2023 Year-End Sanctions and Export Controls Update

Client Alert | February 7, 2024

2023 was another extraordinarily active year in the world of trade controls, including sweeping new trade restrictions on Russia and China, aggressive enforcement of sanctions and export controls, and extensive collaboration among sister agencies and partner countries.

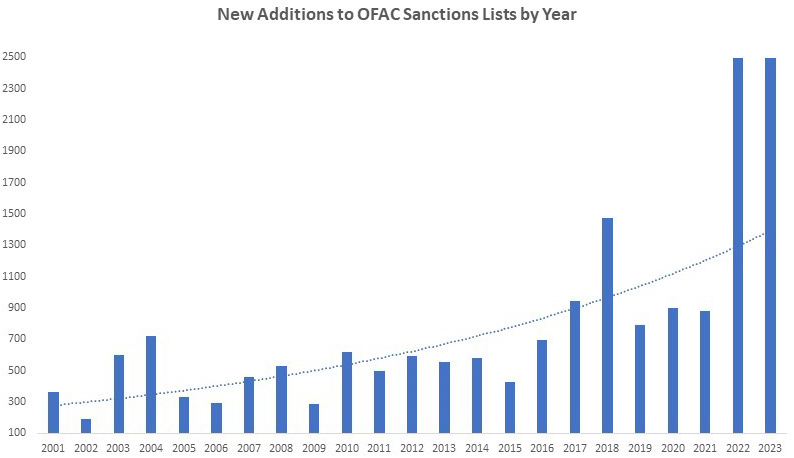

In 2023, the United States, the European Union, and the United Kingdom continued to push the limits of economic statecraft by imposing new trade restrictions on major economies such as Russia and China, and aggressively enforcing existing measures. Throughout his tenure, President Biden has imposed sanctions at an unprecedented rate by adding nearly 5,500 names to restricted party lists maintained by the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (“OFAC”)—a yearly average nearly double that of the Trump administration and triple the pace under President Obama. Approximately one-third of all parties presently on U.S. sanctions lists were placed there by President Biden. That sharp upswing continued in 2023 as the United States added a near-record number of individuals and entities to OFAC sanctions lists:

In addition to the sheer number of new sanctions designations, the past year was noteworthy for the scale and scope of enforcement actions targeting sanctions and export control violations. OFAC and the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (“BIS”) each issued record-breaking civil monetary penalties measured in the hundreds of millions of dollars and closely coordinated with the U.S. Department of Justice to mount criminal prosecutions—marking a historically aggressive approach to enforcing trade controls.

Indeed, a high degree of collaboration among sister agencies and partner countries was one of the signal developments of the past year as policymakers in Washington, London, and other allied capitals magnified the impact of sanctions, export controls, import restrictions, and foreign investment reviews by frequently issuing joint guidance and tightly aligning their controls to make trade restrictions more challenging for Moscow, Beijing, and other targets to evade.

As roughly half the world’s population prepares to head to the polls over the next twelve months—including in major elections in the United States, the European Union, and the United Kingdom—policymakers have little incentive to slow their use of economic coercive measures before facing their electorates. Very few politicians would be criticized for demonstrating strength against adversaries and competitors via enhanced sanctions or export controls. All the more so because tools like sanctions and export controls can be promulgated with little perceived risk and even more limited perceived cost to the governments imposing them. As a consequence, the heavy use of trade controls as a primary instrument of foreign policy appears poised to continue its growth regardless who occupies the White House, Downing Street, or any of the other halls of power up for grabs in 2024.

I. Global Trade Controls on Russia

A. Blocking Sanctions

B. Services Prohibitions

C. Price Cap on Crude Oil and Petroleum Products

D. Export Controls

E. Countering Evasion

F. Secondary Sanctions

G. Import Prohibitions

H. Possible Further Trade Controls on Russia

II. U.S. Trade Controls on China

A. Export Controls

B. Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act

C. Industrial Policy

D. Investment Restrictions

E. Possible Further Trade Controls on China

A. Venezuela

B. Iran

C. Myanmar

D. Sudan

E. Counter-Terrorism

F. Other Major Sanctions Programs

G. Crypto/Virtual Currencies

H. OFAC Enforcement Trends and Compliance Lessons

V. Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS)

A. CFIUS Annual Report

B. Expanded Jurisdiction

C. State Law Investment Restrictions

D. Geographic Focus

VI. U.S. Outbound Investment Restrictions

A. Proposed Rulemaking

B. Public Comments and Unresolved Issues

A. Trade Controls on China

B. Sanctions Developments

C. Export Controls Developments

D. Foreign Direct Investment Developments

A. Trade Controls on China

B. Sanctions Developments

C. Export Controls Developments

D. Foreign Direct Investment Developments

I. Global Trade Controls on Russia

Following the Kremlin’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in early 2022, a coalition of leading democracies—including the United States, the European Union, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and Japan—unleashed a historic barrage of trade restrictions on Russia. As the war in Ukraine stretched on into 2023, the United States and its allies shifted from rapidly introducing new and often novel trade controls to incrementally expanding existing measures such as blocking sanctions, services bans, export controls, and import bans. To further pressure Moscow, the United States authorized secondary sanctions on foreign financial institutions that, knowingly or unknowingly, facilitate significant transactions involving Russia’s military-industrial base, and partnered with allied countries to crack down on sanctions and export control evasion. Such seemingly disparate measures were each calculated to deny Russia the capital and materiel needed to wage war in Ukraine. The European Union and the United Kingdom—each departing from their historic practice—increasingly imposed extraterritorial measures, including asset freezes on third-country entities that support Russia’s war in Ukraine or that facilitate the contravention of relevant prohibitions.

These restrictions have generally been effective at “pouring sand into the gears” of Russia’s war machine as the Kremlin has experienced shortages of key components such as semiconductors, employed elaborate transshipment schemes, and turned to suppliers of last resort like North Korea and Iran to restock its arsenal. Such trade restrictions also appear to be exacting a toll on Russia’s broader economy as soaring defense spending has led to rising inflation, widening budget deficits, and forgone investment in priorities such as education and healthcare that threaten to sap Russia’s long-term growth prospects. By imposing countermeasures that restrict companies’ ability to depart Russia, including an “exit tax” and outright asset seizures, Moscow risks further chilling foreign investment. Meanwhile, the coalition continues to hold a handful of policy options in reserve. Depending upon events on the ground and political dynamics at home, U.S. and allied officials could in coming months escalate economic pressure on Russia by designating additional sanctions and export control evaders, further restricting exports of sensitive components, or severing from the U.S. financial system one or more foreign banks for enabling Russia’s ongoing military campaign. They could even go after various third rails in Russia—further restricting gas flows and potentially seizing Russian state assets (including central bank assets) held abroad.

Since February 2022, the United States, the European Union, and the United Kingdom, in an extraordinary burst of activity, have each added thousands of new Russia-related individuals and entities to their respective consolidated lists of sanctioned persons. While the lists do not entirely overlap, which has increased the compliance burden on multinational firms, the level of coordination among the allies has magnified the impact of sanctions by making them more challenging to evade. Underscoring the breadth of new sanctions designations, the United States on seven occasions this past year alone added 100 or more new Russia-related targets to OFAC’s Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons (“SDN”) List—an astonishing pace considering that around 10,000 parties had been added to the SDN List over the preceding twenty years combined. The European Union also designated more than 100 individuals and entities as part of its Russia sanctions program on three separate occasions, and the United Kingdom reached similar heights on two occasions, in 2023. This pace of change, combined with the breadth and depth of such changes, has made it increasingly difficult for the private sector to keep up.

Blocking sanctions are arguably the most potent tool in a country’s sanctions arsenal, especially for countries such as the United States with an outsized role in the global financial system. Upon becoming designated an SDN (or other type of blocked person), the targeted individual or entity’s property and interests in property that come within U.S. jurisdiction are blocked (i.e., frozen) and U.S. persons are, except as authorized by OFAC, generally prohibited from engaging in transactions involving the blocked person. The same applies to persons designated by the European Union or the United Kingdom. The SDN List, and its EU and UK equivalents, therefore function as the principal sanctions-related restricted party lists. Moreover, the effects of blocking sanctions often reach beyond the parties identified by name on these lists. By operation of OFAC’s Fifty Percent Rule (or, in the EU and the UK, the even broader ownership and control tests), restrictions generally also extend to entities owned 50 percent or more in the aggregate by one or more blocked persons (or, in the EU and the UK, entities that are majority-owned or controlled by blocked persons), whether or not the entity itself has been explicitly identified.

During 2023, the allies repeatedly used their targeting authorities to block Russian political and business elites, as well as substantial enterprises operating in sectors such as banking, energy, and technology seen as critical to financing and sustaining the Kremlin’s war effort. Notable designations included:

- Government officials, including Russian cabinet ministers and regional governors;

- Russian oligarchs such as Petr Aven, Mikhail Fridman, German Khan, and Alexey Kuzmichev—many of whom were already targeted by the European Union and the United Kingdom—plus wealthy associates of Belarus’s President Alyaksandr Lukashenka;

- Financial institutions, including Credit Bank of Moscow and Tinkoff Bank, as a result of which over 80 percent of Russia’s banking sector by assets is now sanctioned;

- Energy firms such as Arctic Transshipment LLC and LLC Arctic LNG 2, which were targeted to limit Russia’s current energy revenues and future extractive capabilities;

- Military-industrial firms, including hundreds of companies operating in the technology, defense and related materiel, construction, aerospace, and manufacturing sectors of Russia’s economy, dealings with which (as discussed further below) can now place foreign financial institutions at risk of being cut off from the U.S. financial system; and

- Third-country facilitators of sanctions and export control evasion, including shipping companies and vessels alleged to have violated the price cap on Russian crude oil and petroleum products, plus dozens of parties located in major transshipment hubs such as Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, and China.

Many of the parties described above were designated pursuant to Executive Order (“E.O.”) 14024, which authorizes blocking sanctions against persons determined to operate or have operated in certain sectors of the Russian Federation economy identified by the U.S. Secretary of the Treasury.

In addition to naming more than 1,000 new Russia-related individuals, entities, vessels, and aircraft to their respective sanctions lists, the United States and the European Union this past year continued to expand the potential bases upon which parties can become designated for engaging with Russia. The European Union introduced a new criteria for designation whereby persons who benefit from the forced transfer of ownership or control over Russian subsidiaries of EU companies can become subject to asset freeze measures. Meanwhile, building upon the ten sectors that had been identified in prior years, the Biden administration during 2023 authorized the imposition of blocking sanctions on parties that operate in Russia’s metals and mining, architecture, engineering, construction, manufacturing, and transportation sectors—which appear to have been selected for their potential to generate hard currency or to, directly or indirectly, contribute to Russia’s wartime production capabilities. Crucially, OFAC has indicated that parties operating in those sectors are not automatically sanctioned, but rather risk becoming sanctioned if they are determined by the Secretary of the Treasury to have engaged in targeted activities. That said, after initially treading lightly around Russian oil, gas, and metals producers to avoid roiling global markets, the Biden administration in recent months has shown a growing willingness to impose blocking sanctions on participants in Russia’s extractive industries, as well as on third-country sanctions and export control evaders. These trends appear poised to continue during the year ahead.

Since the opening months of the war in Ukraine, the United States, the European Union, and the United Kingdom have supplemented their use of blocking sanctions by banning the exportation to Russia of certain professional, technical, and financial services—especially including services used to bring Russian energy to market.

Executive Order 14071 prohibits the exportation from the United States, or by a U.S. person, of any category of services as may be determined by the Secretary of the Treasury, to any person located in the Russian Federation. Acting pursuant to that broad and flexible legal authority, the United States during the first year of the war barred U.S. exports to Russia of ten categories of services that, if misused, could enable sanctions evasion, bolster the Russian military, and/or contribute to Russian energy revenues. In May 2023, the United States expanded upon those earlier prohibitions by barring the exportation to Russia of architecture and engineering services in a seeming effort to prevent U.S. technical expertise from being used to enhance Russia’s energy and military infrastructure.

The European Union and the United Kingdom have similarly prohibited the provision of a range of professional services to entities in Russia, subject to limited exceptions. During the past year, the European Union tweaked the range of available derogations and exceptions and expanded the scope of its professional services restrictions to include the provision of software for the management of enterprises and software for industrial design and manufacture. The United Kingdom implemented a new, strictly framed ban on the provision of legal advisory services—which temporarily froze the ability of lawyers in the country to advise on a wide scope of even Russia-related issues. Fortunately, this situation was eased by the issuance of a general license shortly thereafter.

Those incremental adjustments aside, over the past year the allies chiefly focused on implementing and enforcing a novel form of services ban designed to cap the price of seaborne Russian crude oil and petroleum products.

C. Price Cap on Crude Oil and Petroleum Products

Effective December 5, 2022, the United States, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and the United Kingdom, alongside the European Union and Australia (collectively, the “Price Cap Coalition”), prohibited the provision of certain services that support the maritime transport of Russian-origin crude oil from Russia to third countries, or from a third country to other third countries, unless the oil has been purchased at or below a specified price. A separate price cap with respect to Russian-origin petroleum products became effective on February 5, 2023. The types of services that are potentially restricted varies modestly among the Price Cap Coalition countries, but generally includes activities such as brokering, financing, and insurance. A detailed analysis of the price cap, and how it is being implemented by key members of the Price Cap Coalition, can be found in a previous client alert.

From a policy perspective, the price cap is intended to curtail Russia’s ability to generate revenue from the sale of its energy resources, while still maintaining a stable supply of these products on the global market. The measure is also designed to avoid imposing a blanket ban on the provision of all services relating to the transport of Russian oil and petroleum products, which could have far-reaching and unintended consequences for global energy prices. Accordingly, the price cap functions as an exception to an otherwise broad services ban. Best-in-class maritime service providers, which are overwhelmingly based in Price Cap Coalition countries, are permitted to continue supporting the maritime transport of Russian-origin oil and petroleum products, but only if such oil or petroleum products are sold at or below a certain price.

After spending much of the prior year designing the price cap mechanism, the coalition during 2023 shifted to implementing and enforcing this new and untested policy instrument—and were quickly met with Russian efforts at circumvention. For example, tankers carrying Russian crude oil sold above the price cap have reportedly used deceptive practices such as falsifying location data and transaction documents to continue availing themselves of coalition services. Such activities prompted OFAC in April 2023 to publish an alert warning that shipments from Russia’s Pacific coast, including especially the port of Kozmino where a substantial oil pipeline terminates, may present elevated risks of price cap evasion.

As the year progressed, Russia-related parties heavily invested in building a so-called “shadow fleet” that, instead of illicitly using Price Cap Coalition service providers, seeks to avoid coalition services altogether. Broadly speaking, the shadow fleet (also known as the “ghost fleet”) involves an alternative ecosystem of hundreds of aging and questionably seaworthy oil tankers, backed by sub-standard insurers, that operate outside the jurisdiction of Price Cap Coalition countries. By virtue of their age, opaque ownership, and questionable financial backing, such oil tankers are at high risk of accidents and unlikely to bear the cost of damage to other vessels or the environment. As a consequence, many ports refuse calls by these vessels. Nevertheless, as these vessels offer oil above the price cap and below the market price, for some jurisdictions, the economics of this oil has proven too attractive to turn down. As a result, the shadow fleet has contributed to Russian oil being sold at an increasingly narrow discount to global prices. Over the long term, this could further undercut the price cap’s efficacy. Coalition policymakers meanwhile cite the shadow fleet as evidence that the price cap is at least partially succeeding in diverting resources from the war in Ukraine. In short, said one U.S. official, “buying tankers makes it harder for the Kremlin to buy tanks.”

Amid questions about the price cap’s continuing effectiveness, the coalition during the final months of the year pivoted to a second phase of implementation that has so far involved imposing blocking sanctions on a small, but growing, number of maritime industry participants and issuing updated guidance to compliance-minded companies.

Notably, OFAC in October, November, and December 2023, and continuing in January 2024, added a total of 39 shipping companies, vessels, and oil traders to the SDN List for their alleged involvement in using Price Cap Coalition service providers to transport Russian-origin crude oil priced above $60 per barrel after the price cap policy became effective. Such limited designations appear to have been calibrated as a series of warning shots—reflecting the delicate balance that policymakers face in deterring market participants from facilitating the transport of high-priced Russian oil without clamping down so aggressively as to spook financial institutions, shippers, and oil traders away from lawful dealings in Russian oil, which could reduce supply and drive up global energy prices. Moreover, policymakers are being careful to balance broader geopolitical interests to avoid seeing the rest of the BRICS, for example, more aggressively support Moscow’s revanchism. Even so price cap-related designations appear highly likely during the months ahead.

Concurrent with the initial round of designations described above, the Price Cap Coalition in October 2023 published an advisory describing for maritime oil industry participants, including governmental and private sector actors, suggested best practices to minimize the risk of enabling a prohibited transaction involving Russian oil. Although many of the advisory’s suggestions hew closely to the U.S. Government’s 2020 Global Maritime Sanctions Advisory, such as monitoring for signs that a vessel has improperly disabled its location-tracking Automatic Identification System and/or engaged in ship-to-ship transfers, the coalition also offers a number of price cap-specific recommendations. Among other measures, industry participants are encouraged to require oil tankers to carry legitimate and properly capitalized insurance; be certified as seaworthy by a reputable classification society; and furnish itemized invoices that separately list all ancillary costs (e.g., shipping, insurance, freight) so that the price at which the underlying Russian oil was sold can be readily determined.

To steer clear of a potential enforcement action, service providers from Price Cap Coalition countries that deal in seaborne Russian crude oil or petroleum products need to be able to provide certain evidence that the price cap was not breached in respect of the shipment that they are servicing. For example, the United States, the European Union, and the United Kingdom have each set forth a detailed recordkeeping and attestation process by which maritime transportation industry actors can benefit from a “safe harbor” from prosecution arising out of violations by third parties. In December 2023, the Price Cap Coalition released more stringent guidance requiring service providers based in Price Cap Coalition countries to collect attestations with greater frequency and to gather more granular pricing information. To benefit from the safe harbor, covered service providers now must receive attestations each time they lift or load Russian-origin oil or petroleum products, and must also retain, provide, or receive an itemized list of ancillary costs such as shipping, insurance, and freight, which additional information is designed to prevent transaction parties from obscuring the price at which Russian oil was sold.

In parallel, the European Union in December 2023 moved to bolster the price cap by requiring EU operators to obtain authorization from a national competent authority prior to selling or transferring ownership of an oil tanker to a Russian individual or entity, or for use in Russia. EU operators must also notify a national competent authority of each sale or transfer of a tanker to parties based in third countries (i.e., other than the European Union or Russia). These EU measures are calculated to stunt the growth of Russia’s shadow fleet.

During 2023, the United States, the European Union, and the United Kingdom continued to find ways to expand their already unprecedented range of export controls targeting Russia and Belarus. Many of these changes either build upon novel controls introduced in 2022, or seek to align each jurisdiction’s existing controls with those implemented by allies and partners.

In conjunction with the first anniversary of Russia’s further invasion of Ukraine, the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security in February 2023 announced significant expansions of the Russian and Belarusian Industry Sector Sanctions, including the addition of over 500 items, identified by Harmonized Tariff Schedule (“HTS”) codes, to lists of commercial, industrial, and luxury items that now require an export license for Russia or Belarus. The agency’s use of HTS codes—which are widely used around the globe for classifying goods—appears to have been driven by a policy interest in expanding the reach of U.S. export controls beyond the items identified on BIS’s Commerce Control List. Rather, BIS is now increasingly relying on a common tool (the HTS codes) that will allow for greater coordination and interoperability with restrictions put in place by allied and partner countries, while also enabling BIS to control exports of commercial items that, under U.S. regulations, are designated EAR99. After Iranian unmanned aerial vehicles (“UAVs”) appeared on the battlefield in Ukraine, in some cases with U.S.-branded parts and components, BIS also announced new controls on commercial items that are used in the production of UAVs when destined for Iran, Russia, Crimea, or Belarus. Notably, the new UAV-related controls reach foreign-made products when such items rely upon certain U.S.-origin software or technology through the application of a new Iran-related Foreign Direct Product Rule.

From May 2023 to January 2024, BIS added over 1,300 items to the list of electronics, industrial items, manufacturing equipment, and materials that require an export license to Russia or Belarus. As a result, under U.S. law, four entire chapters of the Harmonized Tariff Schedule are now subject to an export licensing requirement when goods identified in those chapters—including nuclear items (Chapter 84); electrical machinery and equipment (Chapter 85); aircraft, spacecraft, and parts thereof (Chapter 88); and optical, photographic, precision, medical, or surgical instruments (Chapter 90)—are destined for Russia or Belarus. These and other updates brought U.S. controls on commercial items into closer harmony with controls imposed by the European Union and the United Kingdom, which have generally imposed controls based on their equivalents to the HTS codes used by the United States. BIS also updated the list of jurisdictions that have implemented substantially similar export controls targeting Russia and Belarus to include Taiwan alongside 37 previously identified countries. This list exempts these partner jurisdictions from U.S. controls on commercial items.

New measures implemented by the European Union and the United Kingdom track the trends discussed above. For instance, the European Union’s twelfth Russia sanctions package imposed new export restrictions on dual-use items, advanced technology, and industrial goods worth €2.3 billion per year. The European Union also expanded the scope of existing export restrictions to include a prohibition on the sale, license, or transfer of intellectual property rights and trade secrets relating to several categories of goods or technology, and bolstered transit restrictions—a novel kind of export control which the United States has yet to impose. Over the course of 2023, the United Kingdom also broadened the range of goods subject to trade sanctions through various amendments to primary legislation.

In light of these expanded controls targeting Russia, divestiture transactions continue to raise thorny issues. Companies headquartered virtually anywhere in the world that desire to divest their Russian operations must now consider whether such divestment would result in the transfer of U.S.-controlled items to end users in Russia. Increasingly, such transfers trigger an export licensing requirement, including for dual-use and commercial items. Accordingly, in furtherance of the U.S. Government’s policy of enabling companies to exit the Russian and Belarusian markets, BIS announced a case-by-case license review policy for license applications submitted by companies that are curtailing or closing all operations in Russia or Belarus and are headquartered outside of Country Groups D:1, D:5, E:1, or E:2 (i.e., certain jurisdictions that present heightened national security concerns, are subject to a United Nations (“UN”) or U.S. arms embargo, and/or are subject to a U.S. trade embargo). The European Union has introduced similar new grounds on which national competent authorities may authorize the sale, supply, or transfer of listed goods and technology, along with associated intellectual property, in the context of transactions that are strictly necessary for divestment from Russia or the wind-down of business activities in Russia. Parallel provisions have been implemented by the United Kingdom and fleshed out in published guidance.

In addition to these regulatory changes, BIS maintained a heavy focus on Russia-related enforcement. As discussed in more detail below, in 2023 the agency’s Office of Export Enforcement had a banner year, including the launch of the Disruptive Technology Strike Force in partnership with the U.S. Department of Justice (“DOJ”) to bring criminal enforcement actions against individuals and entities that circumvent export controls on Russia, China, and Iran. In some cases, criminal enforcement actions by DOJ were accompanied by the addition of Russia-related parties to the Entity List. In 2023, BIS added well over 100 new entities to the Entity List under the destination of Russia alone, as well as many other entities located around the world, including in allied and partner countries, for allegedly supplying Russia’s defense sector with U.S.-origin goods, including semiconductors, electronics, and aviation equipment.

In addition to imposing new sanctions and export controls, the United States and its allies devoted considerable resources to shoring up existing trade restrictions on Russia by working to limit opportunities for evasion. Such efforts involved a high degree of interagency and international coordination, including the provision of substantial external guidance designed to better equip the private sector to detect, prevent, and report on Russian attempts to circumvent U.S. and allied trade controls. These multi-jurisdictional, joint guidance documents often emphasized practical sets of “red flags” to help identify evasion efforts and articulated heightened due diligence and compliance expectations by U.S. and allied regulators, especially when transactions involve certain high-priority items with potential military applications. Taken together, these joint notices, which were once rare, suggest that coalition sanctions and export controls authorities remain hyper-vigilant for potential Russia-related trade controls violations, and Russian circumvention and evasion will likely remain a top global priority for enforcement actions going forward.

1. Interagency Collaboration

Within the United States, a constellation of federal agencies sought to undercut Russian sanctions and export control evasion by issuing a series of joint guidance documents. Like the multi-jurisdictional notices discussed above, these multi-agency releases were also historically rare, often undercut by bureaucratic challenges which appear to have subsided. In 2023, these joint agency advisories included:

- BIS, OFAC, and DOJ (March 2023): Three U.S. Government agencies in March 2023 issued a joint compliance note detailing common ways in which malign actors have sought to circumvent U.S. sanctions and export controls, identifying key indicators a transaction party may be seeking to evade U.S. trade controls, and highlighting recent civil and criminal enforcement actions.

- BIS and FinCEN (May 2023): Building on a first-of-its-kind joint alert published the prior year by BIS and the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (“FinCEN”), those same two agencies in May 2023 issued a supplemental export control evasion alert that established a new Suspicious Activity Report (“SAR”) key term for financial institutions to use when reporting possible attempts to evade U.S. export controls on Russia (“FIN-2022-RUSSIABIS”) and describes evasion typologies and “red flags.” The introduction of a dedicated key term is designed to allow U.S. authorities to, within the enormous volume of SARs that FinCEN receives each year, quickly identify possible instances of Russia-related evasion.

- BIS and FinCEN (November 2023): BIS and FinCEN in November 2023 issued a further joint notice that expands upon the two agencies’ Russia-related export control guidance to target export control evasion worldwide. The November joint notice announced the creation of a second new Suspicious Activity Report key term (“FIN-2023-GLOBALEXPORT”) that financial institutions can use to report transactions that potentially involve evasion of U.S. export controls globally (excluding Russia which, as noted above, has its own unique key term), and provides an expansive list of “red flag” indicators of potential evasion.

- BIS, OFAC, DOJ, State, and Homeland Security (December 2023): In the broadest yet example of multi-agency guidance, in December 2023 five U.S. Government agencies issued a public advisory concerning sanctions and export control evasion in the maritime transportation industry. In that document, U.S. authorities indicate that maritime actors are expected to “know your cargo,” highlight tactics employed by bad actors to facilitate the illegal transfer of cargo, and note maritime industry-specific “red flags” such as ship-to-ship transfers and unusual shipping routes.

While the U.S. agencies described above have closely collaborated since the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, the volume of joint guidance and the extent of cooperation between sister agencies this past year were unprecedented and suggest that going forward the United States is likely to further break down silos between international trade disciplines in favor of a whole-of-government approach to countering sanctions and export control evasion. Although enhanced enforcement will impose even greater risks on the private sector, the collaboration between agencies will hopefully portend a more unified approach which could make compliance more straightforward.

2. International Collaboration

Beyond collaborations within the U.S. Government, the United States and its allies and partners joined together over the past year to limit Russian sanctions and export control evasion. Notable multilateral guidance focused on Russian circumvention included:

- REPO Task Force (March 2023): Established within days of the Kremlin’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Russian Elites, Proxies, and Oligarchs (“REPO”) Task Force is an information-sharing partnership of allied finance and justice ministries designed to promote joint action on sanctions, asset freezing, asset seizure, and criminal prosecution. In March 2023, the REPO Task Force issued a global advisory that identifies Russian sanctions evasion typologies, including conducting dealings through family members and close associates, using real estate to conceal ill-gotten gains, and accessing the international financial system through enablers such as lawyers, accountants, and trust service providers.

- Five Eyes (September 2023): The longstanding intelligence-sharing partnership known as the Five Eyes—comprising Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States—in June 2023 committed to extend their cooperation to include coordinating on export control enforcement. In September 2023, the Five Eyes followed through on that commitment by publishing joint guidance for industry and academia identifying certain high-priority items such as integrated circuits and other electronic components, organized by Harmonized System (“HS”) code, that present heightened risk of being diverted to Russia for use on the battlefield in Ukraine.

- United States, European Union, United Kingdom, and Japan (May to October 2023): In parallel with efforts by the Five Eyes, the United States, the European Union, the United Kingdom, and Japan published and periodically updated a common list of high-priority items that, as of this writing, identifies by HS code 45 items deemed especially high risk for diversion due to their potential use in Russian weapons systems. By widely disseminating a uniform list of items, coalition members sought to align controls across jurisdictions and concentrate finite compliance resources on a subset of items considered crucial to the Russian war effort.

3. Key Red Flags

The joint notices, alerts, and guidance described above each offer practical guidance to the private sector on detecting potential Russian evasion and circumvention, including identifying techniques commonly used to conceal the end user, final destination, or funding source for a transaction. Although those documents are designed for different audiences and each contain a subtly different set of recommendations, several common “red flags” for Russian sanctions and export control evasion recur across nearly all the multiagency and multilateral guidance issued in 2023 and include:

- Use of complex or opaque corporate structures to obscure ownership, source of funds, or countries involved;

- Reluctance by parties to provide requested information, including the names of transaction counterparties, beneficial ownership details, or written end-user certifications; and

- Transaction-level inconsistencies such as publicly available information regarding the counterparty (e.g., address, website, phone number, line of business) that appears at odds with an item’s purported use or destination. In part, this guidance seeks to address the ever-growing challenge of transshipment and diversion in which legal exports to a third country wind up being reexported to Russia or other jurisdictions of concern.

A further recurring theme of guidance issued over the past year is the importance of private sector cooperation to the success of U.S. and allied trade controls on Russia, and heightened expectations on the part of U.S. and allied regulators concerning private sector compliance. Many of these notices reiterate the expectation that private actors adopt risk-based compliance measures, including management commitment, risk assessments, internal controls, testing and auditing, training, empowering staff to report potential violations, and seeking written compliance certifications for higher-risk exports.

As part of a broader effort to limit sanctions and export control evasion, the United States in an unprecedented escalation of pressure on Moscow authorized secondary sanctions on foreign financial institutions that, knowingly or unknowingly, facilitate significant transactions involving Russia’s military-industrial base. These new restrictive measures are noteworthy not simply because they create new secondary sanctions risks for foreign banks and other financial institutions, but also because they expose these financial institutions to such risks based on the facilitation of trade in certain enumerated goods, and do so under a standard of strict liability (i.e., without requiring any culpable mental state such as knowledge). In short, these restrictions do what many had long thought to be coming—place broader export control compliance obligations on financial institutions.

Under certain U.S. sanctions programs—namely, those targeting Iran, North Korea, Russia, Syria, and Hong Kong—persons outside of U.S. jurisdiction that engage in enumerated transactions with certain targeted persons or sectors, including transactions with no ostensible U.S. nexus, risk becoming subject to U.S. secondary sanctions. Such measures target certain significant transactions involving, for example, Iranian port operators, shipping, and shipbuilding. In practice, secondary sanctions are highly discretionary in nature and principally designed to prevent non-U.S. persons from engaging in certain specified transactions that are prohibited to U.S. persons. If OFAC determines that a non-U.S. person has engaged in such transactions, the agency may impose punitive measures on the non-U.S. person which vary from the relatively innocuous (e.g., blocking use of the U.S. Export-Import Bank) to the severe (e.g., blocking use of the U.S. financial system or blocking all property interests). Until December 2023, non-U.S. persons only potentially risked secondary sanctions exposure, under the small handful of sanctions programs that include such measures, for knowingly engaging in certain significant transactions.

As we discuss in a prior client alert, the Biden administration on December 22, 2023 issued Executive Order 14114 and related guidance authorizing OFAC to impose secondary sanctions on foreign financial institutions that are deemed to have:

- Conducted or facilitated a significant transaction involving any person designated an SDN for operating in Russia’s technology, defense and related materiel, construction, aerospace, or manufacturing sectors, or any other sector that may subsequently be determined by the U.S. Secretary of the Treasury (such persons, “Covered Persons“); or

- Conducted or facilitated a significant transaction, or provided any service, involving Russia’s military-industrial base, including the direct or indirect sale, supply, or transfer to Russia of specified items such as certain machine tools, semiconductor manufacturing equipment, electronic test equipment, propellants and their precursors, lubricants and lubricant additives, bearings, advanced optical systems, and navigation instruments (such items, “Covered Items“).

Upon a determination by the Secretary of the Treasury that a foreign financial institution has engaged in one or more of the sanctionable transactions described above, OFAC can (1) impose full blocking measures on the institution or (2) prohibit the opening of, or prohibit or impose strict conditions on the maintenance of, correspondent accounts or payable-through accounts in the United States. Such measures are a potentially powerful deterrent to engaging in dealings involving Covered Persons or Covered Items as the potential consequence of such a transaction (i.e., imposition of blocking sanctions or loss of access to the U.S. financial system) is tantamount to a death sentence for a globally connected bank.

Critically, these new Russia-related secondary sanctions do not require that a foreign financial institution knowingly engage in such a transaction. This departs from the language that OFAC has historically used when crafting thresholds needed for the imposition of secondary sanctions. Provided that OFAC’s traditional multi-factor test for whether a transaction is “significant” is met, the prospect of strict liability secondary sanctions risk—which is entirely new in U.S. sanctions—will undoubtedly alter the diligence and risk calculus for financial institutions that may still be dealing in legally permitted Russia-related trade.

Compounding the potential compliance challenges for foreign financial institutions, E.O. 14114 appears to create an extraterritorial U.S. export control-like regime in the guise of secondary sanctions. Financial institutions, including foreign financial institutions, are already subject to a certain degree of compliance obligations under U.S. export control laws when it comes to knowingly facilitating prohibited trade in items that are subject to U.S. export controls. However, with the issuance of E.O. 14114, these entities now risk losing access to the U.S. financial system for even inadvertently engaging in a transaction involving Covered Items—regardless whether such items are subject to a U.S. export licensing requirement—destined for Russia.

E.O. 14114 will likely cause many foreign financial institutions to reexamine their risk appetite and related controls when it comes to trade-related activity involving Russia. As a practical matter, many foreign banks, confronted with the prospect of U.S. secondary sanctions exposure and the considerable due diligence challenge of assessing whether a particular transaction might implicate Russia’s military-industrial base, may end up erring on the side of overcompliance by declining to engage in otherwise lawful dealings involving Russia.

Consistent with a whole-of-government approach to limiting Russian revenue, the United States, the European Union, and the United Kingdom expanded prohibitions on the importation into their respective territories of certain Russian-origin goods—principally consisting of items closely associated with Russia or that otherwise have the potential to generate hard currency for the Kremlin.

During the initial year of the war in Ukraine, the Biden administration used this particular policy tool to bar imports into the United States of certain energy products of Russian Federation origin, namely crude oil, petroleum, petroleum fuels, oils, and products of their distillation, liquified natural gas, coal, and coal products; followed by fish, seafood, alcoholic beverages, non-industrial diamonds; and eventually gold. As with other Russia-related sanctions authorities, the Secretary of the Treasury has broad discretion under Executive Order 14068 to, at some later date, extend the U.S. import ban to additional Russian-origin goods.

The United States initially excluded from its import bans Russian-origin goods that have been incorporated or substantially transformed (i.e., fundamentally changed in form, appearance, nature, or character) into another product in a third country. However, in December 2023, in tandem with the new Russia-related secondary sanctions described above, President Biden amended Executive Order 14068 to authorize the Secretary of the Treasury to prohibit the importation into the United States of certain products that have been mined, extracted, produced, or manufactured wholly or in part in the Russian Federation, or harvested in waters under the jurisdiction of the Russian Federation or by Russia-flagged vessels, regardless whether such specified products have been incorporated or substantially transformed into other products outside of Russia. Acting pursuant to this authority, OFAC issued a determination barring the importation into the United States of foreign-made goods that contain any amount of Russian-origin salmon, cod, pollock, or crab, and indicated that a similar prohibition on importing certain Russian diamonds processed in third countries is expected to follow soon. Similarly, the European Union and the United Kingdom adopted an import ban on iron and steel products processed in a third country using Russian iron or steel products. Such enhanced import prohibitions on a narrow subset of products (i.e., certain fish, certain diamonds, iron and steel products) will likely present considerable practical challenges—similar to the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act with respect to goods linked to China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region—for importers who may now be required to demonstrate that their supply chains do not, directly or indirectly, trace back to Russia.

The European Union and the United Kingdom during 2023 also expanded the range of Russian goods subject to more traditional import prohibitions. Notable additions include diamonds and various metals, delivering a further blow to the Kremlin’s ability to finance its war in Ukraine and other destabilizing activities globally.

H. Possible Further Trade Controls on Russia

Leading democracies in 2023 continued to expand the dizzying array of trade restrictions imposed on Russia. While the coalition has not yet exhausted its policy toolkit, barring dramatic developments on the ground, the coming year appears likely to be defined by a further tightening of restrictions on Moscow.

Policymakers in Washington, London, and other allied capitals appear poised to continue aggressively blacklisting third-country sanctions and export controls evaders. To stanch the flow of sensitive components to the Russian military, the coalition may further expand its common list of high-priority items to subject additional goods to heightened scrutiny. The United States could also leverage its new Executive Order 14114 to secondarily sanction one or more foreign financial institutions—severing their access to mainstream finance—as a warning to other banks considering engaging with Russia’s military-industrial base.

More severe measures—such as blocking sanctions on the Government of the Russian Federation or conceivably a complete embargo on Russia like the U.S. measures that presently apply to Cuba, Iran, North Korea, Syria, and certain Russian-occupied regions of Ukraine—also remain available. However, in light of wavering political support for Kiev in some allied capitals, a seeming stalemate on the battlefield, and the imperative of maintaining stable energy prices, such restrictions appear unlikely to be imposed in the near term absent a complete breakdown in relations with Moscow.

II. U.S. Trade Controls on China

Despite the continuing challenge posed by Russia, the year in trade was largely defined by the deepening economic, technological, and security rivalry between the United States and China. Following a year marked by high tensions over Taiwan and a near-total breakdown in communications, relations between Washington and Beijing gradually stabilized in 2023, culminating in a long-awaited summit at which President Biden and China’s President Xi Jinping pledged to responsibly manage competition between the two superpowers.

That brief moment notwithstanding, U.S. officials from across the political spectrum continue to view China—with its rapidly advancing military and technological capabilities, state-led economy, and troubling human rights record—as the “pacing challenge” for U.S. national security. To meet that perceived threat, the United States during 2023 again pushed the limits of economic statecraft by expanding export controls on semiconductors and supercomputers, vigorously enforcing import prohibitions on goods linked to forced labor, heavily subsidizing domestic manufacturing, scrutinizing inbound Chinese investments, and for the first time ever putting into place a system that will restrict outbound investments into certain sensitive technologies. With U.S. elections in November 2024 and bipartisan consensus on the perceived strategic threat that China poses to the United States and its allies, the pace of new trade controls on China seems unlikely to slow any time soon. One of the only questions is whether Congress or the Executive will take the lead.

Despite a mild thawing in U.S.-China relations following the November 2023 summit between Presidents Biden and Xi, controlling the manufacture and supply of certain advanced technologies remained a core feature of U.S. trade policy toward Beijing. During 2023, the United States aggressively employed a range of export control measures to slow China’s technological development, including further restricting exports of certain advanced semiconductors and supercomputers, adding over 100 Chinese organizations to BIS’s Entity List, and using the threat of further additions to the Entity List to incentivize Chinese firms (and the Chinese government) to permit timely end-use checks on authorized exports.

1. Expanded Controls on Semiconductors and Supercomputers

On October 17, 2023, the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security announced two new interim final rules updating and expanding certain export controls targeting advanced computing integrated circuits (“Advanced ICs”), computer commodities that contain such Advanced ICs, and certain semiconductor manufacturing equipment (“SME”). These two interim final rules build upon the groundbreaking and extensive unilateral controls implemented by the United States in October 2022. Detailed descriptions of the original and expanded controls can be found in our client alerts published in October 2022, February 2023, and October 2023.

The October 2023 interim final rules are designed to strengthen, expand, and reinforce the original October 2022 rules, which curtailed China’s ability to purchase and manufacture Advanced ICs for use in advanced weapon systems and other military applications of artificial intelligence (“AI”), products that enable mass surveillance, and other technologies used in the abuse of human rights. Broadly speaking, the new interim final rules impose controls on additional types of SME, refine the restrictions on U.S. persons to ensure U.S. companies cannot provide support to advanced SME in China, expand license requirements for the export of SME to apply to additional countries, adjust the licensing requirement criteria for Advanced ICs, and impose new measures to address risks of circumvention of the controls by expanding them to additional destinations.

Perhaps the most significant development in the new interim final rules is the expansion of certain controls to destinations beyond China (including the Hong Kong special administrative region) and the Macau special administrative region. Namely, the interim final rule on advanced computing items and supercomputer and semiconductor end uses expands the previous controls to 21 other destinations for which the United States maintains an arms embargo (i.e., so-called Country Group D:5 countries) and revises a previously imposed foreign direct product rule targeting non-U.S.-origin products used in advanced computing and supercomputers to apply to these same Country Group D:5 destinations. Similarly, the interim final rule on SME items expands the relevant controls to an additional 44 destinations (i.e., all destinations specified in Country Groups D:1, D:4, and D:5, excluding Cyprus and Israel). The expanded destination scope of these rules is intended to account for the possibility that counterparties located in these jurisdictions might try to obtain these highly controlled items for end users in other destinations and to apply the prohibitions to the longer list of countries that the United Nations and the United States have identified as posing heightened risks.

Apart from expanding the territorial application of the previous rules, the two interim final rules similarly refine the item-specific Export Control Classification Numbers (“ECCNs”) subject to the heightened controls. BIS abandoned the previous ECCN 3B090 introduced in the October 2022 version of the regulations and instead determined that identifying specific SME for control in ECCNs 3B001 and 3B002 represents a more manageable arrangement. BIS also refined the Advanced ICs captured under existing controls by adding a new “performance density” parameter to prevent users from purchasing and combining a large number of smaller datacenter AI chips to equal the computing power of more powerful chips already restricted under the previous controls. And BIS added new “.z” paragraphs to ECCNs 3A001, 4A003, 4A004, 4A005, 5A002, 5A004, 5A992, 5D002, and 5D992 to enable exporters to more easily identify products that incorporate Advanced ICs and items used for supercomputers and semiconductor manufacturing that meet or exceed the newly refined performance parameters.

Some of the most far-reaching restrictions contained in the October 2022 controls are the restrictions BIS placed on U.S. person support for the development and production of Advanced ICs and SME in specified jurisdictions, even when such activities did not involve items subject to the U.S. Export Administration Regulations (“EAR”). In the interim final rules, BIS both clarified and expanded these prohibitions, while codifying some of the guidance previously provided in the agency’s October 2022 Frequently Asked Questions. Specifically, BIS broadened these controls to extend to U.S. person support for development or production of Advanced ICs and SME at any facility of an entity headquartered in, or whose ultimate parent company is headquartered in, either Macau or a country subject to a U.S. arms embargo where the production of Advanced ICs occurs (i.e., Country Group D:5 countries). At the same time, BIS clarified that its facility-focused support prohibition is intended to include facilities engaged in all phases of production, including where important late-stage product engineering or early-stage manufacturing steps, among others, may occur. However, BIS narrowed its facility-based prohibition in one important respect, by limiting the scope of the restrictions to exclude “back-end” production steps such as assembly, testing, or packaging steps that do not alter the technology level of an Advanced IC. Importantly, BIS also added an exclusion to the new restrictions for U.S. persons employed or working on behalf of a company headquartered in the United States or a closely allied country (i.e., destinations specified in Country Group A:5 or A:6) and not majority owned by an entity that is headquartered in Macau or a destination specified in Country Group D:5.

In conjunction with BIS’s expanded destination and item-based licensing requirements, BIS issued two new temporary general licenses, valid through the end of 2025, that authorize companies headquartered in the United States and closely allied countries to continue shipping less sensitive items to certain facilities in Country Group D:1, D:4, and D:5 locations. These authorizations appear to be driven by a U.S. policy interest in enabling such companies to continue using facilities located in a restricted destination to perform more limited manufacturing tasks such as assembly, inspection, testing, quality assurance, and distribution in order to allow additional time for Advanced IC and SME producers located in the United States and closely allied countries to identify alternative supply chains outside of these more-restricted destinations.

BIS also created a new license exception—Notified Advanced Computing (“NAC”)—that authorizes exports of certain less-powerful Advanced ICs and associated items to Country Group D:1, D:4, and D:5 destinations. For items ultimately intended for Macau or a destination specified in Country Group D:5, advanced notice and approval from BIS is required, a process that enables BIS to monitor and track which end users are seeking these Advanced ICs and for what purpose. In particular, at least 25 days prior to any export or reexport to Macau or a destination specified in Country Group D:5, an application must be submitted via BIS’s Simplified Network Application Process Redesign (“SNAP-R”) system. BIS will review any such applications and render a decision within the allotted 25 days as to whether the use of License Exception NAC is permitted. The export must also be made pursuant to a written purchase order, unless the export is for commercial samples, and cannot involve any prohibited end users or end uses (including “military end users” or “military end uses,” as defined in the EAR). Exporters are also required to report their use of License Exception NAC in their export clearance filings (i.e., electronic export information, or EEI, filings).

Although the two new interim final rules provide much-needed guidance, they also make it evident that BIS has high expectations for the private sector to be at the forefront of handling complex due diligence. Given the need to review multiple information sources, even including a counterparty’s aspirational development or production of technology, this type of screening is especially difficult to automate, and companies with relevant products will need to expend more compliance resources to fully address BIS’s heightened diligence expectations.

In December 2023, BIS released limited guidance concerning the application of these new interim final rules, including the process for calculating “performance density” used to determine the threshold for Advanced ICs, the information needed for the use of License Exception NAC, the scope of the new temporary general licenses, and clarifications on the new exclusions from prohibited U.S. person activities. However, based upon the number and variety of requests for public comment included in the two interim final rules, further refinements and possible future expansions of these controls appear likely. BIS specifically requested public comments on a number of issues implicated by the interim final rules, including the impact of potential controls on datacenter infrastructure-as-a-service offerings for AI training and suggestions for further refining technical parameters to distinguish Advanced ICs and computers commonly used for small- or medium-scale training of AI foundational models from those used for large AI foundational models with different capabilities of concern.

Apart from the imposition of new unilateral controls, the Biden administration continues to engage in extensive diplomatic efforts to encourage closely allied countries to adopt similar controls on chip-making equipment. In advance of any nascent multilateral regimes, the new export controls imposed by the United States reflect an effort to minimize some of the known collateral impacts that current unilateral controls could have on international trade flows, especially on the Advanced IC and SME supply chains of U.S. and allied country companies, and to encourage a collective “friend-shoring” of U.S. and allied country supply chains for critical technologies. To what extent such efforts will hinder or help the development of additional multilateral controls remains to be seen, though recent actions by the Japanese and Dutch governments to implement limited though still meaningful controls on Advanced ICs and SME supply chains indicate some initial success in the United States’ efforts to expand the new controls across multiple jurisdictions.

2. China-Related Entity List and Military End-User List Designations and Removals

In addition to novel measures such as stringent controls on semiconductors and supercomputers, the Biden administration over the last several years has used traditional export controls such as the Entity List to target China-based organizations. As noted in our 2022 Year-End Sanctions and Export Controls Update, the expanding size, scope, and profile of the Entity List now rivals OFAC’s SDN List as a tool of first resort when U.S. policymakers seek to exert strategic pressure, especially against significant economic actors in major economies. 2023 saw a solidification of this trend. The United States made extensive use of the Entity List throughout the past year, designating over 150 Chinese entities—more than double the number of Chinese entities added to the same list in 2022.

Entities can be designated to the Entity List upon a determination by the interagency End-User Review Committee (“ERC”)—which is composed of representatives of the U.S. Departments of Commerce, State, Defense, Energy and, where appropriate, the Treasury—that the entities pose a significant risk of involvement in activities contrary to the national security or foreign policy interests of the United States. Much like being added to the SDN List, the level of evidence needed to be included on the Entity List is minimal and far less than the “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard that U.S. courts use when assessing guilt or innocence. Despite this, the impact of being included on the Entity List can be catastrophic. Through Entity List designations, BIS prohibits the export of specified U.S.-origin items to designated entities without BIS licensing. With respect to potential licensing for Entity List exports, BIS will typically announce either a policy of denial or ad hoc evaluation of license requests. The practical impact of any Entity List designation varies in part on the scope of items BIS defines as subject to the new export licensing requirement, which could include all or only some items that are subject to the EAR. Those exporting to parties on the Entity List are also precluded from making use of any BIS license exceptions. However, because the Entity List prohibition applies only to exports of items that are “subject to the EAR,” even U.S. persons are still free to provide many kinds of services and to otherwise continue dealing with those designated in transactions that occur wholly outside of the United States and without items subject to the EAR. (This is one of the key ways in which the Entity List differs from the SDN List.)

The ERC has over the past several years steadily expanded the bases upon which companies and other organizations may be designated to the Entity List. In many cases over the past year, BIS turned to conventional reasons for designating Chinese entities such as their providing support for China’s military modernization efforts, attempting to divert or reexport goods to restricted parties, or enabling cybersecurity activities deemed threatening to U.S. national security. Other designations, however, relied on more specific justifications, often in response to current events, such as the designation of six Chinese entities in February 2023 for supporting the People’s Liberation Army’s “aerospace programs including airships and balloons and related materials and components” following public outcry over Chinese high-altitude balloons flying over North American airspace. More in line with designations from the past several years, the ERC in March 2023 added several entities to the Entity List for their alleged involvement in human rights violations such as high-tech surveillance of minority groups in China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. Other Chinese entities were designated in June 2023 for providing “cloud-based supercomputing capabilities” in support of hypersonics research conducted by China’s military, while an additional 13 entities were designated in October 2023 for their involvement with the development of Advanced ICs.

Notably, during 2023 no new Chinese entities were added to BIS’s non-exhaustive Military End-User (“MEU”) List, which was developed to help exporters determine which organizations in Belarus, Burma, Cambodia, China, Russia, or Venezuela are considered “military end users” for which an export license may be required. However, one previously designated entity, China-based Zhejiang Perfect New Material Co., Ltd, was removed from the MEU List in September 2023 following a request for removal submitted to BIS—suggesting that, although the process can be long and cumbersome for the targeted entity, BIS is still actively considering petitions for removal, even when such entities are located in sensitive jurisdictions.

3. China-Related Unverified List Designations and Removals

As in previous years, BIS made use of the Unverified List throughout the year to incentivize named entities to comply with robust end-use checks. A foreign person may be added to the Unverified List when BIS (or U.S. Government officials acting on BIS’s behalf) cannot verify that foreign person’s bona fides (i.e., legitimacy and reliability relating to the end use and end user of items subject to the EAR) in the context of a transaction involving items subject to the EAR. This situation may occur when BIS cannot satisfactorily complete an end-use check, such as a pre-license check or a post-shipment verification, for reasons outside of the U.S. Government’s control. Any exports, reexports, or in-country transfers to parties named on the Unverified List require the use of an Unverified List statement, and Unverified List parties are not eligible for license exceptions under the EAR that would otherwise be available to those parties but-for their designation to the list.

Notably, BIS in October 2022 implemented a new two-step process whereby companies that do not complete requested end-use checks within 60 days will be added to the Unverified List. If companies are added to the Unverified List due to the host country’s interference, after a subsequent 60 days of the end-use check not being completed, such companies will be moved from the Unverified List to the more restrictive Entity List. That process is designed to further incentivize targeted entities—and, at least in the case of China, their home governments—to permit BIS end-use checks to proceed in a timely manner as cooperative entities can be rewarded with removal from the Unverified List and uncooperative entities risk becoming subject to even more stringent controls.

This seemingly subtle policy change appeared to pay dividends during 2023 as a total of 32 entities from China were removed from the Unverified List in August and December 2023, and continuing in January 2024, after BIS was able to verify their bona fides through an end-use check—suggesting a willingness on the part of Chinese authorities to change their behavior to retain access to U.S.-origin items.

B. Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act

2023 marked the first full year of enforcement of the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (“UFLPA”). As we describe in a prior client alert, that groundbreaking law, which took effect in June 2022, establishes a rebuttable presumption that all goods mined, produced, or manufactured even partially within China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (“Xinjiang”), or by entities identified on the UFLPA Entity List, are the product of forced labor and are therefore barred from entry into the United States. After a year of active enforcement by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (“CBP”), recent calls from Congress to further strengthen and expand enforcement signal a continued focus on the UFLPA in the year ahead.

Despite criticisms that progress has been too slow, in 2023 the U.S. Government made notable additions both to CBP’s list of high-risk commodities for priority UFLPA enforcement, as well as to the UFLPA Entity List maintained by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (“DHS”). CBP’s release of a document attached to UFLPA detention notices confirmed an expansion of scrutiny from products previously identified as high-risk (i.e., tomatoes, cotton, polysilicon, polyvinyl chloride, and aluminum) to now include batteries, tires, and steel products. These newly added targets, which appear to have stemmed from private sector research published in late 2022 on possible links to Xinjiang in automotive supply chains, highlight continuing close coordination between DHS and the non-governmental and academic communities in identifying risks and specific parties of concern. Throughout 2023, the interagency Forced Labor Enforcement Task Force, led by DHS, also added 10 entities (and some of their subsidiaries) to the UFLPA Entity List. One of these entities, Ninestar Corporation, has since challenged its designation before the U.S. Court of International Trade, citing a lack of information provided by DHS regarding the reasons for its listing. The outcome of that case could have broader implications for the type and extent of information that agencies are required to provide to individuals and entities that are added to U.S. Government restricted party lists.

Notably, CBP sought to increase transparency regarding UFLPA enforcement, and published additional guidance to importers concerning the law’s broad standards and high bar for challenging potential detentions at U.S. ports. The launch of the UFLPA Statistics Dashboard on CBP’s website in March 2023 has provided key insights into the number, value, and type of shipments detained under the UFLPA to date. As of November 2023, over 6,000 shipments had been detained under the UFLPA, valued at more than $2.2 billion. Despite the UFLPA’s focus on and close association with China, the majority of goods detained to date have somewhat surprisingly originated from countries other than China, including Malaysia, Vietnam, and Thailand. This serves as an important reminder both of transshipment risk given today’s global supply chains and the critical role of Chinese materials in supply chains of companies throughout the world and especially in Southeast Asia.

CBP statistics further reveal that slightly more than half of all shipments detained to date under the UFLPA have ultimately been released into the United States. In light of the lack of reporting to Congress of any granted “exceptions” to the UFLPA’s rebuttable presumption, as required by the statute, these releases appear to all be the result of successful “applicability reviews.” CBP published guidance in February 2023 on the applicability review process, in which importers submit evidence that a given shipment is outside of the scope of the UFLPA altogether, and thus the rebuttable presumption does not apply (i.e., the goods are not mined, produced, or manufactured wholly or in part in Xinjiang or by an entity on the UFLPA Entity List). That guidance, which indicates importers must be able to submit evidence tracing their supply chains back to the raw materials, highlights the need for robust supply chain due diligence programs and the development of novel recordkeeping and contracting tools that enable buyers of goods to extend their supply chain tracing well beyond the first tier of suppliers. Although the UFLPA has its roots in Great Depression-era legislation that first restricted the importation into the United States of goods linked to forced labor, the UFLPA remains a relatively new human rights policy tool that appears ripe for further guidance and vigorous enforcement during the year ahead.

In a sea change from longstanding U.S. aversion to state industrial policy, the United States continued to embrace a protectionist-leaning “modern industrial and innovation strategy” to counteract China’s influence on the world stage. After the U.S. Congress adopted two massive legislative packages—the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 (the “CHIPS Act”) and the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (the “IRA”)—that direct billions of dollars toward boosting domestic manufacturing, in 2023 the Biden administration began implementing these laws by issuing multiple sets of regulations defining which parties are (and are not) potentially eligible to receive U.S. subsidies, in each case with an eye toward preventing taxpayer dollars from flowing to China.

The CHIPS Act provides over $50 billion in incentives for semiconductor manufacturers to invest in production capacity in the United States. Notably, those incentives can be clawed back if manufacturers violate so-called guardrails, mandated by Congress, barring certain investments in “countries of concern,” namely China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea. In September 2023, the U.S. Department of Commerce issued a final rule implementing the CHIPS Act national security guardrails. Among other things, the rule bars recipients of CHIPS Act funding, for 10 years from the date of award, from expanding production facilities in countries of concern by 10 percent or more for legacy chips, and by 5 percent or more for chips that are advanced or critical to U.S. national security. The rule also defines the categories of joint research and technology licensing that are prohibited under the CHIPS Act to include most activities involving entities owned or controlled by a country of concern, as well as entities identified on BIS’s Entity List and OFAC’s Non-SDN Chinese Military-Industrial Complex Companies (“NS-CMIC”) List. From a policy perspective, the CHIPS Act guardrails are designed to prevent taxpayer-funded incentives from accruing to the benefit of China’s semiconductor industry and, over time, shift the geography of semiconductor manufacturing activities away from China and toward the United States and other friendly jurisdictions.

In a parallel effort to relocate electric-vehicle (“EV”) supply chains from China to the United States, the Inflation Reduction Act includes billions of dollars in subsidies for EVs assembled in North America—a move that has rankled close U.S. allies in Europe who have criticized the measure as protectionist and discriminatory against European goods. Among other limitations, the IRA stipulates that, to be eligible for an up to $7,500 tax credit, an EV must undergo final assembly in North America, a certain percentage of the critical minerals in the vehicle’s battery must be extracted or processed in the United States or in a country with which the United States has a free trade agreement, and the vehicle’s battery cannot contain any components manufactured in certain countries of concern such as China. To assuage allied concerns regarding the IRA, the United States in March 2023 entered into a critical minerals agreement with Japan, and is presently negotiating similar agreements with the European Union and the United Kingdom, which could enable companies based in those jurisdictions to benefit from U.S. electric-vehicle subsidies. Meanwhile, the U.S. Department of the Treasury in December 2023 issued a notice of proposed rulemaking further defining which EVs are potentially ineligible for U.S. subsidies by virtue of their ties to China. These developments, taken together, suggest a willingness on the part of the Biden administration to implement and interpret the IRA in a manner that simultaneously advantages core U.S. allies and withholds benefits from Beijing.

In conjunction with export controls, the Biden administration, acting through the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (“CFIUS” or the “Committee”), continued to closely scrutinize acquisitions of, and investments in, U.S. businesses by Chinese investors. As discussed more fully in Section V.A, below, CFIUS appears to be especially focused on identifying non-notified transactions involving Chinese acquirors (i.e., transactions that have already been completed and which were not brought to CFIUS’s attention), including through use of the Committee’s increased monitoring and enforcement capabilities.

During calendar year 2022, the most recent period for which data is available, Chinese investors once again eschewed the CFIUS short-form declaration process, filing only 5 declarations and 36 notices. Those figures are generally consistent with the period from 2020 to 2022. This apparent preference of Chinese investors to forgo the short-form declaration in favor of the prima facie lengthier notice process may indicate a calculus that, amid U.S.-China geopolitical tensions, the likelihood of the Committee clearing a transaction involving a Chinese investor through the scaled-down declaration process is quite low.