February 11, 2019

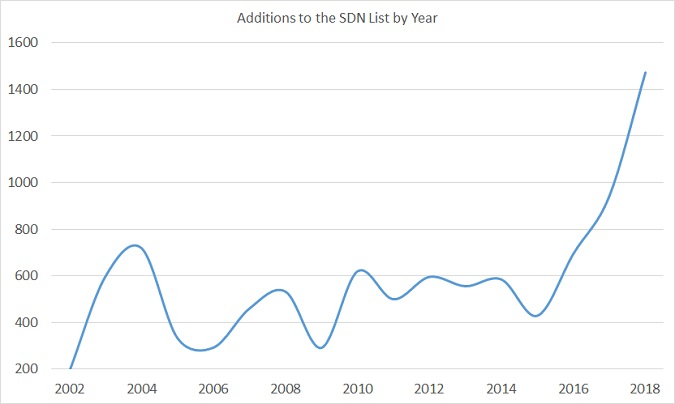

2018 was another extraordinary year in sanctions development and enforcement. This past year may take its place in history as the point at which the United States abandoned the Iran nuclear deal—the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (the “JCPOA”)—and re-imposed nuclear sanctions on Iran. Defying the expectations of many observers, the Trump administration went further than anticipated and re-imposed all nuclear-related sanctions on Iran, culminating in the November 5, 2018 addition of over 700 individuals, entities, aircraft, and vessels to the Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons (“SDN”) List—the largest single set of sanctions designations to date. This action increased the SDN List by more than 10 percent and brought the total number of persons designated in 2018 to approximately 1,500—50 percent more than has ever been added to the SDN List in any single year.

Source: Graph Compiled from Data Released by the Office of Foreign Assets Control

In any prior year, the U.S. decision to abandon the JCPOA would have dominated the pages of our client alerts. But 2018 was no ordinary year, and OFAC continued to enhance the impact of U.S. sanctions against Russia while rumors of election interference filled the airwaves. On April 6, 2018, the Trump Administration announced a bold set of new designations, including nearly 40 Russian oligarchs, officials, and related entities, including major publicly traded companies. After the companies took significant steps to disentangle from Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska, OFAC delisted EN+, Rusal, and JSC EuroSibEnergo (“ESE”) on December 19, 2018.

But that’s not all. Political and economic conditions in Venezuela continued to deteriorate, and in May Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro was elected to a new six-year term in an election that the United States government has described as a “sham” and “neither free nor fair.” Venezuela’s economy—which remains heavily dependent on the state-owned oil company, Petroleos de Venezuela, S.A. (“PdVSA”)—continued its sharp decline amid a collapse in oil production. Against that grim backdrop, the United States continued to gradually expand sanctions targeting members of President Maduro’s inner circle and sources of financing for the Venezuelan state. On January 28, 2019, OFAC formally designated PdVSA.

As with years past, 2018 witnessed the expanding use of sanctions as a foreign policy tool and will provide much fodder for those debating the long-term geopolitical impact of economic sanctions. But our purpose here is more circumspect: a recap of the continuing evolution of sanctions in 2018 and preparation for what may come next.

I. Major U.S. Program Developments

A. Iran

We have spilled much ink on the changing contours of the Iran sanctions regime. As we first described in our May 9 client alert, the re-imposition of Iran sanctions was subject to 90- and 180- day “wind-down” periods, expiring on August 6 and November 5, respectively. During these periods, companies were instructed to terminate Iran-related operations that would be targeted by the pending sanctions. OFAC placed the remaining sanctions relief into wind-down on June 27, as we described here, by withdrawing general authorizations that had permitted U.S. persons to negotiate contingent contracts related to commercial passenger aviation; import and deal in Iranian-origin carpets and foodstuffs; and facilitate the engagement of their non-U.S. subsidiaries in transactions involving Iran.

Upon the termination of the first wind-down period on August 6, as we described here, President Trump issued a new executive order authorizing the re-imposition of “secondary” sanctions targeting non-U.S. persons who engage in certain Iran-related transactions involving U.S. dollars, precious metals, the Iranian rial, certain metals, or Iranian sovereign debt. On November 5, as we described here, the remaining secondary sanctions were re-imposed. These included sanctions targeting non-U.S. person participation in transactions with Iran’s port operators or its shipping, ship building, and energy sectors; involving petroleum, petroleum products, petrochemicals, the National Iranian Oil Company (“NIOC”), Naftiran Intertrade Company (“NICO”), or the Central Bank of Iran; providing underwriting services, insurance, or reinsurance for sanctionable activities with or involving Iran; or involving Iranian SDNs. The United States also added a record number of individuals and entities to the SDN List, including entities that had previously been granted sanctions relief under the JCPOA, Iranian government or financial entities transferred from the List of Persons Blocked Solely Pursuant to E.O. 13599 (the “E.O. 13599 List”), and 300 first-time designees.

November 5 also marked the end of the wind-down period for General License H, which had authorized non-U.S. entities owned or controlled by U.S. persons to provide goods, services, or financing to Iranian entities under the terms of the JCPOA. The withdrawal of this authorization effectively subjected these non-U.S. entities to the same limitations on engagement with Iran that restrict their U.S. parents.

This broad array of re-imposed restrictions does not, however, entirely prevent U.S. persons or non-U.S. persons from engaging in Iran-related transactions. The Trump administration has provided sanctions waivers to eight countries that have pledged to significantly reduce their imports of Iranian crude oil, and has also purportedly waived sanctions for dealing with Iran’s Chabahar port—which is strategically important to the reconstruction of Afghanistan—and for certain nonproliferation efforts ongoing at several Iranian nuclear sites. Certain exceptions, including for transactions related to the Shah Deniz gas field (which is partly owned by the Government of Iran) and for transactions involving the export of agricultural commodities, food, medicine, or medical devices to Iran, also continue to apply. Additionally, General License D-1—which allows for the export of certain telecommunications goods and services to Iran—remains in force, as does General License J—which permits temporary visits to Iran by U.S.-origin aircraft (thus allowing international carriers to continue flying to Iran). Additionally, U.S. secondary sanctions do not apply to dealings with Iranian banks that are designated solely because of their status as “Iranian financial institutions” pursuant to Executive Order 13599, leaving certain payment channels open for otherwise permissible operations in Iran.

With the full array of pre-JCPOA sanctions re-imposed, we are now awaiting further reaction from the Trump administration, the Iranian leadership and the other signatories to the JCPOA. The Trump administration has stressed that it plans to adopt “the toughest sanctions regime ever imposed on Iran,” warning that “[m]ore are coming.” To date, OFAC has designated several tranches of individuals, entities, and aircraft linked to Iranian militias operating in Syria, including those announced on January 24, 2019. The Trump administration may also be likely to pursue aggressive enforcement efforts against persons that attempt to violate or circumvent U.S. sanctions, although the brief window between the re-imposition of sanctions and the U.S. government shutdown in late 2018 and early 2019 may have stalled such efforts. Additionally, Iranian entities could begin to react to the new, more restricted business environment, by for example pursuing legal action against their non-U.S. trading partners who have begun to exit Iran—sometimes with outstanding contractual obligations—given the risk of facing sanctions pursuant to the re-imposed secondary sanctions.

In response to the U.S. decision, as we described here, the EU supplemented its existing blocking statute to prohibit compliance by EU entities with the new U.S. sanctions on Iran. In early 2019, Britain, France and Germany established a European special purpose vehicle to facilitate non-U.S. dollar trade with Iran, circumventing many of the risks that EU entities face in complying with U.S. sanctions. The new measure, called the Instrument in Support of Trade Exchanges (“Instex”), will allow trade between the EU and Iran without relying on direct financial transactions. Instex has been registered in France, will be run by a German executive, and will have a supervisory board consisting of diplomats from Britain, France, and Germany.

B. Russia

1. New Designations

In addition to a significant expansion of U.S. sanctions on Iran, OFAC also continued to enhance the impact of U.S. sanctions against Russia while tensions between the two superpowers increased and rumors of election interference filled the airwaves. On April 6, 2018, as we analyzed here, the Trump administration announced a bold set of new designations, targeting nearly 40 Russian oligarchs, officials, and related entities, including major publicly traded companies such as EN+ and Rusal. In announcing the sanctions, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin cited Russia’s involvement in “a range of malign activity around the globe,” including the continued occupation of Crimea, instigation of violence in Ukraine, support of the Bashar al-Assad regime in Syria, attempts to subvert Western democracies, and malicious cyber activities.

These new sanctions carried broad macroeconomic implications for Russia’s business partners, including investors in the designated public companies. To minimize the immediate disruptions, OFAC issued two time-limited general licenses permitting companies and individuals to undertake certain transactions to “wind down” business dealings related to the designated parties. These licenses were extended numerous times throughout the course of the year, as the targeted companies attempted to extricate themselves from relationships with key leaders and investors that had triggered OFAC’s scrutiny.

As OFAC Director Andrea Gacki explained in a letter to Congress, the designation of three companies—EN+, Rusal, and ESE—was not OFAC’s primary intention but rather a reflection of their “entanglement” with Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska. On December 19, 2018, OFAC announced its intention to de-list all three entities (though Deripaska himself remains on the SDN List).

The three companies’ actions may serve as a roadmap for other entities seeking to distance themselves from sanctioned persons. EN+ made arrangements for Deripaska to reduce his ownership to less than 45 percent of its shares through transactions that would not involve transfers of funds to Deripaska, to reduce his voting rights in EN+ to no more than 35 percent, and to restructure its board, with eight out of 12 directors selected through a process intended to ensure their independence from Deripaska and half of the new board comprised of U.S. and UK nationals. Rusal and ESE—which are majority-owned by EN+—undertook specific commitments that, combined with the ownership and governance changes at EN+, similarly reduced Deripaska’s ownership and control. The three companies also agreed to significant OFAC reporting requirements to ensure transparency with respect to their compliance.

OFAC proceeded with the de-listings on January 27, 2019, which resulted in an immediate blowback from members of the newly elected Congress. Many members on both sides of the aisle clamored for a legislative response that would re-impose sanctions on the Russian entities, as the special counsel investigation lead by Robert Mueller continued to generate headlines. These efforts—much like the numerous pieces of legislation that were proposed in 2018 to ratchet up sanctions pressure on Russia—were ultimately unsuccessful.

2. CAATSA Implementation

Also in 2018, the Trump administration took steps toward the implementation of sanctions under the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (“CAATSA”), discussed in our November 21, 2017 alert. On September 20, 2018, President Trump issued Executive Order 13849, formally authorizing the Treasury and State Departments to issue sanctions under four sections of CAATSA: (i) Section 224(a)(2), which relates to materially assisting Russian government efforts to undermine cybersecurity; (ii) Section 231(a), which relates to significant transactions involving persons in or acting on behalf of the Russian defense or intelligence sectors; (iii) Section 232(a), which relates to the provision of goods or services that support the construction of Russian energy export pipelines; and (iv) Section 233(a), which relates to investments in the privatization of Russian state-owned enterprises to the benefit of government officials and their family members.

On the same day, the administration announced 33 additions to the list of individuals associated with the Russian defense and intelligence sectors under Section 231 of CAATSA (the “Section 231 List”), with whom significant transactions are prohibited. At the same time, the administration announced its first two SDN designations based on participation in significant transactions with an entity on the List of Specified Persons: the Chinese entity Equipment Development Department (“EDD”) and its director, Li Shangfu. EDD was designated based upon transactions with Russian arms exporter Rosoboronexport involving the purchase of ten Russian Sukhoi fighter jets and a “batch” of surface-to-air missiles.

Over the course of the year, OFAC also designated two dozen individuals and entities associated with Russian intelligence and election interference operations.

3. Chemical and Biological Weapons Act Sanctions

On August 8, 2018, the United States announced plans to impose additional sanctions on Russia in response to Russia’s alleged use of a nerve agent in the United Kingdom. The Chemical and Biological Weapons Control and Warfare Elimination Act of 1991 (the “CBW Act”) requires, in the event that the President determines that a foreign government has used chemical or biological weapons, two rounds of sanctions.

The first round of sanctions, imposed on August 22, 2018, expanded U.S. export controls to prohibit the export to Russia of items subject to the Export Administration Regulations (“EAR”) and controlled for national security reasons. Previously applicable exceptions—such as those covering exports for servicing and repair and for temporary exports—continue to apply. Further export authorizations may also be granted on a case-by-case basis. However, if, for example, no exception or authorization applies and the items are to be exported to a state-owned or -funded enterprise, requests for authorization to export covered items will be denied and their export prohibited.

The second round of sanctions, expected November 6, 2018 but now months overdue, must include at least three of six sanctions set forth in the CBW Act, unless waived by the President for national security reasons. Possible sanctions include restrictions on bank loans to the Russian government, the downgrade or suspension of diplomatic relations, and/or an expansion of export controls to broadly prohibit the export to Russia of all U.S.-origin items, regardless of the reason for their control. Despite its delay and the mandatory obligation, as of this writing it is not clear that the Trump administration will ever impose this second round of restrictions.

C. Venezuela

The United States sent shockwaves through markets on January 31, 2019, when it designated Venezuela’s state-owned oil company, PdVSA, to the SDN List, as we described here. The events of 2018 laid the groundwork for that decision, as the United States gradually increased sanctions pressure on the regime of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, who had been elected to a new six-year term in a May 2018 election that critics described as a “sham” and “neither free nor fair.” At the same time, Venezuela’s economy—which remains heavily dependent on PdVSA—continued its sharp decline amid a collapse in oil production. New measures imposed by the United States over the course of 2018 included a warning about transacting in Venezuela’s new cyber currency, further sanctions on certain debt and equity of the Government of Venezuela, as well as new sanctions targeting both Venezuela’s gold sector and corruption in government programs.

In February 2018, President Maduro announced that his government would begin issuing a new “cyber currency” known as the petro, in an effort to circumvent the use of U.S. dollars and the concomitant reach of OFAC regulations. In response, OFAC on March 19, 2018 issued its first official guidance discussing cyber currencies. Though perhaps not broadly applicable to the world’s more mainstream cyber currencies, it is noteworthy that OFAC held that its jurisdiction explicitly extended to the use of any new Venezuelan cyber currencies and that U.S. persons could face enforcement if they undertook dealings in the new currency. In a sign of things to come, OFAC also warned that it may add digital currency addresses associated with blocked persons to the SDN List and put the onus on individuals engaging in such transactions to screen potential counterparties and ensure that they are not dealing with banned persons. For a more detailed discussion of OFAC’s approach to cyber currencies like the petro, see our client alert, OFAC Issues Economic Sanctions Guidance on Digital Currencies (Oct. 5, 2018).

To further constrain the Maduro regime’s access to capital, the Trump administration in May 2018 expanded sanctions on certain financial instruments issued or sold by the Government of Venezuela. The “Government of Venezuela” is broadly defined to include not only its political subdivisions, agencies, and instrumentalities but also the Central Bank of Venezuela, PdVSA, and any entity that is at least 50 percent owned or controlled by these targeted entities.

The Trump administration first began targeting Venezuelan financial instruments in August 2017 with the issuance of Executive Order 13808, which was modeled in part on sectoral sanctions targeting Russia. Under that executive order, U.S. persons are prohibited from engaging in transactions involving (1) new debt owed by the Government of Venezuela with payment terms greater than 30 or 90 days (depending on the debtor), (2) new equity of the Government of Venezuela, (3) bonds issued by the Government of Venezuela, (4) dividend payments or other distributions of profits to the Government of Venezuela from any entity owned or controlled, directly or indirectly, by the Government of Venezuela, and (5) the purchase of securities from the Government of Venezuela. The scope of those sanctions is then cabined by four general licenses issued by OFAC. Executive Order 13808 is described at length in our client alert, President Trump Issues New Sanctions Targeting Certain Activities of PdVSA and the Government of Venezuela (Sept. 1, 2017).

Shortly following President Maduro’s re-election, President Trump on May 21, 2018 issued Executive Order 13835, which built on the measures described above by prohibiting U.S. persons from engaging in certain transactions involving debt owed to the Government of Venezuela, as well as certain transactions involving equity of Venezuelan state-owned entities.

The policy rationale behind those measures was twofold. The new restrictions on debt—which apply to transactions that involve either purchasing or pledging as collateral any debt owed to the Government of Venezuela, including accounts receivable—were designed to curtail the government’s ability to use accounts receivable financing to support its continued operations. (For example, a U.S. person would likely be prohibited from participating in transactions between a PdVSA customer and a PdVSA creditor where the customer paid its outstanding debt to the creditor, in lieu of payment to PdVSA.) At the same time, the restrictions on equity—which apply to transactions that involve the sale, transfer, assignment, or pledging as collateral by the Government of Venezuela of any equity interest in any entity in which the Government of Venezuela has a 50 percent or greater ownership interest—were calculated to prevent the Maduro regime from selling off valuable state-owned assets in “fire sales,” which deprive the Venezuelan people of “assets the country will need to rebuild its economy.” Executive Order 13835 and its implications are described at length in our client alert, President Trump Issues Additional Sanctions Further Targeting PdVSA and the Government of Venezuela (May 31, 2018).

In tandem with measures directed at Venezuela’s cyber currency and other more traditional financial instruments, the Trump administration also imposed new sanctions targeting Venezuela’s gold sector, which represents a vital source of hard currency (the cash-starved economy is home to some of the world’s largest known gold deposits). In 2018, Venezuela exported more than 23 tons of gold worth an estimated U.S. $900 million, giving rise to concerns on the part of U.S. officials that Venezuela’s natural resources were being “plundered” to enrich senior regime officials. More broadly, U.S. officials expressed concern that gold originating from Venezuela could find its way into the hands of other regimes the U.S. government views as unsavory, such as Iran, where it could be used to evade U.S. financial sanctions.

In response, the Trump administration on November 1, 2018 issued an executive order which imposed sanctions on persons who operate in the gold sector of the Venezuelan economy, engage in corruption involving Venezuelan government projects and programs, or who facilitate such activities. Additionally, the executive order gave the Treasury Secretary discretion to extend those sanctions to any other sector of the Venezuelan economy he deems appropriate, providing the basis for PdVSA’s designation in January 2019.

D. Other Programs

1. Sudan

On June 28, 2018, OFAC announced that it would be removing the Sudanese Sanctions Regulations (“SSR”) from the Code of Federal Regulations following the formal revocation of the SSR in October 2017. As we reported in our 2017 Sanctions Year-End Update, the Obama administration initiated the revocation process in January 2017. In addition to the removal of the SSR—which historically had included a trade embargo; a prohibition on the export or re-export of U.S. goods, technology and services; a prohibition on transactions relating to Sudan’s petroleum or petrochemical industries; and a freeze on the assets of the Sudanese government—OFAC officially incorporated into the Terrorism List Government Sanctions Regulations a general license authorizing certain exports of agricultural commodities, medicines, and medical devices to the Government of Sudan.

Sudan, however, remains subject to sanctions due to its inclusion on the State Sponsors of Terrorism List (“SST”), and sanctions previously imposed relating to the conflict in Darfur remain in place. Similarly, OFAC’s separate sanctions program relating to South Sudan remains in effect. Indeed, in June 2018 OFAC entered into a settlement agreement with two subsidiaries of Telefonaktiebolaget LM Ericsson, Ericsson AB and Ericsson, Inc. (collectively, “Ericsson”), for an apparent violation of the SSR that occurred years earlier, and on December 18, 2018, OFAC sanctioned three individuals and their related entities for providing weapons, vehicles, and soldiers to fuel the conflict in South Sudan.

2. Nicaragua

The regime of Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega—which the Trump administration has condemned for its human rights abuses and anti-democratic measures in response to civil protests—has become the subject of a new list-based sanctions program. On November 1, 2018, National Security Advisor John Bolton denounced the governments of Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua, dubbing them the “Troika of Tyranny” and threatening that “we will no longer appease dictators and despots near our shores.” Shortly thereafter, on November 27, 2018, President Trump issued Executive Order 13851 and declared a national emergency with respect to “the situation in Nicaragua, including the violent response by the Government of Nicaragua to the protests that began on April 18, 2018, and the Ortega regime’s systematic dismantling and undermining of democratic institutions and the rule of law,” violence against civilians, and corruption.

The executive order authorizes OFAC to block the property of anyone who, inter alia, with respect to Nicaragua: (1) commits human rights abuses; (2) undermines “democratic processes or institutions;” (3) threatens the country’s peace, security, or stability; (4) conducts transactions involving deceptive practices or corruption related to the Government of Nicaragua; or (5) has materially assisted in any of the activities described by categories 1 through 4. The sanctions also empower OFAC to designate anyone who is or has been a government official since January 10, 2007. Pursuant to this new program, OFAC has already added to the SDN list Rosario Maria Murillo de Ortega, the Vice President and First Lady, and Nestor Moncada Lau, the National Security Advisor to President Ortega. Prior to the issuance of this new sanctions program, FinCEN, in October 2018, also issued an advisory alerting the financial system to the risks posed by corruption in Nicaragua, particularly relating to the possibility that members of the Ortega government may try to move proceeds of corruption out of the country because of the threat of unrest and the specter of potential sanctions. The advisory noted that four Nicaraguan officials have already been sanctioned under the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act (the “Global Magnitsky Act”).

Further targeting the Ortega regime, on December 20, 2018, President Trump signed into law the Nicaragua Human Rights and Anticorruption Act, which had passed in the Senate on November 27, the same date Nicaragua sanctions went into effect. The statute instructs the U.S. executive directors at the World Bank Group and Inter-American Development Bank to oppose any loan for the Nicaraguan government’s benefit unless certain steps strengthening democratic institutions have been met. It is still too early to tell what effect this legislation, together with the new sanctions program, will have, but it is clear that companies must now take precautions when considering business opportunities in Nicaragua. The Nicaraguan government is firmly within the sights of the U.S. government.

3. North Korea

Although 2018 witnessed brief warming of relations between the United States and North Korea—marked by the June 12, 2018 summit between President Trump and Supreme Leader Kim Jong-un—relations between the countries have remained volatile, and OFAC has continued to push forward with its renewed focus on North Korea in connection with the U.S. government’s policy of denuclearizing the Korean Peninsula. In our 2017 Sanctions Year-End Update, we discussed the intensification of the North Korea sanctions program in the face of North Korea’s increasing bellicosity. New measures taken in 2017 included the enactment of a new section of CAATSA focusing on North Korea, the re-addition of North Korea to the state sponsors of terrorism list, and the issuance of a new executive order imposing sanctions on specific sectors of the North Korean economy and threatening to cut off access to the U.S. banking system for non-U.S. persons involved in North Korean trade.

OFAC continued to add North Korean individuals and entities to the SDN List throughout 2018, kicking off the year with a January 24, 2018 designation of nine entities, 16 individuals, and six vessels in response to North Korea’s “ongoing development of weapons of mass destruction” and violations of Security Council resolutions. One month later, on February 23, OFAC added to the SDN List what was billed as “the largest North Korea-related sanctions tranche to date,” aimed primarily at disrupting the regime’s shipping and trading companies. This action—which was focused on disrupting the activities of shipping companies that have been used to evade sanctions—designated an outstanding 56 individuals and entities across nine countries. That same day, OFAC joined the State Department and U.S. Coast Guard in issuing an advisory which highlighted the deceptive practices used by North Korea to evade U.S. sanctions so that companies, including financial institutions, can adequately implement controls to account for these practices. OFAC, together with the State Department and Department of Homeland Security, issued another similar advisory on July 23, 2018. This second advisory highlights North Korea’s evasion tactics that could expose businesses involved in the supply chain—such as manufacturers, buyers, and service providers—to risk and urged the implementation of proper controls and due diligence measures.

Last, though largely procedural, it is also worth noting that on March 1, 2018, OFAC amended and reissued the North Korea Sanctions Regulations and issued 14 new FAQs relating to the North Korea sanctions program.

As the year drew to a close and the new year began, the U.S. government’s position vis-à-vis North Korea once again was thrown into question. Although in December 2018 there were media reports of a new ballistic missile base being constructed in North Korea, in January 2019 the President reiterated that the United States is “doing very well” with respect to North Korea and is moving forward with scheduling a second summit to discuss the complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula. Regardless, based on developments in 2017 and 2018, it is likely that OFAC’s intensification of its North Korea program will continue apace in the coming year.

II. U.S. Enforcement

A. Designations

1. Designations of Iran-Based Persons with Digital Currency Addresses

On November 28, 2018, pursuant to its cyber-related sanctions program, OFAC designated Iranian residents Ali Khorashadizadeh and Mohammad Ghorbaniyan for facilitating the exchange of bitcoin payments into Iranian rial on behalf of cyber actors involved with the “SamSam” ransomware scheme, and depositing the rial into Iranian banks. Perpetrators of this scheme gain control of a victim’s computer network by installing unauthorized malicious software, and then demand the victim pay a ransom to regain control. There are at least 200 known victims of this scheme, including corporations, hospitals, universities, and government agencies.

In connection with these designations, OFAC listed identifying information that included two digital currency addresses associated with Khorashadizadeh and Ghorbaniyan. Digital currency addresses are alphanumeric identifiers linked to online wallets, from which and to which bitcoins or other digital currency can be transferred. According to OFAC, these two addresses were subject to over 7,000 bitcoin transactions (worth millions of U.S. dollars)—at least some of which were derivative of SamSam ransomware attacks. In the past, OFAC has listed a designee’s date of birth, email address, and nicknames, but this marks the first time it has listed a digital currency address. The Treasury Department had flagged this possibility earlier in 2018 when it published guidance stating that digital currency addresses may be listed “to alert the public” to specific property associated with a designated person. Like funds stored in a traditional bank account, digital currency associated with a digital currency address must be blocked by U.S. financial institutions if they are the property of designated persons.

We fully expect OFAC to continue this practice of listing a designated person’s digital currency address, particularly where the person operates in the digital currency space. Undersecretary of the Treasury for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence Sigal Mandelker has stressed that the administration is “aggressively pursuing Iran and other rogue regimes attempting to exploit digital currencies and weaknesses in cyber AML/CFT safeguards” and the importance of “publishing digital currency addresses to identify illicit actors” in this space. Indeed, as former senior Treasury adviser David Murray has pointed out, these addresses may be the most reliable identifiers for these bad actors.

2. Designations Related to Jamal Khashoggi

On October 10, 2018, a bipartisan group of 22 U.S. senators sent a letter to President Trump demanding that he investigate Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi’s disappearance and determine whether to impose sanctions on any culpable foreign government officials pursuant to the Global Magnitsky Act. President Trump was statutorily required to respond to the demand within 120 days. His response came a little over a month later, on November 15, 2018, when OFAC imposed Magnitsky sanctions on certain individuals it found were involved in the killing of Khashoggi. These individuals included senior Saudi government official Saud al-Qahtani; his subordinate, Maher Mutreb; Saudi Consul General Mohammed Alotaibi; and 14 other Saudi government officials.

The Global Magnitsky Act gives the President the authority to sanction individual perpetrators of serious human rights abuse and corruption. Trump’s use of Magnitsky sanctions with respect to the Khashoggi disappearance is not surprising. As we noted last year, President Trump issued an executive order in December 2017 effectively broadening his authority under the statute. Since then, more than one hundred individuals and entities have been sanctioned under this executive order. Moreover, President Trump has shown a willingness to act fast when imposing Magnitsky sanctions. As Senator Robert Menendez (D-NJ) put it, “When President Trump wants to move quickly on human rights sanctions he does.” For example, in early 2018, the Trump administration swiftly sanctioned two government ministers in Turkey over the imprisonment of American pastor Andrew Brunson.

While President Trump has been applauded for previous Magnitsky sanctions, a recurring critique of the Khashoggi-related sanctions is that they do not go far enough. Some in Congress have called for much tougher action against the Saudi government, such as curtailing arms sales or forcing a wind-down of Saudi involvement in Yemen’s destructive civil war. Indeed, although the United States has imposed Magnitsky sanctions on certain Saudi government officials, the government itself has escaped any direct punishment. Setting aside the merits of this critique, it appears the United States’ approach has been mirrored by its Western allies: Canada, France, and Germany have all imposed sanctions on individuals culpable in the killing of Khashoggi, but not on the Saudi government.

B. Enforcement Actions

2018 was a deceptively quiet year for OFAC sanctions enforcement. The agency netted U.S. $71,510,561 in penalties through seven enforcement actions in 2018, compared to 16 enforcement actions and over U.S. $119,527,845 in penalties in the prior year. But the numbers belie a more aggressive approach to enforcement, masked in certain circumstances by OFAC’s relatively small stake of large global settlements with other regulators. Moreover, in December 2018 Treasury Undersecretary Sigal Mandelker announced significant changes already underway in sanctions enforcement with a goal of “better enforcement through compliance.” Mandelker explained that OFAC would be outlining the hallmarks of an effective sanctions compliance program in an effort to aid the compliance community in strengthening defenses against sanctions violations. Foreshadowing a more aggressive approach to enforcement, she noted that compliance commitments would become an essential element in settlement agreements between OFAC and apparent violators.

As we were going to press, OFAC settlement with the Kollmorgen Corporation provided a clear indication of the new frontiers in OFAC enforcement. The case concerned the company’s Turkish affiliate’s alleged violations of Iran sanctions. Especially noteworthy was that this was the first time OFAC concurrently concluded a settlement action while also designating an individual who allegedly managed the Iranian operations for evading sanctions.

Undersecretary Mandelker noted that the action was “a clear warning that anyone in supervisory or managerial positions who directs staff to provide services, falsify records, commit fraud, or obstruct an investigation into sanctions violations exposes themselves to serious personal risk.”

1. Zhongxing Telecommunications Equipment Corporation

On April 15, 2018, the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (“BIS”) activated a denial order against Chinese telecommunications company Zhongxing Telecommunications Equipment Corporation (“ZTE”) for its alleged failure to abide by terms of a March 2017 settlement agreement. As we described in our 2017 Sanctions Year-End Update, ZTE previously agreed to settle its potential civil liability for alleged violations of OFAC’s Iran sanctions for U.S. $100,871,266, part of a combined U.S. $1.19 billion civil and criminal settlement with BIS and the U.S. Department of Justice (“DOJ”). As part of the settlement, ZTE agreed to a seven-year suspended denial of export privileges, which could be activated if any aspect of the agreement was not met.

BIS decided to impose the order based on information suggesting that ZTE made false statements regarding the disciplinary measures imposed on employees responsible for the illegal activity. Specifically, ZTE informed U.S. authorities that the company had taken or would take action against 39 employees and officials that ZTE identified as having a role in the violations. But letters of reprimand were not issued until after BlS requested further information in February 2018, and all but one of the individuals involved in the underlying misconduct received his or her 2016 bonus.

Denial orders are among the most powerful weapons BIS has in its civil enforcement tool box, and would have imposed strict penalties and licensing requirements on U.S. and non-U.S. persons involved, directly or indirectly, in any transaction related to the export or reexport of U.S. origin items to ZTE. However, in July 2018, after initial trade negotiations with Chinese President Xi Jinping, President Trump instructed BIS to work out an arrangement that would ultimately lift the restrictions. BIS subsequently terminated the order after ZTE paid a U.S. $1 billion penalty, replaced its board, and placed U.S. $400 million in escrow pursuant to the superseding settlement agreement, in addition to the U.S. $361 million in penalties ZTE had already paid to BIS under the original March 2017 settlement. ZTE was also required to retain an external compliance coordinator for a period of ten years to monitor and report on ZTE’s compliance.

2. DOJ Charges Russian and Syrian Nationals for Syrian Sanctions Violations

In June 2018, eight businessmen, including five Russian nationals and three Syrian nationals, were indicted on federal charges alleging that they conspired to violate U.S. economic sanctions against Syria and Crimea by sending jet fuel to Syria and making U.S. wire transfers to Syria and to sanctioned entities in Syria absent a license from the U.S. Treasury Department.

According to the indictment, beginning in 2011, the alleged conspirators started using front companies and falsifying information in shipping records and the related U.S. dollar wires in order to circumvent sanctions. From 2011 to 2017, the alleged conspirators engaged in business with various blocked entities and used front companies to do so.

C. Select OFAC Enforcement Actions

1. Ericsson

In June 2018, two subsidiaries of Ericsson agreed to pay U.S. $145,893 in a settlement with OFAC for an apparent violation of U.S. sanctions on Sudan, scarcely three weeks before OFAC announced that it would be removing the Sudan sanctions from the CFR. The Sudan sanctions were revoked in October 2017, and the Ericsson enforcement action provides a warning regarding OFAC’s willingness to pursue historical violations, even in the face of changing U.S. policies.

In late 2011, some of Ericsson’s telecom equipment located in Sudan malfunctioned. Consequently, two Ericsson employees and a senior director requested assistance from an EUS specialist in an attempt to repair the damaged equipment. The specialist informed them that Ericsson could be fined for engaging in such business activities in Sudan. Despite this, Ericsson’s subsidiary and personnel continued to discuss repairing the damaged equipment, but removed any references to Sudan from the correspondence. Despite being warned on another occasion by Ericsson’s compliance department that replacing the equipment in Sudan would violate U.S. sanctions, Ericsson personnel continued to plan the replacement of the equipment and also engaged a third party in doing so. Ultimately, Ericsson personnel decided to solve the issue by purchasing an export-controlled U.S.-origin satellite hub capable of withstanding the heat in Sudan, and then engaged in a multistage transaction involving transshipping the hub through Switzerland and Lebanon en route to its final destination in Sudan.

Notably, this enforcement action involved alleged violations that took place as far back as 2012 and earlier, prior to the revocation of certain Sudan sanctions. While the statute of limitations for violations of U.S. sanctions is generally five years from the offending conduct, Ericsson entered into a tolling agreement with OFAC in order to fully cooperate with the investigation.

2. Epsilon

In September 2018, Epsilon Electronics Inc. (“Epsilon”) agreed to pay U.S. $1,500,000 to settle liability for alleged violations of OFAC’s Iran sanctions. OFAC issued Epsilon a penalty notice in 2014, alleging that, from August 2008 to May 2012, Epsilon had committed 39 violations for its sales to a company that Epsilon knew or had reason to know distributed most, if not all, of its products to Iran.

The settlement followed a decision by a split panel of the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals in 2017 to set aside OFAC’s initial $4.07 million penalty. The case considered OFAC’s prohibition of the transshipment of U.S. goods to Iran through third countries, or the “general inventory rule,” which sets forth a standard of liability based on an exporter’s “knowledge or reason to know” that such goods are ultimately intended specifically for Iran. The D.C. Court of Appeals upheld OFAC’s determination that an exporter could be liable where substantial evidence supported a conclusion that all of the relevant third-country customer’s sales were to Iran during one set period of time. However, it also held that OFAC’s determination of a violation was arbitrary and capricious with respect to alleged violations that took place during another period of time because the agency failed to adequately consider all evidence presented by the company regarding sales it reasonably believed to have been made outside of Iran.

OFAC considered the following in determining a penalty: (1) the violations constituted a systematic pattern of conduct; (2) Epsilon exported goods valued at U.S. $2,823,000 or more; (3) Epsilon had no compliance program at the time of the violations; (4) Epsilon had not received a penalty notice in the five years preceding the transactions at issue; (5) Epsilon is a small business; and (6) Epsilon provided some cooperation to OFAC in addition to taking independent remedial action.

3. JPMorgan Chase

In October 2018, JP Morgan Chase Bank, N.A. (“JP Morgan”) agreed to remit U.S. $5,263,171 to OFAC to settle its potential civil liability for apparent violations of U.S. sanctions. This action demonstrates the culpability that U.S. financial institutions may face for processing transactions involving sanctioned targets—in this case, JP Morgan operated a net settlement mechanism that resolved billings by and among various airlines and airline industry participants, including several parties that were at various times on the SDN List. Between January 2008 and February 2012, JP Morgan processed 87 transactions with a total value of over U.S. $1 billion, U.S. $1,500,000 (0.15%) of which were attributable to the interests of designated entities.

Separately, OFAC issued a Finding of Violation to JP Morgan—with no concomitant penalty—for violations relating to deficiencies in its sanctions screening mechanism. Between August 2011 and April 2014, the bank’s screening system failed to identify six customers as SDNs, resulting in the processing of 85 transactions totaling $46,127.04 in violation of U.S. sanctions. JP Morgan’s screening logic capabilities purportedly failed to identify customer names with hyphens, initials, or additional middle or last names as potential matches to similar or identical names on the SDN List. Despite strong similarities between the accountholder’s names, addresses, and dates of birth in JP Morgan’s account documentation and on the SDN List, JP Morgan maintained accounts for, and/or processed transactions on behalf of, the six customers.

Notably, JP Morgan identified weaknesses in the screening tool’s capabilities as early as September 2010 and implemented a series of enhancements during the period 2010 to 2012. After transitioning to a new screening system in 2013, the bank re-screened 188 million clients’ records through the new system and identified the suspect transactions. JP Morgan voluntarily self-disclosed the matter to OFAC.

4. Société Générale

In November 2018, OFAC joined regulators from the Federal Reserve, DOJ, New York County District Attorney’s Office, U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York, and New York State Department of Financial Services (“DFS”) in a combined settlement agreement with Société Générale (“SocGen”) for apparent violations of U.S. sanctions, among other matters. SocGen agreed to pay U.S. $53,966,916 to OFAC as part of a $1.34 billion global settlement agreement. Unlike in any other major banking case of which we are aware—and in line with the increasing aggressiveness of enforcement that Undersecretary Mandelker would make public a month later—OFAC did not credit the penalties assessed by other regulators or agencies. The OFAC penalty was to be paid on top of the other penalties assessed.

The settlement documents alleged that SocGen processed transactions involving countries and persons subject to U.S. sanctions programs through U.S. financial institutions for five years up to and including 2012. OFAC alleged that SocGen processed such transactions after removing, omitting, obscuring, or failing to include references to sanctioned parties in the information submitted to U.S. financial institutions and ignored warning signs that its conduct was in violation of U.S. sanctions regulations.

In addition to enforcement actions by federal regulators, DFS entered into two consent orders with SocGen and its New York branch under which SocGen will pay fines totaling $420 million for violations under U.S. sanctions programs and New York anti-money laundering laws.

The DFS investigation found that from 2003 to 2013 SocGen failed to take sufficient steps to ensure compliance with U.S. sanctions laws and regulations. Namely, individuals responsible for originating U.S. dollar transactions outside of the United States had a minimal understanding of U.S. sanctions laws as they pertained to Sudan, Iran, Cuba, North Korea, and other sanctions targets.

5. Mashreqbank

In addition to the SocGen matter, in October 2018 DFS fined United Arab Emirates-based bank, Mashreqbank PSC (“Mashreqbank”) and its New York branch in the amount of U.S. $40 million for deficiencies in its compliance programs, including its compliance policy regarding U.S. sanctions, and for violations to the U.S. Bank Secrecy Act and anti-money laundering (“AML”) laws in its U.S. dollar clearing operations. Under the consent order announced by DFS and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Mashreqbank must immediately hire a third-party compliance consultant to oversee and address deficiencies in the branch’s compliance function, including compliance with AML requirements, federal sanctions laws, and New York law and regulations. In addition, Mashreqbank must hire a third-party “lookback consultant” to conduct a review of the branch’s transaction clearing activity for April 2016 to September 2016, along with other remedial actions.

DFS conducted a safety and soundness examination of the New York branch’s operations in 2016, finding that the branch had been unable to meet its compliance commitments. DFS identified defects in the bank’s OFAC compliance program and found that its OFAC policies lacked detail, nuance or complexity. The examination also found that each transaction monitoring alert would be reviewed only once by a single reviewer, who would then determine whether the alert should be closed or escalated, but without adequate quality assurance reviews. The branch’s OFAC program also suffered from certain deficiencies in important aspects of its recordkeeping. Specifically, Mashreqbank maintained inadequate documentation concerning its dispositions of OFAC alerts and cases, with branch compliance staff failing to properly record its rationales for waiving specific alerts.

III. European Union Developments and Enforcement

In 2018, the European Union (“EU”) broadly stayed the course it set in 2017 and modestly extended the scope of its sanctions programs on Iran and Russia. Additional sanctions were adopted, namely with respect to Venezuela and Mali.

The most significant sanctions-related development this year at the EU level has been that, following the unilateral withdrawal of the United States from the JCPOA, the so-called “EU Blocking Statute” was expanded, prohibiting EU nationals from complying with requirements or prohibitions contained in those sanctions or applied by means of rulings under those sanctions. While there has not been enforcement action to date, the first lawsuits and judgments making reference to the EU Blocking Statute have begun to emerge. This divergence between U.S. and EU policy on Iran sanctions has caused and is likely to cause in the future significant compliance hurdles for multinational companies.

A. Legislative Developments

1. Iran

In response to the U.S. decision to abandon the JCPOA, on August 6, 2018 the European Union enacted Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2018/1100 (the “Re-imposed Iran Sanctions Blocking Regulation”), which amended the EU Blocking Statute. The EU Blocking Statute is a 1996 European Commission Regulation (EC) No 2271/96 that was designed as a countermeasure to what the EU considers to be the unlawful effects of third-country (primarily U.S.) extra-territorial sanctions on “EU operators.” The combined effect of the EU Blocking Statute and the Re-imposed Iran Sanctions Blocking Regulation is to prohibit compliance by EU entities with U.S. sanctions which have been re-imposed following the U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA.

The EU Blocking Statute applies to a wide range of actors including:

- any natural person being a resident in the EU and a national of an EU Member State;

- any legal person incorporated within the EU;

- any national of an EU Member State established outside the EU and any shipping company established outside the EU and controlled by nationals of an EU Member State, if their vessels are registered in that EU Member State in accordance with its legislation;

- any other natural person being a resident in the EU, unless that person is in the country of which he or she is a national; and

- any other natural person within the EU, including its territorial waters and air space and in any aircraft or on any vessel under the jurisdiction or control of an EU Member State, acting in a professional capacity.

Accompanying the Blocking Statute, the EU issued a Guidance Note: Questions and Answers: adoption of update of the Blocking Statute, which notes that subsidiaries of U.S. companies formed in accordance with the law of an EU Member State and having their registered office, central administration or principal place of business within the EU are subject to the EU Blocking Statute; although mere branch offices of U.S. companies, without separate legal personality, are not.

The EU Blocking Statute requires (Article 2) parties to which it applies whose economic and/or financial interests are affected, directly or indirectly, by certain extra-territorial U.S. sanctions laws (including those re-imposed in 2018) or by actions based thereon or resulting therefrom, to inform the European Commission accordingly within 30 days from the date on which it obtained such information. With respect to companies, this obligation applies to the directors, managers and other persons with management responsibilities. We refer to this as the “Notification Obligation.”

The EU Blocking Statute also prohibits (Article 5) EU operators from complying, whether directly or through a subsidiary or intermediary, and whether actively or by omission, with any prohibition or requirement contained in a set of specific extra-territorial laws or any decisions, rulings, or awards based on those laws. However, the EU Blocking Statute does also provide for authorization to engage in such activities.

The U.S. sanctions laws to which the EU Blocking Statute applies are explicitly listed, and include six U.S. sanctions laws and one set of U.S. regulations (OFAC’s Iranian Transactions and Sanctions Regulations).

The Blocking Statute entered into effect on August 7, 2018 and does not allow for any grandfathering of pre-existing contracts or agreements. The EU Guidance noted above indicates that EU operators are prohibited from even requesting a license from the United States to maintain compliance with U.S. sanctions. Requesting such permission—without first seeking authorization from the European Commission or a competent authority in a Member State to apply for it—is tantamount to complying with U.S. sanctions.

The Blocking Statute also provides that decisions rendered in the United States or elsewhere made due to the extraterritorial measures blocked by the EU Blocking Statute cannot be implemented in the EU. This means, for instance, that any court decision made in light of the extraterritorial measures cannot be executed in the EU, even under existing mutual recognition agreements.

Finally, the EU Blocking Statute allows EU operators to recover damages arising from the application of the extraterritorial measures. Though it is unspecified how this would work under the various laws of the EU member states, it appears to allow an EU operator suffering damages because of a company’s compliance with the U.S. sanctions to assert monetary damage claims. For instance, if a European company has a contract to provide certain goods to Iran, non-fulfillment of that contract to comply with U.S. sanctions would be a violation of the Blocking Statute. However, if some of the European company’s goods are supplied from companies that decided to comply with U.S. sanctions and, therefore, refuse to further supply these goods, this may result in the European company not being able to meets its obligations vis-à-vis its Iranian customer. In such a case, the Iranian company could sue the European company for breach of contract, and the European operator could in turn sue its supplier for the damages caused due to the supplier’s compliance with the extraterritorial U.S. sanctions.

We have described the generally available possible options for affected companies here.

As an EU Regulation, the EU Blocking Statute is directly applicable in the courts of any Member State without the need for domestic implementing legislation. However, it is the competent domestic authorities of the EU Member States (not the European Commission) that are responsible for the enforcement of the EU Blocking Statute, including implementation of penalties for possible breaches. Such penalties are laid down in national legislation and vary by Member State. Some EU member states have in place, or have introduced, criminal offences applicable to violations of the EU Blocking Statute (notably the UK, Ireland and Germany); others maintain administrative penalties, but not criminal offences (notably Spain and Italy). Certain member states, notably France and Belgium, appear not to have introduced legislation to implement the EU Blocking Statute.

2. Russia

Since March 2014, the EU has progressively imposed EU Economic and EU Financial Sanctions against Russia. The EU Russia Sanctions were adopted in response to deliberate destabilization of (particularly Eastern) Ukraine and the annexation of Crimea.

EU Russia Economic Sanctions include an arms embargo, an export ban for dual-use goods for military use or military end users in Russia, limited access to EU primary and secondary capital markets for major Russian majority state-owned financial institutions and major Russian energy companies, and limited Russian access to certain sensitive technologies and services that can be used for oil production and exploration.

In particular, in broad alignment with U.S. sanctions, EU Russia Economic Sanctions prohibit the sale, supply, transfer, or export of products to any person in Russia for oil and natural gas exploration and production in waters deeper than 150 meters, in the offshore area north of the Arctic Circle and for projects that have the potential to produce oil from resources located in shale formations by way of hydraulic fracturing. The provision of associated services (such as drilling or well testing) is also prohibited, while authorization must be sought for the provision of technical assistance, brokering services, and financing relating to the above.

However, there are certain noteworthy differences in the nuances. The above-detailed latest round of U.S. Russia Sectoral Sanctions due to CAATSA have created some disparities between the U.S. and the EU regimes. The EU Russia Economic Sanctions are currently in place until July 31, 2019. Also, the EU Russia Financial Sanctions were further extended in September 2018 until March 15, 2019. As of now, 164 people and 44 entities are subject to a respective asset freeze and travel ban.

For those subject to EU Financial Sanctions, EU member states may authorize the release of certain frozen funds or economic resources to satisfy the persons and their dependents’ basic needs, for payment of reasonable professional fees, for payment for contracts concluded before the sanction and for claims secured to an arbitral decision rendered prior to the sanction.

In a recent development, the EU on January 21, 2018 targeted with EU Financial Sanctions two senior Russian military intelligence officials and two of their officers accused of the poisoning of a former Russian double agent in Britain, Mr. Skripal, and his daughter.

The EU still does not recognize the annexation of Crimea and Sevastopol by Russia, and the EU imposed broad sanctions against these territories in 2014. The EU Crimea Sanctions included an import ban on goods from Crimea and Sevastopol, broad restrictions on trade and investment related to economic sectors and infrastructure projects in Crimea and Sevastapol, an export ban for certain goods and technologies to Crimea and Sevastapol and a prohibition to supply tourism services in Crimea or Sevastopol. On June 18, 2018, the EU Council extended the EU Crimea Sanctions until June 23, 2019. These restrictions are similar to those in place in the United States.

3. Venezuela

Following the U.S. lead on Venezuela sanctions, on November 13, 2017, the EU had decided to impose an arms embargo on Venezuela, and also to introduce a legal framework for travel bans and asset freezes against those involved in human rights violations and non-respect for democracy or the rule of law. Subsequently, on January 22, 2018, the EU published an initial list of seven individuals subject to these sanctions.

On June 25, 2018, the EU added an additional eleven individuals holding official positions to the EU Venezuela Financial Sanctions for human rights violations and for undermining democracy and the rule of law in Venezuela.

Though these measures are not yet as severe as U.S. measures on Venezuela—and the EU stated that the sanctions can be reversed if Venezuela makes progress on these issues— the Council was also explicit previously in its warning that the sanctions may be expanded if the situation worsens.

On November 11, 2018, the EU Venezuela Sanctions were prolonged until November 14, 2019.

4. North Korea

As noted in last year’s sanction update and above with respect to U.S. measures, the events on the Korean Peninsula in 2017 also gave rise to significant new EU measures against North Korea. While the first half saw a further increase in EU North Korea Financial and Economic Sanctions, the second half of 2018 eased some of the tension due to, inter alia, high-level meetings between South and North Korean, the United States, and China, without however (yet) changing the EU North Korea Sanctions Framework.

On January 8, 2018, the EU Council added 16 persons and one entity to the EU North Korea Financial Sanctions, making them subject to an asset freeze and travel restrictions. This decision implemented a part of the sanctions imposed by the UN Security Council on December 22, 2017 with resolution 2397 (2017).

On January 22, 2018, the EU Council autonomously added 17 citizens of the DPRK to the EU North Korea Financial Sanctions, due to their involvement in illegal trade activities and activities aimed at facilitating the evasion of sanctions imposed by the UN.

On February 26, 2018, the EU implemented further UN Security Council resolution 2397 (2017) and accordingly expanded its EU North Korea Economic Sanctions regime and strengthened the export ban on North Korean refined petroleum products by reducing the amount of barrels that North Korea may export from two million barrels to 500,000 barrels per year; banned imports of North Korean food and agricultural products, machinery, electrical equipment, earth, stone, and wood; banned exports to North Korea of all industrial machinery, transportation vehicles as well as iron, steel, and other metals; introduced further sanctions against vessels where there are reasonable grounds to believe that the vessel has been involved in the breach of UN sanctions; and demanded the repatriation of all North Korean workers abroad within 24 months.

On April 6, 2018, the EU added one person and 21 entities to the EU North Korea Financial Sanctions, implementing a decision of March 30, 2018 by the UN Security Council Committee. Also, the EU has implemented the asset freeze targeting 15 vessels, the port entry ban on 25 vessels and the de-flagging of 12 vessels.

On April 19, 2018, the EU—in yet another round of autonomous EU North Korea Sanctions—added four persons to the EU North Korean Financial Sanctions. The four individuals were targeted due to their involvement in financial practices suspected of contributing to the nuclear-related, ballistic-missile-related or other weapons of mass destruction-related programs of North Korean.

By the end of 2018, accordingly, 59 individuals and 9 entities were designated autonomous by EU North Korea Financial Sanctions; and in addition, 80 individuals and 75 entities are subject to EU Financial Sanctions due to the implementation of respective sanctions of the UN.

5. Mali

On September 28, 2017, the European Union Council Decision (CFSP) 2017/1775 implemented UN Resolution 2374 (2017), which imposes travel bans and assets freezes on persons who are engaged in activities that threaten Mali’s peace, security, or stability. Interestingly, the imposition of this regime was requested by the Malian Government, due to repeated ceasefire violations by militias in the north of the country. Affected persons will be determined by a new Security Council committee, which has been set up to implement and monitor the operation of this new regime, and will be assisted by a panel of five experts appointed for an initial 13-month period. For a long time no individuals were actually designated.

On December 20, 2018, the Security Council Committee added three individuals to its Mali sanctions list: Ahmoudou Ag Asriw, Mahamadou Ag Rhissa, and Mohamed Ousmane Ag Mohamedoune. Each of them were targeted with a travel ban.

On January 10, 2019, the EU implemented these UN listings in respective EU Mali sanctions by Council Implementing Decision (CFSP) 2019/29. As a result of this implementation, the above-mentioned individuals will now be subject to EU-wide travel bans.

B. Judgments

1. Mamancochet Mining v Aegis

On October 12, 2018, the High Court handed down a judgment making reference to the EU Blocking Statute. The case, which involved a non-U.S. subsidiary of a U.S. insurance entity, could provide importance guidance for U.S. companies and their EU, or at least UK, subsidiaries.

The case arose from a dispute between UK-based insurers that are owned or controlled by U.S. persons and their customer, regarding the scope of contractual provisions excusing the parties from performance if transactions pursuant to the contract created sanctions exposure. The insured had submitted a claim under its marine insurance contract to recover the cost of goods stolen in Iran. The insurance underwriters asserted they were not required to pay that Iran-related claim pursuant to a provision in the insurance contract excusing performance if “payment…would expose that insurer to any sanction, prohibition or restriction” under applicable sanctions.

The court held that, prior to the revocation of General License H on November 4, payment of a valid claim by the insured did not “expose” the insurers to sanctions because it would not breach applicable sanctions. While General License H was in effect, non-U.S. subsidiaries of U.S. entities would not be prohibited from engaging in such transactions. These transactions would have only breached sanctions—and therefore created sanctions exposure—after November 4, when non-U.S. subsidiaries of U.S. persons were no longer generally authorized to engage in transactions involving Iran. For the UK Commercial Court, conduct creating the risk of sanctions exposure—rather than actual exposure through breach of applicable restrictions—did not excuse the insurers’ performance. Had the insurers wanted to suspend performance when faced only with risk of sanctions exposure, the court suggests they could have expressly indicated that performance would be excused if “payment…would expose that insurer to any risk of being sanctioned.”

The case suggests that insurance providers and brokerages, should be precise and comprehensive when describing the sanctions-related circumstances that trigger suspension or excuse-of-performance clauses and must describe clearly the effect of such provisions when triggered.

These clauses must also clearly describe the effect of their invocation. In this case, the contract provided that “no (re)insurer shall be liable to pay any claim . . . to the extent that the provision of such . . . claim . . . would expose that (re)insurer” to applicable sanctions. The court found this provision would only suspended the insurers’ payment obligations, rather than terminate them. This suggests that, just as insurers should be precise in describing the circumstances that trigger these excuse-of-performance clauses, they must also be precise in describing the effect of those provisions when they are triggered.

In this case, the insured also sought to rely upon the EU Blocking Regulation in the event that the insurance underwriters were otherwise entitled to rely upon the sanctions clause to resist payment. While this issue did not arise for determination, the court noted, rather than held, that considerable force was inherit in the argument that the EU Blocking Regulation is not engaged where the insurer’s liability to pay a claim is suspended under a sanctions clause such as the one in the policy at hand. In such a case, the court noted, the insurer is not “complying” with a third country’s prohibition but is simply relying upon the terms of the policy to resist payment.

2. EU Blocking Statute Challenge by Rotenberg

In October, Russian oligarch Boris Rotenberg filed a law suit with the Helsinki District Court against Nordea, Danske Bank and Svenska Handelsbanken. Rotenberg claims that the banks refused to provide certain services in order to comply with secondary U.S. sanctions. The case is pending.

C. Enforcement

1. France

In France, “l’affaire Lafarge” remains the most prominent enforcement action. In June 2018, the French judiciary initiated a formal investigation to examine whether LafargeHolcim had paid nearly $13 million to the Islamic State to protect one of its cement plants in Syria. The corporation as a legal entity has been charged by a panel of three French judges appointed by the Paris High Court with violating the European embargo on oil purchases. In addition, the charges also include financing a terrorist organization, endangering the lives of former employees and complicity in crimes against humanity.

2. Belgium

Belgian authorities started prosecution of three Belgian companies AAE Chemie, Anex Customs and Danmar Logistics and two of their managers. Allegedly, the firms exported chemicals used to produce sarin gas to Syria without applying for the necessary export licenses. Prior to the proceedings, the Belgian Finance Ministry had offered a financial settlement but the companies refused. The trial started in Antwerp in May 2018, a verdict is expected for January 2019.

3. Germany

The German government is facing resistance against its recent decision to halt arms exports to Saudi Arabia. While not based on EU sanctions, but rather based on a political decision, the result for German defense suppliers remains the same. German defense suppliers recently announced a plan to sue for damages resulting from the ban of all arms exports to Saudi Arabia. The ban was established in November 2018 after details about the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi surfaced. The restrictions apply to exports that had previously been approved by the German government.

4. The United Kingdom

There have been a number of enforcement actions in respect of sanctions and export control violations completed in 2018, the two most significant of which are:

(i) terms of imprisonment ranging from six months suspended (on a married couple associated with a small UK company Pairs Aviation) to 2½ years in respect of UK businessman, Alexander George, convicted of exporting certain military aircraft items to Iran, through companies in a number of jurisdictions, including Malaysia and Dubai; and

(ii) the imposition by the Financial Conduct Authority in June 2018 of a financial penalty of almost £900,000 (reduced by 30 percent on account of early settlement) on Canara Bank for systems and controls inadequacies relating, inter alia, to sanctions. This matter related to that institution’s trade finance operations.

There were also three prosecutions of UK companies in 2018 in respect of unlicensed exports of military or dual-use goods, including chemicals and metals, with relatively modest fines imposed.

IV. United Kingdom Developments and Enforcement

A key focus of attention of sanctions professionals in the United Kingdom this year has been the likely treatment of EU sanctions post-Brexit.

On October 12, 2018, the UK’s Office for Financial Sanctions Implementation, which is part of HM Treasury, circulated a technical notice issued by another UK Ministry, the Department for Exiting the European Union (“DEXEU”), considering the implications for sanctions law in the UK in the event of a “no-deal Brexit.” A no-deal Brexit is a scenario in which the UK does not reach an agreement with the European Union in connection with the future trading relationship between them by 11pm March 29, 2019 (midnight on March 30, 2019 CET), the date on which the UK is currently due to exit the EU.

Whilst the UK does introduce its own sanctions legislation from time to time (and can be expected to do so following Brexit), the majority of UK sanctions instruments are introduced in implementation of EU sanctions. EU sanctions regimes are brought into effect by legislative instruments passed at EU level, typically Decisions and Regulations of the Council of the EU. EU Decisions are binding only on the persons to whom they are addressed; EU Regulations are binding on all persons and are automatically applicable in the domestic courts of the EU member states.

However, the EU Member States have not given the EU competence to create criminal offences; only the Member States themselves can do that. As such, EU sanctions instruments do not, by themselves, create criminal offences in the domestic legal orders of the EU Member States. In order to create such criminal offences, domestic implementing legislation is generally required. EU Member States take a variety of different approaches to such implementing legislation. Some Member States have a standing implementing law which creates a criminal offence of violation of EU sanctions in force, so that as soon as a new EU Regulation implementing sanctions is brought into force, breach thereof will be an offence in the domestic legal order. The UK does not take this approach. Instead, in the UK, new delegated legislation (in the form of implementing regulations) is adopted each time the EU introduces (and sometimes when it amends) a sanctions regime, and it is those new implementing regulations that create the criminal offences in question.

The UK’s future relationship with EU law in its national legal orders following Brexit will depend on the final terms of the Withdrawal Agreement that the UK is currently seeking to negotiate with the EU and any subsequent trade agreements regarding the future trading relationship. There remains some uncertainty as to what these agreements will contain—and there is a possibility that no agreement will be reached. In the event of a “no deal” Brexit, the UK will not be obliged automatically to adopt EU sanctions following Brexit.

The question also arises as to the legal basis of EU sanctions in effect at the point the UK leaves the EU, given that the underlying EU legal basis for those sanctions will no longer apply to the UK. In order to avoid legal lacunae resulting from Brexit, the UK passed in 2018 the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018, which enacts certain savings for EU-derived legislation, direct EU legislation and EU law-derived rights. This Act provides, in broad summary, that all of these will be deemed to have effect as domestic law in the UK (i.e., English law, Scots law and the law of Northern Ireland) on and after Brexit day, save to the extent that Parliament enacts regulations modifying or negating the relevant law.

The technical notice sets out the policy of the UK Government regarding sanctions in the event of a “no deal” Brexit. The relevant section of the technical notice reads as follows:

As international law requires, we will implement UN sanctions in UK domestic law after the UK leaves the EU.

If the UK leaves the EU without a deal, we will look to carry over all EU sanctions at the time of our departure. We will implement sanctions regimes through new legislation, in the form of regulations, made under the Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Act 2018 (the Sanctions Act). The Act will provide the legal basis for the UK to impose, update and lift sanctions after leaving the EU.

We propose to put much of this legislation before Parliament before March 2019, to prepare for the possibility of the UK leaving the EU without a deal. Any sanctions regimes that we did not address, through regulations under the Sanctions Act by March 2019, would continue as retained EU law under the EU (Withdrawal) Act 2018. This means there will be no gaps in implementing existing sanctions regimes.

We expect that the UK’s sanctions regulations will include:

- the purposes of the sanctions regime (what the UK hopes will be achieved through imposing sanctions)

- the criteria to be met before sanctions can be imposed on a person or group

- details of sanctions, such as trade and financial sanctions

- details of exemptions that may apply, such as exemptions which allow people to trade with a certain country that would otherwise be prohibited by the regulations

- how we will enforce the sanctions measures

- other areas, such as circumstances in which information about sanctions may be shared

We would publish the names of sanctioned persons or organisations. Regulations would be published as normal.

After the UK leaves the EU, in addition to implementing UN sanctions, and looking to carry over existing EU sanctions, we will also have the powers to adopt other sanctions under the Sanctions Act. We will work with the EU and other international partners on sanctions where this is in our mutual interest.

It is also noted that, in its December 2018 Mutual Evaluation Report on the United Kingdom, the Financial Action Task Force (an independent inter-governmental body which promotes policies to protect the global financial system against, inter alia, money laundering) criticized the UK’s recent lack of public-enforcement actions in relation to sanctions breaches, and recommended that the U.K. Office of Financial Sanctions Implementation and other UK enforcement authorities “ensure” that they pursue such actions.

The following Gibson Dunn lawyers assisted in preparing this client update: Judith Alison Lee, Adam Smith, Patrick Doris, Michael Walther, Stephanie Connor, Laura Cole, Helen Galloway, Jesse Melman, R.L. Pratt, Richard Roeder, Audi Syarief and Scott Toussaint.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding the above developments. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, the authors, or any of the following leaders and members of the firm’s International Trade practice group:

United States:

Judith Alison Lee – Co-Chair, International Trade Practice, Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3591, [email protected])

Ronald Kirk – Co-Chair, International Trade Practice, Dallas (+1 214-698-3295, [email protected])

Jose W. Fernandez – New York (+1 212-351-2376, [email protected])

Marcellus A. McRae – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7675, [email protected])

Adam M. Smith – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3547, [email protected])