February 12, 2019

Last January, we observed that the new administration had yet to upend pre-existing enforcement and regulatory trends in the pharmaceutical and medical device industries. But in the past 12 months several Trump administration priorities began to coalesce. From initiatives to address the opioid epidemic, to efforts to police patient assistance programs, to attempts to depress pharmaceutical prices, 2018 saw significant governmental attention to drug and device companies.

Not all of the administration’s attention is unwanted. Notably, there have been a few signs of scaled-back executive enforcement and regulatory activity impacting drug and device companies. For example, in December, the Department of Justice (“DOJ”) moved to dismiss nearly a dozen qui tam suits brought against pharmaceutical companies under the False Claims Act (“FCA”), carrying into action recent, well-publicized policy shifts at DOJ with regard to FCA actions. In moving to dismiss those suits, DOJ observed that the relator’s theories threatened to “undermine common industry practices [that] the federal government has determined are . . . appropriate and beneficial to federal healthcare programs and their beneficiaries.”[1] Meanwhile, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”) clearly has recalibrated its enforcement efforts with respect to promotional activities by drug and device companies. While Congress failed to make any significant progress toward implementing long-promised legislation regarding off-label promotion, FDA finally issued two pertinent guidance documents on that issue in June.

On the other hand, although financial recoveries from actions or investigations involving drug and device makers initiated by DOJ, the Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General (“HHS OIG”), and FDA started slowly in 2018, the latter half of the year saw several large settlements. DOJ employed aggressive law enforcement tactics to combat opioid abuse, targeting a range of individuals and entities. Notably, DOJ leveraged the FCA and the Anti-Kickback Statute to investigate and bring suits against opioid manufacturers and distributors. Further, DOJ did not pull any punches with respect to drug companies’ patient assistance programs. FDA enforcement actions relating to promotional activity remained relatively consistent with past years, focusing on only the most flagrant cases of deceptive advertising. But FDA continued to crack down on issues related to current good manufacturing practices and focused, in particular, on concerns with quality and data integrity issues. We anticipate that these 2018 priorities will continue to drive DOJ and FDA activity in 2019.

In the new year, we anticipate that the new majority in the House of Representatives will amp up the pressure on pharmaceutical companies, in particular. According to the House Committee on Oversight and Reform, the Committee already has “launched one of the most wide-ranging investigations in decades into the prescription drug industry’s pricing practices,” beginning with requests for detailed information and documents regarding pricing practices from 12 drug companies.[2] But other regulatory tea leaves for 2019 are more difficult to read because of the government shutdown, which forced FDA to furlough approximately 40% of its employees at the time. Although the agency publicly announced it would continue “vital activities . . . that are critical to ensuing public health and safety,” such as screening imported products, recalls, and pursuit of civil and criminal investigations where “public health is imminently at risk,” the shutdown halted FDA’s more routine enforcement actions and regulatory activity (e.g., issuing guidance documents) during that period.[3]

We address each of these important enforcement and regulatory developments in the drug and device space below, beginning with an overview of recent government enforcement efforts and FCA jurisprudence, then moving to relevant regulatory guidance and activity regarding promotional activities, manufacturing practices, and the AKS, and concluding with notable developments on drug pricing and for device manufacturers.

As always, we would welcome the opportunity to discuss the impact of these developments with you in more detail. Additional presentations and publications on regulatory and enforcement issues impacting drug and device makers are available on our website, including industry-specific webcasts with more in-depth discussions of the FCA and practical guidance to help companies avoid or limit legal exposure.

I. DOJ ENFORCEMENT IN THE PHARMACEUTICAL AND MEDICAL DEVICE INDUSTRIES

FCA resolutions delivered the bulk of financial recoveries against drug and device companies in 2018. DOJ also brought several federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (“FDCA”) enforcement actions, but Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (“FCPA”) activity in the drug and device space remained relatively quiet this past year.

As the new year progresses, we expect to see the continued impact of two memoranda on DOJ enforcement efforts issued last January by the then-Associate Attorney General, Rachel Brand, (the so-called “Brand Memo”) and the Director of DOJ’s Civil Division’s Fraud Section, Michael Granston (the “Granston Memo”). As we detailed in our client alert, DOJ Policy Statements Signal Changes in False Claims Act Enforcement, the Brand Memo bars DOJ attorneys from using guidance documents to “create binding requirements that do not already exist by statute or regulation,” and from using DOJ’s “enforcement authority to effectively convert agency guidance documents into binding rules.”[4] But the Brand Memo acknowledges that federal prosecutors may use such guidance as evidence of scienter (e.g., as proof that a defendant knew of obligations under the law).[5]

Many agencies, including FDA (in the off-label and quality and manufacturing space) and HHS OIG (in the application of the AKS), routinely issue guidance documents interpreting relevant legislation and regulations. DOJ historically relied on these guidance documents to bolster claims that the actions of a drug or device maker violated a particular statute or regulation and thus resulted in “false” claims under the FCA. Under the Brand Memo, DOJ will have to identify other means to support its allegations, and this may well constrain enforcement activity.

The Granston Memo directs government lawyers evaluating whether to decline to intervene in a qui tam FCA action to “consider whether the government’s interests are served” by dismissal of the underlying qui tam claims pursuant to 31 U.S.C. § 3730(c)(2)(A) based on seven enumerated factors.[6] DOJ’s rollout of an updated United States Attorneys’ Manual—now entitled the Justice Manual—builds on that initiative. Indeed, the Justice Manual appears to incorporate the Granston Memo’s rubric by encouraging government lawyers to evaluate a non-exhaustive list of factors (any one of which may support dismissal) when assessing whether to intervene.[7]

Taken together, these policy statements indicate that DOJ intends to hew more closely to constitutionally defined bounds for the executive branch and to employ more judicious enforcement of the FCA—both welcome developments for drug and device manufacturers. As detailed further below, DOJ sought to dismiss a dozen qui tam suits in this past year, thereby executing on the policies embodied by the Granston Memo and the revisions to the Justice Manual.

One additional DOJ policy development merits attention. In September 2015, then-Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates issued a memorandum (the so-called “Yates Memo”) stating that corporations must provide “all relevant facts” about individuals involved in misconduct.[8] Unlike the Granston Memo, which has had a quick impact on multiple qui tam suits, the Yates Memo had a less evident impact on drug and device companies. Nevertheless, the requirement that a company identify and provide evidence on all potentially culpable individuals struck many as a significant burden. In a speech in November 2018, Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein announced a fine-tuning of the Yates Memo’s requirements. Under the new DOJ policy, companies seeking cooperation credit must only identify individuals who were “substantially involved in or responsible for the criminal conduct” under investigation in white-collar investigations.[9]

A. False Claims Act

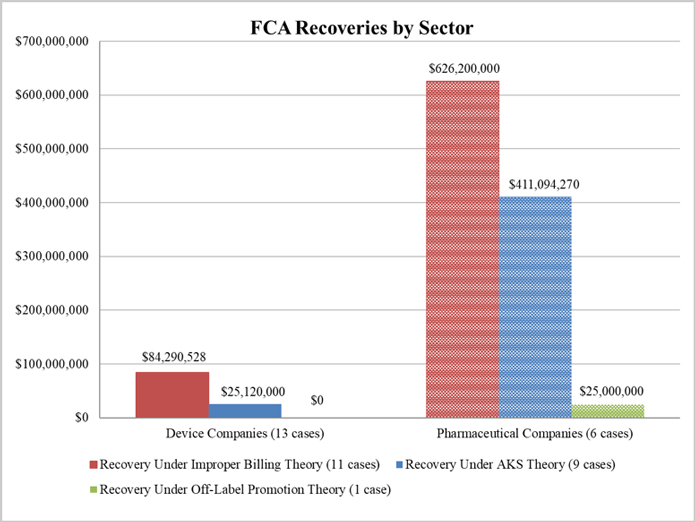

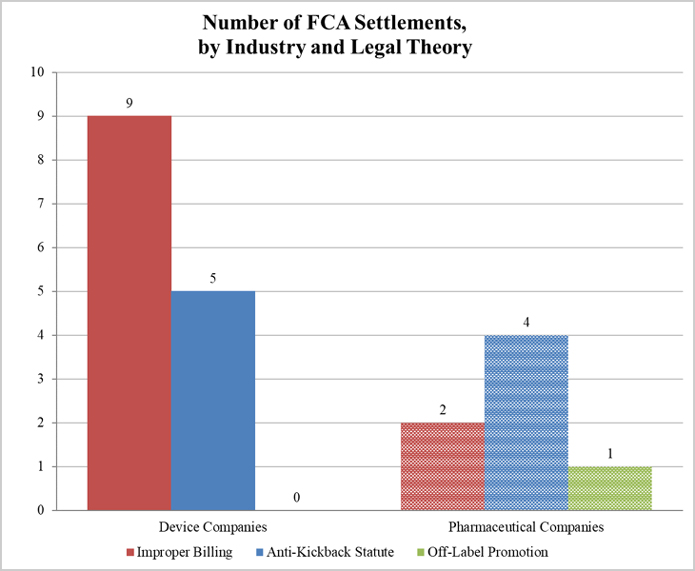

This year, DOJ recovered more than $1.1 billion from 19 FCA-related settlements with companies in the drug and device industries. Although DOJ’s civil recoveries through the first half of 2018 were less than a quarter of what they were at the same time last year, two large-scale settlements with pharmaceutical companies in the second half of the year pushed the total recoveries from resolutions with drug and device manufacturers closer to last year’s total of approximately $1.4 billion.

As illustrated below, DOJ settled 13 matters with device manufacturers (including two with AngioDynamics) and only six with pharmaceutical companies. Despite this disparity, the vast majority of DOJ’s settlement recoveries, roughly 90%, resulted from the investigations involving pharmaceutical companies. Recoveries in 2018 (like 2017) came almost exclusively from actions pursued under improper billing and AKS theories.[10]

1. Settlements in FCA Matters Relating to Patient Assistance Programs

The second largest settlement in 2018 resulted from a DOJ investigation into a pharmaceutical company’s financial ties to nonprofit patient assistance programs, which help needy patients access free or low-cost medications. Further, over the past year, a second pharmaceutical company disclosed a resolution tied to a similar investigation, and two other companies disclosed resolutions in principle. These resolutions follow United Therapeutics Corp.’s $210 million settlement in December 2017, discussed in our 2017 Year-End Update.

As we reported last year, government scrutiny of patient assistance programs is a relatively recent development in the enforcement arena. Companies have supported patient assistance programs directly and indirectly for years, and the government generally has approved of such arrangements. For example, in a Special Advisory Bulletin in 2005, HHS OIG explained that certain cost-sharing assistance through “bona fide, independent charities unaffiliated with pharmaceutical manufacturers should not raise [AKS] concerns, even if the charities receive manufacturer contributions.”[11] In recent years, however, HHS OIG has determined that aspects of patient assistance programs can be problematic and raise AKS concerns.[12] Carrying on the trend we observed in our 2017 Year-End Update, several of the settlements announced this year began with investigations launched by the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Massachusetts.

In December, DOJ announced its most recent resolution in this arena, which happens to be the largest to date. According to the government, Actelion Pharmaceuticals has agreed to pay $360 million to resolve claims that it used a charitable foundation to cover the copays of patients taking its pulmonary arterial hypertension drugs.[13] The government claimed that Actelion obtained data from the foundation regarding the payments the foundation made on behalf of patients taking the drugs and used that data to contribute amounts sufficient to cover the copays of only those patients, thereby purportedly violating the AKS.[14] The government further alleged that Actelion referred Medicare patients to the foundation rather than allowing them to participate in the company’s free drug program in order to generate revenue.[15]

The first half of the year saw several other similar matters reach the resolution stage:

- In May, Pfizer, Inc. announced it had agreed to pay $23.85 million to resolve allegations that it violated the AKS by paying patients’ copay obligations with funds purportedly channeled through a foundation.[16] According to the government, Pfizer donated money to the foundation for the purpose of covering copays for two of its drugs used to treat renal cell carcinoma, which could have been provided at no cost to patients who qualified for Pfizer’s existing free drug program.[17] The government claimed that paying patients’ copay obligations constituted remuneration designed to induce patients to use Pfizer’s drugs.[18] Further, according to the government, Pfizer worked with the foundation to create and finance a fund for patients suffering from the heart condition treated by its drug Tikosyn.[19] Pfizer allegedly referred patients to the fund and timed the creation of the fund to coincide with Pfizer’s increase in the price of the drug.[20] The government asserted that these actions allowed Pfizer to generate more revenue, while masking the effect of its price increases.[21]As part of the resolution, Pfizer entered into a five-year corporate integrity agreement (“CIA”) with HHS OIG, in which Pfizer agreed to ensure legally compliant interactions with third-party patient assistance programs.[22] Intended to “promote[] independence” between the company and any such programs to which it donates, the agreement requires review by an independent organization, compliance-rated certifications, and the implementation of a risk assessment and mitigation process.[23]

- Also in May, Dublin-based Jazz Pharmaceuticals PLC announced in an SEC filing that it had agreed in principle to pay $57 million to resolve similar allegations.[24] Neither Jazz nor the government has disclosed the government’s allegations in public sources, but the company’s SEC filings indicate that the allegations generally concern Jazz’s financial support of patient assistance nonprofits that help cover copays.[25] The company had not finalized the settlement with DOJ at the time of its most recent quarterly filing.[26]

- In early June, Denmark-based H. Lundbeck A/S announced that its U.S. subsidiary, Lundbeck LLC, had reached an agreement in principle with DOJ to pay $52.6 million to resolve DOJ’s investigation into the company’s ties to patient assistance charities.[27] Although the final terms of the agreement remain subject to negotiation and few details are publicly available,[28] Lundbeck previously disclosed that its subsidiary, Lundbeck NA Ltd., received a subpoena from the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Massachusetts in 2016, relating to its “payments to charitable organizations providing financial assistance to patients taking Lundbeck products” and to sales and marketing practices.[29]

These patient assistance investigations raise a host of legal and policy questions, ranging from the appropriate reach of the AKS to the impact on bona fide corporate charitable contributions to the First Amendment implications of the government’s theories. In light of these key questions, it came as no surprise that a charity, Patient Services Inc., filed a First Amendment lawsuit in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia in January challenging the constitutionality of HHS OIG’s restrictions on the charity’s communications with donors.[30] Despite the thorny legal and policy questions, it appears DOJ will continue pursuing claims tied to patient assistance programs.

2. Settlements in AKS-Related FCA Matters

In addition to its activity relating to patient assistance programs, DOJ reached a number of other notable AKS-related settlements in 2018.

In August, Insys Therapeutics reached an agreement in principle with the government to pay at least $150 million, and potentially an additional $75 million depending on certain events, to resolve a DOJ investigation into claims that the drug maker paid kickbacks to doctors to induce them to prescribe Subsys, an opioid medication.[31] According to the government’s complaint in intervention, Insys allegedly paid doctors sham speaker fees, hired doctors’ friends and relatives, and provided doctors with lavish meals and entertainment to encourage more Subsys prescriptions.[32] The government further asserted that Insys caused federal health care programs to pay for uses of Subsys that are not covered by the programs; for example, the government contended that Insys encouraged doctors to prescribe Subsys even when it was not medically necessary and also misrepresented patients’ medical diagnoses to federal program sponsors.[33] A number of former Insys employees and doctors previously pled guilty to criminal charges relating to alleged kickbacks for Subsys prescriptions,[34] and the company’s former Vice President of Sales pled guilty to one count of racketeering conspiracy in November 2018.[35] The company’s former CEO also pled guilty to conspiracy and mail fraud charges in January 2019,[36] and the trial of several other former executives is currently underway.

The government announced in October that Abbott Laboratories and AbbVie Inc. agreed to pay $25 million to settle claims that Abbott sales representatives provided doctors with gift baskets, gift cards, and other items in exchange for prescriptions of the drug TriCor.[37] The settlement also resolved claims that Abbott marketed and promoted TriCor for unapproved uses, including treatment of diabetic patients and the reduction of cardiac health risks.[38]

In December, the government announced that Covidien (which Medtronic acquired in 2015), agreed to pay $13 million to resolve claims under the FCA stemming from efforts to collect data regarding user experiences with its device.[39] Additionally, Medtronic will pay another $20 million to resolve other DOJ claims “concerning various market-development and physician engagement activities” conducted by Covidien and ev3, which Covidien acquired in 2010.[40]

In addition to the actions above, DOJ announced settlements of several other AKS-related cases with drug and device makers throughout the year:

- In March, Abiomed, Inc. agreed to a $3.1 million settlement to resolve claims that it paid for expensive meals to induce physicians to use the company’s line of heart pumps.[41] The government claimed that Abiomed managers approved expenses for meals even though the cost-per-attendee far exceeded internal company expense guidelines, the company purportedly misrepresented the number of attendees and/or listed fictitious names to make costs appear lower, and attendees ordered alcohol in amounts inconsistent with legitimate scientific discussion.[42] This resolution continues a line of matters in which DOJ has pointed to meal expenses that surpassed company limits as evidence of improper remuneration.[43]

- In May, the government intervened to take part in a $1.9 million settlement with medical equipment supplier Precision Medical Products, Inc. (“PMP”).[44] Between January 2011 and 2017, PMP allegedly based its independent contractor sales representatives’ commissions on the amount of federal health program reimbursements they could obtain.[45] (Notably, HHS OIG rejected expanding the bona fide employee safe harbor to this contract sales force.) The complaint alleged that these acts were illegal kickbacks because they incentivized referrals of patients and patient orders to PMP that may be covered by government-funded programs.[46] PMP also allegedly forged documents to obtain approvals and the related reimbursements for its durable medical equipment (“DME”) products in violation of federal program requirements,[47] including through techniques dubbed “magic time” (i.e., tracing a physician’s signature onto other documents) and “ninja drive” (i.e., using a presigned form).[48] The complaint further asserts that PMP violated federal rules by waiving co-insurance payments and then billing the government.[49]

- In August, Trinity Medical Pharmacy and several of its principals agreed to pay more than $2.24 million to resolve allegations that it knowingly billed government programs for claims driven by kickbacks and omitted its COO’s previous felony conviction from its application to become a certified provider with Express Scripts, the pharmacy benefit manager for TRICARE and several other carriers.[50]

- Also in August, Florida-based provider of oxygen and respiratory therapy services Lincare paid $5.25 million to settle claims that it improperly waived or reduced co-insurance, co-payments, and deductibles for beneficiaries of a Medicare Advantage Plan and caused the submission of false claims for payments to Medicare.[51]

- In December, medical device company LivaNova USA agreed to pay $1.87 million to resolve allegations that it knowingly paid kickbacks in the form of speaking fees to Georgia physicians to induce them to refer its devices for treatment of refractory epilepsy.[52]

3. Other Settlements in FCA Matters

The remainder of the government’s settlement recoveries during 2018 came from alleged violations of government health program requirements or restrictions on off-label promotion.

In October, the government announced the largest FCA enforcement settlement of the year, with AmerisourceBergen Corporation and four of its subsidiaries (“ABC”).[53] ABC agreed to pay $625 million to resolve allegations that a facility it operated repackaged oncology-supportive drugs into pre-filled syringes and distributed those syringes to doctors to provide to cancer patients.[54] The government alleged that ABC sought to profit from the operation by purchasing the syringes from manufacturers, pooling their contents, repackaging the drugs, and harvesting the overfill to create more doses than it originally purchased.[55] The government further claimed that ABC was able to bill multiple health care providers for the same syringe and increase its market share by offering discounts.[56] This settlement follows a 2017 settlement in which one of ABC’s subsidiaries pled guilty to illegally distributing misbranded drugs and agreed to pay $260 million to resolve criminal claims that it distributed the drugs from a facility that was not registered with FDA.[57]

Although the ABC resolution dwarfs DOJ’s other settlements in this space, the past year saw multiple additional enforcement actions involving purported violations of federal program requirements and/or off-label promotion:

- In March, Alere Inc. and its subsidiary, Alere San Diego, agreed to pay $33.2 million to resolve allegations related to sales of purportedly unreliable diagnostic devices.[58] According to the government, Alere received customer complaints that put it on notice that certain of its devices used to diagnose serious heart conditions potentially transmitted false positives and false negatives; nevertheless, the government alleged, the company did not take appropriate corrective actions until government inspections resulted in a nationwide recall.[59] Of the settlement, more than $4.8 million will be returned to individual states.[60]

- In April, Allergan, Inc. settled claims involving allegations that the company sold purportedly defective weight loss devices, marketed the device for use in surgical procedures that were not described in the product’s approved labeling, and made inappropriate payment to physicians.[61] Allergan agreed to pay $3.5 million in connection with the resolution, nearly $200,000 of which will be split among impacted states.[62]

- In July, medical device manufacturer AngioDynamics agreed to pay $11.5 million to resolve allegations that it marketed a product for unapproved uses and instructed health care providers to use incorrect billing codes to submit claims for those uses.[63] It also agreed to pay an additional $1 million to settle claims that certain AngioDynamics employees represented to health care providers that federal health care programs would cover an unapproved use of a recalled and re-issued product previously used to treat perforator veins, thus causing false claims to be submitted to the programs.[64]

- In September, the government announced that now-defunct compounding pharmacy RS Compounding and its owner agreed to pay $1.2 million to resolve allegations that it charged federal health care programs a higher price for its drugs (in some cases, over 10,000 percent higher) than it charged the public.[65]

- In October, Cooley Medical Equipment agreed to pay more than $5.25 million to settle claims that it falsely stated that certain of its compounded medical creams used cream-based ingredients rather than bulk powder, to avoid prior authorization requirements for bulk powder ingredients or limited reimbursement from federal health care programs.[66] Cooley self-disclosed the conduct and will be allowed to pay the settlement amount—which, according to the government, is 1.5 times the amount of monetary loss caused by the false claims—over a period of six years.[67] Because the government typically insists on doubling purported damages in settlement discussions, it appears that the government underscored the loss calculation so as to encourage other entities to self-disclose and cooperate.

B. Developments in Enforcement Actions Against Opioid Manufacturers and Distributors

As reported in our 2017 Mid-Year and Year-End updates, DOJ has made criminal and civil enforcement related to the opioid epidemic a top priority. Reflecting on developments in 2018, it is clear that DOJ is following through on its commitment to target aggressively the opioid epidemic, and all signs indicate that these efforts are likely to persist for the foreseeable future.

Numerous comments by DOJ officials suggest that DOJ is prepared to pursue litigation against manufacturers in conjunction with the Department’s efforts to stem the tide of opioid misuse, overdoses, and deaths. On February 27, 2018, DOJ announced the creation of the Prescription Interdiction & Litigation (“PIL”) Task Force, which “will aggressively deploy and coordinate all available criminal and civil law enforcement tools” to curb the opioid epidemic, “with a particular focus on opioid manufacturers and distributors.”[68] In remarks delivered the following day, Deputy Assistant Attorney General Stephen Cox specifically stated that DOJ would be using the FCA as a tool to address the opioid epidemic.[69] Just last month, Deputy Assistant General James Burnham also commented that the FCA and FDCA “are squarely implicated” should a pharmaceutical company misrepresent opioid-related risks; he cited potential enforcement avenues against pharmaceutical companies, including actions under the Controlled Substances Act (“CSA”) for failure to report suspicious orders of controlled substances and misbranding-related actions under the FDCA for failure to communicate adequate risk information in accordance with FDA-required Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies.[70]

DOJ also announced a program this year to target suppliers and wholesale distribution networks responsible for distributing fentanyl and other synthetic opioids, which will focus on ten districts with high rates of deadly drug overdoses.[71] In support of these enforcement efforts, DOJ is utilizing a new data analytics program focusing specifically on opioid-related health care fraud, which enables DOJ officials to pinpoint areas with high rates of prescription, dispensing, and overdoses.[72]

In some cases, DOJ’s heated rhetoric has previewed hard-hitting acts. In April, DOJ intervened in now-consolidated suits alleging AKS-related violations against Insys Therapeutics, Inc., the manufacturer of a sublingual fentanyl spray approved for the treatment of breakthrough pain in adult cancer patients already on opioid therapy. In addition to the AKS-related claims noted above, the complaint alleged that the manufacturer encouraged off-label use of the product in situations where the use was “not medically reasonable and necessary” and misrepresented patient diagnoses to secure reimbursement for the company’s product.[73] As discussed above, Insys Therapeutics reached an agreement in principle with the government to pay at least $150 million and potentially up to $225 million to resolve the claims.[74] Several former Insys employees and doctors previously pled guilty to criminal charges relating to alleged kickbacks for Subsys prescriptions,[75] the company’s former Vice President of Sales pled guilty to one count of racketeering conspiracy in November 2018,[76] and the company’s former CEO recently pled guilty to conspiracy and mail fraud charges in January 2019.[77]

Further underscoring the government’s ongoing scrutiny of the industry, other manufacturers also have disclosed that they are in receipt of subpoenas related to the manufacture, distribution, and marketing of opioids, including three manufacturers that received subpoenas from the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of Florida related to generic opioid products.[78]

In April, DOJ also filed a “friend of the court” motion in ongoing multidistrict litigation against opioid manufacturers and distributors to enable it to participate in settlement negotiations.[79] Before filing its motion, DOJ announced that it would seek reimbursement from the defendants for the costs that the federal government has incurred as a result of the opioid epidemic, such as costs borne by federal health care programs and the expenses associated with law enforcement initiatives.[80] And, in August, DOJ announced the unsealing of an indictment charging two Chinese citizens with operating a conspiracy through numerous companies (including companies within the United States) to manufacture and ship fentanyl analogues and other drugs illegally to the United States.[81]

Of note, DOJ has taken steps to address the opioid epidemic from a regulatory perspective as well. Observing that the United States is an outlier in the number of opioids prescribed each year, former Attorney General Jeff Sessions issued a memo directing the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (“DEA”) to evaluate whether to amend regulations addressing the aggregate production quota, which sets the quantity of opioids that manufacturers are permitted to produce each year.[82] In response, the DEA issued a proposed rule that would limit opioid production in some instances and strengthen controls to prevent diversion of controlled substances.[83] Later in the year, in an effort to “encourage vigilance on the part of opioid manufacturers,” DOJ and the DEA proposed an average ten percent reduction in 2019 manufacturing quotas for the six most frequently misused opioids.[84]

On October 24, 2018, President Trump also signed into law The Substance Use – Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities Act (the “SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act”), which seeks to “reduc[e] access to the supply of opioids by expanding access to prevention, treatment, and recovery services.”[85] Among other items, the bipartisan legislation bolsters requirements for CSA registrants to design and operate systems to identify suspicious orders and report those orders to the DEA,[86] requires drug manufacturers and distributors to review quarterly DEA reports showing the total number of registrants distributing controlled substances as well as the total quantity and type of opioids distributed to pharmacies and practitioners,[87] requires HHS to support state efforts to develop their own prescription drug monitoring programs, and allows FDA to recall a controlled substance if it determines there is a “reasonable probability” that the controlled substance “would cause serious adverse health consequences or death.”[88]

C. Notable Developments in FDCA Enforcement

In 2018, DOJ obtained a number of injunctions against and resolutions with manufacturers and distributors to prevent the sale and distribution of allegedly unapproved, adulterated, and misbranded drugs or devices.

In December, DOJ secured guilty pleas—and a significant fine—in an FDCA case alleging that Tokyo-based Olympus Medical Systems Corporation and a former senior executive distributed misbranded medical devices in interstate commerce.[89] According to the government (and the plea documents), Olympus failed to file adverse event reports, known as Medical Device Reports (“MDRs”), with FDA in 2012 and 2013 after learning that certain patients using its duodenscopes contracted infections.[90] Olympus allegedly also received an independent expert report in 2012 that identified the possibility of bacteria in the duodenscopes and recommended further investigation and updated cleaning instructions.[91] Under the FDCA, devices with required but unfiled MDRs or supplemental MDRs are deemed misbranded.[92] Pursuant to the plea deal, the U.S. District Court for the District of New Jersey fined Olympus $80 million and ordered $5 million in criminal forfeiture. Olympus also agreed to implement a number of compliance measures, including the retention of an MDR expert who will review Olympus’s compliance with the FDCA’s MDR requirements, as well as periodic review by the company’s president and board of directors.[93] The sentencing of the former executive is set for March 2019.[94]

DOJ also pursued several drug and device makers for alleged promotion of unsupported therapeutic claims and other unapproved uses.

In March, for example, DOJ announced that the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Florida permanently enjoined a Florida company, MyNicNaxs LLC, and two associated individuals from selling sexual enhancement and weight loss products until the company institutes specific remedial measures and obtains written approval from FDA.[95] According to the complaint, the products contained undisclosed ingredients, some of which have been shown to increase the risk of heart attacks and strokes. Further, the government alleged that no scientific evidence supported the company’s claims that the products cured or prevented serious diseases.[96]

The U.S. District Court for the District of New Jersey in August similarly enjoined two companies—S Hackett Marketing LLC d/b/a Just Enhance of Trenton, New Jersey and R Thomas Marketing LLC of Bronx, New York—and related individuals from selling unapproved sexual enhancement products that the government claimed contained an undisclosed ingredient and also lacked labels revealing potentially adverse consequences of using the products.[97]

In July, three related Chicago companies, their owner, and their operations manager also agreed to settle claims that they were manufacturing, selling, and distributing adulterated and misbranded dietary supplements and unapproved drugs and to be bound by a consent decree of permanent injunction.[98] The government’s complaint alleged that the companies’ claims that their products could help prevent or treat diseases such as Alzheimer’s, diabetes, HIV, and Parkinson’s were unsupported by credible scientific evidence, labels were deficient, and FDA inspections revealed failures to comply with current good manufacturing practice regulations, including failure to establish written sanitation procedures.[99]

In early December, Minnesota-based medical device manufacturer ev3 Inc. agreed to plead guilty to a misdemeanor charge in connection with distribution of its liquid embolization device, Onyx.[100] The government alleged that, although FDA approved Onyx only for use inside the brain, ev3 sales representatives encouraged surgeons to use Onyx for other, unapproved uses from 2005 to 2009.[101] The government further claimed that ev3’s management designed sales quotas and bonuses that incentivized sales of Onyx for such uses.[102] As part of the resolution, ev3 will pay a fine of $11.9 million, and it will forfeit $6 million.[103] Medtronic, ev3’s current parent company, also has agreed to implement new compensation structures and conduct compliance monitoring relating to Onyx sales and marketing.[104] As noted above, DOJ separately entered into a civil settlement with Covidien related to allegations brought under the FCA.

DOJ also took action against several companies in connection with purported current good manufacturing practice (“cGMP”) violations:

- As described in more detail below, DOJ announced consent decrees permanently preventing distribution of adulterated drugs by two compounding pharmacies, Cantrell Drug Company and Delta Pharma, Inc., and related individuals.[105] DOJ alleged that the drugs were adulterated because the companies failed to comply with cGMP requirements and because the drugs may have been contaminated as a result of insanitary conditions.

- In October, DOJ also announced consent decrees of permanent injunctions to prevent distribution of misbranded drugs against Keystone Laboratories, Inc. and its owner and operator.[106] DOJ alleged that Keystone distributed hair and skin care products that failed to comply with FDA’s cGMPs due to potential bacterial contamination from insanitary conditions.[107] The company cannot begin manufacturing again unless it complies with specific remedial measures, and the injunction provides for safeguards if the defendants work with third parties to manufacture their products.[108]

D. FCPA Investigations

Although multiple DOJ and SEC investigations into the foreign sales practices of many drug and device companies remain ongoing, DOJ did not announce any FCPA settlements with drug and device companies in 2018. This quiet may not last long: DOJ previously signaled that it plans to ramp up its FCPA enforcement in the health care space, as discussed in our 2017 Year-End Update. In a speech delivered in 2017, Sandra Moser, then-Acting Chief of DOJ’s Fraud Section, announced that prosecutors from DOJ’s FCPA unit would begin “working hand in hand” with the Corporate Strike Force of DOJ’s Healthcare Fraud Unit to “investigate and prosecute matters relating to healthcare bribery schemes, both domestic and abroad.”[109]

For its part, the SEC announced two FCPA settlements with drug and device companies in 2018.

- On September 4, a Paris-based pharmaceutical company agreed to pay more than $25 million in disgorgement, prejudgment interest, and penalties to resolve FCPA-related charges by the SEC regarding alleged corrupt payments to government procurement officials and health care providers in Kazakhstan and the Middle East. The company also agreed as part of the resolution to self-report about anti-corruption compliance to the SEC for a two-year period.[110]

- On September 28, a Michigan-based medical device company settled FCPA-related charges by the SEC. According to the SEC, the company violated the books and records and internal accounting controls provisions of the FCPA. The company agreed to pay a $7.8 million penalty, and the settlement was the SEC’s second FCPA action against the company. The company did not admit or deny the SEC’s charges, but consented to a cease-and-desist order and the penalty.[111]

II. FCA JURISPRUDENCE DEVELOPMENTS RELEVANT TO DRUG AND DEVICE COMPANIES

A. Developments in the Implied Certification Theory’s Materiality Requirement

As detailed in our 2017 Mid-Year and Year-End False Claims Act Updates, the federal courts continue to grapple with the implications of the Supreme Court’s decision in Universal Health Servs., Inc. v. United States ex rel. Escobar (“Escobar”).

Under the theory of falsity addressed in Escobar, a company impliedly certifies compliance with all conditions of payment when it submits a claim to the government and, if that claim fails to disclose the violation of a material statutory, regulatory, or contractual requirement, the omission renders the claim false in violation of the FCA. In Escobar, the Supreme Court held that the implied false certification theory can be a basis for FCA liability if two conditions are met:

- “[F]irst, the claim does not merely request payment, but also makes specific representations about the goods or services provided; and

- [S]econd, the defendant’s failure to disclose noncompliance with material statutory, regulatory, or contractual requirements makes those representations misleading half-truths.”[112]

One area of focus in post-Escobar cases involving companies in the health care industry has been the question of what, if any, impact the government’s continued payment of claims should have on the materiality analysis.

In June, for instance, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois allowed an FCA claim by the government to proceed against Snap Diagnostics, the manufacturer of a home sleep apnea test.[113] The government alleged that the company encouraged unnecessary tests to be billed to Medicare where only a single test was required. According to the government, the company, in lobbying the government for Medicare coverage of its testing, advised that it was routine to conduct only one night of sleep apnea testing, and the company’s promotional materials stated that a diagnosis can almost always be made in a single night of testing. But the company’s alleged procedure was to bill for multiple nights of testing only when the patient was Medicare-covered or self-pay, but not when the patient had private insurance. Further, the government asserted that the decision was not based on a clinical determination of medical necessity. Additionally, the government pointed to Medicare guidance stating that Medicare will cover a second or third night of sleep apnea testing only when it is medically necessary.

Addressing materiality at the motion-to-dismiss stage, the court rejected the argument that the government’s routine payment of multiple claims served as evidence that the requirements were not material. The court not only concluded that this argument was premature at the pleading phase, but also described this argument as a “logical falsity” that misstates the Supreme Court’s position in Escobar.[114] Relying on the Seventh Circuit’s decision in United States v. Sanford-Brown, Ltd.,[115] the court ruled that the government met its burden in showing materiality. Because Medicare guidance provided for reimbursement of a second or third night of sleep apnea testing only when medically necessary, the court found that the company’s submission of claims for subsequent nights of testing could constitute a misleading representation that those nights had been determined to be medically necessary and permitted the claim to go forward.

In another matter implicating the materiality analysis post-Escobar, the Supreme Court recently denied certiorari in a case in which Gilead Sciences, Inc. sought review of a Ninth Circuit decision allowing a qui tam suit to continue past the motion to dismiss stage (United States ex rel. Campie v. Gilead Sciences, Inc.).[116] The Ninth Circuit held that the relators adequately alleged that Gilead fraudulently obtained FDA approval for certain of its drugs by making purportedly false statements to FDA about the source of the drugs’ active ingredient and the ingredient’s compliance with FDA regulatory requirements. Because Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement for drugs is contingent upon FDA approval, which Gilead allegedly obtained fraudulently, the Ninth Circuit concluded that Gilead’s submission of claims for payment for “FDA approved” drugs amounted to a material misrepresentation that could serve as a basis for liability under the FCA. The Ninth Circuit rejected Gilead’s argument that, because FDA did not rescind approval of the drug after learning of the violations and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services continued to pay for the drug, the violations were not material to the government’s payment decision. Instead, the court reasoned that Gilead ultimately stopped using the active ingredient from the unapproved manufacturer, and “[o]nce the unapproved and contaminated drugs were no longer being used, the government’s decision to keep paying for compliant drugs does not have the same significance as if the government continued to pay despite continued noncompliance.”[117]

Gilead’s petition for certiorari presented the question of whether the government’s decision to continue reimbursement after learning of alleged regulatory infractions should presumptively defeat a relator’s claim that the regulatory infractions were material to the government’s payment decision.[118] Gilead maintained that the Ninth Circuit’s treatment of this issue clashes with the Supreme Court’s instruction in Escobar that “if the Government pays a particular claim in full despite its actual knowledge that certain requirements were violated, that is very strong evidence that those requirements are not material.”[119]

As discussed in our prior updates, the Supreme Court invited the Solicitor General to present the government’s position on the case, thereby signaling interest in the impact of government acquiescence on efforts by the government or relators to establish materiality. In response, the Solicitor General argued strongly that the Court should not grant certiorari and indicated that it would move to dismiss the case if it were sent back to the district court.[120] Arguing that the case is “not in the public interest,” DOJ explained that its position was based on a “thorough investigation” of the merits of the case, as well as concerns about the “burdensome” discovery requests that the parties would direct at FDA if the case were to move forward.[121] With the Supreme Court’s denial of certiorari, the case has returned to the district court in accordance with the Ninth Circuit’s previous decision, and DOJ has not yet moved to dismiss the case at the district court level.

Whether or not DOJ’s seemingly abrupt move before the Supreme Court reveals any deeper concerns within DOJ around potentially adverse post-Escobar rulings, it is a marked example of DOJ’s purported commitment under the Justice Manual and Granston Memo to dismissing at least some of the unmeritorious cases brought forth by qui tam relators. In the meantime, the question of government acquiescence in the context of materiality remains open for courts’ consideration.

B. Scienter under Escobar

The Supreme Court in Escobar expressed confidence that robust enforcement of the FCA’s scienter and materiality elements would prevent a broad view of falsity from subsuming the purposes of the Act. One (albeit unpublished) appellate decision this past year provides at least some support for this perspective.

In United States ex rel. Streck v. Allergan, Inc., the Third Circuit held that an FCA relator fails to plead scienter where the defendant acted based on a reasonable, albeit incorrect, interpretation of relevant statutory and regulatory guidance.[122] The relator in Streck based his FCA claims on allegations that the defendant pharmaceutical companies failed to account for “price-appreciation credits” in submitting Average Manufacturer Prices (“AMPs”) for certain drugs when calculating rebates owed by those companies to Medicaid under the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program.[123] In assessing the relator’s claims, the court first considered “whether the relevant statute was ambiguous,” then evaluated “whether [the] defendant’s interpretation of that ambiguity was objectively reasonable,” and, finally, assessed “whether [the] defendant was ‘warned away’ from that interpretation by available administrative and judicial guidance.”[124] The Third Circuit observed that the statutory definition of “price paid to the manufacturer” for AMP purposes was unclear because it did not specify whether it was the “initial” price (which would have excluded subsequent price-appreciation credits) or “cumulative” price (which would have included them).[125] Even though the defendants’ interpretation that the statute and the associated guidance excluded price-appreciation credits may not have been “the best interpretation,” the Third Circuit nonetheless concluded that the interpretation was reasonable, that there was no guidance “warn[ing] away” from that interpretation, and that holding defendants liable for a “reasonable interpretation of an ambiguous statute was inconsistent with the reckless disregard [relator] was required to allege at this stage of the litigation.”[126]

C. Rule 9(b) Particularity

Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 9(b) requires FCA plaintiffs to plead allegations of fraud with particularity. In cases brought against companies, such as drug and device manufacturers, that do not typically submit claims to government payors directly, Rule 9(b) requires an FCA complaint to adequately plead facts establishing a link between the defendant’s challenged conduct and claims for reimbursement submitted by third-party physicians or pharmacies to the government. As discussed in our 2017 Mid-Year and Year-End updates, courts have diverged over the question of what allegations suffice to survive a Rule 9(b) challenge on a motion to dismiss.

In United States ex rel. Solis v. Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the Ninth Circuit added to the body of precedent holding that FCA claims that fail to allege particularized facts linking the alleged scheme to at least one specific claim submitted to the government cannot survive a Rule 9(b) motion to dismiss.[127] The relator, a pharmaceutical sales representative, brought a qui tam FCA action against his former employer alleging, among other things, that the company paid kickbacks to physicians to prescribe the antibiotic drug Avelox. The district court dismissed all of the relator’s claims, holding that they were foreclosed by the public disclosure bar.

On appeal, the Ninth Circuit held that the district court had erred in holding that the public disclosure bar foreclosed the relator’s claim relating to Avelox because none of the public disclosures at issue mentioned this claim. Noting that it could affirm on any ground supported by the record, the Ninth Circuit nevertheless affirmed the district court’s dismissal of this claim, holding that it failed to satisfy Rule 9(b) particularity requirements. The relator’s “only particularized allegations” showed efforts by the defendant “to get Avelox placed ‘on formulary’ at two hospitals,” which “merely means the drug is available to be used or prescribed.”[128] “Even assuming these efforts established a scheme to submit false claims,” the relator neither “identif[ied] a single claim submitted pursuant to the scheme” nor provided “reliable indicia supporting a strong inference that such claims were submitted.”[129] Indeed, the Ninth Circuit noted that the relator did not even “allege that being ‘on formulary’ meant such claims would be submitted,” or that “being on formulary meant Avelox would be prescribed.”[130] Because the complaint did not contain “other details linking the alleged scheme to any claim submitted to a federal healthcare program,” the relator failed to “plead[] with the particularity required by Rule 9(b).”[131]

The Eleventh Circuit reached a similar conclusion in Carrel v. AIDS Healthcare Foundation, Inc.[132] There, the relators alleged that the foundation violated the AKS and thus the FCA by paying bonuses to its employees for referring patients with HIV/AIDS to other services provided by the foundation and for which the foundation sought federal reimbursement. In addition to rejecting the relators’ AKS theory (as described below), the Eleventh Circuit also rebuffed relators’ assertion that the district court erred in dismissing a host of relators’ claims for lack of particularity.

Long-standing Eleventh Circuit requires relators to plead the “actual ‘submission of a [false] claim’” with some “indicia of reliability”; assertions that a “claims requesting illegal payment must have been submitted, were likely submitted[,] or should have been submitted” do not suffice.[133] Applying that precedent in Carrel, the Eleventh Circuit observed that although relators “allege[d] a mosaic of circumstances that are perhaps consistent with their accusations that the Foundation made false claims . . . [they] fail[ed] to allege with particularity that these background factors ever converged and produced an actual false claim.”[134] Notably, the court batted aside relators’ efforts to rely on “mathematical probability” and their insider knowledge of the foundation’s operations, explaining that relators’ “access to possibly relevant information” did not “translate[] to knowledge of actual tainted claims presented to the government.”[135]

D. Retaliation

The FCA provides remedies to employees if they are “discharged, demoted, suspended, threatened, harassed, or in any other manner discriminated against in the terms and conditions of employment because of lawful acts” conducted in furtherance of an FCA claim.[136]

In DiFiore v. CSL Behring, LLC, the Third Circuit recently addressed the standard for showing causation in an FCA retaliation claim brought against a biopharmaceutical company. The plaintiff appealed the district court’s jury instruction requiring the plaintiff to show “protected activity was the ‘but-for’ cause of an adverse action.”[137] On appeal, the plaintiff argued that the FCA only requires proof that the protected activity was a “motivating factor” in the adverse action.

In rejecting this argument and affirming the district court, the Third Circuit relied on the Supreme Court’s analysis in Gross v. FBL Financial Services, Inc.[138] and University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center v. Nassar,[139] both of which concerned the causation standard in the discrimination context. The court observed that the statutory text “because of” was identical in the FCA to the language used in the Age Discrimination in Employment Act and Title VII’s anti-retaliation provision, and in those contexts the Supreme Court held that this language requires proof that the protected status or activity was the “but-for causation” for the employer’s adverse employment action. The court contrasted this “because of” language with the text of the anti-retaliation regulation under the Family Medical Leave Act (“FMLA”), which required the protected activity to be a “negative factor” in an employment decision. Because the FCA included the same “because of” language at issue in Gross and Nassar, rather than the “negative factor” language used in the FMLA regulation, the court held that the “but-for” standard adopted in Gross and Nassar governed its interpretation of causation under the FCA.[140]

E. Public Disclosure Bar

As amended by the Affordable Care Act in 2010, the FCA’s public disclosure bar provides that a court “shall dismiss” an FCA action if “substantially the same allegations or transactions . . . were publicly disclosed” through listed sources, as long as the relator does not qualify as an “original source.”[141] A relator is an “original source” when he or she either “prior to a public disclosure . . . voluntarily disclosed to the Government the information on which allegations or transactions in a claim are based,” or “has knowledge that is independent of and materially adds to the publicly disclosed allegations or transactions.”[142] Courts have adopted differing interpretations of this statutory language, including as to what standard to apply in determining whether information “materially adds” to publicly disclosed allegations.

In United States ex rel. Forney v. Medtronic, Inc., the Third Circuit was called upon, in the context of a qui tam action, to determine whether Escobar’s interpretation of “materiality” as an element of a fraud claim should govern the analysis of whether information “materially adds” to the allegations for purposes of the public disclosure bar.[143] In United States ex rel. Moore & Co., P.A. v. Majestic Blue Fisheries, LLC,[144] which preceded Escobar, the Third Circuit adopted a broad definition of materiality, holding that the relevant standard in this context is “whether the relator ‘contributes information—distinct from what was publicly disclosed—that adds in a significant way to the essential factual background: the who, what, when, where and how of the events at issue.’”[145] By contrast, the First Circuit in United States ex rel. Winkelman v. CVS Caremark Corp.[146] applied the more “rigorous requirement” for materiality adopted in Escobar, which requires that, “for something to be material, it must be of such importance that it influences the decision maker.”[147]

In Forney, the Third Circuit concluded that the Supreme Court’s interpretation of “materiality” as an element in a fraud claim in Escobar had “little bearing” on the concept of materiality in the entirely different context of the public disclosure bar.[148] Thus, because Escobar did not compel a different interpretation of materiality in this context, the court concluded that it continued to be bound by the Third Circuit’s more lenient standard in Moore.[149] Applying this standard, the court held that the relator qualified as an original source. The relator’s documents included records documenting Medtronic representatives engaging in the challenged activity, including “the names” of individuals involved as well as the “places and times” of the activity.[150] The court rejected the argument that this information was encompassed in the broader and more general allegations in prior public disclosures, holding that the information the relator provided was “detailed, specific, and helpful,” and thus “meaningfully add[ed] to the prior public disclosures.”[151]

F. First-to-File Bar

The FCA’s first-to-file bar “prohibits a person from bringing a ‘related action’ when an FCA suit is pending.”[152] Despite the deceptively simple language, circuits have begun to diverge on how to enforce the bar when the court has already dismissed the earlier, “pending” action.

In United States ex rel. Wood v. Allergan, Inc.,[153] the Second Circuit joined the D.C. Circuit in holding that a relator may not proceed based on an amended complaint if the same relator’s original complaint otherwise would fail under the first-to-file bar. Below, the district court held that, although at least one related complaint against Allergan already existed when the relator filed suit, amending his complaint after the court had dismissed the other, related complaint was sufficient to overcome the bar, because “there were no pending related actions when the complaint was amended.”[154] Focusing on the plain language of the statute, which requires dismissal when a relator “brings” an action while a related action is pending, the Second Circuit disagreed with the district court’s analysis and held that the relator’s action “was incurably flawed from the moment he filed it.”[155] The Second Circuit confirmed, however, that dismissal based on the first-to-file bar should be without prejudice,[156] and that “absent a statute of limitations issue, the relator will be able to re-file her action, without violating the first-to-file bar.”[157]

In the opinion, the Second Circuit also weighed in on another developing circuit split regarding whether a complaint that falls short under Rule 9(b)’s particularity requirement can bar a later-filed complaint under the first-to-file rule. Again agreeing with the D.C. Circuit, the Wood court found no basis to incorporate Rule 9(b)’s particularity requirement into the statute.[158] That a subsequent complaint might be “more detailed” has no bearing on the application of the first-to-file bar under the Second Circuit’s interpretation, and the court thus found that the relator’s allegations were sufficiently related to those in the other, earlier complaint to trigger the bar, even if his allegations were “more detailed” than those previously asserted.[159]

Should the circuit courts continue to diverge on these issues, the resulting split may present opportunities for the Supreme Court to grant certiorari and weigh in on the proper application of the bar. The Court has demonstrated some willingness to address FCA-related issues in recent months when it granted certiorari in United States ex rel. Hunt v. Cochise Consultancy, Inc., 887 F.3d 1081, 1083 (11th Cir. 2018), to address questions regarding the FCA’s statute of limitations provision.

III. PROMOTIONAL ISSUES

This past year saw relatively few developments in the regulation of drug and device promotional activity compared to prior years. Most notably, FDA issued two guidance documents in June 2018 that signaled greater flexibility in FDA’s approach to promotional communications; the guidance greenlighted the transmission of certain information that is not included in FDA-required labels (so long as it is consistent with those labels), as well as economic information about drugs and devices. In a statement about the guidance documents, FDA Commissioner Dr. Scott Gottlieb explained that the guidance is intended to help market participants develop contracts that better reflect the full value of products in the marketplace.[160]

In the meantime, Congress failed to make significant progress toward implementing off-label promotion legislation, and the federal courts did not issue any notable opinions clarifying how drug manufacturers should convey promotional information about their products. FDA enforcement activity increased only slightly relative to last year’s drop in enforcement.

Considering the current administration’s deregulatory position, FDA is likely to continue its scaled back approach to off-label promotion. If the past two years are any indicator, the agency will remain focused on the most flagrant cases of deceptive advertising or when there is a risk to public health, leaving manufacturers some leeway for more expansive promotional activity.

A. FDA Enforcement Activity – Drug Promotion

In 2018, the Office of Prescription Drug Promotion (“OPDP”) issued only two Warning Letters and five Untitled Letters.[161] While this number represents a small uptick from 2017, it still falls far short of the statistics from the years of more aggressive enforcement that preceded the First Amendment litigation.[162] The downward trend may be an indicator that the current administration’s priorities lie elsewhere—at least for the foreseeable future.

Of the seven letters, four involve the omission or minimization of risk information, two concern inaccurate information regarding an unapproved use or product, and one objects to false or misleading claims about efficacy.[163] All of the approved products relate to products with boxed warnings. The letters encompass a range of communications, including conference exhibitions, oral statements by a sales rep, print materials, websites and online vides, and social media.

- In a February 9, 2018 Untitled Letter to Collegium Pharmaceutical, Inc., OPDP asserted that the company’s exhibit booth at an annual pharmacist exhibition made false or misleading representations about an opioid pain reliever because the exhibit failed to communicate accurately the drug’s risks.[164] The letter noted that the exhibit did not include any information regarding the drug’s limitations of use, namely that the drug should be used only as a last resort for treating pain because of its high addiction risks.[165] The letter also emphasized that the omission was particularly concerning considering the severe impact of opioid addiction.[166] Although the exhibit had included a side panel that conveyed some warning information, OPDP noted the small font and found this disclosure to be inadequate.[167]

- Similarly, in a June 19, 2018 Untitled Letter to Pfizer Inc., OPDP objected to a direct-to-consumer promotional video for failing to include any risk information regarding the product, a vaginal ring.[168] OPDP also objected to the testimony of the video’s featured spokesperson, who stated that the drug had worked instantaneously and had not resulted in any side effects in her case.[169] OPDP found that the spokesperson’s claims, even if accurate, misleadingly suggested that other patients would experience similar results.[170]

- In a June 28, 2018 Untitled Letter to Arog Pharmaceuticals, Inc., OPDP asserted that the company violated the FDCA by misbranding an investigational acute myeloid leukemia drug both on the company’s website and at its booth display at an annual hematology meeting.[171] According to FDA, both promotions suggested that the drug was safe and effective, even though FDA had yet to approve the drug for commercial purposes.[172]

- In an August 16, 2018 Untitled Letter to ASCEND Therapeutics US, LLC, OPDP objected to a sell sheet that allegedly made false and misleading claims about the efficacy of ASCEND’s hormonal drug, EstroGel.[173] The sell sheet asserted that EstroGel provides the lowest effective dose of estrogen for treatment of certain moderate to severe menopausal-related symptoms, yet OPDP concluded such claims were not supported by the literature cited because it did not rely on studies comparing the drug to other FDA-approved formulations of estrogen.[174]

- In an October 5, 2018 Warning Letter to MannKind Corporation, OPDP asserted that the company’s Facebook post describing its inhalation powder, Afrezza, as helping “your body work its best and protection from health complications” with “no drama” misleadingly suggested an absence of safety concerns, because it omitted information about potentially life-threatening risks.[175] Although the post contained a small pop-up box with information about the risk of acute bronchospasm in patients with chronic lung disease, OPDP concluded that this did not mitigate the deficiencies of the post.[176]

- In an October 11, 2018 Untitled Letter to Eisai Inc., OPDP objected to oral statements that an Eisai sales representative made to health care professionals at a lunch presentation regarding its Fycompa drug for treatment of partial-onset seizures in epileptic patients 12 years and older.[177] The sales representative purportedly mischaracterized the scope of the new indication for which the company sought FDA-approval in a pending new drug application for pediatric patients and minimized the serious boxed warning risks of behavioral side effects.[178]

- Finally, in an October 22, 2018 Warning Letter to Vanda Pharmaceuticals Inc., OPDP objected to Vanda’s webpage, which it claimed lacked appropriate risk information about its drugs.[179] While the letter acknowledged that the webpage referred visitors to another site that provided the box warnings and safety information, OPDP concluded that this did not mitigate the complete omission of any risk information from the webpage itself.[180]

B. FDA Enforcement Activity – Device Promotion

Enforcement relating to medical device promotion remained quiet as well, with only one Warning Letter to a medical device manufacturer. In addition, CDRH issued seven “It Has Come to Our Attention” Letters, questioning whether marketing claims about certain 510(k)-cleared devices were covered by existing clearances and whether products were being promoted for medical device uses without a required premarket clearance or approval.

- RADLogics, Inc Warning Letter.[181] In its Warning Letter to RADLogics, FDA asserted that the company’s marketing claims exceeded those supported by the 510(k) clearance for the company’s radiological image analysis software application. Citing claims on the company’s website and YouTube video, FDA concluded that the device had been cleared for displaying radiological images for analysis by physicians, but the device was promoted as a “Virtual Resident” that could provide computer-assisted detection and marking of abnormalities in images.

- Letters Regarding Vaginal Treatments. In addition, CDRH issued seven “It Has Come to Our Attention” Letters relating to the promotion of products for vaginal treatments in July, questioning whether marketing claims about the 510(k)-cleared devices were covered by existing clearances and whether products were being promoted for medical device uses without a required premarket clearance or approval. Five of the letters related to laser, radiofrequency, and similar devices that had 510(k) clearances for general uses in dermatologic and surgical applications such as ablation of soft tissue. For example, Cynosure,’s DEKA SmartXide2 Laser System had a 510(k) clearance for incision, excision, ablation, vaporization, and coagulation of body soft tissues in a variety of medical specialties, but FDA objected to the promotion of the device as a “clinically proven laser treatment for the painful symptoms of menopause, including intimacy.” Similarly, FDA objected to “vaginal health restoration” and similar claims for products marketed by Inmode MD Ltd. and Venus Concept, Ltd., noting that these products lacked any device premarket clearance or approval.

In addition to these enforcement letters, in May 2018, FDA filed civil complaints in Florida and California alleging that two stem cell clinics were experimenting on patients with adulterated, misbranded, and unapproved drugs.[182] The first complaint targeted U.S. Stem Cell Clinic LLC of Sunrise, Florida, U.S. Stem Cell, Inc., its Chief Scientific Officer, and its co-owner and Managing Officer. The second was brought against California Stem Cell Treatment Center Inc., Cell Surgical Network Corporation of Rancho Mirage, and two doctors. Despite arguments that FDA approval was not needed because patients receive treatment with their own cells, FDA sought to enjoin these clinics from marketing stem cell therapies that do not have FDA approval. The complaints allege that defendants manufactured unapproved stromal vascular faction (“SVF”) products from patient adipose (fat) tissue. U.S. Stem Cell, Inc. previously faced scrutiny from FDA in August 2017 after several patients reported vision loss after SVF treatments; in a statement, the agency said it was acting because the U.S. Stem Cell Clinic did not address violations outlined in a Warning Letter from August 2017.[183] Finally, the complaints state that recent FDA inspections showed the clinics violated cGMP requirements, including some that could impact the sterility of their products.[184]

Notably, therapies in this space have drawn attention from Commissioner Gottlieb, who has vowed that FDA will crack down on clinics marketing questionable or unsafe treatments. That said, Commissioner Gottlieb also has pledged to ease the path to approval for researchers and companies marketing stem cell therapies and regenerative medicine where treatments are legitimate.[185]

C. FDA’s Promotional Guidance – Drugs & Devices

In keeping with its promise to provide more direction regarding the off-label promotion of drugs and devices, FDA issued two useful guidance documents in June 2018.[186] According to FDA Commissioner Gottlieb, the agency aims to spur a “shift toward innovative, value-based payment arrangements” for medical products.[187] To that end, FDA promulgated guidance to provide clarity to drug manufacturers as they develop communications about their medical products, which in turn will ensure that patients, providers, and insurers have access to a wide range of data that they can harness to negotiate prices.[188]

Communications with Payors. In the first guidance document, FDA authorized companies to share certain information with payors about unapproved products and unapproved uses of approved drugs and devices.[189] The guidance assured drug manufacturers that they will not be subject to FDA enforcement for promoting truthful and non-misleading information that is consistent with FDA-required labeling.[190] According to the guidance, FDA will analyze three factors in determining whether promotional information is consistent with the labeling.

- First, FDA will evaluate whether communications about the product conflict with particular conditions of use in FDA-required labeling.[191]

- Second, FDA will assess whether the promotional information increases the product’s potential for harm to health, relative to the product’s FDA-required labeling information.[192]

- Finally, FDA will consider whether the product’s label enables patients to use the product safely and effectively under the conditions suggested in the product communications.[193]

The guidance provides examples of the kinds of information that FDA would and would not consider consistent.[194] For instance, communications providing context about adverse reactions associated with the product’s use would be consistent with FDA-required labeling.[195] By contrast, information about a product’s use to treat a different disease than indicated in the label would not be consistent.[196] The guidance further states that promotional representations must be “grounded in fact and science and presented with appropriate context.”[197]

Despite these requirements, the guidance still relaxes restrictions on off-label promotion somewhat. While insisting that promotional information have some supporting evidence, the guidance permits drug and device companies to utilize evidence that is insufficient to satisfy FDA approval standards.[198] The guidance also does not explicitly bar inconsistent promotional communications but instead deems them outside the scope of the recommendations.[199] This perhaps suggests that FDA may be marginally more lenient in its assessment of inconsistent promotional information.

Communication of Health Care Economic Information. FDA’s second guidance document also provides drug companies with significant leeway.[200] The guidance concerns the sharing of Health Care Economic Information (“HCEI”) with insurance companies and other payors.[201] HCEI is “any analysis . . . that identifies, measures, or describes the economic consequences . . . of the use of the drug.”[202] In the guidance, FDA authorizes drug manufacturers to disseminate HCEI as long as the information relates to the disease being treated or to a condition in the patient population that the drug’s label indicates can be treated by the drug.[203]

Like the first guidance document, the second explains that FDA will not object to certain communications of information about unapproved products and unapproved uses of approved products.[204] FDA provides several examples, including the information about the anticipated timeline for possible FDA approval, product pricing information, and factual presentations of results from studies.[205] In allowing these communications regarding off-label uses of a product, the guidance emphasizes that payors do not need protection in these exchanges because they are sophisticated audiences that can closely scrutinize a range of HCEI.[206]

Draft Guidance on Presentation of Efficacy Data. Citing research that suggests consumers have improved comprehension and recall of efficacy and risk information when it is presented quantitatively, FDA also issued draft guidance on the presentation of quantitative efficacy and information in direct-to-consumer promotional labeling and advertisements.[207] FDA’s guidance provided recommendations in four categories:

- presenting probability information,

- formatting quantitative efficacy or risk information,

- using visual aids, and

- providing quantitative efficacy or risk information for treatment and control groups.[208]

In the first category, FDA recommended expressing efficacy and risk probabilities in terms of absolute frequencies (such as 57 in 100 or 57%) versus relative frequencies (i.e. 33% reduction in risk) to improve consumer comprehension.[209] As to the second, FDA recommended presenting information in consistent numerical formats and probabilities using whole numbers.[210] Third, FDA endorsed the use of visual aids as a way to help consumers understand efficacy and risk probabilities, so long as they clearly explain the information displayed, are proportionate to the numbers that they are representing, and include representations of both numerators and denominators for numerical ratios.[211] Finally, FDA recommended providing quantitative information for both treatment and control groups to improve consumer understanding of efficacy.[212]

D. Legislative Developments Pertaining to Promotional Issues

There was little to report in the realm of legislative activity relating to drug and device promotional activity in 2018. Federal legislation we have discussed previously in these pages, for example, remained stagnant. The Pharmaceutical Information Exchange Act, which would effectively codify FDA guidance on HCEI by giving drug and device manufacturers greater freedom to share economic information regarding unapproved products, remains a draft bill stalled in the House Energy and Commerce Committee.[213] After holding a consideration and mark-up session, the Subcommittee on Health forwarded the bill to the full House Energy and Commerce committee on January 17, 2018. Since then, the bill has not advanced.[214] Similarly, the draft bill of the Medical Product Communications Act of 2017, which would enable manufacturers to discuss certain off-label information with health care providers, remains in the House Energy and Commerce Subcommittee on Health.[215]

E. Litigation Relating to Promotional Issues

In May 2018, the United States Supreme Court considered two recent FCA off-label promotion cases but ultimately denied certiorari.[216] In 2017, the Fifth and Sixth Circuits had dismissed the cases, United States ex rel. King v. Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and United States ex rel. Ibanez v. Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., in part, in the former case, because the plaintiffs failed to demonstrate at the summary judgment stage that off-label promotion caused physicians and pharmacies to make false claim submissions to the government.[217] With the Supreme Court refusing to hear either case, for the time being plaintiffs will continue to face challenges in pleading and proving causation in FCA off-label promotion cases.

IV. DEVELOPMENTS IN CGMP REGULATIONS, QUALITY SYSTEM REGULATIONS, AND OTHER MANUFACTURING ISSUES

During 2018, we saw robust enforcement efforts relating to purported cGMP and Quality System regulation (“QSR”) violations. In particular, FDA continues to crack down on manufacturing, quality, and data integrity issues and this year issued a number of notable Warning Letters. These developments, as well as final guidance related to data integrity and compounding pharmacies, among other issues, are discussed below.

A. Notable cGMP Enforcement Activity

In 2018, DOJ announced two notable consent decrees of permanent injunction entered by federal district courts against drug manufacturers to stop the distribution of unapproved, misbranded, and adulterated drugs. This is consistent with DOJ’s publicized enforcement priorities. Notably, in December, Deputy Assistant Attorney General James Burnham gave a speech where he explained that compounding pharmacies “are an increasing focus of enforcement efforts” and “a major enforcement priority” for DOJ and FDA, and highlighted the potential of enforcing cGMP violations as FCA cases.[218] These comments highlight the importance of this recent guidance from FDA for compounding pharmacies.