, as applied to Medicare Advantage plans. Medicare Advantage plans have disputed many other aspects of this audit process and proposed rule, and we anticipate that those disputes will continue to play out in various contexts, including several ongoing FCA cases on related topics and issues. We will be tracking further developments stemming from the new rule as 2023 unfolds.

2. Enforcement Efforts Related to COVID‑19

Based on publicly available settlements, civil FCA enforcement actions related to COVID‑19 spending have been relatively few in number in relation to the Justice Department’s criminal enforcement activity. Indeed, if one were to compare sheer public displays of enforcement activity and resource commitment in the criminal versus civil realms, it would be easy to wonder whether civil enforcement is lagging behind criminal prosecutions. In September, for example, DOJ announced the establishment of three Strike Force teams, which will operate out of U.S. Attorney’s Offices in the Southern District of Florida, in the District of Maryland, and in California as a joint effort between the Central and Eastern Districts of California.[41] The prosecutor-driven Strike Force teams will “accelerate the process of turning data analytics into criminal investigations,” according to DOJ.[42]

As discussed in our 2021 Year-End Update, however, early civil enforcement activity is likely only the start of a years-long effort by DOJ to wield the FCA to combat fraud related to pandemic relief funds. Because FCA cases are filed under seal, and often take years to investigate, we may not see the full extent of pandemic-related FCA activity for years to come. But developments in the second half of 2022 lend support to the idea that DOJ is playing a long game when it comes to civil enforcement in areas affected by the pandemic.

We see this in part in developments at HHS OIG, one of DOJ’s most frequent partner agencies in FCA enforcement. In September, HHS OIG released the results of a study into telehealth services provided during the first year of the pandemic, including a description of “providers’ billing for telehealth services and [ ] ways to safeguard Medicare from fraud, waste, and abuse related to telehealth.”[43] According to HHS OIG, at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the use of telehealth—which preceded the pandemic—increased dramatically while, at the same time, the government temporarily paused program integrity efforts for Medicare, such as claims reviews. The study’s focus was on providers that billed for telehealth services and particularly those providers “whose billing for telehealth services poses a high risk to Medicare.”

The study established a number of criteria suggesting fraud, waste, or abuse, which HHS OIG used to determine providers that posed a high risk to the Medicare program and “warrant further scrutiny.” The seven criteria are: (1) “billing both a telehealth service and a facility fee for most visits”; (2) “billing telehealth services at the highest, most expensive level every time”; (3) “billing telehealth services for a high number of days in a year”; (4) “billing both Medicare fee-for-service and a Medicare Advantage plan for the same service for a high proportion of services”; (5) “billing a high average number of hours of telehealth services per visit”; (6) “billing telehealth services for a high number of beneficiaries”; and (7) “billing for a telehealth service and ordering medical equipment for a high proportion of beneficiaries.” According to the report, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) will “follow up on the providers identified in [the] report.”

Similarly, a December 2022 report by HHS OIG focused on laboratory testing for “add-on tests” in conjunction with COVID‑19 tests, and “found that 378 labs billed Medicare Part B for add‑on tests at questionably high levels . . . compared to the 19,199 other labs [studied].”[44] The report details specific types of “add-on” tests and dollar figures associated with Medicare payments for them.[45]

Studies such as these serve several functions. On one level, they signal to the public that the government is serious about fraud, waste, and abuse enforcement in industries affected by the pandemic, and they leverage partner agency investigative and analytical resources to provide DOJ (and the private relator’s bar) with insights for aligning enforcement efforts with agency programmatic priorities. They also demonstrate that the development of data-driven enforcement actions requires significant commitments of time and resources at the client agency level—a reality that helps explain why civil enforcement has publicly seemed slower compared to criminal prosecutions. And they serve as a reminder that DOJ does not view pandemic-related stimulus programs as the limit of its enforcement efforts; rather, we can expect DOJ to wield the FCA in response to industry developments prompted by the pandemic, beyond simply using the statute to recover fraudulently obtained stimulus funds.

Meanwhile, public signs of DOJ’s FCA enforcement efforts related to pandemic relief have continued to appear. In September, as discussed above, DOJ announced a settlement with a bank for allegedly processing a Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loan on behalf of an ineligible borrower.[46] The announcement is significant because PPP FCA cases have typically been brought against borrowers who submitted false information. This is the first public settlement with a PPP lender, signaling that DOJ’s investigations have not been limited to borrowers (and that this case may not be the last one against a lender).

3. FCA Amendments Act of 2021 Still Pending Floor Vote

The FCA Amendments Act of 2021 (S. 2428) reached the end of the legislative session without a vote, having stalled continuously since it was reported out of the Senate Judiciary Committee in November 2021. The bill, introduced in July 2021 by Senator Chuck Grassley (R-IA) and a bipartisan group of co-sponsors, proposed two significant changes to the FCA.[47] First, it would amend the materiality requirement by providing that the government’s continued payment of funds to a defendant after discovery of fraud is not determinative of a lack of materiality “if other reasons exist for the decision of the government with respect to such refund or repayment.” Second, the bill would change the standard of review for evaluating a relator’s objection to the government’s decision to dismiss an FCA action.

In July 2022, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) issued a lukewarm score on the proposed amendments.[48] With respect to the materiality amendment, the CBO estimated that DOJ would “succeed in about three FCA cases each year that would not otherwise have been won,” which would result in increasing collections by about $145 million over the decade of 2022-2032. However, the CBO did not indicate whether it factored in the potential for prolonged litigation and discovery costs arising from the need for the government to prove other reasons for having continued payment of claims despite knowledge of fraudulent activity. The predicted increase in collections must also be viewed in light of the CBO’s estimates regarding the increased costs likely to result from the bill’s imposition of a heightened burden on the government when it decides to dismiss an FCA action over a relator’s objection. The CBO estimated costs of $15 million to implement the amended dismissal requirements over the next five years, assuming an “additional month of work” for each case. While the CBO stated that its conclusions were “subject to considerable uncertainty,” the report is far from a clear endorsement of the proposed legislation, and may help explain its failure to progress in the Senate.

It is possible that the Senate also is waiting to see how the Supreme Court will rule in United States ex rel. Polansky v. Executive Health Resources, Inc. (discussed in our Case Law Developments update below). Polansky presents a challenge to the government’s right to seek dismissal, over a relator’s objection, of an FCA action in which the government has declined to intervene. During oral argument in December, the Justices appeared supportive of the government’s dismissal authority and seemed likely to set a low threshold for dismissal. The Senate also may also now be looking beyond Polansky to the Supreme Court’s grant of certiorari in United States ex rel. Schutte v. SuperValu Inc. et al. As discussed below, that case challenges the relevance of a defendant’s subjective beliefs to the FCA’s scienter requirement. Although Schutte does not directly involve the FCA provisions at issue in the Grassley amendments, the interrelated nature of the statute’s materiality and scienter requirements means that the decision in Schutte still could affect the trajectory of the Grassley amendments and the extent to which the materiality related amendment in particular is viewed as a necessity.

4. Congress Extends Limitations Period on CARES Act Fraud Prosecutions to 10 Years

On August 5, 2022, President Biden signed into law two bills extending the statute of limitations for CARES Act anti-fraud actions.[49] The laws establish a 10-year statute of limitations period for “any criminal charge or civil enforcement action” alleging fraud related to the Economic Injury Disaster Loan (EIDL) program or the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP). The EIDL and PPP programs both sprung from the Coronavirus Air, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) and provided loans and emergency grants during the pandemic.[50] With respect to PPP loans, the legislation appears aimed at financial technology firms and their lenders, which the House Committee on Small Business calculated account for up to 75% of loans connected to fraud.[51] Unlike bank-related fraud, which carries a 10-year statute of limitations, see 18 U.S.C. § 3282, loan fraud connected to financial technology carries the 5-year limitations period for wire fraud, see 18 U.S.C. § 3293. The new laws aim to reconcile that discrepancy.

While the amendments are styled as changes to the Small Business Act in particular, they could have an effect on uses of the FCA to combat COVID relief fraud—if, for example, DOJ succeeds in arguing that the amendments actually do operate to extend the FCA’s statute of limitations, or if in practical terms the amendments make it easier for DOJ to rely on SBA-led enforcement actions rather than use the FCA itself. While the FCA also permits actions up to 10 years after the date of the violation, that outer limit only applies where the government or a relator utilizes the provision that tolls the default 6-year statute of limitations for 3 years from the date on which the government learns of the alleged violation.

B. STATE LEGISLATIVE DEVELOPMENTS

There were no major developments with respect to state FCA legislation in the second half of 2022. HHS OIG provides incentives for states to enact false claims statutes in keeping with the federal FCA. HHS OIG approval for a state’s FCA confers an increase of 10 percentage points in that state’s share of any recoveries in cases involving Medicaid.[52] Such approval requires, among other things, that the state FCA in question “contain provisions that are at least as effective in rewarding and facilitating qui tam actions for false or fraudulent claims” as are the federal FCA’s provisions.[53] Approval also requires a 60-day sealing provision and civil penalties that match those available under the federal FCA.[54] Consistent with our reporting in prior alerts, the lists of “approved” and “not approved” state false claims statutes remain at 22 and 7, respectively.[55]

IV. CASE LAW DEVELOPMENTS

A. SUPREME COURT WEIGHS GOVERNMENT’S AUTHORITY TO DISMISS QUI TAM LAWSUITS AND AGREES TO HEAR CRITICAL SCIENTER ISSUE

The Supreme Court granted certiorari this month on a petition regarding the question of whether a defendant who adopts an objectively reasonable interpretation of a legal obligation runs afoul of the FCA’s requirement that the defendant act “knowingly.” United States ex rel. Schutte v. SuperValu Inc., 9 F.4th 455 (7th Cir. 2021), cert. granted, 2023 WL 178398 (U.S. Jan. 13, 2023); United States ex rel. Proctor v. Safeway, Inc., 30 F.4th 649 (7th Cir. 2022), cert. granted, 2023 WL 178393 (U.S. Jan. 13, 2023). As noted above, the FCA defines “knowingly” to mean that a person “(i) has actual knowledge of the information; (ii) acts in deliberate ignorance of the truth or falsity of the information; or (iii) acts in reckless disregard of the truth or falsity of the information.” 31 U.S.C. § 3729(b)(1)(A). In Safeco Insurance Co. of America v. Burr, 551 U.S. 47 (2007), which addressed the Fair Credit Reporting Act’s nearly identical scienter requirement, the Supreme Court determined that a person who acts under an incorrect interpretation of a relevant statute or regulation does not act with “reckless disregard” if the interpretation is objectively reasonable and no authoritative guidance cautioned the person against it. Safeco, 551 U.S. at 70.

The relators in SuperValu alleged that when defendant SuperValu sought Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements, it misrepresented its “usual and customary” drug prices to government health programs that use that information to set reimbursement rates. See 9 F.4th at 459. After interpreting the relevant regulations, SuperValu reported its retail cash prices as its usual and customary drug prices rather than the lower, price-matched amounts that it charged customers under its price-match discount drug program, through which SuperValu would match discounted prices of local competitors upon request from anyone purchasing. Id. While the court agreed with the relator that SuperValu should have reported its discounted prices, the court applied the Safeco approach and determined that SuperValu’s interpretation of the regulations was objectively reasonable and that there was no authoritative guidance that warned SuperValu away from its interpretation. Id. at 472. According to the Seventh Circuit, whether SuperValu believed that its interpretation of “usual and customary” drug prices was the correct interpretation of the regulation did not bear on the objectively reasonable analysis. Instead, the court explained that “[a] defendant might suspect, believe, or intend to file a false claim, but it cannot know that its claim is false if the requirements for that claim are unknown.” Id. at 468. In other words, the focus should be on whether the interpretation was objectively reasonable, not on the defendant’s subjective intent. See id. at 466. The court therefore found that SuperValu faced no liability under the FCA. Id. at 472. This decision aligns with every other circuit that has considered Safeco’s application to the FCA (i.e., the Third, Eighth, Ninth, and D.C. Circuits).

The Supreme Court also granted a petition for certiorari in Safeway, which the Court then consolidated with SuperValu. Safeway dealt with substantially the same issue and outcome: applying the Safeco approach to Safeway’s interpretation of “usual and customary” drug prices to determine whether Safeway had violated the FCA. 30 4th at 658–59. Applying its decision from SuperValu, the Seventh Circuit in Safeway also found no liability for Safeway under the FCA because it had adopted an objectively reasonable interpretation of the relevant regulations and there was no authoritative guidance. Id. at 660, 663.

After the relators petitioned for a writ of certiorari, the Supreme Court asked the federal government to weigh in. The Solicitor General’s office disagreed with the position adopted by the Seventh Circuit, insisting that it opens up the possibility that defendants may be aware that their interpretation of a regulatory provision is wrong, but still proceed with the noncompliant action as long as they can later assert a reasonable justification for their preferred interpretation of the regulation after the fact. See United States ex rel. Schutte v. Supervalu Inc., No. 21-1326, Brief for the United States as Amicus Curiae, at 11–12 (Dec. 6, 2022). Senator Grassley, one of the chief proponents of the FCA in Congress, had filed an amicus brief as well, claiming that the Seventh Circuit opens a “gaping hole” in the FCA and urging the Supreme Court to grant certiorari and overturn the decision. See United States ex rel. Schutte v. Supervalu Inc., No. 21-1326, Brief for Senator Charles E. Grassley as Amicus Curiae, at 23 (May 19, 2022).

The Supreme Court’s resolution of this issue in SuperValu will have significant consequences going forward for FCA defendants, like SuperValu, who often are accused of certifying compliance with complex regulatory schemes. Defendants frequently argue the so-called Safeco defense, and the Supreme Court’s treatment of that issue could clarify the strength and scope of that defense. The Court’s decision will provide necessary guidance on whether a defendant can be “reckless” toward a statute or regulation that is amenable to multiple interpretations, even if the defendant allegedly doesn’t subjectively believe that interpretation to be correct. Coming on the heels of the Supreme Court’s seminal 2016 decision in Universal Health Services v. United States ex rel. Escobar, 579 U.S. 176 (2016), which clarified and strengthened the FCA’s materiality standard, this will be an opportunity for the Court to round out its jurisprudence on key elements of the FCA by addressing the statute’s scienter standard. We will be watching closely as this critical case gets its day at the Supreme Court.

In December, the Supreme Court heard oral argument in United States ex rel. Polansky v. Executive Health Resources, Inc., 17 F.4th 376 (3d Cir. 2021), cert. granted, 142 S. Ct. 2834 (2022). As we noted in the 2022 Mid-Year Update, the Supreme Court’s rather unexpected decision to grant certiorari in this case should at least result in a clarified standard for district courts to apply to government requests to dismiss qui tam complaints.

Until the Court issues its ruling on Polansky, the circuits remain split as to the standard under which a district court may evaluate the government’s decision to dismiss relators’ cases over their objection. Some courts have concluded that the government may dismiss virtually any action brought on behalf of the government, with very little scrutiny. Polansky, 17 F.4th at 384–88. Other courts have determined that if the government does not intervene in a relator’s case, the government must first intervene in the lawsuit before seeking to dismiss it under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 41(a)’s standard. Id. Yet another subset of courts have indicated that the government must have some reasonable basis for the decision to dismiss, and ostensibly apply a degree of scrutiny to dismissal decisions. Id.

At oral argument, the Justices seemed inclined to grant DOJ broad discretion to dismiss cases, which is both a necessary check on runaway whistleblower litigation brought in the government’s name and a constitutional prerequisite to ensure the qui tam provision does not run afoul of constitutional limits on the executive branch’s ability to delegate its authority.

Regardless of how the Court resolves Polansky, however, the outcome is unlikely to have any immediate or substantial impact on the routine course of qui tam actions. In practice, district courts almost always agree to dismiss cases when DOJ seeks dismissal, regardless of what jurisdiction they are in and what standard they apply. In any event, we will be watching carefully to see whether the Supreme Court strengthens—or weakens—DOJ’s ability to reign-in qui tam lawsuits.

B. SUPREME COURT LEAVES IT TO CIRCUIT COURTS TO DEVELOP PLEADING STANDARDS

1. Supreme Court Denial of Cert Regarding Circuit Split on Rule 9(b)

Another important Supreme Court decision regarding the FCA in the past six months was a decision not to act, as it denied petitions for certiorari in three cases addressing similar questions that the petitioner claimed would have provided clarity on the appropriate pleading standard under Rule 9(b) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure for claims brought under the FCA. See Johnson v. Bethany Hospice and Palliative Care LLC, 143 S. Ct. 351 (2022); Molina Healthcare of Illinois, Inc. v. Prose, 143 S. Ct. 352 (2022); United States ex rel. Owsley v. Fazzi Assocs., Inc., 143 S. Ct. 362 (2022).

Bethany Hospice, Molina, and Owsley all dealt with a similar issue: how much specificity must a plaintiff provide in a complaint in an FCA case to meet the standards for alleging fraud under Rule 9(b)? In Bethany Hospice, the Eleventh Circuit made clear that to satisfy Rule 9(b) “a complaint must allege actual submission of a false claim, and . . . it must do so with some indicia of reliability.” 853 F. App’x 496, 501 (11th Cir. 2021) (internal quotation marks omitted). The relators had alleged that the defendant—a company providing for-profit hospice care—ran an illegal referral scheme, paying remuneration to physicians who referred Medicare patients to the defendant’s facilities. Id. at 496. The Eleventh Circuit determined that the relators had not adequately alleged an FCA violation because they failed to allege any details about specific representative false claims. Id. at 501–03.

In Owsley, the Sixth Circuit likewise dismissed a complaint from a relator that the defendants had submitted false data to the government in relation to Medicare claims for home-healthcare because the relator had provided insufficient details to allow the defendants to discern which claims they submitted were allegedly false. 16 F.4th 192, 194 (6th Cir. 2021). In doing so, the Sixth Circuit articulated a similar standard as in Bethany Hospice, explaining that “under Rule 9(b), ‘[t]he identification of at least one false claim with specificity is an indispensable element of a complaint that alleges a False Claims Act violation.’” Id. at 196 (alteration in original) (citation omitted).

In Molina, the relator alleged that Molina—who contracted with Illinois’s state Medicaid program—submitted false claims to receive capitation payments from the state for skilled nursing facility services under an implied false certification theory. 17 F.4th 732, 736–39 (7th Cir. 2021). There, the Seventh Circuit set forth a different standard for satisfying Rule 9(b), allowing the relator to proceed past a motion to dismiss where the relator “provide[d] information that plausibly support[ed] the inference that” the defendant submitted a false claim, even without the details of a specific false claim. Id. at 741. Even without allegations about a specific false claim, the Seventh Circuit determined that the circumstantial evidence the relator alleged created an inference that the defendants had submitted false claims. Id.

The standards adopted by the various circuits under Rule 9(b) exist on a spectrum, ranging from the Eleventh Circuit and Sixth Circuit—which have held that details of a specific false claim are required (i.e., the who, what, when, where, and how of the alleged fraudulent submissions to the government)—to the Seventh Circuit (and others such as the Third, Fifth, Ninth, Tenth, and D.C. Circuits) which have held that Rule 9(b) may be satisfied if the relator makes specific factual allegations as to a scheme to defraud and facts constituting reliable indicia that false claims resulted from the scheme. In Bethany Hospice, Prose, and Owsley, the petitioners sought guidance from the Supreme Court on the proper standard courts should apply when evaluating FCA claims under Rule 9(b). By denying the petitions for writ of certiorari in Bethany Hospice, Prose, and Owsley, the Supreme Court has effectively declined to resolve this circuit split at the present juncture and as a result has left open the possibility that plaintiffs will forum‑shop for the most favorable pleading standard when pursuing FCA cases.

2. Circuit Courts Continue to Craft Pleading Standards Under Rule 9(b)

Absent guidance from the Supreme Court, circuit courts continue to craft their own standard under Rule 9(b) in FCA cases. Three recent examples are illustrative.

In Lanahan v. County of Cook, 41 F.4th 854 (7th Cir. 2022), the Seventh Circuit was tasked with applying Rule 9(b) to various allegations by a former employee of the Cook County Department of Public Health (CCDPH). Id. at 858. After the government declined to intervene, the relator alleged in a complaint that the CCDPH had received federal grants to implement various federal initiatives in Cook County. See id. at 858–60. The relator further alleged that in distributing and accounting for the funds, the CCDPH had failed to follow federal guidelines and regulations. Id. The district court dismissed a first amended complaint and second amended complaint from the relator, determining that the relator had failed to adequately allege that the CCDPH had made any false claims to the federal government and failed to adequately connect any allegedly false statements to government payments. Id. at 860–61.

The Seventh Circuit affirmed the district court’s dismissal with prejudice, explaining that the relator had provided no more than conclusory assertions that the CCDPH submitted false claims to the government. Id. at 862–64. According to the Seventh Circuit, a major flaw in the relator’s claims was that for each of the payments she alleges violated the FCA, she “object[ed] only to Cook County’s treatment of the funds after they were disbursed. The Second Amended Complaint is utterly silent as to the events leading up to Cook County’s receipt of these funds.” Id. at 862. And while the relator had provided slightly more detail as to CCDPH’s alleged misuse of one category of funds set to be used to support providing H1N1 vaccinations—by specifically alleging that CCDPH submitted falsified expense reports—these additional details were still not enough to satisfy Rule 9(b) because the relator did “not support this claim with particularized information about how . . . the expense reports [were] prepared.” Id. at 863. The Seventh Circuit further determined that the Relator had failed to allege adequate facts under Rule 9(b) to connect the allegedly false statements to the government payments. Id. at 864.

The Seventh Circuit had a further opportunity to provide guidance on the application of Rule 9(b) in United States ex rel. Sibley v. University of Chicago Medical Center, 44 F.4th 646 (7th Cir. 2022). While the federal and state governments elected not to intervene, the relators—former employees of jointly owned companies that deliver medical billing and debt collection services to healthcare providers—claimed their former employers (debt collection companies) and the healthcare provider those debt collection companies serviced had failed to follow federal regulations governing “bad debt.” Id. at 651. “Bad debts” are incurred when a Medicare patient fails to make required deductible or coinsurance payments and the provider makes sufficient efforts to collect the debt. Id. at 652 (citing 42 C.F.R. § 413.89). The provider may seek reimbursement from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) for those bad debts. 44 F.4th at 652. The relators alleged that the debt collection agencies and the healthcare provider had failed to follow the federal regulations for what constitutes bad debt in seeking reimbursements from CMS, and thus violated the FCA by failing to repay the government excess reimbursements received for bad debt. See id. at 652–655 The relators also alleged they had been retaliated against by the companies for reporting the alleged FCA violations. Id.

The district court dismissed all of the relators’ claims against the former employers and the healthcare provider for failure to adequately state a claim under Rule 9(b). Id. at 655. The Seventh Circuit affirmed the dismissal of most of the claims. The Seventh Circuit first explained that the complaint failed to allege that the healthcare provider had direct knowledge of the alleged excessive reimbursements—mere inferences and assumptions did not suffice to show knowledge. Id. at 657–58. Next, the court explained that for claims premised on the failure to repay the government for excessive bad debt reimbursements, the relators must provide “specific representative examples” of false claims. Id. at 659. According to the Sibley court, the relator failed to provide such representative examples for one of the debt collection companies and thus dismissal as to that company was appropriate. Id. In reaching this conclusion, the Sibley court appears to be at odds with the Seventh Circuit’s decision in Molina, in which the court noted that the plaintiff “provide[d] information that plausibly supports the inference that [the defendant] included false information” in submissions to the government, even without specific details of the submissions. 17 F.4th at 741. In Sibley, the Seventh Circuit went on to reverse the district court’s decision to dismiss the complaint against the other debt collection company because the relators had provided three specific examples of bad debt that was allegedly improperly reimbursed. 44 F.4th at 660. Finally, the Seventh Circuit also allowed the relators’ retaliation claims to proceed, making clear that those claims were governed by Rule 12(b)(6)’s pleading standard rather than the more stringent Rule 9(b) standard. Id. at 661–62.

The Fourth Circuit also addressed Rule 9(b)’s pleading standard in United States ex rel. Nicholson v. MedCom Carolinas, Inc., 42 F.4th 185 (4th Cir. 2022). In Nicholson, the federal government declined to intervene in a case involving allegations that the defendant—who contracted with the manufacturer of skin grafts to sell them to hospitals—paid its salespeople a commission for the skin grafts sold to federal healthcare providers, including Veterans Administration (VA) hospitals. Id. at 189. The relator then prosecuted the case. Id. According to the relator, selling the skin grafts to VA hospitals on commission resulted in a violation of the Anti-Kickback Scheme (AKS), which in turn led to a violation of the FCA. Id. The district court dismissed the relator’s complaint under Rule 9(b), determining it was almost entirely conclusory and provided no meaningful details to support the claims. Id.

The Fourth Circuit affirmed the district court’s dismissal. Id. at 200. The court explained that under Rule 9(b), the relator either had to provide a representative example of an alleged false claim (including the “time, place, and contents of the misrepresentation”) or make allegations sufficient to show that the defendant was engaged in “a pattern of conduct that would necessarily have led to the submission of false claims.” Id. at 194 (citations and internal quotation marks omitted). The Fourth Circuit concluded that the relator had not alleged either. Id. at 196. Specifically, while the relator had pled a specific false claim, the complaint lacked any details: “The patient is unknown . . ., who submitted the claim is unknown . . ., what VA hospital in what state is unknown . . . . The unknowns swamp the knowns.” Id. Given the bare‑bones details included in the complaint, the Court concluded it lacked the particularity required under Rule 9(b).

C. THE D.C. CIRCUIT APPLIES PRO TANTO APPROACH TO MULTI-DEFENDANT FCA CASE

In United States v. Honeywell International Inc., 47 F.4th 805 (D.C. Cir. 2022), the D.C. Circuit was faced with an unresolved damages-related question under the FCA, namely whether the statute provides, in multi-defendant cases, for an offset of previous settlement recoveries against a non-settling joint tortfeasor’s liability. Many FCA cases involve multiple defendants, in which those defendants are subject to joint and several liability. Honeywell clarified that in such cases, the pro tanto rule applies: proceeds from settlements with joint tortfeasor defendants should reduce the amounts owed by other, non-settling defendants—at least in regard to compensatory damages. However, the case left open whether civil penalties could qualify for such an off-set between joint tortfeasors in FCA cases.

The Honeywell appeal stemmed from a suit brought by the federal government against Honeywell, based on alleged FCA violations. According to the government, Honeywell had misrepresented the quality of a material it manufactured and provided to bulletproof vest manufacturers who eventually sold them to the government. According to the government, Honeywell had improperly represented that the material it sold to the manufacturers was the “best ballistic product in the market for ballistic resistance,” despite the fact that the materials degraded at high temperatures. Id. at 810. While the government’s suit against Honeywell was ongoing, the government settled with several other parties involved in manufacturing and supplying the vests to the federal government. Honeywell moved for summary judgment on the issue of damages, claiming that any damages assessed against it should be offset based on the settlements with the other parties. Honeywell “maintained the court should apply a pro tanto approach, reducing any common damages Honeywell owed by the amount of the settlements.” Id. at 811. The district court, however, adopted the proportionate share method for calculating damages advocated for by the government, which meant that “Honeywell would still be responsible for its proportionate share of the $35 million” in claimed damages. Id.

On appeal, the D.C. Circuit acknowledged that “[t]he FCA says nothing at all about how to address indivisible harms or whether joint and several liability is appropriate.” Id. at 813. Faced with crafting a common law rule, the D.C. Circuit determined that the “pro tanto rule . . . is not just compatible with the FCA; it is a better fit with the statute and the liability rules that have been partnered with it.” Id. at 817. The D.C. Circuit recognized that allowing for the pro tanto rule to be applied in FCA cases would mean that if settlements exceeded the damages claimed by the government, a defendant—like Honeywell—would potentially face no damages. But the D.C. Circuit still believed the pro tanto rule was “consistent with the FCA” because it left the “government in the driver’s seat to pursue and punish false claims according to its priorities.” Id. at 818. The D.C. Circuit’s decision represents the first circuit court decision on this issue and provides important reasoning for later courts that may be faced with determining how much settlements with third parties may offset damages against defendants in FCA cases. The case also will affect how defendants and the government answer the difficult question of how an individual defendant should value a potential settlement in a multi-defendant case. Defendants will have to decide whether to wait out resolutions with others that could reduce their own exposure, while the government will need to decide whether to reduce its settlement demands of earlier-settling parties in order to leave some amount of damages on the table to incentive later-in-time defendants to settle.

D. THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT CREATES A CIRCUIT SPLIT ON CAUSATION FOR AKS-PREDICATED FCA CLAIMS

The AKS imposes criminal liability on a person who knowingly and willfully pays, offers, solicits, or receives remuneration in return for referrals or orders of items or services reimbursed by federal health programs.[56] In 2010, Congress amended the AKS to provide that “a claim that includes items or services resulting from a violation of [the AKS] constitutes a false or fraudulent claim for purposes of [the FCA].” DOJ has long asserted the position that the term “resulting from” does not require a showing of causation; instead, DOJ asserts in AKS-based FCA cases that every claim that came later in time than the receipt of a kickback is “tainted” by the kickback and therefore is a false claim. In United States ex rel. Cairns v. D.S. Medical LLC, 2022 WL 2930946 (8th Cir. July 26, 2022), however, the Eighth Circuit held that the appropriate causation standard for AKS‑based FCA liability was “but for” causation. Cairns created a growing circuit split on the question of which claims “result from” an AKS violation. For example, in United States ex rel. Greenfield v. Medco Health Solutions, Inc., 880 F.3d 89, 98 (3d Cir. 2018), the Third Circuit, rejected both the “but for” causation standard and DOJ’s preferred “taint” theory, instead findings that the FCA and AKS “require[] the much looser standard of showing a link in the causal chain.” In Cairns, relators brought a qui tam action against a neurosurgeon, his practice, his fiancée, and the spinal implant company his fiancée owned, alleging a kickback scheme between the couple resulting in FCA violations. The relator alleged that a physician ordered spinal implants from his fiancée’s company—which allegedly received large commissions from the implant manufacturers—in exchange for an offer to purchase that company’s stock. The United States filed its own complaint as an intervenor. Cairns, 42 F.4th at 831–33. In a jury trial before the district court, the government argued that the 2010 amendment to the AKS created a loose FCA causation standard such that the alleged kickbacks would “taint” the claims and cause an FCA violation. See id. at 833–35. The district court issued jury instructions that the government could establish falsity if it showed “that the claim failed to disclose the Anti-Kickback Statute violation.” Id. at 834 (modifications omitted). The jury found for the government and the district court awarded damages and penalties in excess of five million dollars. Id. at 832. Defendants appealed, and the Eighth Circuit remanded. Id. On remand, the district court granted the government’s motion to dismiss its remaining claims without prejudice. Id. Defendants appealed again, arguing the lower court’s jury instructions were defective in failing to instruct the jury on but for causation. Id.

The Eighth Circuit agreed. In a noteworthy rejection of the government’s position, the Eighth Circuit held the plain meaning of the AKS required a showing of but for AKS-to-FCA causation— essentially, a showing that but for the alleged kickback, the FCA claim at issue would not have included the alleged kickback’s “items or services.” Id. at 836. The Eighth Circuit chiefly based its reasoning on the Supreme Court’s analysis of similar “results from” statutory language in the Controlled Substances Act in Burrage v. United States, 571 U.S. 204, 210–11 (2014). In Burrage, the Court reasoned that “results from” in the phrase “death or serious bodily injury results from the use of [the] substance” requires a showing of actual causality, or but for causation. Id. at 209 (citing 21 U.S.C. § 841(b)(1)(A)-(C)). Likewise, the Eighth Circuit reasoned in Cairns that the plain meaning of “resulting from” was “unambiguously causal,” rejecting the government’s arguments that causation could be shown where the kickback “tainted” the claim or was a “contributing factor.” Cairns, 42 F.4th at 835–36. The alternative standards were “hardly causal at all” – a “‘taint’ could occur without the illegal kickbacks motivating the inclusion of any of the ‘items or services’” and “asking the jury if a violation ‘may have been a contributing factor’ does not establish anything more than a mere possibility.” Id. at 835. Worst of all, the Eighth Circuit added, was the district court’s instruction that “may have been the least causal of all: just because a claim fails to disclose an anti-kickback violation does not mean that there is a connection between the violation and the included ‘items or services.’” Id. The Eighth Circuit explained that, “[w]here there is no textual or contextual indication to the contrary, courts regularly read phrases like ‘results from’ to require but-for causality.” Id. (citation omitted).

E. THE FOURTH AND NINTH CIRCUITS ISSUE DECISIONS ON THE SCIENTER REQUIRED UNDER THE FCA

In United States ex rel. Hartpence v. Kinetic Concepts, Inc., 44 F. 4th 838 (9th Cir. 2022), the Ninth Circuit confronted the FCA’s scienter requirement. A relator alleged that a wound care medical device manufacturer and its subsidiary falsely certified compliance with Medicare payment rules about the use of the medical devices. Id. at 841, 844–45. The United States declined to intervene. Id. at 844–45. The relator claimed that the defendants fraudulently certified compliance with Medicare reimbursement criteria that required that the medical records of patients who used the devices reflect “progressive wound healing” for each month for which claims were submitted. Id. at 841. The relator alleged that the defendants manipulated their billing codes to falsely certify compliance during “stalled cycles” of months without healing, where healing resumed the next month. Id. at 844–45.

The district court granted summary judgment in favor of the defendants, holding that relator had not brought sufficient evidence that the defendants’ false certifications were material to the Medicare reimbursements or that the defendants had knowingly used the billing codes as alleged. Id. at 845. The relator appealed. Id.

The Ninth Circuit reversed, holding that the district court erred in so ruling because the relator produced enough evidence to raise a triable issue of fact regarding the requisite scienter. Id. at 850–53. The court explained that based on the relator’s evidence, a jury could find that the defendants deliberately miscoded claims to conceal them and knew those coded certifications were false for two reasons. Id. at 851. First, the relator put forth evidence, in the form of the defendants’ internal communications, that suggested the defendants deliberately used the codes fraudulently to skirt claim appeals and denials. Second, the relator brought evidence both of the defendants’ employees raising concerns internally about the billing and of Medicare contractors correcting defendants’ application of the billing codes. Id. Although the defendants did not automatically accept coded claims as true, there was email communication evidence in the record that they were “plainly aware that using the [] modifier avoided a costly review and appeals process that it would sometimes win and sometimes lose.” Id. That evidence – which the court suggested showed the defendants deliberately avoided digging into the validity of claim modifiers – provided “ample evidence to permit a rational trier of fact to conclude that [the defendants] knew that it was a false statement . . . and that [the defendants] did so knowing that it might thereby escape case-specific scrutiny.” Id. at 851–52.

An en banc Fourth Circuit examined the FCA’s scienter element in United States ex rel. Sheldon v. Allergan Sales, LLC, 24 F.4th 340 (4th Cir. 2022), vacated en banc, 49 F.4th 873 (4th Cir. 2022). The relator alleged that the drug manufacturer falsely represented its drugs’ “best price” under the Medicaid drug rebate program by purportedly failing to aggregate discounts given to separate customers. Id. at 346. The government declined to intervene. Id. The district court granted the manufacturer’s motion to dismiss, holding that the relator had “failed to plead both that the claims at issue were false and that [the manufacturer] had made them knowingly.” Id. at 346–47.

In Sheldon, the divided Fourth Circuit panel joined the growing number of circuits to address the Supreme Court’s Safeco scienter standard in FCA cases. Id. at 347. The court noted the difficulty of applying the vague “knowledge” standard set forth in the FCA. The court held that “a defendant cannot act ‘knowingly’ if it bases its actions on an objectively reasonable interpretation of the relevant statute when it has not been warned away from that interpretation by authoritative guidance” – an “objective standard” that precludes inquiry into a defendant’s subjective intent. Id. at 348. However, shortly after oral argument and in a per curiam order on rehearing en banc, the full Fourth Circuit vacated the panel opinion and affirmed the district court. United States ex rel. Sheldon v. Allergan Sales, LLC, 49 F.4th 873, 874 (4th Cir. 2022).

F. THE NINTH AND FOURTH CIRCUITS ADDRESS THE BOUNDS OF THE PUBLIC DISCLOSURE BAR

In United States ex rel. Silbersher v. Allergan, Inc. et al., 46 F.4th 991 (9th Cir. 2022), the Ninth Circuit considered the FCA’s “public disclosure bar,” which directs a district court to dismiss an action under the FCA when “substantially the same allegations or transactions” have previously been publicly disclosed, unless the relator is an “original source of the information.” 31 U.S.C. § 3730(e)(4)(A). In a qui tam action, a patent attorney alleged that the defendant drug companies had improperly obtained patents to protect two of their drugs from generic competition. Id. at 993. The government declined to intervene. Id. The district court denied the defendants’ motion to dismiss, and Defendants appealed.