Join our panelists from Gibson Dunn’s Environmental Litigation and Mass Tort practice group and Environment, Social, and Governance (ESG) practice area as they discuss significant developments in federal and California environmental law and forecast what to expect for 2022. This webcast covers a range of topics of significant interest to regulated industries, including ongoing and anticipated rulemakings, federal enforcement targets and initiatives, the evolving ESG landscape, and more.

PANELISTS:

Rachel Levick Corley is a partner in the Washington, D.C. office and a member of the Environmental Litigation and Mass Tort Practice Group. Ms. Corley represents clients in a wide range of federal and state litigation, including agency enforcement actions, cost recovery cases, and administrative rulemaking challenges.

David Fotouhi is a partner in the Washington D.C. office and a member of the Environmental Litigation and Mass Tort Practice Group. Mr. Fotouhi rejoined the firm in 2021 after serving as Acting General Counsel at the EPA, where he helped to develop the litigation strategy to defend the Agency’s actions from judicial challenge. Mr. Fotouhi combines his expertise in administrative and environmental law with his litigation experience and a deep understanding of EPA’s inner workings to represent clients in enforcement actions, regulatory challenges, and other environmental litigation.

Abbey Hudson is a partner in the Los Angeles office and a member of the Environmental Litigation and Mass Tort Practice Group. Ms. Hudson’s practice focuses on helping clients navigate environmental and emerging regulations and related governmental investigations. She has handled all aspects of environmental and mass tort litigation and regulatory compliance. She also provides counseling and advice to clients on environmental and regulatory compliance for a wide range of issues, including supply chain transparency requirements, comments on pending regulatory developments, and enforcement.

Michael Murphy is a partner in the Washington, D.C. office, a co-lead of the firm’s Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) practice area, and a member of the Environmental Litigation and Mass Tort and Administrative Law and Regulatory Practice Groups. Mr. Murphy counsels clients on environmental, ESG and sustainability matters, including corporate disclosures, policies, reporting and integration issues. He also represents clients in a wide variety of investigation and litigation matters, including toxic tort , and class actions, as well as administrative litigation, rulemaking proceedings, and permit actions to obtain government approval for infrastructure projects.

MCLE CREDIT INFORMATION:

This program has been approved for credit in accordance with the requirements of the New York State Continuing Legal Education Board for a maximum of 1.0 credit hour, of which 1.0 credit hour may be applied toward the areas of professional practice requirement.

This course is approved for transitional/non-transitional credit. Attorneys seeking New York credit must obtain an affirmation form prior to watching the archived version of this webcast. Please contact CLE@gibsondunn.com to request the MCLE form.

Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP certifies that this activity has been approved for MCLE credit by the State Bar of California in the amount of 1.0 hour.

California attorneys may claim “self-study” credit for viewing the archived version of this webcast. No certificate of attendance is required for California “self-study” credit.

In a further step towards the regulation of virtual assets (including digital tokens, stablecoins, and other crypto assets, “VAs”) in Hong Kong, on 28 January 2022, the Securities and Futures Commission (“SFC”) and the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (“HKMA”, collectively the “Regulators”) published a joint circular (the “Joint Circular”) and appendix document (the “Appendix”) on intermediaries’ VA-related activities. “VA-related activities” covers:

- Distribution of VA-related products;

- Provision of VA-dealing services; and

- Provision of VA-advisory services.

On the same day, the HKMA published a further circular (the “HKMA Circular”) to provide regulatory guidance to authorised institutions (“AIs”) when dealing with VAs and virtual asset service providers.

This client alert provides an overview of the key requirements set out in these two circulars and our views on the regulatory direction of travel in Hong Kong.

I. Scope of the Joint Circular and the HKMA Circular

The Joint Circular refers to “intermediaries”, which covers corporations licensed by the SFC to carry on regulated activities and AIs registered with the SFC. The HKMA Circular only applies to AIs. Therefore companies engaged in VA-related activities that are neither intermediaries nor AIs (i.e. “Unregulated VASPs”) are not directly subject to the requirements and guidance set out in these circulars.

However, these two circulars will significantly affect intermediaries and AIs’ ability to deal with Unregulated VASPs, including for their customers. For example, pursuant to the regulatory guidance in the HKMA Circular, AIs may implement systems and controls that could potentially restrict their customers from engaging in certain VA-related activities through their Hong Kong bank accounts. Furthermore, such Unregulated VASPs must ensure that their business activities do not require license, registration and/or authorisation, or else they could be found to be in breach of the Securities and Futures Ordinance (Cap. 571) (“SFO”) and other laws, and be subject to enforcement action by the Regulators.

II. Distribution of VA-related products

“VA-related products” refers to investment products which:

- Have a principal investment objective or strategy to invest in VAs;

- Derive their value principally from the value and characteristics of VAs; or

- Track or replicate the investment results or returns which closely match or correspond to VAs.

According to the Joint Circular, VA-related products are very likely to be considered “complex products” because, in the Regulators’ view, the risks of investing in VAs are not reasonably likely to be understood by a retail investor.

As such, the SFC’s investor protection measures for the sale of complex products apply when intermediaries distribute VA-related products. This means that intermediaries must ensure the suitability of transactions in VA-related products, even where there has been no solicitation or recommendation (i.e. execution-only transactions). The regulators also considered it necessary to set out additional investor protection measures for the distribution of VA-related products.

In summary, intermediaries distributing VA-related products must observe the following existing and new requirements:

- Suitability: intermediaries must comply with the suitability obligations, taking into consideration the SFC’s guidance in the Suitability FAQ.[1] There are many aspects to the suitability obligations, including requiring intermediaries to ‘know their clients’ (e.g. have knowledge of clients’ financial situation, investment experience, knowledge of investment products, purposes of investment, etc.) and to understand the investment product (i.e. by undertaking product due diligence). In respect of product due diligence, the Joint Circular prescribes additional due diligence requirements for unauthorised VA funds (i.e. VA funds not authorised by the SFC).[2]

- Professional investors only: VA-related products regarded as complex products should only be offered by intermediaries to professional investors.

- VA-knowledge test: except for institutional professional investors and qualified corporate professional investors,[3] intermediaries must assess whether their clients have sufficient knowledge of investing in VAs or VA-related products (with reference to the criteria prescribed by the SFC[4]) before effecting transactions in such products on clients behalf. If a client does not possess the required knowledge, an intermediary may only proceed if, by doing so, it is acting in the client’s best interests and the intermediary has provided training to the client on the nature and risks of VAs. Intermediaries must also ensure that their clients have sufficient net worth to be able to assume the risks and to bear the potential losses of trading VA-related products.

- VA-related derivative products: before intermediaries offer VA-related derivative products to their clients, they must assess their clients’ knowledge of derivatives (including the nature and risks of derivatives), and assure themselves that their clients have sufficient net worth to assume the risks and to bear the potential losses of trading VA-related derivative products.[5] Intermediaries are also required to provide the client a warning statement specific to VA futures contracts (as prescribed by the SFC in Appendix 5), where applicable.

- Financial accommodation: intermediaries should be cautious in providing financial accommodation to clients for investing in VA-related products, and should only do so in circumstances where they have assured themselves that their clients have the financial capacity to meet potential obligations arising from leveraged or margined positions.

- Provision of information and warning statements: intermediaries should ensure that information on VA-related products is provided in a clear and easily comprehensible manner to clients, and intermediaries should also provide VA warning statements to clients.

Note that, while not expressly stated in the Joint Circular, some of the requirements above (e.g. suitability) should not be applicable when intermediaries deal with institutional professional investors and qualified corporate professional investors, which aligns with the regulatory expectations for traditional securities products.

While the Joint Circular prescribes limited exemptions to the above requirements for VA-related derivative products traded on regulated exchanges specified by the SFC,[6] and to exchange-traded VA derivative funds authorised or approved for offering to retail investors by a regulator in a designated jurisdiction specified by the SFC.[7] However, at this time, this exemption will apply to a very small number of VA-related products because many VA-related derivative products are currently traded on unregulated VA trading platforms.

Finally, although not a new requirement, the Joint Circular reminds intermediaries to observe the provisions in Part IV of the SFO which prohibits the offering to the Hong Kong public of investments which have not been authorised by the SFC. Intermediaries are also reminded to strictly adhere to the Hong Kong selling restrictions applicable to VA-related products.

III. Provision of VA-dealing services

According to the Joint Circular, the Regulators’ are concerned that the majority of VA trading platforms are either unregulated, or are regulated only for anti-money laundering and counter-financing of terrorism (“AML/CFT”) purposes. Therefore, these VA trading platforms may not be subject to regulatory standards comparable to the SFC’s own regulatory framework for VA trading platforms.[8] As such, the Regulators will require licensed intermediaries that provide VA-dealing services to comply with the following requirements:

- SFC-licensed platforms only: intermediaries can only partner with SFC-licensed VA trading platforms to provide VA-dealing services, whether by way of introducing clients to the platform for direct trading or establishing an omnibus account with the platform. Currently, this would cover trading platforms licensed by the SFC under the voluntary opt-in regime for virtual asset trading platforms. In future, this should also expand to cover trading platforms licensed by the SFC under the future virtual asset services providers (“VASP”) regulatory regime.

- Professional investors only: intermediaries can only provide VA-dealing services to professional investors.

- Compliance with regulatory requirements for securities: although many VA may not be regarded as “securities” under the SFO, and therefore fall outside the SFC’s jurisdiction, intermediaries are expected to comply with the regulatory requirements for dealing in securities, irrespective of whether or not the VAs are securities.

- Type 1 licence or registration: the Regulators are only prepared to allow intermediaries licensed or registered for Type 1 regulated activity to provide VA-dealing services (and such services can only be provided to intermediaries’ existing clients to whom they currently provide Type 1 dealing services).

- Terms and conditions: intermediaries providing VA-dealing services will be required to comply with the SFC’s licensing or registration conditions set out in Appendix 6 to the Joint Circular. Intermediaries providing VA-dealing services under an omnibus account arrangement will also be subject to the prescribed terms and conditions as set out in Appendix 6 to the Joint Circular (the “VA T&Cs”). One of the many conditions set out in the VA T&Cs is that intermediaries providing VA-dealing services under an omnibus account arrangements should only permit their clients to deposit or withdraw fiat currencies (and not VAs) from their accounts.

- Discretionary account management services: for intermediaries providing VA discretionary account management services, where the investment objective is to invest 10% or more of gross asset value of a portfolio in VAs, the intermediaries will be required to comply with the requirements set out in the Proforma Terms and Conditions for Licensed Corporation which Management Portfolios that Invest in Virtual Assets published by the SFC in October 2019.[9] [10]

IV. Provision of VA-advisory services

According to the Joint Circular, the regulatory requirements for providing VA-advisory services can be summarised as follows:

- Compliance with regulatory requirements for securities: similar to the requirements for VA-dealing services, intermediaries are expected to comply with the regulatory requirements for advising on securities, irrespective of whether or not the VAs are securities.

- Type 1 or Type 4 licence or registration: the Regulators are only prepared to allow intermediaries licensed or registered for Type 1 or Type 4 regulated activity to provide VA-advisory services (and such services can only be provided to intermediaries’ existing clients to whom they provide services in Type 1 or Type 4 regulated activity).

- SFC’s VA T&Cs: intermediaries providing VA-advisory services will need to comply with the requirements prescribed in the VA T&Cs, including the requirement to comply with the suitability obligations.

- VA-knowledge test: intermediaries providing VA-advisory services are subject to the same VA-knowledge test requirements as intermediaries which distribute VA-related products (see above).

- Professional investors only: intermediaries can only provide VA-advisory services to professional investors.

- Advisory services in VA-related products: intermediaries providing advisory services in VA-related products are required to observe the same requirements applicable to the distribution of VA-related products (see above), including that intermediaries must ensure the suitability of their recommendations.

V. Implementation of requirements in the Joint Circular

For intermediaries that already engage in VA-related activities, there will be a six-month transition period for intermediaries serving existing clients of its VA-related activities to revise their systems and controls to align with the updated requirements in the Joint Circular.

For intermediaries that do not currently engage in VA-related activities, they should ensure that they comply with the requirements in the Joint Circular before providing such services.

Intermediaries are required to notify the SFC (and the HKMA, where applicable) before they engage in VA-related activities.

VI. HKMA Circular

The HKMA Circular provides regulatory guidance for AIs when dealing with VAs and VASPs. The guidance can be summarised as follows:

- AIs are expected to keep abreast of ongoing international developments, including those of international forums and standard-setting bodies such as the Financial Stability Board (FSB), the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS), the International Organisation of Securities Commissions (IOSCO), etc.

- In addition to Hong Kong laws and regulations, AIs should ensure that their VA activities do not breach applicable laws and regulations in other jurisdictions, and should seek legal advice from competent advisers in relevant jurisdictions outside of Hong Kong as necessary.

- AIs should undertake risk assessments to identify and understand the risks before engaging in VA activities, and should take appropriate measures to manage and mitigate the identified risks, taking into account legal and regulatory requirements. The three risk areas which are in focus are: (a) prudential supervision; (b) AML/CFT and financial crime risk; and (c) investor protection. In particular, the HKMA Circular provides guidance on the regulatory expectations on AIs to establish and implement effective AML/CFT policies, procedures and controls to manage and mitigate money-laundering and terrorist-financing risks that may arise from: (i) customers engaging in VA-related activities through their bank accounts; and (ii) AIs establishing and maintaining business relationships with VASPs. Further guidance is provided in the HKMA Circular.

- AIs intending to engage in VA activities should discuss with the HKMA and obtain the HKMA’s feedback on the adequacy of the institution’s risk-management controls before launching VA products or services.

VII. Conclusion

The Joint Circular and the HKMA Circular reflect the SFC’s and the HKMA’s ongoing efforts to regulate the VA sector, particularly from the perspective of investor protection, mitigating AML/CFT risk, and addressing prudential risk in the case of AIs. This is reflected in both existing requirements (e.g. suitability obligations) and new requirements (e.g. VA-knowledge test). For intermediaries already providing or planning to provide VA-related services, there will likely need to be considerable changes to policies and procedures, and systems and controls, to ensure compliance with the latest regulatory requirements and guidance.

While the Joint Circular and the HKMA Circular are not directly applicable to Unregulated VASPs, it can be anticipated that these two circulars will have a commercial impact on these companies, as intermediaries and AIs are likely to implement systems and controls that limit their dealings with such companies (including on behalf of the customers of intermediaries and AIs). In the medium to long-term, these companies which operate VA trading platforms in or from Hong Kong, or provide services marketed to the Hong Kong public, will likely need to be licensed by the SFC under the virtual asset services providers regime and/or under a future regulatory regime to be supervised by the HKMA.

For further information on the future regulatory regimes, please refer to our earlier client alerts:

- Licensing Regime for Virtual Asset Services Providers in Hong Kong (June 7, 2021); and

- Another Step Towards the Regulation of Cryptocurrency in Hong Kong: HKMA Releases Discussion Paper on Stablecoins (January 18, 2022).

_________________________

[1] SFC’s FAQ on Compliance with Suitability Obligations by Licensed or Registered Persons (last updated 23 December 2020) (the “Suitability FAQ”).

[2] See Appendix 4 to the Joint Circular.

[3] “Institutional professional investors” is defined under paragraph 15.2 of the Code of Conduct for Persons Licensed by or Registered with the SFC (the Code of Conduct) as persons falling under paragraphs (a) to (i) of the definition of “professional investor” in section 1 of Part 1 of Schedule 1 to the SFO. “Qualified corporate professional investors” refers to corporate professional investors which have passed the assessment requirements under paragraph 15.3A and gone through the procedures under paragraph 15.3B of the Code of Conduct.

[4] See Appendix 1 to the Joint Circular.

[5] These are existing requirements under paragraphs 5.1A and 5.3 of the Code of Conduct.

[6] This refers to the list of specified exchanges set out in Schedule 3 to the Securities and Futures (Financial Resources) Rules (Cap. 571N).

[7] The list of designated jurisdictions is set out in Appendix 2 to the Joint Circular.

[8] This refers to the voluntary opt-in regime set out in the SFC’s Position Paper on Regulation of Virtual Asset Trading Platforms (6 November 2019).

[9] Proforma Terms and Conditions for Licensed Corporation which Management Portfolios that Invest in Virtual Assets (4 October 2019).

[10] For completeness, according to the Joint Circular, for intermediaries licensed or registered for Type 1 regulated activity that are authorised by its clients to provide VA-dealing services on a discretionary basis as an ancillary service, these intermediaries should only invest less than 10% of gross asset value of its clients’ portfolio in VA.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these developments. If you wish to discuss any of the matters set out above, please contact any member of Gibson Dunn’s Crypto Taskforce (cryptotaskforce@gibsondunn.com) or the Global Financial Regulatory team, including the following authors in Hong Kong:

William R. Hallatt (+852 2214 3836, whallatt@gibsondunn.com)

Grace Chong (+65 6507 3608, gchong@gibsondunn.com)

Emily Rumble (+852 2214 3839, erumble@gibsondunn.com)

Arnold Pun (+852 2214 3838, apun@gibsondunn.com)

Becky Chung (+852 2214 3837, bchung@gibsondunn.com)

© 2022 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.

Since 6 March 2018, the EU institutions have been sending EU investors a clear message regarding the protection of their investments within the EU under so-called ‘intra-EU’ bilateral investment treaties (BITs), as well as now the Energy Charter Treaty (the ECT).

As we have reported here, the Court of Justice of the European Union (the CJEU) concluded in Achmea B.V. (formerly known as Eureko B.V.) v Slovakia that EU investors could not have recourse to arbitration under a BIT between two EU Member States. The CJEU held that arbitration under intra-EU BITs was contrary to EU law. Following Achmea, and a call from the European Commission (the Commission), twenty-three EU Member States signed an agreement purporting to terminate approximately 130 intra-EU BITs on 5 May 2020 (the Termination Agreement), as we reported here. The door remained open as to whether the ruling in Achmea would be extended to the ECT.

On 2 September 2021 came the CJEU’s decision in Republic of Moldova v Komstroy (reported on here). Adopting the policy views expressed by the Commission, and broadening the scope of its findings in Achmea, the CJEU determined that intra-EU arbitration (i.e., between an EU investor and an EU Member State) under the ECT is also incompatible with EU law.

On 26 October 2021, the CJEU went even further in its decision in Republic of Poland v PL Holdings S.à.r.l.[1] (PL Holdings). The CJEU ruled that EU Member States are precluded from entering into ad hoc arbitration agreements with EU-based investors, where such agreements would replicate the content of an arbitration agreement in a BIT between EU Member States.

Finally, and most recently, on 25 January 2022, the CJEU overturned a decision by the General Court in Micula v Romania[2] (Micula) that had quashed a Commission State aid ruling from 2015 declaring payment of compensation to claimants as per their ICSID award unlawful State aid and ordering recovery of amounts paid to them. Contrary to the General Court’s decision, in CJEU’s view, EU State aid rules can be triggered at the time of payment of an arbitral award even though all the State measures that the ICSID award compensated the claimants for were taken before Romania’s accession to the EU. The CJEU also held (inter alia) that any consent that may have been given by an EU Member State to arbitration pre-accession lacks any force, to the effect that the system of judicial remedies provided for by the EU and the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU (the TFEU) replace the arbitration procedures upon accession to the EU.

These last two developments in the intra-EU arbitration saga, which we address further below, raise yet further alarm bells for EU investors who may have contemplated relying on existing intra-EU BITs as a means of protecting their investments within the EU, or are looking to enforce intra-EU arbitral awards that pre-date Achmea. That is: despite the unanimous stance of over 50 investment arbitration tribunals so far[3] which consider Achmea not to be a bar to their jurisdiction under international law to hear treaty claims and award compensation for investors’ injuries, the European Courts and the Commission are actively taking steps to weaken that protection, at least as a matter of EU law. Hence, investors need to think carefully about how to structure (or restructure) their investments to maximise treaty protection and ensure successful enforcement of any favourable arbitral awards with an EU connection.

PL Holdings: An intra-EU arbitration agreement found in a BIT and replicated as an ad hoc agreement between the investor and a Member State is invalid under EU law

Background

PL Holdings (a Luxembourg entity) brought arbitration proceedings against Poland under the BIT between the Belgium-Luxembourg Economic Union (BLEU) and Poland after a Polish regulator ordered the compulsory sale of its interests in a Polish bank. The seat of the arbitration was Stockholm, and the case was administered by the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce. The tribunal concluded in 2017 that Poland had expropriated PL Holdings’ investment and ordered damages.

In September 2017, Poland brought set-aside proceedings before the Swedish courts, arguing that the arbitration clause in the Poland-BLEU BIT was incompatible with EU law post-Achmea.

In 2019, the Swedish Court of Appeal accepted that, in light of Achmea, the arbitration agreement in the BIT was indeed invalid. However, the court held that this invalidity did not prevent an EU Member State and an EU investor from concluding an ad hoc arbitration agreement at a later date to resolve the same dispute. The court relied on the awkward distinction made in Achmea (and also Komstroy) between commercial arbitration and investment treaty arbitration, which we reported on before—namely, that commercial arbitration “originate[s] in the freely expressed wishes of the parties [concerned]” (in contrast to investment arbitrations, which do not).[4] In the court’s view, Poland tacitly accepted PL Holding’s offer to arbitrate by failing to raise an objection based on Achmea earlier on in the proceedings, thus creating an ad hoc arbitration agreement between Poland and PL Holdings under Swedish law, as the law of the seat. This was said to be derived from the parties’ common intention to resolve the dispute in the same manner as a commercial arbitration agreement.

Poland appealed to the Swedish Supreme Court, which resulted in a preliminary ruling from the CJEU on the following question: whether Articles 267 and 344 of the TFEU as interpreted in Achmea mean that an intra-EU arbitration agreement (concluded between two Member States) is invalid even if a Member State (by free will) refrains from raising objections to jurisdiction after arbitration proceedings were commenced by the investor.

The CJEU’s ruling

The CJEU ruled that it is: “[a]ny attempt by a Member State to remedy the invalidity of an arbitration clause by means of a contract with an investor from another Member State would run counter to the first Member State’s obligation to challenge the validity of the arbitration clause”.[5] In those circumstances, the Court added, it was for the national court to uphold an application seeking to set aside an arbitration award made on the basis of an arbitration agreement infringing Articles 267 and 344 TFEU and the principles of mutual trust, sincere cooperation and autonomy of EU law.[6]

Like in Achmea, the CJEU underscored that an agreement to remove from the jurisdiction of their own courts disputes which may concern the application or interpretation of EU law may prevent those disputes from being resolved in a manner that guarantees the full effectiveness of EU law.[7] In the CJEU’s view, any ad hoc arbitration agreement, on the same terms as the investment treaty, would have the same effect, meaning that the legal approach envisaged by PL Holdings could be adopted in a multitude of disputes which may concern the application and interpretation of EU law; “thus allowing the autonomy of that law to be undermined repeatedly”.[8]

The CJEU also said, it follows from Achmea, the principles of the primacy of EU law and of sincere cooperation, that EU Member States not only may not undertake to remove disputes from the EU judicial system, but also that, where there is a PL Holdings-type situation, they are required to challenge, before the competent arbitration body or the court, the validity of the arbitration clause or the ad hoc arbitration agreement. This is further confirmed in Article 7(b) of the Termination Agreement which states that Contracting Parties “shall”—where they are party to judicial proceedings concerned an arbitral award issued on the basis of a BIT—”ask the competent national court, including in any third country, as the case may be, to set the arbitral award aside, annul it or to refrain from recognising and enforcing it”.[9] According to the CJEU, that rule is also applicable mutatis mutandis in a PL Holdings-type scenario.[10] In effect, therefore, this requirement to challenge jurisdiction represents a deemed challenge that will be interpreted as having effect at any further stage of the arbitral process, including enforcement of any ultimate award.

The latest development in Micula: a further delay to enforcement by reviving the Commission’s State aid decision; and Achmea is relevant for assessing the case

Background

The Micula saga has now been running for over fifteen years. The ICSID arbitration proceedings commenced in 2005, prior to Romania’s accession to the EU, whereby the Micula brothers argued (and the ICSID tribunal agreed) that Romania had impaired the Micula brothers’ investments by repealing certain economic incentives with a view to eliminate measures that could constitute State aid shortly before its accession to the EU. In 2013, the same ICSID tribunal ordered Romania to pay EUR 178 million in compensation.

Romania partially paid the ICSID award. In 2015, however, the Commission ruled that such payment constituted unlawful State aid, precluding Romania from making further payments and ordering recovery of amounts already paid. In short, it is the Commission’s view that payment of the award would re-establish the situation in which the Micula brothers would have found themselves had the relevant incentives not been repealed by Romania, and that this constituted operating State aid.

In June 2019,[11] post-Achmea, the General Court quashed the Commission’s ruling on the basis that all events relating to the incentive took place before Romania’s accession to the EU in 2007, and the right to receive compensation arose at the time Romania repealed the incentives in 2005 and the ICSID award was intended to compensate the revocation of the incentive retroactively. The right to receive compensation arose, therefore, when Romania repealed the incentive. As EU State aid rules were not applicable in Romania pre-accession, the Commission could not exercise powers conferred to it under those rules.[12] Moreover, the Court found that payment of the compensation after accession is irrelevant in that context, because those payments made in 2014 represent the enforcement of a right which arose in 2005.[13]

In that respect, the General Court could avoid discussing the relationship between EU law and intra-EU investment arbitration, given that “in the present case, the arbitral tribunal was not bound to apply EU law to events occurring prior to the accession before it, unlike the situation in the case which gave rise to the judgment [in Achmea]”.[14]

Undeterred, the Commission then filed an appeal before the CJEU in August 2019. Not altogether surprisingly, Spain—the respondent State in over 50 ECT cases involving the removal of renewables incentives—filed a cross-appeal supported by the Commission (the Cross-Appeal). Spain (and the Commission) claimed that the award breached the EU principle of mutual trust and autonomy of EU law as interpreted in Achmea. In parallel, the Micula brothers sought to enforce the ICSID award following the General Court’s decision, including before the courts of England and Wales, as previously reported on here.

The opinion of Advocate General Szpunar and the decision of the CJEU

Notably, in July 2021, Advocate General (AG) Szpunar to the CJEU opined that the Cross-Appeal must be dismissed on the basis that Achmea could not be applied in arbitration proceedings initiated pursuant to Sweden-Romania BIT concluded before Romania’s accession to the EU, and when those proceedings were still pending at the time of that accession.[15] Yet, when it came to analysing the Commission’s competence regarding the application of EU State aid rules, the AG suggested that the alleged aid should be deemed granted at a time when Romania was required to pay that compensation, i.e. after the issuance of the arbitral award, at the time of its implementation by Romania.[16] As the time of award payment post-dated Romania’s accession to the EU, EU law was indeed applicable to that measure and the Commission was competent to make the ruling it did.

The dispute then reached the CJEU:

- As to the question of when the alleged aid measure should be deemed granted, the Court agreed with AG Szpunar and held that EU State aid rules were applicable to the compensation paid by Romania and therefore upheld the competence of the Commission.

- As to the relevance of Achmea, because the CJEU had already concluded to overturn the General Court’s decision as per the first question, the CJEU thought it was not necessary for it to rule on the Cross-Appeal.[17] The CJEU did state, however, that the General Court had erred in considering that Achmea was irrelevant.[18] Indeed, since the compensation sought by the Micula brothers did not relate exclusively to the damage allegedly suffered before Romania’s accession in 2007 (as the relevant period for such damage extended until 2009), the arbitral proceedings could not be considered as completely confined to the pre-accession period. As such, “with effect from Romania’s accession to the European Union, the system of judicial remedies provided for by the EU and FEU Treaties replaced that arbitration procedure, the consent given to that effect by Romania, from that time onwards, lacked any force”.[19]

The case will now be remanded to the General Court which will determine: (i) whether the Commission was right to consider that the compensation granted by the ICSID award did constitute incompatible State aid; and (ii) the relevance of Achmea. In that respect, whilst this decision is highly fact specific, it does signal further issues for any EU investor looking to enforce intra-EU arbitral awards within the EU where the Commission may invoke Achmea arguments in the State aid context. In fact, even if an EU investor tries to enforce a favourable award outside the EU, there is now a risk that the Commission may require the Member State to recover amounts paid which it concludes constitute incompatible State aid.

In that vein for example, the Commission recently announced its investigation into the arbitral award in Infrastructure Services v Spain in July 2021,[20] which it considers, on a preliminary view, constitutes State aid.[21]

What options do investors with investments in the EU have in light of these developments?

The decisions in PL Holdings and Micula have slightly different ramifications for EU investors, even though both underscore that the CJEU is not going to step away from its original stance in Achmea. Although investment treaty tribunals that have ruled on the impact of Achmea on investor-State arbitration so far remain unanimously adamant that Member State consent to arbitration in intra-EU investment treaties is valid under international law,[22] both cases demonstrate the hostile position that the EU has taken towards investor protection. Hence, EU-based investors should consider structuring (or restructuring, depending on whether there is a dispute already on the horizon) their investments via non-EU Member State entities (such as through the UK post-Brexit) in order to secure the benefit of investment treaties.

Further, in the event a dispute does arise in an intra-EU context, investors may consider opting for arbitration procedures which would allow a non-EU Member State to be designated as the seat of the arbitration, thus limiting the scope for the potential application of EU law.

From an enforcement perspective, investors with existing or planned EU-investments should also consider whether the EU Member State that hosts the investment has assets in non-EU Member States whose courts reliably enforce arbitral awards and would not necessarily consider themselves bound by CJEU rulings and Commission’s jurisdiction.

As regards PL Holdings specifically, the decision has other practical implications which require careful consideration by investors depending on their circumstances. For example:

- National courts of EU Member States will now be expected to interpret their national legislation so that no Achmea-style arbitration clause is upheld to be valid. In other words, the CJEU and national courts may (in effect) overrule basic principles of domestic arbitration law regarding what a binding arbitration agreement looks like.

- On its face, the reasoning in PL Holdings could, theoretically, be extended to commercial contracts with States or State Owned Enterprises whereby the arbitration clause effectively replicates the provisions in an investment treaty. However, the judgment does not appear aimed at, for example, concession agreements or other types investor-State direct contractual arrangements. If, say, a PL Holdings-based challenge were to arise in the context of a private commercial agreement between an EU Member State and an EU investor, and a preliminary reference was made to CJEU, it is likely that the Court would be inclined not to extend the reach of Achmea to commercial arbitration agreements, following the artificial distinction it drew between commercial and investment arbitration agreements in Achmea and Komstroy.

_________________________

[1] See Judgment of the Court (Grand Chamber), Case C‑109/20, Republiken Polen (Republic of Poland) v PL Holdings S.à.r.l., ECLI:EU:C:2021:875, 26 October 2021, available here.

[2] See Judgment of the Court (Grand Chamber), Case C‑638/19 P, Viorel Micula and others v Romania, ECLI:EU:C:2022:50, 25 January 2022, available here.

[3] As of the time of publication, we are aware of at least 76 investment treaty tribunals that have considered the intra-EU objection and all have unanimously rejected it (whether under intra-EU BITs or the ECT). At least 50 of these 76 tribunals have rejected the intra-EU objection specifically founded on the basis of CJEU’s Achmea decision.

[4] Judgment of the Court (Grand Chamber), Case C‑284/16, Slowakische Republik (Slovak Republic) v Achmea BV, ECLI:EU:C:2018:158, 6 March 2018, ¶ 55 ; see further our client alerts on Achmea (available here) and Komstroy (available here).

[5] Judgment of the Court (Grand Chamber), Case C‑109/20, Republiken Polen (Republic of Poland) v PL Holdings S.à.r.l., ECLI:EU:C:2021:875, 26 October 2021, ¶ 54.

[9] See Agreement for the termination of Bilateral Investment Treaties between the Member States of the European Union, 5 May 2020, Article 7(b).

[10] Judgment of the Court (Grand Chamber), Case C-109/20, Republiken Polen (Republic of Poland) v PL Holdings S.à.r.l., ECLI:EU:C:2021:875, 26 October 2021, see ¶ 53.

[11] See Judgment of the General Court (Second Chamber), Cases T-624/15, T-694/15 and T-704/15, Viorel Micula and others v European Commission, ECLI:EU:T:2019:423, 18 June 2019, available here.

[15] Opinion of Advocate General Szpunar, Case C‑638/19 P, European Commission v Viorel Micula and others, 1 July 2021, ¶ 107.

[16] There are, in other words, two ways that the Commission can assess the Award under the State aid rules: (i) either the Award is assessed by considering the underlying reason for the payment of the damages; or (ii) the Award is assessed in isolation, i.e., on a standalone basis as ad hoc aid.

[17] See Judgment of the Court (Grand Chamber), Case C‑638/19 P, Viorel Micula and others v Romania, ECLI:EU:C:2022:50, 25 January 2022, ¶ 148.

[19] Id., ¶ 145 (emphasis added).

[20] See Infrastructure Services Luxembourg S.à.r.l. and Energia Termosolar B.V. (formerly Antin Infrastructure Services Luxembourg S.à.r.l. and Antin Energia Termosolar B.V.) v Kingdom of Spain, ICSID Case No. ARB/13/31.

[21] See European Commission Press Release, State aid: Commission opens in-depth investigation into arbitration award in favour of Antin to be paid by Spain, available here: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_21_3783.

Gibson Dunn’s lawyers are available to assist in addressing any questions you may have regarding these issues. Please contact the Gibson Dunn lawyer with whom you usually work, any member of the firm’s International Arbitration, Judgment and Arbitral Award Enforcement or Transnational Litigation practice groups, the following practice leaders and members, or the authors:

Cyrus Benson – London (+44 (0) 20 7071 4239, CBenson@gibsondunn.com)

Jeff Sullivan QC – London (+44 (0) 20 7071 4231, Jeffrey.Sullivan@gibsondunn.com)

Rahim Moloo – New York (+1 212-351-2413, rmoloo@gibsondunn.com)

Ceyda Knoebel – London (+44 (0) 20 7071 4243, CKnoebel@gibsondunn.com)

Stephanie Collins – London (+44 (0) 20 7071 4216, SCollins@gibsondunn.com)

Please also feel free to contact the following practice leaders:

International Arbitration Group:

Cyrus Benson – London (+44 (0) 20 7071 4239, cbenson@gibsondunn.com)

Penny Madden QC – London (+44 (0) 20 7071 4226, pmadden@gibsondunn.com)

Judgment and Arbitral Award Enforcement Group:

Matthew D. McGill – Washington, D.C. (+1 202-887-3680, mmcgill@gibsondunn.com)

Robert L. Weigel – New York (+1 212-351-3845, rweigel@gibsondunn.com)

Transnational Litigation Group:

Susy Bullock – London (+44 (0) 20 7071 4283, sbullock@gibsondunn.com)

Perlette Michèle Jura – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7121, pjura@gibsondunn.com)

Andrea E. Neuman – New York (+1 212-351-3883, aneuman@gibsondunn.com)

William E. Thomson – Los Angeles (+1 213-229-7891, wthomson@gibsondunn.com)

© 2022 Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Attorney Advertising: The enclosed materials have been prepared for general informational purposes only and are not intended as legal advice.

The Biden administration made its mark on U.S. sanctions and export controls in 2021—reviewing, revising, maintaining, augmenting, and in some cases revoking various trade restrictive measures created during the Trump era. China remained at the forefront of the U.S. national security dialogue as the administration sought to solidify measures to protect U.S. communications networks and sensitive personal data and blunt the development of China’s military capabilities after numerous earlier efforts by the Trump administration were blocked or limited by U.S. courts. China showed few signs of backing down in the face of U.S. pressure, instituting new restrictions that could potentially require multinational companies to choose between compliance with U.S. or Chinese law—creating a potential compliance minefield for global firms.

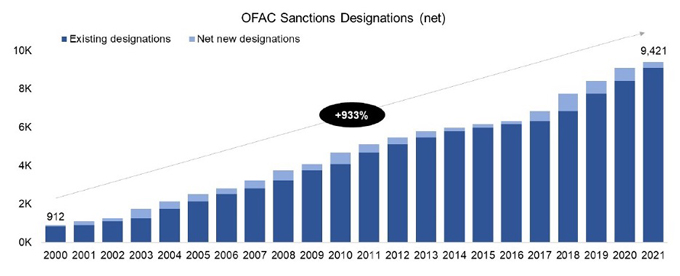

In October 2021, the U.S. Department of the Treasury published findings from its nine-month long review of the sanctions administered and enforced by the Office of Foreign Assets Control (“OFAC”), setting forth a policy framework to guide the imposition of new sanctions. The principles articulated in that review were apparent in major sanctions developments throughout the year—including new targeted sanctions on Myanmar, Belarus, and Ethiopia; the issuance of general licenses to facilitate the flow of humanitarian aid to Afghanistan after the Taliban takeover; termination of the sanctions with respect to the International Criminal Court; revocation of terrorist designations on the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (“FARC”) and the Yemen-based Houthis; and the first designation of a virtual currency exchange for its role in facilitating ransomware payments. Negotiations over the future of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (“JCPOA”)—the 2015 Iran nuclear agreement abandoned by the Trump administration in 2018—continued, and the United States waived sanctions related to the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline to appease European allies. In total, OFAC issued a total of 765 new designations and de-listed another 787 parties. By Treasury’s own estimate, there were roughly 9,421 sanctioned parties by late 2021—a 933 percent increase since 2000.

Source: U.S. Dep’t of Treasury, The Treasury 2021 Sanctions Review (Oct. 18, 2021)

OFAC sanctions developments tell only part of the story, as the United States continued to rely on export controls, foreign direct investment reviews, import restrictions, and restrictions with respect to the information and communications technology and services supply chain to accomplish foreign policy goals—often with a renewed emphasis on multilateral action. As in prior years, confronting the national security concerns associated with China remained a central focus of developments in U.S. export controls, especially those administered by the Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (“BIS”). In addition to confronting national security challenges, BIS took substantial steps to update the Export Administration Regulations, including addressing concerns associated with emerging and foundational technologies. As of this writing, the United States and its European allies were hammering out the details of an aggressive package of sanctions and export controls targeting Russia should the Kremlin follow through on threats to further invade Ukraine—presenting a key test of the Atlantic alliance and the ability of multilateral trade controls to deter a threatened use of force.

Contents

I. U.S. Trade Restrictions on China

A. Protecting Communications Networks and Sensitive Personal Data

B. Slowing the Advance of China’s Military Capabilities

C. Promoting Human Rights in Xinjiang

D. Promoting Human Rights in Hong Kong

E. Trade Imbalances and Tariffs

A. Treasury Department Sanctions Review

B. Myanmar

C. Russia

D. Belarus

E. Iran

F. Cuba

G. Ethiopia

H. Other Sanctions Developments

III. Information and Communications Technology and Services (ICTS)

A. Executive Order 13873: ICTS Supply Chain Framework

B. Executive Order 14034: Connected Software Applications

C. Executive Order 14017: Supply Chain Security

D. Executive Order 14028: Cybersecurity

E. Transatlantic Dialogues

A. Commerce Department

B. Antiboycott Developments

C. White House Export Controls and Human Rights Initiative

D. State Department

A. Sanctions Developments

B. Export Controls Developments

C. Noteworthy Judgments and Enforcement Actions

A. Sanctions Developments

B. Export Controls Developments

C. Noteworthy Judgments and Enforcement Actions

VII. People’s Republic of China

A. Countermeasures on Foreign Sanctions

B. Export Controls Regime

C. Restrictions on Cross-Border Transfers of Data

D. Security Review of Foreign Investments

______________________________

I. U.S. Trade Restrictions on China

Despite the transition from the Trump to the Biden administration, U.S. trade policy toward China in 2021 was marked by a striking degree of continuity. As under the prior administration, the dozens of new China-related trade restrictions announced this year were generally calculated to advance a handful of longstanding U.S. policy interests for which there is broad bipartisan support within the United States, including protecting U.S. communications networks and sensitive personal data; slowing the advance of China’s military capabilities; promoting human rights in Xinjiang and Hong Kong; and narrowing the bilateral trade deficit. As the Biden administration enters its second year in office and tensions between Washington and Beijing show few signs of abating, those core objectives of U.S. policy toward China appear unlikely to change, at least in the near term.

Meanwhile, as discussed more fully in Section VII, below, China this year deepened its already considerable efforts to resist U.S. pressure by adopting a host of new or expanded measures, including counter-sanctions, export controls, restrictions on cross-border data transfers, and a rigorous foreign investment review regime. In light of these new instruments in Beijing’s policy arsenal, multinational enterprises seeking to do business in both of the world’s largest economies now face the unenviable task of navigating between two competing, and often conflicting, sets of trade controls.

A. Protecting Communications Networks and Sensitive Personal Data

Spurred by concerns about Chinese espionage, the United States during 2021 sought to solidify trade restrictions designed to protect U.S. communications networks and sensitive personal data.

Notably, President Biden on June 9, 2021 issued Executive Order (“E.O.”) 14034 to restrict the ability of “foreign adversaries,” including the People’s Republic of China, to access U.S. persons’ sensitive data. That measure revokes three Executive Orders that targeted by name certain Chinese connected software applications, including TikTok and various mobile payment platforms. In place of those restrictions, E.O. 14034 articulates a more neutral set of criteria that U.S. Executive branch agencies are to use in evaluating threats to sensitive data of U.S. persons. The Order also sets forth a more rigorous process, including the preparation of two reports by the U.S. Secretary of Commerce, for recommending policy options to address the purported threat posed by such apps. From a policy perspective, these changes appear calculated to put the earlier, Trump-era restrictions on certain Chinese apps—which were effectively unenforceable, having been enjoined by multiple federal courts in September and October 2020—on firmer footing.

For a more detailed discussion of U.S. measures to secure information and communications technology and services against foreign interference, please see Section III, below.

B. Slowing the Advance of China’s Military Capabilities

Another key feature of the Biden administration’s trade policy in 2021 was its attempt to blunt the development of China’s military capabilities, including by restricting exports of U.S.-origin items to certain Chinese end-users, prohibiting U.S. persons from investing in the securities of dozens of “Chinese military-industrial complex companies,” and subjecting potential Chinese acquisitions of and investments in sensitive U.S. businesses to stringent foreign investment reviews.

Export controls this year remained a core element of U.S. efforts to slow Beijing’s emergence as a strategic competitor as the Biden administration frequently used Entity List designations to target PRC-based firms. In its expanding size, scope, and profile, the Entity List has begun to rival OFAC’s Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons (“SDN”) List as a tool of first resort when U.S. policymakers seek to wield coercive authority, especially against major economies and significant economic actors. Among the more than 80 Chinese firms added to the Entity List during 2021 were substantial enterprises such as China National Offshore Oil Corporation Ltd. and the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (“XPCC”).

Entities can be designated to the Entity List upon a determination by the End-User Review Committee (“ERC”)—which is composed of representatives of the U.S. Departments of Commerce, State, Defense, Energy and, where appropriate, the Treasury—that the entities pose a significant risk of involvement in activities contrary to the national security or foreign policy interests of the United States. Through Entity List designations, BIS prohibits the export of specified U.S.-origin items to designated entities without BIS licensing. BIS will typically announce either a policy of denial or ad hoc evaluation of license requests.

The practical impact of any Entity List designation varies in part on the scope of items BIS defines as subject to the new export licensing requirement, which could include all or only some items that are subject to the U.S. Export Administration Regulations (“EAR”). Those exporting to parties on the Entity List are also precluded from making use of any BIS license exceptions. However, because the Entity List prohibition applies only to exports of items that are “subject to the EAR,” even U.S. persons are still free to provide many kinds of services and to otherwise continue dealing with those designated in transactions that occur wholly outside of the United States and without items subject to the EAR.

The ERC has over the past several years steadily expanded the bases upon which companies and other organizations may be designated to the Entity List to include activities like enabling human rights violations and producing surveillance technology. During 2021, BIS continued this trend by announcing six rounds of Entity List designations tied to activities in support of China’s military. Among those designated in January, April, June, July, November, and December 2021 were more than 40 PRC entities for their alleged involvement in developing, for example, supercomputers, quantum computing technology, and biotechnology (including purported brain-control weaponry) for Chinese military applications.

As part of the growing use of export controls to slow the advance of China’s military capabilities, pursuant to the Military End Use / User Rule, exporters of certain listed items subject to the EAR require a license from BIS to provide such items to China, Russia, Venezuela, Burma, and Cambodia if the exporter knows or has reason to know that the exported items are intended for a “military end use” or “military end user.” In April 2020, BIS announced significant changes to these military end use and end user controls that became effective on June 29, 2020. In particular, where the prior formulation of the Military End Use / User Rule only captured items exported for the purpose of using, developing, or producing military items, the rule now covers items that merely “support or contribute to” those functions. The scope of “military end uses” subject to control was also expanded to include the operation, installation, maintenance, repair, overhaul, or refurbishing of military items.

The expanded Military End Use / User Rule has presented a host of compliance challenges for industry, prompting BIS in December 2020 to publish a new, non-exhaustive Military End User (“MEU”) List to help exporters determine which organizations are considered military end users. The 71 Chinese companies identified to date appear to be principally involved in the aerospace, aviation, and materials processing industries. Although no new Chinese entities have been added to the MEU List since state-owned Beijing Skyrizon Aviation Industry Investment Co., Ltd. was named in the final days of the Trump administration, the Biden administration has continued to administer and enforce the MEU List (as well as the underlying Military End Use / User Rule). As such, that policy tool remains readily available and could be used by BIS in coming months to target additional entities with alleged links to China’s security services.

In addition to expanding U.S. export controls targeting China, the Biden administration in June 2021 announced updated restrictions on the ability of U.S. persons to invest in publicly-traded securities of certain companies determined to operate in the defense and related materiel sector or the surveillance technology sector of China’s economy.

In place of earlier Trump-era restrictions, an Executive Order promulgated on June 3, 2021—which OFAC is calling E.O. 13959, as amended—prohibits U.S. persons from engaging in “the purchase or sale of any publicly traded securities, or any publicly traded securities that are derivative of such securities or are designed to provide investment exposure to such securities” of certain companies named by the U.S. Secretary of the Treasury. In particular, persons may now be designated a Chinese Military-Industrial Complex Company (“CMIC”) if they are determined by the Secretary of the Treasury: (1) to operate or have operated in the defense and related materiel sector or the surveillance technology sector of the economy of the People’s Republic of China, or (2) to own or control, or to be owned or controlled by, such a company. The designation criteria in E.O. 13959, as amended, are therefore broader than under the Trump-era restrictions in that they target surveillance technology companies. Indeed, the White House has indicated that it intends to use E.O. 13959, as amended, to target Chinese companies that “undermine the security or democratic values of the United States and our allies”—including especially by targeting Chinese surveillance technology companies whose activities enable surveillance beyond China’s borders, repression, and/or serious human rights abuses.

The investment restrictions set forth in E.O. 13959, as amended, take effect 60 days after a company becomes designated as a CMIC. U.S. persons have 365 days from a company’s designation date to divest their interest in that CMIC. Those investment restrictions presently target 68 companies that appear by name on a new Non-SDN Chinese Military-Industrial Complex Companies List (the “NS-CMIC List”) administered by OFAC. For the initial tranche of 59 companies that were added to the NS-CMIC List in June 2021, the investment restrictions came into effect on August 2, 2021, and U.S. persons have until June 3, 2022 to divest their interest in such firms.

From a policy perspective, the updated investment restrictions appear designed to provide greater clarity regarding precisely which PRC companies are being targeted. In that sense, E.O. 13959, as amended, seems to be a reaction to widespread market uncertainty concerning which entities were covered by the prior administration’s restrictions, along with a series of successful court challenges by companies like the smartphone maker Xiaomi that were previously named on the basis of a surprisingly thin evidentiary record. In our view, the updated restrictions appear calculated to put those earlier, Trump-era measures on firmer footing to withstand legal challenges—suggesting that the Biden administration is recalibrating investment restrictions targeting companies linked to China’s military-industrial complex to survive for the long term.

Although the Entity List, the MEU List, and the NS-CMIC List are analytically distinct from one another, all three measures appear to be driven by similar concerns among U.S. officials regarding the use of U.S. resources—namely, technology and capital—to engage in activities contrary to U.S. national security interests, including facilitating the expansion of China’s military capabilities. In addition to their shared policy underpinnings, the three lists are similar in that they are each tailored to restrict only certain narrow categories of transactions. Unlike a designation to OFAC’s SDN List—which generally results in U.S. persons being prohibited from engaging in substantially all transactions involving a targeted entity—the three lists discussed above are each less sweeping in their effects. The Entity List and the MEU List both impose a licensing requirement on exports, reexports, and transfers of certain U.S.-origin goods, software, and technology to named companies, many of which are located in China. The NS-CMIC List restricts U.S. persons from having investment exposure to publicly-traded securities of certain named Chinese companies. In each case, absent some other prohibition, U.S. and non-U.S. persons are permitted to continue engaging in all other lawful dealings with the listed entities. In that sense, these three lists each offer a potentially attractive option for U.S. officials looking to impose meaningful costs on large non-U.S. firms that act contrary to U.S. interests while avoiding the economic disruption of designating such enterprises to OFAC’s SDN List.

Consistent with a whole-of-government approach to limiting China’s access to sophisticated technologies with potential military applications, the United States during 2021 also leveraged the expanded authorities available to the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (“CFIUS” or the “Committee”) to target sensitive investments by Chinese acquirers. Notably, a lengthy CFIUS investigation led the South Korea-based chipmaker Magnachip Semiconductor Corporation in December 2021 to abandon its planned acquisition by a PRC-based private equity firm, suggesting that the Committee is likely to remain intensely focused on blunting efforts by Chinese buyers to acquire advanced technologies in general and semiconductors in particular.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Congress has in parallel sought to bolster the United States’ ability to develop the technologies of the future. The U.S. Senate in June 2021 approved a sprawling bill authorizing approximately $250 billion in spending to better position the United States to compete technologically with China, including through investments in research and development and semiconductor manufacturing. The measure, called the United States Innovation and Competition Act of 2021 (“USICA”), passed the Senate by a wide bipartisan majority—suggesting that countering China’s growing influence remains one of the few areas of agreement between congressional Republicans and Democrats. Debate over the USICA will soon shift to a conference committee between the Senate and the House of Representatives, where the measure is expected to undergo further changes during coming months. Although it is uncertain whether and in what form the bill will ultimately be approved by both chambers of Congress, in light of the bill’s broad base of support—including from President Biden—some version of the USICA appears likely to be passed by Congress and signed into law later this year.

C. Promoting Human Rights in Xinjiang

During 2021, the United States continued to ramp up legislative and regulatory efforts to address and punish reported human rights abuses, including high-tech surveillance of Muslim minority groups and forced labor, in China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (“Xinjiang”).

The Biden administration took a number of executive actions against Chinese individuals and entities implicated in the alleged Xinjiang repression campaign. In March and December 2021, OFAC—acting in concert with the European Union, the United Kingdom, and Canada— designated to the SDN List four current or former PRC government officials for their ties to mass detention programs and other abuses. In December 2021, OFAC followed up on those designations by adding to the NS-CMIC List a total of nine Chinese surveillance technology companies for their role in enabling surveillance beyond China’s borders, repression, and/or serious human rights abuses. Specifically, OFAC on December 10, 2021 named China-based SenseTime Group Limited a CMIC for owning a company alleged to have developed facial recognition programs “that can determine a target’s ethnicity, with a particular focus on identifying ethnic Uyghurs.” The following week, OFAC on December 16, 2021 named a further eight Chinese technology companies to the NS-CMIC List for operating in the surveillance technology sector of China’s economy and/or for owning or controlling such an entity. Those eight firms were similarly targeted for their alleged involvement in developing technologies that have been used to—and, some cases, were specifically designed to—track members of ethnic and religious minority groups in Xinjiang, including especially ethnic Uyghurs. In addition to enabling the biometric tracking and surveillance of minorities in China, a further risk factor for designation to the NS-CMIC List appears to be the export of such surveillance technologies to regimes with troubling human rights records, for which several of the entities identified by OFAC were cited.

In tandem with sanctions designations, the United States during 2021 leveraged export controls to advance the U.S. policy interest in curtailing human rights abuses in Xinjiang—most notably through expanded use of the Entity List. Continuing a trend begun in October 2019, the ERC on two separate occasions this past year—in June and July 2021—added a total of 19 Chinese organizations to the Entity List for their involvement in human rights violations against Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and other members of Muslim minority groups in Xinjiang. Entities so designated included the silicon producer Hoshine Silicon Industry (Shanshan) Co., Ltd. (“Hoshine”) and the Chinese state-owned paramilitary organization XPCC, each for participating in the practice of, accepting, or utilizing forced labor in Xinjiang.

Consistent with the Biden administration’s whole-of-government approach to trade with China, the United States also used import restrictions—including multiple withhold release orders issued by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (“CBP”) and enactment of the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act—to deny certain goods produced in Xinjiang access to the U.S. market.

CBP is authorized to enforce Section 307 of the Tariff Act of 1930, which prohibits the importation of foreign goods produced with forced or child labor. Upon determining that there is information that reasonably, but not conclusively, indicates that goods that are being, or are likely to be, imported into the United States may be produced with forced or child labor, CBP may issue a withhold release order, or WRO, which requires the detention of such goods at any U.S. port. To overcome a WRO and have its goods released into the United States, the importer bears the burden of demonstrating by evidence satisfactory to the Commissioner of CBP that the goods were not made, in whole or in part, with a prohibited form of labor—which, as a practical matter, is a difficult showing to make.

After issuing a record number of withhold release orders during 2020, CBP in January 2021 continued its aggressive use of this policy instrument by imposing a region-wide WRO targeting all cotton products and tomato products produced in whole or in part in Xinjiang. In June 2021, CBP issued a company-specific WRO targeting silica-based products—which are commonly used in solar panels and electronics—made by the Xinjiang-based company Hoshine and its subsidiaries. Underscoring the degree to which U.S. trade controls targeting China overlap and intersect, Hoshine was concurrently added to the Commerce Department’s Entity List, thereby constraining the company’s ability to both source inputs from, and sell goods into, the U.S. market.

Concerns regarding the PRC’s activities in Xinjiang appear to be shared by bipartisan majorities within the U.S. Congress. In December 2021, Congress passed and President Biden signed into law the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (the “Uyghur Act”), which in effect subjects all goods sourced from Xinjiang to a withhold release order. A key feature of that legislation is the creation of a rebuttable presumption—which takes effect on June 21, 2022—that all goods mined, produced, or manufactured even partially within Xinjiang are the product of forced labor and are therefore not entitled to entry at U.S. ports. Although the presumption can be overcome by “clear and convincing” evidence, the nature of which is to be articulated in formal guidance later this year, importers may face substantial practical hurdles to conducting due diligence into their supply chains as PRC entities have historically been unwilling to submit to audits of their labor practices. (Moreover, PRC entities may be prohibited by local law from cooperating with such requests in light of China’s new counter-sanctions measures, discussed in Section VII, below.) In addition to imposing import restrictions, the new law also amends the Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act of 2020 to authorize the President to impose sanctions on persons determined to be responsible for serious human rights abuses in connection with forced labor. For a more detailed description of the Uyghur Act and its implications for companies doing business in or related to Xinjiang, please see our January 2022 client alert.

As a complement to the legislative and regulatory changes described above, the Biden administration published guidance to assist the business community in conducting human rights due diligence related to Xinjiang. On July 13, 2021, the U.S. Departments of State, Treasury, Commerce, Homeland Security, and Labor, together with the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, issued an updated Xinjiang Supply Chain Business Advisory. That document spotlights practices by PRC authorities that the U.S. Government considers objectionable, including especially related to forced labor and mass surveillance. The Advisory identifies “red flags” that individuals or entities linked to Xinjiang may be using forced labor, including dealing in certain types of goods (such as cotton and polysilicon) or operating facilities located within or near known internment camps and prisons.

D. Promoting Human Rights in Hong Kong

As Beijing continued to tighten its grip on the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, the territory remained an area of focus for U.S. sanctions policy under the Biden administration. Building on policy measures announced during the preceding year—including revocation of Hong Kong’s special trading status under U.S. law, passage of the Hong Kong Autonomy Act, and the imposition of blocking sanctions against the territory’s chief executive, Carrie Lam—2021 witnessed multiple rounds of Hong Kong-related sanctions designations. Among those added to the SDN List for their alleged involvement in eroding Hong Kong’s autonomy were numerous current PRC government officials.

Additionally, the Biden administration on July 16, 2021 published a new Hong Kong Business Advisory that describes the potential financial, legal and reputational risks that can arise from operating in Hong Kong. The Advisory, which was timed to coincide with the one-year anniversary of the Hong Kong national security law, spotlights in particular the possibility of arrest under the national security law, warrantless electronic surveillance, and restrictions on the free flow of information. The Advisory also provides a helpful compilation of the U.S. legal authorities pursuant to which Hong Kong and mainland Chinese individuals and entities may be sanctioned and warns that U.S. businesses may suffer consequences for complying with those measures under China’s new counter-sanctions law, which we discuss in more detail in Section VII.A, below.

E. Trade Imbalances and Tariffs

Also in 2021, the Biden administration continued to make broad use of its authority to impose tariffs on Chinese-made goods. This policy approach—which was launched during the Trump era—remains the subject of substantial and ongoing litigation at the U.S. Court of International Trade. Among the mechanisms that the new administration has employed to retain significant tariffs targeting Beijing is Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 (“Section 301”), which allows the President to direct the U.S. Trade Representative to take all “appropriate and feasible action within the power of the President” to eliminate unfair trade practices or policies by a foreign country.

Although the Trump administration initiated Section 301 tariff investigations involving multiple jurisdictions, the Section 301 tariffs that have dominated the headlines are the tariffs imposed on China in retaliation for practices with respect to technology transfer, intellectual property, and innovation that the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative has determined to be unfair (“China 301 Tariffs”). The China 301 Tariffs were imposed in a series of waves in 2018 and 2019, and as originally implemented they together cover over $500 billion in products from China.

As we predicted in our 2020 Year-End Sanctions and Export Controls Update, although the China 301 Tariffs were a hallmark of the Trump administration’s trade policy, they have so far remained in place under President Biden and the new administration appears disinclined to relax those measures without first extracting concessions from Beijing.

II. U.S. Sanctions

A. Treasury Department Sanctions Review

In early 2021, the incoming Biden administration signaled its intent to evaluate the way the United States utilizes sanctions as a tool of foreign policy—often putting aside questions regarding the fate of a long list of Trump-era policies while the review was ongoing. The Treasury Department released the findings from its sanctions review in October 2021. In that document, Treasury articulates both the emerging challenges to the efficacy of sanctions as a national security tool, as well as a set of principles to guide U.S. sanctions policymaking in the future.

As part of a broader effort to ensure that sanctions—the use of which has sharply expanded during the past two decades—remain a durable and effective policy instrument, Treasury in its review emphasized that U.S. sanctions policies should be tied to clear, discrete objectives that are consistent with relevant Presidential guidance. To accomplish that goal, Treasury indicated that it would on a going-forward basis adopt the use of a structured policy framework—similar to the rigorous process that informs the use of force by the U.S. military—by asking whether a proposed sanctions action:

- supports a clear policy objective within a broader U.S. Government strategy;

- has been assessed to be the right tool for the circumstances;

- incorporates anticipated economic and political implications for the sanctions target(s), U.S. economy, allies, and third parties and has been calibrated to mitigate unintended impacts;

- includes a multilateral coordination and engagement strategy (where possible); and

- will be easily understood, enforceable, and, where possible, reversible.

These principles were broadly apparent in the sanctions policy decisions made by the U.S. administration throughout 2021 as OFAC often announced new sanctions actions in coordination with close U.S. allies and issued numerous humanitarian general licenses to minimize the collateral consequences of U.S. measures on vulnerable populations such as the people of Afghanistan.

B. Myanmar

As we wrote in February and April 2021, the Biden administration imposed new sanctions on Myanmar (also called “Burma”) in response to the Myanmar military’s coup against the country’s elected civilian government on February 1, 2021. Since then, the military (called the “Tatmadaw”) has maintained tight control over the country by, among other things, using lethal force on protesters, issuing a series of martial law orders, and imprisoning civilian leaders like State Counselor Aung San Suu Kyi. As the situation worsened, the Biden administration continued to enhance sanctions, notably opting for a targeted, list-based approach instead of jurisdiction-wide measures like those on Cuba, Iran, North Korea, Syria, and the Crimea region of Ukraine.

The turmoil in Myanmar marks an unfortunate echo of the past. Suu Kyi had been detained by the military in the 1990s and early 2000s and the international community, led by the United States, had previously responded with sanctions. Myanmar eventually moved toward democratization, with one key pivot point being the overwhelming victory of Suu Kyi’s political party, the National League for Democracy, in the country’s November 2015 elections. As we noted back in May 2016, the U.S. Government responded by easing sanctions pressure on Myanmar, eventually dismantling the country-specific sanctions program administered by OFAC. While there was no longer a Myanmar sanctions program, in the ensuing years OFAC continued to sanction Myanmar-based actors under other programs targeting specific behaviors such as narcotics trafficking, weapons proliferation, and human rights abuses—with an emphasis on the military-linked perpetrators of violence against the Rohingya, a religious minority group, in 2016 and 2017.

In the wake of the February 2021 military coup, rather than revive the former Myanmar sanctions program, President Biden created a new one by issuing Executive Order 14014. Under this authority, OFAC may designate to the SDN List individuals and entities determined to be directly or indirectly causing, maintaining, or exacerbating the situation in Myanmar, and/or leading Myanmar’s military or current government, or operating in the country’s defense sector. Under E.O. 14014, OFAC may also designate the adult relatives of a designee, the entities owned or controlled by a designee, or those providing material support to a designee.