February 5, 2018

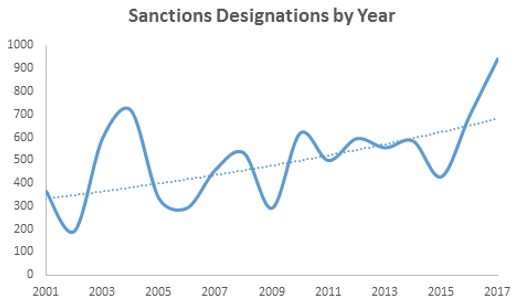

A year ago this week, we assessed that the newly-minted Trump administration could follow through on the President’s campaign promises and alter several sanctions programs administered by the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (“OFAC”). The U.S. Congress, we surmised, could respond by codifying and expanding existing regulations. After a year of historic growth in the use of sanctions—and one in which sanctions played a greater role in both foreign and domestic policy in the United States—we stand by that assessment. The Trump administration continued a nearly two-decade bipartisan trend of increasing reliance on sanctions. Across the full range of sanctions programs, nearly 1,000 entities and individuals were added to the Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons (the “SDN” or “black”) list. (see below). This represented a nearly 30 percent increase over the number added during President Obama’s last year in office, and a nearly three-fold increase over the number added during President Obama’s first year in office.

Source: Graph compiled from OFAC data.

The Trump administration’s Secretary of the Treasury, Steven Mnuchin, has had an unprecedented level of involvement in OFAC’s recent actions. In prior administrations, the Treasury Secretary’s involvement in sanctions policy was intermittent and rare, leaving the day-to-day work and announcements of new sanctions to the director of OFAC or the Under Secretary for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence. To the best of our knowledge, there has never been a Treasury Secretary so clearly enamored with the sanctions tool—an assessment supported by Mnuchin’s own September 2017 claim that he spends half of his time on national security and sanctions issues.[1]

While the increasing use of sanctions is noteworthy and brings to mind concerns raised by observers about an “overuse” of sanctions, neither the administration nor Congress appears likely to cease their reliance on the tool as a “go to” instrument of coercion. The past year saw increased sanctions pressure on Iran, Syria, Russia, and North Korea as well as a roll back of the Cuban sanctions relief provided under President Obama. Congress responded, codifying and strengthening existing sanctions measures against Russia, Iran and North Korea by passing the unprecedented “Countering America’s Adversaries through Sanctions Act” (“CAATSA”).[2] New sanctions on Venezuela were imposed and old sanctions on Sudan were removed.

Even as the Trump administration sought to separate itself from the Obama team, many of the new sanctions imposed—such as those against Venezuela—appear to borrow explicitly from the Obama administration’s playbook. Moreover, several core features of Obama’s sanctions policy remain broadly untouched—at least for now. Key among them is the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (“JCPOA”), which President Trump described during the presidential campaign as “the worst deal ever negotiated.[3] Despite uncertainty over its future, the JCPOA remains intact.[4]

There were also some surprises. On December 20, 2017, President Trump issued an unusually broad executive order to implement the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act, a 2016 law that authorized sanctions for those responsible for human rights abuses and significant government corruption.[5] The order was celebrated by the human rights and anti-corruption non-government communities,[6] and added more than four dozen individuals and entities from various countries—including Burma, China, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Gambia, Guatemala, Russia, and South Sudan, and even from core U.S. allies like Israel—to OFAC’s SDN List.[7]

We would be remiss to omit reference to the pivotal role that sanctions played in the deteriorating diplomatic relationship between the United States and Russia, as well as many of the political controversies that dominated the headlines in 2017. In 2012, the United States Congress passed an aggressive law intended to punish Russian officials responsible for the death of Sergei Magnitsky, a Russian accountant who was imprisoned after exposing a tax fraud scheme allegedly involving Russian government officials and who died under suspicious circumstances while in custody.[8] Specifically, the Sergei Magnitsky Rule of Law Accountability Act (“2012 Magnitsky Act”)—passed unanimously by the U.S. Congress in December 2012—sought to block certain Russian government officials and businessmen from entering the United States, froze their assets held by U.S. banks, and banned future use of the U.S. banking system.[9] Subsequent efforts to remove the 2012 Magnitsky Act sanctions serve as critical background for many of the allegations surrounding Russia’s purported efforts to interfere in the 2016 U.S. election.[10] There are presently 49 individuals sanctioned under authority granted by the 2012 Magnitsky Act.[11]

While events of the past year will give historians much fodder to assess the long-term geopolitical and even domestic political impact of economic sanctions, our purpose here is more limited: a recap of the continuing evolution of sanctions in 2017.

I. Major U.S. Program Developments

A. Russia

Title II of CAATSA, the “Countering Russian Influence in Europe and Eurasia Act of 2017” (“CRIEEA”), strengthened OFAC’s sectoral and secondary sanctions targeting the Russian Federation in several significant and unprecedented ways. CAATSA codified and amended the Russia sectoral sanctions that had been implemented during the Obama administration.[12] By adopting the Obama-era executive orders as statutory law, Congress sought to ensure that only congressional action can weaken or eliminate these sanctions.[13] CAATSA also authorized or mandated secondary sanctions with respect to certain activities, such as conducting malicious cyber-attacks or providing support to Russian energy export projects. Moreover, the statute, for the first time in any sanctions law, explicitly limited the President’s ability to license (exempt) transactions from sanctions prohibitions if the licensing “significantly alters United States’ foreign policy with regard to the Russian Federation.”[14]

In brief, CAATSA expanded the Obama administration’s sanctions targeting certain sectors of the Russian economy by reducing the maximum maturity period for new debt that U.S. persons can provide to designated Russian financial institutions from 30 to 14 days, and to designated Russian energy companies from 90 to 60 days.[15] CAATSA also expanded the Obama administration’s prohibition on the provision of goods, support, or technology to designated Russian entities relating to the exploration or production for deepwater, Arctic offshore, or shale projects that have the potential to produce oil in the Russian Federation.[16] CAATSA removed the limitation that such projects be located in Russia, instead targeting “new” oil projects worldwide in which a designated Russian person has a “controlling interest or a substantial non-controlling” ownership interest.[17]

OFAC’s Russia Sanctions 101Whenever there is a change or expansion of U.S. sanctions policy, we find it useful to revisit some of the basic tenets of U.S. sanctions. As a matter of first principles, U.S. sanctions have two principal means of targeting an activity: (1) sanctioning persons for engaging in those activities ; and/or (2) designating the activity as per se sanctionable.

|

CAATSA also sought to strengthen secondary sanctions targeting those non-U.S. persons who engage in activities ranging from undermining cybersecurity,[18] to investing in Russian crude oil projects,[19] evading sanctions and abusing human rights.[20] In expanding these measures, Congress dramatically increased OFAC’s workload for the final quarter of 2017, as CAATSA created numerous interpretative issues, reporting and designation requirements that consumed the remainder of the year. We analyze these measures in greater detail, as well as OFAC’s guidance and implementing regulations in Trump Administration Implements Congressionally Mandated Russia Sanctions – Significant Presidential Discretion Remains (November 21, 2017).

Most recently, CAATSA required the imposition of secondary sanctions on any person the President determines to be engaging in “a significant transaction with a person that is part, or operates for or on behalf of, the defense or intelligence sectors of the Government Russia.”[21] Those sanctions were due to be imposed within 180 days of the passage of CAATSA—by January 29, 2018. On January 29, State Department representatives provided classified briefings to Congressional leaders to explain their decision not to impose any such sanctions under CAATSA.[22] Though the briefings were classified, the State Department revealed that the Trump administration felt that CAATSA was already having a deterrent effect which removed any immediate need to impose sanctions.[23] Some Members of Congress expressed disapproval of the administration’s lack of action and accused the White House of failing to implement the law.[24] But the statutory language is nuanced, and the administration’s FAQs released in October 2017 indicated that—in line with similar language passed in 2010 with respect to sanctions on Iran—it would be taking a flexible approach to assessing violations under this provision.[25] While it is unknown what was said in the classified briefings, we are aware of numerous outreach missions that administration representatives have undertaken in order to deter foreign governments and corporations from engaging in such transactions. The publicized plans of certain governments to purchase substantial Russian munitions in 2018—such as Turkey’s proposal to procure S-400 surface-to-air missiles from Russia[26]—will test both the power of the law’s deterrence and potentially Congress’s patience.

CAATSA also required the Treasury Department to publish—also by January 29—a report identifying “the most significant senior foreign political figures and oligarchs in the Russian Federation.”[27] Just before midnight on January 29, the Treasury Department issued its report, publicly naming 114 senior Russian political figures and 96 oligarchs.[28] The inter-agency team charged with drafting the report used objective standards in drafting these lists—senior political figures included members of the Russian Presidential administration, members of the Russian Cabinet and senior executives at Russian state-owned enterprises. For the oligarch list, OFAC included Russians with a net worth of U.S. $1 billion or more. All of these classifications appear to be based on information that is generally available in the public sphere. Although the report apparently includes a lengthy classified annex, it was not immediately clear what kind of information was included in that material.

Notably, there is no legal impact of appearing in this report. The Treasury Department noted in numerous places that this report “is not a sanctions list,” and “the inclusion of individuals or entities in any portion of the report does not impose sanctions on those individuals or entities.”[29] That there are no sanctions implications to such a listing was also a unique CAATSA innovation—never before has OFAC been charged with compiling and publishing a “name and shame” list with no concomitant sanctions. As a consequence, many financial institutions and private corporations on the outside of government have been uncertain how to handle transactions with counterparties who now appear on this list. To date, it appears that the breadth and objective nature of the list has substantially dulled the impact—a fact that many critics of the administration have noted. Even in Russia the impact has been surprisingly muted. It is noteworthy that even as President Putin’s senior representatives claimed that the list was the United States’ attempt to influence Russia’s upcoming presidential contest, Putin quickly announced that he would not be authorizing any retaliatory measures.

Aside from the considerable efforts required to implement CAATSA, OFAC added 38 more individuals and entities involved in the Ukraine conflict to the SDN List in June 2017.[30] The sanctioned parties included Ukrainian separatists and their supporters; entities operating in and connected to the Russian annexation of Crimea; entities owned or controlled by, or which have provided support to, persons operating in the Russian arms or materiel sector; and Russian Government officials.[31]

B. Iran

As expected, the Trump administration has taken a harsh posture toward Iran, using existing sanctions programs to designate numerous individuals and entities—including the head of Iran’s judiciary[32]—and threatening to abandon the JCPOA. Though specific licensing requests are confidential, our experience and understanding is that OFAC licensing of Iran-related transactions —even those in line with the JCPOA—has slowed considerably.

On October 13, 2017, President Trump refused to certify, under the authority granted to him by the Iran Nuclear Agreement Review Act (“INARA”) of 2015, that the sanctions relief under the JCPOA is “appropriate and proportionate” to the measures taken by Iran with respect to its nuclear program.[33] As we wrote this past October, President Trump’s refusal to make the certification kicked off a sixty-day period during which Congress could have enacted Iran-related sanctions legislation on an expedited basis. Congress allowed the sixty-days to pass without taking action.

But Congress was not inactive on the Iran sanctions front. Although CAATSA’s Russia-related portions captured most of the headlines, Title I of CAATSA, the “Countering Iran’s Destabilizing Activities Act of 2017” (“CIDA”), imposed significant sanctions against Iran. CIDA targeted Iran’s ballistic missile program, the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (“IRGC”), Iranian human rights abuses, and weapons transfers benefitting Iran. CAATSA also codified the designations of persons pursuant to two executive orders and purports to limit the President’s ability to remove those persons from the SDN list.[34] We described the measures targeting Iran at length in our alerts, Congress Seeks to Force (and Tie) President’s Hand on Sanctions Through Passage of Significant New Law Codifying and Expanding U.S. Sanctions on Russia, North Korea, and Iran (July 28, 2017), and A Blockbuster Week in U.S. Sanctions (June 19, 2017).

On January 12, 2018, President Trump announced that he was giving the deal another 120 days to be “fixed.” Although the administration has not made clear the full nature of its concerns with the JCPOA, it has noted that the deal’s silence on Iran’s ballistic missile development and the existence of certain “sunset provisions” (after which any remaining sanctions would be permanently lifted) are high on the list of shortcomings. The announcement of this deadline (which expires in May 2018) set off a feverish set of negotiations with core European partners (the UK, Germany and France) and with Congress to develop new measures that will satisfy the President. As we have noted, the JCPOA is not a Senate-ratified treaty but rather an Executive Agreement. As such the President has significant flexibility to remain in or to exit the Agreement. Given the President’s apparent willingness to unilaterally remove the United States from agreements that the Obama team negotiated (such as the Paris Climate Accord) we assess that even though it remains unclear how the situation will evolve, the President’s threat is unlikely to be perceived as a mere a negotiating strategy.

C. North Korea

The relationship between the United States and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (“DPRK” or “North Korea”) deteriorated rapidly in 2017, resulting in new sanctions that target non-U.S. persons and foreign financial institutions for doing business with the Pyongyang regime. Unlike many other aspects of the Trump administration’s foreign policy, the DPRK efforts have been decidedly multilateral—several United Nations Security Council resolutions against DPRK have been passed since Trump took office. These resolutions are described in greater detail in the European Union section of this Update.

Although successive U.S. administrations had tightened sanctions on North Korea—declaring a “national emergency” under the IEEPA in 2008, blocking hundreds of North Korean individuals and entities, banning imports in 2011 and exports in 2016[35]—the perception of the threat and the potential for a U.S. military response escalated rapidly under the Trump administration. In the early days of 2018, tensions between the United States and Pyongyang seem to have reached a fever pitch—with leaders on both sides claiming to have their finger on the nuclear launch button.[36]

North Korea’s characteristic bellicosity was apparent in its efforts to ramp up its domestic missile program in 2017. The DPRK fired more than 20 missiles from at least 16 different tests between February and December.[37] In July 2017—as the U.S. Congress was drafting expansive legislation to impose sanctions on Iran and Russia—North Korea tested two intercontinental ballistic missiles, claiming they could reach “anywhere in the world.”[38] In response, Congress added a new section targeting North Korea to the draft CAATSA, titled “Korean Interdiction and Modernization of Sanctions Act” (“KIMSA”).[39] CAATSA expanded sanctions that had previously been set forth by Congress in the North Korea Sanctions and Policy Enhancement Act of 2016, enabling the President to impose sanctions on foreign individuals and entities that historically provided an economic lifeline to the Pyonyang regime. CAATSA strengthened sanctions aimed at North Korean economic activities and required the Secretary of State to submit a determination as to whether North Korea meets the criteria for designation as a state sponsor of terrorism. The Trump administration ultimately added North Korea to the state sponsors of terrorism list on November 20, 2017.[40]

On September 20, 2017, the Trump administration issued Executive Order 13810, imposing additional sanctions on North Korea.[41] This order borrowed from the Obama administration’s sanctions playbook by imposing sanctions on specific sectors and threatening to cut off access to the U.S. banking system for non-U.S. persons involved in North Korean trade. In the words of Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, the order effectively put foreign banks “on notice that, going forward, they can choose to do business with the United States, or with North Korea, but not both.”[42]

This was not the first attempt to restrict North Korea’s access to the global banking community. In 2016, OFAC’s ban on the export of goods, technology, and services to North Korea included a prohibition on financial services.[43] Also in 2016, the Treasury Department classified North Korea as a “jurisdiction of primary money laundering concern” under Section 311 of the USA Patriot Act, 31 U.S.C. § 5318A, effectively prohibiting the use of correspondent accounts on behalf of North Korean financial institutions and requiring that U.S. financial institutions implement additional due diligence with regard to entities linked to North Korea.[44] However, the threat of the potential application of correspondent and payable-through banking restrictions on non-North Korean financial institutions in Executive Order 13810 was expected to have a more significant impact on North Korea than these other measures.

Executive Order 13810 also laid the groundwork for the imposition of sectoral sanctions by granting OFAC the authority to designate those involved in a long list of North Korean economic sectors: construction, energy, financial services, fishing, information technology, manufacturing, medical, mining, textiles, or transportation industries, as well as those who own, control, or operate any port in North Korea, and North Korean persons, including those engaged in commercial activity that generates revenue for the Government of North Korea or the Workers’ Party of Korea. Unlike with the Russian sectoral sanctions, however, a designation under Executive Order 13810 results in the blocking of all property and interests in property. Executive Order 13810 is described at length in our alert, In Latest Salvo, the Trump Administration Pressures Non-U.S. Companies and Persons to Cut Financial and Business Ties with North Korea.

Given that several members of the Trump administration have noted that the North Korea threat—and the effort to denuclearize the Korean peninsula—is the President’s “number one” foreign policy priority, we assess that more sanctions are likely in the near term. The Department of Justice (“DOJ”) has also been active in this arena—launching investigations, issuing grand jury subpoenas and acting against assets believed to be linked to North Korea. In August 2017, the DOJ resolved an $11 million money laundering and asset forfeiture matter for actions alleged associated with North Korean financial facilitators.[45]

Notably, in the last few weeks we have seen a warming relationship between North and South Korea. Whether this signifies a permanent improvement in diplomatic relations on the Korean peninsula, or a brief respite ahead of the Winter Olympics, remains to be seen. Either way, multinational corporations would be wise to observe any daylight that develops between Seoul and Washington sanctions policies with respect to the North Korea. A divergence in the approach to North Korean sanctions between these major players could lead to significant challenges.

D. Cuba

As we noted last year, the final year of the Obama administration brought about a series of important changes to the Cuba sanctions regime. This summer, President Trump announced that he was “canceling” President Obama’s “one-side deal”[46] with Havana. In November, the Departments of the Treasury, Commerce, and State began to implement significant changes to the United States’ Cuba sanctions regime. Though the previous administration’s actions were not entirely removed—and have not been as of this writing—the Trump administration did rollback several of the Obama administration’s changes to United States sanctions policy with respect to Cuba.

As noted, on June 16, 2017, President Trump announced that his administration would reimpose some of the sanctions on Cuba that were relaxed under President Obama. According to a fact sheet that the White House issued at the time, the new Cuba policy aims to keep the Grupo de Administración Empresarial (“GAESA”), a conglomerate run by the Cuban military, from benefiting from the opening in U.S.-Cuba relations.[47] The fact sheet further elaborated that the new policy purports to enhance existing travel restrictions to “better enforce the statutory ban” on U.S. tourism to Cuba, including limiting travel for non-academic educational purposes to group travel and prohibiting individual travel permitted by the Obama administration.[48] At the time, President Trump directed the Departments of the Treasury and Commerce to begin the process of issuing new regulations within 30 days of the announcement.[49] We described the policy change in our alert, A Blockbuster Week in U.S. Sanctions (June 19, 2017).

On November 8, 2017, OFAC, the Commerce Department’s Bureau of Industry and Security (“BIS”), and the State Department released amendments to the Cuban Assets Control Regulations (“CACR”) and Export Administration regulations (“EAR”), implementing the changes.[50] Additionally, while certain transactions with Cuban parties by U.S. persons remain permitted, the CACR now prohibit transacting with entities listed on the State Department’s new “Cuba Restricted List” (or the “List”), which was released simultaneously and consists of Cuban entities that the administration considers to be “under the control of, or act for or on behalf of, the Cuban military, intelligence, or security services personnel.”[51]

Notably, these provisions, when viewed together with the increased restrictions, muddy the already difficult-to-navigate regulatory waters. The new OFAC and BIS amendments cover three main areas:

- The OFAC amendments now prohibit U.S. persons and entities from engaging in direct financial transactions with entities listed on the Cuba Restricted List, while the BIS amendments state that BIS will generally deny license applications for the export of items for use by entities on the list.[52] The List includes over 175 entities and sub-entities that operate in a variety of economic sectors, notably, over 80 of which are hotels.[53] The focus on hotels directly impacts the Obama-era sanctions relief that had led to an increase in U.S. visits to the island, as even permitted visitors will now have a difficult time finding appropriate accommodation. These changes have already seen a retrenchment and reduction in U.S. visitors.

- The OFAC amendments restrict people-to-people travel that had previously been authorized, requiring, among other things, that nonacademic educational travel be conducted under “the auspices of an organization that is a person subject to U.S. jurisdiction and that sponsors such exchanges to promote people-to-people contact” and that such travelers are accompanied by a representative of that organization and participate in full-time schedule of activities.[54]

- BIS has simplified the Support for the Cuban People License Exception to the Cuba Embargo, now allowing for the export of all EAR99 items (and those controlled only for anti-terrorism reasons on the Commerce Control List ) to Cuba, provided the intended end user is in the Cuban private sector.[55]

Three months after the issuance of these amendments, it is still unclear whether a complete pivot with respect to U.S. policy towards Cuba is in the making. Undoubtedly, there are signals that a full reversal is possible: in addition to President Trump’s rhetoric and the recent amendments, 2017 witnessed stories concerning attacks on U.S. (and other) diplomats in Havana and the expulsion of various Cuban diplomats from the United States. At the very least, the Trump administration’s policy has served to chill the considerable interest that had developed in investments in Cuba.

E. Venezuela

Throughout 2017, Venezuela’s President Nicolás Maduro and his supporters moved to consolidate their power. In March 2017, Venezuela’s Tribunal Supremo de Justicia ruled that it was taking over all powers of the Asemblea Nacional.[56] Although the court later revised its ruling, months of protests ensued, and Maduro supporters elected a purported replacement legislature, the Asemblea Constituyente, in an election that was widely boycotted by Maduro’s opposition.[57] Amidst this political upheaval, Venezuela’s economy—which is largely dependent on the state-owned oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (“PdVSA”)—has been in sharp decline. In response to the Maduro governments efforts to undermine their political opposition, the United States slowly increased and expanded its economic sanctions against Venezuela, focusing on blocking the property and interests of key figures in the Maduro government and on financial sanctions that make it more difficult for the Maduro government and PdVSA to raise new money.

OFAC’s first steps against individual persons associated with the Maduro government took place in March 2015 blocking designations, and OFAC followed these with additional designations in May and November 2017. OFAC’s initial March 2015 designations were made pursuant to EO 13692[58] and targeted a short list of seven officials in response to their role in the erosion of human rights guarantees, persecution of political opponents, curtailment of press freedoms, use of violence and human rights violations and abuses in response to antigovernment protests, and arbitrary arrest and detention of antigovernment protestors, and significant public corruption. These officials occupied positions in Venezuela’s intelligence, security, prosecutorial, and defense services.

The May and November 2017 designations targeted both former and current officials. They included President Maduro (for engineering the election of the Asemblea Constituyente), eight members of Tribunal Supremo de Justicia (for efforts to obstruct Asemblea Nacional)[59] and members of the Consejo Nacional Electoral who interfered in regional elections in October 2015. Others designated include the second VP of the Asemblea Constituyente, its former second VP and now Ambassador to Italy, the current Cultural Minister, and Minister of Urban Agriculture.[60] Two government officials were also designated under authority of the Foreign Narcotics Kingpin Designation Act (Kingpin Act) for playing significant roles in narcotics trafficking.

On August 24, 2017, President Trump issued an executive order imposing sanctions targeting transactions involving debt and equity of the Venezuelan government, including PdVSA. These restrictions borrowed from the Russian sanctions from 2014 and were based on a similar set of policy constraints—namely, even though it might be possible for U.S. sanctions to enact devastating harm on economic targets in Venezuela, the collateral consequences of doing so (to the United States and its allies) would be potentially too serious. Consequently a lesser set of sanctions—a “grey list”—was required.

As such, the following activities are now prohibited without OFAC authorization. As under other sanctions programs, the prohibitions apply not only to the entities specifically targeted in the executive order (i.e., the Government of Venezuela and PdVSA), but also to any entity that is at least 50% owned or controlled by the targeted entities (for example, subsidiaries of PdVSA or entities owned or controlled by the Government of Venezuela).[61]

In brief, the executive order prohibits U.S. persons from transactions involving new debt of PdVSA with a maturity of greater than 90 days, or new debt of the Government of Venezuela (other than PdVSA) with a maturity of greater than 30 days. U.S. persons are also prohibited from transacting in new equity of the Government of Venezuela, including PdVSA. The term “equity,” as described in OFAC’s FAQs, “includes stocks, share issuances, depositary receipts, or any other evidence of title or ownership.” This prohibition covers only equity “directly or indirectly” issued by the Government of Venezuela—including PdVSA—after the effective date of the sanctions, but, as described below, transactions involving equity issued by third parties may also be prohibited, if the Government of Venezuela is the seller. This limitation on purely secondary market sales of debt is new and was not implemented in the Russia program.

The executive order also prohibits U.S. persons from engaging in any transactions relating to Venezuelan government (or PdVSA) bonds, even if issued prior to the effective date of the sanctions, with the exception of those covered by the general license described below. OFAC explains this provision (and others in the executive order) as an effort to “prevent U.S. persons from contributing to the Government of Venezuela’s corrupt and shortsighted financing schemes,” including the sale of bonds and other securities “for much less than they are worth at the expense of the Venezuelan people and using proceeds from these sales to enrich supporters of the regime.”

The executive order also prohibits the involvement of U.S. persons in transactions relating to dividend payments to the Government of Venezuela from entities owned or controlled by the Government of Venezuela. This provision restricts the flow of dividends from subsidiaries—including CITGO—up to PdVSA and the Venezuelan government. This has proven a challenge for many companies active in Venezuela: the nationalization efforts under the prior Chavez regime converted the operations of many foreign firms into joint ventures majority held by PdVSA or the Government of Venezuela (the “empresa mixtas”). Finally, U.S. persons are prohibited from purchasing any securities, including those issued by non-sanctioned third parties, directly or indirectly from the Government of Venezuela, except for new debt with maturities of less than 90 days (for PdVSA) or 30 days (for all other portions of the Venezuelan government).

In connection with its financial sanctions, OFAC has issued four general licenses. General License 1 provided for a wind down period of 30 days—until September 24, 2017—to carry out transactions that are “ordinarily incident and necessary to wind down contracts or other agreements that were in effect prior to August 25, 2017.” The wind-down period did not apply to the prohibitions relating to dividends and distributions of profits, and persons engaging in such wind-down transactions were required to file a detailed report with OFAC. General License 2 authorizes transactions involving the new debt or new equity issued by, or securities sold by, CITGO Holding, Inc. or its subsidiaries, provided that no other Government of Venezuela entity is involved in the transaction. This very significant general license effectively carves CITGO out of the new sanctions, provided that U.S. persons are careful not to permit any other involvement by PdVSA or the Government of Venezuela in the transaction. General License 3 exempts certain bonds, listed in an annex, from the prohibition on transactions involving Venezuelan bonds. Several bonds issued by PdVSA are listed in the annex. General License 3 also exempts bonds issued by U.S. persons (e.g., CITGO) prior to the issuance of the executive order. General License 4 authorizes certain transactions relating to new debt involving agricultural commodities (including food), medicine, or medical devices.

In late 2017 Venezuela bonds fell into technical default as some of its payments were delayed. Though the Government has appeared to continue juggling accounts to remain out of a more formalized default situation—which could have serious consequences as bonds could become due automatically and immediately—the sanctions have made traditional renegotiation of debt challenging. Maduro has appointed two individuals, Vice President Tareck El Aissami and Economy Minister Simon Zerpa, to lead his government’s efforts in any renegotiation; both of those men are on the SDN List making it uncomfortable for any financial institution to enter into any negotiations with them.[62]

An additional complexity in the Venezuelan situation came about with Maduro’s announcement that his government was issuing a new “cyber currency” to thwart any impact of restrictions on the U.S. dollar that came about due to sanctions. In response OFAC issued its first FAQ discussing cyber currencies— though perhaps not broadly applicable to the world’s more mainstream cyber currencies, it is noteworthy that OFAC held that its jurisdiction explicitly extended to the use of any new Venezuelan cyber currencies and that U.S. persons could face sanctions consequences if they undertook dealings in the new currency.[63]

F. Sudan

In January 2017, the Obama administration revoked most of the Sudanese Sanctions Regulations (“SSR”) by general license, subject to a six-month review period.[64] After a brief extension of the review period, the Trump administration finalized the revocation of the SSR effective October 12, 2017. Historically, the SSR had included a trade embargo, a prohibition on the export or re-export of U.S. goods, technology and services, a prohibition on transactions relating to Sudan’s petroleum or petrochemical industries, and a freeze on the assets of the Sudanese government. Under the separate Darfur Sanctions Regulations (“DSR”), the United States blocked property belonging to those connected to the conflict in Darfur. The DSR remain in place, as do the designations of numerous Sudanese persons.

II. U.S. Enforcement

A. Selected OFAC Enforcement Actions

2017 was a busy year for OFAC enforcement actions. OFAC assessed over $119 million in collective civil penalties in 16 enforcement actions; however, four cases represent roughly 96% of the issued penalties. Notably, one enforcement action against a Chinese entity, Zhongxing Telecommunications Equipment Corporation, which resulted in the highest penalty for the year and OFAC’s largest penalty ever imposed on a non-financial institution (over $100 million), may have foreshadowed a growing enforcement trend for 2018—cracking down on Chinese companies working with jurisdictions under comprehensive U.S. sanctions (such as Iran, North Korea, Cuba, Syria and the Crimea Region of Ukraine).

Zhongxing Telecommunications Equipment Corporation[65]

On March 7, 2017, Zhongxing Telecommunications Equipment Corporation and its subsidiaries and affiliates, (collectively, “ZTE”), agreed to settle its potential civil liability for 251 apparent violations of the Iranian Transactions and Sanctions Regulations (“ITSR”) for $100,871,266. ZTE is a telecommunications corporation established in the People’s Republic of China.

According to the settlement documents, from January 2010 to March 2016, ZTE developed and implemented a company-wide plan that used third-party companies to conceal ZTE’s illegal business activities with Iran. ZTE’s highest-level management had specific knowledge of the legal risks of engaging in such activities prior to signing contracts with Iranian customers and supplying U.S.-origin goods to Iran. Under these contracts, ZTE committed to the procurement and delivery of U.S.-origin goods to Iran. Some of these delivered goods included those controlled for anti-terrorism, national security, regional stability, and encryption item purposes. ZTE was also contractually obligated to and, did in fact, enhance the law enforcement surveillance capabilities and features of Iran’s telecommunications facilities and infrastructure.

OFAC determined that ZTE willfully and recklessly demonstrated a disregard for U.S. sanctions requirements and that the 251 apparent violations constituted an egregious case. In making its determination, OFAC considered the following facts and circumstances: (1) various executives and senior executives knew or had reason to know of the conduct that led to the apparent violations and engaged in a long-term pattern of conduct designed to hide and purposefully obfuscate its conduct; (2) the conduct was undertaken pursuant to directives and business processes that were illegitimate in nature and specifically designed and implemented to facilitate the violative behavior; (3) ZTE caused significant harm to the integrity of the ITSR and its associated policy objectives; and (4) ZTE is a sophisticated and experienced telecommunications company that has global operations and routinely deals in goods, services, and technology subject to U.S. laws.

ExxonMobil Corp.[66]

On July 20, 2017, ExxonMobil Corp. and its U.S. subsidiaries (collectively, “ExxonMobil”) were penalized in the amount of $2,000,000 for violating the Ukraine-Related Sanctions Regulations by engaging in business with Igor Sechin, the President of Rosneft OAO who has been identified on the SDN List.

ExxonMobil and Mr. Sechin signed legal documents related to oil and gas projects in Russia when OFAC had already designated Mr. Sechin as an SDN approximately one month prior. ExxonMobil explained that it interpreted the related White House press statements to be establishing a distinction between Mr. Sechin’s “professional” versus “personal” capacity, citing a news article that quoted a Treasury Department representative that a U.S. person would not be prohibited from participating in a meeting of Rosneft’s board of directors. OFAC considered ExxonMobil’s arguments and determined that the penalty accurately reflects OFAC’s consideration of the underlying facts and circumstances. Specifically, OFAC considered the following: (1) ExxonMobil failed to consider warning signs associated with Mr. Sechin; (2) ExxonMobil’s senior executives knew of Mr. Sechin’s status as an SDN; and ExxonMobil is a sophisticated and experienced oil and gas company that routinely deals in business activities subject to U.S. economic sanctions.

This penalty—and in particular the seeming removal of any distinction between personal and professional capacities—was met with surprise and concern in the OFAC bar. ExxonMobil is currently challenging OFAC’s decision in federal court.

CSE Global Limited and CSE TransTel Pte. Ltd.[67]

On July 27, 2017, CSE TransTel Pte. Ltd. (“TransTel”), a wholly owned subsidiary of CSE Global Limited (“CSE Global”), agreed to pay $12,027,066 to settle its potential civil liability for 104 apparent violations of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (“IEEPA”) and the ITSR. Both TransTel and CSE Global are located in Singapore and offer telecommunications and technological services around the world. CSE Global appeared to expand OFAC jurisdiction—at least explicitly—to cases in which non-U.S. parties “cause” U.S. entities to violate their sanctions obligations.

From August 25, 2010 through November 5, 2011, TransTel entered into contracts with multiple Iranian companies to deliver and install telecommunications equipment for several energy projects in Iran or its territorial waters. To fulfill its contracts, TransTel hired and engaged a number of third-party vendors, including several Iranian companies, to provide goods and services on its behalf. In April 2012, the Singaporean bank that maintains TransTel and CSE Global’s accounts sent them a letter regarding sanctions warnings, to which TransTel and CSE Global responded that they would not route any transactions related to Iran through the bank. From June 2012 to March 2013, TransTel then used the bank’s services for its Iranian business activities by initiating wire transfers destined to multiple third-party vendors that supplied goods and services for its energy projects in Iran.

OFAC determined these apparent violations to be an egregious case, and considered the following facts and circumstances in its decision: (1) TransTel willfully and recklessly caused apparent violations of U.S. economic sanctions by engaging in, and systematically obfuscating, conduct it knew to be prohibited; (2) TransTel’s senior management played an active role in the wrongful conduct; (3) TransTel’s actions conveyed significant economic benefit to Iran and persons on OFAC’s SDN List by processing dozens of transactions through the U.S. financial system that totaled $11,111,812 and benefited Iran’s oil, gas, and power industries; and (4) TransTel is a commercially sophisticated company that engages in business in multiple countries. OFAC considered the following to be mitigating factors: (1) TransTel has not received a penalty notice or cautionary letter from OFAC in the five years preceding the violations; (2) TransTel and CSE Global have undertaken remedial steps to ensure compliance with U.S. sanctions programs; and (3) TransTel and CSE Global provided substantial cooperation during the course of OFAC’s investigation.

DENTSPLY SIRONA Inc.[68]

On December 6, 2017, DENTSPLY SIRONA INC. (“DSI”), a Delaware corporation, agreed to pay $1,220,400 to settle its potential civil liability for 37 apparent violations of the ITSR. Specifically, two of DSI’s subsidiaries exported 37 shipments of dental equipment and supplies from the United States to distributors in third countries, with actual or constructive knowledge that the goods were destined for Iran.

OFAC determined that the apparent violations constituted a non-egregious case and considered the following facts and circumstances: (1) DSI’s two subsidiaries acted willfully by exporting U.S.-origin dental products to third country distributors with knowledge or reason to know that the exports were ultimately destined for Iran; (2) personnel from these subsidiaries concealed the fact that the goods were destined for Iran, and in multiple cases continued to conduct business with these distributors after receiving confirmation that the distributors had re-exported DII products to Iran; (3) several supervisory personnel had actual knowledge of the conduct and appear to have deliberately concealed their awareness from DSI; (4) DSI has not received a penalty notice in the five years preceding the violations; (5) the harm to ITSR objectives was limited because the exports were likely eligible for specific license; and (6) DSI took remedial steps, including a voluntary expansion of the review to include a company-wide inquiry.

Habib Bank Limited[69]

In 2017, the New York Department of Financial Services (“DFS”) continued in its pursuit to enforce sanctions compliance for major banks. In furtherance of this goal, DFS’s new regulation, Part 504, took effect on January 1, 2017, which sets forth the requirements for all DFS-licensed institutions and their use of sanctions screening programs. On September 7, 2017, DFS issued a consent order against Habib Bank Limited (“Habib”) and its New York branch, imposing a $225 million penalty for persistent BSA/AML and sanctions compliance failures. Habib is currently Pakistan’s largest bank. Pursuant to the order, Habib agreed that it failed to maintain an effective AML and OFAC compliance program; failed to maintain true and accurate books and records; failed to operate in an unsafe and unsound manner; and violated provisions of a prior written agreement and consent order. Prior to issuing the consent order, DFS had issued a “Notice of Hearing and Statement of Charges,” seeking to impose a nearly $630 million civil penalty against the Pakistani bank. Habib will surrender its license to operate its New York Branch until it fulfills the conditions outlined in DFS’s separate Surrender Order. As part of the conditions it must fulfill, Habib must complete an expanded transactional “lookback” to be conducted by an independent consultant. As of this writing Habib has decided to cease operations in New York.

III. European Union

In 2017, the European Union (the “EU”) stayed the course from 2016. The key sanctions programs on Russia/Ukraine/Crimea and Iran were prolonged while further sanctions regulations were adopted, namely with respect to Mali and Venezuela. Additional actions were also seen in the fast-moving DPRK sanctions and, in a noticeable development, an enhancement in sanctions enforcement actions across Europe.

A. Legislative developments

Mali

On September 28, 2017, the European Union Council Decision (CFSP) 2017/1775 implemented UN Resolution 2374 (2017), which imposes travel bans and assets freezes on persons who are engaged in activities that threaten Mali’s peace, security or stability. Interestingly, the imposition of this regime was requested by the Malian Government, due to repeated ceasefire violations by militias in the north of the country. Affected persons will be determined by a new Security Council committee, which has been set up to implement and monitor the operation of this new regime, and will be assisted by a panel of five experts appointed for an initial 13-month period. As yet no one has been designated under the Mali sanctions.

Venezuela

Finally following the U.S. lead on Venezuela sanctions, on November 13, 2017 the EU Council decided to impose an arms embargo on Venezuela, and also to introduce a legal framework for travel bans and asset freezes against those involved in human rights violations and non-respect for democracy or the rule of law.[70] Subsequently on, January 22, 2018 an initial list of seven individuals was published who were subject to these sanctions.

Though these measures are not yet as severe as U.S. measures on Venezuela—and the Council stated that the sanctions can be reversed if Venezuela makes progress on these issues— the Council was also explicit in its warning that the sanctions may be expanded if the situation exacerbates.[71]

North Korea

As noted above with respect to U.S. measures, the events on the Korean Peninsula in 2017 also gave rise to significant new EU measures against DPRK. The UN has been very active on DPRK issues and the EU has both been supporting such measures and expending significant efforts to implement these measures across the bloc’s 28 members. On June 2, the UN Security Council designated a further four entities and 14 officials subject to travel bans and asset freezes, including Cho Il U, believed to be the Director of North Korea’s overseas espionage operations and foreign intelligence collection.

In early August, the UN Security Council unanimously passed Resolution 2371 (2017), which introduced fresh sanctions against North Korea, including: (i) a full ban on coal, iron and iron ore (which, at $1 billion, is estimated to represent about a third of North Korea’s export economy); (ii) the addition of lead and lead ore to the banned commodities subject to sectoral sanctions; (iii) a ban on seafood exports from North Korea; and (iv) the expansion of financial sanctions by prohibiting new or expanded joint ventures and cooperative commercial entities with the DPRK.

Demonstrating the significant developments seen to North Korean sanctions in 2017, in August the EU consolidated its existing North Korean sanctions into Council Regulation 2017/1509, a move deemed necessary in view of the numerous amendments that had been made to the previous Council Regulation 329/2007. It also issued an updated decision, Council Decision (CFSP) 2017/1512, amending Council Decision (CFSP) 2016/849, to reflect these changes.

The UN Security Council duly imposed Resolution 2375 (2017) on September 11, 2017, which includes: (i) a ban on textile exports (North Korea’s second-biggest export at over $700m per year); (ii) limits on imports of crude oil and oil products to the amount imported by the exporting country in the preceding year; (iii) a prohibition against all joint ventures or cooperative entities or the expansion of existing joint ventures with North Korean entities or individuals; and (iv) a ban on new visas for North Korean overseas workers. These measures were watered down from the original restrictions called for by the United States, so as to ensure that Russia and China would not veto the proposals. The United States had initially sought a total prohibition on exports of oil into North Korea, stricter restrictions on North Koreans working in foreign countries, enforced inspections of ships suspected of carrying UN sanctioned cargo, and a complete asset freeze against Kim Jong-Un.

In November, the EU further imposed additional restrictions via Council Regulation (EU) 2017/2062, which: (i) broadened the ban on investment of EU funds in or with North Korea to all economic sectors; (ii) reduced the permissible amount of personnel remittances to North Korea from €15,000 to €5,000; and (iii) at the Council’s invitation to review the existing list of luxury goods subject to import/export bans, published a new list, which covers everything from caviar, cigars and horses to artwork, musical instruments and vehicles.

Finally, rounding off the year, the UN imposed Resolution 2397 (2017) on December 22, which inter alia: (i) strengthens the measures regarding the supply, sale or transfer to North Korea of all refined petroleum products, including diesel and kerosene, and reduced to 500 million barrels per 12-month period the permitted maximum aggregate of refined petroleum product exports to North Korea; (ii) limits the supply, sale or transfer of crude oil by Member States to the DPRK to 4 million barrels or 525,000 tons per 12-month period; (iii) expands sectoral sanctions by introducing a ban on North Korean exports of food and agricultural products, machinery, electrical equipment, earth and stone, wood and vessels, as well as a prohibition against the sale of North Korean fishing rights; (iv) introduces a ban on the supply, sale or transfer to North Korea of all industrial machinery, transportation vehicles, iron, steel and other metals; (v) strengthens the ban on providing work authorizations for North Korean nationals by requiring Member States to repatriate all income-earning North Koreans and all North Korean government safety oversight attachés monitoring North Korean workers abroad by 22 December 2019; and (vi) strengthens maritime measures by requiring Member States to seize, inspect and freeze any vessel in their ports and territorial waters for involvement in banned activities.

As North Korea’s missile and nuclear programs show no signs of being halted, we expect that the international community will continue to expand the restrictive measures imposed against North Korea in the coming year. Indeed already in 2018, the EU has designated a further 17 North Korean individuals through Regulation 2018/87. Though it is unlikely that the EU will get ahead of the U.S. or the UN the bloc has been cohesive among the 28 in the necessity of applying pressure on the Pyongyang regime.

Russian Federation

On December 21, 2017, the EU once again extended the economic sanctions adopted in 2014 in response to Moscow’s annexation of the Crimea and Sevastopol and the continued and deliberate destabilization of Ukraine. The economic sanctions are currently extended until July 31, 2018. Also, the listing of numerous Russian entities and individuals as targets of financial sanctions including measures such as asset freezes and the prohibition to provide funds or economic resources remained in place and was further extended.

These measures also continue to include a number of trade restrictions and limitations on the access to the EU capital markets for major Russian majority state-owned financial institutions and major Russian energy companies.

In particular, in accord with U.S. measures, EU Sanctions Regulations prohibits the sale, supply, transfer or export of products to any person in Russia for oil and natural gas exploration and production in waters deeper than 150 meters, in the offshore area north of the Arctic Circle and for projects to have the potential to produce oil from resources located in shale formations by way of hydraulic fracturing. The provision of associated services (such as drilling or well testing) is also prohibited, whilst authorization must be sought for the provision technical assistance, brokering services and financing relating to the above.

The trade of dual-use goods and technology is also restricted to the extent that it is prohibited to sell dual-use goods and technology for the Russian military users and prior authorization must be sought for the sale of such good and technology for all non-military users in Russia.

The provision of goods and technology listed in the Common Military List is prohibited, while the supply of certain fuels used for rockets and space technology is subject to prior authorization.

Note that there are exceptions for certain contracts concluded before 2014, ancillary contracts necessary for the execution of contracts concluded before 2014, and when the provision of services is necessary to prevent an event likely to significantly impact human health.

In addition, assets for certain natural and legal persons have been frozen, and member states may only authorize the release of certain frozen funds or economic resources to satisfy the persons and their dependents’ basic needs, for payment of reasonable professional fees, for payment for contracts concluded before the sanction and for claims secured to an arbitral decision rendered prior to the sanction.

Statements made by the EU and the responsible German authority clearly indicated the importance of EU sanctions and their implementation.

Unlike with the DPRK sanctions, the continuation of Russian sanctions continues to threaten dissent among some of the EU’s members. Time will tell if this dissenting bloc will eventually coalesce around a shared position and formally prevent the EU from continuing any measures against Moscow.

Crimea and Sevastopol

As the EU still does not recognize the annexation of Crimea and Sevastopol by Russia, it imposes sanctions against these territories as Ukrainian territory.[72]

The measures, which include an import ban on goods from Crimea and Sevastopol, restrictions on trade and investment relating to a wide variety of economic sectors and infrastructure projects, as well as an export ban for certain goods and technologies relating to the transport, telecommunication, energy and mineral resources sectors have been extended until June 23, 2018.[73] These restrictions are nearly identical to those in place in the United States.

Iran

| Divergence between U.S. and EU Sanctions: A Hypothetical Any divergence between U.S. and EU sanctions has the potential to cause significant compliance hurdles for multinational companies. To take a hypothetical example: a German company is selling a product to Iran, and the product and the Iranian counterparty are not subject to any EU sanctions, yet they are subject to U.S. sanctions. The contract is signed, the product is ready for shipping and the Iranian counterparty has set aside the necessary funds. To now conclude the transaction, the German company cannot rely on a U.S. dollar transaction, as the U.S. clearing bank is likely to reject the transaction or freeze the funds. The U.S. dollar transaction or any other U.S. related business dealings could create a U.S. nexus leaving the transaction and eventually the German company in breach of U.S. sanctions. Even if the German company had decided to finance the transaction in EURO, business practice since Implementation Day has shown that (because as most banks rely on the access to the U.S. financial system) only a very limited number of international banks are willing to take the risk of accommodating such a transaction, fearing retaliation from U.S. regulators. |

As set out in our 2016 Year-End Sanctions Update, the European Council lifted all nuclear related economic and financial EU sanctions against Iran on January 16, 2016 pursuant to Iran’s compliance with the JCPOA. Nonetheless, some restrictions remain in force.

The remaining measures in force include those related to violations of human rights adopted in 2011, and comprise an asset freeze and visa bans for individuals and entities responsible for grave human rights violations and a ban on exports to Iran of equipment which might be used for internal repression and of equipment for monitoring telecommunications, as well as nuclear and ballistic missile technology. These measures where recently extended until April 13, 2018.

EU Rosneft Judgement

One European judicial outcome in 2017 is especially noteworthy. In March 2017, the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU) established its jurisdiction to rule on matters of the EU’s common foreign and security policy, which is an area of fierce contention between Brussels and national governments seeking to maintain sovereignty.[74]

The case, which was referred by the UK High Court concerned Russian oil company Rosneft’s questioning of the validity of EU sanctions against Russia regarding a restricted access to the EU’s capital markets and on the provision of financial assistance related to the supply of key equipment for the Russian oil sector.

While the CJEU in a first step confirmed the validity of the EU Russia sanctions, it also addressed important questions regarding the scope of the imposed sanctions.[75]

In interpreting “financial assistance” under article 4(3)(b) of EU Regulation 833/2014 relating to the need for prior authorization if related to the sale, supply, transfer or export of specified equipment for the Russian oil sector, the UK government and the European Commission both interpreted the term broadly to include payment services.[76]

However, the CJEU rejected this view and stated that financial assistance in this case “does not include the processing of a payment, as such, by a bank or other financial institution.”[77]

This was in line with arguments made by Rosneft and the intervening German government that the mere processing of a third-party payment is different from providing active and substantive support and must be comparable to loans, credits or export credit insurance.[78]

This interpretation threatens to further distance U.S. and EU sanctions. This more limited approach is in opposition to U.S. views in which prohibitions on dealings with certain actors almost always include the use of financial institutions under U.S. jurisdiction to provide services to sanctioned parties. It remains to be seen how European banks—eager to both engage in legal business but remain compliant with U.S. regulations so as to maintain their own U.S. correspondent banks—will adjust to this more flexible approach.

IV. United Kingdom

Legislative developments

Policing and Crime Act 2017 and accompanying guidance

Part 8 of the Policing and Crime Act 2017, which came into force on April 1, 2017, strengthened the UK’s sanctions enforcement by increasing the maximum custodial sentence for violating sanctions rules from two to seven years. Additionally, it expanded the list of offences amenable to a deferred prosecution agreement (“DPA”), giving the National Crime Agency and Office of Financial Sanctions Implementation (“OFSI”) more scope to offer DPAs—which can still only be entered into by the Serious Fraud Office and the Crown Prosecution Service—and impose Serious Organized Crime Prevention Orders.

Importantly, it also gives OFSI new powers—this still new agency is slowly building up its authorities and has established a strong track record in its brief stint. The Policing and Crime Act gives the agency the power to impose, as an alternative to criminal prosecution and by reference to the civil standard of proof, monetary penalties for infringements of EU/UK sanctions. OFSI can impose penalties of either £1 million or 50% of the value of the breach, whichever is greater. The lower evidential burden to impose the new civil penalties means that OFSI need only be satisfied on the balance of probabilities that a person (legal or natural) acted in breach of sanctions and knew or had reasonable cause to suspect they were in breach.

The Act also addresses the delay between the United Nations Security Council adopting a financial sanctions resolution and the EU adopting an implementing regulation, which can take over a month. OFSI can adopt temporary regulations to give immediate effect to the UN’s resolutions, as if the designated person were included in the EU’s consolidated list. OFSI put this power into practice in June of this year by adding a militia leader, Hissene Abdoulaye, to its consolidated list of Central African Republican sanctions targets, before the EU had done so.

Businesses relying on a version of the EU’s consolidated list prepared by the European Union, or by a member state other than the United Kingdom, may miss fast-track listings done by the UK in this manner. The UK has also enacted the Policing and Crime Act (Financial Sanctions) (Overseas Territories) Order 2017 to extend these short-term fast-track listings to its offshore financial centers of Cayman, British Virgin Islands and Turks and Caicos.

In a number of interviews this year, OFSI head Rena Lalgie has given further indications of how the body will enforce sanctions compliance. According to Ms. Lalgie, “voluntary disclosure will be an important part of determining the level of any penalties that might be imposed.” OFSI has already said that in its Guidance hat companies that voluntarily come forward will see reductions in fines of up to 50% in “serious” cases and 30% in the “most serious” cases. This is a very similar process to the mitigation provided by OFAC to entities engaging in voluntary disclosure.

Ms. Lalgie also made the following noteworthy comments:

“preventing and stopping non-compliance and ensuring compliance improves in the future.” The agency has used its information powers numerous times to “require companies which haven’t complied to tell [OFSI] how they intend to improve their systems and controls in future.” Any continuing sanctions non-compliance could lead to criminal prosecution, with fines “fill[ing] the gap between prevention and criminal prosecution“.

The most important actions a company can take to avoid violating sanctions rules are to “know [its] customers and promote active awareness among relevant staff of high-risk areas“. Ms. Lalgie believes that a company also ought to know what sanctions are in place in the countries in which it does business and have appropriate, up-to-date procedures that are regularly monitored and understood by staff.

In April 2017, and after a public consultation, OFSI published its final Guidance on the new financial sanctions framework providing detailed guidelines relating to the imposition of the new civil monetary penalties. For further information about the consultation, please see our 2016 Year-End United Kingdom White Collar Crime Alert.

The final OFSI Guidance on monetary penalties was also published in April 2017. It provides a detailed overview of OFSI’s approach to investigating potential breaches, as well as the penalty process and procedures for review and appeal. Of note are the following key points from the guidance:

Penalties can be imposed on natural or legal persons, meaning that separate penalties could be imposed on a legal entity and the officers who run it, if the officer consented to or connived in the breach, or the breach was attributable to the officer’s negligence;

OFSI will regularly publish details of all monetary penalties imposed, including by reference to the name of the person or company in breach, and a summary of the case; and

Under sections 147(3)-(6) of the Policing and Crime Act 2017, decisions to impose a penalty can be reviewed by a government minister and then by appeal to the Upper Tribunal.

In OFSI’s “penalty matrix,” factors which may escalate the level of penalty imposed include the direct provision of funds or resources to a designated person, the circumvention of sanctions, and the actual or expected knowledge of sanctions and compliance systems of the person or business in breach.

Voluntary and materially complete disclosure to OFSI is a mitigating factor that may reduce the level of penalty imposed by up to 50%.

The European Union Financial Sanctions (Amendment of Information Provisions) Regulations 2017

On August 8 2017, the European Union Financial Sanctions (Amendment of Information Provisions) Regulations 2017 (the “IPR 2017”) came into force. Before the IPR 2017, financial services firms had a positive reporting obligation to notify HM Treasury of any known or suspected breach of financial sanctions, and to notify any known assets of those subject to financial sanctions. Failure to notify constituted a criminal offence. The IPR 2017 extends this reporting regime to:

- auditors;

- casinos;

- dealers in precious metals or stones;

- estate agents;

- external accountants;

- independent legal professionals;

- tax advisers; and

- trust or company service providers.

OFSI has claimed in its Guidance (at 5.1.1) that all companies and individuals have a positive reporting obligation, but this is based on wording in the relevant EU regulations not implemented into English law. As such, the IPR 2017 represents a significant expansion of the scope of the financial sanctions reporting obligations in the UK. Moreover, this extension of the reporting obligation regime is specific to the UK—there is no EU equivalent. It should be noted that trade sanctions are on the whole excluded from this reporting regime, with the focus mostly on those included in the Consolidated List or the separate Ukraine List.

As set out in the Explanatory Memorandum to the Regulations, this development occurred without a public consultation, impact assessment, or parliamentary scrutiny. The failings of the system as currently enacted are best seen by way of a comparison with the money laundering reporting obligations.

In the field of AML:

- the maker of a bona fide suspicious activity report is protected by statute from liability for any loss or damage flowing from the SAR;

- there is a defense to any breach if the party has followed its regulator’s guidance;

- there is a defense of “reasonable excuse” for failing to make a SAR;

- there is an architecture for reporting, first within an organization and then for an MLRO who has personal criminal liability if they fail to report; and

- there is an exception to the obligation to make a SAR for lawyers and accountants, auditors or tax advisers, if the information came from the client—the so-called “privileged circumstances” exception.

None of the certainty that comes with a clear reporting hierarchy is found in the IPR 2017, and none of these protections are present either. Most notably this may have an unintended chilling effect on companies seeking legal assistance in the conduct of an internal investigation. As they stand the IPR 2017 would require a company’s lawyers to report to OFSI any suspected breach of sanctions, thus robbing the client of the possibility of gaining any credit by self-reporting. Given that OFSI’s own guidance stresses the benefits of self-reporting, the IPR 2017 only serve to undermine this policy objective.

It remains to be seen whether the government will revise the IPR 2017 to take account of these failings.

Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Bill 2017

On October 18, 2017 a new Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Bill was introduced in the House of Lords, which aims to provide a legislative framework for the imposition and enforcement of sanctions after Brexit. Currently much of the UK Government’s authority to impose and enforce sanctions flow from the European Communities Act 1972. The proposed bill would give the Government authority to impose and implement sanctions by way of secondary legislation to comply with its obligations under the United Nations Charter and to support its foreign policy and national security goals.

The European Union (Withdrawal) Bill 2017-19 (the “Bill”) which will give effect to Brexit, will freeze the current sanctions regimes and underlying designations on the date of the UK’s exit from the EU. The sanctions regime in place would quickly become out of date, and absent new legislation the UK would be unable to amend or lift the existing sanctions. The Sanctions and Money Laundering Bill seeks to provide the mechanism to resolve this issue.

The proposed legislation has been through two readings before the House of Lords and is currently at the Committee Stage with the Report Stage scheduled for 15 and 17 January.

Part I of the Bill as originally introduced provided the power to impose sanctions, giving an appropriate Minister, defined as the Secretary of State or the Treasury, the power to make “sanctions regulations” for a variety of purposes including:

- compliance with a UN obligation;

- compliance with another international obligation;

- to further the prevention of terrorism in the UK or elsewhere;

- in the interests of national security;

- in the interests of international peace and security; or

- to further a foreign policy objective of the UK government.

In the process of going through the House of Lords further bases for imposing sanctions have been added to the current draft of the Bill. These are:

- promote the resolution of armed conflicts or the protection of civilians in conflict zones;

- promote compliance with international humanitarian and human rights law;

- contribute to multilateral efforts to prevents the spread and use of weapons and materials of mass destruction; and

- promote respect for human rights, democracy, the rule of law and good governance.

The absence of “misappropriation” as a basis for sanctions is notable, when that is the basis for the current EU sanctions against Egypt and Tunisia and some of those against Ukraine. Another absence is an express reference to cyber-related sanctions. As discussed in our 2017 Mid-Year United Kingdom White Collar Crime Update earlier in 2017 the EU proposed sanctions as one of a panoply of responses to organized cyber-attacks. In the case of human trafficking, as mentioned further below, there have been a number of recent proposals to impose such sanctions. It is possible that some of the broad rubrics such as “protection of civilians in conflict zones” or “human rights law” or “international peace and security” will be extended to cover such sanctions.

“Sanctions regulations” are defined as regulations which impose financial, immigration, trade, aircraft, or shipping sanctions, and expanded upon in clauses 2 to 6 of the Bill. In its comments on the Bill the House of Lords’ Constitution Committee has raised concerns in relation to the breadth of powers afforded to Ministers under the sanctions provisions, including in particular the power to create new forms of sanctions. The Bill is currently the subject of significant debate and it is not yet clear what final form it will take.

The sanctions authorized by the Bill take a variety of forms. Financial sanctions can be imposed by way of asset freezes, and by the placement of restrictions on the provision of financial services, funds, or economic resources in relation to designated persons, persons connected with a prescribed country, or persons meeting a particular description. A person who is the subject of a travel ban may be refused leave to enter or to remain in the UK. Trade sanctions can prevent activities relating to target countries or to target specific sectors within those countries. Aircraft and shipping sanctions can have a variety of impacts, including preventing particular craft from entering the UK’s airspace or waters.

Designated persons can include individuals, corporations, and organizations and can be identified by name or by description. The Bill enables Ministers to set out in regulations how designation powers are to be exercised.

The Bill also includes provision for Ministers to create exceptions to any prohibition or requirement imposed by the regulations, or to issue licenses for prohibitions imposed by the regulations not to apply.

Clause 16 is worthy of mention for, as explained in the accompanying Explanatory Notes, it provides a mechanism for a yet-further expansion of the obligatory reporting regime to all individuals and companies. Whether this provision survives parliamentary scrutiny, and the requirement to protect the right to a fair trial, will remain to be seen.

Chapter 2 sets out the Bill’s provisions on revocation, variation and review of designations of persons under the Bill. The Bill provides that a designation may be varied or revoked by the Minister who made it at any time, and that at any time a designated person may request that the Minister vary or revoke the designation. However, after such a request, no further request may be made unless it relies on new grounds or raises a significant matter which has not previously been considered by the Minister. The Bill also requires periodic review of designations by the appropriate Minister every three years. Where a designated person has been identified by a UN Security Council Resolution, they may ask the Secretary of State to use his or her best endeavors to have their name removed from the UN list. These provisions have attracted criticism, as they would appear to detract from the existing procedural safeguards available in relation to EU sanctions, which include an entitlement to challenge before the Courts. Similarly, the existing EU regime allows for review of designations every six to twelve months.

Although the Bill adopts certain definitions from EU Sanctions measures, it also provides that new sanctions regulations may make provision as to the meaning of other concepts. This may give rise to a divergence in the interpretation of sanctions legislation between the UK and the EU, which could increase uncertainty and the burden of those charged with compliance with multiple sanctions regimes.

Criminal Finances Act 2017—”Magnitsky Sanctions”

The CFA amended POCA to include a “Magnitsky amendment.” This expands the definition of “unlawful conduct” for the purposes of civil recovery orders under Part 5 of POCA to include human rights abuses and applies to those who profited from or materially assisted in the abuses. The amendment is modelled on the US Magnitsky Act. By regulations made on January 20, 2018, this portion of the CFA will come into force on January 31, 2018.

V. United Kingdom and European Union Enforcement

The year 2017 was a remarkable one for sanctions enforcement across the EU. Whether the level of enforcement seen in 2017 will become the new normal, or will soon be revealed as an aberration remains to be seen. What we know is that it would be difficult to point to any other year in recent history that had as many enforcement actions from as wide a diversity of countries as we saw in 2017. Last year saw successful enforcement in at least nine different member states including Denmark, France, Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands and Latvia. Both companies and individuals faced censure and even penalties.

Moreover, there was significant diversity in the sanctions regimes enforced: enforcement actions were made in light of violations against Russia, Crimea, Syria, Iran, Ukraine, DPRK, Al Qaida and Anti-Terrorism sanctions. The enforcement theories were also varied and included cases in which broad systems and controls failings were noted, and others in which the focus was more limited trade sanctions and export controls violations.

France

In France the highest-profile enforcement action has been that against LafargeHolcim in relation to alleged breaches of Syrian sanctions. The allegation is that LafargeHolcim paid some $5.6 million between 2012 and 2014 to designated persons in order to secure protection for its factories in Syria. A formal judicial inquiry was commenced on June 13, 2017.[79]

The French authorities have conducted raids at LafargeHolcim sites during November 2017, and interviewed a number of employees. On December 8, 2017 the former CEO Eric Olsen was formally charged in relation to the payments.[80]

Belgium

The Belgian authorities have also been investigating LafargeHolcim in relation to alleged breaches of Syrian sanctions, and in November 2017 the Belgian’s raised premises of a Lafarge-Holcim subsidiary in Belgium.[81]

Netherlands