January 4, 2018

Only two years removed from the height of corporate non-prosecution agreement (“NPA”) and deferred prosecution agreement (“DPA”) use by U.S. enforcement agencies,[1] 2017 saw their usage decline to the lowest levels in recent history, with statistics mirroring those at the peak of the global economic recession toward the end of the last decade. Rather than a shift in enforcement policy, however, we continue to believe that this is largely a sign—as it was in 2009—of a new administration in transition and the cyclic nature of prosecution. The U.S. government signaled repeatedly in 2017 that NPAs and DPAs remain favored tools for resolving complex corporate enforcement matters in the United States. The global trend toward adoption of similar DPA regimes also continues apace.

This client alert, our nineteenth semiannual update on NPAs and DPAs (1) analyzes NPAs and DPAs of 2017 and compares these to prior years’ statistics and practices; (2) spotlights a particularly interesting NPA with the National Security Division of the U.S. Department of Justice (“DOJ”); (3) discusses changes in white collar enforcement priorities and their likely impacts on NPAs and DPAs; (4) highlights recent developments in court preservation of corporate monitor report privacy; and (5) provides updates regarding DPA developments across the globe, including in the United Kingdom, France, and Canada.

NPAs and DPAs in 2017

In 2017, DOJ entered into 22 NPAs and DPAs, and the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) entered into none. The overall trend of NPA and DPA resolutions reflects the episodic nature of enforcement. 2017 saw the lowest levels of corporate NPA and DPA use since 2009, when we recorded 22 publicly released NPAs and DPAs with U.S. enforcement agencies. This figure, however, does not necessarily signal changing enforcement priorities; in our experience, the dedicated investigation and trial attorneys of DOJ and the SEC have continued to zealously investigate alleged corporate offenses, and none have signaled a move away from NPAs and DPAs as available resolution vehicles. To the contrary, this year’s NPAs and DPAs—particularly the resolution with Netcracker Technology Corp. (“NTC”), discussed in the sections that follow—indicated a continued willingness by DOJ to use these tools creatively to develop nuanced resolutions for corporate enforcement actions. 2017 continued to see these resolution vehicles proliferate throughout the United States, from West Virginia to Utah, and for crimes as varied as obstructing the Internal Revenue Service to Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act violations.

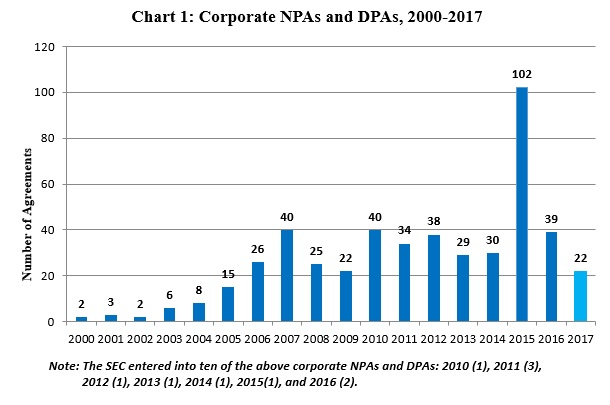

Chart 1 below shows all known corporate NPAs and DPAs since 2000.[2]

Of this year’s 22 NPAs and DPAs, 11 are NPAs and 11 are DPAs. DOJ’s Fraud Section, which entered into six of the agreements, including several of the highest-penalty agreements, entered into one publicly available NPA in 2017. This is particularly notable in light of the Fraud Section’s recent emphasis on declinations in the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (“FCPA”) context for companies meeting certain disclosure, cooperation, and remediation criteria set forth in the Fraud Section’s FCPA Enforcement Plan and Guidance Pilot Program of April 5, 2016 (the “Pilot Program”).[3] As discussed further below, DOJ has recently highlighted the successes of the Pilot Program—which was enhanced and made permanent this year[4]—in securing declinations for companies in 2017;[5] it is possible that certain companies that previously would have received NPAs are benefitting from the FCPA Enforcement Plan and Guidance and instead receiving declinations, or declinations-plus-disgorgement letters (discussed at length in our 2016 Year-End and 2017 Mid-Year Updates). In 2016, by way of comparison, when implementation of the FCPA Enforcement Plan and Guidance was in its infancy, the Fraud Section entered into nine NPAs and DPAs, of which three were NPAs.[6] We note that the tremendous overall spike in 2015 is attributable to the DOJ Tax Division’s Program for NPAs or “Non-Target Letters” for Swiss Banks, discussed in our 2015 Mid-Year and Year-End Updates, which invited banks to self-disclose tax-related conduct (and pay associated penalties) in exchange for NPAs.

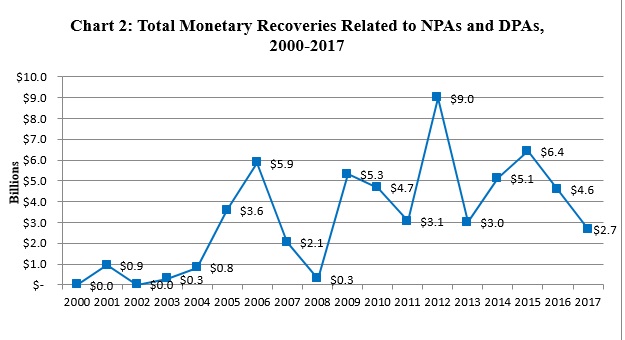

Chart 2 below illustrates the total monetary recoveries related to NPAs and DPAs from 2000 through 2017. Consistent with the lower overall yield of NPAs and DPAs, 2017’s recoveries were lower than in recent years, netting approximately $2.7 billion.

The Netcracker Technology Corp. NPA

One agreement in particular, DOJ’s National Security Division’s NPA with global software company NTC,[7] is an especially interesting example of how NPAs and DPAs may be tailored creatively to resolve government investigations into corporate conduct. NTC is a Massachusetts-based subsidiary of NEC Corporation.[8] To resolve allegations relating to security measures implemented by NTC in connection with two projects for the Defense Information Systems Agency, the National Security Division imposed unique penalties and terms—and included similarly unique “carrot” provisions—in the NTC NPA to help ensure NTC’s compliance.

First, and most strikingly, the NTC agreement contained an express disavowal of guilt by NTC; the statement of facts appended to the NPA stated that “[a]lthough NTC denie[d] that it engaged in any criminal wrongdoing,” NTC agreed to the statement of facts “in the interest of reaching a mutual agreement to resolve the investigation and enhance U.S. national security.”[9] This is highly unusual, but is bolstered by another example from the Middle District of Pennsylvania. The U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Middle District of Pennsylvania’s NPAs with Breakthru Beverage Pennsylvania; Southern Glazer’s Wine and Spirits of Pennsylvania, LLC; White Rock Distilleries, Inc.; and Pio Imports, LLC, which involved alleged bribery of public officials, similarly included disavowals of criminal liability by these companies.[10] These NPAs also, however, included statements to the effect that senior supervisors, senior officials, and/or employees of the Company “provided and were aware that [the Company] was engaged in a practice of providing things of value to [Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board] decision makers who were involved in making decisions beneficial to the Company,”[11] and separate acknowledgements that “the USAO-MDPA believes that the facts described in the Statement of Facts establish a pattern of gratuities to public officials which, if given in quid pro quo exchange for official decisions, would constitute violations of federal law . . . .”[12]

Most NPAs and DPAs require a clear acknowledgement by the company that the statement of facts is “true and accurate,” and that the company bears responsibility for the actions of officers, directors, employees and agents acting on its behalf. For example, the Los Vegas Sands Corp. NPA, executed in January 2017, provided that “The Company admits, accepts, and acknowledges that it is responsible for the acts of its then-officers, directors, employees, and agents as set forth in the Statement of Facts and incorporated by reference into this Agreement, and that the facts described in the Statement of Facts are true and accurate.”[13]

Second, given the nature of the allegations at issue, rather than including lengthy provisions relating to NTC’s corporate compliance program—a common feature of NPAs and DPAs—the NTC NPA attached a detailed “Enhanced Security Plan for U.S.-Based Customers’ Domestic Communications Infrastructure” that set forth requirements for the following: (1) the designation of a Security Director; (2) the development of a Security Policy implementing certain minimum conditions; (3) implementation of specific code security, data transfer, and U.S.-based infrastructure security requirements; and (4) retention of a third-party auditor to monitor compliance with the plan.[14] In exchange for NTC’s “voluntary” agreement to abide by the plan, which the National Security Division called “a model for the kind of security that U.S. critical infrastructure should expect from the firms they use to develop, install, and maintain technology in their networks,”[15] DOJ agreed not to prosecute NTC or any of its present or former employees or officers relating to any allegation investigated by DOJ in connection with the allegations.[16] This provision is unusual, as NPAs and DPAs often expressly state that they do not immunize individual employees or officers against future prosecution. The Telia Company AB DPA, for example, executed in September 2017, stated “this Agreement does not provide any protection against prosecution of any individuals, regardless of their affiliation with the Company.”[17] The NTC NPA provision also goes beyond typical NPA language, which usually focuses on the instant resolution, in that it explicitly claims to “advance[] industry best practices” and offers broad guidance to other organizations about securing their technological infrastructure.[18]

Third, DOJ agreed not to impose any penalties upon NTC, unless NTC did not comply with the terms of the plan or the NPA, in which case NTC would be assessed liquidated damages totaling $35 million.[19] Zero penalties and liquidated damages provisions also are highly unusual; most NPAs and DPAs impose criminal penalties, and do not condition the payment of penalties on potential breach of the agreement. The Aegerion Pharmaceuticals Inc. DPA, also signed this year, similarly included a term providing for a “monetary payment of up to $15,000 per day for each day Aegerion is in breach” of the DPA, as an “alternative to instituting a prosecution . . . .”[20]

Fourth, contrary to DOJ’s standard practice of reserving exclusive authority to find a material breach, the NTC NPA also built in a third-party arbitration provision, providing a check on any finding of material breach by DOJ.[21] Although the NPA included a standard provision that DOJ would “determine, in [its] sole discretion, whether NTC has materially breached [the NPA],” it also provided for a third-party arbiter to decide whether DOJ had proven by a preponderance of the evidence that (1) its finding of breach was supported by the evidence, and (2) the breach was material, before liquidated damages could be assessed.[22] In contrast, a typical breach provision includes only the reservation of sole discretion quoted above, without any arbitration option.[23] This provision is particularly interesting in light of the ongoing debate about the government’s use of NPAs and DPAs and whether they represent an unlawful expansion of prosecutorial power. One element of U.S.-style NPAs and DPAs that detractors sometimes point to is the authority reserved by prosecutors to find breach.[24] The United Kingdom, for example, resolved this question in connection with its own DPA program by requiring the judiciary to determine whether a company has breached its agreement.[25] The middle road taken by the NTC agreement, between exclusive DOJ authority and judicial oversight, may reflect an effort to address this concern.

As we have indicated in earlier alerts, we believe that current NPA and DPA practices in the United States strike the appropriate balance between DOJ and judicial authority. In particular, they provide prosecutors with necessary discretion to consider mitigating factors when fashioning a resolution to achieve a more just and tailored result. More specifically, NPAs and DPAs allow companies to acknowledge employee wrongdoing and missteps, and prosecutors to create a remedy precisely tailored to the particular circumstances of a given case, without the disproportionate consequences that can accompany a guilty plea, like debarment, devastating reputational damage, and untrammeled collateral application in other litigation.[26] NPAs and DPAs allow DOJ to target specific conduct without undue negative impacts to otherwise upstanding corporate citizens and their employees, shareholders, and communities. Furthermore, such discretion allows prosecutors to consider factors that the Sentencing Guidelines do not necessarily consider but that are nonetheless relevant, like fines paid by a company to a foreign jurisdiction in a parallel enforcement proceeding. It is worth noting that prosecutorial discretion plays a critical role in DOJ’s decisions to address potential wrongdoing even outside of the NPA/DPA context, as prosecutors must decide whether to prosecute a company at all. Finally, while NPAs and DPAs offer additional flexibility that is not generally available in a traditional prosecution, this does not mean they are necessarily lenient. Indeed, NPAs and DPAs often impose substantial fines that materially impact a company’s bottom line, while also frequently imposing tough terms spanning multiple years that require ongoing reporting and widespread corporate reform.

Legislative and DOJ Enforcement Developments Impacting NPAs and DPAs

As noted above, although U.S. authorities continue to bring enforcement actions against corporations with the same vigor as before, prosecutors have only expanded the available options for corporate resolutions, and have particularly emphasized the value of declinations in cases where companies meet prescribed disclosure, cooperation, and remediation criteria. Most notably, in November 2017, Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein announced a new policy creating a presumption that companies will receive a declination for FCPA misconduct if they satisfy certain standards, including self-disclosure, full cooperation, and timely remediation.[27] A detailed synopsis and analysis of the new policy can be found in our Year-End 2017 FCPA Update.

Although the policy builds upon the Pilot Program’s contours, the new policy significantly enhances the status of declinations. The Pilot Program merely committed to considering a declination for companies that disclosed FCPA offenses, whereas the new policy introduces a “presumption” of declination that is rebutted only by “aggravating circumstances.”[28] Announcing the new policy on November 29, 2017, Rosenstein touted the Pilot Program’s success, noting that seven matters had resulted in declinations as a result of self-disclosures since the Pilot Program commenced.[29] Four of these seven declinations featured additional terms, including disgorgement, not typically seen in traditional Fraud Section declination letters.[30] The new “declination with disgorgement” letters (also termed “letter agreements”) blur the line between traditional declinations and NPAs by, among other things, requiring payment; imposing continuing cooperation and compliance requirements; and reserving DOJ’s right to reopen investigations if the recipient companies fail to comply with the declination terms. If successful, the new policy should further incentivize companies to cooperate with DOJ and potentially increase the number of FCPA matters that result in declinations rather than NPAs or DPAs.

Another factor that may impact the use of NPAs and DPAs is H.R. 732, entitled “Stop Settlement Slush Funds Act,” which was passed by the U.S. House of Representatives on October 24, 2017.[31] Congress rarely engages directly with NPAs and DPAs, instead leaving their use and interpretation to the executive and the judicial branches of government. However, this bill, if passed by the full U.S. Congress and signed by the President, would operate to prohibit government officials from entering into or enforcing settlement agreements—expressly including NPAs and DPAs—providing for “payment[s] or loan[s] to any person or entity other than the United States.”[32] The primary purpose of this bill appears to be to prevent mandatory donation provisions that (1) reinstate funding that Congress has already explicitly cut, (2) usurp Congress’s authority to decide funding priorities, and (3) circumvent grant oversight.[33] The bill as currently drafted also could also jeopardize the use of offsets and credits, which are an important and growing feature of NPAs and DPAs, particularly in an enforcement landscape in which global coordinated resolutions are becoming more common.

Through offsets, corporations may receive credit for parallel resolutions with foreign regulators related to the same underlying conduct. For example, the DPA that DOJ reached in 2017 with Telia Company AB required the company to pay $548.6 million in criminal penalties to the U.S. Treasury, of which $274 million could be offset by any criminal penalties paid to enforcement authorities in the Netherlands in connection with a parallel enforcement action by the Netherlands against several Telia Company AB subsidiaries.[34] This type of provision could be considered a form of “payment or loan to [a] person or entity other than the United States” in violation of the statute because, absent the monetary credit given to the defendant, the full resolution proceeds would presumably have gone to the U.S. Treasury. Notably, as the legislation is currently drafted, the government may argue that these offsets are permissible under an exception allowing payments to foreign entities that provide “restitution for or otherwise directly remed[y] actual harm” caused by the party making the payment.[35] If used, however, this exception would require the federal agency entering into the resolution to report annually for seven years to the Congressional Budget Office about the parties, funding sources, and distribution of funds for the related agreements.[36]

The legislative history of H.R. 732 does not indicate that the House has directly engaged with the question of how this legislation might impact foreign resolution offsets, but it does reflect DOJ’s “strenuous opposition” to a “substantively identical version” of the bill in 2016, on the basis that the bill would “unwisely constrain the government’s settlement authority and preclude many permissible settlements that would advance the public interest” and interfere with DOJ’s ability to address, remedy, and deter systemic harm caused by unlawful conduct.[37] We agree. Any impairment of DOJ’s ability to fashion fair and measured penalties for alleged misconduct, including the ability to account for payments to foreign governments for the same conduct, would run contrary to global law enforcement cooperation.

Updates in Corporate Monitorship Report Disclosures

Over the past three years we have followed developments in the court battle over disclosure of the HSBC independent monitor report. In our 2015 Mid-Year Update, we reported that Judge John Gleeson of the Eastern District of New York issued an order on April 28, 2015, instructing the government to file with the court the complete “First Annual Follow-Up Review” drafted by HSBC’s appointed compliance monitor;[38] the government filed the report under seal on June 1, 2015.[39] As discussed in our 2016 Mid-Year Update and 2016 Year-End Update, a private citizen requested access to the report after initiating a dispute with HSBC, and on January 28, 2016, Judge Gleeson decided that the report was a “judicial record” to which the public maintained a qualified First Amendment right of access.[40] After receiving proposed redactions from the government and HSBC, Judge Gleeson issued a ruling on March 9, 2016, ordering redactions of portions of the report in preparation for public disclosure, but further ordering that it remain under seal pending appellate review.[41] Both the government and HSBC appealed the order.

On July 12, 2017, the Second Circuit blocked the release of the monitor report. The court concluded that the monitor report was not a “judicial document” because it was “not now relevant to the performance of a judicial function.”[42] As a result, the court held that the district court abused its discretion in ordering that the report be unsealed.[43] The Second Circuit addressed the four grounds on which the intervening appellee and his amici argued that the report was relevant to the performance of a judicial function.

First, the court rebuffed the contention that the report was relevant to the district court’s supervisory authority to oversee the DPA. The court opined that by invoking its supervisory power sua sponte in this context, the district court ran afoul of the separation of powers.[44] In particular, the district court ignored the presumption of regularity, a doctrine that requires courts to give deference to prosecutors in the absence of clear evidence to the contrary.[45] The Second Circuit stated that, absent extraordinary circumstances, a district court’s role regarding DPAs is “limited to arraigning the defendant, granting a speedy trial waiver . . . and adjudicating motions or disputes as they arise.”[46]

Second, the court rejected the contention that the report was relevant to the district court’s authority to approve the DPA under the Speedy Trial Act. The Second Circuit agreed with the D.C. Circuit, which had previously held that the Speedy Trial Act did not grant the judiciary the power to second-guess DOJ’s exercise of discretion in making charging decisions.[47] The Second Circuit reasoned that if Congress wanted to reallocate historical powers among the branches of government, it would have done so clearly; as a result, the court declined to interpret vague language in the Speedy Trial Act to endow the courts with broad oversight power related to DPAs.[48]

The court addressed the third and fourth contentions together, rejecting the notion that the report was relevant to either the assessment of a Rule 48(a) motion to dismiss at the conclusion of the DPA’s term, or the adjudication of proceedings regarding any alleged breach of the DPA. The court emphasized that the report’s potential future relevance was insufficient to render it a judicial document at present.[49] The court also reiterated that the district court originally erred when it ordered the government to file the report because the court held no authority over the implementation of the DPA.[50]

As an advocate supporting NPAs and DPAs, we believe that the Second Circuit’s decision vested appropriate authority in the Justice Department.

Recently, on December, 12, 2017, DOJ filed a motion to dismiss the criminal information against HSBC that led to the DPA at issue.[51] DOJ concluded that HSBC had complied with its obligations under the DPA, and therefore opted to forgo a criminal prosecution against the bank.[52]

DPAs Go Global

Updates from the United Kingdom

As detailed in our Mid-Year Update, this year the Serious Fraud Office (“SFO”) reached DPAs with two companies, Rolls-Royce and Tesco Stores Limited, bringing the total number of DPAs under the United Kingdom’s DPA program to four.[53] To resolve allegations including conspiracy to corrupt, false accounting, and failure to prevent bribery, Rolls-Royce agreed to disgorge alleged profits of £258,170,000, pay a financial penalty of £239,082,645, and reimburse the SFO for £12,960,754 in costs incurred during the agency’s investigation, which was its largest-ever investigation to date (for a total SFO fine exceeding $615 million). Notably, in what some commentators have considered to be a departure from the SFO’s prior practice, Rolls-Royce was afforded an opportunity to resolve the investigation through a DPA even though a whistleblower’s anonymous blog post, rather than the company’s self-reporting, initially alerted the SFO to certain elements of the relevant conduct.[54] Earlier in the year, the SFO announced a DPA with Tesco Stores Limited to resolve allegations that Tesco had overstated its profits in 2013 and 2014 by £284 million (more than $350 million). The SFO has announced that Tesco has agreed to pay £129 million (approximately $160 million) in penalties, but little additional information about the resolution is available at this time. The full statement of facts and the Crown Court’s fairness determination will be made available to the public only at the conclusion of trials against three former Tesco executives.[55]

Also during 2017, Parliament adopted legislation expanding the category of cases that might be resolved through DPAs to include a number of financial offenses. Under the Policing and Crime Act 2017, violations of various financial-sanctions regimes may now be resolved by a DPA.[56] Likewise, the Criminal Finances Act 2017 creates two new corporate criminal offenses that also may be resolved through DPAs.[57] Those offenses, which have structures akin to the Bribery Act 2010 offense for failure to prevent bribery, create criminal liability for companies and partnerships that fail to prevent a person who performs services on its behalf from committing a U.K. or foreign tax evasion facilitation offense.[58] One available defense is to prove that, when the offense was committed, the corporation “had in place such reasonable prevention procedures as it was reasonable in all the circumstances to expect [it] to have in place.”[59] While providing guidance related to the new offenses, HM Revenue and Customs opined that the resolution of these offenses by DPA would “enable a corporate body to make full reparation for criminal behavior without the collateral damage of a conviction,” in addition to helping the corporation “avoid lengthy and costly trials.”[60]

Against the backdrop of this legislative expansion, and the increasing use of DPAs by the SFO, two prominent SFO officials recently addressed the status of the DPA program and the expectations on participating companies at the Cambridge Symposium on Economic Crime. Alun Milford, General Counsel of the SFO, highlighted lessons that he believes can be derived from the SFO’s four negotiated DPAs. First, the SFO General Counsel emphasized that judicial approval of DPAs—aimed at determining whether the proposed agreement is in the interest of justice and that its terms are fair, reasonable, and proportionate—is “no rubber stamp exercise.”[61] Instead, experience shows that the court “scrutinizes every aspect of the application for approval.” Second, citing the example of Rolls-Royce, which involved criminal conduct in numerous jurisdictions and spanning a number of decades, Milford explained that “cases in which criminality was of the most serious kind remain in principle eligible for a disposal by way of DPA.”

However, the speech focused on the SFO’s expectations for companies seeking DPAs. The SFO has been clear “[f]rom the Director down” that “only co-operative companies will ever be offered the opportunity of entering into a DPA with us.” The SFO General Counsel rejected the idea that Rolls-Royce had not been fully cooperative because the investigation did not begin with the company’s lawyers “picking the phone and arranging an appointment to tell us about a problem it had discovered of which we were entirely unaware.” It is true that “the absence of a self-report meant that [Rolls-Royce] started at a disadvantage” when seeking a DPA. Indeed, in considering the proposed Rolls-Royce DPA, the reviewing court “made clear that the fact that an investigation had not been triggered by a self-report would usually be highly relevant in the determination of the interests of justice test.” But “for a number of years thereafter,” Rolls-Royce “had provided [the SFO] with a consistently high-degree of cooperation, involving bringing to [its] attention wrong-doing [the SFO] had hitherto been unaware of.” Because “what was reported was far more extensive and of a different order to what may have been exposed” without Rolls-Royce’s cooperation, the SFO deemed the company worthy of a DPA offer. According to the SFO General Counsel, the Rolls-Royce matter thus conveys an important lesson for lawyers: “Lawyers advising corporates should not expect to go down the DPA route if, by the time we come knocking, we already have a good idea of what happened.”

Separately, SFO Director David Green has stated that DPAs provide companies with the opportunity to “draw a line under the past and radically to overhaul compliance and remov[e] the board on whose watch the conduct took place.”[62] Because radical personnel changes may be a necessary component of a DPA, “[i]t should never be thought that a DPA with a company somehow lets culpable former senior management off the hook: far from it.” Once a DPA is completed, moreover, the SFO can “concentrate resource[s] on human suspects and on new investigations,” as it has done in the case of Tesco, where the SFO is currently pursuing the criminal convictions of three former executives.

Taken together, these developments constitute an expansion of the DPA program in the United Kingdom and, consequently, suggest that DPAs will remain a central part of U.K. corporate criminal enforcement in the years to come. Through legislation, Parliament has expanded the range of offenses that are eligible for resolution through DPAs, including the newly created offenses for failure to prevent the facilitation of tax evasion. These changes could produce an increase in the number of agreements. According to Solicitor General Robert Buckland, the “threat of conviction is greater” under these failure-to-prevent offenses and, “as a result, companies might be more likely to . . . enter into DPAs.”[63] The SFO’s handling of the Rolls-Royce matter further suggests that DPAs may be available even in cases involving extensive criminal conduct and where an element of misconduct is independently discovered by the SFO.

France Issues Inaugural DPA-Style Agreement

Background on the Introduction and Availability of DPAs in France

On November 14, 2017, the National Financial Prosecutor of France announced a Convention judiciaire d’intérêt public (a public interest judicial agreement, hereinafter “CJIP”) entered into with HSBC Private Bank Suisse SA (“PBRS”). This marks the first application of a corporate settlement provision in France’s Law on Transparency, Fight against Corruption and Modernization of Economic Life (Loi relatif à la transparence, à la lutte contre la corruption et à la modernisation de la vie économique, referred to as “Sapin II,” after Finance Minister Michel Sapin, who presented the legislation).[64]

We previously covered the development of this long-anticipated legislation in our 2016 Mid-Year Update and 2016 Year-End Update. Sapin II emerged as a response to reports by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development highlighting the need for an improved anti-corruption regime in France. Increased imposition of fines on French companies by DOJ and other foreign enforcement authorities further prompted France to develop its own legislation to “bring France in line with the highest international standards in the area of transparency and the fight against corruption.”[65]

On December 9, 2016, French President François Hollande signed Sapin II into law following a series of heated debates and a lengthy reconciliation process in both of France’s legislative chambers.[66] One key provision of Sapin II allows the Public Prosecutor (procureur de la République) to offer a CJIP to a legal entity accused of corruption, trading in influence, or laundering tax proceeds.[67] The CJIP process is available only to legal entities; involved individuals are not parties to the CJIP and remain subject to prosecution even if a CJIP is reached. A legal entity may enter into a CJIP only if (1) the investigating magistrate identifies and specifies a sufficient factual basis for imposing liability; (2) the corporation recognizes responsibility for its acts; and (3) the prosecutor agrees that a CJIP is appropriate.[68]

A CJIP may require that the defendant pay fines up to 30% of its annual turnover over the past three years and to pay additional damages to victims.[69] The CJIP process may also impose provisions requiring companies to engage in remedial measures under the supervision of a monitor who reports to the French anti-corruption authority (Agence française anticorruption), an agency created under Sapin II. Once an agreement is reached between a prosecutor and a company, it must be submitted for judicial approval. Companies have the option to withdraw from a CJIP within 10 days after judicial approval; after the expiration of the opt-out period, the CJIP decision is shared with the public.[70] If a corporation complies with the provisions in its CJIP for a period of three years, a definitive order is entered precluding further prosecution under the same facts. This occurs without the corporation ever having a conviction on its record.

HSBC Private Bank (Suisse) SA Matter

On November 14, 2017, the National Financial Prosecutor of France announced the first negotiated resolution under Sapin II.[71] The agreement with PBRS, the Swiss subsidiary of HSBC, did not include any finding of guilt or require any ongoing compliance measures.[72] The CJIP alleged that numerous clients of PBRS had, to avoid taxes, failed to adequately disclose to the French government the full extent of assets they owned through PBRS-held accounts and used Swiss industry-standard client services provided by PBRS to do so.[73] Ultimately PBRS agreed to pay €300 million to settle tax evasion and money laundering charges arising from its alleged failure to prevent clients from using PBRS services for improper purposes.

Mechanics

First, the operation of a CJIP is different than that of a U.S.-style DPA. In the case of a DPA in the United States, upon reaching resolution, prosecutors will file a criminal information against the defendant(s), which will then be docketed. DPAs typically impose continuing obligations upon their recipients, including reporting and monitoring requirements. If the terms of the DPA are violated or if the defendants fail to comply with the ongoing obligations set forth in the agreement, the matter is then returned to the court and the proceedings begin where they left off, with the charging document already filed. The PBRS CJIP, however, is a comprehensive settlement agreement, which does not impose any continuing obligations on PBRS (after the payment of the fine), and brings final resolution to the investigative proceedings against the bank. The agreement does not have a defined term, and there are no terms and conditions defining misconduct or breaches of contract terms that could result in prosecution.

Overall Structure

The PBRS CJIP itself is only 10 pages, with no attachments or other appendices. It contains a brief statement of facts that, as explained below, differs from its counterpart in a U.S. DPA, in which a lengthy factual statement is typically separately attached to the agreement.

The CJIP contains a determination of the “public interest fine.” Not unlike a U.S. DPA, in which the calculation under the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines is set forth, the PBRS CJIP also contains the relevant calculations and offers additional context for the final amount. Sapin II puts a cap on the total fine to be assessed at 30% of average yearly revenue for the past three years, which was applied to PBRS, yielding a total fine of €157,975,422.[74] In reaching this conclusion, prosecutors required PBRS to disgorge €86,400,000 in profits associated with the accounts during the relevant time period.[75] The CJIP justifies the remaining penalty with reference to the “particular seriousness of the facts ascribed to PBRS, as well as their continuing nature.”[76] Although the agreement criticizes PBRS’s supposed “minimal cooperation” and says that PBRS neither self-disclosed nor acknowledged criminal liability related to the facts, it also acknowledges that “when the investigation started and until December 2016, the French legal system did not provide for a legal mechanism encouraging full cooperation.”[77] Pursuant to Sapin II, the CJIP also cited a €142,000,000 loss to the French tax authorities.

Finally, PBRS had 15 days from receipt of the proposed agreement to notify the National Financial Prosecutors of its acceptance. This is, of course, in contrast to a U.S. DPA, which the parties agree to before it is officially filed and docketed with the court.

Presentation of Facts

Like U.S. DPAs, the PBRS CJIP contains a statement of facts. The CJIP presents considerably less factual detail than a typical U.S. DPA. The average “Attachment A” to a U.S. DPA describing the underlying facts provides multiple pages of detail, often citing specific incriminating documents uncovered during the course of the investigation or particular transactions at issue. By contrast, the HSBC CJIP contains only general descriptions of the offenses at issue, namely that:

Based on the analysis performed by the investigators, the prosecution considers that the list of bank accounts found in the IT files seized at the domicile of PBRS’s former employee included more than 8,900 names of French tax payers. During the 2006 to 2007 period alone, the amount of assets held by French tax payers with PBRS’s operations in Geneva, Lugano and Zürich, has been valued to be at least €1,638,723,980.

Although it cannot be ruled out that a small proportion of these assets were held in accounts which had been declared to the French tax authorities prior to the opening of this investigation, it has been found that most of the concerned French clients did not declare their accounts or the accounts of which they were the beneficial owners in the books of PBRS to the French tax authorities.[78]

In addition to this brief description of the underlying conduct, the short CJIP factual section also describes, not unlike a U.S. DPA, the underlying controls implemented at the time within PBRS, as well as certain areas requiring improvement as previously acknowledged by HSBC during the investigation.[79]

Continuing Obligations of the Corporate Defendant

As noted above, U.S. DPAs, particularly those addressing FCPA violations, will typically have a series of continuing obligations with which defendants must comply for the duration of the agreement, including disclosing “credible evidence or allegations of a violation of U.S. federal law”[80] and fully cooperating “in any and all matters related to the conduct described in this Agreement and the Statements of Facts and other conduct related to possible corrupt payments under investigation by the United States.”[81] In addition, as part of several U.S. DPAs, prosecutors require the appointment of an independent compliance monitor, who is tasked with reviewing and monitoring an entity’s internal controls and compliance program elements as they relate to the particular violation in question, as well as any enhancements to those controls.[82] The PBRS CJIP has no such monitoring requirement. Despite the ability to require ongoing compliance and reporting obligations under Sapin II, the PBRS CJIP imposes none, perhaps in recognition of the bank’s prior efforts undertaken in this area.

Judicial Approval

In both the United States and France, DPAs and CJIPs must be submitted to a court. The appropriate level of judicial scrutiny of the U.S. DPA process is a topic fraught with disagreement, as discussed in our 2015 Year-End Update and herein above. Judges have taken different views regarding the appropriate scope of oversight, and there is no standard template for how judges should oversee DPAs. The CJIP process contemplates an involved role for the judiciary, requiring a holistic judicial review of all aspects of the agreement, including whether all proper procedures were followed and whether the fine was justified.[83] The CJIP between the French Prosecutor and PBRS was agreed to on October 9, and the Prosecutor requested approval by the Paris High Court (le tribunal de grand instance de Paris) on October 30. The Paris High Court announced its approval in a four-page decision on November 14, 2017, identifying the legal authority for the agreement and the factual underpinnings.[84] The court validated the agreement on the grounds that proper procedures were followed and the terms of the CJIP were justified in principle and in amount.

Collateral Consequences

Individuals cannot be parties to a CJIP and remain subject to prosecution even if a CJIP is reached with a company for the same underlying conduct.[85] Similarly, in the United Kingdom, DPAs cannot be used for resolutions with individuals.[86] In the United States, the genesis of DPAs arose from prosecuting minor offenses by first-time offender individuals. The focus on individual liability in the United States sharpened following a September 9, 2015 memorandum issued by then-Deputy Attorney General Sally Quillian Yates entitled “Individual Accountability for Corporate Wrongdoing” (the “Yates Memorandum”).[87] The parameters and implications of the Yates Memorandum are discussed in detail in our 2015 Year-End Update. Individual responsibility is not only allowed through the U.S. DPA process but is heavily emphasized in all corporate resolutions.

A common collateral consequence of DPAs is the increased exposure to subsequent civil litigation that is created by agreeing to a particular statement of facts. In the United States, defendants who agree to a DPA generally must acknowledge facts sufficient to support a conviction. Under Sapin II, if a company enters a CJIP at a preliminary investigation stage prior to initiation of public prosecution, there is no requirement for the company to acknowledge the facts or their legal significance. However, if a CJIP is entered pursuant to a formal investigation, the facts and their legal significance must be acknowledged by the company. Because the PBRS CJIP was reached after the initiation of a formal investigation, Sapin II required acknowledgement of the statement of facts presented in the CJIP. The extent to which this requirement will expose companies to further civil litigation remains to be seen.

Canada Considers a DPA Program

In September 2017, the Government of Canada released a public discussion paper regarding the possible adoption of a DPA regime in Canada as part of Canada’s efforts to assess whether it has the right tools in place to address corporate wrongdoing.[88] This discussion paper comes in the wake of an effort led by SNC-Lavalin, Canada’s largest engineering firm, which was charged in 2015 with fraud and corruption, to encourage Canada to adopt a DPA regime.[89] While the charges against SNC-Lavalin remain pending,[90] it has argued that adopting a DPA regime would ensure that Canadian businesses operate on the same playing field as counterparts in other countries that have DPA regimes, such as the United States and the United Kingdom.[91]

In the discussion paper, the Government of Canada invited Canadians to provide their views on ten key issues: (1) the usefulness of DPAs as part of the Canadian criminal justice system; (2) the scope of offenses for which DPAs should be available; (3) the role of the courts with respect to DPAs; (4) conditions for negotiating a DPA, such as what factors should be taken into account in offering a DPA and under what circumstances a DPA is not appropriate; (5) potential DPA terms and what factors should be considered in setting the duration of a DPA; (6) whether DPAs should be publicly published; (7) the process for addressing non-compliance; (8) under what circumstances facts disclosed during DPA negotiations should be admissible in a prosecution against the company should the DPA not ultimately be approved or in a prosecution for other offenses; (9) compliance monitoring, including how a compliance monitor is selected and governed, and how compliance monitoring reports should be used; and (10) under what circumstances victim compensation should be included as a DPA term.[92]

It also included an overview and comparison of the U.S. and U.K. DPA regimes, with in-depth analysis of some key considerations.[93] In its discussion of the U.S. and U.K. approaches to various DPA-related issues, the discussion paper generally did not adopt either approach on a given issue. Unlike the U.S. regime, however, the paper specified that Canada’s proposed regime would apply only to organizations, including “corporations, companies, firms, partnerships, and trade unions,” and would not apply to individuals.[94] This suggestion stems from the government’s “focus on corporate wrongdoing and the goal of prosecuting implicated individuals.”[95]

The government accepted submissions until December 8, 2017, and is currently in the process of reviewing feedback. It intends to publish a summary report of the comments received during the consultation process.

Public Comment – Transparency International Canada

In July 2017, prior to the government’s discussion paper, Transparency International Canada (“TI Canada”), an anti-corruption NGO, published a paper outlining DPAs and addressing many of the key issues.[96] Although on balance it encouraged the government to adopt a DPA regime, it cautioned against creating a system where DPAs are seen as a simple cost of doing business.[97] TI Canada recommended a DPA regime closer to the U.K. model, that is enacted through specific legislation and carried out under transparent judicial supervision.[98] Acknowledging Canada’s Integrity Regime, which separately provides for potential debarment from contracting of government suppliers that have “been charged with, or admit[ted] guilt of, any of the offences identified [in Canada’s Ineligibility and Suspension Policy] . . . “[99], TI Canada also added that DPAs should not ensure automatic protection against debarment, and that “such a protection should be the object of the prosecutor’s negotiation with the corporation in exchange for correspondingly significant guarantees of both reparations and sincere compliance reform.”[100]

Public Comment – The Canadian Bar Association

The Canadian Bar Association (“CBA”) published comments on each topic presented in the discussion paper.[101] In its submission, the CBA stated that DPAs should be available for economic crimes,[102] offenses that can result in debarment under the existing Integrity Regime,[103] and offenses under the Competition Act.[104] The CBA agreed with the Canadian government’s proposal to limit the availability of DPAs to “organizations,” such as corporations, and not to include individuals.[105]

In discussing the role of the courts with respect to DPAs, the CBA encouraged the Canadian government to consider, if court filings are required, a model where a DPA is filed with the court and open to public comment for the prosecutor’s consideration for a set period.[106] It also offered NPAs as an alternative to DPAs.[107]

The CBA suggested that the following factors be taken into consideration in determining whether a DPA is appropriate: (1) has the organization accepted responsibility for the conduct; (2) has the organization demonstrated that it genuinely seeks to reform its practices and corporate culture; (3) has the organization mitigated the damages caused by the conduct; (4) does the offending conduct represent the actions of individuals or is it sanctioned by company policy and practice and are any implicated individuals still with the organization; (5) is a criminal conviction likely to have disproportionate negative impacts on innocent people (e.g., shareholders, pension plan holders, employees, suppliers); and (6) is the organization a repeat offender.[108] The CBA further stated that DPAs should not be available when the conduct raises national security or foreign affairs issues or led to death or serious injury, or when the organization exists only for illegal conduct or has been previously warned or sanctioned.[109]

In its discussion of the appropriate terms to include in a DPA, the CBA suggested that Canada adopt a regime similar to the United Kingdom’s, where an express admission of guilt is not mandatory, but agreement on fundamental facts, compensation of victims, and a commitment to remediation is required.[110] The CBA explained that requiring an admission could easily be used by class action plaintiffs, which could lead to a chilling effect on DPAs.[111]

The CBA contended that there should be no publication of the DPA in the initial stages of negotiations, but that it would be appropriate for the government to announce when it has entered into a DPA and indicate the relevant conduct and key terms, without necessarily filing the entire DPA.[112] The CBA also stated that information gleaned in the course of a DPA negotiation should not be used in subsequent proceedings against the organization.[113] However, facts disclosed during DPA negotiations could be admissible in a prosecution against another company or rogue employee for other crimes.[114]

The CBA viewed the use of compliance monitors favorably but stated that they may not always be necessary.[115] The CBA suggested that if court oversight is ultimately required, then any compliance monitoring reports should not form part of the DPA, and should instead be used to inform the court of compliance and appropriateness of remedial measures.[116] The CBA set out the general principle that victim compensation should be included when applicable, but that it may be appropriate to limit victim compensation to persons who suffered direct harm.[117]

The Government of Canada has demonstrated its commitment to addressing corporate wrong-doing by publishing a discussion paper and soliciting public commentary on a proposed DPA regime. As noted above, it is now in the process of reviewing the submissions and is expected to publish a summary of the comments in the coming weeks.

APPENDIX: 2017 Non-Prosecution and Deferred Prosecution Agreements

The chart below summarizes the agreements concluded by DOJ in 2017. As noted above, the SEC did not enter into any NPAs or DPAs in 2017. The complete text of each publicly available agreement is hyperlinked in the chart.

The figures for “Penalty/Fine” may include amounts not strictly limited to an NPA or a DPA, such as fines, penalties, forfeitures, and restitution requirements imposed by other regulators and enforcement agencies, as well as amounts from related settlement agreements, all of which may be part of a global resolution in connection with the NPA or DPA, paid by the named entity and/or subsidiaries. The term “Monitoring & Reporting” includes traditional compliance monitors, self-reporting arrangements, and other monitorship arrangements found in settlement agreements.

U.S. Deferred and Non-Prosecution Agreements in 2017 |

||||||

| Company | Agency | Alleged Violation | Type | Penalty/Fine | Monitoring & Reporting | Term of DPA/NPA (months) |

| Aegerion Pharmaceuticals | D. Mass.; DOJ Consumer Protection | HIPAA; FCA; FDCA |

DPA |

$36,000,000 |

Yes | 36 |

| Banamex USA (Citigroup) | DOJ Money Laundering and Asset Recovery | Bank Secrecy Act |

NPA |

$237,440,000 |

Yes | 12 |

| Baxter Healthcare | W.D.N.C.; DOJ Consumer Protection | FDCA |

DPA |

$18,158,000 |

No | 30 |

| Breakthru Beverage Pennsylvania | M.D. Pa. | Bribery of a Public Official |

NPA |

$2,000,000 |

No | 12 |

| DAXC, LLC | S.D. Fla. | Theft of Government Property |

DPA |

$5,212,825 |

No | 12 |

| Dennis Corporation | N.D.W. Va | Conspiracy to impede the IRS |

DPA |

$250,000 |

No | 36 |

| Keppel Offshore & Marine LTD | DOJ Fraud; E.D.N.Y. | FCPA |

DPA |

$422,216,980 |

Yes | 36 |

| Las Vegas Sands Corp. | DOJ Fraud | FCPA |

NPA |

$15,960,000 |

Yes | 36 |

| Netcracker Technology Corporation | DOJ National Security Division; E.D.V.A. | ITAR; Export Administration Regulations |

NPA |

$0 (a) |

Yes | 36; 84 (b) |

| PDQ Imaging Services, LLC | E.D. Tex. | Illegal remunerations under federal health care program |

DPA |

$300,000 (c) |

Yes | 36 |

| Pharmaceutical Technologies, Inc. | E.D. Tex. | ERISA; Anti-Kickback Statute |

NPA |

$8,500,000 |

Unknown | Unknown |

| Pio Imports, LLC | M.D. Pa. | Bribery of a Public Official |

NPA |

$200,000 |

No | 12 |

| Prime Partners SA | DOJ Tax; S.D.N.Y. | Fraud (Tax); other tax-related offenses |

NPA |

$5,000,000 |

No | 36 (d) |

| RBS Securities Inc. | D. Conn. | Fraud (Securities) |

NPA |

$44,091,317 |

No | 12 |

| SBM Offshore N.V. | DOJ Fraud; S.D. Tex. | FCPA |

DPA |

$238,000,000 |

Yes | 36 |

| Sociedad Quimica y Minera de Chile, S.A. | DOJ Fraud | FCPA |

DPA |

$30,487,500 |

Yes | 36 |

| Southern Glazer’s Wine and Spirits of Pennsylvania, LLC | M.D. Pa. | Bribery of a Public Official |

NPA |

$5,000,000 |

No | 12 |

| State Street Corporation | D. Mass;

DOJ Fraud |

Fraud (wire fraud; securities fraud) |

DPA |

$64,600,000 |

Yes | 36 |

| Telia Company AB | DOJ Fraud; S.D.N.Y. | FCPA |

DPA |

$965,773,949 |

No | 36 |

| Utah Transit Authority | D. Utah | Misuse of public funds |

NPA |

$0 |

Yes | 36 (with possible indefinite extension) |

| Western Union Company, The | DOJ Criminal (Money Laundering and Asset Recovery Section); M.D. Pa.; C.D. Cal.; E.D. Pa.; S.D. Fla. |

AML, aiding and abetting wire fraud. |

DPA |

$586,000,000 |

Yes | 36 |

| White Rock Distilleries, Inc. | M.D. Pa. | Bribery of a Public Official |

NPA |

$2,000,000 |

No | 12 |

FCPA Pilot Program Declination Letters with Disgorgement in 2017 |

||||||

| CDM Smith Inc. | DOJ Fraud | FCPA |

Declination |

$4,037,138 |

Yes | N/A |

| Linde North America Inc. and Linde Gas North America LLC | DOJ Fraud | FCPA |

Declination |

$3,415,000 |

Yes | N/A |

| (a) Netcracker Technology Corp. received a penalty of $0, unless it is found to have materially breached the terms of the NPA, in which case it must pay $35 million in liquidated damages.

(b) Certain of Netcracker Technology Corp.’s NPA terms expire after three years, and others expire after seven years. (c) The NPA between PDQ Imaging Services, LLC and the United States Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of Texas provides that the $300,000 penalty shall be paid “in [a] civil case . . . in lieu of the monetary penalty. The parties agree that absent this provision the payment of the monetary penalty would substantially jeopardize the continued vitality of the Company.”[119] (d) The Prime Partners SA NPA stipulates a term of the greater of (1) three years, or (2) the date on which all prosecutions arising out of the conduct described in the agreement are final. |

||||||

[1] NPAs and DPAs are two kinds of voluntary, pre-trial agreements between a corporation and the government, most commonly DOJ. They are standard methods to resolve investigations into corporate criminal misconduct and are designed to avoid the severe consequences, both direct and collateral, that conviction would have on a company, its shareholders, and its employees. Though NPAs and DPAs differ procedurally—a DPA, unlike an NPA, is formally filed with a court along with charging documents—both usually require an admission of wrongdoing, payment of fines and penalties, cooperation with the government during the pendency of the agreement, and remedial efforts, such as enhancing a compliance program and—on occasion—cooperating with a monitor who reports to the government. Although NPAs and DPAs are used by multiple agencies, since Gibson Dunn began tracking corporate NPAs and DPAs in 2000, we have identified approximately 473 agreements initiated by the DOJ, and ten initiated by the SEC.

[2] We note that the statistics for 2016 have increased by four agreements since our 2016 Year-End Update, due to four DPAs that were publicly announced by the United States Attorney’s Office for the Central District of California in November 2017. See Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, “San Diego Nursing Homes Owned by L.A.-Based Brius Management to Pay up to $6.9 Million to Resolve Kickback and Fraud Allegations” (Nov. 16, 2017), https://www.justice.gov/usao-cdca/pr/san-diego-nursing-homes-owned-la-based-brius-management-pay-69-million-resolve-kickback.

[3] See U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Criminal Division, The Fraud Section’s Foreign Corrupt Practices Act Enforcement Plan and Guidance (Apr. 5, 2016), https://www.justice.gov/archives/opa/blog-entry/file/838386/download.

[4] U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Remarks of Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein, “Deputy Attorney General Rosenstein Delivers Remarks at the 34th International Conference on the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act” (Nov. 29, 2017), https://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/deputy-attorney-general-rosenstein-delivers-remarks-34th-international-conference-foreign.

[5] Id.

[6] In 2015, the Fraud Section also issued one NPA, but this was a relative historical low point for the Fraud Section, which issued two total NPAs and DPAs in 2015.

[7] Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, National Security Division Announces Agreement with Netcracker for Enhanced Security Protocols in Software Development (Dec. 11, 2017), https://www.justice.

gov/opa/pr/national-security-division-announces-agreement-netcracker-enhanced-security-protocols.

[8] Netcracker Website, About, https://www.netcracker.com/company/about-netcracker.html.

[9] Netcracker Technology Corporation, Non-Prosecution Agreement, Attachment A – Statement of Facts 1 (Dec. 6, 2017), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/national-security-division-announces-agreement-netcracker-enhanced-security-protocols.

[10] E.g., Non-Prosecution Agreement, Breakthru Beverage Pennsylvania, at 4 (July 19, 2017) (“[T]he Company and Breakthru Beverage Group den[y] criminal liability for the conduct”).

[11] Although the Pio Imports NPA included a statement that “certain supervisors” were engaging in such practices, it did not include a statement that those supervisors were otherwise aware that the company as a whole was engaging in the alleged practices. Non-Prosecution Agreement, Pio Imports, LLC, at 2 (July 20, 2017).

[12] E.g., Breakthru Beverage NPA, supra note 10, at 2-3. The language from the White Rock Distilleries NPA differed slightly from the others, reading, “While the Company does not admit that the conduct in the Statement of Facts violates federal or state criminal law, the Company recognizes and acknowledges that the facts described in the attached Statement of Facts establish a pattern of things of value to public officials which, had they been given in quid pro quo exchange for official decisions, would have constituted violations of federal law . . . .” Non-Prosecution Agreement, White Rock Distilleries, Inc., at 2-3 (June 28, 2017).

[13] Non-Prosecution Agreement, Las Vegas Sands Corp. at 2 (Jan. 17, 2017).

[14] Netcracker Technology Corporation, Non-Prosecution Agreement, Enhanced Security Plan for U.S.-Based Customers’ Domestic Communications Infrastructure, see https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/national-security-division-announces-agreement-netcracker-enhanced-security-protocols.

[15] Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, National Security Division Announces Agreement with Netcracker for Enhanced Security Protocols in Software Development (Dec. 11, 2017), https://www.justice.gov/

opa/pr/national-security-division-announces-agreement-netcracker-enhanced-security-protocols.

[16] Netcracker Technology Corporation, Non-Prosecution Agreement 2 (Dec. 6, 2017), https://www.justice.gov/

opa/pr/national-security-division-announces-agreement-netcracker-enhanced-security-protocols.

[17] Deferred Prosecution Agreement, United States v. Telia Co., 10 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 21, 2017) (No. 1:17-cr-00581-GBD).

[18] Netcracker Technology Corporation, supra note 16, at 2.

[19] Netcracker Technology Corporation, supra note 16, at 2, 6-8.

[20] Deferred Prosecution Agreement, United States v. Aegerion Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 10 (D. Mass. Sept. 22, 2017) (No. 1:17-cr-10288).

[21] Netcracker Technology Corp., supra note 16, at 6-8.

[22] Id.

[23] E.g., Telia DPA, supra note 17, at 5 (“Determination of whether the Company has breached the Agreement and whether to pursue prosecution of the Company shall be in the Fraud Section’s sole discretion.”); NPA, Southern Glazer’s Wine & Spirits of Penn., LLC, 3-4 (June 29, 2017) (reserving “sole discretion” in the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Middle District of Pennsylvania to determine whether breach has occurred).

[24] For example, as discussed in our 2013 Year-End Update, Schedule 17 of the U.K. Crime and Courts Act 2013, which authorizes the use of DPAs, expressly limits the role of prosecutorial discretion by granting judges, rather than prosecutors, the power to make breach determinations. See also, e.g., Jennifer Arlen, Negotiated Corporate Criminal Settlements: Bringing DPA Mandates Within the Rule of Law, Program on Corporate Compliance and Enforcement at N.Y.L. Sch. (Nov. 21, 2017), https://wp.nyu.edu/compliance_enforcement/2017/11/21/negotiated-corporate-criminal-settlements-bringing-dpa-mandates-within-the-rule-of-law/.

[25] See id.

[26] In a possible acknowledgement of this fact, for example, a 2017 DPA between the United States Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of Texas and PDQ Imaging Services, LLC, expressly required that a penalty imposed by the DPA be paid in connection with a separate civil action, rather than the criminal action connected to the DPA, because “absent this provision the payment of the monetary penalty would substantially jeopardize the continued viability of the Company.” Deferred Prosecution Agreement at 5, United States v. PDQ Imaging Servs., LLC (E.D. Tex. Nov. 22, 2017) (4:17-cr-00199-ALM-KPJ).

[27] Rod Rosenstein, Deputy Attorney General, DOJ, Remarks at the 34th International Conference on the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (Nov. 29, 2017), https://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/deputy-attorney-general-rosenstein-delivers-remarks-34th-international-conference-foreign.

[28] Id.

[29] Id.

[30] See our 2016 Year-End and 2017 Mid-Year Updates.

[31] Stop Settlement Slush Funds Act of 2017, H.R. 732, 115th Cong. (2017), https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/732/text. A substantively similar bill was introduced in the United States Senate, but has not yet been put to a vote. See Stop Settlement Slush Funds Act of 2017, S. 333, 115th Cong. (2017).

[32] Id.

[33] H.R. Rep. No. 115-72, Stop Settlement Slush Funds Act of 2017 (2017), https://www.congress.gov/

congressional-report/115th-congress/house-report/72.

[34] Telia DPA, supra note 17, at 8-9; Press Release, Openbaar Ministerie, “International Fight Against Corruption: Telia Company Pays 274.000.000 US Dollars to the Netherlands” (Sept. 21, 2017), https://www.om.nl/actueel/nieuwsberichten/

@100345/ international-fight/.

[35] Stop Settlement Slush Funds Act of 2017, H.R. 732, 115th Cong. (2017), https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/732/text.

[36] Id.

[37] Report 115-72, Stop Settlement Slush Funds Act of 2017, H.R. 732, 115th Cong. (2017), https://www.congress.gov/congressional-report/115th-congress/house-report/72 (citing comments from the U.S. Dep’t of Justice on H.R. 5063, the ”Stop Settlement Slush Funds Act of 2016,” to Members of the H. Comm. on the Judiciary 1, 3 (May 17, 2016) (on file with Democratic staff of the H. Comm. on the Judiciary)).

[38] Order, United States v. HSBC Bank USA, N.A., No. 12-cr-00763 (E.D.N.Y. Apr. 28, 2015).

[39] Monitor’s First Annual Follow-Up Report (Parts I and II), United States v. HSBC Bank USA, N.A., No. 12-cr-00763 (E.D.N.Y. June 1, 2015), ECF Nos. 36–37.

[40] Order, United States v. HSBC Bank USA, N.A., No. 12-cr-00763, slip op. at 1, 7 (E.D.N.Y. Jan. 28, 2016), ECF No. 52.

[41] Order, United States v. HSBC Bank USA, N.A., No. 12-cr-00763 (E.D.N.Y. Mar. 9, 2016), ECF No. 70.

[42] United States v. HSBC Bank USA, N.A., Nos. 16-308, 16-353, 16-1068, 16-1094, slip op. at 2 (2d Cir. July 12, 2017).

[43] Id. at 39.

[44] Id. at 6, 22.

[45] Id. at 25–26. The presumption of regularity obliges federal courts to defer to prosecutorial conduct and decision making. Id. at 25. The doctrine is rooted in the separation of powers and provides that “‘in the absence of clear evidence to the contrary, courts presume that [public officers] have properly discharged their official duties.'” United States v. Armstrong, 517 U.S. 456, 464 (1996) (quoting United States v. Chem. Found., Inc., 272 U.S. 1, 14–15 (1926)).

[46] United States v. HSBC Bank USA, N.A., Nos. 16-308, 16-353, 16-1068, 16-1094, slip op. at 6 (2d Cir. July 12, 2017).

[47] Id. at 29 (referencing United States v. Fokker Services B.V., 818 F.3d 733, 738 (D.C. Cir. 2016)).

[48] Id. at 30–31.

[49] Id. at 32, 39.

[50] Id. at 32 (“Critically, as we held above, the district court erred in ordering the government to file the Monitor’s Report pursuant to its authority over the implementation of the DPA for the simple reason that the district court had no such authority.”).

[51] Motion to Dismiss, United States v. HSBC Bank USA, N.A., No. 12-cr-00763 (E.D.N.Y. Dec. 12, 2017), ECF 96; see Evan Weinberger, DOJ Seeks Dismissal of HSBC Money Laundering Case, Law360 (Dec. 12, 2017, 1:35 PM), https://www.law360.com/whitecollar/articles/993914/doj-seeks-dismissal-of-hsbc-money-laundering-case.

[52] Motion to Dismiss, United States v. HSBC Bank USA, N.A., No. 12-cr-00763 (E.D.N.Y. Dec. 12, 2017), ECF 96.

[53] Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, 2017 Mid-Year Update on Corporate Non-Prosecution Agreements (NPAs) and Deferred Prosecution Agreements (DPAs), at 6, https://www.gibsondunn.com/publications/Pages/2017-Mid-Year-Update-Corporate-NPA-and-DPA.aspx.

[54] See id. at 6–8.

[55] See id. at 8–9.

[56] See Policing and Crime Act 2017, c. 3, § 150 (amending the Crime and Courts Act 2013).

[57] For additional information on the Criminal Finances Act 2017, please see our September 29, 2017 client alert devoted solely to that topic, https://www.gibsondunn.com/publications/Pages/Criminal-Finances-Act-2017-New-Corporate-Facilitation-of-Tax-Evasion-Offence-Act-Now.aspx.

[58] See Criminal Finances Act 2017, c. 22, § 45 (UK tax evasion); id. § 46 (foreign tax evasion).

[59] Id. § 45(2) (UK tax evasion); see also id. § 46(3) (foreign tax evasion).

[60] HM Revenue & Customs, Tackling tax evasion: Government guidance for the corporate offenses of failure to prevent the criminal facilitation of tax evasion, at 13–14 (Sept. 1, 2017), https://www.gov.uk/government/

uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/642714/Tackling-tax-evasion-corporate-offences.pdf.

[61] Serious Fraud Office, News Release, Alun Milford on Deferred Prosecution Agreements (Sept. 5, 2017), https://www.sfo.gov.uk/2017/09/05/alun-milford-on-deferred-prosecution-agreements/.

[62] Serious Fraud Office, News Release, Cambridge Symposium 2017 (Sept. 4, 2017), https://www.sfo.gov.uk/

2017/09/04/cambridge-symposium-2017/.

[63] Robert Buckland, Speech, Solicitor General’s speech at Cambridge Symposium on Economic Crime (Sept. 4, 2017), https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/solicitor-generals-speech-at-cambridge-symposium-on-economic-crime.

[64] See Law on Transparency, Fight against Corruption and Modernization of Economic Life, No. 2016-1691 of 9 December 2016, French Official Gazette, No. 0287 (Dec. 10, 2016) [hereinafter “Law on Transparency”], https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/eli/loi/2016/12/9/2016-1691/jo/texte.

[65] Sapin II Law: Transparency, the Fight Against Corruption, Modernisation of the Economy, Apr. 6, 2016, http://www.gouvernement.fr/en/sapin-ii-law-transparency-the-fight-against-corruption-modernisation-of-the-economy.

[66] One day prior, on December 8, 2016, the Constitutional Council ruled that the public interest judicial agreement (i.e., Article 22) was constitutional. See Constitutional Council, Decision No. 2016-741 (Dec. 8, 2016), http://www.senat.fr/dossier-legislatif/pjl15-691.html.

[67] Law on Transparency at Art. 22.

[68] Frederick T. Davis, A French Court Authorizes the First-Ever “French DPA,” Program on Corporate Compliance and Enforcement at N.Y.L. Sch., Nov. 24, 2017, https://wp.nyu.edu/compliance_enforcement/2017/11/24/a-french-court-authorizes-the-first-ever-french-dpa/.

[69] Id.

[70] Id.

[71] Convention judiciaire d’intérêt public between the National Finance Prosecutor and HSBC Private Bank (Suisse) SA, “PRBS,” (hereinafter, “PBRS CJIP”), Oct. 30, 2017.

[72] David Keohane & Martin Arnold, HSBC agrees to pay €300m to settle probe into tax evasion, F.T., Nov. 14, 2017.

[73] PBRS CJIP at ¶¶ 14-15.

[74] PBRS CJIP, at ¶¶ 37-38.

[75] Id. at 42.

[76] Id. at 43.

[77] Id.

[78] PBRS CJIP at ¶¶ 21-22.

[79] Id. at ¶33; see also HSBC Group, HSBC’s Swiss Private Bank – Progress Update, Jan. 2015, www.hsbc.com/~/media/hsbc-com/…/financial-and…/gbp-update%20-290115.

[80] Deferred Prosecution Agreement, United States v. Dallas Airmotive, Inc., Attachment D, at ¶ 6 (Dec. 10, 2014).

[81] SBM Offshore, N.V., DPA, at ¶ 5 (Nov. 29, 2017).

[82] See, e.g., Deferred Prosecution Agreement, United States v. State Street Corporation, Attachment C (Jan. 17, 2017).

[83] Ordonnance de Validation D’Une Convention Judiciaire D’intérêt Public, Cour D’Appel de Paris, Nov. 14, 2017.

[84] Id.

[85] Following the PBRS CJIP, two former directors of HSBC remain under investigation. Id. at 2, n. 7.

[86] Public Consultation Paper, Australia Attorney-General’s Department, Improving enforcement options for serious corporate crime: Consideration of a Deferred Prosecution Agreements scheme in Australia, at 13, Mar. 2016, https://www.ag.gov.au/Consultations/Documents/Deferred-prosecution-agreements/Deferred-Prosecution-Agreements-Discussion-Paper.pdf.

[87] U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Memorandum from Deputy Attorney Gen. Sally Quillian Yates Regarding Individual Accountability for Corporate Wrongdoing (2015), http://www.justice.gov/dag/file/769036/download.

[88] Gov’t of Canada, Expanding Canada’s Toolkit to Address Corporate Wrongdoing: Deferred Prosecution Agreement Stream, Discussion paper for public consultation (“Discussion Paper”) at 4, 82 https://www.tpsgc-pwgsc.gc.ca/ci-if/ar-cw/documents/volet-stream-eng.pdf; Online public consultation examines Government tools for fighting Corruption, Public Services and Procurement Canada, September 25, 2017, https://www.canada.ca/en/public-services-procurement/news/2017/09/government_of_canadaseeksviewson

addressingcorporatewrongdoing.html.

[89] SNC Lavalin Pushes for Deferred Prosecution Agreements in Canada, Corp. Crime Rep., January 31, 2017, https://www.corporatecrimereporter.com/news/200/snc-lavalin-pushes-for-deferred-prosecution-agreem

ents-in-canada/; see also Ross Marowits, Deferred Prosecution Agreements Under Review, Canadian Press (Sept. 25, 2017), http://www.msn.com/en-ca/news/other/deferred-prosecution-agreements-under-review/ar-AAsstD3.

[90] SNC’s fraud, corruption hearing set for 2018, The Globe and Mail, February 26, 2016, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/sncs-fraud-corruption-hearing-set-for-2018/article28929552/.

[91] Submission to the DPA/Integrity Regime Consultation DPA Submission, SNC Lavalin, October 13, 2017, http://www.snclavalin.com/en/files/documents/publications/dpa-consultation-submission-october-13-2017_en.pdf.

[92] Expanding Canada’s Toolkit, supra note 88.

[93] Id. at 5, 7, 10. For a comparison of the U.S. and U.K. DPA regimes, see the 2015 Year-End Update.

[94] Id. at 4, n. 1.

[95] Id. at 8, n. 2.

[96] Another Arrow in the Quiver? Consideration of a Deferred Prosecution Agreement Scheme in Canada, Transparency International Canada, (July 2017), http://www.transparencycanada.ca/wp-content/uploads/

2017/07/DPA-Report-Final.pdf.

[97] Id. at 3.

[98] Id. at 3, 23, 28.

[99] Gov’t of Canada, Ineligibility and Suspension Policy, Section 7(d), http://www.tpsgc-pwgsc.gc.ca/ci-if/politique-policy-eng.html.

[100] Id.

[101] Canadian Bar Ass’n, Addressing Corporate Wrongdoing in Canada (“CBA Comment”) (Dec. 2017), http://www.cba.org/CMSPages/GetFile.aspx?guid=d437189b-f458-456a-8feb-bc4abe56391a.

[102] According to the CBA, this includes “fraud, false accounting, corruption, foreign bribery and money laundering (or dealing with the proceeds of crime), exportation and or/importation of prohibited or restricted goods and related offences.” Id. at 2.

[103] Id. at 3.

[104] Id.

[105] Id.

[106] Id. at 4.

[107] Id.

[108] Id. at 5.

[109] Id. at 6.

[110] Id. at 6-7. The U.K.’s Deferred Prosecution Agreements Code of Practice requires a statement of facts that include particulars relating to each alleged offense. The Code of Practice also states, “There is no requirement for formal admissions of guilt in respect of the offences charged by the indictment though it will be necessary for [an organization] to admit the contents and meaning of key documents referred to in the statement of facts.” Serious Fraud Office, Deferred Prosecution Agreements Code of Practice, Crime and Courts Act of 2013, 11, https://www.sfo.gov.uk/?wpdmdl=1447 .

[111] Id.

[112] Id. at 8.

[113] Id. at 9.

[114] Id.

[115] Id. at 10.

[116] Id.

[117] Id.

[118] PDQ, supra note 26.

[119] PDQ, supra note 26.

The following Gibson Dunn lawyers assisted in preparing this client update: F. Joseph Warin, Michael Diamant, Patrick Doris, Sacha Harber-Kelly, Courtney Brown, Melissa Farrar, Mark Handley, Jason Smith, Jeffrey Bengel, William Hart, Lucie Duvall, Chelsea Ferguson, and Alison Friberg.

Gibson Dunn’s White Collar Defense and Investigations Practice Group successfully defends corporations and senior corporate executives in a wide range of federal and state investigations and prosecutions, and conducts sensitive internal investigations for leading companies and their boards of directors in almost every business sector. The Group has members in every domestic office of the Firm and draws on more than 125 attorneys with deep government experience, including more than 50 former federal and state prosecutors and officials, many of whom served at high levels within the Department of Justice and the Securities and Exchange Commission. Joe Warin, a former federal prosecutor, served as the U.S. counsel for the compliance monitor for Siemens and as the FCPA compliance monitor for Alliance One International. He previously served as the monitor for Statoil pursuant to a DOJ and SEC enforcement action. He co-authored the seminal law review article on NPAs and DPAs in 2007. Debra Wong Yang is the former United States Attorney for the Central District of California, and has served as independent monitor to a leading orthopedic implant manufacturer to oversee its compliance with a DPA. In the United Kingdom, Sacha Harber-Kelly is a former Prosecutor and Case Controller at the Serious Fraud Office.

Washington, D.C.

F. Joseph Warin (+1 202-887-3609, [email protected])

Richard W. Grime (202-955-8219, [email protected])

Scott D. Hammond (+1 202-887-3684, [email protected])

Stephanie L. Brooker (+1 202-887-3502, [email protected])

David P. Burns (+1 202-887-3786, [email protected])

David Debold (+1 202-955-8551, [email protected])

Stuart F. Delery (+1 202-887-3650, [email protected])

Michael Diamant (+1 202-887-3604, [email protected])

John W.F. Chesley (+1 202-887-3788, [email protected])

Daniel P. Chung (+1 202-887-3729, [email protected])

Caroline Krass (+1 202-887-3784, [email protected])

Patrick F. Stokes (+1 202-955-8504, [email protected])

New York

Reed Brodsky (+1 212-351-5334, [email protected])

Joel M. Cohen (+1 212-351-2664, [email protected])

Mylan L. Denerstein (+1 212-351-3850, [email protected])

Lee G. Dunst (+1 212-351-3824, [email protected])

Barry R. Goldsmith (+1 212-351-2440, [email protected])

Christopher M. Joralemon (+1 212-351-2668, [email protected])

Mark A. Kirsch (+1 212-351-2662, [email protected])

Randy M. Mastro (+1 212-351-3825, [email protected])

Marc K. Schonfeld (+1 212-351-2433, [email protected])

Orin Snyder (+1 212-351-2400, [email protected])

Alexander H. Southwell (+1 212-351-3981, [email protected])

Lawrence J. Zweifach (+1 212-351-2625, [email protected])

Denver

Robert C. Blume (+1 303-298-5758, [email protected])

Ryan T. Bergsieker (+1 303-298-5774, [email protected])

Los Angeles

Debra Wong Yang (+1 213-229-7472, [email protected])

Marcellus McRae (+1 213-229-7675, [email protected])

Michael M. Farhang (+1 213-229-7005, [email protected])

Douglas Fuchs (+1 213-229-7605, [email protected])

Eric D. Vandevelde (+1 213-229-7186, [email protected])

Palo Alto

Benjamin B. Wagner (+1 650-849-5395, [email protected])

San Francisco

Thad A. Davis (+1 415-393-8251, [email protected])

Marc J. Fagel (+1 415-393-8332, [email protected])

Charles J. Stevens (+1 415-393-8391, [email protected])

Michael Li-Ming Wong (+1 415-393-8234, [email protected])

Winston Y. Chan (+1 415-393-8362, [email protected])

London

Patrick Doris (+44 20 7071 4276, [email protected])

Sacha Harber-Kelly (+44 20 7071 4205, [email protected]) Mark Handley (+44 20 7071 4277, [email protected])

Munich

Benno Schwarz (+49 89 189 33-110, [email protected])

Mark Zimmer (+49 89 189 33-130, [email protected])

Dubai

Graham Lovett (+971 (0) 4 318 4620, [email protected])

Hong Kong

Kelly Austin (+852 2214 3788, [email protected])

Oliver D. Welch (+852 2214 3716, [email protected])

© 2018 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.