January 5, 2017

I. INTRODUCTION

What a year. With two Supreme Court decisions and nearly $5 billion in recoveries (among other interesting entries) in 2016’s now-closed books, we can say with certainty that 2016 delivered plenty of False Claims Act (“FCA”) headlines. It is also clear that the U.S. government, state governments, and private whistleblowers (i.e., qui tam relators) continue to press new and aggressive theories of liability under the FCA–with significant success. As recoveries remained high and fraud theories proliferated, 2016 saw the second highest number of FCA lawsuits ever brought in a single year. Looking forward, we have little reason to believe that the government’s haul from FCA matters–or the sheer number of FCA lawsuits–will decline materially next year.

But there are several issues that will continue to be closely watched–and contested–as we head into 2017. Foremost among them is the extent to which the Supreme Court’s 2016 decision in Universal Health Services, Inc. v. United States ex rel. Escobar, 136 S. Ct. 1989 (2016), abrogated existing FCA jurisprudence regarding the statute’s falsity, materiality, and scienter elements. To the government and relators, the case represents a course correction that leaves intact the path to recover on expansive (and often nebulous) theories of liability. For defendants, Escobar requires a sweeping reassessment of the theories and allegations that have allowed plaintiffs to survive the pleading stage–and even prevail–in cases where falsity, materiality, and scienter are not readily apparent. As detailed below, the lower courts are beginning to coalesce around particular readings of Escobar; we will continue to monitor these developments throughout 2017.

Questions also linger about the incoming administration’s impact on FCA enforcement. Many observers inside and outside government have suggested that FCA enforcement may be insulated from more dramatic shifts elsewhere at the U.S. Department of Justice (“DOJ”) because of the FCA’s bipartisan appeal as a tool for returning funds to the government. But, as described below, the incoming administration’s campaign commitment to scrap the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (“ACA”), if implemented, could unwind recent changes to the FCA’s statutory language and scope, with potentially important consequences. Meanwhile, certain industries may hope for less aggressive enforcement–at least from the government–in the next four years. And individuals facing liability as part of the DOJ’s renewed emphasis on personal accountability under the so-called Yates Memorandum would welcome a reprieve from the Obama administration’s aggressive enforcement priorities.

This update first details enforcement activity under the FCA during the Fiscal Year ending September 30, 2016. In the hopes of distinguishing trends from aberrations, we break down the past year’s enforcement data, focusing on the key theories underlying, and the industries targeted in, the government’s nearly $5 billion recovery haul, and then survey the key settlements and judgments in the last six months. We then turn to the mostly quiet legislative front, summarizing the past year’s developments and analyzing potential ACA-related changes that may come to pass in 2017. Finally, we analyze the developments in FCA jurisprudence during the latter half of 2016. Please refer to our 2016 Mid-Year False Claims Act Update (“2016 Mid-Year Update”) for our assessment of the legislative and case law developments during the first half of the year.

As always, Gibson Dunn’s recent publications on the FCA may be found on our Website, including in-depth discussions of the FCA’s framework and operation along with practical guidance to help companies avoid or limit liability under the FCA. And, of course, we would be happy to speak with you about these developments.

II. FCA ENFORCEMENT ACTIVITY

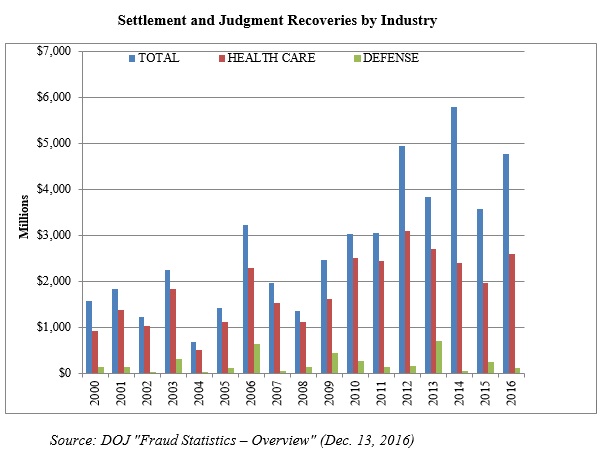

The federal government recovered more than $4.7 billion in civil settlements and judgments under the FCA during the 2016 fiscal year, the third-highest amount on record.[1] There were also more than 800 new FCA cases filed in 2016, the second-highest number of FCA cases in any single year on record.[2] All in all, 2016 was the seventh consecutive year in which the government recovered over $3 billion and where there were at least 700 new FCA matters. Below, we discuss the qui tam activity driving these remarkably high numbers and the industries that were most significantly affected.

A. Qui Tam Activity

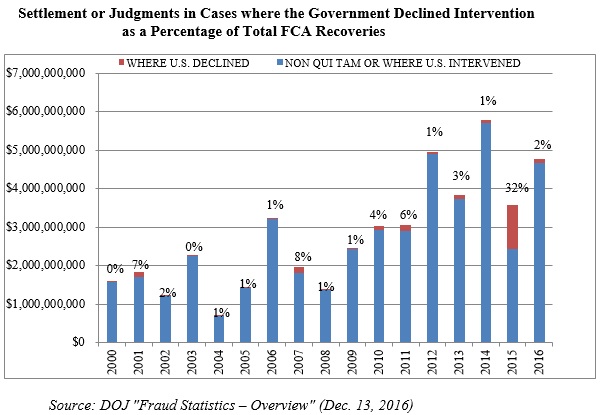

Last year, we reported on the notable fact that the government recovered a record $1.2 billion in qui tam suits where the government declined to intervene. This may well have been an aberration. Historically, the government’s decision on intervention has been strongly correlated with the potential for significant recoveries. And in 2016, recoveries in declined cases returned to a figure consistent with years past ($105 million).[3] That figure represented approximately 2% of all federal recoveries in 2016–a stark contrast to 2015, where cases in which the government declined to intervene accounted for a whopping 32% of all federal recoveries in 2015.

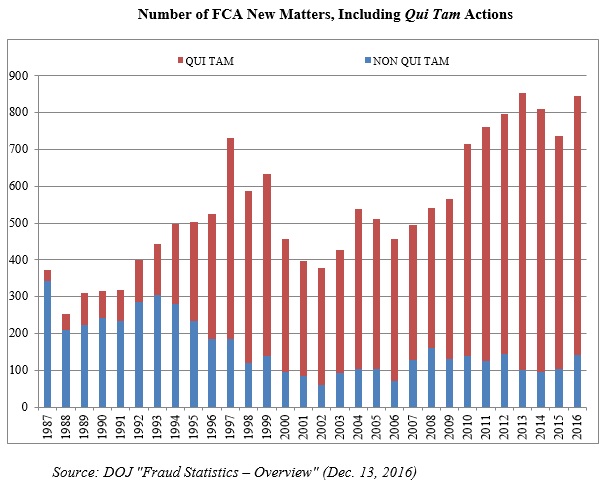

This past year’s figure does not result from any lack of effort. Keeping with the trends since the 1986 amendments to the FCA, the vast majority–about 83%–of new FCA cases filed in fiscal year 2016 were initiated by a whistleblower (702 out of 845). Although consistent with recent years, this marks a dramatic increase since Congress amended the FCA in 1986: in the first five years after the amendments, only about one-quarter of FCA cases were qui tam cases. Yet, whistleblowers have now brought more than 11,000 qui tam cases since 1986–70% of the total.

The chart below demonstrates both the increase in overall FCA litigation activity since 1986 and the distinct shift from largely government-driven investigations and enforcement to qui tam-initiated lawsuits. After two years of declines in the overall number of cases, 2016’s total jumped up to a near-record total:

The government chooses to intervene in about 20% of FCA cases.[4] But, as noted above, that sliver of the overall total of FCA cases resulted in the vast majority of recoveries for the federal government in 2016:

B. Industry Breakdown

Recoveries from health care and life sciences companies continued to make up the lion’s share of the total of FCA recoveries, as the government recovered $2.5 billion from entities in the health care industry. But after a relatively quiet 2015 for FCA cases involving financial institutions, the DOJ also obtained more than $1.6 billion from the financial industry in 2016 thanks to reinvigorated enforcement of alleged mortgage-related fraud.

1. Health Care Industry

Just as in 2015, 55% of all federal FCA recoveries came from the health care industry (including life sciences companies) in 2016. The typical health care FCA case involves allegations that a defendant defrauded federal health care programs, such as Medicare, Medicaid, and TRICARE, which provides health care to members of the armed services and their dependents. Since January 2009, the DOJ has recovered $19.3 billion for purported health care fraud under the FCA.[5] Just shy of $2.6 billion of that total came in fiscal year 2016.[6]

That substantial sum represented a significant rebound from recoveries in each of the preceding three years, thanks in part to another round of large-value settlements from a handful of companies. For example, a branded pharmaceutical maker paid $413 million to the federal government after it allegedly reported falsely inflated prices for two of its drugs to Medicaid, thereby decreasing rebate payments it was required to make to Medicaid that were pegged to those prices.[7] Another maker of branded drugs settled with the government for $390 million–including nearly $307 million paid to the federal government–to resolve allegations that it paid kickbacks to pharmacies that agreed to recommend two of the company’s drugs.[8]

Federal regulators were active on this front during the past year. In its Spring 2016 Semiannual Report to Congress, the Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General (“HHS OIG”) reported that it commenced 379 civil actions (including but not limited to FCA actions) in the first half of the 2016 fiscal year,[9] far in excess of the 320 it commenced during the same period in 2015.[10] HHS OIG also reported expected recoveries of approximately $2.8 billion, including about $2.2 billion in “investigative receivables.”[11] Both of these figures are more than 50% greater than the comparable figures from just a year ago.[12]

It will come as no surprise that the Anti-Kickback Statute (“AKS”) and the Stark Law lurked behind many of the FCA recoveries in the health care industry this past year. The AKS prohibits giving or offering–and requesting or receiving–any form of payment in exchange for referring a product or a service that is covered by federally funded health care programs.[13] The Stark Law prohibits physicians from referring Medicare patients to a provider with which the physician has a financial relationship.[14] Among other noteworthy settlements in 2016, the DOJ entered into a settlement with a laboratory testing company for nearly $260 million after it allegedly violated the AKS and the Stark Law by allegedly billing for unnecessary testing and bribing physicians to refer tests to the company.[15]

FCA recoveries from hospitals and hospital systems have lagged behind those from pharmaceutical, medical device, and outpatient clinics in recent years. However, in 2016, a large chain of hospitals paid more than $360 million after the government alleged that it paid kickbacks to physicians.[16]

2. Government Contracting and Defense/Procurement

Recoveries from government contracting firms dropped in 2016 as compared to recent years (down to $122 million).[17] Of that amount, $82.6 million came from the government’s settlement with an energy exploration company of allegations that the company concealed unsafe drilling habits, leading to an oil spill. The government alleged that this constituted an FCA violation because of billings related to the exploration company’s lease of the land on which it drilled from the Department of the Interior.[18]

In what could be the beginning of a trend in the next administration, the DOJ recovered about $50 million for alleged violations of customs regulations that impose duties on certain imported goods.[19] For example, a Texas company and a California company both paid $15 million for allegedly evading duties on Chinese furniture.[20] Given the rhetoric on trade and imports that pervaded the presidential campaign, this type of case seems likely to continue to gain steam in 2017.

3. Financial Industry

In 2014, the government recovered massive amounts of money in FCA cases against financial institutions that allegedly contributed to the financial crisis through their mortgage lending and underwriting practices. In 2015, recoveries from the financial industry declined by about 90% from their 2014 high of more than $3.1 billion. But anyone who believed that the government was no longer pursuing financial institutions for mortgage-related practices in the lead-up to the financial crisis was sorely mistaken. Financial-industry FCA recoveries more than quadrupled in 2016, up to $1.6 billion.[21]

III. NOTEWORTHY SETTLEMENTS AND JUDGMENTS ANNOUNCED DURING THE SECOND HALF OF 2016

As noted above, FCA settlements and judgments resulted in more than $4.7 billion in recoveries for the government this year. We summarize below a number of notable settlements and judgments announced during the past six months (notable settlements and judgments from the first half of the year were covered in our 2016 Mid-Year Update), including in the health care and life sciences industries, government procurement and defense industries, and the financial industry. These cases provide specific examples of the industries the government has targeted, as well as the theories of liability that the government and relators have advanced.

Notably, in the first full year after it issued the Yates Memorandum, which promised a more aggressive approach to individual accountability, the DOJ also secured millions of dollars in recoveries from individuals, including at least ten doctors and health care industry executives. Several of these cases are also highlighted below.

A. Health Care and Life Sciences Industries

- On June 29, 2016, a Minneapolis-based medical device company agreed to pay $8 million to resolve allegations that it provided illegal kickbacks to physicians through marketing and other practice development services promoting the use of its devices in atherectomies. The government alleged that the company coordinated meetings with referring physicians and implemented business expansion plans for physicians using the devices. The company also entered into a five-year Corporate Integrity Agreement (“CIA”) with HHS OIG that requires the company to undergo reviews by an independent organization.[22]

- On June 30, 2016, a California-based health care provider agreed to pay $5.5 million to settle allegations that it and several other entities and individuals violated the federal FCA and California’s analogue. The government alleged various billing violations, including providing chemotherapy infusions without having a physician present and improperly billing for double dosages after using single dose vials on more than one patient.[23]

- On July 5, 2016, a Pennsylvania-based owner and operator of physical therapy clinics settled health care fraud allegations for $7 million. The government alleged that the provider submitted claims for individual physical therapy sessions when its physical therapists and assistants were actually providing group sessions. The whistleblowers were former employees of the company and will receive $1.68 million.[24]

- On July 13, 2016, a Minnesota-based hospice provider agreed to pay $18 million to resolve allegations that it submitted reimbursements to Medicare for ineligible hospice patients who were not terminally ill. The government alleged that the provider discouraged doctors from recommending discharge from hospice and failed to ensure accurate and complete documentation of patients’ conditions in their medical records.[25]

- On July 12, 2016, a federal district court judge ordered two New Jersey-based diagnostic imaging companies and their owners to pay $7.75 million for submitting falsified diagnostic test reports, underlying tests, and claims for neurological tests conducted without physician supervision. The court’s order came after it granted the United States’ motion for summary judgment. Separately, the owners pled guilty to charges of health care fraud related to the conduct.[26]

- On July 13, 2016, a federal district court judge entered a judgment of $4.5 million against the owner of two medical device companies and her companies for allegedly making false statements in order to receive millions of dollars in federal grants from the National Institutes of Health (“NIH”). The government alleged that the owner improperly diverted the funds to her personal use and impermissible business expenses rather than to developing customized electronic pillboxes for specific patient populations, as contemplated by the grants.[27]

- On July 22, 2016, a diagnostic imaging service provider agreed to pay $3.51 million to resolve alleged federal and Texas False Claims Act violations. The government alleged that independent diagnostic facilities operated by the company performed certain procedures without required physician supervision on-site.[28]

- On July 22, 2016, a California-based medical device manufacturer agreed to pay $18 million to resolve off-label allegations that it marketed and distributed its sinus spacer product for use as a drug delivery device without FDA approval. Notably, the government alleged that it continued its off-label marketing even after the FDA rejected the company’s request to expand the approved uses, and even though the company added a warning to its label regarding the use of active drug substances in the device. On July 20, 2016, the company’s former CEO and former Vice President of Sales also were convicted following a trial of ten misdemeanor counts of introducing adulterated and misbranded medical devices into interstate commerce. The whistleblower will receive approximately $3.5 million from the settlement.[29]

- On July 28, 2016, a South Carolina hospital agreed to pay $17 million to resolve allegations that it violated the FCA and the Stark Law by maintaining improper financial arrangements with 28 physicians. The government alleged that the hospital entered into improper employment agreements and asset purchase agreements for the acquisition of physician practices, which were tied to referral volume or value, were not “commercially reasonable,” or exceeded fair market value. As part of the settlement, the hospital will enter into a five-year CIA. The relator, a former physician employed by the hospital, will receive approximately $4.5 million.[30]

- On July 29, 2016, a federal district court judge entered a judgment against an Oklahoma-based behavioral health counseling company and its owner for $4.7 million to resolve alleged violations of the federal FCA and its Oklahoman analogue for false claims submitted to the jointly funded Oklahoma Medicaid program. The government alleged that the company and its owner sought reimbursement for services provided by unqualified personnel, altered service codes to support reimbursement, and double-billed for services, among other issues. The company and its owner must also comply with a five-year national exclusion from participation in the Medicaid and Medicare programs.[31]

- On August 1, 2016, a New York hospital paid $3.2 million to settle allegations that it violated both the federal and New York false claims statutes by presenting claims for reimbursement to the state Medicaid program for services performed by purportedly unqualified staff. United States and New York attorneys alleged that, between 2007 and 2016, hospital personnel provided services for individuals suffering from an acute mental health crisis even though the personnel performing such services did not meet regulatory staffing requirements, such as having two professional staff members present when mental health services are rendered outside of an emergency room.[32]

- On August 31, 2016, a health services provider agreed to pay $7.4 million to resolve allegations that it sought reimbursement for medically unnecessary drug screening procedures in violation of the FCA. The government alleged that the company performed expensive “quantitative drug tests” on all patients in its care, even though these are generally only to be performed when there is reason to doubt the results of less expensive “qualitative drug tests.” Because the company performed both tests on all of its patients, the government contended that the company submitted reimbursement claims to Medicare for medically unnecessary services.[33]

- On September 7, 2016, two medical equipment companies focusing on the supply of durable medical equipment to diabetic patients, along with their owners and presidents individually, agreed to pay more than $12.2 million to resolve allegations that they used a fictitious entity to make unsolicited calls to Medicare beneficiaries to sell them medical equipment. The companies’ scheme allegedly violated the Medicare Anti-Solicitation Statute, which prohibits submitting claims to Medicare for equipment sold based on unsolicited cold-calls.[34]

- On September 14, 2016, the owner of a home health care company agreed to pay $6.8 million to resolve civil allegations that the company allegedly violated the FCA and the AKS by inducing false certifications of eligibility for home services through illegal kickbacks and then submitting claims for these purportedly fraudulent services to Medicare. In connection with this civil settlement, the company’s owner pled guilty to one criminal count of violating the AKS, which is punishable by up to five years in prison; sentencing is scheduled for February 2017.[35]

- On September 14, 2016, the owners of a compound pharmacy agreed to pay $7.75 million to resolve allegations that they violated the FCA by purportedly submitting claims for reimbursement that were not reimbursable. The government alleged that from January 2013 through January 2014, the pharmacy requested reimbursement for prescriptions it had procured through the use of illegal kickbacks, in violation of the AKS.[36]

- On September 19, 2016, a skilled nursing services company, the chairman of its board, and the senior vice president of reimbursement analysis settled civil claims that they allegedly violated the FCA. The government’s allegations involved the purported submission of false for medically unnecessary services. The settlement provided for payments of $28.5 million from the company, $1 million from the board chairman, and $500,000 from the senior vice president. The settlement further provided for the company to enter into a CIA.[37]

- On September 28, 2016, a national hospital chain agreed to pay $32.7 million, plus interest, to settle allegations that the company violated the FCA by billing Medicare for unnecessary services. The company allegedly admitted persons to its facilities who did not demonstrate symptoms that qualified them for admission, in addition to extending the stays of some patients without regard for necessity or quality of care. As part of the resolution, the company will be subject to a five-year CIA. The case was originally filed by a former employee of a facility, who will receive at least $4 million of the settlement.[38]

- On September 29, 2016, a home health care agency was ordered to pay $6.15 million in civil damages after the judge ruled the agency violated the FCA by falsifying records to obtain Medicaid funding. The judge ruled in the government’s favor in February 2016, after finding that the evidence showed patient files contained forged physician signatures and falsified timesheets, and that employees had alerted the president and founder of the agency that other employees were defrauding the government, but the agency did not report the fraudulent conduct to Medicaid. The judge trebled the $1.3 million damage award to the United States and imposed an additional $10,000 penalty for each D.C. Medicaid invoice submitted, which totaled 216 invoices.[39]

- On October 3, 2016, a U.S. hospital network and multiple subsidiaries agreed to pay more than $513 million to settle criminal and civil claims alleging bribery and kickbacks to owners and operators of prenatal care clinics in exchange for the clinics referring patients to the hospital chain or its subsidiaries for labor and delivery services. Two subsidiaries pled guilty to conspiracy to defraud the U.S. and to pay kickbacks and bribes in violation of the AKS. The subsidiaries also agreed to forfeit more than $145 million. Another subsidiary, which was the parent of the two subsidiaries previously mentioned, entered into a three-year non-prosecution agreement. As part of the civil settlement, the hospital chain agreed to pay $368 million to resolve the claims. The federal government will receive approximately $244.2 million; the state of Georgia will receive nearly $123 million; and the state of South Carolina will receive more than $892,000. A whistleblower, who brought the original suit under the federal and Georgia false claims statutes, will receive more than $84 million.[40]

- On October 14, 2016, a global settlement was reached with an independent laboratory, a nutritional supplement provider, and the founder of both companies for over $6.1 million to resolve claims that they submitted false claims to Medicare and TRICARE. The laboratory was subject to requirements under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (“CLIA”), which required that the laboratory validate its tests to ensure their reliability and accuracy. The companies allegedly reported test results based on an improperly validated reference range, recommended products to patients based on that range, and did not report those activities to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (“CMS”). As part of the global settlement, the supplement provider pled guilty to conspiring to obstruct CMS’s administration of the CLIA program, and the founder pled guilty to intentionally violating the CLIA program requirements.[41]

- On October 14, 2016, a not-for-profit community health system agreed to pay $5.85 million to settle allegations that it violated the FCA by misreporting information on annual cost reports regarding the number of hours its employees worked. This misreporting caused the wage index in the area to be artificially inflated, and also caused the health system to allegedly receive more money from Medicare than owed. The case was originally brought by a whistleblower, who will receive a $1.17 million share of the settlement.[42]

- On October 17, 2016, the nation’s largest nursing home pharmacy agreed to pay $28.13 million to settle claims that it both solicited and received kickbacks from a pharmaceutical manufacturer in exchange for promoting the manufacturer’s prescription drug. The federal government will receive approximately $20.3 million and the state Medicaid portion is approximately $7.8 million. This settlement, together with two prior settlements with the manufacturer and another nursing home pharmacy, resolves two FCA lawsuits filed by former employees of the pharmaceutical manufacturer. As part of this settlement, one of the whistleblowers will receive $3 million.[43]

- On October 21, 2016, a hematology-oncology medical practice agreed to pay $5.31 million to settle claims that the practice unlawfully waived copayments and fraudulently billed Medicaid for the copayments, as well as submitted false claims for services that were never provided or were not permitted under government program rules. As part of the settlement, the practice admitted, acknowledged, and accepted responsibility for the fraudulent acts. The practice also entered into a CIA. A whistleblower initially filed this lawsuit.[44]

- On October 21, 2016, the owner of a Florida-based compound pharmacy agreed to pay $4.25 million to settle claims that the compound pharmacy billed federal health care programs for services it knew were not reimbursable because they were allegedly tainted under the AKS. The government remains engaged in claims against other participants allegedly involved with the compound pharmacy.[45]

- On October 24, 2016, a skilled nursing facility chain agreed to pay $145 million to settle allegations that the company submitted false claims to Medicare and TRICARE for services that were unreasonable or unnecessary. According to the government, the company engaged in systemic efforts to increase billing to Medicare and TRICARE by, for example, instituting corporate-wide policies that resulted in patient stays that were longer than necessary. The settlement is the DOJ’s largest settlement with a skilled nursing facility. The company also entered into a CIA. The case was originally filed by a whistleblower, who will receive $29 million.[46]

- On October 24, 2016, a holding company for subsidiaries that operate skilled nursing facilities in Texas agreed to pay $5.3 million to settle claims that they submitted bills to Medicare and Medicaid for materially substandard services provided to several residents of four of the nursing facilities. The holding company also entered into a five-year CIA as part of the settlement.[47]

- On November 7, 2016, a medical device company agreed to pay $25 million to resolve allegations that it violated the FCA by causing false claims to be submitted to government health care programs. The company allegedly promoted its embolization device–designed to be inserted into blood vessels to block the flow of blood to tumors–for off-label use as a “drug-delivery” device, which was not an FDA-approved use and was not supported by substantial clinical evidence. The company also agreed to pay an additional $11 million in criminal fines and forfeitures.[48]

- On December 7, 2016, a Florida-based orthopedic medical group agreed to pay $4.48 million to resolve allegations that it billed the government for services that were not medically necessary and reasonable. The government alleged that the group engaged in “questionable” billing practices related to, among other things, certification of “meaningful use” of electronic health records, care provided without physician supervision, and medically unnecessary procedures.[49]

- On December 7, 2016, a not-for-profit hospital in southern Florida agreed to pay $12 million to resolve claims that one of its doctors allegedly performed unnecessary cardiac procedures, including echocardiograms and electrophysiology studies, for the “sole purpose of increasing the amount of physician and hospital reimbursements.” The allegations arose from two other doctors who brought suit as whistleblowers.[50]

- On December 9, 2016, a pharmaceutical company agreed to pay $19.5 million to settle claims with forty-three state attorneys general concerning the alleged off-label promotion of its schizophrenia drug. The company allegedly promoted the drug for use in pediatric populations and to treat dementia and Alzheimer’s in elderly patients, despite the fact that those were not FDA-approved uses.[51]

- On December 15, 2016, a pharmaceutical company agreed to pay $38 million to resolve allegations that it paid kickbacks to induce physicians to prescribe their drugs. The alleged kickbacks came in the form of meals and payments in connection with speaker programs. The company allegedly provided the payments even when the programs were cancelled, when no licensed health care professionals attended the programs, or when the same physicians attended multiple programs over a short period of time.[52]

B. Government Contracting and Defense/Procurement

- On July 6, 2016, five California-based information technology companies agreed to pay a total of $5.8 million to resolve allegations that they falsely certified that one of the companies met small business requirements in order to obtain contracts reserved for small businesses, even though its affiliation with the other companies was an alleged disqualifier. The government also alleged that the companies underreported sales under a General Services Administration contract to avoid required fee payments. The whistleblowers who filed the suit will receive approximately $1.4 million of the settlement.[53]

- On July 14, 2016, a federal district court judge approved a $9.5 million settlement with a New York-based university to resolve allegations related to the university’s purported receipt of excessive cost recoveries in connection with 423 research grants funded by the NIH. The government alleged that the university sought federal reimbursements for costs at a higher “on-campus” rate, even though the research was primarily conducted at off-campus facilities owned and operated by the state and by New York City and even though the university did not pay for the use of the space for most of the relevant period.[54]

- On October 28, 2016, several geothermal power plant operators agreed to pay a total of $5.5 million to settle claims that they violated the FCA by submitting applications for federal clean energy grants that they were not entitled to receive. The claim was initially brought by two former employees of one of the operators.[55]

- On November 4, 2016, an aerospace company agreed to pay $2.7 million to resolve allegations that it falsely certified it had performed required inspections on aerospace parts used in military aircraft, spacecraft and missiles used by the Department of Defense. The company sold those parts to major defense contractors, who used them in equipment eventually sold to the United States. The employee who filed the qui tam action will receive $621,000 of the recovered funds.[56]

- On November 23, 2016, a group of Energy Department contractors agreed to pay $125 million to resolve allegations that they improperly billed the government for services and goods rendered under a contract to clean up a nuclear site. The contractors allegedly billed the government despite failing to comply with mandatory standards related to materials, testing, and services in connection with the contract. The case originated with complaints from three former employee whistleblowers.[57]

C. Financial Industry

- On August 16, 2016, a large national bank agreed to pay $9.5 million to settle FCA allegations that it submitted claims for reimbursement to the Small Business Administration (“SBA”) even though it knew or should have known that some of the requirements for reimbursement had not been met. These allegations stemmed from SBA-guaranteed loans brokered by another, smaller bank, which admitted in separate plea agreements that its employees created false documents to secure the larger bank’s approval.[58]

- On September 13, 2016, a regional bank based in the southeastern United States agreed to pay $52.4 million to resolve allegations that it knowingly originated and underwrote faulty mortgage loans issued by the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (“HUD”) Federal Housing Administration (“FHA”). As part of this settlement, the bank admitted that, from 2006 through 2011, it certified mortgage loans that did not meet HUD’s underwriting requirements regarding creditworthiness, neglected to adequately monitor its underwriting process, and failed to fully self-report suspected findings of fraud to HUD.[59]

- On September 29, 2016, a banking company agreed to pay $83 million to settle claims that it knowingly originated and underwrote mortgage loans insured by the FHA that did not meet the FHA’s quality control requirements or HUD’s underwriting requirements. Due to the company’s actions, HUD allegedly insured loans endorsed by the company that were not eligible for mortgage insurance under the relevant program, and that HUD would not have otherwise insured.[60]

- On October 3, 2016, two Utah-based mortgage companies agreed to pay a total of $9.25 million ($5 million from one company and $4.25 million from the other company) to resolve allegations that they knowingly originated and underwrote mortgage loans insured by the FHA that did not meet the program’s requirements. Both companies admitted their actions as part of the settlement.[61]

- On November 30, 2016, after a five-week trial, a jury found two related mortgage originators liable for violations of the FCA and the Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery and Enforcement Act of 1989 (“FIRREA”), and awarded single-damages of more than $92 million. The mortgage companies allegedly originated mortgages at a network of “shadow” branches that were not approved by HUD, and therefore not subject to HUD oversight, resulting in unapproved FHA loans. The single-damages award could grow larger after statutory trebling and imposition of per-claim civil penalties.[62]

D. Other

- On July 13, 2016, a clothing importer and two foreign clothing manufacturers agreed to pay $13.38 million to settle alleged FCA violations for under-reporting the value of their imported merchandise. The government alleged that the companies conspired with clothing wholesalers to underpay customs duties by making false representations in entry documents filed with the U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Pursuant to the alleged double invoicing scheme, the companies allegedly presented one invoice that undervalued the garments to the government to use in duty calculations, while another invoice reflected the garments’ actual value.[63]

- On July 14, 2016, a federal district court judge approved a settlement for $4.29 million with a New York-based for-profit educational institution and its former COO to resolve alleged violations of two U.S. Department of Education (“DOE”) rules. Pursuant to Program Participation Agreements with the DOE, for-profit schools agree to comply with various rules and requirements to participate in federal funding programs. The institution allegedly violated rules prohibiting incentive compensation payments to enrollment personnel based on success in securing student enrollments and advertising inaccurate job placement rates to prospective students.[64]

- On August 24, 2016, an insurance carrier for a now-defunct for-profit cosmetology school agreed to pay over $8.6 million to settle qui tam allegations brought by six former employees that it obtained federal student loan funds for students whom the school helped obtain allegedly bogus high school diplomas. According to the allegations, the school allowed students without high school diplomas wishing to enroll at the school to take a test to earn the equivalent of a diploma, but the school allowed these students to take the tests without a proctor, to use their phones and notes to look up answers, and to take the test repeatedly until they passed.[65]

IV. LEGISLATIVE ACTIVITY

In light of the November 2016 election, it is not surprising that the second half of 2016 was relatively quiet on the legislative front. Although there was no new legislation at the federal level, the Department of Justice’s interim final rule increasing maximum penalties for FCA violations took effect on August 1, 2016. Under the rule, the maximum penalties jumped from $11,000 to $21,563 per claim. The rule applies to penalties assessed after August 1, 2016, whose associated violations occurred after November 2, 2015[66] and, as discussed in our 2016 Mid-Year Update, may result in an uptick in Eighth Amendment and Due Process challenges to judgments, particularly when the amount awarded in penalties dwarfs the damage to the government.

If, as expected, the new Congress introduces legislation to repeal and/or replace the ACA, consistent with the President-elect’s campaign promise, the new year may bring a flurry of FCA-related activity at the federal level. We address below the potential impact of a repeal on those provisions of the ACA that modified the FCA.

At the state level, legislative activity was also quiet, with no significant legislative developments since our 2016 Mid-Year Update.

A. Federal Activity: Potential for ACA Repeal in 2017

The President-elect has promised to repeal the ACA within his first 100 days in office.[67] Although many Congressional leaders also have pledged to repeal the ACA, it is difficult to predict precisely how Congress will handle the ACA. The significant questions that remain regarding the extent to which Congress will repeal–and, perhaps, replace–the ACA implicate the components of the FCA that were amended by the ACA.

In particular, the ACA modified the FCA’s “public disclosure bar” in several respects. The ACA removed any reference to “jurisdiction” from the public disclosure bar, a shift which several courts have interpreted to mean that the bar is no longer jurisdictional in nature. See, e.g., United States ex rel. Moore & Co., P.A. v. Majestic Blue Fisheries, LLC, 812 F.3d 294, 299–300 (3d Cir. 2016). The ACA also provided the government discretion to oppose the dismissal of qui tam actions where the allegations are based on public disclosures. 31 U.S.C. § 3730(e)(4). Further, the ACA narrowed the definition of “public” disclosures to encompass only federal criminal, civil, or administrative disclosures, meaning that relators can base qui tam lawsuits on disclosures from state and local government sources, unless the information is also disclosed in the news media or another source encompassed by the statutory language. 31 U.S.C. § 3730(e)(4)(A)(i)–(iii). The ACA also modified the standard for a relator to qualify as an “original source.” Rather than requiring the relator to have “direct and independent knowledge” of the alleged fraud, the ACA eliminated the “direct” knowledge requirement, and instead required “knowledge that is independent of and materially adds to the publicly disclosed allegations or transactions.” 31 U.S.C. § 3730(e)(4)(C).

Aside from those procedural amendments, the ACA altered the FCA in ways that were particularly important to Medicare and Medicaid providers. First, the ACA clarified the 60-Day Rule established under the Fraud Enforcement and Recovery Act of 2009 (“FERA”), which requires payback of Medicare and Medicaid overpayments within 60 days of identification. 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7k(d). The failure to return government overpayments can lead to potential FCA liability under a “reverse false claims” theory pursuant to 31 U.S.C. § 3729(a)(1)(G). Second, the ACA also provided that any claim submitted in violation of the AKS constitutes a false and fraudulent claim for purposes of the FCA. Further, the ACA relaxed the intent requirement such that the government can establish a violation of the AKS without showing that a defendant either knew about the statute’s specific prohibitions or intended to violate the statute. 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b(h).

A full repeal of the ACA would have the effect of eliminating all of these provisions. However, with Congress still undecided about how to address the ACA, the amendments relevant to FCA enforcement remain intact.

B. State Activity

There was very little legislative activity at the state level in the second half of 2016. But that activity may pick up as a result of a September 2016 announcement by the CMS that states should amend their false claims acts in the next two years to mirror the increased civil penalties available under federal law.[68] States that do not take this action may be deemed by the DOJ and HHS OIG to be less effective than the federal FCA in facilitating qui tam actions and thereby lose the ability to increase by 10% their share of recoveries in cases that prosecute Medicaid fraud.

On May 2, 2016, the Louisiana Senate voted against legislation introduced in 2014 to create a broader Louisiana False Claims Act (S.B. 327). However, on May 3, 2016, the bill was returned to the calendar and may be called for further consideration at a later time.[69] Currently, Louisiana has a false claims act circumscribed to claims related to funds for medical care.[70]

Additionally, HHS OIG has determined that the Nevada False Claims Act[71] and amended Washington Medicaid Fraud False Claims Act[72] are compliant with Debt Recovery Act (“DRA”) requirements and are at least as robust as the federal FCA. HHS OIG has yet to announce whether Maryland’s expanded False Claims Act,[73] which became effective in 2015, and Wyoming’s False Claims Act,[74] enacted in 2013, meet DRA requirements.[75]

As for several items that we mentioned in previous updates:

- On February 11, 2016, Alabama legislators introduced a false claims act in the state’s senate. Legislation is still pending in the state’s Senate Judiciary Committee.[76]

- In New Jersey, no further action has been taken on a bill that would authorize the retroactive application of New Jersey’s False Claims Act under certain circumstances. The general assembly, the lower house of the state’s legislature, previously passed this bill on May 14, 2015.[77]

- In New York, no further action has been taken on a May 2015 bill that would provide for securities fraud whistleblower incentives and protections.[78]

- South Carolina legislators have taken no further action on a bill to enact the “South Carolina False Claims Act” (S.B. 223), which was referred to the Committee on Judiciary in January 2015.[79]

V. CASE LAW

The Supreme Court’s June 2016 Escobar decision drove significant developments in FCA jurisprudence during the second half of the past year. But, as discussed below, the federal courts also handed down noteworthy cases addressing other aspects of the FCA during the last six months.

A. Post-Escobar Developments

As we reported in our 2016 Mid-Year Update, the Supreme Court’s landmark Escobar decision reshaped the legal landscape in FCA cases. Indeed, the Court both affirmed the viability of the “implied false certification” theory of liability under certain circumstances and sharpened the FCA’s “demanding” materiality standard.

Yet, like many Supreme Court decisions, Escobar does not answer all questions. Thus, in the wake of Escobar the lower courts have grappled with the Supreme Court’s opinion. Two hotly litigated issues have come to the forefront in these cases: (1) the requirements a plaintiff must meet to advance a viable “implied false certification” theory and (2) the proper application of Escobar’s interpretation of the FCA’s materiality standard. We explore the key cases addressing these issues below, and we will closely monitor these and other Escobar-related issues as they develop in the upcoming year.

1. Defining the Boundaries of an “Implied False Certification” Claim

The Supreme Court stated in Escobar that an “implied certification” theory can provide a basis for liability under the FCA where (1) “the claim does not merely request payment, but also makes specific representations about the goods or services provided,” and (2) “the defendant’s failure to disclose noncompliance with material statutory, regulatory, or contractual requirements makes those representations misleading half-truths.” 136 S. Ct. at 2001 (emphasis added). Since then, the lower courts have reached different conclusions as to the precise circumstances under which a relator may pursue an implied certification theory.

Most courts have imposed a strict test, requiring the FCA plaintiff to show the defendant made specific misleading representations about the goods or services provided to be liable based on an implied false certification theory. See, e.g., United States ex rel. Tessler v. City of N.Y., No. 14-CV-6455, 2016 WL 7335654, at *4 (S.D.N.Y. Dec. 16, 2016); United States v. Crumb, No. 15-0655, 2016 WL 4480690, at *12 (S.D. Ala. Aug. 24, 2016); United States ex rel. Beauchamp v. Academi Training Ctr., Inc., No. 1:11-CV-371, 2016 WL 7030433, at *3 (E.D. Va. Nov. 30, 2016). As these courts have observed, imposing liability in the absence of a sufficiently “specific” misrepresentation about the goods or services provided “would result in an ‘extraordinarily expansive view of liability’ under the FCA, a view that the Supreme Court rejected in Escobar.” Tessler, 2016 WL 7335654, at *4 (citing Escobar). Under this reading of Escobar, courts have not hesitated to dismiss cases where the relator fails to identify specific misrepresentations. See, e.g., Tessler, 2016 WL 7335654, at *4; cf. New York ex rel. Khurana v. Spherion Corp., No. 15-CV-6605, 2016 WL 6652735, at *15 (S.D.N.Y. Nov. 10, 2016) (dismissing New York False Claims Act claim under Escobar on this basis).

In October, the Seventh Circuit addressed Escobar’s impact on the implied false certification theory, concluding that a relator must prove the defendant made specific, misleading representations in connection with a claim for payment. In United States v. Sanford–Brown, Ltd., the Seventh Circuit reconsidered an earlier opinion affirming summary judgment in favor of the defendant, after the Supreme Court vacated and remanded the case in light of Escobar. 840 F.3d 446–47 (7th Cir. 2016). There, following Escobar, the Seventh Circuit held that an implied false certification theory can only be a basis for liability where (i) “the claim does not merely request payment, but also makes specific representations about the goods or services provided” and “the defendant’s failure to disclose noncompliance with material statutory, regulatory, or contractual requirements makes those representations misleading half-truths.” Id. at 447. The court once again affirmed summary judgment for the defendant, finding that the relator had offered no evidence that the defendant had made “any representations at all,” let alone a misleading one. Id. (holding that “bare speculation that [a defendant] made misleading representations is insufficient”).

Among the courts that have strictly construed Escobar, several have concluded that use of billing codes that correspond to particular services, procedures, or individuals with certain qualifications are sufficiently “specific” representations, if false, to state a claim. See Crumb, 2016 WL 4480690, at *13 (Medicare and Medicaid billing codes); United States ex rel. Lee v. N. Adult Daily Health Care Ctr., No. 13-CV-4933, 2016 WL 4703653, at *11 (E.D.N.Y. Sept. 7, 2016) (Medicaid billing codes); Beauchamp, 2016 WL 7030433, at *3 (codes corresponding to jobs restricted to those with specific qualifications). By contrast, at least one court has held that general allegations regarding representations that the defendant complied “with applicable implementing federal, state, and local statutes, regulations, [and] policies,” fail to represent anything specific about the good or services. See Tessler, 2016 WL 7335654, at *4.

A minority of courts has embraced a less restrictive reading of Escobar, rejecting the notion that an implied certification theory requires specific misleading representations. For example, in Rose v. Stephens Institute, the court rejected the argument “that Escobar establishes a rigid” test for falsity “that applies to every single implied false certification claim.” No. 09-CV-05966, 2016 WL 5076214, at *5 (N.D. Cal. Sept. 20, 2016). Reasoning that the Supreme Court left the door open by limiting its holding to “at least” the circumstances before it in Escobar and by expressly declining to “resolve whether all claims for payment implicitly represent that the billing party is legally entitled to payment,” the court held that a relator can state an implied false certification claim without necessarily identifying a “specific” representation that was a “misleading half-truth” in any claim. Id. The court declined, however, to elaborate on what such a claim might look like because it found that the relator had identified a specific representation–in the form of a representation that the defendant was “eligible” to receive the funds for which it was seeking reimbursement. That representation, according to the court, would be a misleading half-truth if, as the plaintiff alleged, the defendant was not in compliance with applicable regulations (and therefore, ineligible to receive payment). Id.

A magistrate judge from the Western District of New York also reached the same conclusion. United States ex rel. Panarello v. Kaplan Early Learning Co., No. 11-CV-00353, Dkt. No. 96, at 8–10 (W.D.N.Y. Nov. 14, 2016). There, the plaintiff alleged that the defendant violated the FCA by submitting claims for work performed by workers who were not paid the government’s prevailing wage requirements. The magistrate judge accepted relator’s theory that the defendant had falsely certified that it had complied with those wage requirements simply by making a claim for payment, reasoning that Escobar does not require specific representations in every implied false certification claim. Id. at 8–9. The court reached this conclusion even as it acknowledged that the claims contained no payment codes (and did not even make any mention of the labor requirements), and thus lacked any “specific” representations. Id. The magistrate judge’s opinion is presently under consideration by the district court.

Although most federal appellate courts have not yet weighed in on the issue, we expect that more will begin to do so in this coming year. The Rose court, for example, subsequently certified its decision on this issue for interlocutory appeal to the Ninth Circuit. 2016 WL 6393513, at *1 (N.D. Cal. Oct. 28, 2016). Similarly, in Panarello, the magistrate judge recommended that the question of whether “specific” representations are required to state an implied certification claim be certified for interlocutory appeal to the Second Circuit, although that issue remains pending before the district court. No. 11-CV-00353, Dkt. No. 96, at 9 (W.D.N.Y. Nov. 14, 2016).

2. Application of Escobar’s “Demanding” Materiality Standard

In Escobar, the Supreme Court not only adopted the implied certification theory in some circumstances, but also reframed the FCA’s materiality standard as a question of whether a violation of the specific statute, regulation, or requirement at issue would actually have affected the government’s decision to pay for a claim had it known of the alleged noncompliance. 136 S. Ct. at 1996. In so doing, the Court made clear that whether the particular statutory, regulatory or contractual requirement at issue is specifically labeled a condition of payment remains relevant, but is not dispositive of its materiality, because it is not enough that the government merely have the option not to pay a claim. Id. The Court also stated that the FCA’s materiality requirement is “demanding” and “rigorous.” Id. at 2003–2004 n.6.

Since Escobar, courts have reached differing conclusions as to the decision’s impact on the FCA’s materiality analysis. Several courts have interpreted Escobar as now requiring plaintiffs to plead that: (i) the government either actually does not pay claims that involve violations of the statute or regulation at issue, or (ii) the government was unaware of the violation but “would not have paid” the claims at issue “had it known of” the alleged violations. See, e.g., United States ex rel. Southeastern Carpenters Reg’l Council v. Fulton County, Georgia, No. 1:14-CV-4071, 2016 WL 4158392, at *8 (N.D. Ga. Aug. 5, 2016); Knudsen v. Sprint Commun. Co., No. C13-04476, 2016 WL 4548924, at *14 (N.D. Cal. Sept. 1, 2016); Lee, 2016 WL 4703653, at *12.

In one of the first appellate court decisions on the issue, the Seventh Circuit held that a relator must provide “evidence that the government’s decision to pay” a claim “would likely or actually have been different had it known of [the defendant’s] alleged noncompliance” with the statute, rule, or regulation at issue. Sanford–Brown, 840 F.3d at 447. The court affirmed summary judgment for the defendant, concluding that the alleged noncompliance was not material to the government’s decision to pay claims because the government had “already examined” the alleged misconduct “multiple times over and concluded that neither administrative penalties nor termination was warranted.” Id. at 447–48.

Similarly, in a case discussed in further detail below, the First Circuit concluded that allegations that a defendant’s purported misconduct “could have” influenced “the government’s payment decision” failed to satisfy the “demanding” materiality standard set by Escobar. United States ex rel. D’Agostino v. ev3, Inc., No. 16-1126, — F.3d —, 2016 WL 7422943, at *5 (1st Cir. Dec. 23, 2016). There, in holding the relator had not adequately alleged materiality, the First Circuit also relied on the fact that the government “ha[d] not denied reimbursement” for the claims at issue (nor had it taken any other regulatory actions) despite having been made aware of the allegations of the defendant’s fraudulent conduct six years earlier. Id. In this regard, D’Agostino appears to be somewhat in tension with the First Circuit’s opinion on remand in Escobar, discussed below, in which a different panel of the court distinguished the government’s mere awareness of alleged misconduct from actual knowledge that the misconduct occurred, holding that a relator could still satisfy the materiality requirement despite evidence of the former.

And some courts have even gone further, interpreting Escobar‘s “demanding” materiality standard as requiring a relator’s complaint to “explain why” the government would not have paid claims at issue had it known of the alleged violation, as opposed to simply alleging that the government would not have paid. United States ex rel. Dresser v. Qualium Corp., No. 5:12-CV-01745-BLF, 2016 WL 3880763, at *6 (N.D. Cal. July 18, 2016) (emphasis added); United States ex rel. Scharff v. Camelot Counseling, No. 13-cv-3791, 2016 WL 5416494, at *8–9 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 28, 2016) (granting motion to dismiss, in part, because relator did not “explain why the purportedly fraudulent conduct was material to the payment of reimbursements”).

On the other hand, some courts have applied a more lenient standard of materiality, in spite of the Court’s language in Escobar. Under this more lenient standard, alleged violations may still be material even where the government takes no action despite being aware of the alleged violations. In Rose, for example, the court denied the defendant summary judgment as to materiality even though defendant argued that the government had “continued to pay [claims] despite having knowledge of the allegations in this case,” and had enforced compliance with the regulation at issue in the past largely by requiring corrective actions or imposing fines rather than by revoking payment. 2016 WL 5076214, at *4. The court reasoned that “[n]othing in Escobar suggests that actions short of a complete revocation of funds are irrelevant to the court’s materiality analysis” and found that a jury could conclude that the alleged noncompliance was material because it was “‘capable of influencing’ the government’s payment decisions” even though it apparently had not done so in the past. Id. at *7 (quoting 31 U.S.C. § 3729(b)(4)). Further clarity on this issue appears to be on the horizon as the district court certified this issue as part of the interlocutory appeal to the Ninth Circuit. Rose, 2016 WL 6393513, at *1.

Decisions from two circuit courts in which relators have been able to satisfy the “demanding” materiality standard also underscore the continued importance of “conditions of payment” and participation, even after Escobar‘s admonition that evidence of conditions of payment is not “automatically dispositive” of materiality. 136 S. Ct. at 2003.

The First Circuit, on remand in Escobar, concluded that the relators’ bare allegation that the government “would not have paid” the allegedly false claims at issue “had it known of the [alleged] violations” was sufficient to establish materiality. United States ex rel. Escobar v. Universal Health Servs., Inc., 842 F.3d 103, 111 (1st Cir. 2016). The First Circuit also relied in part on the fact that the allegedly violated regulatory requirements were “sufficiently important to influence the behavior” of the government in deciding whether to pay the claims because they are conditions of payment, indicating that whether a regulation is a condition of payment may remain important even after Escobar. Id. at 110. The First Circuit also rejected the defendant’s argument that the government continued to pay claims despite being aware of the alleged regulatory noncompliance, holding that “mere awareness of allegations concerning noncompliance with regulations” was not enough to show the violations were immaterial. Id. at 112. The court left the door open, however, to the notion that evidence of the government’s payment despite its “knowledge of actual noncompliance” with the regulation at issue (as opposed to mere awareness of allegations of noncompliance) could be enough to demonstrate a violation is not material. Id.

The Eighth Circuit reached a similar conclusion on summary judgment in another case remanded for reconsideration in light of Escobar. See United States ex rel. Miller v. Weston Educ., Inc., 840 F.3d 494, 504 (8th Cir. 2016). Miller involved allegations that the defendant violated the FCA by fraudulently inducing the Department of Education to provide educational funding under Title IV of the Higher Education Act of 1965, by allegedly falsely promising to comply with student recordkeeping requirements. Id. at 497. Before Escobar, the district court granted summary judgment to the defendant, holding that the alleged noncompliance was immaterial. Id. at 505. The Eighth Circuit reversed that decision, reasoning that the government viewed the recordkeeping requirement as material because it was a condition of participation in Title IV funding. The Supreme Court vacated and remanded that opinion for reconsideration in light of Escobar.

On remand, the Eighth Circuit doubled down on its denial of summary judgment on materiality, again relying on evidence that the government conditioned participation in Title IV programs on compliance with the regulatory recordkeeping requirement. Id. at 504. The court held under Escobar, “a false promise to comply with express conditions is material if it would affect a reasonable government funding decision or if the defendant had reason to know it would affect a government funding decision.” Id. at 504. Applying this standard, the Eighth Circuit held that the government’s repeated conditioning of participation in Title IV funding programs on compliance with the recordkeeping regulation in the statute and elsewhere was sufficient evidence to demonstrate materiality, even as it acknowledged that “conditioning is not ‘automatically dispositive’ of materiality.” Id. (quoting Escobar, 136 S. Ct. at 2003).

B. The Supreme Court Addresses the Effect of Seal Violations

The Supreme Court’s foray into the FCA this year was not limited to Escobar–the Court also considered whether a violation of the FCA’s seal requirement mandates dismissal of a relator’s complaint. The FCA provides that a complaint shall be kept under seal for a statutorily mandated period, but is silent as to the result of a violation of that provision, which had led the circuit courts to impose varying consequences, including dismissal, for such a violation. 31 U.S.C. § 3730(b)(2).

On December 6, 2016, in State Farm Fire & Casualty Co. v. United States ex rel. Rigsby, a unanimous Court held that “a seal violation does not mandate dismissal.” 137 S. Ct. 436, 438 (2016). In Rigsby, the relators’ counsel violated the seal provision by e-mailing a sealed filing to several journalists. Id. at 441. The sealed filing disclosed the qui tam complaint and the underlying allegations that an insurer submitted false claims by misclassifying wind damage as flood damage in order to shift insurance liability to the government. Id. Although none of the media outlets revealed the existence of an FCA complaint, each published the underlying allegations of fraud. Id. The relators also met with a Congressman who spoke publicly about the purported fraud, but similarly did not disclose the existence of the FCA suit. Id.

In determining that a seal violation does not necessitate dismissal, the Supreme Court relied on the text and purpose of the FCA. The Court explained that Congress mandated automatic dismissal for certain violations of the FCA, but did not do so for violations of the statute’s seal provision. Id. at 443. As such, the Court decided not to read an automatic consequence of dismissal into the statute. Id. The Court also reasoned that because the “seal requirement was intended in main to protect the Government’s interests,” a rule mandating automatic dismissal for violations would be unduly harsh and undermine the very interests the provision was meant to protect. Id.

The Court declined, however, to resolve the circuit split over the proper test for deciding whether dismissal is warranted for a seal violation. The Fifth and Ninth Circuits employ a three-part test, balancing (1) the actual harm to the Government, (2) the nature of the violations, and (3) evidence of bad faith. United States ex rel. Lujan v. Hughes Aircraft Co., 67 F.3d 242, 245–46 (9th Cir. 1995); United States, ex rel., Rigsby v. State Farm Fire & Cas. Co., 794 F.3d 457, 470–71 (5th Cir. 2015), aff’d 137 S. Ct. 436. The Second and Fourth Circuits employ an “incurable frustration” test that looks to whether the disclosure incurably frustrates four relevant interests of the FCA: (1) allowing the government time to investigate and decide whether to intervene; (2) protecting defendants’ reputations from meritless actions; (3) protecting defendants from having to answer complaints without knowing whether the government or relators will pursue the litigation; and (4) incentivizing defendants to settle to avoid the unsealing of a case. See United States ex rel. Pilon v. Martin Marietta Corp., 60 F.3d 995, 998–99 (2d Cir. 1995) (discussing interests that can be “incurably frustrated” due to seal violation); Smith v. Clark/Smoot/Russell, 796 F.3d 424, 430 (4th Cir. 2015) (following Pilon). Although the Supreme Court noted the factors in the three-part test “appear to be appropriate,” it went no further, stating that it was “unnecessary to explore” the issue until “later cases.” Rigsby, 137 S. Ct. at 444.

Even though the Court did not mandate automatic dismissal of qui tam suits for seal violations, FCA defendants can take solace in the fact that the Supreme Court at the least left lower courts with the discretion to dismiss cases where the seal has been violated, depending on the circumstances. And the Court may very well address what it considers to be the proper test for such a determination in the future.

C. The First Circuit Cabins FCA Liability Based on Alleged Fraud on the FDA

The First Circuit’s decision in D’Agostino, discussed above, is also notable in that it effectively forecloses alleged fraud perpetrated on the FDA as a basis for FCA liability, with the potential exception of where FDA has actually withdrawn pre-market approval of a medical device based on such fraud. 2016 WL 7422943, at *5. The relator in D’Agostino predicated his FCA claim on allegations that the defendants had made fraudulent misstatements in seeking pre-market approval to FDA for the defendant’s medical device, including that the defendants allegedly disclaimed uses for the device they later pursued, overstated the training they would provide for the device, and omitted critical safety information from the information provided to FDA. Id. at *4–5. According to the relator, FDA would not have approved of the device had it known of the fraudulent statements and, thus the statements ultimately led to a different government agency’s payment of claims for use of that device (which that agency would not have done but for the FDA’s pre-market approval). Id. at *5.

The First Circuit definitively rejected the relator’s fraud on the FDA theory of FCA liability. First, the court reasoned that the relator did not allege that the purported misrepresentations “actually cause[d] the FDA to grant approval it otherwise would not have granted” and, therefore, that he had not demonstrated the required causation between the alleged false statements and disbursement of government funds for the device. Id. at *4–6. Indeed, the court observed that FDA had not withdrawn its pre-market approval of the device, nor had it taken any other action (such as imposing post-approval requirements or suspending approval), despite having been aware of the alleged fraudulent statements for six years. Id. at *6. Second, the Court invoked important policy justifications for its holding, recognizing that “[t]o rule otherwise would be to turn the FCA into a tool with which a jury of six people could retroactively eliminate the value of FDA approval and effectively require that a product largely be withdrawn from the market even when FDA itself sees no reason to do so.” Id. In addition to unjustifiably allowing private parties to override FDA rulings, the First Circuit recognized such a course would be fraught with practical problems, such as deterring new device approval applications, and requiring courts to attempt to determine whether or not “FDA would not have granted approval but for the fraudulent representations” made by the applicant. Id.

Though the First Circuit’s decision reins in future use of fraud-on-FDA theory in the FCA context, the decision leaves open the possibility that such a theory could potentially support a viable FCA claim where FDA had, in fact, made the decision to withdraw its approval of a device after discovering fraud perpetrated during the pre-market approval process. Id. The court, however, expressly declined to resolve whether a relator would be able to state a viable FCA theory under those circumstances. Id.

D. Developments Relating to Rule 9(b) Pleading Requirements in FCA Cases

One issue that has been the subject of many cases over the last several years is what a plaintiff must plead to satisfy Rule 9(b)’s particularity requirement in an FCA case, and therefore survive a motion to dismiss. There have been at least two interesting developments on this front over the last six months relating to: (1) plaintiffs’ attempts to use statistical evidence to satisfy their pleading burden, and (2) whether and when Rule 9(b)’s particularity requirements should be relaxed in certain circumstances.

1. The First Circuit (and Potentially Fourth Circuit) Explore the Limits on Use of Statistical Sampling in FCA Cases

Recognizing that it can be difficult for some plaintiffs to plead actual facts demonstrating that claims submitted by defendants to the government are false on their face, plaintiffs (primarily relators) have begun regularly attempting to plead “falsity” through statistical sampling. Relators attempt to show that although they cannot allege that a claim submitted to the government is false by comparing the content of the claim to actual facts, they claim the totality of background facts show statistically that it is likely that the statements made on or in connection with a claim were false.

The First Circuit highlighted the difficulties plaintiffs face in overcoming Rule 9(b)’s particularity requirements when using this method to plead an FCA case. In Lawton ex rel. United States v. Takeda Pharm. Co., the relator alleged that the defendant had caused “false” claims to be submitted to the government by third parties as a result of the defendant “engag[ing] in an illegal off-label marketing campaign” for one of its drugs. 842 F.3d 125, 131 (1st Cir. 2016). Because the relator could not demonstrate that any of the particular claims ultimately submitted to the government were actually tainted by this alleged illegal activity, the relator attempted to rely upon statistical evidence that Medicare and Medicaid funds were used to pay for prescriptions of the drug between 2003 and 2012. Id. at 128–32.

The First Circuit rejected relator’s attempts and affirmed dismissal of his claims, holding they were not enough to satisfy even a “flexible” Rule 9(b) pleading standard. The First Circuit stated that although a relator could use “factual or statistical evidence . . . without necessarily providing details as to each [submitted] false claim,” a relator still must identify, among other things, “specific medical providers who allegedly submitted false claims,” the “rough time periods, locations, and amounts of the claims,” and “the specific government programs to which the claims were made.” Id. at 130-31 (emphasis added). The First Circuit concluded that the relator’s statistical evidence in Lawton was not enough to satisfy Rule 9(b) because he merely “point[ed] to the amounts of Medicare and Medicaid funds used to pay for [the] prescriptions” and concluded a “portion of [the] funds must have been used to pay unlawful claims”–saying nothing of who submitted the false claims or when they were submitted. Id. at 132.

Lawton demonstrates that even a nominally “relaxed” Rule 9(b) standard for “statistical evidence” relating to third party submissions of claims remains demanding. Moreover, Lawton makes clear that a relator may not sidestep Rule 9(b)’s requirements that a relator plead the “who, what, when, where, and how of the alleged fraud” simply by pleading statistical evidence. Id. at 130.

Although not in a case involving the pleadings stage, the Fourth Circuit also appeared ready to weigh in on this issue. On October 26, 2016, it heard oral argument in United States ex rel. Michaels v. Agape Senior Community, Inc., No. 15-2145 (4th Cir. 2016). In that case, as we reported in our 2015 Year-End Update, the district court rejected the relators’ request to use statistical sampling to prove liability for the allegedly false claims at issue and to prove damages. The district court found that the case was not suited for sampling because the underlying medical charts for all the claims at issue were “intact and available for review” to determine whether “certain services furnished to nursing home patients were medically necessary.” Michaels, No. 0:12-3466-JFA, 2015 WL 3903675, at *7, *8 (D.S.C. June 25, 2015).

Despite agreeing to hear the issue, the Fourth Circuit indicated during oral argument that it may not ultimately reach the statistical sampling issue, instead ruling on jurisdictional grounds. Oral Arg., Michaels, No. 15-2145 (4th Cir. 2016), http://coop.ca4.uscourts.gov/OAarchive/mp3/15-2145-20161026.mp3. If true, this will come as a disappointment to defendants who had hoped the Fourth Circuit might provide much-needed clarity on the use of statistical sampling in FCA cases.

2. The Sixth and Seventh Circuits Embrace Relaxed Pleading Requirements in Certain Cases

As we have previously reported, the circuits have in the past split on the proper Rule 9(b) pleading standard for FCA cases. Although the precedents defy easy categorization, generally speaking the Fourth, Eighth, Tenth, and Eleventh Circuits apply a somewhat heightened pleading standard, requiring identification of at least one claim for payment that is false,[80] while several other circuits (including the First, Fifth, Seventh, Ninth, and D.C. Circuits) use a less stringent pleading standard, allowing claims based on allegations of particular details of a scheme to submit false claims paired with reliable indicia that lead to a strong inference that false claims were actually submitted.[81]

The Sixth Circuit recently adopted a relaxed Rule 9(b) pleading standard, at least for certain FCA cases. Over the years, the Sixth Circuit has left open the door for a relaxed pleading standard, and it has now taken at least one step across the threshold with United States ex rel. Prather v. Brookdale Senior Living Communities, Inc., 838 F.3d 750, 773 (6th Cir. 2016). There, the court held that the relator need not identify an actual false claim or produce an actual billing or invoice to survive a motion to dismiss, at least where a relator has “personal billing-related knowledge that support[s] a strong inference that specific false claims were submitted.” Id. at 769, 773. In reaching its decision, the Sixth Circuit explained that a rigid, heightened Rule 9(b) pleading standard would “undermine the effectiveness of the [FCA].” Id. at 772.

The Seventh Circuit also further explored the bounds of its relaxed Rule 9(b) pleading standard. In United States ex rel. Presser v. Acacia Mental Health Clinic, LLC, the Seventh Circuit held that the Rule 9(b) pleading standard may be relaxed even where a relator lacks all the facts necessary to detail her claim. 836 F.3d 770, 778 (7th Cir. 2016). The Seventh Circuit clarified that, although the complaint must provide “plausible” grounds for the relator’s suspicions, a relator’s specific billing knowledge provides enough of an “inference” of fraud to meet the Rule 9(b) pleading requirements even if the relator does not “present, or even include allegations about, a specific document or bill that the defendants submitted to the Government.” Id. at 777–78. To be sure, the Seventh Circuit stated the relaxed standard still requires the relator to demonstrate how the allegedly wrongful scheme could fairly be understood as “unusual” or fraudulent, but it recognized a relator need not identify a specific false claim. Id. at 780.

E. Developments Relating to the FCA’s Scienter Requirements

The FCA’s liability provisions provide that a defendant violates the FCA only if the defendant acts “knowingly.” 31 U.S.C. § 3729(a)(1) (emphasis added).

The Eighth Circuit and Sixth Circuit recently issued opinions relating to the FCA’s scienter standard that are sure to be welcomed by FCA defendants.

1. The Eighth Circuit Dismisses an FCA Claim Based on an Objectively Reasonable Interpretation of a Regulation

For many years, defendants have argued that the FCA’s scienter requirement cannot be met where a false claim is premised on a vague or ambiguous regulatory, statutory, or contractual requirement. These arguments tend to rely on the Supreme Court’s statement in Safeco Ins. Co. Am. v. Burr, 551 U.S. 47, 70 n.20 (2007). Applying another federal statute with a knowledge standard identical to the FCA’s, the Supreme Court held in Safeco that where a statute, regulation, or contract would “allow for more than one reasonable interpretation, it would defy history and current thinking to treat a defendant who merely adopts one such interpretation as a knowing or reckless violator.” See also United States ex rel. Wilson v. Kellogg Brown & Root, Inc., 525 F.3d 370, 378 (4th Cir. 2008) (“An FCA relator cannot base a fraud claim on nothing more than his own interpretation of an imprecise contractual provision.”).

In United States ex rel. Donegan v. Anesthesia Assocs. of Kan. City, PC, the Eighth Circuit held that a defendant’s objectively reasonable interpretation of a government regulation precludes a finding the defendant “knowingly” submitted false claims in violation of this provision. 833 F.3d 874 (8th Cir. 2016). Donegan centered around use of the term “emergence” in a Medicare regulation authorizing reimbursement for anesthesiology services if the physician participated in a patient’s “induction and emergence.” Id. at 879. The Eighth Circuit concluded at the summary judgment stage that the meaning of “emergence” as used in the regulation was “ambiguous” because neither a “controlling source” nor a “professional bod[y]” responsible for “establish[ing] anesthesia standards” had defined the term. Id. at 878. Relying on evidence introduced by the defendant that the defendant had adopted standards defining “emergence” to include treatment administered in the recovery room (bolstered by expert testimony defining the term in the same manner), the Eighth Circuit found the defendant’s interpretation “objectively reasonable.” Id. As a result, it held that a defendant’s “reasonable interpretation of the ambiguous regulation” precluded a finding it knowingly submitted false claims in violation of the FCA. See id. at 880–81.

The Eighth Circuit cautioned, however, that a reasonable interpretation would not necessarily preclude summary judgment on the FCA scienter issue “if a Relator (or the United States) produce[d] sufficient evidence of government guidance that warn[ed] a regulated defendant away from an otherwise reasonable interpretation of an ambiguous regulation.” Id. at 879 (citations and marks omitted) (emphasis in original).