March 15, 2018

In 2017, several Latin American countries stepped up enforcement and legislative efforts to address corruption in the region. Enforcement activity regarding alleged bribery schemes involving construction conglomerate Odebrecht rippled across Latin America’s business and political environments during the year, with allegations stemming from Brazil’s ongoing Operation Car Wash investigation leading to prosecutions in neighboring countries. Simultaneously, governments in Latin America have made efforts to strengthen legislative regimes to combat corruption, including expanding liability provisions targeting foreign companies and private individuals. This update focuses on five Latin American countries (Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, Colombia, and Peru) that have ramped up anti-corruption enforcement or passed legislation expanding anti-corruption legal regimes.[1] New laws in the region, coupled with potentially renewed prosecutorial vigor to enforce them, make it imperative for companies operating in Latin America to have robust compliance programs, as well as vigilance regarding enforcement trends impacting their industries.

1. Mexico

Notable Enforcement Actions and Investigations

In 2017, Petróleos Mexicanos (“Pemex”) disclosed that Mexico’s Ministry of the Public Function (SFP) initiated eight administrative sanctions proceedings in connection with contract irregularities involving Odebrecht affiliates.[2] The inquiries stem from a 2016 Odebrecht deferred prosecution agreement (“DPA”) with the U.S. Department of Justice (“DOJ”).[3] According to the DPA, Odebrecht made corrupt payments totaling $10.5 million USD to Mexican government officials between 2010 and 2014 to secure public contracts.[4] In September 2017, Mexico’s SFP released a statement noting the agency had identified $119 million pesos (approx. $6.7 million USD) in administrative irregularities involving a Pemex public servant and a contract with an Odebrecht subsidiary.[5]

In December 2017, Mexican law enforcement authorities arrested a former high-level official in the political party of Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto.[6] The former official, Alejandro Gutiérrez, allegedly participated in a broad scheme to funnel public funds to political parties.[7] While the inquiry has not yet enveloped the private sector like Brazil’s Operation Car Wash investigation, the prosecution could signal a new willingness from Mexican authorities to take on large-scale corruption cases. The allegations are also notable due to their similarity to the allegations in Brazil’s Car Wash investigation. In both inquiries, funds were allegedly embezzled from state coffers for the benefit of political party campaigns.

Legislative Update

Mexico’s General Law of Administrative Responsibility (“GLAR”)—an anti-corruption law that provides for administrative liability for corporate misconduct—took effect on July 19, 2017. The GLAR establishes administrative penalties for improper payments to government officials, bid rigging in public procurement processes, the use of undue influence, and other corrupt acts.[8] The law reinforces a series of Mexican legal reforms from 2016 that expanded the scope of the country’s existing anti-corruption laws and created a new anti-corruption enforcement regime encompassing federal, state, and municipal levels of government. Among the GLAR’s most significant changes are provisions that target corrupt activities by corporate entities and create incentives for companies to implement compliance programs to avoid or minimize corporate liability.

The GLAR applies to all Mexican public officials who commit what the law calls “non-serious” and “serious” administrative offenses.[9] Non-serious administrative offenses include the failure to uphold certain responsibilities of public officials, as defined by the GLAR (e.g., cooperating with judicial and administrative proceedings, reporting misconduct, etc.).[10] Serious administrative offenses include accepting (or demanding) bribes, embezzling public funds, and committing other corrupt acts, as defined by the GLAR.[11] The GLAR also applies to private persons (companies and individuals) who commit acts considered to be “linked to serious administrative offenses.”[12] These offenses include the following:

- Bribery of a public official (directly or through third parties)[13];

- Participation in any federal, state, or municipal administrative proceedings from which the person has been banned for past misconduct[14];

- The use of economic or political power (be it actual or apparent) over any public servant to obtain a benefit or advantage, or to cause injury to any other person or public official[15];

- The use of false information to obtain an approval, benefit, or advantage, or to cause damage to another person or public servant[16];

- Misuse and misappropriation of public resources, including material, human, and financial resources[17];

- The hiring of former public officials who were in office the prior year, acquired confidential information through their prior employment, and give the contractor a benefit in the market and an advantage against competitors[18]; and

- Collusion with one or more private parties in connection with obtaining improper benefits or advantages in federal, state, or municipal public contracting processes.[19] Notably, the collusion provisions apply extraterritorially and ban coordination in “international commercial transactions” involving federal, state, or municipal public contracting processes abroad.[20]

The GLAR provides administrative penalties for violations committed by both physical persons and legal entities. Physical persons who violate the GLAR can be subjected to: (1) economic sanctions (up to two times the benefit obtained, or up to approximately $597,000 USD)[21]; (2) preclusion from participating in public procurements and projects (for a maximum of eight years)[22]; and/or (3) liability for any damages incurred by any affected public entities or governments.[23]

Legal entities, on the other hand, can be fined up to twice the benefit obtained, or up to approximately $5,970,000 USD, precluded from participating in public procurements for up to ten years, and held liable for damages.[24] The GLAR also creates two additional penalties for legal entities: suspension of activities within the country for up to three years, and dissolution.[25] Article 81 limits the ability to enforce these two stiffer penalties to situations where (1) there was an economic benefit and the administration, compliance department, or partners were involved, or (2) the company committed the prohibited conduct in a systemic fashion.[26] The GLAR’s penalties for physical and legal persons are administrative, rather than criminal.

Under Article 25 of the GLAR, Mexican authorities can take into account a company’s robust compliance “Integrity Program” in determining and potentially mitigating corporate liability under the GLAR.[27] The law requires the Integrity Program to have several elements, including clearly written policies and adequate review, training, and reporting systems.[28]

The GLAR contains a self-reporting incentive that provides for up to a seventy percent reduction of penalties for those who report past or ongoing misconduct to an investigative authority.[29] As previously noted, the GLAR’s non-monetary sanctions include preclusion from participating in public procurements and projects for up to eight years (for physical persons) or ten years (for companies).[30] If a person subject to a preclusion sanction self-reports GLAR violations, the preclusion sanction can be reduced or completely lifted by the Mexican authorities.[31] Requirements for obtaining a reduction of penalties through self-reporting include: (1) involvement in an alleged GLAR infraction and being the first to contribute information that proves the existence of misconduct and who committed the violations; (2) refraining from notifying other suspects that an administrative responsibility action has been initiated; (3) full and ongoing cooperation with the investigative authorities; and (4) suspension of any further participation in the alleged infraction.[32]

Notably, other participants in the alleged misconduct who might be the second (or later) to disclose information could receive up to a fifty percent penalty reduction, provided that they also comply with the above requirements.[33] If a party confesses information to the investigative authorities after an administrative action has already begun, that party could potentially receive a thirty percent reduction of penalties.[34]

For a full analysis of the GLAR, see https://www.gibsondunn.com/mexicos-new-general-law-of-administrative-responsibility-targets-corrupt-activities-by-corporate-entities/.

2. Brazil

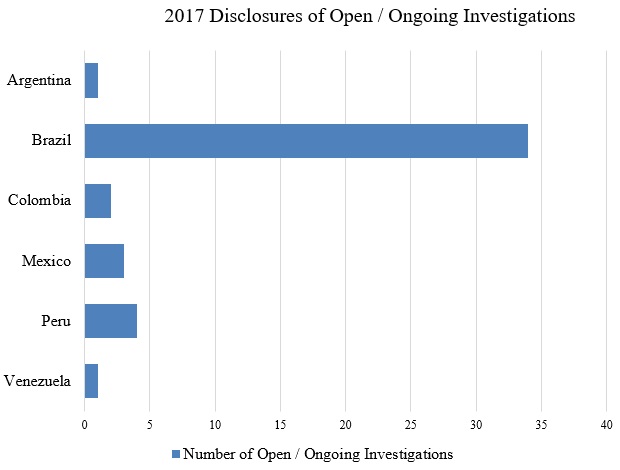

Following the success of the massive Operation Car Wash investigation into corruption involving the country’s energy sector, Brazilian regulators launched or advanced inquiries in 2017 impacting companies in the healthcare, meatpacking, and financial industries, among others. Brazilian authorities have also continued to garner international accolades for their anti-corruption work, with Brazil’s federal prosecution service (“Ministério Público Federal” or “MPF”) winning Global Investigation Review’s “Enforcement Agency or Prosecutor of the Year” award for its 2017 Operation Car Wash efforts.[35] This award follows a 2016 recognition of the Car Wash Taskforce by Transparency International.[36] The robust enforcement environment in Brazil is also reflected in this year’s public company disclosures. In 2017, thirty-four companies disclosed information regarding new or ongoing inquiries involving Brazil, while disclosures regarding other Latin American nations numbered in the single digits.[37]

Notable Enforcement Actions and Investigations

A. Operation Car Wash (Operação Lava Jato)

Operation Car Wash, the multi-year investigation into allegations of corruption related to contracts with state-owned oil company Petrobras, has remained a focus area for the Brazilian authorities. The investigation opened four new phases in 2017. Notably, in October 2017, Judge Sergio Moro—the lead jurist for the investigation—stated at a public event that the Car Wash inquiry was “moving toward the final phase.”[38] Judge Moro did not, however, provide a potential date for closing the investigation, stating, “a good part of the work is done, but this does not mean that work does not remain.”[39] To date, Brazilian authorities investigating the Car Wash allegations have obtained 177 convictions, with sentences totaling more than 1,750 years in prison.[40]

B. Operation Zealots (Operação Zelotes)

In 2017, Brazilian authorities launched new phases of Operation Zealots, a multi-year investigation into alleged payments to members of Brazil’s Administrative Board of Tax Appeals.[41] The investigation began as an inquiry into one of the largest alleged tax evasion schemes in the country’s history. Large companies and banks, including Bradesco, Santander, and Safra, allegedly paid bribes to members of the appeals board in exchange for a reduction or waiver of taxes owed.[42] Operation Zealots was launched in 2015 and initially implicated companies in the financial sector. The scope of the investigation has expanded in the last two years to also reach companies in the automobile sector and a Brazilian steel distributor.[43] Notably, in 2017, a criminal complaint was filed against former Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva alleging that he received payments in exchange for securing tax benefits for automobile companies.[44] The total amount of evaded taxes through various alleged Operation Zealots schemes is estimated to reach nearly $19 billion BRL (approx. $5.8 billion USD).[45]

C. Operation Weak Flesh (Operação Carne Fraca)

In early 2017, the Brazilian Federal Police launched an investigation into the alleged bribery of government food sanitation inspectors called Operation Weak Flesh.[46] The operation was reported to be one of the largest in the history of the Federal Police, with Brazilian authorities executing 194 search-and-seizure warrants.[47] Dozens of inspectors are accused of taking bribes in exchange for allowing the sale of rancid products, falsifying export documents, overlooking illicit additives, and failing to inspect meatpacking plants.[48] Authorities are investigating more than thirty meatprocessing companies, including giants such as JBS S.A. and BRF S.A.

D. Operation Bullish (Operação Bullish)

On May 12, 2017, the Federal Police launched Operation Bullish, an investigation into fraud and irregularities in the manner by which Brazil’s National Bank for Economic and Social Development approved investments of over $8 billion BRL (approx. $2.4 billion USD) for the expansion of the Brazilian meatpacking company JBS.[49] While JBS claims that it did not receive any favors from the bank’s investment arm (“BNDESPar”), Brazil’s Federal Court of Accounts (“TCU”) claims that the bank approved “risky” investments for JBS with inadequate time for analysis.[50] The Federal Police further claim that although BNDESPar approved funds for a JBS acquisition of a foreign company, the acquisition never occurred and the investment funds were never returned.[51]

E. Operation Mister Hyde (Operação Mister Hyde)

Brazilian authorities also continued inquiries in the healthcare space as part of a multi-year investigation into an alleged “Prosthetics Mafia” of doctors and medical instrument suppliers that rigged the bidding process for surgical supplies. Investigators alleged that in exchange for payments, doctors would identify patients for unnecessary surgeries and ensure that the surgical instruments used in the operations came from a specified provider.[52] The inquiry stems from a 2015 congressional investigation. In February 2017, it was reported that three employees from one of the companies under investigation, TM Medical, agreed to plea bargains with the federal authorities.[53]

Settlements and Leniency Agreements

UTC Engenharia. In July 2017, UTC Engenharia signed a leniency agreement with the Brazilian government and agreed to pay $574 million BRL (approx. $175 million USD), including a fine, damages, and unjust enrichment.[54] UTC signed the agreement with Brazil’s Comptroller General of the Union (“CGU”) and Brazil’s Federal Attorney General’s Office.[55] Under the agreement, UTC must adopt an integrity program and pay its fine within twenty-two years.[56]

According to the Brazilian government, the agreement reflects “the basic pillars enumerated by the two federal agencies in the negotiations, that is, speed in obtaining evidence, identification of others involved in the crimes, cooperation with investigations, and commitment to the implementation of effective integrity mechanisms.”[57] Notably, according to the press release, the implementation of UTC’s integrity program “will be monitored by the CGU, which can perform inspections at the company and request access to any documents and information necessary.”[58]

Rolls-Royce plc. In January 2017, Rolls-Royce settled allegations that the company offered, paid, or failed to prevent bribes involving the sale of engines, energy systems, and related services in Brazil and five other foreign jurisdictions.[59] According to charging documents, between 2003 and 2013, Rolls-Royce allegedly made commission payments to an intermediary while knowing that portions of the payments would be paid to officials at Brazil’s state-owned oil company Petrobras.[60] Rolls-Royce’s intermediary allegedly made more than $1.6 million BRL (approx. $485,700 USD) in corrupt payments to obtain contracts for supplying equipment and long-term service agreements.[61] As a part of a global settlement with DOJ, Britain’s Serious Fraud Office, and Brazil’s Ministério Público Federal, Rolls-Royce agreed to pay $800 million USD total, with $25.5 million USD of that settlement being paid to the Brazilian authorities.[62]

SBM Offshore N.V. In November 2017, SBM settled allegations with DOJ that the company made payments to foreign officials in Brazil, Angola, Equatorial Guinea, Kazakhstan, and Iraq.[63] According to the DPA, SBM used a sales agent to provide payments and hospitalities to Petrobras executives to secure an improper advantage in business with the state-owned company.[64] SBM agreed to pay a $238 million USD criminal fine.[65] DOJ took into account overlapping conduct prosecuted by other jurisdictions when calculating SBM’s fine, including the company’s ongoing negotiations with the MPF and a $240 million USD settlement with the Dutch authorities.[66] The government’s press release also stated that DOJ was “grateful to Brazil’s MPF” and authorities in the Netherlands and Switzerland “for providing substantial assistance in gathering evidence during [the] investigation.”[67]

Braskem/Odebrecht. In December 2016, Brazilian construction conglomerate Odebrecht and its petrochemical production subsidiary, Braskem, resolved bribery charges with authorities in Brazil, Switzerland, and the United States.[68] At the time of the 2016 settlement, the DOJ/SEC segment of the multibillion-dollar resolution was $419 million USD. The settlement agreement did note, however, that Odebrecht represented it could pay no more than $2.6 billion USD in penalties.[69] The agreement further noted that the Brazilian and U.S. authorities would conduct an independent analysis of Odebrecht’s representation.[70] According to an April 2017 sentencing memorandum filed with the court, the U.S. and Brazilian authorities analyzed Odebrecht’s ability to pay the proposed penalty and determined that Odebrecht was indeed unable to pay a total criminal penalty in excess of $2.6 billion USD.[71] The sentencing memorandum noted the parties agreed that Odebrecht would therefore pay a reduced fine of $93 million USD to the U.S. government.[72]

Legislative Updates and Agency Guidance

State-Level Anti-Corruption Law. In late 2017, the state of Rio de Janeiro passed an anti-corruption law requiring companies contracting with the state to have compliance programs.[73] The law applies to companies and individuals, including foreign companies with “headquarters, subsidiaries, or representation in Brazil.”[74] While the Clean Company Act takes a company’s compliance program into consideration in the application of sanctions, Rio de Janeiro’s law goes one step further and requires companies to have programs in place before contracting with the state.[75]

Ten Measures Against Corruption. An initiative from Brazil’s Ministério Público Federal to strengthen anti-corruption laws has yet to pass both houses of Brazil’s legislative branch. The initiative—called the “Ten Measures Against Corruption”—was first announced by the MPF in 2015.[76] The proposal was introduced to Congress as a public initiative in 2016 after it received more than 1.7 million signatures of support from the public.[77] The measures propose changes in corruption laws and criminal proceedings that would make the judiciary and prosecutor’s office more transparent, criminalize unjust enrichment of civil servants, hold political parties liable for accepting undeclared donations, and increase penalties for corrupt acts.[78] Consideration of the proposal was halted in the Senate in 2017 after public outrage in response to the lower Congress’s addition of a provision that would impose harsh penalties on the judiciary and federal prosecutors for “abuse of authority.”[79] Operation Car Wash prosecutor Deltan Dallagnol claimed that the House’s amendments “favored” white collar crimes and undermined the proposal’s purpose.[80]

Ministério Público Federal Leniency Agreement Guidance. In August 2017, the Ministério Público Federal issued guidance for prosecutors negotiating leniency agreements.[81] The guidance provides insights into the process Brazil’s prosecutors use for negotiating such agreements and the expectations for collaborators. One section of the guidance, for example, states that negotiations should be conducted by “more than one member of the MPF” and preferably by a criminal and administrative prosecutor for the agency.[82] The guidance also notes the possibility that the negotiations could take place together with other Brazilian authorities, including the CGU [the chief regulator of the Clean Company Act], the Federal Attorney General’s Office (“AGU”), the chief anti-trust regulator, and the TCU.[83] The guidance also notably details obligations of collaborators in leniency agreements, including:

- Communicating relevant information and proof (time frames, locations, etc.);

- Ceasing illicit conduct;

- Implementing a compliance program and submitting to external audit, at the company’s expense;

- Collaborating fully with the investigations during the life of the agreement and always acting with honesty, loyalty, and good faith, without reservation;

- Paying applicable fines and damages; and

- Declaring that all information supplied is correct and accurate, under the penalty of rescission of the leniency agreement.[84]

3. Argentina

Notable Enforcement Actions and Investigations

A. Investigation into President Mauricio Macri

Beginning in 2016 and continuing throughout 2017, federal prosecutors in Argentina launched investigations concerning current President Mauricio Macri.[85] While Macri was elected on promises to combat corruption in Argentina,[86] his family’s extensive business holdings have been scrutinized by Argentine authorities in connection with various influence trafficking and money laundering probes.[87] An investigation opened in April 2017, for example, focuses on the grant of airline routes to a company connected to Macri’s father.[88] Argentine prosecutors are also probing allegations that a government official received payments from construction conglomerate Odebrecht in connection with renewing a public contract.[89] At the time of the alleged payments, Odebrecht was a participant in a consortium with a company connected to Macri’s cousin.[90]

B. Investigation into Former President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner

In April 2017, former President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner was indicted in connection with allegations that she led a scheme to launder funds misappropriated from public coffers through a family-owned business.[91] The charges represent the second indictment filed against Kirchner since she left office more than two years ago.[92] In December 2016, charges were brought against Kirchner alleging that she led a criminal organization that attempted to illegally benefit its members by awarding public contracts to construction company Austral Construcciones.[93] In a separate investigation, a judge ordered Kirchner’s arrest in connection with allegations that she covered up possible Iranian involvement in the 1994 bombing of a Jewish community center in Buenos Aires in exchange for a potentially lucrative trade deal.[94] Other former high-level employees in Kirchner’s government have been arrested for unjust enrichment, including Vice President Amado Boudou and former planning minister Julio de Vido.[95]

Legislative Update

In November 2017, Argentina’s Congress passed new legislation imposing criminal liability on corporations for bribery (national and transnational), influence peddling, unjust enrichment of public officials, falsifying balance sheets and reports, and other designated offenses.[96] The bill, called the Law on Corporate Criminal Liability, applies to both Argentine and multinational companies domiciled in the country.[97] The law went into effect on March 1, 2018.[98]

Under the bill, legal entities can be held liable for bribery and other misconduct carried out directly or indirectly, with the company’s intervention, or in the company’s name, interest, or benefit.[99] Legal entities can also be held liable if the company ratifies the initially unauthorized actions of a third party.[100] The bill states that legal entities are not held liable, however, if the physical person who committed the misconduct acted “for his exclusive benefit, and without providing any advantage” for the company.[101] The bill also imposes successor liability on parent companies in mergers, acquisitions, and other corporate restructurings.[102] The bill applies to transnational bribery for acts committed by Argentine citizens and entities that are domiciled in Argentina.[103]

The bill imposes monetary and non-monetary sanctions, including:

- Monetary fines from two to five times the benefit that was (or could have been) obtained by the company,[104]

- Complete or partial suspension of activities for up to ten years,[105]

- Suspension for up to ten years from participating in public bids, contracts, or any other activity linked to the state,[106] and

- Dissolution and liquidation of the corporate person when the entity was created solely for the purposes of committing misconduct, or when misconduct constituted the principal activities of the entity.[107]

Legal entities can be exempted from criminal liability where the company (1) self-reported misconduct detected through its own efforts and internal investigation, (2) implemented an adequate internal control and compliance system before the misconduct occurred, and (3) returned undue benefits obtained through the misconduct.[108] The bill also contains provisions allowing for Argentina’s public prosecutor’s office, the Ministério Público Fiscal, to enter into collaboration agreements with legal entities.[109] The agreements require legal entities to provide information regarding the misconduct, pay the equivalent of half the minimum monetary fine imposed under the law, and comply with other conditions of the agreement (including, but not limited to, implementing a compliance program).[110]

Minimal requirements for compliance programs consistent with the bill include:

- A code of ethics or conduct, or the existence of integrity policies and procedures applicable to all directors, administrators, and employees that prevent the commission of the crimes contemplated by the law,[111]

- Specific rules and procedures to prevent wrongdoing in the context of tenders and bidding processes in the execution of administrative contracts, or in any other interaction with the public sector,[112] and

- Periodic trainings on the compliance program for directors, administrators, and employees.[113]

The law also notes that a compliance program may include additional elements, including, among others:

- Periodic risk assessments,[114]

- Visible and unequivocal support of the program from upper management,[115]

- Misconduct-reporting channels that are open to third parties and adequately defined,[116]

- Anti-retaliation policies,[117]

- Internal investigation systems,[118]

- Due diligence processes for M&A transactions,[119]

- Monitoring and evaluation of the effectiveness of the compliance program,[120] and

- Designation of an employee responsible for the coordination and implementation of the program.[121]

The compliance program components listed in the law are notably similar to elements of effective compliance programs delineated by DOJ, the SEC, and Mexico’s General Law of Administrative Responsibility.[122]

4. Colombia

Notable Enforcement Actions and Investigations

A. Odebrecht Fallout

According to a December 2016 deferred prosecution agreement with DOJ, Odebrecht made more than $11 million USD in corrupt payments to government officials in Colombia to secure public works contracts.[123] In the wake of this settlement with U.S. authorities and Brazil’s multi-year investigation into Odebrecht’s dealings, Colombian prosecutors have announced inquiries into congressional involvement in the allegations and have arrested former Colombian senator Otto Bula for allegedly taking $4.6 million USD in bribes from the company.[124] Odebrecht allegedly paid Bula to ensure that a contract for the construction of the Ocaña-Gamarra highway included higher-priced tolls that would benefit the company.[125] Odebrecht also allegedly made $6.5 million USD in payments to former Vice Minister of Transportation Gabriel García Morales in exchange for a contract to construct a section of the Ruta del Sol highway.[126]

B. Reficar Oil Refinery

In 2017, Colombian authorities brought corruption charges against executives from an American engineering firm, Chicago Bridge & Iron Company (“CB&I”), in connection with the Refineria de Cartagena (“Reficar”) oil refinery.[127] The Reficar oil refinery is a subsidiary of Colombia’s state-owned oil company, Ecopetrol. Colombian authorities charged CB&I and Reficar executives with various corruption charges, including unjust enrichment, misappropriation of funds, and embezzlement.[128] According to the Colombian authorities, Reficar executives directed contracts to CB&I without abiding by legal requirements for public bidding.[129] The Colombian authorities also claimed to have discovered irregularities with payments CB&I received in connection with Reficar contracts, including payments for work that was not performed, reimbursements for extravagant expenses unrelated to the refinery project, and double billing.[130]

C. Conviction of Former Anti-Corruption Chief Luis Gustavo Moreno

On June 27, 2017, former anti-corruption chief Luis Gustavo Moreno was arrested in his office by the CTI (the Technical Investigation Team, a division of the Colombian Attorney General). They charged him with soliciting bribes in return for interfering with anti-corruption investigations into Alejandro Lyons Muskus, ex-governor of Córdoba, with the possibility of ending such investigations. After his arrest, Moreno turned into a key collaborator with various officials, shedding light on a massive corruption scandal in the judiciary and congressional branch. According to Moreno, the scandal involved state politicians such as Musa Besaile Fayad and Bernardo “Ñoño” Elías, while also accusing judges such as Gustavo Malo Fernández, Francisco José Ricaurte, and Leónidas Bustos of accepting bribes in order to corrupt judicial proceedings.[131] President Juan Manuel Santos signed extradition orders for Moreno and extradited him to Florida, where DOJ officials charged him with conspiracy to launder money with the intent to promote foreign bribery.[132]

Legislative Update

In 2017, Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos announced a series of measures to address corruption issues in the country.[133] The announcement followed Colombia’s 2016 passage of its first foreign bribery statute, the Transnational Corruption Act (“TCA”).[134] The TCA notably has extraterritorial effect and holds legal entities administratively liable for improper payments to foreign government officials made by the entity’s employees, officers, directors, subsidiaries, contractors, or associates.[135] The new anti-corruption measures announced by President Santos, among others, include passing new laws that would provide labor protections and economic incentives for whistleblowers, require that companies disclose information regarding “the persons who in reality profit from a business or company,” and eliminate the use of house arrest for corruption cases.[136] The President also proposed creating a group of judges who specialize in anti-corruption cases.[137] Other corruption reforms considered by Colombia’s Congress in 2017 include requiring lobbyists to disclose meetings with public officials and the creation of a registry of beneficiaries of public contracts.[138]

Transnational Cooperation

In 2017, Colombia’s Superintendence of Corporations and the Peruvian Ministry entered into a Memorandum of Understanding (“MOU”) to prosecute international corruption.[139] The goal of the MOU is to help investigate corruption in Peru and Colombia by focusing on a bilateral exchange of evidence between the two countries.[140] Colombia signed a similar agreement with Spain in 2017.[141] These new efforts are meant to assist partnering states in overcoming the difficulties of cross-border investigations, including the need to acquire evidence in foreign territories.

5. Peru

Notable Enforcement Actions and Investigations

The Odebrecht scandal has significantly impacted the political and anti-corruption landscape in Peru. In its settlement with Odebrecht, DOJ disclosed that Odebrecht executives admitted to funneling around $29 million USD in bribes to Peruvian government officials between 2004 and 2015.[142] Government officials announced that Odebrecht and other companies involved in corruption would no longer be able to bid on public work contracts.[143] This marked the end of Odebrecht’s four-decade run as a successful bidder on public work projects in Peru.[144] The government will now decide on a case-by-case basis what to do with the remaining contracts awarded to Odebrecht.[145]

Three of Peru’s recent former presidents have been arrested and/or accused of crimes related to corruption, all with some alleged connection to Odebrecht.[146] In July 2017, a Peruvian judge ordered the arrest of former President Ollanta Humala and his wife on charges of money laundering and conspiracy related to the alleged receipt of a $3 million USD bribe from Odebrecht.[147] Humala, who has continued to maintain his innocence, became the first former head of state detained in connection with the Odebrecht scandal.[148] Prosecutors are also investigating former President Alan Garcia, who allegedly facilitated irregular bidding on the subway in Lima.[149]

Another former president, Alejandro Toledo, was ordered arrested by a Peruvian judge in February, pursuant to accusations that he had received $20 million USD in bribes from Odebrecht in connection with bidding on the Interoceanic Highway between Brazil and Peru. Toledo has remained in the United States and denied any wrongdoing.[150] A formal extradition request to the United States for Toledo to return to Peru and face charges for the alleged bribe is near approval on the Peruvian side.[151]

Even Peru’s current president, Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, has been unable to evade implication in the ever-expanding Odebrecht probe. Earlier in 2017, he had to testify as a witness in the same investigation implicating former President Toledo in the alleged irregular bidding process to build the Interoceanic Highway.[152] In November 2017, former Odebrecht CEO Marcelo Odebrecht told Brazilian prosecutors that Odebrecht hired Kuczynski as a consultant after he had opposed highway contracts granted to the company.[153] Kuczynski denied the allegations, but subsequently documents showed Kuczynski may have received $782,000 in payments from Odebrecht through his investment banking firm, Westfield Capital.[154] Kuczynski narrowly survived an impeachment vote based on the corruption allegations in late December 2017.[155] Recent additional testimony from an Odebrecht official purporting to confirm impropriety in Kuczynski’s relationship with Odebrecht has renewed calls for Kuczynski to step down or be impeached.[156]

On a regional and local level in Peru, several governors have been under investigation or accused of corruption.[157] Remarkably, a May 2014 study by Peru’s office of the anti-corruption solicitor reported that a significant majority of mayors in office between 2011 and 2014 in Peru had been investigated for criminal activity.[158]

Legislative Update

The most significant development in anti-corruption legislation in Peru over the last year was Legislative Decree No. 1352, enacted on January 6, 2017. This decree modifies Law No. 30424 (Law Regulating Administrative Liability of Legal Entities for the Commission of Active Transnational Bribery),[159] which was enacted in 2016 to declare that legal entities, including corporations, would be autonomously and administratively liable for active transnational bribery when it was committed in their name or for them and on their behalf.[160] Decree No. 1352 extended the administrative and autonomous liability of legal entities to include those guilty of active bribery of public officials.[161] The liability provided for in Decree No. 1352 is termed “autonomous” because a natural person does not have to be found liable first; the Decree’s charges now create independent liability, and an independent entity like a corporation can be charged separately.[162] The law provides for autonomous liability for certain crimes of bribery and money laundering.[163]

Parent companies are not liable for penalties under the autonomous liability provisions of Decree No. 1352 unless the employees who engaged in corruption or money laundering did so with specific consent or authorization from the parent company.[164] Additionally, companies that acquire entities found guilty of corruption under the autonomous liability provision may not be separately penalized if the acquiring company used proper due diligence, defined as taking reasonable actions to verify that no autonomous liability crimes had been committed.[165] Finally, entities can avoid autonomous liability by implementing a sufficient criminal law compliance program designed to prevent such crimes of corruption from being committed on behalf of the company.[166] Elements of a properly designed program include: an autonomous person in charge of the compliance program, proper implementation of complaint procedures, continuous monitoring of the program, and training for those involved.[167] The Peruvian securities regulator had promised additional guidance before January 1, 2018—when the Decree took effect—but, as of the date of this publication, no such guidance has been issued.[168]

The Peruvian government has also modified the procurement laws via Decree 1341 to ban any company with representatives who have been convicted of corruption from securing government contracts.[169] The ban applies even if the crimes are admitted as part of a plea bargain agreement for a reduced sentence.[170]

Peru has also enacted harsher penalties for public officials found guilty of corruption and prohibitions on such officials from being able to work in the public sector post-conviction. Legislative Decree No. 1243 (the “civil death” law) was enacted in late 2016 to establish harsher sentences for corruption-related offenses and to increase the “civil disqualification” period to five to twenty years for corruption crimes like extortion, simple and aggravated collusion, embezzlement, and bribery.[171] That said, this disqualification only applies to crimes committed as part of a “criminal organization,” and because of the practicalities involved in these types of crimes, it is unlikely that many officials will be found to have been part of a “criminal organization” and thus barred from public service.[172]

Legislative Decree No. 1295 was also enacted on December 30, 2016 with provisions to improve government integrity.[173] The decree created the National Registry of Sanctions against Civil Servants (Registro Nacional de Sanciones contra Servidores Civiles).[174] This online registry will be updated monthly by the National Authority of Civil Service (Autoridad Nacional del Servicio Civil) and will consolidate all the information relevant to disciplinary actions and/or sanctions against public officials (including corruption charges).[175] Anyone listed in the registry is prohibited from government employment for the duration of their registry.[176]

[1] This article is intended to review key developments in the five enumerated countries. Changes to the compliance environment continue throughout Central and South America, though they are not covered in this particular update.

[2] Petróleos Mexicanos – Pemex, Report of Foreign Private Issuer (Form 6-K) (Nov. 11, 2017), at 8.

[3] Petróleos Mexicanos – Pemex, Report of Foreign Private Issuer (Form 6-K) (Sept. 29, 2017), at 21.

[4] See Plea Agreement, Attach. B ¶¶ 59-60, United States v. Odebrecht S.A., Cr. No. 16-643 (RJD) (E.D.N.Y. Dec. 21, 2016).

[5] See Secretaría de la Función Pública, Abre SFP nuevos procedimientos administrativos en contra de filial de Odebrecht (Sep. 11, 2017), https://www.gob.mx/sfp/articulos/abre-sfp-nuevos-procedimientos-administrativos-en-contra-de-filial-de-odebrecht-126170?idiom=es.

[6] Azam Ahmed and J. Jesus Esquivel, Mexico Graft Inquiry Deepens with Arrest of a Presidential Ally, N.Y. Times, Dec. 20, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/20/world/americas/mexico-corruption-pri.html.

[7] Id.; Detienen a extesorero del PRI por presunto desvío de recursos en 2016, El Financiero, Dec. 20, 2017, http://www.elfinanciero.com.mx/nacional/detienen-a-extesorero-del-pri-por-presunto-desvio-de-recursos-en-2016.html.

[8] Ley General de Responsabilidades Administrativas, Artículos 2, 52, 66, 70 (July 18, 2016) (Mex.) [hereinafter “GLAR”].

[9] GLAR at Artículos 49, 51.

[10] Id. at Artículo 49.

[11] Id. at Artículos 51-64.

[12] Id. at Artículos 3, 4, 65.

[13] Bribery includes promising, offering, or giving any benefit, whether it be through money, valuables, property, services well below market value, donations, or any other benefit, to a public servant or their spouse in return for the public servant performing or refraining from performing any act related to their duties, or using their influence in their position, for the purpose of obtaining or maintaining a benefit or advantage, irrespective of the benefit actually being achieved. Id. at Artículos 52, 66.

[14] Id. at Artículo 67.

[15] Id. at Artículo 68.

[16] Id. at Artículo 69.

[17] Id. at Artículo 71.

[18] Id. at Artículo 72.

[19] Id. at Artículo 70.

[20] Id.

[21] Under Article 81 of the GLAR, if no benefit is obtained through the corrupt act, the financial penalty is calculated by multiplying a statutorily defined value by the daily tenor of a Mexican government economic reference rate called the Unidad de Medida y Actualización (“UMA”). While the UMA is a variable rate that changes over time, the statutory multiple is static and defined by the GLAR. For physical persons—if no benefit was obtained—the penalty can be up to 150,000 times the UMA (approximately $597,000 USD as of May 2017). GLAR, Artículo 81.

[22] Id.

[23] Id.

[24] Id.

[25] Id.

[26] Id.

[27] Id. at Artículo 25.

[28] The seven required elements of the integrity program are delineated in the statute and discussed more fully in Gibson Dunn’s review of the GLAR, found at https://www.gibsondunn.com/mexicos-new-general-law-of-administrative-responsibility-targets-corrupt-activities-by-corporate-entities/.

[29] GLAR at Artículos 88-89.

[30] Id. at Artículo 81.

[31] Id. at Artículos 88-89.

[32] Id. at Artículo 89.

[33]Id.

[34]Id.

[35] Ministério Público Federal, MPF recebe prêmio internacional por trabalho no combate à corrupção (Nov. 6, 2017), http://www.mpf.mp.br/rj/sala-de-imprensa/noticias-rj/mpf-recebe-premio-internacional-pelo-combate-a-corrupcao.

[36] Press Release, Transparency Int’l Secretariat, Brazil’s Carwash Task Force Wins Transparency Int’l Anti-Corruption Award (Dec. 6, 2016).

[37] See generally FCPA Tracker, https://fcpatracker.com/.

[38] See Felipe Gutierrez, Moro se diz ‘cansado’ e que trabalho da Lav Jato em Curitiba esta no fim, Folha de Sao Paulo, Aug. 15, 2017, http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/poder/2017/10/1923633-moro-diz-que-trabalho-da-lava-jato-em-curitiba-esta-acabando.shtml.

[39] Id.

[40] See Ministério Público Federal, A Lava Jato em numeros – STF (Jan. 12, 2018), http://www.mpf.mp.br/para-o-cidadao/caso-lava-jato/atuacao-no-stj-e-no-stf/resultados-stf/a-lava-jato-em-numeros-stf.

[41] Entenda a Operação Zelotes da Polícia Federal, Folha de São Paulo, Apr. 1, 2015, http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/mercado/2015/04/1611246-entenda-a-operacao-zelotes-da-policia-federal.shtml.

[42] Id.

[43] Mateus Rodrigues, MPF denuncia executivos da Gerdau na Zelotes por corrupcão e lavagem de dinheiro, Oglobo, Aug. 24, 2017, https://g1.globo.com/distrito-federal/noticia/mpf-denuncia-executivos-da-gerdau-na-zelotes-por-corrupcao-e-lavagem-de-dinheiro.ghtml; MPF denuncia Lula e Gilberto Carvalho por corrupcao passive na Operacoes Zelotes, Oglobo, Sept. 11, 2017, https://g1.globo.com/politica/noticia/mpf-denuncia-lula-por-corrupcao-passiva-na-operacao-zelotes.ghtml.

[44] MPF denuncia Lula e Gilberto Carvalho por corrupcao passive na Operacoes Zelotes, supra note 43.

[45] Entenda a Operação Zelotes da Polícia Federal, supra note 41.

[46] Estelita H. Carazzai, Bela Megale, & Camila Mattoso, Operação contra frigoríficos prende 37 e descobre até carne podre à venda, Folha de S. Paulo, Mar. 17, 2017, http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/mercado/2017/03/1867309-pf-faz-operacao-contra-frigorificos-e-cumpre-quase-40-prisoes.shtml.

[47] Id.

[48] Id.

[49] Operação Bullish investiga fraudes em empréstimos no BNDES, Agência de Notícias de Polícia Federal, May 12, 2017, http://www.pf.gov.br/agencia/noticias/2017/05/operacao-bullish-investiga-fraudes-em-emprestimos-no-bndes; Bela Megale, Camila Mattoso, & Raquel Landim, Operação policial põe sob suspeita apoio do BNDES à expansão da JBS, Folha de S. Paulo, May 12, 2017, http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/mercado/2017/05/1883367-pf-deflagra-operacao-que-investiga-fraudes-em-emprestimos-no-bndes.shtml.

[50] Megale et al., supra note 49.

[51] Id.

[52] Graziele Frederico and Gabriela Lapa, Grupo de acusados na ‘máfia de próteses’ do DF fecha acordo de delação premiada, Oglobo, Feb. 9, 2017, http://g1.globo.com/distrito-federal/noticia/grupo-de-acusados-na-mafia-das-proteses-do-df-fecha-acordo-de-delacao-premiada.ghtml.

[53] Id.

[54] Ministério da Transparência e Controladoria-Geral da União, CGU e AGU assinam acordo de leniência com UTC Engenharia, July 10, 2017, http://www.cgu.gov.br/noticias/2017/07/cgu-e-agu-assinam-acordo-de-leniencia-com-o-utc-engenharia.

[55] Id.

[56] Id.

[57] Id.

[58] Id.

[59] Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Rolls-Royce plc Agrees to Pay $170 Million Criminal Penalty to Resolve Foreign Corrupt Practices Act Case (Jan. 17, 2017), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/rolls-royce-plc-agrees-pay-170-million-criminal-penalty-resolve-foreign-corrupt-practices-act.

[60] Deferred Prosecution Agreement, Attach. A ¶ 20, United States v. Rolls-Royce plc, No. 2:16-CR-00247-EAS (S.D. Ohio. Dec. 20, 2016).

[61] Id.

[62] Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, supra note 59.

[63] Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, SBM Offshore N.V. and United States-Based Subsidiary Resolve Foreign Corrupt Practices Act Case Involving Bribes in Five Countries (Nov. 29, 2017), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/sbm-offshore-nv-and-united-states-based-subsidiary-resolve-foreign-corrupt-practices-act-case.

[64] Deferred Prosecution Agreement, Attach. A ¶¶ 27, 35, United States v. SBM Offshore N.V., No. 17-686 (S.D. Tex. Nov. 29, 2017).

[65] Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, supra note 63.

[66] Id.

[67] Id.

[68] Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Odebrecht and Braskem Plead Guilty and Agree to Pay at Least $3.5 Billion in Global Penalties to Resolve Largest Foreign Bribery Case in History (Dec. 21, 2016), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/odebrecht-and-braskem-plead-guilty-and-agree-pay-least-35-billion-global-penalties-resolve.

[69] Plea Agreement ¶ 21(b), United States v. Odebrecht, No. 16-643 (RJD) (Dec. 21, 2016).

[70] Id. at ¶ 21(c).

[71] Sentencing Memorandum at 4, United States v. Odebrecht S.A., No. 13-643 (RJD) (Apr. 11, 2017).

[72] Id.

[73] Lei No. 7753 de 17 de outubro de 2017, do Rio de Janeiro.

[74] Id. at Artigo 1.

[75] Id.; Lei No. 12.846 de 2013, at Artigo 7.

[76] Fausto Macedo, Quais são e o Que propõem as ’10 Medidas contra a corrupção’ do Ministério Público, Estadão, Sept. 16, 2015, http://politica.estadao.com.br/blogs/fausto-macedo/quais-sao-e-o-que-propoem-as-10-medidas-contra-a-corrupcao-do-ministerio-publico/.

[77] Marcello Larcher, CCJ valida assinaturas do projeto das dez medidas contra a corrupção, Agência Câmara Notícias, Mar. 28, 2017, http://www2.camara.leg.br/camaranoticias/noticias/POLITICA/527029-CCJ-VALIDA-ASSINATURAS-DO-PROJETO-DAS-DEZ-MEDIDAS-CONTRA-A-CORRUPCAO.html.

[78] Renan Ramalho, MP apresenta dez propostas para reforçar combate à corrupção no país, Oglobo, Mar. 20, 2015, http://g1.globo.com/politica/noticia/2015/03/mp-apresenta-dez-propostas-para-reforcar-combate-corrupcao-no-pais.html.

[79] Felipe Gelani, Lei de abuso de autoridade divide opinões entre juristas, Jornal do Brasil, Dec. 4, 2016, http://m.jb.com.br/pais/noticias/2016/12/04/lei-de-abuso-de-autoridade-divide-opinioes-entre-juristas/; Projeto com medidas contra a corrupção aguarda relator na CCJ, Senado Notícias (Apr. 17, 2017), https://www12.senado.leg.br/noticias/materias/2017/04/17/projeto-com-medidas-contra-a-corrupcao-aguarda-relator-na-ccj.

[80] Ricardo Brandt, ‘Congresso destruiu’ as 10 Medidas contra Corrupção, diz procurador da Lava Jato, Estadão, Dec. 3, 2016, http://politica.estadao.com.br/blogs/fausto-macedo/congresso-destruiu-as-10-medidas-contra-corrupcao-diz-procurador-da-lava-jato/.

[81] Ministério Público Federal, Orientation No. 07/2017 – Leniency Agreements (Aug. 24, 2017), http://www.mpf.mp.br/pgr/documentos/ORIENTAO7_2017.pdf.

[82] Id.

[83] Id.

[84] Id.

[85] Almudena Calatrava, Argentine Clean-up President Macri Finds Scandals of His Own, U.S. News, Mar. 3, 2017 https://www.usnews.com/news/world/articles/2017-03-03/argentine-clean-up-president-macri-finds-scandals-of-his-own; Abren investigación contra presidente de Argentina por presunta asociación ilícita y tráfico de influencias, CNN Español, Mar. 1, 2017, http://cnnespanol.cnn.com/2017/03/01/abren-investigacion-al-presidente-de-argentina-mauricio-macri-por-entrega-de-rutas-aereas-a-avianca/.

[86] Lucia de Dominicis, 10 promesas incumplidas de Macri en sus 2 años de gobierno, La Primera Piedra, Dec. 10, 2017, http://www.laprimerapiedra.com.ar/2017/12/10-promesas-incumplidas-de-macri/.

[87] Calatrava, supra note 85; Fiscal argentino abre investigación a Mauricio Macri por firmas ‘offshore,’ La Prensa, Apr. 7, 2016, https://www.prensa.com/mundo/Fiscal-argentino-investigacion-Mauricio-Macri_0_4455304547.html.

[88] Abren investigación contra presidente de Argentina por presunta asociación ilícita y tráfico de influencias, supra note 85.

[89] Hugo Alconada Mon, Un Operador de Odebrecht le giro US$ 600.00 al jefe de inteligencia argentine, La Nacion, Jan. 11, 2017, http://www.lanacion.com.ar/1974791-un-operador-de-odebrecht-le-giro-us-600000-al-jefe-de-inteligencia-argentino; AFP, Argentina: fiscal abre causa contra jefe de espias por giro de Odebrecht, La Prensa, Jan. 24, 2017, https://www.prensa.com/mundo/Argentina-fiscal-causa-espias-Odebrecht_0_4674282545.html.

[90] Mon, supra note 89.

[91] Frederico Rivas Molina, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner suma otro procesamiento por corrupción, El Pais, Apr. 4, 2017, https://elpais.com/internacional/2017/04/04/argentina/1491322535_840466.html.

[92] Id.

[93] Id.

[94] Max Radwin and Anthony Faiola, Argentine Ex-president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner Charged with Treason, Wash. Post, Dec. 7, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/the_americas/argentine-ex-president-cristina-fernandez-charged-with-treason/2017/12/07/e3e326e0-db80-11e7-a241-0848315642d0_story.html?utm_term=.37df90a6bf06.

[95] Argentina Former Vice-President Amado Boudou Arrested, BBC News, Nov. 3, 2017, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-41867239.

[96] Argentina Congress Passes Law to Fight Corporate Corruption, Reuters, Nov. 8 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-argentina-corruption/argentina-congress-passes-law-to-fight-corporate-corruption-idUSKBN1D83AX; La Ley de Responsabilidad Penal de las Personas Jurídicas, Law No. 27401 (Nov. 8, 2017), Artículo 1 (Arg.) [hereinafter Ley de Responsabilidad Penal].

[97] La Ley de Responsabilidad Penal de las Personas Jurídicas, at Artículo 1, supra note 96.

[98] Paula Urien, Cómo reaccionan las compañías ante la ley penal empresaria, La Nacion, March 4, 2018, https://www.lanacion.com.ar/2113848-como-reaccionan-las-companias-ante-la-ley-penal-empresaria.

[99] Ley de Responsibilidad Penal, at Artículo 2, supra note 97.

[100] Id. at Artículo 1.

[101] Id. at Artículo 2.

[102] Id. at Artículo 3.

[103] Id. at Artículo 29.

[104] Id. at Artículo 7.

[105] Id.

[106] Id.

[107] Id.

[108] Id. at Artículo 9.

[109] Id. at Artículo 16.

[110] Id. at Artículos 16, 18.

[111] Id. at Artículo 23.

[112] Id.

[113] Id.

[114] Id.

[115] Id.

[116] Id.

[117] Id.

[118] Id.

[119] Id.

[120] Id.

[121] Id.

[122] DOJ and SEC, A Resource Guide to the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, at 57 (Nov. 14, 2012); GLAR at Artículo 25.

[123] See Plea Agreement, Attach. B ¶ 51, United States v. Odebrecht S.A., Cr. No. 13-643 (RJD) (E.D.N.Y. Dec. 21, 2016).

[124] ¿Pueden las leyes acabar con la corrupción?, Política, July 29, 2017, http://www.semana.com/nacion/articulo/corrupcion-10-proyectos-de-ley-se-tramitan-en-el-congreso-sirven/534225; Julia Symmes Cobb & Guillermo Parra-Bernal, Colombia Arrests Ex-Senator Linked to Odebrecht Graft Scandal, Reuters, Jan. 15, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/brazil-corruption-odebrecht-colombia/colombia-arrests-ex-senator-linked-to-odebrecht-graft-scandal-idUSL1N1F5073.

[125] Cobb & Parra-Bernal, supra note 124.

[126] Jose Maria Irujo & Joaquin Girl, La policía investiga la conexión Colombia-Miami en los pagos al Exviceministro García Morales, El Pais, Nov. 9, 2017, https://elpais.com/internacional/2017/11/06/actualidad/1509965659_671036.html.

[127] Fiscalía General de la Nación, Imputados empresarios extranjeros y colombianos por corrupción en la construcción de Reficar (July 26, 2017), https://www.fiscalia.gov.co/colombia/bolsillos-de-cristal/imputados-empresarios-extranjeros-y-colombianos-por-corrupcion-en-la-construccion-de-reficar/.

[128] Id.

[129] Id.

[130] Fiscalía General de la Nación, Refineria de Cartagena (2017), https://www.fiscalia.gov.co/colombia/wp-content/uploads/Presentacion-REFICAR270417.pdf.

Santos ratificó extradición del exfiscal Luis Gustavo Moreno, RCN Radio, Mar. 12, 2018, https://www.rcnradio.com/judicial/santos-ratifico-extradicion-del-exfiscal-luis-gustavo-moreno.

[132] Id.

[133] Presidencia de la República, Gobierno presenta paquete de iniciativas para combatir la corrupción (Aug. 18, 2017), http://es.presidencia.gov.co/noticia/170818-Gobierno-presenta-paquete-de-iniciativas-para-combatir-la-corrupcion.

[134] Ley. 1778 de 2016 (Feb. 2, 2016) Diario Oficial 49.774 (Colo).

[135] Id. at Artículo 2.

[136] Presidente anuncia nuevas medidas para seguir enfrentando el desafío de la corrupción y a los corruptos, El Observatario, Apr. 19, 2017, http://www.anticorrupcion.gov.co/Paginas/Presidente-anuncia-nuevas-medidas-para-seguir-enfrentando-el-desafio-de-la-corrupcion-y-a-los-corruptos.aspx.

[137] Colombia tendrá jueces especializados en casos de corrupción, El Observatario, Dec. 7, 2017, http://www.anticorrupcion.gov.co/Paginas/Colombia-tendra-jueces-especializados-en-casos-de-corrupcion.aspx.

[138] Leyes en Contra de la Corrupción, la Apuesta del Gobierno Nacional, Actualicese, July 13, 2017, http://actualicese.com/actualidad/2017/07/13/leyes-en-contra-de-la-corrupcion-la-apuesta-del-gobierno-nacional/.

[139] Colombia y Peru contra soborno transnacional, El Nuevo Siglo, Sep. 23, 2017, http://www.elnuevosiglo.com.co/articulos/09-2017-colombia-y-peru-combatiran-soborno-transnacional.

[140] Id.

[141] See Juan Cruz Peña, Colombia investiga a tres empresas españolas por sobornos e irregularidades, El Confidencial, May 17, 2017, https://www.elconfidencial.com/empresas/2017-05-17/colombia-investiga-empresas-espanolas-sobornos-desfalco_1379311/.

[142] United States v. Odebrecht S.A., Docket No. 16-CR-643 (RJD) (E.D.N.Y. 2016).

[143] Odebrecht Banned from Signing Contracts with Peru State, Andina, Jan. 9, 2017, http://www.andina.com.pe/Ingles/noticia-odebrecht-banned-from-signing-contracts-with-peru-state-648542.aspx.

[144] Mitra Taj, Peru to Bar Odebrecht from Public Bids with New Anti-graft Rules, Reuters, Dec. 28, 2016, http://www.reuters.com/article/peru-corruption-odebrecht-idUSL1N1EO00K.

[145] Id.

[146] Lucas Perelló, Pablo Kuczynski Loses Another Battle to the Fujimorista Opposition, Global Americans, Sept. 28, 2017, https://theglobalamericans.org/2017/09/perus-pedro-pablo-kuczynski-loses-another-battle-fujimorista-opposition/.

[147] Simeon Tegel, Latin America’s Mega-Corruption Scandal Just Claimed its Two Biggest Names, Wash. Post, July 15, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2017/07/15/latin-americas-mega-corruption-scandal-just-claimed-its-two-biggest-names/?utm_term=.6c05e8a6bb8c; Jimena De La Quintana, Ordenan prisión preventive para Ollanta Humala y Nadine Heredia, CNN en Espanol, July 13, 2017, http://cnnespanol.cnn.com/2017/07/13/ordenan-prision-para-ollanta-humala-y-nadine-heredia/.

[148] Id.

[149] ¿Cuál es la relación de Alan García con el caso Odebrecht y Lava Jato?, Radio Programas del Perú, Aug. 7, 2017, http://rpp.pe/politica/judiciales/la-relacion-de-alan-garcia-con-los-casos-odebrecht-y-lava-jato-noticia-1049631.

[150] Ryan Dube, Judge Orders Arrest of Former Peruvian President Alejandro Toledo in Odebrecht Bribery Case, Wall Street J., Feb. 9, 2017, https://www.wsj.com/articles/judge-orders-arrest-of-former-peruvian-president-alejandro-toledo-in-odebrecht-bribery-case-1486698137; U.S. State Department Office of Investment Affairs, Peru Country Commercial Guide – Investment Climate Statement (Sept. 20, 2017), https://www.export.gov/article?id=Peru-Corruption.

[151] Peru court approves Toledo extradition request, Yahoo News, Mar. 13, 2018, https://www.yahoo.com/news/peru-court-approves-toledo-extradition-request-164803106.html.

[152] Lucas Perelló, Pablo Kuczynski Loses Another Battle to the Fujimorista Opposition, Global Americans, Sept. 28, 2017, https://theglobalamericans.org/2017/09/perus-pedro-pablo-kuczynski-loses-another-battle-fujimorista-opposition/; PPK declarará el Viernes por Caso Odebrecht ante fiscalía, El Comercio, Mar. 29, 2017, https://elcomercio.pe/politica/justicia/ppk-declarara-viernes-caso-odebrecht-fiscalia-420928.

[153] Ex-Odebrecht CEO Says Hired Peru President as Consultant – Reports, Reuters, Nov. 14, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/peru-politics/ex-odebrecht-ceo-says-hired-peru-president-as-consultant-reports-idUSL1N1NK1H4.

[154] Peru: President Kuczynski Denies Odebrecht Bribe Allegations, BBC News, Nov. 16, 2017, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-42006558; Andrea Zarate & Nicholas Casey, Peru Leader Could Be Biggest to Fall in Latin America Graft Scandal, N.Y. Times, Dec. 19, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/19/world/americas/peru-kuczynski-impeachment.html.

[155] Simeon Tegel, Peru’s President Survives Impeachment Vote Over Corruption Charges, Wash. Post, Dec. 22, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/the_americas/perus-president-faces-impeachment-over-corruption-allegations/2017/12/20/61b2b624-e4d9-11e7-927a-e72eac1e73b6_story.html?utm_term=.e542fa1216da.

Sonia Goldenberg, ‘Game of Thrones’, Inca Style, N.Y. Times, Dec. 28, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/28/opinion/peru-kuczynski-fujimori-pardon-odebrecht.html.

[156] Jacqueline Fowks, El fantasma de Odebrecht arrecia en Perú, El País, Mar. 8, 2018, https://elpais.com/internacional/2018/03/08/america/1520467389_977266.html.

[157] U.S. State Department Office of Investment Affairs, supra note 150.

[158] Id.

[159] Decreto Legislativo No. 1352, Artículo 1 (Jan. 2017) (Peru).

[160] Id. at Artículo 3.

[161] Id. at Artículo 1.

[162] Id. at Artículo 4.

[163] Id. at Artículos 3-4; New Criminal Liability System for Corporate involved in Corrupt Practices and/or Money Laundering, http://www.estudiorodrigo.com/en/new-criminal-liability-system-for-corporate-involved-in-corrupt-practices-andor-money-laundering/.

[164] Decreto Legislativo No. 1352, Artículo 3.

[165] Id. at Artículo 17.

[166] Id.

[167] Id.

[168] Omar Manrique, Todas las empresas deberán tomar medidas para prevenir corrupción, Gestión, Dec. 27, 2017, https://gestion.pe/economia/empresas-deberan-medidas-prevenir-corrupcion-223626.

[169] Decreto Legislativo No. 1341, Artículo 11 (Jan. 2017) (Peru); José Antonio Payet & Payet Rey Cauvi Pérez, PERUVIAN UPDATE – The Impact of “Lava Jato” on M&A in Peru, International Institute for the Study of Cross-Border Investment and M&A, May 30, 2017, http://xbma.org/forum/peruvian-update-the-impact-of-lava-jato-on-ma-in-peru/.

[170] Decreto Legislativo No. 1341, supra note 169.

[171] Ejecutivo oficializó ley de muerte civil para corruptos, El Comercio, Oct. 22, 2016, http://elcomercio.pe/politica/gobierno/ejecutivo-oficializo-ley-muerte-civil-corruptos-273517; Decreto Legislativo No. 1243, Artículo 38 (Oct. 2016) (Peru).

[172] Comentarios a la “Muerte Civil,” Decreto Legislativo 1243, Parthenon, Nov. 1, 2016, http://www.parthenon.pe/editorial/comentarios-a-la-muerte-civil-decreto-legislativo-1243/.

[173] Decreto Legislativo No. 1295 (Dec. 2016) (Peru).

[174] Id. at Artículo 1.

[175] Id. at Artículo 4.

[176] Id.

The following Gibson Dunn lawyers assisted in preparing this client update: F. Joseph Warin, Michael Farhang, Lisa Alfaro, Tafari Lumumba, Michael Galas, Abiel Garcia, Renee Lizarraga, John Sandoval and Sydney Sherman.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these issues. We have more than 110 attorneys with FCPA experience, including a number of former prosecutors and SEC officials, spread throughout the firm’s domestic and international offices. Please contact the Gibson Dunn attorney with whom you usually work in the firm’s FCPA group, or the authors:

F. Joseph Warin – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3609, [email protected])

Michael M. Farhang – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7005, [email protected])

Please also feel free to contact the following Latin America practice group leaders:

Lisa A. Alfaro – São Paulo (+55 (11) 3521-7160, [email protected])

Kevin W. Kelley – New York (+1 212-351-4022, [email protected])

Tomer Pinkusiewicz – New York (+1 212-351-2630, [email protected])

Jose W. Fernandez – New York (+1 212-351-2376, [email protected])

© 2018 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.