A summary and commentary on the recent decision of the Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal regarding service of originating process by the Securities and Futures Commission

On 30 October 2023, the Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal (the “CFA”) handed down its reasons for dismissing the appeal in Securities and Futures Commission v Isidor Subotic and Others [2023] HKCFA 32[1]. The CFA confirmed that leave is not required for the Securities and Futures Commission (the “SFC”) to serve proceedings out of jurisdiction as the relevant provisions in the Securities and Futures Ordinance (the “SFO”) has empowered the Court of First Instance (the “CFI”) to hear and determine a claim made against persons who are not within the jurisdiction.

- Background

In July 2019, the SFC commenced the present proceedings against various individuals and companies under sections 213 and 274 of the SFO. It was alleged that these parties were operating a false trading scheme involving artificially inflating the price of the share of a Hong Kong listed company before “dumping” them and causing loss to market participants and lenders. The SFC sought, amongst other relief, a restoration order in favour of the market participants involved and an injunction to freeze certain assets.

As six of the defendants in this case were located outside of Hong Kong (the “Foreign Defendants”), the SFC applied for and was granted leave to serve a concurrent writ on them outside of Hong Kong. The Foreign Defendants applied to set aside the order granting leave and sought a declaration that the CFI lacks jurisdiction over them, arguing that leave was wrongly granted as the SFC’s claims did not come within any of the “gateways” specified in Order 11, rule 1(1) of the Rules of the High Court (the “RHC”) (i.e., the types of claims for which leave to effect service outside of Hong Kong could be obtained).

The CFI[2] and the Court of Appeal[3] both upheld the decision granting leave to effect service out of the jurisdiction on the basis that claims of the SFC were either a claim founded on tort and damage was sustained or resulted from an act committed within the jurisdiction (“Gateway F”) or a claim for an injunction restraining a conduct within the jurisdiction. The Foreign Defendants then appealed to the CFA on grounds that the relief sought by the SFC under Section 213 of the SFO cannot be properly characterized as a claim and even if it is a claim, it is not founded on tort for the purpose of invoking Gateway F.

Before the CFA hearing, the CFA directed the parties to make submissions on whether leave was in fact necessary in the circumstances because under Order 11, rule 1(2) of the RHC, if a legislative provision already confers the CFI with jurisdiction in respect of a claim over a defendant outside of Hong Kong or in respect of a wrongful act committed outside Hong Kong, leave from the court is not required for effecting service of a writ out of the jurisdiction.

- CFA’s Decision

The CFA unanimously dismissed the appeal and held that, according to Order 11, rule 1(2) of RHC, it was not necessary for the SFC to seek leave from the CFI to serve its claim on the Foreign Defendants.

In coming to such conclusion, the CFA looked into three questions in particular, namely (1) what are the claims that the SFC is making; (2) whether the CFI is empowered to hear and determine the claims made by the SFC by virtual of any written law; and (3) whether the CFI is so empowered notwithstanding that the person against whom the claim is made is not within the jurisdiction of the court or that the wrongful act giving rise to the claim did not take place within the jurisdiction.

On the first question, it was observed that the writ which the SFC served upon the Foreign Defendants seeks declarations that they are persons within section 213 of the SFO who have engaged in false trading activities in contravention of sections 274 and/or 295 of the SFO.

On the second question, having identified the claims of the SFC, the CFA then considered the effect of sections 213 and 274 of the SFO. The CFA held that these provisions are intended to operate in combination and must be read together. Whilst section 274 of the SFO defines the prohibited acts of false trading, section 213 of the SFO provides for the orders that the CFI may impose against the contraveners. It is clear that by virtue of the written law, CFI is empowered to hear and determine the claims put forwarded by the SFC under sections 213 and 274 of the SFO.

On the last question, the CFA found in the affirmative because upon contravention of section 274 of the SFO, the CFI is empowered under section 213 of the SFO to grant relief against a person “in Hong Kong or elsewhere” where such person does anything that constitutes false trading affecting the Hong Kong market. It was noted that the policy to confer the CFI with extraterritorial jurisdiction over persons outside of Hong Kong is justified considering that trading on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange is global and therefore it would be necessary to make sanctions legally available against overseas fraudulent parties who cause disruption to the local market and losses to other investors.

Notwithstanding the above, the CFA also made clear that the application of Order 11 rule 1(2) of the RHC is limited to cases where the written law in question clearly contemplates proceedings being brought against persons outside of jurisdiction or where the wrongful act did not take place within the jurisdiction. It is not sufficient if the written law is of general application and may be invoked against persons within or outside the jurisdiction.

- Comment

This decision confirms that no leave is required for the SFC to serve a writ seeking reliefs such as restoration orders, damages and compensation orders or restraint orders under section 213 of the SFO on foreign defendants out of jurisdiction.

Such decision is consistent with the intent of the SFO to seek redress in relation to wrongful acts damaging to market participants whether such acts took place within or outside Hong Kong and to provide appropriate legal recourse against the wrongdoers. In light of the decision, it is expected that the SFC may take more aggressive enforcement actions against parties who have engaged in cross-border market misconduct and pursue them regardless of their physical location.

____________________________

[1] https://legalref.judiciary.hk/lrs/common/ju/ju_frame.jsp?DIS=155879

[2]https://legalref.judiciary.hk/lrs/common/ju/ju_frame.jsp?DIS=137397&currpage=T

[3]https://legalref.judiciary.hk/lrs/common/ju/ju_frame.jsp?DIS=149666

The following Gibson Dunn lawyers assisted in preparing this alert: Brian Gilchrist, Elaine Chen, Alex Wong, and Cleo Chau.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these developments. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, or the following authors in the firm’s Litigation Practice Group in Hong Kong:

Brian W. Gilchrist OBE (+852 2214 3820, bgilchrist@gibsondunn.com)

Elaine Chen (+852 2214 3821, echen@gibsondunn.com)

Alex Wong (+852 2214 3822, awong@gibsondunn.com)

Cleo Chau (+852 2214 3827, cchau@gibsondunn.com)

© 2023 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP. All rights reserved. For contact and other information, please visit us at www.gibsondunn.com.

Attorney Advertising: These materials were prepared for general informational purposes only based on information available at the time of publication and are not intended as, do not constitute, and should not be relied upon as, legal advice or a legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances. Gibson Dunn (and its affiliates, attorneys, and employees) shall not have any liability in connection with any use of these materials. The sharing of these materials does not establish an attorney-client relationship with the recipient and should not be relied upon as an alternative for advice from qualified counsel. Please note that facts and circumstances may vary, and prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome.

On November 2, 2023, Hong Kong’s Securities and Futures Commission (“SFC”) published two circulars providing guidance to intermediaries engaging in tokenised securities-related activities (the “Tokenised Securities Circular”),[1] and on the tokenisation of SFC-authorised investment products (the “Investment Products Circular”) (collectively, the “Circulars”).[2]

As further explained below, the Circulars reflect a distinct evolution in the SFC’s views on tokenised securities, in particular by explicitly superseding the SFC’s previous March 2019 statement characterising security tokens as complex products requiring extra investment protection measures and restricting their offering to professional investors (the “March 2019 Statement”).[3] Instead, the SFC has made it clear in the Tokenised Securities Circular that it now considers tokenised securities to be traditional securities with a tokenisation wrapper, as discussed further below, and has noted that there is a growing interest in tokenising traditional financial instruments in the market, including the issuance and distribution of tokenised funds by fund managers and management of funds that invest in tokenised securities. The two Circulars aim to assist intermediaries interested in exploring tokenisation by providing more guidance on regulatory expectations with respect to tokenised securities-related activities and how to address the risks specific to tokenised securities.

I. The Tokenised Securities Circular represents an important evolution in the SFC’s views of Tokenised Securities

As a starting point, the SFC has indicated that for the purposes of the Tokenised Securities Circular, it considers tokenized securities to be traditional financial instruments (e.g. bonds or funds) that are securities (as defined in the Securities and Futures Ordinance (“SFO”)) which utilise distributed ledger technology (e.g. blockchain technology) (“DLT”) or a similar technology in their security lifecycle (“Tokenised Securities”).[4] In the SFC’s words, these securities are “fundamentally traditional securities with a tokenisation wrapper”. Given this, the SFC has emphasised in the Tokenised Securities Circular that the existing legal and regulatory requirements for securities will continue to apply to Tokenised Securities.

In taking this approach, the Tokenised Securities Circular represents an important step forward from the March 2019 Statement, which characterised Security Tokens as complex products and imposed a “professional investor-only” (“PI-only”) restriction on the distribution and marketing of these securities. However, the SFC has now made it clear that tokenisation should not alter the complexity of the underlying security. Therefore, instead of a blanket categorisation of Tokenised Security as a “complex product”, the SFC now instructs intermediaries to adopt a “see-through approach”. In other words, intermediaries should determine the complexity of a Tokenised Security by assessing the underlying traditional security against the factors set out in the Guidelines on Online Distribution and Advisory Platforms and the Code of Conduct for Persons Licensed by or Registered with the Securities and Futures Commission (the “Code of Conduct”),[5] as well as guidance issued by the SFC from time to time.

Similarly, the SFC has indicated that as Tokenised Securities are fundamentally traditional securities with a tokenisation wrapper, there is no need to impose a mandatory PI-only restriction. However, the offerings of Tokenised Securities to the Hong Kong public will continue to be subject to the prospectus regime in the Companies (Winding Up and Miscellaneous Provisions) Ordinance and offers of investments regime under Part IV of the SFO (“Public Offering Regimes”). As such, Tokenised Securities that have not complied with the prospectus requirements or offers of investments regime can only be offered to PIs.

The SFC has also noted that existing conduct requirements for securities-related activities will apply to the distribution of or advising on Tokenised Securities, management of funds investing in Tokenised Securities and secondary market trading of Tokenised Securities on virtual asset trading platforms.

II. Key regulatory expectations when engaging in Tokenised Securities-related activities

The Tokenised Securities Circular goes on to set out guidance regarding the SFC’s expectations for intermediaries choosing to engage in Tokenised Securities related-activities, as summarised below.

|

Risk management considerations |

The SFC has emphasised in the Tokenised Securities Circular that its approach remains “same business, same risks, same rules”. However, the SFC considers that tokenisation has created new risks for intermediaries in relation to ownership (e.g. in relation to how ownership interests are transferred and recorded) and technology risks (e.g. forking, network outages and cybersecurity risks). These risks can vary depending on the type of the DLT network utilised for the Tokenised Securities, with the SFC flagging that intermediaries should apply particular caution in relation to Tokenised Securities in bearer form issued using permissionless tokens on open, public network that does not restrict access for privileges and offers decentralised, anonymous, and large-scale user base (“Public-Permissionless Network”). This is on the basis that these sorts of securities are exposed to increased cybersecurity risks due to the lack of restrictions for public access and the open nature of these networks. In the event of a cyberattack, theft or hacking, the SFC has flagged that investors may experience increased difficulties in recovering their assets or losses, and may face potentially substantive losses without recourse. Intermediaries should address such risks accordingly by adopting adequate safeguards and controls. |

|

Considerations for intermediaries engaging in Tokenised Securities-related activities |

In general, the SFC has noted that:

Issuance of Tokenised Securities Where intermediaries issue or are substantially involved in the issuance of Tokenised Securities which they also intend to deal in or advise on (e.g. fund managers of tokenised funds), the SFC will consider that these intermediaries remain responsible for the overall operation of the tokenisation arrangement, even if they have entered into outsourcing arrangements with third party vendors or service providers. The SFC has set out a non-exhaustive list of considerations that intermediaries involving in issuance should consider in relation to technical and other risks (see Part A of the Appendix to the Tokenised Securities Circular).[6] These considerations include, for example, the experience of the third party vendors involved in the tokenisation process, the robustness of the DLT network, data privacy risks and enforceability of the Tokenised Security. The SFC has also stated that for custodial arrangements, intermediaries should consider the features and risks of the Tokenised Securities when considering the most appropriate custodial arrangement in relation to such Tokenised Securities, and that it expects custodial arrangements for bearer form Tokenised Securities using permissionless tokens on Public-Permissionless Networks to take into consideration the factors set out at Part B of the Appendix.[7] These factors include, for example, the custodian’s management of conflicts of interest, its cybersecurity risk management measures and its experience in providing custodial services for Tokenised Securities. Dealing in, advising on, or managing portfolios investing in Tokenised Securities Intermediaries should conduct due diligence on the issuers and their third party vendors / service providers, as well as the features and risks arising from the tokenisation arrangement when dealing in, advising on, or managing portfolios investing in Tokenised Securities. Intermediaries should also ensure that they are satisfied that adequate controls have been put in place by the issuers and their third party vendors / service providers to manage ownership and technology risks posed by the Tokenised Security before engaging in any of these activities. |

|

Disclosure obligations |

The SFC expects intermediaries to make adequate disclosures to clients of relevant material information (including risks) specific to Tokenised Securities. Such material information should include, for example:

|

III. Other clarifications regarding Tokenised Securities

The Tokenised Securities Circular also includes three important clarifications regarding the SFC’s approach to Tokenised Securities going forward:

- The SFC has previously stated that the “de minimis threshold” under the Proforma Terms and Conditions for Licensed Corporations which Manage Portfolios that Invest in Virtual Assets (“Terms and Conditions”) only applies to virtual assets, as defined under the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorist Financing Ordinance.[8] [9] Viewed in conjunction with the Circulars, fund managers managing portfolios investing in Tokenised Securities which meet the “de minimis threshold” would not be subjected to the Terms and Conditions unless these portfolios also invest in virtual assets meeting the “de minimis threshold”.

- Virtual asset trading platforms (“VATPs”) licensed by the SFC are currently required to set up a SFC-approved compensation arrangement to cover potential loss of security tokens.[10] On application by the VATP, the SFC has indicated that it is willing to consider, on a case-by-case basis, excluding certain Tokenised Securities from the required coverage.

- The SFC has also provided guidance in relation to digital securities other than Tokenised Securities – i.e. products which the SFC defines as securities as defined in the SFO which utilise DLT or other similar technology but which are not traditional financial instruments. The SFC has indicated that these sorts of digital securities which are not Tokenised Securities are likely to be complex products on the basis that they are likely to be bespoke in nature, terms and features, and not easily understood by a retail investor. Given this, intermediaries distributing such digital securities would be required to comply with the requirements for sale of complex products. Further, the SFC has reminded intermediaries not to offer these sorts of digital securities to retail investors in breach of the Public Offering Regimes. The SFC has also emphasised that intermediaries should exercise their professional judgment to assess each digital security which they deal with, including whether the security is a Tokenised Security, and should ensure that additional internal controls are implemented to address the specific risks and nature of such digital securities.

IV. Key considerations for the tokenisation of SFC-authorised investment products

The Investment Products Circular separately sets out the SFC’s requirements for considering allowing tokenisation of investment products authorised by the SFC for offering to the Hong Kong public. It must be emphasised that the SFC requirements for Tokenised Securities (as set out in Section II above) will also apply to the tokenisation of SFC-authorised investment products.

Echoing the approach taken by the SFC in the Tokenised Securities Circular, the SFC has indicated in the Investment Products Circular that it will take a “see through” approach to tokenised SFC-authorised investment products, and will allow primary dealing of tokenised SFC-authorised investment products provided that the underlying product meets certain specified product authorisation requirements and safeguards, as summarised below.

|

Tokenisation arrangement |

Product providers of tokenised SFC-authorised investment products (“Product Providers”) should:

|

|

Disclosure obligations |

The following disclosures must be made clearly and comprehensively in offering documents of a tokenised SFC-authorised investment product:

|

|

Distribution of tokenised SFC-authorised investment products |

Only regulated intermediaries (e.g. licensed corporations or registered institutions) can distribute tokenised SFC-authorised investment products. This requirement extends to Product Providers who wish to distribute their own products. These regulated intermediaries must comply with existing requirements (e.g. client onboarding requirements and suitability assessments) as applicable. |

|

Staff competence |

Product Providers must ensure that they have at least one competent staff member with the relevant experience and expertise to operate and/or supervise the tokenisation arrangement and to manage the ownership and technology risks of the arrangement. |

|

Prior SFC consultation or approval |

Prior consultation with the SFC will be required for tokenisation of existing SFC-authorised investments and the introduction of new investment products with tokenisation features. Changes made to the tokenisation of existing SFC-authorised investments must also be approved by the SFC. For example, the SFC has noted that its prior approval must be sought before adding the disclosure of new tokenised unit or share class of an SFC-authorised fund to the offering documents for offering to the Hong Kong public, unless the tokenisation arrangement is substantially the same as the existing arrangement. |

Meanwhile, driven by investor protection concerns, the SFC has adopted a more cautious attitude towards secondary trading of tokenised SFC-authorised investment products, on the basis that further careful consideration is required in order to provide a substantially similar level of investor protection to investors to that afforded to those investing in a non-tokenised product. The considerations flagged by the SFC include maintenance of proper and instant token ownership record, readiness of trading infrastructure and market participants to support liquidity, and fair pricing of tokenised products. The SFC has indicated that it will continue to engage with the market on proper measures to address risks involved in secondary trading.

V. Conclusion

While the Circulars provide welcome guidance to intermediaries in relation to tokenisation of traditional financial instruments, it is clear that the SFC will expect intermediaries to closely engage with them prior to embarking on any activities in relation to tokenised products. Given the fast-changing nature of the cryptocurrency space, the SFC may provide further guidance or impose additional requirements for Tokenised Securities and/or tokenised SFC-authorised investment products from time to time. In particular, it appears that the SFC may well release further guidance in relation to secondary trading of SFC-authorised investment products following further engagement with market participants. Interested intermediaries should closely monitor such developments and ensure continuous compliance.

____________________________

[1] “Circular on intermediaries engaging in tokenised securities-related activities”, published by the SFC on November 2, 2023, available at: https://apps.sfc.hk/edistributionWeb/gateway/EN/circular/doc?refNo=23EC52

[2] “Circular on tokenisation of SFC-authorised investment products”, published by the SFC on November 2, 2023, available at: https://apps.sfc.hk/edistributionWeb/gateway/EN/circular/doc?refNo=23EC53

[3] “Statement on Security Token Offerings” published by the SFC on March 28, 2019, available at: https://www.sfc.hk/en/News-and-announcements/Policy-statements-and-announcements/Statement-on-Security-Token-Offerings

[4] “Securities” is defined under section 1 of Part 1 of Schedule 1 to the SFO, available at: https://www.elegislation.gov.hk/hk/cap571

[5] See Chapter 6 of the Guidelines on Online Distribution and Advisory Platforms, published by the SFC in July 2019, available at: https://www.sfc.hk/-/media/EN/assets/components/codes/files-current/web/guidelines/guidelines-on-online-distribution-and-advisory-platforms/guidelines-on-online-distribution-and-advisory-platforms.pdf?rev=689af636b3ad4077929d46a94631e458. See also paragraph 5.5 of the Code of Conduct, published by the SFC, available at: https://www.sfc.hk/-/media/EN/assets/components/codes/files-current/web/codes/code-of-conduct-for-persons-licensed-by-or-registered-with-the-securities-and-futures-commission/Code_of_conduct-Sep-2023_Eng-Final-with-Bookmark.pdf?rev=209e9f3b717e4d70b45bfe45a0bb6288

[6] See Part A of Appendix to the “Circular on intermediaries engaging in tokenised securities-related activities” published by the SFC on November 2, 2023, available here: https://apps.sfc.hk/edistributionWeb/api/circular/openAppendix?lang=EN&refNo=23EC52&appendix=0

[7] See Part A of Appendix to the “Circular on intermediaries engaging in tokenised securities-related activities” published by the SFC on November 2, 2023, available here: https://apps.sfc.hk/edistributionWeb/api/circular/openAppendix?lang=EN&refNo=23EC52&appendix=0

[8] The Terms and Conditions are imposed on licensed corporations which manage or plan to manage portfolios with (i) a stated investment objective to invest in virtual assets; or (ii) an intention to invest 10% or more of the gross asset value of the portfolio in virtual assets (i.e. the “de minimis threshold”). See the Terms and Conditions, published by the SFC in October 2019, available at: https://www.sfc.hk/web/files/IS/publications/VA_Portfolio_Managers_Terms_and_Conditions_(EN).pdf

[9] “Joint Circular on Intermediaries’ Virtual Asset-Related Activities”, jointly published by the SFC and Hong Kong Monetary Authority on October 20, 2023, available at: https://apps.sfc.hk/edistributionWeb/gateway/EN/circular/suitability/doc?refNo=23EC44

[10] See paragraph 10.22 of the “Guidelines for Virtual Asset Trading Platform Operators”, published by the SFC in June 2023, available at: https://www.sfc.hk/-/media/EN/assets/components/codes/files-current/web/guidelines/Guidelines-for-Virtual-Asset-Trading-Platform-Operators/Guidelines-for-Virtual-Asset-Trading-Platform-Operators.pdf?rev=f6152ff73d2b4e8a8ce9dc025030c3b8

The following Gibson Dunn lawyers prepared this client alert: William Hallatt, Emily Rumble, and Jane Lu.*

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these developments. If you wish to discuss any of the matters set out above, please contact any member of Gibson Dunn’s Global Financial Regulatory team, including the following members in Hong Kong and Singapore:

William R. Hallatt – Hong Kong (+852 2214 3836, whallatt@gibsondunn.com)

Grace Chong – Singapore (+65 6507 3608, gchong@gibsondunn.com)

Emily Rumble – Hong Kong (+852 2214 3839, erumble@gibsondunn.com)

Arnold Pun – Hong Kong (+852 2214 3838, apun@gibsondunn.com)

Becky Chung – Hong Kong (+852 2214 3837, bchung@gibsondunn.com)

*Jane Lu is a paralegal in the firm’s Hong Kong office who is not yet admitted to practice law.

© 2023 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP. All rights reserved. For contact and other information, please visit us at www.gibsondunn.com.

Attorney Advertising: These materials were prepared for general informational purposes only based on information available at the time of publication and are not intended as, do not constitute, and should not be relied upon as, legal advice or a legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances. Gibson Dunn (and its affiliates, attorneys, and employees) shall not have any liability in connection with any use of these materials. The sharing of these materials does not establish an attorney-client relationship with the recipient and should not be relied upon as an alternative for advice from qualified counsel. Please note that facts and circumstances may vary, and prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome.

We are pleased to provide you with the next edition of Gibson Dunn’s digital assets regular update. This update covers recent legal news regarding all types of digital assets, including cryptocurrencies, stablecoins, CBDCs, and NFTs, as well as other blockchain and Web3 technologies. Thank you for your interest.

Enforcement Actions

United States

- Sam Bankman-Fried Convicted On All Charges After Weeks-Long Criminal Fraud Trial

On November 2, a New York jury convicted FTX founder Sam Bankman-Fried of stealing billions of dollars’ worth of FTX customer deposits, culminating one of the highest-profile criminal fraud trials in recent history. The prosecution’s case took up the bulk of the four-week trial and was highlighted by the testimony of a half-dozen former FTX and Alameda Research employees and close friends of Bankman-Fried. The defense’s only witness was Bankman-Fried himself, whose testimony spanned two and a half days. After just over four hours of deliberation, the jury returned a conviction on all seven counts, including fraud, money laundering, and conspiracy. Sentencing is scheduled for March, with Bankman-Fried facing up to a life sentence. Bankman-Fried also faces additional charges, including bribery and bank fraud, which were charged after Bankman-Fried was extradited from the Bahamas. These charges could be separately tried next year. WSJ 1; New York Times; WSJ 2; CoinDesk; CoinTelegraph.

- Federal Judge Denies SEC’s Bid To Appeal Ripple Labs’ Partial Win; SEC Drops Claims Against Two Executives

On October 3, U.S. District Judge Analisa Torres denied the SEC’s request to certify an interlocutory appeal of the judge’s partial ruling in July, holding that her prior order did not involve a controlling question of law and that there was not a “substantial ground for difference of opinion.” The SEC sought to appeal the judge’s holding that Ripple’s programmatic offers of XRP to consumers via crypto trading platforms did not constitute a sale or offer of a security under SEC v. Howey Co., 328 U.S. 293 (1946). The SEC argued in its request for certification that the Howey test was improperly applied. The SEC may appeal the July decision once the district court enters a final judgment resolving all claims.

On October 19, the SEC voluntarily dismissed its claims against Ripple Labs’ Executives Bradley Garlinghouse and Christian Larsen. The SEC previously alleged that the two aided and abetted Ripple’s Securities Act violations and a trial was set to begin in April 2024. Law360 1; Reuters; Law360 2.

- US Targets Hamas, Warns Against Crypto Funding Following Israel Attack

On October 27, U.S. Treasury Deputy Secretary Wally Adeyemo warned that the U.S. would undertake enforcement against cryptocurrency firms that fail to stop terrorist groups from moving funds. Adeyemo’s statements followed a letter earlier in the month by Senator Elizabeth Warren and dozens of members of Congress that called on the Biden administration to crack down on the use of cryptocurrency by terrorists, citing a disputed report that Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad were able to raise over $130 million in funds using cryptocurrency.

Elliptic, the firm behind some of the data cited in the report, responded in a blog post that there was “no evidence to suggest that crypto fundraising has raised anything close to” the figure cited, although some money included in the total number might have gone to small crypto brokers sometimes designated as terrorist organizations for their role in financing. Other crypto analysts, who did not provide data for the report, noted that some estimates have inaccurately assumed that all funds routed through these smaller service providers are associated with terrorism. Adeyemo’s remarks follow the Treasury’s October 18th imposition of sanctions on key Hamas members managing assets in a secret investment portfolio, as the Biden administration faced growing pressure to disrupt Hamas’s financing. Financial Times; WSJ; U.S. Department of the Treasury; Bloomberg; Washington Post; Elliptic 1; Elliptic 2; Reuters; CoinDesk; Seattle Times.

- The New York Attorney Sues General Gemini, Genesis, And DCG

On October 19, the New York Attorney General Letitia James sued Genesis Global, its parent company Digital Currency Group (DCG), and Gemini Trust, claiming that the companies defrauded investors. The defendants have denied all of the claims. NY AG Press Release; CNN.

- PayPal Receives SEC Subpoena Regarding Stablecoin

On November 1, PayPal revealed in a quarterly earnings report that it received a subpoena from the SEC’s Enforcement Division regarding its USD stablecoin, PayPal USD (PYUSD), which was launched in August. PayPal did not disclose additional details about the subpoena. The SEC has taken the position in enforcement actions that certain stablecoins qualify as securities. CoinDesk; WSJ.

- FTC Settles With Voyager; Both The FTC And CFTC Proceed With Parallel Charges Against Former CEO

On October 12, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) announced a settlement with crypto lending firm Voyager for allegedly deceptive marketing but has yet to settle with Stephen Ehrlich, a former Voyager executive, for charges arising from the same events. In their federal complaint, the FTC alleged that Voyager violated the FTC Act and the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) by falsely claiming that customer deposits of cash and cryptocurrency would be insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). The complaint further alleges that both the company and Ehrlich were aware that their claims could mislead customers. In the proposed settlement, Voyager and its affiliated companies agreed to a judgment of $1.65 billion, which will be suspended in order for Voyager to distribute its remaining assets to consumers in bankruptcy proceedings. The settlement will also permanently ban the companies from offering, marketing, or promoting any product or service related to depositing, exchanging, investing, or withdrawing consumers’ assets. A parallel claim filed against Ehrlich by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) has not been settled. FTC Announcement; Blockworks; JDSupra.

- CFPB Investigating Crypto Platform Hacks

The Director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), Rohit Chopra, announced recommendations for regulators’ future approach to payments policy, including CFPB having direct authority to address crypto platforms. “[T]o reduce the harms of errors, hacks and unauthorized transfers, the CFPB is exploring providing additional guidance to market participants to answer their questions regarding the applicability of the Electronic Fund Transfer Act (EFTA) with respect to private digital dollars and other virtual currencies,” said Chopra during the Brookings Institution event. The CFPB is investigating how to apply EFTA, which protects consumers from payments fraud, to crypto accounts. Financial Times; Forbes India.

- SafeMoon Executives Arrested And Charged By DOJ And SEC

On November 1, SafeMoon CEO John Karony and Chief Technology Officer Thomas Smith were arrested in connection with criminal charges relating to their operation of the SafeMoon crypto project. Prosecutors allege that Karony, Smith, and founder Kyle Nagy (who also was charged) told investors that their funds were “locked” safely in liquidity pools, when instead the defendants allegedly used the funds to purchase luxury cars and real estate. The SEC contemporaneously filed related civil charges against the defendants based on allegations that the company’s SafeMoon token was an unregistered security. CoinDesk; FortuneCrypto; The Block; CoinTelegraph.

International

- Three Arrows Capital Co-Founder Arrested In Singapore For Failing To Cooperate With Investigations

Local police arrested Su Zhu, co-founder of the defunct crypto hedge fund Three Arrows Capital Ltd., at Singapore’s Changi Airport on September 29. Su Zhu was attempting to flee the country after a Singapore court issued a “committal order” authorizing the arrest of Zhu and his co-founder Kyle Davies and sentencing them to four months in prison for failing to cooperate with investigations. According to liquidators of the bankrupt hedge fund, co-founders Su Zhu and Kyle Davies failed to produce requested documents and were unhelpful in locating assets needed to repay the company’s creditors. Three Arrows Capital collapsed in June 2022 after allegedly defaulting on $660 million in debt. At this time, the location of co-founder Kyle Davies remains unknown. Law360; CoinDesk.

- Israel Orders Freeze Of Crypto Assets In Bid To Block Funding For Hamas

A week after the October 7 attack on Israel, Israeli authorities closed more than 100 cryptocurrency accounts and requested information on up to 200 additional accounts, in coordination between the country’s defense ministry and intelligence agencies. This follows Israel’s reported seizure of funds linked to Palestinian Islamic Jihad on July 4, including crypto exchange wallets in Tether (USDT), USD Coin (USDC), and Tron (TRX). Financial Times; Elliptic 1; WSJ; Elliptic 2; Reuters; CoinDesk.

- Kenya Calls For Shutdown In Operations Of Worldcoin Due To Privacy Concerns

In late September, a Kenyan parliamentary panel issued a report recommending that the country’s information technology regulator, the Communications Authority of Kenya, shut down the operations of cryptocurrency project Worldcoin. The panel proposes to suspend Worldcoin’s “physical presence in Kenya until there is a legal framework for regulation of virtual assets and virtual service providers.” In August, Kenyan officials ordered a halt to WorldCoin’s operations and announced that an investigation revealed privacy concerns, including that Worldcoin may have scanned the eyes of minors, as the project lacks an age-verification mechanism. Reuters; Business Insider; Parliamentary Report; Digital Assets Recent Update.

- Hong Kong Authorities Opened Investigation Into Japan Exchange (JPEX) For Fraud Allegations

Hong Kong opened an investigation into alleged fraud by Japan Exchange, or JPEX, as the city’s regulator, the Securities and Futures Commission, has accused the company of misleading investors. Up to 26 suspects have been arrested. The city’s authorities have received more than 2,300 complaints about the platform, with claims of losses totaling as much as $192 million USD. Allegations also include that JPEX misled investors by disclosing that they had applied for a crypto trading license and charged users exorbitant fees to withdraw funds. Financial Times; Bloomberg; South China Morning Post; The Standard.

- London Metropolitan Police Establishes Specialized Unit For Crypto Investigations

The London Metropolitan Police has established a specialized 40-member team dedicated to investigating crypto-related offenses, including organized crime. Crypto fraud cases in the UK surged by 41% over the past year, causing losses of more than 306 million euros. The team has investigated 74 intelligence referrals to date and have 19 current active criminal investigations. Criminal networks use digital assets because of its capability to conceal assets and seamlessly facilitate cross-border transactions. The operations runs alongside the government’s ambition to make London a hub for crypto assets and the city’s new standards for the promotion of crypto products, which are among the toughest in the world. Financial Times; TronWeekly; AP News.

- UK Financial Conduct Authority Imposes Restrictions On Rebuildingsociety.com Ltd

On October 10, the UK Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) restricted peer-to-peer lending platform rebuildingsociety.com Ltd from approving cryptoasset financial promotions. The FCA has targeted 146 unregistered crypto firms as promotional rules take effect. FCA Release; Blockchain; Blockworks 1; Blockworks 2.

Regulation and Legislation

United States

- Government Accountability Office Reports SEC’s Cryptocurrency Accounting Guidance Is Subject To Congressional Oversight

On October 31, the Government Accountability Office reported that cryptocurrency accounting guidance that the Securities and Exchange Commission issued in 2022, SEC’s Staff Accounting Bulletin 121, is an agency “rule” as defined in the Administrative Procedures Act and therefore is subject to congressional oversight under the Congressional Review Act (CRA). The CRA requires regulators to submit reports on new rules to Congress and the comptroller general for review, yet the SEC did not comply with those procedures for Staff Accounting Bulletin 121. The determination has prompted some crypto advocates to call on the SEC to take steps to either withdraw the guidance or formalize it via rulemaking. Bloomberg; Law360; CoinTelegraph.

- IRS Extends Broker Reporting Crypto Tax Rule Comment Period

On October 24, the U.S. Department of the Treasury and the IRS extended by two weeks the deadline for submitting comments on the agencies’ proposed rule that would impose tax-reporting obligations on a wide range of digital asset firms deemed to be “brokers.” The agencies extended the deadline to November 13 in response to “strong public interest”; thousands of comments already have been submitted. The agencies propose to define digital asset “brokers” to include centralized and decentralized trading platforms, digital asset payment processors, and digital wallet providers, among others. The proposed rule would exempt individual miners and validators from the “broker” classification. Senators Elizabeth Warren, Bernie Sanders, Sherrod Brown, and four other senators recently urged the Treasury and IRS to expedite issuance of a final rule. Federal Register; BlockWorks; CoinTelegraph.

- Expectations Mount That SEC Will Soon Approve Bitcoin ETFs

Several asset managers have amended their applications seeking SEC approval of an exchange-traded fund, sparking optimism that the SEC is on the verge of approving a spot Bitcoin ETF. The SEC has previously approved only Bitcoin futures ETFs, yet it must decide at least two pending spot Bitcoin ETF applications by January 10, 2024 and others by March and April of 2024. The renewed optimism follows the D.C. Circuit’s ruling vacating the SEC’s denial of Grayscale’s application for a Bitcoin ETF. The SEC has declined to seek en banc or Supreme Court review of the decision. Yahoo Finance; Reuters; CoinDesk 1; CoinDesk 2; Financial Times; Business Insider.

- FinCEN Proposes New Regulation For Transparency In Crypto Mixers And To Combat Terrorist Financing

On October 19, the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) issued a proposed rule that would identify international Convertible Virtual Currency Mixing (CVC Mixing) as “a class of transactions of primary money laundering concern.” FinCEN grounded the proposal in part on “the risk posed by the extensive use of CVC mixing services by a variety of illicit actors.” Comments on the proposed rule must be submitted by January 22, 2024. FinCen Press Release; Notice of Proposed Rulemaking; CoinTelegraph.

- California Governor Signs Crypto Licensing Bill

On October 13, California Governor Gavin Newsom signed Assembly Bill 39, which establishes the Digital Financial Assets Law, a comprehensive regulatory scheme akin to New York’s BitLicense. The Digital Financial Assets Law will require individuals and firms to obtain a Department of Financial Protection and Innovation (DFPI) license to engage in “digital financial asset business activity,” subject to certain exemptions. The law broadly defines “digital financial asset” to mean a “digital representation of value that is used as a medium of exchange, unit of account, or store of value, and that is not legal tender.” The law, which is set to go into effect on July 1, 2025, gives the DFPI authority to adopt a more detailed regulatory framework implementing the law’s requirements. CA Legislative; CoinDesk.

- CFPB Director Suggests Applying The Electronic Fund Transfer Act To Digital Assets

At the Brookings Institution’s payments conference on October 6, Rohit Chopra, director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, suggested potentially applying the Electronic Fund Transfer Act (EFTA) to “private digital dollars and other virtual currencies” to “reduce the harms of errors, hacks and unauthorized transfers.” The EFTA was enacted to protect consumers from electronic payments fraud and requires financial institutions to notify consumers of if or when they are liable for unauthorized electronic funds transfers. Chopra recommended the Treasury’s Financial Stability Oversight Council to classify some crypto activities as “systemically important payment clearing or settlement activity” to “ensure that a stablecoin is actually stable.” He further stated that the CFPB will issue orders to “certain large technology firms” to gain information on their practices on personal data and issuing private currency. Financial Times; CoinTelegraph.

- NYDFS Announces Proposed Updates To Guidance On Listing Of Virtual Currencies

On September 18, the New York Department of Financial Services (NYDFS) issued proposed updates to its guidance on the listing and delisting of cryptocurrencies. NYDFS has proposed (i) heightened risk assessment standards for coin-listing policies and tailored, enhanced requirements for retail consumer-facing products or service offerings, and (ii) new requirements associated with coin-delisting policies. Comments on the proposed guidance were due by October 20, 2023. NYDFS plans to issue its final guidance following the closure of the comment period. NYDFS; Axios.

International

- UK Publishes Report Clarifying Regulatory Approach For Crypto Ecosystem

On October 30, the UK government published a policy update further clarifying its approach for regulating the crypto industry. Consistent with its prior guidance, the government intends to seek legislation in two phases. First, in early 2024, the government intends to bring forward legislation allowing the Financial Conduct Authority to regulate fiat-backed stablecoins. Second, at a later time, the government plans to seek legislation to regulate activities relating to wider types of stablecoins and other digital assets, including algorithmic and crypto-backed stablecoins. This aligns with UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s policy to make the UK a digital-asset hub. Report; CoinDesk 1; CoinTelegraph.

- UK Lawmakers Pass Bill To Aid Seizure Of Illicit Cryptocurrency

On October 26, the UK government passed the Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Bill, allowing UK law enforcement agencies to seize, freeze, and recover crypto assets to combat crime and terrorism. UK authorities can assess and verify identities of company directors, remove invalid registered office addresses, and share information with criminal investigation agencies. GOV.UK; GOV.UK Bill Stage; Parliament; CoinDesk 1; CoinDesk 2.

- UK Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) Warns Crypto Promoting Firms

On October 25, UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) added 221 companies to its alert list for non-compliant firms after a new marketing regime took effect on October 8, 2023. The statement identifies common issues regarding safety or security claims, inadequately visible risk warnings, and inadequate information on the risks provided to customers. The new rules require crypto asset service providers to register with the FCA or seek an authorized firm to approve communication to local clients. FCA Statement; CoinTelegraph; CoinDesk.

- European Securities And Market Authority (ESMA) Publishes Statement Clarifying Implementation of MiCA

On October 17, the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) published a statement clarifying the timeline for the implementation of Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MiCA). During the implementation stage until December 2024, ESMA, the National Competent Authorities (NCAs) of the Member States and other European Supervisory Authorities (ESAs) will prepare technical standards and guidelines specifying the application of rules on issuers, offerors, and digital asset service providers. ESMA specified that full MiCA rights and protections will not apply in the implementation stage until December 2024. Further, even after MiCA becomes applicable, the Member States may allow existing crypto-asset service providers to operate without a MiCA license up to an additional 18-month transitional period. ESMA Statement; JDSupra.

- Australian Treasury Proposes To Regulate Crypto Exchanges

On October 16, the Australian Treasury proposed to require any crypto exchange that holds more than AUD 1,500 of any one client or more than AUD 5 million in total assets to obtain an Australian Financial Services license, granted by the Australian Securities and Investments commission. Australian Treasury; CoinDesk.

Civil Litigation

United States

- SEC Declines To Appeal Grayscale Ruling

Earlier this month, the SEC chose not to appeal the ruling of the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals that vacated the SEC’s denial of Grayscale Investment’s application to convert their Grayscale Bitcoin Trust (GBTC) into an exchange traded fund (ETF). With $14 billion in assets, GBTC is the largest traded closed-end fund tracking the price of Bitcoin (BTC). The SEC denied Grayscale’s application in June 2022 and Grayscale appealed the following day in the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals. In August 2023, the court ruled that the SEC’s denial of the application was “arbitrary and capricious.” The SEC did not seek en banc rehearing by the October 13 deadline. On October 23, the D.C. Court of Appeals issued its formal mandate effectuating its decision. With this victory, Grayscale has re-entered the pool of nearly a dozen pending spot Bitcoin ETF applications. SEC chair Gary Gensler commented that the review is before staff and that he would “let that play out” before commenting on the matter. Grayscale’s win has strengthened market confidence that one or many spot bitcoin ETFs will be approved in the next year, although that result is not guaranteed. The SEC could still reject the applications on grounds different from those used in the now-overturned Grayscale denial. CoinDesk 1; CoinDesk 2; Cryptonews; Axios.

- Judge in FTX Bankruptcy Case Rules To Keep Customer Names List Under Seal

Despite objections from media companies, Delaware Bankruptcy Judge John T. Dorsey allowed the names and addresses of companies on FTX’s creditor list to be shielded for another three months, after being shielded for 90 days in June. FTX argued that the creditor list should remain confidential because its customer list remains a valuable asset. On the other hand, the U.S. Trustee’s Office argued that the right of public access to court records must be taken into account. FTX’s Chapter 11 case began late last year, involving approximately 9 million individual and institutional customers who are creditors in the case. In over-the-counter markets where investors trade bankruptcy claims, the level of expected payouts for FTX creditors has more than tripled this year. Law360; CoinDesk.

Speaker’s Corner

United States

- SEC Commissioner Hester Peirce Issues Statement Of Dissent On LBRY

On October 23, LBRY Inc., a crypto-based media project, dropped its challenge to a New Hampshire federal court ruling that it sold unregistered securities. LBRY announced that it had settled with the SEC and would shut down, its assets to be placed in receivership and used to satisfy debts. On October 27, SEC Commissioner Hester Peirce issued a dissent describing the case against LBRY as unsettling and manifesting “the arbitrariness and real-life consequences of the Commission’s misguided enforcement-driven approach to crypto.” Peirce argued that the SEC’s case against LBRY conflicted with the SEC’s mission “to ensure that people buying securities receive accurate and reliable information.” Peirce further criticized the Commission as having taken “an extremely hardline approach,” seeking remedies “entirely out of proportion to any harm.” Peirce also observed that LBRY’s disclosures did not cause investors any harm since the disclosures were not proven to be inadequate or misleading. Instead of pursuing this case, Peirce argued, the Commission should have “devoted [the time and resources] to building a workable regulatory framework that companies like LBRY could have followed.” Peirce Dissent; Law360; Odysee; Policy at Paradigm.

- U.S. Senators Gillibrand And Lummis Press For Stablecoin And Illicit Finance Legislation

On October 24, U.S. Senators Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.) and Cynthia Lummis (R-Wyo.) spoke at the State of Crypto Policy & Regulation Conference, echoing the potential to pass a bipartisan stablecoin bill. Named after the two senators, the Lummis-Gillibrand bill, which cleared the House Financial Services Committee in 2022, proposes that the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (“CFTC”) regulate crypto exchanges and require regulated depository institutions to oversee all stablecoin users. The bill also pushes to more clearly define decentralized finance platforms in order to help entities determine whether they are centralized businesses, which would need to register with the CFTC under the bill. CoinDesk.

International

- Brazil’s Central Bank President Strikes Balance Between Open Networks And Privacy In Digital Brazilian Real, A Form Of CBDC

Brazil Central Bank President Roberto Campos Neto aims to accelerate international transactions through the issuance of Digital Brazilian Real (DREX), a form of a central bank digital currency (CBDC). Neto stated, “if every country has a digital currency, and we are able to connect those currencies digitally, in a fast and secure way, you actually have achieved the goal of having a common currency without actually having to sacrifice your monetary policy.” DREX operates alongside PIX, the instant payment system that has digitized Brazil’s economy. PIX has resulted in more than 170 million transactions in one day. The Block; Banco Central Do Brasil.

- Mexican Senator And Presidential Candidate Indira Kempis Pushes For Bitcoin As Legal Tender In Mexico

Mexican Senator and Presidential Candidate Indira Kempis reported that the digital peso should arrive sometime in 2024 and stated that she has been “looking for clear positions” from her fellow legislators on her 2022 proposal to make Bitcoin legal tender in the country. As of October 25, Mexican legislators have reacted both positively and negatively towards the bill, upon the installation of a Bitcoin ATM in the Mexican Senate. Decrypt; Forbes; Bitcoin.com.

Other Notable News

- Argentina’s Pro-Bitcoin Javier Milei Heads To Run-Off Election Against Pro-CBDC Finance Minister Sergio Massa

On October 2, during an Argentinian presidential debate, Finance Minister and presidential candidate Sergio Massa announced the imminent launch of an Argentinean digital currency project to address the country’s inflation crisis. He wants to launch a CBDC to also address the corruption within the country, including instances of money laundering. Considered an ambitious idea, local specialists are skeptical of Massa’s plan. Rodolfo Andragnes, the President of ONG Bitcoin Argentina, expressed that Massa’s announcement intended to attract attention to his campaign, rather than proposed a defined action plan. The other frontrunner of the presidential election, Javier Milei, supports bitcoin, the “dollarization” of Argentina’s economy, and the elimination of the Central Bank of Argentina. The run-off election will take place on November 19, 2023. CoinDesk; El Cronista; La Nacion; Forbes.

- Bitcoin Gains Recognition In Shanghai As A United Digital Currency

On September 25, the Shanghai Second Intermediate People’s Court in China published a report analyzing the legal attributes of digital currencies, the difficulties faced by judicial disposition of digital currencies, and adopting this perspective as an entry point to demonstrate the legal attributes of virtual currencies. The report highlighted the uniqueness and non-replicability of Bitcoin. The court focused on Bitcoin’s scarcity, inherent value of holders, ease of circulation and storage, and emphasized that Bitcoin can be obtained through mining, inheritance, or selling and buying. The People’s Republic of China has issued a blanket ban on cryptocurrencies. Shanghai Judicial Committee Member Report; ODaily; Yahoo Finance; CryptoNews; Forbes India.

The following Gibson Dunn lawyers prepared this client alert: Ashlie Beringer, Stephanie Brooker, Jason Cabral, M. Kendall Day, Jeffrey Steiner, Sara Weed, Ella Capone, Grace Chong, Chris Jones, Jay Minga, Nick Harper, Raquel Sghiatti, Peter Moon, Emma Li*, Elizabeth Walsh*, Vannalee Cayabyab and Yoo Jung Hah*

*Emma Li, Elizabeth Walsh, and Yoo Jung Hah are associates practicing in the firm’s New York, Denver, and Los Angeles offices, respectively, who are not yet admitted to practice law.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding the issues discussed in this update. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, any member of the firm’s FinTech and Digital Assets practice group, or the following:

FinTech and Digital Assets Group:

Ashlie Beringer, Palo Alto (650.849.5327, aberinger@gibsondunn.com)

Michael D. Bopp, Washington, D.C. (202.955.8256, mbopp@gibsondunn.com

Stephanie L. Brooker, Washington, D.C. (202.887.3502, sbrooker@gibsondunn.com)

Jason J. Cabral, New York (212.351.6267, jcabral@gibsondunn.com)

Ella Alves Capone, Washington, D.C. (202.887.3511, ecapone@gibsondunn.com)

M. Kendall Day, Washington, D.C. (202.955.8220, kday@gibsondunn.com)

Michael J. Desmond, Los Angeles/Washington, D.C. (213.229.7531, mdesmond@gibsondunn.com)

Sébastien Evrard, Hong Kong (+852 2214 3798, sevrard@gibsondunn.com)

William R. Hallatt, Hong Kong (+852 2214 3836, whallatt@gibsondunn.com)

Martin A. Hewett, Washington, D.C. (202.955.8207, mhewett@gibsondunn.com)

Michelle M. Kirschner, London (+44 (0)20 7071.4212, mkirschner@gibsondunn.com)

Stewart McDowell, San Francisco (415.393.8322, smcdowell@gibsondunn.com)

Mark K. Schonfeld, New York (212.351.2433, mschonfeld@gibsondunn.com)

Orin Snyder, New York (212.351.2400, osnyder@gibsondunn.com)

Jeffrey L. Steiner, Washington, D.C. (202.887.3632, jsteiner@gibsondunn.com)

Eric D. Vandevelde, Los Angeles (213.229.7186, evandevelde@gibsondunn.com)

Benjamin Wagner, Palo Alto (650.849.5395, bwagner@gibsondunn.com)

Sara K. Weed, Washington, D.C. (202.955.8507, sweed@gibsondunn.com)

© 2023 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP. All rights reserved. For contact and other information, please visit us at www.gibsondunn.com.

Attorney Advertising: These materials were prepared for general informational purposes only based on information available at the time of publication and are not intended as, do not constitute, and should not be relied upon as, legal advice or a legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances. Gibson Dunn (and its affiliates, attorneys, and employees) shall not have any liability in connection with any use of these materials. The sharing of these materials does not establish an attorney-client relationship with the recipient and should not be relied upon as an alternative for advice from qualified counsel. Please note that facts and circumstances may vary, and prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome.

On July 27, 2023, Hong Kong’s Securities and Futures Commission (“SFC”) published a “Circular on Licensing and Registration of Depositaries of SFC-authorised Collective Investment Schemes and Related Transitional Arrangements” (the “Circular”).[1] Trustees and custodians of SFC-authorised collective investment schemes (the “relevant CIS”) will have to be licensed or registered with the SFC for the new Type 13 regulated activity (“RA 13”) from October 2, 2024.

The Circular should be read in tandem with the soon to be enacted Schedule 11 to the Code of Conduct for Persons Licensed by or Registered with the Securities and Futures Commission (“Schedule 11”).[2] Together, the Circular and Schedule 11 provide guidance on the SFC’s expectations regarding RA 13 licensing arrangements.

The new RA 13 regulatory regime intends to remedy what the SFC has previously described as a “patchy” approach to the regulation of depositories, whereby the SFC was unable to directly supervise depositaries. Instead, the SFC could only exercise indirect oversight through the requirements under the Product Codes.[3] The RA 13 regulatory framework was proposed by the SFC in September 2019 to fill this void left by a lack of specific, direct supervision mechanism over trustees and custodians of public funds.[4] In doing so, the new RA 13 regulatory regime will also align Hong Kong’s fund custody framework with international standards; most major jurisdictions (such as the United Kingdom and Singapore) have some form of direct regulatory powers over entities providing trustee, custodian or depositary services for public funds (at a minimum). Viewed broadly, the introduction of RA 13 is also consistent with the SFC’s focus on regulating entities providing custody services – for instance, its recent decision to regulate virtual assets custody under its new virtual assets trading platform (“VATP”) regime by requiring custody be undertaken by a wholly owned subsidiary of a licensed VATP operator.

I. Who needs a RA 13 license?

The amendments made to the Securities and Futures Ordinance (“SFO”) to introduce RA 13 define it as “providing depositary services for relevant CISs”.[5] In essence, what this means is that trustees and custodians (i.e. depositaries as defined under the amendments to the SFO) of a relevant CIS at the “top level” of the custodian chain will be required to be licensed or registered for RA 13 in order to provide the following services:

- the custody and safekeeping of the CIS property, including property held on trust by the relevant CIS (“CIS Property”); and

- the oversight of the CIS to ensure that it is operated according to scheme documents.[6]

In practice, many of these depositaries were not previously supervised by the SFC until the introduction of the new RA 13 regime. This suggests that individuals who will now be required to be licensed to undertake RA 13 activities will be subjected to direct SFC supervision for the first time, and may not be accustomed to being licensed.

II. What are the RA 13 regulatory requirements?

In the table below, we highlight the key regulatory requirements applicable to depositaries licensed for RA 13 (“RA 13 Depositaries”):

|

Capital thresholds |

RA 13 Depositaries are required to maintain a paid-up share capital of not less than $10,000,000 and a liquid capital of not less than $3,000,000.[7] |

|

Treatment of Scheme Money |

RA 13 Depositaries that hold or receive scheme money under a relevant CIS (“Scheme Money”) must deposit such Scheme Money into segregated and designated trust accounts or client accounts within three business days after receipt. Each segregated account must be established and maintained for one relevant CIS only.[8] RA 13 Depositaries must not pay Scheme Money out of the segregated account unless such payment is (i) instructed in writing, or (ii) for the purpose of meeting payment, distribution, redemption settlement, or margin requirements, or (iii) to settle any charges or liabilities on behalf of the relevant CIS, as per the scheme documents.[9] |

|

Treatment of Scheme Securities |

Similarly, an RA 13 Depositary must deposit client securities which it holds or receives when providing depositary services (“Scheme Securities”) into a segregated and designated trust account or client account. Alternatively, the RA 13 Depositary can register the Scheme Securities in the name of the relevant CIS.[10] An RA 13 Depositary can only deal with Scheme Securities in accordance with written instructions or scheme documents. It must take reasonable steps to ensure that Scheme Securities are not otherwise deposited, transferred, lent or pledged.[11] |

|

Record keeping obligations |

In line with the record keeping requirements generally applicable to licensed intermediaries, RA 13 Depositaries are required to keep accounting, custody and other records to sufficiently explain and reflect the financial position and operation of the business, and support accurate profits and loss or income statements. Specifically, RA 13 Depositaries must also account for all relevant CIS Property, and make sure that its accounting systems can trace all movements of relevant CIS Property.[12] |

|

OTCD reporting |

RA 13 Depositaries are exempted from reporting specified over-the-counter (“OTC”) derivative transactions to the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (“HKMA”) when acting as a counterparty to the OTC derivative transaction.[13] Similarly, authorized institutions need not report the OTC derivative transaction to the HKMA if the counterparty of the transaction is an RA 13 Depositary acting in its capacity as a trustee of the relevant CIS.[14] |

Further, the SFC has previously clarified that the Managers-In-Charge (“MIC”) requirements under the current licensing framework extend to RA 13 licensees.[15]

III. Are there any additional requirements applicable to specific classes of RA 13 Depositaries?

Schedule 11 sets out additional requirements applicable to specific classes of RA 13 Depositaries. In the table below, we summarize the key requirements applicable to RA 13 Depositaries authorized under the Code on Unit Trusts and Mutual Funds[16] and Code on Pooled Retirement Funds (“UT/RF RA 13 Depositaries”).[17] These are mostly RA 13 Depositaries operating Chapter 7 Funds (i.e. plain vanilla funds investing in equity and/or bunds), specialized schemes (such as hedge funds, listed open-ended funds), and pooled retirement funds.

|

Appointment and oversight of delegates or third parties |

UT/RF RA 13 Depositaries should establish internal control policies and procedures to oversee appointed delegates or third parties. These internal control policies and procedures should cover the following:

UT/RF RA 13 Depositaries should also establish appropriate contingency plans to cater for instances of breaches or insolvency of these delegates or third parties.[18] |

|

Oversight of the relevant CIS |

UT/RF RA 13 Depositaries should have oversight over the operations of the relevant CIS, and ensure that the CIS is operated or administered in accordance with the relevant constitutive documents.[19] |

|

Subscription and redemption |

UT/RF RA 13 Depositaries should monitor the relevant operators of each CIS to ensure (among other things):

|

|

Distribution payments |

UT/RF RA 13 Depositaries should supervise the relevant operators of each CIS to ensure that:

With respect to each relevant CIS, UT/RF RA 13 Depositaries should ensure that distribution proceeds are transferred according to the operator’s instruction on a timely basis into a designated and segregated or omnibus bank account.[21] |

|

Custody and safekeeping of CIS Property |

UT/RF RA 13 Depositaries can adopt the safeguards to ensure the safekeeping of CIS Property:

|

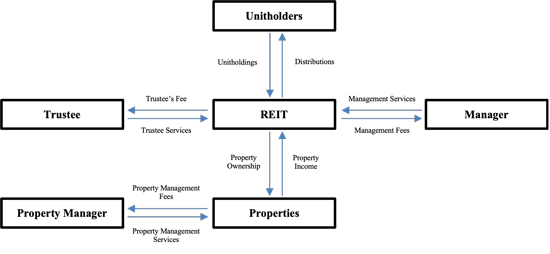

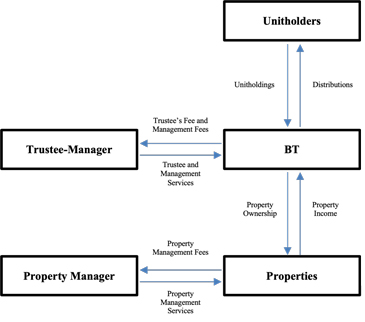

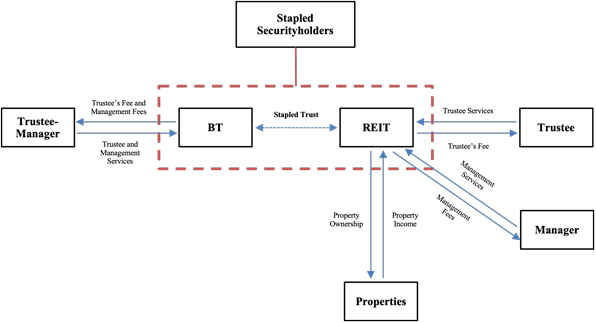

Notwithstanding the above, there are specific requirements applicable to RA 13 Depositaries authorized under the Code on Real Estate Investment Trusts (“REIT RA 13 Depositaries”).[23] These are RA 13 Depositaries operating closed-ended funds primarily investing in real estate. REIT RA 13 Depositaries are under a fiduciary duty to hold assets of Real Estate Investment Trusts (“REIT”) on trust for the benefit of the unitholders of the REIT. While the requirements applicable to UT/RF RA 13 Depositaries summarized above are generally applicable to REIT RA 13 Depositaries, Schedule 11 tailors some of these requirements to account for the unique features and product structure of REITs. The key modifications are summarized as follows:

|

Cash flow monitoring and cash reconciliation |

Under the Code on Real Estate Investment Trusts (“REIT Code”), the management company of a REIT bears the obligation to manage cash flows. Schedule 11 modifies the custody requirements – which require UT/RF RA 13 Depositaries to carry out cash reconciliation of CIS Property daily – to instead require REIT RA 13 Depositaries to ensure that the management company has put in place proper cash flow management policies and controls, and supervise the implementation of such policies and controls. |

|

Custody and safekeeping of CIS Property |

REIT RA 13 Depositaries should ensure that all REIT assets (including the title documents of REIT-owned real estate) are properly segregated and held for the benefit of the unitholders in accordance with the REIT Code and the constitutive document of the REIT. Where the REIT RA 13 Depositary considers it in the interests of the REIT for certain assets of the REIT to be held by the management company on behalf of the REIT, the REIT RA 13 Depositary should make sure that the management company has established proper safeguards and controls to properly segregate REIT assets. Additionally, the REIT RA 13 Depositary must maintain on-going oversight and control over the relevant assets. |

IV. What are the next steps?

The SFC has begun accepting licensing applications for RA 13 since July 27, 2023. Depositaries are reminded to submit RA 13 applications on or before November 30, 2023. The RA 13 regime will take effect on October 2, 2024.

_____________________________

[1] “Circular on Licensing and Registration of Depositaries of SFC-authorised Collective Investment Schemes and Related Transitional Arrangements” (July 27, 2023), published by the SFC, available at https://apps.sfc.hk/edistributionWeb/gateway/EN/circular/doc?refNo=23EC32

[2] The final text of Schedule 11 can currently be found at Appendix C, “Consultation Conclusions on Proposed Amendments to Subsidiary Legislation and SFC Codes and Guidelines to Implement the Regulatory Regime for Depositaries of SFC-authorised Collective Investment Schemes” (March 24, 2023), published by the SFC, available at https://apps.sfc.hk/edistributionWeb/api/consultation/conclusion?lang=EN&refNo=22CP1

[3] Namely, the Code on Unit Trusts and Mutual Funds, the Code on Open-Ended Fund Companies, the Code on Real Estate Investment Trusts, and the Code on Pooled Retirement Funds.

[4] “Consultation Paper on the Proposed Regulatory Regime for Depositaries of SFC-authorised Collective Investment Schemes” (September 27, 2019) (“2019 Consultation Paper”), published by the SFC, available at https://apps.sfc.hk/edistributionWeb/api/consultation/openFile?lang=EN&refNo=19CP3

[5] Section 3, “Securities and Futures Ordinance (Amendment of Schedule 5) Notice 2023” (March 20, 2023), available at https://www.gld.gov.hk/egazette/pdf/20232712/es22023271262.pdf

[6] “Scheme document” refers to (i) the trust deed constituting or governing the relevant CIS if the CIS is constituted in the form of a trust, (ii) the documents governing the formation or constitution of the relevant CIS if the CIS is constituted in any other form other than a trust, or (iii) other documents setting out the requirements relating to (a) the custody and safekeeping of any CIS Property, or (b) the oversight of the operations of the relevant CIS.

[7] Amended Schedule 1 of the Securities and Futures (Financial Resources) Rules, set out under section 10 of the “Securities and Futures (Financial Resources) (Amendment) Rules 2023” (March 20, 2023), available at https://www.gld.gov.hk/egazette/pdf/20232712/es22023271256.pdf

[8] Amended rule 10B of the Securities and Futures (Client Money) Rules, set out under section 7 of the “Securities and Futures (Client Money) (Amendment) Rules 2023” (“CMR Amendment Rules”) (March 20, 2023), available at https://www.legco.gov.hk/yr2023/english/subleg/negative/2023ln055-e.pdf

[9] Amended rule 10C of the of the Securities and Futures (Client Money) Rules, set out under section 7 of the CMR Amendment Rules

[10] Amended rule 9B of the Securities and Futures (Client Securities) Rules, set out under section 6 of the “Securities and Futures (Client Securities) (Amendment) Rules 2023” (“CSR Amendment Rules”) (March 20, 2023), available at https://www.legco.gov.hk/yr2023/english/subleg/negative/2023ln054-e.pdf

[11] Amended rules 9C and 10A of the Securities and Futures (Client Securities) Rules, set out under sections 6 and 7 of the CSR Amendment Rules respectively

[12] Amended rule 3A of the Securities and Futures (Keeping of Records) Rules, set out under section 5 of the “Securities and Futures (Keeping of Records) (Amendment) Rules 2023” (“KKR Amendment Rules) (March 20, 2023), available at https://www.legco.gov.hk/yr2023/english/subleg/negative/2023ln057-e.pdf

[13] Amended rule 10 of the Securities and Futures (OTC Derivative Transactions – Reporting and Record Keeping Obligations) Rules, set out under section 4 of the “Securities and Futures (OTC Derivative Transactions – Reporting and Record Keeping Obligations) (Amendment) Rules 2023” (“OTCD Amendment Rules”) (March 20, 2023), available at https://www.legco.gov.hk/yr2023/english/subleg/negative/2023ln061-e.pdf

[14] Amended rule 11 of the Securities and Futures (OTC Derivative Transactions – Reporting and Record Keeping Obligations) Rules, set out under section 5 of the OTCD Amendment Rules

[15] Paragraph 26, 2019 Consultation Paper. The SFC’s MIC requirements are listed in the “Circular to Licensed Corporations Regarding Measures for Augmenting the Accountability of Senior Management” (December 16, 2016), available at https://apps.sfc.hk/edistributionWeb/gateway/EN/circular/doc?refNo=16EC68, and the related Frequently Asked Questions published by the SFC (last updated on January 26, 2022), available at https://www.sfc.hk/en/faqs/intermediaries/licensing/Measures-for-augmenting-senior-management-accountability-in-licensed-corporations

[16] “Code on Unit Trusts and Mutual Funds” (January 1, 2019), published by the SFC, available at https://www.sfc.hk/-/media/EN/assets/components/codes/files-current/web/codes/section-ii-code-on-unit-trusts-and-mutual-funds/section-ii-code-on-unit-trusts-and-mutual-funds.pdf

[17] “Code on Pooled Retirement Funds” (December 2021), published by the SFC, available at https://www.sfc.hk/-/media/EN/assets/components/codes/files-current/web/codes/code-on-pooled-retirement-funds/code-on-pooled-retirement-funds.pdf?rev=9badf81950734ee08c799832be6ff92b

[18] Section 6, Schedule 11

[19] Section 8, Schedule 11

[20] Section 9, Schedule 11

[21] Section 11, Schedule 11

[22] See section 14, Schedule 11 for the full list of safeguards.

[23] “Code on Real Estate Investment Trusts” (August 2022), published by the SFC, available at https://www.sfc.hk/-/media/EN/files/COM/Reports-and-surveys/REIT-Code_Aug2022_en.pdf?rev=572cff969fc344fe8c375bcaab427f3b

The following Gibson Dunn lawyers prepared this client alert: William Hallatt, Emily Rumble, and Jane Lu.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these developments. If you wish to discuss any of the matters set out above, please contact any member of Gibson Dunn’s Global Financial Regulatory team, including the following members in Hong Kong:

William R. Hallatt (+852 2214 3836, whallatt@gibsondunn.com)

Emily Rumble (+852 2214 3839, erumble@gibsondunn.com)

Arnold Pun (+852 2214 3838, apun@gibsondunn.com)

Becky Chung (+852 2214 3837, bchung@gibsondunn.com)

© 2023 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP. All rights reserved. For contact and other information, please visit us at www.gibsondunn.com.

Attorney Advertising: These materials were prepared for general informational purposes only based on information available at the time of publication and are not intended as, do not constitute, and should not be relied upon as, legal advice or a legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances. Gibson Dunn (and its affiliates, attorneys, and employees) shall not have any liability in connection with any use of these materials. The sharing of these materials does not establish an attorney-client relationship with the recipient and should not be relied upon as an alternative for advice from qualified counsel. Please note that facts and circumstances may vary, and prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome.

We are pleased to provide you with the next edition of Gibson Dunn’s digital assets regular update. This update covers recent legal news regarding all types of digital assets, including cryptocurrencies, stablecoins, CBDCs, and NFTs, as well as other blockchain and Web3 technologies. Thank you for your interest.

Enforcement Actions

United States

On August 23, the Manhattan U.S. Attorney’s Office brought charges in the Southern District of New York against two developers of Tornado Cash, Roman Storm and Roman Semenov. Tornado Cash is a crypto application that obscures the source of assets transferred through it. Prosecutors allege that more than $1 billion was laundered through Tornado Cash, including hundreds of millions by North Korea’s Lazarus Group. Charges include conspiracy to engage in money laundering, conspiracy to violate U.S. sanctions targeting North Korea, and conspiracy to operate an unlicensed money transmitting business. Storm was arrested and released after posting bond. Also on August 23, the Office of Foreign Asset Control (OFAC) sanctioned Semenov and eight Ethereum addresses allegedly controlled by Semenov. Law360; Forbes; Indictment

- SEC Brings First Enforcement Actions Alleging NFTs Are Securities