2020 Mid-Year Securities Litigation Update

Client Alert | August 10, 2020

The first half of 2020 brought the spread of COVID-19 and unprecedented changes in daily life and the economy. We discuss how, nevertheless, there has still been a variety of securities-related lawsuits, including securities class actions, insider trading lawsuits, and government enforcement actions. We also discuss developments in the securities laws that have occurred against this backdrop.

The mid-year update highlights what you most need to know in securities litigation developments and trends for the first half of 2020:

- In Liu v. SEC, the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed the SEC’s ability to obtain disgorgement as an equitable remedy in civil actions, but left open several questions about the permissible scope of the remedy. In addition, a petition for a writ of certiorari was filed in National Retirement Fund v. Metz Culinary Management, Inc., a case posing the question of how to calculate withdrawal liability based on interest rate assumptions for union pension plans.

- We discuss the Delaware Supreme Court’s decision in Salzberg v. Sciabacucchi, which confirmed the facial validity of federal-forum provisions, as well as the Court of Chancery’s treatment of Caremark claims and director independence with respect to a putatively controlling stockholder.

- We continue to analyze how lower courts are applying the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Lorenzo, with a focus on recent district court opinions interpreting Lorenzo’s scope.

- We survey securities-related lawsuits arising in connection with or related to the coronavirus pandemic, including securities class actions, insider trading lawsuits, and government enforcement actions filed by both the SEC and the Department of Justice.

- We discuss recent decisions illustrating the difficulty plaintiffs face in attempting to overcome Omnicare’s formidable barrier to adequately pleading securities fraud.

- We examine the Second Circuit’s noteworthy decision in Goldman Sachs II regarding how defendants may rebut the presumption of reliance under Halliburton II.

- Finally, we examine the intersection of the federal securities laws and ERISA, discussing the U.S. Supreme Court’s recent Sulyma decision, which clarified the statute of limitations for fiduciary breach claims, and the lower court decisions addressing significant issues in the wake of the Court’s January decision in Jander.

I. Filing And Settlement Trends

Despite COVID, data from a newly released NERA Economic Consulting (“NERA”) study shows that the first half of 2020 was not markedly different from 2019, and in some cases, continued trends that have been developing over the last few years. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this year, the number of new federal class action cases filed is on pace to be about 15–20% lower than 2017–2019, but is still on par with the amount of new federal class actions filed during those years as compared to the first half of the decade.

There has also been a continuation of the trends that have formed over the last few years for the types of cases filed. For example the number of merger cases in 2020 is on pace to generally continue the trend of post-2017 declines, and the number of Rule 10b-5-related cases is projected to continue the upward slope begun in 2016.

With regards to securities cases filed per industry sector, the Health Technology and Services sector is projected to have a decline for a fifth year in a row, while the Electronic Technology and Technology Services sector is projected to have additional growth.

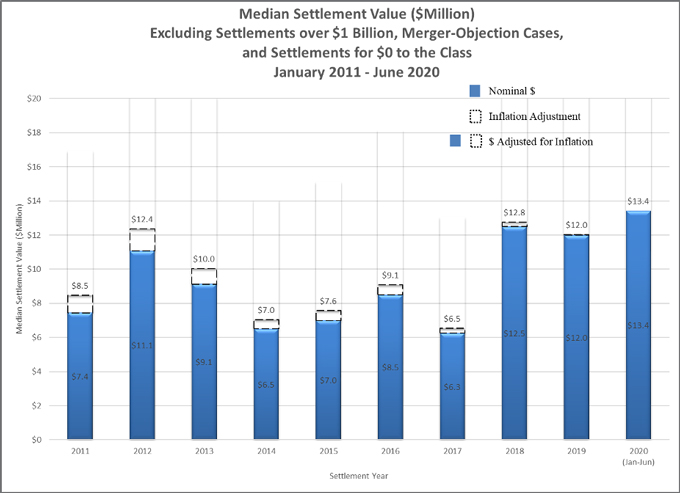

The median settlement values of federal securities cases for 2020—excluding merger-objection cases and cases settling for either more than $1 billion or equal to $0—is on pace to be the highest of the decade (and up about 10% compared to 2019). This continues the trend of the last few years, which has resulted in median settlements that average nearly twice the median settlement in 2017 ($6.5 million). In contrast to the median settlement, the average settlement, however, does not appear to be following a trend, as it is more than double the average settlement value in 2019, but about 10% less than the average settlement in 2018.

A. Filing Trends

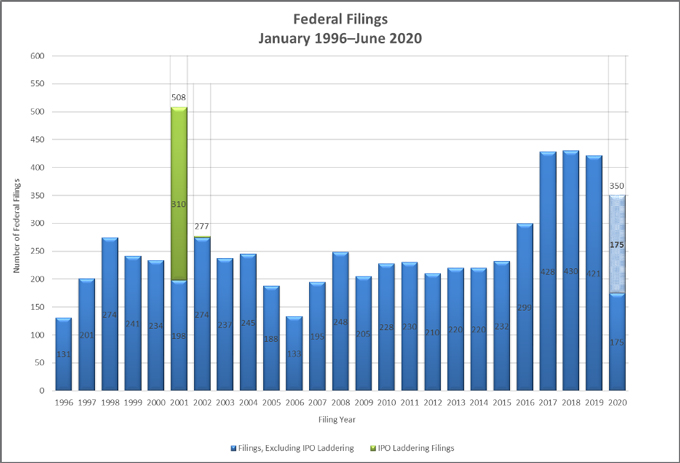

Figure 1 below reflects the number of federal filings for the first half of 2020.[1] The one hundred seventy-five cases filed as of June 30 put 2020 on pace to have 15-20% fewer filings than the years spanning 2017-2019, but still significantly more than during 1996–2016 (with the exception of 2001, which was dominated by IPO Laddering Filings).

Figure 1:

B. Mix Of Cases Filed In 1H 2020

1. Filings By Industry Sector

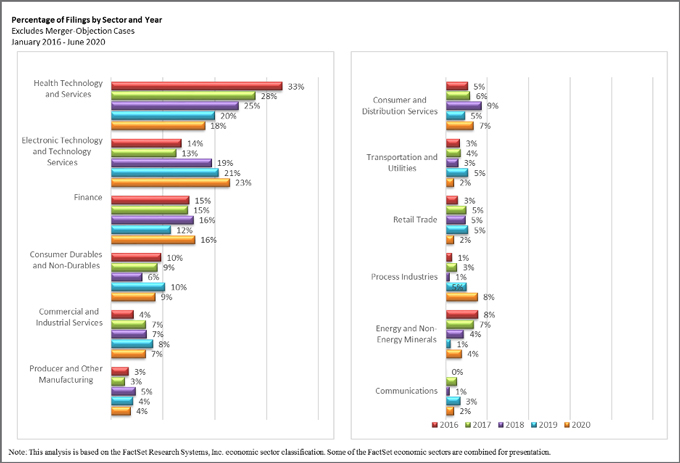

Figure 2 below sets forth the split of non-merger objection class actions filed in the first half of 2020. Notably, the percentage of class actions related to Health Technology and Services continue to decline as they have each year from 2016–2020, whereas class actions related to Electronic Technology and Technology Services continue to increase as they have each year during 2016–2020. Finance-based class actions bounced back to 2016–2018 levels, suggesting that 2019 was an anomaly.

Figure 2:

2. Merger Cases

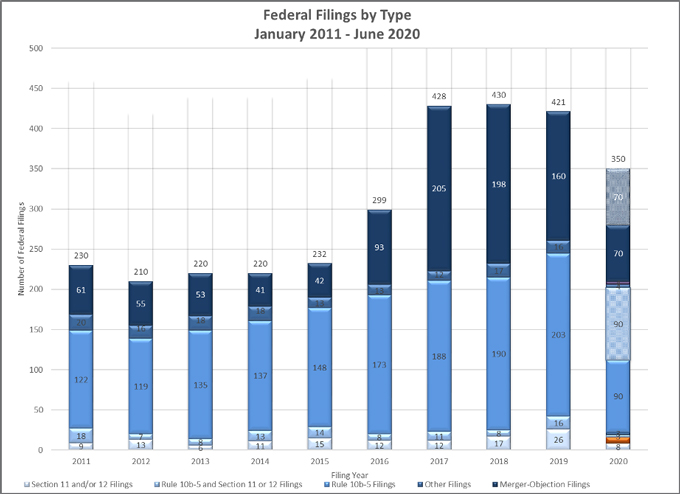

Figure 3 below breaks down the types of federal filings in the first half of 2020. Merger objection filings are projected to constitute 40% of federal filings in 2020, which is generally consistent with the trend of slight decreases that began following the massive jump in 2017 (48%), declining in 2018 (46%) and 2019 (38%). Rule 10b-5 filings are projected to represent 51% of federal filings in 2020, which represents a slight increase as compared to 2019 (48%), 2018 (44%), and 2017 (44%).

Figure 3:

C. Settlement Trends

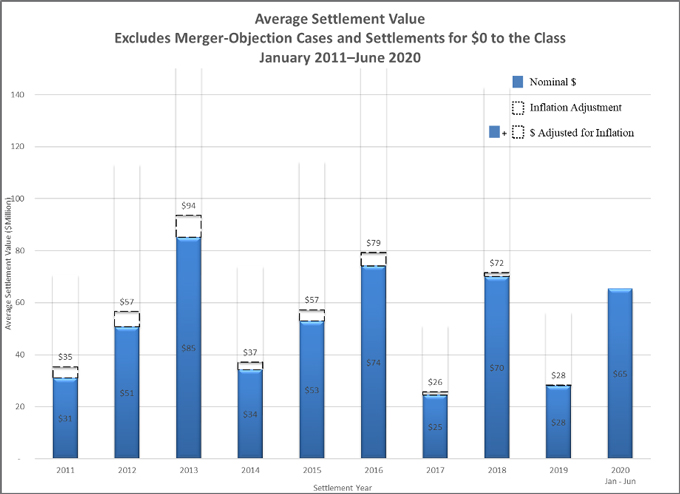

As Figure 4 shows below, the average settlement value in 2020 is more than double the average settlement value in 2019, and is in the upper half of average settlement values over the past decade. However, as the chart demonstrates, it is difficult to infer any particular trend in average settlement values over the past decade.

Figure 4:

In Figure 5 below, median settlement values show for 2020 are similar to 2018 and 2019, all three of which are among the highest of the decade. The differences between Figure 4, which shows a sharp contrast between 2020 and 2019, and Figure 5, which does not, is likely attributable to Figure 5’s exclusion of settlements over $1 billion.

Figure 5:

II. What To Watch For In The Supreme Court

In a blockbuster term affected by the pandemic, the U.S. Supreme Court issued 53 signed opinions—its lowest number in over 150 years. Only one of those cases arose under the federal securities laws.

A. The Supreme Court Allows Equitable Disgorgement In SEC Enforcement Actions

On June 22, 2020, the Supreme Court issued an opinion in Liu v. SEC, which affirmed the Securities and Exchange Commission’s (“SEC”) ability to obtain disgorgement as an equitable remedy in civil actions, but left open several questions about the permissible scope of the remedy. 140 S. Ct. 1936 (2020). As discussed in our 2019 Year-End Securities Litigation Update, in Liu, the SEC brought an action for securities fraud against Charles Liu and his wife Xin Wang, alleging they misappropriated over $20 million of EB-5 investor funds.

The district court granted summary judgment in favor of the SEC on its claim under Section 17(a)(2) of the Securities Act and ordered disgorgement of the total amount raised from investors. SEC v. Liu, 262 F. Supp. 3d 957, 976 (C.D. Cal. 2017). The Ninth Circuit affirmed, rejecting defendants’ argument that the district court lacked the authority to order disgorgement based on Kokesh v. SEC, 137 S. Ct. 1635, 1645 (2017). SEC v. Liu, 754 F. App’x 505, 509 (9th Cir. 2018). In their petition, defendants argued that the Court’s decision in Kokesh, which held that “SEC disgorgement constitutes a penalty within the meaning of § 2462,” 137 S. Ct. at 1643, foreclosed the court from considering disgorgement as an equitable remedy under 15 U.S.C. § 78u(d)(5). See Liu, 140 S. Ct. at 1946.

On June 22, 2020, in an 8-1 decision, the Supreme Court disagreed with defendants’ argument that disgorgement is categorically unavailable to the SEC, finding that “a disgorgement award that does not exceed a wrongdoer’s net profits and is awarded for victims is equitable relief permissible under § 78u(d)(5),” and remanded the case to the lower court to consider whether the order was appropriately tailored. Id. at 1940.

Even though the Court’s decision does not foreclose the SEC from obtaining disgorgement, it does cabin the remedy in several important ways. The Court noted that in recent years, grants of disgorgement have “test[ed] the bounds of equity practice: by ordering the proceeds of fraud to be deposited in Treasury funds instead of disbursing them to victims, imposing joint-and-several disgorgement liability, and declining to deduct even legitimate expenses from the receipts of fraud.” Id. at 1946. Although the Court declined to specify the precise boundaries of permissible disgorgement, it “nevertheless discuss[ed] principles that may guide the lower courts’ assessment of these arguments on remand.” Id. at 1947.

First, the Court noted that “[t]he equitable nature of the profits remedy generally requires the SEC to return a defendant’s gains to wronged investors for their benefit.” Id. at 1948. The broad public benefit of “depriving a wrongdoer of ill-gotten gains” alone is not generally sufficient to meet that requirement and “would render meaningless the latter part of §78u(d)(5),” which restricts equitable relief to that “appropriate or necessary for the benefit of investors.” Id. While the Court considered that practical concerns may justifiably limit the ability to remit funds to defrauded investors, it did not offer specific guidance on when it may be permissible to deposit disgorged funds into the Treasury, instead noting that “[i]t is an open question whether, and to what extent, that practice . . . is consistent with the limitations of §78u(d)(5).” Id.

Second, the Court discussed the application of joint-and-several liability, noting that the practice has occurred “in a manner sometimes seemingly at odds with the common-law rule requiring individual liability for wrongful profits.” Id. at 1949. Applying this liability to disgorgement remedies could improperly “transform any equitable profits-focused remedy into a penalty.” Id. Because Liu and Wang were married and commingled finances, the Court left it to the Ninth Circuit to determine whether joint-and-several liability would be appropriate in this case, as “partners engaged in concerted wrongdoing.” See id.

Third, the Court found that “courts must deduct legitimate expenses before ordering disgorgement,” but provided limited guidance on what would constitute such expenses. Id. at 1950. The Court postulated that defendants who operate an “entirely fraudulent scheme” might have illegitimate expenses, such as those for “personal services.” Id. On the other hand, expenses that “have value independent of fueling a fraudulent scheme” may be legitimate. Id. Again, the Court left it to the lower court to examine precisely which expenses may be included “consistent with the equitable principles underlying § 78u(d)(5).” Id.

Accordingly, the Liu decision leaves open significant questions concerning the practical application of any disgorgement remedy, including the contours of when (1) disgorged funds may be disbursed to the Treasury rather than recouped by investors; (2) joint and several liability may be imposed; and (3) business expenses should be deemed legitimate and deducted from a disgorgement award.

In the coming years, lower courts will have to grapple with these complicated considerations in deciding how to apply the Court’s guidance in particular cases.

B. Pension Plan Seeks Review Of Withdrawal Liability Calculation Decision

On May 29, 2020, a petition for a writ of certiorari was filed in National Retirement Fund v. Metz Culinary Management, Inc., No. 19-1336, a case involving the question of how to calculate withdrawal liability based on interest rate assumptions for union pension plans. Petitioners, a multiemployer trust fund and its trustees, which manage the pension plans of approximately 10 million participants, asked the Court to reverse the Second Circuit’s decision that favored employers. Petition for Writ of Certiorari at i–ii, 1–2, Metz (No. 19-1336).

Under ERISA, an employer seeking to withdraw from a multiemployer pension plan must pay its share of unfunded vested benefits, known as the “withdrawal liability.” See 29 U.S.C. § 1381(b)(1). Plans must calculate the withdrawal charge as of the last day of the plan year before the year the employer withdrew, known as the “Measurement Date.” See 29 U.S.C. § 1391. In calculating this charge, plan actuaries must make assumptions, including, as relevant in Metz, about what interest rate to use to discount an employer’s liability for future benefit payments. Applying a higher interest rate would decrease an employer’s withdrawal liability.

In Metz, the plan’s actuaries applied a revised, lower interest rate developed the year following the Measurement than it had applied for the year in which the Measurement date fell, which nearly quadrupled the employer’s liability. Nat’l Ret. Fund v. Metz Culinary Mgmt., Inc., 2017 WL 1157156, at *4 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 27, 2017). An arbitrator found in favor of the employer and ordered that the assumptions and methods in place on the Measurement Date must be used to calculate the employer’s withdrawal liability. Id. The district court vacated the arbitrator’s decision, holding the “withdrawal liability interest rate assumption in effect on the Measurement Date is not applicable to the upcoming plan year unless the actuary affirmatively determines that the assumption . . . is reasonable and her best estimate of anticipated experience under the plan as of the Measurement Date.” Id. at *7.

The Second Circuit disagreed, finding retroactive application of interest rates improper, and holding that “the assumptions and methods used to calculate the interest rate assumption for purposes of withdrawal liability must be those in effect as of the Measurement Date.” Nat’l Ret. Fund v. Metz Culinary Mgmt., Inc., 946 F.3d 146, 151 (2d Cir. 2020). In its petition, the fund argues that the Second Circuit misread the Court’s seminal withdrawal liability opinion, Concrete Pipe & Products of California, Inc. v. Construction Laborers Pension Trust, 508 U.S. 602 (1993), in holding that allowing actuaries to select interest rates “would create significant opportunity for manipulation and bias.” Petition for Writ of Certiorari at 26, Metz (No. 19-1336) (quoting Metz, 946 F.3d at 151).

How courts rule on the proper amount of latitude to give actuaries in calculating withdrawal liability can have an impact measuring in the millions of dollars. Consequently, employers are monitoring the appellate courts as they start to take up these complex issues, which are most often resolved in arbitration. Although the Court may ultimately deny the petition in Metz given the lack of a circuit split on this issue, questions were raised when the Court requested a brief from the respondent employer after it initially waived its response.

III. Delaware Developments

A. Delaware Supreme Court Holds Federal-Forum Provisions Facially Valid

In March, a unanimous Delaware Supreme Court confirmed the facial validity of federal-forum provisions (or “FFPs”), which several Delaware corporations had adopted to require stockholder actions arising under the Securities Act of 1933 to be filed exclusively in federal court. Salzberg v. Sciabacucchi, 227 A.3d 102 (Del. Mar. 18, 2020) (revised Apr. 14, 2020). In Salzberg, the Court was presented with three nearly identical FFPs that had been challenged through a declaratory judgment. Id. On review, the Court determined that the plaintiffs had failed to show that “the charter provisions ‘do not address proper subject matters’ as defined by statute, ‘and can never operate consistently with the law.’” Id. In doing so, the Court emphasized the “broadly enabling” scope of both the Delaware General Corporation Law (“DGCL”) as a whole, and of Section 102(b)(1), which governs the contents of a corporation’s certificate of incorporation. The Court specifically held that Section 102(b)(1) authorizes corporations to adopt provisions regulating matters within an “outer band” of “intra-corporate affairs” extending beyond the “universe of internal affairs” of a Delaware corporation.

As a practical matter, the Court’s ruling likely means that Delaware corporations generally may amend their charters to require claims under the 1933 Act to be filed in federal court. After the United States Supreme Court decision in Cyan, Inc. v. Beaver County Employees Retirement Fund, 138 S. Ct. 1061 (2018)—which, as we discussed in our 2018 Mid-Year Securities Litigation Update, prevents defendants from removing 1933 Act claims to federal courts—plaintiffs began filing 1933 Act claims in state courts at a high rate. As a result, corporations have increasingly been forced to contest duplicative state and federal court litigation throughout the country, rendering corporate amendments minimizing this an attractive option.

The full impact of the Delaware Supreme Court’s decision in Salzberg is yet to be determined, as the extent to which FFPs will be enforced by courts around the country will depend on facts and circumstances unique to each case. Apart from its direct effect, the decision will be of continued interest to practitioners and academics alike for the opportunities it creates. In particular, although the Court explicitly rebuffed the notion that Section 115 of the DGCL might permit modified FFPs to require arbitration of internal corporate claims, practitioners may well continue to push to include arbitration as an exclusive means to resolve certain intra-corporate disputes lying within the “outer bound” of Section 102(b)(1).

B. Another Caremark Claim Survives A Motion To Dismiss

In Hughes v. Hu, the Delaware Court of Chancery once again addressed the degree of particularity with which a plaintiff must plead a Caremark claim. 2020 WL 1987029 (Del. Ch. Apr. 27, 2020). Although duty of oversight claims are notoriously difficult to plead, Delaware courts have recently offered greater clarity on pleading violations of Caremark’s first prong—that directors “utterly failed to implement any reporting or information system or controls.” Id. at *14 (quoting Stone v. Ritter, 911 A.2d 362, 370 (Del. 2006)); see also Marchand v. Barnhill, 212 A.3d 805, 821–22 (Del. 2019) (holding “inference that a board has undertaken no efforts to make sure it is informed of a compliance issue intrinsically critical to the company’s business operation” supports an inference that the board “made no good faith effort to ensure that the company had in place any ‘system of controls’”). In Hughes, the court denied the defendants’ motion to dismiss and held that the plaintiff had pled sufficient facts to support an inference that Kandi Technologies’ directors had willfully breached their duty of oversight. The alleged problem was that Kandi’s directors had consciously failed to “act in good faith to maintain a board-level system for monitoring the Company’s financial reporting.” Id. at *17. The director defendants at issue also comprised a majority of Kandi’s six-member board at the time the complaint was filed (the “Demand Board”), thus excusing demand.

In reaching this conclusion, the court reaffirmed the high pleading bar for Caremark claims, noting that Caremark claims must plead particular facts that could lead to a reasonable inference that a company’s directors either “(a) . . . utterly failed to implement any reporting or information system or controls; or (b) having implemented such a system or controls, consciously failed to monitor or oversee its operations” (i.e., ignored “red flags”). Id. at *14 (quoting Stone, 911 A.2d at 370). Despite this high standard, the court in Hughes found that it was met because Kandi’s directors allegedly “did not make a good faith effort to do their jobs.” Id. at *16. The company’s audit committee only convened “sporadically” for “abbreviated meetings,” often less than once a year, and even then only with minimal efforts to comply with federal securities laws. Id. at *14–16. According to the court, this “pattern of behavior” showed that the directors “followed management blindly,” and “did not make a good faith effort to do their jobs.” Id. at *16.

The court’s other notable conclusion was that demand was excused because Kandi’s board was comprised of a majority of directors who would likely face oversight liability. Under the test set forth in Rales v. Blasband, 634 A.2d 927 (Del. 1993), a director cannot utilize his or her independent and disinterested business judgment when evaluating a litigation demand if “the director is either interested in the alleged wrongdoing or not independent of someone who is.” Hughes, 2020 WL 1987029, at *12. Such a disqualifying interest would exist if there were a “substantial risk” of liability to the director considering the demand, not just a mere threat. Id. Here, four members of Kandi’s board were also named defendants in the complaint as willfully neglecting their duty of oversight. Three members of Kandi’s board also served on the audit committee that only “met sporadically, devoted inadequate time to its work, had clear notice of irregularities, and consciously turned a blind eye to their continuation.” Id. at *14. These facts supported a substantial likelihood of personal liability for these directors, thus making them interested in—and excusing as futile—a litigation demand.

C. Director Independence Remains A Focus Of Delaware Courts

As we noted in our 2019 Year-End Securities Litigation Update, in recent years Delaware courts have reviewed director independence with seemingly reinvigorated scrutiny. See, e.g., Marchand v. Barnhill, 212 A.3d 805 (Del. 2019) (director’s 28-year relationship with CEO’s family rebutted presumption of independence); Sandys v. Pincus, 152 A.3d 124 (Del. 2016) (director’s 50-year friendship with controller rebutted presumption of independence); Del. Cnty. Emps. Ret. Fund v. Sanchez, 124 A.3d 1017 (Del. 2015) (director and controller’s co-ownership of airplane rebutted presumption of independence).

In Voigt v. Metcalf, 2020 WL 614999 (Del. Ch. Feb. 10, 2020), the Court of Chancery continued that trend by closely scrutinizing directors’ independence from a putatively controlling stockholder. There, a stockholder of NCI Building Systems, Inc. (“NCI”) alleged that NCI’s directors, as well as NCI’s largest and allegedly controlling stockholder, Clayton, Dubilier & Rice (“CD&R”), breached their fiduciary duties by causing NCI to acquire one of CD&R’s portfolio companies at a 94% premium. Id. at *1. The persistent and ongoing nature of CD&R’s relationships with a majority of NCI’s directors was the first among myriad “possible sources of influence” cited by the court as contributing to its conclusion that CD&R—which owned 34.8% of NCI’s voting stock—conceivably controlled NCI for purposes of the transaction. Id. at *12, 17.

Of the twelve directors comprising NCI’s board, four directors’ independence were compromised by virtue of being CD&R insiders. Id. at *1. Thus, the court’s analysis focused on four nominally outside directors. Id. at *14–16. Plaintiff alleged that two of these directors derived a substantial portion (if not all) of their income from serving as directors of NCI and other CD&R portfolio companies. Id. at *15–16. Both directors also had a decades-long connections to CD&R portfolio companies, which suggested a persistent and ongoing relationship with CD&R. Id. Accordingly, the directors had an alleged sense of “beholden-ness” towards CD&R, which conceivably subjected them to CD&R’s influence and control. Id.

The court’s independence analysis also focused on allegations concerning two additional directors’ roles as senior members of NCI’s leadership. NCI’s CEO allegedly received millions of dollars in compensation in the years leading up to the disputed merger, from which the court inferred a sense of “owing-ness” towards CD&R. The chairman of NCI’s board learned at an early stage of negotiations that he would be both chairman and CEO of the combined company, the prospect of which allegedly induced him to favor the challenged transaction. Id. at *16. “Under the great weight of Delaware precedent,” the court reasoned, “senior corporate officers generally lack independence for purposes of evaluating matters that implicate the interests of a controller.” Id. (citing, e.g., Rales v. Blasband, 634 A.2d 927, 937 (Del. 1993)). Thus, the court concluded that these directors also conceivably lacked independence with respect to CD&R. Id.

The court’s conclusion that CD&R conceivably controlled NCI required application of the plaintiff-friendly entire fairness standard of review, and ultimately denial of the defendants’ motion to dismiss, id. at *23–24, because the defendants had not attempted to follow the MFW blueprint by conditioning the acquisition upfront on both the approval of a committee and a favorable vote by a majority of unaffiliated shares, id. at *10.

IV. Courts Continue To Grapple With The Supreme Court’s Decision In Lorenzo

As we discussed in our 2019 Year-End Securities Litigation Update, over the course of the past year, courts have begun grappling with how to apply the Supreme Court’s decision in Lorenzo v. SEC, 139 S. Ct. 1094 (2019). In Lorenzo, the Supreme Court held that those who disseminate false or misleading information to the investing public with the intent to defraud can be found liable under Section 17(a)(1) of the Securities Act and Exchange Act Rules 10b-5(a) and 10b-5(c), even if the disseminator did not “make” the statements and thus was not subject to enforcement under Rule 10b-5(b). This holding raised the possibility that secondary actors—such as financial advisors and lawyers—could face liability under Rules 10b-5(a) and 10b-5(c) simply for disseminating the alleged misstatement of another if a plaintiff showed that they knew the statement contained false or misleading information.

One very recent case addressing Lorenzo is In re Cognizant Technology Solutions Corp. Securities Litigation in the District of New Jersey, where a court found that the plaintiffs had adequately alleged scheme liability against the former Chief Legal and Corporate Affairs Officer of the defendant corporation, under both Lorenzo and the “pre-Lorenzo scheme liability framework.” 2020 WL 3026564, at *18–19 (D.N.J. June 5, 2020). The court preceded its discussion of Lorenzo by noting that the two cases were “markedly different”—namely because the Supreme Court’s holding in Lorenzo was limited to situations where the “only conduct involved concerns a misstatement,” id. at *16 (quoting Lorenzo, 139 S. Ct. at 1100 (emphasis original)), whereas in the Cognizant case, the defendant’s alleged “participation in and concealment of the bribery scheme [at issue] extended far beyond the mere dissemination of alleged misstatements,” id. Thus, the finding that the defendant could be liable for disseminating statements he knew to be false was not critical to the conclusion that plaintiffs adequately had pleaded a claim under Rule 10b-5. Nonetheless, the Court expressly rejected the defendant’s attempt to view the alleged misstatement in isolation by arguing that “Lorenzo did not do away with a requirement that the act of dissemination be inherently deceptive,” and instead ruled that Lorenzo did not preclude from liability “instances where the dissemination of a misstatement is preceded by additional allegedly deceptive conduct.” Id. at *17 (emphasis original) (internal quotation marks omitted). In so finding, the Court noted the Supreme Court’s language in Lorenzo that “provisions [under subsections (a) and (c)] capture a wide range of conduct.” Id. (quoting Lorenzo, 139 S. Ct. at 1101 (alteration and emphasis original)).

On the other hand, a court in the Southern District of New York recently rejected an attempt to invoke Lorenzo to support claims for scheme liability under Rule 10b-5. In Geoffrey A. Orley Revocable Trust U/A/D 1/26/2000 v. Genovese, two trusts that had invested in defendant Genovese’s investment fund brought securities law claims against Genovese and two lawyers with regard to alleged misrepresentations about the fund. 2020 WL 611506, at *1–2 (S.D.N.Y. Feb. 7, 2020). The court granted the lawyer defendants’ motions to dismiss, rejecting the plaintiff trusts’ claim that under Lorenzo, one of the lawyer’s “participation in the preparation of” documents used to pitch the trusts on the investment fund gave “rise to primary liability under Rule 10b-5 . . . because such participation was one part of a larger scheme to defraud them.” Id. at *7–8. The Court distinguished the facts in Lorenzo by explaining that the defendant lawyer was “not alleged to have disseminated the statements in the January 2015 brochure or the Privacy Information document,” at issue; therefore, the plaintiff trusts could “not take advantage of any additional liability Lorenzo may have carved out.” Id. at *8 (emphasis added). The Court concluded its discussion by stating that construing the lawyer’s actions “to fall under the prohibitions of paragraphs (a) and (c) [of Rule 10b-5] would serve to erase the distinction between” primary and secondary liability. Id.

Also of note, a court in the Northern District of Illinois denied the defendants’ motion to dismiss and rejected the contention that “claims under Rule 10b-5(a) and (c) cannot be predicated on the same conduct as that supporting claims under Rule 10b-5(b).” SEC v. Kameli, 2020 WL 2542154, at *1, 15 (N.D. Ill. May 19, 2020). The Kameli case arose out of an immigration attorney’s alleged improper handling of funds invested by foreign nationals seeking to obtain visas in order to become U.S. legal permanent residents. See id. at *1–3. In their motion to dismiss, the defendants argued that “conduct used to support a claim under Rule 10b-5(b)—defendants’ false/misleading statements/omissions—cannot also be used as the basis for claims under Rule 10b-5(a) and (c).” Id. at *14. More specifically, they argued that “asserting claims under Rule 10b-5(a) and (c) based only on misrepresentations generally remains verboten under Lorenzo” and that “Lorenzo merely carve[d] out an exception allowing such claims where the defendant is alleged to have disseminated the misrepresentation, rather than having made it.” Id. (emphasis original). Relying on Lorenzo, the Court rejected defendants’ argument, stating that “[t]he Court [in Lorenzo] rejected the notion ‘that [Exchange Act Rules 10b-5(a)–(c)] should be read as governing different, mutually exclusive, spheres of conduct,’ observing that the ‘Court and the Commission have long recognized considerable overlap among the subsections of the Rule and related provisions of the securities laws.’” Id. (quoting Lorenzo, 139 S. Ct. at 1102). Instead the Court explained that “[r]ather than positing a fine distinction between ‘making’ statements and ‘disseminating’ them, Lorenzo effectively abrogated the line of cases on which defendants rely and permits liability under Rule 10b-5(a) and (c) for both making and disseminating misleading statements—despite some resulting redundancy with Rule 10b-5(b).” Id. Notably, the Court went on to point out that, even if the defendants’ position were correct, the complaint did adequately allege that defendants disseminated misleading statements and that defendants engaged in a fraudulent scheme in connection with the purchase or sale of securities. Id. at *15.

Interestingly, notwithstanding Kameli, a court in the Eastern District of Michigan granted the defendants’ motion for summary judgment as to scheme liability claims under Rules 10b-5(a) and 10b-5(c) because the plaintiff did not allege a fraudulent scheme “separate and apart from” the alleged misstatements and omissions. See Gordon v. Royal Palm Real Estate Inv. Fund I, LLLP, 2020 WL 2836312, at *4–5 (E.D. Mich. May 31, 2020). In Gordon, the plaintiff-receiver, who was appointed on behalf of “a convicted Ponzi-schemer,” sued an investment fund and other companies, alleging securities fraud claims and seeking the recovery of money invested in an “allegedly fraudulent investment scheme.” Id. at *1. The plaintiff argued that, in Lorenzo, the Supreme Court “recognize[d] overlap between the 10b-5 provisions and allow[ed] 10b-5 (a) and (b) liability when a defendant disseminates false or misleading statements.” Id. at *5. In rejecting that argument, the Court recognized two “key differences” that distinguished Lorenzo. Id. First, the Court noted that the false statements at issue in Lorenzo occurred before the relevant purchase of securities, whereas in the case at hand the alleged misstatements were made after the relevant securities purchase. Id. Second, the Court pointed out that, while the defendant in Lorenzo disseminated the misstatements of others and was therefore liable for participating in a fraudulent scheme, the defendants before it simply were not involved in the alleged misstatements at issue at all. Id.

Finally, as noted in our 2019 Year-End Securities Litigation Update, the Tenth Circuit seemingly expanded Lorenzo last year by holding that scheme liability could be found based on a failure to correct a misstatement. See Malouf v. SEC, 933 F.3d 1248 (10th Cir. 2019), cert. denied, 140 S. Ct. 1551 (2020). Readers will recall that the Malouf Court accepted that the defendant was liable because, although he did not disseminate the alleged misstatements, he failed to correct the relevant disclosures that he knew were false. To date, this holding has not been adopted by other courts.

If the above cases are any indication, it seems as though parties are invoking the Lorenzo decision in order to stretch the bounds of scheme liability to secondary actors, while some courts remain reticent to expand its holding in the absence of other improper conduct. We will provide a further update on the direction that courts take Lorenzo and scheme liability in our 2020 Year-End Securities Litigation Update.

V. Survey Of Coronavirus-Related Securities Litigation

Unsurprisingly, the unique challenges posed by COVID-19 have given rise to a variety of securities-related lawsuits. As it is too soon to say how courts will broadly view the merits of these actions, we are providing only a survey of these cases. For example, securities class actions concerning COVID-19 have been filed based on alleged (1) false statements concerning a company’s commitment to safety; (2) failure to make sufficiently detailed risk disclosures; and (3) false statements concerning vaccinations, cures, and testing products. Plaintiffs have also asserted at least two insider trading lawsuits, including allegations that Senator Richard Burr improperly traded on information obtained as Chairman of the Senate Intelligence Committee. In addition, government enforcement actions have been filed by both the SEC and the Department of Justice, in each case relating to alleged false statements with respect to COVID-19-related products and tests.

Again, it is too soon to tell how courts will treat COVID-19 in these cases more broadly, but by year’s end some broader themes may emerge. We will continue to monitor developments in these and other coronavirus-related securities litigation cases. Additional resources regarding company disclosure considerations related to the impact of COVID-19 can be found in the Gibson Dunn Coronavirus (COVID-19) Resource Center.

A. Securities Class Actions

1. False Claims Concerning Commitment To Safety

In the Second Circuit, statements concerning a company’s commitment to safety are often considered inactionable because they are “too general to cause a reasonable investor to rely upon them.” In re Vale S.A. Sec. Litig., 2017 WL 1102666, at *21 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 23, 2017) (citations omitted); see also Foley v. Transocean Ltd., 861 F. Supp. 2d 197, 204 n.7 (S.D.N.Y. 2012) (“[W]e note that the statements [regarding commitment to safety and training] would likely be considered expressions of ‘puffery’ that cannot form the basis of a securities fraud claim.”). However, such statements may be found actionable when the company operates in a dangerous industry, where “it is to be expected that investors will be greatly concerned about [its] safety and training efforts,” Bricklayers & Masons Local Union No. 5 Ohio Pension Fund v. Transocean Ltd., 866 F. Supp. 2d 223, 244 (S.D.N.Y. 2012).

Douglas v. Norwegian Cruise Lines, No. 1:20-cv-21107 (S.D. Fla. Mar. 12, 2020): The proposed class action complaint alleges that Norwegian Cruise Lines violated the securities laws by minimizing the likely impact of the coronavirus outbreak on its operations and failing to disclose allegedly deceptive sales practices that downplayed the risks of COVID-19. Purportedly, this failure to disclose caused the company’s statements regarding its commitment to safety to be misleading, including the claim that it places “the utmost importance on the safety of [its] guests and crew.” Norwegian’s stock fell more than 50% in the days after news reports revealed these alleged practices. A putative class action complaint asserting similar claims has been consolidated with Douglas in the Southern District of Florida. See Atachbarian v. Norwegian Cruise Lines, No. 20-cv-21386.

Service Lamp Corp. Profit Sharing Plan v. Carnival Corp., No. 1:20-cv-22202 (S.D. Fla. May 27, 2020): The complaint alleges that Carnival Corp. made false and misleading statements regarding its commitment to safety, including its “commit[ment] to operat[e] a safe and reliable fleet and protect[] the health, safety and security of [its] guests, employees and all others working on [its] behalf.” The stock price slipped after news articles accused the company of failing to adequately protect customers from COVID-19, contrary to its claimed commitments.

2. Failure To Disclose Specific Risks

“Forward-looking statements are protected under the ‘bespeaks caution’ doctrine where they are accompanied by meaningful cautionary language.” In re Am. Int’l Grp., Inc. 2008 Sec. Litig., 741 F. Supp. 2d 511, 531 (S.D.N.Y. 2010). “However, generic risk disclosures are inadequate to shield defendants from liability for failing to disclose known specific risks.” Id.; see also Freudenberg v. E*Trade Fin. Corp., 712 F. Supp. 2d 171, 193 (S.D.N.Y. 2010) (observing generally, in adjudicating a motion to dismiss, that defendants “cannot be immunized for knowingly false statements even if they include some warnings”).

In re Zoom Sec. Litig., No. 5:20-cv-02353 (N.D. Cal. Apr. 7, 2020): Two related putative class actions with substantially similar allegations of securities fraud against Zoom Video Communications, Inc.—Drieu v. Zoom Video Communications, Inc., No. 5:20-cv-02353, and Brams v. Zoom Video Communications, Inc., No. 3:20-cv-02396—were consolidated in the Northern District of California. The operative complaint alleges that Zoom misled shareholders about its data privacy and security measures and failed to disclose that its service was not end-to-end encrypted. According to the complaint, the company’s offering documents contained “generic, boilerplate representations concerning Zoom’s risks related to cybersecurity, data privacy, and hacking,” and “‘catchall’ provisions that were not tailored to Zoom’s actual known risks.”

Wandel v. Gao, No. 1:20-cv-03259 (S.D.N.Y. Apr. 24, 2020): A shareholder in Chinese co-living company Phoenix Tree Holdings Ltd. filed a complaint alleging that the company pushed its January 22, 2020 initial public offering without fully disclosing its pandemic-related risks or the full extent and nature of renter complaints. The company’s risk disclosures were inadequate, the complaint alleges, only “obliquely warn[ing]” that its “business could also be adversely affected by the effects of Ebola virus disease, H1N1 flu, H7N9 flu, avian flu, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, or SARS, or other epidemics,” without specifically referencing COVID-19.

3. False Claims About Vaccinations, Cures, And Testing for COVID-19

Securities class actions regarding medical devices or developments often concern statements about pending approval from the Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”). See, e.g., Tongue v. Sanofi, 816 F.3d 199, 211 (2d Cir. 2016) (holding that there was no conflict between the defendant’s statement of optimism and the FDA’s instructions as to the treatment results necessary for approval); In re Atossa Genetics Inc. Sec. Litig., 868 F.3d 784, 794 (9th Cir. 2017) (finding allegations that defendant’s test did not receive FDA clearance directly contradicted its alleged statements that the test was FDA-cleared); In re Delcath Sys., Inc. Sec. Litig., 36 F. Supp. 3d 320, 333 (S.D.N.Y. 2014) (finding FDA approval statements not actionable “because they were forward-looking statements that fall within the safe harbor provision”). But certain cases, including the recent COVID-19-related suits, have less to do with whether the drug will be approved than whether it will be developed or effective. See, e.g., Abely v. Aeterna Zentaris Inc., 2013 WL 2399869, at *9 (S.D.N.Y. May 29, 2013) (“Plaintiff also failed to allege that a press release contained actionable omissions concerning the drug’s lack of short-term efficacy and its failure to enumerate particular side effects, when defendants made no representation that the drug was effective in the short term and reported ‘serious adverse events’ for those treated with the drug as compared to those given placebo.”).

Yannes v. SCWorx Corp., No. 1:20-cv-03349 (S.D.N.Y. Apr. 29, 2020): The complaint against SCWorx Corp., a service provider to healthcare companies, alleged that the company artificially inflated its stock by falsely claiming to have received a purchase order to sell millions of COVID-19 rapid testing kits. The company’s stock dropped precipitously after an investment research firm referred to the purported deal as “completely bogus” and backed by fraudsters and convicted felons. After Yannes, additional stockholders filed derivative and putative class action claims based on similar allegations. See Lozano v. Schessel, No. 1:20-cv-04554 (S.D.N.Y. June 15, 2020) (derivative complaint); Leeburn v. SCWorx Corp., No. 1:20-cv-04072 (S.D.N.Y. May 27, 2020) (proposed class action).

Wasa Med. Holdings v. Sorrento Therapeutics, Inc., No. 20-cv-00966 (S.D. Cal. May 26, 2020): A shareholder in Sorrento Therapeutics Inc. filed a proposed class action complaint alleging that the company falsely claimed it discovered a COVID-19 “cure.” The stock dropped by nearly half when it was revealed that no cure had in fact been discovered.

McDermid v. Inovio Pharm., Inc., No. 20-cv-1402 (E.D. Pa. Mar. 12, 2020): An investor in Inovio Pharmaceuticals Inc., filed a proposed class action lawsuit alleging that the company’s stock price “more than quadrupled” after its CEO claimed Inovio developed a COVID-19 vaccine “in a matter of about three hours” and could begin testing in early April. The stock price then plummeted by more than 70 percent after a well-known short-seller challenged the veracity of the vaccine claim in a tweet that also called for an SEC investigation into the company’s “ludicrous and dangerous claim.” A derivative suit has also been filed based on similar allegations. See Beheshti v. Kim, No. 2:20-cv-1962 (E.D. Pa. Apr. 20, 2020).

B. Insider Trading

“Under the ‘traditional’ or ‘classical theory’ of insider trading liability, § 10(b) and Rule 10b–5 are violated when a corporate insider trades in the securities of his corporation on the basis of material, nonpublic information.” United States v. O’Hagan, 521 U.S. 642, 651–52, (1997). Thus, “a corporate insider must abstain from trading in the shares of his corporation unless he has first disclosed all material inside information known to him.” Chiarella v. United States, 445 U.S. 222, 227 (1980). “[I]f disclosure is impracticable or prohibited by business considerations or by law, the duty is to abstain from trading.” SEC v. Obus, 693 F.3d 276, 285 (2d Cir. 2012). Under the Stop Trading on Congressional Knowledge Act of 2012 (“STOCK Act”), Pub. L. No. 112–105, 126 Stat. 291 (2012), “Members of Congress . . . are not exempt from the insider trading prohibitions arising under the securities laws, including section 10(b) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and Rule 10b-5 thereunder,” STOCK Act, § 4(a), and “owe[] a duty arising from a relationship of trust and confidence to the Congress, the United States Government, and the citizens of the United States” not to trade on material, nonpublic information derived from their positions in Congress, id. § 4(b)(2), 15 U.S.C. § 78u–1(g)(1). A similar state-law claim in Delaware is known as a Brophy claim, which permits a corporation to recover from its fiduciaries for harm caused by insider trading. Brophy v. Cities Serv. Co., 70 A.2d 5 (Del. Ch. 1949).

Jacobson v. Burr, No. 1:20-cv-00799 (D.D.C. Mar. 23, 2020): On March 23, 2020, a shareholder in Wyndham Hotels and Resorts filed suit against Senator Richard Burr. The complaint alleges that Senator Burr sold securities in a variety of publicly traded companies on material, nonpublic information concerning COVID-19, which he obtained in his capacity as Chairman of the Senate Intelligence Committee. See Dkt. No. 1 at 1. The plaintiff alleged that Senator Burr “injured shareholders . . . who purchased and/or continued to hold securities in the same companies.” Id. On May 1, 2020, the plaintiff announced that he was dismissing the suit without prejudice, “[i]n consideration of the effect that this lawsuit may have on any pending criminal or civil investigation” by the Justice Department and SEC “as well as the effect those investigations will have on the discovery process in this action.” Dkt. No. 6 at 1.

St. Paul Elec. Constr. Pension Plan v. Garcia, No. 2020-0415 (Del. Ch. May 28, 2020): On May 28, 2020, plaintiffs filed suit against the controlling stockholder of a company and other individuals alleging that defendants purchased shares of the company at a price that was too low in light of a decline in the company’s stock price at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Dkt. No. 1 at 1–4, 24. Plaintiffs bring a Brophy claim, as well as derivative claims for breach of fiduciary duty, waste, and unjust enrichment. See id. at 39–44.

C. SEC Cases

SEC v. Praxsyn Corp., No. 9:20-cv-80706 (S.D. Fla. Apr. 28, 2020): On April 28, 2020, the SEC filed a lawsuit against Praxsyn Corp. claiming it had “blatantly” lied about (1) having and being able to acquire and supply large quantities of N95 masks, and (2) “that it was negotiating the sale of millions of masks” and “vetting suppliers to guarantee a dependable supply chain.” Dkt. No. 1 at 1–2. The SEC alleges that internal Praxsyn emails and other documents reveal both claims were false—Praxsyn “never had either a single order from any buyer to purchase masks, or a single contract with any manufacturer or supplier to obtain masks, let alone any masks actually in its possession.” Id. at 2.

SEC v. Turbo Glob. Partners Inc., No. 8:20-cv-01120, (M.D. Fla. May 14, 2020): On May 14, the SEC filed a lawsuit against Turbo Global Partners, Inc. and its CEO, Robert W. Singerman, alleging the company falsely claimed that it was “selling equipment that scans large crowds to detect individuals with elevated fevers,” one of the early warning signs of COVID-19 infection. Dkt. No. 1 at 1–2. The SEC alleges that Turbo’s false statements significantly impacted its securities. For example, “the trading volume doubled” and the stock price increased as much as 15 percent “the day after” Turbo issued one of its allegedly fraudulent press releases. Id. at 1–2.

SEC v. Applied BioSciences Corp., No. 1:20-cv-03729 (S.D.N.Y May 14, 2020): On May 14, the SEC filed suit against Applied BioSciences Corp. alleging that the company “issued a materially misleading press release in which it falsely claimed to be offering and shipping a COVID-19 home test kit to the general public for private use.” Dkt. No. 1 at 1–2. In reality, the suit alleges, the company had not yet shipped any finger-prick tests, did not offer or intend to sell the tests for home or private use by the general public, and had not yet had the test approved by the FDA. Id. at 2.

SEC v. E*Hedge Securities Inc., No. 1:20-cv-22311 (S.D. Fla. June 3, 2020): On June 3, the SEC filed suit against an internet investment advisor firm and its President for failing to turn over its books while touting investment opportunities related to treatments and vaccines for COVID-19. See Dkt. No. 1 at 1–2, 6.

SEC v. Nielsen, No. 5:20-cv-03788 (N.D. Cal. June 9, 2020): On June 9, the SEC brought suit against a penny stock trader allegedly engaged in a fraudulent “pump and dump” scheme involving the stock of a biotechnology company, Arrayit. Dkt. No. 1 at 1. The defendant allegedly posted on an internet forum numerous false and misleading statements regarding the company’s development of a COVID-19 test and FDA approval, which statements were designed to drive up the price of the stock. Id. at 1–2. The trader then sold the stock at the artificially-inflated price. Id. at 2.

D. Criminal Securities Fraud

United States v. Schena, No. 5:20-mj-70721 (N.D. Cal. June 8, 2020): In its first criminal securities fraud case related to COVID-19, the Justice Department brought securities and health care fraud claims against a California biotechnology executive. According to the Complaint, Schena and the company of which he is president, Arrayit Corporation, promoted a quick COVID-19 test that would be done with the same finger-stick test kit the company used to test for allergies. See Dkt. No. 1 at 6, 17. Among other things, however, Arrayit’s promotional materials failed to mention that the FDA had advised it in April that the test “failed to satisfy FDA performance standards” and thus could not qualify for emergency use authorization. Id. at 18. The SEC also alleges that Schena “repeatedly issued” false or misleading “tweets and press releases on Arrayit’s behalf, stating that [its] financial were forthcoming shortly.” Id. at 8.

E. Conclusion

Although a fair number of COVID-19 suits have been filed, the book is far from closed on this topic. Upcoming earnings announcements and other disclosures will undoubtedly be scrutinized carefully by potential plaintiffs and plaintiffs’ attorneys, while whistleblower complaints are likely to increase as the economic impact continues. Regardless of the course COVID-19 takes in the second half of 2020, we expect plaintiffs to continue filing coronavirus-related securities litigation lawsuits. As such, we will continue to monitor developments in these and other cases.

VI. Falsity Of Opinions – Omnicare Update

As we discussed in our prior securities litigation updates, lower courts continue to examine the standard for imposing liability based on a false opinion as set forth by the Supreme Court in Omnicare, Inc. v. Laborers District Council Construction Industry Pension Fund, 575 U.S. 175 (2015). The Supreme Court in Omnicare held that “a sincere statement of pure opinion is not an ‘untrue statement of material fact,’ regardless whether an investor can ultimately prove the belief wrong,” but that an opinion statement can form the basis for liability when the speaker does not “actually hold[] the stated belief,” or when the opinion statement contains “embedded statements of fact” that are untrue. Id. at 184–86. Additionally, an opinion may give rise to liability if facts are omitted that “conflict with what a reasonable investor would take from the statement itself.” Id. at 189. And while decided in the context of a Section 11 claim, Omnicare’s holding has been widely applied to Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5 claims as well. See, e.g., Chapman v. Mueller Water Products, Inc., 2020 WL 3100243 (S.D.N.Y. June 11, 2020).

In the first half of 2020, Omnicare had continued to act as a pleading barrier when proper cautionary language accompanies opinions and when shareholders seek to impose liability when an opinion statement turns out to be incorrect. The Third Circuit recently affirmed the district court’s dismissal of a portion of a shareholder suit arising out of a merger between two banks in Jaroslawicz v. M&T Bank Corp., 962 F.3d 701 (3d Cir. 2020). The court rejected the shareholders’ argument that the bank’s projection of when the merger would close provided grounds for liability because the opinion turned out to be wrong, reaffirming that “a plaintiff cannot state a claim by alleging only that an opinion was wrong.” Id. at 717 (quoting Omnicare, 575 U.S. at 194). The shareholders also alleged that the proxy statement at issue omitted facts about the due diligence the bank performed to form the basis of its opinions—specifically that the “reverse due diligence” lasted at most five business days. The court explained that because the proxy statement disclosed the duration of the due diligence efforts, the bank had sufficiently “divulge[d the] opinion’s basis.” Id. at 718 (quoting Omnicare, 575 U.S. at 195). Even if a reasonable investor may have expected the banks to conduct diligence over a longer period of time, the proxy provided enough information about what the banks did, and that information was enough for shareholders to decide how to vote on the merger. The Court thus rejected the shareholders’ claims because “[c]autionary language surround[ed] the opinions, warning of the uncertainty of projections,” and “these opinions inform, rather than mislead, a reasonable investor.” Id.

Recent district court cases also provide guidance on the types of statements that will not give rise to liability under Omnicare. In Chapman, plaintiff investors alleged that defendants had made a number of false and misleading statements concerning the financial health of the company. The statements at issue included reports on the defendant company’s financial results, its risk disclosures, and a $9.8 million warranty charge; statements made during an investor call discussing quarterly results; and SOX certifications. Chapman, 2020 WL 3100243, at *9-10. The court held that none of the alleged opinion statements qualified as actionable opinions because plaintiffs’ allegations were largely based on conjecture. Plaintiffs offered no evidence suggesting that defendants lacked an “honest belief” in these statements, that defendants knew the information was false, or that the omitted information made the opinions misleading to a reasonable investor. Id. at *10-12, 15, 18-19. In In re Adient plc Securities Litigation, 2020 WL 1644018 (S.D.N.Y. Apr. 2, 2020), plaintiffs alleged that defendant had made false and misleading statements in connection with projections of defendant’s “Metals” business segment. The court rejected plaintiffs’ claims, holding that not only did plaintiffs fail to adequately show that “any Defendant falsely or unreasonably held the opinions they public discussed,” but also that the statements at issue were mere statements of goals and belief that do not run afoul of Omnicare. Id. at *16-17. As such, these statements were found inactionable.

Other recent district court decisions illustrate how plaintiffs may be able to adequately plead allegations and overcome Omnicare’s high bar. For example, in In re Advance Auto Parts, Inc., Securities Litigation, 2020 WL 599543 (D. Del. Feb. 7, 2020), plaintiffs alleged with particularity that defendants had made a series of statements projecting an increase in sales and operating margins at a time when it knew that such projections were not attainable based on information that defendants did not disclose to investors. Id. at *4. The court permitted this claim to go forward because plaintiff specifically pleaded that defendant had omitted several known adverse facts, including that it had disregarded several negative forecasts in late 2016, missed its operating margin “by the largest gap as compared to any point earlier in the year,” and was experiencing an extended downward trend in sales. Id.

As shareholder litigation arising from the economic impact of COVID-19 continues, Omnicare will likely play a significant role. Volatile markets and drops in stock price, together with circumstances that make forward-looking statements and other statements of opinion—including management analysis and expectations, accounting estimates and management valuations, and predictions pertaining to a company’s ability to operate as a going concern—easy to second guess in hindsight may put Omnicare further to the test in the coming quarters.

VII. Halliburton II Market Efficiency And “Price Impact” Cases

As we discussed in our 2018 Year-End Securities Litigation Update, the Second Circuit has shaped the law regarding how defendants can rebut the presumption of reliance under Halliburton Co. v. Erica P. John Fund, Inc., 573 U.S. 258 (2014) (“Halliburton II”), more than any other federal circuit court of appeals since Halliburton II was issued. Recall that, in Halliburton II, the Supreme Court preserved the “fraud-on-the-market” presumption, permitting plaintiffs to maintain the common proof of reliance that is required for class certification in a Rule 10b-5 case, but also permitting defendants to rebut the presumption at the class certification stage with evidence that the alleged misrepresentation did not impact the issuer’s stock price.

As we anticipated in our 2019 Year-End Securities Litigation Update, this year the Second Circuit continued its development of the Supreme Court’s decision in Halliburton II regarding the use of price impact evidence to rebut the presumption of reliance at the class certification stage in its decision in Arkansas Teacher Retirement System v. Goldman Sachs Group, Inc., 955 F.3d 254 (2d Cir. 2020) (“Goldman Sachs II”).

By way of background, the Goldman Sachs plaintiffs allege that the company’s generic statements about its business principles and conflicts omitted material information about alleged conflicts of interest. See Ark. Tchr. Ret. Sys. v. Goldman Sachs Grp., Inc., 879 F.3d 474, 478–80 (2d Cir. 2018) (“Goldman Sachs I”). The first time the case reached the Second Circuit, in Goldman Sachs I, the appellate court vacated the trial court’s order certifying a class and remanded the action, directing that price impact evidence must be analyzed prior to certification, even if price impact “touches” on the merits issue of materiality. Id. at 486. On remand, the district court again certified a class after supplemental briefing, an evidentiary hearing, and oral argument. In re Goldman Sachs Grp. Sec. Litig., 2018 WL 3854757, at *1–2 (S.D.N.Y. Aug. 14, 2018). The district court judge held that while defendants had produced evidence to show that the company’s stock price had not moved in response 36 disclosures regarding the company’s conflicts, the alleged corrective disclosure—a subsequent announcement of regulatory action related to conflicts of interest—was sufficiently different to credit plaintiffs’ expert’s “link between the news of Goldman’s conflicts and the subsequent stock price declines,” and that defendants’ expert testimony was insufficient to “sever” that link. See id. at *3–6.

Defendants appealed again, arguing (1) that “the district court misapplied the inflation-maintenance theory,” which should apply only in limited circumstances, and (2) “that the [district] court abused its discretion by holding that Goldman failed to rebut the Basic presumption by a preponderance of the evidence.” Goldman Sachs II, 955 F.3d at 264.

Defendants were unable to persuade the Second Circuit a second time. On April 7, 2020, a divided Second Circuit panel affirmed the trial court’s second order certifying a class, permitting the plaintiffs to obtain class certification based on Goldman Sachs’ generic public statements without any showing that the statements inflated the stock price, or maintained existing price inflation, when made, because the stock price dropped with the announcement of a related regulatory action. See id. at 258–59, 262–63, 271, 273–74; see also id. at 275 (Sullivan J., dissenting).

The Second Circuit rejected Goldman Sachs’s argument that the “inflation-maintenance” theory—which is frequently the only theory of price impact in Rule 10b-5 cases—may only be applied to “fraud-induced” inflation and should be narrowed to disallow its application to “general statements.” Id. at 265–70. In rejecting that argument, the court held that “the actual issue is simply whether Goldman’s share price was inflated” and not whether the inflation entered the stock price through fraud. Id. at 265. The court characterized defendants’ proposal to disallow inflation maintenance for “general statements” as “a means for smuggling [the merits issue of] materiality into Rule 23.” See id. at 267. The court also found that defendants’ proposed narrowing was “at odds” with the Second Circuit’s prior holding that “theories of ‘inflation maintenance’ and ‘inflation introduction’ are not separate legal categories.” Id. at 268 (quoting In re Vivendi, S.A., Sec. Litig., 838 F.3d 223, 259 (2d Cir. 2016)). The court further explained that the Second Circuit had already “implicitly rejected” Goldman Sachs’s argument in Waggoner v. Barclays PLC, 875 F.3d 79 (2d Cir. 2017), in which inflation maintenance was applied outside of defendants’ proposed limited circumstances. Goldman Sachs II, 955 F.3d at 268–69.

The court also dismissed defendants’ policy arguments that upholding inflation maintenance in these circumstances would “open the floodgates to unmeritorious litigation by allowing courts to certify classes that it believes should lose on the merits,” id. at 269, and that any time allegations of misconduct caused a stock to drop, “plaintiffs could just point to any general statement about the company’s business principles or risk controls and proclaim ‘price maintenance,’” id. (quoting Brief and Special Appendix for Defendants-Appellants at 52–53, Ark. Tchr. Ret. Sys. v. Goldman Sachs Grp., Inc., 955 F.3d 254 (2d Cir. 2020) (No. 18-3667), ECF No. 62). In the court’s view, Second Circuit case law provides defendants with opportunities to challenge materiality in a motion to dismiss, motion for summary judgment, and at trial, and with the opportunity to challenge price impact at the class certification stage. See id. at 269–70.

The Second Circuit went on to find no abuse of discretion in the district court’s “holding that Goldman failed to rebut the Basic presumption.” See id. at 270–74. The opinion describes defendants’ task in meeting the burden of persuasion to disprove price impact, see Waggoner, 875 F.3d at 99–103 (assigning the burden of persuasion to defendants in the Second Circuit), as a requirement to “show by a preponderance of the evidence that the entire price decline on the corrective-disclosure dates was due to something other than the corrective disclosures.” Goldman Sachs II, 955 F.3d at 271. Assigning a stock price decline to a corrective disclosure does not amount to a showing of price impact by an alleged misstatement unless the corrective disclosure reveals something that corrects a challenged statement. See Halliburton II, 573 U.S. at 277–78.

Defendants’ “primary contention” was that the district court’s decision was clearly erroneous because it ignored defendants’ uncontested evidence that the market did not react to 36 earlier press reports “touch[ing] on” Goldman Sachs’ alleged conflicts. Goldman Sachs II, 955 F.3d at 271. The Second Circuit rejected this argument, because it believed that the district court had not abused its discretion in finding that plaintiffs had shown that the 37th disclosure revealed new, “hard evidence” of conflicts sufficient to create a “link” between the alleged misstatements and the stock price drop. Id. (quoting In re Goldman Sachs, 2018 WL 3854757, at *4–5). It emphasized the role in the standard of review in this case by acknowledging “one of us given the same task as that of the district judge” may have “conclude[d] otherwise.” Id. at 274.

Judge Sullivan dissented. He explained that he would reverse because Goldman Sachs had “sever[ed] the link that undergirds the Basic presumption” with its “persuasive and uncontradicted evidence that Goldman’s share price was unaffected by earlier disclosures of Defendants’ alleged conflicts of interest.” Id. at 275. He went on to explain why, despite agreeing that “the district court did not misapply the inflation-maintenance theory of price impact,” he nonetheless “believe[d] that the majority [erred in] uncritically accept[ing] the district court’s conclusions regarding what rebuttal evidence is necessary to overcome the Basic presumption.” Id. To this end, Judge Sullivan distinguished precedent such as Waggoner, noting that Goldman Sachs “demonstrated that the prior disclosures . . . had no impact on [its] stock price,” id. at 278, and, thus “sever[ed] the link between the alleged misrepresentation and . . . the price . . . paid by the plaintiff,” id. (quoting Waggoner, 875 F.3d at 95). Notably, Judge Sullivan concluded, contra the majority, that “it’s fair for this court to consider the [general] nature of the alleged misstatements in assessing whether and why ‘the misrepresentations did not in fact affect the market price of Goldman stock.’” Id. (quoting Goldman I, 879 F.3d at 486).

The disagreement between the majority and the dissent in Goldman Sachs II is emblematic of questions that continue to arise in trial courts, as well. For example, in In re Chicago Bridge & Iron Co. N.V. Securities Litigation, the District Court for the Southern District of New York rejected a special master’s recommended “correctiveness” test that would have inquired whether the corrective disclosure “relates to the same subject matter” as the misrepresentation or is “wholly unrelated.” 2020 WL 1329354, at *5–7 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 23, 2020). Instead, the court reemphasized the need for the alleged misstatement to be “linked” to the corrective disclosure. Id. at *6.

On June 15, 2020, the Second Circuit denied the defendants’ petition for rehearing en banc in Goldman Sachs II, Order, Ark. Tchr. Ret. Sys. v. Goldman Sachs Grp., Inc., No. 18-3667 (2d Cir. June 15, 2020), ECF No. 277, and stayed the case pending the filing of a petition for a writ of certiorari, id. at ECF No. 288.

Given the importance of the issue, the extant circuit split on the viability of the inflation maintenance theory, and related issues, more is anticipated in this space soon. Accordingly, we will continue to monitor developments in Goldman Sachs II and related cases.

VIII. ERISA Litigation

Where employer stock is offered as an investment option in employee retirement plans, securities litigation is often accompanied by claims under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (“ERISA”). The first half of 2020 saw significant ERISA litigation activity, including the Supreme Court’s recent Sulyma decision clarifying the statute of limitations for fiduciary breach claims. Lower courts have also been active in the wake of the Court’s January decision in Retirement Plans Committee of IBM v. Jander, 140 S. Ct. 592 (2020), in addition to analyzing the requirements for fiduciary breach claims, pleading standards for claims partly grounded in fraud, and the applicability of arbitration agreements.

A. Supreme Court Clarifies “Actual Knowledge” Trigger For Three-Year Limitations Period In Fiduciary Breach Cases

In February, the Supreme Court unanimously held in Intel Corporation Investment Policy Committee v. Sulyma, 140 S. Ct. 768 (2020), that for purposes of ERISA’s limitations period in fiduciary breach cases, a fiduciary’s disclosure of plan information alone does not create “actual knowledge” subjecting such claims to the statute’s shorter three-year period absent proof that a beneficiary actually read the disclosures. Gibson Dunn submitted an amicus brief on behalf of the National Association of Manufacturers, the Chamber of Commerce of the United States, the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association, the American Benefits Counsel, the ERISA Industry Committee, and the American Retirement Association in support of petitioner Intel Corp. Investment Policy Committee.

ERISA Section 413(2) requires claims for breach of fiduciary duty to be brought no later than “three years after the earliest date on which the plaintiff had actual knowledge of the breach or violation.” 29 U.S.C. § 1113(2). Absent “actual knowledge,” breach of fiduciary duty claims under ERISA must be brought within six years of the breach or violation. Id. § 1113(1). In 2015, Christopher Sulyma, a former Intel employee, sued multiple retirement plans, claiming the plans improperly over-invested in alternative investments. Sulyma, 140 S. Ct. at 774-75. More than three years, but fewer than six years, before that suit was filed, Sulyma had received plan disclosures that described the investments Sulyma claimed were imprudent. Id. The Ninth Circuit held that the disclosures alone did not trigger the three-year bar because Sulyma testified he had not read the disclosures and Intel had not established Sulyma had subjective awareness of what was disclosed. Id.

The Supreme Court affirmed, clarifying that the statutory phrase “actual knowledge” means what it says: a plaintiff must in fact have become “aware of” the information pertaining to the alleged breach or violation. Id. at 771. Disclosure of plan information alone does not trigger the three-year limitations period in Section 413(2). Id.

As a result, retirement plans and their sponsors may be susceptible to claims reaching back more than three years to the extent participants need only allege that they did not read plan disclosures advising of certain investments, fees or returns, in order to expand the ERISA statute of limitations from three to six years. However, the Court left open questions about how to prove “actual knowledge” based on circumstantial evidence or “willful blindness.” See Sulyma, 140 S. Ct. at 779. Only a few lower courts have applied this decision so far. See, e.g., Toomey v. DeMoulas Super Markets, Inc., No. 19-cv-11633, 2020 WL 3412747, at *4 (D. Mass. April 16, 2020) (declining to dismiss based on plaintiff’s allegation of lack of actual knowledge); Moitoso v. FMR LLC, No. 18-cv-12122, 2020 WL 1495938, at *4 n.3 (D. Mass. Mar. 27, 2020) (same).

B. Lower Court Developments

1. ESOP Fiduciary Claims After Jander

Readers will recall that, as we discussed in our 2019 Year-End Securities Litigation Update, the Supreme Court heard argument in November 2019 in Retirement Plans Committee of IBM v. Jander on the question whether the “more harm than good” pleading standard from Fifth Third Bancorp v. Dudenhoeffer, 573 U.S. 409, 430 (2014), can be satisfied by generalized allegations that the harm resulting from the inevitable disclosure of an alleged fraud generally increases over time. Rather than deciding that question, the Court remanded the case in January to allow the Second Circuit to address two unresolved issues raised by the parties: (1) whether ERISA ever imposes a duty on a fiduciary for an employee stock option plan (ESOP) to act on inside information, and (2) whether ERISA requires disclosures that are not otherwise required by the securities laws. 140 S. Ct. 592 (2020) (per curiam). Justice Kagan (joined by Justice Ginsburg) and Justice Gorsuch filed dueling concurrences addressing those questions and disputing whether they were properly presented in this case.

On remand, the Second Circuit reinstated the judgment entered pursuant to its original opinion—an uncommon win for plaintiffs in this area. Jander v. Ret. Plans Comm. of IBM, 962 F.3d 85 (2d Cir. 2020) (per curiam). The court agreed with Justice Kagan’s suggestion that the additional arguments raised by defendants and the government in supplemental briefing “either were previously considered by this Court or were not properly raised,” and therefore were forfeited. Id. at 86.

Other lower courts have continued to apply the Dudenhoeffer pleading standard, offering varying answers to the questions raised by the Supreme Court in Jander. In Varga v. General Electric Company, No. 18-cv-1449, 2020 WL 1064809 (N.D.N.Y. Mar. 5, 2020), the court dismissed a class action complaint alleging that General Electric violated its fiduciary duties owed to participants of the GE Retirement Savings Plan, which offered an ESOP that invested all of its assets in GE common stock. Id. at *5. The complaint alleged that the defendants breached their fiduciary duties of prudence and loyalty by continuing to invest in GE stock despite knowing, and failing to disclose, the company’s $15 billion insurance funding shortfall. Id. at *1. The court interpreted Dudenhoeffer as requiring a plaintiff to plausibly allege an alternative action that the defendant could have taken that would have been consistent with the securities laws and that a prudent fiduciary in the same circumstances would not have viewed as more likely to harm the company stock fund than to help it. Id. at *3. It rejected the two alternatives suggested by plaintiffs: (1) disclose the problem earlier, or (2) close the GE Stock Fund to additional investments once they knew, or should have known, of the insurance reserve problem. Id. The first alternative failed to satisfy the requirement that a prudent fiduciary could not have concluded that the alternative would do more harm than good, and the second alternative failed Dudenhoeffer’s pleading standard because it rested purely on speculation. Id. at *4.

In Perrone v. Johnson & Johnson, No. 19-cv-923, 2020 WL 2060324 (D.N.J. Apr. 29, 2020), the court dismissed a fiduciary breach class action complaint concerning Johnson & Johnson’s failure to disclose information related to allegations of cancer-causing asbestos in the company’s talc powder on grounds similar to Varga. The court reasoned in part that plaintiffs failed to meet their burden under Dudenhoeffer because they alleged an alternative action (corrective disclosure) that would have been impermissibly taken in defendants’ corporate, as opposed to its fiduciary, capacity. In so ruling, the district court drew “support from Justice Gorsuch’s concurrence to the per curiam opinion remanding Jander.” Id. at *16.

2. Defined-Contribution Plan Fiduciary Claims

Other recent decisions have addressed claims by defined-contribution plan participants for breach of the duties of prudence and diversification. ERISA requires the fiduciary of a pension plan to act prudently in managing the plan’s assets, but what that requirement entails may vary depending on the type of plan at issue, giving rise to complex questions in securities-related litigation.

The Seventh Circuit affirmed the dismissal of one such claim in Divane v. Northwestern University, 953 F.3d 980 (7th Cir. 2020). The court held plaintiffs did not allege a fiduciary breach by alleging, inter alia, that defendants provided investment options that were too numerous, too expensive, or underperforming—notwithstanding decisions of the Third and Eighth Circuits potentially suggesting otherwise. Id. at 991 (citing Braden v. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc., 588 F.3d 585, 596 (8th Cir. 2009) (finding imprudence where investment plan offered “relatively limited menu of funds . . . chosen to benefit the trustee at the expense of the participants”); Sweda v. Univ. of Pennsylvania, 923 F.3d 320, 330 (3d Cir. 2019) (stating that offering a “meaningful mix and range of investment options” does not automatically “insulate[] plan fiduciaries from liability for breach of fiduciary duty”)).

The Fifth Circuit affirmed the dismissal of a putative fiduciary breach class action in Schweitzer v. Investment Committee of Philips 66 Savings Plan, 960 F.3d 190 (5th Cir. 2020). Schweitzer first addressed the scope of the statutory definition of qualifying employer securities exempt from the otherwise applicable fiduciary duties of diversification. The ERISA statute defines such a security as a “security issued by an employer of employees covered by the plan, or by an affiliate of such employer.” 29 U.S.C. § 1107(d)(1). Here, the court rejected the defendants’ argument that the funds at issue (investing in ConocoPhillips stock) were qualifying employer securities, because an intervening spinoff had made a new entity (Phillips 66) the employer for statutory purposes. 960 F.3d at 195. But the court nevertheless held that the defendants satisfied their fiduciary obligations by allowing plan participants to choose to retain their previous investments in those funds, while closing the funds to new investments post-spinoff. Id. at 196, 199.

3. Pleading Standards For Claims Partly Grounded In Fraud

In Vigeant v. Meek, 953 F.3d 1022, 1026 (8th Cir. 2020), the Eighth Circuit highlighted a recurring issue regarding which pleading standard should be applied when a complaint for breach of ERISA fiduciary duties contains specific allegations that are grounded in fraud. The Eighth Circuit agreed with the district court that an allegation grounded in fraud must be pleaded, and considered by a court, according to the specificity required by Rule 9(b) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. Id. The remaining allegations, however, are to be considered under the less rigorous plausibility standard under Rule 8.

4. Arbitrability Of ERISA Claims

The extent to which ERISA plan participants can be required to arbitrate fiduciary duty-related disputes has also continued to be litigated in the securities context. In Ramos v. Natures Image, Inc., No. 19-cv-7094, 2020 WL 2404902, (C.D. Cal. Feb. 19, 2020), the court partially denied a motion to compel arbitration on an ERISA claim for breach of fiduciary duty, even though the individual employee plaintiffs had signed arbitration agreements. Unlike other employment-related claims, under Ninth Circuit precedent, the ERISA claims “ultimately belong to the plan,” not the individual employee, and hence are not arbitrable “without consent from the plan to arbitrate.” Id. at *7–8 (citing Munro v. Univ. of S. Cal., 896 F.3d 1088, 1092 (9th Cir. 2018)).