July 10, 2018

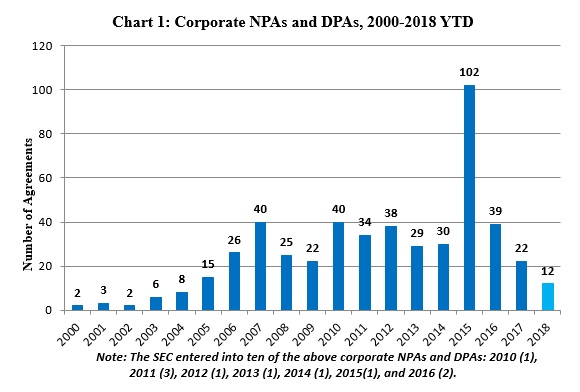

This publication marks our tenth year tracking corporate non-prosecution agreements (“NPAs”) and deferred prosecution agreements (“DPAs”).[1] What a decade it has been. In our time analyzing and reporting on these resolutions, we have seen the pendulum swing from 22 agreements concluded in a single year (in 2009 and 2017), to a high of 102 agreements (in 2015)—a yield that surprised even the enforcement agencies executing them. We also have seen greater standardization of certain agreement terms as enforcement agency experience has developed, removal of certain terms—like mandatory privilege waivers—as prosecutorial policy has evolved, and application to an ever-widening scope of laws and conduct. In a testament to the efficacy of DPAs in addressing allegations of corporate misconduct, we also have watched as countries around the globe have moved toward formalizing processes to adopt similar agreements. We look forward to observing and sharing with you the changes that the next decade will bring.

This client alert, the twentieth in our biannual series on NPAs and DPAs: (1) compiles statistics regarding NPAs and DPAs through the present; (2) highlights important developments in enforcement agency policy impacting penalties imposed in these corporate agreements; (3) revisits the role of the judiciary in DPA oversight, driven by recent judicial pronouncements; (4) reports on several recent developments in corporate monitorships, including an evaluation of recent DPAs that provide important lessons in how to avoid them; (5) analyzes NPAs and DPAs released to date in 2018; and (6) tours the ever-expanding number of jurisdictions adopting DPA-style regimes.

NPAs and DPAs in 2018

The Department of Justice (“DOJ” or “the Department”) has entered into 12 agreements thus far in 2018, of which six are NPAs and six are DPAs. The Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC” or “the Commission”) has not entered into any NPAs or DPAs this year. This year’s 12 agreements to date represent an increase of three agreements from what we saw at this point in 2017, when there were nine agreements. It is also early in 2018, and there are many investigations in the enforcement pipeline that may provide additional resolutions in the coming months.

Notably, while the SEC has not entered into any NPAs or DPAs in recent months, it nevertheless has signaled a continued favorable view of NPAs and DPAs through recently proposed amendments to the rules governing its whistleblower program. In particular, if adopted, the proposed rule amendments would expressly allow the SEC to make award payments to whistleblowers on the basis of NPA and DPA recoveries, to “ensure that whistleblowers are not disadvantaged because of the particular form of action that the Commission, DOJ or a state attorney general acting in a criminal case may elect to pursue.”[2] The rules presently are silent regarding whether whistleblowers can recover for actions that lead to NPAs and DPAs, as opposed to other forms of award.

Chart 1 below shows all known corporate NPAs and DPAs since 2000.

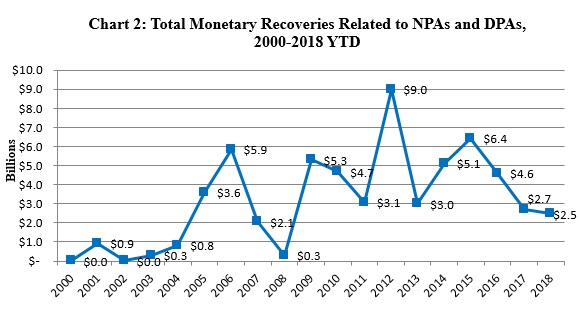

Chart 2 below illustrates the total monetary recoveries related to NPAs and DPAs from 2000 through the present. Although we are only half-way through 2018, overall recoveries have already been relatively strong at nearly $2.5 billion, driven by a handful of high-value resolutions.

Corporate Enforcement Developments Impacting NPAs and DPAs: DOJ’s “Piling on” Memorandum

On May 9, 2018, Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein announced a new policy regarding the coordination of corporate resolution penalties. In his remarks to the New York City Bar White Collar Crime Institute, Rosenstein stated that the government should “discourage disproportionate enforcement of laws by multiple authorities.”[3] Through amendments to the U.S. Attorneys’ Manual,[4] DOJ now expressly discourages the “piling on” of penalties relating to the same misconduct by “instructing Department components to appropriately coordinate with one another and with other enforcement agencies in imposing” any penalties.[5] Rosenstein focused on the concept of “fairness,” and acknowledged that “piling on” can deprive a corporation of certainty and finality, as well as negatively impact employees, investors, and customers.[6]

The memorandum states that in reaching a resolution, DOJ “should consider the totality of fines, penalties, and/or forfeiture imposed by” all enforcement agencies and regulators to achieve a just and fair result.[7] Rosenstein highlighted four key features of the new policy. First, the policy reinforces that the federal government should not use its criminal enforcement authority “for purposes unrelated to the investigation and prosecution of a possible crime.”[8] For example, the government should not threaten “criminal prosecution solely to persuade a company to pay a larger settlement in a civil case.”[9] Second, the policy directs DOJ officials to coordinate among themselves to “achieve an overall equitable result.”[10] Rosenstein specified that such coordination “may include crediting and apportionment of financial penalties, fines, and forfeitures.”[11] Third, the policy instructs DOJ attorneys “to coordinate with other federal, state, local, and foreign enforcement authorities seeking to resolve a case with a company for the same misconduct.”[12] Finally, the policy identifies factors that DOJ may use to determine “whether multiple penalties serve the interests of justice,” such as “egregiousness of the wrongdoing; statutory mandates regarding penalties; the risk of delay in finalizing a resolution; and the adequacy and timeliness of a company’s disclosures and cooperation.”[13]

DOJ’s “piling on” policy reflects efforts in certain negotiated resolutions to avoid unfairly punishing corporations and duplicative penalties. We have seen DOJ credit monetary resolutions with other enforcement agencies—both foreign and domestic—in several of the highly coordinated NPAs and DPAs in recent history. Just this year, for example, on January 18, 2018, HSBC Holdings PLC (“HSBC”) entered into a DPA with the DOJ Fraud Section[14] to resolve criminal charges filed against HSBC in the Eastern District of New York for two counts of alleged wire fraud impacting two bank clients.[15] The government considered a number of factors in reaching its resolution with HSBC, including (1) the approximately $46.4 million that HSBC allegedly gained from the conduct; (2) the bank’s substantial remedial measures, such as improved internal controls and the termination of involved employees; and (3) HSBC’s commitment to enhance compliance and internal controls.[16] DOJ did not grant credit for voluntarily disclosing the conduct, but it did award cooperation credit after HSBC made adjustments midstream to improve its responsiveness, and the quality of information conveyed, to the government.[17] HSBC agreed to pay a monetary penalty of approximately $63.1 million to the U.S. Treasury.[18] Significantly, in calculating restitution and disgorgement, the DOJ Fraud Section considered the bank’s monetary settlement of almost $8.1 million with Cairn Energy, one of the two bank clients allegedly impacted by the conduct at issue.[19] With respect to the second bank client, the DOJ Fraud Section mandated a payment of $38.4 million as disgorgement, less the amount HSBC would pay to the bank client as restitution.[20]

Similarly, on February 12, 2018, U.S. Bancorp (“USB”) and the Office of the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York entered into a DPA.[21] The DPA resolved criminal charges against USB, consisting of two alleged violations of the Bank Secrecy Act (“BSA”) by USB’s subsidiary, U.S. Bank National Association, for willfully failing to maintain an adequate anti-money laundering program and willfully failing to file a Suspicious Activity Report.[22] The DPA specified that USB would pay the United States $528 million, less $75 million paid to the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (“OCC”), to satisfy a civil penalty levied in a parallel OCC regulatory action.[23]

In recognition of international enforcement considerations, DOJ acknowledged a resolution with the Parquet National Financier (“PNF”) in Paris in its agreement with Société Générale S.A. (“SocGen”). Approximately one month after DOJ’s release of the “piling on” memorandum, on June 5, 2018, SocGen entered into a DPA with the DOJ Fraud Section and the U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of New York. As discussed in more depth in our 2018 Mid-Year Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (“FCPA”) Update, the DPA resolved criminal charges against SocGen filed in the Eastern District of New York for one count of alleged conspiracy violating the FCPA’s anti-bribery provisions and one count of allegedly transmitting false commodities reports.[24] As part of the three-year DPA, the company agreed to pay a penalty of over $585 million to resolve the FCPA charges; however, DOJ also agreed to credit SocGen $292.8 million in light of its parallel resolution with PNF.[25] With respect to the second charge, the company agreed to pay a $275 million penalty, for a combined criminal penalty of more than $860 million.[26] Notably, SocGen’s DPA did not impose a compliance monitor, which a representative from France’s Anti-corruption Authority (“AFA”)—discussed further below—attributed to DOJ’s acknowledgment that, through SocGen’s monitorship with French authorities, “[DOJ] could get the information they needed from the good cooperation of the company and the good cooperation of French authorities.”[27]

We applaud DOJ’s acknowledgement of the importance of coordination and cooperation to achieve equity in cases where a company is facing multiple government inquiries arising from the same set of facts. Not only does such coordination help avoid unduly harsh and duplicative fines, it allows for more efficient resolutions and consistency in outcomes. One of the growing trends of the past decade in white collar enforcement—prompted by conscious effort and outreach by enforcers—has been an increase in cross-border collaboration and information sharing. Particularly where a company is facing overlapping investigations by regulators in multiple countries that do not recognize the concept of double jeopardy for international settlements, this kind of affirmative policy statement is key to promoting fair treatment of companies with cascading benefits to the many innocent stakeholders that depend upon them.

Judicial Oversight of DPAs

In recent years, we have reported on the continuing debate about judicial oversight of DPAs, evidenced by a growing trend of federal judges evaluating and approving or rejecting DPAs on their merits. Nowhere was this trend more apparent than in the protracted disputes between the courts and the parties to proposed DPAs in the anti-money laundering and sanctions matter involving HSBC in the Eastern District of New York, and the sanctions matter involving Fokker Services in the District of Columbia, both covered extensively in our 2015 Mid-Year through 2017 Year-End Updates. These cases each involved judicial efforts to engage with the merits of DOJ charging decisions (by now-former Judge John Gleeson of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York in HSBC and by Judge Richard Leon of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia in Fokker), a move that the Second Circuit and D.C. Circuit both soundly rejected on appeal.[28] Although the movement toward greater judicial involvement in DPAs stalled somewhat following the Second Circuit’s decision in HSBC and the D.C. Circuit’s decision in Fokker, as described below, the first half of 2018 suggests that an appetite remains among some members of the judiciary to test the limits of permissible judicial oversight, and that certain members of Congress also may seek to grant greater oversight of DPAs to the judiciary.

Fallout from HSBC and Fokker

In the USB case described above, Judge Lewis A. Kaplan has criticized the HSBC and Fokker decisions in connection with his consideration of the USB DPA. At a hearing on February 22, 2018, Judge Kaplan expressed his disapproval of the current lack of judicial oversight of DPAs, describing DPAs as “troublesome,” insofar as they allow corporations to avoid criminal prosecution by paying a fine instead of forcing culpable individuals to “pay the price” for their criminal activities.[29] He added, “it seems to this judge that both the interests of deterrence and the interests of just punishment are better served in all or most cases by prosecution of the individuals responsible” because “[c]rimes for which corporations are legally responsible are always committed by individuals.”[30] Nevertheless, Judge Kaplan concluded that he had “no discretion whatsoever” in the matter because of Second and D.C. Circuit precedent that limits judges’ authority to supervise DPAs.[31]

Similarly, in connection with the Transport Logistics International, Inc. (“TLI”) DPA—discussed further in our 2018 Mid-Year FCPA Update—District of Maryland Judge Theodore Chuang criticized the DPA, which TLI and DOJ had entered into, before reluctantly approving it. At a March 12, 2018 hearing on the agreement, echoing Judge Kaplan, Judge Chuang stated, “the thing that always bothers me about deferred prosecution agreements is that it seems as if the discussion is always about what do we do to save the company when it’s the company and its personnel who were engaged in crimes.”[32] In his April 2, 2018 order approving the agreement, Judge Chuang noted that a DPA “should be reserved for companies that have engaged in extraordinary cooperation and have entirely rid themselves of all remnants of the prior criminal activity,” and worried that the TLI DPA created a risk of “insufficient deterrence” of repeat behavior in the future.[33] Nevertheless, Judge Chuang concluded he was compelled to approve the agreement, citing the Fokker decision, where the D.C. Circuit held that a “district court may not ‘impose its own views about the adequacy of the underlying criminal charges’ and may only reject a DPA if it is not ‘geared to enabling the defendant to demonstrate compliance with the law’ and is instead ‘a pretext intended merely to evade the Speedy Trial Act’s time constraints.'”[34]

As we have discussed in prior updates, we respectfully disagree with Judges Kaplan and Chuang that DPAs somehow represent a choice by prosecutors between penalizing a company and charging individuals. In our experience, prosecutors do not forego holding individuals accountable in favor of imposing financial penalties on corporations.[35] Indeed, as exemplified by agreements like TLI, NPAs and DPAs often form part of a suite of resolutions applied to various corporate entities and individuals involved in alleged misconduct. In recent years, DPAs also have commonly included terms requiring continued cooperation and the sharing of facts to assist the government with effectively prosecuting any culpable individuals.[36] It is also shortsighted to think that a lack of individual prosecutions signals a failure to pursue the individuals behind corporate misdeeds. Building effective cases against individuals can be exceptionally challenging for complex white collar crimes, particularly without the kind of corporate cooperation and disclosure that an NPA or DPA may inspire. Indeed, the USB matter involved a criminal charge focused on a collective corporate act, namely the alleged failure to have an effective anti-money laundering program in violation of 31 U.S.C. Section 5318, Chapter 3; attributing this alleged failure to any single individual might result in unjust and arbitrary outcomes. Moreover, when personal liberties are at stake, individual defendants have a much greater appetite for trial, necessitating careful evaluation of the true viability of available evidence to secure a conviction. It appears to us that—particularly in the post-Yates Memorandum era—prosecutors are bringing more individual cases notwithstanding any parallel corporate resolution.

The “Ending Too Big to Jail Act”

Judges criticizing the current role of DPAs in criminal enforcement also have found some support in Congress. On March 14, 2018, Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) introduced the Ending Too Big to Jail Act, aimed at increasing accountability for large financial institutions that violate the law.[37] In an accompanying press release, Senator Warren asserted, “The fraud on Wall Street won’t stop until executives know they will be hauled out in handcuffs for cheating their customers and clients.”[38] Among other things, the legislation would require judicial oversight of DPAs between DOJ and financial institutions and prohibit a court from approving a DPA unless it determines that the agreement is in the public interest.[39] In making such a determination, a court would have to consider: (1) “whether any reforms required under the agreement are likely to prevent similar unlawful behavior in the future,” and (2) “whether any penalties under the agreement are sufficient to compensate victims and deter future unlawful actions.”[40] Moreover, if the defendant at issue has previously been convicted or entered into a DPA with the government in connection with a related activity, a court would be prohibited from approving the agreement without good cause.[41] The legislation also would authorize courts to oversee the implementation of DPAs, periodically request status reports, and require that DPAs be publicly filed.[42]

Senator Warren’s bill has received mixed reviews. On one hand, it has been endorsed by the AFL-CIO, Public Citizen, Americans for Financial Reform, and Professor Brandon Garrett of the University of Virginia School of Law.[43] Similarly, in April, Mehrsa Baradaran of the University of Georgia School of Law published an article in Fortune commending the bill as a “much-needed balance in the scales of justice.”[44] On the other hand, Peter Henning of the New York Times has argued that even if it were to pass—which, he says, is unlikely—it would fail to achieve its goal of increasing the number of prosecutions for corporate crimes because “[a]bsent proof of an executive’s involvement, or at least knowledge, of the fraud, a willful violation . . . would be difficult to prove.”[45]

Developments in Corporate Monitorships

Corporate monitorships often go hand in hand with white collar investigation resolutions, most often DPAs. Even in cases where one ultimately is not imposed, the specter of a monitor frequently factors—either explicitly or implicitly—in negotiations with enforcement agencies. Corporate monitorships can be exceptionally costly, and there are many pitfalls of monitor relationships—mission creep, company resource drain, and infeasible recommendations, to name a few—that must be deftly navigated when one is imposed. In the sections that follow, we look first at agreements that shed light on potential strategies for avoiding a corporate monitor in favor of self-reporting, and then at recent litigation and policy developments that may bear on monitor selection in cases where one cannot be successfully avoided.

Avoiding the Independent Compliance Monitor

Although NPAs and DPAs frequently impose robust self-evaluation and reporting requirements that can be challenging and costly to meet, virtually all companies strive for self-reporting rather than corporate monitorships due to the relative predictability, lack of disruption, and cost of self-reporting arrangements. There is no blueprint for avoiding a corporate monitor beyond staying out of the investigative spotlight in the first place, but several recent NPAs and DPAs have included language that lends insight into the considerations that may sway enforcement agencies toward or away from an independent monitor requirement.

Between 2016 and the present, there have been 17 agreements that imposed a compliance monitor, 21 agreements that required self‑reporting, and at least 26 agreements that imposed neither requirement. Deciphering an agency’s decision to impose a monitor in lieu of self-reporting can be like reading tea leaves for anyone but the parties involved, but DOJ has recently made a handful of express statements in NPAs and DPAs that begin to shed light on at least some of its monitoring decisions.

Of the 17 agreements imposing monitors from 2016 to present, for example, three have included an express emphasis on DOJ’s perception that the companies’ compliance programs were underdeveloped and/or only recently adopted. One of these agreements, DOJ’s January 2017 DPA with Sociedad Química y Minera de Chile (“SQM”), imposed an independent compliance monitor for a period of two years, with the possibility of a one‑year extension,[46] noting:

Although the Company has taken a number of remedial measures, the Company is still in the process of implementing its enhanced compliance program, which has not had an opportunity to be tested, and thus the Company has agreed to the imposition of an independent compliance monitor for a term of two years to diminish the risk of reoccurrence [sic] of the misconduct[.][47]

The other two agreements, the 2018 Panasonic Avionics Corporation (“PAC”) DPA (discussed in detail below) and DOJ’s December 2016 settlement with Teva Pharmaceuticals (“Teva”) adopted similar language. Like the SQM DPA, the PAC DPA also provided for a two‑year monitorship term with the possibility of a one‑year extension,[48] and noted that PAC “to date has not fully implemented or tested its enhanced compliance program, and thus the imposition of an independent compliance monitor for a term of two years . . . is necessary to prevent the reoccurrence [sic] of misconduct[.]”[49] The Teva agreement—still one of the largest FCPA settlements in history—also cited Teva’s “compliance program enhancements,” but noted that they “are more recent and have accordingly not been tested. Thus the Company has agreed to the imposition of an independent compliance monitor to diminish the risk of reoccurrence [sic] of the misconduct[.]”[50] The Teva DPA imposed a monitorship for the full three‑year term of the agreement.[51] In all three instances, DOJ seems to have focused not only on the design and implementation of compliance programs, but also on the testing of those programs in the ordinary course of business.[52]

On the other side of the coin, seven of 21 agreements that have imposed self-monitoring have provided insight into the reasons why corporate monitors were avoided. These agreements included a DPA with SocGen in 2018; DPAs with SBM Offshore (“SBM”) and Keppel Offshore & Marine Ltd. (“Keppel”) in 2017; an NPA with JPMorgan Securities (Asia Pacific) Limited (“JPMorgan-APAC”) in 2016; and NPAs with Credit Suisse (Hong Kong) Limited (“Credit Suisse”) in 2018, Legg Mason, Inc. (“Legg Mason”), and Imagina Media Audiovisual SL (“Imagina Media”), all of which included language very similar to the following:

[B]ased on the Company’s remediation and the state of its compliance program, and the Company’s agreement to report to the United States . . . the United States determined that an independent compliance monitor was unnecessary.[53]

Each of these seven agreements imposed a three-year term (including three years of self-reporting) and contained extensive sections outlining the remedial and compliance efforts undertaken by the companies. By way of illustration, we have briefly highlighted relevant provisions from a sampling of these agreements, below.

- Credit Suisse NPA (2018): DOJ provided partial cooperation credit to Credit Suisse for, among other things, conducting an internal investigation, making factual presentations to DOJ, voluntarily making foreign employees available for interviews, producing documents from foreign countries and providing translations of those documents, and collecting and presenting evidence to DOJ.[54] Although the Credit Suisse NPA noted that DOJ did not provide Credit Suisse with full voluntary disclosure, cooperation, or remediation credit, the company also received consideration for (1) adopting multiple, enumerated controls surrounding hiring, including post-hiring monitoring; (2) requiring improved FCPA and anti-corruption training for all personnel, including job-specific training; (3) continued enhancements to the company’s internal controls and compliance programs; and (4) continued cooperation with on-going investigations, including any investigations into the conduct of officers, subsidiaries, employees, agents, and other third parties.[55] For additional information regarding the Credit Suisse NPA, please see our 2018 Mid-Year FCPA Update.

- Société Générale S.A. DPA (2018): The SocGen DPA addressed two lines of alleged conduct: one relating to the FCPA, and the other relating to the London Interbank Offered Rate (“LIBOR”).

- With regard to the FCPA charges, the SocGen DPA notes that DOJ did not credit SocGen for voluntarily and timely disclosing the conduct underlying the FCPA charges resolved by the DPA. SocGen did, however, receive substantial credit for cooperating with DOJ’s investigation of the FCPA conduct, including conducting a “thorough and robust” investigation, collecting “voluminous” evidence in other countries, and providing “frequent and regular updates” to DOJ regarding facts learned during the internal investigation.[56] Nevertheless, SocGen’s DPA noted that the company did not receive full cooperation credit because of “issues that resulted in a delay during the early stages of the investigation, which led [DOJ], without the assistance of the company, to develop significant independent evidence of the company’s misconduct . . . .”[57] In addition to cooperation credit, SocGen received consideration for (1) the fact that its wholly owned subsidiary pled guilty to conspiracy to violate the anti-bribery provisions of the FCPA; (2) remedial measures, including separation of employees related to the alleged FCPA conduct, creating a new anti-bribery and corruption compliance program, and enhancing anti-corruption training for all management and relevant employees; (3) providing all relevant facts known to it, including facts about individuals; (4) compliance program and internal controls enhancements; and (5) SocGen’s entering into civil and criminal resolutions abroad arising from the same conduct.[58]

- With regard to the LIBOR charges, the SocGen DPA notes that DOJ did not credit SocGen for voluntary disclosure.[59] SocGen did receive partial cooperation credit for cooperation with DOJ’s investigation, including conducting a “thorough” internal investigation, collecting and producing “voluminous” evidence located in other countries, and providing frequent and regular updates to DOJ of facts learned during the company’s internal investigation.[60] SocGen did not, however, receive full cooperation credit because “its cooperation with the government was incomplete during the early stages of the investigation,” and SocGen only became cooperative after DOJ had independently developed “significant evidence” of the alleged conduct. Nevertheless, SocGen also engaged in remedial measures, including (1) separating implicated employees from the company; (2) implementing “substantial efforts to strengthen compliance;” (3) creating a new LIBOR oversight position; (4) implementing a new code of conduct; and (5) conducting a 100% review of all LIBOR submissions.[61] As with the FCPA allegations above, SocGen also received consideration for providing all relevant facts, including facts relating to implicated individuals.[62]

- Keppel DPA (2017): Keppel engaged in “substantial cooperation” with DOJ’s investigation by (1) completing a “thorough internal investigation;” (2) responding timely to DOJ’s requests; (3) “proactively identifying issues and facts that would likely be of interest” to DOJ; (4) providing extensive documents and evidence (including from foreign countries); (5) facilitating interviews of individuals; and (6) providing “all relevant facts known to it,” including information that assisted DOJ in prosecuting relevant individuals.[63] Keppel’s remediation efforts included (1) disciplinary action against 17 former or current employees; (2) separation of seven employees involved in the alleged misconduct; (3) financial sanctions against 12 current or former employees; (4) demotion of and/or warnings to an additional seven employees for failing to detect or mitigate alleged misconduct; (5) $8.9 million in financial sanctions against current and former employees; and (6) other disciplinary and remediation measures.[64] Keppel’s DPA fixed a three‑year term for the company’s self‑reporting requirement, with the possibility of a one‑year extension.[65]

- SBM DPA (2017): DOJ credited SBM for making a full (though alleged untimely) disclosure of the alleged conduct, carrying out a “thorough internal investigation,” providing extensive documents and information to DOJ (including from overseas), making individuals available for DOJ interviews, and providing information that assisted DOJ’s prosecution of culpable individuals.[66] SBM also terminated two of the three then‑current employees responsible for the alleged misconduct, and undertook a comprehensive review of agents that included the temporary cessation of payments to all agents and the termination of some agency relationships.[67] In addition, SBM hired a full-time Chief Governance and Compliance Officer, engaged an independent company to design a new compliance program, created a whistleblower hotline, and trained its sales and marketing personnel.[68] Finally, SBM submitted to similar oversight by the Dutch authorities in connection with a parallel investigation.[69] SBM’s self‑reporting requirement was imposed for the full three years of the DPA, with the possibility of a one‑year extension.[70]

- JPMorgan-APAC NPA (2016): JPMorgan-APAC received full cooperation credit in connection with its NPA based on its “thorough internal investigation,” “regular factual presentations,” facilitation of interviews of employees based overseas in the United States, and extensive production of documents and information to DOJ, including about relevant individuals.[71] JPMorgan-APAC and JPMorgan also “engaged in extensive remedial measures” that involved separation or other discipline for nearly 30 employees; over $18.3 million in financial sanctions levied against current or former employees; enhanced hiring controls; a doubling of JPMorgan’s compliance resources, particularly in the APAC region; and enhanced compliance and FCPA programs and training.[72] The NPA imposed the self‑reporting requirement for the full three‑year term of the agreement.[73]

Although each case, and every negotiation, is unique, these agreements support a view that the stronger and more robust an existing compliance program, and the swifter and more dramatic a company’s remediation of identified compliance gaps and misconduct, the more likely DOJ will look favorably upon self-reporting, rather than a corporate monitor.

Increased Focus on Monitor Candidates and Selection

This year has seen an increased focus on monitor candidates and monitor selection, both in the courts and at DOJ. The following section highlights a recent case in which the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia ordered the names of several independent compliance monitor candidates be disclosed, and a new addition to DOJ’s template monitor selection criteria requiring attention to diversity principles in candidate identification.

Tokar v. U.S. Department of Justice

As the use of independent compliance monitors in DPAs, NPAs, and other negotiated agreements has increased, so has scrutiny of monitor selection. Courts, in particular, have proven increasingly willing to wade into issues surrounding the selection of external monitors or the confidentiality of the work product they produce. A recent decision rendered by the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia in Tokar v. U.S. Department of Justice could have significant implications for the confidentiality of the monitor selection process and the privacy of the candidates considered for a monitor position.

The process by which corporate compliance monitors are selected has been governed since 2008 by the Morford Memorandum,[74] by which DOJ established a series of guidelines for the vetting and selection of corporate monitors in response to a perception that the process was marred by conflicts of interest and favoritism. According to this process, the government and corporate defendants are encouraged to consider a pool of “at least three qualified monitor candidates,” where practicable. Although the Morford Memorandum does not fully define the concept of a “qualified candidate,” it provides examples of the skills and expertise that might be useful in a monitor role, citing attorneys, as well as “accountants, technical or scientific experts, and compliance experts,” as backgrounds that could benefit a monitor.[75]

Critics, however, assert that, in practice, the monitor selection process remains opaque and continues to favor certain types of candidates over others. Some, including the plaintiff in the Tokar case, have alleged that DOJ skews towards selecting criminal defense lawyers, many of whom are former prosecutors, to the exclusion of career compliance professionals who have deep experience implementing compliance programs that prevent companies from being repeat offenders.[76]

In April 2015, journalist Dylan Tokar sought to investigate “manipulation” in the monitor selection process.[77] Tokar filed a Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”) request for records related to the vetting and selection of corporate compliance monitors in fifteen different FCPA settlements between DOJ and corporate defendants, including the names of monitor candidates.[78]

On December 8, 2016, Tokar filed suit in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia to compel a response to his FOIA request.[79] Six weeks later, DOJ provided Tokar with the information, but DOJ redacted the names and firms of candidates not selected for monitorships under FOIA exemptions 6, for “personnel and medical files and similar files the disclosure of which would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of personal privacy,” and 7(C), for records “compiled for law enforcement purposes . . . that could reasonably be expected to constitute an unwarranted invasion of personal privacy.”[80]

Both parties moved for summary judgment. DOJ argued that its redactions were justified by established FOIA exemptions to protect the privacy of third parties.[81] Contrarily, Tokar argued that DOJ’s redactions were impermissible under FOIA because “[t]he corporate compliance monitor candidates . . . have no privacy interest in the disclosure of their names and places of employment,” and regardless, the public interest in how DOJ enforces the anti-corruption laws outweighs any such privacy interest.[82]

In an opinion issued on March 29, 2018, Judge Rudolph Contreras ordered DOJ to release the names and firm affiliations of the monitorship candidates. Although the court acknowledged that individuals have “more than a de minimis privacy interest in their anonymity,” Judge Contreras concluded that “the public interest in learning these individuals’ identities outweighs that privacy interest, and therefore, the individuals’ names and firms must be released.”[83] He further noted that any “embarrassment” to the individuals whose names were revealed would be mitigated by those individuals’ freedom to choose whether to be considered for a monitorship in the first place.[84]

Panasonic Avionics Corporation (DPA)

Also relevant to monitor selection, DOJ’s April 30, 2018 DPA with PAC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Panasonic Corporation (“Panasonic”), contains a provision that, for the very first time, expressly instructs that compliance monitor selections “shall be made in keeping with the Department’s commitment to diversity and inclusion.”[85] According to a DOJ spokesperson, although the diversity provision was added to the DOJ Fraud Section’s standard template agreement in 2017, the April 30, 2018 DPA with PAC provided the first opportunity for it to be used.[86] The spokesperson explained that the provision is consistent with DOJ’s “long-standing policy” to “embrace[] diversity of opinion and background.”[87] The PAC DPA is discussed in greater detail immediately below.

Other Recent NPAs and DPAs

In addition to the agreements discussed at length in the preceding sections, the following NPAs and DPAs have been issued this year.

Cultural Resources Analysts, Inc. (DPA)

On February 5, 2018, Cultural Resource Analysts, Inc. (“CRA”) and DOJ entered into a DPA.[88] The DPA resolved violations of the Archaeological Resources Protection Act.[89] On December 22, 2017, the National Park Service issued a notice of violation to CRA for excavation activities that occurred on or around May 20, 2016, and August 8, 2017.[90] The government agreed to the DPA for a number of reasons, including CRA’s voluntary disclosure of the underlying conduct and CRA’s compliance with the procedures in the notice of violation.[91] As part of the DPA, CRA admitted responsibility for the conduct outlined in the notice of violation, agreed to pay a penalty of $15,024, agreed to return all artifacts discovered during the conduct, and agreed to obtain proper permits prior to the commencement of future projects.[92] In return, the government deferred prosecution of CRA and current and former directors, officers, and employees who admitted knowledge of the conduct and cooperated with the government.[93] We note that the CRA DPA unusually did not include a fixed term, and would therefore appear to apply indefinitely. The provision for deferred prosecution of individuals also is unusual in that DPAs more commonly expressly disclaim any deferral of individual prosecutions and require companies to cooperate with any government investigations of individual misconduct. This DPA is an excellent example of the myriad ways in which resolutions can be tailored to the specific needs of individual cases.

Imagina Media (NPA)

On July 10, 2018, DOJ announced an NPA with Imagina Media as part of a coordinated settlement with Imagina Media and its U.S. subsidiary, US Imagina, LLC.[94] In connection with allegations that two of US Imagina, LLC’s executives had paid more than $6.5 million in bribes to high-ranking officials in the Caribbean Football Union and four Central American national soccer federations to secure media and marking rights to those federations’ World Cup qualifier matches, U.S. Imagina, LLC pleaded guilty to a criminal information charging it with two counts of wire fraud conspiracy. Imagina Media entered into a related NPA in connection with the associated conduct of one of its co-Chief Executive Officers. Under the terms of the NPA, Imagina Media agreed to pay the criminal penalty of $21,883,320 imposed on Imagina US LLC as part of its plea agreement. The NPA was set for a term of three years.

Legg Mason (NPA)

On June 4, 2018, concurrently with the SocGen DPA, DOJ announced an NPA with Legg Mason, Inc.[95] Both resolutions stem from SocGen’s payment of more than $90 million to a Libyan intermediary, while allegedly knowing that the intermediary was using a portion of those payments to bribe Libyan government officials in connection with $3.66 billion in investments placed by Libyan state-owned banks with SocGen. A number of those investments were managed by a subsidiary of Legg Mason. The NPA, which secured a penalty from Legg Mason of $64.2 million, had a term of three years. For additional analysis of this agreement, please see our 2018 Mid-Year FCPA Update.

Panasonic Avionics Corporation (DPA)

On April 30, 2018, DOJ announced the PAC DPA, which resolved charges arising out of alleged criminal violations of the internal accounting controls and books and records provisions of the FCPA. To resolve the matter, PAC agreed to pay $137.4 million in criminal penalties.[96] In a related proceeding, Panasonic agreed to pay $143 million in disgorgement to the SEC, for a combined settlement amount of U.S. criminal and regulatory penalties of over $280 million.[97]

Notably, PAC received a 20% discount from the low end of the range suggested under the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines, even though it did not voluntarily self-disclose the misconduct. DOJ noted that this was attributable to PAC’s “cooperation and remediation, which, although untimely in certain respects, did include causing several senior executives who were either involved in or aware of the misconduct to be separated from PAC or Panasonic.”[98] Furthermore, in Panasonic’s $143 million civil settlement, the SEC noted that the parent company afforded cooperation to the SEC “in the later stages of the staff’s investigation,”[99] which suggests that the company may have been less cooperative during the early stages of the investigation. This outcome demonstrates a pattern that we have seen several times before in enforcement actions: that it is better late than never for companies to take steps toward full cooperation, and that even in the face of egregious conduct, companies can make a comeback with regulators through direct advocacy and open engagement coupled with substantive remediation.

As discussed above, the PAC DPA also is the only agreement in 2018 (to date) to impose a monitorship requirement. The PAC DPA imposed an independent compliance monitor for a period of two years, and also required an additional year of self-reporting to DOJ.[100]

Red Cedar Services, Inc. (NPA) and Santee Financial Services, Inc. (NPA)

In April 2018, DOJ entered into separate NPAs with two companies, Red Cedar Services, Inc. (“Red Cedar”) and Santee Financial Services, Inc. (“STS”), relating to charges arising under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (“RICO”), and allegations relating to wire fraud and anti-money laundering.[101] Notably, the NPAs arise from the same predicate investigation as the USB DPA. Both Red Cedar and STS—corporations established by Indian tribes (the Modoc Tribe of Oklahoma and the Santee Sioux Tribe of Nebraska, respectively)—allegedly entered into business agreements concerning payday lending with an individual named Scott Tucker and various entities controlled by Tucker.[102] Under the payday lending agreements, Tucker and the entities controlled by Tucker allegedly provided capital to make loans and allegedly opened, or caused to be opened, bank accounts in the names of entities controlled by Red Cedar and STS, without meaningful involvement by these entities.[103] In return for monthly payments, Tucker allegedly used the agreements with these entities to evade state usury laws using claims of sovereign immunity. The NPA Statements of Fact further alleged that, in related state court litigation concerning Tucker’s payday lending business, representatives of the Modoc and Santee tribes submitted false affidavits overstating the involvement of the tribes in Tucker’s loan business.[104] As a condition of its NPA, Red Cedar agreed to forfeit $2 million; STS agreed to forfeit $1 million. The NPAs both were set for a term of one year.[105]

Rite Aid Corporation (NPA)

On January 24, 2018, DOJ announced an NPA with national pharmacy chain Rite Aid Corporation (“Rite Aid”) to resolve potential criminal charges arising under the Controlled Substances Act (“CSA”) from Rite Aid’s alleged improper sale of pseudoephedrine (“PSE”), a common precursor in the production of methamphetamine, between January 2009 and October 2012.[106] The NPA noted that Rite Aid sold over 850,000 grams of PSE for over $5 million during that time period, and that Rite Aid failed to adequately train its employees in the responsible sale of PSE products to ensure not only that PSE buyers did not exceed applicable purchase limits, but that Rite Aid employees denied sales to persons they suspected not to have a legitimate medical purpose for purchasing PSE products.[107]

As part of the settlement, Rite Aid accepted full responsibility for its role in these improper sales, and agreed to pay a total of $4 million in restitution, representing approximately 80% of its gross sales of PSE in West Virginia during the subject period.[108] Notably, the entire $4 million penalty was designated for agencies in West Virginia, with $2.6 million going to the West Virginia Crime Victims Compensation Fund and the remaining $1.4 million allocated to the West Virginia Department of Health and Human Resources, which specifically agreed as a condition of its participation in the settlement that these funds would be used to fund substance abuse treatment within the state.[109]

Among the factors the U.S. Attorney’s Office cited in support of this settlement were Rite Aid’s willingness to accept full responsibility for its actions and the considerable remediation efforts Rite Aid had undergone since October 2012, which it promised to continue as part of the agreement. These efforts included (1) selling only tamper-resistant single-ingredient PSE products; (2) keeping PSE products out of view of customers; (3) selling PSE products only in the pharmacy area; (4) screening PSE sales via a centralized computer system; and (5) training store employees on how to identify suspicious PSE customers and encouraging them to report suspicious activity involving PSE sales to the authorities.[110]

Notably, resolutions under the CSA generally are civil rather than criminal in nature, making the Rite Aid NPA highly unusual. Indeed, we are aware of only one other agreement—an NPA with the United Parcel Service, Inc., in 2013—that addressed potential criminal misconduct under the CSA. More commonly, DOJ elects for civil charges and a large financial settlement. On January 17, 2017, for example, DOJ announced that DOJ and the Drug Enforcement Administration had entered a record $150 million civil settlement and five-year compliance monitorship with McKesson Corporation, one of the nation’s largest drug distributors, for allegedly failing to implement and maintain an effective compliance program for detecting and responding to suspicious orders of controlled substances.[111]

International DPA Developments

As use of corporate NPAs and DPAs has become more established in the United States, countries around the globe have increasingly looked to the U.S. model, and derivative models like the United Kingdom’s DPA regime, in expanding their own resolution toolboxes. This section first provides updates from the United Kingdom, which was second to adopt DPAs as a means for resolving corporate enforcement actions, and France, which formally established its own DPA-like program just last year. It then briefly surveys developments around the globe—from Canada to Switzerland—in countries that have adopted, or are considering adopting, similar regimes.

United Kingdom

Although the U.K. Serious Fraud Office (“SFO”) has not entered into any new DPAs during the first six months of 2018, agency officials have made clear that “[w]e are open for business” with “no shortage of work in the pipeline.”[112] In June 2018, the U.K. Attorney General’s Office named a new Director of the SFO, Lisa Osofsky, who will officially assume the role on September 3, 2018.[113] Until then, Interim Director Mark Thompson will “maintain business as usual at the SFO and continue the mandate set by the previous Director.”[114]

Recent remarks from prominent SFO officials suggest that this mandate will include upholding the agency’s firm cooperation requirement for achieving a DPA. In June, Camilla de Silva, Joint Head of Bribery and Corruption, provided an anti-corruption enforcement update at the Herbert Smith Freehills Corporate Crime Conference 2018. During her speech, de Silva emphasized the importance of legitimate cooperation for companies hoping to secure a DPA in lieu of prosecution, stating that “[t]he SFO will only invite a company to enter into an agreement to defer prosecution where the company has genuinely cooperated with the SFO.”[115] Because, in the SFO’s view, a DPA is advantageous in that it allows a company to avoid a criminal conviction and associated collateral consequences, de Silva explained that the bar to securing a DPA is “necessarily a high one.”[116]

During another speaking engagement earlier this year, de Silva provided insight into the SFO’s expectations for corporate cooperation. First, the SFO considers when the company first contacted the SFO.[117] She described DPAs as “a reward for openness – the sooner you come in, self-report and the more you are open with us, the more you have to be rewarded for.”[118] Second, the SFO evaluates the company’s internal investigation efforts, including the willingness of the company to provide the SFO with access to the results of the internal investigation, the thoroughness of the work completed to date, and the collection and preservation of relevant data.[119] With regard to self-reporting, we note that the neither the SFO nor the judiciary historically has uniformly required self-reporting for corporations hoping to secure a DPA; rather, self-reporting historically has been a highly important, but not a definitive, factor.[120]

During the 12th International Pharmaceutical and Medical Device Compliance Congress in May, de Silva also highlighted the importance of remediation in the DPA context, including making relevant changes to a company’s compliance program and removing responsible senior employees.[121] When the SFO is evaluating whether to offer a DPA as a resolution, she explained, evidence that the company has “address[ed] past inadequacies by taking steps to remediate [. . .] would be a positive consideration.”[122]

France

In our 2017 Year-End Update, we discussed France’s first application of the corporate settlement provision in France’s Law on Transparency, Fight Against Corruption and Modernization of Economic Life (Loi relatif à la transparence, à la lutte contre la corruption et à la modernisation de la vie économique) (“Sapin II”).[123] We previously covered the development of this long-anticipated legislation in our 2016 Mid-Year Update and 2016 Year-End Update.

One key provision of Sapin II allows the Public Prosecutor (procureur de la République) to offer legal entities an agreement known as a Convention judiciaire d’intérêt public (“CJIP”) in lieu of court proceedings when the investigating magistrate has found a sufficient factual basis for imposing liability and the legal entity recognizes responsibility for its acts.[124]

As discussed in our 2017 Year-End Update, the National Financial Prosecutor of France announced the first negotiated resolution under Sapin II on November 28, 2017, with a Swiss subsidiary of HSBC. Since that inaugural agreement, France has utilized CJIP agreements four times to settle charges arising from two investigations. Three companies, as discussed further below, agreed to monitors as part of CJIPs.

Agreements with Kaeffer Wanner, Set Environment, and SAS Poujaud

Three of the four agreements entered thus far in 2018 stemmed from allegations that certain French companies agreed to pay bribes to an employee of Electricité de France (“EDF”), a French public utility company, in exchange for new or renewed government contracts. The investigation into these allegations was prompted by a whistleblower tip to EDF, that one of its employees was requesting and accepting commissions in exchange for allocating or retaining public contracts. In July 2011, after EDF received the whistleblower tip and conducted an initial internal investigation, it reported the allegations to French police. French prosecutors initiated a preliminary inquiry shortly thereafter.

In February 2012, the employee of EDF who allegedly solicited or accepted the bribes was formally placed under criminal investigation for corruption charges.[125] Subsequently, the investigation allegedly established that certain French companies, including Kaeffer Wanner (“KW”), Set Environment (“Set”), and SAS Poujaud (“Poujaud”) agreed to pay bribes to this employee to continue their contracts with EDF. KW, Set, and Poujaud acknowledged their responsibility for the activities giving rise to the charges of active public corruption brought against them and agreed to enter into CJIP agreements with PNF.[126] The companies were fined up to the amount of the benefits that resulted from the aforementioned alleged bribes, within a cap of 30% of their average revenue calculated over the previous three years.[127]

In addition to fines, KW and Set agreed to monitorships by the French anti-corruption authority AFA, an agency created in 2017 under Sapin II. Unlike in the United States where enforcement agencies do not directly oversee the monitor’s day-to-day work, AFA agents and experts appointed by AFA directly operate monitorships in France. Although the prosecutor determined that KW already had a compliance program in place, the CJIP nevertheless required that KW submit to an eighteen-month monitorship to ensure adherence to the existing compliance program. Set agreed to a two year monitorship. Under the terms of the CJIPs, each company will bear the monitoring costs, up to €290,000 (approximately $340,655) for KW and up to €200,000 (approximately $234,935) for Set. In a recent interview with Global Investigations Review, AFA compliance expert Julien Laumain reported that these monitorships are underway. Although AFA’s approach remains a “work in progress,” Laumain outlined AFA’s five-stage monitorship process: (1) an “inventory of the company’s anti-corruption system” performed by AFA agents and resulting in a Phase 1 report issued within three months; (2) a company-proposed action plan—provided within six months—to improve the company’s anti-corruption compliance program; (3) AFA’s one-month review and consideration of the action plan; (4) company implementation of the action plan, including quarterly reviews by AFA and reports to prosecutors that entered into the CJIP; and (5) a final audit report prepared by AFA, including an assessment of whether the company has met AFA’s anti-corruption compliance goals.[128] Laumain also remarked on France’s involvement in foreign monitorships, including requirements that French companies subject to a U.S. monitor provide information to AFA first.[129]

Set and KW agreed to the CJIPs on February 14 and 15, 2018, respectively, and the Vice President of the High Court of Nanterre approved both CJIPs on February 23, 2018.[130] The CJIPs and the High Court’s decisions became binding and public on March 7, 2018, after the expiration of the ten-day opt-out period. The CJIP with Poujaud was concluded on May 7, 2018, and approved by the Vice President of the High Court of Nanterre on May 25, 2018.[131] The CJIPs and the High Court’s decisions became binding and public on June 4, 2018.

CJIP Agreement with Société Générale SA

PNF reached a CJIP agreement with French Bank SocGen to settle claims that SocGen paid bribes to obtain investments from Libyan state-owned financial institutions. Under the CJIP agreement, which was ratified by PNF on May 24, 2018, SocGen agreed to pay penalties of €250,150,755 (approximately $289,367,252).[132] SocGen also agreed to implement a compliance program and cooperate with a two-year compliance monitorship supervised by AFA. SocGen will pay up to €3,000,000 (approximately $3,524,022) for the cost of the monitor. The President of the High Court of Paris (Tribunal de grande instance de Paris) approved the CJIP agreement on June 4, 2018, and it became public ten days later at the conclusion of the opt-out period.[133]

The CJIP agreement with SocGen was announced in conjunction with a settlement reached between SocGen, DOJ, and the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission (“CFTC”). The agreement with DOJ is discussed in a preceding portion of this Update.

Canada’s “Remediation Agreement Regime”

Last year, as addressed in our 2017 Year-End Update, the Government of Canada concluded a public comment period regarding the possible adoption of a DPA regime. At the close of this process, the Canadian legislature introduced an amendment in March 2018 to create a so-called “made-in-Canada” version of a DPA program, called a Remediation Agreement Regime.[134] The legislation was introduced in conjunction with an announcement regarding changes to the already-existing Integrity Regime, which provides for potential debarment from contracting of government suppliers that have been charged or admitted guilt of the offences identified in Canada’s Ineligibility and Suspension Policy.[135] These two measures are intended to work together to create “incentives for corporations to self-report and [to] encourage[] stronger corporate compliance.”[136] The bill introducing the Remediation Agreement Regime was passed by both houses of Parliament and received Royal Assent on June 21, 2018.[137]

According to the new legislation, and in line with nearly all comments received by the Government during the public comment period,[138] remediation agreements will only be available to organizations; individuals are ineligible.[139] One question addressed in the Government’s discussion paper was what factors should be considered relevant for DPA negotiation purposes.[140] Many of the factors that were offered by participants in the process made it into the text of the law, which states that a prosecutor must consider the following factors when deciding whether to offer a remediation agreement:

(a) the circumstances in which the act or omission that forms the basis of the offence was brought to the attention of investigative authorities; (b) the nature and gravity of the act or omission and its impact on any victim; (c) the degree of involvement of senior officers of the organization in the act or omission; (d) whether the organization has taken disciplinary action, including termination of employment, against any person who was involved in the act or omission; (e) whether the organization has made reparations or taken other measures to remedy the harm caused by the act or omission and to prevent the commission of similar acts or omissions; (f) whether the organization has identified or expressed a willingness to identify any person involved in wrongdoing related to the act or omission; (g) whether the organization—or any of its representatives—was convicted of an offence or sanctioned by a regulatory body, or whether it entered into a previous remediation agreement or other settlement, in Canada or elsewhere, for similar acts or omissions; (h) whether the organization — or any of its representatives — is alleged to have committed any other offences, including those not listed in the schedule to this Part; and (i) any other factor that the prosecutor considers relevant.[141]

Although the final factor appears to be a “catch-all,” the law explicitly states that, “if the organization is alleged to have committed an offense under section 3 or 4 of the Corruption of Foreign Public Officials Act,” which covers bribing foreign public officials—much like the FCPA in the United States—the prosecutor “must not consider the national economic interest, the potential effect on relations with a state other than Canada[,] or the identity of the organization or individual involved.”[142]

The new law states that a remediation agreement requires judicial approval, and that approval must be granted if the court finds that the agreement is in the public interest, and the terms of the agreement are fair, reasonable and proportionate.[143] At the end of the term of the DPA, if the accused organization has complied with the terms and conditions of the agreement, the prosecutor applies to the judge for an order of successful completion.[144] The judge issues an order stating that the terms of the agreement have been met.[145] Accordingly, “[t]he order stays the proceedings against the organization for any offence to which the agreement applies, the proceedings are deemed never to have been commenced and no other proceedings may be initiated against the organization for the same offence.”[146]

The approving court has the discretion to decide not to publish the remediation agreement and subsequent order “if it is satisfied that the non‑publication is necessary for the proper administration of justice.”[147] In deciding whether this standard is satisfied, the court is instructed to consider, among other factors, “society’s interest in encouraging reporting . . . and the participation of victims in the criminal justice process,” “whether it is necessary to protect the identify” of any individuals involved, and the potential adverse impact on the Government’s investigation or prosecution.[148]

Although the terms of the agreement will vary based on the circumstances, certain terms are required in all agreements, such as a statement of facts and an admission of responsibility.[149] Terms must also include the organization’s obligation to cooperate in the Government’s investigation, to forfeit any gains based on the alleged conduct, and to make reparations and pay a penalty.[150] Although not mandatory, a remediation agreement could appoint an independent monitor “to verify and report to the prosecutor on the organization’s compliance.”[151]

The new Remediation Agreement Regime will come into effect on September 18, 2018, 90 days after it received Royal Assent.[152]

Poland

In May of this year, Poland’s Ministry of Justice proposed legislation that would drastically alter prosecutors’ ability to charge corporations with violations of the Polish criminal code while also allowing corporate defendants to resolve such charges through U.S.-style DPAs.

Under current Polish law, corporations may be criminally charged only if a “related” individual has previously been convicted of one of the specific offenses enumerated in the relevant statute.[153] Polish law gives broad meaning to those individuals who qualify as “related” for purposes of attributing liability to the corporation, and the theoretical limits of this potential corporate liability under Polish law approach the very broad contours of respondeat superior liability in the United States. Assuming this prerequisite can be met, corporations can then be prosecuted if they derived some form of economic benefit, even indirectly, from the individual’s actions and failed to exercise sufficient diligence in selecting or supervising him or her.[154] Under the proposed legislation, however, corporations may be charged independently of any prosecutions of relevant individuals.[155] Furthermore, prosecutors could charge corporations for a variety of categories of criminal offenses, as opposed to simply those enumerated in the actual legislation.[156] In addition, the draft statute increases the maximum penalty that could be imposed upon corporations from the current cap of zł5 million to zł30 million (from approximately $1.3 million to $8 million).[157] Finally, failure to internally investigate whistleblower reports and remediate any issues identified would, under the new legislation, result in a zł60 million (approximately $16 million) increase in any potential fine.[158] Nevertheless, the proposed legislation offers opportunities for potential corporate defendants to mitigate their exposure. Not unlike in the United States and now the United Kingdom, if a corporation self-discloses misconduct, provides authorities with evidence related to specific individuals implicated in that misconduct, agrees to compensate any victims of wrongdoing, and pays a penalty of up to zł3 million (approximately $801,258), authorities have the discretion to suspend the prosecution.[159]

Singapore

On March 19, 2018, the Singapore Parliament passed the Criminal Justice Reform Act, which, among other things, introduces a DPA regime to the jurisdiction for the first time.[160] As with DPAs in the United States (as well as other jurisdictions), the newly introduced DPA framework gives prosecutors in Singapore the ability to choose not to pursue charges on the condition that the suspected party agrees to certain measures, such as the payment of financial penalties, the implementation of appropriate compliance regimes, and continued cooperation in investigations.[161] In addition, as in the United States, the Singaporean DPAs are designed to act as an inducement for corporations to voluntarily disclose any issues that they discover, and to cooperate fully with investigative authorities, in return for the opportunity to avoid a criminal conviction.

Beyond the general framework, however, there are a number of differences between the DPA regimes in Singapore and the United States. To begin with, DPAs in Singapore will only be available for specific offenses, including corruption, money laundering, and receipt of stolen property offenses, but not the primary fraud offense of “cheating” (similar to common law fraud).[162] Moreover, as with DPAs in the United Kingdom, Singapore’s DPAs only apply to corporate bodies,[163] as opposed to individuals, and the terms the DPA must be approved by the Singaporean High Court with a judge satisfied that the DPA is “in the interests of justice,” and that the terms are “fair, reasonable and proportionate.”[164] The court’s approval of a DPA is a matter of public record, as are the terms of the agreement and the facts of the underlying conduct.

Singapore’s introduction of DPAs comes in response to Singapore’s first major corruption case, which involved Keppel and its U.S. subsidiary. In December 2017, Keppel agreed to pay a total penalty of more than $422 million to resolve corruption charges relating to bribes allegedly paid in Brazil.[165] The terms of the penalty were set out in a DPA with DOJ, which required Keppel to pay $211 million in criminal penalties in Brazil, and $105 million each to the United States and Singapore.[166] At the time, Indranee Raja, a member of the Singaporean Parliament, noted that the global resolution coordinated among the United States, Brazil, and Singapore allowed for a greater penalty to be levied against Keppel than would have been possible if Singapore had prosecuted the case itself, because the maximum penalty under Singapore’s Prevention of Corruption Act was only $75,000. She also noted that the U.S. DPA required Keppel to introduce an enhanced compliance program.[167] Singapore’s new DPA framework does not include a statutory limit on financial penalties.

Switzerland

In March 2018, the Swiss Office of the Attorney General (“OAG”) presented a proposal to develop a framework for DPAs in Switzerland.[168] After a public consultation period, the proposal was presented to the Swiss parliament, where it is currently pending review.[169]

The OAG’s proposal largely mimics the U.S. model. It provides that after the completion of an investigation, if the conditions for an indictment are fulfilled, the prosecutor can enter into an agreement to defer prosecution, provided that the company fully cooperated throughout the investigation and has cooperated in the identification of the relevant individual(s) responsible for the offense.[170] The DPA should include the following types of information: (1) a statement of the underlying facts which must be acknowledged by the company; (2) the amount of the fine(s) to be paid or assets to be released or confiscated; (3) a summary of the company’s efforts and internal controls to prevent future offenses; (4) the appointment of an independent auditor at the company’s expense to monitor implementation of internal control measures; (5) provision for periodic reports by the independent auditor to the prosecutor; (6) determination of a “probation period” of two to five years; and (7) specified consequences for violation of terms of the agreement.[171] The proposed agreement template provides that if a company violates the agreement during the probation period and does not take timely remedial measures, the prosecutor will indict the company in the competent court. However, if the company fulfills the agreement during the probation period, the prosecutor will terminate the proceedings.

Swiss Federal Prosecutor Michael Lauber has spoken out in favor of the proposals, noting a need for “new instruments in large-scale proceedings” because current proceedings “take far too long and are very difficult to manage.”[172] The Federal Prosecutor’s Office generally supports the proposed DPAs, but only in situations where the investigation has concluded and the company cooperates, recognizes the allegations, pays fines and compensatory costs, and commits to improving internal controls with help from external oversight.[173] Critics of the proposal fear unequal treatment if some companies are allowed to enter DPAs while others are denied that option and must proceed to resolution through the courts. An additional criticism is that the availability of DPAs could incentivize companies to turn certain individuals into scapegoats while avoiding conviction themselves.[174] Critics are also concerned about companies escaping liability by “buy[ing] their way out” of a public trial.[175]

________________________________

APPENDIX: 2018 YTD Non-Prosecution and Deferred Prosecution Agreements

The chart below summarizes the agreements concluded by DOJ to date in 2018. As noted above, as in 2017, the SEC has not entered into any NPAs or DPAs in 2018. The complete text of each publicly available agreement is hyperlinked in the chart.

The figures for “Monetary Recoveries” may include amounts not strictly limited to an NPA or a DPA, such as fines, penalties, forfeitures, and restitution requirements imposed by other regulators and enforcement agencies, as well as amounts from related settlement agreements, all of which may be part of a global resolution in connection with the NPA or DPA, paid by the named entity and/or subsidiaries. The term “Monitoring & Reporting” includes traditional compliance monitors, self-reporting arrangements, and other monitorship arrangements found in settlement agreements.

| U.S. Deferred and Non-Prosecution Agreements in 2018 YTD | ||||||

| Company | Agency | Alleged Violation | Type | Penalty/Fine | Monitoring & Reporting | Term of DPA/ NPA (months) |

| Credit Suisse (Hong Kong) Limited | DOJ Fraud; E.D.N.Y. | FCPA | NPA | $47,029,916 | Yes | 36 |

| Cultural Resource Analysts, Inc. | M.D. Tenn. | Archaeological Resources Protection Act | DPA | $15,024 | No | Indefinite |

| HSBC Holdings plc | DOJ Fraud | Fraud (Wire Fraud) | DPA | $109,579,000 | Yes | 36 |

| Imagina Media Audiovisual SL | E.D.N.Y. | FCPA | NPA | $12,883,320 | Yes | 36 |

| Legg Mason, Inc. | E.D.N.Y. | FCPA | NPA | $64,242,000 | Yes | 36 |

| Panasonic Avionics Corporation | DOJ Fraud | FCPA | DPA | $280,602,831 | Yes | 36 |

| Red Cedar Services, Inc. | S.D.N.Y. | RICO Act; Fraud (Wire Fraud); AML | NPA | $2,000,000 | No | 12 |

| Rite Aid Corporation | S.D. W. Va. | Controlled Substances Act | NPA | $4,000,000 | No | 24 |

| Santee Financial Services, Inc. | S.D.N.Y. | RICO Act; Fraud (Wire Fraud); AML | NPA | $1,000,000 | No | 12 |

| Société Générale S.A. | DOJ Fraud; E.D.N.Y. | FCPA; Transmitting false commodities reports | DPA | $1,335,552,888 | Yes | 36 |

| Transport Logistics International, Inc. | DOJ Fraud; D. Md. | FCPA | DPA | $2,000,000 | Yes | 36 |

| U.S. Bancorp | S.D.N.Y. | BSA | DPA | $613,000,000 | Yes | 24 |

[1] NPAs and DPAs are two kinds of voluntary, pre-trial agreements between a corporation and the government, most commonly DOJ. They are standard methods to resolve investigations into corporate criminal misconduct and are designed to avoid the severe consequences, both direct and collateral, that conviction would have on a company, its shareholders, and its employees. Though NPAs and DPAs differ procedurally—a DPA, unlike an NPA, is formally filed with a court along with charging documents—both usually require an admission of wrongdoing, payment of fines and penalties, cooperation with the government during the pendency of the agreement, and remedial efforts, such as enhancing a compliance program and—on occasion—cooperating with a monitor who reports to the government. Although NPAs and DPAs are used by multiple agencies, since Gibson Dunn began tracking corporate NPAs and DPAs in 2000, we have identified approximately 485 agreements initiated by the DOJ, and 10 initiated by the SEC.

[2] Press Release, U.S. Sec. & Exch. Comm’n, SEC Proposes Whistleblower Rule Amendments (Jun. 28, 2018), https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2018-120. The current rules are silent on whether NPA and DPA recoveries may form the basis of a whistleblower award; the proposed rule would modify the definition of “action” under Regulation 21F-4(d) to include NPAs and DPAs, and “monetary sanction” under Regulation 21F-4(e) to include money paid pursuant to such agreements.

[3] U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Remarks of Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein, “Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein Delivers Remarks to the New York City Bar White Collar Crime Institute” (May 9, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/deputy-attorney-general-rod-rosenstein-delivers-remarks-new-york-city-bar-white-collar [hereinafter Rosenstein Speech].

[4] See Deputy Attorney General of the United States, Memorandum re Policy on Coordination of Corporate Resolution Penalties (May 9, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/file/1061186/download [hereinafter Rosenstein Memorandum].

[5] Rosenstein Speech, supra note 3.

[6] Id.

[7] Rosenstein Memorandum, supra note 4.

[8] Rosenstein Speech, supra note 3.

[9] Id.

[10] Id.

[11] Id.

[12] Id.

[13] Id.

[14] Deferred Prosecution Agreement, United States v. HSBC Holdings PLC, No. 1:18-cr-00030 (E.D.N.Y. Jan. 18, 2018) [hereinafter HSBC DPA]; see also Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, HSBC Holdings Agrees to Pay More than $100 Million to Resolve Fraud Charges (Jan. 18, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/hsbc-holdings-plc-agrees-pay-more-100-million-resolve-fraud-charges.

[15] HSBC DPA, supra note 14, at 1.

[16] Id. at 3–4.

[17] Id. at 3.

[18] Id. at 8–9.

[19] Id. at 9.

[20] Id.

[21] Deferred Prosecution Agreement, United States v. U.S. Bancorp, No. 18-cr-150 (S.D.N.Y. Feb. 12, 2018), [hereinafter U.S. Bancorp DPA]; see also Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Manhattan U.S. Attorney Announces Criminal Charges Against U.S. Bancorp for Violations of the Bank Secrecy Act (Feb. 15, 2017), https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdny/pr/manhattan-us-attorney-announces-criminal-charges-against-us-bancorp-violations-bank.

[22] U.S. Bancorp DPA, supra note 21, at 1.

[23] Id. at 2, 13; In re U.S. Bank Nat’l Assn., Cincinnati, OH, AA-EC-2018-84, Art. II (Feb. 13, 2018).

[24] Deferred Prosecution Agreement, United States v. Société Générale S.A., No. 18-CR-253, (E.D.N.Y. June 5, 2018) [hereinafter SocGen DPA].

[25] Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Société Générale S.A. Agrees to Pay $860 Million in Criminal Penalties for Bribing Gaddafi-Era Libyan Officials and Manipulating LIBOR Rate (June 4, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/soci-t-g-n-rale-sa-agrees-pay-860-million-criminal-penalties-bribing-gaddafi-era-libyan.

[26] Id.

[27] Michael Griffiths, Global Investigations Review Just Anti-Corruption, French compliance monitorships a “work in progress” (Jul. 9, 2018), https://globalinvestigationsreview.com/article/1171535/french-compliance-monitorships-a-work-in-progress.

[28] See United States v. HSBC Bank USA, N.A. et al., 12-CR-763, 2016 WL 34670 (E.D.N.Y. Jan. 28, 2016), rev’d 863 F.3d 125 (2d Cir. 2017); United States v. Fokker Servs. B.V., 79 F. Supp. 3d 160 (D.D.C. 2015), rev’d 818 F.3d 733 (D.C. Cir. 2016).

[29] Arraignment at 8–9, United States v. U.S. Bancorp, No. 18-cr-150 (S.D.N.Y. Feb. 22, 2018), ECF No. 9.

[30] Id.

[31] Id. at 10.

[32] Transcript of Proceedings – Motions Hearing at 16–17, United States v. Transp. Logistics Int’l, Inc., No. 8:18-cr-00011-TDC (D. Md. Mar. 12, 2018), ECF No. 9.

[33] Order at 2, United States v. Transp. Logistics Int’l, Inc., No. 8:18-cr-00011-TDC (D. Md. Apr. 2, 2018), ECF No. 10.

[34] Id. at 2–3 (quoting United States v. Fokker Servs. B.V., 818 F.3d 733, 744 (D.C. Cir. 2016)).

[35] See Warin, Diamant, and Farrar, All in the Nuance, Corporate NPA and DPA (March 2018) at 2 (noting that, according to the U.S. Attorneys’ Manual, prosecutors should consider “the adequacy of prosecution of individuals responsible for corporate malfeasance” in making charging decisions).

[36] See id. at 3 (noting that the U.S. Attorneys’ Manual acknowledges the potential importance of a corporation’s cooperation in “identifying potentially relevant actors and locating relevant evidence . . . and in doing so expeditiously”).

[37] Elizabeth Warren Unveils Legislation to Hold Wall Street Executives Criminally Accountable, Corporate Crime Reporter (Mar. 14, 2018), https://www.corporatecrimereporter.com/news/200/elizabeth-warren-unveils-legislation-hold-wall-street-executives-criminally-accountable/.

[38] Press Release, Elizabeth Warren, On Tenth Anniversary of Financial Crisis, Warren Unveils Comprehensive Legislation to Hold Wall Street Executives Criminally Accountable (Mar. 14, 2018), https://www.warren.senate.gov/newsroom/press-releases/on-tenth-anniversary-of-financial-crisis-warren-unveils-comprehensive-legislation-to-hold-wall-street-executives-criminally-accountable.

[39] Ending Too Big to Jail Act, S. 2544, 115th Cong. § 4 (2018), https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/115/s2544.

[40] Id.

[41] Id.

[42] Id.

[43] Press Release, Elizabeth Warren, On Tenth Anniversary of Financial Crisis, Warren Unveils Comprehensive Legislation to Hold Wall Street Executives Criminally Accountable (Mar. 14, 2018).

[44] Mehrsa Baradaran, Commentary: Why We Need to Stop Fining Big Banks Like Wells Fargo, Fortune (Apr. 23, 2018), http://fortune.com/2018/04/23/wells-fargo-1-billion-fine-financial-regulation/.

[45] Peter Henning, Why Elizabeth Warren’s Effort to Hold Bank Executives Accountable May Fall Short, NY Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/03/business/dealbook/elizabeth-warrens-bank-executives-accountability.html.

[46] Deferred Prosecution Agreement, at 2­–3, 12, United States v. Sociedad Química y Minera de Chile, No. 1:17-cr-00013-TSC (D.D.C. Jan. 13, 2017) [hereinafter SQM DPA].

[47] Id. at 4.

[48] Deferred Prosecution Agreement at 2­–3, 12, United States v. Panasonic Avionics Corp., No. 1:18-cr-00118-RBW (D.D.C. Apr. 30, 2018) [hereinafter Panasonic DPA].

[49] Id. at 4.