International Trade 2025 Year-End Update

Client Alert | February 6, 2026

The Trump administration re-entered the White House with an expansive vision for how international trade tools can be wielded to meet a range of “America First” policy goals. After one year in office, we have seen an unprecedented deployment of old and new tools of economic coercion wielded against allies and adversaries alike—with countermeasures wielded by them in response. Businesses, governments, and consumers throughout the world have found themselves on the front lines of this tit-for-tat throughout 2025, experiencing significant uncertainties and challenges that will only increase in 2026.

Upon his return to the White House in January 2025, President Trump quickly promulgated “America First” Trade and Investment Policies, laying out roadmaps for the administration’s priorities and methodologies to achieve its strategic objectives. One year into the administration, it is clear that implementation of these policies has pushed economic statecraft to new, untested limits.

Certain cornerstones of U.S. trade policy have carried over with the new administration, including robust imposition and enforcement of sanctions and export controls and the policy stance that the United States is open for foreign investment. However, the first year of the second Trump administration has been set apart by the dominance of an additional tool of economic coercion—the unprecedented use of tariffs, including (even more innovatively) the newly emerged “secondary tariff.” Deployed as a negotiating tool against strategic rivals and core partners alike, tariffs have emerged as the administration’s favored tool to achieve foreign policy, national security, and domestic economic objectives. The novel imposition of tariffs pursuant to the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977, a decades-old statute that underpins the vast majority of U.S. sanctions and other trade-related initiatives such as outbound investment regulations, has further pushed the limits of U.S. law—so much so that the U.S. Supreme Court is set to weigh in on their legality in the coming weeks or months.

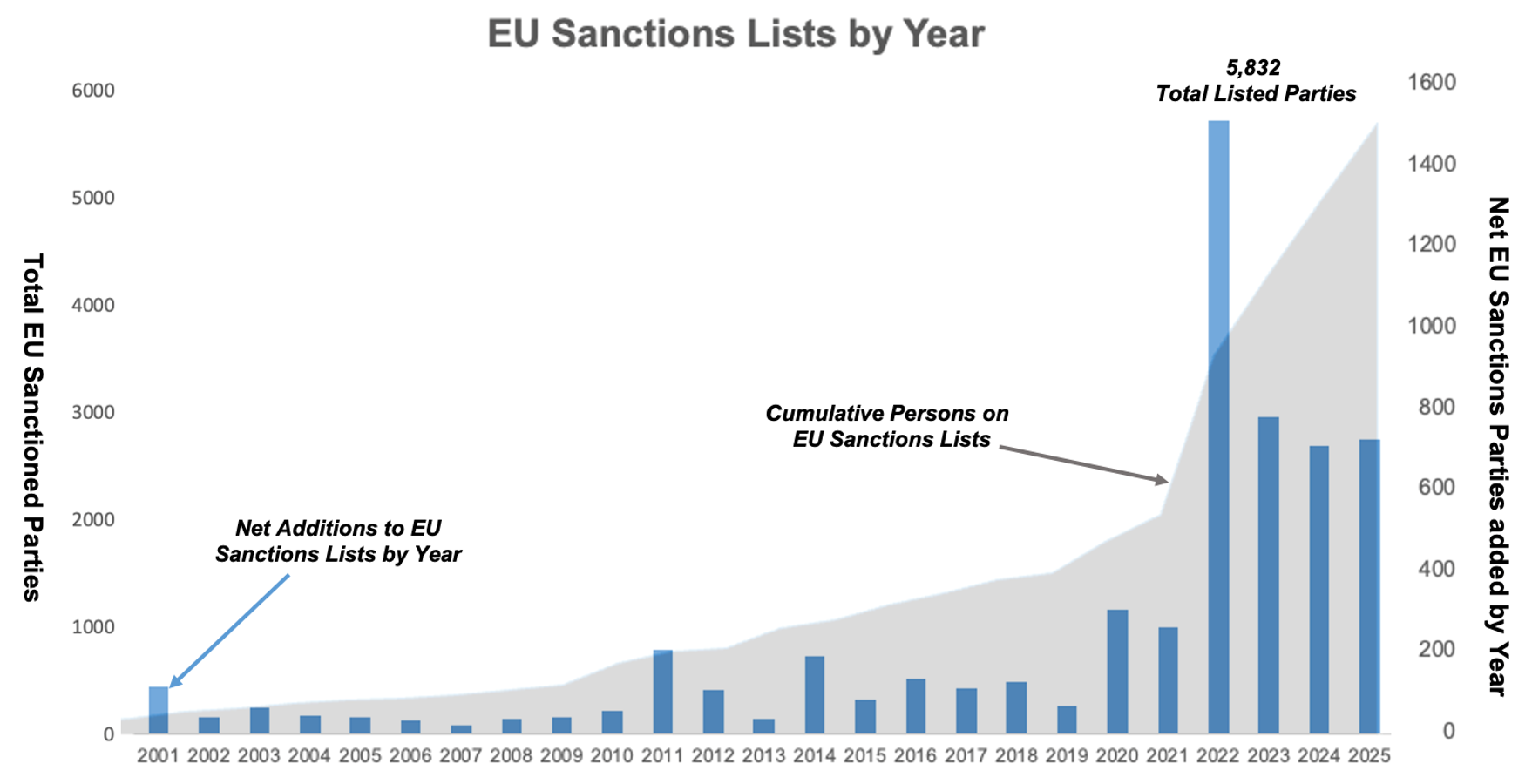

As Washington initiated fundamental shifts and policy reorientations, the European Union and the United Kingdom continued to build on the groundwork they have been laying over the last few years, cementing trade controls as strategic pillars of their foreign policies rather than solely reactive measures or follow-on tools to what the United States may impose. The EU Member States’ increased alignment of sanctions violations penalties and the United Kingdom’s establishment of a new sanctions enforcement body enhance enforcement risk for multinational firms that have until now primarily had to contend with U.S. enforcement agencies.

The United States and its traditional allies have undoubtedly experienced friction in connection with evolving policy approaches throughout 2025. However, the year also showed important signs of continued collaboration amidst common goals and strategic priorities. The snapback of EU and UK sanctions on Iran brought those sanctions regimes into closer alignment with the United States, which continued to ramp up pressure on Iran—the primary focus of new U.S. sanctions designations in 2025. Coordinated EU, UK, and U.S. sanctions targeting Russia’s largest oil producers struck at the core of Russia’s hard currency revenue streams, as efforts to broker peace between Moscow and Kyiv stalled. This alignment even extended to the lifting of sanctions, as all three jurisdictions moved to ease long-standing restrictions on Syria after the Assad regime was deposed and new leadership emerged.

Still, as renewed threats of tariffs dominated the news cycle in the early weeks of 2026, “America First” is poised to continue driving the Trump administration’s approach to trade controls in the coming years, with immediate and long term consequences for allies and geostrategic competitors. As a result, the increased uncertainty that characterized 2025 is unlikely to subside in the year ahead.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Iran

Russia

Syria

Venezuela

Counter-Terrorism and Counter-Narcotics

International Criminal Court

Enforcement Trends

Artificial Intelligence

End-User Controls

ITAR Updates

Licensing Trends

Enforcement Trends

Other BIS Regulatory Regimes

III….U.S. Foreign Investment Restrictions

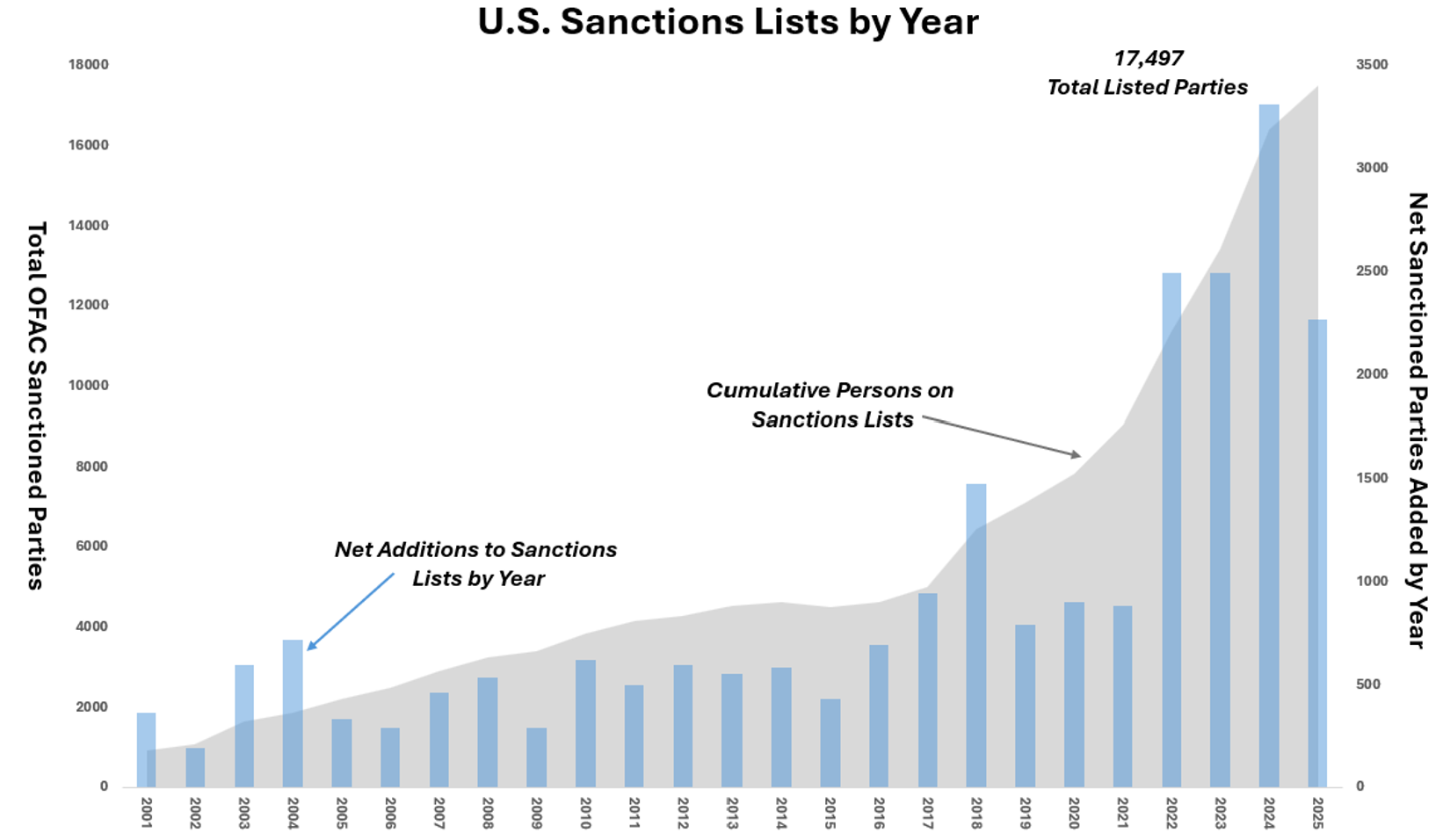

The total number of U.S. sanctioned parties continued to climb in 2025. As always, however, the numbers only tell part of the story.

|

Iran supplanted Russia as the chief target of new list-based U.S. sanctions, accounting for around half of all designations by the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) in 2025. While the year reflected a substantial number of new sanctions designations, hundreds of parties in Syria were also de-listed as the Trump administration lifted a comprehensive embargo to give breathing room to the new Syrian government.

And in stark contrast to the Biden administration, the Trump administration’s deployment of economic tools was often prelude to its deployment of military tools. The reimposition of “maximum pressure” on Iran in the first days of the new Trump administration, including a relentless series of sanctions on Tehran’s revenue sources and defense networks, escalated by mid-year into U.S. airstrikes targeting Iranian nuclear facilities. Unprecedented designations of cartels and drug trafficking groups as terrorist organizations foreshadowed U.S. military strikes on alleged drug smuggling boats in the Caribbean. A tightening of sanctions targeting Venezuela’s energy sector was followed by oil tanker seizures and, at the start of 2026, a stunning U.S. military operation in Caracas to capture Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro.

Relations between the United States and Iran entered a volatile phase during 2025 as President Trump, within days of re-entering the Oval Office, announced the resumption of his first term’s “maximum pressure” campaign against Tehran. In a bid to deny Iran a nuclear weapon, halt its ballistic missile program, and disrupt its destabilizing activities abroad, the new U.S. administration accelerated the pace of Iran sanctions designations, pressed the regime to return to the negotiating table, and, in June, launched an airstrike against three Iranian nuclear facilities.

The Islamic Republic—alongside a small handful of other jurisdictions, including Cuba, North Korea, and certain Russian-occupied regions of Ukraine—remains subject to comprehensive U.S. sanctions, as a result of which U.S. persons are generally prohibited from engaging in almost any dealings involving Iran. In addition to those restrictions, during 2025 OFAC added to its Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons (SDN) List nearly one thousand individuals, entities, vessels, and aircraft tied to high-priority sectors of the Iranian economy. Frequent targets of Iran-related sanctions designations included parties allegedly involved in:

- The Iranian petroleum and petrochemicals trade, with a particular focus on shippers and vessels comprising the Iranian “shadow fleet,” along with China-based importers and refiners of Iranian crude;

- The Iranian shadow banking system, including parties using neighboring states such as the United Arab Emirates as sanctions evasion and transshipment hubs; and

- The Iranian defense sector, including nuclear, ballistic missile, and unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) procurement networks.

The United States was not alone in pressuring Iran. The U.S. attack on Iranian nuclear targets took place alongside Israel’s 12-day war in June 2025, which battered the Islamic Republic’s air defenses and domestic political standing. Iran’s economic and diplomatic isolation further deepened in September 2025 with the snapback of UN, EU, and UK sanctions (discussed further below) that for the past decade had been suspended under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA)—commonly known as the Iran nuclear deal. By early 2026, Tehran found itself mired in a deepening currency crisis, roiled by anti-government demonstrations, and bracing for possible U.S. military action as the regime brutally cracked down on protesters.

Barring further dramatic developments on the ground, the Trump administration appears set to continue prosecuting its maximum pressure campaign throughout the near future. In light of the President’s stated objective of driving Iranian oil exports to zero, further sanctions designations targeting shipping companies, vessels, oil traders, and financial institutions dealing in Iranian barrels are likely on the horizon. As seen in Venezuela, it is possible that the Trump administration may take to boarding and seizing vessels carrying Iranian crude. It is also conceivable that the Trump administration could in coming months begin targeting larger, more economically consequential parties based in the People’s Republic of China (PRC)—by far the largest remaining buyer of Iranian crude—though at the risk of upsetting the fragile trade truce between Washington and Beijing.

Following a three–year period in which the United States, in concert with its allies and partners, imposed historic trade restrictions on Russia, the pace of new U.S. sanctions targeting Russia slowed in 2025 as President Trump sought to broker peace between Moscow and Kyiv. When talks failed to end the fighting in Ukraine, the United States intensified pressure on Russia’s crucial energy sector, including by increasing tariffs on a key buyer of Russian crude, blacklisting two Russian oil majors, and threatening sharply higher duties on countries that import Russian energy.

Similar to the strategy adopted by the prior U.S. administration as it worked to coax Iran to resume nuclear negotiations, President Trump unveiled no new sanctions on Russia during his first six months in office in a seeming effort to create space for peace talks to progress. However, the Trump administration’s patience with Moscow appeared to wear thin in August 2025 when, on the eve of a major summit between Presidents Trump and Putin, the White House announced unprecedented “secondary tariffs” on India stemming from Delhi’s continued purchases of Russian oil. From a policy perspective, that novel measure—which involves levying increased duties on all Indian-origin goods entering the United States, rather than penalizing specific firms involved in the Russian oil trade—appears calculated to limit the Kremlin’s ability to finance its war effort by deterring foreign governments from allowing Russian petroleum and petroleum products into their territories. As part of a reported U.S.–India trade deal, President Trump indicated in early February 2026 that the United States had agreed to reduce tariffs on India, which will in turn stop buying Russian oil. The effectiveness of these measures in halting the war in Ukraine will likely hinge on whether the Trump administration is prepared to impose similar restrictions on China, the world’s most prolific consumer of Russian oil.

As peace negotiations dragged on, President Trump in October 2025 ratcheted up pressure on Russia’s energy sector by imposing full blocking sanctions on the country’s two largest oil producers, Rosneft and Lukoil. Blocking sanctions are arguably the most potent tool in a country’s sanctions arsenal, especially for countries such as the United States with an outsized role in the global financial system. Upon becoming designated an SDN (or other type of blocked person), the targeted individual or entity’s property and interests in property that come within U.S. jurisdiction are blocked (i.e., frozen) and U.S. persons are, except as authorized by OFAC, generally prohibited from engaging in transactions involving the blocked person. The SDN List therefore functions as the United States’ principal sanctions-related restricted party list. Moreover, the effects of blocking sanctions often reach beyond the parties identified by name on the list. By operation of OFAC’s “50 Percent Rule,” restrictions generally also extend to entities owned 50 percent or more in the aggregate by one or more blocked persons, whether or not the entity itself has been explicitly identified on the list.

Although the U.S. government targeted relatively few Russia-related parties this past year—together representing a tiny percentage of new OFAC sanctions designations announced during 2025—Rosneft and Lukoil are among the largest and most economically consequential enterprises ever subjected to a U.S. asset freeze. The impact of those designations on the global oil market was further magnified by similar measures from the European Union and the United Kingdom (discussed further below). The joint designations represented a fundamental shift in U.S., EU, and UK thinking on Moscow. Ever since the Crimean invasion in 2014, the Western powers have carefully avoided blacklisting large parts of the Russian energy sector for fear of upsetting global markets and denying European and Japanese allies critical fuels they came to rely upon Russia to provide. No more. That the European Union followed this designation with a pronouncement that the bloc will be free of Russian oil purchases by 2027 underlined the rupture between Russia and what had been its principal markets.

President Trump, at least in the near term, appears set to maintain and potentially expand U.S. sanctions on Russian energy to maximize U.S. leverage in negotiations with Moscow. One option available to the administration to increase pressure on the Kremlin could involve urging the U.S. Congress to adopt the Sanctioning Russia Act—a bill spearheaded by Senators Lindsey Graham (R-SC) and Richard Blumenthal (D-CT) that enjoys bipartisan support on Capitol Hill and would authorize “bone crushing” secondary tariffs of up to 500 percent on all goods imported into the United States from any country that knowingly purchases Russian-origin oil, petroleum products, or uranium. It is also possible that the White House could threaten to impose “secondary sanctions” (i.e., penalties up to and including blocking use of the U.S. financial system or freezing all property interests) on foreign financial institutions that continue to process payments involving Russian petroleum and petroleum products. This would be an add-on to the Biden-era authority that threatens to impose secondary sanctions on foreign banks that process transactions involving Russia’s military-industrial base.

Conversely, if talks among Washington, Moscow, and Kyiv bear fruit, it would not be surprising if the White House were to quickly ease restrictions on dealings involving Russia. With the narrow exception of certain U.S. sanctions designations pursuant to Executive Order 13662, nearly all Biden- and Trump-era measures targeting Russia (which were implemented via Executive Order) can be rescinded with the stroke of a pen. For example, President Trump could narrow or revoke existing measures such as the prohibition on “new investment” in the Russian Federation set forth in Executive Order 14071 by issuing new or amended Executive Orders, or by issuing permissive general licenses. Any such relaxation of U.S. sanctions could, however, result in a split between the United States and its European allies and partners, who, to date, have shown little appetite for easing their own considerable restrictions on Russia, especially in light of the perceived broader threat that Russia poses to select EU Member States.

One of the most unexpected and consequential trade developments of 2025 involved the United States’ easing of sanctions on Syria. This policy change, announced by President Trump to the surprise of most observers while on a state visit to Saudi Arabia in May 2025, involved the White House quickly paring back most U.S. trade restrictions—including lifting comprehensive sanctions on Syria—as it sought to bolster the government of President Ahmed al-Sharaa and facilitate the country’s reconstruction. Although the continuing rapprochement between Washington and Damascus suggests that remaining restrictions could be eased in coming months, the new government still faces significant challenges in consolidating power, and it will take time for policymakers to disassemble the full suite of U.S. trade controls on Syria, some of which require an act of Congress to revoke.

In its first moves to unwind Syria restrictions, the United States in early 2025 issued two general licenses authorizing a steadily broader range of transactions involving Syria. The first such license, issued in January 2025, permitted U.S. persons to engage in certain limited transactions involving Syria’s post-Assad governing institutions, the country’s energy sector, and the processing of noncommercial, personal remittances. In May 2025, OFAC—in a move that foreshadowed more lasting sanctions relief to come—issued a separate general license authorizing U.S. persons to engage in substantially all transactions prohibited by the agency’s Syrian Sanctions Regulations, including making new investments in Syria, exporting services to Syria, and importing into the United States Syrian-origin petroleum or petroleum products.

Concurrent with that May 2025 announcement, the U.S. Department of State issued a 180-day waiver of certain provisions of the Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act of 2019 (the Caesar Act)—a statute that then mandated sanctions against non-U.S. persons that knowingly engage in certain significant transactions involving Syria—in a bid to reassure humanitarian aid organizations and prospective foreign investors considering re-entering the Syrian market.

As described in a prior client alert, President Trump in June 2025 built on those measures by issuing a groundbreaking Executive Order that replaces longstanding comprehensive sanctions on Syria with a targeted, list-based sanctions program that restricts dealings involving certain specified bad actors such as terrorist organizations and Assad regime insiders. Among other key changes, that order revoked the Syrian Sanctions Regulations, enabled the lifting of blocking sanctions on over 500 Syria-related parties, and allowed the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) to waive certain export controls, while the State Department set in motion a process to eventually rescind Syria’s designation as a State Sponsor of Terrorism (SST).

The United States continued to peel back layers of restrictions on Syria as 2025 wound down. The Commerce Department issued a final rule that, as of September 2025, authorizes exports to Syria of EAR99 items (i.e., goods, software, and technology that have purely civilian uses) to most end users under a new License Exception Syria Peace and Prosperity (SPP). In November 2025, the State Department lifted blocking sanctions on President al-Sharaa—until then, a designated terrorist—ahead of a White House summit with President Trump. Finally, in an apparent effort to provide more certainty for non-U.S. parties, Congress in December 2025 repealed the Caesar Act and its mandatory secondary sanctions, thereby eliminating a major deterrent to the large-scale, long-term capital investments that Syria will need to rebuild its shattered economy after a more than decade-long civil war.

Despite considerable U.S. sanctions relief over the past year, not all U.S. trade restrictions on Syria have been lifted. For example, Syria remains home to several hundred individuals and entities that are subject to U.S. blocking sanctions by virtue of appearing on OFAC’s SDN List. Syria also remains subject to a trade embargo under the U.S. Export Administration Regulations (EAR) as well as an arms embargo under the U.S. International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR), and the country continues to be designated an SST, with the result that U.S. foreign assistance and certain U.S. exports to Syria are restricted.

While more regulatory changes will be needed to prove that the new Syria is truly “open for business,” post-Assad Syria has been granted a meaningful opportunity to re-enter the global economy. In recent weeks, however, the Syrian government has made advances to reclaim control over large areas of territory in eastern and northern Syria, testing U.S. support of the new government as it has clashed with the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces that have been a key U.S. partner in the fight against the Islamic State. The further easing of U.S. restrictions targeting Syria may well hinge on how President al-Sharaa handles this and other challenges in coming months as he continues his efforts to unite his fractured nation.

Although traditional U.S. trade controls on Venezuela were largely quiet for much of the past year, sanctions tell only part of the story. President Trump during 2025 renewed his first term’s hardline focus on the regime of President Nicolás Maduro, including by massing forces in the Caribbean, striking alleged drug-trafficking vessels, partially blockading Venezuela’s coast, seizing tankers carrying Venezuelan oil, and in early January 2026 launching a midnight raid that resulted in Maduro’s capture and extradition to the United States. As of this writing, Maduro’s top lieutenants remain in charge in Caracas and U.S. sanctions are mostly unchanged—though restrictions on Venezuela’s crucial oil sector have already been eased as the Trump administration looks to stem the flow of migrants and jumpstart Venezuela’s moribund economy.

U.S. sanctions on Venezuelan energy seesawed during the first half of 2025. Starting in March 2025, OFAC replaced a longstanding general license, which authorized certain transactions related to the operation and management by a U.S. energy company of its joint ventures involving the state-owned oil giant Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PdVSA), with a series of time-limited wind-down authorizations. The Trump administration allowed that license, along with a separate general license that permitted certain Venezuela-related dealings involving four named U.S. oilfield services companies, to expire in May 2025. According to news reports, the White House quietly reversed course in July 2025 by issuing one or more OFAC specific licenses authorizing the U.S. energy company at issue to resume many of its prior activities in Venezuela, including the exportation to the United States of Venezuelan-origin oil.

President Trump in parallel moved to deter shipments of Venezuelan oil to other jurisdictions, including by issuing an Executive Order in March 2025 authorizing secondary tariffs on all goods imported into the United States from any country determined by the U.S. Secretary of State to have imported Venezuelan-origin petroleum or petroleum products on or after a certain date. Unlike in the Russia context, the Trump administration has not yet levied any such duties. Indeed, in light of the apparent U.S. policy interest in reviving Venezuelan energy production following President Maduro’s January 2026 ouster, the threatened Venezuela-related tariffs seem unlikely to be implemented by the Trump administration, at least in the near term. Rather, an Executive Order signed by President Trump in late January 2026 authorizing secondary tariffs on any country determined to sell oil to Cuba may reflect a new approach by the administration in pursuit of its Western Hemisphere policy objectives.

As we observed in a prior client alert, although President Maduro has been removed from office, power in Caracas has not changed hands, and U.S. trade restrictions broadly remain the same. U.S. persons continue to be, except as authorized by OFAC, prohibited from engaging in transactions involving the Government of Venezuela, which is defined to include not just government agencies and political subdivisions, but also any entity that is majority-owned or controlled by the government. Consequently, U.S. persons (and non-U.S. persons when engaging in a transaction with a U.S. touchpoint) potentially risk triggering U.S. sanctions when dealing with an arm of the Venezuelan state, such as a state-owned enterprise like PdVSA or the country’s central bank. Over 400 parties, including public and private firms, presently appear on the SDN List pursuant to various Venezuela-related legal authorities.

The situation on the ground in Venezuela remains highly fluid. As U.S. sanctions targeting the Maduro regime are not codified in statute, they can be quickly eased through executive action—including, for example, issuing (or re-issuing) OFAC general licenses authorizing certain dealings involving the country’s energy sector, de-listing PdVSA, or conceivably lifting blocking sanctions on the entirety of the Government of Venezuela. As an initial step, the Trump administration announced plans to “selectively roll[] back sanctions to enable the transport and sale of Venezuelan crude and oil products to global markets.” Executive Order 14373 quickly followed, creating an untested mechanism for U.S. government oversight of certain Venezuelan oil revenues. OFAC in late January 2026 further paved the way for Venezuelan crude to be sold on legitimate global markets with the issuance of Venezuela General License 46, authorizing, subject to certain conditions, established U.S. firms to engage in transactions that are “ordinarily incident and necessary to the lifting, exportation, reexportation, sale, resale, supply, storage, marketing, purchase, delivery, or transportation of Venezuelan-origin oil, including the refining of such oil.”

A further easing of U.S. restrictions could be contingent upon the leadership in Caracas meeting certain milestones, such as curbing illicit drug trafficking and irregular migration, distancing itself from Cuba, Iran, China, and Russia, and perhaps taking concrete steps toward the restoration of Venezuelan democracy.

E. Counter-Terrorism and Counter-Narcotics

In addition to measures targeting countries such as Iran and Russia, the United States in 2025 vigorously used OFAC’s thematic sanctions programs, which are global in nature and seek to deter particular types of conduct such as human rights abuses or corruption no matter where they occur. In one of the signature trade developments of the past year, the Trump administration often wielded counter-terrorism and counter-narcotics sanctions authorities against novel targets, including drug cartels, organized crime groups, and sitting heads of state.

Following an election campaign in which he declared illegal immigration, violent crime, and drug trafficking to be core national priorities, on Inauguration Day, President Trump signed an Executive Order declaring it the policy of the United States to ensure the “total elimination” of cartels and transnational criminal organizations—and setting in motion a process to name such groups Specially Designated Global Terrorists (SDGTs) and Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTOs). During 2025, the Trump administration applied the more restrictive FTO label—which can trigger criminal, civil, and reputational consequences for parties that engage with such organizations—to a record-shattering 25 new entities. Such counter-terrorism designations (or, in many cases, re-designations) targeted major Mexican drug cartels and South American criminal enterprises such as Tren de Aragua, as well as Yemen’s Ansarallah (commonly known as the Houthis) and several European anti-fascist groups.

SDGT and FTO designations are similar in that each involves the imposition of U.S. blocking sanctions. Upon becoming designated an SDGT, an FTO, or other type of blocked person, the targeted individual or entity’s property and interests in property that come within U.S. jurisdiction are blocked and U.S. persons are, except as authorized by OFAC, generally prohibited from engaging in transactions involving the blocked person and their majority-owned entities.

The chief difference between those two types of counter-terrorism designations is that being named an FTO triggers further, onerous restrictions that are unique among U.S. sanctions programs. In particular, designation as an FTO results in the targeted organization becoming blocked and also (1) renders representatives and members of the FTO, if they are not U.S. citizens or U.S. nationals, inadmissible to the United States; (2) exposes persons subject to U.S. jurisdiction to criminal liability for knowingly providing “material support or resources” to the FTO; and (3) gives rise to a private right of action in which terrorism victims can bring civil suits against, and seek treble damages from, parties that knowingly provide “substantial assistance” to an FTO. Certain dealings with SDGTs (a list which, as of today, also includes all FTOs) can further trigger U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission reporting obligations.

Historically, U.S. counter-terrorism sanctions (and their attendant consequences) have been reserved mostly for Islamist militant groups based in the Middle East and South Asia, such as al-Qaeda and ISIS. The Trump administration’s unprecedented use of counter-terrorism authorities to target apolitical, profit-driven groups based in the Western Hemisphere presents substantial practical challenges for enterprises operating in Latin America. For example, Mexico-based cartels are tightly integrated into the legitimate economy of a major U.S. trading partner and seldom appear by name on invoices or other transaction documentation. Moreover, in light of the lower threshold for criminal liability and the possibility that a U.S. court could award substantial monetary damages, FTO designations can result in de-risking by financial institutions and other key business partners that may be prohibited from (or otherwise unwilling to engage in) transactions that could, directly or indirectly, involve such a named terrorist group. Accordingly, it is prudent for businesses with activities in Latin America and the Caribbean to conduct restricted party screening and enhanced due diligence to assess whether their current or prospective counterparties have links to newly designated terrorist organizations.

In tandem with counter-terrorism measures, the Trump administration has increasingly used U.S. counter-narcotics sanctions as a cudgel against left-leaning political figures in South America. Notably, the United States on multiple occasions this past year imposed sanctions on the Cartel de los Soles, purportedly led by Venezuela’s President Nicolás Maduro. In October 2025, the U.S. government, in a surprise action against a longstanding security partner and a Major Non-NATO Ally, designated the President of Colombia pursuant to a counter-narcotics authority following his vocal criticism of U.S. airstrikes off the Venezuelan coast.

In coming months, the Trump administration appears set to continue heavily using terrorism- and narcotics-related sanctions to advance the White House’s domestic policy priorities and discredit opponents abroad, even at the expense of dulling the moral sting that has traditionally accompanied the use of such tools.

F. International Criminal Court

The White House extended its aggressive use of OFAC’s thematic authorities by reviving a short-lived and unorthodox sanctions program—created under the first Trump administration and quickly dismantled by President Biden—targeting certain parties associated with the International Criminal Court (ICC).

In February 2025, President Trump issued an Executive Order resuscitating the ICC sanctions program, citing that body’s threat to the sovereignty of states, such as the United States and Israel, that are not party to the Rome Statute and have not consented to the ICC’s jurisdiction. Concurrent with that order, the United States imposed blocking sanctions on the court’s chief prosecutor, stemming from his involvement in the issuance of an arrest warrant against Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and former Defense Minister Yoav Gallant. As a result of further designations announced in June, July, August, September, and December 2025, the United States has added to the SDN List a total of 15 parties associated with the court, including specific judges, prosecutors, and nongovernmental organizations deemed to be supporting ICC investigations of Israeli nationals.

U.S. sanctions targeting the ICC are presently limited in scope. Although U.S. persons are restricted from engaging in transactions involving the 15 named parties associated with the ICC who appear on the SDN List (as well as those parties’ majority-owned entities), OFAC has indicated in various contexts that, as a general matter, “when a designated individual has a leadership role in a governing institution, the governing institution is not itself considered blocked.” Consequently, absent the involvement of a sanctioned party, U.S. persons are not generally restricted by OFAC sanctions from engaging in activities involving the ICC as an institution or its various organs, such as the Office of the Prosecutor, the Presidency, or the Judicial Divisions.

The return of U.S. sanctions targeting ICC personnel, including lawyers and jurists, highlights the Trump administration’s willingness to impose sanctions against non-traditional targets and without coordination with, or support from, traditional U.S. allies. This trend was reinforced by the July 2025 sanctions targeting Brazilian Supreme Federal Court Justice Alexandre de Moraes, one of only a few designations this year under OFAC’s human rights-focused Global Magnitsky sanctions (although Justice Moraes was removed from the SDN List by year’s end). If in the future the ICC were to launch an investigation into conduct by President Trump, other senior U.S. officials, or U.S. military personnel, it is possible that the United States could expand its existing sanctions to prohibit U.S. nexus dealings involving the ICC itself. Any such expansion is likely to be met with U.S. legal challenges, as certain U.S. district courts have already expressed skepticism of the legality of the current ICC sanctions on First Amendment grounds, at least as applied to certain U.S. citizens supporting the court’s activities.

2025 was a busy year for OFAC enforcement as the agency, across 14 enforcement actions, imposed a combined $265.7 million in fines—a fivefold increase over the prior year. That uptick was principally driven by a blockbuster $215.9 million penalty against a California venture capital firm stemming from alleged dealings involving a sanctioned Russian oligarch. But for that case, the aggregate amount of fines levied by OFAC would have been roughly on par with the agency’s five-year median of approximately $50 million in civil monetary penalties per year.

Notably, 8 of the 14 OFAC enforcement actions announced during 2025—including the five largest resolutions of the year—involved apparent Russia sanctions violations. While enforcement actions are often a trailing indicator of OFAC enforcement priorities, as matters can take several years to resolve after a potential violation has been identified, this trend nonetheless suggests that dealings involving the Russian Federation—and, in particular, Russian oligarchs—is likely to remain an area of continued enforcement for U.S. authorities in coming months.

We highlight below the most noteworthy compliance lessons from OFAC’s 2025 enforcement activity. Many of these takeaways were explicitly communicated by OFAC through the “compliance considerations” section included in the web notice for each of its enforcement actions:

- “Gatekeepers” can be subject to heightened sanctions compliance expectations: The role of gatekeepers—sophisticated U.S. parties such as investment advisors, accountants, attorneys, trust and corporate formation service providers, and real estate professionals—was a major theme of OFAC’s enforcement activity this past year. OFAC repeatedly emphasized that such individuals occupy positions of trust, have considerable access to information, and can lend a transaction involving a sanctioned party an air of legitimacy. Consequently, such professionals may be subject to heightened expectations to monitor for and detect potential sanctions evasion, and should conduct thorough due diligence into prospective clients to minimize the risk of their services facilitating a restricted party’s access to the U.S. financial system.

- Transaction parties should be alert to indications that a sanctioned party owns—or controls—property: Several of OFAC’s recent cases highlight the importance of understanding potential sanctioned-person control or influence over investments—even when such persons are not named in transaction documentation such as deeds, property records, or contracts. Professionals and professional services firms should be sensitive to the possibility that blocked persons may be indirectly involved in a transaction, including through proxies or opaque legal structures. OFAC has further cautioned that transaction parties and their advisors should avoid formalistic analyses and, where appropriate, look beyond nominal ownership to a transaction’s underlying practical and economic realities—a trend that puts considerable pressure on OFAC’s ownership-driven 50 Percent Rule and suggests that over time OFAC may move to an “ownership or control” test with respect to downstream sanctions impacts like that in place in the European Union and the United Kingdom.

- Transaction parties should heed OFAC blocking notifications and cease-and-desist orders: OFAC enforcement activity suggests that the agency is increasingly using notifications of blocking and cease-and-desist orders to alert interested parties to the existence of a blockable property interest before a sanctions violation (or further violation) occurs. Such notices can also be used by OFAC to show that a party had actual knowledge that a subsequent transaction involving that property might implicate the agency’s prohibitions. In at least two enforcement actions published in 2025, transaction parties appear to have disregarded such explicit warnings. Recipients of blocking notifications and cease-and-desist orders should take such notices seriously, closely scrutinize the person or property identified by the agency, and timely block and report to OFAC any property within U.S. jurisdiction in which a blocked person holds an interest.

- OFAC may be less willing to settle: Historically, the vast majority of OFAC enforcement actions resulting in monetary penalties were resolved with a settlement agreement. The issuance of a penalty notice—a mechanism by which OFAC unilaterally announces its determination that a violation of its regulations has occurred and imposes a penalty in whatever amount it deems appropriate—has been rare. In a departure from past practice, OFAC in 2025 resolved three cases, each involving a Russian oligarch and conduct that the agency deemed egregious, by issuing a penalty notice to the alleged violator in lieu of settling. Such resolutions, which have in the past often triggered a lawsuit by the enforcement target, appear calculated to convey to the regulated community that there are certain cases about which OFAC feels especially strongly and is prepared to litigate if necessary.

- OFAC is increasingly holding individuals accountable for U.S. sanctions violations: OFAC this past year imposed substantial civil monetary penalties against three unnamed individuals for providing professional services to blocked persons, breaking from the agency’s recent practice of levying fines almost exclusively against corporate entities. Indeed, prior to 2025, OFAC had penalized only five natural persons during the preceding ten years combined. The agency’s recent enforcement activity suggests that individual professional service providers should familiarize themselves with common “red flags” for sanctions risk, understand how their work could expose them to sanctions liability, and conduct careful due diligence on higher-risk clients.

Alongside robust civil enforcement by OFAC, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) announced in May 2025 that it would prioritize criminal enforcement of sanctions evasion. In a memorandum detailing its new White Collar Enforcement Plan, DOJ’s Criminal Division directed its prosecutors to focus on, among other top priorities, national security offenses, including pursuing “gatekeepers, such as financial institutions and their insiders that commit sanctions violations or enable transactions” by drug cartels, transnational criminal organizations, hostile nation-states, and FTOs. As we described in a prior client alert, the memorandum also calls for an “America First,” business-friendly approach to white collar enforcement, which could ultimately lead to fewer or less aggressive prosecutions of U.S. companies. In light of the memorandum’s explicit focus on sanctions evasion as both a criminal and national security concern, we anticipate that DOJ, including not just the Criminal and National Security Divisions in Washington, but also individual U.S. Attorney’s offices around the country, will vigorously pursue financial institutions that facilitate sanctions evasion by processing illicit transactions.

In line with DOJ and OFAC efforts to combat sanctions evasion, U.S. authorities this past year continued to engage in a multi-agency push to both prosecute and sanction parties involved in North Korea’s sustained effort to generate hard currency to fund North Korea’s weapons of mass destruction programs, through the placement of remote information technology (IT) workers across hundreds of U.S. companies. As part of this IT worker scheme, which has been active for several years, a sizeable contingent of North Korean individuals have fraudulently obtained remote employment with U.S.-based companies, leveraging stolen identities of U.S. persons, and relying on the assistance of U.S.-based individuals. While the primary objective of the scheme appears to be to raise currency for the North Korean regime, the scheme—which sees remote IT workers performing routine tasks in corporate roles such as software development—also enables access by these remote workers to potentially sensitive data, including source code and export-controlled data. There have been reports of data exfiltration and extortion in connection with this scheme, in addition to collection of salaries.

In June 2025, DOJ announced nation-wide, coordinated law enforcement actions against the North Korean IT worker scheme, resulting in the indictment of 13 individuals (including two U.S. nationals, who have both pleaded guilty), and the seizure of 29 financial accounts and approximately 200 laptops used to facilitate remote access to U.S. company systems. The next month, in July 2025, an Arizona woman was sentenced to 8.5 years in prison for her role in helping North Korean IT workers obtain jobs at over 300 U.S. companies. And in November 2025, DOJ announced five further IT worker-related guilty pleas and over $15 million in civil forfeiture actions. OFAC complemented DOJ’s efforts on multiple occasions designating non-U.S. parties implicated in the scheme. In light of North Korea’s decades-long isolation from the mainstream global economy, further attempts to penetrate U.S. businesses, along with associated prosecutions and sanctions designations, are likely to persist in the months ahead. Although the U.S. government has so far been treating victim companies as partners in these enforcement efforts, businesses reliant on remote IT workers are on notice of the red flags consistent with the scheme and should ensure appropriate diligence throughout hiring and employment processes to mitigate risk.

U.S. export controls have further cemented their place alongside sanctions as key tools in furthering U.S. national security and foreign policy objectives, particularly as the United States seeks to restrict access to certain advanced technologies by perceived geopolitical competitors like China. Yet, the role of export controls in 2025 has been complicated by political tides that ushered in significant institutional changes at the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security, the agency primarily responsible for administration of U.S. export controls on goods, software, and technology that have both military and civilian uses (commonly known as “dual-use” items).

A number of longtime BIS officials departed the agency, known for its technically complex regulations, which has led to a lull in new rules and a spike in export licensing wait times. At the same time, the second Trump administration has increasingly reached for export controls as a bargaining chip at the diplomatic negotiating table, both with China and with U.S. industry. The result was a year of starts and stops, where landmark new rules were paused or walked back not long after they were announced, creating uncertainty among industry about compliance expectations.

Despite these institutional challenges, export enforcement showed no signs of slowing down. With significant enforcement actions from both BIS and DOJ, the new administration seemed to follow through on Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick’s assurances during his confirmation hearings that aggressive export enforcement would be a priority. As BIS has now received a 23 percent funding increase from Congress for fiscal year 2026, continued robust enforcement is expected, even if the longer-term impact of personnel turnover remains to be seen.

1. AI Diffusion Rule Rescission and Shift in Semiconductor Export Control Strategy

In its closing days, the Biden administration issued the Artificial Intelligence (AI) Diffusion Rule, a sweeping interim final rule to control access to advanced AI capabilities by establishing chokepoints over three key exports: advanced integrated circuits (ICs); compute power; and model weights. On May 13, 2025, two days before the AI Diffusion Rule’s effective date, the Trump administration announced its rescission of the rule, citing concerns that its burdensome regulatory requirements could undermine innovation and that its tiered licensing system could generate adverse diplomatic consequences.

The policy shift is consistent with a broader trend in U.S. export control strategy toward pairing restrictive measures with affirmative efforts to shape global technology ecosystems around U.S. supply chains, standards, and compliance expectations—particularly in strategically significant regions such as the Middle East. China’s continued development of advanced AI models despite extensive U.S. export controls appears to have informed this approach. Against this backdrop, the rescission of the AI Diffusion Rule—together with approvals conditionally permitting additional exports of advanced semiconductors to the United Arab Emirates and a series of AI initiatives involving the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia—reflects an effort to expand the reach of U.S.-aligned AI infrastructure and governance. Consistent with this trend, the White House’s July 2025 AI Action Plan calls for the United States to “meet global demand for AI by exporting its full AI technology stack (hardware, models, software, applications, and standards) to all countries willing to join America’s AI alliance.” The plan was paired with a July 2025 Executive Order promoting the export of the American AI technology stack, which is in turn implemented through the October launch of the American AI Exports Program, though details of this program remain scant at present.

Despite the Trump administration’s stated intent to replace the prior AI Diffusion Rule with a “stronger but simpler” framework, BIS has not yet issued replacement regulations. And although BIS recently loosened restrictions on the export of certain advanced chips to China, the manufacturing equipment used to build them and most AI-capable hardware remain subject to significant licensing constraints. As discussed in a prior client alert, we believe that any replacement framework is likely to retain core elements of the rescinded rule, including differentiated treatment for trusted jurisdictions, some form of validated end-user or equivalent authorization for data centers, enhanced customer diligence and reporting obligations, and controls on certain proprietary AI models. Indeed, many of these elements have been central parts of the Trump administration’s partial lifting of controls on the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and China.

On the same day BIS announced the rescission of the AI Diffusion Rule, the agency issued new guidance underscoring its intent to continue tightening export controls targeting China. In particular, BIS invoked the Export Administration Regulations’ expansive General Prohibition 10 (GP 10) to caution against transactions involving advanced Chinese ICs that meet or exceed the performance thresholds set forth in Export Control Classification Number (ECCN) 3A090. GP 10 generally prohibits dealings in items subject to the EAR where a known violation of the EAR has occurred, is about to occur, or is intended to occur in connection with the item.

According to BIS, due to the application of one or more foreign direct product rules—rules which bring within U.S. export control jurisdiction foreign-made items that incorporate, or are the direct product of, certain software and technology, or components made from U.S. inputs—there is a high likelihood that the design or production of certain advanced Chinese ICs involved violations of the EAR. As a result, BIS warned that dealings in such ICs, including through their purchase or use without authorization, could create enforcement risk. This guidance illustrates how GP 10 can extend export controls beyond export transactions to reach downstream commercial activity, including certain services and financial dealings.

BIS also issued a policy statement aimed at parties seeking to avoid hardware export controls by purchasing remote access to compute capacity, through Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS) or GPU-as-a-Service arrangements, rather than acquiring such hardware directly. The policy statement indicates that a license requirement applies to the export, reexport, or transfer of advanced computing ICs, and commodities containing them, where the exporter has knowledge that they will be used to provide compute power for AI model training for or on behalf of a weapons of mass destruction or military-intelligence end users headquartered or operating in a country subject to a U.S. arms embargo (including China). BIS further indicated that U.S.-person support for such cloud-based activities may also require a license. While the contours of these restrictions have not yet been tested publicly through BIS enforcement actions, nor clarified through further guidance, they raise significant compliance considerations for cloud service providers, data center operators, and other participants in the AI infrastructure ecosystem.

Finally, BIS published accompanying red flags guidance identifying transactional and behavioral indicators of diversion risk and recommended enhanced due diligence measures for exporters of advanced computing ICs.

In the latter half of 2025, BIS revoked validated end-user (VEU) status—an authorization for pre-vetted end users to receive covered items without obtaining an otherwise-required license for each export—of several foreign-owned semiconductor fabrication facilities based in China.

Reports further suggest that, shortly before the revocations took effect around December 31, 2025, the U.S. government approved time-limited export licenses permitting continued exports of certain controlled items to the affected facilities. These developments underscore both BIS’s continued willingness to tighten end-user controls targeting China’s semiconductor sector, and its use of licensing as a mechanism to manage economic and diplomatic consequences. Further, Commerce’s framing of the action as closing a “loophole” harkens back to the America First Trade Policy’s directive to “eliminate loopholes in existing export controls—especially those that enable the transfer of strategic goods, software, services, and technology” to strategic rivals.

Unlike the first Trump administration and the Biden administration, which generally viewed export controls, especially those targeting semiconductors, as specialized national security tools, the second Trump administration has increasingly deployed export controls to gain leverage in broader trade negotiations. In May 2025, BIS reportedly sent letters to three major software companies imposing new license requirements for the export of chip design software to China. These requirements were later removed in July 2025 as part of a negotiated trade deal with Beijing, which Commerce Secretary Lutnick publicly linked to China’s agreement to loosen restrictions on exports of rare earth materials.

Export controls were also used as leverage in the White House’s negotiations with U.S.-headquartered chip manufacturers, which reportedly made economic concessions to the U.S. government to secure the ability to re-establish sales of certain chip lines to China. As detailed in our recent client alert, BIS issued limited relief for these products in January 2026.

Even with the partial resumption of sales of certain U.S.-made advanced chips to China, BIS enforcement actions in 2025 serve as a reminder that controlling access to AI-capable computing power remains a strategic priority for the United States. The Trump administration’s greenlighting of advanced chip sales to China in late 2025 was reported around the same time the U.S. government brought two significant criminal enforcement actions, targeting the illegal export of advanced U.S.-origin chips to China. In November 2025, DOJ announced the arrest and indictment of four individuals who, from September 2023 through November 2025, allegedly transshipped approximately 800 advanced GPUs to China through Malaysia and Thailand without a required export license. In December 2025, DOJ announced that it had successfully dismantled a separate, sophisticated chip-smuggling network exporting advanced GPUs to China and other restricted destinations.

In a year marked by significant policy shifts, one of the most consequential developments out of BIS was its issuance and quick suspension of its so-called “Affiliates Rule.” Issued as an interim rule on September 29, 2025 with immediate effect, the Affiliates Rule briefly extended certain export controls to foreign affiliates that are 50 percent or more owned by one or more entities on the Entity List, Military End-User (MEU) List, or subject to SDN end-user controls under section 744.8 of the EAR. By some measures, the Affiliates Rule brought another 20,000 unlisted Chinese companies onto restricted lists. On November 12, 2025, however, BIS published a final rule suspending the Affiliates Rule for one year, effective through November 9, 2026.

The promulgation and subsequent suspension of the Affiliates Rule is yet another example of the Trump administration’s evolving stance toward China, and its willingness to allow export controls to be included as potential bargaining chips in broader trade negotiations. The Affiliates Rule was intended to address BIS’s longstanding “whack-a-mole” problem, under which listed entities often establish “legally distinct” affiliates to evade U.S. export controls. Unlike OFAC’s restricted party lists, which have long been interpreted to include affiliates under OFAC’s 50 Percent Rule, prior to the BIS Affiliates Rule’s issuance, Commerce’s restricted party lists generally applied only to specifically enumerated entities and not to their subsidiaries or affiliates. Given the concentration of China-based entities on BIS’s restricted party lists, the Affiliates Rule contributed to heightened U.S.–China trade tensions. The rule’s one-year suspension occurred against the backdrop of broader U.S.–China trade negotiations, concluded during the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Summit in South Korea.

The Affiliates Rule represents one of the most far-reaching changes to BIS regulations in years. As detailed in our prior alert, the rule:

- Extends licensing requirements, exceptions, and review policies to any foreign affiliate owned 50 percent or more by one or more listed entities, whether directly or indirectly, individually or in the aggregate. Conceptually similar to OFAC’s 50 Percent Rule, this approach departs from BIS’s traditional list-based framework;

- Imposes the most restrictive license requirements, license exception eligibility, and license review policy applicable to any of the affiliate’s listed owners under the EAR;

- Imposes heightened due diligence obligations for exporters, reexporters, and transferors who have “knowledge,” including “reason to know,” that a foreign counterparty is directly or indirectly owned by a listed entity; and

- Expands end user-based foreign direct product rules to restrict transactions with newly “constructively listed” affiliates.

Importantly, the Affiliates Rule has not been repealed. Absent further regulatory action or broader policy changes, the rule will automatically come back into effect on November 10, 2026. The current suspension should therefore be viewed as temporary relief rather than a permanent resolution; affected industries should use this window to prepare for its reinstatement. Many exporters subject to the EAR had already made significant investments to comply with the rule prior to its suspension and have continued to maintain those compliance measures to avoid being unprepared in the event of a snapback.

BIS continued to prioritize China-related Entity List designations in 2025, adding approximately one hundred entities over the course of the year. Although the overall number of China-related designations was lower than in 2024, the 2025 actions appear to have been more targeted, potentially reflecting BIS’s ability to more finely calibrate Entity List additions in light of the far-reaching implications of the Affiliates Rule. Targeted industries and activities included:

- Advanced chips, quantum, and AI: BIS designated multiple China-based firms for supporting the development of China’s quantum technology sector, warning that such technologies could significantly enhance Chinese military capabilities. In addition, 19 China-based entities, two Singapore-based entities and one Taiwan-based entity were listed for activities related to AI, supercomputing, and high-performance chip development closely tied to Chinese military end users. BIS also designated several Chinese academic and research institutions for their roles in developing large AI models, quantum technologies, and advanced computing chips contributing to China’s military and surveillance capabilities.

- Hypersonic technology: BIS designated 34 Chinese entities for acquiring, or attempting to acquire, U.S.-origin items in support of China’s development of hypersonic weapons and flight technologies.

- Russian diversion: BIS designated at least one Chinese entity for supplying otherwise-prohibited technology to Russian military end users.

BIS also targeted supply chains supporting Iran’s UAV programs. In March and October, BIS added 17 China-based entities to the Entity List for providing U.S.-origin components to Iran’s defense sector, particularly for use in UAV programs operated by Iranian proxies such as the Houthis and Hamas. In addition, BIS designated three PRC addresses associated with a Chinese individual previously designated by OFAC for supporting a sanctioned supplier of the Iranian military.

3. Military, Intelligence, and Security End-Use and End-User Controls

BIS also appears to be continuing its internal review of proposed military end-user rules issued in 2024 (the Proposed MEU Rules). If adopted, the Proposed MEU Rules would significantly expand the scope of existing military end-user and end-use restrictions to cover all items subject to the EAR, including lesser-controlled EAR99 items, and to apply to all countries specified in Country Group D:5 (which includes countries subject to U.S. arms embargoes) as well as Macau.

The Proposed MEU Rules would also prohibit U.S. persons from providing “support” to military end users, intelligence end users, and foreign-security end users as defined or redefined in the proposed rules. If implemented, these provisions would materially alter the treatment of services under the EAR. In particular, cloud-based services—such as IaaS, platform as a service (PaaS), and software as a service (SaaS)—which have traditionally fallen outside the scope of the EAR, could become subject to licensing requirements when provided to covered end users.

Notable developments in U.S. export controls were not limited to the Commerce Department. Whereas BIS is responsible for overseeing and administering the EAR, controls over the movement of defense articles remain within the purview of the U.S. Department of State, which has responsibility for the International Traffic in Arms Regulations. Through updates to the ITAR, in 2025 the State Department office that administers the regulations, the Directorate of Defense Trade Controls (DDTC), adjusted the items subject to its jurisdiction, implemented U.S. foreign policy goals through both the easing and tightening of license requirements, and took procedural steps to streamline the export licensing process across the U.S. government.

DDTC continued to expand coverage of emerging and automated warfare technologies under the United States Munitions List (USML) in 2025, while further offloading civilian munitions and commercially oriented technologies to the EAR. In particular, the State Department issued a final rule, effective September 15, 2025, revising and expanding USML Categories III–V, VII–XIV, XVIII, and XIX–XXI.

This rule represents one of the more significant expansions of the USML in recent years. Among other changes, it added the F-47 (a planned sixth-generation fighter jet) and several other aircraft platforms, certain chemical agents and precursors, uncrewed and untethered vessels, and a broad range of related components and parts to the USML. At the same time, DDTC sought to preserve licensing flexibility for systems with legitimate scientific or commercial applications. For example, the rule excluded from ITAR jurisdiction or provided license availability for certain Global Navigation Satellite System anti-jamming and anti-spoofing systems and Airborne Collision Avoidance Systems antennas. DDTC also introduced a license exemption for qualifying Unmanned Underwater Vehicles designed for commercial uses, such as seabed exploration and the installation and maintenance of undersea infrastructure.

Separately, the State Department updated the licensing policy in ITAR Section 126.1—country-based restrictions that stem from United Nations actions, terrorism-related designations, and arms embargoes—to reflect recent UN Security Council resolutions. This rule revised the licensing policy applicable to the Democratic Republic of Congo, Haiti, Libya, Somalia, the Central African Republic, Sudan, and South Sudan—tightening restrictions in certain cases while easing them in others, in response to the latest developments in conflicts throughout these jurisdictions.

On December 30, 2025, DDTC further amended the ITAR to streamline defense trade and government-to-government cooperation under the Australia–United Kingdom–United States (AUKUS) partnership. The final rule eliminates the requirement to identify Australian or UK governmental authorities as Authorized Users when relying on the AUKUS-specific license exemption under ITAR Section 126.7.

The rule also introduces a new exemption permitting certain reexports, retransfers, and temporary imports among authorized parties in support of Australian, UK, or U.S. armed forces operating outside of those three jurisdictions. These changes are intended to reduce administrative friction and facilitate closer operational and industrial collaboration among AUKUS partners.

In 2025, the United States continued to use the suspension and revocation of arms embargoes as foreign policy tools. On November 7, 2025, DDTC permanently and unconditionally lifted the arms embargo on Cambodia. The embargo had been imposed in 2021 amid concerns regarding rising Chinese influence within the Cambodian military, and its removal marked a notable shift in U.S. policy toward Phnom Penh.

This development contrasts with the more cautious approach taken with respect to Cyprus. In recognition of Cyprus’s continued efforts to combat money laundering and restrict Russian naval access to its ports, DDTC suspended the arms embargo on Cyprus for the fourth consecutive year, rather than lifting it outright.

In November 2025, the Department of State launched USXPORTS.gov, a unified portal for navigating export license applications submitted to both BIS and DDTC. The platform was developed pursuant to Executive Order 14268, which directs those two agencies to reform foreign defense sales to improve speed and accountability.

USXPORTS.gov replaces the two former tracking systems used for DDTC and BIS license applications and provides centralized tracking and visibility across the defense export licensing lifecycle. The portal represents a step toward greater transparency and coordination between the Commerce and State Departments in administering U.S. export control regimes.

In contrast to efforts to facilitate licensing for foreign military sales, at the outset of his term, President Trump directed BIS to undertake a comprehensive review of the U.S. export control system and imposed a regulatory freeze on a range of Biden-era rules. As part of this review, BIS suspended certain license requirements applicable to advanced computing chips and temporarily paused the acceptance or processing of new license applications, resulting in a significant licensing backlog.

This review process led to several notable adjustments to prior licensing practices. Most prominently, BIS rescinded the AI Diffusion Rule (as discussed above) and revoked a firearms-related licensing rule issued during the Biden administration. The review also coincided with the August 2025 enactment of the Maintaining American Superiority by Improving Export Control Transparency Act, which requires Commerce to submit annual reports to Congress detailing license applications that involve certain restricted end users located in certain jurisdictions (including China, Russia, and other arms-embargoed countries).

Although these developments signal a reassessment of the scope and administration of U.S. export controls, it remains unclear how this sweeping review will ultimately affect BIS’s licensing policies and practices. Notably, these changes are occurring against the backdrop of broader agency turnover and loss of institutional memory, driving 2025 processing times for BIS license applications to their highest level in more than 30 years. In particular, questions remain regarding whether licensing timelines, review standards, and approval rates will stabilize or continue to fluctuate as BIS balances national security objectives, economic competitiveness concerns, and foreign policy considerations. As we discussed recently, although these changes have created uncertainty and presented exporters with day-to-day challenges, this inflection point at BIS also brings potential opportunities for industry to advocate for new approaches.

Despite personnel changes and a shifting regulatory environment, BIS maintained a robust export enforcement posture in 2025, as the agency entered into eight settlement agreements with businesses and affiliated individuals, resulting in civil penalties totaling approximately $104 million. Enforcement actions spanned a range of industries, including freight forwarding, aviation, and semiconductor technology, and continued to focus heavily on exports involving China and Russia.

BIS also brought multiple enforcement actions involving unauthorized exports of low-sensitivity EAR99 items, underscoring that export control compliance risks are not limited to highly controlled technologies. These cases reflect BIS’s continued emphasis on strict adherence to the EAR’s end-use, end-user, and destination-based restrictions, regardless of an item’s classification. In addition to civil enforcement actions, BIS continued to deny export privileges to individuals and entities found to have violated U.S. export control laws, or where such denials were deemed necessary to prevent imminent violations.

BIS’s $95 million settlement with California-based Cadence Design Systems (Cadence) was the largest penalty of 2025. Acting through its Chinese subsidiary, Cadence sent EAR-controlled Electronic Design Automation technology for semiconductors to an Entity-Listed Chinese university, without the requisite BIS authorization. The BIS settlement was significantly larger than normal and may represent a warning shot for other companies in the semiconductor industry. Additionally, the penalty amount likely reflects BIS’s findings that employees had reason to know the recipient of the controlled technology was a listed entity and that prohibited sales spanned over five years and totaled over $45 million.

The BIS settlement was announced alongside a coordinated resolution with DOJ, as Cadence also became the first company to agree to a corporate guilty plea for a national security offense during the second Trump administration. The more than $140 million in combined criminal and administrative penalties are among the highest ever in an export enforcement case. The multi-agency resolution reflects continued close interagency cooperation in enforcing export controls. Even as other areas of corporate enforcement may see deprioritization, national security-related enforcement, particularly involving sensitive technologies and exports to China and other countries of concern, continues to accelerate.

The Cadence matter stands in contrast to two other DOJ resolutions this year, which emphasize the potential benefits of voluntary self-disclosure, cooperation, and remediation under the National Security Division’s (NSD) enforcement policies:

- In April 2025, pursuant to its Enforcement Policy for Business Organizations, NSD declined to prosecute Universities Space Research Association, a nonprofit research organization and NASA contractor, after the company promptly disclosed misconduct by a former employee who had willfully provided EAR99 flight control software to an Entity List party in China. NSD cited the organization’s timely and voluntary disclosure, exceptional cooperation, and meaningful remediation as key factors supporting the declination.

- A second declination, announced in June 2025, involved White Deer Management’s (White Deer) acquisition of Unicat Catalyst Technologies (Unicat). Following the acquisition, White Deer discovered chemical catalyst sales by Unicat to customers in Iran, Syria, Venezuela, and Cuba in violation of U.S. export control and sanctions laws. NSD declined to prosecute White Deer under its Voluntary Self-Disclosures in Connection with Acquisitions Policy (its first-ever declination under this policy), citing White Deer’s prompt disclosure, proactive cooperation, and remediation within a year of discovering the misconduct. Notably, NSD reached this outcome despite aggravating factors at Unicat, including senior management involvement. Unicat itself entered into a non-prosecution agreement with DOJ, receiving credit for White Deer’s actions, while Unicat’s former CEO pleaded guilty.

Looking ahead to 2026, BIS is expected to continue expanding enforcement efforts to advance U.S. national security objectives, with a particular focus on exports to U.S. adversaries—especially China—and on sensitive technologies such as AI, quantum computing, hypersonics, and semiconductors. Signaling its concerns regarding these risks, Congress has increased BIS’s budget by 23 percent, or approximately $44 million, in 2026, with the majority of that funding earmarked to support additional enforcement personnel. DOJ is similarly expected to continue prioritizing the criminal enforcement of export control and other national security-related offenses, with U.S. Attorney’s Offices and DOJ’s Criminal Division supplementing NSD’s efforts.

F. Other BIS Regulatory Regimes

Separate from U.S. export controls administration, other offices within BIS sought to innovate in their enforcement of long-standing prohibitions, and to address emerging threats through the implementation of new regimes.

BIS’s Office of Antiboycott Compliance (OAC) continued to publish updates to its Boycott Requester List in 2025. First announced in March 2024 to facilitate compliance with U.S. antiboycott requirements, the Boycott Requester List serves as a public repository of entities that have made reportable boycott-related requests—including requests to comply with the Arab League boycott of Israel—that have been submitted to BIS. The list is intended to provide U.S. persons, as well as foreign persons subject to the reporting requirements of Part 760 of the EAR, with notice that identified counterparties may present an elevated risk of making reportable boycott-related requests.

Importantly, inclusion on the Boycott Requester List does not prohibit U.S. persons from engaging in transactions with listed entities. Rather, the list functions as a compliance aid, highlighting the need for heightened vigilance and internal controls when dealing with identified parties. Entities may be removed from the list by submitting an attestation to OAC confirming that they have eliminated boycott-related language from purchase orders, contracts, letters of credit, and other commercial communications with U.S. persons and their foreign subsidiaries.

OAC has indicated that the Boycott Requester List is updated quarterly. BIS’s press release in April 2025 followed the practice of the Biden administration, identifying the number of additions to and removals from the list during the prior quarter. BIS stated that, since the introduction of the list, more than 65 entities have agreed to discontinue the inclusion of boycott-related terms in their transactions with U.S. persons, underscoring the list’s role as both a compliance tool and an enforcement-adjacent mechanism incentivizing voluntary remediation. Although the current version of the Boycott Requester List—which includes 181 parties as of this writing—indicates that OAC made further additions across 2025, BIS appears to have ceased its public releases regarding the quarterly updates.

BIS brought one antiboycott enforcement action in 2025, assessing a $44,750 civil penalty against a Florida-based defense contractor. The company voluntarily disclosed and agreed to settle charges relating to three alleged violations arising from a 2019 transaction, including furnishing information about business relationships with a blacklisted party, and failing to report receipt of two boycott-related requests as part of the same transaction (specifically, a certification stating that “no labor, capital, parts, or raw materials of Israeli origin have been used” in connection with the goods, and stating that certain parties were not included “on the Israeli Boycott Blacklist”).

As in other corners of BIS, OAC experienced significant leadership changes in 2025, with the departure of longstanding office leader Cathleen Ryan. Given the small size of BIS’s antiboycott team and the high level of engagement Director Ryan had in its activities, this change may have a significant impact on how the agency reviews boycott reports, approaches disclosures and enforcement, and on its willingness to provide industry guidance via its hotline, which was often staffed directly by Director Ryan.

BIS’s Office of Information and Communications Technology and Services (OICTS) continued its efforts to address national security concerns in ICTS supply chains. Most notably, in 2025, OICTS issued a final rule prohibiting certain transactions involving “connected vehicles” and related components with a sufficient nexus to China or Russia (the Connected Vehicles Regulations). With some of these prohibitions impacting Model Year 2027 vehicles, 2026 will be a critical year for importers and manufacturers involved in the connected vehicles supply chain to review and potentially enhance their policies and procedures to ensure ongoing compliance.

OICTS also issued an advance notice of proposed rulemaking (ANPRM) soliciting comments on efforts to restrict the use of Chinese- and Russian-origin unmanned aerial systems and related components, though additional regulatory action by OICTS has not yet occurred. Any future efforts will likely complement the U.S. Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) December 2025 addition of most foreign-made uncrewed aircraft systems and related critical components to the FCC’s Covered List—which prohibits such items from receiving FCC equipment authorization and thus effectively restricts their entry into, or sale or marketing within, the United States. In the coming year, we expect OICTS to continue its rulemaking efforts in the drone space and potentially in other sectors, including IaaS transactions. However, recent leadership flux, including the January 2026 departure of inaugural OICTS Director Elizabeth Cannon, may result in new regulatory priorities.

a) Connected Vehicles Regulations

As discussed in detail in our previous client alert, the Connected Vehicles Regulations prohibit the import and sale in the United States of certain “connected vehicles” and key components, including Vehicle Connectivity Systems (VCS) and Automated Driving Systems (ADS) linked to Chinese-affiliated or Russian-affiliated companies. Broad prohibitions on the sale of “connected vehicles” by manufacturers with a sufficient nexus to China or Russia, even if manufactured in the United States, apply to Model Year 2027 vehicles. Although these regulations currently only apply to passenger vehicles under 10,001 pounds, a similar rule for commercial vehicles is expected. Additional software-related prohibitions will also take effect for Model Year 2027 vehicles, and hardware-related prohibitions will take effect for Model Year 2030 vehicles, or on January 1, 2029 for units without a model year.