The United States Becomes the Sixth Signatory to the 2019 Hague Judgments Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Judgments

Client Alert | March 18, 2022

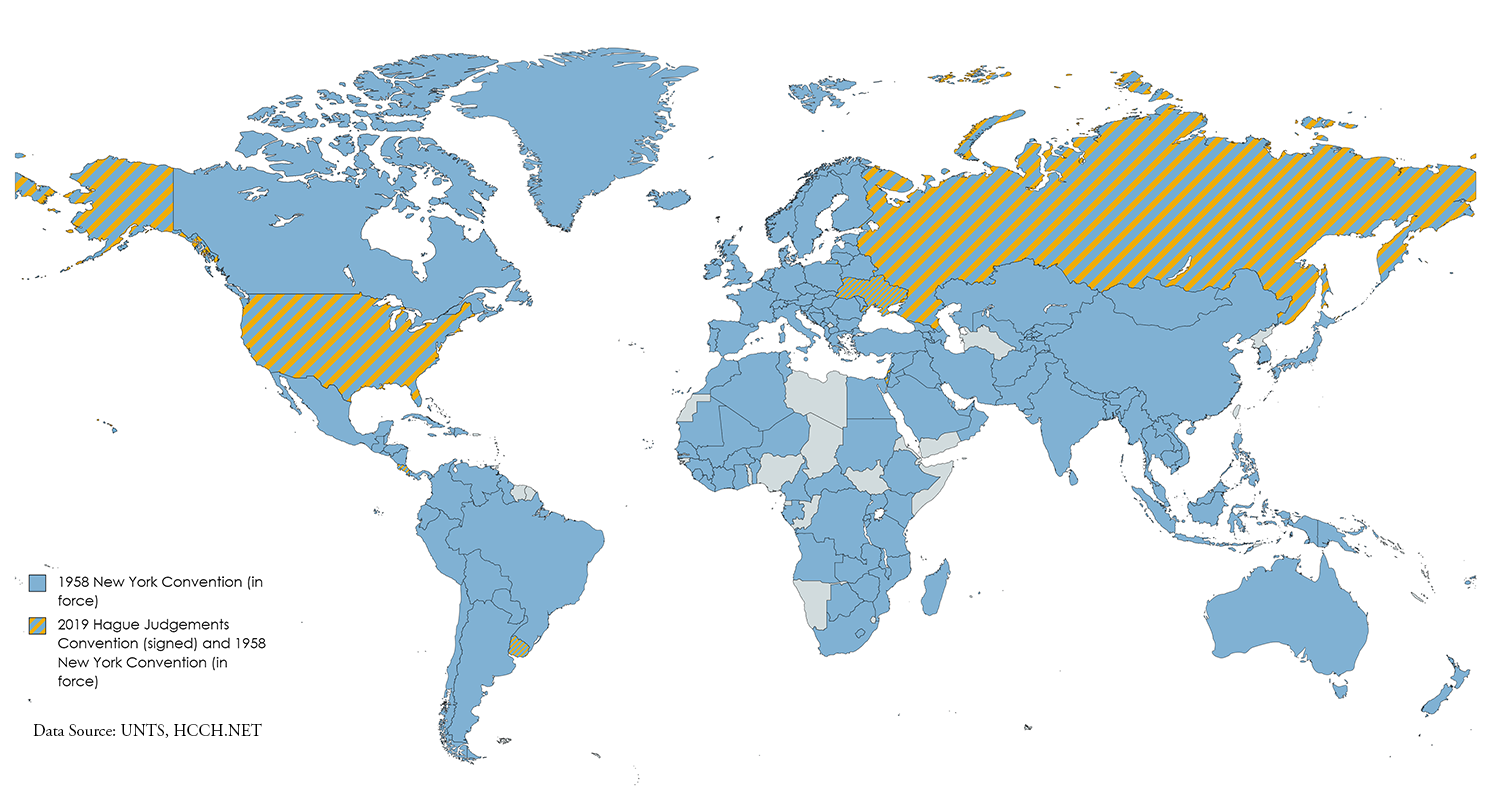

On 2 March 2022, the United States signed the Convention of 2 July 2019 on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Judgments in Civil or Commercial Matters (the “Hague Judgments Convention” or the “Convention”).[1] The Hague Judgments Convention seeks to enhance access to justice and facilitate international trade and investment by encouraging the free flow of judgments across national borders.[2] It does so by providing a set of clear, predictable rules under which civil and commercial judgments rendered by the courts of one Contracting State are recognized and enforced in other Contracting States. While not yet in force, the Hague Judgments Convention could provide an important complement to the widely adopted 1958 New York Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards[3] (the “New York Convention”) (which provides for the recognition and enforcement of arbitral awards), as well as its sister treaty, the 2005 Hague Choice of Court Convention.[4]

I. Recognition of Foreign Judgments in the United States

At present, there is no federal law that governs the recognition of foreign judgments in the United States, nor is there an international treaty in force. Rather, recognition and enforcement are a question of state law, although the rules are relatively consistent across all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia.[5] Most U.S. states have modeled their approaches to foreign judgment recognition on the model laws promulgated by the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws—the Uniform Foreign Money Judgments Recognition Act of 1962 (the “1962 Uniform Act”), or increasingly, the Uniform Foreign-Country Money Judgments Recognition Act of 2005 (the “2005 Uniform Act”).[6]

Generally, the United States favors recognition and enforcement of foreign judgments: in U.S. state and federal courts, foreign judgments are presumptively entitled to recognition and enforcement unless specific mandatory or discretionary grounds for non-recognition apply.[7]

II. The Hague Judgments Convention

The 2019 Hague Judgments Convention is the culmination of over 25 years of negotiations at the Hague Conference on Private International Law (the “Hague Conference”).[8] The process began in 1992 at the request of the United States, which sought to develop a global approach to jurisdiction and recognition of judgments.[9] The final text of the Hague Judgments Convention was eventually signed and opened for signature on 2 July 2019. Signatory States in addition to the United States include Uruguay, Ukraine, Israel, Costa Rica, and the Russian Federation (in order of signature).[10] The European Commission is also contemplating accession on behalf of the EU Member States.[11]

Recognition of Arbitral Awards under the New York Conventions and Foreign Judgments under the Hague Judgments Convention

The Convention will enter into force as soon as the second State deposits its instrument of ratification, acceptance, approval, or accession.[12] However, under Article 29 (the “bilateralization” clause), a Contracting State can prevent the application of the Convention to judgments rendered by the courts of a particular State by making a targeted declaration.[13]

The Convention applies to “the recognition and enforcement of judgments relating to civil or commercial matters.”[14] It specifically excludes subjects that are fundamental to State sovereignty or public policy (such as criminal, revenue, customs, or administrative matters),[15] as well as other specialized areas, some of which are subject to other treaty regimes or where the rules vary more significantly across jurisdictions (such as matters involving family disputes, intellectual property, antitrust, defamation, privacy, or armed forces matters).[16]

The Convention, like most domestic laws, favors recognition. It requires each Contracting State to recognize and enforce judgments from other Contracting States in accordance with its terms and permits refusal only on those grounds expressly set out in the Convention.[17]

Article 5(1) of the Convention sets out 13 “bases” of recognition and enforcement, including, inter alia, that:

- The judgment debtor is habitually resident in the foreign forum;

- The judgment debtor has their principal place of business in the foreign forum (and the claim on which the judgment is based arose out of the activities of that business);

- The judgment debtor expressly consented to the foreign court’s jurisdiction;

- The judgment debtor waived his jurisdictional objections by arguing on the merits in the forum state;

- The judgment ruled on a lease of immovable property (tenancy) and it was given by a court of the State in which the property is situated; or,

- The judgment ruled on a non-contractual obligation arising from death, physical injury, damage to or loss of tangible property, and the act or omission directly causing such harm occurred in the forum State, irrespective of where that harm occurred.

These bases for jurisdiction and enforcement echo the basic concepts found in domestic U.S. recognition and enforcement law,[18] including the constitutional due process requirements reflected in the notion of “minimum contacts” that U.S. courts require for the exercise of long-arm jurisdiction and the comity-based rules adopted by the U.S. Supreme Court in the seminal decision, Hilton v. Guyot, 159 U.S. 113 (1895).

If any of the jurisdictional tests (or “jurisdictional filters”[19]) in Article 5(1) is met, then the judgment is presumptively “eligible” for recognition and enforcement.[20] Under Article 15, national law provides a further independent basis for recognition.[21] In this sense, “the convention is a floor, not a ceiling.”[22]

Article 7 of the Convention, in turn, sets out discretionary bases for non-recognition, including, inter alia, the following:

- The defendant was not notified, or the manner of notification was incompatible with fundamental principles of service of documents in the forum State;

- The decision was obtained by fraud;

- Recognition or enforcement would be “manifestly incompatible” with the public policy of the recognizing State;

- The specific proceedings were incompatible with fundamental principles of procedural fairness of the recognizing State; or,

- The judgment is inconsistent with a judgment given by a court of the recognizing State in a dispute between the same parties.[23]

This too reflects the traditional non-recognition grounds found in most national legal systems, including that of the United States, such as inconsistency with the forum State’s public policy, due process violations, fraud, lack of notice or proper service, and conflict with other judgments.[24]

The Hague Judgments Convention is therefore in line with many precepts of existing U.S. recognition and enforcement law reflected in the 2005 Uniform Act.[25] However, the Convention covers not only foreign money judgments, but civil and commercial decisions generally.

III. Implications for the Recognition of Foreign Judgments in the United States

The Convention could be “a gamechanger for cross-border dispute settlement”[26] by providing a set of consistent rules for the recognition and enforcement of foreign judgments, much like the New York Convention has been for the widespread adoption of arbitral awards. Ultimately, a judgment in an international dispute is only as valuable as the judgment creditor’s ability to have it recognized and enforced abroad (where the judgment debtor or its assets may be found). However, making the enforcement of foreign judgments easier can be a double-edged sword. While a more robust and predictable enforcement regime can certainly be beneficial, that is only the case where the foreign court provides due process and a just outcome.

Ultimately, the force of the Hague Judgments Convention will depend on how widely it is signed and ratified. Following the U.S. signature, the Hague Judgments Convention will not automatically come into force in the United States. It must first undergo a ratification process in U.S. Congress, a procedure that can in some cases take several years. Ratification may be slower here due to the prevalence of state law (and absence of federal law) in this particular area.[27]

For U.S. litigants, if ultimately ratified by the United States, the Hague Judgments Convention could aid the recognition and enforcement of U.S. judgments in a wider range of countries, in particular in jurisdictions that may currently refuse recognition on reciprocity grounds (i.e., where a foreign court would not recognize a U.S. judgment unless convinced that its judgment would receive the same treatment by a U.S. court). Similarly, the Convention could facilitate the recognition and enforcement of foreign judgments issued by courts of other Contracting States in U.S. courts (of course subject to the above-mentioned non-recognition defenses). This would greatly increase the ability of both U.S. and non-U.S. litigants to obtain meaningful cross-border relief in transnational litigation.

Until the Hague Judgments Convention comes into force, global trade and investment will continue to be facilitated by alternative dispute resolution mechanisms, such as the New York Convention for arbitral awards, as discussed above, and the new Singapore Convention for international settlement agreements resulting from mediation.[28] Thus, for now, international arbitration awards remain more portable than foreign judgments (in addition to other advantages of international arbitration, like the selection of a neutral forum to avoid any “home court” advantage).[29]

___________________________

[1] Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Judgments in Civil or Commercial Matters, July 2, 2019, https://www.hcch.net/en/instruments/conventions/full-text/?cid=137 (hereinafter “Convention”) (last visited Mar. 18, 2022).

[2] See Hague Conference on Private International Law, Explanatory Note Providing Background on the Proposed Draft Text and Identifying Outstanding Issues, Prel. Doc. No 2, 3 (2016) (“[T]he future Convention is intended to pursue two goals: to enhance access to justice; [and] to facilitate cross-border trade and investment, by reducing costs and risks associated with cross-border dealings.”)

[3] Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards (hereinafter “New York Convention”), June 10, 1958, 21.3 U.S.T. 2517, 3 U.N.T.S. 330.

[4] Convention on Choice of Court Agreements, June 30, 2005, 44 I.L.M. 1294 (hereinafter “2005 Choice of Court Convention”).

[5] See Gibson Dunn, New York Updates Law on Recognition of Foreign Country Money Judgments to Bring in Line with Other U.S. Jurisdictions, June 22, 2021, https://www.gibsondunn.com/new-york-updates-law-on-recognition-of-foreign-country-money-judgments-bring-in-line-with-other-us-jurisdictions/.

[8] See generally Louise Ellen Teitz, Another Hague Judgments Convention? Bucking the Past to Provide for the Future, 29 Duke J. Comp. & Int’l L. 491 (2019) (reviewing the Convention’s negotiations history).

[9] See generally Ronald A. Brand, The Hague Judgments Convention in the United States: A “Game Changer” or a New Path to the Old Game?, 82 U. Pitt. L. Rev. 847 (2021).

[10] See Hague Conference on Private International Law, Status Table – Convention of 2 July 2019 on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Judgments in Civil or Commercial Matters, https://www.hcch.net/en/instruments/conventions/status-table/?cid=137 (last visited Mar. 18, 2022).

[11] European Commission, Proposal for a Council Decision on the Accession by the European Union to the Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Judgments in Civil or Commercial Matters, COM (2021) 388 (July 16, 2021), here (last visited Mar. 18, 2022) (recommending accession to the Convention so as to ensure the circulation of foreign judgments beyond the EU area and to increase “growth in international trade and foreign investment and the mobility of citizens around the world”).

[17] See id. at art. 4(1) (“A judgment given by a court of a Contracting State (State of origin) shall be recognised and enforced in another Contracting State (requested State) in accordance with the provisions of this Chapter. Recognition or enforcement may be refused only on the grounds specified in this Convention.”).

[18] See Gibson Dunn, New York Updates Law on Recognition of Foreign Country Money Judgments to Bring in Line with Other U.S. Jurisdictions, June 22, 2021, https://www.gibsondunn.com/new-york-updates-law-on-recognition-of-foreign-country-money-judgments-bring-in-line-with-other-us-jurisdictions/.

[19] See Brand, supra note 9, at 851.

[20] On the other hand, a judgment that ruled on rights in rem in immovable property “shall be recognised and enforced if and only if the property is situated in the State of origin.” Convention, art. 6.

[21] Convention, art. 15 (“Subject to Article 6, this Convention does not prevent the recognition or enforcement of judgments under national law.”)

[22] Teitz, supra note 8, at 503.

[24] See also 2005 Choice of Court Convention, art. 9 (setting forth grounds for non-recognition).

[25] See Gibson Dunn, New York Updates Law on Recognition of Foreign Country Money Judgments to Bring in Line with Other U.S. Jurisdictions, June 22, 2021, https://www.gibsondunn.com/new-york-updates-law-on-recognition-of-foreign-country-money-judgments-bring-in-line-with-other-us-jurisdictions/.

[26] Hague Conference on Private International Law, Gamechanger for Cross-Border Litigation in Civil and Commercial Matters to be Finalized in the Hague (June 18, 2019) (quoting the Secretary General of the Hague Conference), https://www.hcch.net/en/news-archive/details/?varevent=683 (last visited Mar. 18, 2022).

[27] The United States has been a member of the Hague Conference since 1964 and is currently a Contracting Party to seven Hague Conventions (Convention Abolishing the Requirement of Legalisation for Foreign Public Documents (“Apostille Convention”), Oct. 5, 1961, 527 U.N.T.S.; Convention on the Service Abroad of Judicial and Extrajudicial Documents in Civil or Commercial Matters (“Service Convention”), Nov. 15, 1965, 658 U.N.T.S. 163; Convention on the Taking of Evidence Abroad in Civil or Commercial Matters (“Evidence Convention”), Mar. 18, 1970, 847 U.N.T.S. 231; Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction (“Child Abduction Convention”), Oct. 25, 1980, 1343 U.N.T.S. 89; Convention on Protection of Children and Co-operation in respect of Intercountry Adoption (“Adoption Convention”), May 29, 1993, 1870 U.N.T.S. 167; Convention on the Law Applicable to Certain Rights in respect of Securities Held with an Intermediary (“Securities Convention”), July 5, 2006, 46 I.L.M. 649; Convention on the International Recovery of Child Support and Other Forms of Family Maintenance (“Child Support Convention”), Nov. 23, 2007, 47 I.L.M. 257. The U.S. has not yet ratified the 2005 Choice of Court Convention, often seen as the sister treaty to the Hague Judgments Convention.

[28] See generally United Nations Convention on International Settlement Agreements Resulting from Mediation, opened for signature Aug. 7, 2019 (adopted Dec. 20, 2018) (“Singapore Convention”), https://treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=XXII-4&chapter=22&clang=_en (last visited Mar. 18, 2022).

[29] For international commercial arbitration awards, the above map shows the broad reach of the New York Convention.

The following Gibson Dunn lawyers prepared this client alert: Rahim Moloo, Lindsey D. Schmidt, Maria L. Banda, and Nika Madyoon.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these issues. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, any member of the firm’s International Arbitration, Judgment and Arbitral Award Enforcement or Transnational Litigation practice groups, or the following:

Rahim Moloo – New York (+1 212-351-2413, rmoloo@gibsondunn.com)

Lindsey D. Schmidt – New York (+1 212-351-5395, lschmidt@gibsondunn.com)

Anne M. Champion – New York (+1 212-351-5361, achampion@gibsondunn.com)

Maria L. Banda – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3678, mbanda@gibsondunn.com)

Please also feel free to contact the following practice group leaders:

International Arbitration Group:

Cyrus Benson – London (+44 (0) 20 7071 4239, cbenson@gibsondunn.com)

Penny Madden QC – London (+44 (0) 20 7071 4226, pmadden@gibsondunn.com)

Judgment and Arbitral Award Enforcement Group:

Matthew D. McGill – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3680, mmcgill@gibsondunn.com)

Robert L. Weigel – New York (+1 212-351-3845, rweigel@gibsondunn.com)

Transnational Litigation Group:

Susy Bullock – London (+44 (0) 20 7071 4283, sbullock@gibsondunn.com)

Perlette Michèle Jura – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7121, pjura@gibsondunn.com)

Andrea E. Neuman – New York (+1 212-351-3883, aneuman@gibsondunn.com)

William E. Thomson – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7891, wthomson@gibsondunn.com)

© 2022 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.