August 14, 2019

Halfway through 2019 and the third year of the Trump Administration, we continue to observe complex trends in the health care regulatory and enforcement environment impacting providers. The Trump Administration continues to aggressively pursue its high priority initiatives, such as combatting the opioid crisis and reducing health care costs, through various measures extending to many types of providers. And the U.S. Department of Justice (“DOJ”) continues to pursue and announce significant civil and criminal enforcement actions against health care providers. But in certain other ways, the government has also signaled a softening of its health care enforcement agenda. For example, DOJ has taken a more aggressive approach to reining in non-meritorious qui tam suits brought under the False Claims Act, one of the government’s primary tools for enforcing the health care laws and recovering government health program funds. In a speech at the 2019 Advanced Forum on False Claims and Qui Tam Enforcement earlier this year, Deputy Associate Attorney General Stephen Cox described the DOJ as a “gatekeeper” against frivolous or even low-value qui tam cases, and stated that DOJ attorneys have been instructed to consider dismissal when a qui tam case is not in the government’s interest.[1] This shift in tone is further reflected in the issuance of recent guidance and Justice Manual revisions, discussed in more detail below, that incentivize cooperation and voluntary disclosure by entities under investigation in False Claims Act cases, suggesting a more collaborative, thoughtful, and less rigid overall enforcement approach.

Consistent with this shift, the overall number of DOJ and U.S. Department of Health and Humans Services (“HHS”) resolutions involving health care providers, while still reflecting historically high levels of recoveries, continues to decrease from its peak during the Obama Administration. HHS similarly saw a decrease in enforcement efforts against health care providers, continuing the downward trend we’ve observed since 2017. However, opioid enforcement efforts are unwavering, and we continue to see substantial civil and criminal cases being brought against a variety of health care entities as part of combating the opioid crisis. We review recent opioid-related enforcement actions and other health care enforcement developments below. Additionally, we provide updates on other HHS activity, including efforts surrounding conscience and religious freedom protection as they pertain to health care providers.

Also addressed in this update are recent case law developments particularly salient to health care providers, including several related to False Claims Act interpretation and application and continued litigation regarding the Affordable Care Act. Finally, we discuss recent developments related to the Anti-Kickback Statute (“AKS”) and the Stark Law, key statutory schemes for health care provider compliance.

A collection of recent publications and presentations on health care issues impacting providers is available on our website. As always, we are eager to discuss these recent developments, and their relevance to your business, with you.

I. DOJ Enforcement Activity

A. False Claims Act Enforcement Activity

Between January 1 and June 30, 2019, the DOJ announced approximately $645 million in FCA recoveries from settlements with health care providers. This figure is more than triple the DOJ’s recovery of $201 million from settlements from January 1 through June 30, 2018, but it still marked a reduction from the $817 million the DOJ recovered during the same period of 2017.[2] The DOJ’s significant recovery during the first half of 2019 can likely be attributed to the fact that the DOJ reached several particularly large resolutions with providers during this period, including one $269 million settlement and four others over $35 million each. Of note, however, the 33 total health care provider settlements the DOJ announced during the first half of 2019 fell below the 40 health care provider settlements it announced during the first half of 2018 and considerably below the 54 health care provider settlements the DOJ announced during the first half of 2017.[3]

The DOJ’s lower count of health care provider settlements during the first half of 2019 could reflect the shift in enforcement tone at the top, except that the amount of recoveries reflected in those settlements have been at historic highs: the DOJ’s average FCA settlement against a health care provider in the first half of 2019 was $19.5 million, nearly four times the average provider settlement the DOJ recovered against health care providers during the same time period last year.[4] Even excluding from this calculation the DOJ’s largest provider settlement of the period—an outlier $269 million settlement in January—the average settlement with a health care provider in the first six months of 2019 was still more than twice the average settlement reached during the same period last year.[5] Consistent with the DOJ’s new approach to using its dismissal authority for more declined qui tams, these numbers could reflect an attempt to put the government’s resources into higher-value cases.

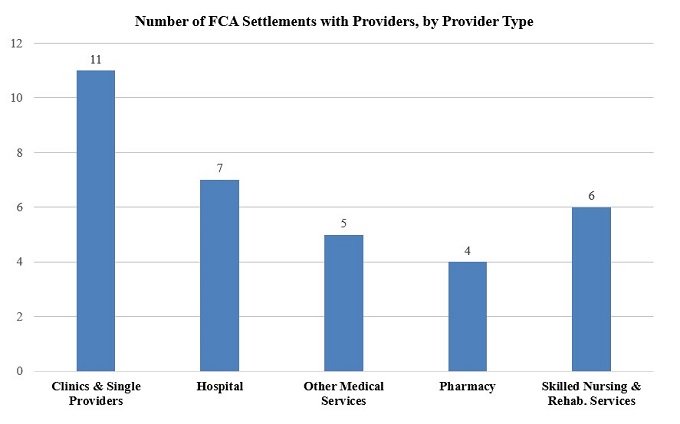

The FCA settlements the DOJ has announced this year featured many of the same legal theories the government has used to support actions against providers in years past. Also as in prior years, the DOJ’s provider settlements in the first six months of 2019 featured actions against a wide range of types of providers, including hospitals, clinics and single providers, providers of skilled nursing and rehabilitation services, and pharmacies. The DOJ also announced several settlements with entities we’ve classified as providers of “other” medical services, such as providers of medical records software. It remains to be seen whether this data point is an anomaly or whether it marks an increasing focus by the DOJ on providers of medical technology as the health care field continues to digitize and undergo technological innovation.

As indicated in the chart above, during the first half of 2019, most FCA settlements with health care providers involved clinics and single providers as in years past. However, during the first half of 2019, the DOJ also completed numerous settlements with hospitals and entities providing skilled nursing and/or rehabilitation services. Unlike health care provider settlements from the same period of 2018, the vast majority of which involved clinics and single providers, settlements from the first half of 2019 were more evenly spread across provider types.[6]

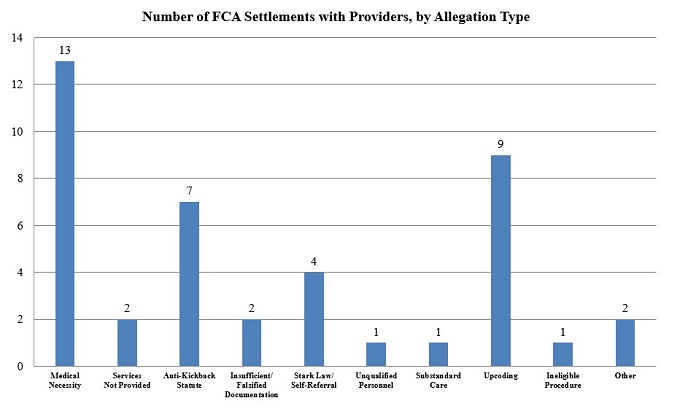

Continuing the trends of the recent past, the most prevalent legal theory among health care provider settlements in the first half of 2019[7] was the theory that providers defrauded the government by billing for services that lacked the medical necessity required by government health programs. The DOJ announced these settlements in roughly a half dozen different jurisdictions around the country, revealing that it had again used this theory in cases against providers of various stripes.

Aside from cases involving medically unnecessary procedures or services, the first six months of 2019 also revealed a jump in the number of settlements involving allegations of “upcoding”—where an entity allegedly assigns billing codes for more expensive medical procedures or treatments, or for services of a greater quantity or duration, than it actually provided its patients in order to increase the amount of reimbursement. While only two settlements in 2018 featured upcoding allegations,[8] nine settlements from the first half of 2019 contained allegations of this kind. Indeed, through one enforcement action in the Northern District of Illinois against multiple health care providers of skilled nursing services accused of increasing their Medicare reimbursements through upcoding, the DOJ obtained six separate settlements totaling nearly $10 million.[9]

Notably, by far the largest average source of recovery for the DOJ in the first half of 2019 were those settlements with providers involving allegations of either AKS and/or Stark Law violations. Although comprising just eight of the DOJ’s 33 settlements with providers during this period, actions involving allegations of AKS and/or Stark Law violations featured average settlement amounts of just over $22 million. All but three involved qui tam lawsuits.

In general, the first half of 2019 featured many large, headline-grabbing settlement amounts. One of the top resolutions, announced in January, was a settlement with a pathology laboratory company resolving allegations of giving subsidies for electronic health records systems (“EHR”) and free and/or discounted consulting services to physicians who referred patients to the lab in violation of the AKS and the Stark Law. [10] As United States Attorney Maria Chapa Lopez of the Middle District of Florida stated in the press release announcing the settlement, “[p]atients deserve the unfettered, independent judgment of their health care professionals. Offering financial incentives to physicians and medical practices in exchange for referrals undermines citizens’ trust in our health care system[.]”[11] The pathology laboratory agreed to pay $63.5 million to settle these allegations.[12]

Another top provider settlement from the first half of 2019 was the DOJ’s $57.5 million settlement in February with an EHR vendor, an emerging theme in DOJ resolutions. This settlement resolved allegations that the vendor had caused users of its EHR systems to submit false claims under federal healthcare programs after misrepresenting the nature of what its EHR product could do and providing unlawful remunerations to entice users to recommend its product.[13] As part of the settlement, the company agreed to enter into an “innovative” five-year Corporate Integrity Agreement requiring it to retain an Independent Review Organization to assess the company’s software quality control and compliance systems and to periodically review the company’s dealings with health care providers for compliance with the AKS.[14] Announcing the settlement and Corporate Integrity Agreement, United States Attorney Christina E. Nolan for the District of Vermont stated that going forward her office would be “unflagging in [its] efforts to preserve the accuracy and reliability of Americans’ health records and guard the public . . . against corporate greed.” Per U.S. Attorney Nolan, “EHR companies should consider themselves on notice.”[15] Other actions against EHR vendors in recent years, such as DOJ’s $155 million recovery against an EHR software vendor in 2017, discussed in detail in our 2017 Mid-Year Update,[16] underscore this warning.

B. Case Law Updates

1. False Claims Act Developments

a) Statute of Limitations Clarified

In the first half of 2019, courts have ruled on questions presented in several cases of concern for health care providers. Most notably, on May 13, 2019, the Supreme Court addressed a circuit split relating to the FCA’s statute-of-limitation tolling provisions, 31 USC § 3731(b).[17] The FCA requires that an action be brought by the later of (1) six years after the alleged FCA violation or (2) three years after the date when facts material to the right of action are known or reasonably should have been known by the official of the United States charged with responsibility to act in the circumstances, but no later than 10 years after the alleged violation.[18] As we previewed in our 2018 Year-End Update, at issue in Cochise Consultancy Inc. v. United States, ex rel. Hunt was whether the latter provision, 31 U.S.C. § 3731(b)(2), applies in qui tam cases in which the government does not intervene, and if so, whether the relator’s knowledge of the facts relevant to the alleged FCA violation is sufficient to trigger the three-year period.[19] In the decision on appeal to the Supreme Court,[20] the Eleventh Circuit found that it does, and the relator’s knowledge is not sufficient to trigger the limitations period.[21] Other circuits had found that the provision does not apply to qui tam suits in which the U.S. does not intervene[22] or, if it does, the limitations period begins when the relator has knowledge of the facts giving rise to the alleged FCA violation.[23]

The Court affirmed the Eleventh Circuit’s decision, finding based on the plain language of the statute that (1) the longer limitations period of section 3731(b)(2) was available to qui tam relators even if the government declined to intervene in the case, and (ii) the three-year limitations period began when the government—not the relator—had actual or constructive knowledge of the fraud allegations.[24]

This decision will have substantial implications for providers and the FCA bar: following this ruling, some qui tam relators may have up to ten years from the date of the alleged violation to bring suit under the FCA. We will continue to monitor lower court applications of this decision and report back in future updates.

b) Public Disclosure Bar Updates

The FCA’s public disclosure bar requires dismissal of qui tam suits based on information that has already been “publicly disclosed” unless the relator is an “original source” of the information.[25] In 2010, the FCA was amended to provide that a relator may qualify as an original source, even regarding an alleged FCA violation that has been publicly disclosed, if the relator’s knowledge is “independent of and materially adds” to the information in the public domain.[26] The Tenth Circuit recently weighed in on the meaning of “materially adds” in United States ex rel. Reed v. KeyPoint Government Solutions.[27] Adopting a standard set forth by the First Circuit, the court held that new information that is “sufficiently significant or important that it would be capable of ‘influenc[ing] the behavior of the recipient’—i.e., the government—” satisfies the materially-adds standard, whereas “background information or details about a known fraudulent scheme” typically will not.[28] In this particular case, the court found that relator’s information identifying individuals and an entity allegedly involved in a worthless services scheme did not materially add to publicly disclosed information because they provided only additional color.[29] Relator’s allegations regarding an additional scheme and the supervisors’ attempts to conceal it, however, materially added to the publicly disclosed information because her “allegations had the effect of ‘expanding the scope of the fraud’ revealed in the public disclosures and introducing ‘knowledge of scienter that is not specifically contained in a qualifying public disclosure.’”[30]

In reaching this conclusion, the Tenth Circuit rejected differing interpretations of “materially adds” adopted by the Seventh and Third Circuits. The Seventh Circuit assesses whether the relator’s allegations are “substantially similar” to the public source information; the Tenth Circuit found this test conceptually indistinct from the inquiry that requires a court to assess whether the relator is an original source to begin with—whether the relator’s allegations are “substantially the same” as those publicly disclosed under 3730(e)(4)(A).[31] The Third Circuit requires that the relator provide information “that adds in a significant way to the essential factual background: ‘the who, what, when, where and how of the events at issue.’”[32] The Tenth Circuit found this interpretation insufficiently case-specific. For example, in a case such as the one before the Tenth Circuit, where “the publicly disclosed fraud exists within an industry with only a few players, a relator who identifies a particular industry actor engaged in the fraud (i.e., the ‘who’) is unlikely to materially add to the information that the public disclosures had already given the government.”[33]

c) Developments in Implied False Certification Theory

We have long been reporting on interpretive difficulties faced by the lower courts following the Supreme Court’s 2016 decision in Universal Health Services, Inc. v. United States ex rel. Escobar.[34] That decision adopted the implied false certification theory of FCA liability; it also set forth new requirements for proving that the false statement was “material” and made with scienter.[35] In our 2018 Year-End Update, we describe the widening circuit splits relating to the interpretation of both elements.

The Supreme Court has been asked repeatedly to resolve these circuit splits and clarify the meaning of materiality and scienter. However, in the first half of the year the Court denied five petitions for certiorari that presented the opportunity, including one we reported on at the end of 2018: Brookdale Senior Living Communities, Inc., v. United States ex rel. Prather.[36] The Supreme Court’s silence perpetuates uncertainty for providers, who must grapple with conflicting standards across the circuits. We will continue to report on post-Escobar developments in future updates.

d) Scrutiny of Government Dismissal of AKS Qui Tam Cases

A cluster of twelve related qui tam actions filed in eight district courts by the same relator are pushing courts to consider the standard of review applicable to government motions to dismiss qui tam actions. Under the FCA, even where the government declines to intervene, it “may dismiss the action notwithstanding [the relator’s] objections” if the relator receives notice of the government’s motion to dismiss and an opportunity for a hearing.[37] However, the statute does not supply a standard for adjudicating these dismissals, and the courts of appeal are split on the standard to apply. The D.C. Circuit holds that the provision “give[s] the government an unfettered right to dismiss an action” that, like a government decision not to prosecute a case, is presumptively “unreviewable.”[38] The Ninth and Tenth Circuits, by contrast, apply a burden-shifting test: if the government demonstrates a “valid government purpose” for dismissing the case and a “rational relation between dismissal and accomplishment of the purpose,” then the burden shifts to the relator to show that the government’s dismissal is “fraudulent, arbitrary and capricious, or illegal.”[39]

As discussed in our prior updates, in a January 2018 memo, Michael D. Granston, the Director of the DOJ’s Civil Fraud Section, Commercial Litigation Branch, indicated that the DOJ would take a more active role in curbing meritless qui tam actions by encouraging government attorneys to dismiss suits that appear meritless or likely to strain government resources.[40] Since the release of the Granston Memo, the DOJ has cited its principles in petitioning for dismissal,[41] and the courts have continued to grapple with the relevant standard applicable to these dismissals.

The impact of this circuit split has become particularly clear in courts’ review of DOJ motions to dismiss claims predicated on essentially identical allegations made by one relator against pharmaceutical companies in twelve different cases. Relator alleges that the pharmaceutical companies engaged in three different AKS-violating schemes to induce additional prescriptions of their drugs: (1) “free nursing services” offered to induce prescriptions, (2) sending paid nurse educators to prescribers who purported to provide independent advice but in fact marketed defendants’ products, and (3) “reimbursement support services” offered to induce prescriptions.[42]

In an April 2019 decision, a District Court in the Southern District of Illinois denied the government’s motion to dismiss a declined FCA case predicated upon an AKS violation.[43] Applying the burden-shifting standard for reviewing government dismissals of qui tam actions adopted by the Ninth and Tenth Circuits,[44] the court held that the government “failed to fully investigate the allegations against the specific defendants in [the] case” and failed to “assess or analyze the costs it would likely incur versus the potential recovery that would flow to the government if [the] case were to proceed.”[45] Accordingly, the court held that the government’s investigation “falls short of a minimally adequate investigation to support the claimed governmental purpose” for the dismissal, which was the avoidance of litigation costs.[46] The district court also noted that “the Government devoted a significant portion of its briefing – 6 ½ pages and all exhibits – to deriding the relator’s business model and litigation activities” and that the government contended, during the dismissal hearing, that “disapproval of ‘professional relators’ is a valid governmental purpose for dismissal.”[47] Under these circumstances, the court found that “one could reasonably conclude that the proffered reasons for the decision to dismiss are pretextual and the Government’s true motivation is animus towards the relator.”[48]

Conversely, a magistrate judge in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Texas upheld the government’s dismissal of two FCA claims predicated upon AKS violations.[49] Rather than adopt the Ninth and Tenth Circuit’s burden-shifting test to government dismissals, the magistrate judge adopted the D.C. Circuit’s view that the government has an “unfettered right” to dismiss qui tam cases.[50] In the alternative, however, the magistrate judge concluded that even under the burden-shifting standard adopted by the Ninth and Tenth Circuits, the relator’s claim should be dismissed. The magistrate judge found that the government’s stated purpose for dismissing the case – avoiding litigation costs – was valid and rationally related to the dismissal, relying in part on the government’s assertion that “DOJ attorneys in the Civil Division’s Fraud Section have collectively spent more than 1,500 hours” on relator’s cases.[51] The magistrate judge also rejected the relator’s claim that the government’s investigation was inadequate and found that the government was not obligated to present evidence of a cost-benefit analysis to justify its decision to dismiss.[52]

As these cases continue to percolate through the district courts and up to the courts of appeal, we expect additional circuits will weigh in on the standard applicable to government dismissals of qui tam claims.

2. Affordable Care Act Developments

First, as we reported in our 2018 Year-End Update, a federal district court in Texas recently struck down the Affordable Care Act (“ACA”), holding that the ACA’s individual mandate provision will no longer be a valid exercise of congressional taxing power when the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 eliminates the mandate’s tax penalty in 2019, and that the remainder of the Act is not severable.[53] A coalition of Democratic attorneys general who intervened as defendants in the Texas case have appealed to the Fifth Circuit.

In the district court, the DOJ did not defend the constitutionality of the individual mandate, but it argued that the remainder of the Affordable Care Act was severable and, therefore, should remain standing even if the individual mandate were invalidated. Before the Fifth Circuit, however, the DOJ now argues that the individual mandate is not severable and the district court’s opinion should be affirmed in full.[54] If the Fifth Circuit agrees and the decision is not overturned by the Supreme Court, the decision could have much further-reaching ramifications than just the ACA’s well-known health exchange and individual mandate provisions, such as invalidating an array of ACA regulatory and enforcement provisions relating to drug pricing, Medicare payments, and AKS amendments. Oral arguments were heard before a Fifth Circuit panel on July 9, 2019; we will update you on the status of this development in our 2019 Year-End Update.

Second, on June 24, 2019, the Supreme Court agreed to hear a dispute relating to specific provisions of the ACA that establish insurer incentives to offer exchange coverage.[55] Under the ACA’s risk corridors program, if insurers’ claims costs exceeded the premiums collected in benefits years 2014 through 2016, “the Secretary [of HHS] shall pay” an amount set by a statutory formula designed to compensate insurers for their losses.[56] However, in appropriations legislation for the 2015 fiscal year, Congress included a rider prohibiting HHS from making risk corridor program payments to insurers with the appropriated funds. When HHS failed to make these risk corridor payments, three insurers sued in the Court of Federal Claims. The insurers claim that HHS owes all insurers, including appellants, over $12 billion. In fact, one of the appellant insurers contends that it became insolvent in 2016 because it relied on risk corridor payments that never materialized in setting its premiums.[57] Although one insurer prevailed in the lower court, on appeal the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit found HHS had no obligation to pay the insurers because “Congress suspended the government’s obligation” to make risk corridor payments “through clear intent manifested in appropriations riders.”[58] The insurers’ petition for certioriari was granted by the Supreme Court, which will hear the case next term.

C. Opioid Crisis Enforcement and Updates

Combatting the opioid epidemic remains a top priority for the DOJ. In 2018, the DOJ announced the expansion of its Medicare Fraud Strike Force, the formation of an Appalachian Regional Prescription Opioid (“ARPO”) Strike Force to target the “medically unnecessary prescription and dispensing of opioid-based controlled substances by licensed medical professionals across the region,”[59] and a 28 percent increase in the number of defendants charged with federal opioid-related crimes. This year, the DOJ’s enforcement efforts remain robust: in the first half of 2019, the DOJ brought charges against 62 medical professionals and eight other individuals involved in prescribing or filling prescriptions for opioids. As further demonstrated by the developments described below and throughout this update, DOJ continues to prioritize opioid-related issues in its enforcement and prosecution efforts against defendants ranging from manufacturers and prescribers to testing companies and treatment centers.

Most significantly, on April 17, 2019, the DOJ announced charges against 60 individuals involved in opioid distribution, including 53 medical professionals, across 11 districts, brought by the ARPO Strike Force.[60] HHS Secretary Alex Azar explained in connection with the announcement that “[r]educing the illicit supply of opioids is a crucial element of President Trump’s plan to end this public health crisis.”[61] Many of these indictments allege that providers issued prescriptions for opioids and other controlled substances without a legitimate medical purpose and outside the scope of professional practice in violation of the Controlled Substances Act. For example, indictments allege that providers signed blank prescriptions, did not examine patients or conducted inadequate examinations, ignored or did not conduct drug screens, and ignored or failed to monitor for signs of addiction.[62] Some of the healthcare providers were also charged with criminal health care fraud for issuing medically unnecessary opioid prescriptions that were filled and reimbursed by Medicaid, Medicare, or Tricare.[63]

DOJ has been pursuing opioid-related cases against a variety of health care providers. In May of this year, DOJ announced a settlement with a provider of behavioral healthcare services that resolved allegations involving seven of the provider’s West Virginia-based addiction treatment centers.[64] Specifically, the suit alleged that the facilities would send urine and blood analysis tests to an out-of-state lab, pay out of pocket for the tests, and then bill Medicaid for the services; Medicaid reimbursed the centers far more than the amounts charged by the lab.

The DOJ’s Prescription Interdiction & Litigation (“PIL”) Task Force also brought a “first of its kind action” and obtained a temporary restraining order (“TRO”) to prevent two pharmacies in the Middle District of Tennessee, their owner, and three pharmacists from filling prescriptions for opioids.[65] In a complaint unsealed in February 2019, the DOJ alleges that the pharmacy and pharmacists filled prescriptions despite “red flags” that the medications were being diverted or abused, then falsely billed Medicaid for the prescriptions. For example, patients filled prescriptions for unusually high dosages of oxycodone and other opioids, in dangerous “cocktails” known to have a “synergistic” effect, paid cash, and travelled extremely long distances to fill prescriptions.[66] The DOJ seeks permanent injunctive relief and monetary penalties. In May 2019, the PIL Task Force announced a second TRO issued by the Northern District of Texas against two physicians who allegedly prescribed opioids despite similar “red flags” of abuse in violation of the Controlled Substances Act.[67]

The Medicare Fraud Strike Force announced charges against three opioid prescribers in the first six months of 2019. Most recently, on June 25, 2019, it announced the indictment of a New Jersey physician on five counts of AKS violations for allegedly accepting kickbacks from an opioid manufacturer in exchange for writing medically unnecessary opioid prescriptions.[68] In March 2019, a Regional Medicare Fraud Strike force filed an information against a physician in the Eastern District of Pennsylvania charging him with eight counts of violating the Controlled Substances Act for improper opioid prescriptions.[69] The physician pleaded guilty to all eight counts ten days later; he will be sentenced in September 2019.[70] In April 2019, the Medicare Fraud Strike Force filed a two-count information against an Eastern District of Louisiana physician for conspiring to distribute controlled substances and conspiring to defraud Medicare and Medicaid for prescribing unnecessary opioid prescriptions.[71] The physician pleaded guilty in May 2019 and will be sentenced this September.[72]

One additional individual was sentenced this year for charges brought in 2018 by the Medicare Fraud Strike Force in the Southern District of Florida. The pain-management clinic owner was sentenced to 78 months’ imprisonment and agreed to repay approximately $1.4 million in proceeds obtained from opioid prescriptions falsely billed to Medicare.[73] The DOJ has also engaged in substantial prosecution efforts against opioid manufacturers, to be detailed further in our upcoming 2019 Mid-Year Update (Drugs and Devices).

Consistent with DOJ’s opioid enforcement efforts, thus far this year there have been six civil monetary penalty cases (“CMPs”) assessed by HHS OIG[74] against providers who allegedly sought Medicare reimbursement for specimen validity testing (“SVT”).[75] SVT is, in HHS OIG’s words, “a quality control process that evaluates a urine drug screen sample to determine if it is consistent with normal human urine and to ensure that the sample has not been substituted, adulterated, or diluted.”[76] According to HHS OIG, SVT is “not a separately billable Medicare‑covered service” if used to determine whether a urine sample has been adulterated, whereas use of the test for diagnostic or treatment purposes may be reimbursable.[77] Significantly, five of these six CMP assessments involved providers in Kentucky and Ohio,[78] two states that HHS OIG identified in April 2019 as focal points of the opioid crisis.[79]

D. DOJ Guidance

Consistent with the shift, evidenced by DOJ’s movement toward dismissing qui tam actions, that we observed in the wake of the Granston Memo and described above, this spring the DOJ announced two sets of new guidance that may mark a further softening in the DOJ’s approach to companies who proactively address potential FCA issues. As described at greater length below, the DOJ’s new cooperation guidelines in civil FCA matters roll back the “all or nothing approach” to cooperation laid out in the Yates Memo of 2015 and give DOJ attorneys greater “flexibility to accept settlements that remedy the harm and deter future violations.”[80] The DOJ’s criminal division also announced new guidance designed to provide “additional transparency” into how the DOJ evaluates company compliance programs.[81] As noted by Assistant Attorney General Brian A. Benczkowski in announcing the new guidance, “if done right” a well-designed compliance program “has the ability to keep the company off our radar screen entirely.”[82]

1. Civil Division Guidance on Cooperation

On May 7, 2019, the DOJ announced new guidance on cooperation: “Guidelines for Taking Disclosure, Cooperation, and Remediation into Account in False Claims Act Matters.”[83] This guidance follows the DOJ’s November 2018 announcement that it was revising its cooperation policies because the “all or nothing approach to cooperation” introduced in the Yates Memo and requiring companies to identify all individuals responsible in underlying misconduct to receive any cooperation credit “was counterproductive in civil cases.”[84] The guidance, incorporated into the Justice Manual and described in detail in our client alert, explains how DOJ will award credit for cooperation and remedial measures in resolving FCA cases. The guidelines emphasize voluntary self-disclosure of misconduct unknown to the government. However, they also provide for credit for steps such as preserving and disclosing documents “beyond existing business practices or legal requirements;” identifying individuals aware of, or involved in, potential misconduct; and “[a]ssisting in the determination or recovery of the losses caused by the organization’s misconduct.”[85]

To earn “maximum credit,” an entity or individual should “undertake a timely self-disclosure that includes identifying all individuals substantially involved in or responsible for the misconduct, provide full cooperation with the government’s investigation, and take remedial steps designed to prevent and detect similar wrongdoing in the future.” The guidance provides that the minimum possible penalty, after the award of maximum cooperation credit, is “full compensation for the losses caused by the defendant’s misconduct (including the government’s damages, lost interest, costs of investigation, and relator share).”[86] In a May 20, 2019 speech, Principal Deputy Associate Attorney General Claire McCusker Murray stated that the guidelines provide the DOJ’s enforcement attorneys with “significant flexibility” to credit cooperation.[87]

2. Criminal Division Guidance on Corporate Compliance Programs

This past April, the DOJ’s Criminal Division issued updated guidance regarding corporate compliance programs.[88] The guidance expands upon the Criminal Fraud Section’s February 2017 guidance, and aims to “better harmonize the guidance with other Department guidance and standards while providing additional context to the multifactor analysis of a company’s compliance program.”[89]

Among the guidance’s notable features is its focus on providing examples of specific factors DOJ considers in evaluating compliance programs. For example, the guidance discusses the importance of “risk-tailored resource allocation” and ensuring that companies focus their energies on monitoring high-risk practices and transactions.[90] Likewise, the guidance instructs prosecutors to consider whether a company’s assessment of its own risk landscape is “current and subject to periodic review,” and whether lessons learned from periodic re-assessments are being incorporated into the company’s policies and procedures.[91]

Other aspects of the guidance that are of particular relevance to health care providers are its instruction that prosecutors consider whether compliance trainings have been conducted “in a manner tailored the audience’s size, sophistication, or subject matter expertise,”[92] and its emphasis on effective implementation of compliance programs and on the extent to which senior management have demonstrated (not just stated) their commitment to compliance.[93]

This guidance and other statements provide helpful contours to health care providers in developing compliance programs consistent with best practices and the expectations of the DOJ.

II. HHS Enforcement Update

A. HHS OIG Activity

1. 2018 and 2019 Developments and Trends

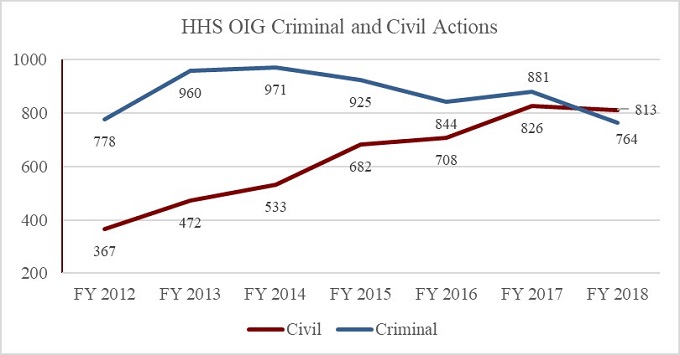

In the period between October 1, 2018, and March 31, 2019,[94] HHS OIG reported 421 criminal actions.[95] This marked a decrease of less than 1% from the 424 criminal actions HHS OIG reported in the first half of FY 2018.[96] The number of civil actions, however, declined more significantly as compared to the same period in the last two fiscal years. There were 331 civil actions in the first half of FY 2019, compared to 349 in the first half of FY 2018 and 461 in the first half of FY 2017.[97] FY 2018 saw the first year-over-year decrease in civil actions in the FY 2012 through FY 2018 period. Also of note, as the chart below shows, FY 2018 marked the first time in several years that the number of civil actions surpassed the number of criminal actions. We will report back on the final 2019 numbers and emerging trends at the end of this year.

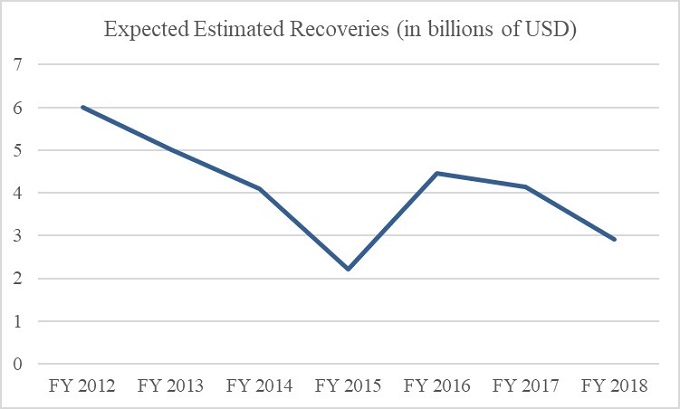

HHS OIG’s expected recoveries for the first half of FY 2019 were $2.3 billion, approximately 58% higher than in the same period in FY 2018.[98] The expected recoveries for the first half of 2019 already equal nearly 80% of the total investigative recoveries for all FY 2018,[99] suggesting that FY 2019 may mark a reversal in what has otherwise been a gradual decrease in overall expected recoveries since FY 2012. This trend is shown in the chart below. The high sum of expected recoveries thus far this year is likely due to several large settlements, including one $625 million False Claims Act settlement involving a pharmaceutical company.[100] This settlement alone equals nearly half of the approximately $1.32 billion in settlements with pharmaceutical companies highlighted in HHS OIG’s year-end reports for FY 2014 through FY 2017.[101]

2. Significant HHS OIG Enforcement Activity

a) Exclusions

HHS is required to exclude from participation in the federal health care programs any individual or entity that is convicted of (1) a crime related to Medicare or state health care program, (2) a crime related to patient abuse or neglect, (3) felony health care fraud, or (4) a felony related to the manufacturing, distribution, prescription, or dispensing of a controlled substance.[102] HHS also has permissive authority to exclude individuals and entities falling into sixteen other categories, including those convicted of fraudulent conduct related to health care, those excluded or suspended from a federal or state health care program, and those HHS determines have paid kickbacks as defined by the AKS.[103]

HHS OIG reported 1,440 exclusions from the federal health care programs in the first half of calendar year 2019.[104] Of that number, 18 exclusions were of entities rather than individuals, a 40% drop compared to the same period in calendar year 2018[105] and a 55% drop compared to the same period in calendar year 2017.[106] Of these entities, six were physician practices, two were home health agencies, and the remaining ten were a mix of other types of providers.[107] No single provider category dominated the entity exclusions list.

The remaining 1,422 exclusions reported in the Exclusions Database for the first half of calendar year 2019 were of individuals, 173 of whom were classified as business owners or executives, and 116 of whom were classified as physicians.[108] Of the latter category, 56 were classified as family practitioners, pediatricians, internists, or general practitioners.[109] The remaining physicians practiced a mix of specialties, with psychiatry, pain management, neurology, cardiology, and anesthesiology dominating.[110]

b) Civil Monetary Penalties

The first half of calendar year 2019 witnessed a significant downturn in both the number of civil monetary penalty (“CMP”) cases and the value of CMP settlements, as compared with the same period in 2018. Whereas in the first half of 2018 HHS OIG announced 61 CMPs totaling approximately $46 million,[111] in the first half of 2019 there were only 37 CMPs totaling only about $17 million.[112] This equates to a 39% decrease in the number of cases, and a 63% decrease in the total recovery amount.

However, the CMP settlements from the first half of the year shared some characteristics with prior settlements. As in the first half of 2018, CMPs resulting from self-disclosures represented the lion’s share of the CMPs in terms of dollar value, at 82%. Thirty of the CMP cases settled for amounts under $500,000, with the remaining seven settlements accounting for 78% of the total dollar amount recovered. As in prior years, cases involving allegations of improper or false billing accounted for the bulk of the CMPs recovered—approximately $10.7 million across 17 cases. Six cases imposing a total of approximately $5.5 million in CMPs involved kickback allegations, representing approximately 32% of the total CMP recoveries by dollar value compared with only about 19% for the same period last year. In the first half of this year, there were also thirteen cases involving employment of individuals excluded from participation in the federal health care programs, though those settlements totaled less than $842,000.

The three largest CMPs assessed against providers in the first half of 2019 all involved self-disclosures and are summarized below:

- After making a self-disclosure to HHS OIG, on April 4, 2019, an Iowa-based health system settled allegations that it paid a physician excessive compensation that constituted illegal remuneration. As part of the settlement, the health system agreed to pay $3,008,326.50.[113]

- On April 3, 2019, after self-disclosing conduct to HHS OIG, a Mississippi-based medical group agreed to pay $2,022,904.96 to resolve allegations that it submitted claims for inpatient behavioral health services that were not medically necessary and that involved “cloning of documentation for multiple dates of treatment for the same patients and for multiple patients on the same dates of treatment.”[114]

- On January 9, 2019, after self-disclosing conduct to HHS OIG, a Texas county agreed to pay $4,526,740.26 to settle allegations that it submitted improper claims for ambulance transport services. The crux of HHS OIG’s allegations was that the county did not obtain the required beneficiary authorization for the transports.[115]

B. Significant CMS Activity

1. Transparency and Data Accessibility

As reported in past updates, the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (“CMS”) has continued to prioritize improving access to data related to the use of Medicare and Medicaid services. The Trump Administration has continued to explore a wide range of approaches to reducing health care costs, including by increasing patient access to the cost of their care and facilitating competition among providers to drive down costs. A number of recently proposed rules came out of that effort.

In February, HHS announced two proposed rules intended to “improve the interoperability of electronic health information” and “ensure patients can electronically access their electronic health information” by “increas[ing] choice and competition while fostering innovation that promotes patient electronic access to and control over their health information.”[116] One of the proposed rules, issued by CMS, would require Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, Medicare Advantage plans and Qualified Health Plans in Federally-facilitated exchanges to provide patients with immediate electronic access to medical claims and health information by the year 2020. In addition, the rule would require these plans to implement open data sharing technologies to facilitate patients changing plan types. CMS received nearly 2,000 public comments on the proposed rule before the comment period ended on June 3, 2019, and has not yet officially responded to the received submissions.[117]

2. Compliance Review Program

The CMS Division of National Standards announced last year that it is launching a Compliance Review Program “to ensure compliance among covered entities with HIPAA Administrative Simplification rules for electronic health care transactions.”[118] CMS piloted the program in 2018 with health plan and clearinghouse volunteers, and officially began the program in April 2019 by randomly selecting nine HIPAA-covered entities for Compliance Reviews. The review program uses a “progressive penalty process” to address noncompliance. For less serious violations, HHS works collaboratively with an entity to remedy the issue, including by issuing a Corrective Action Plan; for “willful and egregious” instances of noncompliance, the agency may assess more severe monetary penalties.[119]

3. CMS Guidance Regarding Co-Location of Hospitals and Health Care Facilities

On May 6, 2019, CMS issued draft guidance to state survey agency directors regarding permissible hospital co-location with other hospitals or health care facilities, which would amend a prior interpretation of the Medicare Conditions of Participation that prohibited such co-location.[120] Among other things, the new guidance would allow healthcare entities to be co-located on the same campus or within the same building—including sharing staff and/or services—while prohibiting entities from sharing patient care spaces (e.g. nursing stations, exam and procedure rooms, outpatient clinics, operating rooms, etc.). The public comment period for the draft guidance ended on July 2, 2019, and CMS has not yet officially responded to the comments or issued final guidance.

C. OCR Enforcement Efforts

1. HIPAA Enforcement

HHS’s Office of Civil Rights (“OCR”) has been increasingly active in recent years in pursuing alleged violations of the privacy and security patient information protections under the Health Information Portability and Accountability Act (“HIPAA”). OCR reported that as of June 30, 2019, it had received over 211,109 HIPAA complaints and initiated 971 compliance reviews since HIPAA privacy rules took effect in April 2003.[121] To date, OCR’s enforcement efforts have yielded $102,681,582 in settlements and civil penalties.[122]

In the first half of 2019, OCR reported only two settlements amounting to just over $3 million in fines for HIPAA violations.[123] In May, a diagnostic medical imaging services company agreed to pay $3 million to settle charges that it violated the HIPAA Security and Breach Notification Rules by allowing uncontrolled access to patients’ protected health information.[124] Later that month, a medical records service agreed to pay $100,000 to settle potential violations of the HIPAA Privacy and Security Rules by failing to conduct a comprehensive risk analysis prior to a data breach involving the protected health information of approximately 3.5 million patients.[125]

If OCR’s enforcement continues at this pace, 2019 will see a dramatic decline in HIPAA enforcement actions from last year, when OCR reported ten settlements and one judgment totaling $28.7 million in fines—the highest ever total recovery from HIPAA settlements and rulings.[126]

a) Developments in HIPAA Compliance Guidance

As noted in past updates, HHS continues to prioritize the protection of patients’ electronically stored confidential information. To that end, OCR issues cybersecurity newsletters “to help HIPAA covered entities and business associates remain in compliance with the HIPAA Security Rule by identifying emerging or prevalent issues, and highlighting best practices to safeguard [personal health information].”[127] The newsletters do not establish legally enforceable responsibilities or create safe harbors for companies that adhere to the guidance therein; rather, they outline recommendations for complying with the HIPAA Security Rule and highlight best practices to safeguard electronically stored confidential information.

The Spring 2019 newsletter focused primarily on “advanced persistent threats” (“APTs”), or long-term cybersecurity attacks consisting of continuous attempts to exploit weaknesses in a target’s information systems, as well as “zero day vulnerabilities,” or attacks that take advantage of a previously unknown hardware, firmware, or software vulnerability.[128] The newsletter notes that APTs are a particularly serious threat to the healthcare industry due to the value of medical research information, genetic data, experimental treatment testing results, and other individual health information. With respect to zero day vulnerabilities or exploits, the newsletter advises entities to implement appropriate safeguards, including encryption and access controls, and to ensure that measures are in place to assess the need for software patches and implement them in a timely manner.

2. Federal Conscience Protection Efforts

We are beginning to see the impact of the 2018 launch of OCR’s Conscience and Religious Freedom Division and enforcement efforts pertaining to this administration’s emphasis on conscience protection generally. In January, OCR sent a letter to the California Attorney General asserting that a California state law requiring pregnancy resource centers to post information about abortion services—which had recently been invalidated in court—violated the federal Weldon and Coats-Snowe Amendments, which prohibit state and local government recipients of certain federal funds from discriminating against providers who do not perform or refer for abortions.[129] After investigating complaints from several pregnancy centers, OCR’s Conscience and Religious Freedom Division concluded that California’s Reproductive Freedom, Accountability, Comprehensive Care, and Transparency Act (“FACT Act”) violates federal law by (1) requiring license covered facilities to refer for abortion and (2) discriminating against unlicensed covered facilities by targeting them for burdensome and unnecessary notice requirements when they fail to make arrangements for abortions. Following the Supreme Court’s decision in National Institute of Family and Life Advocates v. Becerra[130] in June 2018, a federal district court enjoined the state of California from enforcing the FACT Act against any pregnancy resource center in the state. As such, OCR is closing the complaint as favorably resolved for all complainants.

Similarly, in March, OCR issued a Notice of Resolution to the state of Hawaii after the state’s Attorney General took corrective action in response to an investigation regarding whether the state had discriminated against non-profit pregnancy resource centers.[131] Two pregnancy centers filed a complaint with OCR claiming that Hawaii had discriminated against them in violation of federal conscience laws by enacting notice requirements under Act 200, a law requiring pregnancy centers to disseminate notices promoting abortion. After OCR’s Conscience and Religious Freedom Division initiated an investigation, Hawaii’s Attorney General issued a memorandum indicating that the state will not enforce the notice provisions against any limited service pregnancy center. As such, OCR is closing the complaint as favorably resolved for all complainants.[132]

Further bolstering its conscience protection efforts, OCR issued a final conscience rule in May—after receiving over 242,000 submissions during the public comment period—aimed at protecting individuals and health care entities from discrimination on the basis of their exercise of conscience as part of HHS-funded programs.[133] Among other things, the final rule expands OCR’s authority to enforce 25 federal conscience protection laws and broadens the definition of “covered entity” to include state governments, federally-recognized tribes, hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, home health care providers, doctor’s offices, front desk staff, insurance companies, ambulance providers, pharmacists, pharmacies, and non-health employers that offer insurance to their employees. The new rule empowers OCR to use the full scope of its investigative and enforcement authority to pursue relevant claims and requires covered entities to cooperate with any such enforcement efforts, submit certifications of compliance to HHS, and maintain records of any such compliance.[134] Although the rule was originally scheduled to take effect on July 22, HHS has since agreed to postpone this date until November 22, at the request of a group of plaintiffs—including a coalition of 23 cities and states led by the New York Attorney General— in three related lawsuits challenging the rule’s legality.[135] We will continue to monitor these developments and report back on updates at the end of the year.

III. Anti-Kickback Statute Developments

The Anti-Kickback Statue remains one of the most important federal fraud and abuse laws applicable to providers. Given the connection between AKS violations and FCA liability – and the significant damages potentially at stake – it is perhaps unsurprising that the elements of an AKS violation remain actively contested in courts and that AKS-related regulatory developments are closely watched. Below, we discuss recent developments in AKS case law, prosecution of the largest health care fraud scheme ever charged, significant advisory opinions, and a relevant (but subsequently withdrawn) regulatory proposal.

A. Notable Case Law Involving the AKS

Judicial interpretation of “remuneration” continues to evolve as courts discuss whether remuneration includes anything of value, even when the relators could not show a quid pro quo relationship between remuneration and referrals. In United States ex rel. Charles Arnstein v. Teva Pharm. USA, Inc., the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York declared that a quid pro quo relationship between remuneration and referrals is not a requirement under the AKS. The case centered around the question of whether a pharmaceutical company’s promotional speaker program, which allegedly offered speaker fees and expensive meals in exchange for prescribing certain products, constituted an illegal kickback scheme.[136] The court denied summary judgment for defendants, declining to adopt their argument that plaintiff’s failure to demonstrate a quid pro quo relationship between speaker fees and future prescriptions written by the speakers “entitle[d] them to summary judgment.”[137] The court held that “offering or paying a person ‘remuneration’” with the intent of inducing the person to recommend a drug, was sufficient to constitute an AKS violation, even if the attempt did not succeed in securing referrals, stating that to conclude otherwise would be to ignore the difference between separate causes of action for “offer[ing] or pay[ing] unlawful remuneration” and 2) “solicit[ing] or receiv[ing] it.”[138]

A recent decision from the United States District Court for the Southern District of Texas narrowed the scope of AKS liability by requiring that the alleged remuneration flow directly to the person making the unlawful referrals.[139] The relator alleged that a health services company gave free items to elementary schools and transitional living shelters, and subsequently placed an independent contractor at each facility to provide “skills building services” through which patients were then referred to the company for mental health services.[140] The court held that because the independent contractor, not the organizations in receipt of the alleged remunerations, made the referrals, the relator failed to provide the “link” between the kickbacks and the inducement of referrals.[141]

B. Criminal AKS Prosecutions

In April of 2019, a federal jury found a South Florida nursing home facility owner guilty in “the largest health care fraud scheme ever charged” by the DOJ.[142] The prosecution alleged that from 1998 through 2016, the facility owner bribed doctors to refer patients to his skilled nursing care facility, where he would keep them for the maximum 100 days chargeable to Medicare, then transfer them to assisted living facilities before moving them back to the skilled nursing care facility to repeat the cycle.[143] In sum, the scheme involved $1.3 billion in fraudulent claims.[144] The facility owner allegedly used the proceeds to purchase luxury goods and pay bribes to secure his son’s admission at an Ivy League school.[145] The facility owner is appealing his conviction.[146]

C. Notable HHS OIG Advisory Opinions

The first half of 2019 proved to be a relatively quiet period for HHS OIG advisory opinions, with only three opinions released in the first six months of the year. The recent opinions, however, offer guidance for providers on important issues, namely the provision of waivers for cost-sharing amounts and arrangements promoting access to care. Below, we summarize two opinions of particular applicability to providers.

1. Cost-Sharing Waivers

On January 9, 2019, HHS OIG issued a favorable opinion regarding an arrangement by a charitable pediatric clinic to waive routine Medicare and Tricare cost-sharing amounts for pediatric patients who receive services not covered by Medicaid or another state insurance program.[147] HHS OIG determined that the arrangement did not fall under the cost-sharing waiver under the CMP Law because the clinic waives its cost-sharing amounts routinely and does not verify the financial need of all patients.[148] Nonetheless, HHS OIG determined that the arrangement presented a low risk of AKS violations because the clinic: (i) treats very few patients not covered by Medicaid or another state insurance program; (ii) does not offer waivers of cost-sharing amounts as part of an advertisement or solicitation; (iii) does not offer financial incentives to its health care providers to order unnecessary care or to steer patient referrals to requestor; (iv) serves an especially vulnerable patient population; and (v) demonstrated that it minimized the risk posed by the arrangement by implementing proper safeguards.[149] Though this favorable opinion contrasts with other instances in which HHS OIG has expressed concerns about arrangements involving routine waivers of cost-sharing amounts,[150] it is significant that (i) the number of Medicare beneficiaries who may benefit from this arrangement is very small, as it is limited to children with end-stage renal disease, and (ii) Tricare beneficiaries comprise less than one percent of the requestor’s patient population.[151]

2. Free In-Home Follow-up Care

On March 1, 2019, HHS OIG opined on an existing arrangement by a medical center to provide free, in-home follow-up care to eligible individuals with congestive heart failure, as well as a proposed expansion of the existing program to include individuals with chronic pulmonary disease.[152] Patients are eligible for the program if they, among other things, (i) have a high risk of readmission according to a medical assessment performed at the medical center and (ii) have arranged to receive follow-up care at the medical center. Under the terms of the program, eligible patients receive two free in-home follow-up care visits per week from a paramedic who, for instance, reviews the patient’s medication, performs a home safety inspection, and checks the patients vitals. When further care is needed, the paramedic directs the patient to follow up with his or her established provider.[153] Though the medical center typically is patient’s established provider, the program allows the patient to obtain care from the provider of his or her choice.[154]

HHS OIG determined that the program technically could generate prohibited remuneration because it only offered the free care to those patients planning to receive follow-up care from the medical center, and therefore could influence patients to select the medical center for federally reimbursable items or services.[155] Further, HHS OIG found that the Promotes Access to Care Exception did not apply because “the full suite of [s]ervices offered,” such as the home safety assessments, did more than promote patient access to care.[156] Nonetheless, HHS OIG declined to impose sanctions upon the medical center for several enumerated reasons specific to the requestor’s case.[157]

Notably, in the opinion, HHS OIG referenced the “broad reach” of the AKS and acknowledged that it can serve as a “potential impediment to beneficial arrangements that would advance coordinated care.”[158] HHS OIG also referenced back to its August 27, 2018 request for information which, as discussed in our 2018 Year-End Update, sought feedback about regulations that may act as “barriers to coordinated care” or “value-based care.” The request drew 359 public comments, but HHS has not yet published a proposed rule in response.

D. Regulatory Developments

On February 6, 2019, HHS OIG proposed a rule to narrow the existing regulatory discount safe harbor under the AKS and create two new safe harbors.[159] The rule was subsequently withdrawn on July 10, 2019. As proposed, the rule would have (1) excluded rebates provided to Medicare Part D plans, Medicaid managed care organizations (“MCOs”), and pharmacy benefit managers (“PBMs”) from the existing safe harbor protections and (2) added two new safe harbors, one to protect point-of-sale drug price reductions under specific circumstances, and the other to protect written, fair market value fixed-fee arrangements between PBMS and manufacturers.[160] During the comment period, over 25,000 comments poured in from manufacturers, pharmacies, health plans, and policy and advocacy groups.[161] While comments from pharmaceutical industry commenters were generally favorable, other stakeholder, including providers and PBMs, opposed the proposal for fear that the proposal to eliminate an existing rebate-related safe harbor would increase costs for patients, particularly seniors. HHS abandoned the rule on July 10, 2019, citing the Trump Administration’s commitment to move away from administrative rulemaking and focus on passing bi-partisan legislation. Secretary Azar added that Congress has the ability to “look more holistically at changes to the system that could also mitigate or protect seniors from rate increases.”[162] Although the rule was not enacted, the efforts to refine existing safe harbors shows a continuing focus on the Trump Administration’s efforts to decrease drug pricing by closing loopholes and creating safe harbors commensurate with the practical experiences of industry stakeholders.

IV. Stark Law Developments

The year 2019 marks the 30th anniversary of the enactment of the physician self-referral law, or Stark Law, a strict liability civil statute prohibiting hospitals and other providers of “designated health services” from submitting Medicare claims for services rendered as a result of patient referrals from a physician who has a “financial relationship” with the hospital, unless certain exceptions apply.[163] Due to the breadth of the definition of “financial relationship” under the Stark Law and the opaqueness of the enumerated exceptions, it remains a hotly debated topic and area of focus for the Trump Administration. The Patients over Paperwork initiative, launched in 2017, solicited feedback from the medical community about how CMS regulations affect their daily work. Among the responses gathered from over 2,000 stakeholders, one of the top complaints raised was about “the challenges associated with complying with the Stark law.”[164] In reaction to the challenges identified, we anticipate CMS may propose changes to Stark Law regulations this coming year.

A. Regulatory and Legislative Developments

As reported in our 2018 Mid-Year Update, CMS has solicited feedback from stakeholders in connection with its efforts to reform some aspects of the Stark Law. Though proposed regulations have not been issued, according to public remarks by CMS Administrator Seema Verma, the agency is “actively working” on reforming Stark Law regulations, promising updated regulations in 2019 that would “represent the most significant changes to the Stark law since its inception.”[165]

Administrator Verma’s remarks also foreshadowed some of the topics that are likely to be impacted by the future changes. In her comments, Administrator Verma highlighted the need to clarify “regulatory definitions of volume or value, commercial reasonableness and fair market value.”[166] She also suggested that the regulations will address issues related to technical noncompliance—for example, lack of signature or incorrect dates on a medical record.[167] The regulations are also expected to address modern dynamics related to electronic health records requirements, cybersecurity, and data privacy concerns.

The anticipated proposed regulations are part of HHS’s “Regulatory Sprint to Coordinated Care,” a department-wide initiative under which various agencies have issued requests for information (“RFIs”) to solicit feedback from industry stakeholders on removing regulatory obstacles.[168] The proposed regulations are expected later this year.[169]

B. Notable Stark Law Enforcement

In March 2019, the United States intervened in a FCA suit alleging that a struggling hospital engaged in a wide ranging referral scheme to save itself from financial ruin.[170] As part of the efforts, the hospital allegedly hired a large number of physicians as employees in order to secure those physicians’ referrals as a revenue stream for the hospital. According to the complaint, the compensation arrangements with the referring physicians failed to satisfy any statutory or regulatory exception to the Stark Law. The complaint explained that because inpatient and outpatient hospital services are designated health services under the Stark law, any fees billed to Medicare for hospital inpatient and outpatient services provided by the physicians were deemed a referral from the physician to the hospital.[171]

In May 2019, the DOJ filed an intervenor complaint in a suit alleging that a home health care company violated the Stark Law by hiring the spouses of doctors they worked with and paying them based on the “volume or value” of referrals the doctors made.[172] The United States intervened in the case nearly four years after the commencement of the relator’s suit, which alleged violations of both the AKS and Stark Law. The defendant, a home health care company, allegedly entered into sham medical director agreements with three doctors, agreeing to pay them kickbacks if they made patient referrals to the home health care company. The home health care company also hired the spouses of the physicians to conduct sales and marketing efforts to refer patients to the company. The spouses were compensated by commissions based on the referrals they generated, which constituted a financial relationship that allegedly fell outside any defined Stark Law exception.[173]

The DOJ announced four settlements related to Stark Law claims in the first half of 2019 , which collectively illustrate that a “financial relationship” with a health care provider can take many forms. For example, a January 30 settlement with a pathology laboratory centered around allegations that the laboratory offered physicians free or discounted technology consulting services as well as subsidies for electronic health records systems.[174] On June 7, the DOJ announced settlements in two cases against a home health agency that allegedly established a financial relationship with referring physicians in two ways: first, by offering a paid “medical directorship” position to referring physicians; and second, by employing spouses of physicians and paying them in a manner that took into consideration the volume of referrals made by their physician spouses.[175]

We anticipate that the second half of 2019 may bring many long-anticipated proposed changes to Stark Law regulations, and we will continue to monitor developments in this area.

V. Conclusion

The first half of 2019 brought notable developments, including a continued downturn in enforcement efforts and the issuance of DOJ guidance related to corporate compliance programs and cooperation credit. Many more potential developments have been foreshadowed or are pending in courts. As always, we will continue to monitor for updates and reports back at the end of the year.

__________________

[1] Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Deputy Associate Attorney General Stephen Cox Delivers Remarks at the 2019 Advanced Forum on False Claims and Qui Tam Enforcement (Jan. 28, 2019), https://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/deputy-associate-attorney-general-stephen-cox-delivers-remarks-2019-advanced-forum-false.

[2] See Gibson Dunn 2018 Mid-Year FDA and Health Care Compliance and Enforcement Update – Providers (July 26, 2018) [hereinafter “Gibson Dunn 2018 Mid‑Year Update”]; See Gibson Dunn 2017 Mid-Year FDA and Health Care Compliance and Enforcement Update – Providers (Sept. 4, 2017) [hereinafter “Gibson Dunn 2017 Mid‑Year Update”].

[3] Gibson Dunn 2018 Mid-Year Update; Gibson Dunn 2017 Mid-Year Update.

[4] See Gibson Dunn 2018 Mid-Year Update.

[5] Id.

[6] See id.

[7] The total is greater than 33 because some cases had multiple claims.

[8] See Gibson Dunn 2018 Mid-Year Update.

[9] Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, U.S. Attorney’s Office, N.D. of Ill., Chicago-Area Physical Therapy Center and 4 Nursing Facilities to Pay $9.7 Million to Resolve False Claims Act Allegations (June 11, 2019), https://www.justice.gov/usao-ndil/pr/chicago-area-physical-therapy-center-and-4-nursing-facilities-pay-97-million-resolve.

[10] Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Pathology Laboratory Agrees to Pay $63.5 Million for Providing Illegal Inducements to Referring Physicians (Jan. 30, 2019), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/pathology-laboratory-agrees-pay-635-million-providing-illegal-inducements-referring.

[11] Id.

[12] Id.

[13] Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Electronic Health Records Vendor to Pay $57.25 Million to Settle False Claims Act Allegations (Feb. 6, 2019), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/electronic-health-records-vendor-pay-5725-million-settle-false-claims-act-allegations.

[14] Id.

[15] Id.

[16] Gibson Dunn 2017 Mid-Year Update.

[17] Cochise Consultancy, Inc. v. United States ex rel. Hunt, 139 S.Ct. 1507 (2019).

[18] See 31 U.S.C. § 3731(b)(1)-(2).

[19] Cochise Consultancy, 139 S.Ct. at 1514.

[20] Gibson Dunn represented the petitioners challenging this decision.

[21] Cochise Consultancy, Inc. v. United States ex rel. Hunt, 887 F.3d 1081 (11th Cir. 2018).

[22] United States ex rel. Sanders v. N. Am. Bus Indus., Inc., 546 F.3d 288, 293-94 (4th Cir. 2008).

[23] United States ex rel. Hyatt v. Northrop Corp., 91 F.3d 1211, 1216-18 (9th Cir. 1996).

[24] Cochise Consultancy, 139 S.Ct. at 1512-14.

[25] 31 U.S.C. § 3730(e)(4)(A).

[26] Id. at § 3730(e)(4)(B) (emphasis added).

[27] 923 F.3d 729 (10th Cir. 2019).

[28] Id. at 757 (quoting United States ex rel. Winkelman v. CVS Caremark Corp., 827 F.3d 201, 211 (1st Cir. 2016)).

[29] Reed, 923 F.3d at 759–60.

[30] Reed, 923 F.3d at 762 (quoting Joel D. Hesch, Restating the “Original Source Exception” to the False Claims Act’s “Public Disclosure Bar” in Light of the 2010 Amendments, 51 U. Rich. L. Rev. 991, 1023, 27 (2017)).

[31] Reed, 923 F.3d at 757.

[32] Id. (quoting United States ex rel. Moore & Co., P.A. v. Majestic Blue Fisheries, LLC, 812 F.3d 294, 307 (3d Cir. 2016)).

[33] Reed, 923 F.3d at 758.

[34] 136 S. Ct. 1989 (2016).

[35] See Escobar, 136 S. Ct at 2002.

[36] United States ex rel. Prather v. Brookdale Senior Living Cmtys., Inc., 892 F.3d 822 (6th Cir. 2016), cert. denied, 139 S. Ct. 1323 (2019); see also United States ex rel. Rose v. Stephens Inst., 909 F.3d 1012 (9th Cir. 2018), cert. denied, 139 S. Ct. 1464 (2019); United States ex rel. Berg v. Honeywell Int’l, Inc., 740 F. App’x 535 (9th Cir. 2018), cert. denied, 139 S. Ct. 1456 (2019); United States ex rel. Harman v. Trinity Indus. Inc., 872 F.3d 645 (5th Cir. 2017), cert. denied, 139 S. Ct. 784 (2019); United States ex rel. Campie v. Gilead Scis., Inc., 862 F.3d 890 (9th Cir. 2017), cert. denied, 139 S. Ct. 783 (2019).

[37] 31 U.S.C. § 3730(c)(2)(A).

[38] Swift v. United States, 318 F.3d 250, 252 (D.C. Cir. 2003).

[39] Ridenour v. Kaiser-Hill Co., 397 F.3d 925, 940 (10th Cir. 2005) (internal quotation marks omitted); United States ex rel. Sequoia Orange Co. v. Baird-Neece Packing Corp., 151 F.3d 1139, 1145 (9th Cir. 1998) (internal quotation marks omitted).

[40] Memorandum from Michael D. Granston, Director, United States Department of Justice, Civil Division, Commercial Litigation Branch, Fraud Section, to Commercial Litigation Branch, Fraud Section (Jan. 10, 2018), https://www.insidethefca.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/300/2018/12/Granston-Memo.pdf.

[41] See, e.g., Order Granting Motion to Dismiss, United States ex rel. Stovall v. Webster Univ., No. 3:15-cv-03530-DCC (D.S.C. Aug. 8, 2018) (arguing that “dismissal will further [the government’s] interest in preserving scarce resources by avoiding the time and expense necessary to monitor this action”); Order Granting Motion to Dismiss, United States ex rel. Toomer v. Terrapower, LLC, No. 4:2016cv00226 (D. Idaho Oct. 10, 2018) (arguing that the case will “waste substantial government time and resources” due to the continued need “to monitor the case”).

[42] E.g., United States ex rel. Health Choice All., LLC v. Eli Lilly & Co., Inc., No. 5:17-cv-123, 2018 WL 4026986, at *3 (E.D. Tex. July 25, 2018), report and recommendation adopted, No. 5:17-CV-123, 2018 WL 3802072 (E.D. Tex. Aug. 10, 2018).

[43] United States ex rel. CIMZNHCA, LLC v. UCB, INC., No. 17-CV-765-SMY-MAB, 2019 WL 1598109, at *1–4 (S.D. Ill. Apr. 15, 2019); see also United States ex rel. Harris v. EMD Serono, Inc., 370 F. Supp. 3d 483, 488–91 (E.D. Penn. 2019) (adopting Ninth and Tenth Circuit heightened scrutiny standard, but upholding government dismissal).

[44]Ridenour v. Kaiser-Hill Co., 397 F.3d 925, 940 (10th Cir. 2005) (requiring government to identify a valid government purpose and a rational relation between dismissal and accomplishment of purpose; if government satisfies two-step test, burden switches to relator to demonstrate that dismissal is fraudulent, arbitrary and capricious, or illegal); United States ex rel. Sequoia Orange Co. v. Baird-Neece Packing Corp., 151 F.3d 1139, 1145 (9th Cir. 1998) (same).

[45] CIMZNHCA, 2019 WL 1598109, at *3.

[46] Id. at *3.

[47] Id. at *4.

[48] Id.

[49] Amended Report and Recommendation of the United States Magistrate Judge, United States ex rel. Health Choice All. v. Eli Lilly & Co., Inc., No. 5:17-CV-123-RWS-CMC (E. D. Tex. June 20, 2019); see also United States ex rel. Davis v. Hennepin Cty., No. 18-CV-01551, 2019 WL 608848, at *15 (D. Minn. Feb. 13, 2019) (holding that if courts constrain government’s ability to dismiss, “they would effectively be policing the Government’s right to dismiss, interfering with prosecutorial discretion in violation of an important separation-of-powers principle”).

[50] Health Choice All., supra note 54, at 12 (quoting Swift v. United States, 318 F.3d 250, 252 (D.C. Cir. 2003)).

[51] Health Choice All., supra note 54, at *28.

[52] See id. at *34.

[53] Texas v. United States, 340 F. Supp. 3d 579, 619 (N.D. Tex. 2018).

[54] See Brief for Defendants-Appellants United States of America et al., Texas v. United States, No. 19-10011 (filed May 1, 2019).

[55] Moda Health Plan Inc. v. United States, No. 18-1028 (Fed. Circ. 892 F.3d 1311; granted June 24. 2019).

[56] The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, Pub. L. No. 111-148, § 1342(b).

[57] See Pet. for a writ Writ of Cert., Moda Health Plan Inc. v. United States (filed Feb. 4, 2019).

[58] Moda Health Plan Inc. v. United States, 892 F.3d 1311, 1330-31 (Fed. Circ. 2018).

[59] Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Deputy Assistant Attorney General Matthew S. Miner Gives Remarks at the 29th Annual National Institute on Health Care Fraud (May 9, 2019), https://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/deputy-assistant-attorney-general-matthew-s-miner-gives-remarks-29th-annual-national.

[60] Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Appalachian Regional Prescription Opioid (ARPO) Strike Force Takedown Results in Charges Against 60 Individuals, Including 53 Medical Professionals (April 17, 2019), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/appalachian-regional-prescription-opioid-arpo-strike-force-takedown-results-charges-against.

[61] Id.

[62] See, e.g., Indictment, U.S. v. Petway, No. 1:19-cr-10041, (W.D. Tenn. Apr. 15, 2019); Indictment, U.S. v. Young, No. 1:19-cr-10040, (W.D. Tenn. Apr. 15, 2019); Indictment, U.S. v. Brown, No. 3:19-cr-00068, (S.D. Ohio Apr. 9, 2019); Indictment, U.S. v. Prasad, No. 2:19-cr-00071, (E.D. La. Apr. 16, 2019).

[63] See, e.g., Indictment, U.S. v. Prasad, No. 2:19-cr-00071, (E.D. La. Apr. 16, 2019); Indictment, U.S. v. Mahmood, No. 3:19-cr-00059, (W.D. Ky. Apr. 3, 2019); U.S. v. Assured Rx LLC, No. 3:19-cr-00058, (W.D. Ky. Apr. 3, 2019).

[64] Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, United States Attorney Announces $17 Million Healthcare Fraud Settlement (May 6, 2019), https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdwv/pr/united-states-attorney-announces-17-million-healthcare-fraud-settlement.

[65] Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Justice Department Files First of its Kind Action to Stop Tennessee Pharmacies’ Unlawful Dispensing of Opioids (Feb. 8, 2019), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-files-first-its-kind-action-stop-tennessee-pharmacies-unlawful-dispensing.

[66] Complaint, U.S. v. Oakley Pharmacy Inc., No. 2:19-cv-00009, (M.D. Tenn. Feb. 7, 2019).

[67] Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Justice Department Files Action to Enjoin Texas Doctors From Illegally Prescribing Highly Addictive Opioids and Other Controlled Substances (May 10, 2019), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-files-action-enjoin-texas-doctors-illegally-prescribing-highly-addictive.

[68] Press Release, Office of Pub. Affairs, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, New Jersey/Pennsylvania Doctor Indicted For Accepting Bribes And Kickbacks From A Pharmaceutical Company In Exchange For Prescribing Powerful Fentanyl Drug (June 25, 2019), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/new-jerseypennsylvania-doctor-indicted-accepting-bribes-and-kickbacks-pharmaceutical-company.

[69] Information, U.S. v. Mintz, No. 19-cr-00132, (E.D. Pa. Mar. 4, 2019).